Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Al-MIL-101-NH2 (Al-MOF1)

2.2. Synthesis of Cr-MIL-101-NH2 (Cr-MOF1)

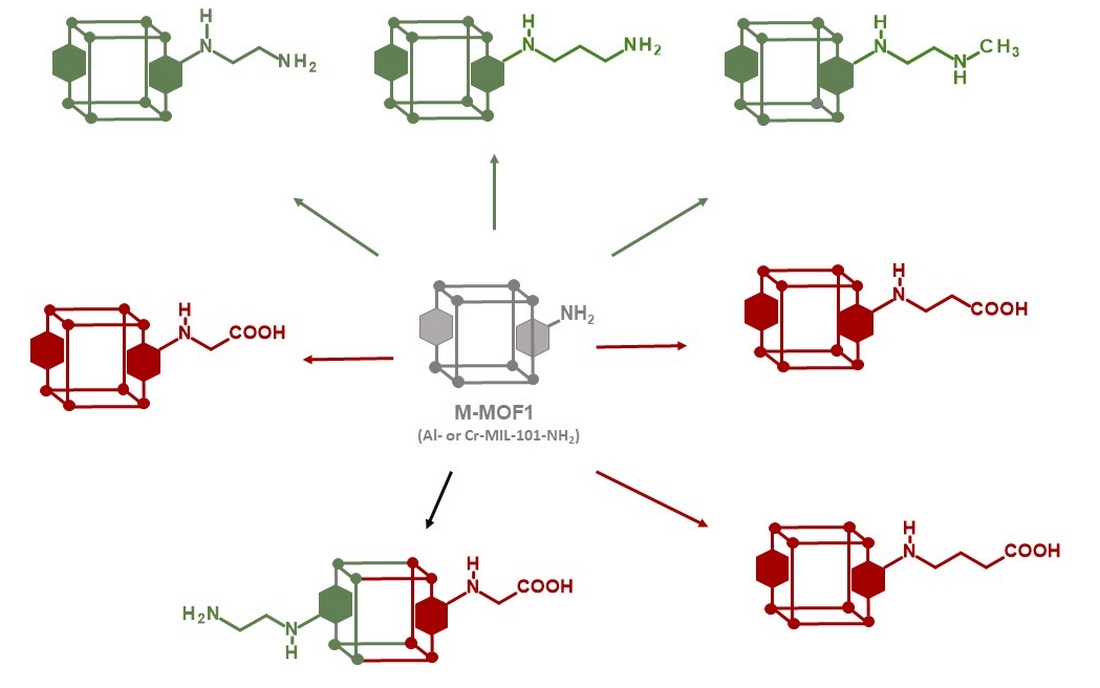

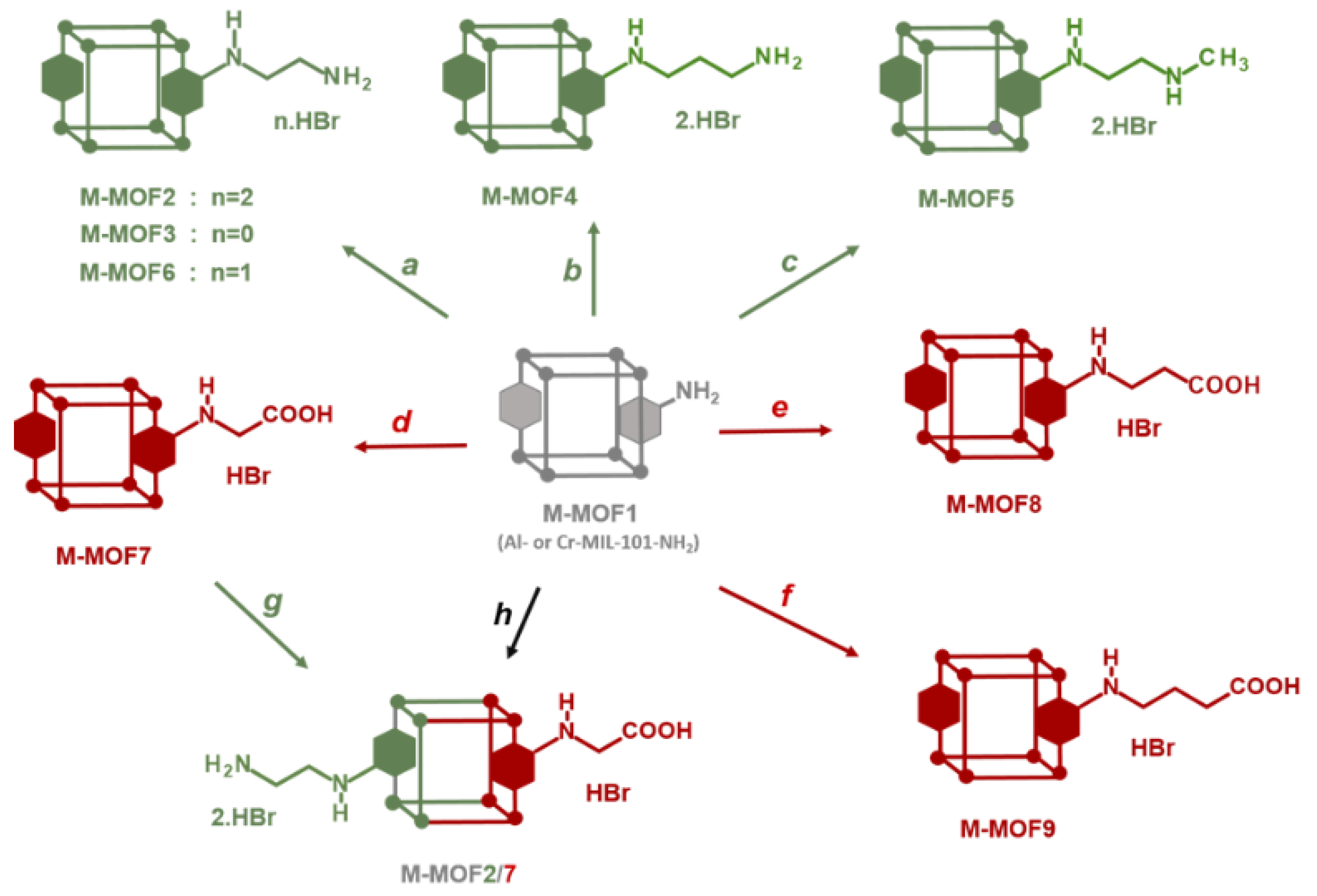

2.3. MOFs Post-Synthetic Modifications

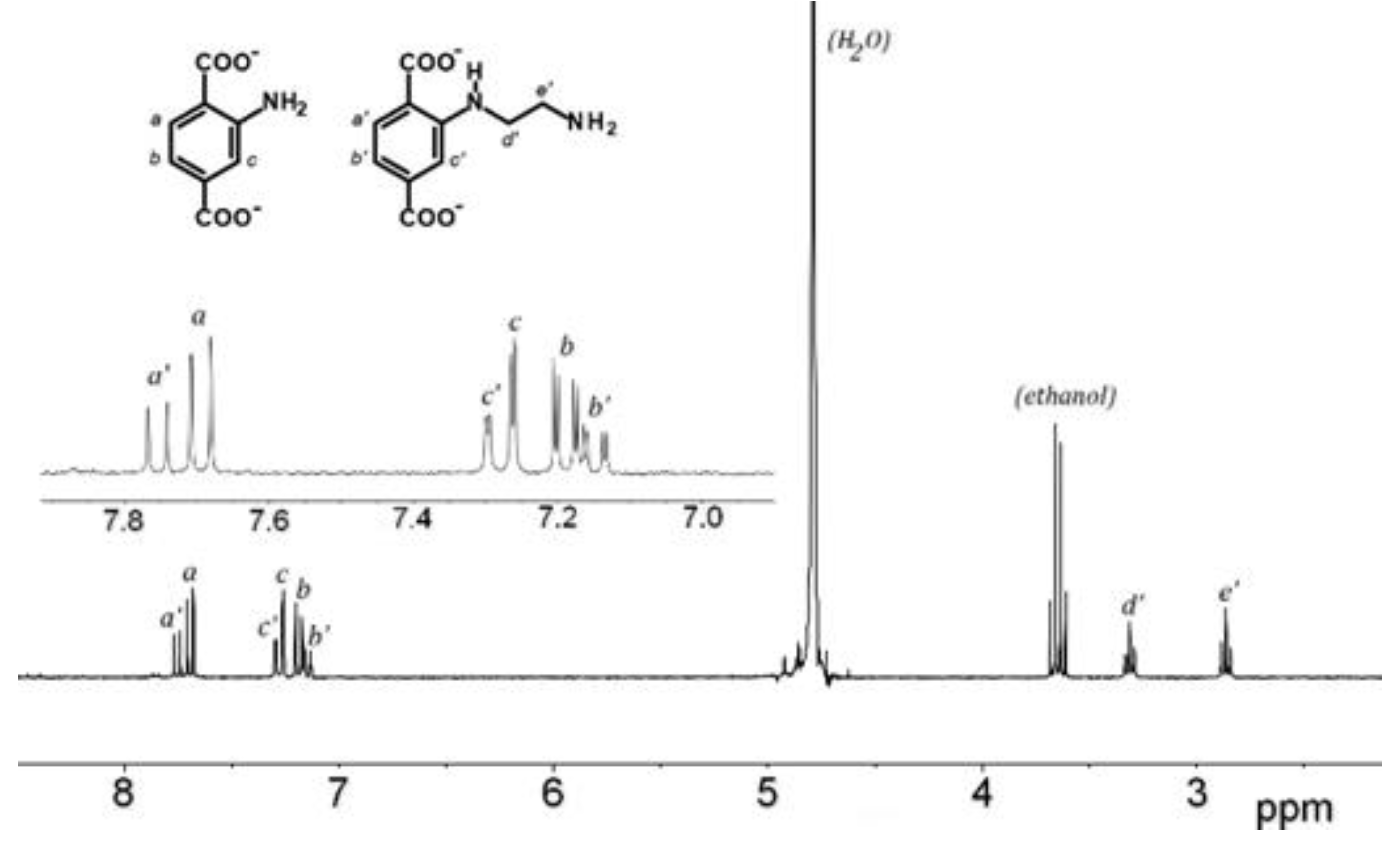

2.4. LC-MS Yields Determination

3. Results and Discussion

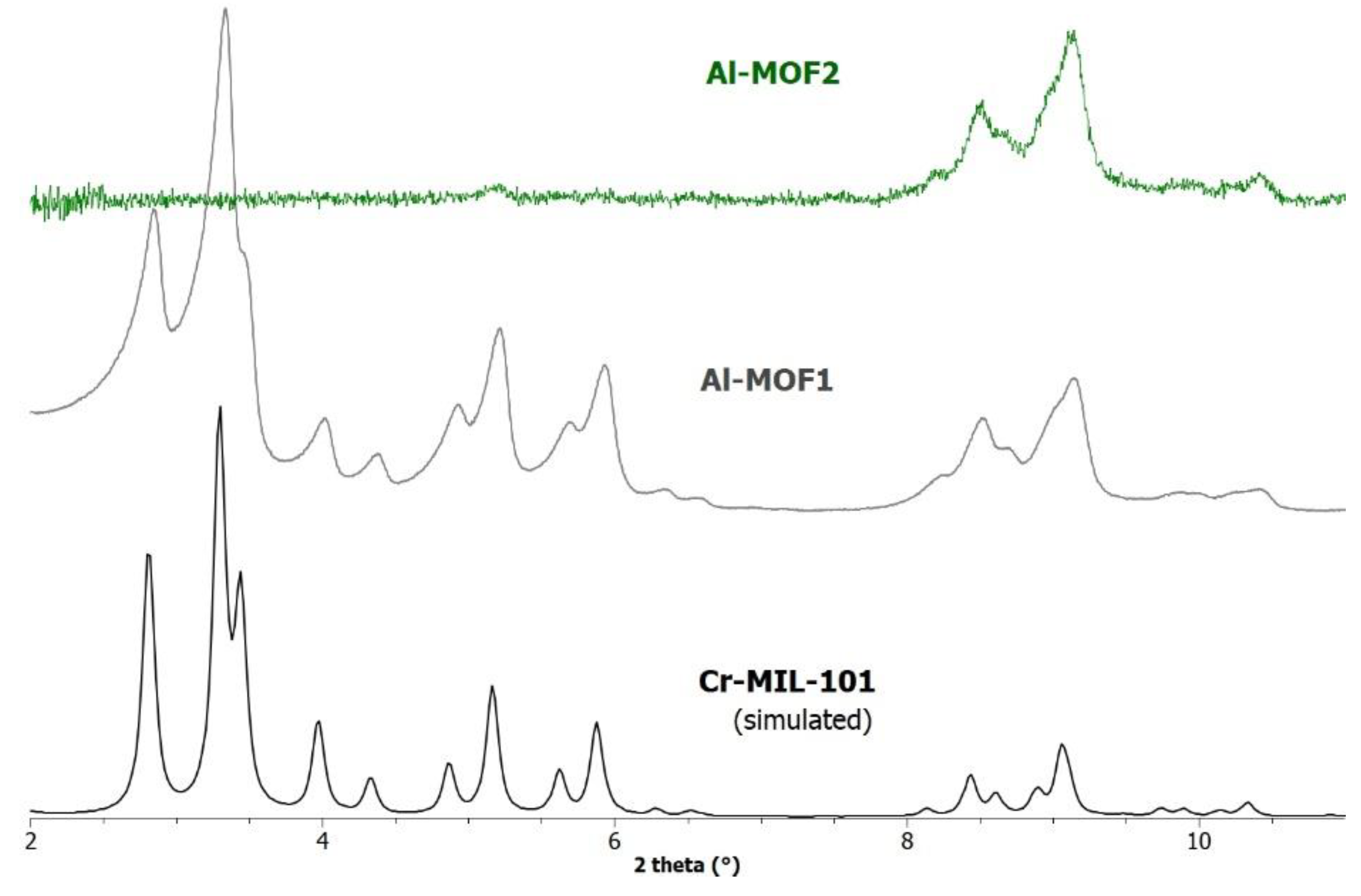

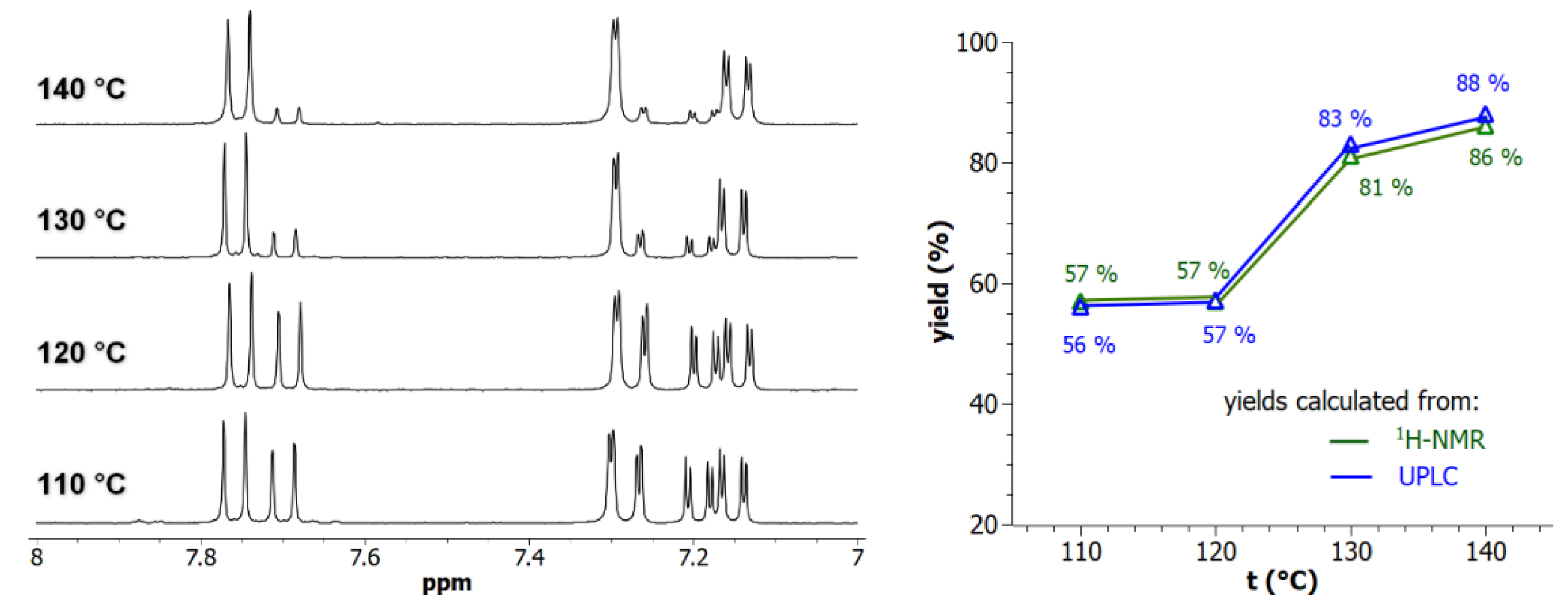

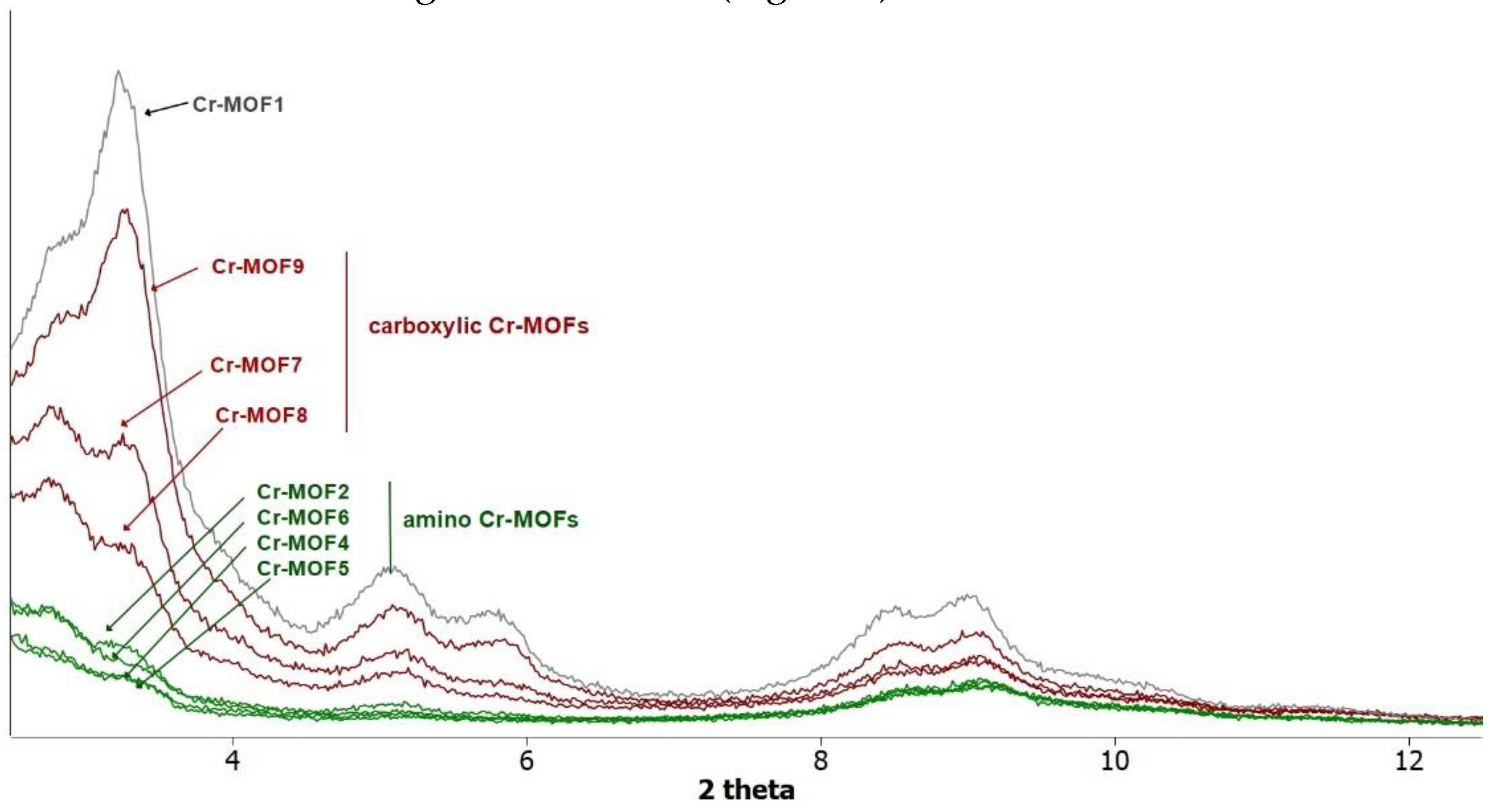

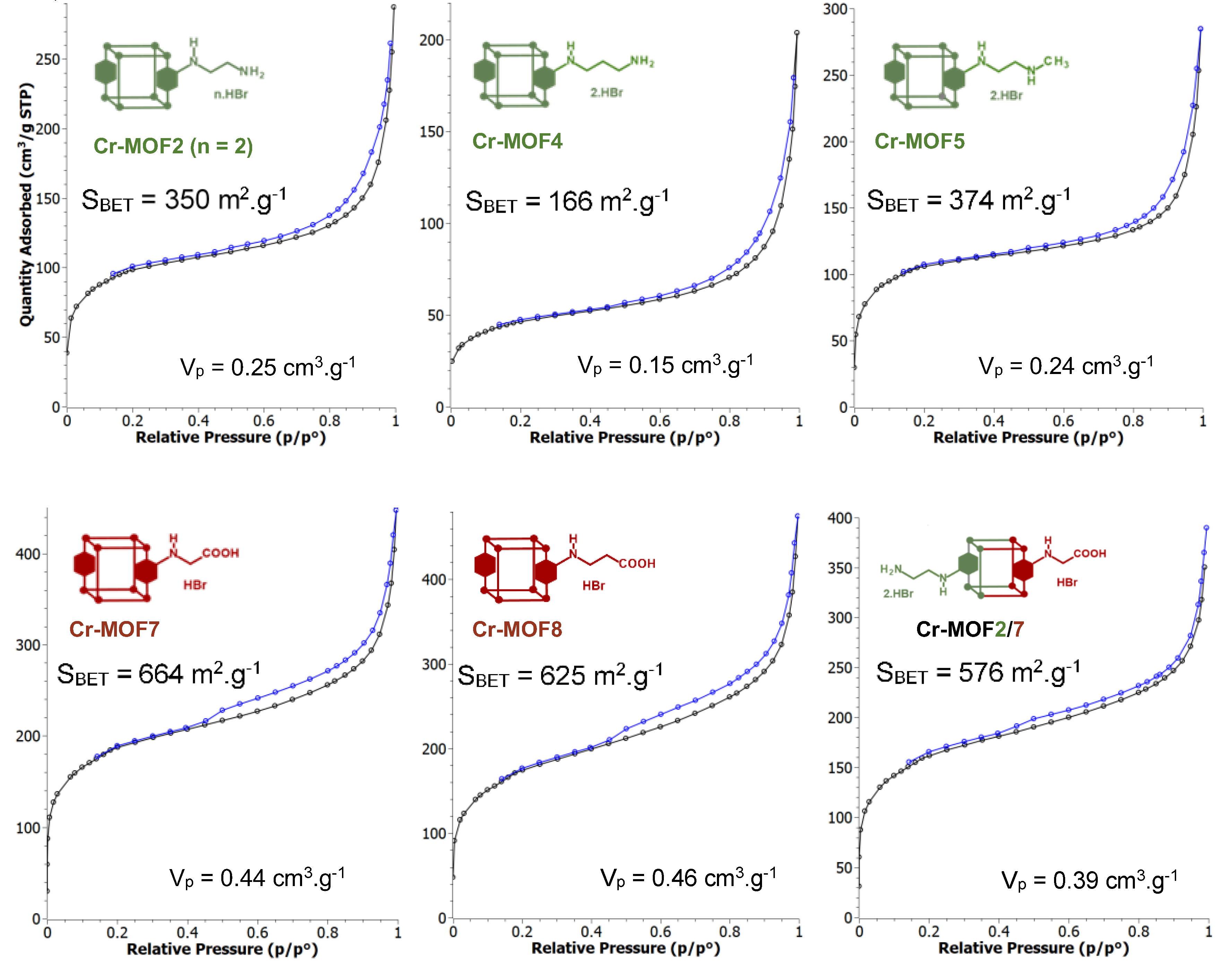

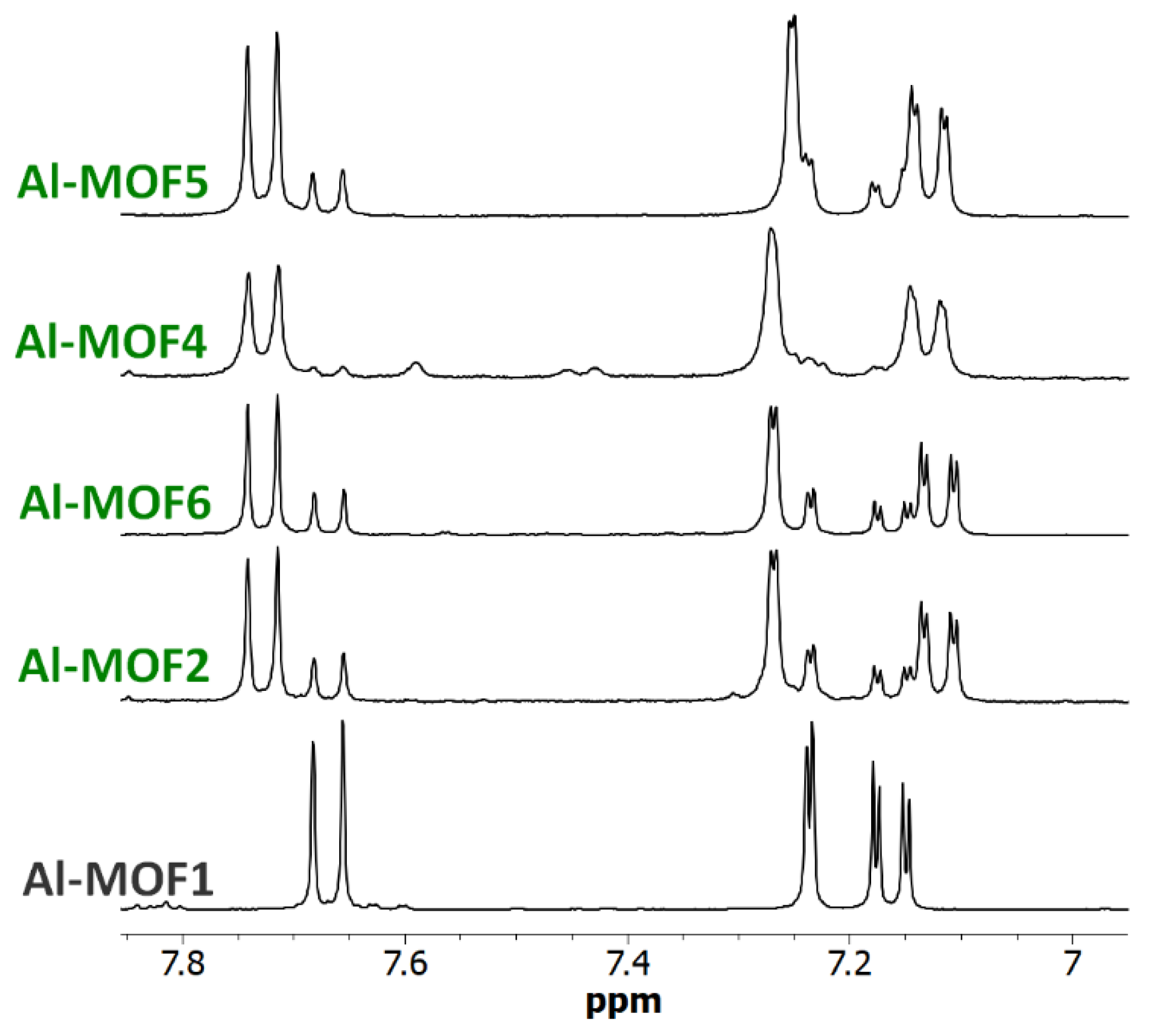

3.1. Postmodification with Amino Groups

3.2. Postmodification with Carboxylic Acids

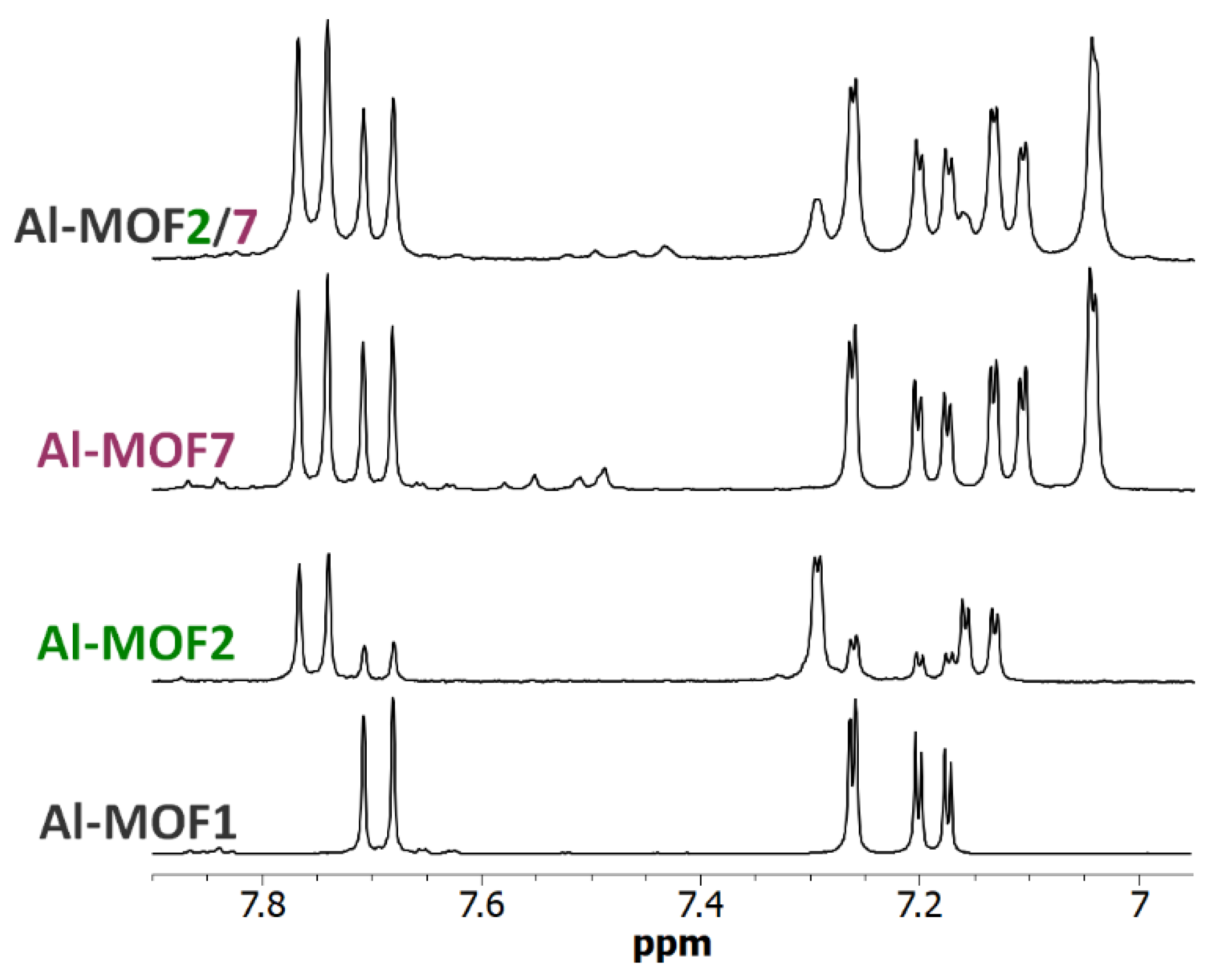

3.3. Polyfunctionalization

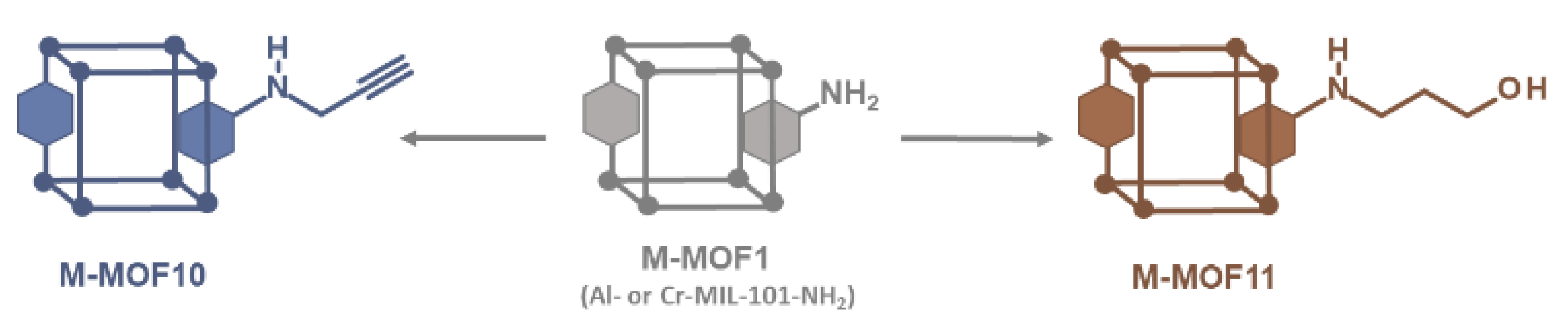

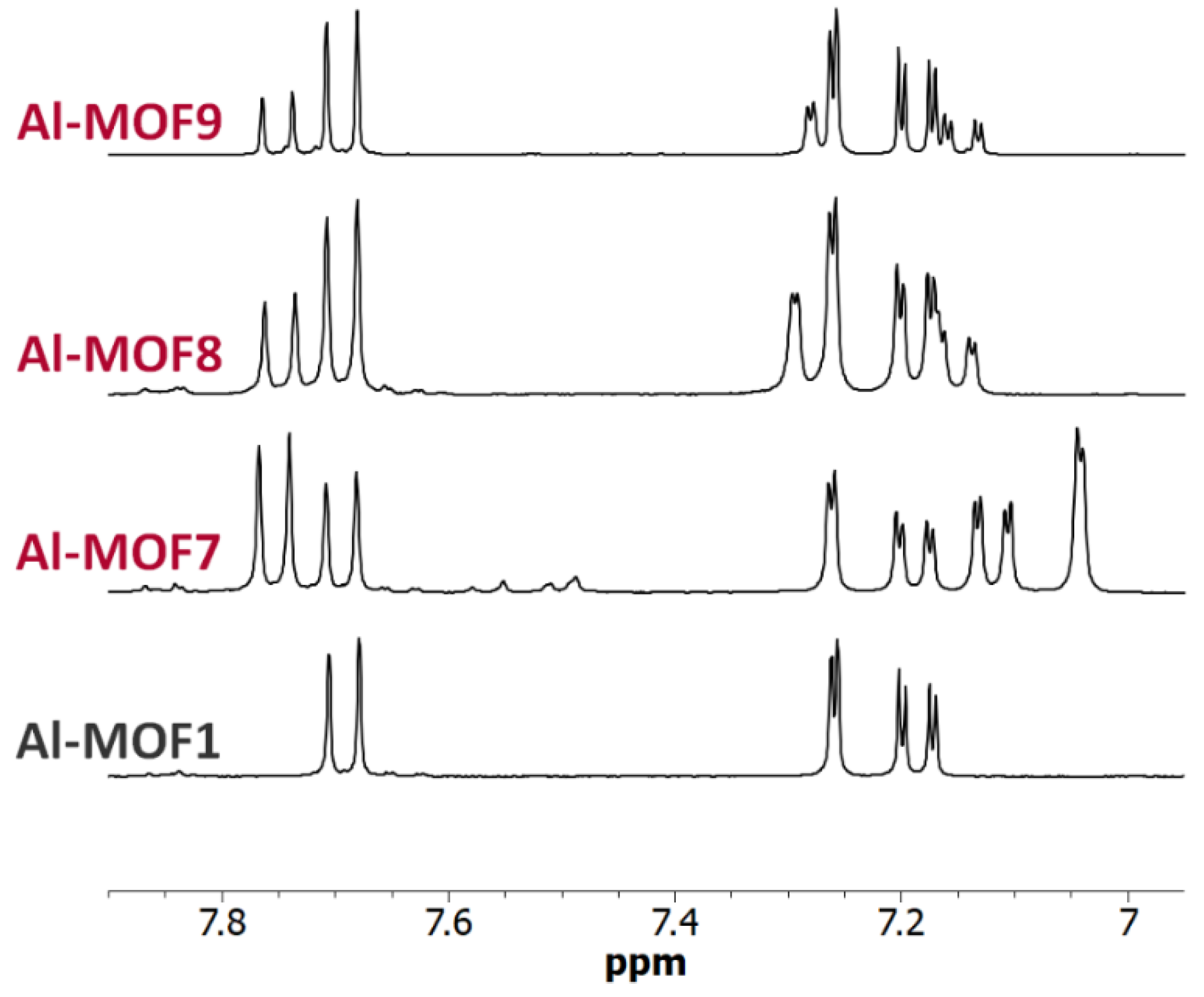

3.4. Postmodification with Other Functional Groups

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tanabe, K.K.; Cohen, S.M. Postsynthetic Modification of Metal–Organic Frameworks—a Progress Report. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 498–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razavi, S.A.A.; Morsali, A. Linker Functionalized Metal-Organic Frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 399, 213023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Wan, S.; Yang, J.; Kurmoo, M.; Zeng, M.