Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

18 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

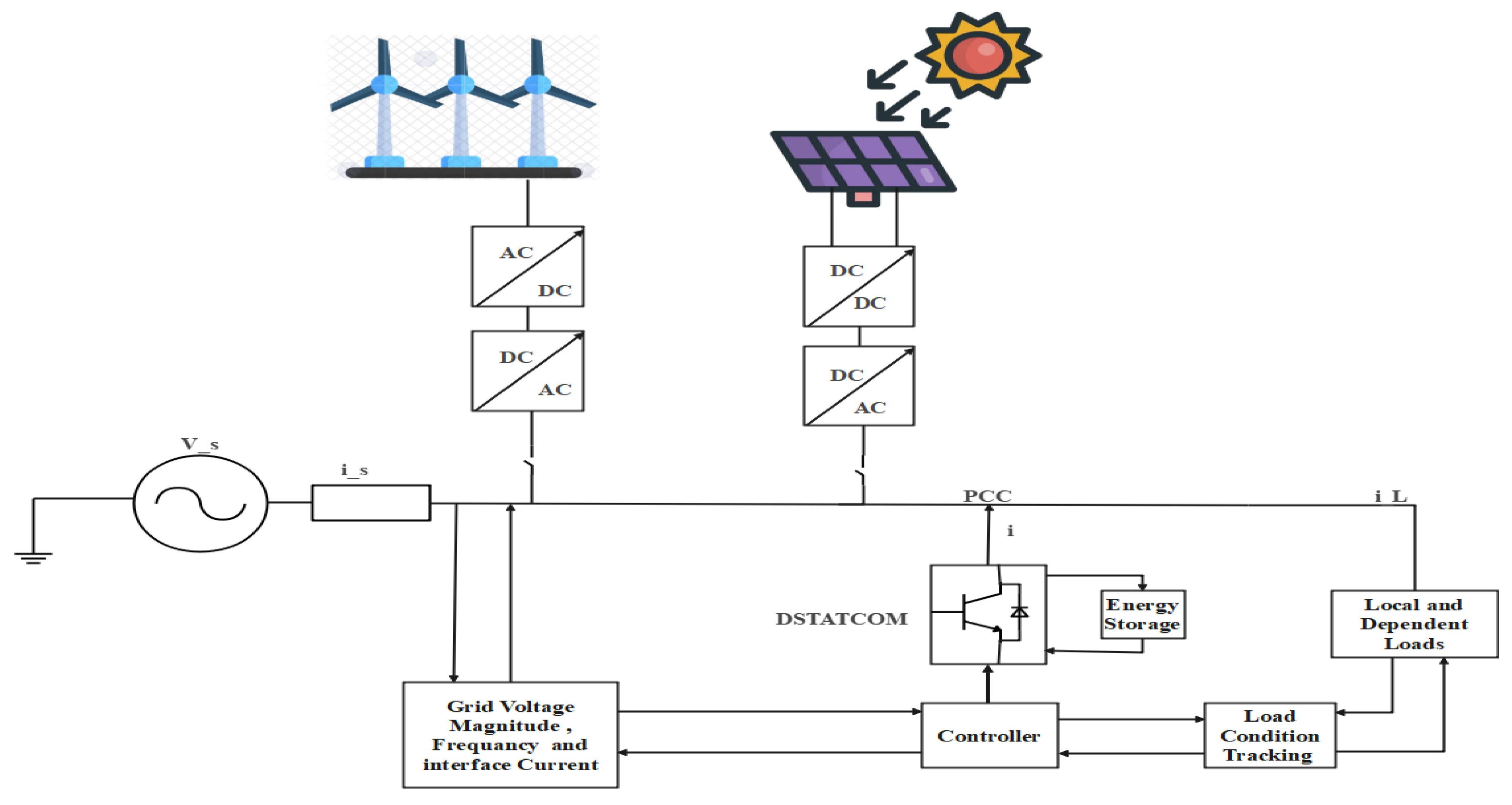

2.1. System Configuration

2.2. Modeling of System Components

2.3. Real Power Loss Formulation

2.4. Dynamic Voltage Resilience Margin Deviation (DVRMD)

2.5. Voltage Stability Index (VSI)

2.6. Loss Sensitivity Factor (LSF)

4. Objectives and System Constraints

4.1. Objective Function

- 1) Dynamic Active Power Loss Minimization

- 2) Dynamic Reactive Power Loss Minimization

- 3) Voltage Resilience Enhancement

- 4)

- Total Cost Minimization

- 5)

- Multi-Objective Formulation

4.2. System Constraints

4.2.1. Equality Constraints

- Real power balance at each bus

4.2.2. Inequality Constraints

- B.

- Voltage Limit Constraint

- C.

- Active power limit constraints

- D.

- Reactive Power Limits constraint

- E.

