1. Introduction

Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) belonging to the Lythraceae family, is a highly valued fruit known for its delicious seeds packed with nutrients and health benefits, including vitamins C and B, anthocyanins, sugars, calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) [

1]. It is also a poplar ornamental tree for flowering and -bearing aesthetics [

2], and has been a traditional medicine due to its active compounds exhibiting anthelmintic, antiseptic, and antiviral properties [

3]. However, The traditional management of pomegranate orchard heavily relies on manual labor, resulting in labor-intensive processes, low efficiency, increased cost, and reduced profit. The advent of computer vision presents a viable solution to these challenges by enabling automated management practices, which include the precise detection of the developmental stages of pomegranate fruits. The advancement of objective detection algorithms is crucial for addressing these issues.

The single-stage objective detection algorithm characterized with less calculation and faster image processing is more suitable for real-time target detection in complex agricultural scenarios [

4]. As a representative, YOLO network can meet the smaller model size and fewer parameters simultaneously, and is more suitable for devices with limited computing power and embedded system devices commonly used in agricultural operations [

5]. Since the popularity of agricultural intelligent equipment is currently faced with the high cost of deploying and maintenance hardware resources, coupled with the limited computational power of hardware, the lightweight implementation can be designed to greatly minimize parameters of the model and effectively reduce the computational complexity, making the object detection algorithm run smoothly even on edge devices with limited storage and computing power [

6]. Therefore, the developments of lightweight for deployment, accurate detection, fast computing, small model size are important aspects in the evolution of the current YOLO algorithm.

The iterations from YOLOv1 advanced to YOLOv10 exhibit the progress of this algorithm. Zhao et al [

7] described the advancements from YOLOv1 to YOLOv7. Ultralytics company launched YOLOv8 in 2023, by replacing the C3 structure with C2f for more gradient flow, which is faster and smaller than the previous model, but retaining the ELAN structure of YOLOv7 [

8] in the backbone network and Neck part for efficient fusion of feature information from different layers Xiao et al [

9]. utilized YOLOv8 model to identify apples at different ripening stages by detecting apple peel, and the results demonstrated that YOLOv8 was effective and significantly improved the classification accuracy. YOLOv9 features programmable gradient information technology designed to achieve superior accuracy, stability, and reasoning speed [

10]. Lastly developed YOLOv10 combines CSPNet and Transformer modules to get faster [

11]. However, compared with YOLOv8, YOLOv9 and YOLOv10 have not significantly improved in accuracy, speed, frames per second (FPS) and they are still not suitable for deployment on lightweight terminals. The complex network structure, many parameters and high configuration requirements of training result in the application of advanced object detection algorithms like YOLOv8 in agriculture still faces major challenges due to the delay of real-time detection and the high cost of deployment on the equipment. In addition, for specific agricultural production solutions, such as the distinction of the development stages of pomegranate fruit, the current research is still insufficient.

Previous studies have shown that introduction of advanced or optimized module into the backbone network and the neck of the model module is an effective strategy to enhance the detection accuracy, efficiency, and lightweight of the model. For instance, Wu et al [

12] developed a deep learning algorithm model based on YOLOv4 for real-time detection of apple flowers, whose accuracy and speed are improved over the original model. Kumar et al [

13] improved the YOLOv5s model by using the Ghost Net network embedded with the coordinate attention (CA) module as the backbone network, named YOLO-BLBE model, to detect blueberry fruits at ripening and semi-ripening stages, providing technical support for realizing the automation picking of blueberry fruit. Zhong et al [

14] proposed a lightweight and efficient mango detection model by introducing Darknet53 structure to YOLOv8 for the compression of the number of channels, significantly reducing the model’s parameters and Floating-point operations per second (FLOPs). Furthermore, by integrating the EMA attention mechanism, the model’s ability to focus on key features was enhanced, effectively reducing the occurrence of false and missed detections, thereby achieving higher detection accuracy in complex natural environments. Xu et al [

15] proposed a lightweight YOLORFEW model that improved on YOLOv8 by replacing the traditional convolutional layer with RFAConv, focusing more effectively on the regions that contribute significantly to feature extraction, and further enhances the feature extraction and fusion capability. The experimental results showed that the YOLO-RFEW model could significantly improve the detection accuracy while maintaining the lightweight design. Yang et al [

16] developed an improved strawberry maturity detection and grading model of YOLOv8s by introducing Swin Transformer module in the feature fusion stage and applying multi-head self-attention mechanism, which significantly improved the model’s generalization ability and feature fusion efficiency.

Currently, there are relatively few researches on computer vision for pomegranate fruit detection. Vasumathi’s team [

17] developed an algorithm model for pomegranate disease recognition, which integrated CNN and LSTM technologies with an accuracy rate of 97.1%. However, the model is computationally expensive during the training process and requires the support of a large amount of training data, as well as less accurate when detecting pomegranate fruits in complex background of natural scenes. Mitkal et al [

18] proposed an automatic classification method for pomegranate fruits, which combined CNN, K-means clustering algorithm and image processing technology. Naseer et al [

19] developed a random forest (RF) algorithm for predicting the growth stages of pomegranate, which combines CRnet of transfer learning with spatial feature extraction. Previously, we proposed a lightweight YOLO-Granada algorithm for detecting the development stages of pomegranate fruit by replacing the YOLOv5s backbone with the lightweight ShuffleNetv2 network and incorporating the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) attention mechanism [

7]. The experimental data showed that the model size and the parameters of this network were compressed 56.3% and 54.7% of the original network, respectively, the detection speed is faster than the original network by 17.3%. However, the shortcoming of this algorithm is its 8.66 FPS, failing to meet the requirements of real-time display.

In order to further improve the display speed and the lightweight of network, we propose effective strategies in this paper for the pomegranate fruit development stages detection by integrating the advanced technologies to optimize the target detection algorithm. The significant contributions are summarized as follows:

(1) We present a faster and lightweight model YOLO-Punica for pomegranate fruit development detection. This model adopt YOLOv8n as benchmark, incorporates our proposed Dual Path Downsampling Module (DPDM) into the backbone network and the neck, which significantly enhancing the accuracy and computational efficiency of the model. Additionally, we integrate CCFM structure into the neck model to blend fine-grained details with context information, significantly minimizing the parameters and improving the model’s performance.

(2) Our study also includes a series of the optimization for deep learning models, covering 12 ablation experiments to fine-tune and improve the YOLO-Punica model. In addition, we compare the performance of our YOLO-Punica with other advanced target detection models through 20 validation experiments to evaluate its effectiveness in advices with cost-effective.

The architecture of this article is as follows: the introduction reviews the previous research that are closely related to our topic in detail. In the Methods section, we elaborate on the specific design of the network architecture of YOLO-Punica. In the subsequent Experiments and Results, we detail the design of the experiments, the evaluation criteria, and the results of the comparison experiments with other models. Finally, the conclusion and prospect part summarizes the results of this research, clarifies the technical innovation points of this research, and points out the potential exploration direction for subsequent research.

2. Methodology

In this study, an innovative model YOLO-Punica for detecting the development stages of pomegranate fruits was generated by (1) utilization of the fundamental network from YOLOv8, and (2) introduction of a proposed lightweight DPDM downsampling module and (3) integration of the CCFM module in the neck structure, ultimately, obtaining fast, accurate and lightweight of objective detection.

2.1. DPDM Module

The detailed structure of the DPDM module is illustrated in

Figure 1a. The downsampling of DPDM is achieved by first applying a Max pooling operation to the input feature image and compressing the image size to half of its original size. The main function of the Max Pooling Layer is to perform feature dimensionality reduction, reduce computational complexity, and extract important feature information [

20]. Subsequently, splitting the feature channels into two parts, X1 and X2, to separate computations within the channels. Then, a 3×3 convolution operation is performed on X1 to extract features and reduce the dimension of the image. For X2, a combination of Max pooling and 1×1 element-by-element convolution is used to enhance the nonlinear feature representation and continue to reduce the dimension of the image. Finally, X1 and X2 are concatenated together to generate the output of DPDM module X3. In summary, DPDM, with its unique dual branch structure, successfully divides the input feature graph into two sub feature graphs and processes them separately. This enables it to capture feature information at different scales and levels simultaneously, thus preventing the loss of many tiny features. The design not only enhances the feature extraction capability of the model, but also achieves the feature fusion through Concat concatenation, combining the complementary information from different branches to further improve the accuracy of the model. In addition, DPDM introduces two Max pooling layers, which effectively reduces the spatial dimension of the feature graph and improves the computational efficiency, which is essential to achieve the lightweight of the model. Compared with standard convolution downsampling, DPDM shows significant structural and performance advantages. Therefore, when dealing with complex tasks such as target detection, the standard convolution shown in

Figure 1b performs a series of operations such as convolution operation, batch normalization and activation function after input images, and downsampling with large strides is likely to cause the fine-grained features of the target to be lost during feature extraction. By optimizing the network design, the multi-branch structure of DPDM endows the model with stronger adaptability and scalability. Each branch contains different downsampling, convolution and pooling operations to capture diversified features, and by introducing a second Max pooling and feature fusion strategies, it can be flexibly adjusted to adapt to different input features and task requirements. Those enables DPDM to have high computing efficiency while maintaining high performance.

