Submitted:

23 March 2025

Posted:

25 March 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Short Introduction to Alena Tensor

2.1. Transforming a Curved Path into a Geodesic

- is the density of the total four-force acting on matter

- are forces due to the field, where

- is the density of the electromagnetic four-force

- was shown in [9] as related to the presence of gravity in the system.

- is invariant of the electromagnetic field tensor,

- is trace of ,

- is a metric tensor of a spacetime for which vanishes.

- in flat spacetime is the usual, classical energy-momentum tensor of the electromagnetic field

- its trace vanishes in any spacetime, regardless of the considered metric tensor

- in spacetime for which the entire tensor vanishes

- which is expected property of the metric tensor (it was already shown in [10] that indeed is a metric tensor)

2.2. Connection with Continuum Mechanics, GR and QFT/QM

- is the density of the radiation reaction four-force

- is density of the four-force related to gravity, where

- is related to the effective potential in the system with gravity.

- - which turns out to be the case of free fall

- which occurs in the case of circular orbits

-

simplified Dirac equation for QED:

- Klein-Gordon equation,

- equivalent of the Schrödinger equation:

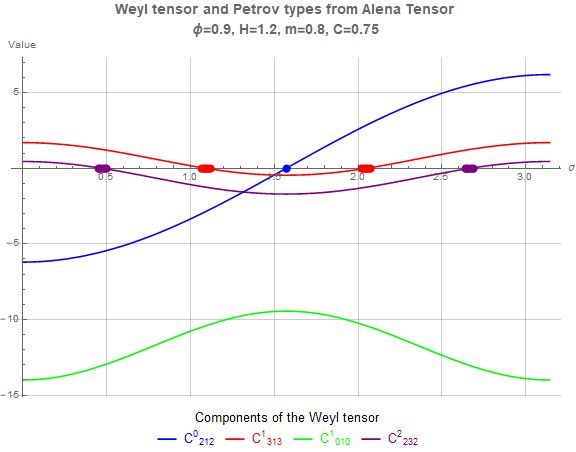

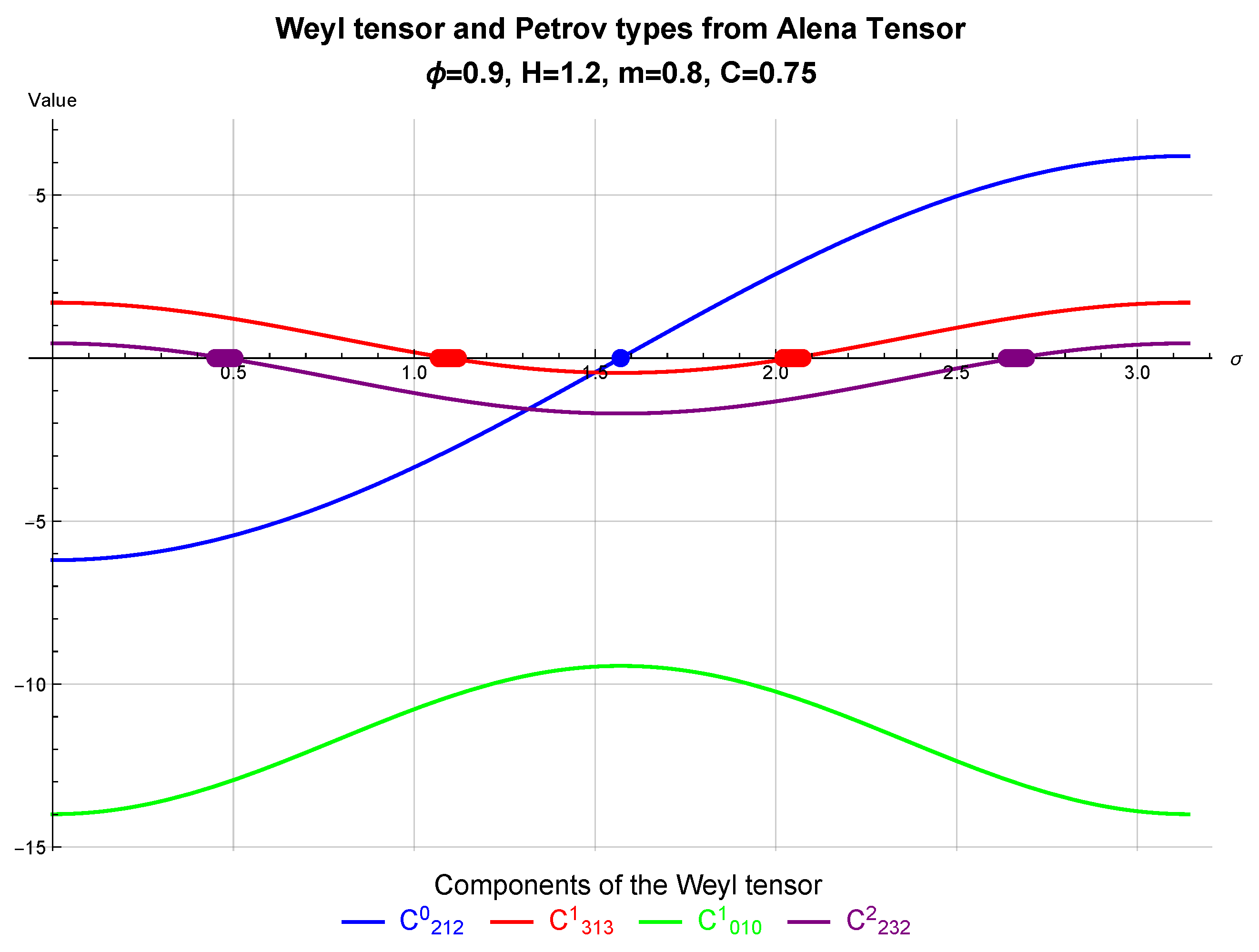

3. Results

- relative permeability

- volume magnetic susceptibility

- relative permittivity

- electric susceptibility

| Component | Value |

4. Conclusion and Discussion

5. Statements

References

- Bailes, M.; Berger, B.K.; Brady, P.; Branchesi, M.; Danzmann, K.; Evans, M.; Holley-Bockelmann, K.; Iyer, B.; Kajita, T.; Katsanevas, S.; et al. Gravitational-wave physics and astronomy in the 2020s and 2030s. Nature Reviews Physics 2021, 3, 344–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, B.F. Gravitational wave astronomy. Classical and Quantum Gravity 1999, 16, A131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Nichols, D.A. Outlook for detecting the gravitational-wave displacement and spin memory effects with current and future gravitational-wave detectors. Physical Review D 2023, 107, 