1. Introduction

Fatigue is defined as the inability of an organic physiological process to maintain its function at a specific level and/or to maintain a predetermined intensity of exercise [

1]. Fatigue emerges as a predominant symptom of sub-health, representing a pre-disease condition and a harbinger of potential pathologies. It triggers a cascade of physiological responses including sleep deprivation, endocrine imbalances, metabolic dysfunctions, and immune impairments. The modern lifestyle, characterized by fast-paced living, stress, unhealthy dietary habits, irregular routines, sleep deprivation, sedentary behavior, and persistent negative emotions, is exacerbating the prevalence of sub-health conditions. Chronic fatigue can eventually lead to serious health problems such as accelerated aging, anxiety, depression, and neurodegenerative diseases such as cancer and Parkinson’s, significantly reducing an individual’s quality of life and productivity at work [

2].Research shows that 12% of middle school students in China suffer from chronic fatigue [

3]. The current pharmacological solutions, such as cerebral cortex stimulants, can offer temporary relief of fatigue, while their potential for adverse effects like convulsions, mental disturbances, and dependency restricts their utility. Therefore, it is urgent to seek the more safe and effective anti-fatigue compounds and elucidate their mechanisms of action for developing the anti-fatigue nutritional health products to meet the nutritional needs of modern people.

Food and drug homologous substances have the characteristics of both medicine and food, which is a special resource in China and has great potential for exploitation. With the increase of health awareness and the pursuit of health, food with dual medicinal and nutritional value caters to the preferences of modern people.

Areca catechu L., is an evergreen tree of Areca genus of the palm family (Palmaceae) and one of the cash crops in the south tropical and subtropical areas of China. The dried, mature seeds of it are called areca nut. The fresh fruits and the dried processed products are its main food routes. In addition,

Areca catechu L. own a wide array of bioactive actions, such as anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antioxidant [

4,

5], anti-aging, antidepressant, antihypoxic [

6], antithrombotic [

7], as well as aiding in blood sugar reduction [

8,

9], vascular protection [

10] and gastrointestinal enhancement [

11,

12], which promotes it esteemed as the foremost among the "four southern medicines" of China. As one of the important active substances in areca nut, alkaloids exhibit the potent biological actions, particularly on the nervous and digestive systems [

13,

14,

15].The primary alkaloids, including arecoline and its derivatives, constitute approximately 0.3% to 0.7% of the total content[

16,

17].It is reported that the extract of

Areca catechu L can enhance the cognitive function, elevate the antioxidant capacity of brain tissue and reduce the signs of tissue aging in mice, showing anti-aging effects [

18]. Furthermore, our previous findings showed that arecoline has the neuroprotective activities both in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced BV2 inflammatory response in mouse microglia [

19] and H

2O

2-induced oxidative stress damaged model in SH-SY5Y cells, and elucidated its mechanisms related to the antioxidation and anti-apoptosis [

20]. However, the anti-fatigue effect of arecoline has not yet been reported. In order to further explore the biological activity of arecoline and elucidate its mechanisms, the present study was conducted to determine whether arecoline could improve the fatigue induced by sleep deprivation through modulating the antioxidant system and attenuating the inflammatory response.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Arecoline (63-75-2, No.:A14660) was supplied by Shanghai Jizhi Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Rhodiola Rosea capsules is provided by Shanxi Jiahe Phytochemistry Co., Ltd (Xian, Shanxi, China). Commercial sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), dopamine (DA), norepinephrine (NE), acetylcholine (Ach), gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6) were obtained from Jiancheng Biological Technology Co., Ltd (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). The commercial kits for serum testosterone (TTS), corticosterone (CTC), lactic acid (LD), triglyceride (TG), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), creatine kinase (CK), immunoglobulin G (IgG), liver glycogen (LG), muscle glycogen (MG), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), malondialdehyde (MDA), catalase (CAT) were purchased from Jianglai Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Antibodies targeting nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2), Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1), heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), sequestosome-1 (p62), and NADPH quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) were supplied by Cell Signaling Technology(Boston,USA).

2.2. Ethical Statement

The study was performed in compliance with the National Institutes of Health and institutional guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and under the approval and supervision of the Animal Ethics Committee at Institute of Food Science and Technology, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Approval Number: SYXK-2023100312).

2.3. Animals and Experimental Design

Seventy-two male C57BL/6 mice, weighing between 18.0 and 22.0g, were acquired from Beijing Weitonglihua Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd., holding an experimental animal production license (SCXK (Guangdong) 2019-0063) and an experimental animal qualification certificate (No.44829700011576). Before tests, the mice were acclimated for 7 days in the animal room (12 h light/dark cycle; 23 ± 2 ℃ ambient temperature; 55 ± 10% relative humidity) and allowed free access to chow and water. Based on body weight, the mice were randomly segregated into six groups(n=12/group): (1) Control (control group not subjected to any stress, distilled water); (2) Model (Sleep deprivation (SD) model group subjected to the SD procedure, distilled water); (3) Rhodiola (the positive group subjected to the SD procedure, Rhodiola Rosea capsules at 2.5 mg/kg); (4) Arecoline-L (the group subjected to the SD procedure, 10 mg/kg Arecoline); (5) Arecoline-M (the group subjected to the SD procedure, 20 mg/kg Arecoline); (6) Arecoline-H (the group subjected to the SD procedure, 40 mg/kg Arecoline). The mice were administrated with the corresponding solutions 1 h before the beginning of the daily SD procedure and behavioral tests. All drugs were dissolved in distilled water and given by gastric gavage at a volume of 20 mL/kg of body weight. Following 28 days of SD procedure and the continuous treatment, the forelimb grip strength test, rotary latency test, and exhaustive swimming tests were conducted to assess the anti-fatigue effects of arecoline. After the behavioral tests, the mice were sacrificed by decapitation.

2.4. SD Procedure

The SD procedure was performed as previously described [

21]. In Brief, the mice except the control group were acclimated to the automated sleep interruption apparatus (SIA) for 3 hr (from 8:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. daily) that lasted for 3 days before the SD procedure, meanwhile the mice in the control group were housed in a static SIA copy apparatus. Then, SD period for 28 days began during which the SD mice stayed inside the SIA for 24 hr/day, while the control mice were still housed in the static SIA copy apparatus. At the same time, the mice were daily administrated with different doses of arecoline or Rhodiola by oral gavage, whereas the control and SD model groups received the corresponding volume of the vehicle solution.