2.2. CCFM Module

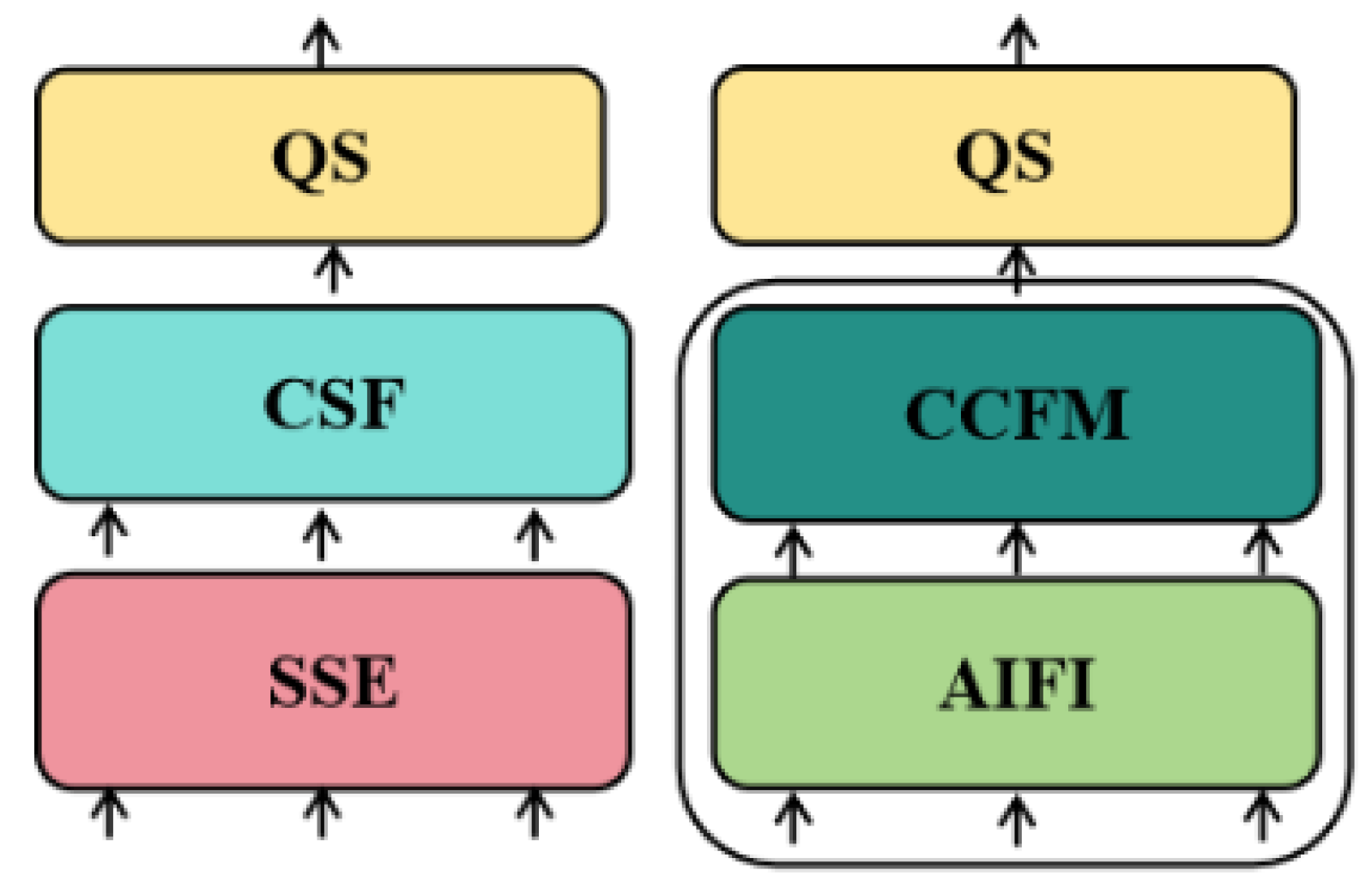

Integrating features of different scales through fusion operation is very important for multi-scale target detection and recognition. Different from the single-scale converter encoder PANet used in YOLOv8 for feature fusion, the high-efficiency hybrid encoder architecture CCFM proposed in RT-DETR framework for the first time [

21] CCFM combines attention-based intra-scale feature interaction (AIFI) and cross-scale feature fusion (CCFF) based on convolutional neural networks (CNN)(

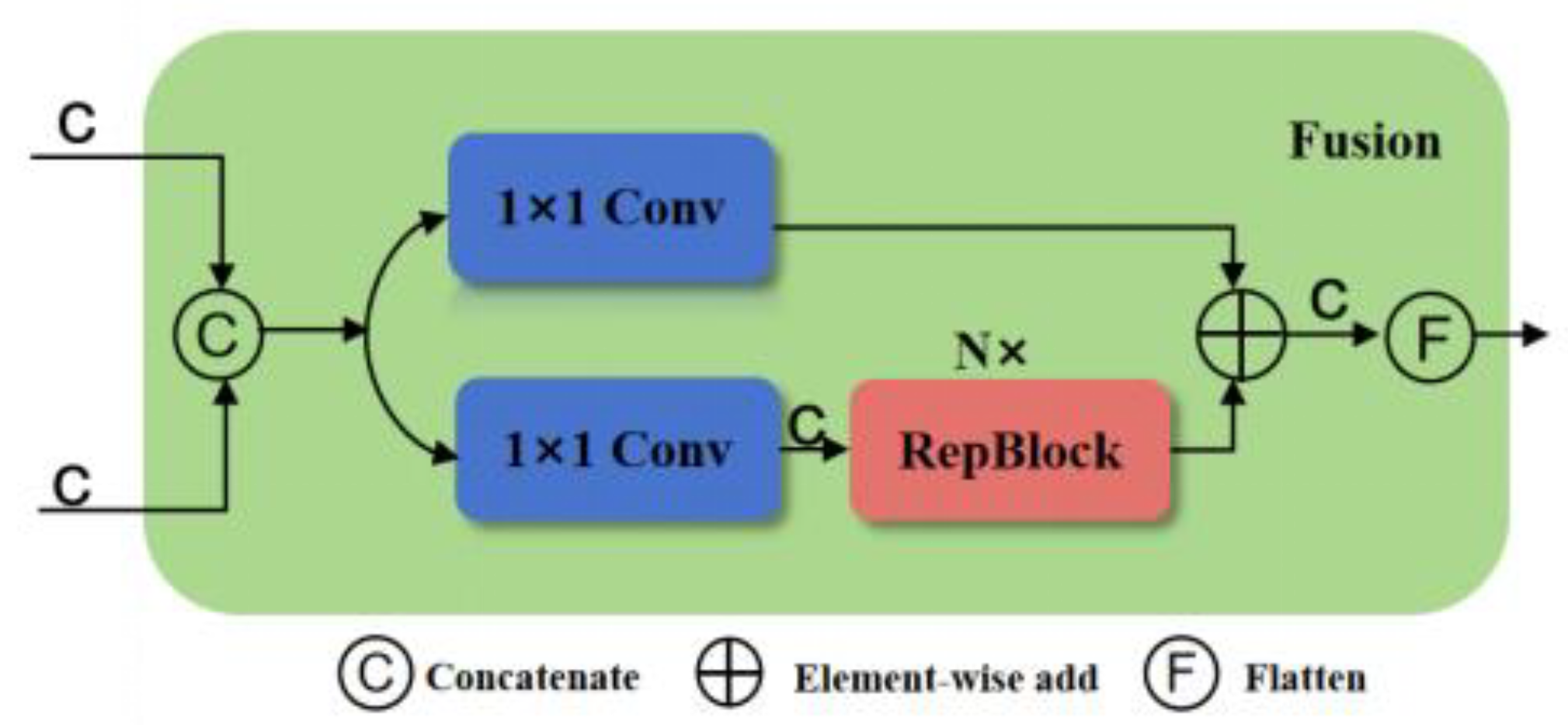

Figure 2). In detail, CCFM operates the multi-scale feature interaction into two steps: intra-scale interaction and cross-scale fusion. Due to just calculating intra-scale interaction and avoiding redundant calculation of cross-scale information interaction, the computational cost is significantly reduced and the performance of the model is improved, which is suitable for devices with limited computing resources. In addition, along feature fusion, path, fusion modules of CCFM composed of convolution layers are inserted. The convolution layers in the module are responsible for fusing the features of adjacent scales to generate a new feature representation. The fusion block contains N RepBlocks and two paths output. The detailed structure of CCFM is illustrated in

Figure 3 Specifically, two 1×1 convolution layers are embedded in the fusion block to adjust the number of channels for the feature. Furthermore, N RepConv modules made of RepBlocks facilitate the efficient fusion of features. Finally, the fusion of two path outputs is realized by the method of element-wise addition fusion. Adopting multi-scale features and attention mechanism, CCFM effectively integrates features of different scales and combines details with context information to improve the detection ability of small-scale objects.

