Introduction

The utilization of glycoluril building units to build up novel macrocycles and new structures has gained the attention of the cucurbituril (CB) research communities[

1] over the past few years owing to their unique advantages in terms of their vulnerability to modification and custom design in the quest for more diverse and potential applications compared to their parent CB macrocycles. Generally, the glycoluril monomer consists of 4 urea N-H motifs and 2 methine hydrogen atoms available for hydrogen bonding (

Scheme 1)

Apart from CB and acyclic CB macrocycles,[

2,

3] several macrocycles were tailored for several specific applications but all of them to date were designed by only linking glycoluril derivatives through methylene bridges, and not the methine positions such as bambusurils,[

4] biotinurils[

5] for anion sensing. Alternating the glycoluril motif with several chromophoric units such as dialkoxybenzene and benzene resulted in expanding the structures of bambusurils[

6] and pillar(calix)aenes,[

7,

8] respectively, yet the new macrocyclic analogs still focused on bridging the NH moieties and not the methine moieties.

Concerning other porous materials, the parent glycoluril unit was utilized to create an organic polymer upon condensation with terephthalic aldehydes once again via the NH bonds for carbon dioxide storage.[

9] Moreover, derivatives of glycoluril molecules were used to build up nanocatalysts for the synthesis of natural henna-based compounds[

10] or molecular clips for the recognition of resorcinol.[

11] In all the reported derivatives, the substituents were only inserted into the NH sites and not the methine positions.

Concerning organic framework chemistry, glycoluril-derived molecular clips were also used to establish a supramolecular organic framework (SOF) for the adsorption and removal of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT).[

12] Also, relevant to SOF, the known cyclodextrin macrocycle was incorporated into the structure of polyoxometalate-based SOF as a separator in Li-S batteries. Yet, neither CB nor its building unit glycoluril has been incorporated in any organic framework structures so far, to the best of our knowledge.