2.5. Behavioral Tests

2.5.1. Forelimb Grip Strength Test

On the 29th day, the forelimb grip strength of the mice was measured using a low-force testing system (Model-RX-5). In brief, the procedure involved having the mice grip the available grids in the instrument with their front paws. Subsequently, their tails were elevated and gently pulled backward, enabling the maximum force exerted by the mice to be automatically recorded by the system. The forelimb grip strength for each mouse was determined by calculating the average of three consecutive measurements, ensuring accuracy and reliability of the data collected. This method provided a quantitative assessment of the muscular strength and fatigue resistance in the mice following the experimental interventions.

2.5.2. Rotary Latency Test

The Rotarod test was conducted to evaluate the exercise endurance and motor coordination in mice. In this test, mice were positioned on a cylindrical rod that rotates at a gradually increasing speed. The procedure involved closely observing the mice’s performance as the rotation speed escalates, meticulously noting endurance time and the specific speeds at which the mice can no longer maintain their balance and subsequently fall off the rod. The commencement of the test sees the rod begin to rotate, with the experimenter tasked with monitoring the mice’s behavior on this apparatus. The precise moment a mouse falls or fails to maintain balance, indicating a loss of motor coordination or endurance, is recorded as the drop time.To ensure comprehensive and reliable assessment, the test is repeated multiple times, with each trial lasting for several minutes. This repetitive testing approach allows for the determination of key parameters such as endurance and overall exercise capacity of the mice, providing valuable insights into their physical performance and motor skills post-experimental interventions.

2.5.3. Exhaustive Swimming Test

The swimming endurance of the mice was evaluated using an adjustable current swimming pool, with some modifications to the standard protocol. Briefly, 30 minutes following the final administration via gavage, each mouse was equipped with a lead sheath, equivalent to 5% of its body weight, affixed at the root of its tail. Subsequently, the mice were placed individually into an acrylic plastic pool, which was maintained at a water temperature of 25°C and a depth of 35 cm. The exhaustive swimming time, serving as the primary measure of endurance, was meticulously recorded from the moment the mouse began swimming until it could no longer resurface within a 10-second interval. This assessment method effectively quantifies the physical stamina and fatigue resistance of the mice, offering insights into their endurance capabilities under induced stress conditions.

2.6. Sample Collection

Immediately following the conclusion of the final exhaustive swim test, each mouse was euthanized, and blood samples were extracted from the eyeball. These samples were then centrifuged at 4℃ and 3500 rpm for 10 min to separate the serum. Key organs, including the liver, hippocampus, and gastrocnemius muscle, were excised. The liver and muscle tissues were immersed in 10% (v/v) formalin for preservation or stored at −80°C for further analysis.

2.7. Biochemical Parameter Assays

The activities of serum testosterone (TTS), corticosterone (CTC), lactic acid (LD), triglyceride (TG), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), creatine kinase (CK), immunoglobulin G (IgG), liver glycogen (LG), muscle glycogen (MG) and the levels of superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), malondialdehyde (MDA), catalase (CAT) both in the muscle and hippocampus were determined using commercially assay kits (Jianglai Biological Technology Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

The hippocampus sample was collected to measure the levels of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), dopamine (DA), norepinephrine (NE), acetylcholine (Ach), gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6) using commercial ELISA kits (Jiancheng Biological Technology Co., Ltd, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) based on the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.8. Western Blot Analysis

Protein extraction from the gastrocnemius muscle was performed using lysis buffer, supplemented with a phosphatase inhibitor, to ensure comprehensive protein recovery while preventing dephosphorylation. Following lysis, the mixture was centrifuged at 4°C for 4 minutes at 13,000 rpm, enabling the collection of the supernatant, which contains the protein content.For protein analysis, equal quantities of the protein samples (30 μg) were subjected to electrophoresis on a 12% SDS-PAGE to achieve separation based on molecular weight. Subsequently, the separated proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes, a step crucial for subsequent immunoblotting. To prevent non-specific binding, the membranes were incubated with 5% (w/v) skimmed milk at room temperature, serving as a blocking agent.The membranes were then incubated with specific primary antibodies designed to bind to the proteins of interest overnight at 4°C, ensuring optimal binding affinity and specificity. Following this incubation, the membranes were washed three times with T-TBS to remove unbound antibodies and then incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 hour at 25°C. These secondary antibodies are conjugated to an enzyme that produces a detectable signal upon substrate addition, allowing for visualization of the protein bands. Development of the blots was conducted using a Gel Image Analysis System, which facilitates the visualization and quantification of the protein bands. For quantitative analysis, the relative protein expression levels were normalized to GAPDH, a housekeeping protein, using ImageJ software. This normalization is critical for accounting for variations in sample loading and transfer efficiency, providing a reliable measure of the protein levels of interest in the context of the study’s experimental conditions.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

The experimental data were analyzed using SPSS software version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and expressed as mean ± SEM. One-way analysis of variance followed by multiple post hoc comparisons using the least significant difference test was carried out to analyze the data. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant for all tests.

4. Discussion

Sleep is a vital physiological process for humans and a protective mechanism for maintaining autonomic nervous system and immune system homeostasis [

22]. Shorter sleep times can lead to fatigue, increased mood swings, and affect learning and memory. Studies have shown that lack of sleep has significant effects on cardiovascular, endocrine, immune and nervous systems [

