1. Introduction

Insomnia is marked by difficulties in starting to sleep, recurrent awakenings at night, and a diminished quality of life, a widespread epidemic [

1]. The significance of adequate sleep is widely recognized, but due to increasing life pressures, the rate of insomnia continues to rise [

2]. Numerous factors are intricately associated with the prevalence of insomnia, including gender, diet, constitution, environment, and age, although these possible influencing factors have not yet been definitively reported. Additionally, insomnia is recognized as a significant contributor to multiple systemic diseases. An epidemiological investigation has indicated that insomnia frequently coexists with depression and anxiety [

3]. Meta-analyses have shown that individuals exhibiting symptoms of disruptions in sleep continuity or insomnia disturbances have a significantly increased incidence of hypertension [

4]. Benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepines are currently effective drugs for the treatment of insomnia [

5]. However, prolonged administration of these agents, especially among the elderly, is highly likely to lead to potential side effects, examples include cognitive impairment, dependence, and addiction [

6]. However, prolonged administration of these agents, especially among the elderly, is highly likely to lead to potential side effects, examples include cognitive impairment, dependence, and addiction [

7]. Therefore, herbal medicine, as an alternative therapy, can exert its effects with a lower risk of side effects in the treatment of insomnia.

The use of aromatherapy as a remedy for insomnia is globally acknowledged, encompassing the utilization of aromatic herbs within the realm of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) [

8,

9]. Aromatic herbs can activate brain functions and regulate the central nervous system. For example,

Lavandula angustifolia Mill. and

Rosa rugosa Thunb. had been used in clinical treatment [

9,

10]. Their essential oils exhibit a limited incidence of adverse reactions and exert sedative-hypnotic properties [

11]. Recent evidence highlights that plant extracts can enhance the operation of neurotransmitter systems and aid in sleep promotion. Existing research has demonstrated that

Magnolia sieboldii essential oils (MSEOs) have sleep-promoting and antidepressant effects. However, the literature on this type of research is minimal, and the mechanism by which MSEOs promote sleep is not fully defined [

12,

13].

The hypothalamus is the most important brain region in mammals and is involved in regulating the sleep-wake cycle. The currently recognized central neurotransmitters involved in the regulation of the sleep-wake cycle include serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, acetylcholine, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), among others. 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) plays a key role in regulating mood and sleep, and its deficiency is often associated with anxiety and depression; GABA, as the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, helps to reduce neuronal excitability, promoting sleep onset and the maintenance of deep sleep [

14]. GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter, while glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter; the two are the main components of the GABAergic system pathway, and an imbalance in their levels can cause disorders of the sleep-wake cycle rhythm. The levels of glutamate and GABA are influenced by glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) during the synthesis process. Glutamate can be converted into GABA through a decarboxylation reaction under the action of GAD, therefore, the content and activity of GAD can determine the conversion rate of glutamate to GABA [

15,

16].

In the field of sleep disorder research, the p-chlorophenylalanine (PCPA)-induced insomnia model is a typical pharmacological method used to evaluate the sedative and hypnotic effects of drugs. The core mechanism of this model lies in the inhibition of 5-HT synthesis by PCPA, which leads to a significant decrease in 5-HT levels in the peripheral and central nervous systems of experimental animals, thereby disrupting their circadian rhythms [

17]. Injection of PCPA causes damage to the hippocampus, which in turn affects the levels of monoamine neurotransmitters (such as 5-HT, norepinephrine, and dopamine) and amino acid neurotransmitters (such as GABA) [

18]. Compared with other modeling techniques, the PCPA-induced insomnia model has the characteristics of a short modeling cycle and pronounced insomnia symptoms, making it a valuable tool for evaluating potential treatments for insomnia [

19].

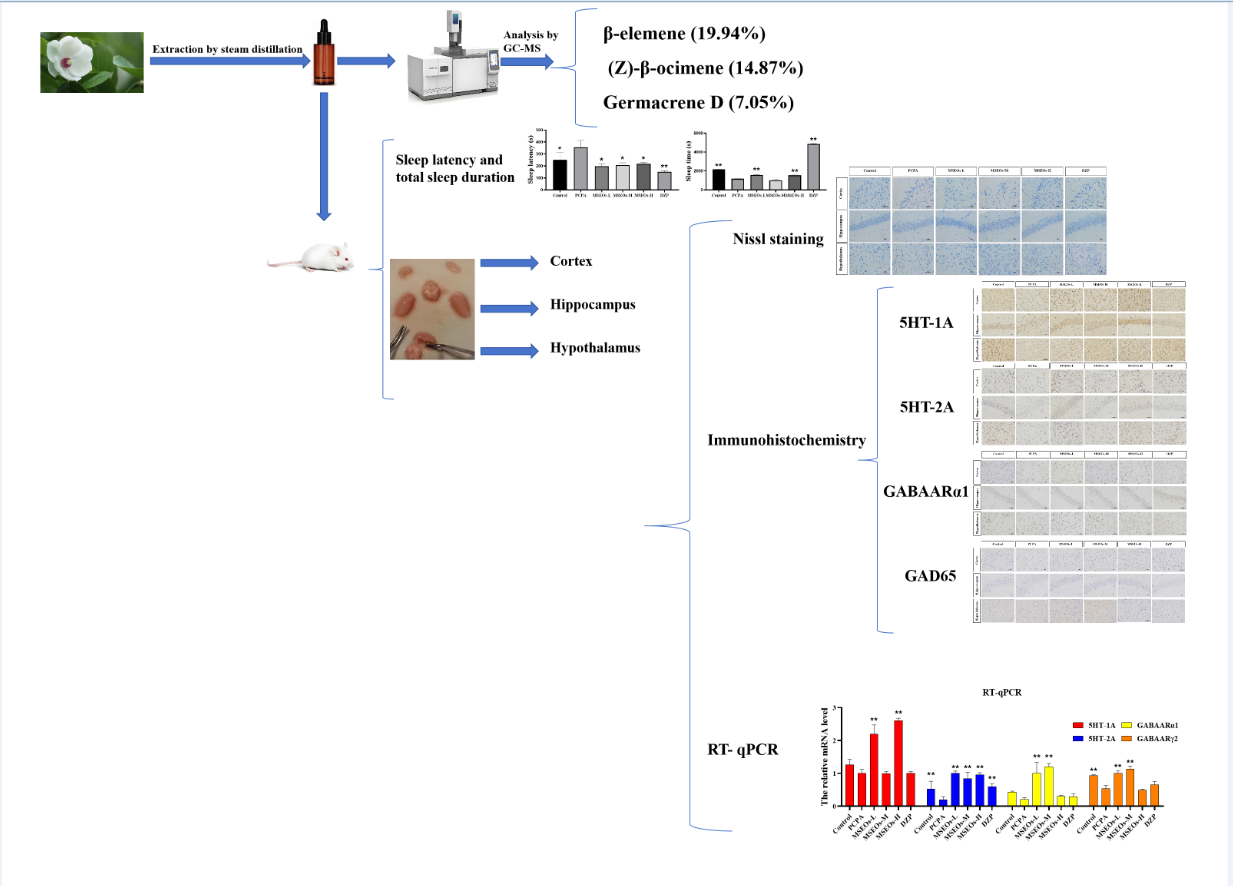

Therefore, the main objective of this study is to analyze the primary components of MSEOs, their efficacy in the treatment of insomnia, and the mechanisms of action in terms of neurotransmitters and neurophysiology. In this investigation, we employed a PCPA-induced insomnia model to assess the sleep-enhancing properties of MSEOs an analysis will be conducted focusing on the expression levels of 5-HT, GAD65, and GABA, along with normal neuronal levels in brain tissue. The objective of this research is to offer a scientific basis for further understanding the mechanism of MSEOs in the management of insomnia, as well as to promote more research into their clinical application, hoping to provide more solid support for clinicians’ treatment plans.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Plant Essential Oil

Dried leaves of

Magnolia sieboldii (5 kg) were purchased from Tong Ren Tang Company (Beijing, China). All plant samples were identified by Professor Nian Liu (Zhongkai University of Agriculture and Engineering, Guangzhou, China). As voucher specimens, part of the collected sample has been deposited for safekeeping at the Institute of Natural Medicine and Green Chemistry (Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou, China) (

Table 1). Use a pulverizer to grind the leaves of

Magnolia sieboldii into fine powder. Mix them with a little water in a beaker to form lumps. Put them in a microwave oven and heat for 2 minutes. Mix them with water in a ratio of 1:8 in an efficient essential oil distillation equipment (model: TX05-02, Chengdu, China), and collect the essential oil for 4 consecutive hours. Add anhydrous sodium sulfate to remove the water and store it at 4°C for experiments. The yield of essential oil was determined using the subsequent formula:

2.2. Conditions for GC-MS Determination

Essential oils were detected by a DSQ-II Ultra gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (Thermo, USA) which was equipped with a DB-5MS capillary gas chromatographic column (0.25m 0.33μm) (Agilent, USA). Temperature program: 100°C (10 min) 3°C/min 250°C. The vaporization temperature is 250°C. The volume of the injection was 1.0 µl; the Helium flow was 1.0 ml/min. Injection method: shunt; The split ratio was 20:1. The bar of mass spectrometry: ion source is electron blast; the temperature is 200°C; Energy: 70 e V, scanning range: m/z 30 ~ 550 amu.

