1. Introduction

In intelligent mechanical harvesting operations, fruit recognition technology provides discriminative power for enhancing crop management efficiency and optimizing resource allocation [

1,

2]. Loquat, an important economic crop, is widely cultivated in regions such as Sichuan, Fujian, and Zhejiang Province. It not only holds a significant position in agricultural production but also plays a vital role in promoting regional economic development and increasing farmers’ income [

3,

4]. Traditional loquat recognition and harvesting techniques primarily rely on manual inspection and picking, which has obvious efficiency limitations. On the other hand, it is difficult to adapt to the requirements of modern agricultural large-scale production. Fruit loss caused by untimely harvesting further increases the overall production cost [

5,

6]. Additionally, under natural lighting conditions, leaf obstruction, and fruit overlap, the conventional image analysis methods and machine learning-based recognition technologies face significant challenges, making it difficult to achieve precise loquat localization and identification. Against this backdrop, the development of intelligent recognition algorithms that are highly accurate, fast, and lightweight has become a key technological breakthrough in improving the automation level of loquat harvesting equipment.

Over the past decade, the field of agricultural computer vision has witnessed remarkable progress, with deep learning architectures based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) emerging as the mainstream technology for fruit detection tasks. Significant breakthroughs have been achieved in enhancing detection accuracy and system reliability, providing effective technical support for automated fruit harvesting [

7,

8,

9,

10]. However, existing methods still exhibit notable disparities and room for optimization in balancing lightweight design, detection speed, and recognition accuracy.

The YOLO-PEM model proposed by Jing et al. [

11] integrates PConv operations and EMA attention mechanisms into its backbone network while employing the MPDIoU loss function. It demonstrates high computational efficiency in peach recognition tasks, though its lightweight convolutional structure may somewhat limit feature extraction capabilities. Deng et al. [

12] constructed the YOLOv7-BiGS model, which achieves precise recognition of citrus targets by introducing BiFormer attention modules and GSConv convolutions. However, the model’s inference speed in practical deployment has not been fully evaluated. Yu et al. [

13] restructured the YOLOv5s backbone based on MobileNet, significantly reducing model complexity and boosting detection speed. However, its accuracy stability in complex orchard scenarios with severe occlusions remains to be enhanced. Lü et al. [

14] embedded the MobileOne module, Coordinate Attention (CA) mechanism, and lightweight SPPFCSPC structure into YOLOv7, achieving 97.2% detection accuracy in grape recognition. However, the model’s overall parameter count and computational cost remain high, limiting its potential application on mobile harvesting equipment. Sun et al. [

15] constructed the YOLO-P model by introducing a shuffle module, CBAM attention mechanism, and Hard-Swish activation function, achieving 97.6% mAP in pear detection. However, its insufficient lightweight design struggles to meet real-time operational demands. Liu et al. [

16] developed the Faster-YOLO-AP model, utilizing PDWFasterNet and Deep-Weakly Separable Convolution (DWSConv) for lightweight optimization and acceleration. However, it did not sufficiently address maintaining recognition accuracy for apple targets in complex environments.

In summary, while the research by Jing, Deng, Yu et al. advanced fruit recognition technology and demonstrated advantages in detection accuracy, speed, or lightweight design individually, none achieved a systematic balance among these three aspects. Particularly in complex orchard scenarios, existing models exhibit significant shortcomings in the coordinated optimization of real-time performance and robustness. Loquat harvesting operations demand detection models that simultaneously exhibit high accuracy, fast speed, and lightweight characteristics, but there are currently relatively few studies on this type of fruit. However, challenges such as overlapping branches and leaves, along with fruit occlusion in natural growing environments, further increase recognition difficulty. To address these challenges, this study proposes a lightweight detection model based on YOLO-MCS, aiming to achieve a better balance between accuracy, speed, and model complexity. Through structural optimization and modular innovation, this model significantly reduces computational costs while maintaining high detection performance, meeting the real-time operational demands of loquat harvesting machinery in complex environments. This research not only provides an efficient and reliable solution for loquat recognition but also contributes to enhancing agricultural productivity and advancing the intelligent and modern development of the fruit tree industry. Here, “MCS” represents the initial letters of the model’s three core modules: “M” originates from the MBConv core component of EfficientNet-b0, “C” denotes the C2f_SCConv module, and “S” stands for the SimAm attention mechanism.

This study’s core research contents are summarized as follows.

(1) Lightweight Backbone Network: Replacing the original main network with EfficientNet-b0 addresses fruit occlusion by branches and leaves while reducing model parameters and computational load, balancing detection speed and accuracy.

(2) Feature Extraction Optimization: Replacing the bottleneck structure in the C2f module with SCConv modules enhances the model’s multi-scale feature extraction capability for densely clustered fruits by reducing spatial and channel redundancy.

(3) Feature Focus Enhancement: Introduces the SimAm attention mechanism in the detection head. Through feature recalibration strategies, it strengthens the model’s ability to focus on loquat targets within complex backgrounds.

2. Material Preparation and Experimental Process

This section will detail the material preparation and complete experimental workflow required for this research. It primarily covers the acquisition specifications for the loquat image dataset used in the experiments, as well as the technical approach and experimental methods employed for analyzing and processing the collected data.

2.1. Loquat Image Collection

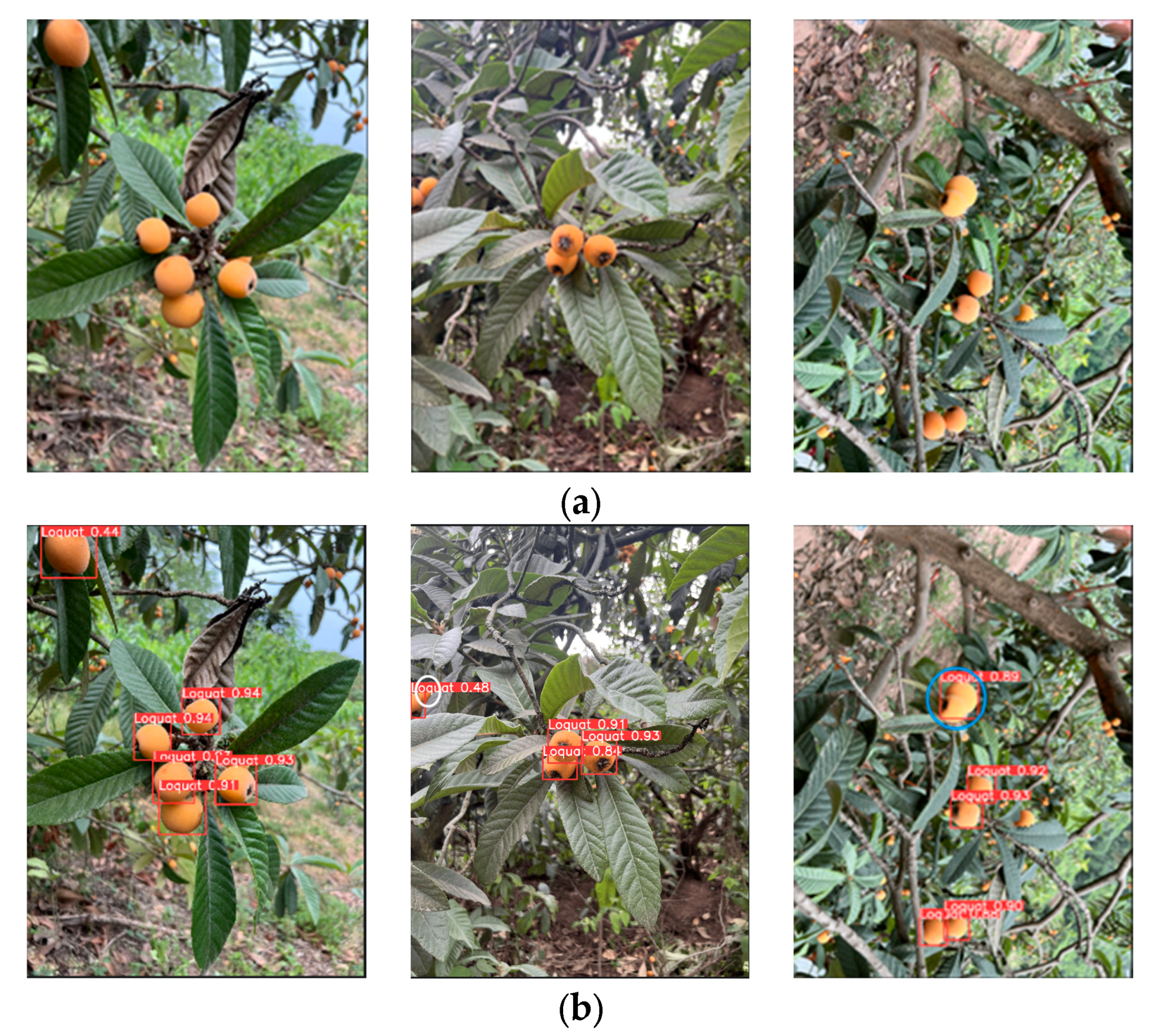

This study’s loquat dataset was collected at the Loquat Industrial Park in Longquanyi District, Chengdu City, Sichuan Province, during the period from April 5 to May 1, 2025 (10:00 to 18:00). The loquat industrial park employs dwarf loquat trees with fixed-distance and high-density planting structures, which facilitate the harvesting of loquat fruits. Owing to the complex background noise in natural scenes and the severe mutual occlusion between loquat targets, different shooting angles, distances (10 cm–100 cm), light intensities, front lighting, back lighting, and varying degrees of occlusion conditions (branch occlusion, fruit mutual occlusion, and leaf occlusion) were selected during image capture. This significantly improved the representational diversity of the dataset and effectively enhanced the model’s generalization performance. Images with high blur and similarity, or incorrect capture were removed from the dataset, resulting in 325 high-quality original loquat fruit images. The loquat image dataset is shown in

Figure 1.