- Design Variables constraints

4.3. HGA-PSO Algorithms

4.3. Site Description and System Specifications

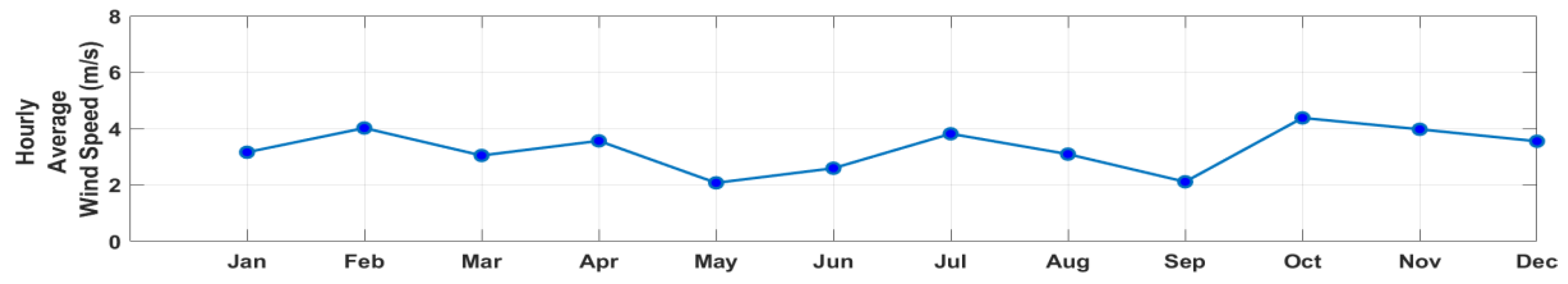

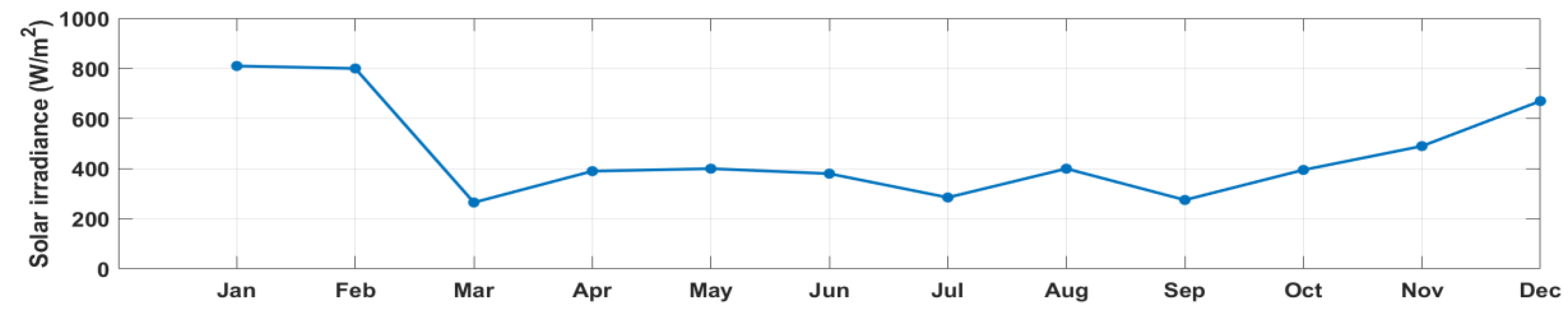

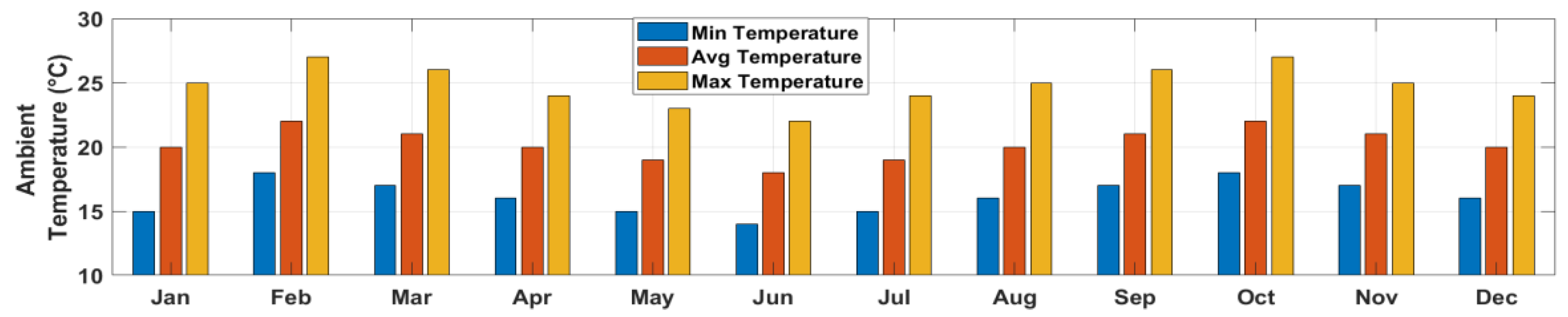

4.3.1. Geographical Location and Climatic Conditions

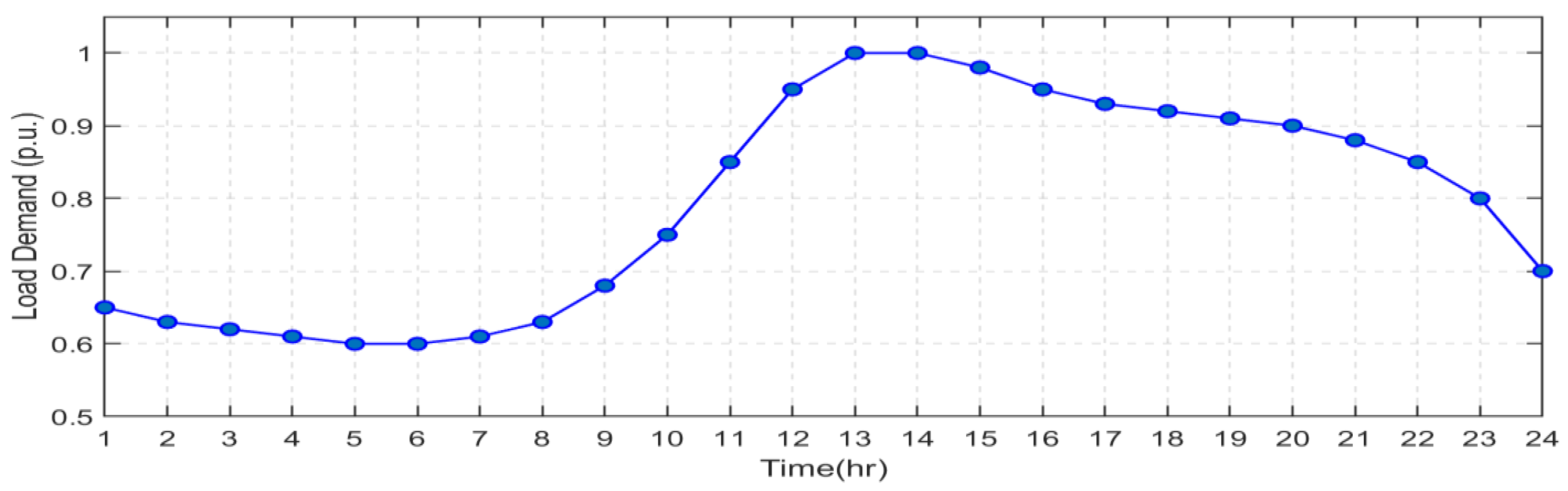

4.3.2. Load Characteristics

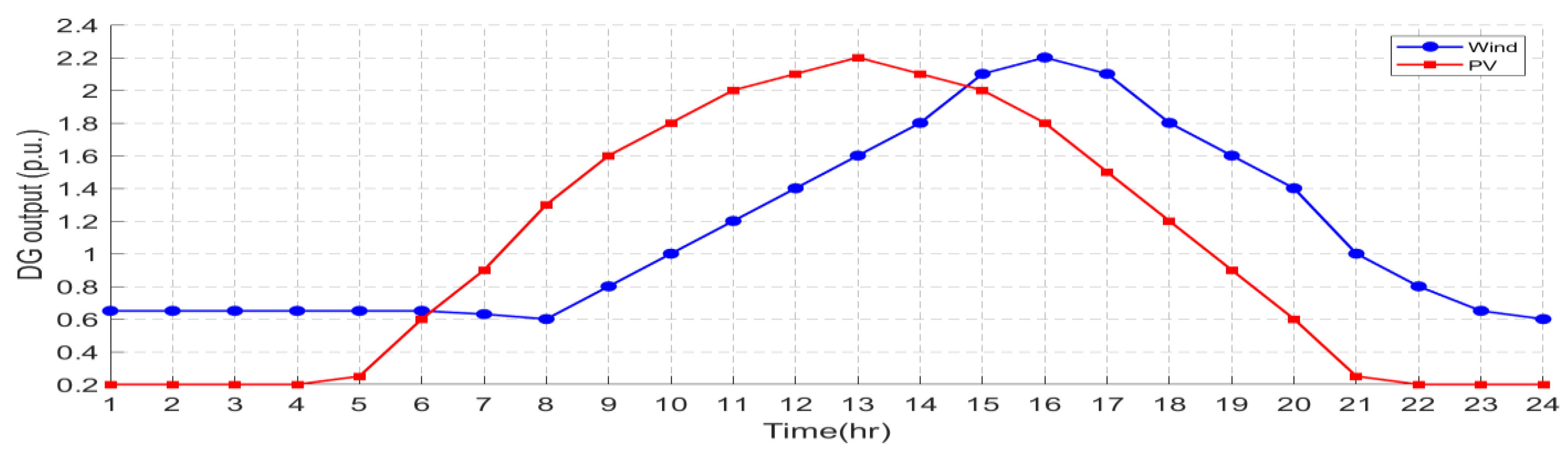

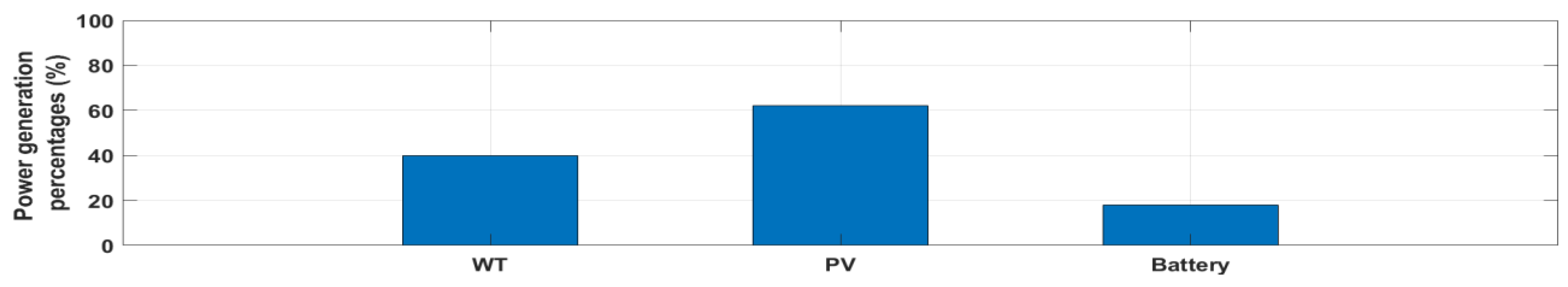

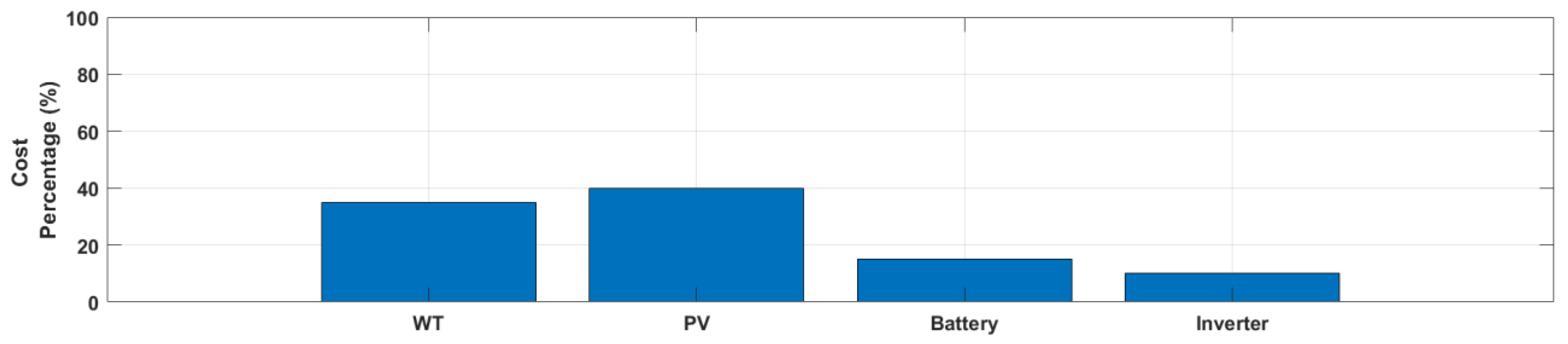

4.5. PV and WT-Integrated Grid Energy Generation System

5. Simulation Results and Discussions

| HGA Parameters | Size of populations | 30 | ||

| A Gaussian distribution | [1.8,0.01] | |||

| Mutation rate | 0.05 | |||

| Shape parameter | 6 | |||

| PSO Parameters | Size of the swarm (population). | 30 | ||

| The particle's weight due to inertia | 0.4 | |||