2.3. PCPA-Induced Insomnia

24 healthy adult male KM mice, SPF grade, aged 6-8 weeks were from Southern Medical University (license number: SCXK (Guangdong)2016-0041). All the animal experiments were performed under the Guidelines for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Guangdong University of Technology (Guangzhou, China), and experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Guangdong University of Technology (Guangzhou, China). Experimental mice were adaptively fed for a week under conditions of 24±1°C temperature and a 12-hour light/dark cycle. A total of 24 male Kunming mice were stochastically divided into six groups, including the MSEOs-L group (25 mg/kg), MSEOs-M group (50 mg/kg), MSEOs-H group (100 mg/kg), control group, PCPA group, and diazepam (DZP) group (0.2 mg/ml). Filter paper is cut into the same size and soaked in different concentrations of essential oil solutions. Then filter paper was placed in four corners of the cage so that each mouse could sniff it for an hour. The experimental procedure is shown in

Figure 1, the weight of each mouse was recorded daily before inhalation. The cage where the control group mice lived was furnished with filter paper soaked in normal saline containing 1%Tween80 for 1h. Four days into the animal study, except for the control group of mice injected with saline containing 1% Tween 80 (PH7-8), the other groups of mice were administered with PCPA at a dosage of 0.1 mL per 10 grams of the animal’s body mass for two days. Behavior observation was carried out in mice after the injection. The mice exhibited continuous activity throughout the day, displaying heightened levels of excitability and irritability. Additionally, they experienced a disruption in their circadian rhythm, along with elevated water and food consumption, while their sleep duration was markedly reduced. The group injected with PCPA was significantly different from the control group.

2.4. Pentobarbital-Induced Sleep Test

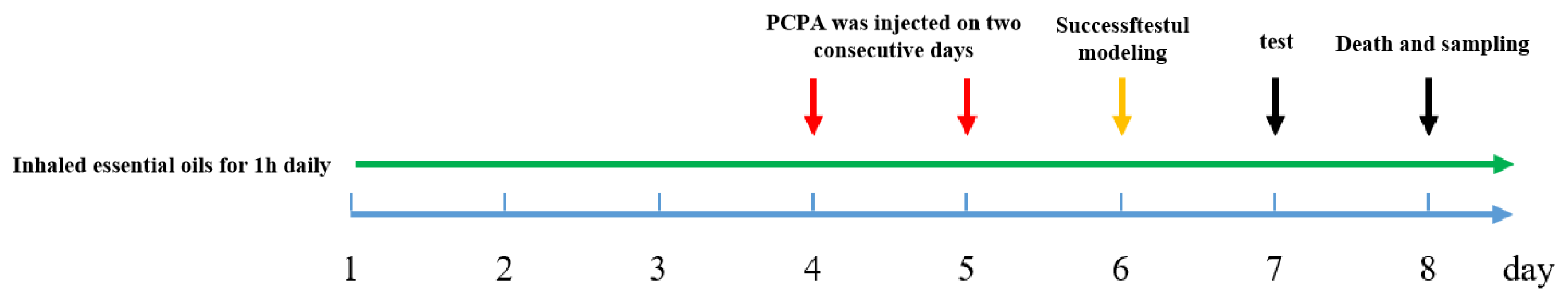

The test flow is shown in

Figure 2, half an hour following the final dose, sodium pentobarbital was administered intraperitoneally to the mice at a dose of 50 mg/kg to induce sleep. The number of turning over and sleep state, the time falling asleep (TS) the timing of the drug administration (TR), the latency to sleep onset, and the time of subsequent arousal were documented (TW).

2.5. BCA Assay

Following the above experiment, the mice were subjected to euthanasia, and blood samples were obtained through the excision of the ocular globes. Blood samples were subjected to centrifugation at a rotational speed of 2500 rpm for a period of 5 minutes at 4°C in order to isolate the serum. Protein levels in serum were measured by a Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) protein assay Kit (Shanghai, China).

2.6. ELISA Assay

The level of 5-HT in the hypothalamus of mice was measured using an ELISA assay kit (Shanghai, China). After the experiment, the mice were euthanized, and the hypothalamic tissue was quickly removed and then rinsed with cold saline to eliminate residual blood. Hypothalamic tissues were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), homogenized, and centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected. The procedure was carried out in line with the instruction manual provided in the ELISA kit, and absorbance was assessed at a wavelength of 450 nm, a standard curve was established to calculate the concentration of each detection index.

2.7. Immunohistochemistry Assay

After the mice were killed, their brains were isolated on an ice pad. The remaining blood on the tissues was irrigated with saline solution and blotted with filter paper. Apply 4% paraformaldehyde to the brain tissue samples for a 24-hour fixation period and then embed the processed brain tissue in paraffin sections that were sliced at 4 µm using a slicing machine (CUT 5062, Shanghai, China). The slides were dried for 2 h at 60°C. Afterward, the specimens were soaked in absolute ethanol solutions I and II for 10 minutes each, this was followed by 5-minute immersions in 95%, 90%, 85%, and 70% ethanol. Afterward, then wash the slices with PBS and immerse them in a buffer solution of sodium citrate adjusted to a pH of 6.0 under elevated temperatures for antigen repair. Subsequently, mouse brain tissue sections underwent treatment with 3% H₂O₂ for 25 minutes under dark conditions so that endogenous peroxide was blocked, tissues were blocked using 1.5% normal goat serum. Tissue blocks were incubated with a 15000-fold dilution of rabbit antiserotonin (Incstar, Stillwater, MN) at 37°C for 2 hours, subsequently, the sample was treated with a 12500-fold dilution of rabbit anti-serotonin transporter (Inc-star) for 15 min, 5000-fold dilution of rabbit anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (Pel-Freez Biologicals) for 15 min. Color reaction was performed using 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB).

2.8. Nissl Staining Assay

The embedded paraffin tissues were sliced at 5 µm and soaked in xylene I and xylene II for 10 minutes each, subsequently in 95%, 90%, 85%, and 70% ethanol with each stage lasting 5 minutes. The sections were subjected to staining with a 0.1% solution of cresyl violet for 20 minutes, followed by rinsing with distilled water. Dehydration and clearing of paraffin sections were performed as follows: First, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were subjected to primary dehydration in 70% ethanol solution for 2 minutes. Subsequently, the sections were transferred to 80% ethanol solution for intermediate dehydration, again maintained for 2 min. Further, the sections were subjected to advanced dehydration in 95% ethanol solution and the treatment time was also 2 min. Immediately following, complete dehydration with absolute ethanol, and the sections were immersed in 100% ethanol for 5 minutes each time for a total of two sessions. Then, after dewaxing and clearing, the sections were immersed in xylene for 10 minutes each time to complete two clearing steps. Finally, the paraffin sections were sealed with resin.

2.9. RT-qPCR

Upon conclusion of the two-week treatment regimen, the hypothalamic and hippocampal regions were swiftly excised from the mouse skulls. These excised tissues were subjected to a delicate rinsing process with chilled physiological saline before being flash-frozen on dry ice. Following this, they were preserved at a temperature of −80°C. A sample weighing 50 milligrams from either the hypothalamus or hippocampus was processed in Trizol for a comprehensive homogenization to isolate total RNA. The synthesis of cDNA was carried out by the protocols provided with the cDNA synthesis kits. After this, the produced cDNA was subjected to amplification using primer sequences as detailed in

Table 2.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

A comprehensive one-way analysis of variance was conducted on the entire dataset with the aid of GraphPad Prism version 8.0.2 (developed by GraphPad Software, USA). After this, a Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test was applied to ascertain any statistically significant disparities between the control and experimental cohorts, with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05 or p < 0.01. To conduct a robust statistical power analysis and to establish the appropriate sample size, R version 4.2.3 software (provided by the R Foundation for Statistical Computing, based in Austria) was utilized, in conjunction with the ‘pwr’ add-on. The findings are presented as mean values accompanied by standard errors, and the level of confidence for these results is set at 95%. This data was meticulously gathered through a minimum of three separate and autonomous experimental replicates.

3. Results

3.1. Essential Oil Component Analysis

The GC-MS analysis yielded results (

Table 3) identifying 69 compounds, which comprised 95.71% of the overall essential oil composition. There were 24 Sesquiterpene hydrocarbonszn, 13 Oxygenated sesquiterpenes, 11 Total monoterpenoids, and Oxygenated monoterpenes 6 and 15 other substances, accounting for 60.47%, 10.94%, 29.36%, 6.85% and 5.61% of the total mass, respectively. The content of β-elemene (19.94%) was the highest. Followed by (Z)-β-ocimene (14.87%), Germacrene D (7.05%), cis-(+)Nerolidol (4.51%), isocaryophyllene (3.63%), etc. β-elemene has ameliorative effects on inflammation in the CNS [

20] and is found as a major component of many plant essential oils that promote hypnosis [

21,

22]. Several studies have shown that Nerolidol is an important component capable of inducing sedation in mice [

23], as indicated by decreased motility and prolonged sleep duration induced by pentobarbital [

21]. Nerolidol has a protective effect against neuroinflammation [

24] and the anti-inflammatory activity is associated with the gabaergic system [

25], Nerolidol also potentiates neuronal effects by activating the activation of 5-HT receptors, especially the 5-HT1A and 5-HT4 isoforms [

26]. Isocaryophyllene has good anticancer activity [

27], but its effect on the nervous system has not been reported. The effect of

Magnolia sieboldii essential oil on improving sleep disorders may be related to the effects of β-elemene and Nerolidol on the nerve center, as well as the results of the interaction with other components.