2.2. Dataset Creation

The image annotation for this study was performed independently by a single researcher. This approach eliminates inconsistencies between annotators at the source; furthermore, all annotations underwent unified review to ensure the accuracy of the benchmark dataset. The LabelImg software was used to manually annotate the images of loquat fruits collected under natural conditions. The category of the bounding box attribute was set as “Loquat”, and the txt label file containing the information of the bounding box position was obtained. During the data collection phase, due to interference from environmental noise, lighting changes, and other factors, this study systematically expanded the original loquat dataset. By introducing diverse data augmentation strategies, the model was able to fully learn the multidimensional feature representations of loquat fruits in sophisticated natural scenes, thereby remarkably improving the model’s generalization performance within varying surroundings. Specifically, this study employed five data augmentation methods: image sharpening; horizontal and vertical flipping; random rotation (0–360 degrees); Gaussian noise injection; and dynamic brightness adjustment. After data augmentation, the dataset was expanded to 1,950 high-quality images. The completed dataset was randomly divided into training, validation, and test sets in an 8:1:1 ratio, resulting in 1,560 images for the training set, 195 images for the validation set, and 195 images for the test set, as shown in

Table 1.

Figure 2 shows typical samples processed using different augmentation methods.

2.3. YOLOv8n Model

The YOLOv8 object detection framework comprises five models, namely n, s, m, l, and x, and each of them is customized to suit distinct application needs. These models exhibit an increasing trend in network depth and complexity, with corresponding improvements in detection precision. Among them, the YOLOv8n model stands out for its optimal balance between parameter count and detection precision. Based on these characteristics, the present investigation incorporated YOLOv8n as the base model for the loquat fruit recognition after comprehensive consideration. As shown in

Figure 3, YOLOv8n adopts a streamlined and efficient network architecture, significantly reducing computational intricacy while maintaining detection capability.

The YOLOv8n network architecture adopts a four-module design, comprising a data input layer, a feature extraction backbone, a feature fusion neck, and a task decoupling head [

17]. The feature extraction backbone is composed of five standard convolutional layers, four C2f modules, and one multi-scale pooling structure. The C2f modules are optimised based on the ELAN architecture of YOLOv7, enhancing the number of cross-layer connection branches to significantly improve gradient information flow efficiency, thereby constructing feature learning units with stronger representational capabilities [

18]. The multi-scale pooling structure adopts a cascaded spatial pyramid pooling strategy to effectively integrate feature information from different receptive fields. The feature fusion neck employs a Path Aggregation Network (PAN) to facilitate multi-level feature interaction, significantly promoting the model’s detection capability for multi-scale objects [

19]. The task processing head adopts a decoupled structure, featuring distinct branches for classification and regression. Compared to traditional coupled structures, this design achieves simultaneous improvements in detection precision and efficiency through task-specific processing mechanisms.

2.4. YOLO-MCS Model

Although the YOLOv8n algorithm combines high detection precision with a lightweight model, its detection performance still has certain limitations in orchard scenarios, particularly in complex situations such as dense distribution of loquat fruits, mutual occlusion between fruits, and overlap with branches. This study entails the implementation of specific optimizations within the YOLOv8n framework to improve the algorithm’s efficacy in detecting loquat targets within orchard environments. Firstly, the specific enhancement is the substitution of the initial design with the lightweight EfficientNet-b0 architecture in the primary network, which greatly decreases the model’s complexity; secondly, SCConv convolutional layers in the feature extraction module are embedded to suppress redundant features through a feature re-calibration mechanism; finally, the neck network integrates the SimAm to strengthen the response to key features. The improved YOLO-MCS model maintains real-time performance while effectively improving detection precision and robustness. Its overall architecture is shown in

Figure 4.

2.4.1. EfficientNet-b0 Feature Extraction Network

Given the constrained computational capabilities of terminal devices in loquat recognition, it is imperative to evaluate the precision of recognition as well as overall model performance, necessitating a balance between these two factors. Efficient networks such as GhostNet [

20], ShuffleNetV2 [

21], and MobilenetV3 [

22] achieve model compression through structural optimization and employ mechanisms of reuse and reorganization to enhance their ability to represent high-dimensional nonlinear features, thereby significantly improving the computational efficiency of the algorithm. In comparison, the EfficientNet-b0 model stands out for its small parameter count and high recognition precision [

23]. This advantage primarily stems from the composite scaling method employed by the EfficientNet-b0 model, which uses a composite scaling coefficient (

φ) to simultaneously optimise three dimensions: network depth (

d), width (

w), and input image resolution (

r). The composite scaling formula for the EfficientNet-b0 model is shown in Equation (1).

In this architectural configuration, the parameters

d,

w, and

r respectively denote the scaling coefficients for network depth, channel width, and input resolution, whereas

α,

β, and

γ represent hyperparameters optimized via neural architecture search. The EfficientNet-b0 model mainly composes of convolutional layers, mobile inverted bottleneck convolutions (MBConv), pooling layers, and fully connected layers [

24], with its network structure outlined in

Table 2.

According to the analysis of the architecture parameters in

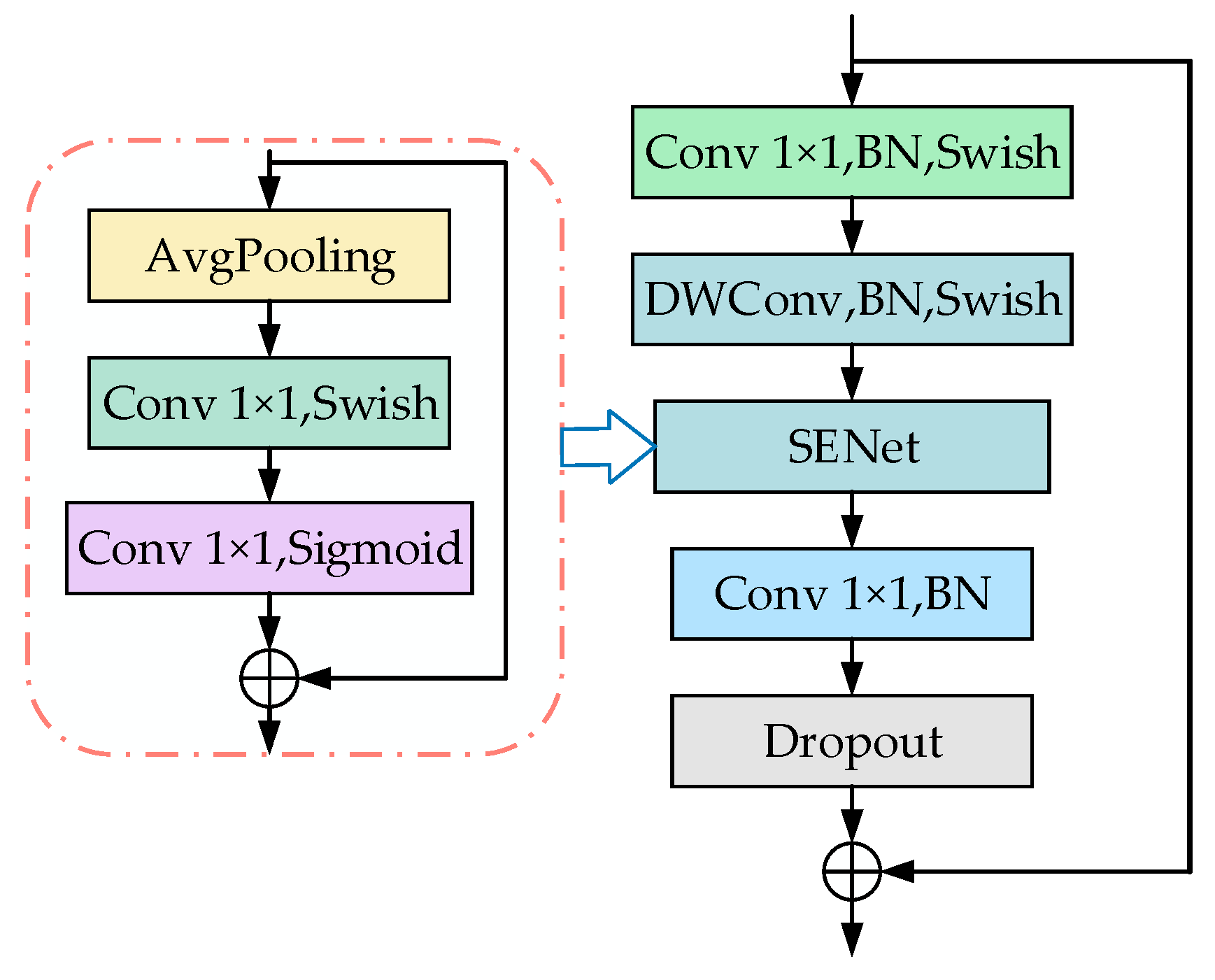

Table 1, the central element of the EfficientNet-b0 model is the MBConv, whose detailed structure is shown in

Figure 5. The MBConv module initially employs convolution on the input feature map to modify its channel dimension. Subsequently, depthwise convolution is utilized to perform spatial filtering on the features with reduced dimensions, significantly decreasing the number of model parameters. Thereafter, the channel attention mechanism, known as the SE module, is integrated to enhance the response strength of the loquat’s key features through feature re-calibration [

25]. Finally, the feature representation undergoes dimensional restoration through pointwise convolution, followed by application of dead connections and skip connections.