| Cognitive Coefficient ( ) | 2.5 | |||

| Social Coefficient ( ) | 1.5 | |||

| Randomly generated numbers ( ) | ||||

| Constriction factor ( ) | 0.729 | |||

| Decision variables | Bus number | Size (MW) | Location | |

| Boundary | Lower bound | 2 | 0 | Higher LSF prioritize candidate bus selection. |

| Upper bound | 139 | 4.876 |

| Best function value | ||||

| 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.039631 |

| 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.037616 |

| 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.037516 |

| 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.037017 |

| 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.036961 |

| 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.033632 |

| 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.02569 |

| 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.02366 |

| 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.02318 |

| 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.02268 |

5.1. Interpretation of Simulation Results

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CIR | Cut in Ratio |

| DSTATCOM | distribution static synchronous compensator |

| HGA | Hybrid genetic algorithms |

| LSF | Loss sensitivity factor |

| PSO | particle swarm optimization |

| PV | photovoltaic |

| RDS | Radial distribution system |

| RES | renewable energy sources |

| VSI | Voltage stability index |

| WT | Wind turbine |

References

- X. Li, D. Lepour, F. Heymann, and F. Maréchal, “Electrification and digitalization effects on sectoral energy demand and consumption: A prospective study towards 2050,” Energy, vol. 279, p. 127992, 2023. 10.1016/j.energy.2023.127992.

