Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

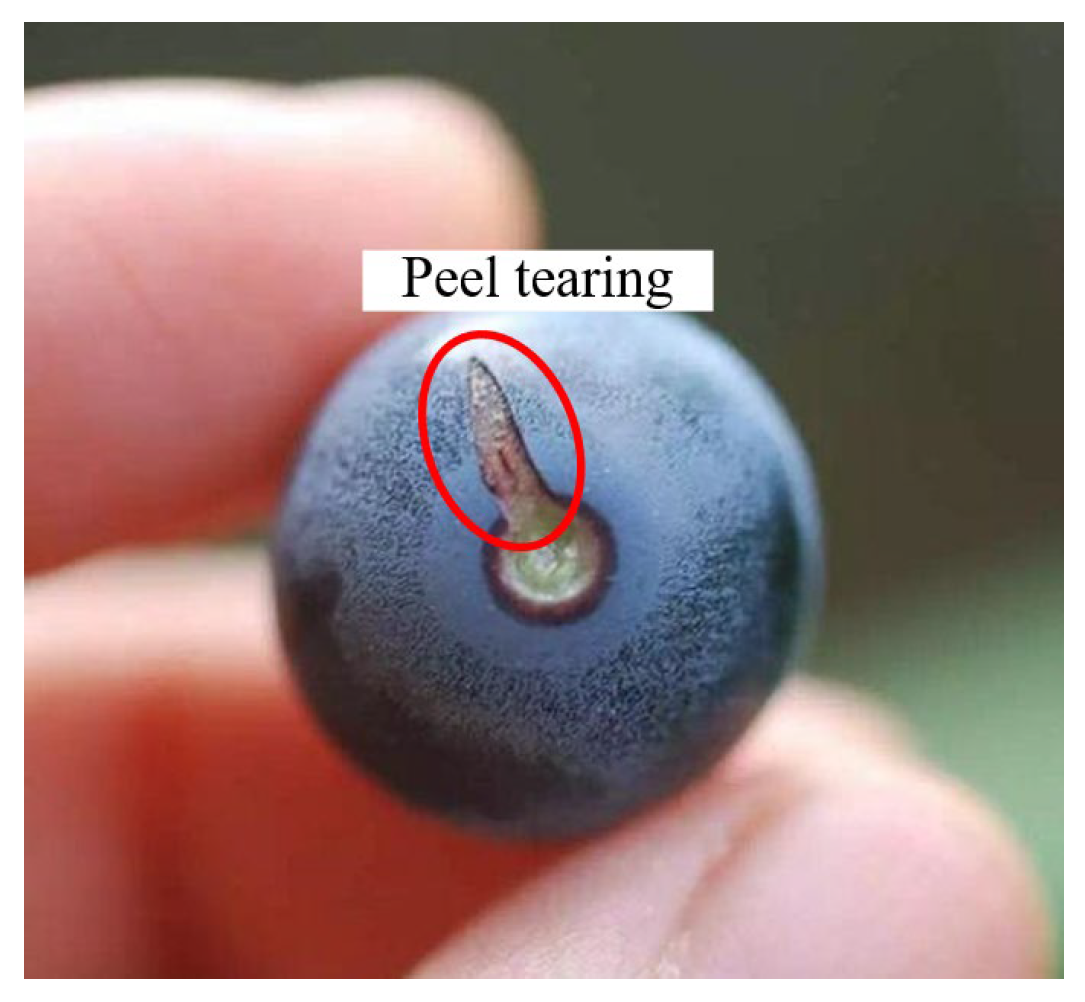

1. Introduction

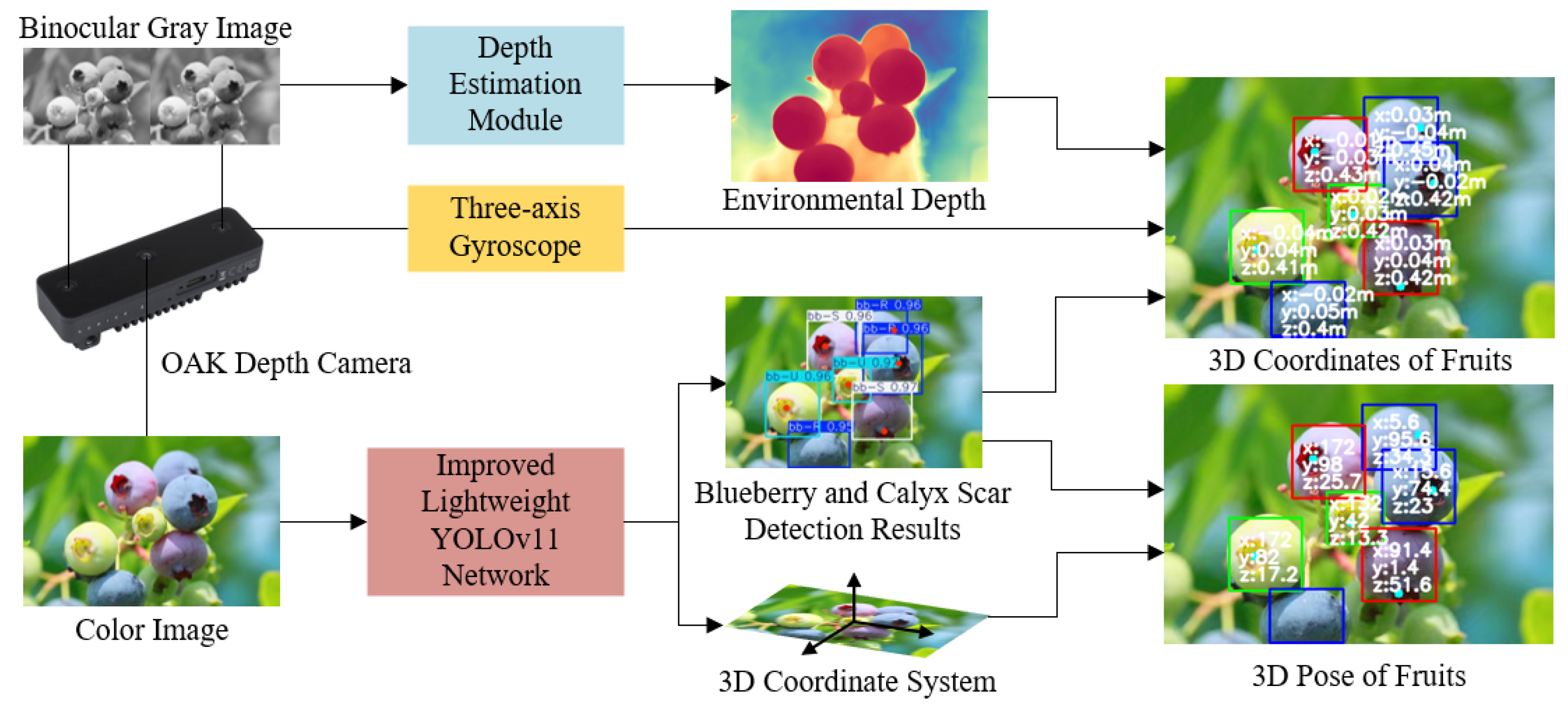

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Blueberry and Calyx Scar Detection Dataset