23,

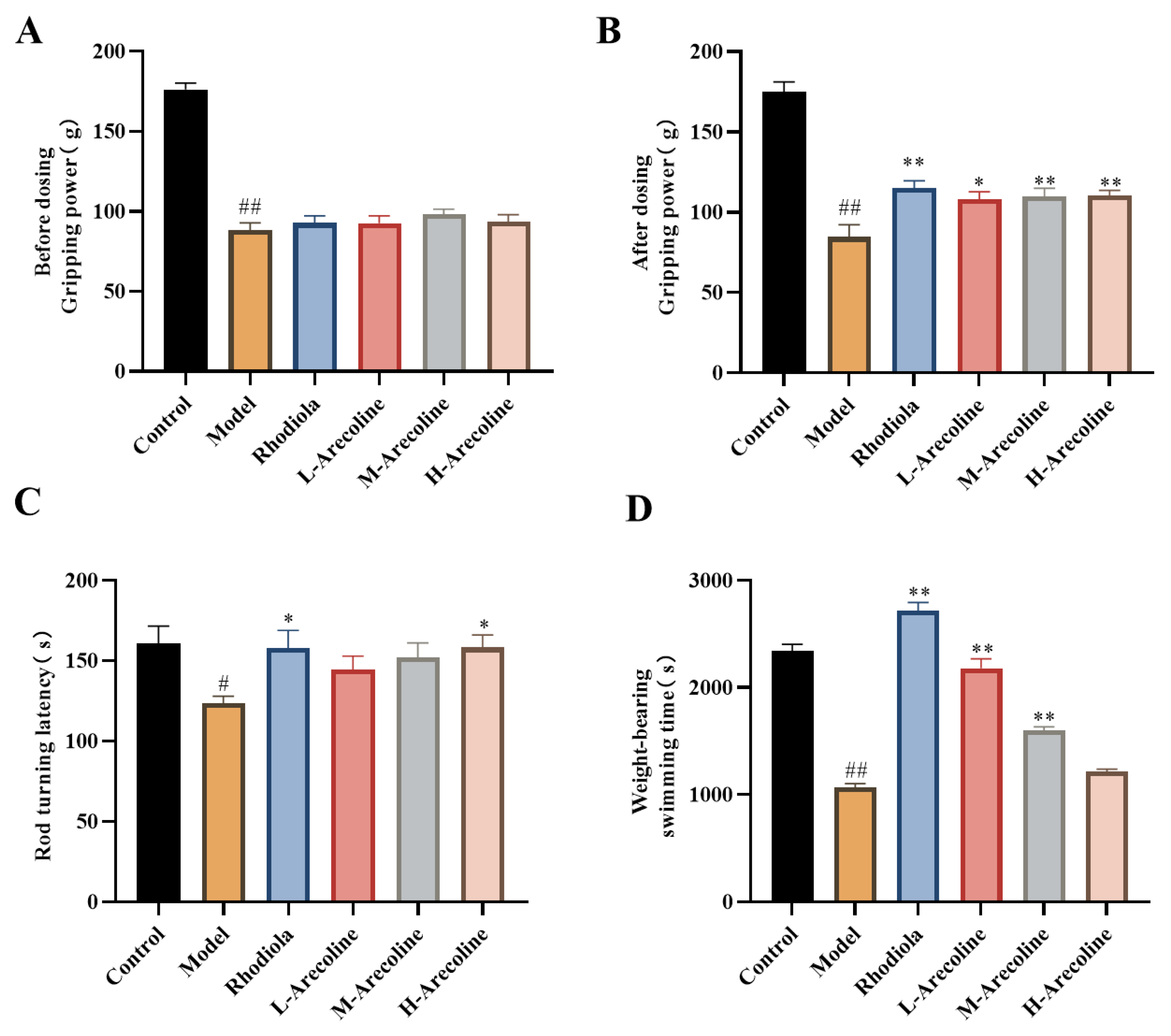

24].Fatigue is a long-term or temporary state of physical or mental weakness and exhaustion, often accompanied by a lack of energy, motivation, and focus.The SD-induced fatigue model can mimic a state of fatigue induced by sleep deprivation and is used to screen the the candidate anti-fatigue active substances. Grip test, rod spinning test and weight exhaustion swimming tests were conducted in the current study, which are the classic behavioral paradigms for evaluating the fatigue-like behaviors and body strength of experimental animals [

25,

26]. The results of this study showed that after 14 days of chronic sleep deprivation, the grasping power, rod turning time and weight-bearing swimming time of mice were significantly reduced, indicating that the fatigue mouse model was successfully established. Meanwhile, administrations with arecoline (10, 20 and 40 mg/kg) significantly improved these behavioral changes in SD-induced mouse fatigue, exerting the remarkable anti-fatigue action.