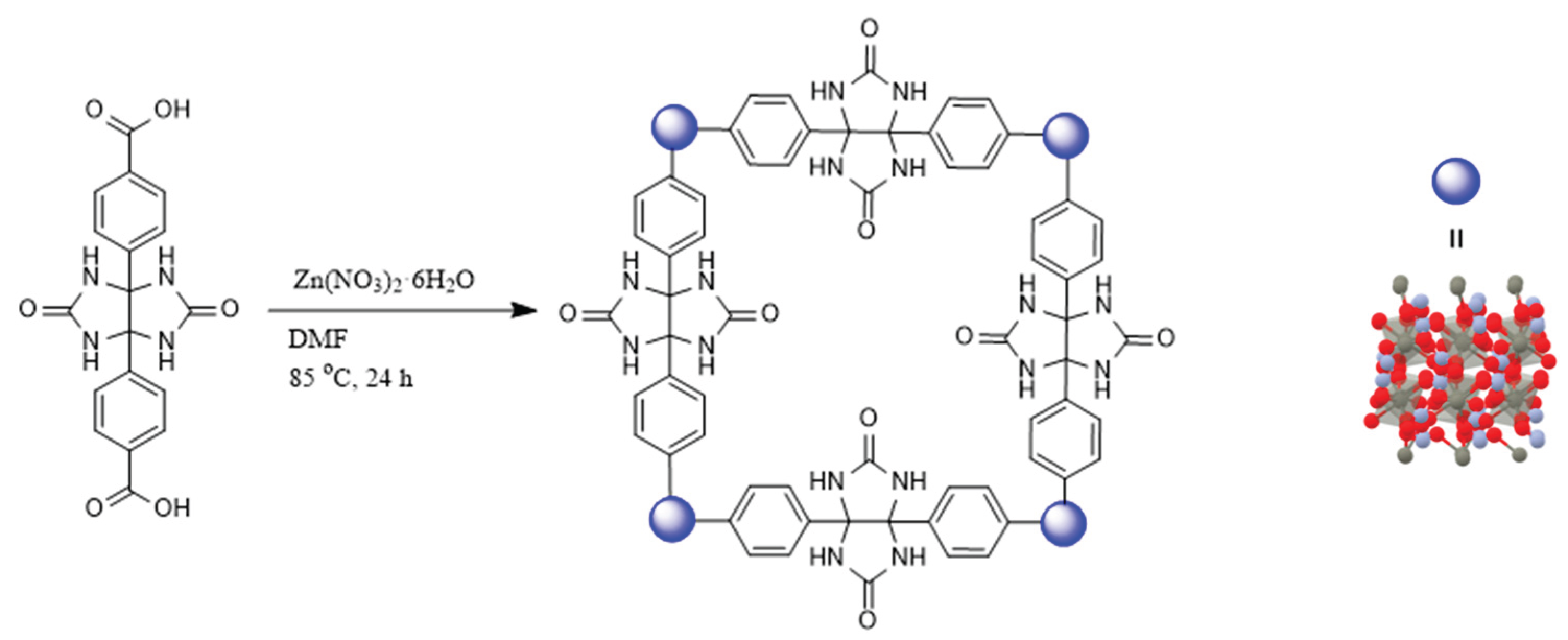

Unlike all reported structures to date, which connected different numbers and derivatives of glycoluril building blocks via their NH sides, forming structures with methylene bridges, we decided to link the glycoluril units through their methine hydrogen atoms, creating a metal-organic framework (MOF) and leaving the 4 NH moieties with a curved glycoluril backbone available for molecular recognitions. Herein, we unprecedently insert 2 benzoic acid groups into the methine bond to link the glycoluril building blocks to zinc metals generating a novel metal-organic framework (

Scheme 1). To the best of our knowledge, this or any other glycoluril-based metal-organic framework has never been achieved.