3.2. Impact of MSEOs on Sleep Duration and Latency to Sleep Onset in Insomniac Mice

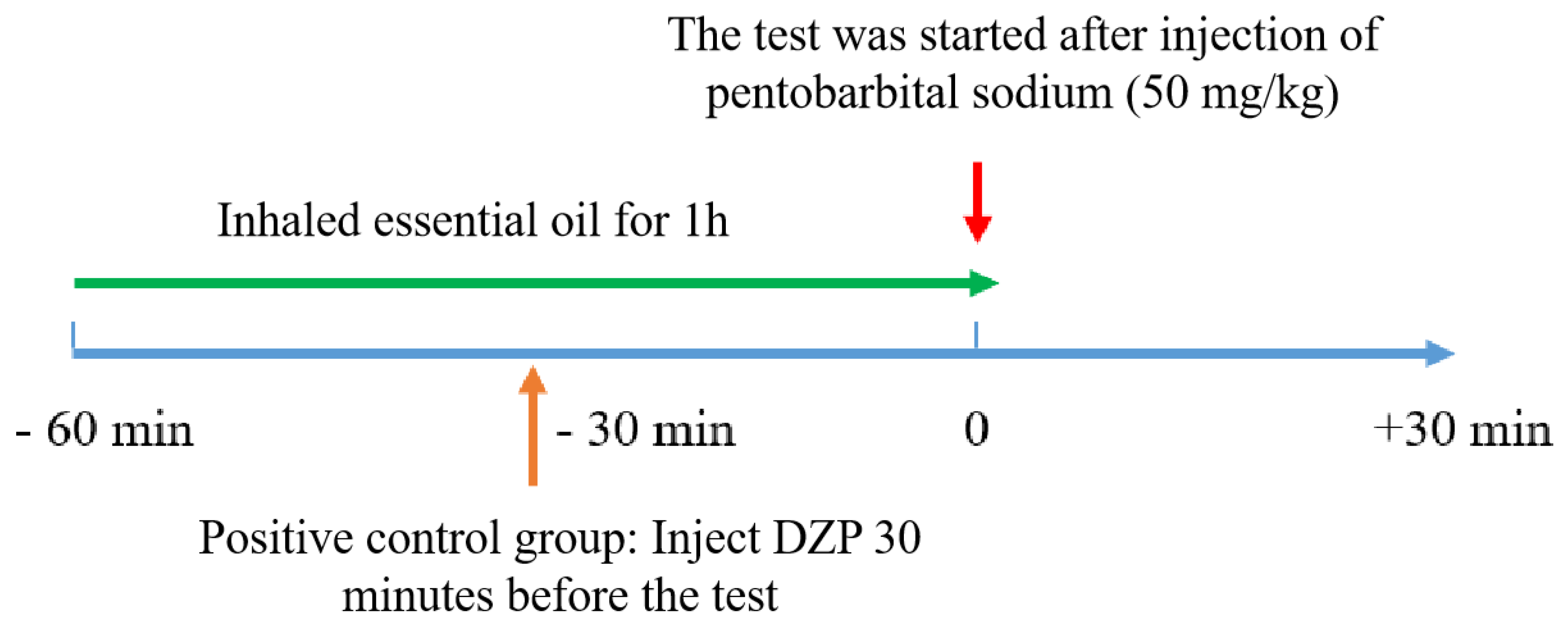

The experimental results are shown in

Figure 3. The sleep latency of PCPA group mice was significantly longer than that of the control group (

P<0.05) (

Figure 3A). Additionally, the total sleep duration of the PCPA group mice was markedly shorter than that of the control group (

P<0.01) (

Figure 3B). It can be seen that the PCPA can reduce the overall duration of sleep while extending the duration of sleep latency, causing insomnia in mice. This indicates that the insomnia mouse model has been successfully established. After treatment with MSEOs, compared to the insomnia model group, the sleep latency of mice treated with three concentrations of MSEOs was significantly reduced (

P<0.05) (

Figure 3A). Moreover, the sleep duration of mice in the MSEOs-L and MSEOs-H treatment groups was significantly increased compared to the PCPA group (

P<0.01) (

Figure 3B). In summary, the administration of PCPA via intraperitoneal injection is an effective method for creating a mouse model of insomnia, and treatment with MSEOs can effectively enhance sleep quality in mice with insomnia caused by PCPA. The analysis of the figure 3 shows that in the sleep latency test, the three concentration groups of MSEOs exhibited longer sleep latency compared to the DZP positive control group, but slightly shorter compared to the control group, showing a trend closer to the normal control group. In terms of total sleep duration, the sleep duration of the MSEOs-L and MSEOs-H groups was slightly lower than that of the blank control group, but the difference was not significant. At the same time, compared to the PCPA group, the MSEOs-L and MSEOs-H groups demonstrated significant positive effects in alleviating symptoms of insomnia. Although the sleep duration of the MSEOs-L and MSEOs-H groups was relatively shorter compared to the DZP group, the sleep duration of these two groups was closer to the blank control group, indicating that MSEOs can effectively regulate sleep quality to a normal level, reducing the possibility of excessive sleep. In contrast, DZP treatment may cause adverse reactions of prolonged sleep duration.

3.3. Neuroprotective Effects of MSEOs on PCPA-Induced Insomnia Mice

Insomnia is intricately linked to neuronal cell damage in brain tissue. When neurons within the hippocampal region sustain damage or undergo atrophy, these alterations adversely impact rapid eye movement (REM) sleep [

37]. Additionally, more severe instances of insomnia may arise from significant damage to the hypothalamus [

38]. Normal neuronal cell bodies contain a large amount of Nissl bodies, which are basophilic clumps or granules primarily involved in protein synthesis [

39]. Nissl bodies can be labeled using toluidine blue staining, which also highlights the neuronal contour and nucleus. Compared to the control group statistical analysis of the count of neurons in the hypothalamus, hippocampus, and cerebral cortex revealed that the PCPA group had fewer uninjured neurons located within the cerebral cortex, hypothalamus, and hippocampus. However, after administration of MSEOs, the count of normal neurons located within the hippocampus, cerebral cortex, and hypothalamus increased, especially with MSEOs-M and MSEOs-H in the hypothalamus and MSEOs-L in the hippocampus showing the most pronounced effects (

p < 0.01) (

Figure 4B). This indicates that MSEOs have a protective effect on neurons, which may be related to their function in treating sleep disorders.

3.4. Expression of 5HT-2A and 5HT-1A

Serotonin, also widely recognized as 5-HT, is a classical neurotransmitter in the central nervous system that significantly influences the regulation of sleep and wakefulness. Serotonin is acknowledged as one of the key mechanisms contributing to insomnia [

40]. Its two important subtypes are 5HT-1A and 5HT-2A receptors, respectively. The 5HT-2A and 5HT-1A proteins are extensively distributed throughout the brain, and play a role in the modulation of sleep. The 5HT-2A and 5HT-1A proteins are extensively distributed throughout the brain, and play a role in the modulation of sleep [

41,

42], anxiety, and emotions [

43]. Previous research has indicated that 5HT-1A is densely present in the hippocampus, with evidence suggesting that the activation of these receptors is effective in alleviating anxiety symptoms. In general, low-dose agonists of the 5HT-1A receptor have been found to enhance both deep sleep and light sleep [

44]. PCPA can cause insomnia by inhibiting presynaptic 5HT-1A autoreceptors and reducing 5-HT levels [

45].

The test results show (

Figure 5) that compared to the normal control group the 5HT-1A expression in mice’s cortex, hippocampus, and hypothalamus within the PCPA group is notably lower (

P<0.05) (

Figure 5B), and in the cortex, hippocampus, and hypothalamus, the expression level of 5HT-2A was also decreased (

P<0.01) (

Figure 6B). Compared to the insomnia model group, MSEOs treatment resulted in increased levels of 5HT-1A in the cerebral cortex, hypothalamus, and hippocampus of mice across all three dosage groups, with the MSEOs-H group showing the most favorable results in the hippocampus and hypothalamus (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 5B). The expression levels of 5HT-2A in the cortex, hypothalamus, and hippocampus of mice in all three dosage groups also increased, with MSEOs-L showing better effects in the cortex and hippocampus (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 6B). It is evident that MSEOs treatment effectively inhibits the decrease in 5HT-2A and 5HT-1A levels induced by PCPA in mice with insomnia, maintaining the levels of 5HT-2A and 5HT-1A in mice at normal levels. It can be seen that treatment with MSEOs effectively inhibited the decrease in 5HT-2A and 5HT-1A levels in mice exhibiting PCPA-induced insomnia, maintaining the levels of 5HT-2A and 5HT-1A in the mice at normal levels.

3.5. Effect of MSEOs on GABAARα1 Levels in Mice with Insomnia

GABA is an important inhibitory neurotransmitter, and it also effectively inhibits the activity of most neurons in the suprachiasmatic nucleus [

46], its inhibitory effect is intricately connected to circadian rhythms in animals [

47]. GABA is commonly used as an important indicator for evaluating central nervous system (CNS) function and is also a common metric in insomnia research [

48], with the A receptor subtype GABAARα1 being the most prevalent [

49]. The GABA signaling pathway is primarily mediated by GABAA and GABAB receptors. GABAARα1 and GABAARγ1 in GABAA receptors may be key targets for multi-target sleep-enhancing agents in improving insomnia. Studies have shown that the expression levels of GABAARα1 and GABA were significantly decreased in the PCPA-induced insomnia mouse model [

50]. To verify whether MSEOs can exert their insomnia-improving effects through the modulation of the expression of GABAARα1 in the animals, we quantified the levels of GABAARα1 in the mouse brain tissue.