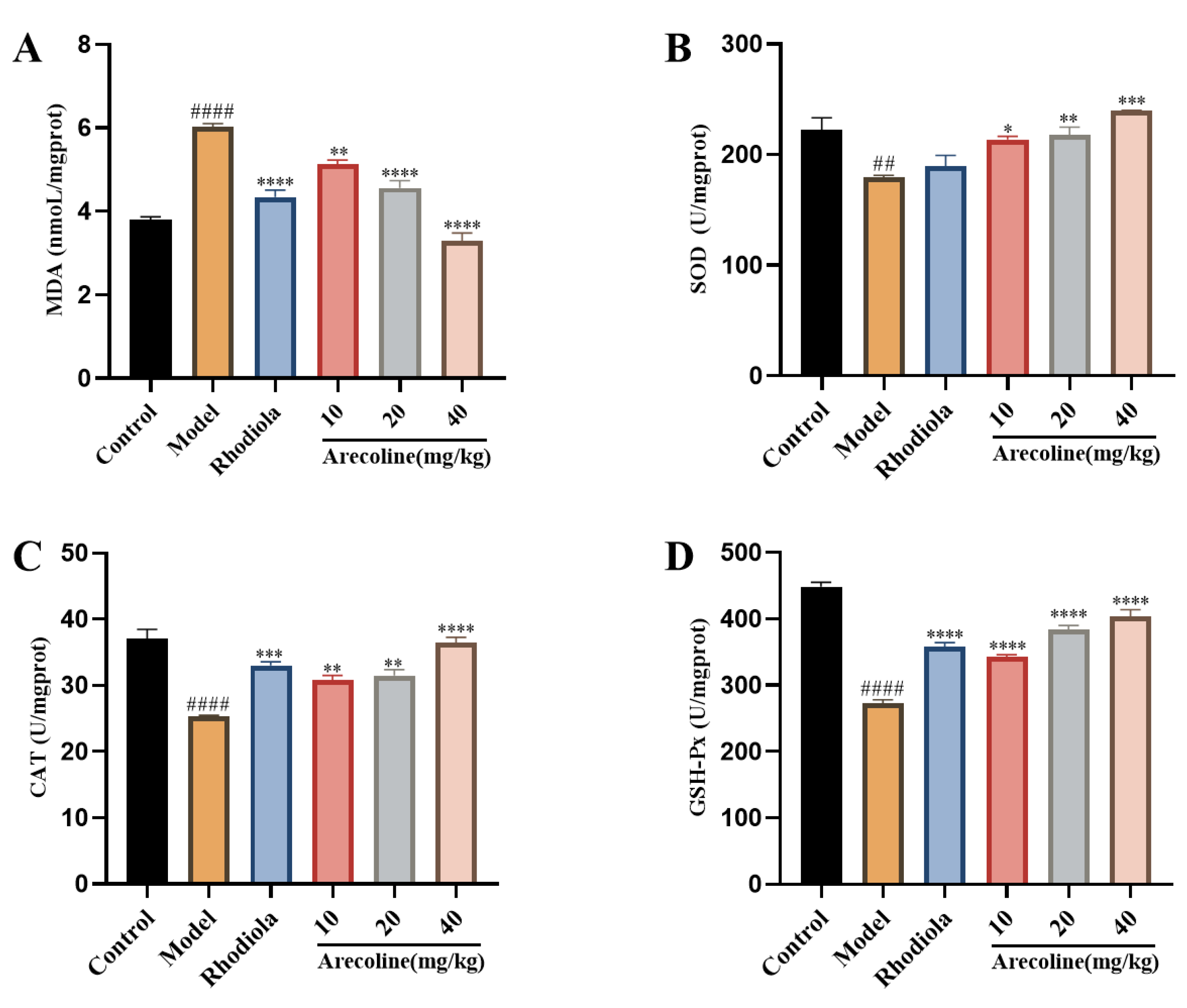

Oxidative stress is a state in which the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the body increases dramatically. Under normal circumstances, the ROS production and antioxidant systems in the body are in a state of dynamic balance.However, excessive ROS produced by strenuous exercise can lead to an imbalance in the oxidative stress response, resulting in lipid peroxidation of membrane structures and the formation of lipid peroxidation product MDA, which changes the fluidity and permeability of cell membranes, damages skeletal muscle and liver mitochondria, and ultimately leads to fatigue.GSH-Px is an endogenous antioxidant enzyme that plays an important role in maintaining the balance of antioxidant stress in the body [

27]. Studies have found that after continuous administration of areca nut for 14 days, the activities of SOD and CAT in mice increased significantly and the expression of MDA decreased significantly, indicating that areca nut had good antioxidant activity [

28].The results of this study showed that arecaline groups could significantly reduce the MDA content of mice, and significantly increase the expression levels of SOD, CAT and GSH-Px in mice, which was consistent with the results.

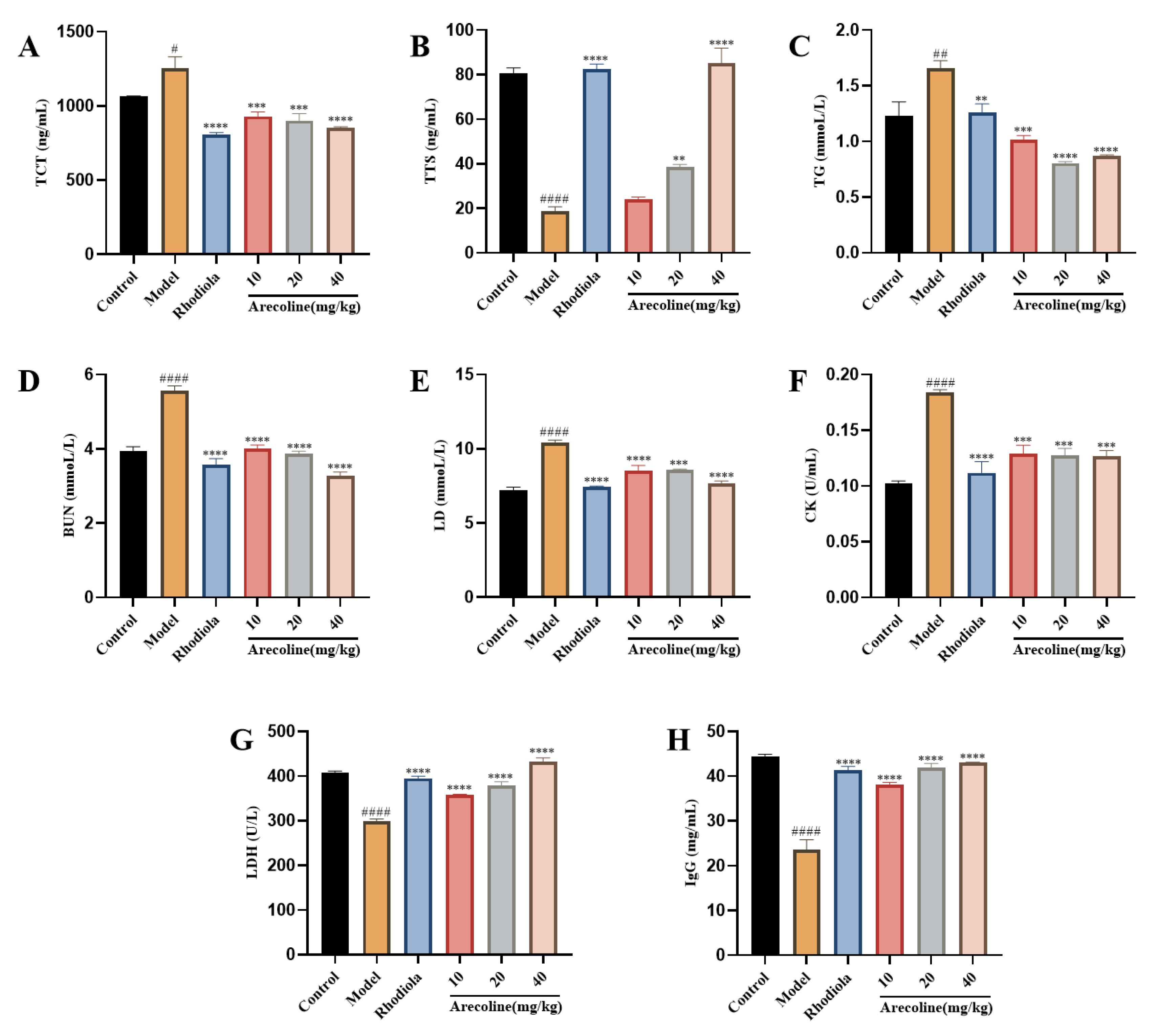

Previous studies have shown that CTC, TTC, BUN, LD, TG, LDH and CK levels are closely related to exercise [