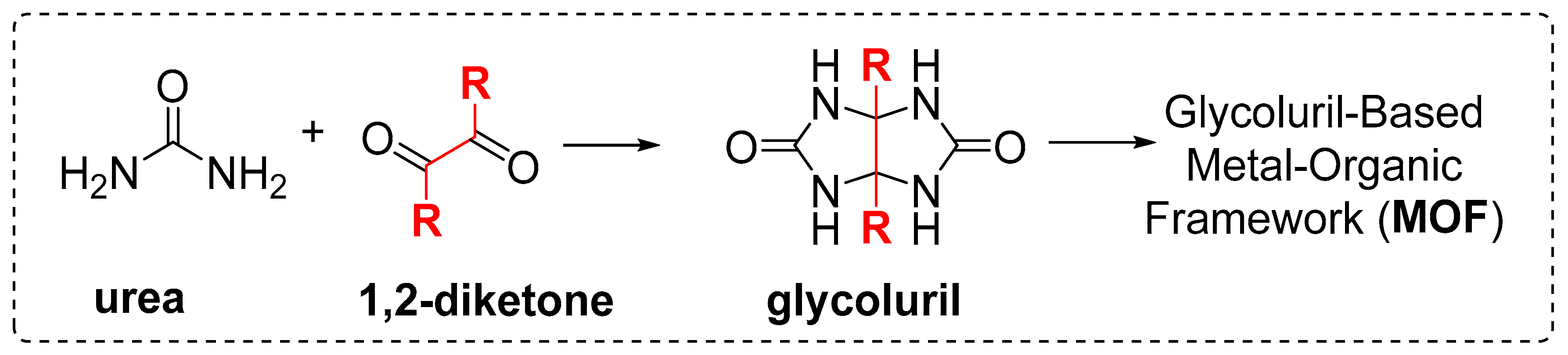

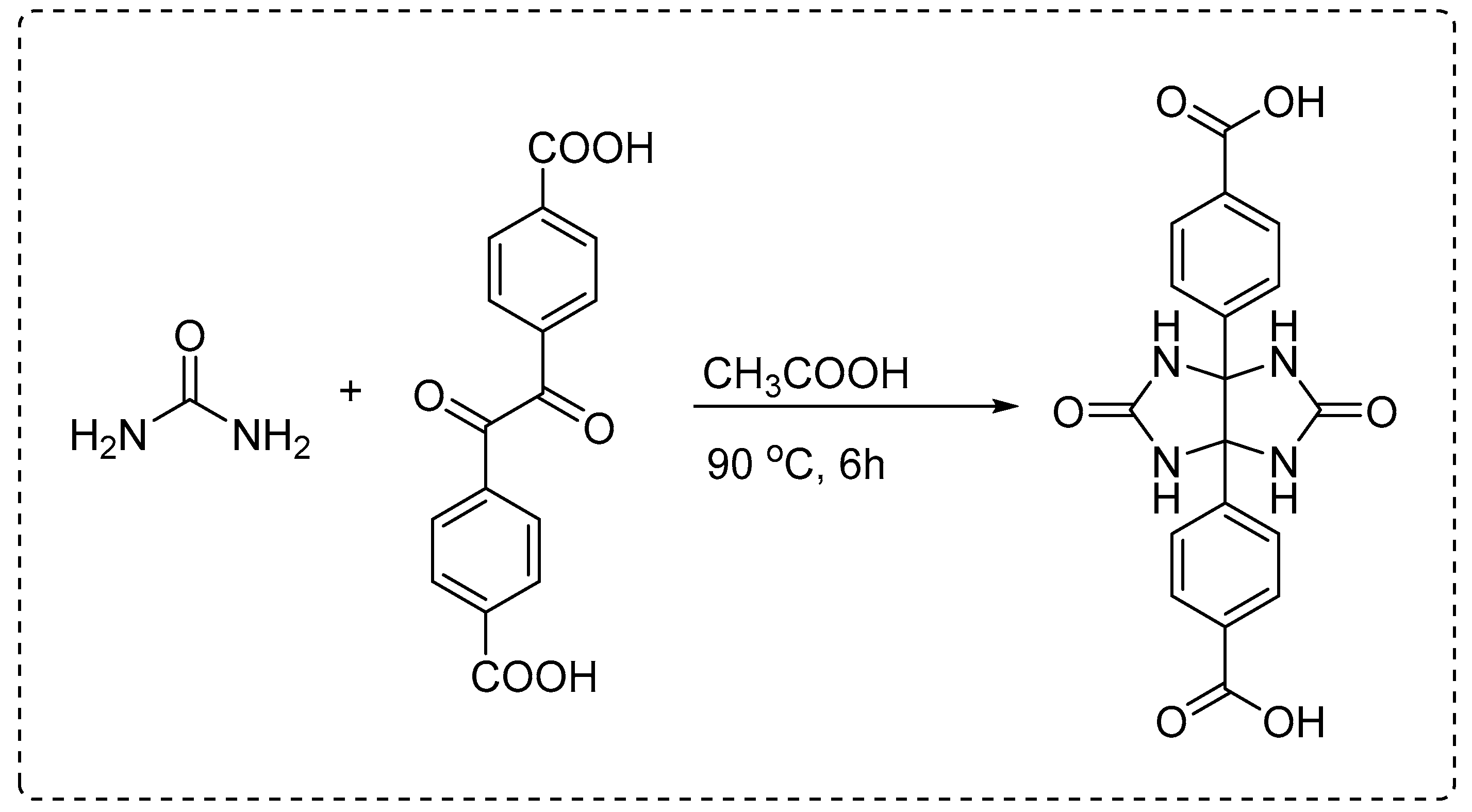

The following procedure was followed for the one-step synthesis of a glycoluril-based dicarboxylic acid linker (Scheme 2).

Urea reacts with 4,4'-dioxo-[1,1'-biphenyl]-3,3'-dicarboxylic acid (a 1,2-diketone derivative) in glacial acetic acid at 90 °C for 6 hours to form 4,4'-(2,5-dioxotetrahydroimidazo[4,5-d]imidazole-3a,6a(1H,4H)-diyl)dibenzoic acid. The reaction proceeds via cyclocondensation, yielding a rigid linker with four free NH groups and two terminal carboxylic acids suitable for MOF coordination.