064056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borhanian, S.; Sathyaprakash, B. Listening to the universe with next generation ground-based gravitational-wave detectors. Physical Review D 2024, 110, 083040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. Gravitational waves in bimetric MOND. Physical Review D 2014, 89, 024027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahura, S.; Nichols, D.A.; Yagi, K. Gravitational-wave memory effects in Brans-Dicke theory: Waveforms and effects in the post-Newtonian approximation. Physical Review D 2021, 104, 104010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, I.S.; Calvão, M.O.; Waga, I. Gravitational wave propagation in f (R) models: New parametrizations and observational constraints. Physical Review D 2021, 103, 104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, I.L.; Pelinson, A.M.; de O. Salles, F. Gravitational waves and perspectives for quantum gravity. Modern Physics Letters A 2014, 29, 1430034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogonowski, P.; Skindzier, P. Alena Tensor in unification applications. Physica Scripta 2024, 100, 015018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogonowski, P. Proposed method of combining continuum mechanics with Einstein Field Equations. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2023, 2350010, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogonowski, P. Developed method: interactions and their quantum picture. Frontiers in Physics 2023, 11, 1264925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logunov, A.; Mestvirishvili, M. Hilbert’s causality principle and equations of general relativity exclude the possibility of black hole formation. Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 2012, 170, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Y. Superposition principle in relativistic gravity. Physica Scripta 2024, 99, 105045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplawski, N.J. Geometrical formulation of classical electromagnetism. arXiv 2008, arXiv:0802.4453. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.F. Unification of gravitational and electromagnetic fields in Riemannian geometry. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0901.0201. [Google Scholar]