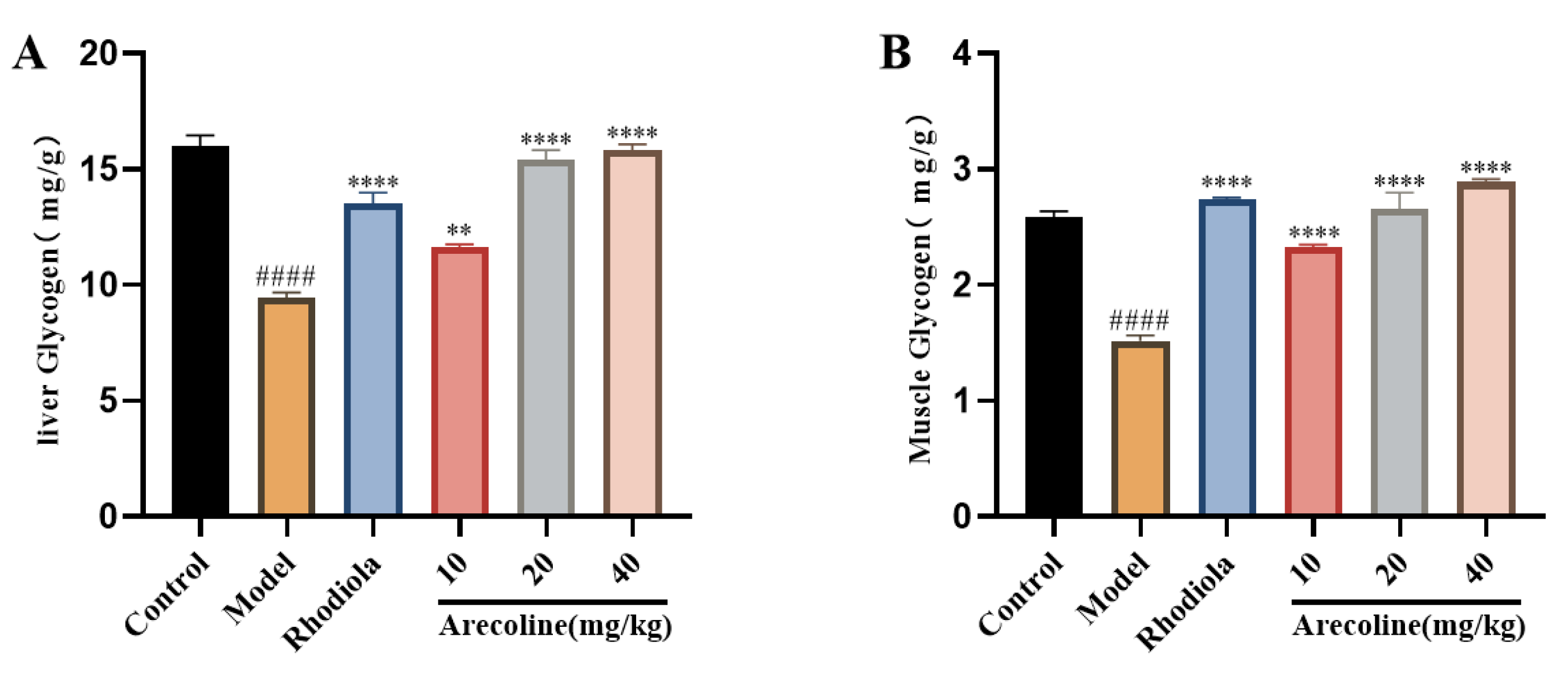

29].High intensity exercise accelerates the accumulation of LD.Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is an accurate indicator of muscle activity.Without adequate energy supply, anaerobic metabolism of sugars and catabolism of proteins increase urea levels and cause fatigue.This study showed that arecoline can reduce the content of serum CTC, BUN, LD, TG and CK, and finally play an anti-fatigue role, and provide sufficient evidence to prove that arecoline can regulate fatigue related biochemical indicators and reduce muscle damage.The body’s main source of energy for movement is glycogen, which is stored in the liver and muscles.Glycogen provides energy through peroxidation during high intensity exercise [

30,

31].Therefore, glycogen reserve can directly improve exercise ability and slow down the occurrence of exercise fatigue [

32].The contents of liver glycogen and muscle glycogen in arecoline group were significantly higher than those in model group.The results showed that arecoline was beneficial to delay energy consumption and had the significant anti-fatigue effect.