To synthesize 4,4'-(2,5-dioxotetrahydroimidazo[4,5-d]imidazole-3a,6a(1H,4H)-diyl)dibenzoic acid with free NH groups, urea (1.20 g, 20 mmol) and 4,4′-dioxo-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3,3′-dicarboxylic acid (1.66 g, 10 mmol), a 1,2-dicarbonyl aromatic compound, were dissolved in 20 mL of glacial acetic acid. The mixture was heated under reflux at 90 °C for 6 hours with continuous stirring. Upon completion, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature, and the resulting white precipitate was collected by vacuum filtration, washed thoroughly with cold water and ethanol, and dried under vacuum. The crude product was recrystallized from a 1:1 ethanol–water mixture to yield the final glycoluril-based dicarboxylic acid linker as a white crystalline solid. The product was obtained in 65–75% yield and confirmed by FTIR (indicating intact NH and carbonyl groups), ¹H NMR (showing characteristic glycoluril and aromatic signals), and elemental analysis (

Scheme 2).

¹H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d₆, δ, ppm): 4.72 (s, 2H, bridgehead CH), 7.62–8.05 (m, 8H, Ar–H), 10.88 (brs, 4H, NH, exchanges with D₂O), 12.90 (brs, 2H, COOH, exchanges with D₂O).

¹³C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d₆, δ, ppm): 82.0 (bridgehead CH), 127.8, 128.9, 129.9, 130.6, 143.4 (Ar–C), 160.9 (C=O, urea core), 167.3 (C=O, COOH).

FTIR (KBr, cm⁻¹): 3305 (br, N–H), 3060 (Ar–C–H), 1698 (C=O, COOH), 1670 (C=O, urea), 1598 (C=C, aromatic), 1275 (C–N), 770 (Ar–C–H bending).

The reaction proceeds through a classic cyclocondensation mechanism between urea and a 1,2-dicarbonyl compound under acidic and thermal conditions. Initially, the nucleophilic amino groups of urea attack the electrophilic carbonyl carbons of the 1,2-diketone moiety. This forms a series of tetrahedral intermediates, which then undergo dehydration (loss of water) to generate C–N bonds. The condensation of two urea molecules with the adjacent carbonyls results in the formation of a bicyclic imidazo[4,5-d]imidazole (glycoluril) core. The reaction takes place under glacial acetic acid reflux at 90 °C, which serves both as a mild acid catalyst and solvent, facilitating cyclization and promoting the elimination of water. The presence of carboxylic acid groups on the aromatic rings does not interfere with the cyclization, allowing them to remain intact and available for post-synthetic functionalization or metal coordination in MOF construction. Importantly, the NH groups on the glycoluril core remain unsubstituted, as they are not involved in further condensation reactions, resulting in a final product that features four free NH groups and two terminal carboxylic acid groups. The structure is highly rigid and symmetrical, making it an ideal organic linker for constructing MOFs with predictable geometry and robust connectivity.

The spectroscopic data obtained confirm the successful synthesis and structural integrity of the glycoluril-based dicarboxylic acid linker. The ¹H NMR spectrum displayed characteristic signals including a singlet at δ 4.76 ppm corresponding to the bridgehead methine protons of the glycoluril core, a multiplet between δ 7.62–8.05 ppm attributable to aromatic protons, and broad singlets at δ 10.88 and 12.90 ppm corresponding to the NH and COOH protons, respectively, both of which exchanged with D₂O—further confirming the presence of free secondary amines and carboxylic acid groups. The ¹³C NMR spectrum showed the expected signals for the bridgehead carbon (δ ~61.4 ppm), aromatic carbons (δ 127–143 ppm), and two distinct carbonyl environments—urea-type (δ 160.9 ppm) and carboxylic acid (δ 167.3 ppm). These data are consistent with the proposed structure featuring an intact glycoluril core and unreacted functional groups. The FTIR spectrum reinforced these assignments with broad N–H stretching at 3305 cm⁻¹, strong C=O absorptions near 1698 and 1670 cm⁻¹ for the acid and urea carbonyls, respectively, and C–N stretching at 1275 cm⁻¹. Additionally, elemental analysis values were in close agreement with theoretical calculations, supporting high purity and correct molecular composition. Collectively, the data confirm the formation of a symmetric, rigid glycoluril-based linker bearing free NH and COOH groups, making it suitable for coordination-driven applications such as MOF assembly.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of NS-MOF (Zn).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of NS-MOF (Zn).