2.3. The Comprehensive Framework Diagram of YOLO-Punica

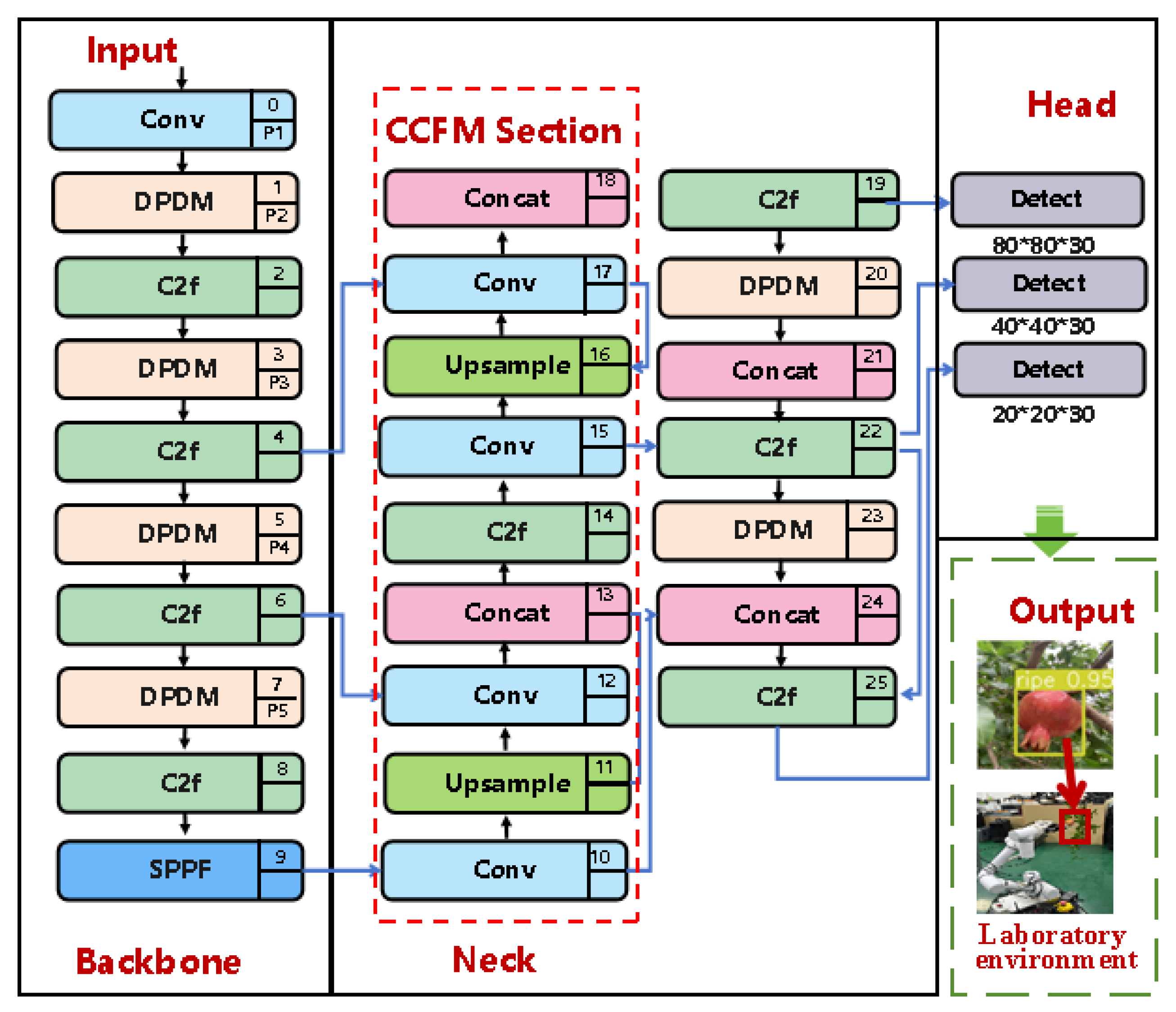

In order to clearly present the proposed YOLO-Punica network architecture, we depict a schematic of the integrated framework in

Figure 4. The diagram includes four main components, namely, the input, the backbone, the neck, and the prediction. Each of them plays an integral role in the function of the network.

2.3.1. Input

The Input section is mainly responsible for image preprocessing and enhancement. In the preprocessing step, the input image is resized to match the specific requirements of the network, and the pixel values of the image are normalized from [0, 255] to [0, 1]. As for image enhancement, we used mosaic data enhancement technique and adaptive anchor frame calculation method based on K-mean algorithm to further handle the preprocessed images. This anchor frame information in the network model can optimize and enhance the performance of the model.

2.3.2. Backbone

In the task of target recognition, downsampling plays a crucial role in reducing the size of the feature image while preserving the key feature information. In addition, it can effectively reduce the computational complexity and the parameters, and thus accelerate the training and reasoning speed of the neural network. In the original YOLOv8n architecture, the core component of feature extraction was the C2f network. In the process of C2f module, the input data is first preprocessed through a convolution layer to implement downsampling, and then enters a residual module (using split strategy), and then undergoes in-depth processing by n Dark net Bottleneck modules. Afterwards, the output of the residual module is merged with the result of the trunk path through a Concat operation and fed into a convolutional layer again to complete the final output. This downsampling operation reduces the size of the feature image but inevitably leads to the loss of fine-grained information.

Given that the pomegranate dataset in this study contains numerous small targets and redundant information is scarce, any loss of fine-grained information can have a significant impact on the detection accuracy of the model. Therefore, a special module that can collect coarse-grained and fine-grained information simultaneously needs to be introduced in the downsampling process of the model to accurately detect the characteristics of pomegranate fruits at different developmental stages. Since the actual data transmission environment of pomegranate orchard is unstable, it is particularly important to reduce computation for achieving lightweight through the network optimized for the detection of pomegranate fruits. In the YOLO Punica-model, we introduced a proposed DPDM module for downsampling. DPDM adopts unique dual branch structure to capture feature information at different scales and two Max pooling operation effectively reducing the spatial dimension of the feature graph to improve the computational efficiency. The detailed structure of the DPDM module have been illustrated in

Figure 1a.

2.3.3. Neck

We introduced the CCFM structure into the Neck architecture of the YOLO-Punica model and generated feature maps with dimensions of 80×80, 40×40 and 20×20 through upsampling technology to fuse the features of different scales, improve the model’s adaptability to scale changes, and enhance the detection accuracy of small-scale targets. These feature maps are then directly cascaded with the feature maps extracted from the backbone network. Ultimately, the adding of CCFM improves the computational efficiency and detection accuracy of YOLO-Punica. See above for more information on CCFM.

Meanwhile, a DPDM module is introduced in the Neck part, which is responsible for further extracting and enhancing useful feature information from Backbone’s feature graph, and reducing computation and memory consumption while maintaining and enriching feature information. The DPDM module in the Neck section is also responsible for the fusion of feature maps from different scales. This fusion helps to extract more representative features and enhance the detection ability of the model for objects of different sizes.

2.3.4. Prediction

The prediction frames on the feature map is generated by applying Anchor frames to the feature map. When applying YOLO’s generic prediction architecture, the feature map extracted from the feature pyramid layer is first processed by the head model in order to predict the bounding box where the target is located, the target’s category label and the corresponding confidence score. Subsequently, these prediction frames are filtered using the DIoU NMS algorithm to eliminate the predictions that are highly redundant. Ultimately, CIoU is selected as the bounding box loss function at the output stage, aiming to facilitate the model to achieve better and faster convergence performance.

Therefore, the overall dimension of the output vector can be calculated by using equation 1:

Sout is the Output size, Numaf is the number of anchor frames, Numtrlp is the number of target rectangle location parameters, 1 is the target confidence, and Numtc is the number oftarget categories. For the pomegranate detection model, the feature maps obtained after up-sampling are of sizes 80 × 80, 40 × 40, and 20 × 20, and the model needs to detect pomegranate fruits at five different target categories. The number of target rectangle parameters is 4. Therefore, for the pomegranate fruit detection model, the output size of each feature map is [80, 80, 3*(4 + 1 + 5)]; [40, 40, 3*(4 + 1 + 5)]; [20, 20, 3*(4 + 1 + 5)] respectively.

3. Experiments and Results

3.1. Datasets

3.1.1. Data Acquisition

The dataset (

https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/kgwsthf2w6/5) contains 5875 clear images of pomegranate fruits was used in this study [

22]. The images were taken during the fruit ripening from May to September 2022 at the campus of Henan Institute of Science and Technology in Xinxiang city, Henan province, China. The dataset was saved in "heic" format for pomegranate fruit identification, detection and maturity judgement. The images were divided into three subsets, namely, training set (4685 images), validation set (585 images) and test set (587 images).

3.1.2. The Criteria for Data Classification

We classified the images into five groups including "bud", "flower", "early-fruit", "mid-growth" and "ripe" according to the development stages of pomegranate fruit. As shown in

Figure 5a, "bud" means that when a bud grows to the size of a green pea, it can be identified as entering the bud stage. “Flower” is presented in

Figure 5b, which has two types includes trumpet-shaped and tube-shaped.

Figure 5c displays “early-fruit”, at this point the petals fall off and the fruit sits and begins to swell. Mid-growth, as shown in

Figure 5d, the fruit volume expands rapidly again in this period, and the fruit color changes to green. Ripe, as illustrated in

Figure 5e, means the fruit has reached maturity, the pericarp changes from green to yellow and appears glossy, the colored varieties are fully colored (e.g. the pomegranate fruit in this dataset is bright red). The labelled information of groups is saved in "xml" format file.

Different evaluation metrics can reflect the performance of the algorithm in different aspects. In this study, evaluation metrics including selection precision, recall, F1 score and average precision were used to assess the detection performance of the model. Model size, parameters and FLOPs were served to measure the complexity, the scalability performance, and the computational speed of the model, respectively. The efficiency of the model is measured by the frame rate (FPS). In equation 2, Precision is defined as the ratio of correctly detected images of pomegranate fruits to all detected images, and TP and FP denote the number of correct and incorrect identifications in pomegranates detection by the network model, respectively.