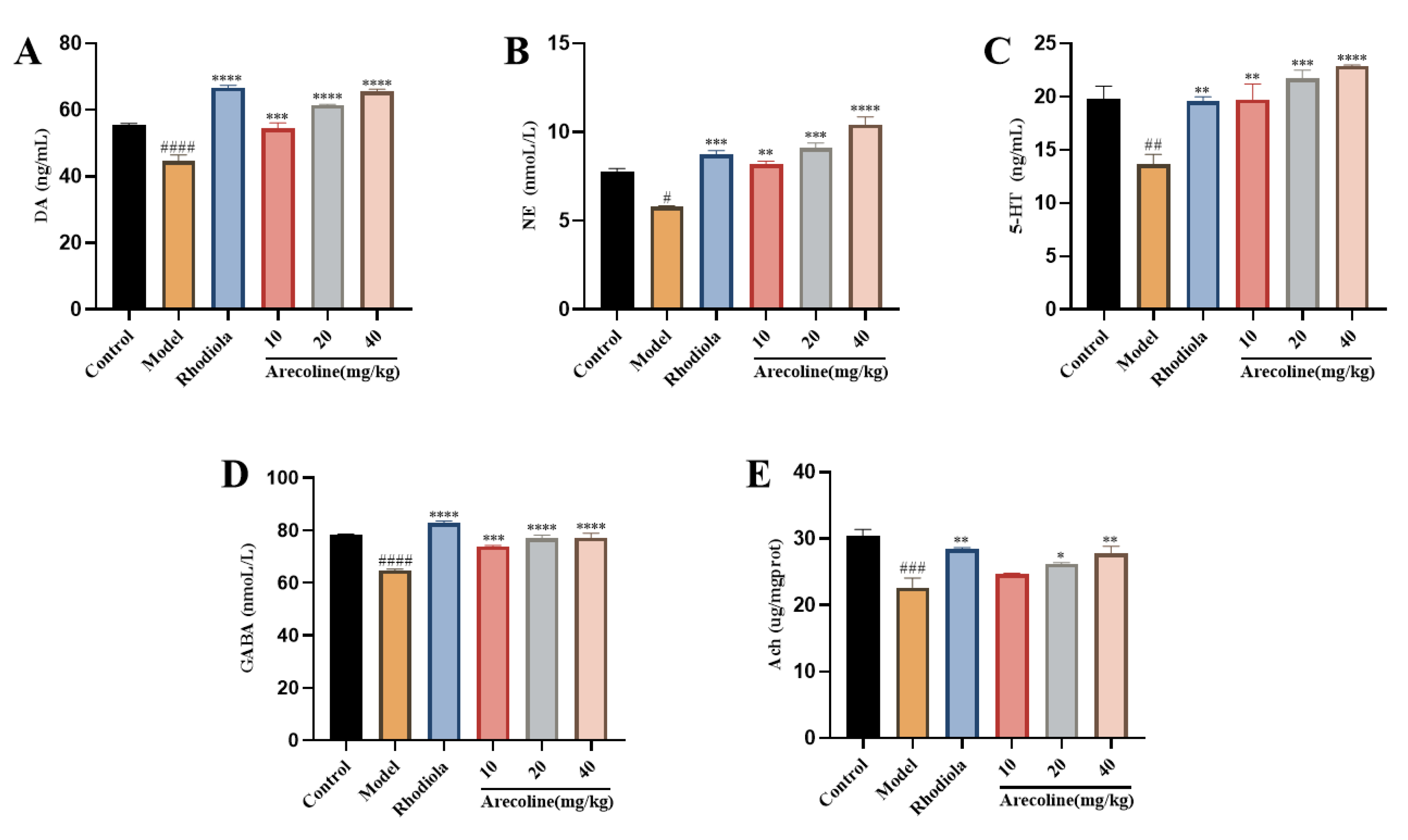

It has been reported that the gut microbiota affects the brain through a variety of pathways, including changes in the gamma-aminobutyrate (GABA) system, and contributes to a variety of mental disorders [

33].It is reported that areca was an effective inhibitor of central inhibition of the uptake of the transmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in rat brain sections [

34]. In addition, the alkaloids in betel nut are a potent depressant for GABA uptake, and chewing betel nut may affect sympathetic nerve function and increase the plasma concentration of norepinephrine [

35].The results of this study showed that arecoline interventions reversed the decline in 5-HT, DA, NE, GABA and Ach levels, suggesting that the improvement of cholinergic system function is one of the potential mechanisms of arecoline’s anti-fatigue activity.IL-6 and IL-1β have strong pro-inflammatory activity [

36] and can induce a variety of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines and chemokines.Similar to IL-1β, TNF-α is a pleiotropic pro-inflammatory cytokine that plays different roles in regulating multiple developmental and immune processes, including inflammation, differentiation, lipid metabolism, and apoptosis [

37].The dysregulation of TNF-α is associated with a variety of pathological conditions, such as infection, autoimmune diseases, cancer, atherosclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and intervertebral disc degeneration [

38,

39,

40]. Based on data from animal and clinical studies, studies have shown that a subpopulation of MDD patients in animal models and clinical trials have the effect of increasing plasma TNF-α levels, and blocking TNF-α improves depressive symptoms [

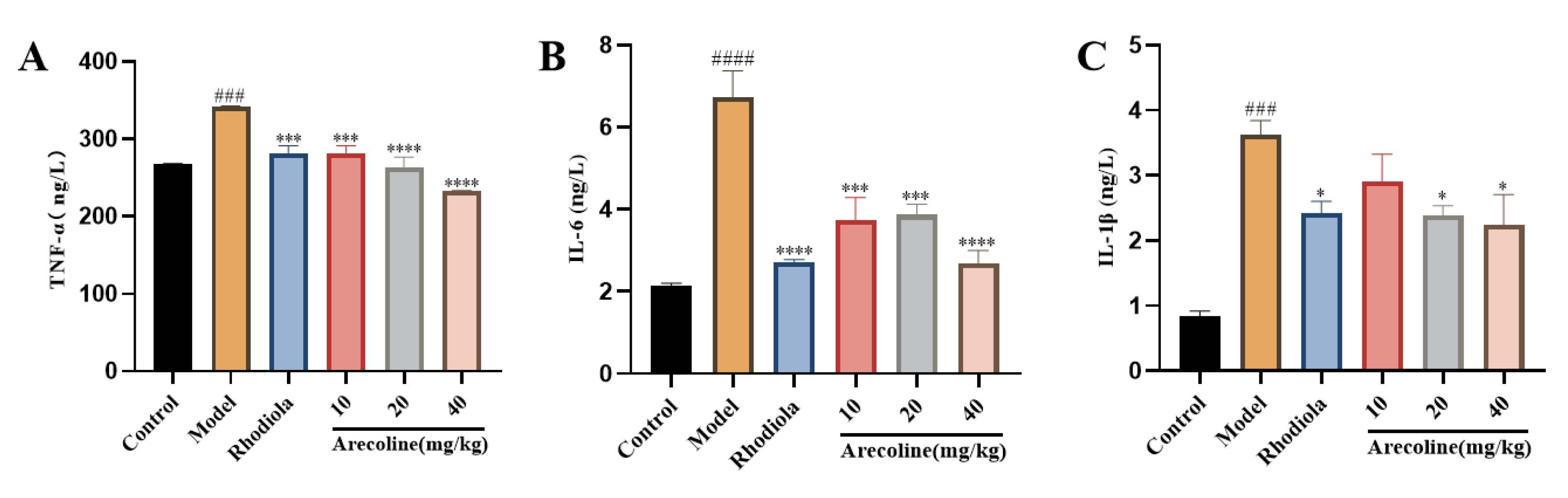

41]. In this study, arecoline interventions significantly reduced the contents of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β in mice, which was consistent with the above study.