Compared with the control group, the expression of GABAARα1 in the cortex, hippocampus, and hypothalamus of the insomnia model group was decreased (

Figure 7). It can be seen that PCPA can cause a decrease in the GABAARα1 content in mice exhibiting insomnia. However, after intervention with MSEOs, the GABAARα1 levels in brain tissues of MSEOs mice were higher than those of PCPA mice, especially in the MSEOs-M group (

p < 0.01). This indicates that MSEOs can inhibit the decrease in GABAARα1 levels in PCPA-induced sleep disorders in mice, maintaining the GABAARα1 content in the mice at normal levels.

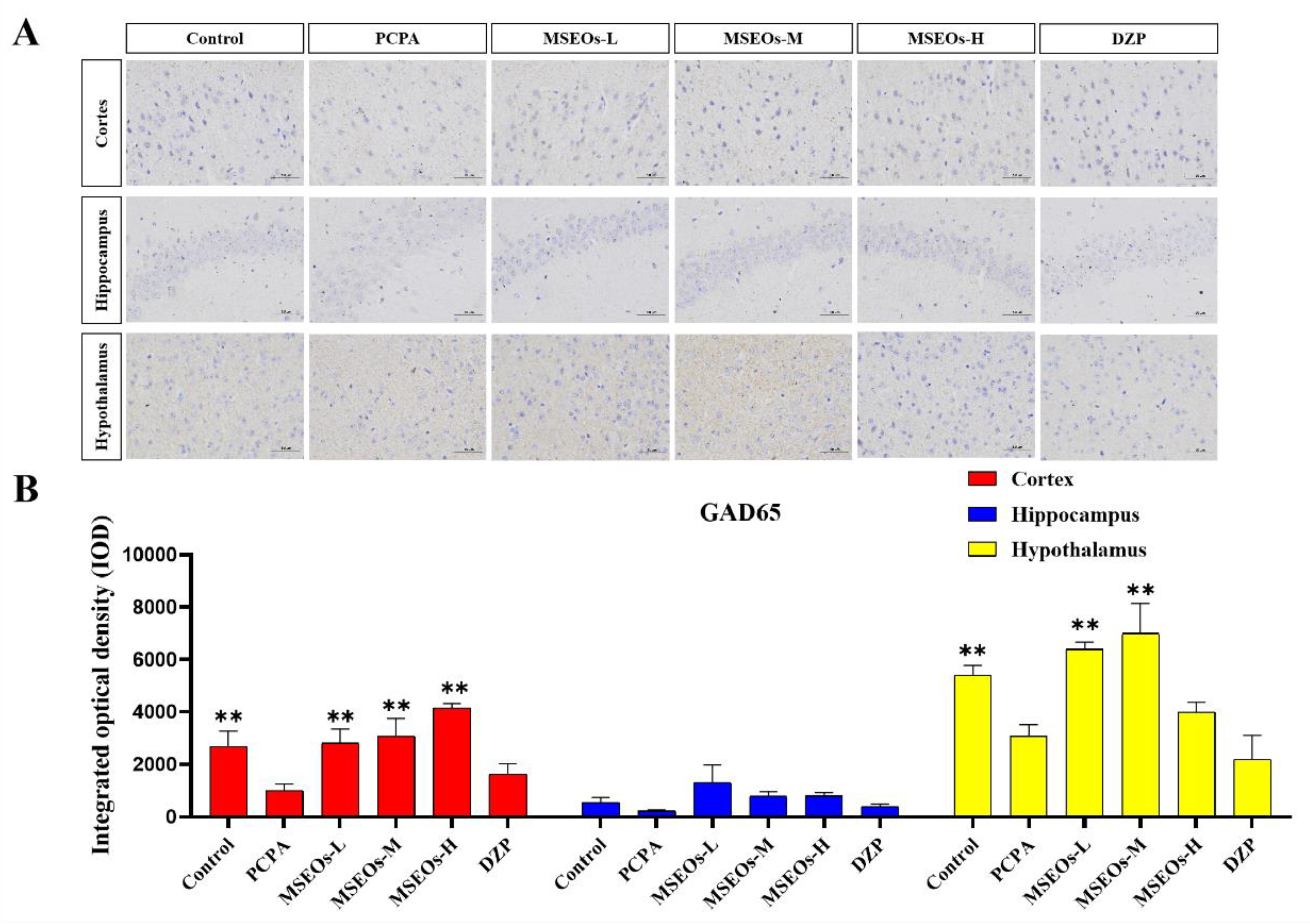

3.6. Impact of MSEOs on GAD65 Protein Levels in the Brain of Mice Subjected to Sleep Deprivation

GABA in the brain mainly catalyzes glutamate synthesis through the GAD enzyme, which converts glutamate into GABA [

16]. There are two isoforms of glutamate decarboxylase, namely GAD67 and GAD65 [

51]. Research shows that GAD65 is sensitive to changes in GABA and is commonly found in the cytoplasm of GABAergic neurons, mainly responsible for the synthesis and release of GABA in the brain [

52]. Previous research has indicated a decrease in GAD65 levels within the cerebral tissue of mice experiencing PCPA-induced sleep disorder treatment [

53]. Consequently, the impact of hypnosis of the respective pharmacological agents can be ascertained through the quantification of GAD65 protein expression within the cerebral tissue of murine subjects after their administration.

The GAD65 content in the cortex and hypothalamus of the PCPA group was markedly lower than that of the control group(

P<0.01) (

Figure 8B), indicating that intraperitoneal injection of PCPA results in a reduction of GAD65 levels within the brain tissue. In contrast, GAD65 levels in the hypothalamus, cortex, and hippocampus of mice administered with MSEOs were elevated compared to both the blank and the PCPA groups, In the study, the MSEOs-H group showed the most significant effect in the cerebral cortex (

P<0.01), while the MSEOs-L group performed better in the hippocampus, and the MSEOs-M group was most prominent in the hypothalamus (

P<0.01). The result indicates that treatment with MSEOs is capable of effectively preventing the decline in GAD65 protein levels in the cerebral tissue of mice experiencing PCPA-induced sleep disturbance, maintaining the GAD65 content in their bodies at normal levels.