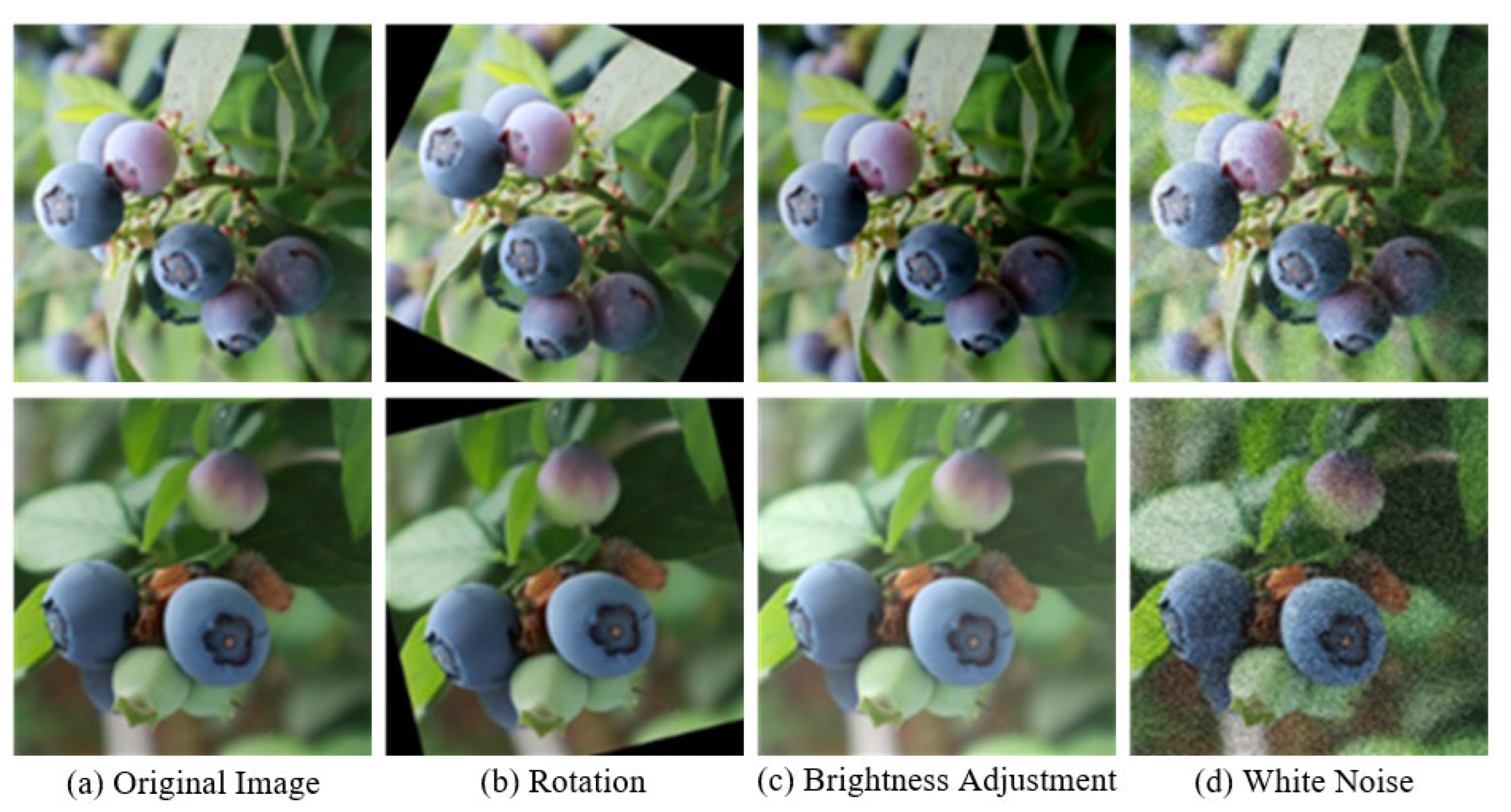

2.1.1. Collection and Partition of Blueberry Images

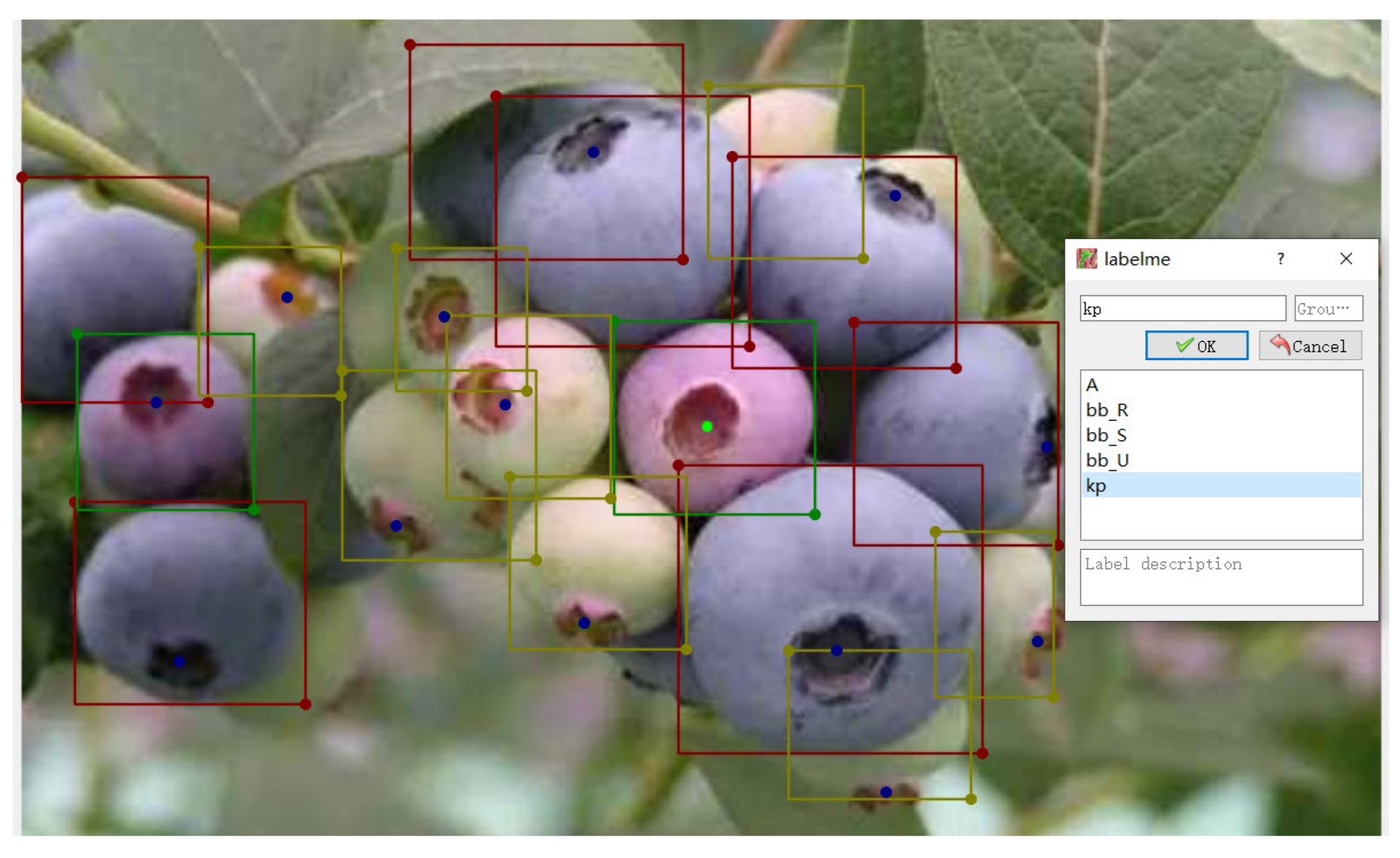

2.1.2. Data Annotations

2.2. Blueberry and Calyx Scar Detection Network

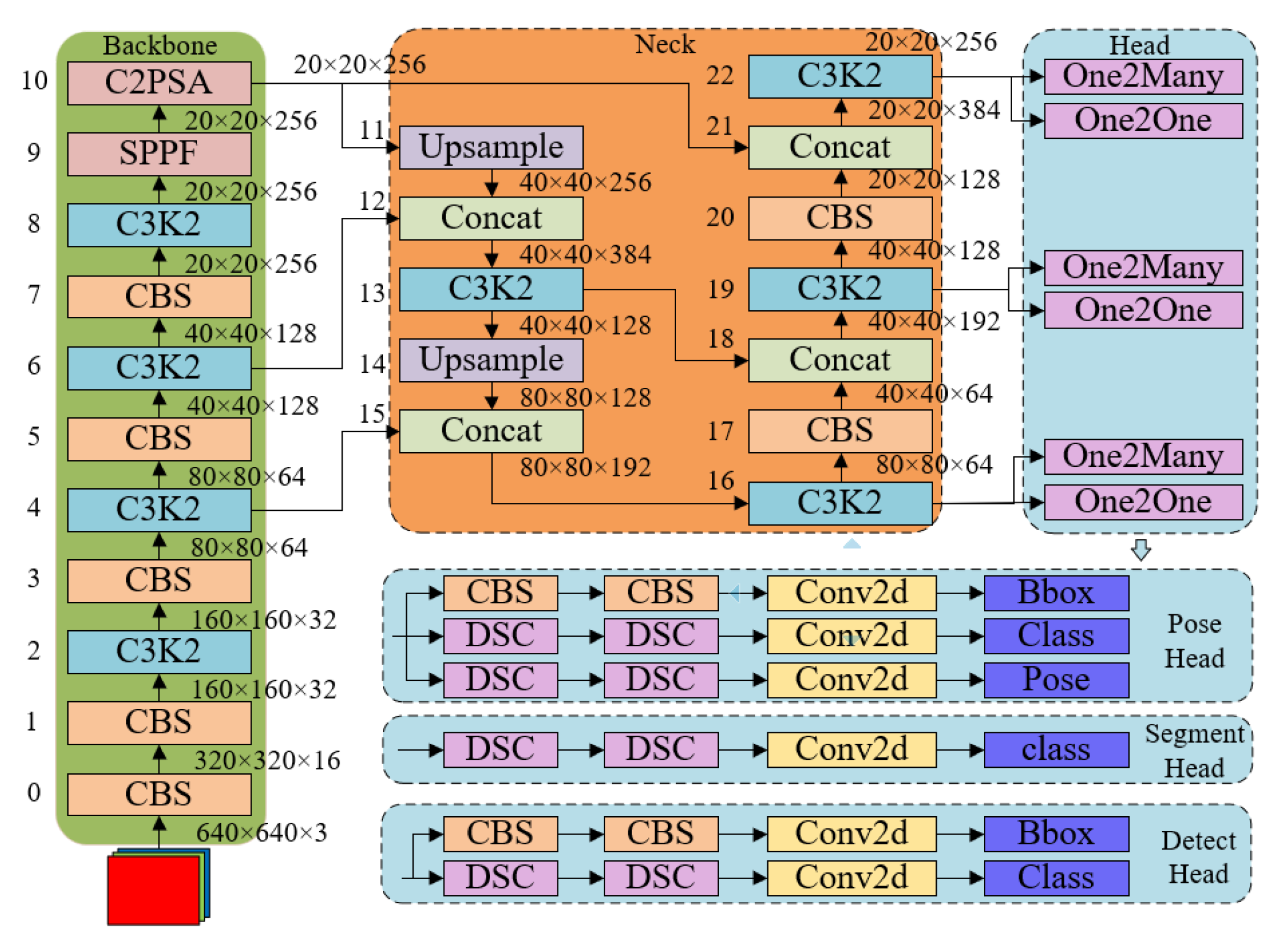

