Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

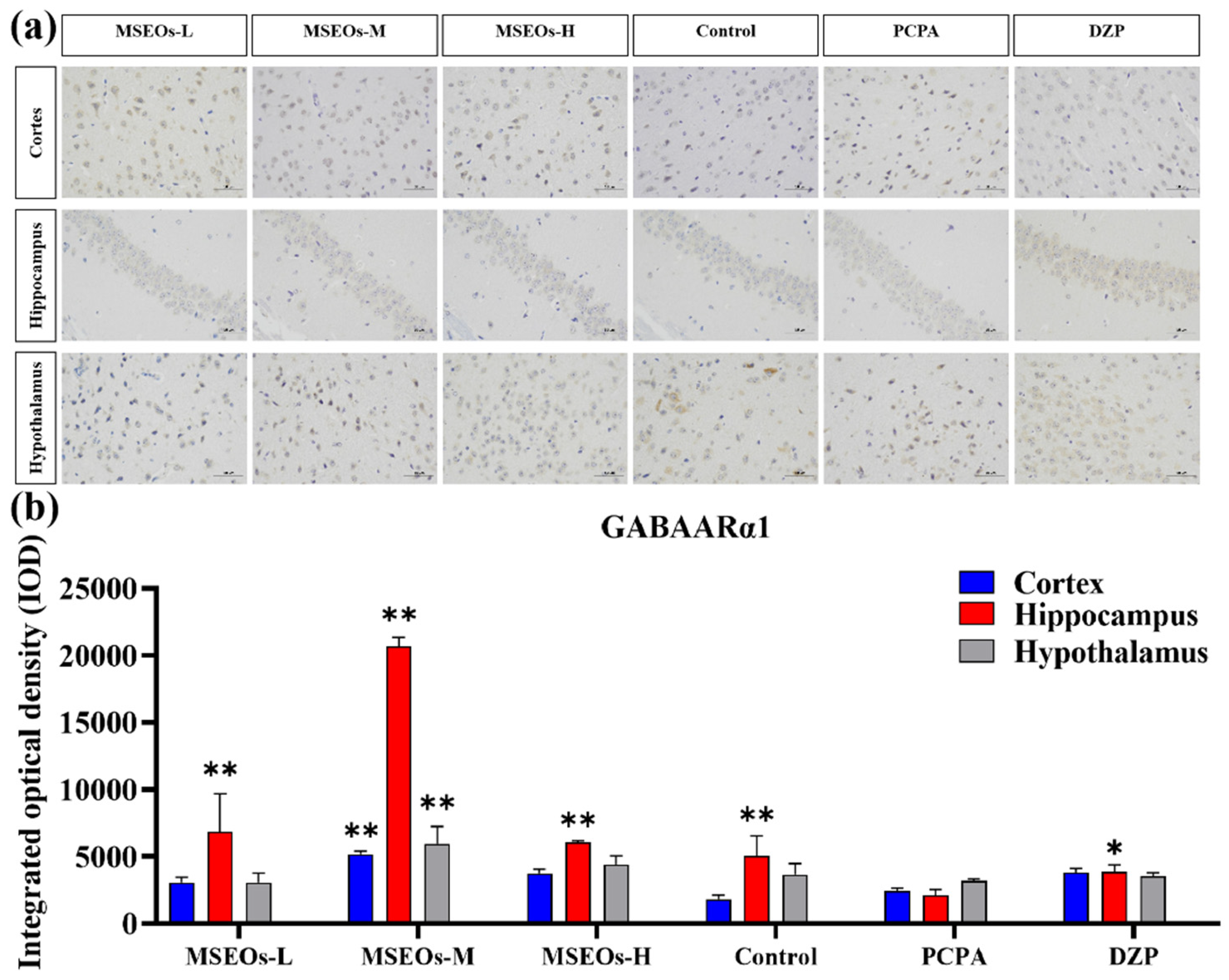

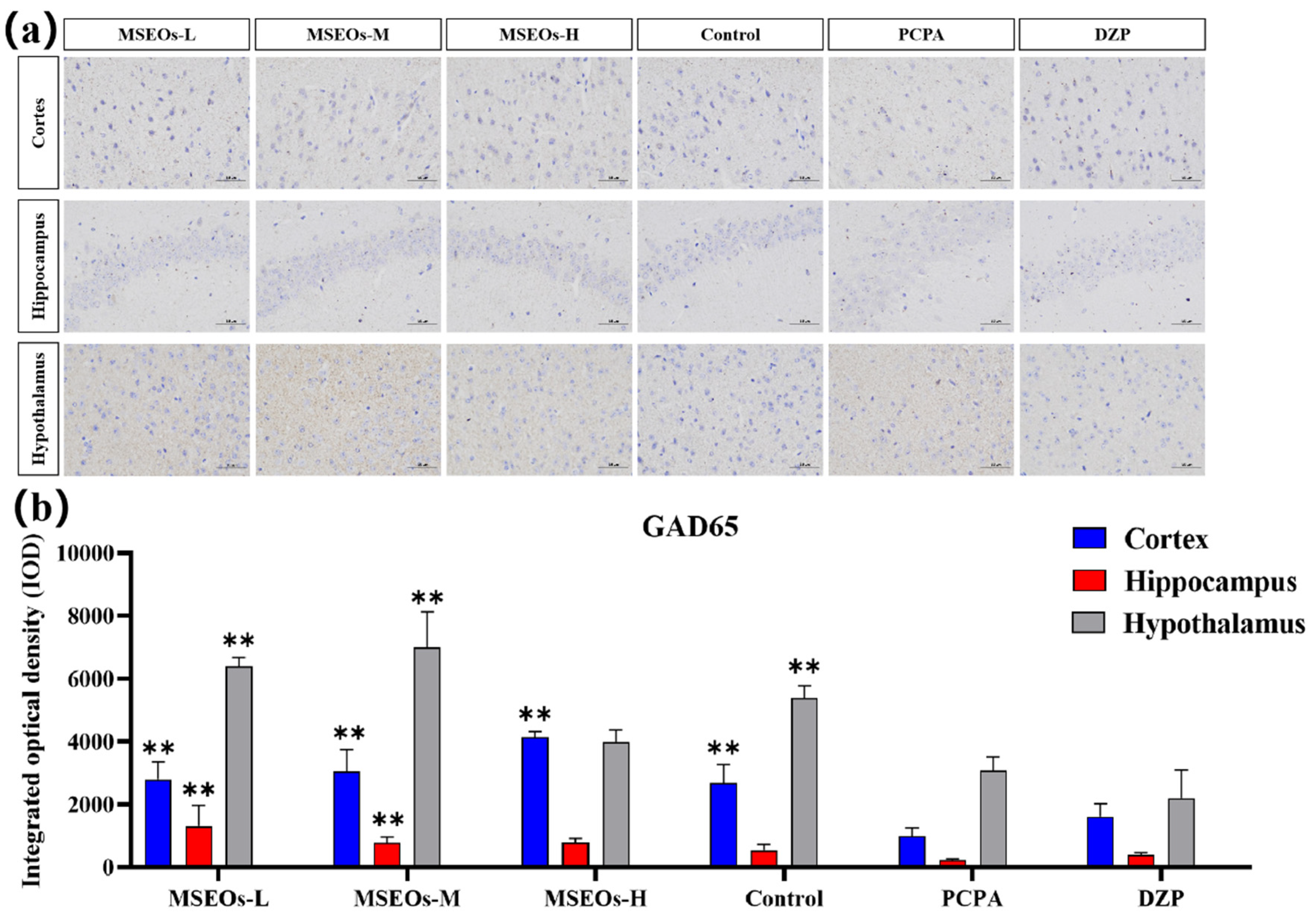

(1) Background: Insomnia is a common sleep disorder that is difficult to cure due to its long duration of influence. Magnolia sieboldii essential oils (MSEOs) have been shown to have antidepressant effects, but there are few studies on treating insomnia. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the therapeutic effects of MSEOs and to elucidate the molecular and neurophysiological mechanisms by which they alleviate insomnia. (2) Methods: The main components of MSEOs extracted by steam distillation were analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). To establish a p-chlorophenylalanine (PCPA) -induced insomnia model in mice, the levels of GAD65, GABAARα1, 5HT-2A, and 5HT-1A were detected by immunohistochemistry and ELISA. The normal neurons in the mouse brain were counted by Nissl staining. The relative mRNA expression levels of related genes in mice were detected by RT- qPCR. (3) Results: A total of 69 components were identified by MSEOs, and the main components were β-elemene (19.94%), (Z)-β-ocimene (14.87%), and Germacrene D (7.05%). Both low and high concentrations of MSEOs can successfully prolong the total sleep time and shorten the sleep latency of mice. GAD65, GABAARα1, 5HT-2A, and 5HT-1A levels still increased to varying degrees after treatment with different concentrations of MSEOs. The results of Nissl staining showed that MSEOs could attenuate PCPA-induced neuronal death. The RT- qPCR results showed that MSEOs enhanced the mRNA expression of 5HT-2A, GABAARα1, and GABAARγ2. (4) Conclusions: MSEOs effectively improved sleep by prolonging total sleep time and shortening latency, potentially through upregulating GAD65, GABAARα1, 5HT-1A, and 5HT-2A levels, protecting neurons, and enhancing mRNA expression of GABAARα1, GABAARγ2, and 5HT-2A, suggesting their potential as a therapeutic for insomnia.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Plant Essential Oil