In equation 3, Recall is defined as the ratio of images of correctly detected pomegranate fruits to images of correct and undetected pomegranates, and FN denotes the number of all true pomegranates not detected by the network model. The F1 score is the reconciled mean of precision and recall.

The mAP in Equation 5 is the mean average precision, which represents the average precision of all detection categories, where k is the number of categories.

3.1.3. Configuration of the Training and the Comparison Test

Anaconda 3 was used to create the training environment, and several artificial neural network libraries involving PyTorch 1.11, Python 3.7.12, and Torch Vision 0.11.1 were employed for configuration. Moreover, we adopted the deep neural network acceleration library CUDA 11.2.

The comparison experiments were performed by running different models on a computer platform consisting of an Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-10400F CPU to verify the effect of model size on the terminals. Each models were built on PyTorch 1.11 and Python 3.7.12 was used to write the program code. The batch size was set to 1, the confidence threshold was set to 0.001; and the NiS-loU threshold to 0.6.

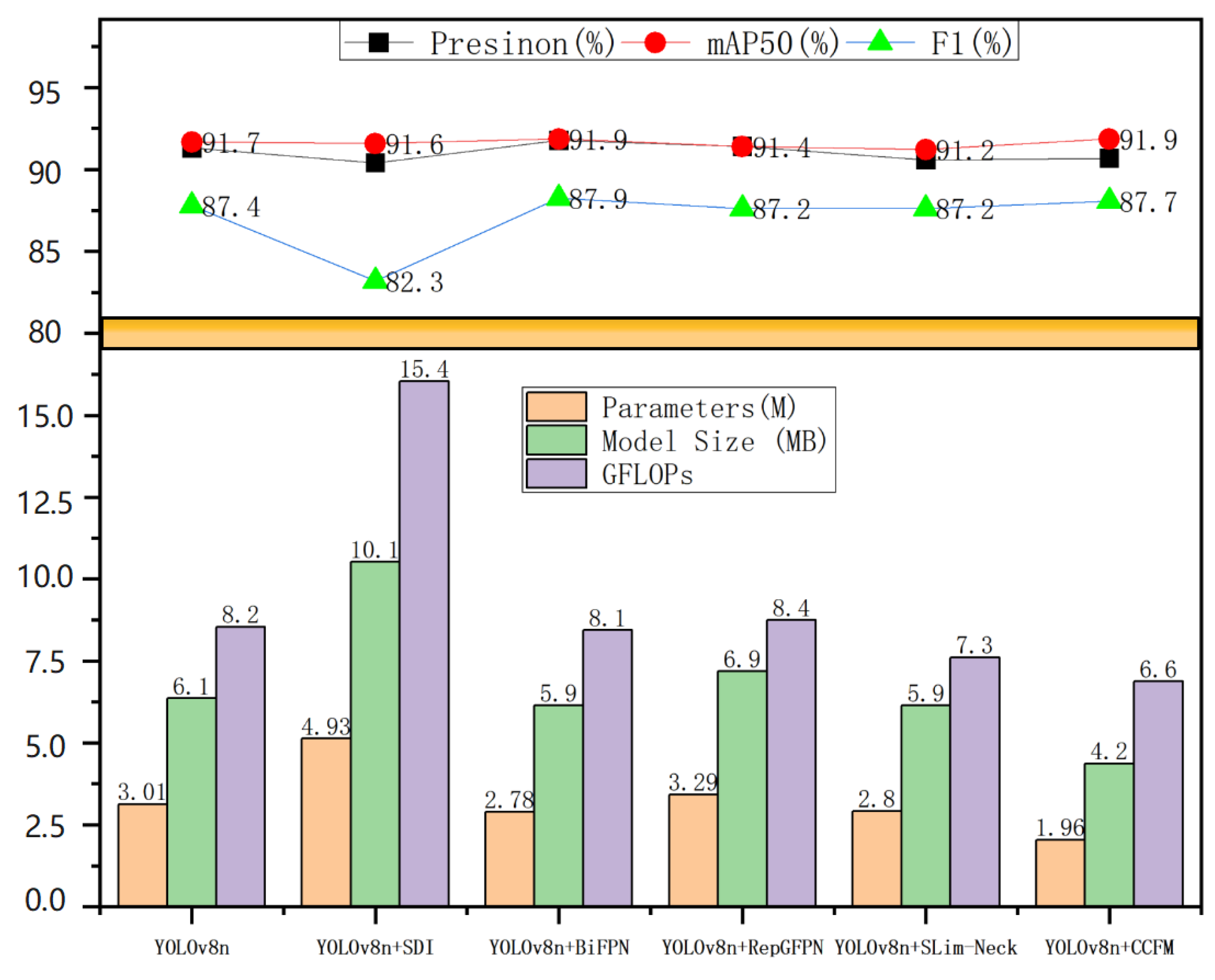

3.2. Ablation Experiments

Focusing on lightweight of the model, the ablation experiments were conducted on the original YOLOv8n, which is the popular baseline with 6.1 MB model size, by adding five maintaining lightweight neck networks, to tested various improvements. The five lightweight neck structure involves Slim-Neck [

23], BiFPN [

24], RepGFPN [

25], SDI [

26], and CCFM.

Table 1 and

Figure 6. show that the introduction of Slim-Neck, BiFPN, RepGFPN did not significantly improve the performance of YOLOv8n, and the integration of SDI increased the model size and parameters, compared to original YOLOv8n. While the integration of CCFM into the neck of YOLOv8n significantly improves the lightweight of the model, while ensuring high accuracy.

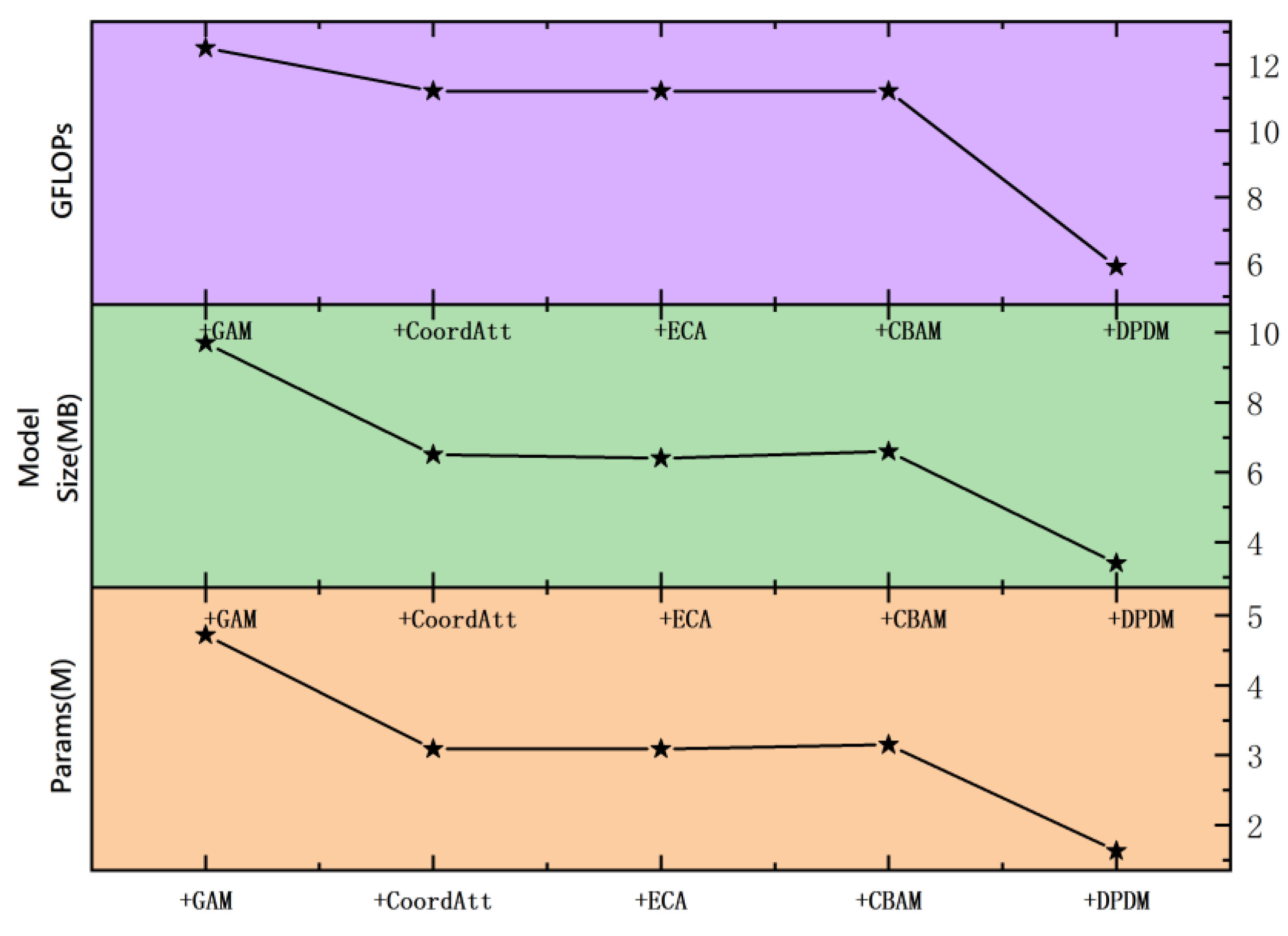

In order to verify the model improvement effect of various optimized backbone network integrated with CCFM, four mainstream backbone networks and our proposed DPDM network were incorporated with CCFM to improve of the precision and lightweight of the model.