-H. Recent Advances in Post-Synthetic Modification of Metal–Organic Frameworks: New Types and Tandem Reactions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 378, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Natarajan, S.; Mani, P.; Pankajakshan, A. Post-Synthetic Modification of Metal–Organic Frameworks Toward Applications. Adv. Funct. Mat. 2021, 31, 2006291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.M.; Rosi, N.L. Postsynthetic Modification of Metal−Organic Frameworks. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 11703–11705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; Lv, D.; Guan, Y.; Yu, S. Post-Synthesis Modification of Metal–Organic Frameworks: Synthesis, Characteristics, and Applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 24519–24550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernt, S.; Guillerm, V.; Serre, C.; Stock, N. Direct Covalent Post-Synthetic Chemical Modification of Cr-MIL-101 Using Nitrating Acid. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 2838–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, S.; Serre, C.; Devic, T.; Horcajada, P.; Marrot, J.; Férey, G.; Stock, N. High-Throughput Assisted Rationalization of the Formation of Metal Organic Frameworks in the Iron(III) Aminoterephthalate Solvothermal System. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 7568–7576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddaoudi, M.; Kim, J.; Rosi, N.; Vodak, D.; Wachter, J.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Systematic Design of Pore Size and Functionality in Isoreticular MOFs and their Application in Methane Storage. Science 2002, 295, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Cohen, S.M. Tandem Modification of Metal-Organic Frameworks by a Postsynthetic Approach. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 4699–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Cohen, S.M. Postsynthetic Covalent Modification of a Neutral Metal−Organic Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 12368–12369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.S.; Whang, D.; Lee, H.; Jun, S.I.; Oh, J.; Jeon, Y.J.; Kim, K. A Homochiral Metal-Organic Porous