1. Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDs) are a heterogeneous group of diseases characterised by progressive loss of neurons, many of them associated with accumulation of misfolded protein and protein aggregates [

1]. Developing an effective treatment for NDs is currently a great challenge in medicine, given their increasing prevalence, in association with longer life expectancies [

2]. Despite extensive research in the field, these highly debilitating diseases remain incurable, necessitating urgent novel therapeutic strategies. Edible plants traditionally used in Asian cuisines are also often used in Traditional Medicines and have garnered increasing attention as functional foods, as they often contain bioactive compounds that may confer health benefits beyond basic nutrition. Owing to their chemical diversity and complexity, plant-derived products emerge as a very interesting source for novel bioactive compounds. [

3]. Several studies using

in vitro and

in vivo models of NDs have demonstrated the ability of plant-based products to successfully target pathological events associated with NDs, namely by reducing the abnormal accumulation of disease-specific misfolded and aggregated proteins (Reviewed in Tyler & Tyler, 2023). Among the complex pathology of these diseases, oxidative stress is another hallmark frequently modulated by treatments derived from plants, as we previously demonstrated for

Hyptis spp. extracts and Rapeseed Pomace, a waste product from edible oil production from

Brassica napus [

4,

5].

Hemerocallis citrina Baroni is a herbaceous perennial plant from the Liliaceae family, native to East Asia, commonly known as the "daylily flower" or "yellow flower vegetable", and with widespread use in Asian cuisine. It is also listed in the "Compendium of Materia Medica" for its bioactive properties, historically used for its sedative, sleep promoting, and febrifuge activities [

6]. Its flowers, the edible part of the plant, are rich in flavonoids, namely rutin and phenylpropanoids, such as quinic acid esters, especially those conjugated with caffeic, p-hydroxycinnamic and ferulic acid and their glucosides [

7]. Several studies have been conducted on the pharmacological potential of

H. citrina Baroni, with promising results.

H. citrina Baroni extracts prevented injury induced by glutamate and corticosterone, and increased serotonin release in PC12 cells [

8].

In vivo studies showed an antidepressant-like effect on rodents, mainly with an impact on the monoaminergic system, elevating serotonin, noradrenaline, and dopamine levels [

6]. In previous studies with and mouse models of Machado-Joseph disease (MJD) or Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3), – recognized as the most common autosomal-dominant form of genetic ataxia worldwide - it was demonstrated that modifying the serotonergic signalling pathways led to improvements in key aspects of this ND, namely reducing mutant protein aggregation [

9,

10]. When taken together, these findings suggested that

H. citrina Baroni may have therapeutic potential for MJD/SCA3 and other NDs, being an attractive object for further investigation.

In this work, taking advantage of the , we aimed to explore the therapeutic potential of

H. citrina Baroni flower extracts in genetic models of MJD/SCA3 – a genetic inherited spinocerebellar ataxia caused by an abnormal expansion of a CAG in

ATXN3 gene - and of Frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism associated with chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) – a genetically determined form of dementia caused by mutation in the microtubule associated protein tau (

MAPT) gene [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Additionally, using genetic tools and reporter strains, we expect to dissect the mechanism(s) driving the beneficial effect of these extracts.

2. Results

2.1. H. citrina Baroni ethanolic extracts ameliorate motor deficits in the model of MJD/SCA3, independently of effects on mATXN3 neuronal aggregation

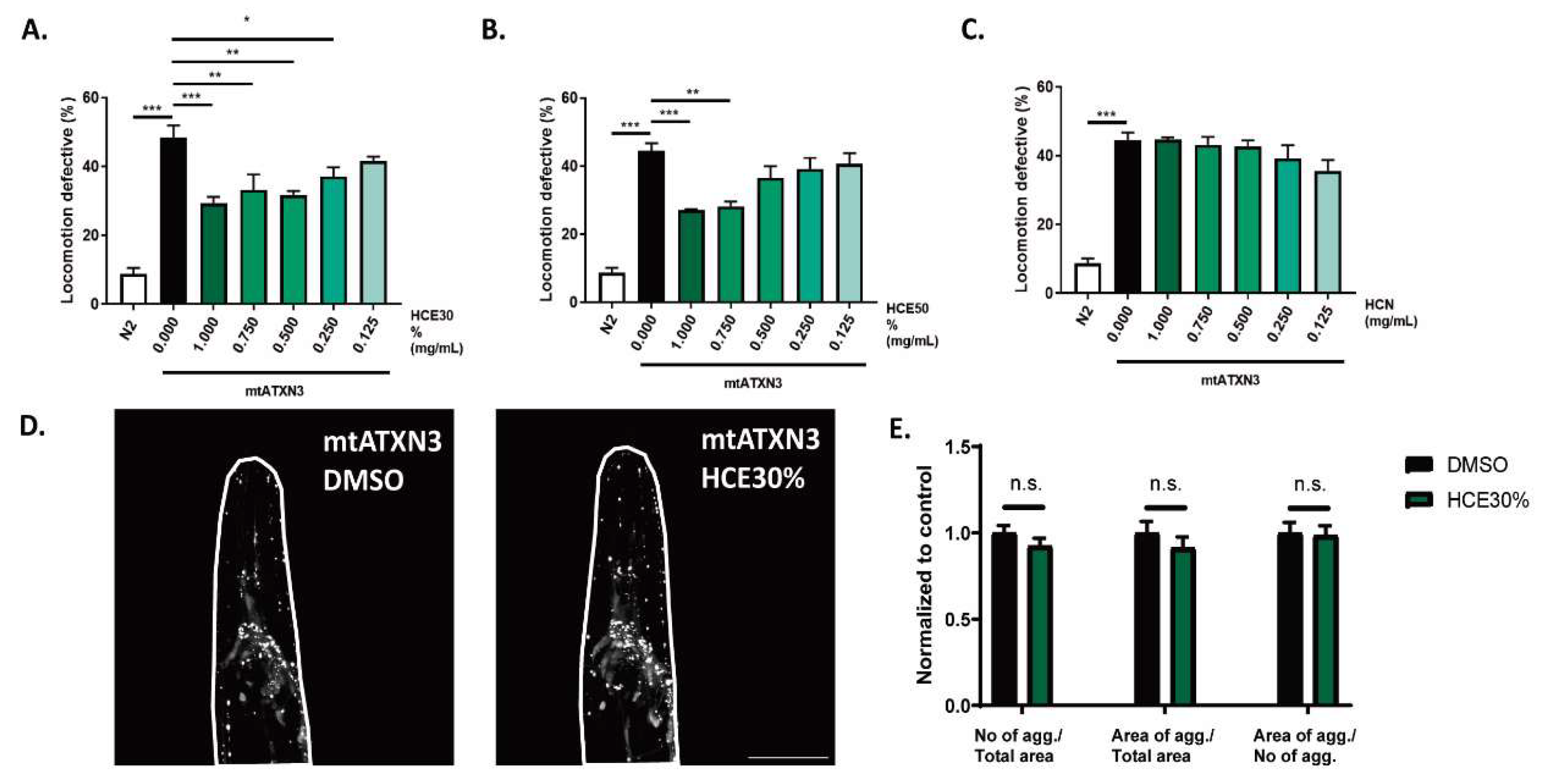

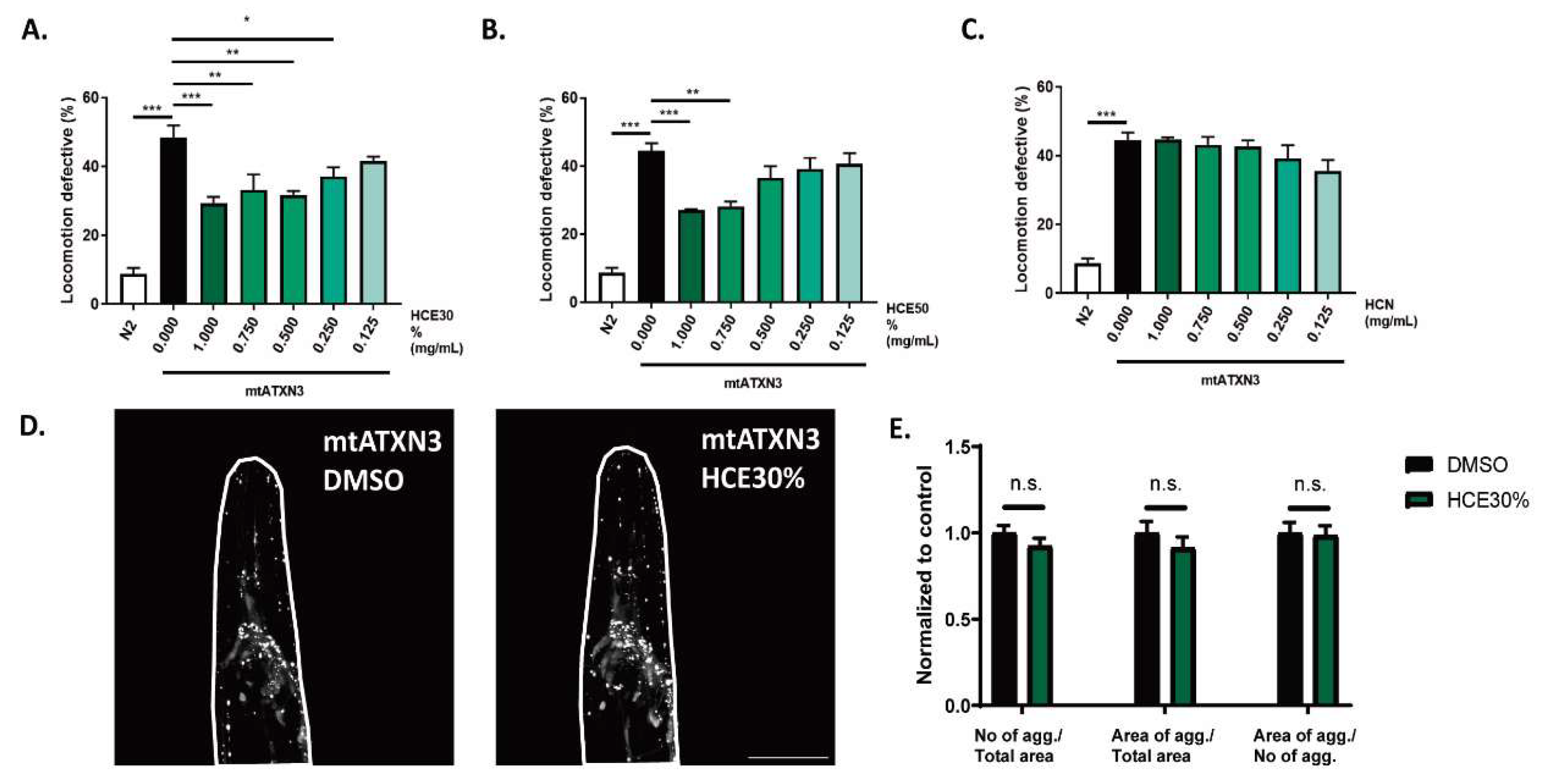

Treatment with both HCE extracts did not present any toxicity (Sup. Fig. 1). HCE50% treatment resulted in improvement of the MJD/SCA3 model´s motility at the highest concentrations (1mg/mL and 0.75 mg/mL) while HCE30% was effective down to 0.25 mg/mL, suggesting a higher potency and a broader therapeutic window. HCN did not have any effect on the model’s motility (

Figure 1 A.-C.).