The synthesis of NS-MOF (Zn) was successfully achieved using a solvothermal method involving the reaction of a glycoluril-based linker with zinc nitrate hexahydrate in dimethylformamide (DMF) at 85 °C for 24 hours. This method allowed for the controlled formation of a crystalline MOF, as evidenced by the white solid obtained after cooling and filtration. The use of sonication prior to solvothermal treatment likely improved solubility and homogeneity of the reactants, facilitating efficient coordination between zinc ions and the glycoluril-based organic linker. The structural model shown in the scheme illustrates a high degree of symmetry and porosity, characteristics that are hallmarks of MOFs and crucial for applications in gas storage, separation, and catalysis. The presence of the blue spheres representing Zn(II) ions at the vertices of the framework confirms their role as coordination centers, linking the organic ligands into a periodic network. Additionally, the 3D structural representation highlights the robust coordination environment and the extended framework that results from the reaction conditions employed. The clear network connectivity and structural integrity suggest good crystallinity, which is desirable for MOF performance and further functional studies. Overall, the straightforward synthesis conditions—mild temperature, readily available reagents, and standard solvents—make this an accessible route to prepare NS-MOF (Zn). The vacuum filtration and washing steps ensure the removal of unreacted precursors and solvent residues, enhancing the purity and potential usability of the final MOF material in downstream applications.

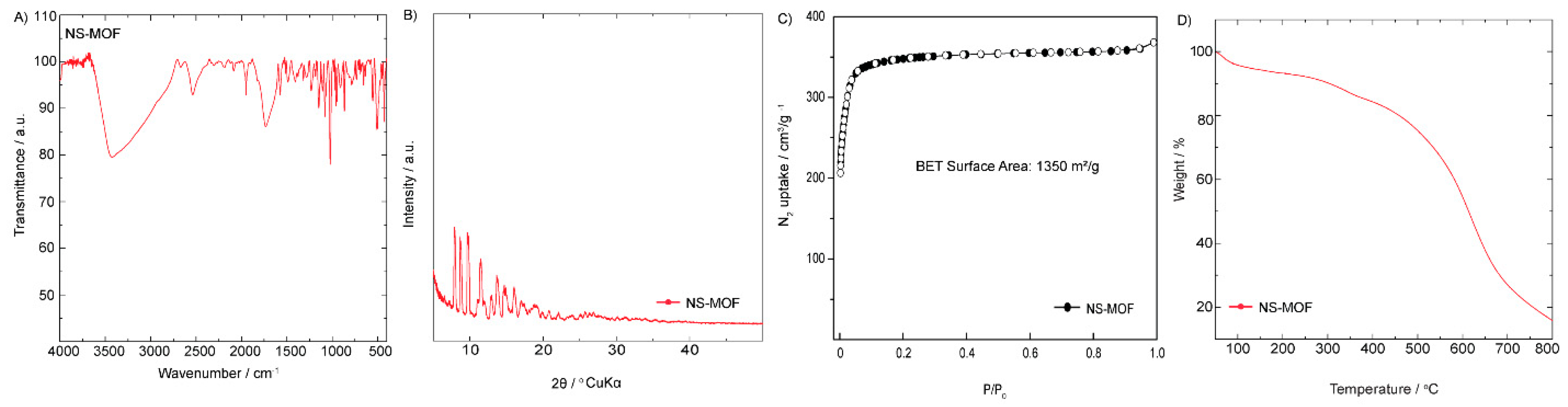

The structural and physicochemical properties of NS-MOF (Zn) were thoroughly evaluated using FTIR, PXRD, BET surface area analysis, and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) (

Figure 1), confirming the successful synthesis and functional robustness of the framework.

The FTIR spectrum (

Figure 1A) shows prominent absorption bands corresponding to the characteristic functional groups of the organic linker. The broad band around 3300 cm⁻¹ suggests the presence of N–H stretching vibrations, while the peaks near 1680 cm⁻¹ and 1600 cm⁻¹ are attributed to C=O and C=N stretches, respectively. These results confirm the incorporation of the glycoluril moieties and coordination with Zn(II) ions. The PXRD pattern (

Figure 1B) displays sharp and distinct diffraction peaks, indicating the crystalline nature of NS-MOF (Zn). The pattern is consistent with a highly ordered framework structure, verifying successful MOF formation rather than amorphous byproducts. This crystallinity is essential for defining pore structure and ensuring reproducibility in applications. The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm (

Figure 1C) exhibits a typical type I profile, indicative of microporosity. The calculated Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area is approximately 1350 m²/g, which reflects a highly porous architecture. Such a large surface area is desirable for applications in gas storage, separation, and catalysis, offering abundant active sites and internal volume. Thermogravimetric analysis (

Figure 1D) reveals that NS-MOF (Zn) remains stable up to approximately 600 °C, with gradual weight loss attributable to solvent removal and decomposition of the organic linker beyond this temperature. This thermal stability suggests the framework is suitable for high-temperature applications and enhances its durability under operational conditions. Overall, these characterization results confirm that NS-MOF (Zn) possesses the structural, thermal, and surface properties necessary for practical applications in areas such as gas sorption, catalysis, and environmental remediation.

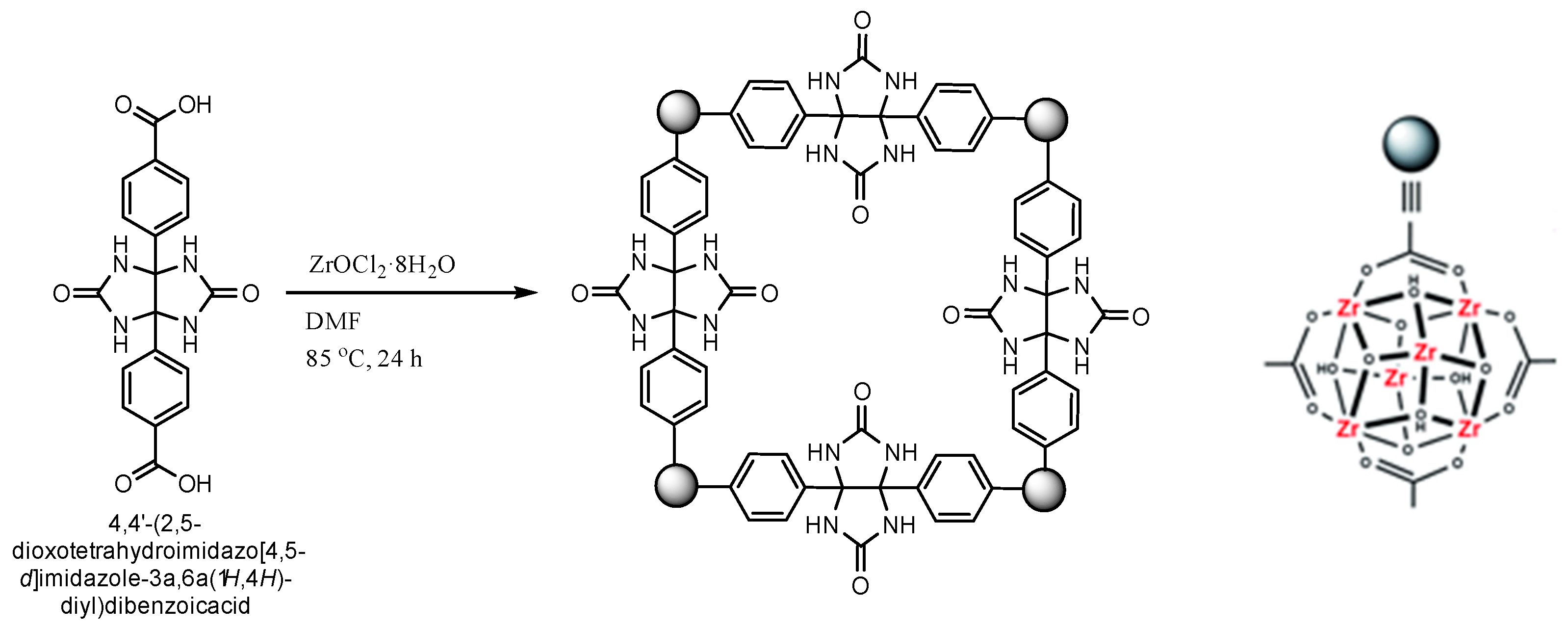

The synthesis of NS-MOF (Zr) was successfully carried out using a solvothermal approach involving the reaction of a glycoluril-based linker with zirconium(IV) chloride (ZrOCl₂·8H₂O) in DMF at 85 °C for 24 hours (

Scheme 4).