2.2. Conditions for GC-MS Determination

2.3. PCPA-Induced Insomnia

2.4. Pentobarbital-Induced Sleep Test

2.5. BCA Assay

2.6. ELISA Assay

2.7. Immunohistochemistry Assay

2.8. Nissl Staining Assay

2.9. Immunofluorescence Assays

2.10. RT-qPCR

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Impact of MSEOs on Sleep Duration and Latency to Sleep Onset in Insomniac Mice

3.2. Neuroprotective Effects of MSEOs on PCPA-Induced Insomnia Mice

3.3. Expression of 5HT-2A and 5HT-1A

3.4. Effect of MSEOs on GABAARα1 Levels in Mice with Insomnia

3.5. Impact of MSEOs on GAD65 Protein Levels in the Brain of Mice Subjected to Sleep Deprivation

3.6. RT-qPCR

3.7. Essential Oil Component Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Cui, S.-Y.; Tu, P.-F.; Chen, Y.-M.; Ma, X.-L.; Cui, X.-Y.; Huang, Y.-L.; Ding, H.; Song, J.-Z.; et al. Tenuifolin, a saponin derived from Radix Polygalae, exhibits sleep-enhancing effects in mice. Phytomedicine 2016, 23, 1797–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, Y.; Wang, L.; Lan, J.; Li, H.; Guo, T.; Chen, X.; Dong, C.; Ouyang, Z.; Chen, S.-q. Lilium davidii extract alleviates p-chlorophenylalanine-induced insomnia in rats through modification of the hypothalamic-related neurotransmitters, melatonin and homeostasis of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Pharmaceutical Biology 2020, 58, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La, Y.K.; Choi, Y.H.; Chu, M.K.; Nam, J.M.; Choi, Y.-C.; Kim, W.-J. Gender differences influence over insomnia in Korean population: A cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0227190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, A.R.; Weng, J.; Wallace, D.M.; Petrov, M.R.; Wohlgemuth, W.K.; Sotres-Alvarez, D.; Loredo, J.S.; Reid, K.J.; Zee, P.C.; Mossavar-Rahmani, Y.; et al. Sleep Patterns and Hypertension Using Actigraphy in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Chest 2018, 153, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebert, B.; Wafford, K.A.; Deacon, S. Treating insomnia: Current and investigational pharmacological approaches. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2006, 112, 612–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, K.; Scheid, D.C. Treatment options for insomnia. American Family Physician 2007, 76, 517–526. [Google Scholar]

- Zisapel, N. Drugs for insomnia. Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs 2012, 17, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-W.; Lee, J.; Jung, S.J.; Shin, A.; Lee, Y.J. Use of Sedative-Hypnotics and Mortality: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 2018, 14, 1669–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.-F.; Shen, C.-Y.; Hao, K.-X.; Jiang, J.-G. Flavonoids from Polygoni Multiflori Caulis alleviates p-chlorophenylalanine-induced sleep disorders in mice. Industrial Crops and Products 2024, 218, 119002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yuan, Z.; Zeng, C.; Huang, Y.; Xu, X.; Guo, W.; Zheng, H.; Zhan, R. Role of the Volatile Components in the Anti-insomnia Effect of Jiao-Tai-Wan in PCPA-induced Insomnia Rats. Clinical Complementary Medicine and Pharmacology 2022, 2, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, M.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, H.; Lyu, Y.-S.; Lee, Y.R.; Jeon, B.; Kang, H.W. A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of the clinical effects of aroma inhalation therapy on sleep problems. Medicine 2021, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; He, C.; Shen, M.; Wang, M.; Zhou, J.; Chen, D.; Zhang, T.; Pu, Y. Effects of aqueous extracts and volatile oils prepared from Huaxiang Anshen decoction on p-chlorophenylalanine-induced insomnia mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2024, 319, 117331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, D.-R.; Kim, Y.; Jo, A.; Choi, E.J.; Oh, K.-N.; Kim, J.; Kang, H.; Kim, Y.R.; Choi, C.y. Sedative and hypnotic effects of Vaccinium bracteatum Thunb. through the regulation of serotonegic and GABAA-ergic systems: Involvement of 5-HT1A receptor agonistic activity. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2019, 109, 2218–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, L.-W.; Cheng, S.L.; Liu, C.F. The Effect of Lavender Aromatherapy on Autonomic Nervous System in Midlife Women with Insomnia. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2012, 2012, 740813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.Q.; Xu, H.H.; Hu, P.Y.; Yue, P.F.; Yi, J.F.; Yang, M.; Zheng, Q. Research progress on safety of essential oils from traditional Chinese medicine. Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs 2022, 53, 6626–6635. [Google Scholar]