Table 2 and

Figure 7. displays that the integration of DPDM and CCFM gain the smaller model size and decreased parameters, as well as increased precision, achieving lightweight and high precision. This is attributed to that DPDM effectively enhances feature extraction in the downsampling process, compress the model size and achieve lightweight, simultaneously. However, adding four other modules (GAM [

27], CBAM [

28], ECA [

29], CoordAtt [

30] ) to the backbone network in combination with CCFM not only fails to improve detection accuracy, but also increases the size and parameters of the model, which is not conducive to implementing lightweight models.

Table 3 demonstrate that incorporation both of modules, DPDM and CCFM, into the YOLOv8n model framework makes the model perform better than the original YOLOv8n and introduction of a single module, in terms of GFLOPs, model size, parameters and mAP@0.5. Therefore, it is a best choice to integrate DPDM and CCFM modules into YOLOv8n.

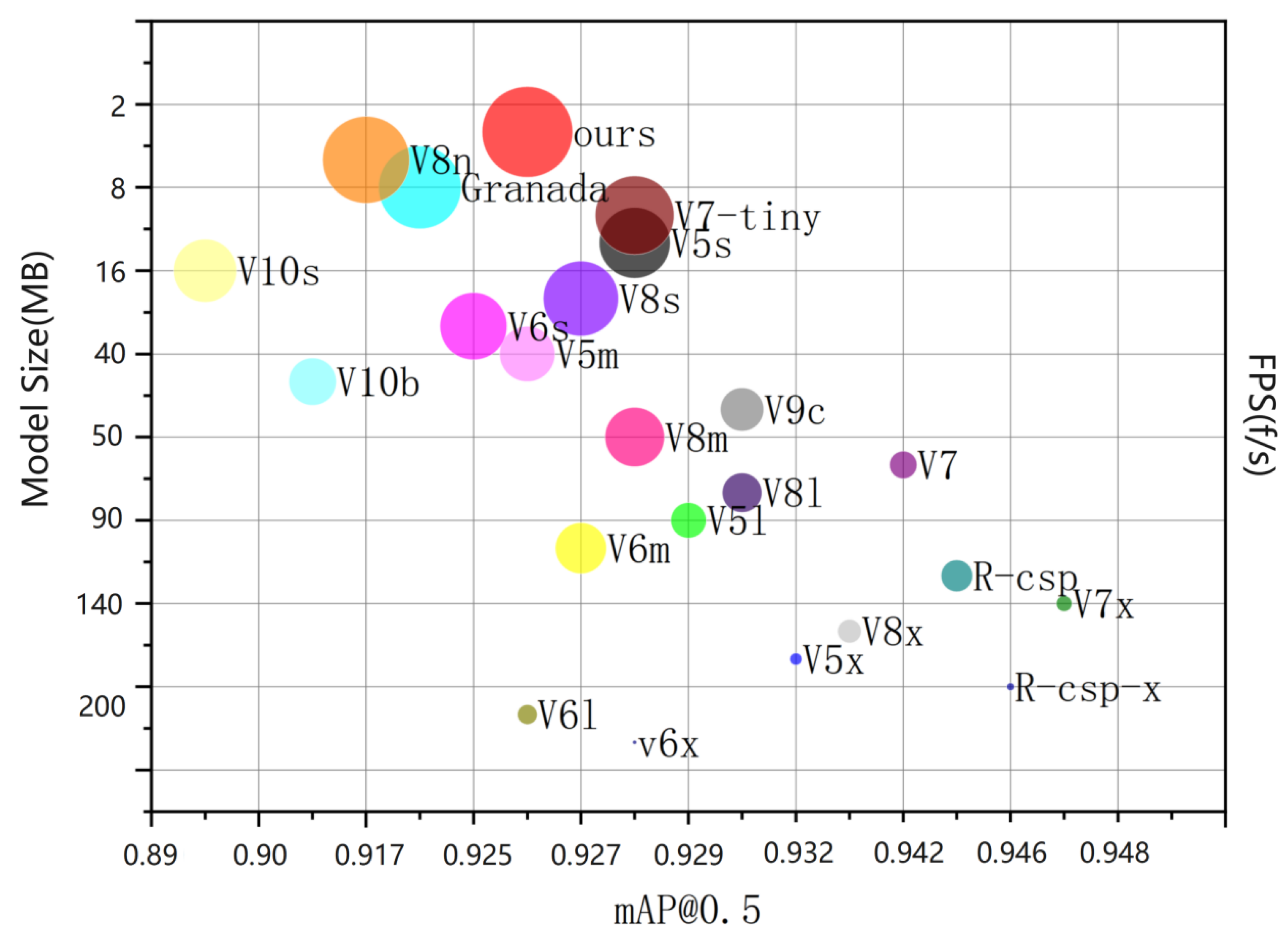

3.3. Comparative Tests

To explore whether YOLO-Punica performs better than other current advanced algorithm models, we selected twenty well-known neural networks, including serial of versions of YOLOv5 to YOLOv10 as baseline networks. As shown in

Table 4, all of algorithm models have high and basically similar F1 scores and mAP@0.5, indicating they can detect the images accurately. But they differ in GFLOPs, model sizes, parameters, and FPS.

Among YOLOv5 series, YOLOv5-Granada has the fewest parameters, the lowest computing requirement with 9.1 GFLOPs, the smallest model size (7.7M), and the fastest image processing speed with 8.66 FPS. In contrast, YOLOv5 m/l/x versions have more parameter, higher GFLOPs, larger size, and lower FPS. All of the series of YOLOv6 [

31] and YOLOv7 surpasses YOLOv5-Granada in terms of model size, parameters, GFLOP, and lower FPS. YOLOv8n exhibits the best performance among YOLOv8 series, with the fewest parameters, the smallest model size (6.1M), and the lowest GFLOPs (8.2), as well as FPS (7.2). On these parameters, it even better than YOLOv5-Granada, and YOLOv9c and YOLOv10 series. Nevertheless, it is inferior to YOLO-Punica algorithm model we designed.

The analysis of

Table 4 displays that the model size, parameters, and GFLOP of YOLO-Punica are compressed to 41.5%, 54.2%, and 71.9% of original YOLOv8n model, and to 44.2%, 42.4%, and 64.8% of the YOLO-Granada, respectively, which make the YOLO-Punica model lighter, faster, and easier to deploy on devices with limited computing resources. Moreover, YOLO-Punica model can process 14.3 images per second, which is significantly faster than 8.66 images per second detected by the YOLO-Granada, and faster than that of YOLOv8n with 12.4 FPS, indicating it more suitable for real-time detection in agriculture application. Therefore, YOLO-Punica is superior to all of other tested algorithm models. It is worth noting that YOLO-Punica also has 0.926 mAP@0.5 when comparing to other algorithm, which ensure its precision in object detection. These comparisons demonstrate the advantages of YOLO-Punica in balancing accuracy, speed, and model size, making it more suitable for deployment in agricultural environment.

Figure 8 illustrates the objective detection performance of YOLO-Punica model is mainly influenced by two key factors: mAP@0.5 and model size. The horizontal axis in

Figure 8 represents the model size (MB) corresponding to each model, and the vertical axis represents mAP@0.5.

When designing the model for the pomegranate fruit development stages detection, we carefully weighed the relationship between performance and computational resources. This is because increasing model parameters may bring performance gains, but such gains are often accompanied by higher demands on computational resources and longer inference times. On the contrary, models with fewer parameters can maintain high computational efficiency while showing good performance, which makes deployment in real-world application scenarios more feasible.

Our goal is to create a model architecture that can effectively utilize fewer parameters while maintaining high accuracy, aiming to achieve a reasonable balance between model performance and computational resources. The YOLO-Punica model incorporates a variety of optimization strategies, including the use of DPDM module to improve the backbone network, which ensures the high detection accuracy and efficiency, and the introduction of CCFM and DPDM into the Neck section effectively achieve lightweight of the network while retain high precision. By integrating these two advantageous modules into advanced YOLOv8, we have successfully created a model that is highly accurate while maintaining good performance.