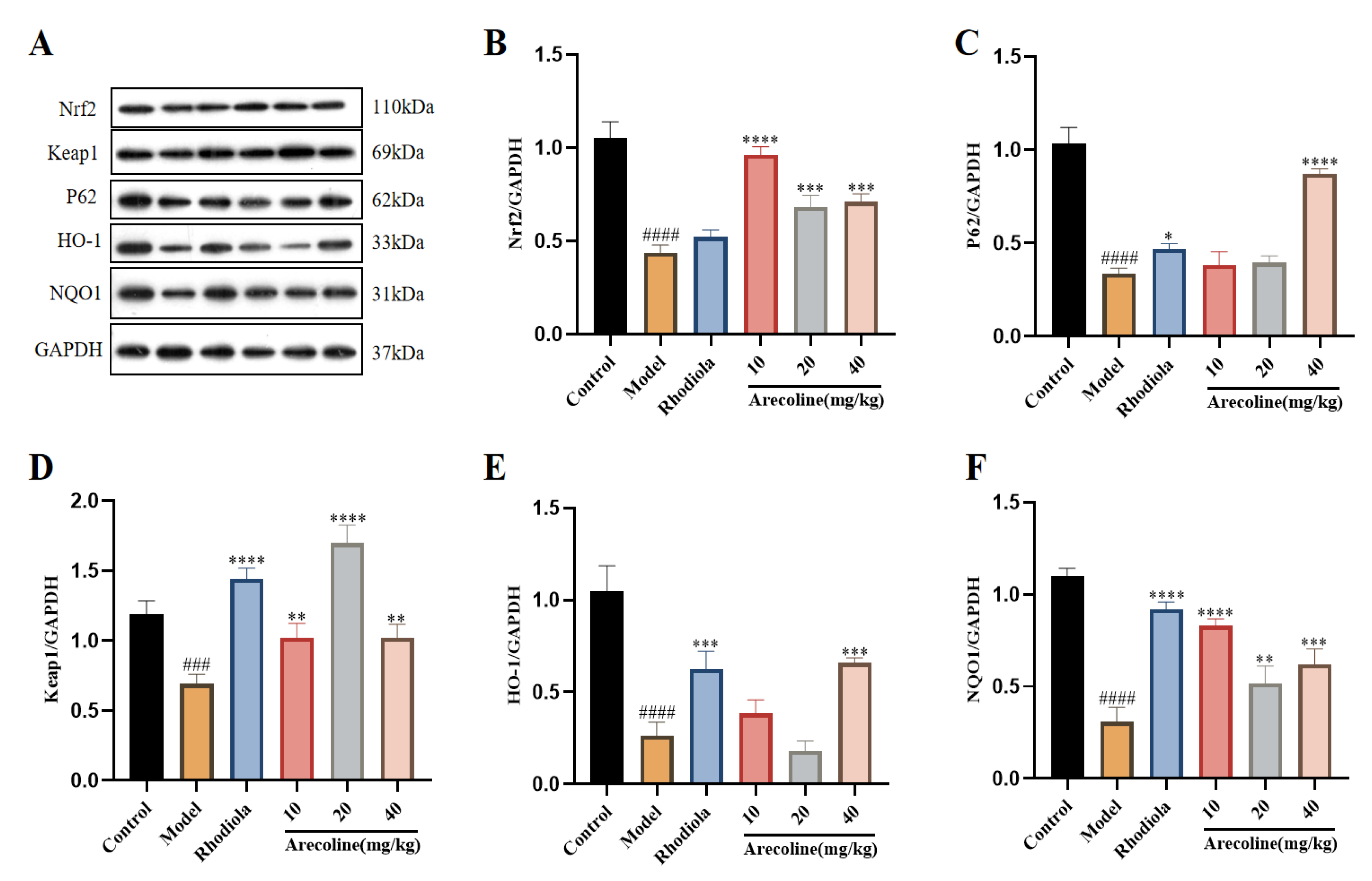

Studies have shown that cells will be damaged by reactive oxygen species and respond to the damage of harmful substances through a variety of mechanisms, the most important defense mechanism of oxidative stress is regulated through the Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway [

42]. Keap1 is a negative regulator of Nrf2 activity, which can directly bind Nrf2 and regulate the NRF2-KEap1 signaling pathway.When cells are stressed, p62 protein is phosphorylated at Ser403 and Ser351, and the phosphorylated p62 binds Keap1 through the KIR domain, resulting in Nrf2 dissociation from Keap1 and activation [

43].In addition, Keap1 restricts actin cytoskeleton and Nrf2 to cytoplasm by binding to them, respectively, and also plays an active role in Nrf2 ubiquitination and proteasome degradation [

44].It is shown that p62 can depolymerize Nrf2-Keap1 complex by binding to Keap1, which plays a positive regulatory role in NRF2-KEap1 pathway [

45].In addition, the aggregation of p62 and Keap1 has been detected in many human tumor cells, and certain neurodegenerative diseases,such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).They are also characterized by a large accumulation of protein aggregates in the central nervous system [

46] and are all related to p62.Nrf2 is one of the important transcription factors that protect cells from oxidative stress. It can regulate the transcription of target genes in the nucleus, including NAD(P)H, NQO-1 and HO-1 [

47], thereby avoiding apoptosis induced by oxidative stress.The results of this experiment showed that arecoline administration could significantly up-regulate the expression of Nrf2, Keap1, NQO1, P62 and HO-1 proteins, indicating that arecoline could improve the fatigue mice by regulating Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway.

Figure 1.

Effects of arecoline on gripping power, rod turning latency and weight-bearing swimming time of mice. (A) Before dosing Gripping power, (B) After dosing Gripping power, (C) Rod turning latency and (D) Weight-bearing swimming time. Data were expressed as means ± SEM (n = 12). # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01 indicate significant difference compared with the Control group. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 indicate significant difference compared with the Model group.

Figure 1.

Effects of arecoline on gripping power, rod turning latency and weight-bearing swimming time of mice. (A) Before dosing Gripping power, (B) After dosing Gripping power, (C) Rod turning latency and (D) Weight-bearing swimming time. Data were expressed as means ± SEM (n = 12). # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01 indicate significant difference compared with the Control group. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 indicate significant difference compared with the Model group.

Figure 2.

Effect of arecoline on serum biochemical indexes in mice.(A) TCT, (B) TTS, (C) TG, (D) BUN, (E) LD, (F) CK, (G) LDH and (H) IgG. Data were expressed as means ± SEM (n = 12). # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01 #### P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Control group. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Model group.

Figure 2.

Effect of arecoline on serum biochemical indexes in mice.(A) TCT, (B) TTS, (C) TG, (D) BUN, (E) LD, (F) CK, (G) LDH and (H) IgG. Data were expressed as means ± SEM (n = 12). # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01 #### P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Control group. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Model group.

Figure 3.

Effect of arecoline on oxidative stress indexes of gastrocnemius muscle in mice. (A) MDA, (B) SOD, (C) CAT and (D) GSH-Px. Data were expressed as means ± SEM (n = 12). ## P < 0.01, #### P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Control group. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Model group.

Figure 3.