2.2.1. Basic Structure of the YOLOv11n Network

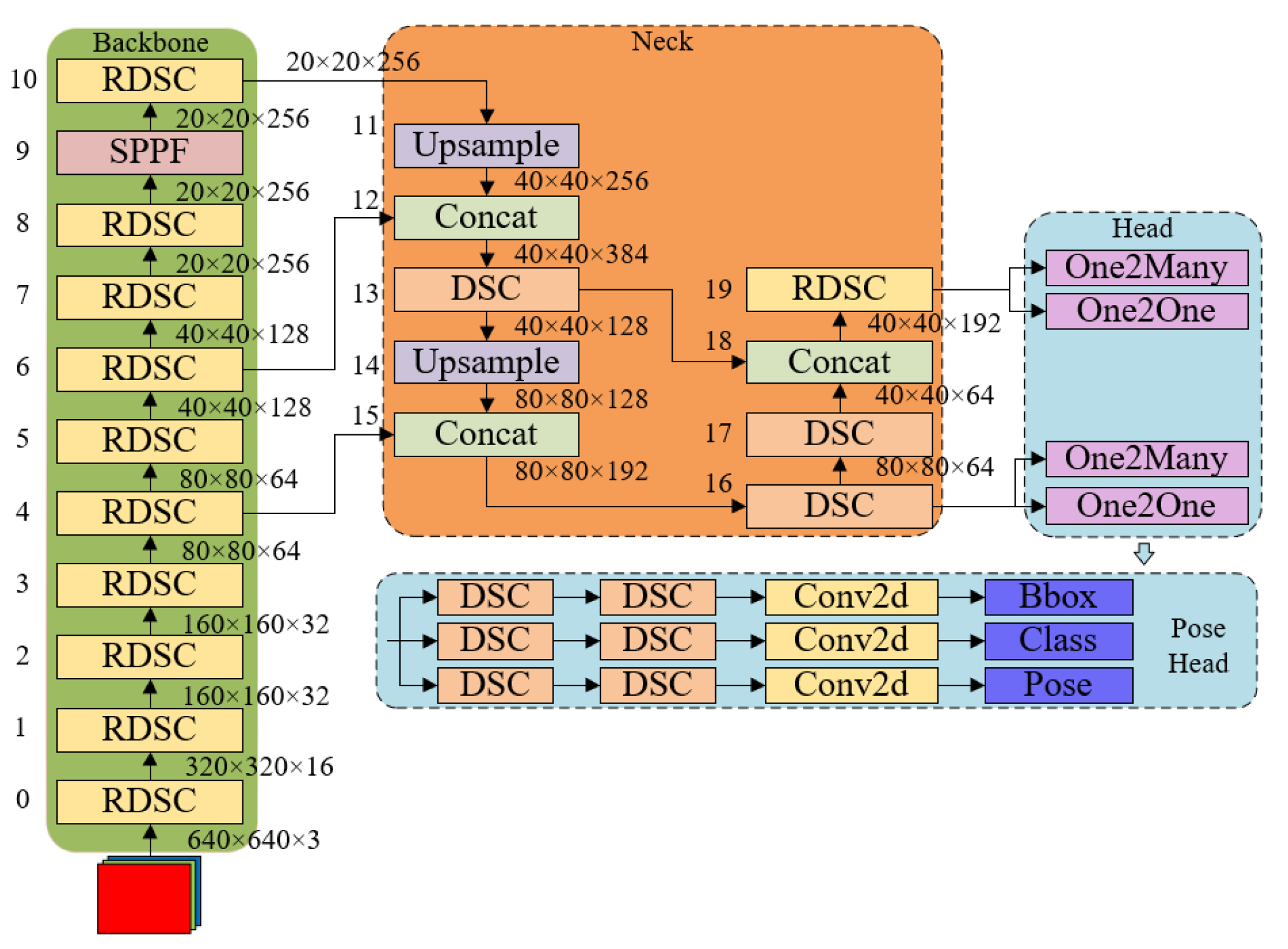

2.2.2. Improved Lightweight YOLOv11 Network for Blueberry and Calyx Scar Detection

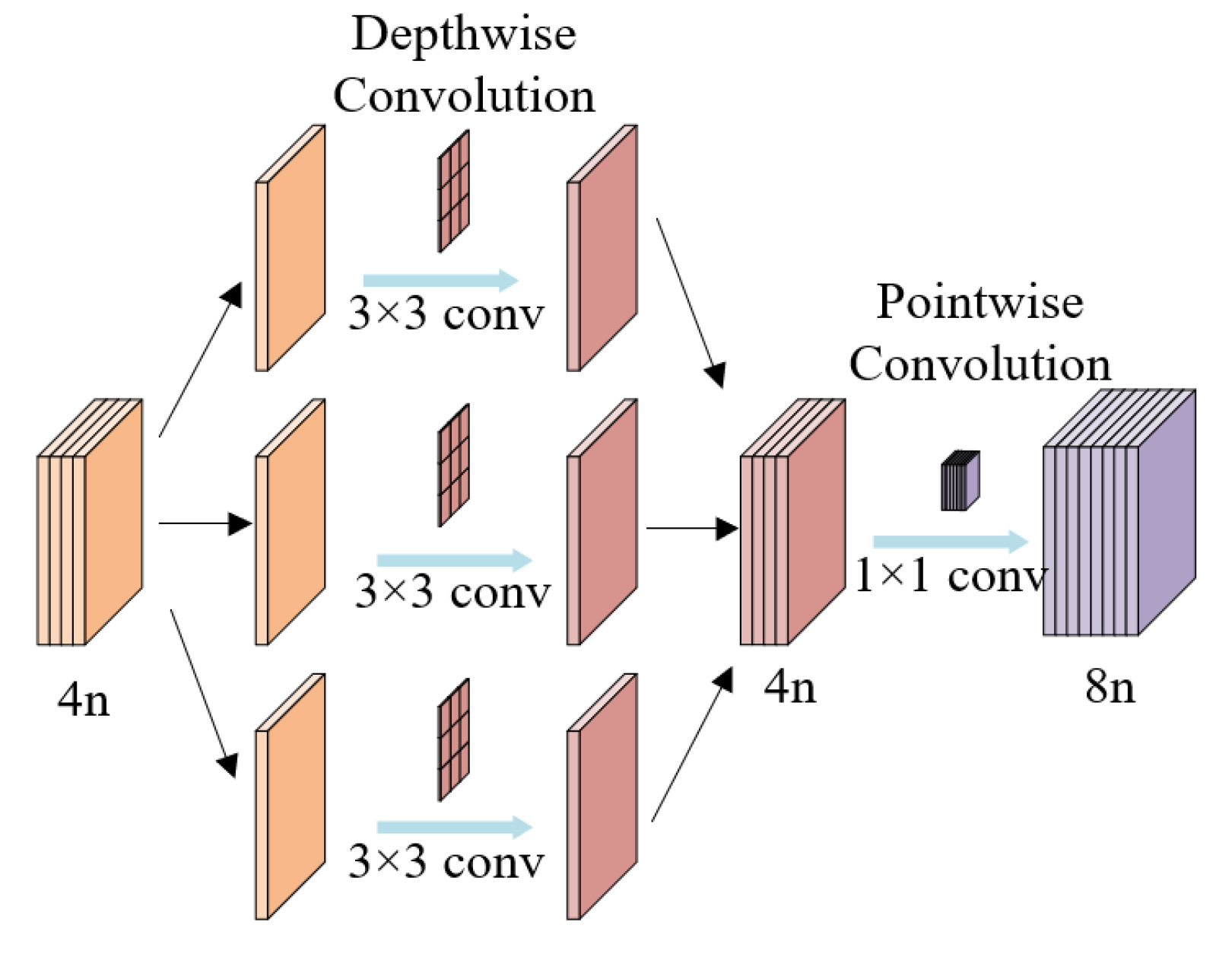

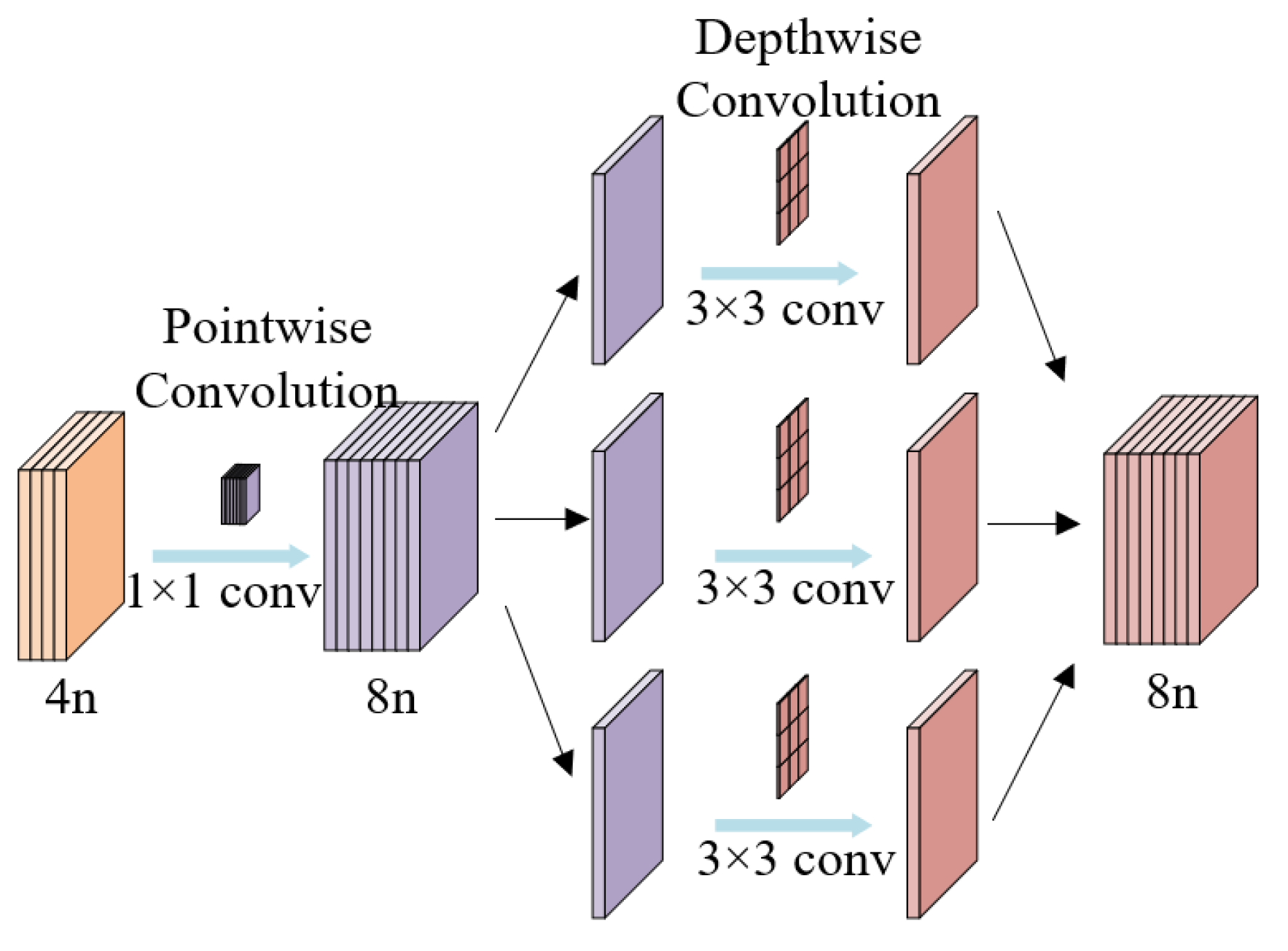

- Proposing an improved depth-wise separable convolution (DSC) module to replace the CBS and C3K2 modules.

- Removing the attention mechanism module C2PSA at the end of the Backbone network.

- Retaining only the relatively large scale outputs of features with 80 × 80 pixels and 40 × 40 pixels.