- M. M. Haque and P. Wolfs, “A review of high PV penetrations in LV distribution networks: Present status, impacts and mitigation measures,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 62, pp. 1195–1208, 2016. 10.1016/j.rser.2016.04.025.

- C. D. Iweh, S. Gyamfi, E. Tanyi, and E. Effah-Donyina, “Distributed generation and renewable energy integration into the grid: Prerequisites, push factors, practical options, issues and merits,” Energies, vol. 14, no. 17, p. 5375, 2021. 10.3390/en14175375.

- S. Singh and S. Singh, “Advancements and challenges in integrating renewable energy sources into distribution grid systems: A comprehensive review,” J. Energy Resour. Technol., vol. 146, no. 9, 2024.

- M. Bajaj and A. K. Singh, “Grid integrated renewable DG systems: A review of power quality challenges and state-of-the-art mitigation techniques,” Int. J. Energy Res., vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 26–69, 2020.

- M. Motalleb, E. Reihani, and R. Ghorbani, “Optimal placement and sizing of the storage supporting transmission and distribution networks,” Renew. Energy, vol. 94, pp. 651–659, 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Wong, V. K. Ramachandaramurthy, P. Taylor, J. B. Ekanayake, S. L. Walker, and S. Padmanaban, “Review on the optimal placement, sizing and control of an energy storage system in the distribution network,” J. Energy Storage, vol. 21, pp. 489–504, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Chillab, A. S. Jaber, M. Ben Smida, and A. Sakly, “Optimal DG location and sizing to minimize losses and improve voltage profile using Garra Rufa optimization,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 2, p. 1156, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Hammons, “Integrating renewable energy sources into European grids,” Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst., vol. 30, no. 8, pp. 462–475, 2008. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Yousef, H. Yousef, and L. Rocha-Meneses, “Artificial intelligence for management of variable renewable energy systems: a review of current status and future directions,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 24, p. 8057, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Bisanovic, M. Hajro, and M. Samardzic, “One approach for reactive power control of capacitor banks in distribution and industrial networks,” Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst., vol. 60, pp. 67–73, 2014. [CrossRef]

- E. N. Mbinkar, D. A. Asoh, and S. Kujabi, “Microcontroller control of reactive power compensation for growing industrial loads,” Energy Power Eng., vol. 14, no. 9, pp. 460–476, 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. K. Govil, K. Sahay, and S. M. Tripathi, “Enhancing power quality through DSTATCOM: a comprehensive review and real-time simulation insights,” Electr. Eng., pp. 1–30, 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Sambaiah and T. Jayabarathi, “Loss minimization techniques for optimal operation and planning of distribution systems: A review of different methodologies,” Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst., vol. 30, no. 2, p. e12230, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Anbuchandran, A. Babu, and M. Thinakaran, “A hybrid optimization for distributed generation and D-STATCOM placement in radial distribution network: a multi-faceted evaluation,” Eng. Res. Express, vol. 6, no. 3, p. 35351, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. F. Raj and A. G. Saravanan, “An optimization approach for optimal location & size of DSTATCOM and DG,” Appl. Energy, vol. 336, p. 120797, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Nabaei et al., “Topologies and performance of intelligent algorithms: a comprehensive review,” Artif. Intell. Rev., vol. 49, pp. 79–103, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, S. Wang, and G. Ji, “A comprehensive survey on particle swarm optimization algorithm and its applications,” Math. Probl. Eng., vol. 2015, no. 1, p. 931256, 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. G. A. Njock, S.-L. Shen, A. Zhou, and G. Modoni, “Artificial neural network optimized by differential evolution for predicting diameters of jet grouted columns,” J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng., vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 1500–1512, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Naderi, H. Narimani, M. Pourakbari-Kasmaei, F. V Cerna, M. Marzband, and M. Lehtonen, “State-of-the-art of optimal active and reactive power flow: A comprehensive review from various standpoints,” Processes, vol. 9, no. 8, p. 1319, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Halve, S. S. Raghuwanshi, and D. Sonje, “Radial distribution system network reconfiguration for reduction in real power loss and improvement in voltage profile, and reliability,” J. Oper. Autom. Power Eng., 2024.

