Submitted:

01 May 2025

Posted:

05 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

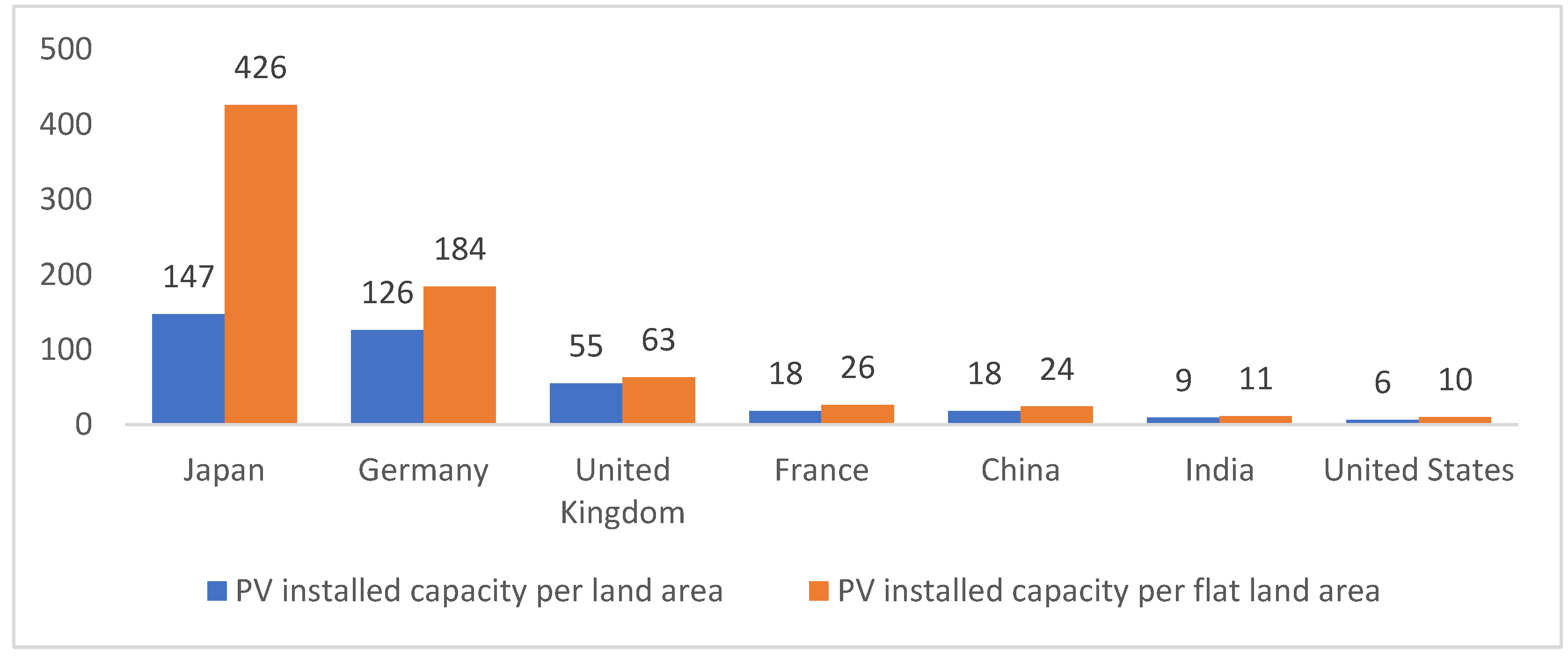

1. Introduction

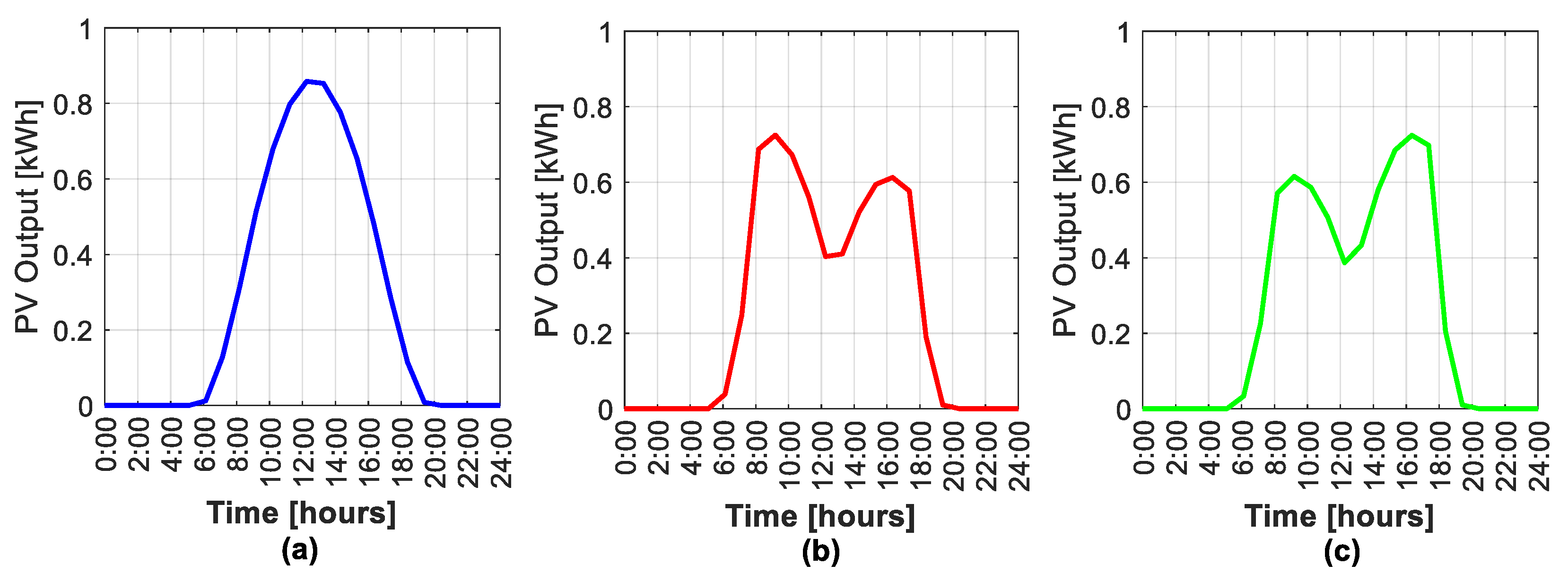

2. Vertical Bifacial Modules

2.1. Irradiance Calculation Model

3. Curtailment and Fairness Evaluation

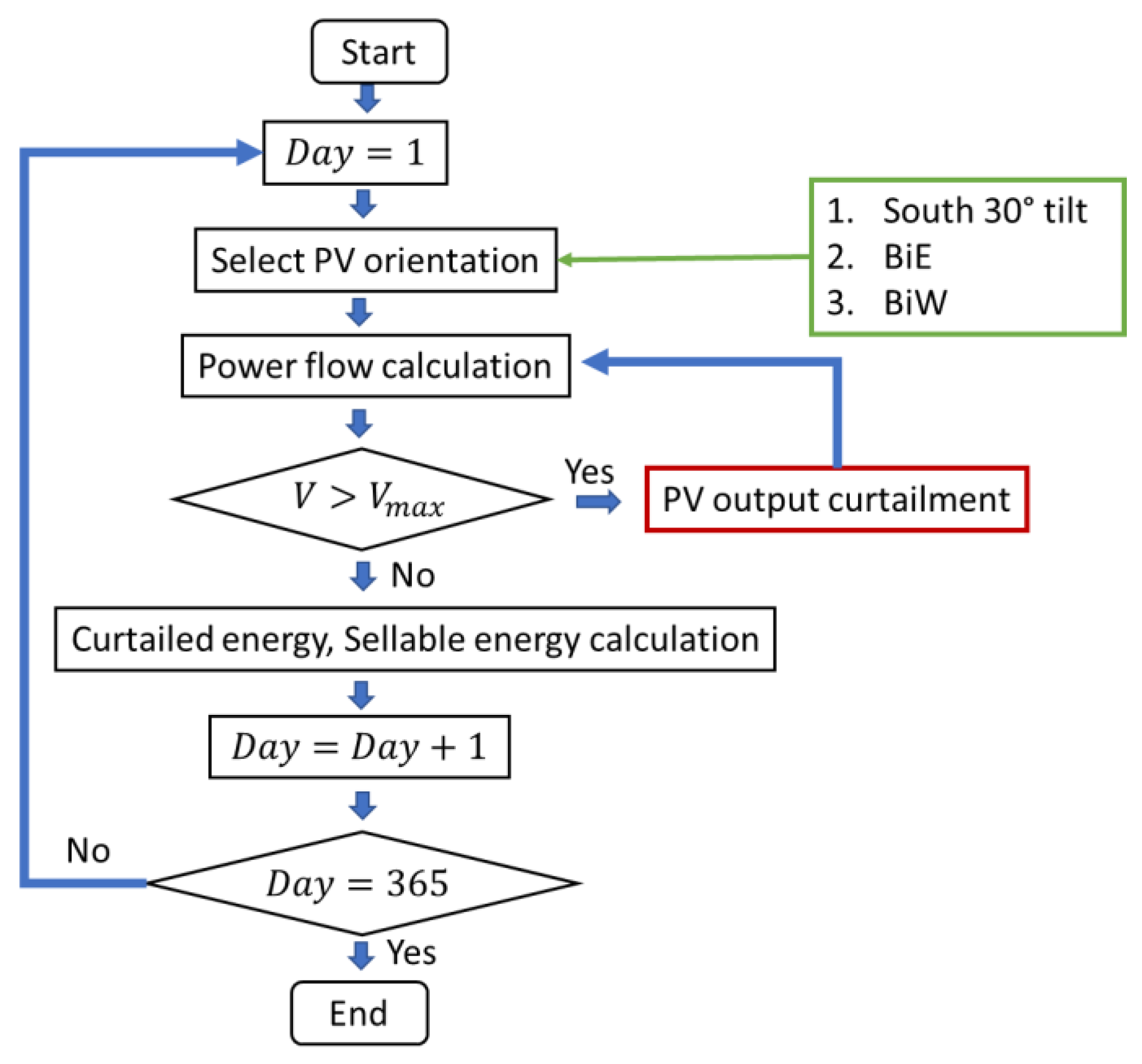

3.1. Curtailment Energy Modelling

3.2. Fairness Evaluation Metrics

3.2.1. Curtailed Energy Index (CEI)

3.2.2. Jain Fairness Index (JFI)

3.2.3. Gini Index (GI)