2.4.2. C2f_SCConv Convolution Module

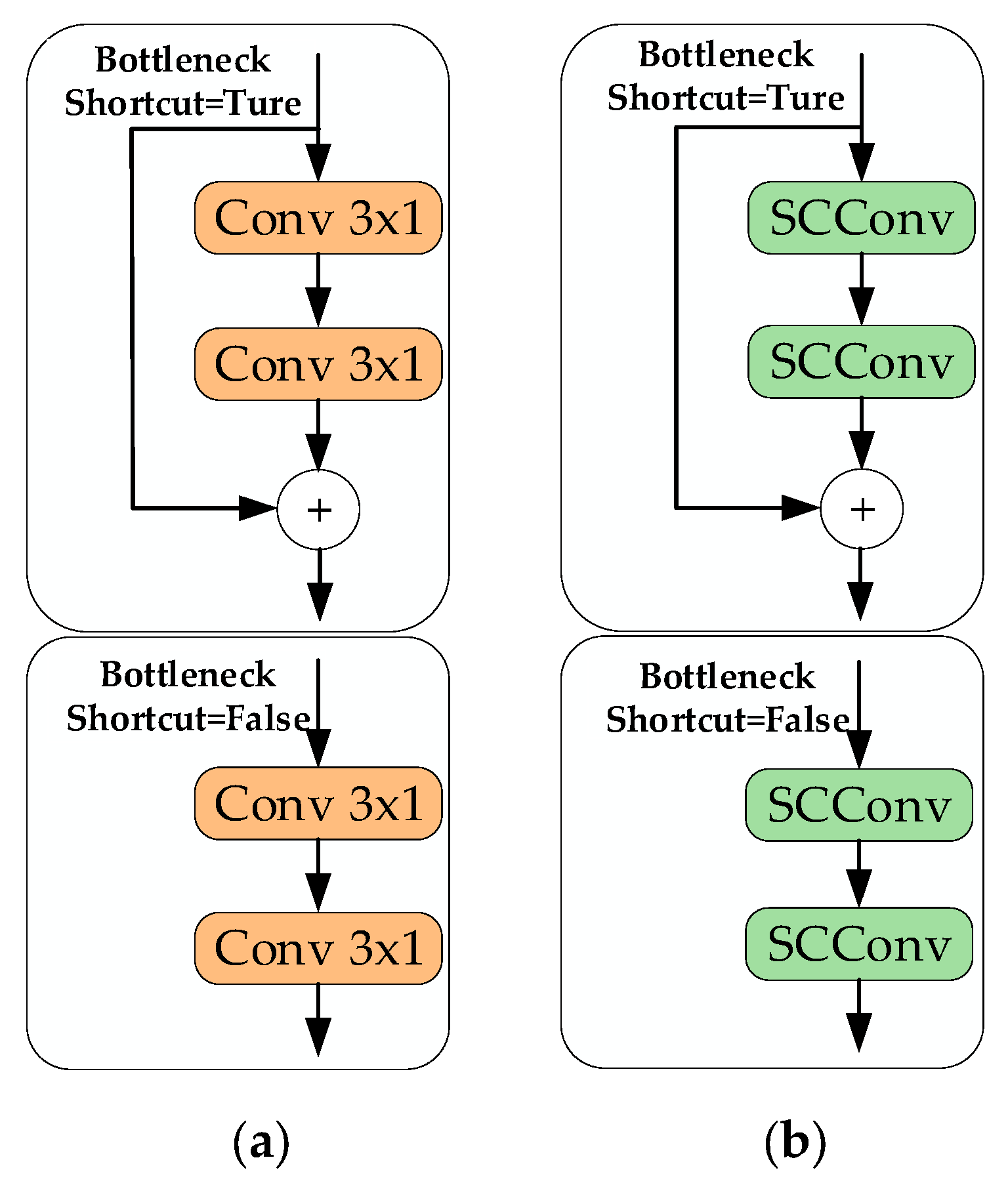

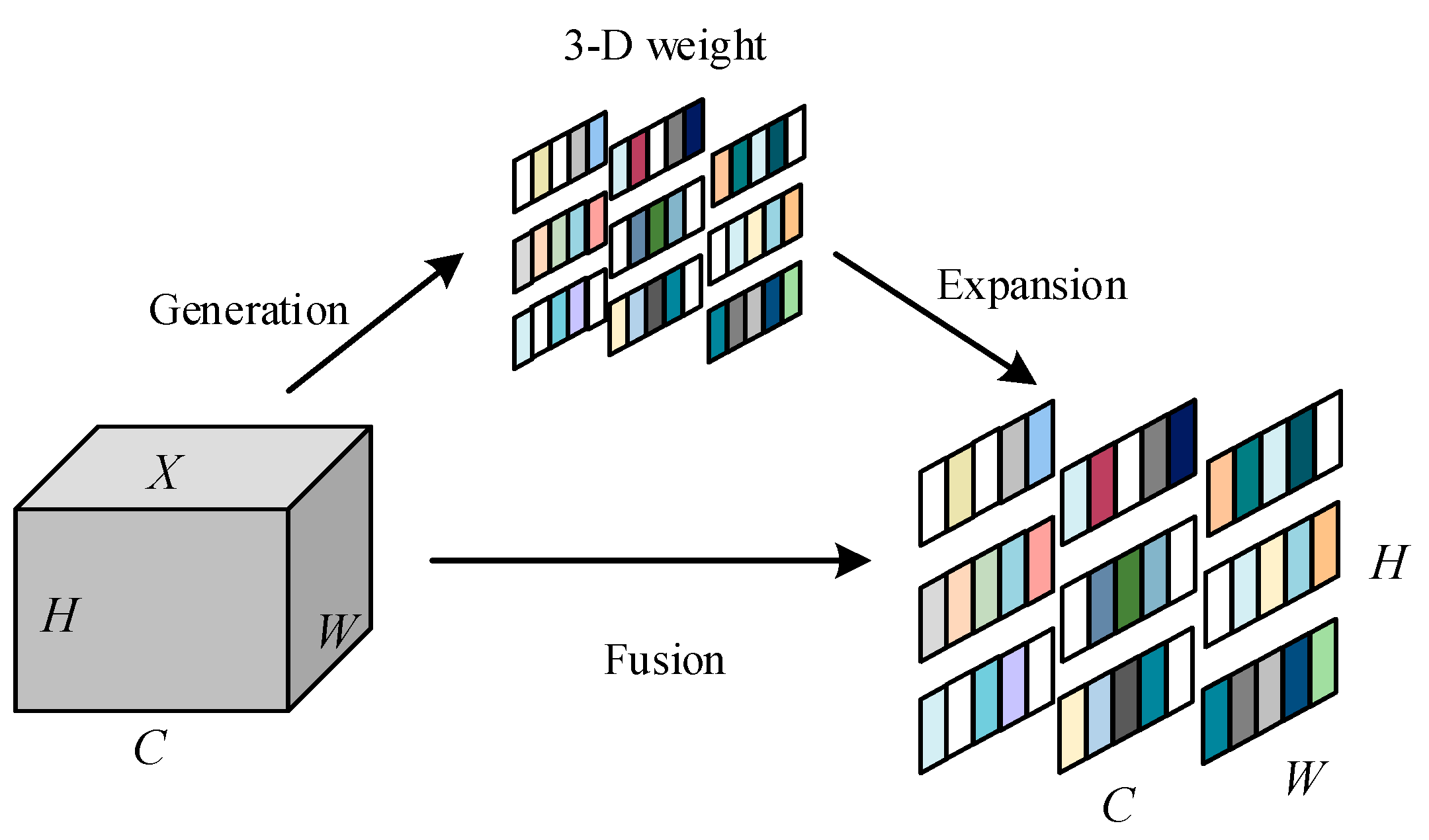

This research incorporates a spatial recombination convolution (SCConv) module [

26] into the head to improve the detection model’s representation capabilities by substituting the bottleneck unit of the standard C2f architecture. This enhancement effectively reduces information redundancy during feature extraction by employing feature decoupling and channel recombination techniques, which in turn significantly boosts the model’s recognition precision. Specific improvements to the module are shown in

Figure 6.