- A. N. Hussain, W. K. Shakir Al-Jubori, and H. F. Kadom, “Hybrid design of optimal capacitor placement and reconfiguration for performance improvement in a radial distribution system,” J. Eng., vol. 2019, no. 1, p. 1696347, 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Yang et al., “Optimal power flow in distribution network: A review on problem formulation and optimization methods,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 16, p. 5974, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Ding, C. Li, Y. Yang, R. Bo, and F. Blaabjerg, “Negative reactance impacts on the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix in power flow and type-1 low-voltage power-flow solutions,” IEEE Trans. Power Syst., vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 3471–3481, 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. Iqbal, M. T. Khan, and A. S. Siddiqui, “Optimal placement of DG and DSTATCOM for loss reduction and voltage profile improvement,” Alexandria Eng. J., vol. 57, no. 2, pp. 755–765, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Hasan et al., “Harnessing solar power: a review of photovoltaic innovations, solar thermal systems, and the dawn of energy storage solutions,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 18, p. 6456, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Hassan et al., “Evaluation of energy extraction of PV systems affected by environmental factors under real outdoor conditions,” Theor. Appl. Climatol., vol. 150, no. 1, pp. 715–729, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Shazdeh, H. Golpîra, and H. Bevrani, “Advanced and smart protection schemes in renewable integrated power systems: a survey and new perspectives,” Electr. Power Syst. Res., vol. 235, p. 110832, 2024. [CrossRef]

- O. Ayadi, R. Shadid, A. Bani-Abdullah, M. Alrbai, M. Abu-Mualla, and N. Balah, “Experimental comparison between Monocrystalline, Polycrystalline, and Thin-film solar systems under sunny climatic conditions,” Energy Reports, vol. 8, pp. 218–230, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Thönnißen, M. Marnett, B. Roidl, and W. Schröder, “A numerical analysis to evaluate Betz’s Law for vertical axis wind turbines,” in Journal of Physics: Conference Series, IOP Publishing, 2016, p. 22056.

- A. Sedaghat, A. Hassanzadeh, J. Jamali, A. Mostafaeipour, and W.-H. Chen, “Determination of rated wind speed for maximum annual energy production of variable speed wind turbines,” Appl. Energy, vol. 205, pp. 781–789, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Islam et al., “Improving reliability and stability of the power systems: A comprehensive review on the role of energy storage systems to enhance flexibility,” IEEE Access, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Ehsan and Q. Yang, “Optimal integration and planning of renewable distributed generation in the power distribution networks: A review of analytical techniques,” Appl. Energy, vol. 210, pp. 44–59, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Yenealem, “Optimum Allocation of Microgrid and D-STATCOM in Radial Distribution System for Voltage Profile Enhancement Using Particle Swarm Optimization,” Int. J. Photoenergy, vol. 2024, no. 1, p. 5550897, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Tuka and S. E. Ali, “Optimal allocation and sizing of distributed generation for improvement of distribution feeder loss and voltage profile in the distribution network using genetic algorithm,” Meas. Control, p. 00202940251323760, 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Jarso, G. Jin, and J. Ahn, “Hybrid Genetic Algorithm-Based Optimal Sizing of a PV–Wind–Diesel–Battery Microgrid: A Case Study for the ICT Center, Ethiopia,” Mathematics, vol. 13, no. 6, 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Gerbo, K. V. Suryabhagavan, and T. Kumar Raghuvanshi, “GIS-based approach for modeling grid-connected solar power potential sites: a case study of East Shewa Zone, Ethiopia,” Geol. Ecol. Landscapes, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 159–173, 2022. [CrossRef]

- X. Tang, K. N. Hasan, J. V Milanović, K. Bailey, and S. J. Stott, “Estimation and validation of characteristic load profile through smart grid trials in a medium voltage distribution network,” IEEE Trans. power Syst., vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 1848–1859, 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Zheng, X. Meng, L. Wang, and N. Zhang, “Operation optimization method of distribution network with wind turbine and photovoltaic considering clustering and energy storage,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 3, p. 2184, 2023. [CrossRef]