- Chernitskii, A.A. On unification of gravitation and electromagnetism in the framework of a general-relativistic approach. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0907.2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholmetskii, A.; Missevitch, O.; Yarman, T. Generalized electromagnetic energy-momentum tensor and scalar curvature of space at the location of charged particle. arXiv 2009, arXiv:1111.2500. [Google Scholar]

- Novello, M.; Falciano, F.; Goulart, E. Electromagnetic Geometry. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1111.2631. [Google Scholar]

- de Araujo Duarte, C. The classical geometrization of the electromagnetism. International Journal of Geometric Methods in Modern Physics 2015, 12, 1560022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojman, S.A. Geometrical unification of gravitation and electromagnetism. The European Physical Journal Plus 2019, 134, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, R. Space-time curvature of classical electromagnetism. arXiv 2004, arXiv:gr-qc/0410043. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, H.; Hamm, B.; Hirsch, S.; Wheeler, J.; Zhang, Y. Flatly foliated relativity. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.00967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, N. Evolution of the concept of the curvature in the momentum space. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.08553. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, L.; Wazwaz, A.M. Similarity solutions of field equations with an electromagnetic stress tensor as source. Rom. Rep. Phys 2018, 70, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- MacKay, R.; Rourke, C. Natural observer fields and redshift. J Cosmology 2011, 15, 6079–6099. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, N.; Nouri-Zonoz, M. Massive spinor fields in flat spacetimes with nontrivial topology. Physical Review D—Particles, Fields, Gravitation, and Cosmology 2005, 71, 104012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waluk, P.; Jezierski, J. Gauge-invariant description of weak gravitational field on a spherically symmetric background with cosmological constant. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2019, 36, 215006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghinoni, B.; Flizikowski, G.; Malacarne, L.C.; Partanen, M.; Bialkowski, S.; Astrath, N.G.C. On the formulations of the electromagnetic stress–energy tensor. Annals of Physics 2022, 443, 169004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G. Wave Surface Symmetry and Petrov Types in General Relativity. Symmetry 2024, 16, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignat’ev, Y.G. The self-consistent field method and the macroscopic universe consisting of a fluid and black holes. Gravitation and Cosmology 2019, 25, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. Emergent gravity paradigm: recent progress. Modern Physics Letters A 2015, 30, 1540007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, A.; Surya, S.; Versteegen, F. Induced spatial geometry from causal structure. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2019, 36, 105005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakharov, A.D. Vacuum quantum fluctuations in curved space and the theory of gravitation. General Relativity and Gravitation 2000, 32, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sämann, C.; Steinbauer, R.; Švarc, R. Completeness of general pp-wave spacetimes and their impulsive limit. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2016, 33, 215006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, W. Robinson–Trautman solutions to Einstein’s equations. General Relativity and Gravitation 2017, 49, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. Reformulation of the cosmological constant problem. Physical Review Letters 2020, 125, 051301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueorguiev, V.G.; Maeder, A. Revisiting the Cosmological Constant Problem within Quantum Cosmology. Universe 2020, 6, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, A. Defining geometric gauge theory to accommodate particles, continua, and fields. Journal of Mathematical Physics 2024, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech, G. Scalar induced gravitational waves review. Universe 2021, 7, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakitzis, T.P. Spatial wavefunctions of spin. Physica Scripta 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).