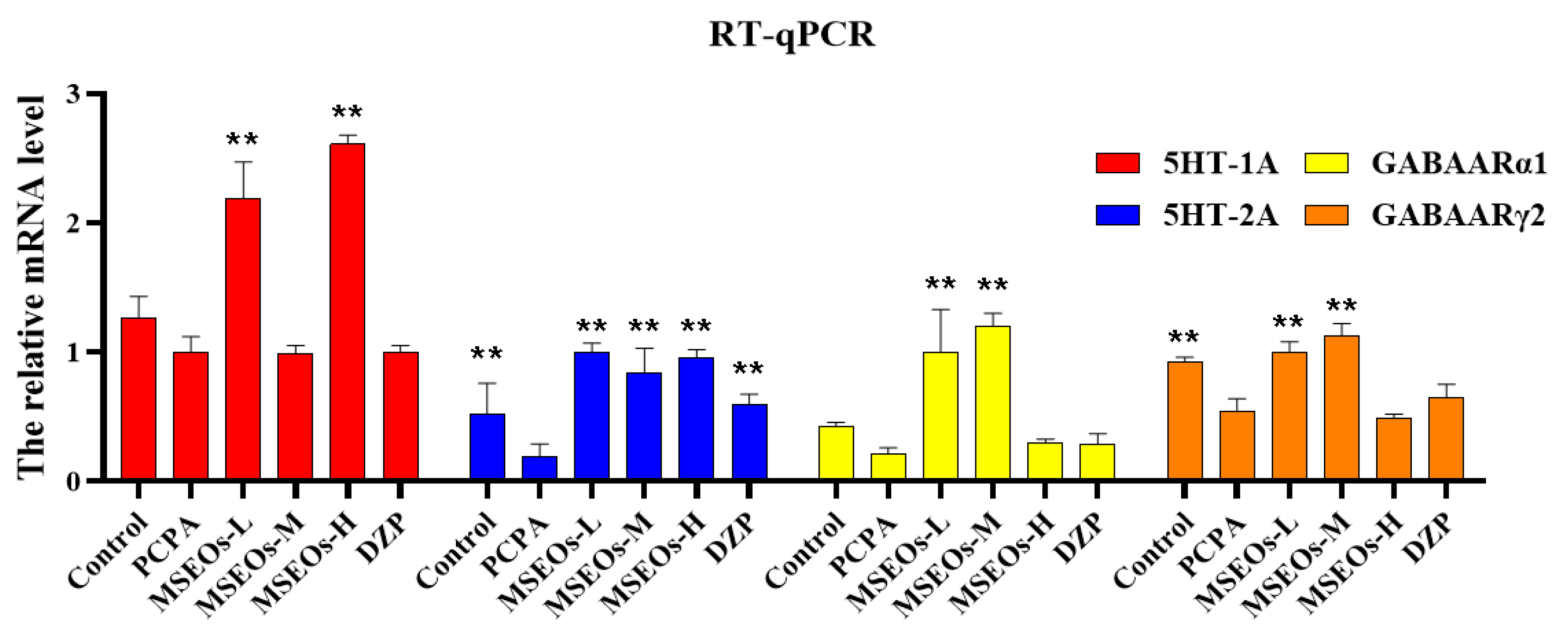

3.7. RT- qPCR

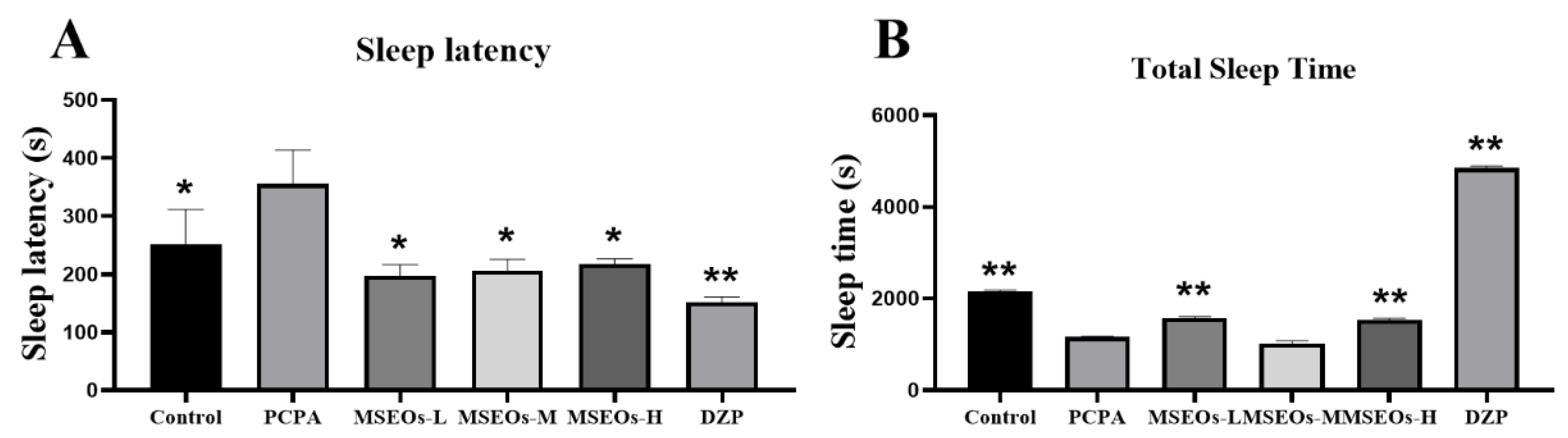

The results of RT-qPCR (

Figure 9) indicated that relative to the control, the mRNA expression of 5HT-2A, 5HT-2A, GABAARα1, and GABAARγ2 in the insomnia PCPA-treated mice was diminished. Following treatment with MSEOs, the mRNA levels of GABAARα1, GABAARγ2, 5HT-2A, and 5HT-1A in brain tissue of the three different concentrations of MSEOs treatment groups showed varying degrees of upregulation when compared to the insomnia model group. In particular, the expression of 5HT-1A was most significantly increased after treatment with MSEOs-H (

p<0.01), followed by the MSEOs-L treatment group (

p<0.01), which corresponded with the immunohistochemical staining results in the cerebral cortex, hypothalamus, and hippocampus. Similarly, the expression of 5HT-2A was also significantly increased after MSEOs-H treatment (

p<0.01), followed by the MSEOs-L treatment group (

p<0.01), showing consistency with the staining results of 5HT-1A in the cerebral cortex, hypothalamus, and hippocampus. For the expression of GABAARα1, the enhancement effect was most pronounced in the MSEOs-M treatment group (

p<0.01), followed by the MSEOs-H treatment group (

p<0.01), which was roughly similar to the staining pattern of 5HT-1A in the corresponding brain regions. As subunits of GABAAR, α1, and γ2 subunits are interdependent in receptor function, and the increase in GABAARγ2 also contributes to the treatment of insomnia [

50]. The results in

Figure 9 show that the expression patterns of GABAARα1 and GABAARγ2 were basically consistent, with the most significant increase after MSEOs-M treatment (

p<0.01), followed by the MSEOs-L treatment group (

p<0.01). These findings provide strong molecular biological evidence for the effectiveness of MSEOs in the treatment of insomnia.

4. Conclusion

The results of this study indicated that MSEOs could improve insomnia by prolonging the total sleep time and reducing sleep latency in mice. Furthermore, MSEOs can modulate key targets in the sleep-wake regulation pathway, as evidenced by increased levels of GAD65, GABAARα1, 5HT-2A, and 5HT-1A following treatment. Additionally, MSEOs were found to mitigate PCPA-induced neuronal damage, suggesting a neuroprotective role. RT-qPCR analysis confirmed that MSEOs upregulate the mRNA expression of 5HT-1A, 5HT-2A, GABAARα1, and GABAARγ2, indicating that MSEOs may act by enhancing the GABAergic and serotonergic systems to elicit their sedative and neuroprotective effects. These findings underscore the potential of MSEOs as a therapeutic agent for sleep disorders and as a neuroprotective agent against neurodegenerative conditions.

5. Discussion

In recent years, MSEOs have gradually demonstrated their potential in the therapeutic approach to insomnia [

12]. The findings from this research indicate that

Magnolia sieboldii can improve sleep quality in mice with PCPA-induced insomnia and modulate the concentrations of pertinent neurotransmitters. This finding provides experimental evidence for its potential therapeutic application in the management of insomnia. At present, the primary therapeutic approaches for insomnia mostly rely on chemical drugs, such as benzodiazepines and zolpidem. These drugs can indeed improve insomnia symptoms in the short term. Nevertheless, prolonged utilization of such medications may result in the development of drug dependency and a series of adverse reactions. In contrast, MSEOs, as a natural plant product, have a mild curative effect and may have fewer adverse reactions, offering a novel therapeutic approach for patients suffering from insomnia. Findings from the behavioral studies suggest that in contrast to the PCPA-treated group, the three concentrations of MSEOs treatment abbreviated the latency to sleep onset in mice, meanwhile prolonging the total sleep time, suggesting that it has an improving effect on regulating the sleep-wake cycle. This could be associated with its potential to modulate the levels of diverse neurotransmitters through the hypothalamus. Studies have shown that the abnormal regulation of neurotransmitters like DA and 5-HT in the insomnia state can cause excessive arousal reactions and disrupt the normal sleep-wake cycle [

14,

54]. 5-HT is vital for modulating mood and sleep patterns, with insufficiencies frequently correlating with anxiety and depressive disorders. GABA, as the inhibitory transmitter, helps to decrease neuronal excitability and promote the onset of sleep and the maintenance of deep sleep [

55]. Our findings indicate that, in contrast to the control group, the expression of 5HT-1A, 5HT-2A, GABAARα1, and GAD65 in the hypothalamus of mice in the model group showed decreased levels. After treatment with MSEOs-L, MSEOs-M, and MSEOs-H the levels of these neurotransmitters increased to different extents, and it could also contribute to the protection of neurons. In the MSEOs-M group, the level of the GABAARα1 subtype significantly increased, which was particularly prominent. Additionally, in the detection of several other neurotransmitters, the MSEOs-M group also demonstrated improvement effects, which corresponded with the improved results of sleep latency and total sleep duration in mice. The findings of this study further validate the role of MSEOs in effectively enhancing sleep quality through the restoration of the imbalance of neurotransmitters and the provision of neuronal protection. In particular, the medium-dose MSEOs group showed particularly significant effects in increasing the level of GABAARα1, which may be achieved by promoting the release of GABAARα1, thereby reducing the overexcited state of the central nervous system, and ultimately improving sleep quality. In summary, the application of MSEOs in regulating neurotransmitter balance has received strong experimental support. By modulating the levels of GABAARα1, GAD65, 5HT-1A, and 5HT-2A, MSEOs have demonstrated significant effects in treating insomnia in mice, comparable to DZP. As a natural product, MSEOs may possess higher safety and a lower risk of side effects and therefore hold promise as a potent natural alternative therapy for the treatment of insomnia. In the current academic literature, there is relatively scarce research on the impact of MSEOs on insomnia, and the research perspectives are rather limited, mainly focusing on exploring the effects of MSEOs on two neurotransmitters, 5HT-1A and GABAARα [

12,

13]. Based on this, this study has expanded and deepened the research, not only examining the changes of the above neurotransmitters but also further analyzing the expression levels of 5HT-2A, GAD65, and GABAARγ2. Through this comprehensive research method, we aim to more comprehensively clarify the potential role of MSEOs in alleviating insomnia symptoms in mice. The results of this study have enriched the existing research scope and provided a more solid experimental basis for the application of MSEOs in the field of insomnia treatment. Subsequent investigations are needed to validate its efficacy under different doses and time courses and explore its molecular mechanisms in depth, with the expectation of delivering more trusted treatment plans based on Chinese herbal medicine for clinical insomnia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Guofeng Shi; Methods, Guofeng Shi, Shuanghe Wang; Validation, Wenyu Cao, Xiaoyan Li; Formal analysis, Jiajing Ding; Investigation, Shanshan Luo; Resources, Zixuan Liang; Data management, Yixi Zeng; Writing and manuscript preparation, Guofeng Shi, Shuanghe Wang; Writing review and editing, Yixi Zeng, Yanqing Ma; Visualization, Yanqing Ma; Supervising, Lanyue Zhang, Hui Li; Project Management, Lanyue Zhang, Hui Li. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22408058 and 52273104), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2023A1515220145, KTP20240675).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animals in this study were from Southern Medical University (License number: SCXK (Guangdong) 2016-0041). All animal experiments were performed by the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Guangdong University of Technology (Guangzhou, China) and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Guangdong University of Technology (Guangzhou, China).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data used for the analyses in this report are available from the the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the authors for their support and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.22408058 and 52273104) and Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No.2023A1515220145, KTP20240675).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

MSEOs: Magnolia sieboldii essential oils; 5HT-1A, 5 hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) 1A; 5HT-2A, 5 hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) 2A; GAD65, Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase 65-kilodalton isoform; GABAARγ2, γ-aminobutyric Acid Type A Receptor Subunit γ2; GABAARα1, γ-Aminobutyric Acid Type A Receptor Subunit α1; GC-MS, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry.