Material for Enantioselective Separation and Catalysis. Nature 2000, 404, 982–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibay, S.J.; Wang, Z.; Tanabe, K.K.; Cohen, S.M. Postsynthetic Modification: A Versatile Approach Toward Multifunctional Metal-Organic Frameworks. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 7341–7349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkringer, C.; Cohen, S.M. Generating Reactive MILs: Isocyanate- and Isothiocyanate-Bearing MILs through Postsynthetic Modification. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 4644–4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittmann, T.; Siegel, R.; Reimer, N.; Milius, W.; Stock, N.; Senker, J. Enhancing the Water Stability of Al-MIL-101-NH2 via Postsynthetic Modification. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingleson, M.J.; Perez Barrio, J.; Guilbaud, J.-B.; Khimyak, Y.Z.; Rosseinsky, M.J. Framework Functionalisation Triggers Metal Complex Binding. Chem. Commun. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón-Tovar, L.; Rodríguez-Hermida, S.; Imaz, I.; Maspoch, D. Spray Drying for Making Covalent Chemistry: Postsynthetic Modification of Metal–Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savonnet, M.; Bazer-Bachi, D.; Bats, N.; Perez-Pellitero, J.; Jeanneau, E.; Lecocq, V.; Pinel, C.; Farrusseng, D. Generic Postfunctionalization Route from Amino-Derived Metal−Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 4518–4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Chen, L.; Yin, B.; Li, Y. “Click” Post-Functionalization of a Metal–Organic Framework for Engineering Active Single-Site Heterogeneous Ru(III) Catalysts. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 9884–9887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrand, A.; Pastushenko, A.; Lysenko, V.; Geloen, A.; Quadrelli, E.A.; Canivet, J.; Farrusseng, D. Enhanced Ligand-Based Luminescence in Metal–Organic Framework Sensor. ChemNanoMat. 2016, 2, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Xu, L.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Bai, Y.; Liu, H. Post-Synthetic Modification of an Amino-Functionalized Metal–Organic Framework for Highly Efficient Enrichment of N-Linked Glycopeptides. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 10908–10912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Jeong, H.