2.3. 3D Spatial Localization and Pose Calculation of Blueberry Fruits

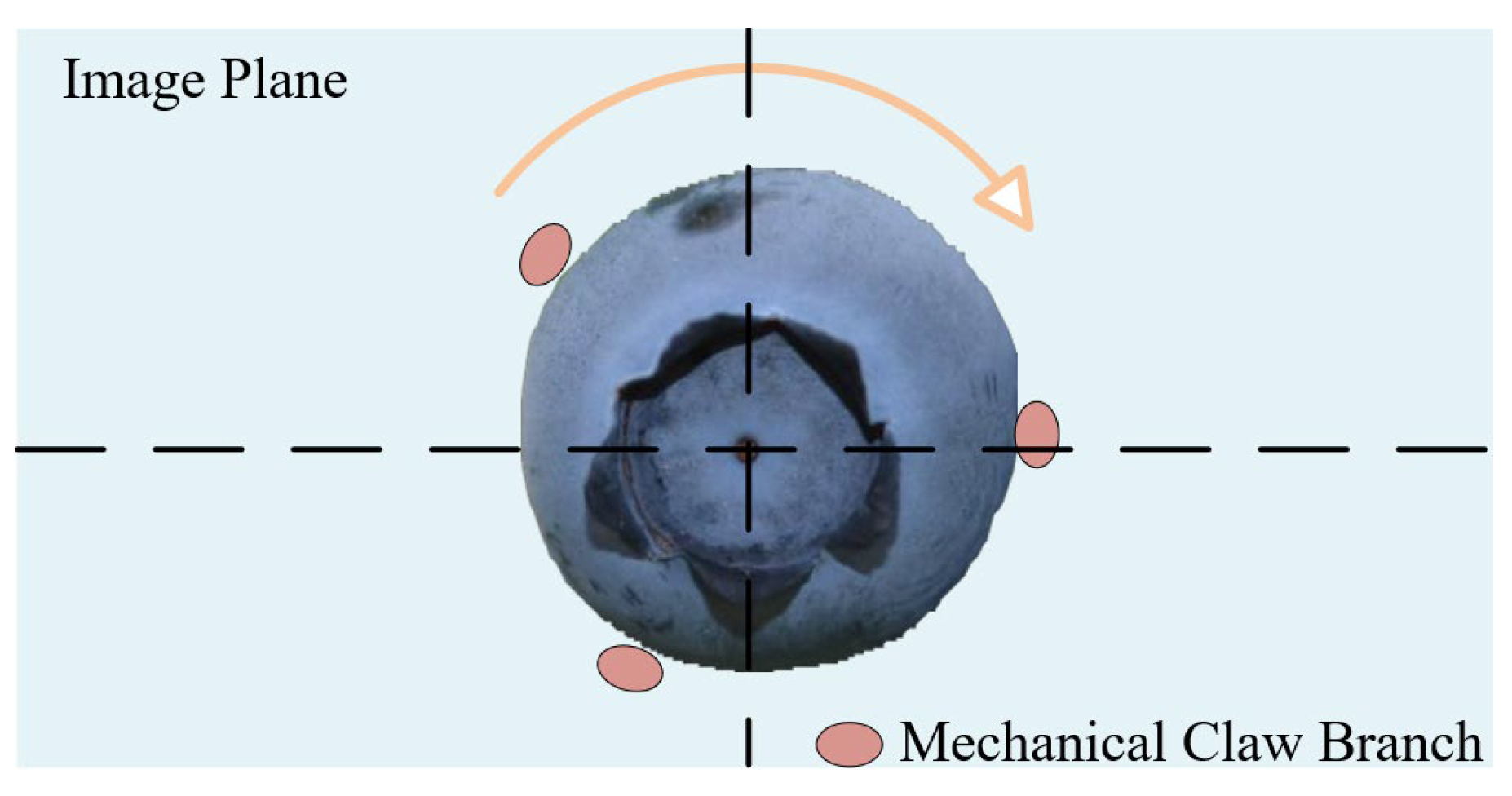

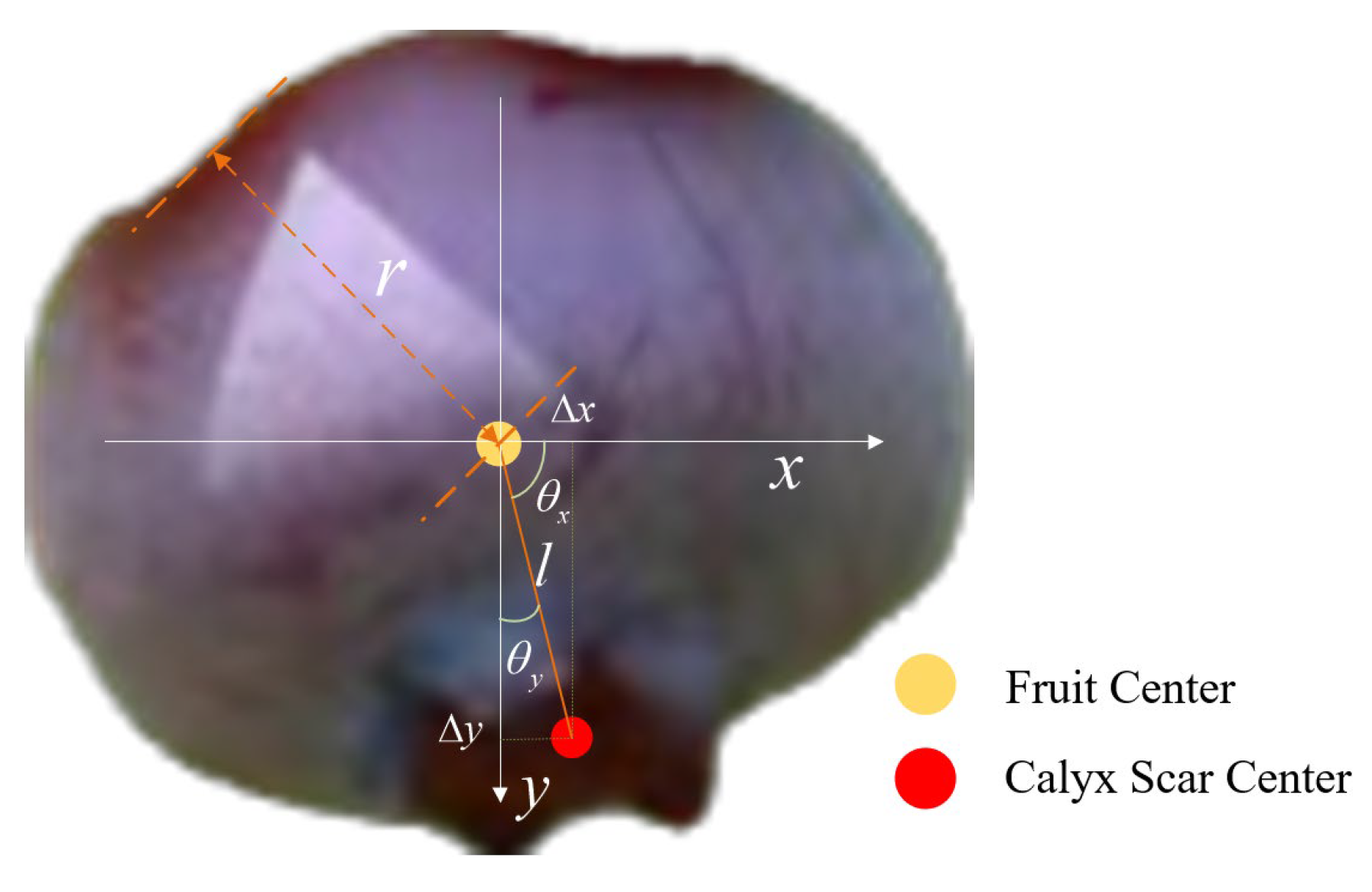

2.3.1. 3D Pose Calculation