One hallmark of MJD is the formation of mtATXN3 aggregates within specific regions of patients’ brains. This pathological aspect of the disease is also present in the

C. elegans model and can be quantified. Treatment with HCE30% at 1 mg/mL did not alter mutant ATXN3 aggregation dynamics in the model, at the onset of adulthood. Confocal imaging showed that treated animals did not have a different number of neuronal mtATXN3 aggregates per total head area, nor a distinct area occupied by the aggregates. The size of the aggregates was also not affected (

Figure 1 D.-E.).

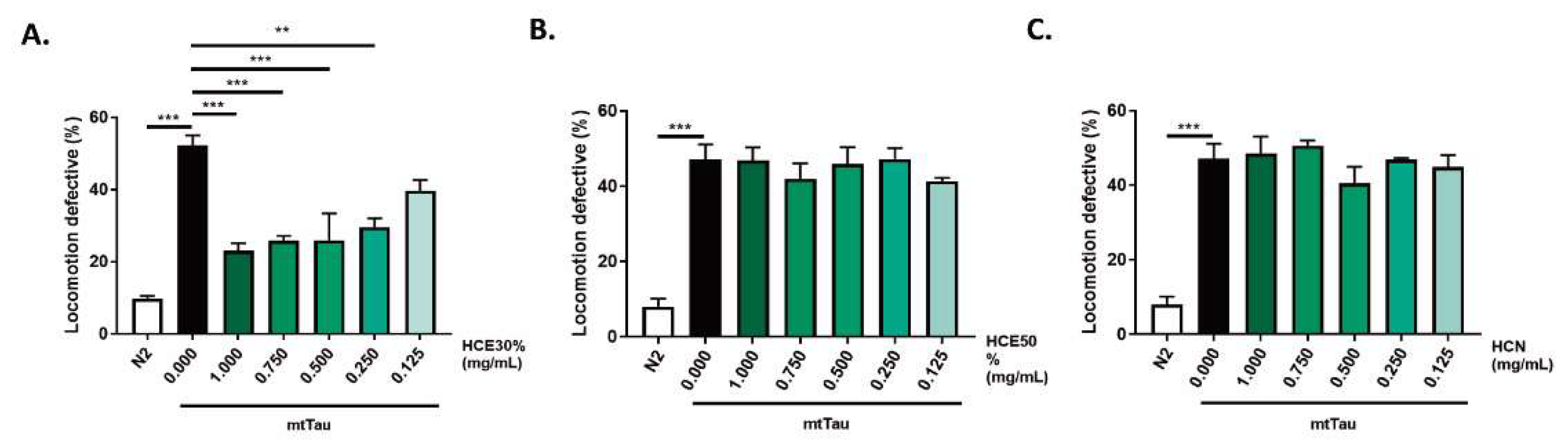

2.2. H. citrina Baroni ethanolic extract ameliorates motor deficits in a model of FTDP-17

To assess the potential therapeutic benefits of

H. citrina Baroni extracts for other neurodegenerative disease, a

C. elegans FTDP-17 model, expressing a mutant (V337M) Tau protein (V337M, here designated mtTau) was chronically treated with the three

H. citrina Baroni extracts (

Figure 2a-c) (Kraemer, B.C. et al., 2003). HCE30% treatment was the only condition to significantly reduce locomotion deficits of the model, in a dose-dependent manner. The comparison between animals treated with HCE30% and DMSO1% revealed a significantly improved motor phenotype of HCE30% treated animals with 1.000 mg/mL; 0.750 mg/mL; 0.500 mg/mL and 0.250 mg/mL. Due to their broader therapeutic potential in two distinct neurodegenerative conditions, HCE30% (hereinafter referred to as HCE) was further studied, and all experiments were performed at a dosage of 1.000 mg/mL.

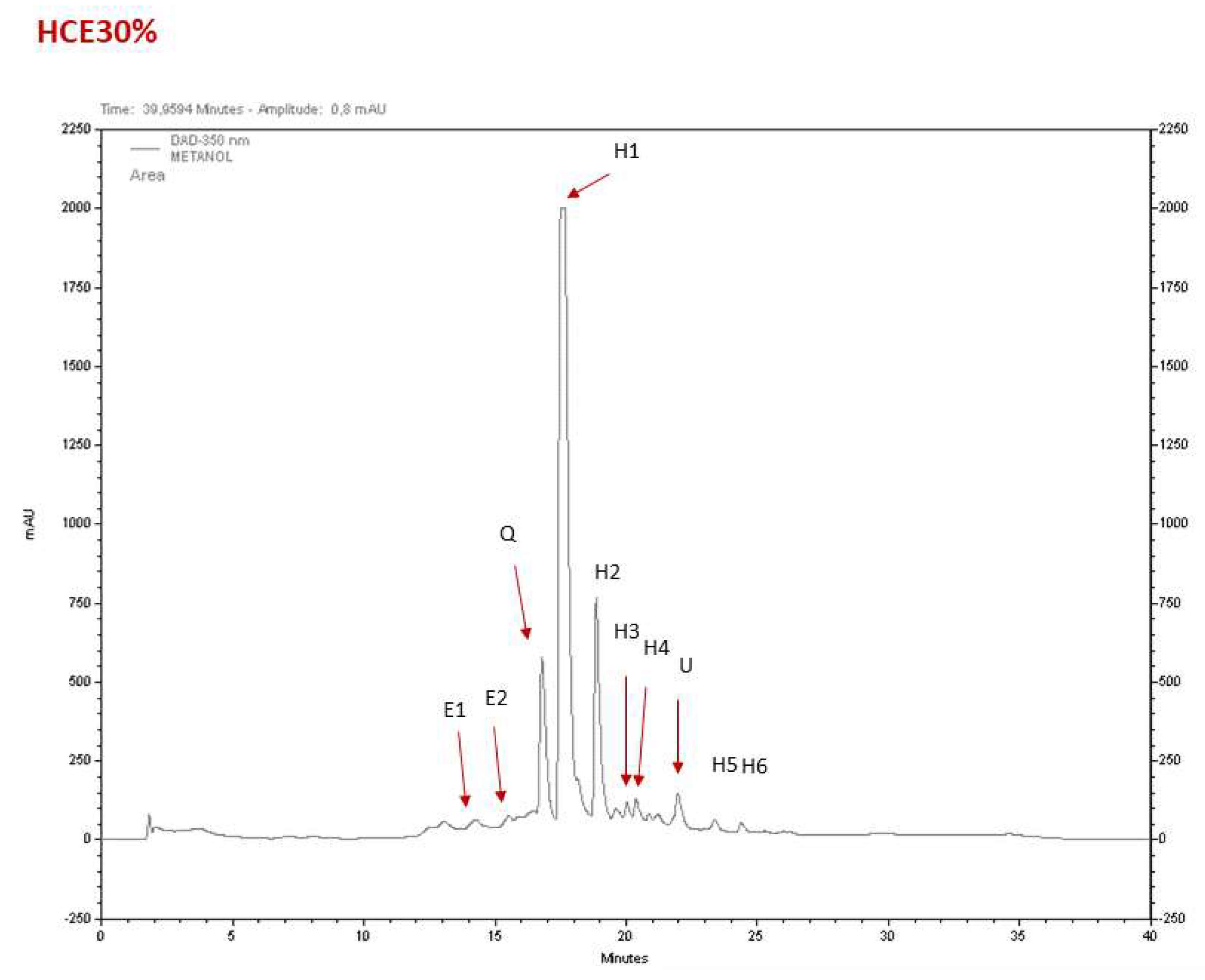

2.3. Phytochemical composition of the extracts.

The major constituents of the

H. citrina Baroni extracts (HCE) were hydroxycinnamic acids and flavonoids, based on their characteristic UV spectrum profile (Lima, M.R.M. et al., 2017). HCE30% was the fraction that showed more relevant pharmacological activities. A typical chromatogram of HCE30% is shown in

Figure 3, and the identification and quantification of the compounds is indicated in

Supplementary Table 1. Its composition is basically constituted by hydroxycinnamic acids (up to 70%), with minor amounts of epicatechins, and a quercetin glucoside derivative. This HPLC profile and composition is similar to that previously reported with another HCE extract used before (Tian, H. et al., 2017).

2.4. HCE effect was dependent on serotonergic but not dopaminergic signalling in the MJD/SCA3 model

Other

H. citrina Baroni extracts have been shown to modulate serotonergic and dopaminergic systems in rodent models (Du, B. et al., 2014; Gu, L. et al., 2012). Similarly, our team has previously demonstrated the modulation of serotonergic system by citalopram or of both serotonergic and dopaminergic systems by aripiprazole chronic treatments, ameliorating the motor dysfunction in the mtATXN3-expressing

C. elegans model. (Costa, M. do C. et al., 2016; Jalles, A. et al., 2022; Teixeira-Castro, A. et al., 2015). Therefore, we examined whether the dopaminergic and serotoninergic systems in C. elegans were necessary for the previously described beneficial impact of HCE, by ablating their main receptors in the mtATXN3 genetic background (

Figure 4 A)

Ablation of both DOP-1 (D1-like) and DOP-3 (D2-like) receptors did not affect HCE’s effect on locomotion of mtATXN3 expressing worms (

Figure 4 B. and C.). In contrast, ablation of the serotonin receptors SER-1 (5-HT2A like) (p = 1.000), SER-5 (5-HT6 like) (p = 0.774) or SER-7 (5-HT7 like) (p = 0.999) receptors, led to a complete loss of HCE effect (

Figure 4 D., E. and F.), indicating that serotonergic, but not dopaminergic, signaling is necessary for HCE efficacy.