Effect of arecoline on oxidative stress indexes of gastrocnemius muscle in mice. (A) MDA, (B) SOD, (C) CAT and (D) GSH-Px. Data were expressed as means ± SEM (n = 12). ## P < 0.01, #### P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Control group. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Model group.

Figure 4.

Effect of arecoline on glycolipid metabolism indexes in mice.(A) liver glycogen and (B) Muscle glycogen. Data were expressed as means ± SEM (n = 12). #### P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Control group. ** P < 0.01, **** P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Model group.

Figure 4.

Effect of arecoline on glycolipid metabolism indexes in mice.(A) liver glycogen and (B) Muscle glycogen. Data were expressed as means ± SEM (n = 12). #### P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Control group. ** P < 0.01, **** P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Model group.

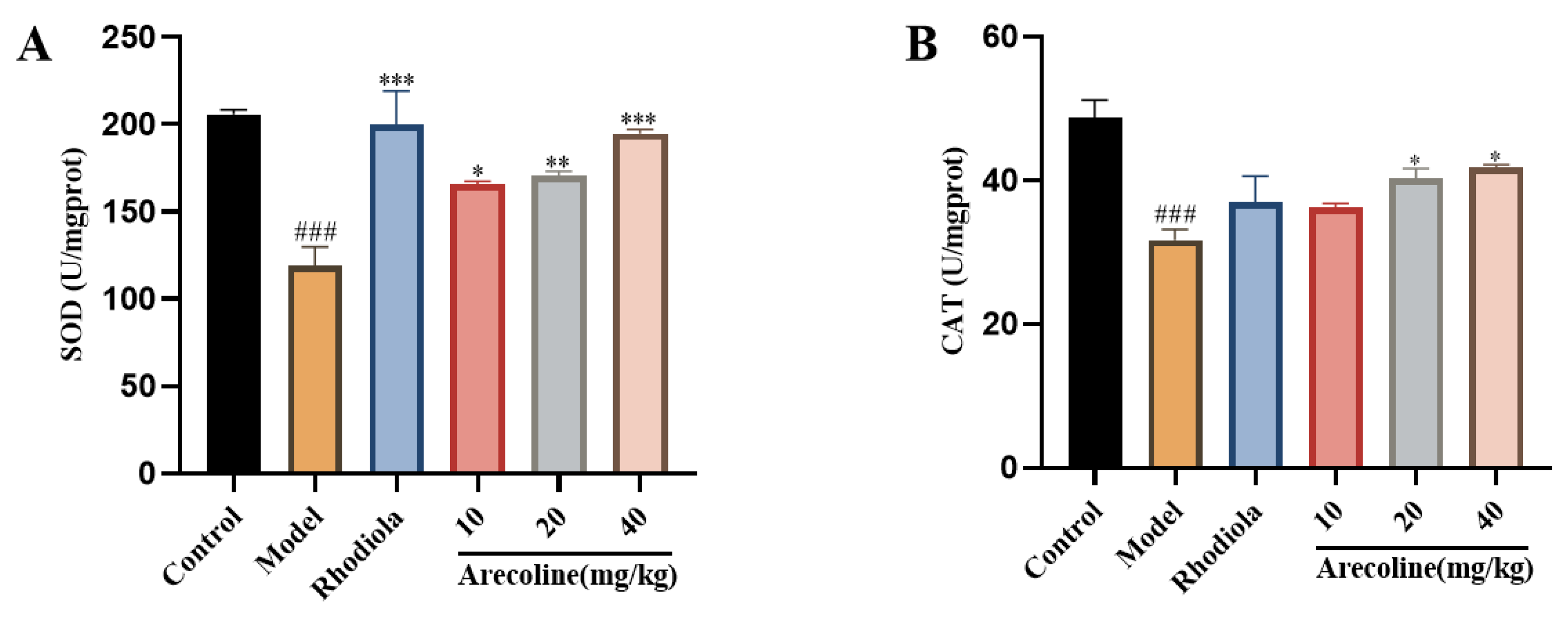

Figure 5.

Effect of arecoline on biochemical indices of mouse hippocampus. (A) SOD and (B) CAT. Data were expressed as means ± SEM (n = 12). ### P < 0.001 indicate significant difference compared with the Control group. * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001 indicate significant difference compared with the Model group.

Figure 5.

Effect of arecoline on biochemical indices of mouse hippocampus. (A) SOD and (B) CAT. Data were expressed as means ± SEM (n = 12). ### P < 0.001 indicate significant difference compared with the Control group. * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001 indicate significant difference compared with the Model group.

Figure 6.

Effect of arecoline on biochemical indices of mouse hippocampus. (A) TNF-α, (B) IL-6 and (C) IL-1β. Data were expressed as means ± SEM (n = 12). ### P < 0.001, #### P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Control group. * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Model group.

Figure 6.

Effect of arecoline on biochemical indices of mouse hippocampus. (A) TNF-α, (B) IL-6 and (C) IL-1β. Data were expressed as means ± SEM (n = 12). ### P < 0.001, #### P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Control group. * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Model group.

Figure 7.

Effect of arecoline on biochemical indices of mouse hippocampus. (A) DA, (B) NE, (C) 5-HT, (D) GABA and (E) Ach。 Data were expressed as means ± SEM (n = 12). # P < 0.05,## P < 0.01, ### P < 0.001, #### P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Control group. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Model group.

Figure 7.

Effect of arecoline on biochemical indices of mouse hippocampus. (A) DA, (B) NE, (C) 5-HT, (D) GABA and (E) Ach。 Data were expressed as means ± SEM (n = 12). # P < 0.05,## P < 0.01, ### P < 0.001, #### P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Control group. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Model group.

Figure 8.

Effects of arecoline on protein expression in gastrocnemius muscle were evaluated using western blotting.(A-F) The protein levels of Nrf2, Keap1, P62, HO-1 and NQO1 were normalized to GAPDH and their relative band intensities were quantified. Data were expressed as means ± SD (n = 3). ### P < 0.001, #### P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Control group. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Model group.

Figure 8.

Effects of arecoline on protein expression in gastrocnemius muscle were evaluated using western blotting.(A-F) The protein levels of Nrf2, Keap1, P62, HO-1 and NQO1 were normalized to GAPDH and their relative band intensities were quantified. Data were expressed as means ± SD (n = 3). ### P < 0.001, #### P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Control group. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001 indicate significant difference compared with the Model group.