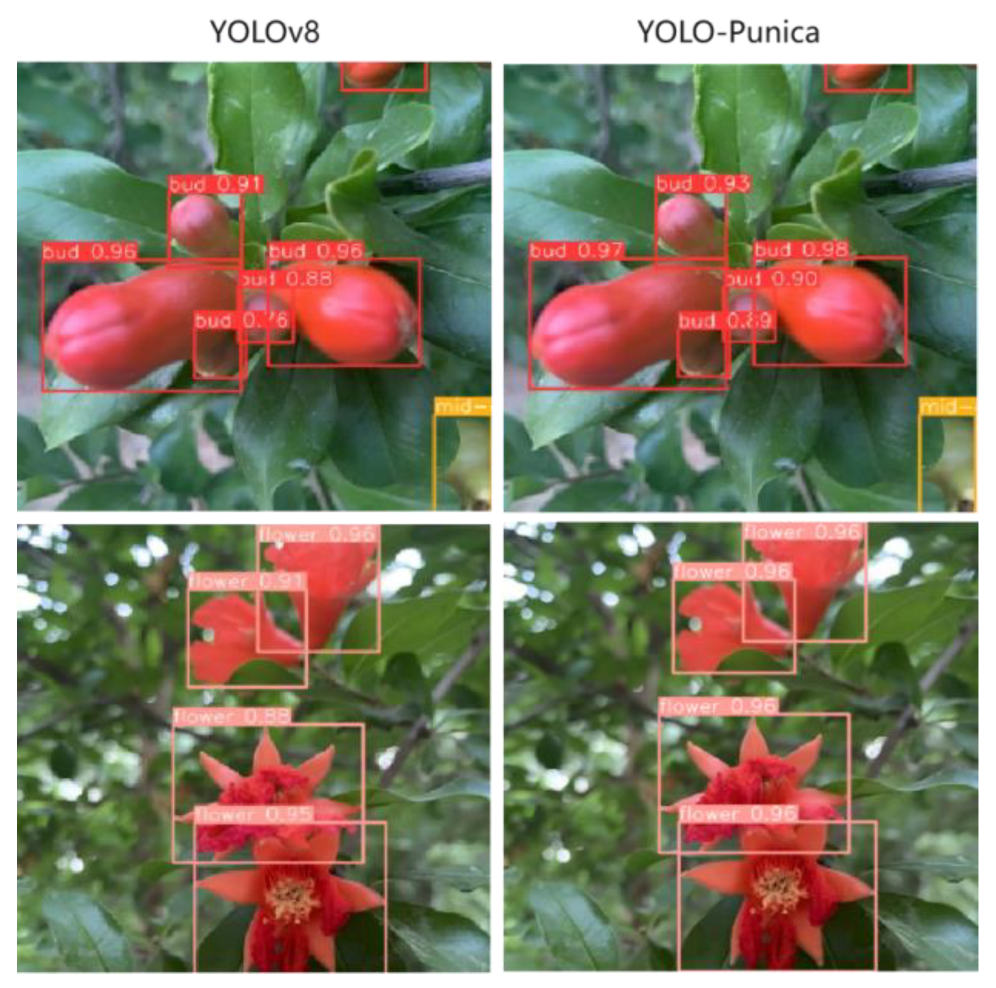

In order to highlight the superiority of YOLO-Punica model and verify its performance in real application scenarios, we specifically selected a portion of representative real scenario sets for testing. These test sets cover different lighting conditions, background complexity, and the diversity of pomegranate fruit development status, aiming to comprehensively evaluate the detection ability and robustness of the model. After rigorous testing, the model exhibits the excellent performance (

Table 5). The detection accuracy for the five categories of "bud", "flower", "early fruit", "mid growth", and "maturity" reached 0.898, 0.942, 0.906, 0.915, and 0.976, respectively. Meanwhile, the precision and recall scores of these categories also performed well, with precision ranging from 0.89 to 0.96 and recall from 0.762 to 0.935. Overall, the average accuracy of the model for all categories was 0.926, and the average recall was 0.847, which fully highlights its excellent performance in detecting objects of different categories.

Figure 9 shows that the YOLO-Punica model exhibits high accuracy and excellent feature extraction in bud and flower detection, compared to original YOLOv8n model.

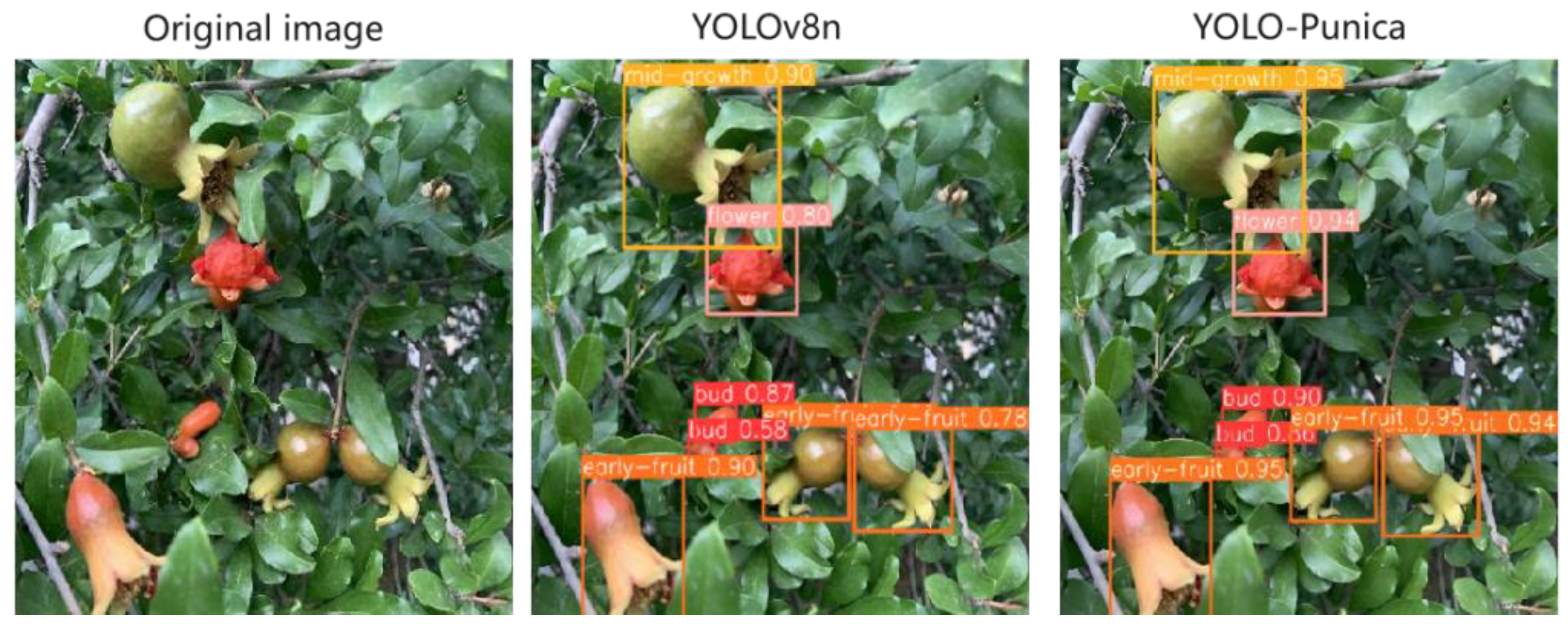

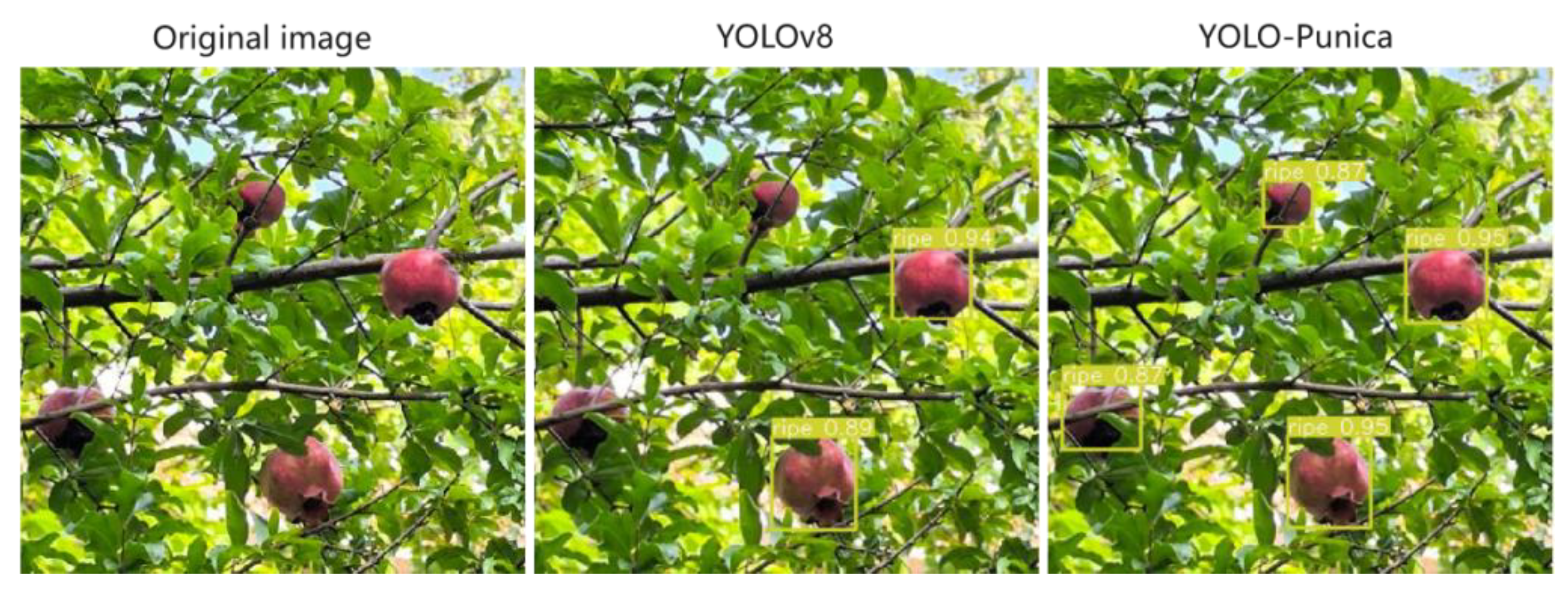

Figure 10 presents that the YOLO-Punica model also exhibits significant advantages over the original YOLOv8n model in terms of the detection effect of pomegranate fruits at different ripe stages, with a higher detection accuracy and extraction of image features.

To further validate the detection accuracy of the model in complex environments, we purposely added multiple pomegranate fruits at different growth stages to the test images at the same time. As displayed in

Figure 11, YOLO-Punica model is more accurate than that of the original model in detection of the development status of pomegranate fruits, even in such a complex scene. It is particularly worth mentioning that the YOLO-Punica model also shows excellent detection ability when facing the complex scene of occlusion.