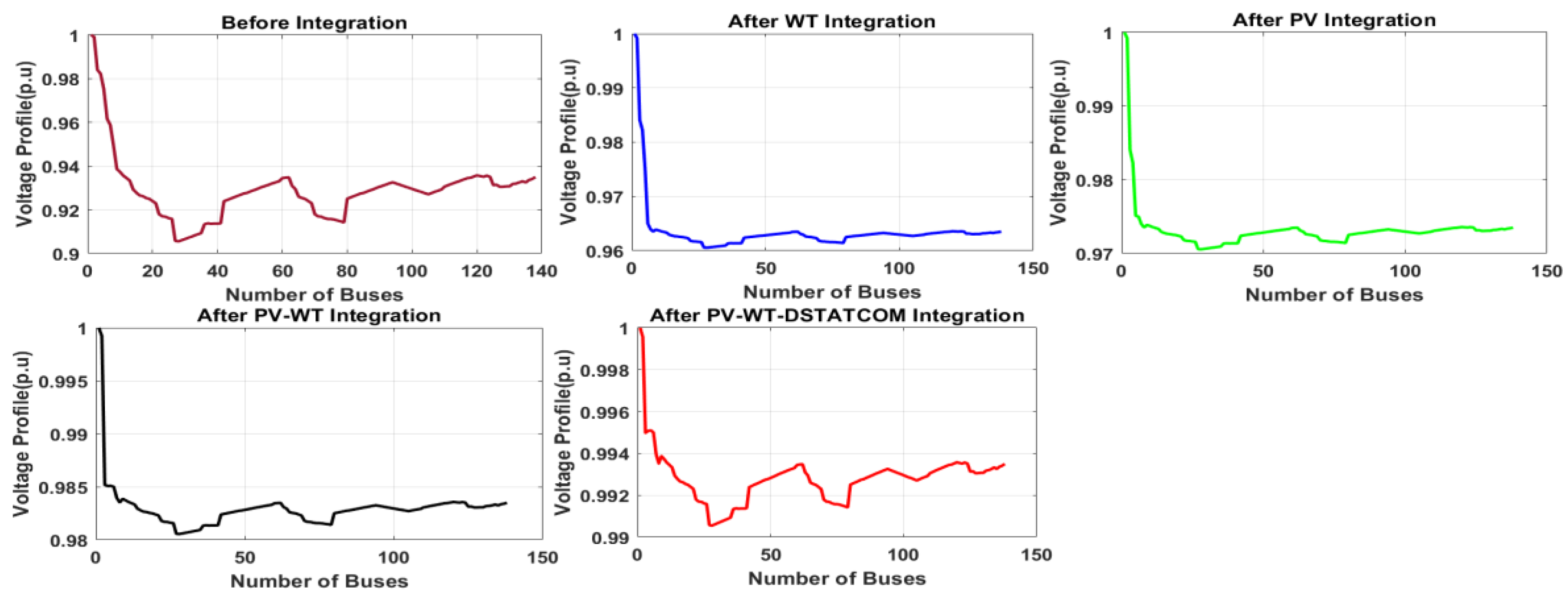

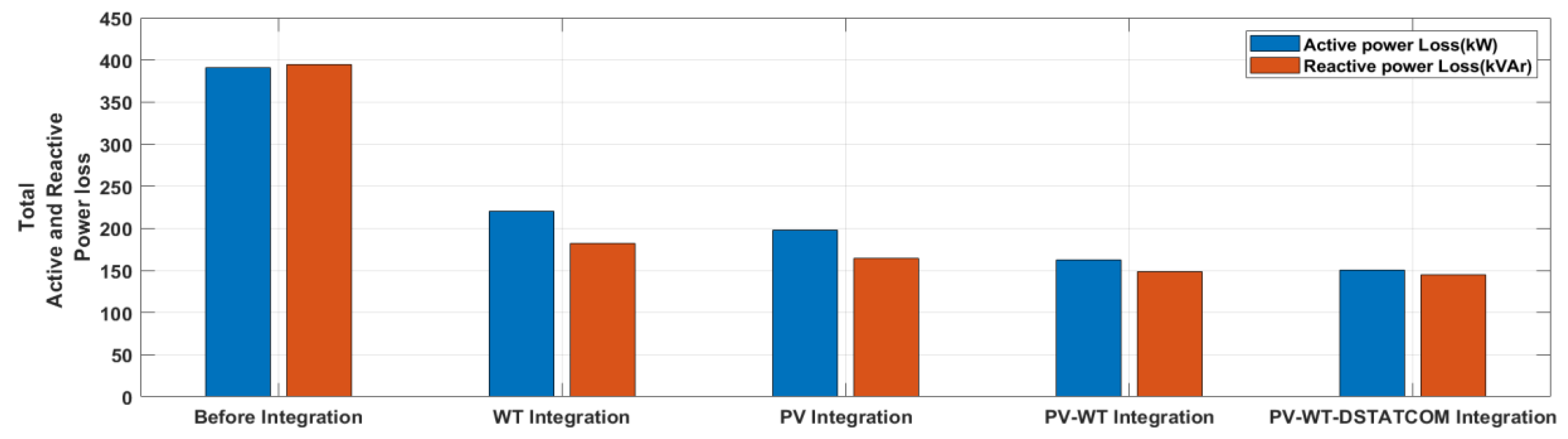

| Objectives | Before Integration |

After Integration | |||

| WT | PV | PV-WT | PV-WT-DSTACOM | ||

| Total active power loss (kW) | 390.9944 | 220.162 | 198.1035 | 162.6685 | 150.765 |

| Total active power loss red (%) | 43.69 | 49.33 | 58.39 | 61.44 | |

| Total reactive power loss (kVAr) | 394.895 | 182.60558 | 164.578 | 148.7415 | 145.2265 |