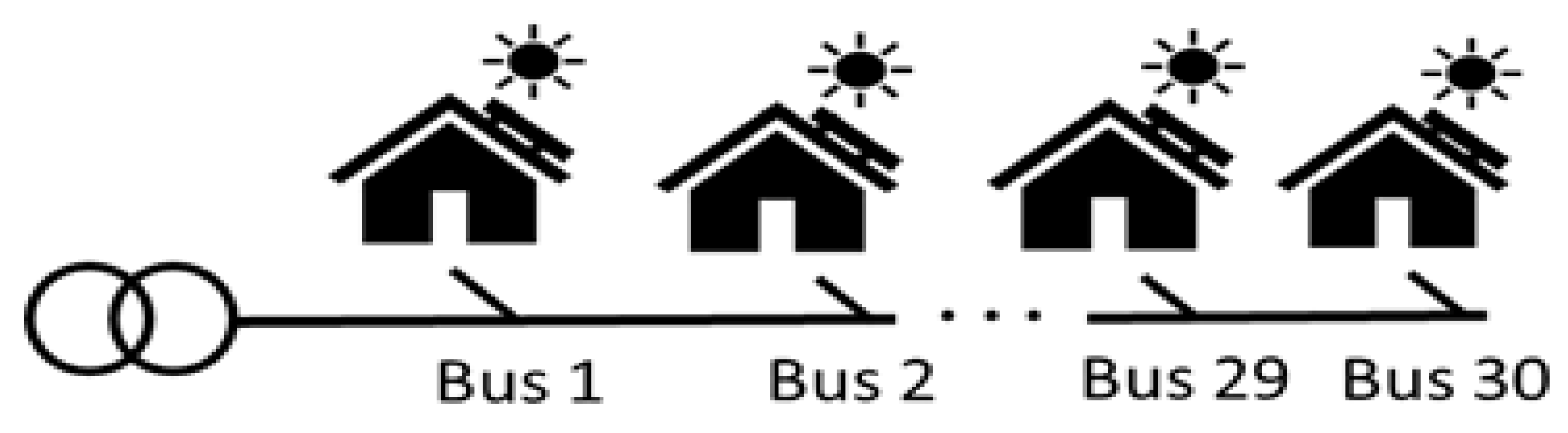

4. Simulation Conditions

| Parameter | Value |

| LRT installed capacity | 10 MVA |

| Reference Voltage | 6.6 kV |

| Line type | ALOE32 |

| Line impedance | 0.928 +j 0.415 Ω/km |

| Susceptance | S/km |

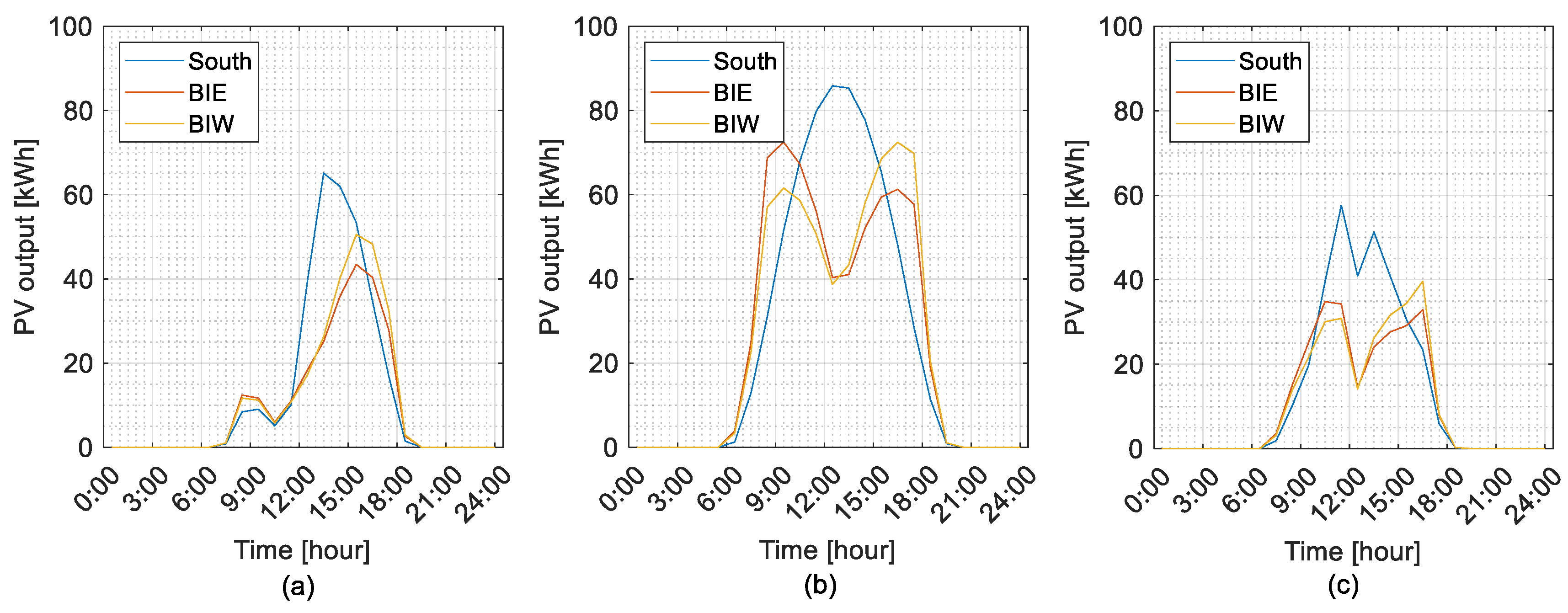

- All buses connected with mono-facial south-facing PV systems.

- All buses connected with bifacial PVs, with the front side facing east (BiE).

- All buses connected with bifacial PVs, with the front side facing west (BiW).