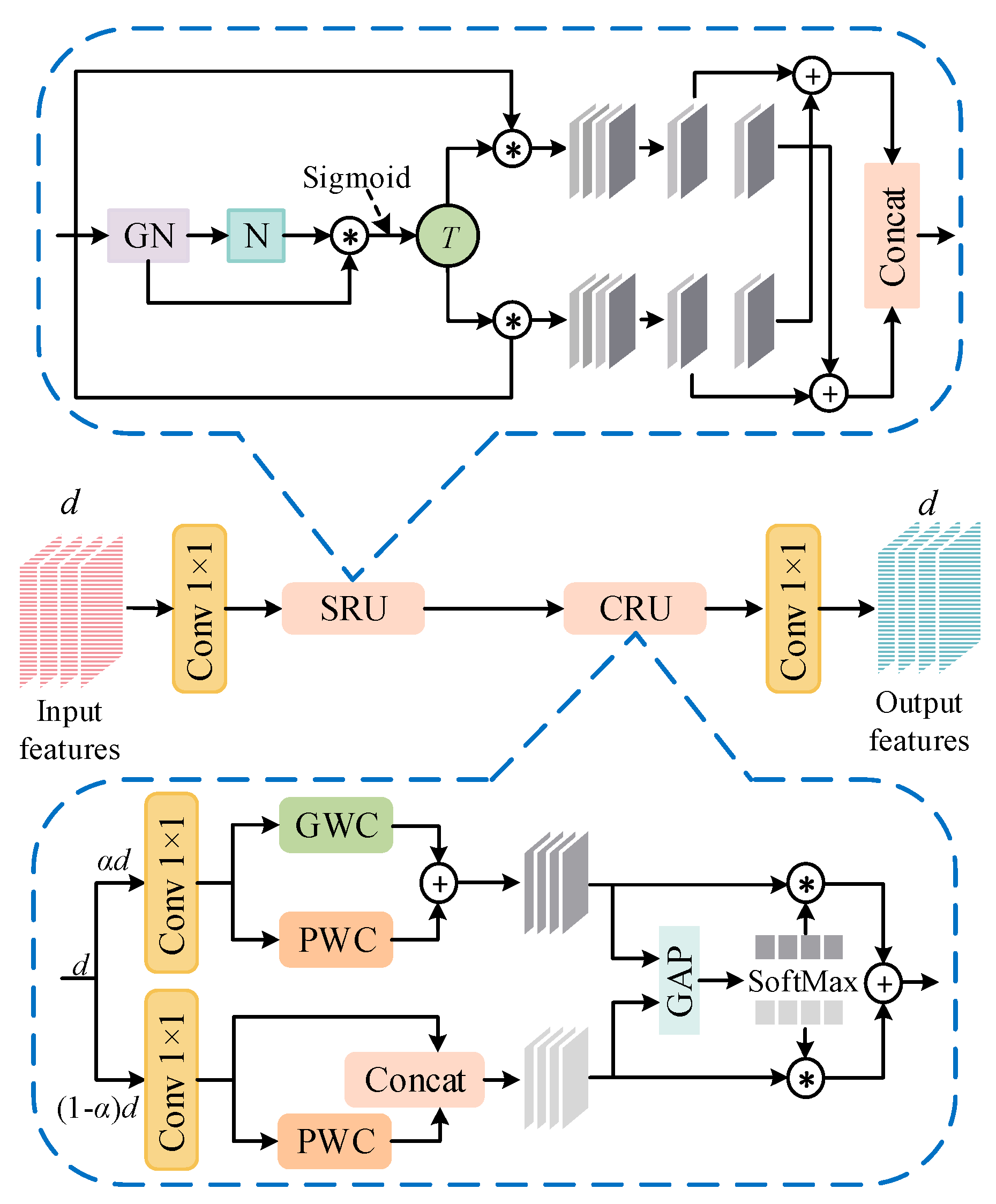

The SCConv module significantly reduces feature redundancy by jointly optimizing the spatial and channel dimensions, achieving lightweight goals while ensuring model precision. The specific architecture design of the module is shown in

Figure 7.

The SCConv module adopts a dual-branch feature optimization architecture, whose core components include a spatial reconstruction unit (SRU) and a channel reconstruction unit (CRU). The SRU extracts importance coefficients of feature maps through group normalization, separates useful and redundant feature maps, performs cross-reconstruction on these features, and finally concatenates the reconstructed features to generate spatially optimized feature maps. The SRU effectively minimizes redundancy in the spatial dimension while boosting the expressive capability of features. Meanwhile, the CRU separates the input features by channel, utilizing group-wise convolution (GWC) to capture high-level information and point-wise convolution (PWC) to obtain detailed information. Then, it uses global average pooling (GAP) to generate channel descriptors, calculates weights using SoftMax, and finally fuses the information from different channels with weights to generate channel-optimized features. The CRU effectively reduces channel redundancy, enhances feature representation capabilities, lowers computational costs, and improves model inference speed through its “segmentation-transformation-fusion” approach.

2.4.3. SimAm Attention Mechanism Module

SimAm is an unparameterized attention module that innovatively achieves collaborative optimization of spatial and channel attention. This approach creates a three-dimensional model for distributing weights, assigning distinct saliency weights to each neuron within the feature map. This significantly enhances the ability to represent features without adding extra parameters [

27].

Figure 8 shows the detailed architecture of this attention module.

In SimAm, an energy function et characterizes each neuron, whose definition is shown in equations (2), (3), (4), (5) and (6).

Among these, wt and bt represent the weights and bias terms; y denotes the expected output of the target neuron; xi refers to the input features from other neurons; yt and y0 represent the output of the target neuron and the expected output of other neurons in the input features, respectively; and denote the linear transformations of the input features t and xi on the same channel for the target neuron and the i-th other neuron with respect to wt and bt; N denotes the number of energy functions; M denotes the total number of neurons in the channel; μt and represent the mean activation and dispersion measure, respectively, across the channel containing the target neuron; λ is the regularization coefficient.

This study choses to integrate the SimAm into the neck network of YOLOv8n, primarily based on the following three considerations: 1) The loquat fruit dataset often presents challenges such as dense occlusions, small target sizes, and intricate environments. By incorporating the attention mechanism, it becomes possible to minimize interference from extraneous factors, retain the essential feature information of the identified targets, and significantly decrease both the false negative and false positive rates. 2) SimAm is a highly efficient, unparameterized attention which seamlessly integrates with various architectures. It can be widely applied to different convolutional neural network designs, significantly enhancing the model’s overall performance. 3) In the YOLOv8n network, the Neck structure is a pivotal component in feature processing, which is positioned between the backbone network and the output layer. Its function is to integrate the target features extracted by the backbone network. By integrating the SimAm attention module into the Neck structure, it is possible to effectively reduce background noise, enhance the fusion of multi-scale features, and boost the detection performance for small objects [

28].

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

The following section will first detail the experimental hardware configuration, software environment, and parameter settings to ensure reproducibility of the experimental process. Building upon this foundation, we will then conduct a systematic analysis of the model’s training results and performance metrics.

3.1. Experimental Platform and Parameter Settings

This study was conducted in a deep learning environment built with the following hardware configuration: 32 GB memory, Intel Core I5-14600KF CPU, NVIDIA RTX4060 GPU, Windows 10 operating system, Python 3.9, PyTorch 2.3.0, and CUDA 12.8. The experimental parameters are shown in

Table 3. All comparative experiments were conducted under identical training conditions, specifically including: identical dataset splits, identical training epochs, identical optimizers and their hyperparameter settings (such as learning rate and weight decay), and identical learning rate scheduling strategies. This controlled variable approach ensures that any observed performance differences objectively reflect the inherent effectiveness of each model architecture, thereby guaranteeing the reliability of the comparative results.

3.2. Evaluation Criteria

All experimental models in this study were evaluated using the following metrics: precision (P), recall (R), mAP@0.5 (mAP), floating-point operations per second (GFLOPs), and number of parameters (Params) [

29]. The calculation formulas are shown in (7), (8), (9), and (10).

In the formulas: TP denotes the count of correctly identified loquat targets; FP is the number of negative classes identified as positive ones; FN is the count of positive classes identified as negative ones; AP represents the area under the P-R curve; X stands for the total number of samples within the dataset; APi denotes the average precision for the i-th class; mAP denotes the mean average precision at an IoU threshold of 0.5, where all detections with intersection-over-union ratios exceeding this threshold are counted as correct predictions, making it suitable for rapid performance evaluation under relatively lenient matching criteria.

3.3. Contrastive Investigation of Attention Mechanisms

This research assessed the practical effectiveness of the SimAm attention mechanism by comparing and analyzing its performance against CBAM [

30], efficient channel attention ECA [

31], global attention GAM [

32], incentive attention SE [

33] and Leverage Separable Kernel Attention LSKA [

34]. The detailed results of the experimental comparison are shown in

Table 3. In this experiment, the control variable method was used, and only the attention modules were embedded sequentially in the neck network of the YOLOv8n model, while keeping the other structural parameters of the network unchanged. To control for the influence of other factors, this experiment specifically selected the representative convolutional hybrid attention mechanism—LSKA—as one of the comparison methods. As shown in the experimental results in

Table 4, among these attention mechanisms, the SimAm achieved the most significant improvement in model metrics, with increases of 1.3% and 2.2% in Precision and mAP, respectively. Additionally, the number of GFLOPs and Params was reduced by 34.1% and 43.3%, respectively. Experimental findings suggest that the SimAm attention mechanism is more appropriate for the purpose of this research.