This strategy yielded a white crystalline solid, indicative of the formation of a structured MOF. The mild reaction conditions and the use of a Teflon-lined autoclave enabled controlled coordination of Zr(IV) ions with the multidentate glycoluril linker, fostering the assembly of a well-defined MOF architecture. The schematic representation shows a symmetric, square-grid network in which Zr(IV) ions serve as nodes that coordinate with the oxygen atoms of the linker, forming a robust 3D framework. The structural model illustrates the high connectivity of the Zr clusters, which is typical of Zr-based MOFs due to the strong metal–ligand bonding and the ability of Zr to form stable multinuclear clusters. The coordination geometry, visualized in the cluster model on the right, highlights the formation of Zr₆-oxo clusters, which are known to impart high thermal and chemical stability to MOFs. This stability makes NS-MOF (Zr) a promising candidate for applications under harsh conditions, such as catalysis, gas adsorption, and drug delivery. In comparison to the Zn-based analog, the Zr-based MOF may offer enhanced stability and rigidity due to the stronger Zr–O coordination bonds. This makes NS-MOF (Zr) particularly attractive for applications where long-term structural integrity and resistance to degradation are essential. Overall, the synthesis method employed here demonstrates a reliable and reproducible route to access Zr-based MOFs from glycoluril-derived linkers. The combination of structural integrity, crystallinity, and the potential for tunable porosity positions NS-MOF (Zr) as a versatile platform for functional material development.

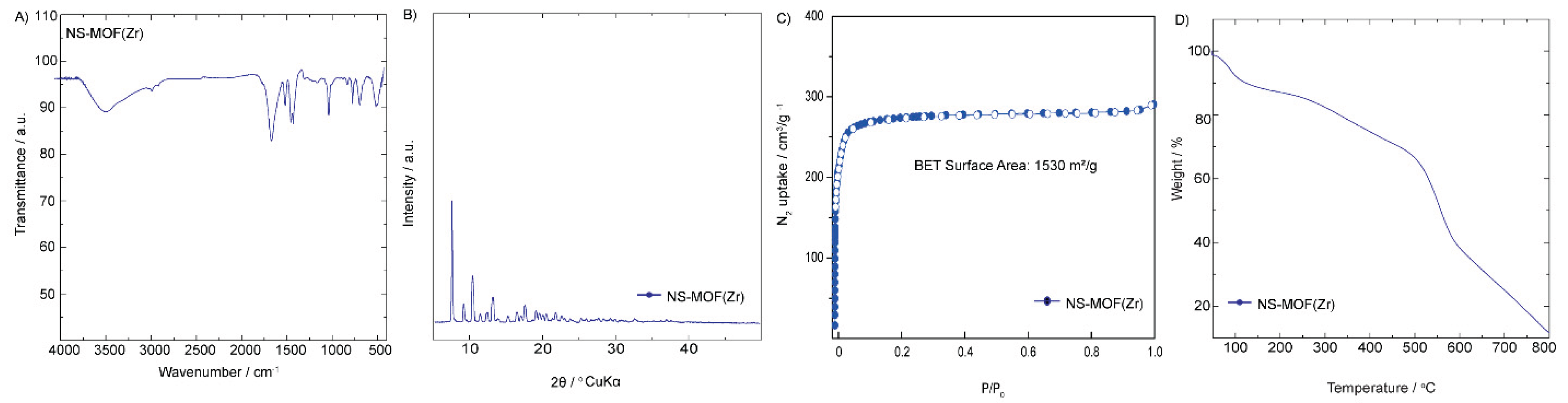

Comprehensive characterization of NS-MOF (Zr) confirms the successful synthesis and desirable structural and functional properties of the zirconium-based metal-organic framework (

Figure 2).