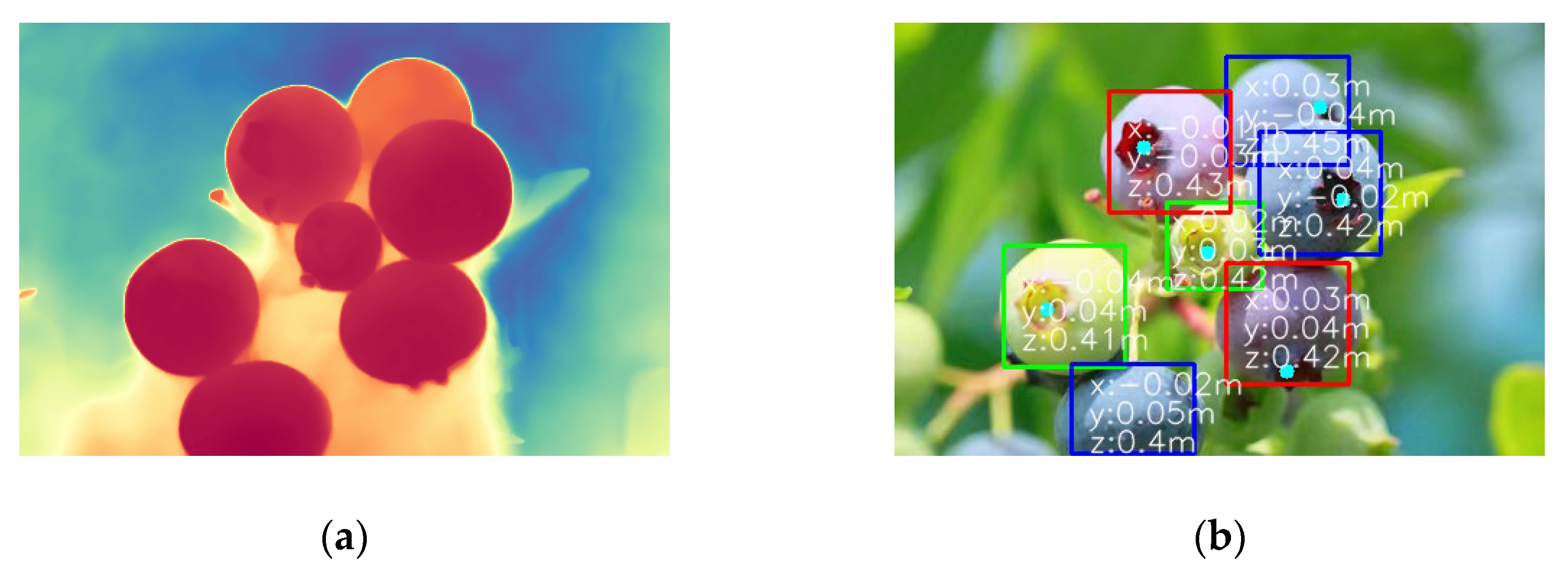

2.3.2. 3D Spatial Localization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Blueberry and Calyx Scar Detection Results