3.4. Comparison Experiment between Different Backbone Networks

This study evaluates the optimisation effects of different backbone network improvement schemes on model performance through systematic backbone comparison experiments. The experiment designed multiple control schemes, using different modules to optimise the structure of the backbone network. Detailed backbone performance comparison data are shown in

Table 5. MobileNetv3 [

35] improves feature learning and reduces computational costs through inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. Incorporating the MobileNetv3 into the network results in a reduction in model size and Params count compared to the baseline model, but it resulted in a 2.2% drop in precision. When using the ShuffleNetv2 module to improve the backbone network, the model’s precision significantly decreased, leading to reduced precision in target recognition, which did not have a positive effect on model optimization. The bottleneck in GhostNetv2 has DFC attention to enhance the feature representation of its intermediate layers, making it a lightweight backbone network. However, when using the GhostNetv2 module to improve the backbone network, although the precision and recall rate increased, the number of Params and GFLOPs also increased, and the improvement effect was not ideal for the lightweight of the model. The reason is that GhostNetV2’s decoupled fully-connected attention excels at capturing global context, which benefits image-level classification but may weaken the spatial details required for object detection. In contrast, EfficientNet-b0 generates a feature pyramid with clear hierarchy and rich details through balanced scaling and MBConv modules, making it more conducive to bounding box localization. In our improved architecture, the SCConv and SimAm modules in the Head section form a “feature refinement and focus” system. When paired with EfficientNet-b0 as the backbone, its rich features synergize positively with the Head: SCConv effectively reduces redundancy, while SimAm precisely locates key regions. However, GhostNetV2’s inherently “sparing” features may interact negatively with SCConv’s redundancy reduction, further weakening localization information. This makes it difficult for SimAm to compensate, ultimately leading to a decrease in mAP. This study uses EfficientNet-b0 to improve the backbone network, reducing the number of Params by 43.3% and the number of GFLOPs by 34.1%, while improving the Precision and mAP by 1.3% and 2.2%, respectively. The precision of the model in identifying loquat fruits was maintained while reducing the number of parameters and floating-point calculations.

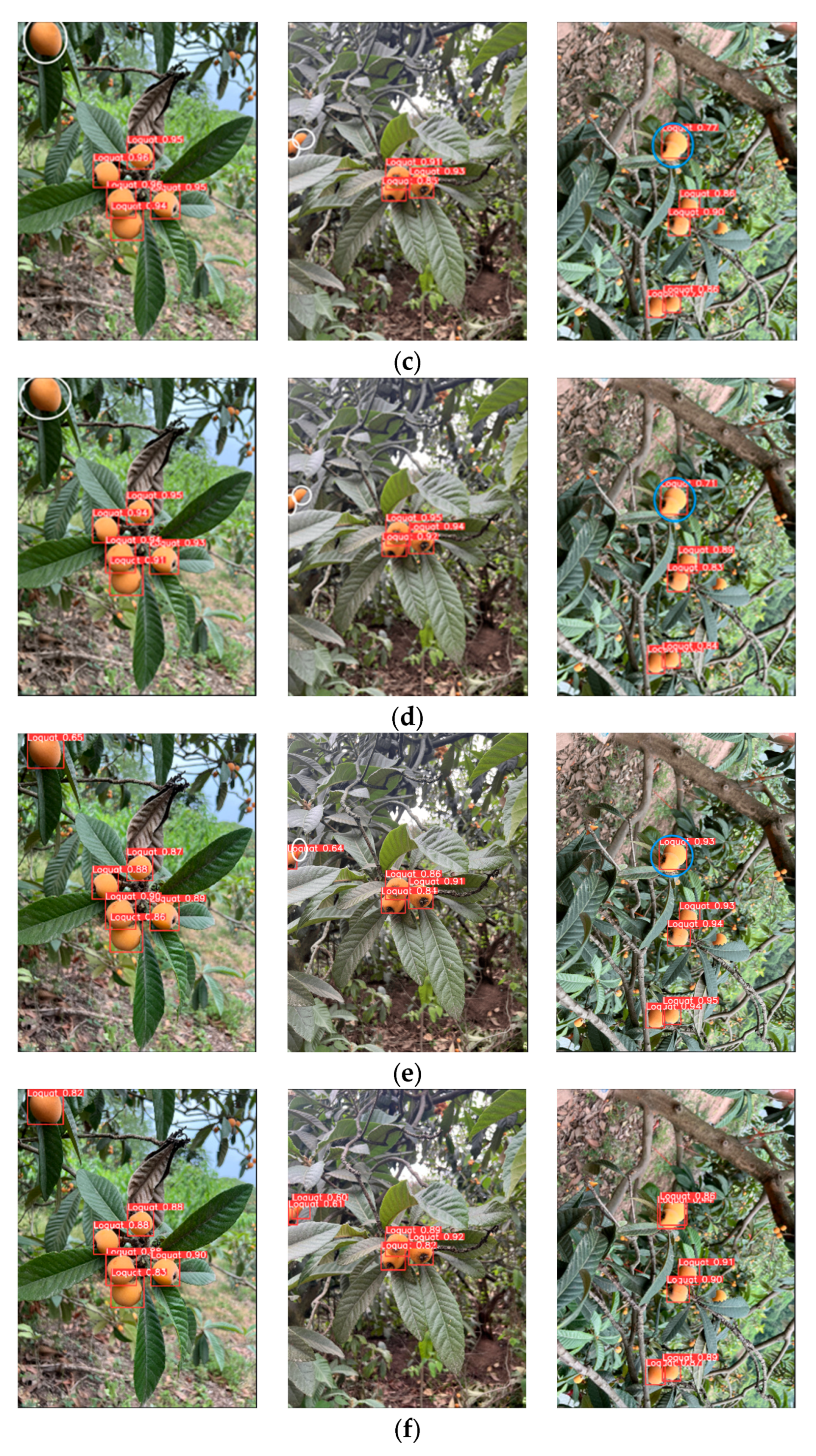

This study evaluates the enhanced EfficientNet-b0 backbone network’s performance for loquat recognition using a dedicated loquat detection dataset. Comparative analysis of various backbone optimization algorithms is presented in

Figure 9. White circles indicate undetected loquat targets, while blue circles indicate cases where the model incorrectly identified multiple connected loquat targets. The mutual obstruction of loquat fruits causes their boundaries to become blurred that makes it easy for the model to misjudge multiple overlapping fruits as a single target during detection. All four backbone network models in

Figure 9 exhibit both undetected and incorrectly detected instances. This indicates that the improved backbone network using EfficientNet-b0 demonstrates better performance in handling occlusions between loquats.

3.5. Ablation Experiment

To assess the true effect of each enhanced module on the model’s overall performance, this research conducted ablation experiments. These experiments used the original YOLOv8n model as a baseline, incorporated the EfficientNet-b0 lightweight network, SimAm attention mechanism, and SCConv convolution module into YOLOv8n, and then performed comparative analyses of the outcomes. As indicated by the experimental results in

Table 6, after improving the original YOLOv8n model with the YOLO-MCS, the precision, recall, and mean average precision have all been improved. This is attributed to the EfficientNet-b0 lightweight network’s robust feature extraction capabilities, which remarkably reduces the model’s parameter count and floating-point computation volume. This demonstrates that the lightweight enhancements to the YOLOv8n model are highly effective, while also improving the precision of loquat recognition. The ablation experiments further reveal that in Experiment 2, substituting the main feature extraction network of YOLOv8 with the lightweight EfficientNet-b0 module resulted in a 11.1% decrease in precision compared to Experiment 1, while recall remained unchanged, mAP decreased by 4.5%. The number of GFLOPs and Params decreased by 2.5 G and 1.1 M, respectively. The core reason behind EfficientNet-b0’s trade-off between computational efficiency and reduced Precision/mAP metrics lies in the balancing act between model complexity and feature extraction capability: EfficientNet-b0 significantly reduces computational load and parameter count through lightweight designs like separable convolutions. However, its limited feature extraction capability struggles to fully capture the diverse characteristics of loquat fruits. This results in insufficient discrimination power for blurry targets and complex backgrounds, leading to increased false positives and false negatives. Ultimately, this manifests as decreased Precision and mAP values. Experiment 5 builds upon Experiment 2 by adding the SimAm to the Neck component. Compared to Experiment 1, precision decreased by 5.0%, recall decreased by 2.6%, the mean average precision decreased by 1.9%, floating-point computations decreased by 2.4 G, and the number of parameters decreased by 1.2 M. However, compared to Experiment 2, precision improved by 6.1%, recall decreased by 2.6%, the mean average precision increased by 2.6%, floating-point operations increased by 0.1 G, and the number of parameters decreased by 0.1 M. It has been proven that the introduction of SimAm has effectively improved the model’s focus on small targets. Experiment 6 improved the C2f module based on Experiment 5, with precision and mAP increasing by 1.3% and 2.2%, respectively, while GFLOPs and parameter count decreased by 2.8 G and 1.3 M, respectively. This further enhanced the lightweight improvements of the YOLOv8n baseline model while also improving detection precision.

In conclusion, the optimized YOLO-MCS model demonstrates notable enhancements in essential performance metrics when compared to the baseline YOLOv8n architecture: precision sees an improvement of 1.3%, and mAP increases by 2.2%. Moreover, the model has experienced a 34.1% reduction in the GFLOPs computations, and its Params count have been cut by 43.3%. This is primarily attributable to: The backbone network adopts the lightweight EfficientNet-b0 architecture. Through its composite model scaling properties, it significantly reduces computational costs while balancing speed and accuracy. The detection head incorporates the SimAm attention mechanism. By employing a feature recalibration strategy, it enhances the model’s ability to focus on loquat targets within complex backgrounds. The SCConv module outputs purer features by reducing spatial and channel redundancy, directly optimizing classification and localization accuracy. Ultimately, these three modules sequentially interact to achieve a significant improvement in overall detection performance under lightweight conditions, fully validating the optimization effectiveness of the proposed YOLO-MCS algorithm.