- Ai, Y.; Tang, M.; Xu, X.; Zhu, S.; Rong, B.; Zheng, X.; Song, N.; He, J.; Zhang, L.; He, T. Volatile Oil from Magnolia sieboldii Improve Neurotransmitter Disturbance and Enhance the Sleep-Promoting Effect in p-Chlorophenylalanine-Induced Sleep-Deprived Mice. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia 2023, 33, 1303–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y.; Tang, M.; Ai, Y.; Song, N.; Ren, L.; Zhang, Z.; Rong, B.; Chen, X.; Xu, X.; Geng, L.J.R.o.N.P. Antidepressant-Like Effect of Aromatherapy with Magnolia sieboldii Essential Oils on Depression Mice. 2023, 17.

- Dong, Y.-J.; Jiang, N.-H.; Zhan, L.-H.; Teng, X.; Fang, X.; Lin, M.-Q.; Xie, Z.-Y.; Luo, R.; Li, L.-Z.; Li, B.; et al. Soporific effect of modified Suanzaoren Decoction on mice models of insomnia by regulating Orexin-A and HPA axis homeostasis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 143, 112141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, L.K.; Schousboe, A.; Waagepetersen, H.S. The glutamate/GABA-glutamine cycle: aspects of transport, neurotransmitter homeostasis and ammonia transfer. Journal of Neurochemistry 2006, 98, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, T.; Wang, Y.; Liang, K.; Zheng, B.; Ma, J.; Li, F.; Liu, C.; Zhu, M.; Song, M. Effects of the Radix Ginseng and Semen Ziziphi Spinosae drug pair on the GLU/GABA-GLN metabolic cycle and the intestinal microflora of insomniac rats based on the brain–gut axis. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIU Xue-ping, Z.M., HAO Yue-wei, HOU Liang, ZHANG Su-ming. Effects of Pioglitazone on cognition function and AGEs-RAGE system in insulin resistance in rats[J]. JOURNAL OF SHANDONG UNIVERSITY (HEALTH SCIENCES) 2008, 46, 954–958.

- Díaz, A.; De Jesús, L.; Mendieta, L.; Calvillo, M.; Espinosa, B.; Zenteno, E.; Guevara, J.; Limón, I.D. The amyloid-β25–35 injection into the CA1 region of the neonatal rat hippocampus impairs the long-term memory because of an increase of nitric oxide. Neuroscience Letters 2010, 468, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Yin, X. Effects of Suanzaoren decoction on learning memory ability and neurotransmitter content in the brain of rats with senile insomnia model. Zhong Guo Yao Fang 2016, 27, 3085–3087. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, X.; Yang, H.; Au, D.W.-Y.; Lai, S.P.-H.; Lin, Y.; Cho, W.C.-S. Membrane Repairing Capability of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells Is Regulated by Drug Resistance and Epithelial-Mesenchymal-Transition. 2022, 12, 428.

- Forouzanfar, F.; Gholami, J.; Foroughnia, M.; Payvar, B.; Nemati, S.; Khodadadegan, M.A.; Saheb, M.; Hajali, V. The beneficial effects of green tea on sleep deprivation-induced cognitive dficits in rats: the involvement of hippocampal antioxidant defense. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagata, T.; Kahn, M.C.; Prius-Mengual, J.; Meijer, E.; Šabanović, M.; Guillaumin, M.C.C.; van der Vinne, V.; Huang, Y.G.; McKillop, L.E.; Jagannath, A.; et al. The hypothalamic link between arousal and sleep homeostasis in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, P.; Kaur, G. Acute Sleep Deprivation-Induced Anxiety and Disruption of Hypothalamic Cell Survival and Plasticity: A Mechanistic Study of Protection by Butanol Extract of Tinospora cordifolia. Neurochemical research 2022, 47, 1692–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, F.; Edison, P. Neuroinflammation and microglial activation in Alzheimer disease: where do we go from here? Nature Reviews Neurology 2021, 17, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.W.; Sirlin, E.A.; Benoit, A.M.; Hoffman, J.M.; Darnall, R.A. Activation of 5-HT1A receptors in medullary raphé disrupts sleep and decreases shivering during cooling in the conscious piglet. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2008, 294, R884–R894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.J.; Baghdoyan, H.A.; Lydic, R. Neuropharmacology of Sleep and Wakefulness. Sleep Medicine Clinics 2010, 5, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celada, P.; Puig, M.V.; Amargós-Bosch, M.; Adell, A.; Artigas, F. The therapeutic role of 5-HT<sub>1A</sub> and 5-HT<sub>2A</sub> receptors in depression. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience 2004, 29, 252. [Google Scholar]