-K. Generation of Covalently Functionalized Hierarchical IRMOF-3 by Post-Synthetic Modification. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 181-182, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.G.; Tanabe, K.K.; Cohen, S.M. Postsynthetic Diazeniumdiolate Formation and NO Release from MOFs. CrystEngComm. 2010, 12, 2335–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, D.; Lee, C.; Uribe-Romo, F.J.; Furukawa, H.; Yaghi, O.M. Ring-Opening Reactions within Porous Metal−Organic Frameworks. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 6387–6389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Xi, F.-G.; Sun, W.; Yang, N.-N.; Gao, E.-Q. Amino- and Sulfo-Bifunctionalized Metal–Organic Frameworks: One-Pot Tandem Catalysis and the Catalytic Sites. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 5753–5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Keenan, L.L.; Burrows, A.D.; Edler, K.J. Synthesis and Post-Synthetic Modification of MIL-101(Cr)-NH2 via a Tandem Diazotisation Process. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 12053–12055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamzah, H.A.; Crickmore, T.S.; Rixson, D.; Burrows, A.D. Post-Synthetic Modification of Zirconium Metal–Organic Frameworks by Catalyst-Free Aza-Michael Additions. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 14491–14496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Li, B.; Liu, K.; Zhang, X.; Zou, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, G.; Shi, Z.; Feng, S. Bifunctional MOF Heterogeneous Catalysts Based on the Synergy of Dual Functional Sites for Efficient Conversion of CO2 Under Mild and Co-catalyst Free Conditions. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015, 3, 23136–23142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ma, D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Shi, Z.; Feng, S.; Zaworotko, M.J.; Ma, S. Dual Functionalized Cages in Metal–Organic Frameworks via Stepwise Postsynthetic Modification. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 4781–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, M.; Fischer, M. Amino-Functionalized Basic Catalysts with MIL-101 Structure. Microporous Mesoporous Mat. 2012, 164, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Kong, C.; Chen, L. Direct Synthesis of Amine-Functionalized MIL-101(Cr) Nanoparticles and Application for CO2 Capture. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 6417–6419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.; Dong, M.; Zhao, T. Advances in Metal-Organic Frameworks MIL-101(Cr). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babaee, S.; Zarei, M.; Sepehrmansourie, H.; Zolfigol, M.A.; Rostamnia, S. Synthesis of Metal–Organic Frameworks MIL-101(Cr)-NH2 Containing Phosphorous Acid Functional Groups: Application for the Synthesis of N-Amino-2-pyridone and Pyrano [2,3-c]pyrazole Derivatives via a Cooperative Vinylogous Anomeric-Based Oxidation. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 6240–6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuah, E.; Toh, S.; Yee, J.; Ma, Q.; Gao, Z. Enzyme Mimics: Advances and Applications. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 8404–8430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nothling, M.D.; Xiao, Z.; Bhaskaran, A.; Blyth, M.T.; Bennett, C.W.; Coote, M.L.; Connal, L.A. Synthetic Catalysts Inspired by Hydrolytic Enzymes. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 168–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).