3.6. Comparison of Different Models

To substantiate the enhanced efficacy of the improved YOLO-MCS model in the recognition of loquat fruit, this study compared the performance of YOLO-MCS with mainstream models such as Faster R-CNN [

36], YOLO-Lite [

37], YOLOv5 [

38], YOLOv6 [

39], YOLOv7 [

40], YOLOv8 [

41], YOLOv9 [

42], YOLOv10 [

43], YOLOv11 [

44] and YOLOv12 [

45]. The comparison experiment was conducted strictly according to the parameter settings shown in

Table 3, with the training iteration counts fixed at 300. To ensure that the evaluation of model performance is not affected by other confounding factors and the experimental data accurately and objectively represent the performance variations among different model architectures, a set of standardized configurations was applied during the experiment. The results comparing the performance of mainstream detection models are detailed in

Table 7. According to the experimental findings in

Table 7, the YOLO-MCS model surpasses other mainstream models in terms of precision and mean average precision, while also requiring fewer parameters and floating-point operations. Specifically, when compared with the Faster R-CNN, YOLO-Lite, YOLOv5, YOLOv6, YOLOv7, YOLOv8, YOLOv9, YOLOv10, YOLOv11 and YOLOv12 algorithms, the precision improved by 23.7%, 2.1%, 3.3%, 5.1%, 1.8%, 1.3%, 9.3%, 4.3%, 9.9% and 8.6%, respectively. Compared with YOLOv5, YOLOv6, YOLOv7, YOLOv8, YOLOv10, YOLOv11, and YOLOv12, the mean Average Precision (mAP) has increased by 3.0%, 4.3%, 2.7%, 2.2%, 7.6%, 3.7%, and 5% respectively. In contrast, when compared with Faster R-CNN, YOLO-Lite, and YOLOv9, its mAP has decreased by 2.5%, 2.8%, and 1.8% respectively. In terms of floating-point computations, reductions of 364.8 G, 10.0 G, 1.8 G, 6.5 G, 99.9 G, 2.8 G, 96.9 G, 53.5 G, 45.4 G and 43.2 G were achieved; in terms of parameter count, reductions of 135.4 M, 2.0 M, 0.8 M, 2.5 M, 26.0 M, 1.3 M, 23.6 M, 13.6 M, 10.8 M, and 10.2 M were achieved. Based on these performance metrics, the YOLO-MCS algorithm demonstrates significantly superior performance compared to other algorithms by providing strong value for deploying loquat detection algorithm models on mobile devices.

3.7. Visual Analytics

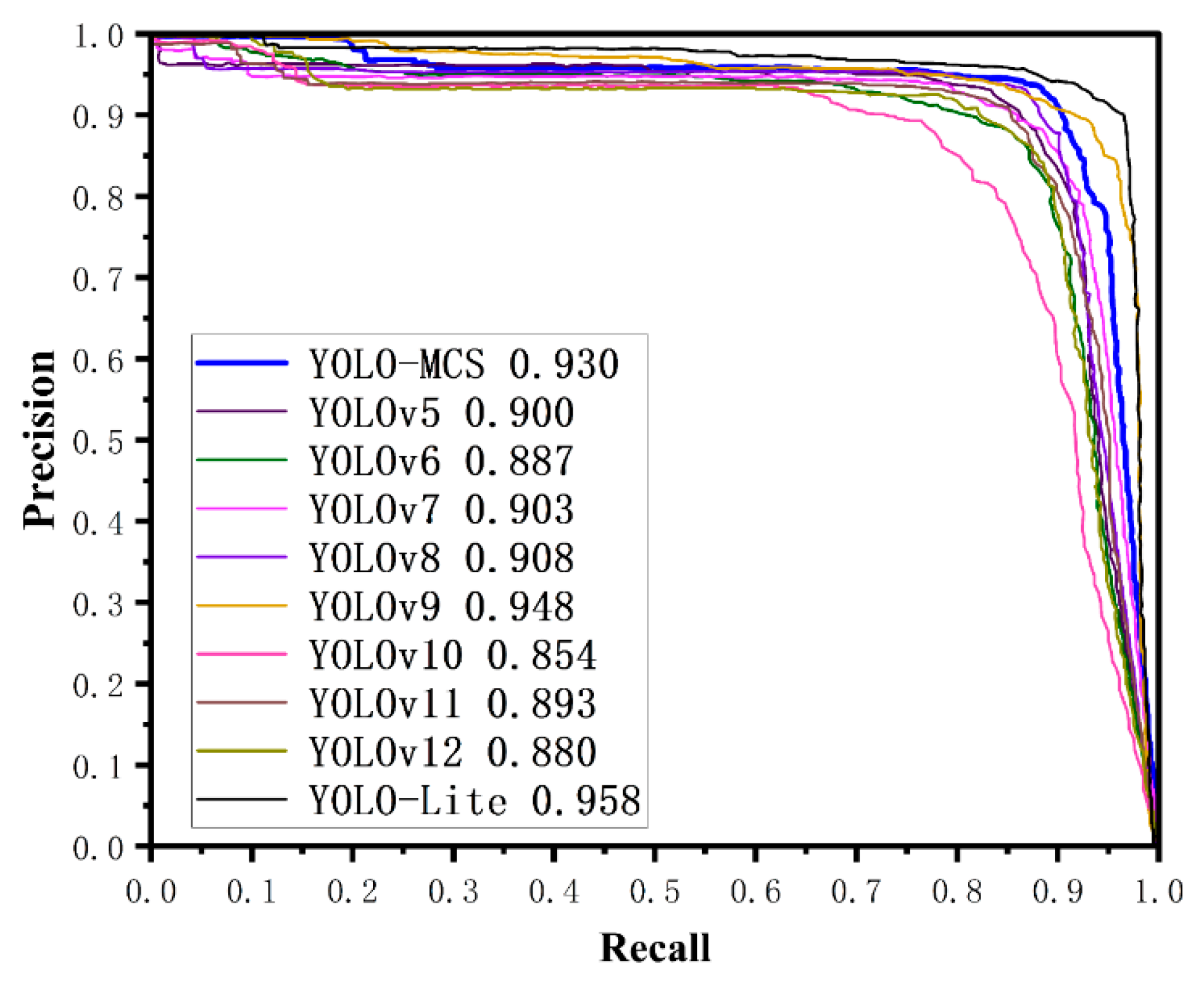

To more intuitively illustrate the effectiveness of the model improvements, a comparison of Precision-Recall (PR) curves was conducted between the improved YOLO-MCS model and other mainstream models. As clearly presented in the PR curve plot (

Figure 10), the YOLO-MCS model proposed in this study exhibits outstanding performance in loquat fruit detection tasks. Specifically, YOLO-MCS-AUC achieves an mAP@0.5 of 0.930, a metric that significantly surpasses that of mainstream baseline models, including YOLOv5 (0.900), YOLOv6 (0.887), YOLOv7 (0.903), and YOLOv8 (0.908). It also outperforms newer model variants such as YOLOv11 (0.893) and YOLOv12 (0.880).

While YOLO-Lite (0.958) and YOLOv9 (0.948) yield marginally higher mAP@0.5 values, YOLO-MCS further enhances model lightweighting without compromising its competitive mAP@0.5 performance. Through dedicated optimization of its network structure, YOLO-MCS strikes a more optimal balance between model lightweighting and detection accuracy. This result fully validates the efficacy of the proposed improvement strategy, confirming that the YOLO-MCS model is particularly well-suited for agricultural computer vision tasks such as loquat fruit recognition.

4. Discussion

In response to the complex background interference and target occlusion issues encountered by loquat harvesting machinery in orchard environments, the study systematically evaluates the recognition performance of the enhanced YOLO-MCS detection model across different meteorological conditions and occlusion scenarios. To fully validate the model’s generalization capability, this study employs cross-validation by partitioning the dataset into training, validation, and independent test sets. All reported performance metrics including precision, recall, and average precision are calculated based on the independent test set, which was not involved in the training process. This ensures the objectivity and universality of the evaluation results.

This study validated the robustness of the YOLO-MCS model through multi-scenario testing, with experimental data collected from loquat fruit images under different lighting conditions, shooting angles, and occlusion levels. Although the structure and parameters of the YOLO-MCS model adopted in this study remain constant, there are significant differences in the precision, recall, and mAP values obtained from evaluations on different loquat datasets. This phenomenon mainly stems from the inherent differences of the datasets themselves. Different datasets vary in acquisition environments (such as lighting conditions and background complexity), target features (such as fruit size, distribution density, and occlusion level), as well as annotation standards and quality. These factors collectively affect the model’s performance: a complex dataset containing more occluded and small-target fruits will introduce a large number of missed detections, leading to a decrease in recall; a dataset with complex backgrounds or interfering objects similar to fruits tends to cause false detections, thereby reducing precision. As a comprehensive indicator, the mAP value directly reflects the model’s adaptability to the challenges presented by a specific test dataset. As can be seen from

Table 8, under three different conditions, the model’s precision rates were 87.3%, 87.0%, and 85.4%, respectively; the recall rates were 81.7%, 89.0%, and 87.8%, respectively; and the mean average precision rates were 88.7%, 89.9%, and 89.9%, respectively. This provides an in-depth explanation of the underlying reasons for the robust performance of the models in

Table 8. Specifically, it highlights that the EfficientNet-b0 backbone achieves balanced composite scaling, constructing rich hierarchical multi-scale features on a lightweight foundation—the fundamental reason the model effectively handles leaf occlusion and lighting variations. The SCConv module significantly enhances the model’s feature discrimination capability for dense clusters through coordinated spatial and channel redundancy reduction. Meanwhile, the SimAm attention mechanism maintains high accuracy in complex backgrounds by precisely focusing on critical fruit regions via parameter-free energy function optimization. The synergistic effects of these improved modules systematically enhance the model’s robustness across feature extraction, redundancy suppression, and target focusing levels. Although there were differences in the data, the model’s overall performance remained excellent.