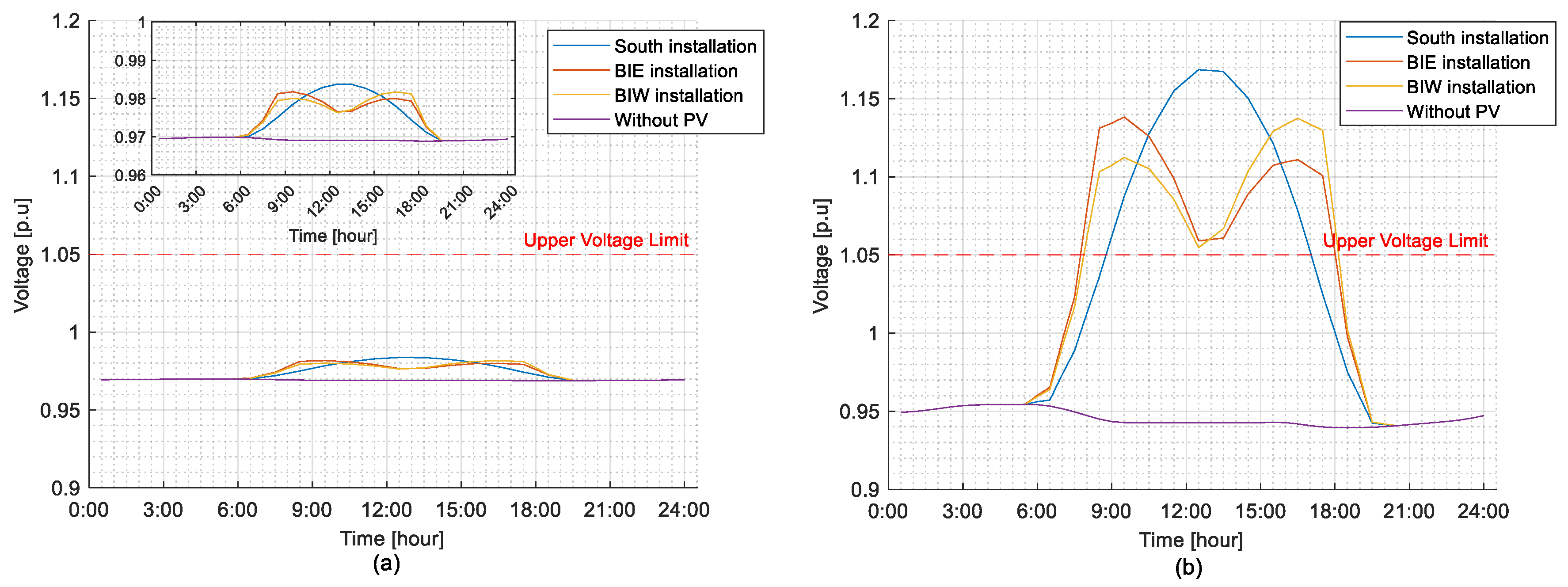

5. Simulation Results

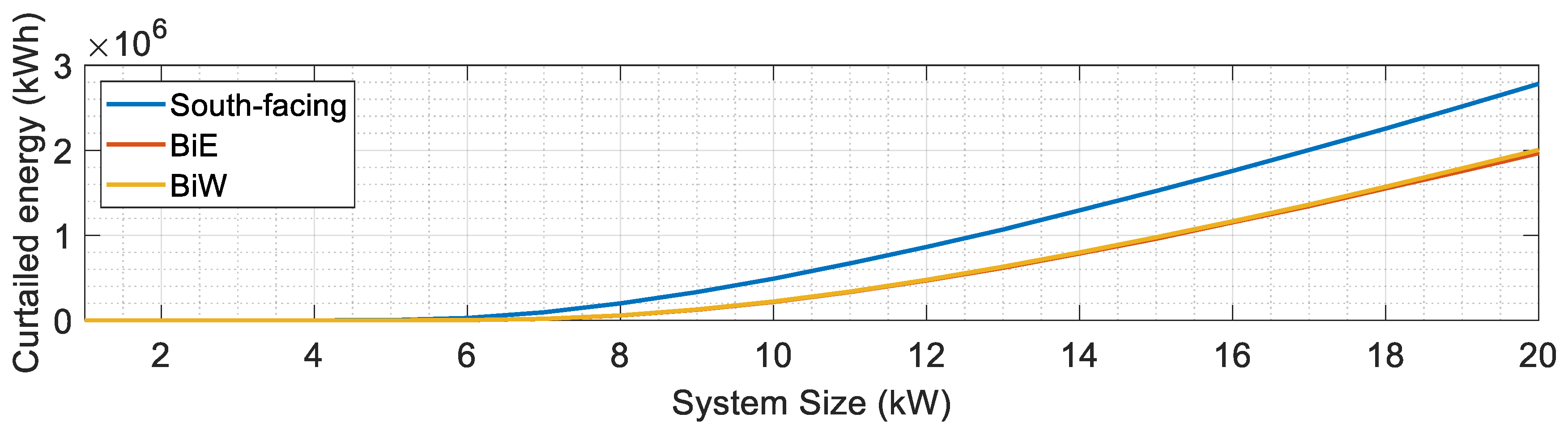

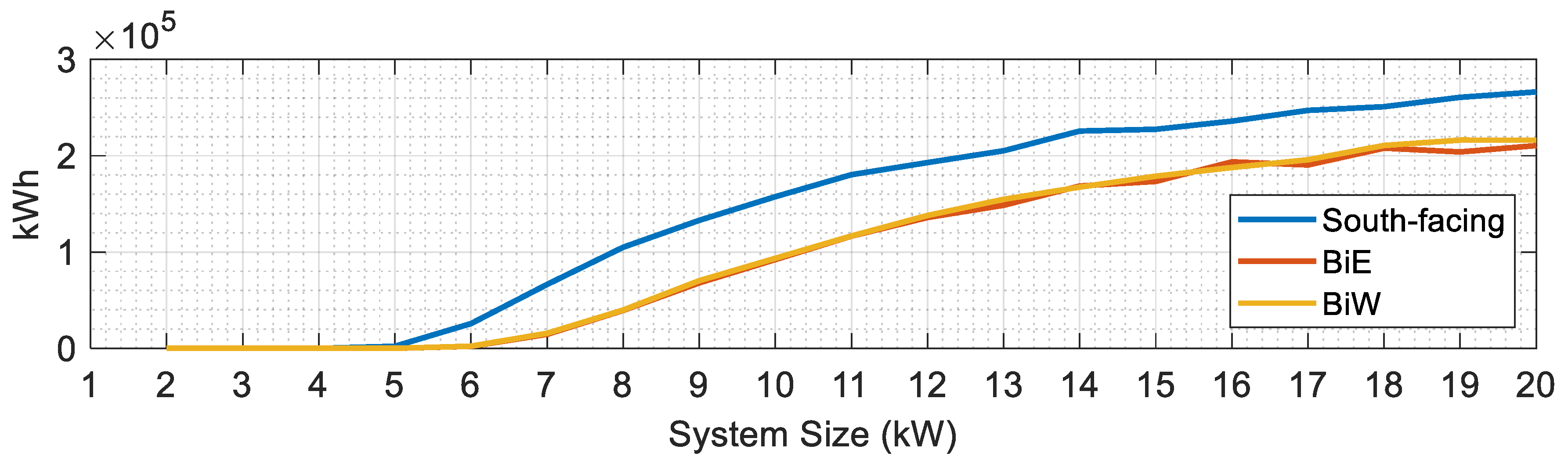

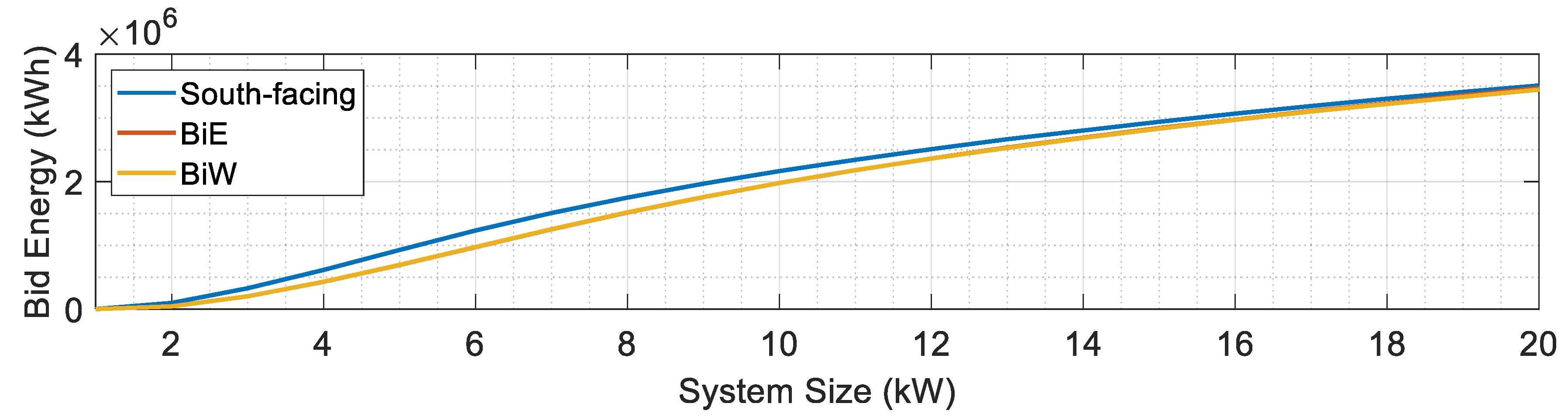

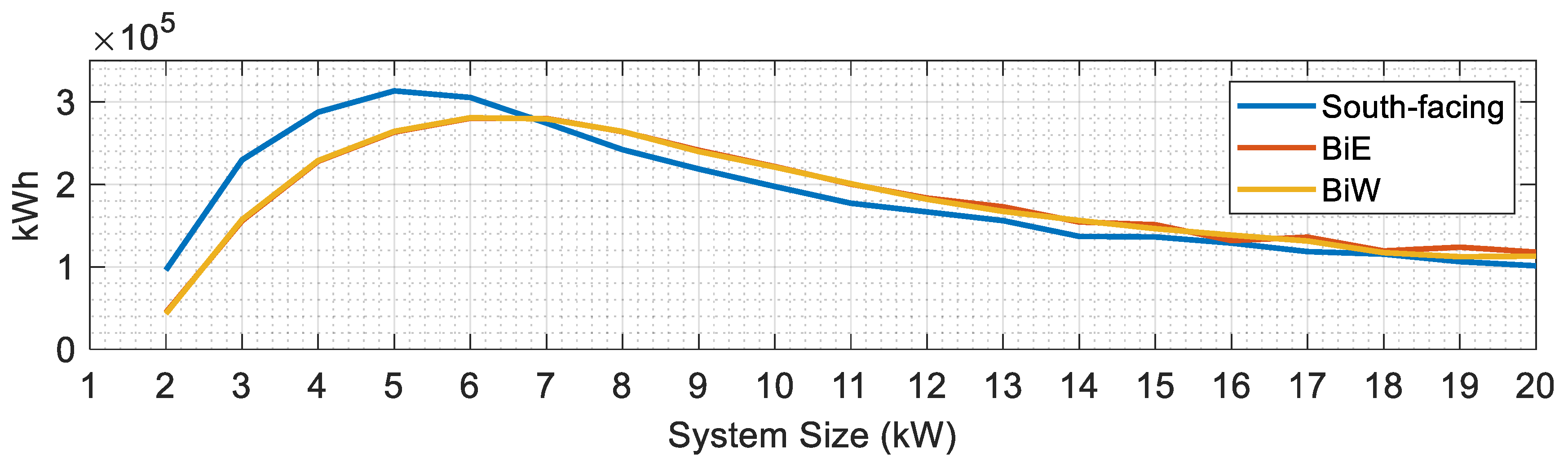

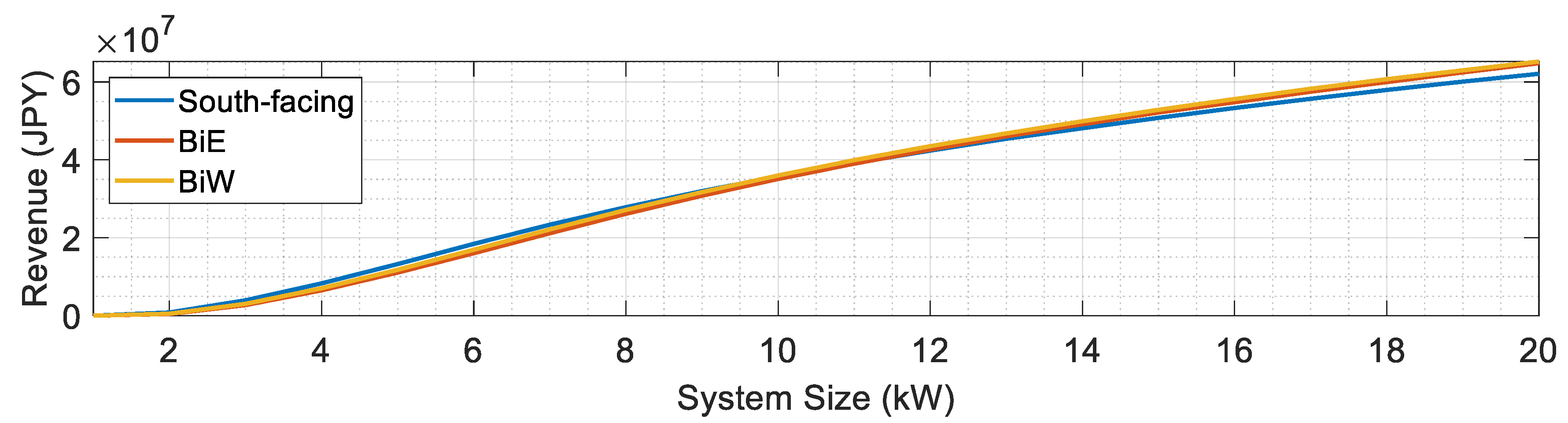

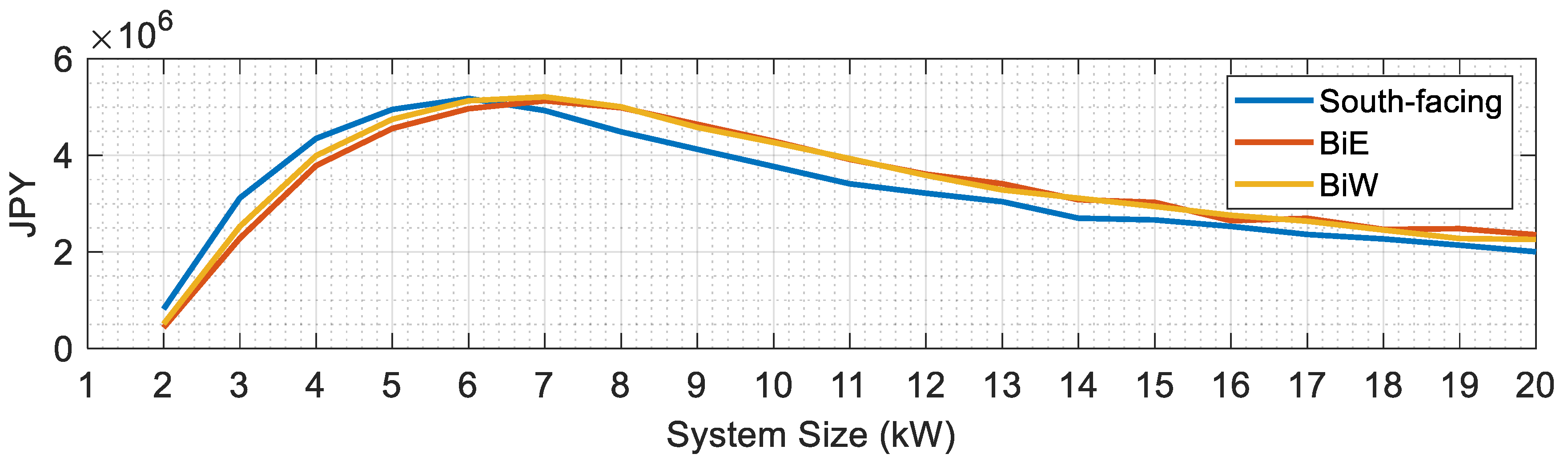

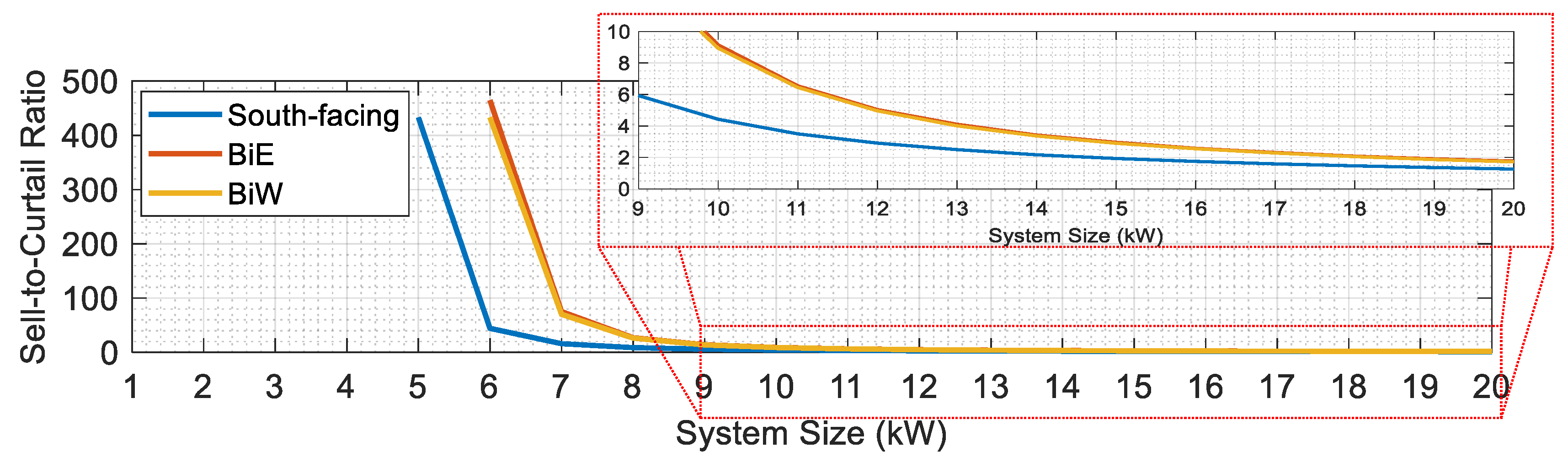

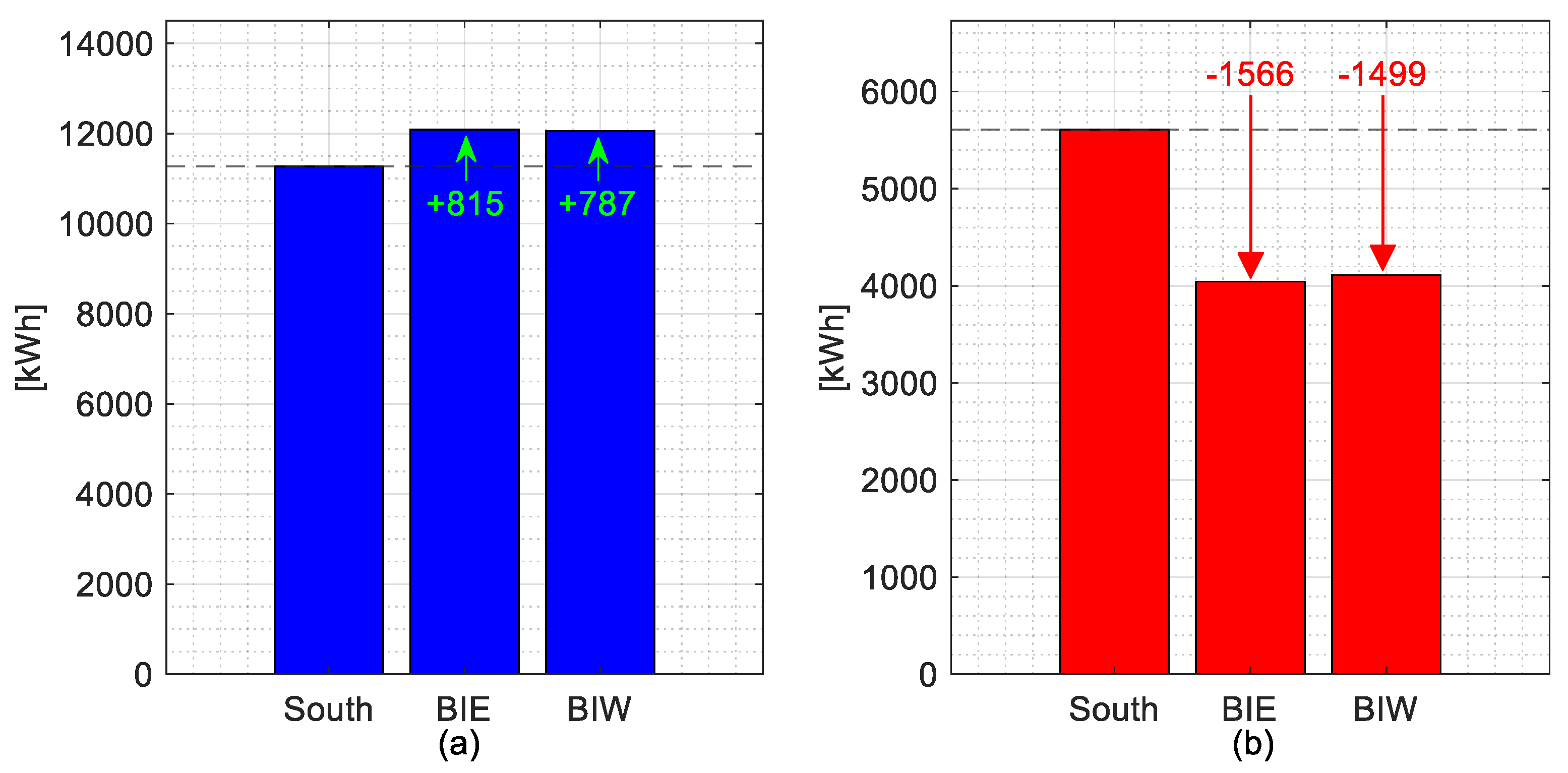

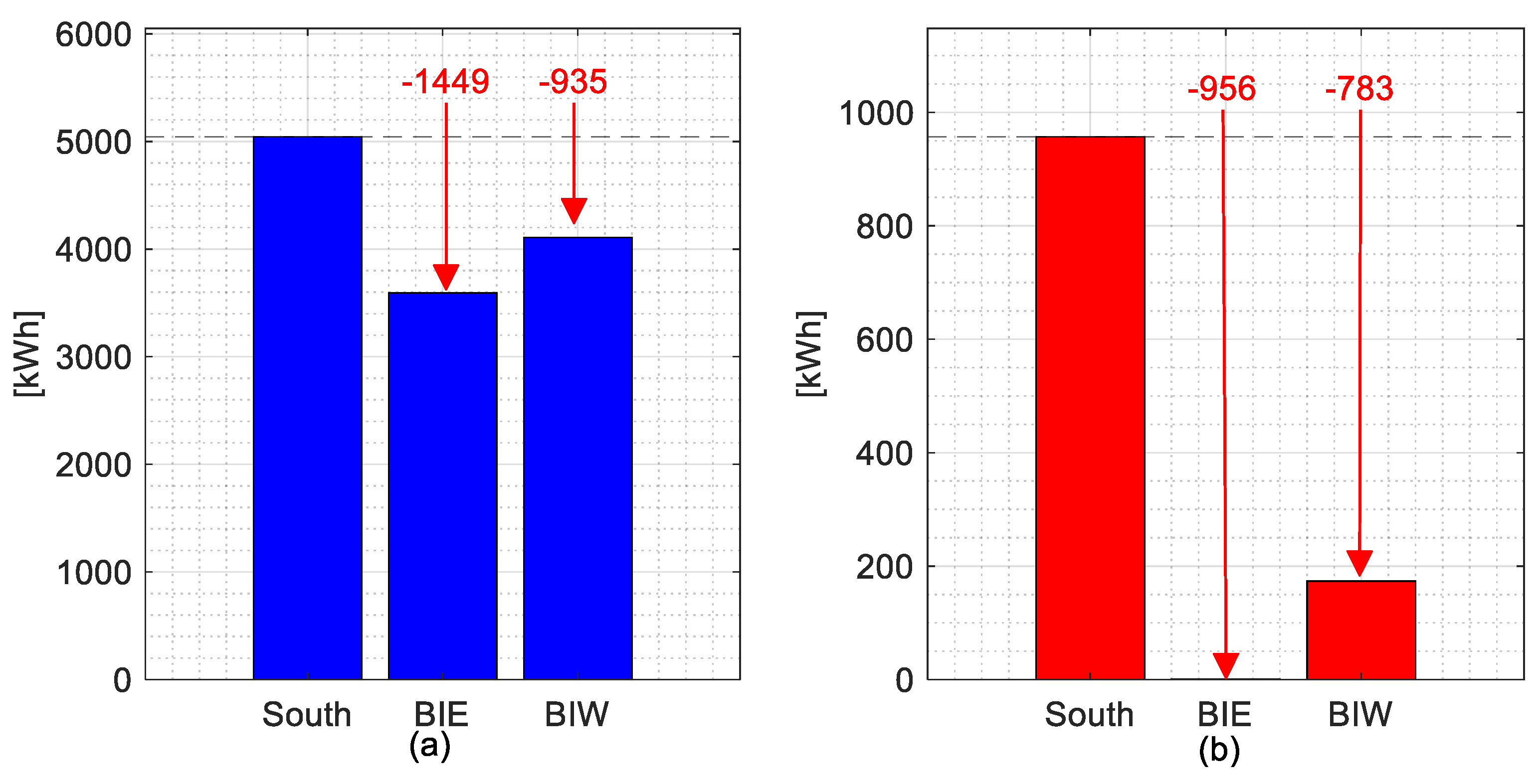

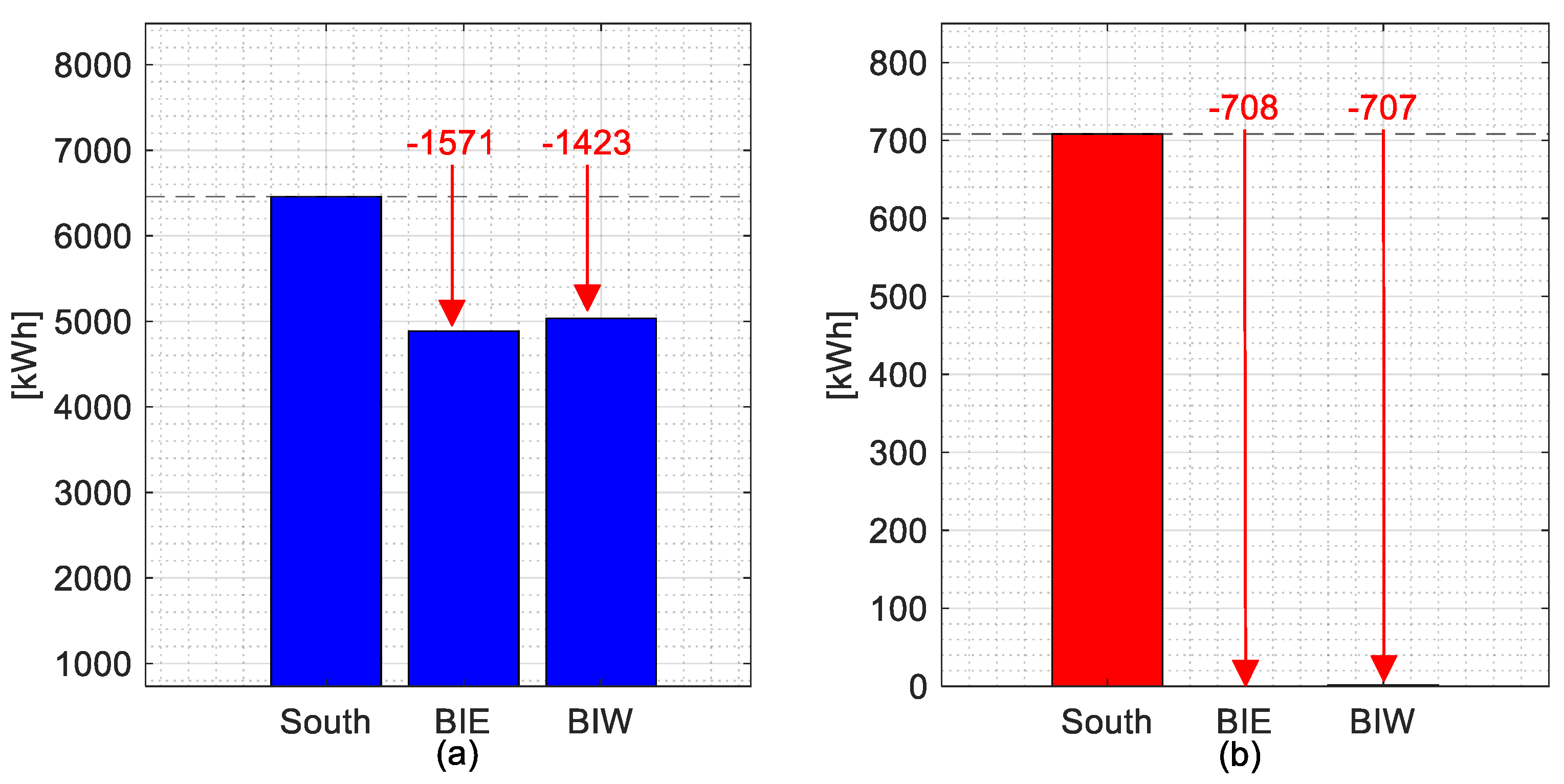

5.1. Performance Analysis Across Different PV Capacities

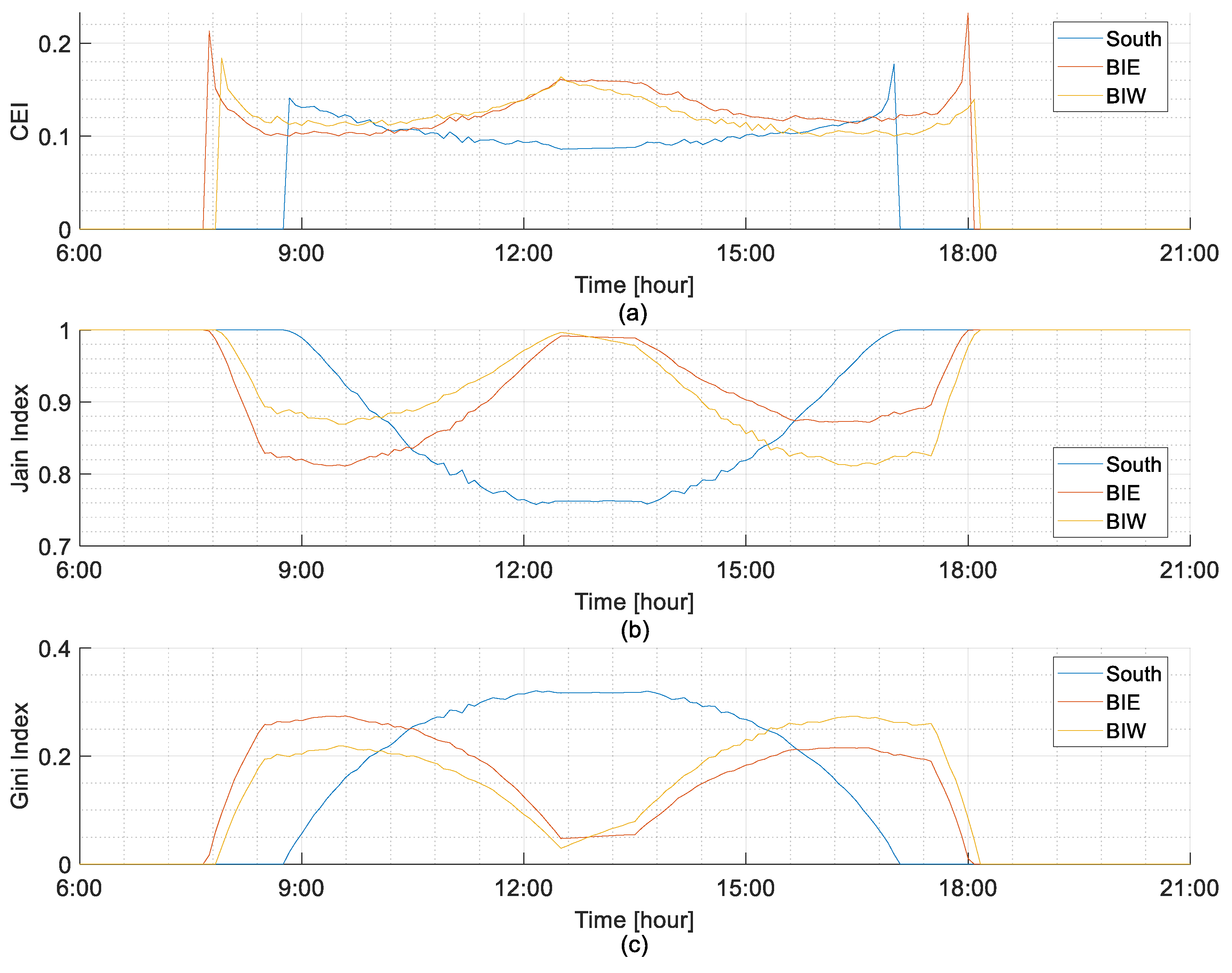

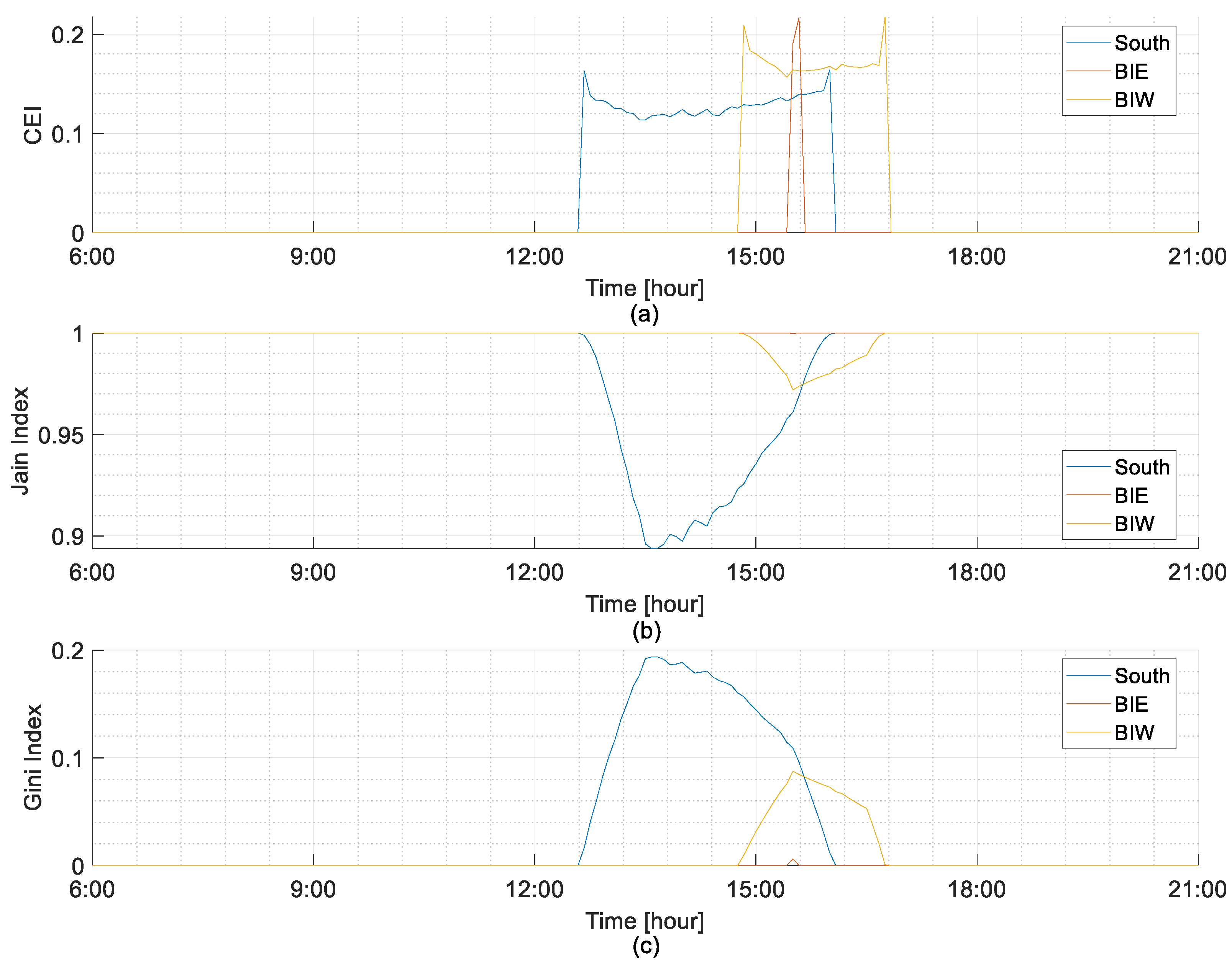

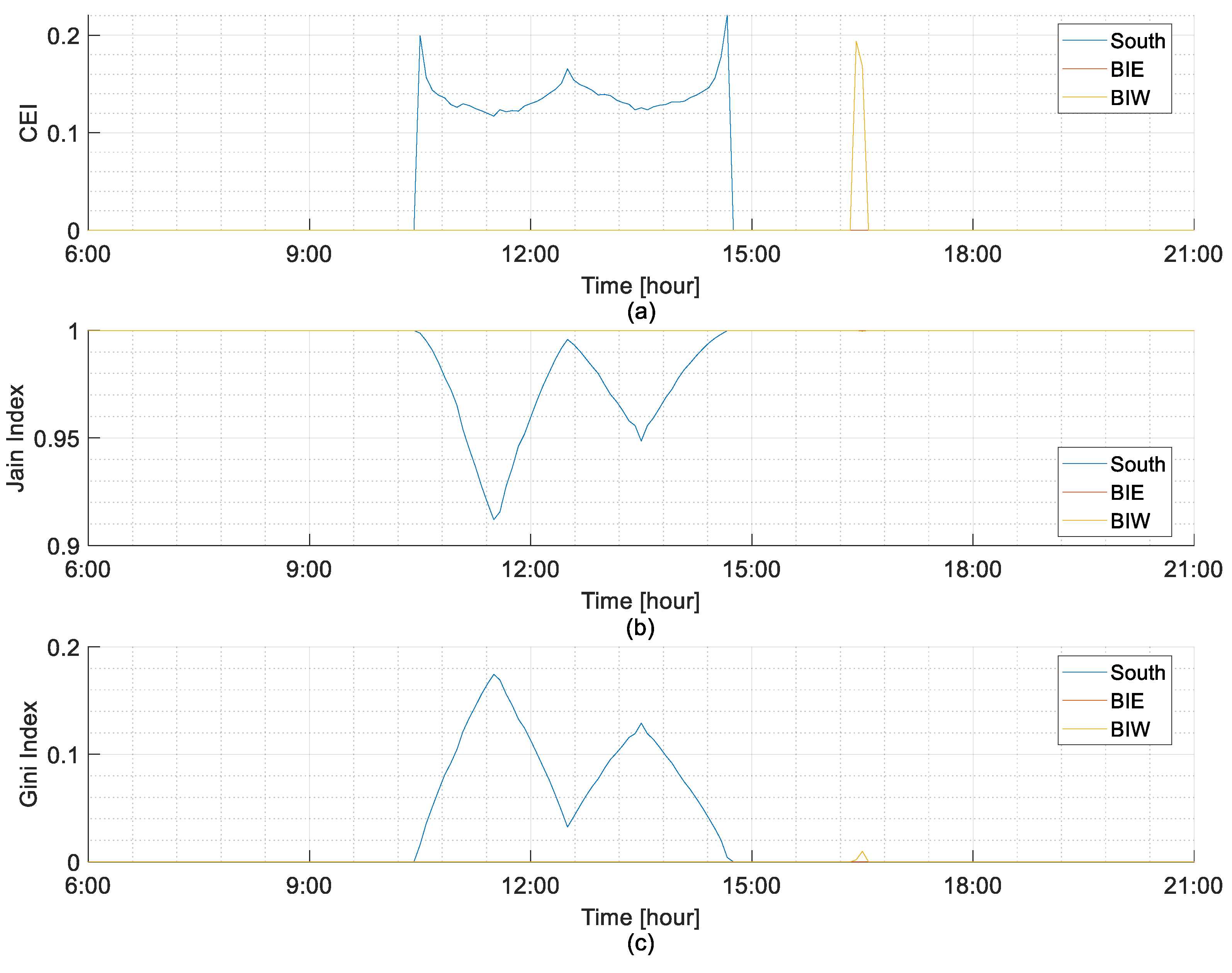

5.2. Fairness Evaluation at 10 kW Installation Capacity

5.2.1. Highest Curtailed Energy Day

5.2.2. Lowest Curtailed Energy Days Considering BiE and BiW Installations

6. Conclusions

References

- G. Masson et al., Snapshot of Global PV Markets 2023 Task 1 Strategic PV Analysis and Outreach PVPS. 2023.

- M. Z. Liu et al., “On the Fairness of PV Curtailment Schemes in Residential Distribution Networks,” IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 4502–4512, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Alboaouh and S. Mohagheghi, “Impact of Rooftop Photovoltaics on the Distribution System,” Journal of Renewable Energy, vol. 2020, no. 1, p. 4831434, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Anzalchi, A. Sundararajan, A. Moghadasi, and A. Sarwat, “High-Penetration Grid-Tied Photovoltaics: Analysis of Power Quality and Feeder Voltage Profile,” IEEE Industry Applications Magazine, vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 83–94, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Yildiz et al., Curtailment and network voltage analysis study. 2021, p. 5. [CrossRef]