As several post-synaptic serotonin receptors were necessary for HCE effect in the MJD/SCA3 model, we hypothesized that HCE might be increasing the availability of serotonin in the synaptic cleft. Therefore, we evaluated the HCE action dependency on the SER-4 (5-HT1A like) receptor, and on MOD-5 (SERT like) transporter, involved in the reuptake of serotonin from the synaptic cleft (Olde, B., McCombie, W.R., 1997; Ranganathan, R. et al., 2001; Teixeira-Castro, A. et al., 2015). Both proteins are involved in negative feedback mechanisms to reduce the amounts of serotonin available in the synaptic cleft. As we previously demonstrated, ablation of SER-4 or MOD-5 per se significantly improves the motor behaviour of the MJD/SCA3 model (Teixeira-Castro, A. et al., 2015). Interestingly, HCE chronic treatment in the MJD/SCA3 model, knockout for the SER-4 autoreceptor or for the MOD-5 transporter, did not have and additive beneficial effect, as observed with estrone treatment. Estrone improves the model’s motor phenotype, independently from the serotonergic system (Teixeira-Castro, A. et al., 2015) (

Figure 4 G. and H.). Overall, these findings suggest that the effect of HCE treatment in the

C. elegans model of MJD/SCA3 is dependent from a broad action of the extract on the serotonergic system, possibly increasing serotonin availability.

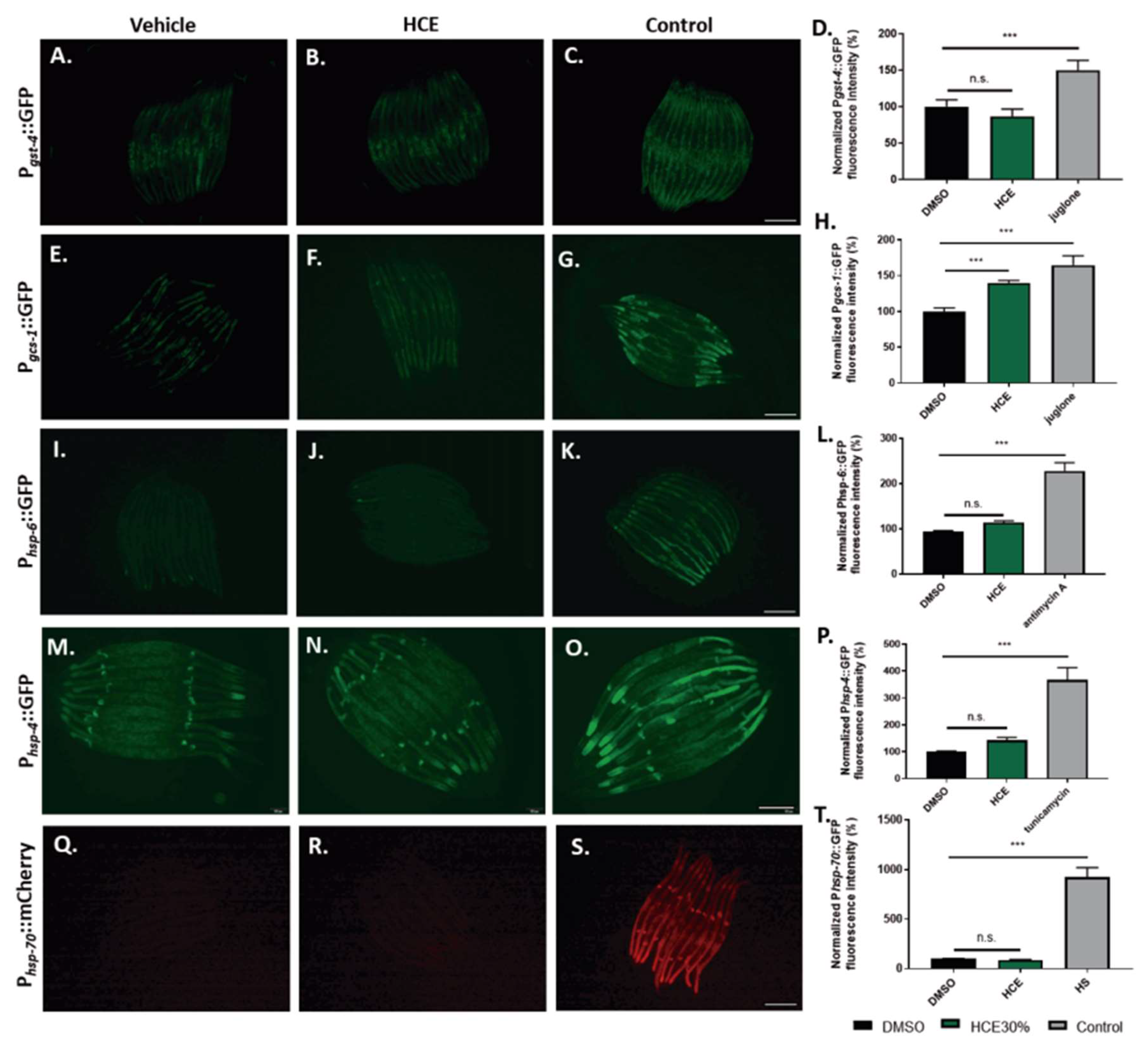

2.5. HCE treatment promotes HLH-30/TFEB nuclear translocation

To gain mechanistic insight into the action of the extract on several endogenous cellular stress responses,

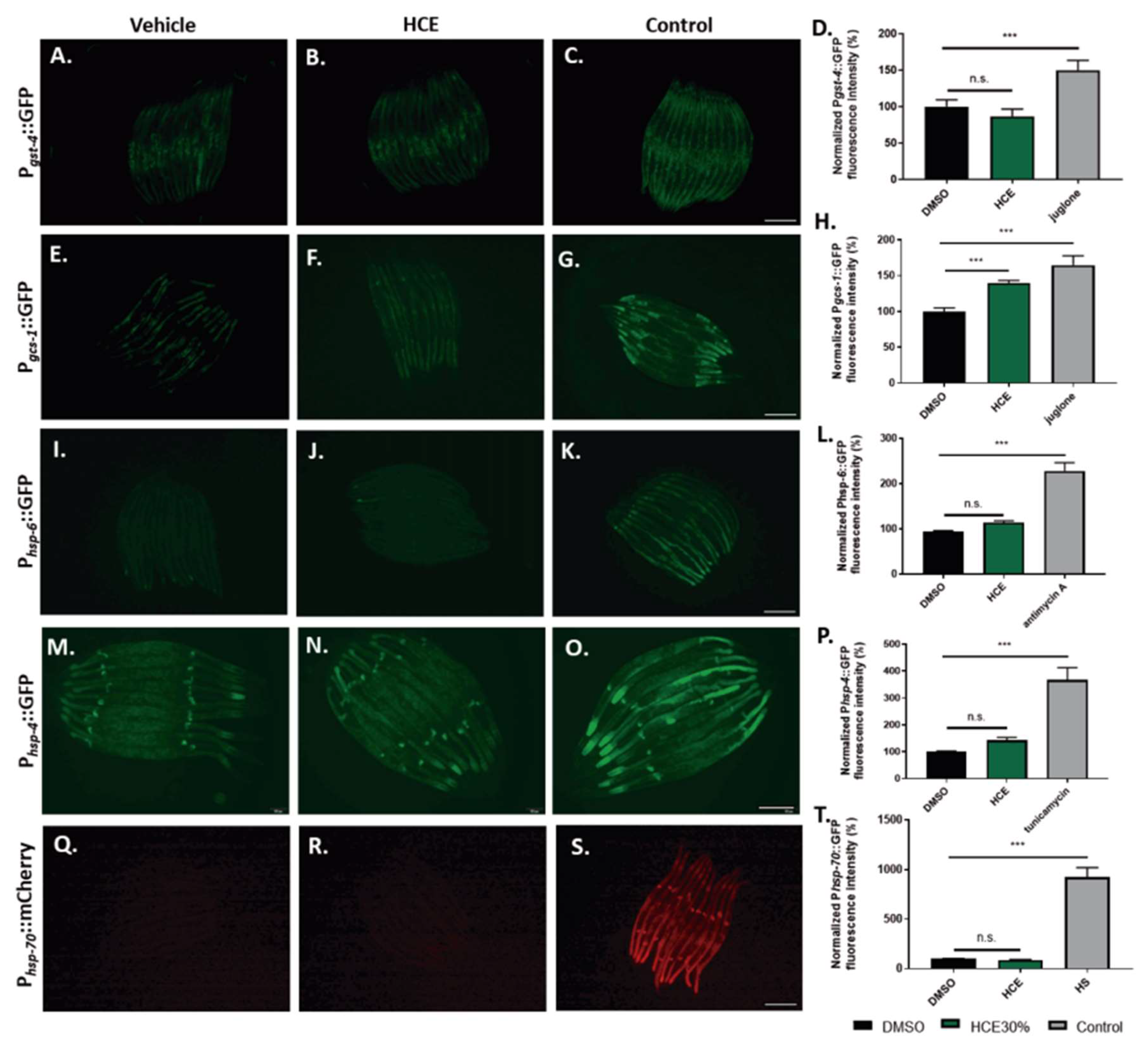

C. elegans transcriptional reporter strains were used to quantify the stress-response activation upon HCE treatment. We investigated the effect of HCE treatment on the expression of antioxidant-related genes, namely of the gst-4 and gcs-1 genes, encoding, respectively, the drug-metabolizing enzyme glutathione S-transferase 4 (GST-4), and the Phase-II detoxification enzyme gamma-glutamyl cysteine synthetase (GCS-1), both involved in the glutathione cycle. When chronically treated with HCE extract, no impact was observed regarding the promoter activity of gst-4 (

Figure 5 A.-D.), while the gcs-1 transcriptional reporter strain showed a mild increase of GFP fluorescence compared to the untreated control (

Figure 5 E.-H.) However, the fluorescence pattern observed did not match the one seen for the positive control (acute juglone treatment), raising doubts on the biological significance of this result.

To investigate the hypothesis of HCE acting by the modulation of protein folding and homeostasis, we used transcriptional reporter strains for the Unfolded Mitochondrial Protein Response (UPRmt):Phsp-6::GFP (

Figure 5 I.-J.)., for the Unfolded Protein Response of the endoplasmic reticulum (UPRER): Phsp-4::GFP (

Figure 5 M.-P.), and for the Heat Shock Response (HSR): Phsp-70::mCherry (

Figure 5 J.-T.). Our results showed that HCE treatment had no impact on the activity of any the promoters.