References

- Cao Q, Jiang Y, Cui S-Y, Tu P-F, Chen Y-M, Ma X-L, et al. 2016. Tenuifolin, a saponin derived from Radix Polygalae, exhibits sleep-enhancing effects in mice. Phytomedicine. 23: 1797-1805. [CrossRef]

- Si Y, Wang L, Lan J, Li H, Guo T, Chen X, et al. 2020. Lilium davidii extract alleviates p-chlorophenylalanine-induced insomnia in rats through modification of the hypothalamic-related neurotransmitters, melatonin and homeostasis of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Pharmaceutical Biology. 58: 915-924.

- La YK, Choi YH, Chu MK, Nam JM, Choi Y-C, Kim W-J. 2020. Gender differences influence over insomnia in Korean population: A cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE. 15: e0227190.

- Ramos AR, Weng J, Wallace DM, Petrov MR, Wohlgemuth WK, Sotres-Alvarez D, et al. 2018. Sleep Patterns and Hypertension Using Actigraphy in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Chest. 153: 87-93. [CrossRef]

- Ebert B, Wafford KA, Deacon S. 2006. Treating insomnia: Current and investigational pharmacological approaches. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 112: 612-629. [CrossRef]

- Choi J-W, Lee J, Jung SJ, Shin A, Lee YJ. 2018. Use of Sedative-Hypnotics and Mortality: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 14: 1669-1677. [CrossRef]

- Zhong R-F, Shen C-Y, Hao K-X, Jiang J-G. 2024. Flavonoids from Polygoni Multiflori Caulis alleviates p-chlorophenylalanine-induced sleep disorders in mice. Industrial Crops and Products. 218: 119002.

- Cheong MJ, Kim S, Kim JS, Lee H, Lyu Y-S, Lee YR, et al. 2021. A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of the clinical effects of aroma inhalation therapy on sleep problems. Medicine. 100.

- Li X, He C, Shen M, Wang M, Zhou J, Chen D, et al. 2024. Effects of aqueous extracts and volatile oils prepared from Huaxiang Anshen decoction on p-chlorophenylalanine-induced insomnia mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 319: 117331.

- Chien L-W, Cheng SL, Liu CF. 2012. The Effect of Lavender Aromatherapy on Autonomic Nervous System in Midlife Women with Insomnia. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012: 740813.

- Wu MQ, Xu HH, Hu PY, Yue PF, Yi JF, Yang M, et al. 2022. Research progress on safety of essential oils from traditional Chinese medicine. Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs. 53: 6626-6635.

- Ai Y, Tang M, Xu X, Zhu S, Rong B, Zheng X, et al. 2023. Volatile Oil from Magnolia sieboldii Improve Neurotransmitter Disturbance and Enhance the Sleep-Promoting Effect in p-Chlorophenylalanine-Induced Sleep-Deprived Mice. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia. 33: 1303-1308. [CrossRef]

- Ai Y, Tang M, Ai Y, Song N, Ren L, Zhang Z, et al. 2023. Antidepressant-Like Effect of Aromatherapy with Magnolia sieboldii Essential Oils on Depression Mice. 17. [CrossRef]

- Dong Y-J, Jiang N-H, Zhan L-H, Teng X, Fang X, Lin M-Q, et al. 2021. Soporific effect of modified Suanzaoren Decoction on mice models of insomnia by regulating Orexin-A and HPA axis homeostasis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 143: 112141. [CrossRef]

- Bak LK, Schousboe A, Waagepetersen HS. 2006. The glutamate/GABA-glutamine cycle: aspects of transport, neurotransmitter homeostasis and ammonia transfer. Journal of Neurochemistry. 98: 641-653.

- Qiao T, Wang Y, Liang K, Zheng B, Ma J, Li F, et al. 2022. Effects of the Radix Ginseng and Semen Ziziphi Spinosae drug pair on the GLU/GABA-GLN metabolic cycle and the intestinal microflora of insomniac rats based on the brain–gut axis. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 13.

- Su-ming Z. 2008. Effects of Pioglitazone on cognition function and AGEs-RAGE system in insulin resistance in rats. Journal of Shandong University.

- Guo J, Yin X. 2016. Effects of Suanzaoren decoction on learning memory ability and neurotransmitter content in the brain of rats with senile insomnia model. Zhong Guo Yao Fang. 27: 3085-3087.

- Xia X, Yang H, Au DW-Y, Lai SP-H, Lin Y, Cho WC-S. 2022. Membrane Repairing Capability of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells Is Regulated by Drug Resistance and Epithelial-Mesenchymal-Transition. 12: 428. [CrossRef]

- Zhang R, Tian A, Zhang H, Zhou Z, Yu H, Chen L. 2011. Amelioration of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis by β-elemene Treatment is Associated with Th17 and Treg Cell Balance. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 44: 31-40. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Ma L, Liu F, Yao L, Wang W, Yang S, et al. 2023. Lavender essential oil fractions alleviate sleep disorders induced by the combination of anxiety and caffeine in mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 302: 115868. [CrossRef]

- Komiya M, Takeuchi T, Harada E. 2006. Lemon oil vapor causes an anti-stress effect via modulating the 5-HT and DA activities in mice. Behavioural Brain Research. 172: 240-249.

- Buchbauer G, Jirovetz L, Jäger W, Plank C, Dietrich H. 1993. Fragrance Compounds and Essential Oils with Sedative Effects upon Inhalation. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 82: 660-664.

- Javed H, Azimullah S, Abul Khair SB, Ojha S, Haque ME. 2016. Neuroprotective effect of nerolidol against neuroinflammation and oxidative stress induced by rotenone. BMC Neuroscience. 17: 58. [CrossRef]

- Fonsêca DV, Salgado PRR, de Carvalho FL, Salvadori MGSS, Penha ARS, Leite FC, et al. 2016. Nerolidol exhibits antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activity: involvement of the GABAergic system and proinflammatory cytokines. Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology. 30: 14-22. [CrossRef]

- Singh A, Singh L. 2024. Acyclic sesquiterpenes nerolidol and farnesol: mechanistic insights into their neuroprotective potential. Pharmacological Reports.

- Fidyt K, Fiedorowicz A, Strządała L, Szumny AJCm. 2016. β-caryophyllene and β-caryophyllene oxide—natural compounds of anticancer and analgesic properties. 5: 3007-3017. [CrossRef]

- Adams RP, González Elizondo MS, Elizondo MG, Slinkman E. 2006. DNA fingerprinting and terpenoid analysis of Juniperus blancoi var. huehuentensis (Cupressaceae), a new subalpine variety from Durango, Mexico. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 34: 205-211.

- Lucero ME, Fredrickson EL, Estell RE, Morrison AA, Richman DB. 2006. Volatile Composition of Gutierrezia sarothrae (Broom Snakeweed) as Determined by Steam Distillation and Solid Phase Microextraction. Journal of Essential Oil Research. 18: 121-125.

- Emile M. Gaydou RR, and Jean-Pierre Bianchini1. 1986. Composition of the Essential Oil of Ylang-Ylang (Cananga odorata Hook Fil. et Thomson forma genuina) from Madagascar. J. Agrie. Food Chem. 34: 481-487.

- Sabulal B, Dan M, J AJ, Kurup R, Chandrika SP, George V. 2007. Phenylbutanoid-rich rhizome oil of Zingiber neesanum from Western Ghats, southern India. Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 22: 521-524.

- Menichini F, Tundis R, Bonesi M, de Cindio B, Loizzo MR, Conforti F, et al. 2011. Chemical composition and bioactivity of Citrus medica L. cv. Diamante essential oil obtained by hydrodistillation, cold-pressing and supercritical carbon dioxide extraction. Natural Product Research. 25: 789-799.

- Pinheiro1 PF, VTdQ, VMR, , Costa3 AV, TdPM, et al. 2013. Atividade inseticida do óleo essencial de capim-citronela sobre Frankliniella schultzei e Myzus persicae.

- Sardashti AR, Valizadeh J, Adhami Y. 2012. Variation in the Essential Oil Composition of Perovskia Abrotonoides of Different Growth Stage in Baluchestan. World Applied Sciences Journal 19: 1259-1262.

- Bendiabdellah A, El Amine Dib M, Djabou N, Allali H, Tabti B, Muselli A, et al. 2012. Biological activities and volatile constituents of Daucus muricatus L. from Algeria. Chemistry Central Journal. 6: 48.