Figure 12 displays that original YOLOv8 model fails to detect the occluded pomegranate fruits, while the YOLO-Punica model successfully detects the occluded ripe pomegranates, indicating that the YOLO-Punica model has higher robustness and accuracy in dealing with complex scenes such as occlusion. In summary, whether pomegranate fruits are at different development stages, or in complex scenarios such as occlusion, the YOLO-Punica model shows excellent detection performance, which fully proves the advancement and practicability of the YOLO-Punica model in the detection of pomegranate fruits at various development stages.

4. Conclusion and Future Works

Aiming at low-cost and low-computing power platforms such as mobile devices and agricultural smart picking instruments, we propose a lightweight pomegranate fruit development detection algorithm, namely YOLO-Punica, which is based on the improved YOLOv8 variant, integrating with our proposed DPDM backbone network and with the CCFM architecture to effectively minimize the model parameters and size for faster computing and lighter weight, as well as high detection accuracy. The improved network achieves an average accuracy value of 0.926, higher than that of the original model YOLOv8n which with an accuracy of 0.917. Meanwhile, it performs better in terms of speed and model size, with the number of parameters, GFLOPs, and model size compressed to 41.5%, 54.2%, and 71.9% of those of the original network model, respectively. Compared with twenty currently advanced models, YOLO-Punica significantly outperforms other models in terms of performance efficiency and lightweight. In addition, YOLO-Punica algorithm is able to process images at 14.3 frames per second on a low-cost CPU, which is faster than our previously proposed YOLO-Granada which processes images at 8.66 frames per second. The lighter weight and faster operation of the model represents its potential for real-time detection when applied to realistic pomegranate orchard management. The experimental data showed that this improved algorithm significantly reduces the computational requirements and accelerates the detection process, enabling real-time pomegranate detection on an agricultural smart picking robot platform, even with limited computing power and low cost. This study not only promotes the deployment of target detection algorithms in terrestrial application scenarios, which has a positive impact on the development of smart agriculture, but may also provide new perspectives for similar studies. In addition, the design idea of the algorithm provides a valuable reference for the design and application of neural networks in agriculture.

The YOLO-Punica algorithm has demonstrated a wide range of potential applications in the agricultural field, and in order to further improve its effectiveness and applicability, future research can focus on the following three key directions:

(1) Optimizing model accuracy. Future research could focus on redesigning the model to enhance its detection accuracy, especially in complex agricultural environments with variable light and shade. This may cover exploring diverse network structures, introducing advanced attention mechanisms and adopting efficient optimization strategies.

(2) Expanding the dataset to cover diverse pomegranate cultivars. In order to enhance the universality and robustness of the model, it is necessary to expand the dataset to include image samples of multiple pomegranate cultivars, to ensure that the model can accurately identify and detect pomegranate fruit of different types, thus will broadening its usefulness and applicability.

(3) Acquisition of images from multiple sources. To more effectively evaluate and improve the model’s performance in real agricultural surveillance scenarios, future research should cover the collection and integration of image and video data from smart picking robots, drones, and automated surveillance devices. The use of diverse devices for data collection is crucial for achieving comprehensive farm surveillance, which will allow us to monitor the growth and development of pomegranates by covering a wider area from multiple perspectives.

In addition, the applications of this algorithm are not only limited to agriculture, but can also be extended to surveillance systems and autonomous driving. The algorithm can also be applied to other computer vision tasks, further contributing to the advancement of deep learning technology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D. and Z.M.; methodology, C.D.; software, X.W.; validation, R.A., C.D. and X.W.; formal analysis, J.F.; investigation, Z.M.; resources, X.W.; data curation, C.D.; writing—original draft preparation, C.D.; writing—review and editing, C.D.; visualization, Z.M.; supervision, X.W.; project administration, X.W.; funding acquisition, X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is jointly funded by the Department of Science and Technology of Henan Province (Henan Science and Technology Research Project, grant numbers 232102111124 and 222102320080), and the Department of Education of Henan Province (Key Scientific Research Project of Colleges and Universities in Henan Province, grant number 22A210013).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- El-Salhy, A.F.M.; Masoud, A.A.; Gouda, F.E.-Z.; Saeid, W.T.; El-Magid, A.; Emad, A.J.A.J.o.A.S. Effect of foliar spraying of calcium and boron nano-fertilizers on growth and fruiting of certain pomegranate cultivars. 2022, 53, 123-138.

- Isas, A.S.; Balcells, M.F.; Galdeano, C.M.; Palomo, I.; Rodriguez, L.; Fuentes, E.; Pizarro, P.L.; Briz, R.M.; Mozzi, F.; Nieuwenhove, C.V.J.F.C. Fermented pomegranate juice enriched with pomegranate seed oil ameliorates metabolic disorders associated with a high-fat diet in C57BL/6 mice. 2025, 463. [CrossRef]

- Reid, J.F.; Zhang, Q.; Noguchi, N.; Dickson, M.J.C.; agriculture, e.i. Agricultural automatic guidance research in North America. 2000, 25, 155-167. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, F.; Wei, B.; Li, L. A comprehensive review of one-stage networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing, Communications and Computing (ICSPCC), 2021; pp. 1-6.

- Zeng, T.; Li, S.; Song, Q.; Zhong, F.; Wei, X.J.C.; agriculture, e.i. Lightweight tomato real-time detection method based on improved YOLO and mobile deployment. 2023, 205, 107625. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Ding, H.; Yang, Z.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Bao, L.J.I.C.V. TRC-YOLO: A real-time detection method for lightweight targets based on mobile devices. 2022, 16, 126-142.

- Zhao, J.; Du, C.; Li, Y.; Mudhsh, M.; Guo, D.; Fan, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, X.; Almodfer, R.J.S.R. YOLO-Granada: A lightweight attentioned Yolo for pomegranates fruit detection. 2024, 14, 16848. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023; pp. 7464-7475.

- Xiao, B.; Nguyen, M.; Yan, W.Q.J.M.T.; Applications. Fruit ripeness identification using YOLOv8 model. 2024, 83, 28039-28056. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Yeh, I.-H.; Mark Liao, H.-Y. Yolov9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, 2025; pp. 1-21.

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G.J.a.p.a. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. 2024.

- Wu, D.; Lv, S.; Jiang, M.; Song, H.J.C.; Agriculture, E.i. Using channel pruning-based YOLO v4 deep learning algorithm for the real-time and accurate detection of apple flowers in natural environments. 2020, 178, 105742. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Nagarathna; Flammini, F.J.A. YOLO-based light-weight deep learning models for insect detection system with field adaption. 2023, 13, 741. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Yun, L.; Cheng, F.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, C.J.A. Light-YOLO: A Lightweight and Efficient YOLO-Based Deep Learning Model for Mango Detection. 2024, 14, 140. [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Ren, R.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, S.J.A. Intelligent Detection of Muskmelon Ripeness in Greenhouse Environment Based on YOLO-RFEW. 2024, 14, 1091. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, W.; Gao, S.; Deng, Z.J.C.; Agriculture, E.i. Strawberry ripeness detection based on YOLOv8 algorithm fused with LW-Swin Transformer. 2023, 215, 108360. [CrossRef]

- Vasumathi, M.; Kamarasan, M.J.I.J.C.S.E. An LSTM based CNN model for pomegranate fruit classification with weight optimization using Dragonfly Technique. 2021, 12, 371-384.

- Mitkal, P.S.; Jagadale, P.A.B.J.I.J.o.A.R.i.S., Communication; Technology. Grading of Pomegranate Fruit using CNN. 2023.

- Naseer, A.; Amjad, M.; Raza, A.; Munir, K.; Samee, N.A.; Alohali, M.A.J.I.A. A novel transfer learning approach for detection of pomegranates growth stages. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Wang, H.; Chen, P.; Wei, Z. Mixed pooling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the Rough Sets and Knowledge Technology: 9th International Conference, RSKT 2014, Shanghai, China, October 24-26, 2014, Proceedings 9, 2014; pp. 364-375.

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024; pp. 16965-16974.

- Zhao, J.; Almodfer, R.; Wu, X.; Wang, X.J.D.i.B. A dataset of pomegranate growth stages for machine learning-based monitoring and analysis. 2023, 50, 109468. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Wei, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhan, Z.; Ren, Q.J.a.p.a. Slim-neck by GSConv: A better design paradigm of detector architectures for autonomous vehicles. 2022.

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020; pp. 10781-10790.

- Xu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.J.a.p.a. Damo-yolo: A report on real-time object detection design. 2022.

- Peng, Y.; Sonka, M.; Chen, D.J.a.p.a. U-Net v2: Rethinking the skip connections of U-Net for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2023.

- Liu, Y.; Shao, Z.; Hoffmann, N.J.a.p.a. Global attention mechanism: Retain information to enhance channel-spatial interactions. 2021.

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018; pp. 3-19.

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020; pp. 11534-11542.

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021; pp. 13713-13722.

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W.; et al. YOLOv6: A Single-Stage Object Detection Framework for Industrial Applications. 2022, abs/2209.02976.

Figure 1.