- Elahee, S.F.; Mao, H.-j.; Zhao, L.; Shen, X.-y. Meridian system and mechanism of acupuncture action: A scientific evaluation. World Journal of Acupuncture - Moxibustion 2020, 30, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre, T.A.; Zurowski, M.; Fox, S.H. 5-Hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor antagonists as potential treatment for psychiatric disorders. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 2013, 22, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, J.M.; Jantos, H. The Role of 5-HT2A/2C Receptors in Sleep and Waking. In 5-HT2C Receptors in the Pathophysiology of CNS Disease; Di Giovanni, G., Esposito, E., Di Matteo, V., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2011; pp. 393–412. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Luo, L.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, J. Effects of Evodia rutaecarpa Acupoint Sticking Therapy on Rats with Insomnia Induced by Para-Chlorophenylalanine in 5-HT1Aand 5-HT2A Gene Expressions. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology 2022, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, X.; Mao, X.; Liu, A.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Bi, K.; Jia, Y. Pharmacological evaluation of sedative and hypnotic effects of schizandrin through the modification of pentobarbital-induced sleep behaviors in mice. European Journal of Pharmacology 2014, 744, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordukalo-Niksic, T.; Mokrovic, G.; Stefulj, J.; Zivin, M.; Jernej, B.; Cicin-Sain, L. 5HT-1A receptors and anxiety-like behaviours: Studies in rats with constitutionally upregulated/downregulated serotonin transporter. Behavioural Brain Research 2010, 213, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Servando, J.; Matus, M.; Cortijo, X.; Gasca, E.; Violeta, P.; P.V, S.; Pérez-Palacios, A.; Ramos-Morales, F. Receptor GABA A: implicaciones farmacológicas a nivel central. Archivos de Neurociencias 2011, 16, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.-M.; Shimizu, M.; Lee, C.J.; Han, D.-S.; Jung, C.-K.; Jo, J.-H.; Kim, Y.-M. Hypnotic effects and binding studies for GABAA and 5-HT2C receptors of traditional medicinal plants used in Asia for insomnia. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2010, 132, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, U.; Knoflach, F. Beyond classical benzodiazepines: novel therapeutic potential of GABAA receptor subtypes. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2011, 10, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Hu, P.; Huang, X.; Yang, M.; Ren, G.; Li, J.; Du, Q.; Liu, S.; Zhang, K.; et al. Sedative and hypnotic effects of Perilla frutescens essential oil through GABAergic system pathway. J Ethnopharmacol 2021, 279, 113627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Ma, P.Y.; Li, H.L.; Xiao, B.; Cai, W.F.; Xing, X.F. Nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) and NMN-rich product supplementation alleviate p-chlorophenylalanine-induced sleep disorders. JOURNAL OF FUNCTIONAL FOODS 2022, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, F.C.; Draguhn, A. GABA Metabolism and Transport: Effects on Synaptic Efficacy. Neural Plasticity 2012, 2012, 805830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Yan, Y.; Peng, M.; Gao, M.; Zhou, L.; Chen, F.; Yang, L.; Li, L.; Yang, X. Therapeutic potential of folium extract in insomnia treatment: a comprehensive evaluation of behavioral and neurochemical effects in a PCPA-induced mouse model. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2024, n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tochitani, S.; Kondo, S. Immunoreactivity for GABA, GAD65, GAD67 and Bestrophin-1 in the Meninges and the Choroid Plexus: Implications for Non-Neuronal Sources for GABA in the Developing Mouse Brain. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e56901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.E.; McKenna, J.T.; Winston, S.; Basheer, R.; Yanagawa, Y.; Thakkar, M.M.; McCarley, R.W. Characterization of GABAergic neurons in rapid-eye-movement sleep controlling regions of the brainstem reticular formation in GAD67–green fluorescent protein knock-in mice. European Journal of Neuroscience 2008, 27, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obata, K.; Hirono, M.; Kume, N.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Itohara, S.; Yanagawa, Y. GABA and synaptic inhibition of mouse cerebellum lacking glutamate decarboxylase 67. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2008, 370, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, G.F.; Martin, D.L.; Martin, S.B.; Manor, D.; Sibson, N.R.; Patel, A.; Rothman, D.L.; Behar, K.L. Decrease in GABA synthesis rate in rat cortex following GABA-transaminase inhibition correlates with the decrease in GAD67 protein. Brain Research 2001, 914, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.Y.; Wan, L.; Zhu, J.J.; Jiang, J.G. Targets and underlying mechanisms related to the sedative and hypnotic activities of saponin extracts from semen Ziziphus jujube. Food & function 2020, 11, 3895–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Tian, A.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, H.; Chen, L. Amelioration of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis by β-elemene Treatment is Associated with Th17 and Treg Cell Balance. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience 2011, 44, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ma, L.; Liu, F.; Yao, L.; Wang, W.; Yang, S.; Han, T. Lavender essential oil fractions alleviate sleep disorders induced by the combination of anxiety and caffeine in mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2023, 302, 115868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiya, M.; Takeuchi, T.; Harada, E. Lemon oil vapor causes an anti-stress effect via modulating the 5-HT and DA activities in mice. Behavioural Brain Research 2006, 172, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchbauer, G.; Jirovetz, L.; Jäger, W.; Plank, C.; Dietrich, H. Fragrance Compounds and Essential Oils with Sedative Effects upon Inhalation. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 1993, 82, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, H.; Azimullah, S.; Abul Khair, S.B.; Ojha, S.; Haque, M.E. Neuroprotective effect of nerolidol against neuroinflammation and oxidative stress induced by rotenone. BMC Neuroscience 2016, 17, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonsêca, D.V.; Salgado, P.R.R.; de Carvalho, F.L.; Salvadori, M.G.S.S.; Penha, A.R.S.; Leite, F.C.; Borges, C.J.S.; Piuvezam, M.R.; Pordeus, L.C.d.M.; Sousa, D.P.; et al. Nerolidol exhibits antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activity: involvement of the GABAergic system and proinflammatory cytokines. Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology 2016, 30, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, L. Acyclic sesquiterpenes nerolidol and farnesol: mechanistic insights into their neuroprotective potential. Pharmacological Reports 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legault, J.; Pichette, A.J.J.o.P. Potentiating effect of β-caryophyllene on anticancer activity of α-humulene, isocaryophyllene and paclitaxel. Pharmacology 2007, 59, 1643–1647. [Google Scholar]