- V. Sharma, S. M. Aziz, M. H. Haque, and T. Kauschke, “Effects of high solar photovoltaic penetration on distribution feeders and the economic impact,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 131, p. 110021, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. O’Shaughnessy, J. R. Cruce, and K. Xu, “Too much of a good thing? Global trends in the curtailment of solar PV,” Solar Energy, vol. 208, pp. 1068–1077, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Attarha, P. Scott, and S. Thiébaux, “Affinely Adjustable Robust ADMM for Residential DER Coordination in Distribution Networks,” IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 1620–1629, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- “IEEE Standard for Interconnection and Interoperability of Distributed Energy Resources with Associated Electric Power Systems Interfaces,” IEEE Std 1547-2018 (Revision of IEEE Std 1547-2003), pp. 1–138, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. Standard, “Grid connection of energy systems via inverters part 2: Inverter requirements,” tech. rep., 2015.

- M. S. Alonso, L. D. O. Arenas, D. I. Brandao, E. Tedeschi, and F. P. Marafao, “Integrated Local and Coordinated Overvoltage Control to Increase Energy Feed-In and Expand DER Participation in Low-Voltage Networks,” IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 1049–1061, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Poudel, M. Mukherjee, and A. P. Reiman, “A Fairness-Based Distributed Energy Coordination for Voltage Regulation in Distribution Systems,” in 2022 IEEE Green Technologies Conference (GreenTech), Mar. 2022, pp. 45–50. [CrossRef]