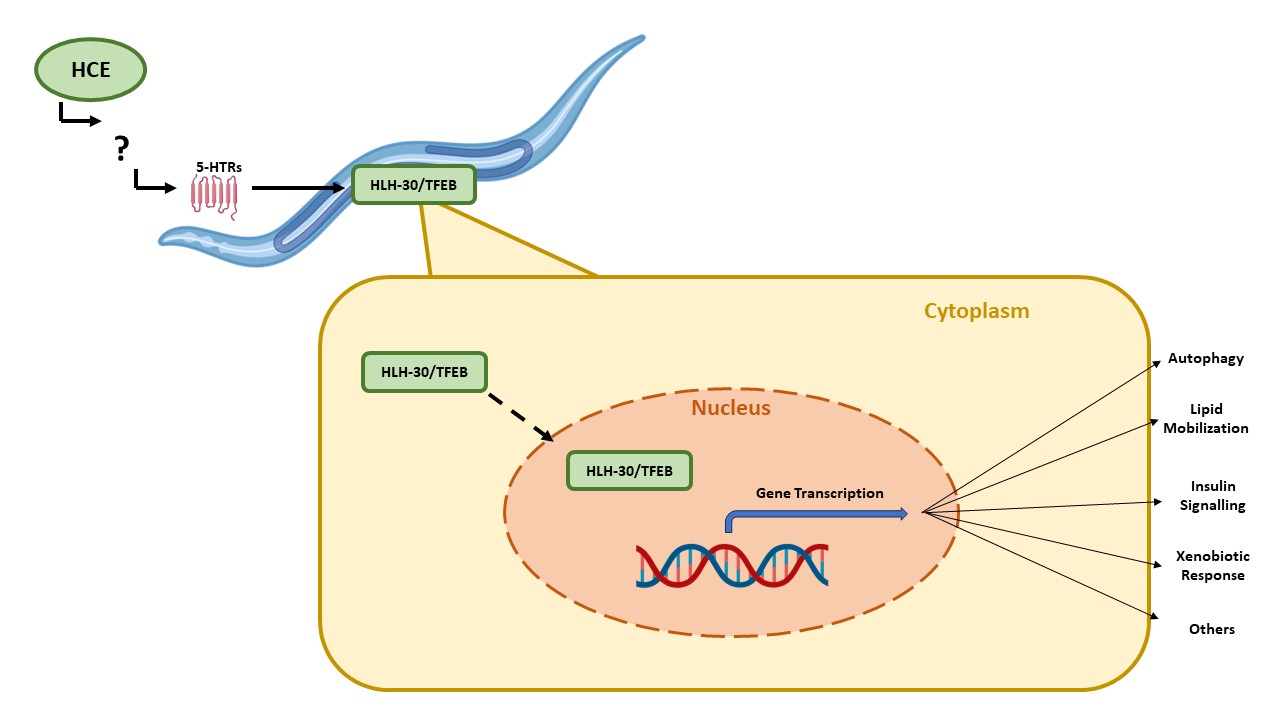

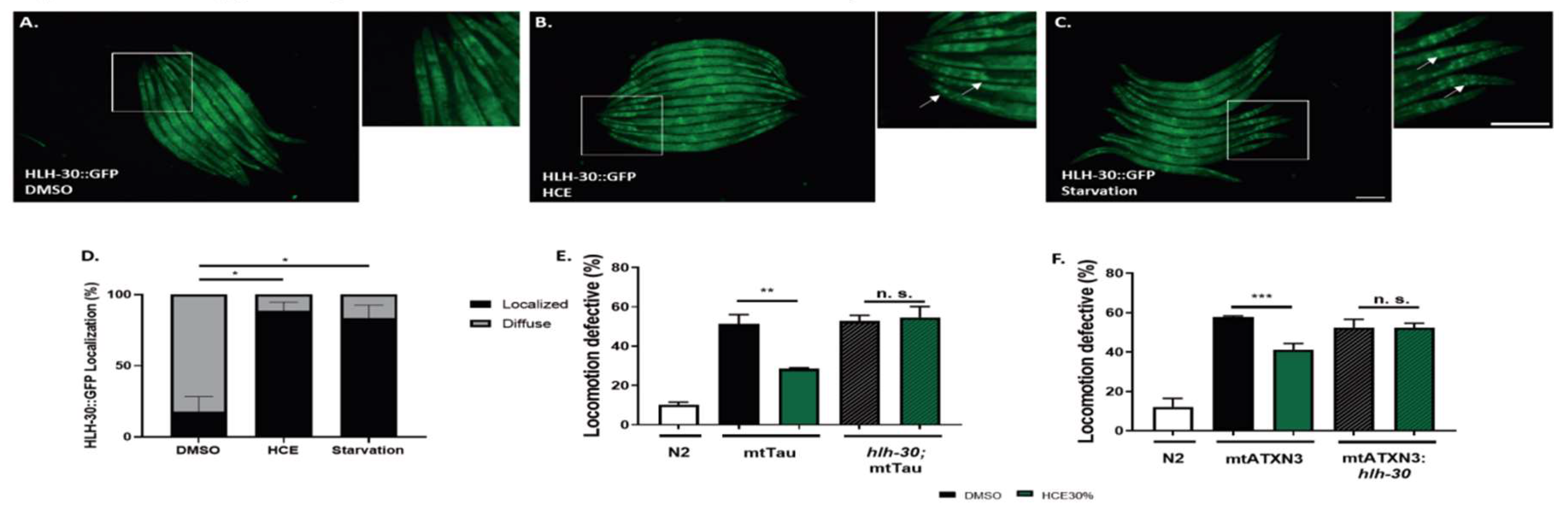

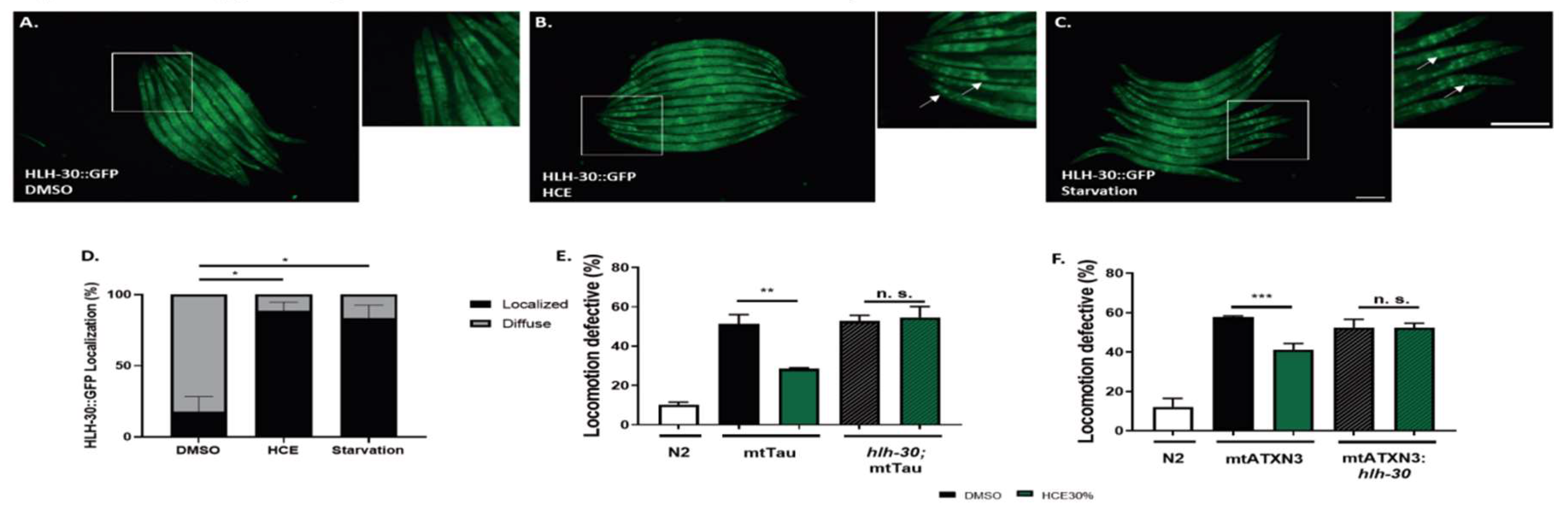

We also assessed the ability of HCE to activate the HLH-30, the nematode orthologue of TFEB, a mammalian transcription factor that regulates the expression of several autophagy-related genes, among others (Lapierre, L.R. et al., 2013). When activated, HLH-30 is translocated from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, where it promotes the transcription of autophagy related genes, such as atg-18, lgg-1 and sqst-1; components of the insulin signaling pathway as ins-11, sgk-1 and dct-1, which are known longevity regulators; host-defense signaling pathways, namely kgb-1, nsy-1 and mdl-1; genes with antimicrobial activity such as those encoding C-type lectins, antimicrobial peptides, and ferritin, as well as detoxifying enzymes such as fmo-2 (Lapierre, L.R. et al., 2013; Leiser, S.F. et al., 2015; Visvikis, O. et al., 2014). Notably, with HCE treatment, we observed an induction of HLH-30::GFP nuclear translocation, similar to animals in starvation conditions (

Figure 6a-d).This suggests that HCE treatment is inducing HLH-30/TFEB dependent responses in the nematode.

We next sought to explore whether the beneficial effect of HCE in the FTDP-17 and MJD/SCA3

C. elegans models was dependent on the presence of HLH-30. Upon ablation of HLH-30, HCE treatment lost the beneficial effect in the mtATXN3 (

Figure 6e) and mtTau genetic backgrounds (

Figure 6f), suggesting that HLH-30 is indeed necessary for the effect of this herbal extract.