The FTIR spectrum (

Figure 2A) shows distinct absorption bands associated with key functional groups of the glycoluril-based linker and coordination with Zr(IV). The broad peak around 3300 cm⁻¹ is attributed to N–H stretching, while strong absorptions near 1680 cm⁻¹ and 1600 cm⁻¹ correspond to C=O and C=N stretches, indicating intact organic framework connectivity post-synthesis. The PXRD pattern (

Figure 2B) reveals sharp and well-defined diffraction peaks, consistent with a highly crystalline material. The peak positions and intensities suggest a periodic structure with long-range order, characteristic of a robust Zr-based MOF network. This crystallinity is essential for maintaining pore structure and consistent physical properties across batches. Nitrogen adsorption–desorption analysis (

Figure 2C) displays a type I isotherm, typical of microporous materials. The calculated BET surface area of 1530 m²/g exceeds that of the Zn-based analog, highlighting the superior porosity and potential for guest molecule accommodation. The high surface area is indicative of well-developed porosity, making NS-MOF (Zr) a strong candidate for applications in gas adsorption, separation, and catalysis. Thermogravimetric analysis (

Figure 2D) demonstrates the thermal stability of NS-MOF (Zr) up to approximately 600 °C. The initial weight loss below 150 °C is likely due to desorption of physically adsorbed solvents. Beyond this, gradual decomposition of the organic linker occurs, with a final residue suggestive of zirconium oxide formation. This thermal robustness is a notable advantage of Zr-based MOFs and supports their use in high-temperature processes. In summary, the FTIR, PXRD, BET, and TGA results collectively validate the successful formation of a highly crystalline, porous, and thermally stable Zr-MOF. These characteristics position NS-MOF (Zr) as a promising material for advanced applications in gas storage, sensing, and catalysis under demanding conditions.

One of the key advantages of this linker is its ability to coordinate effectively with a range of metal ions, particularly Zn²⁺ and Zr⁴⁺. The two carboxylic acid groups act as bidentate ligands, enabling the formation of extended coordination polymers through strong metal–oxygen bonds. In Zr-based MOFs, the carboxylates can bridge Zr₆-oxo clusters, contributing to the formation of highly stable, chemically resistant structures. These Zr-MOFs, such as NS-MOF(Zr), are known for their exceptional thermal stability (up to ~600 °C) and high resistance to chemical degradation, traits that are highly desirable for industrial applications. Moreover, the linker contributes significantly to the framework's porosity and surface area. Its extended geometry allows for wide pore channels, and its rigid aromatic system prevents pore collapse, which can occur with more flexible linkers. This is evident in the observed high BET surface area of over 1500 m²/g for NS-MOF(Zr), enabling efficient gas storage and molecular separation.

The new glycoluril-based linker in the present work is of central importance in the synthesis of advanced MOFs for the following reasons:

The importance of the glycoluril-based linker in MOF synthesis lies in its unique combination of structural rigidity, functional versatility, and chemical robustness, all of which contribute significantly to the formation and properties of the resulting framework. This particular linker contains a fused imidazo[4,5-d]imidazole (glycoluril) core flanked by two benzoic acid groups, providing both coordination functionality and a rigid backbone essential for promoting crystallinity and directional growth in MOFs. The rigid and pre-organized nature of the linker prevents structural collapse and ensures the formation of well-ordered porous networks with predictable topology.

Specifically, the amide and carbonyl groups in the glycoluril core introduce polar functionality within the pores, which can enhance host–guest interactions, making the material attractive for applications in adsorption, sensing, and selective catalysis.

Another noteworthy feature of this linker is its potential for post-synthetic modification (PSM). The nitrogen-containing glycoluril core provides sites that could be chemically modified without disrupting the overall framework, enabling fine-tuning of properties such as hydrophilicity, catalytic activity, or drug-loading capability. This makes the linker not just a structural scaffold but also a tunable component for developing multifunctional materials.

In summary, we have successfully constructed a novel class of MOF upon distinctly inking derivatives of glycoluril units via their methine groups. This approach has not been realized in literature. The rigid structure, multidentate coordination sites, chemical functionality, and stability-promoting characteristics of the new linker allow for the creation of crystalline, porous, and thermally robust frameworks. These properties collectively position this linker as a valuable tool in the development of MOFs for a wide range of applications, from gas storage and separation to catalysis and biomedical delivery systems.