Comparison of structures between Convolution and DPDM(Note: Conv denotes convolution, norm denotes normalization, the same as below. (a) is DPDM downsampling. First, the input feature image X is operated by Max pooling, then the input feature graph is divided into two sub-feature graphs X1 and X2 along the channel dimension. Finally, the two sub-feature graphs are Concat concatenated, and the feature graph X3 is output. (b) is the standard convolution downsampling, which is realized from the input feature image through a series of operations such as convolution operation, batch normalization acceleration training process and introduction of nonlinear characteristics through activation function.).

Figure 1.

Comparison of structures between Convolution and DPDM(Note: Conv denotes convolution, norm denotes normalization, the same as below. (a) is DPDM downsampling. First, the input feature image X is operated by Max pooling, then the input feature graph is divided into two sub-feature graphs X1 and X2 along the channel dimension. Finally, the two sub-feature graphs are Concat concatenated, and the feature graph X3 is output. (b) is the standard convolution downsampling, which is realized from the input feature image through a series of operations such as convolution operation, batch normalization acceleration training process and introduction of nonlinear characteristics through activation function.).

Figure 2.

The encoder structure of the variants (SSE denotes single scale transformer encoder, CSF denotes cross scale fusion, AIFI and CCFM are two modules designed in our hybrid encoder).

Figure 2.

The encoder structure of the variants (SSE denotes single scale transformer encoder, CSF denotes cross scale fusion, AIFI and CCFM are two modules designed in our hybrid encoder).

Figure 3.

CCFM structure.

Figure 3.

CCFM structure.

Figure 4.

YOLO-Punica structure (Note: Conv represents convolution operation, and DPDM represents our pro-posed Dual Path Downsampling Module. The Concat operation represents the merging of feature graphs, which step can improve the dimensionality of the features while not add extra parameter arithmetic when compared to the Add operation.).

Figure 4.

YOLO-Punica structure (Note: Conv represents convolution operation, and DPDM represents our pro-posed Dual Path Downsampling Module. The Concat operation represents the merging of feature graphs, which step can improve the dimensionality of the features while not add extra parameter arithmetic when compared to the Add operation.).

Figure 5.

The images of pomegranate flowers and fruits at different development stages Network model performance evaluation metrics.

Figure 5.

The images of pomegranate flowers and fruits at different development stages Network model performance evaluation metrics.

Figure 6.

Comparison of performance of different models in ablation experiments.

Figure 6.

Comparison of performance of different models in ablation experiments.

Figure 7.

Performance comparison of CCFM+different backbone network models.

Figure 7.

Performance comparison of CCFM+different backbone network models.

Figure 8.

Comparison of detection results of the YOLO-Punica model.

Figure 8.

Comparison of detection results of the YOLO-Punica model.

Figure 9.

Comparison of detection performance between the original model and YOLO-Punica model in the bud and flower stages of pomegranate.

Figure 9.

Comparison of detection performance between the original model and YOLO-Punica model in the bud and flower stages of pomegranate.

Figure 10.

Comparison of detection performance between the original model and YOLO-Punica model in the mid-term and mature fruit stages of pomegranate.

Figure 10.

Comparison of detection performance between the original model and YOLO-Punica model in the mid-term and mature fruit stages of pomegranate.

Figure 11.

Detection results of pomegranate at different development stages in complex environments.

Figure 11.

Detection results of pomegranate at different development stages in complex environments.

Figure 12.

Detection results of pomegranate fruit in complex environments with obstruction.

Figure 12.

Detection results of pomegranate fruit in complex environments with obstruction.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of YOLOv8n backbone network with different Neck parts.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of YOLOv8n backbone network with different Neck parts.

| Model(YOLO) |

GFLOPs |

Size |

Parameters |

Precision |

Recall |

F1(%) |

mAP@0.5 |

| V8n |

8.2 |

6.1 |

3006623 |

0.913 |

0.839 |

87.4 |

0.917 |

| +SLim-Neck |

7.3 |

5.9 |

2799135 |

0.905 |

0.841 |

87.2 |

0.912 |

| +BiFPN |

8.1 |

5.9 |

2783595 |

0.918 |

0.846 |

87.9 |

0.919 |

| +RepGFPN |

8.4 |

6.9 |

3287647 |

0.934 |

0.835 |

88.1 |

0.914 |

| +SDI |

15.4 |

10.1 |

4933471 |

0.903 |

0.896 |

82.3 |

0.916 |

| +CCFM |

6.6 |

4.2 |

1965471 |

0.906 |

0.842 |

87.3 |

0.919 |

Table 2.

Performance comparison with different attention mechanisms in modified backbone networks.

Table 2.

Performance comparison with different attention mechanisms in modified backbone networks.

| Model(YOLO) |

GFLOPs |

Size |

Parameters |

Precision |

Recall |

F1(%) |

mAP@0.5 |

| CCFM |

6.6 |

4.2 |

1965471 |

0.906 |

0.842 |

87.3 |

0.912 |

| +GAM |

12.5 |

9.7 |

4724703 |

0.926 |

0.824 |

87.2 |

0.913 |

| +CBAM |

11.2 |

6.6 |

3150913 |

0.907 |

0.851 |

87.8 |

0.917 |

| +ECA |

11.2 |

6.4 |

3085026 |

0.903 |

0.849 |

87.5 |

0.915 |

| +CoordAtt |

11.2 |

6.5 |

3091703 |

0.916 |

0.851 |

88.2 |

0.916 |

| +DPDM(ours) |

5.9 |

3.4 |

1629343 |

0.923 |

0.856 |

88.7 |

0.926 |

Table 3.

Ablation experiment.

Table 3.

Ablation experiment.

| Model(YOLO) |

GFLOPs |

Size |

Parameters |

Precision |

Recall |

F1(%) |

mAP@0.5 |

| YOLOv8n |

8.2 |

5.97 |

3006623 |

91.3 |

0.839 |

87.4 |

0.917 |

| YOLOv8n+CCFM |

6.6 |

4.2 |

1965471 |

0.906 |

0.842 |

87.3 |

0.919 |

| YOLOv8n+DPDM |

7.2 |

5.19 |

2590623 |

0.929 |

0.858 |

89.1 |

0.929 |

| YOLOv8n+CCFM+DPDM |

5.9 |

3.4 |

1629343 |

0.923 |

0.856 |

88.7 |

0.926 |

Table 4.

Comparison of detection results of the YOLO-Punica model.

Table 4.

Comparison of detection results of the YOLO-Punica model.

| Model(YOLO) |

Parameters |

GFLOP |

Size(MB) |

F1(%) |

mAP@0.5 |

FPS(f/s) |

| YOLOv5 |

V5s |

7,023,610 |

15.8 |

13.8 |

89.49 |

0.929 |

7.19 |

| V5m |

20,869,098 |

48 |

40.3 |

89.35 |

0.926 |

3.43 |

| V5l |

46,129,818 |

107.9 |

88.5 |

89.46 |

0.93 |

1.79 |

| V5x |

86,200,330 |

204.1 |

165.1 |

89.73 |

0.932 |

1.10 |

| Granada |

3,843,771 |

9.1 |

7.7 |

87.84 |

0.922 |

8.66 |

| YOLOv6 |

V6s |

16,298,399 |

44 |

31.3 |

87.38 |

0.925 |

6.90 |

| V6m |

51,980,095 |

161.2 |

99.5 |

88.31 |

0.927 |

2.53 |

| V6l |

110,865,631 |

391.2 |

211.9 |

89.11 |

0.926 |

1.17 |

| v6x |

172,985,727 |

610.3 |

330.5 |

88.44 |

0.929 |

0.79 |

| YOLOv7 |

V7 |

36,503,348 |

103.2 |

71.3 |

90.07 |

0.942 |

1.40 |

| V7-tiny |

6,018,420 |

13.1 |

11.7 |

89.27 |

0.929 |

7.82 |

| V7x |

70,809,396 |

188.1 |

135.6 |

90.63 |

0.948 |

1.12 |

| YOLOv8 |

V8n |

3,006,623 |

8.2 |

6.1 |

87.44 |

0.917 |

12.4 |

| V8s |

11,137,532 |

28.4 |

21.5 |

89.11 |

0.927 |

7.2 |

| V8m |

25,842,655 |

78.7 |

52.1 |

89.29 |

0.929 |

3.5 |

| V8l |

43,610,463 |

164.8 |

83.6 |

89.68 |

0.931 |

2.0 |

| V8x |

68,128,383 |

257.4 |

136.8 |

90.06 |

0.933 |

1.4 |

| YOLOv9 |

V9c |

25,323,103 |

102.3 |

51.6 |

90.03 |

0.931 |

2.2 |

| YOLOv10 |

V10s |

8,038,830 |

24.5 |

15.8 |

87.11 |

0.899 |

6.0 |

| V10b |

20,418,862 |

98.0 |

41.5 |

87.59 |

0.910 |

2.3 |

| YOLO-Punica |

Punica |

1,629,343 |

5.9 |

3.4 |

88.72 |

0.926 |

14.3 |

Table 5.

YOLO-Punica test results.

Table 5.

YOLO-Punica test results.

| Class |

Labels |

Precision |

Recall |

F1 |

mAP@0.5 |

| bud |

265 |

0.934 |

0.781 |

85.1 |

0.898 |

| flower |

277 |

0.91 |

0.878 |

89.4 |

0.942 |

| early-fruit |

151 |

0.914 |

0.845 |

87.8 |

0.906 |

| mid-growth |

321 |

0.917 |

0.85 |

88.2 |

0.915 |

| ripe |

206 |

0.925 |

0.937 |

93.1 |

0.976 |

| all |

1220 |

0.923 |

0.847 |

88.3 |

0.926 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).