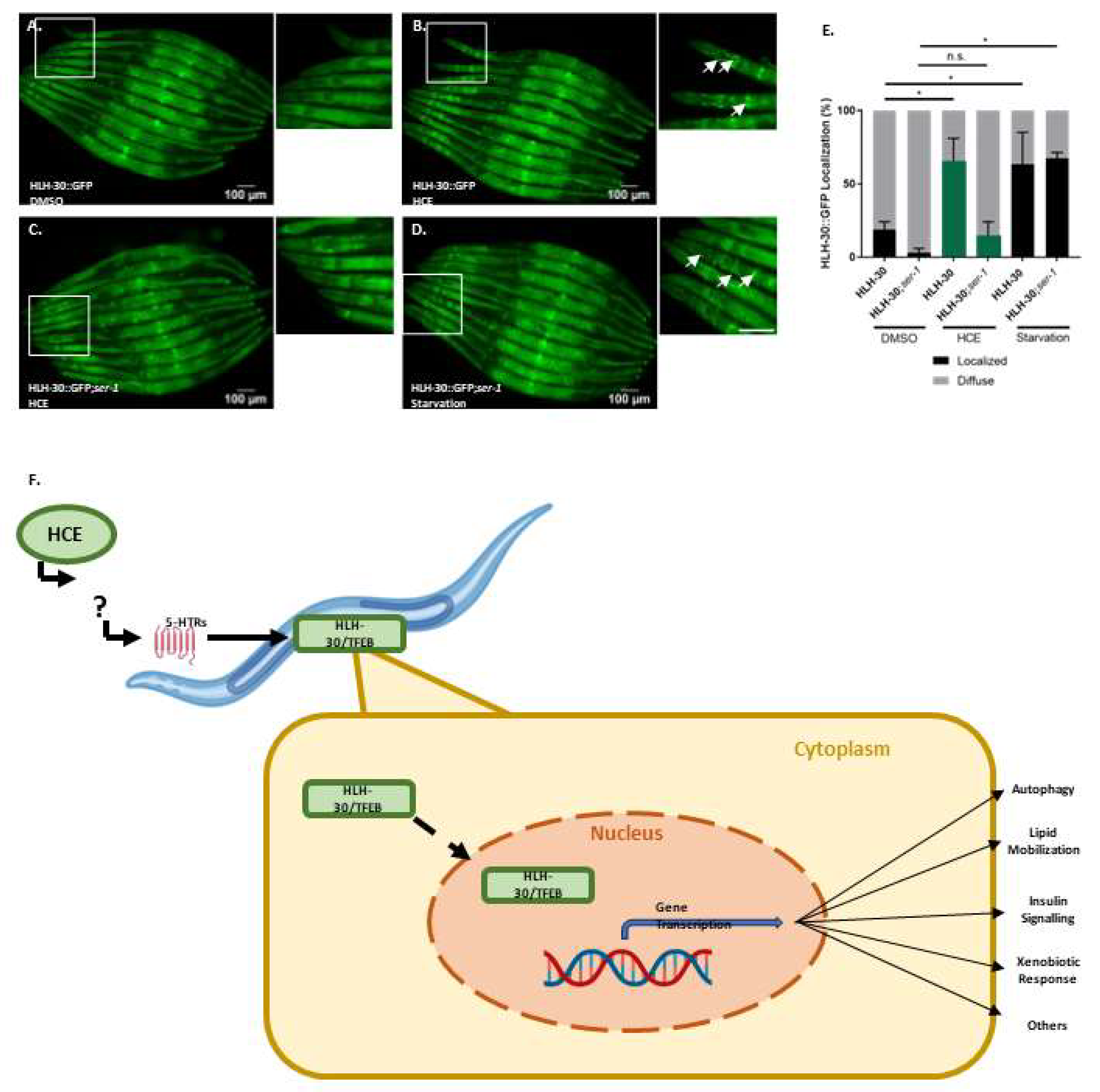

2.6. HLH-30/TFEB activation by HCE treatment requires serotonergic signalling

Considering the findings indicating that HCE effects in MJD/SCA3 depended on serotonergic signaling and that this extract induced HLH-30/TFEB nuclear translocation (

Figure 4 and 6), we next investigated whether HLH-30/TFEB activation was also controlled by serotonergic signaling. In the double mutant resulting from the crossing between the HLH-30::GFP

C. elegans reporter strain and a strain lacking the SER-1 receptor, we observed a significantly reduced HLH-30 nuclear localization upon HCE treatment compared to the parental strain (

Figure 7 A.-E.). This result indicated that, in HCE-treated animals, HLH-30 nuclear translocation is dependent on serotonergic signaling. Intriguingly, no impact on HLH-30 nuclear translocation was observed in the starved animals, suggesting that starvation activates HLH-30 through a different pathway and independently from serotonergic signaling. This indicates that HCE depends on the serotonergic system to elicit the activation of the HLH-30 transcription factor.

3. Discussion

Early diagnosis and timely interventions are possible for genetically determined neurodegenerative diseases. Nevertheless, the absence of an effective treatment hinders a more successful patient outcome, thus remaining an urgent medical need. In this study, we showed that a chronically applied extract derived from an Asian edible plant, H. citrina Baroni, improved, in a dose-dependent manner, the motor phenotypes of models of genetically determined NDs: Machado-Joseph disease, also known as Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3, caused by mutant ataxin-3 and Frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism associated with chromosome 17, determined by a mutant form of the tau protein. Despite the different genetic origin, these diseases exhibit shared clinical and mechanistic characteristics, namely aggregation of the disease-causing proteins in the brain, progressive neuronal loss and impaired movement (which in FTDP-17 is associated with a very relevant cognitive impairment). By demonstrating the therapeutic potential of extracts from H. citrina Baroni for these diseases, we support the concept of therapeutically targeting pathogenic events shared between neurodegenerative conditions.

It was demonstrated in other studies that extracts from

H. citrina Baroni modulated the levels of serotonin and other neurotransmitters in the frontal cortex and hippocampus of mice [

6]. In a similar way, several components of the

H. citrina Baroni extracts were described to affect the serotonergic system: 1) rutin, a quercetin glucoside derivative, increased serotonin in the hippocampus of a rat model of diabetes; 2) chlorogenic acid, an hydroxycinnamic acid, promoted serotonin release trough enhancing Synapsin I expression; 3) quercetin has been suggested to bind to 5-HT

1AR inhibiting the binding of serotonin and 4) kaempferol which is often acylated with hydroxycinnamic acid, inhibited the 5-HT

3AR [

15,

16,

17,

18]. These constituents are compatible with our phytochemical analysis that revealed the presence of several hydroxycinnamic acids and quercetin derivatives. We further confirmed the link between

H. citrina Baroni extract and the serotonergic system in , showing the dependency on serotonergic, but not dopaminergic, receptors for the neuroprotective effect observed in the MJD/SCA3 transgenic model. Manipulating the serotonergic system in and mouse models of MJD/SCA3 has been proven to be beneficial in previous studies performed by our team. Citalopram and befiradol chronic treatments specifically targeted the serotonergic system, resulting in an effective treatment, underlining it as key therapeutic strategy [

10,

19].

We also pinpointed the HLH-30/TFEB transcription factor as another key downstream mediator of the impact of the

H. citrina Baroni ethanolic extract on MJD. TFEB is a member of the microphthalmia/Transcription Factor E (MiT/TFE) family and also a master regulator of the autophagy-lysosome pathway (Reviewed in Martini-Stoica et al., 2016). It is key for stress resistance and elimination of protein aggregates via induction of transcription of genes involved in autophagy, lysosomal biosynthesis, both endo- and exocytosis, and membrane repair (Martini-Stoica et al., 2016). TFEB dysregulation has been reported in several neurodegenerative diseases, mainly by reduced nuclear localization, such as in the postmortem brains of Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis patients [

21,

22,

23]. Furthermore, TFEB activation as a therapeutic strategy for NDs has recently received attention, with several molecules being tested on neurodegenerative disease models (Reviewed in [

22].

The ortholog of the mammalian TFEB in , HLH-30, has been conservatively identified as a transcriptional regulator of autophagy [

24]. However, several other pathways are also controlled by HLH-30/TFEB in the nematode. For example, HLH-30/TFEB controls the mobilization of lipids under conditions of nutrient starvation [

25,

26,

27]. Neuronal HLH-30/TFEB induces peripheral mitochondrial fragmentation in response to heat stress and regulates the insulin signalling pathway, requiring DAF-16/FOXO, one of the most well described longevity mechanism in [

28]. A product of natural origin, a benzocoumarin, was also found to induce mitophagy through HLH-30 and DAF-12 activation, without increasing macroautophagy levels, showing a beneficial impact in nematode models of proteinopathies [

29]. Lastly, the transcription factor also controls expression of xenobiotic enzymes, such as the detoxification enzyme flavin-containing monooxygenase-2 (FMO-2), and of other proteins with antimicrobial action [

30]. FMO-2 overexpression led to increase lifespan and healthspan in multiple lifespan-extending paradigms, improved proteostasis. Furthermore, the impact of FMO-2 on longevity is conserved in mammals [

31,

32,

33]. However, it remains unclear which downstream mechanism are responsible for the impact of HCE on the models of NDs.

Mechanistically, this study unveiled a previously unrecognized action for H. citrina Baroni, identifying the role of HLH-30/TFEB as neuroprotective following activation by the extract. It also revealed that the activation of HLH-30 happens downstream of the serotonergic signalling, as the absence of serotonin receptors abolished HLH-30 activation upon HCE treatment. It is possible that serotonergic transmission may be influencing the non-neuronal subcellular localization and HLH-30/TFEB activity by altering the phosphorylation state of this transcription factor or the activity of upstream regulators of HLH-30/TFEB expression and that this has indirect beneficial action in the neurons through effects other than reduction of aggregation, which could include effects on mitochondria or metabolism, among others. Given the pleiotropic action of HLH-30, future multi-omics studies would be necessary to further detail the HLH-30-dependent molecular events implicated in impact of H. citrina Baroni extracts.

In summary, this work demonstrates the potential of H. citrina Baroni, an edible plant popularly used in China, as a source for novel compounds with therapeutic potential for tackling pathological events shared by different neurodegenerative diseases. Treatment with a H. citrina Baroni ethanolic extract improved a key phenotype of models of MJD/SCA3 and FTDP-17, two NDs with genetically different origins. We identified its mode of action as targeting a possible novel pathway that engages the serotonergic signalling and subsequently activates HLH-30, an orthologue of the mammalian TFEB. This underscores the significance of these mechanisms for the future development of novel therapies for neurodegenerative diseases.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Extract preparation

H. citrina Baroni flowers were collected in Qidong county, Hunan province (China), a voucher specimen was deposited at Biology Department in University of Minho with the reference DB.014.2022. It was extracted three times with 20 volumes of 80% ethanol, for 1 hour each. The resulting extracts were combined and evaporated under reduced pressure in a rotary vacuum evaporator. After drying, the extract was resuspended in water and re-extracted three times with different solvents: petroleum ether, ethyl acetate, and n-butanol. Then, the part of the n-butanol extract was run by a HP-20 macroporous resin and eluted with water, ethanol 30%, ethanol 50%, ethanol 70% and ethanol 95%. In this study, we assessed both the 30% ethanol and 50% ethanol extracts, as well as the initially obtained n-butanol extract.

4.2. Phytochemical Analysis

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detector (HPLC-DAD) was used to analyse the major constituents of H. citrina Baroni extracts as described elsewhere (Vilasboas-Campos et al., 2021). In brief, the H. citrina Baroni extracts were dissolved in methanol, filtered by a Nylaflo filter (nylon, 0.45 mM, Avantor, Portugal), poured in amber vials, and stored at 4°C, until further analysis. Separation was performed in a Purospher cartridge (250x4mm, 5 mM, Merck), data was recorded in the 200-600mn range, and chromatograms were taken at 260, 280, 325 and 350 nm. Quantification was done by the external standard method, using pure chlorogenic acid, epicatechin, and hyperoside (Sigma, Portugal), at 325, 280 and 350 nm, respectively. Unknown hydroxycinnamic acids, catechins, and flavonols were quantified as chlorogenic, epicatechin an hyperoside equivalents, respectively.