Figure 11 shows the detection images of loquat fruits under different conditions. This experiment showed that the model had high precision on identifying loquats in complex natural environments.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses the key technical challenges faced in loquat target detection in complex orchard scenarios, such as low computational efficiency, high memory consumption, and insufficient recognition precision. Based on the YOLOv8n network framework, we propose a lightweight improved YOLO-MCS: this model employs a lightweight EfficientNet-b0 module to reconstruct the feature extraction backbone. It further enhances features by introducing the efficient, parameter-free, lightweight SimAm module at the Neck layer and replaces the standard C2f bottleneck structure with SCConv convolutions to reduce feature redundancy, ultimately yielding the improved YOLO-MCS model.

The improved YOLO-MCS lightweight model achieves precision, recall, mean average precision, floating-point computation count, and parameter count of 93.8%, 87.6%, 93.0%, 5.4 G, and 1.7 M, respectively. In comparison to the baseline YOLOv8n model, the YOLO-MCS model introduced in the research greatly enhances model efficiency while preserving outstanding detection capabilities. Notably, precision sees a 1.3% boost, recall rate remains unchanged, and mean average precision improves by 2.2%. Additionally, there is a reduction in GFLOPs and Params by 34.1% and 43.3%, respectively. Compared with other models, the YOLO-MCS model demonstrates the best overall performance in natural scene loquat detection tasks. It ensures accuracy while enabling model lightweighting, thereby striking an efficient balance and offering significant advantages.

The proposed YOLO-MCS model demonstrates effective performance in loquat recognition, though room for improvement remains. The existing dataset only contains images of mature loquats with golden-yellow skin from a single variety, lacking images of unripe (completely green) and semi-ripe (partially green) loquats. Furthermore, it lacks images of loquats from orchard environments in different regions. This limitation may affect the model’s ability to recognize loquats of varying ripeness and different varieties. Therefore, subsequent research will focus on expanding the collection of loquat samples across different maturity stages and images from orchards in diverse geographical regions. This will enhance the model’s versatility and adaptability in detecting loquats at various growth phases. Efforts will also be made to facilitate the practical deployment and performance evaluation of the model on orchard robots or smart terminals, ultimately achieving truly robust real-time detection across different orchards.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z. and L.G.; methodology, W.Z. and L.G.; software, W.Z. and Y.B.; validation, F.S. and Y.B.; formal analysis, L.G. and W.Z.; investigation, Y.B.; resources, L.G. and F.S.; data curation, Y.B.; writing—original draft preparation, W.Z.; writing—review and editing, W.Z. and L.G.; funding acquisition, L.G.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the special topic on innovation and entrepreneurship education in 2024 of CC National Mass Innovation Space of Chengdu University (project number: ccyg202401008) and Chengdu University’s Graduate Education and Teaching Excellence Project (project number: 2025YL001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, S.; Xue, J.; Zhang, T.; Lv, P.; Qin, H.; Zhao, T. Research progress and prospect of key technologies of fruit target recognition for robotic fruit picking. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15, 1423338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Han, Y.; Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, H. Vision based fruit recognition and positioning technology for harvesting robots. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2023, 213, 108258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Sentís, M.; Vélez, S.; Baja, H.; Valenti, R.G.; Valente, J. An aerial framework for Multi-View grape bunch detection and route Optimization using ACO. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, 221, 108972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testolin, R.; Ferguson, A. Kiwifruit (Actinidia spp.) production and marketing in Italy. New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science 2009, 37, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lu, J.; Zhou, M.; Yi, J.; Liao, M.; Gao, Z. A YOLOv3-based computer vision system for identification of tea buds and the picking point. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 198, 107116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, J.; Wang, F.; Yang, J.; Liang, K.; Li, Z. Deep-learning-based accurate identification of warehouse goods for robot picking operations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Gage, J.L.; Rellán-Álvarez, R.; Xiang, L. Swin-Roleaf: A new method for characterizing leaf azimuth angle in large-scale maize plants. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, 224, 109120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Li, H.; Zeng, J.; Han, C.; Chen, T.; Tang, L.; Luo, Y. A review of target recognition technology for fruit picking robots: from digital image processing to deep learning. Applied sciences 2023, 13, 4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, M.; Wang, C.; Luo, L.; Li, J.; Lian, G.; Zou, X. Recognition and localization methods for vision-based fruit picking robots: A review. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulbure, A.-A.; Tulbure, A.-A.; Dulf, E.-H. A review on modern defect detection models using DCNNs–Deep convolutional neural networks. Journal of Advanced Research 2022, 35, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J.; Zhang, S.; Sun, H.; Ren, R.; Cui, T. YOLO-PEM: A lightweight detection method for young “Okubo” peaches in complex orchard environments. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Chen, J.; Fu, L.; Zhong, J.; Qiaoi, W.; Luo, J.; Li, J.; Li, N. Real-time citrus variety detection in orchards based on complex scenarios of improved YOLOv7. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15, 1381694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.; Tang, G.; Chen, W.; Hu, S.; Li, Y.; Gong, H. MobileNet-YOLO v5s: An improved lightweight method for real-time detection of sugarcane stem nodes in complex natural environments. Ieee Access 2023, 11, 104070–104083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Lv, Q.; Bian, Y.; He, R.; Lv, D.; Gao, L.; Wu, H.; Li, X. Grape Target Detection Method in Orchard Environment Based on Improved YOLOv7. Agronomy 2025, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, B.; Xue, J. YOLO-P: An efficient method for pear fast detection in complex orchard picking environment. Frontiers in plant science 2023, 13, 1089454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Abeyrathna, R.R.D.; Sampurno, R.M.; Nakaguchi, V.M.; Ahamed, T. Faster-YOLO-AP: A lightweight apple detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv8 with a new efficient PDWConv in orchard. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, 223, 109118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Nyalala, I.; Chen, K. Detecting the early flowering stage of tea chrysanthemum using the F-YOLO model. Agronomy 2021, 11, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Duan, Z.; Ning, H.; Zhang, Y. PBA-YOLOv7: an object detection method based on an improved YOLOv7 network. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 10436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018; pp. 8759–8768.

- Huang, M.; Mi, W.; Wang, Y. Edgs-yolov8: An improved yolov8 lightweight uav detection model. Drones 2024, 8, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Hua, Z.; Wen, Y.; Deng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Pu, L.; Song, H. Using an improved lightweight YOLOv8 model for real-time detection of multi-stage apple fruit in complex orchard environments. Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture 2024, 11, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Qing, S.; Zhao, L.; Wang, F.; Yuwen, X.; Qu, M. Yolo-peach: a high-performance lightweight yolov8s-based model for accurate recognition and enumeration of peach seedling fruits. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atila, Ü.; Uçar, M.; Akyol, K.; Uçar, E. Plant leaf disease classification using EfficientNet deep learning model. Ecological Informatics 2021, 61, 101182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.-C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018; pp. 4510–4520.

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018; pp. 7132–7141.

- Li, J.; Wen, Y.; He, L. Scconv: Spatial and channel reconstruction convolution for feature redundancy. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023; pp. 6153–6162.

- Yang, L.; Zhang, R.-Y.; Li, L.; Xie, X. Simam: A simple, parameter-free attention module for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning; 2021; pp. 11863–11874. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D.; Zhang, K.; Zhong, H.; Xie, J.; Xue, X.; Yan, M.; Wu, W.; Li, J. Efficient tobacco pest detection in complex environments using an enhanced YOLOv8 model. Agriculture 2024, 14, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Sun, F.; Bian, Y.; Wu, H.; Li, X.; Zhou, J. A Lightweight Citrus Object Detection Method in Complex Environments. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Wang, J.; Zhao, W.; Guo, H.; Dai, D.; Yun, Y.; Li, L.; Hao, F.; Bai, J.; Ma, D. Identification of maize seed varieties using MobileNetV2 with improved attention mechanism CBAM. Agriculture 2022, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020; pp. 11534–11542.

- Liu, Y.; Shao, Z.; Hoffmann, N. Global attention mechanism: Retain information to enhance channel-spatial interactions. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2112.05561 2021.

- Wang, Y.; Deng, H.; Wang, Y.; Song, L.; Ma, B.; Song, H. CenterNet-LW-SE net: integrating lightweight CenterNet and channel attention mechanism for the detection of Camellia oleifera fruits. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, 83, 68585–68603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.W.; Po, L.-M.; Rehman, Y.A.U. Large separable kernel attention: Rethinking the large kernel attention design in cnn. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 236, 121352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.-C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V. Searching for mobilenetv3. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019; pp. 1314–1324.