- Fidyt, K.; Fiedorowicz, A.; Strządała, L.; Szumny, A.J.C.m. β-caryophyllene and β-caryophyllene oxide—natural compounds of anticancer and analgesic properties. 2016, 5, 3007-3017.

- Adams, R.P.; González Elizondo, M.S.; Elizondo, M.G.; Slinkman, E. DNA fingerprinting and terpenoid analysis of Juniperus blancoi var. huehuentensis (Cupressaceae), a new subalpine variety from Durango, Mexico. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 2006, 34, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero, M.E.; Fredrickson, E.L.; Estell, R.E.; Morrison, A.A.; Richman, D.B. Volatile Composition of Gutierrezia sarothrae (Broom Snakeweed) as Determined by Steam Distillation and Solid Phase Microextraction. Journal of Essential Oil Research 2006, 18, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emile, M. Gaydou, Robert Randriamiharisoa, and Jean-Pierre Bianchini;Composition of the Essential Oil of Ylang-Ylang (Cananga odorata Hook Fil. et Thomson forma genuina) from Madagascar. J. Agrie. Food Chem. 1986, 34, 481–487. [Google Scholar]

- Sabulal, B.; Dan, M.; J, A.J.; Kurup, R.; Chandrika, S.P.; George, V. Phenylbutanoid-rich rhizome oil of Zingiber neesanum from Western Ghats, southern India. Flavour and Fragrance Journal 2007, 22, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichini, F.; Tundis, R.; Bonesi, M.; de Cindio, B.; Loizzo, M.R.; Conforti, F.; Statti, G.A.; Menabeni, R.; Bettini, R.; Menichini, F. Chemical composition and bioactivity of Citrus medica L. cv. Diamante essential oil obtained by hydrodistillation, cold-pressing and supercritical carbon dioxide extraction. Natural Product Research 2011, 25, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro1, P.F.; Queiroz, V.T.d.; Rondelli, V.M.; Costa3, A.V.; Marcelino, T.d.P.; Pratissoli, D. Insecticidal activity of citronella grass essential oil on Frankliniella schultzei and Myzus persicae. Agricultural Sciences 2013, 37(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.R. Sardashti, J. Valizadeh and Y. Adhami. Variation in the Essential Oil Composition of Perovskia Abrotonoides of Different Growth Stage in Baluchestan. World Applied Sciences Journal 2012, 19, 1259–1262.