4.3. Nematode strains and maintenance

Animals were maintained in accordance with standard protocols [

34], at a constant temperature of 20 ℃ in Petri dishes with nematode growth media (NGM) (17 g/L agar, 3 g/L NaCl, 2.5 g/L Bacto peptone, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 25 mM phosphate buffer, 5 mg/mL cholesterol) and fed with OP50

Escherichia coli. Strains used in this work are listed in

Supplementary table 1.

Strains were synchronized by hypochlorite treatment (~2.6% NaClO and 0.5 M NaOH) for 7 minutes or as otherwise stated.

4.4. Extract toxicity assay

The toxicity of H. citrina Baroni extracts in vivo was determined using the wild-type N2 Bristol strain and the food clearance assay, in which the pattern of food consumption was used as a proxy development delay or arrest as previously described (Voisine et al., 2007; Teixeira-Castro et al., 2015) Absorbance was measured daily at 595 nm, using a Tecan Infinite M200 Pro plate reader (Männedorf, Switzerland).

4.5. Motility assay

Bristol N2 Wild-type mutant ATXN3 (mtATXN3) and mutant Tau (mtTau)- expressing transgenic nematodes were grown in liquid culture in 96-well microtiter plates, chronically treated with 0.125-1.000 mg/mL of extract. At day 4, animals were transferred to unseeded NGM plates at 20°C and allowed to dry for 45 minutes. Motility assays were performed as previously described [

14,

35]. In each assay, at a minimum of 50 worms were assessed per condition, and triplicates (n=3, total number of animals = 150) were performed.

4.6. Mutant ataxin-3 neuronal aggregation assay

Ataxin-3 neuronal aggregation was quantified by

in vivo confocal microscopy as previously described [

14,

36]. Aggregation was automatically quantified using MeVisLab, as described by Teixeira-Castro and colleagues (2011). Parameters examined: total number of aggregates; number of aggregates/total area; and total area of aggregates/total area of the head. Triplicates were performed, with at least six animals per condition.

4.7. Transcriptional reporter strains

Synchronized L1 larvae of CL2166 [Pgst-4:GFP], LD1171 [(Pgcs-1:GFP + rol6(su1006)], SJ4100 [Phsp-6::GFP], SJ4005 [Phsp-4::GFP] and AM722 [Phsp-70::mCherry; myo-2p::CFP] strains were grown in liquid culture with 1 mg/mL of HCE30% or vehicle (1% Dimethilsulfoxide (DMSO)) until day 4 after hatching. The following positive controls of reporter gene activation were also included: the strains CL2166 and LD1171 were grown in vehicle (1% DMSO) and incubated in 5-Hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (juglone) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 150 µM for 1h and allowed to recover at 20°C for 3h; the strain SJ4100 was treated with antimycin A, an oxidative phosphorylation inhibitor, at a final concentration of 5 µM during 24h; for SJ4005, a 24h treatment with the antibiotic tunicamycin, at a final concentration of 5µg/mL was performed; AM722 animals were subjected to a 1h heat-shock at 33°C and allowed to recover for 7h prior imaging. Fluorescence exposure time was adjusted to DMSO 1% treatment. Fluorescence intensity of each worm was measured using Fiji (ImageJ, 1.51n) and normalized to the mean of the vehicle treated worms. At least 10 animals per condition were scored in each experiment. Settings were adjusted to control conditions and used for the other conditions analysed in each experiment.

All strains expressing the sqIs17 transgene [Phlh-30::hlh-30::GFP + rol-6(su1006)] were grown in liquid culture with 1 mg/mL of HCE or vehicle (1% DMSO) from day 1 to day 4 after hatching. Starvation was used as positive control. For this, animals were transferred to unseeded plates for 30 minutes prior to imaging. Animals were considered to have nuclear translocation of HLH-30 if well-defined fluorescent nuclei were observed. At least 10 animals per condition were scored in each experiment.

All animals were anesthetized with sodium azide (2 mM) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and mounted on 3% agarose pads. Excess azide was removed, and worms were covered with a cover slide. Brightfield and Fluorescence (Fluorescein Isothiocyanate (FITC) filter) images were acquired using an Olympus Widefield Upright Microscope BX61 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), at 4x and 10x magnification or using an Olympus Widefield Inverted Microscope IX81 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at 4x and 10x magnification.

4.8. Statistical analysis

All statistical tests were performed using SPSS 27.0 (SPSS Inc.) or GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 and are reported in

Supplementary Material. Graphs were drawn using GraphPad Prism 9.5.0. A 95% confidence interval was assumed for all tests. Food consumption curves, used as a proxy for toxicity, were analysed by fitting a Non-linear regression for sigmoidal curves, and two parameters (IC50, HillSlope values) were used to compare the curves, using the least square model. Continuous variables are reported by the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM), while categorical variables are reporter by proportions. The normality of distributions was assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test and the homogeneity of variances by Brown-Forsythe test. For comparison of means of more than two groups, when all assumptions were met, One-way ANOVA was applied, followed by post-hoc bilateral Dunnet test or Tukey HSD. When normality was not assumed, Kruskal-Wallis test was performed and pairwise comparison were corrected using the Bonferroni correction. Comparisons between two groups were performed using independent samples t-tests or Mann-Withney U test when normality was not assumed. Proportion analysis was done using the Pearson’s chi-square test, with the post hoc z-test for independent proportions with Bonferroni correction.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Jorge H. Fernandes – Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft; Marta Daniela Costa - Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Methodology; Daniela Vilasboas-Campos – Investigation; Joana Pereira-Sousa – Methodology; Bruna Ferreira-Lomba – Methodology; Qiong Wang – Investigation, Resources; Andreia Teixeira-Castro – Methodology, Writing – review and editing; Xinmin Liu - Writing – review & editing, Funding Aquisition; Fengzhong Wang - Writing – review & editing, Funding Aquisition; Alberto C. P. Dias – Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing; Patrícia Maciel - Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Funding

This work was funded by National funds, through the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) - projects UID/BIA/04050/2019, UIDB/50026/2020 (DOI 10.54499/UIDB/50026/2020), UIDP/50026/2020 (DOI 10.54499/UIDP/50026/2020) and LA/P/0050/2020 (DOI 10.54499/LA/P/0050/2020), SFRH/BD/147826/2019, PD/BDE/127834/2016 and COVID/BD/151590/2020, the National Ataxia Foundation (NAF Seed Money awarded to Marta Daniela Costa, 2018), Ataxia UK (2022) and National Ataxia Foundation (NAF, 2024) to Andreia Teixeira-Castro, the National High-End Foreign Experts Recruitment Plan (G2022051012L), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFD1600100).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/

supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the members of the Maciel and Dias laboratories for helpful discussions and ideas; we also thank the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC), which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440), for providing some of the strains; Dr. Brian Kraemer who kindly provided the model of FTDP-17; We thank the Sino-Portugal TCM International Cooperation Center in The Affiliated Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, China for enabling this cooperation between Portuguese and Chinese experts.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ATXN3 |

Ataxin-3 |

| CFP |

Cyan Fluorescent Protein |

| DMSO |

Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| FITC |

Fluorescein Isothiocyanate |

| GCS-1 |

Gamma-glutamyl Cysteine Synthetase 1 |

| GFP |

Green Fluorescent Protein |

| GST-4 |

Glutathione S-Transferase 4 |

| HCE |

Hemerocallis citrina ethanolic Extract |

| HCN |

Hemerocallis citrina N-butanol extract |

| HLH |

Helix-Loop-Helix |

| HPLC-DAD |

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detector |

| HSR |

Heat Shock Response |

| MAPT |

Microtubule Associated Protein Tau |

| MiT/TFE |

Microphthalmia/Transcription Factor E |

| MJD |

Machado-Joseph Disease |

| mtATXN3 |

Mutant Ataxin-3 |

| mtTau |

Mutant Tau |

| NDs |

Neurodegenerative Diseases |

| NGM |

Nematode Growth Media |

| SCA3 |

Spinocerebellar Ataxia type 3 |

| SEM |

Standard Error of the Mean |

| SERT |

Serotonin Transporter |

| TFEB |

Transcription Factor EB |

| UPRER |

Unfolded Protein Response of the Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| UPRmt |

Unfolded Protein Response of the mitochondria |

References

- Soto, C.; Pritzkow, S. Protein Misfolding, Aggregation, and Conformational Strains in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1332–1340. [CrossRef]

- Hansson, O. Biomarkers for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 954–963. [CrossRef]

- Tyler, S.E.B.; Tyler, L.D.K. Pathways to Healing: Plants with Therapeutic Potential for Neurodegenerative Diseases. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2023, 14, 210–234. [CrossRef]

- Pohl, F.; Teixeira-Castro, A.; Costa, M.D.; Lindsay, V.; Fiúza-Fernandes, J.; Goua, M.; Bermano, G.; Russell, W.; Maciel, P.; Kong Thoo Lin, P. GST-4-Dependent Suppression of Neurodegeneration in C. Elegans Models of Parkinson’s and Machado-Joseph Disease by Rapeseed Pomace Extract Supplementation. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1091. [CrossRef]

- Vilasboas-Campos, D.; Costa, M.D.; Teixeira-Castro, A.; Rios, R.; Silva, F.G.; Bessa, C.; Dias, A.C.P.; Maciel, P. Neurotherapeutic Effect of Hyptis Spp. Leaf Extracts in Caenorhabditis Elegans Models of Tauopathy and Polyglutamine Disease: Role of the Glutathione Redox Cycle. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 162, 202–215. [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Liu, Y.-J.; Wang, Y.-B.; Yi, L.-T. Role for Monoaminergic Systems in the Antidepressant-like Effect of Ethanol Extracts from Hemerocallis Citrina. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 139, 780–787. [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Lin, J.; Gan, A.; Sun, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, M.; Wan, M.; Yan, T.; Jia, Y. Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of the Components in Flowers of Hemerocallis Citrina Baroni by UHPLC–Q-TOF-MS/MS and UHPLC–QQQ-MS/MS and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Activities. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 120, 105329. [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Yang, F.-F.; Liu, C.-Y.; Liu, X.-M.; Pan, R.-L.; Chang, Q.; Zhang, Z.-S.; Liao, Y.-H. Effects of Phenolic Constituents of Daylily Flowers on Corticosterone- and Glutamate-Treated PC12 Cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 69. [CrossRef]