- Li, J.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, H.; Su, Y.; Deng, L. Strawberry R-CNN: Recognition and counting model of strawberry based on improved faster R-CNN. Ecological Informatics 2023, 77, 102210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Pedoeem, J.; Chen, C. YOLO-LITE: a real-time object detection algorithm optimized for non-GPU computers. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE international conference on big data (big data); 2018; pp. 2503–2510. [Google Scholar]

- Malta, A.; Mendes, M.; Farinha, T. Augmented reality maintenance assistant using yolov5. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norkobil Saydirasulovich, S.; Abdusalomov, A.; Jamil, M.K.; Nasimov, R.; Kozhamzharova, D.; Cho, Y.-I. A YOLOv6-based improved fire detection approach for smart city environments. Sensors 2023, 23, 3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, E.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, R. Detection of Camellia oleifera fruit in complex scenes by using YOLOv7 and data augmentation. Applied sciences 2022, 12, 11318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Su, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, Z.; Yan, H. Wheat seed detection and counting method based on improved YOLOv8 model. Sensors 2024, 24, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Rong, Q.; Hu, C. Ripe tomato detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv9. Plants 2024, 13, 3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Wang, C.; Ji, T.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, T. D3-YOLOv10: Improved YOLOv10-based lightweight tomato detection algorithm under facility scenario. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Chen, T.; Liu, Q. Advancing Rice Disease Detection in Farmland with an Enhanced YOLOv11 Algorithm. Sensors 2025, 25, 3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Zhao, Z.; Weng, L. MAS-YOLO: A Lightweight Detection Algorithm for PCB Defect Detection Based on Improved YOLOv12. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Loquat dataset collected under different conditions: (a) Isolated fruit; (b) Cluster of fruits; (c) Sunny day; (d) Cloudy day; (e) Front lighting; (f) Back lighting; (g) Obstruction; (h) Ultra-long distance.

Figure 1.

Loquat dataset collected under different conditions: (a) Isolated fruit; (b) Cluster of fruits; (c) Sunny day; (d) Cloudy day; (e) Front lighting; (f) Back lighting; (g) Obstruction; (h) Ultra-long distance.

Figure 2.

Image enhancement of loquat fruit: (a) Raw images; (b) Flip; (c) Random rotation; (d) Random noise; (e) Sharpen; (f) Different brightness.

Figure 2.

Image enhancement of loquat fruit: (a) Raw images; (b) Flip; (c) Random rotation; (d) Random noise; (e) Sharpen; (f) Different brightness.

Figure 3.

YOLOv8n network structure diagram.

Figure 3.

YOLOv8n network structure diagram.

Figure 4.

YOLO-MCS network structure diagram.

Figure 4.

YOLO-MCS network structure diagram.

Figure 5.

MBConv module structure.

Figure 5.

MBConv module structure.

Figure 6.

Comparative diagram of bottleneck architectures with and without C2f enhancement: (a) Baseline bottleneck; (b) Improved bottleneck.

Figure 6.

Comparative diagram of bottleneck architectures with and without C2f enhancement: (a) Baseline bottleneck; (b) Improved bottleneck.

Figure 7.

SCConv module structure diagram.

Figure 7.

SCConv module structure diagram.

Figure 8.

SimAm attention mechanism structure diagram.

Figure 8.

SimAm attention mechanism structure diagram.

Figure 9.

Detection results for different network backbones: (a) Raw images; (b) YOLOv8n; (c) Mo bileNetv3; (d) ShuffleNetv2; (e) GhostNetv2; (f) EfficientNet-b0.

Figure 9.

Detection results for different network backbones: (a) Raw images; (b) YOLOv8n; (c) Mo bileNetv3; (d) ShuffleNetv2; (e) GhostNetv2; (f) EfficientNet-b0.

Figure 10.

Precision-Recall Curve.

Figure 10.

Precision-Recall Curve.

Figure 11.

Test results under different conditions: (a-c) Different lighting conditions; (d-f) Different perspectives; (g-i) Different obstruction.

Figure 11.

Test results under different conditions: (a-c) Different lighting conditions; (d-f) Different perspectives; (g-i) Different obstruction.

Table 1.

Dataset Division.

Table 1.

Dataset Division.

| Category |

Original Image |

Image Enhancement |

Training Set |

Validation Set |

Test Set |

| Number |

325 |

1625 |

1560 |

195 |

195 |

Table 2.

EfficientNet-b0 lightweight module structure table.

Table 2.

EfficientNet-b0 lightweight module structure table.

| |

Type |

Resolution |

Channels |

Layers |

| 1 |

Conv3×3 |

224 × 224 |

32 |

1 |

| 2 |

MBConv1,k3×3 |

112 × 112 |

16 |

1 |

| 3 |

MBConv6,k3×3 |

112 ×112 |

24 |

2 |

| 4 |

MBConv6,k5×5 |

56 × 56 |

40 |

2 |

| 5 |

MBConv6,k5×5 |

28 × 28 |

80 |

3 |

| 6 |

MBConv6,k5×5 |

14 × 14 |

112 |

3 |

| 7 |

MBConv6,k5×5 |

14 × 14 |

192 |

4 |

| 8 |

MBConv6,k3×3 |

7 × 7 |

320 |

1 |

| 9 |

Conv1×1&Pooling&FC |

7 × 7 |

1280 |

1 |

Table 3.

Experimental parameters.

Table 3.

Experimental parameters.

| Training Parameters |

Numerical Value |

| Image size |

300 |

| Batch size |

640×640 |

| Initial learning rate |

0.01 |

| Optimizer |

SGD |

| Momentum |

0.937 |

| Multi-threaded |

16 |

Table 4.

Model detection results with different attention mechanisms introduced.

Table 4.

Model detection results with different attention mechanisms introduced.

| Models |

Precision

(%) |

Recall

(%) |

mAP@0.5

(%) |

GFLOPs

(G) |

Params

(M) |

| YOLOv8n |

92.5 |

87.6 |

90.8 |

8.2 |

3.0 |

| CBAM |

86.8 |

84.2 |

88.0 |

5.5 |

1.7 |

| SE |

89.8 |

86.3 |

86.9 |

5.4 |

1.7 |

| ECA |

85.8 |

84.3 |

89.0 |

5.4 |

1.7 |

| GAM |

86.8 |

87.2 |

88.5 |

6.5 |

2.2 |

| LSKA |

88.7 |

80.6 |

88.2 |

5.6 |

1.7 |

| SimAm |

93.8 |

87.6 |

93.0 |

5.4 |

1.7 |

Table 5.

Comparison of different main stems.

Table 5.

Comparison of different main stems.

Backbone

network |

Precision

(%) |

Recall

(%) |

mAP@0.5

(%) |

GFLOPs

(G) |

Params

(M) |

| YOLOv8n |

92.5 |

87.6 |

90.8 |

8.2 |

3.0 |

| MobileNetv3 |

90.3 |

77.3 |

87.4 |

5.8 |

2.4 |

| ShuffleNetv2 |

83.4 |

84.8 |

89.6 |

4.7 |

1.5 |

| GhostNetv2 |

82.1 |

84.6 |

87.3 |

7.7 |

3.5 |

| EfficientNet-b0 |

93.8 |

87.6 |

93.0 |

5.4 |

1.7 |

Table 6.

Ablation experiment.

Table 6.

Ablation experiment.

| |

Efficient

Net-b0 |

Sim

Am |

SC

Conv |

P(%) |

R(%) |

mAP@0.5

(%) |

GFLOPs

(G) |

Params

(M) |

| 1 |

- |

- |

- |

92.5 |

87.6 |

90.8 |

8.2 |

3.0 |

| 2 |

√ |

- |

- |

81.4 |

87.6 |

86.3 |

5.7 |

1.9 |

| 3 |

- |

√ |

- |

91.3 |

87.6 |

91.1 |

8.3 |

2.9 |

| 4 |

- |

- |

√ |

88.8 |

91.2 |

92.3 |

7.8 |

2.8 |

| 5 |

√ |

√ |

- |

87.5 |

85.0 |

88.9 |

5.8 |

1.8 |

| 6 |

√ |

√ |

√ |

93.8 |

87.6 |

93.0 |

5.4 |

1.7 |

Table 7.

Comparison with other YOLO models.

Table 7.

Comparison with other YOLO models.

| Models |

Precision(%) |

Recall(%) |

mAP@0.5(%) |

GFLOPs(G) |

Params(M) |

| Faster R-CNN |

70.1 |

98.0 |

95.5 |

370.2 |

137.1 |

| YOLO-Lite |

91.7 |

94.0 |

95.8 |

15.4 |

3.7 |

| YOLOv5 |

90.5 |

85.4 |

90.0 |

7.2 |

2.5 |

| YOLOv6 |

88.7 |

84.7 |

88.7 |

11.9 |

4.2 |

| YOLOv7 |

92.0 |

82.2 |

90.3 |

105.3 |

27.7 |

| YOLOv8 |

92.5 |

87.6 |

90.8 |

8.2 |

3.0 |

| YOLOv9 |

84.5 |

95.2 |

94.8 |

102.3 |

25.3 |

| YOLOv10 |

89.5 |

73.0 |

85.4 |

58.9 |

15.3 |

| YOLOv11 |

83.9 |

88.6 |

89.3 |

50.8 |

12.5 |

| YOLOv12 |

85.2 |

87.4 |

88.0 |

48.6 |

11.9 |

| YOLO-MCS |

93.8 |

87.6 |

93.0 |

5.4 |

1.7 |

Table 8.

Test results under different conditions.

Table 8.

Test results under different conditions.

| Model |

Conditions |

P(%) |

R(%) |

mAP@0.5(%) |

| YOLO-MCS |

Different light conditions |

87.3 |

81.7 |

88.7 |

| Different perspectives |

87.0 |

89.0 |

89.9 |

| Different obstruction |

85.4 |

87.8 |

89.9 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).