3.1.1. Experimental Result Statistics

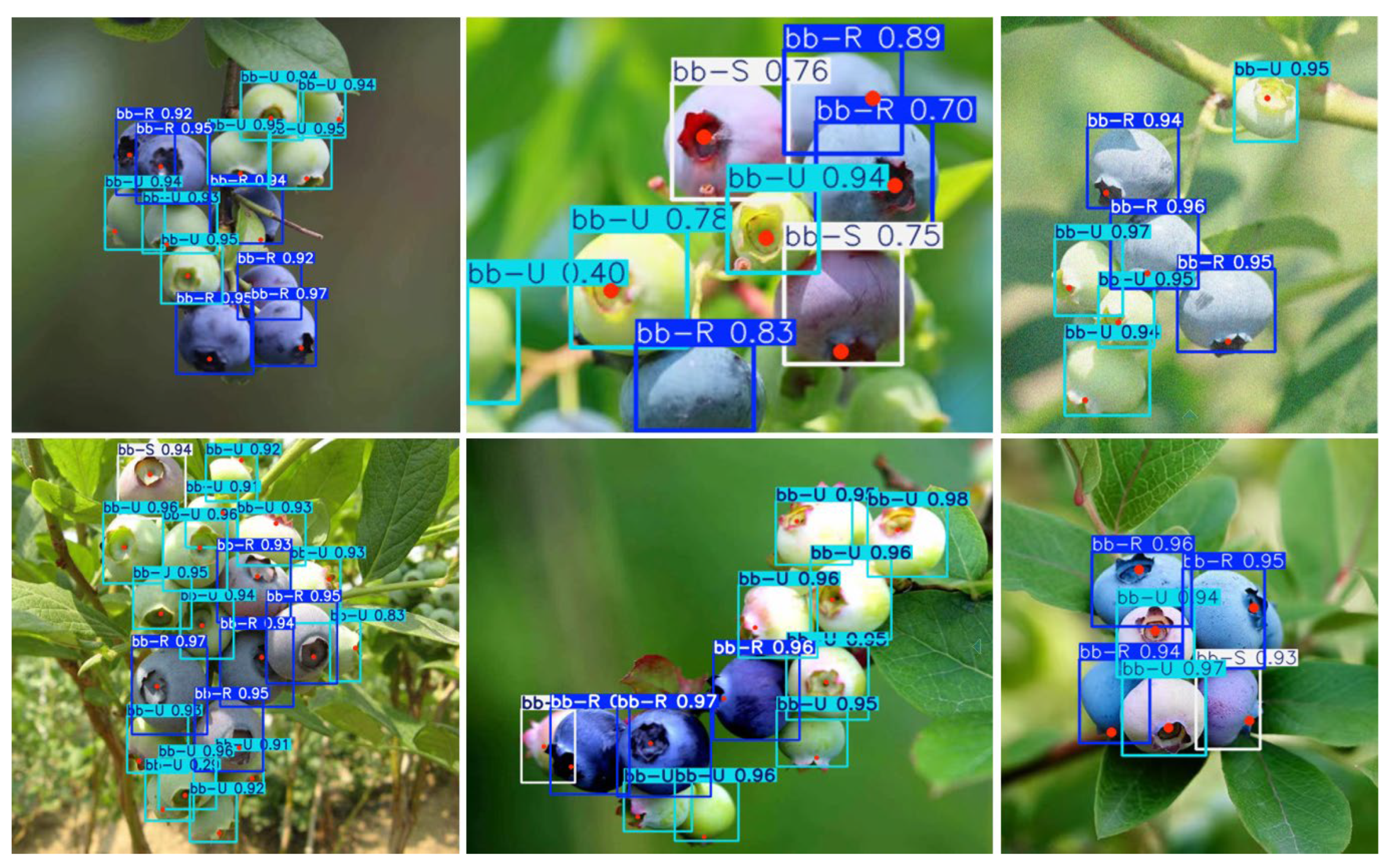

3.1.2. Visualization of Detection Instances

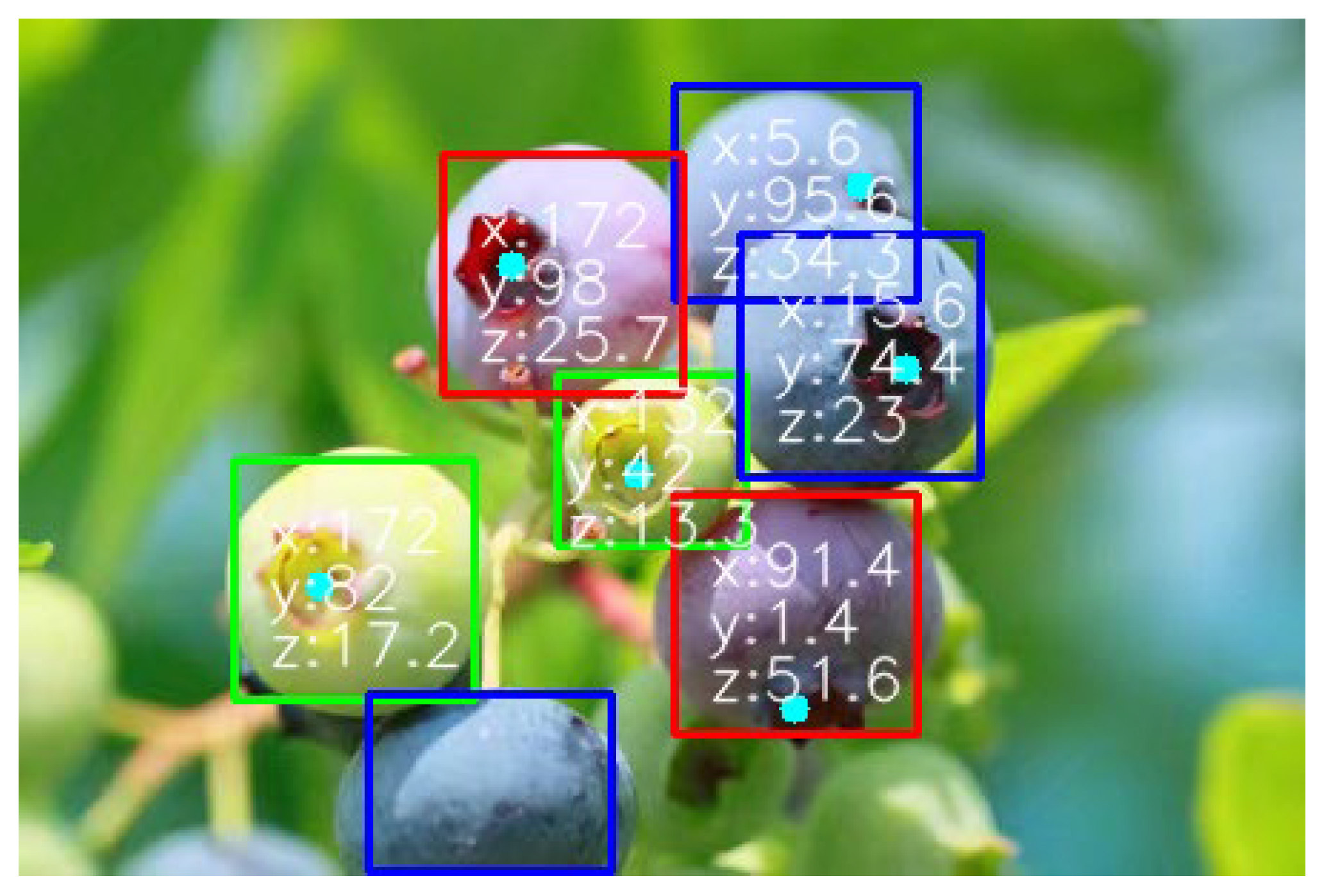

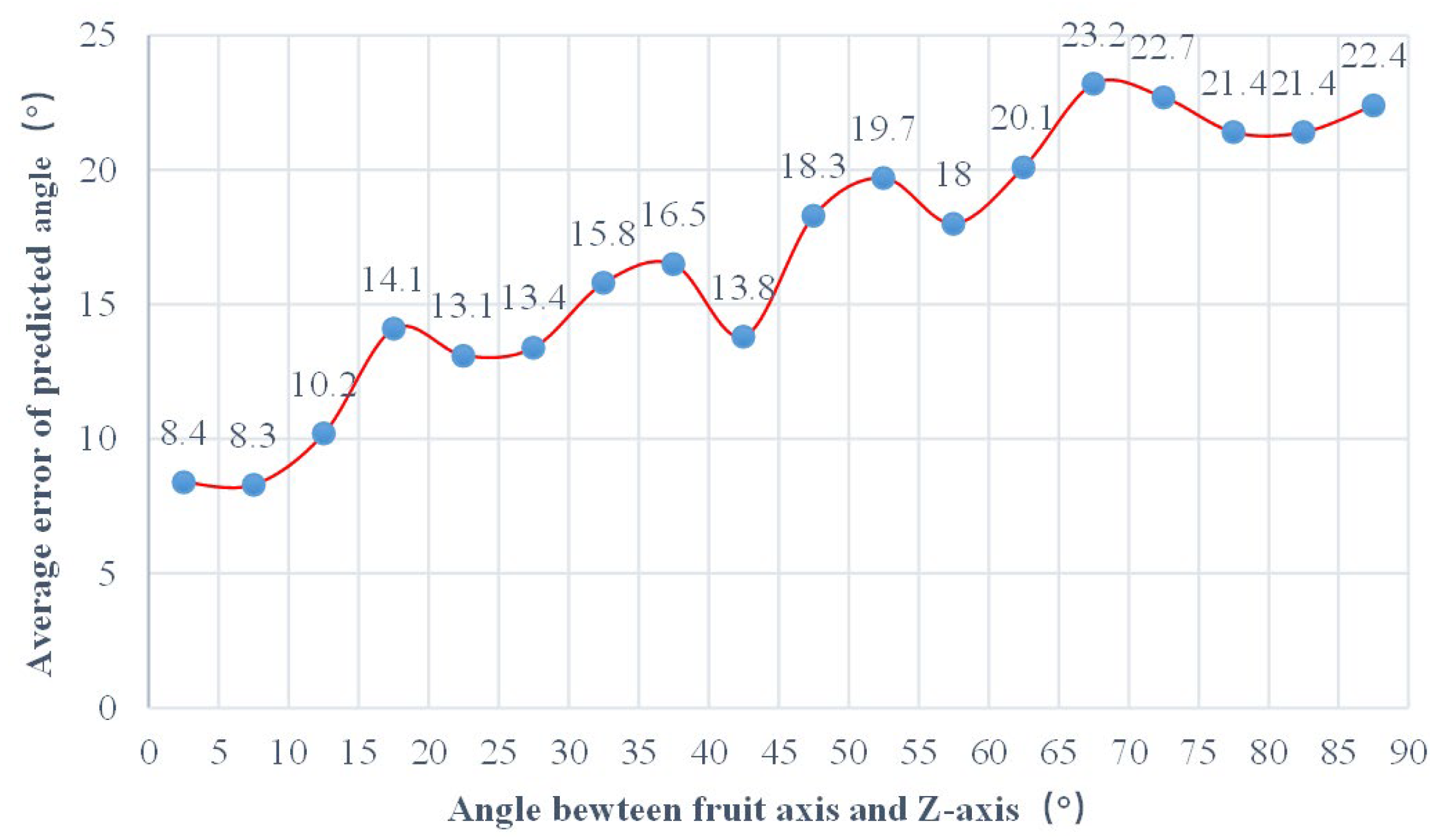

3.3. 3D Localization Results of Blueberry Fruits

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lobos, G. A.; Bravo, C.; Valdés, M.; Graell, J.; Ayala, I. L.; Beaudry, R. M.; Moggia, C. Within-plant variability in blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.): maturity at harvest and position within the canopy influence fruit firmness at harvest and postharvest. Postharvest Biol 2018, 146, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondino, L.; Briano, R.; Massaglia, S.; Giuggioli, N. R. Influence of harvest method on the quality and storage of highbush blueberry. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 10, 100415–100423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2016), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27-30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39(6), 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J. Y.; Kweon, I. S. CBAM: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV 2018), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, F.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Shi, Z. A Lightweight Detection Method for Blueberry Fruit Maturity Based on an Improved YOLOv5 Algorithm. Agriculture 2024, 14, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Liu, M.; Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, J. The use of a blueberry ripeness detection model in dense occlusion scenarios based on the improved YOLOv9. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2018), Salt Lake City, Salt Lake City, USA, 18-22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, CY.; Yeh, IH.; Mark Liao, HY. YOLOv9: learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In Proceedings of the 18th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV 2024), Milan, Italy, 29 September - 4 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, X.; Zong, Z.; Xuan, K.; et al. Detection of maturity and counting of blueberry fruits based on attention mechanism and bi-directional feature pyramid network. Food Measure 2024, 18, 6193–6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, QV. EfficientDet: scalable and efficient object detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2020), Seattle, USA, 14-19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gai, R.; Liu, Y.; Xu, G. TL-YOLOv8: a blueberry fruit detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv8 and Transfer Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 86378–86390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Han, Q.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Zou, X. YOLO-BLBE: A Novel Model for Identifying Blueberry Fruits with Different Maturities Using the I-MSRCR Method. Agronomy 2024, 14, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C. GhostNet: more features from cheap operations. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2020), Seattle, USA, 14-19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In Proceedings of the 20201 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2021), Nashville, TN, USA, 20-25 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Ma, X.; Hu, W.; Tang, P. Lightweight Blueberry Fruit Recognition Based on Multi-Scale and Attention Fusion NCBAM. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zang, W.; Ma, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Lightweight YOLO v5s blueberry detection algorithm based on attention mechanism. J. Henan Agric. Sci. 2024, 53(3), 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; et al. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, California, USA, 4-9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Lin, M.; Sun, J. ShuffleNet: an extremely efficient convolutional neural network for mobile devices. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2018), Salt Lake City, Salt Lake City, USA, 18-22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wen, Y.; He, L. SCConv: spatial and channel reconstruction convolution for feature redundancy. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2023), Vancouver, Canada, 18-22 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Na, X.; Shi, J.; Sun, Q. FM-YOLOv8: Lightweight gesture recognition algorithm. IET Image Processing 2024, 18(13), 4023–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, Q.; Huang, M.; Guo, Y.; Qin, J. Pose estimation of sweet pepper through symmetry axis detection. Sensor 2018, 18(9), 3083–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehnert, C.; Sa, I.; McCool, C.; Upcroft, B.; Perez, T. Sweet pepper pose detection and grasping for automated crop harvesting. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Stockholm, Sweden, May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, G.; Tang, Y.; Zou, X.; Xiong, J.; Li, J. Guava detection and pose estimation using a low-cost RGB-D sensor in the field. Sensors 2019, 19(2), 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Gao, G. Grasping model and pose calculation of parallel robot for fruit cluster. Transactions of the CSAE (in Chinese with English abstract). 2019, 35, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, S.; Zhang, Q. A method of recognizing the grapefruit axial orientation by binocular vision. Journal of Jiangnan University (Natural Science Edition) 2012, 11, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z. , Han, J.; Ding, G. Yolov10: real-Time end-to-End object detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14458. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. YOLOv11: An overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Blueberry Detection | Calyx Scar Detection | Time Consumption (ms) | ||

| mAP50 (%) | mAP50-95 (%) | mAP50 (%) | mAP50-95 (%) | ||

| All | 99.2 | 95.8 | 87.0 | 86.6 | 0.4 |

| bb_R | 99.5 | 96.2 | 87.2 | 86.8 | |

| bb_S | 99.1 | 94.9 | 85.4 | 84.9 | |

| bb_U | 99.0 | 96.2 | 88.3 | 88.2 | |

| Para. Scale |

Module | Blueberry Detection | Calyx Scar Detection | Time Consumption (ms) |

||

| mAP50-95 (%) | Improvement (%) | mAP50-95 (%) | Improvement (%) | |||

| N | DSC | 93.5 | base | 84.1 | base | 0.3 |

| Ours | 95.8 | + 2.3 | 86.6 | + 2.5 | 0.4 | |

| CBS | 96.2 | + 2.7 | 87.3 | + 3.2 | 0.6 | |

| S | DSC | 93.8 | + 0.3 | 85.2 | + 1.1 | 0.4 |

| Ours | 96.0 | + 2.5 | 87.7 | + 3.6 | 0.5 | |

| CBS | 96.3 | + 2.8 | 88.0 | + 3.9 | 0.8 | |

| M | DSC | 93.9 | + 0.4 | 84.9 | + 0.8 | 1.6 |

| Ours | 96.1 | + 2.6 | 87.5 | + 3.4 | 1.8 | |

| CBS | 96.4 | + 2.9 | 88.2 | + 4.1 | 2.1 | |

| Category | Average Errors(°) | ||

| X-axis | Y-axis | Z-axis | |

| All | 13.7 | 14.2 | 19.2 |

| bb_R | 14.5 | 15.4 | 17.8 |

| bb_S | 12.4 | 14.9 | 19.4 |

| bb_U | 14.1 | 12.4 | 20.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).