- Bendiabdellah, A.; El Amine Dib, M.; Djabou, N.; Allali, H.; Tabti, B.; Muselli, A.; Costa, J. Biological activities and volatile constituents of Daucus muricatus L. from Algeria. Chemistry Central Journal 2012, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.S.; Hao, J.F.; Zhou, H.Y.; Zhu, L.X.; Wang, J.H.; Song, F.Q. Pharmacological studies on the sedative-hypnotic effect of Semen Ziziphi spinosae (Suanzaoren) and Radix et Rhizoma Salviae miltiorrhizae (Danshen) extracts and the synergistic effect of their combinations. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Cai, X.; Zhao, J.; Yan, Z. Serotonin Receptors Modulate GABA<sub>A</sub> Receptor Channels through Activation of Anchored Protein Kinase C in Prefrontal Cortical Neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience 2001, 21, 6502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowski, D.; Rigo, M.; Duc, D.; Hoyer, D.; Staufenbiel, M. Localization of the 5-hydroxytryptamine2C receptor protein in human and rat brain using specific antisera. Neuropharmacology 1995, 34, 1635–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qin, X.; Gui, Z.; Chu, W. The effect of Bailemian on neurotransmitters and gut microbiota in p-chlorophenylalanine induced insomnia mice. Microbial Pathogenesis 2020, 148, 104474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, G.; Happe, S.; Evers, S.; Hermann, W.; Jansen, S.; Kallweit, U.; Muntean, M.-L.; Pohlau, D.; Riemann, D.; Saletu, M.; et al. Insomnia in neurological diseases. Neurological research and practice 2021, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.B.; Zhou, Q.; Yan, J.X.; Luo, L.S.; Zhang, J.L. Enzymolysis peptides from Mauremys mutica plastron improve the disorder of neurotransmitter system and facilitate sleep-promoting in the PCPA-induced insomnia mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2021, 274, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.Y.; Li, N.; Jing, S.; Wang, C.M.; Sun, J.H.; Li, H.; Liu, J.L.; Chen, J.G. Schisandrin B exerts hypnotic effects in PCPA-treated rats by increasing hypothalamic 5-HT and gamma-aminobutyric acid levels. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesmann, C. GABA mechanisms and sleep. Neuroscience 2002, 111, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Latin name | Local name | Voucher number | Collection time | Storage location |

| Magnolia sieboldii | Tiannvmulan | 2020-112A | 2020.09 | Institute of Natural Medicine & Green Chemistry, School of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Guangdong University of Technology |