- S. Alyami, Y. Wang, C. Wang, J. Zhao, and B. Zhao, “Adaptive Real Power Capping Method for Fair Overvoltage Regulation of Distribution Networks With High Penetration of PV Systems,” IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 2729–2738, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Rankin and B. Colavizza, “Export limits for embedded generators up to 200 kVA connected at low voltage: standard operating procedure,” AusNet Services, 2017.

- K. Petrou et al., “Ensuring Distribution Network Integrity Using Dynamic Operating Limits for Prosumers,” IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 3877–3888, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. P. Networks, “LV Management Business Case (Business Case 5.18),” SA Power Networks, Adelaide, Australia, Phase 4 – 2020–25 Regulatory Proposal Supporting Document, Jan. 2019. Accessed: Feb. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.talkingpower.com.au/43062/widgets/230765/documents/172028.

- T. Procopiou, K. Petrou, L. F. Ochoa, T. Langstaff, and J. Theunissen, “Adaptive Decentralized Control of Residential Storage in PV-Rich MV–LV Networks,” IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 2378–2389, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Lankeshwara, “A Real-time Control Approach to Maximise the Utilisation of Rooftop PV Using Dynamic Export Limits,” in 2021 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies - Asia (ISGT Asia), Dec. 2021, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Australian Renewable Energy Agency, “Advanced VPP Grid Integration.” Accessed: Dec. 10, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://arena.gov.au/projects/advanced-vpp-grid-integration/.