- P.Adam R. 2007. ldentification of Essential Oil Components by Gas chromatoaraphylMl. Carol Stream, pp. Ed., Allured Publishing Corporation.

- Forouzanfar F, Gholami J, Foroughnia M, Payvar B, Nemati S, Khodadadegan MA, et al. 2021. The beneficial effects of green tea on sleep deprivation-induced cognitive deficits in rats: the involvement of hippocampal antioxidant defense. Heliyon. 7: e08336. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj P, Kaur G. 2022. Acute Sleep Deprivation-Induced Anxiety and Disruption of Hypothalamic Cell Survival and Plasticity: A Mechanistic Study of Protection by Butanol Extract of Tinospora cordifolia. Neurochemical research. 47: 1692-1706. [CrossRef]

- Leng F, Edison P. 2021. Neuroinflammation and microglial activation in Alzheimer disease: where do we go from here? Nature Reviews Neurology. 17: 157-172.

- Elahee SF, Mao H-j, Zhao L, Shen X-y. 2020. Meridian system and mechanism of acupuncture action: A scientific evaluationScientific evaluation of the meridian system and the mechanism of acupuncture effect. World Journal of Acupuncture - Moxibustion. 30: 130-137.

- Brown JW, Sirlin EA, Benoit AM, Hoffman JM, Darnall RA. 2008. Activation of 5-HT1A receptors in medullary raphé disrupts sleep and decreases shivering during cooling in the conscious piglet. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 294: R884-R894.

- Watson CJ, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. 2010. Neuropharmacology of Sleep and Wakefulness. Sleep Medicine Clinics. 5: 513-528.

- Celada P, Puig MV, Amargós-Bosch M, Adell A, Artigas F. 2004. The therapeutic role of 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors in depression. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 29: 252.

- Zhao Q, Luo L, Qiao Y, Zhang J. 2022. Effects of Evodia rutaecarpa Acupoint Sticking Therapy on Rats with Insomnia Induced by Para-Chlorophenylalanine in 5-HT1Aand 5-HT2A Gene Expressions. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology. 65. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Zhao X, Mao X, Liu A, Liu Z, Li X, et al. 2014. Pharmacological evaluation of sedative and hypnotic effects of schizandrin through the modification of pentobarbital-induced sleep behaviors in mice. European Journal of Pharmacology. 744: 157-163. [CrossRef]

- Servando J, Matus M, Cortijo X, Gasca E, Violeta P, P.V S, et al. 2011. Receptor GABA A : implicaciones farmacológicas a nivel central. Archivos de Neurociencias. 16: 40-45.

- Cho S-M, Shimizu M, Lee CJ, Han D-S, Jung C-K, Jo J-H, et al. 2010. Hypnotic effects and binding studies for GABAA and 5-HT2C receptors of traditional medicinal plants used in Asia for insomnia. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 132: 225-232.

- Shen CY, Li XY, Ma PY, Li HL, Xiao B, Cai WF, et al. 2022. Nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) and NMN-rich product supplementation alleviate p-chlorophenylalanine-induced sleep disorders. Journal of Functional Foods. 91.

- Roth FC, Draguhn A. 2012. GABA Metabolism and Transport: Effects on Synaptic Efficacy. Neural Plasticity. 2012: 805830.

- He F, Yan Y, Peng M, Gao M, Zhou L, Chen F, et al. 2024. Therapeutic potential of folium extract in insomnia treatment: a comprehensive evaluation of behavioral and neurochemical effects in a PCPA-induced mouse model. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. n/a.

- Tochitani S, Kondo S. 2013. Immunoreactivity for GABA, GAD65, GAD67 and Bestrophin-1 in the Meninges and the Choroid Plexus: Implications for Non-Neuronal Sources for GABA in the Developing Mouse Brain. PLOS ONE. 8: e56901.

- Obata K, Hirono M, Kume N, Kawaguchi Y, Itohara S, Yanagawa Y. 2008. GABA and synaptic inhibition of mouse cerebellum lacking glutamate decarboxylase 67. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 370: 429-433. [CrossRef]

- Shen CY, Wan L, Zhu JJ, Jiang JG. 2020. Targets and underlying mechanisms related to the sedative and hypnotic activities of saponin extracts from semen Ziziphus jujube. Food & function. 11: 3895-3903. [CrossRef]

- Fang XS, Hao JF, Zhou HY, Zhu LX, Wang JH, Song FQ. 2010. Pharmacological studies on the sedative-hypnotic effect of Semen Ziziphi spinosae (Suanzaoren) and Radix et Rhizoma Salviae miltiorrhizae (Danshen) extracts and the synergistic effect of their combinations. Phytomedicine. 17: 75-80. [CrossRef]

- Mayer G, Happe S, Evers S, Hermann W, Jansen S, Kallweit U, et al. 2021. Insomnia in neurological diseases. Neurological research and practice. 3: 15.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the experiment.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the experiment.

Figure 2.

Test flow chart.

Figure 2.

Test flow chart.

Figure 3.

Impact of MSEOs on latency to sleep onset and total sleep duration in mice with PCPA-induced insomnia. (A) Comparison of sleep latency between different groups of mice. (B) Comparison of sleep duration between different groups. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 highlight notable distinctions from the PCPA-treated model group. MSEOs-L, MSEOs-M, and MSEOs-H represent dosages of 25 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg, and 100 mg/kg, respectively.) Data showed mean ± SD (n = 4).

Figure 3.

Impact of MSEOs on latency to sleep onset and total sleep duration in mice with PCPA-induced insomnia. (A) Comparison of sleep latency between different groups of mice. (B) Comparison of sleep duration between different groups. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 highlight notable distinctions from the PCPA-treated model group. MSEOs-L, MSEOs-M, and MSEOs-H represent dosages of 25 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg, and 100 mg/kg, respectively.) Data showed mean ± SD (n = 4).

Figure 4.

A comparative analysis of neuronal quantities across various brain tissues. (A) Nissl’s staining. (B) Quantity of uninjured neurons in each region of mouse brain tissue. (**p < 0.01 highlight notable distinctions from the PCPA-treated model group. MSEOs-L, MSEOs-M, and MSEOs-H represent dosages of 25 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg, and 100 mg/kg, respectively.) Data showed mean ± SD (n = 4).

Figure 4.

A comparative analysis of neuronal quantities across various brain tissues. (A) Nissl’s staining. (B) Quantity of uninjured neurons in each region of mouse brain tissue. (**p < 0.01 highlight notable distinctions from the PCPA-treated model group. MSEOs-L, MSEOs-M, and MSEOs-H represent dosages of 25 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg, and 100 mg/kg, respectively.) Data showed mean ± SD (n = 4).

Figure 5.

Expression of 5HT-1A protein. (A)Image of immunofluorescently labeled 5HT-1A protein; (B) Quantitative assessment of 5HT-1A expression in various mouse brain regions. (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 highlight notable distinctions from the PCPA-treated model group. MSEOs-L, MSEOs-M, and MSEOs-H represent dosages of 25 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg, and 100 mg/kg, respectively.) Data showed mean ± SD (n = 4).

Figure 5.

Expression of 5HT-1A protein. (A)Image of immunofluorescently labeled 5HT-1A protein; (B) Quantitative assessment of 5HT-1A expression in various mouse brain regions. (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 highlight notable distinctions from the PCPA-treated model group. MSEOs-L, MSEOs-M, and MSEOs-H represent dosages of 25 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg, and 100 mg/kg, respectively.) Data showed mean ± SD (n = 4).

Figure 6.

Expression of 5HT-2A protein. (A) Image of immunofluorescently labeled 5HT-2A protein; (B) Quantitative assessment of 5HT-2A expression in various mouse brain regions. (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01and *p<0.05 highlight notable distinctions from the PCPA-induced model group. MSEOs-L, MSEOs-M, and MSEOs-H represent dosages of 25 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg, and 100 mg/kg, respectively.) Data showed mean ± SD (n = 4).

Figure 6.

Expression of 5HT-2A protein. (A) Image of immunofluorescently labeled 5HT-2A protein; (B) Quantitative assessment of 5HT-2A expression in various mouse brain regions. (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01and *p<0.05 highlight notable distinctions from the PCPA-induced model group. MSEOs-L, MSEOs-M, and MSEOs-H represent dosages of 25 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg, and 100 mg/kg, respectively.) Data showed mean ± SD (n = 4).

Figure 7.

Expression of GABAARɑ1 protein. (A) Images of GABAARα1 protein staining in various regions of mouse brain tissue; (B) Quantitative assessment of GABAARα1 proteins in various brain tissues. (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 highlight notable distinctions from the PCPA-induced model group. MSEOs-L, MSEOs-M, and MSEOs-H represent dosages of 25 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg, and 100 mg/kg, respectively.) Data showed mean ± SD (n = 4).

Figure 7.

Expression of GABAARɑ1 protein. (A) Images of GABAARα1 protein staining in various regions of mouse brain tissue; (B) Quantitative assessment of GABAARα1 proteins in various brain tissues. (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 highlight notable distinctions from the PCPA-induced model group. MSEOs-L, MSEOs-M, and MSEOs-H represent dosages of 25 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg, and 100 mg/kg, respectively.) Data showed mean ± SD (n = 4).

Figure 8.