- Schöls, L.; Bauer, P.; Schmidt, T.; Schulte, T.; Riess, O. Autosomal Dominant Cerebellar Ataxias: Clinical Features, Genetics, and Pathogenesis. Lancet Neurol. 2004, 3, 291–304. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira-Castro, A.; Jalles, A.; Esteves, S.; Kang, S.; da Silva Santos, L.; Silva-Fernandes, A.; Neto, M.F.; Brielmann, R.M.; Bessa, C.; Duarte-Silva, S.; et al. Serotonergic Signalling Suppresses Ataxin 3 Aggregation and Neurotoxicity in Animal Models of Machado-Joseph Disease. Brain 2015, 138, 3221–3237. [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, Y.; Okamoto, T.; Taniwaki, M.; Aizawa, M.; Inoue, M.; Katayama, S.; Kawakami, H.; Nakamura, S.; Nishimura, M.; Akiguchi, I.; et al. CAG Expansions in a Novel Gene for Machado-Joseph Disease at Chromosome 14q32.1. Nat. Genet. 1994, 8, 221–228. [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, B.C.; Zhang, B.; Leverenz, J.B.; Thomas, J.H.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Schellenberg, G.D. Neurodegeneration and Defective Neurotransmission in a Caenorhabditis Elegans Model of Tauopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003, 100, 9980–9985. [CrossRef]

- Spillantini, M.G.; Bird, T.D.; Ghetti, B. Frontotemporal Dementia and Parkinsonism Linked to Chromosome 17: A New Group of Tauopathies. Brain Pathol. 2006, 8, 387–402. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira-Castro, A.; Ailion, M.; Jalles, A.; Brignull, H.R.; Vilaça, J.L.; Dias, N.; Rodrigues, P.; Oliveira, J.F.; Neves-Carvalho, A.; Morimoto, R.I.; et al. Neuron-Specific Proteotoxicity of Mutant Ataxin-3 in C. Elegans : Rescue by the DAF-16 and HSF-1 Pathways. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 2996–3009. [CrossRef]

- Khodir, S.A.; Ali, E.; El-Domiaty, H. Rutin Exerts Antidepressant Effect in a Rat Model of Diabetes. Menoufia Med. J. 2023, 36. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Seol, H.-S.; Eom, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, C.; Park, J.-H.; Kim, T.-H.; Lee, J.H. Hydroxy Pentacyclic Triterpene Acid, Kaempferol, Inhibits the Human 5-Hydroxytryptamine Type 3A Receptor Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 544. [CrossRef]

- Rotelli, A.E.; Aguilar, C.F.; Pelzer, L.E. Structural Basis of the Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Quercetin: Inhibition of the 5-Hydroxytryptamine Type 2 Receptor. Eur. Biophys. J. 2009, 38, 865–871. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, H.; Li, H.; Tang, Y.; Yang, L.; Cao, S.; Qin, D. Antidepressant Potential of Chlorogenic Acid-Enriched Extract from Eucommia Ulmoides Oliver Bark with Neuron Protection and Promotion of Serotonin Release through Enhancing Synapsin I Expression. Molecules 2016, 21, 260. [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Sousa, J.; Ferreira-Lomba, B.; Bellver-Sanchis, A.; Vilasboas-Campos, D.; Fernandes, J.H.; Costa, M.D.; Varney, M.A.; Newman-Tancredi, A.; Maciel, P.; Teixeira-Castro, A. Identification of the 5-HT1A Serotonin Receptor as a Novel Therapeutic Target in a C. Elegans Model of Machado-Joseph Disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 152, 105278. [CrossRef]

- Martini-Stoica, H.; Xu, Y.; Ballabio, A.; Zheng, H. The Autophagy–Lysosomal Pathway in Neurodegeneration: A TFEB Perspective. Trends Neurosci. 2016, 39, 221–234. [CrossRef]

- Decressac, M.; Mattsson, B.; Weikop, P.; Lundblad, M.; Jakobsson, J.; Björklund, A. TFEB-Mediated Autophagy Rescues Midbrain Dopamine Neurons from α-Synuclein Toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, E1817–E1826. [CrossRef]

- Song, J.-X.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Li, M. Transcription Factor EB: An Emerging Drug Target for Neurodegenerative Disorders. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 164–172. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, R.; Xu, S.; Lakshmana, M.K. Transcription Factor EB Is Selectively Reduced in the Nuclear Fractions of Alzheimer’s and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Brains. Neurosci. J. 2016, 2016, 4732837. [CrossRef]

- Lapierre, L.R.; De Magalhaes Filho, C.D.; McQuary, P.R.; Chu, C.-C.; Visvikis, O.; Chang, J.T.; Gelino, S.; Ong, B.; Davis, A.E.; Irazoqui, J.E.; et al. The TFEB Orthologue HLH-30 Regulates Autophagy and Modulates Longevity in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2267. [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, A.M. Preventing Lysosomal Fat Indigestion. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 565–567. [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, E.J.; Ruvkun, G. MXL-3 and HLH-30 Transcriptionally Link Lipolysis and Autophagy to Nutrient Availability. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 668–676. [CrossRef]

- Settembre, C.; De Cegli, R.; Mansueto, G.; Saha, P.K.; Vetrini, F.; Visvikis, O.; Huynh, T.; Carissimo, A.; Palmer, D.; Jürgen Klisch, T.; et al. TFEB Controls Cellular Lipid Metabolism through a Starvation-Induced Autoregulatory Loop. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 647–658. [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.Q.; Ryan, C.J.; Bonal, D.M.; Mills, J.; Lapierre, L.R. Neuronal HLH-30/TFEB Modulates Peripheral Mitochondrial Fragmentation to Improve Thermoresistance in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Aging Cell 2023, 22, e13741. [CrossRef]

- Chamoli, M.; Rane, A.; Foulger, A.; Chinta, S.J.; Shahmirzadi, A.A.; Kumsta, C.; Nambiar, D.K.; Hall, D.; Holcom, A.; Angeli, S.; et al. A Drug-like Molecule Engages Nuclear Hormone Receptor DAF-12/FXR to Regulate Mitophagy and Extend Lifespan. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 1529–1543. [CrossRef]

- Visvikis, O.; Ihuegbu, N.; Labed, S.A.; Luhachack, L.G.; Alves, A.-M.F.; Wollenberg, A.C.; Stuart, L.M.; Stormo, G.D.; Irazoqui, J.E. Innate Host Defense Requires TFEB-Mediated Transcription of Cytoprotective and Antimicrobial Genes. Immunity 2014, 40, 896–909. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.; Bhat, A.; Howington, M.B.; Schaller, M.L.; Cox, R.L.; Huang, S.; Beydoun, S.; Miller, H.A.; Tuckowski, A.M.; Mecano, J.; et al. FMO Rewires Metabolism to Promote Longevity through Tryptophan and One Carbon Metabolism in C. Elegans. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 562. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Howington, M.B.; Dobry, C.J.; Evans, C.R.; Leiser, S.F. Flavin-Containing Monooxygenases Are Conserved Regulators of Stress Resistance and Metabolism. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9.

- Leiser, S.F.; Miller, H.; Rossner, R.; Fletcher, M.; Leonard, A.; Primitivo, M.; Rintala, N.; Ramos, F.J.; Miller, D.L.; Kaeberlein, M. Cell Nonautonomous Activation of Flavin-Containing Monooxygenase Promotes Longevity and Health Span. Science 2015, 350, 1375–1378. [CrossRef]

- Brenner, S. THE GENETICS OF CAENORHABDITIS ELEGANS. Genetics 1974, 77, 71–94. [CrossRef]

- Gidalevitz, T.; Ben-Zvi, A.; Ho, K.H.; Brignull, H.R.; Morimoto, R.I. Progressive Disruption of Cellular Protein Folding in Models of Polyglutamine Diseases. Science 2006, 311, 1471–1474. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira-Castro, A.; Dias, N.; Rodrigues, P.; Oliveira, J.F.; Rodrigues, N.F.; Maciel, P.; Vilaça, J.L. An Image Processing Application for Quantification of Protein Aggregates in Caenorhabditis Elegans. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Practical Applications of Computational Biology & Bioinformatics (PACBB 2011); Rocha, M.P., Rodríguez, J.M.C., Fdez-Riverola, F., Valencia, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 31–38.

Figure 1.

H. citrina Baroni 30% ethanolic extract (HCE30%) improves MJD motor deficits independent of ATXN3 aggregation in neurons. A. HCE30%, B. HCE50% and C. HCN effect on locomotion deficits of mutant ataxin-3 (mtATXN3) expressing animals (0.125 – 1.000 mg/mL) compared to animals treated with vehicle only (DMSO 1%) and N2 WT animals. Bars represent mean percentage of animals considered as locomotion defective in a motility assay ± SEM for 3 independent assays, at least 50 animals per condition, per assay (total number of animals = 150). p ≤ 0.05 (*); p ≤ 0.01 (**); p ≤ 0.001 (***). D. Confocal imaging of the head of AT3q130 animals treated with vehicle (DMSO 1%) or HCE30% (1 mg/mL). Pictures are representative of three independent experiments. E. Quantification of the number of mutant ataxin-3 aggregates normalized per total area, area of aggregates per total area; and area of aggregates per total number of aggregates. Bars represent the mean, normalized to vehicle treated ± SEM of at leat 10 animals per condition per experiment. p < 0.05. Scale bar 50 µm.

Figure 1.

H. citrina Baroni 30% ethanolic extract (HCE30%) improves MJD motor deficits independent of ATXN3 aggregation in neurons. A. HCE30%, B. HCE50% and C. HCN effect on locomotion deficits of mutant ataxin-3 (mtATXN3) expressing animals (0.125 – 1.000 mg/mL) compared to animals treated with vehicle only (DMSO 1%) and N2 WT animals. Bars represent mean percentage of animals considered as locomotion defective in a motility assay ± SEM for 3 independent assays, at least 50 animals per condition, per assay (total number of animals = 150). p ≤ 0.05 (*); p ≤ 0.01 (**); p ≤ 0.001 (***). D. Confocal imaging of the head of AT3q130 animals treated with vehicle (DMSO 1%) or HCE30% (1 mg/mL). Pictures are representative of three independent experiments. E. Quantification of the number of mutant ataxin-3 aggregates normalized per total area, area of aggregates per total area; and area of aggregates per total number of aggregates. Bars represent the mean, normalized to vehicle treated ± SEM of at leat 10 animals per condition per experiment. p < 0.05. Scale bar 50 µm.

Figure 2.

H. citrina Baroni 30% ethanolic extract (HCE30%) improves motor deficits in a FTDP-17 C. elegans model expressing mutant Tau protein (mtTau). A. HCE30%, B. HCE50% and C. HCN effect on locomotion deficits of mtTau (0.125 – 1.000 mg/mL) compared to animals treated with vehicle only (DMSO 1%) and N2 WT animals. Bars represent mean percentage of animals considered as locomotion defective in a motility assay ± SEM for 3 independent assays, at least 50 animals per condition, per assay (total number of animals = 150). p ≤ 0.05 (*); p ≤ 0.01 (**); p ≤ 0.001 (***).

Figure 2.