| Total reactive power loss red (%) | – | 53.76 | 58.32 | 62.33 | 63.22 |

| Minimum voltage (p.u.) | 0.9055 | 0.96055 | 0.97155 | 0.9821 | 0.99925 |

| Minimum V. deviation (%) | 9.45 | 3.945 | 2.845 | 1.79 | 0.075 |

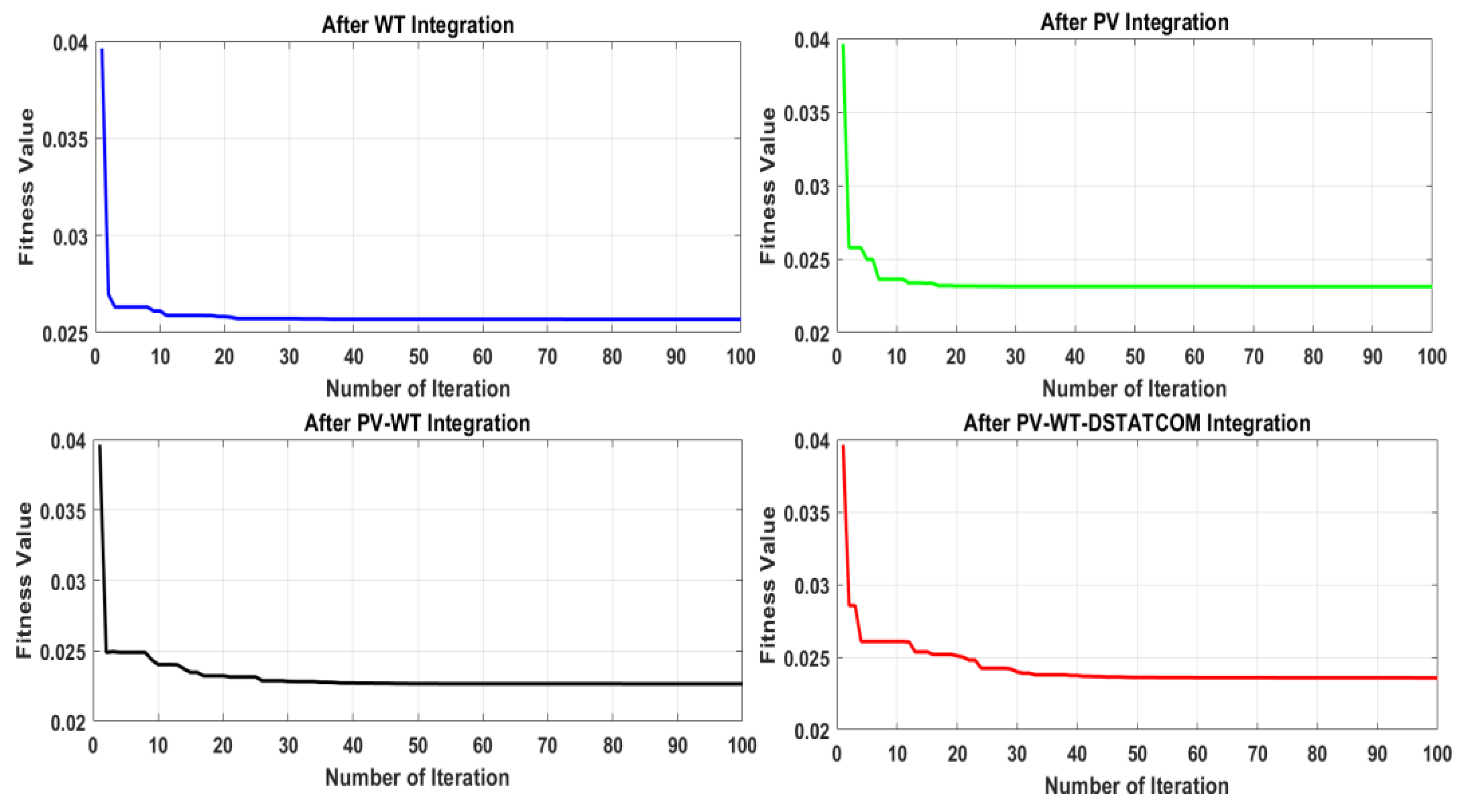

| Fitness Values | – | 0.02569 | 0.02318 | 0.02366 | 0.02268 |

| LSF (p.u.) | 0.92023 | 0.216401 | 0.079056 | 0.059799 | 0.036588 |

| DG location | – | 105 | 127 | 41 | 28 |

| VSI (p.u.) | 0.05232 | 0.06939 | 0.478401 | 0.556126 | 0.581077 |

| DG size (kVAr) | – | 861 | 1206 | 2067 | 3630 |

| Percentage for Cost allocation | - | 35 | 40 | 75 | 85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).