Expression of GAD65 antibody. (A) Images of GAD65 protein staining in various regions of mouse brain tissue; (B) The combined optical density across various brain tissue sections was assessed. (*p < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 highlights notable distinctions from the PCPA-induced model group. MSEOs-L, MSEOs-M, and MSEOs-H represent dosages of 25 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg, and 100 mg/kg, respectively.) Data showed mean ± SD (n = 4).

Figure 8.

Expression of GAD65 antibody. (A) Images of GAD65 protein staining in various regions of mouse brain tissue; (B) The combined optical density across various brain tissue sections was assessed. (*p < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 highlights notable distinctions from the PCPA-induced model group. MSEOs-L, MSEOs-M, and MSEOs-H represent dosages of 25 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg, and 100 mg/kg, respectively.) Data showed mean ± SD (n = 4).

Figure 9.

The comparative expression levels of mRNA for GABAARα1, GABAARγ2, 5HT-2A, and 5HT-1A. (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 highlight notable distinctions from the PCPA-induced model group. MSEOs-L, MSEOs-M, and MSEOs-H represent dosages of 25 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg, and 100 mg/kg, respectively.) Data showed mean ± SD (n = 4).

Figure 9.

The comparative expression levels of mRNA for GABAARα1, GABAARγ2, 5HT-2A, and 5HT-1A. (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 highlight notable distinctions from the PCPA-induced model group. MSEOs-L, MSEOs-M, and MSEOs-H represent dosages of 25 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg, and 100 mg/kg, respectively.) Data showed mean ± SD (n = 4).

Table 1.

The name, voucher specimen number, and storage location of the plant sample.

Table 1.

The name, voucher specimen number, and storage location of the plant sample.

| Latin name |

Local name |

Voucher number |

Collection time |

Storage location |

| Magnolia sieboldii |

Tiannvmulan |

2020-112A |

2020.09 |

Institute of Natural Medicine & Green Chemistry, School of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Guangdong University of Technology |

Table 2.

Primer sequences information.

Table 2.

Primer sequences information.

| Genes |

Forward (5′-3′) |

Reverse (3′-5′) |

| 5HT-1A |

CCAACTATCTCATCGGCTCCTT |

CTGACCCAGAGTCCACTTGTTG |

| 5HT-2A |

TATGCTGCTGGGTTTCCTTGT |

GTTGAAGCGGCTATGGTGAAT |

| GABAARα1 |

ATGACAGTGCTCCGGCTAAAC |

AGTGCATTGGGCATTCAGCT |

| GABAARγ2 |

GCAGTTCTGTTGAAGTGGGTGA |

GCAGGGAATGTAAGTCTGGATGG |

Table 3.

relative content (%) and Retention index (RI) of each compound identified from Magnolia sieboldii essential oils.

Table 3.

relative content (%) and Retention index (RI) of each compound identified from Magnolia sieboldii essential oils.

| No |

Compounds1

|

RI2

|

Exp RI3

|

Ref 4

|

Relative content (%) |

| Magnolia sieboldii |

| 1 |

β-pinene |

861 |

980 |

A |

0.13 |

| 2 |

α-terpinene |

877 |

1018 |

C |

0.87 |

| 3 |

(Z)-β-ocimene |

895 |

1041 |

B |

14.87 |

| 4 |

γ-terpinene |

941 |

1062 |

C |

1.72 |

| 5 |

2-Carene |

959 |

1002 |

D |

0.61 |

| 6 |

fenchone |

966 |

- |

- |

0.17 |

| 7 |

Linalool |

971 |

1096 |

D |

0.8 |

| 8 |

2,6-Dimethyl-2,4,6-octatriene |

984 |

1131 |

E |

2.91 |

| 9 |

(±)-Camphor |

1025 |

- |

- |

0.12 |

| 10 |

Terpinine-4-ol |

1051 |

1177 |

D |

2.99 |

| 11 |

1-(3-methylenecyclopentyl)-Ethanone |

1110 |

- |

- |

0.1 |

| 12 |

Citronellol |

1132 |

1223 |

D |

0.28 |

| 13 |

CIS-3-NONEN-1-OL |

1171 |

1157 |

D |

0.2 |

| 14 |

Decan-1-ol |

1184 |

1266 |

D |

0.16 |

| 15 |

O-Benzyllinalool |

1205 |

- |

- |

0.11 |

| 16 |

delta-elemene |

1246 |

1338 |

D |

0.25 |

| 17 |

α-Terpinyl acetate |

1262 |

1349 |

D |

0.1 |

| 18 |

dl-Citronellol acetate |

1264 |

1352 |

D |

0.5 |

| 19 |

α-Copaene |

1278 |

1376 |

D |

0.3 |

| 20 |

β-elemene |

1293 |

1390 |

D |

19.94 |

| 21 |

isocaryophyllene |

1307 |

1408 |

D |

3.63 |

| 22 |

β-cubebene |

1313 |

1388 |

D |

0.22 |

| 23 |

α-guaiene |

1333 |

- |

- |

0.76 |

| 24 |

alloaromadendrene |

1341 |

1460 |

D |

0.13 |

| 25 |

α-caryophyllene |

1345 |

1454 |

D |

1.84 |

| 26 |

(E)-β-Farnesene |

1349 |

1456 |

D |

1.43 |

| 27 |

valencene |

1353 |

- |

- |

0.22 |

| 28 |

trans-Caryophyllene |

1357 |

1419 |

D |

0.1 |

| 29 |

β-chamigrene |

1362 |

1477 |

D |

0.57 |

| 30 |

Germacrene D |

1366 |

1481 |

D |

7.05 |

| 31 |

α-Curcumene |

1372 |

1483 |

F |

0.76 |

| 32 |

α-bergamotene |

1380 |

1403 |

F |

3.49 |

| 33 |

α-muurolene |

1384 |

1500 |

H |

0.69 |

| 34 |

β-Bisabolene |

1390 |

1505 |

D |

1.15 |

| 35 |

Muurolene |

1395 |

1479 |

D |

0.45 |

| 36 |

β-cadinene |

1398 |

1513 |

H |

2.84 |

| 37 |

α-selinene |

1429 |

1498 |

D |

0.58 |

| 38 |

cis-(+)Nerolidol |

1434 |

1525 |

J |

4.51 |

| 39 |

(-)-β-Bourbonene |

1443 |

1388 |

D |

0.83 |

| 40 |

Caryophyllene oxide |

1447 |

1583 |

D |

0.39 |

| 41 |

α-patchoulene |

1454 |

1456 |

D |

0.5 |

| 42 |

4,7,7-trimethyl-3-phenylbicyclo [2.2.1]heptan-3-ol |

1459 |

- |

- |

0.1 |

| 43 |

juniper camphor |

1474 |

1700 |

D |

0.32 |

| 44 |

α-bulnesene |

1482 |

1509 |

D |

1.3 |

| 45 |

α-muurolol |

1487 |

1646 |

D |

0.17 |

| 46 |

T-cadinol |

1490 |

1663 |

I |

0.55 |

| 47 |

(+)-Viridiflorol |

1492 |

1592 |

D |

0.83 |

| 48 |

δ-Cardinol |

1495 |

1644 |

D |

0.21 |

| 49 |

α-Cadinol |

1495 |

1653 |

C |

2.07 |

| 50 |

Eicosapentaenoic Acid methyl ester |

1497 |

- |

- |

2.26 |

| 51 |

(-)-spathulenol |

1505 |

- |

- |

0.29 |

| 52 |

Spathulenol |

1512 |

1578 |

E |

0.43 |

| 53 |

Isovellerdiol |

1515 |

- |

- |

0.11 |

| 54 |

Andrographolide |

1536 |

- |

- |

0.4 |

| 55 |

cembrene |

1543 |

1938 |

D |

0.2 |

| 56 |

1-Heptatriacotanol |

1547 |

- |

- |

0.43 |

| 57 |

dl-Perillaldehyde |

1550 |

1271 |

D |

0.1 |

| 58 |

p-Menth-8-en-2-ol acetate |

1557 |

- |

- |

0.1 |

| 59 |

artemisia triene |

1571 |

- |

- |

0.1 |

| 60 |

9,10-Dibromo-(+)-camphor |

1581 |

- |

- |

0.13 |

| 61 |

safranal |

1599 |

1196 |

D |

2.71 |

| 62 |

α-santalol |

1616 |

1675 |

E |

0.95 |

| 63 |

Kaur-16-en-18-yl acetate |

1647 |

- |

- |

0.39 |

| 64 |

1,5,5-trimethyl-6-methylidenecyclohexene |

1683 |

- |

- |

0.63 |

| 65 |

3,3,6,6-Tetramethyl-1,4-cyclohexadiene |

1700 |

- |

- |

0.67 |

| 66 |

cyclopentadeca-1,8-diyne |

1711 |

- |

- |

0.5 |

| 67 |

Shizukanolide |

1717 |

- |

- |

0.11 |

| 68 |

Oxacyclotetradeca-4-11-diyne |

1730 |

- |

- |

0.1 |

| 69 |

(1R,2R)-2-methyl-1-(4-methylphenyl)but-3-en-1-ol |

1737 |

- |

- |

0.28 |

| |

Total identified/% |

|

|

|

95.71 |

| |

Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons/% |

|

|

|

60.47 |

| |

Oxygenated sesquiterpenes/% |

|

|

|

10.94 |

| |

Total monoterpenoids/% |

|

|

|

29.36 |

| |

Oxygenated monoterpenes/% |

|

|

|

6.85 |

| |

Others/% |

|

|

|

5.61 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).