- R. Golden and B. Paulos, “Curtailment of Renewable Energy in California and Beyond,” The Electricity Journal, vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 36–50, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- E. O’Shaughnessy, J. Cruce, and K. Xu, “Rethinking solar PV contracts in a world of increasing curtailment risk,” Energy Economics, vol. 98, p. 105264, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Gebbran, S. Mhanna, Y. Ma, A. C. Chapman, and G. Verbič, “Fair coordination of distributed energy resources with Volt-Var control and PV curtailment,” Applied Energy, vol. 286, p. 116546, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Golub et al., “Determination of the Installation Efficiency of Vertical Stationary Photovoltaic Modules with a Double-Sided ‘East–West’-Oriented Solar Panel,” Applied Sciences, vol. 15, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. Baumann, H. Nussbaumer, M. Klenk, A. Dreisiebner, F. Carigiet, and F. Baumgartner, “Photovoltaic systems with vertically mounted bifacial PV modules in combination with green roofs,” Solar Energy, vol. 190, pp. 139–146, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Baricchio, M. Korevaar, P. Babal, and H. Ziar, “Modelling of bifacial photovoltaic farms to evaluate the profitability of East/West vertical configuration,” Solar Energy, vol. 272, p. 112457, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Agency of Natural Resources and Energy, “Approach to the Energy policy toward 2030,” Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), Tokyo, Document 5,40th Meeting, Basic Policy Subcommittee, Advisory Committee for Natural Resources and Energy 040_005, Apr. 2021. Accessed: Jan. 06, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/committee/council/basic_policy_subcommittee/2021/040/040_005.