| Genes | Forward (5′-3′) | Reverse (3′-5′) |

| 5HT-1A | CCAACTATCTCATCGGCTCCTT | CTGACCCAGAGTCCACTTGTTG |

| 5HT-2A | TATGCTGCTGGGTTTCCTTGT | GTTGAAGCGGCTATGGTGAAT |

| GABAARα1 | ATGACAGTGCTCCGGCTAAAC | AGTGCATTGGGCATTCAGCT |

| GABAARγ2 | GCAGTTCTGTTGAAGTGGGTGA | GCAGGGAATGTAAGTCTGGATGG |

| No | Compounds1 | RI2 | Exp RI3 | Ref 4 | Relative content (%) |

| Magnolia sieboldii | |||||

| 1 | β-pinene | 861 | 980 | A | 0.13 |

| 2 | α-terpinene | 877 | 1018 | C | 0.87 |

| 3 | (Z)-β-ocimene | 895 | 1041 | B | 14.87 |

| 4 | γ-terpinene | 941 | 1062 | C | 1.72 |

| 5 | 2-Carene | 959 | 1002 | D | 0.61 |

| 6 | fenchone | 966 | - | - | 0.17 |

| 7 | Linalool | 971 | 1096 | D | 0.8 |

| 8 | 2,6-Dimethyl-2,4,6-octatriene | 984 | 1131 | E | 2.91 |

| 9 | (±)-Camphor | 1025 | - | - | 0.12 |

| 10 | Terpinine-4-ol | 1051 | 1177 | D | 2.99 |

| 11 | 1-(3-methylenecyclopentyl)-Ethanone | 1110 | - | - | 0.1 |

| 12 | Citronellol | 1132 | 1223 | D | 0.28 |

| 13 | CIS-3-NONEN-1-OL | 1171 | 1157 | D | 0.2 |

| 14 | Decan-1-ol | 1184 | 1266 | D | 0.16 |

| 15 | O-Benzyllinalool | 1205 | - | - | 0.11 |

| 16 | delta-elemene | 1246 | 1338 | D | 0.25 |

| 17 | α-Terpinyl acetate | 1262 | 1349 | D | 0.1 |

| 18 | dl-Citronellol acetate | 1264 | 1352 | D | 0.5 |

| 19 | α-Copaene | 1278 | 1376 | D | 0.3 |

| 20 | β-elemene | 1293 | 1390 | D | 19.94 |

| 21 | isocaryophyllene | 1307 | 1408 | D | 3.63 |

| 22 | β-cubebene | 1313 | 1388 | D | 0.22 |

| 23 | α-guaiene | 1333 | - | - | 0.76 |

| 24 | alloaromadendrene | 1341 | 1460 | D | 0.13 |

| 25 | α-caryophyllene | 1345 | 1454 | D | 1.84 |

| 26 | (E)-β-Farnesene | 1349 | 1456 | D | 1.43 |

| 27 | valencene | 1353 | - | - | 0.22 |

| 28 | trans-Caryophyllene | 1357 | 1419 | D | 0.1 |

| 29 | β-chamigrene | 1362 | 1477 | D | 0.57 |

| 30 | Germacrene D | 1366 | 1481 | D | 7.05 |

| 31 | α-Curcumene | 1372 | 1483 | F | 0.76 |

| 32 | α-bergamotene | 1380 | 1403 | F | 3.49 |

| 33 | α-muurolene | 1384 | 1500 | H | 0.69 |

| 34 | β-Bisabolene | 1390 | 1505 | D | 1.15 |

| 35 | Muurolene | 1395 | 1479 | D | 0.45 |

| 36 | β-cadinene | 1398 | 1513 | H | 2.84 |

| 37 | α-selinene | 1429 | 1498 | D | 0.58 |

| 38 | cis-(+)Nerolidol | 1434 | 1525 | J | 4.51 |

| 39 | (-)-β-Bourbonene | 1443 | 1388 | D | 0.83 |

| 40 | Caryophyllene oxide | 1447 | 1583 | D | 0.39 |

| 41 | α-patchoulene | 1454 | 1456 | D | 0.5 |

| 42 | 4,7,7-trimethyl-3-phenylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-3-ol | 1459 | - | - | 0.1 |

| 43 | juniper camphor | 1474 | 1700 | D | 0.32 |

| 44 | α-bulnesene | 1482 | 1509 | D | 1.3 |

| 45 | α-muurolol | 1487 | 1646 | D | 0.17 |

| 46 | T-cadinol | 1490 | 1663 | I | 0.55 |

| 47 | (+)-Viridiflorol | 1492 | 1592 | D | 0.83 |

| 48 | δ-Cardinol | 1495 | 1644 | D | 0.21 |

| 49 | α-Cadinol | 1495 | 1653 | C | 2.07 |

| 50 | Eicosapentaenoic Acid methyl ester | 1497 | - | - | 2.26 |

| 51 | (-)-spathulenol | 1505 | - | - | 0.29 |

| 52 | Spathulenol | 1512 | 1578 | E | 0.43 |

| 53 | Isovellerdiol | 1515 | - | - | 0.11 |

| 54 | Andrographolide | 1536 | - | - | 0.4 |

| 55 | cembrene | 1543 | 1938 | D | 0.2 |

| 56 | 1-Heptatriacotanol | 1547 | - | - | 0.43 |

| 57 | dl-Perillaldehyde | 1550 | 1271 | D | 0.1 |

| 58 | p-Menth-8-en-2-ol acetate | 1557 | - | - | 0.1 |

| 59 | artemisia triene | 1571 | - | - | 0.1 |

| 60 | 9,10-Dibromo-(+)-camphor | 1581 | - | - | 0.13 |

| 61 | safranal | 1599 | 1196 | D | 2.71 |

| 62 | α-santalol | 1616 | 1675 | E | 0.95 |

| 63 | Kaur-16-en-18-yl acetate | 1647 | - | - | 0.39 |

| 64 | 1,5,5-trimethyl-6-methylidenecyclohexene | 1683 | - | - | 0.63 |

| 65 | 3,3,6,6-Tetramethyl-1,4-cyclohexadiene | 1700 | - | - | 0.67 |

| 66 | cyclopentadeca-1,8-diyne | 1711 | - | - | 0.5 |

| 67 | Shizukanolide | 1717 | - | - | 0.11 |

| 68 | Oxacyclotetradeca-4-11-diyne | 1730 | - | - | 0.1 |

| 69 | (1R,2R)-2-methyl-1-(4-methylphenyl)but-3-en-1-ol | 1737 | - | - | 0.28 |

| Total identified/% | 95.71 | ||||

| Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons/% | 60.47 | ||||

| Oxygenated sesquiterpenes/% | 10.94 | ||||

| Total monoterpenoids/% | 29.36 | ||||

| Oxygenated monoterpenes/% | 6.85 | ||||

| Others/% | 5.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).