H. citrina Baroni 30% ethanolic extract (HCE30%) improves motor deficits in a FTDP-17 C. elegans model expressing mutant Tau protein (mtTau). A. HCE30%, B. HCE50% and C. HCN effect on locomotion deficits of mtTau (0.125 – 1.000 mg/mL) compared to animals treated with vehicle only (DMSO 1%) and N2 WT animals. Bars represent mean percentage of animals considered as locomotion defective in a motility assay ± SEM for 3 independent assays, at least 50 animals per condition, per assay (total number of animals = 150). p ≤ 0.05 (*); p ≤ 0.01 (**); p ≤ 0.001 (***).

Figure 3.

The phytochemical profile of HCE30%. The chromatographic analysis revealed that HCE30% was mainly composed of (E1) epicatechin and (E2) epicatechin derivative, (Q) quercetin glucoside and up to 70% of (H1-H6) hydroxycinnamic acids. U- unknown compound. Quantification can be found in

Supplementary table 2.

Figure 3.

The phytochemical profile of HCE30%. The chromatographic analysis revealed that HCE30% was mainly composed of (E1) epicatechin and (E2) epicatechin derivative, (Q) quercetin glucoside and up to 70% of (H1-H6) hydroxycinnamic acids. U- unknown compound. Quantification can be found in

Supplementary table 2.

Figure 4.

T Motor phenotype amelioration of C. elegans model by H. citrina Baroni 30% ethanolic extract is dependent on serotonergic but not dopaminergic Signalling. A. Schematic representation of a synapse where dopaminergic and serotonergic receptors are represented. HCE30% is effective in reducing motor deficits in the mtATXN3 background when B. dop-1 and C. dop-3 are ablated. Knock-down of serotonergic receptors D. ser-1, E. ser-5 and F. ser-7 resulted in total loss of the motor phenotype improvement provoked by HCE treatment. Ablation of serotonin autoreceptor G. ser-4 and transporter (H) mod-5 improved the motor deficits displayed by the MJD nematode model that was further extended by treatment with estrone (which as a mode of action independent of serotonergic Signalling) while HCE treatment did not have an additive effect, suggesting that the two interventions are acting in the same pathway. Statistics: B.-H. One-Way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Tuckey HSD test for multiple comparisons. Bars represent mean ± SEM. n=4; p ≤ 0.05 (*); p ≤ 0.01 (**); p ≤ 0.001 (***).

Figure 4.

T Motor phenotype amelioration of C. elegans model by H. citrina Baroni 30% ethanolic extract is dependent on serotonergic but not dopaminergic Signalling. A. Schematic representation of a synapse where dopaminergic and serotonergic receptors are represented. HCE30% is effective in reducing motor deficits in the mtATXN3 background when B. dop-1 and C. dop-3 are ablated. Knock-down of serotonergic receptors D. ser-1, E. ser-5 and F. ser-7 resulted in total loss of the motor phenotype improvement provoked by HCE treatment. Ablation of serotonin autoreceptor G. ser-4 and transporter (H) mod-5 improved the motor deficits displayed by the MJD nematode model that was further extended by treatment with estrone (which as a mode of action independent of serotonergic Signalling) while HCE treatment did not have an additive effect, suggesting that the two interventions are acting in the same pathway. Statistics: B.-H. One-Way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Tuckey HSD test for multiple comparisons. Bars represent mean ± SEM. n=4; p ≤ 0.05 (*); p ≤ 0.01 (**); p ≤ 0.001 (***).

Figure 5.

HCE treatment did not induce the antioxidant response, the ER or Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein Response or the Heat Shock Response pathways. Fluorescence images of Pgst-4::GFP animals treated with A. vehicle (DMSO 1%), B. HCE (1 mg/mL) and C. vehicle treated followed by juglone treatment as positive control. Scale bar = 300 µm. Graphical results shown in D. represent the fluorescence levels, normalized for control. Fluorescence images of Pgcs-1::GFP animals treated with E. vehicle (DMSO 1%), F. HCE (1 mg/mL) and G. vehicle treated followed by juglone treatment as positive control. Scale bar = 300 µm. Graphical results shown in H. represent the fluorescence levels, normalized for control. Fluorescence images of Phsp-6::GFP animals treated with I. vehicle (DMSO 1%), J. HCE (1 mg/mL) and K. vehicle treated followed by antimycin A treatment as positive control. Scale bar = 300 µm. Graphical results shown in L. represent the fluorescence levels, normalized for control. Fluorescence images of Phsp-4::GFP animals treated with M. vehicle (DMSO 1%), N. HCE (1 mg/mL) and O. vehicle treated followed by tunicamycin treatment as positive control. Scale bar = 200 µm. Graphical results shown in P. represent the fluorescence levels, normalized for control. Fluorescence images of Phsp-70::mCherry animals treated with Q. vehicle (DMSO 1%), R. HCE (1 mg/mL) and S. vehicle treated followed by heat-shock at 33o C for 60 minutes, followed by a period of recovery of 7 hours and treatment as positive control. Scale bar = 300 µm. Graphical results shown in (t) represent the fluorescence levels, normalized for control. Bars represent mean ± SEM. n=15 p ≤ 0.05 (*); p ≤ 0.01 (**); p ≤ 0.001 (***)

Figure 5.

HCE treatment did not induce the antioxidant response, the ER or Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein Response or the Heat Shock Response pathways. Fluorescence images of Pgst-4::GFP animals treated with A. vehicle (DMSO 1%), B. HCE (1 mg/mL) and C. vehicle treated followed by juglone treatment as positive control. Scale bar = 300 µm. Graphical results shown in D. represent the fluorescence levels, normalized for control. Fluorescence images of Pgcs-1::GFP animals treated with E. vehicle (DMSO 1%), F. HCE (1 mg/mL) and G. vehicle treated followed by juglone treatment as positive control. Scale bar = 300 µm. Graphical results shown in H. represent the fluorescence levels, normalized for control. Fluorescence images of Phsp-6::GFP animals treated with I. vehicle (DMSO 1%), J. HCE (1 mg/mL) and K. vehicle treated followed by antimycin A treatment as positive control. Scale bar = 300 µm. Graphical results shown in L. represent the fluorescence levels, normalized for control. Fluorescence images of Phsp-4::GFP animals treated with M. vehicle (DMSO 1%), N. HCE (1 mg/mL) and O. vehicle treated followed by tunicamycin treatment as positive control. Scale bar = 200 µm. Graphical results shown in P. represent the fluorescence levels, normalized for control. Fluorescence images of Phsp-70::mCherry animals treated with Q. vehicle (DMSO 1%), R. HCE (1 mg/mL) and S. vehicle treated followed by heat-shock at 33o C for 60 minutes, followed by a period of recovery of 7 hours and treatment as positive control. Scale bar = 300 µm. Graphical results shown in (t) represent the fluorescence levels, normalized for control. Bars represent mean ± SEM. n=15 p ≤ 0.05 (*); p ≤ 0.01 (**); p ≤ 0.001 (***)

Figure 6.

HCE treatment induces HLH-30 nuclear translocation. Fluorescence images of A. vehicle (DMSO 1%), B. HCE (1.000 mg/mL) and C. vehicle treated followed by 30 minute starvation period Phlh-30::HLH-30::GFP animals. Arrows point to examples of nuclear translocation. Scale bar = 300 μm. Graphical results shown in D. represent the proportion of animals that presented nuclear localization of the HLH-30 transcription factor as displayed by the formation of clear GFP puncta. Treatment with HCE resulted in nuclear translocation of the transcription factor in levels similar to starvation. Pearson Chi-square test, Post-hoc pairwise comparisons using Z-tests were conducted to compare column proportions.; p ≤ 0.05 (*). HLH-30/TFEB transcription factor is necessary for HCE effect and dependent on serotonergic Signalling. Ablation of the hlh-30 in the (E) mtTau and (F) mtATXN3 background resulted in the loss of the motor phenotype amelioration. Bars represent mean ± SEM. n=4; p ≤ 0.05 (*); p ≤ 0.01 (**); p ≤ 0.001 (***).

Figure 6.

HCE treatment induces HLH-30 nuclear translocation. Fluorescence images of A. vehicle (DMSO 1%), B. HCE (1.000 mg/mL) and C. vehicle treated followed by 30 minute starvation period Phlh-30::HLH-30::GFP animals. Arrows point to examples of nuclear translocation. Scale bar = 300 μm. Graphical results shown in D. represent the proportion of animals that presented nuclear localization of the HLH-30 transcription factor as displayed by the formation of clear GFP puncta. Treatment with HCE resulted in nuclear translocation of the transcription factor in levels similar to starvation. Pearson Chi-square test, Post-hoc pairwise comparisons using Z-tests were conducted to compare column proportions.; p ≤ 0.05 (*). HLH-30/TFEB transcription factor is necessary for HCE effect and dependent on serotonergic Signalling. Ablation of the hlh-30 in the (E) mtTau and (F) mtATXN3 background resulted in the loss of the motor phenotype amelioration. Bars represent mean ± SEM. n=4; p ≤ 0.05 (*); p ≤ 0.01 (**); p ≤ 0.001 (***).

Figure 7.

HCE activation of HLH-30 depends on the SER-1 serotonin receptor. Brightfield and fluorescence images of A. Phlh-30::HLH-30::GFP animals treated with vehicle (DMSO1%), B. HCE C. Phlh-30::HLH-30::GFP;ser-1 animals treated with HCE and D. Phlh-30::HLH-30::GFP; ser-1 animals treated with vehicle followed by 30 minutes starvation period. Arrows point to examples of nuclear translocation. Scale bar = 100 μm. Graphical results shown in E. represent the proportion of animals that presented nuclear localization of the HLH-30 transcription factor as displayed by the formation of clear GFP puncta. Treatment with HCE30% resulted in nuclear translocation of the transcription factor in levels similar to starvation; p ≤ 0.05 (*). F. Model of serotonin and HLH-30/TFEB dependent mode of action of HCE effect.

Figure 7.

HCE activation of HLH-30 depends on the SER-1 serotonin receptor. Brightfield and fluorescence images of A. Phlh-30::HLH-30::GFP animals treated with vehicle (DMSO1%), B. HCE C. Phlh-30::HLH-30::GFP;ser-1 animals treated with HCE and D. Phlh-30::HLH-30::GFP; ser-1 animals treated with vehicle followed by 30 minutes starvation period. Arrows point to examples of nuclear translocation. Scale bar = 100 μm. Graphical results shown in E. represent the proportion of animals that presented nuclear localization of the HLH-30 transcription factor as displayed by the formation of clear GFP puncta. Treatment with HCE30% resulted in nuclear translocation of the transcription factor in levels similar to starvation; p ≤ 0.05 (*). F. Model of serotonin and HLH-30/TFEB dependent mode of action of HCE effect.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).