- K. Hao, D. Ialnazov, and Y. Yamashiki, “GIS Analysis of Solar PV Locations and Disaster Risk Areas in Japan,” Front. Sustain., vol. 2, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Jouttijärvi, G. Lobaccaro, A. Kamppinen, and K. Miettunen, “Benefits of bifacial solar cells combined with low voltage power grids at high latitudes,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 161, p. 112354, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Damiani, N. N. Ishizaki, H. Sasaki, S. Feron, and R. R. Cordero, “Exploring super-resolution spatial downscaling of several meteorological variables and potential applications for photovoltaic power,” Sci Rep, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 7254, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, “Nexus between agriculture and photovoltaics (agrivoltaics, agriphotovoltaics) for sustainable development goal: A review,” Solar Energy, vol. 266, p. 112146, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Miskin et al., “Sustainable co-production of food and solar power to relax land-use constraints,” Nat Sustain, vol. 2, no. 10, pp. 972–980, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Imran and M. H. Riaz, “Investigating the potential of east/west vertical bifacial photovoltaic farm for agrivoltaic systems,” Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy, vol. 13, no. 3, p. 033502, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Duffie and W. A. Beckman, “Available Solar Radiation,” in Solar Engineering of Thermal Processes, 4th ed., John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2013, pp. 43–137. [CrossRef]

- Yang, “Solar radiation on inclined surfaces: Corrections and benchmarks,” Solar Energy, vol. 136, pp. 288–302, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Liu and R. Jordan, “Daily insolation on surfaces tilted towards equator,” ASHRAE J.; (United States), vol. 10, Oct. 1961, Accessed: Apr. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.osti.gov/biblio/5047843.

- Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, “Guidelines on Technical Requirements for Grid Connection to Ensure Power Quality,” Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, Tokyo, Japan, Guideline (revised edition), Apr. 2023. Accessed: Jan. 06, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/category/electricity_and_gas/electric/summary/regulations/pdf/keito_renkei_20230401.pdf.

- C. Bucher et al., “Active Power Management of Photovoltaic Systems – State of the Art and Technical Solutions,” International Energy Agency, Photovoltaic Power Systems Programme (IEA PVPS), Task 14, Paris, Report IEA-PVPS T14-15:2024, Jan. 2024. Accessed: Apr. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://iea-pvps.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/IEA-PVPS-T14-15-REPORT-Active-Power-Management.pdf.

- Z. Wei, F. de Nijs, J. Li, and H. Wang, “Model-Free Approach to Fair Solar PV Curtailment Using Reinforcement Learning,” in Proceedings of the 14th ACM International Conference on Future Energy Systems, Jun. 2023, pp. 14–21. [CrossRef]

- S. Alyami and C. Wang, “Renewable Curtailment Fairness in Distribution Networks: Application of Division Rules,” in 2022 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Jul. 2022, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Gupta and D. K. Molzahn, “Analysis of Fairness-promoting Optimization Schemes of Photovoltaic Curtailments for Voltage Regulation in Power Distribution Networks,” Mar. arXiv, arXiv:arXiv:2404.00394. [CrossRef]

- M. Vassallo, A. M. Vassallo, A. Benzerga, A. Bahmanyar, and D. Ernst, “Fair Reinforcement Learning Algorithm for PV Active Control in LV Distribution Networks,” in 2023 International Conference on Clean Electrical Power (ICCEP), Jun. 2023, pp. 796–802. [CrossRef]

- Advanced Collaborative Research Organization for Smart Society (ACROSS), Waseda University, “‘JST-CREST 126 Distribution Feeder Model’ is Published.” Accessed: Apr. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.waseda.jp/inst/across/news-en/2554.

- Power and Energy Society, The Institute of Electrical Engineers of Japan, “Regional Supply System Model (Base Model) – Overview.” Accessed: Apr. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.iee.jp/pes/ele_systems/base_model/overview/.

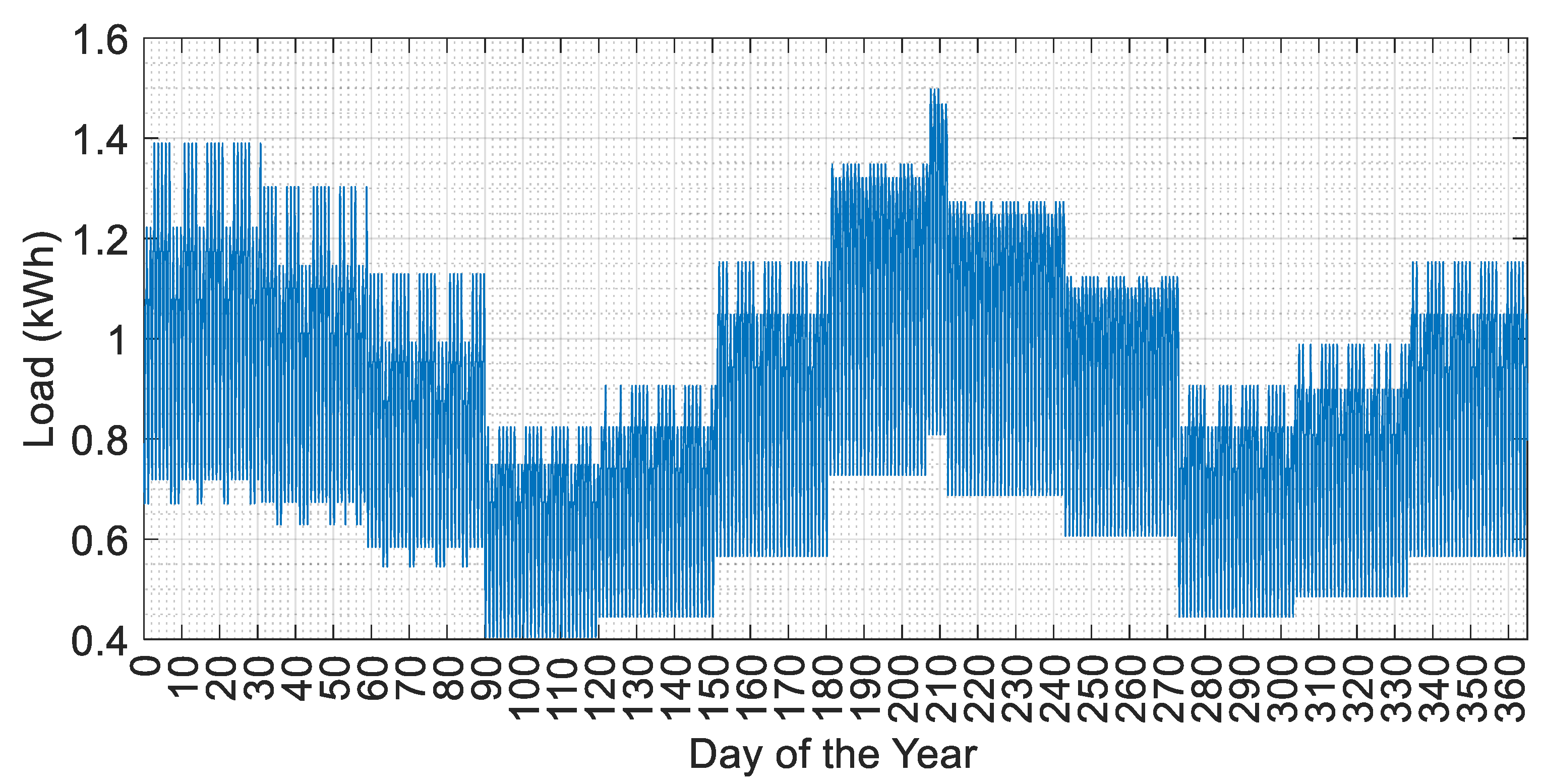

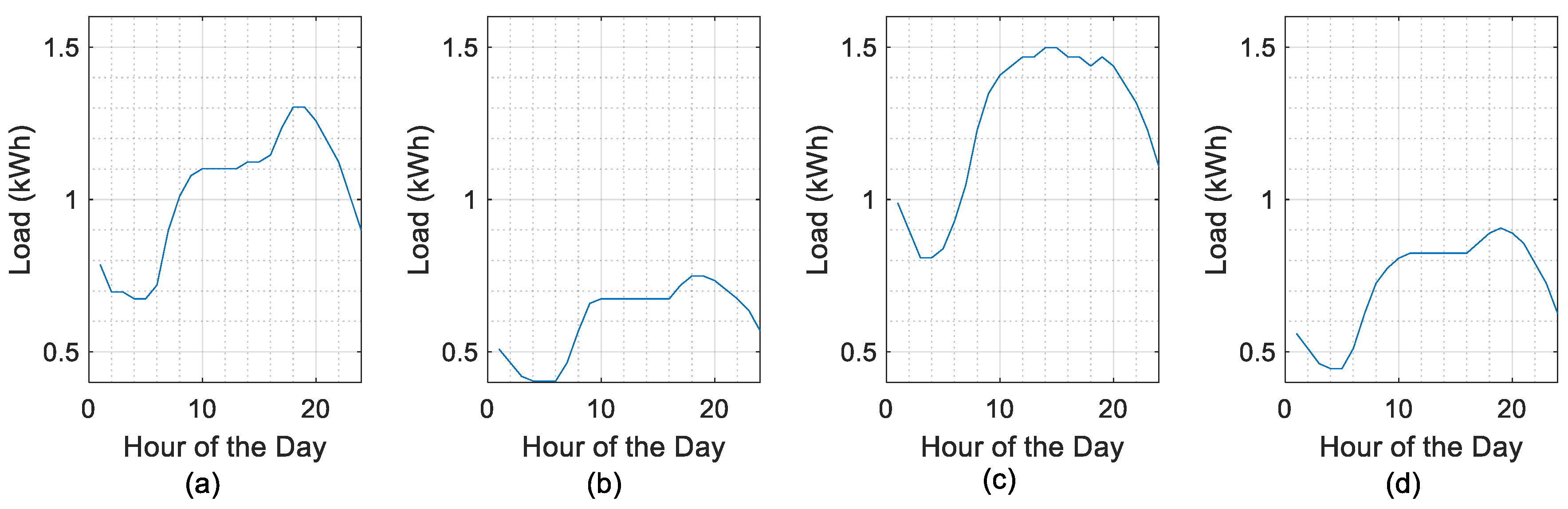

- F. P. Statistics Survey Division, “Electricity Consumption and Costs in Fukui under Rising Prices,” Fukui Prefecture, Statistics Survey Division, Fukui, Japan, FukuStat Statistics Letter, Jul. 2023. Accessed: Apr. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.pref.fukui.lg.jp/doc/toukei-jouhou/spot/fukustat_d/fil/202307_fukustat.pdf.

- Japan Meteorological Agency, “Past Weather Data Download Service (ObsDL).” Accessed: Dec. 21, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.data.jma.go.jp/risk/obsdl/index.php.

- Japan Electric Power Exchange, “Japan Electric Power Exchange (JEPX) – Official Website.” Accessed: Apr. 12, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.jepx.jp/.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).