Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Chemical Characterization of the EOs

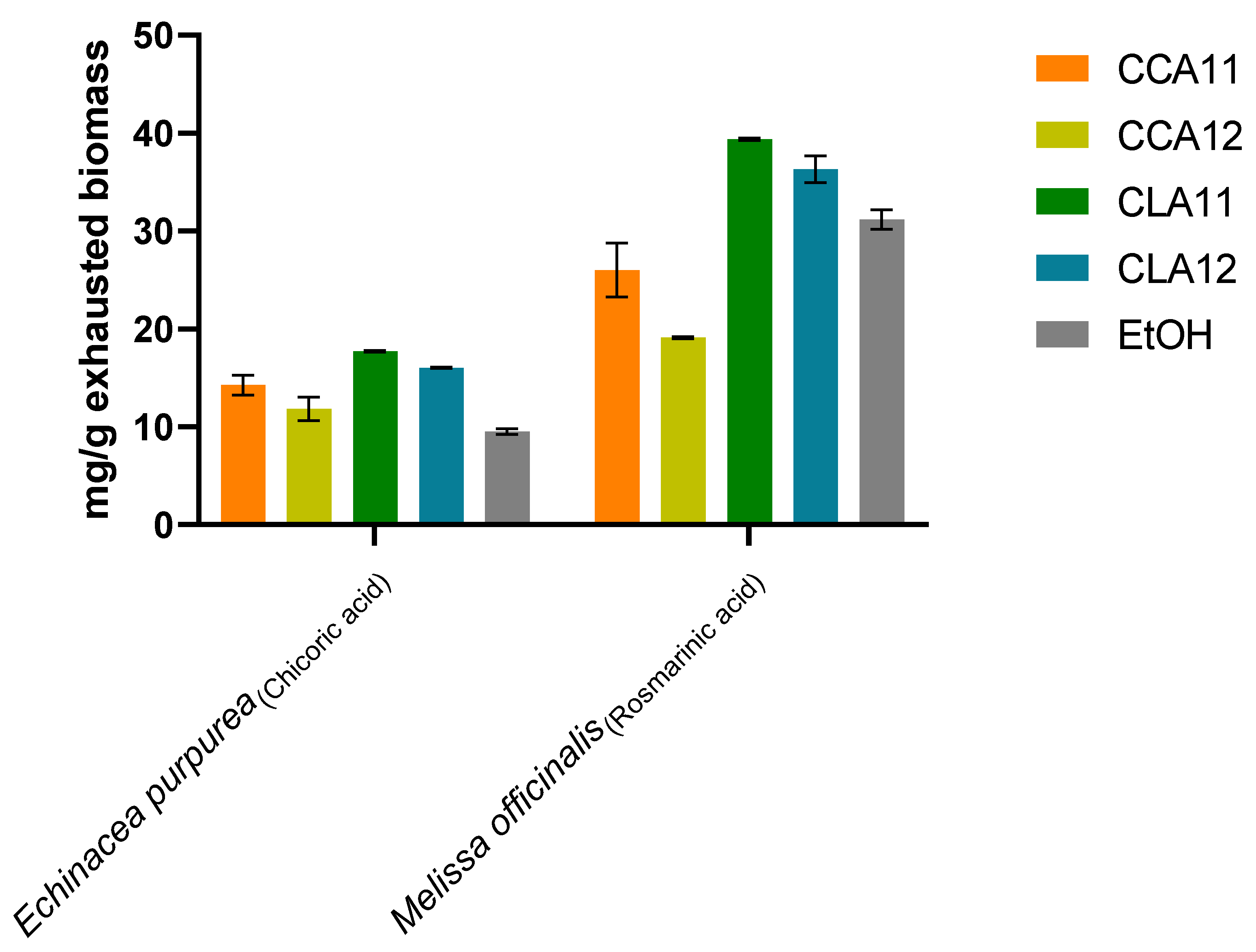

2.2. Optimization of NADES Extraction

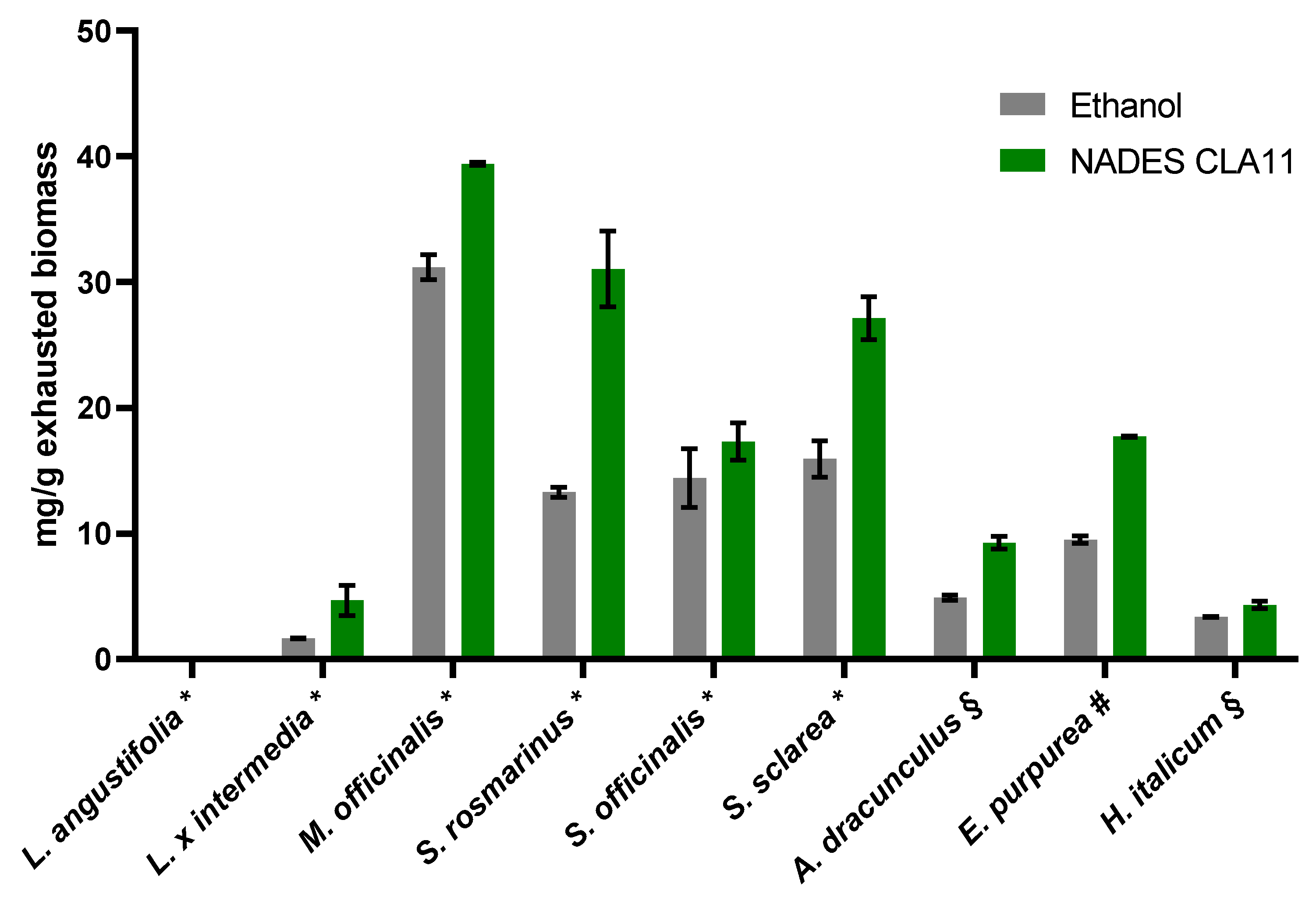

2.3. Analysis of Optimized NADES and EtOH Extracts

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Sample Materials

3.2. Steam Distillation

3.3. Chemical Characterization of the EOs

3.3.1. GC-MS Analysis

3.3.2. GC-FID Analysis

3.4. Preparation of NADES Mixtures

3.5. Oil-Exhausted Biomass Extraction

3.5.1. Ethanolic Extraction

3.5.2. NADES Extraction

3.6. Characterization of Biomass Extracts

3.6.1. UHPLC-HRMS Analysis

3.6.2. HPLC-DAD Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EO | Essential oil |

| NADES | Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents |

| HBA | Hydrogen bond acceptor |

| HBD | Hydrogen bond donator |

| ART | Artemisia dracunculus |

| ECHI | Echinacea purpurea |

| HEL | Helichrysum italicum |

| LAV | Lavandula angustifolia |

| LAI | Lavandula x intermedia |

| MEL | Melissa officinalis |

| SAO | Salvia officinalis |

| ROS | Salvia rosmarinus |

| SAS | Salvia sclarea |

| GC | Gas chromatography |

| UHPLC-HRMS | Ultrahigh-Performance Liquid Chromatography–High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry |

| HPLC-DAD | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detection |

| LRI | Linear retention index |

| EtOH | Ethanol |

| Hex | hexane |

| ChCl | Choline chloride |

References

- Fierascu, R.C.; Fierascu, I.; Baroi, A.M.; Ortan, A. Selected Aspects Related to Medicinal and Aromatic Plants as Alternative Sources of Bioactive Compounds. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhy, M.; Abdelkarim, E.A.; Hussein, M.A.; Aziz, T.; Al-Asmari, F.; Alabbosh, K.F.; Cui, H.; Lin, L. Essential Oils as Antibacterials against Multidrug-Resistant Foodborne Pathogens: Mechanisms, Recent Advances, and Legal Considerations. Food Biosci 2025, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, F.; Rossi, C.; Serio, A.; Chaves-Lopez, C.; Casaccia, M.; Paparella, A. Anti-Biofilm Mechanisms of Action of Essential Oils by Targeting Genes Involved in Quorum Sensing, Motility, Adhesion, and Virulence: A Review. Int J Food Microbiol 2025, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavda, V.; Balar, P.; Apostolopoulos, V. A Review on Essential Oils: A Potential Tonic for Mental Wellbeing in the Aging Population? Maturitas 2025, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavda, V.; Balar, P.; Apostolopoulos, V. A Review on Essential Oils: A Potential Tonic for Mental Wellbeing in the Aging Population? Maturitas 2025, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmi, A.; Correa, F.; Ventrella, D.; Scozzoli, M.; Vannetti, N.I.; Govoni, N.; Truzzi, E.; Belperio, S.; Trevisi, P.; Bacci, M.L.; et al. Can Environmental Nebulization of Lavender Essential Oil (L. Angustifolia) Improve Welfare and Modulate Nasal Microbiota of Growing Pigs? Res Vet Sci 2024, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanović, N.M.; Ranđelović, P.J.; Simonović, M.; Radić, M.; Todorović, S.; Corrigan, M.; Harkin, A.; Boylan, F. Essential Oil Constituents as Anti-Inflammatory and Neuroprotective Agents: An Insight through Microglia Modulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 2024, 5168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, D.P.; Damasceno, R.O.S.; Amorati, R.; Elshabrawy, H.A.; de Castro, R.D.; Bezerra, D.P.; Nunes, V.R. V.; Gomes, R.C.; Lima, T.C. Essential Oils: Chemistry and Pharmacological Activities. Biomolecules 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Nascimento, L.D.; de Moraes, A.A.B.; da Costa, K.S.; Galúcio, J.M.P.; Taube, P.S.; Costa, C.M.L.; Cruz, J.N.; de Andrade, E.H.; de Faria, L.J.G. Bioactive Natural Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Essential Oils from Spice Plants: New Findings and Potential Applications. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, S.; Tambe, S.; Deshmukh, R.K.; Mali, S.; Cruz, J.; Srivastav, P.P.; Amin, P.D.; Gaikwad, K.K.; de Andrade, E.H.; de Oliveira, M.S. Recent Trends in the Application of Essential Oils: The next Generation of Food Preservation and Food Packaging. Trends Food Sci Technol 2022, 129, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truzzi, E.; Benvenuti, S.; Bertelli, D.; Francia, E.; Ronga, D. Effects of Biostimulants on the Chemical Composition of Essential Oil and Hydrosol of Lavandin (Lavandula x Intermedia Emeric Ex Loisel.) Cultivated in Tuscan-Emilian Apennines. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truzzi, E.; Chaouch, M.A.; Rossi, G.; Tagliazucchi, L.; Bertelli, D.; Benvenuti, S. Characterization and Valorization of the Agricultural Waste Obtained from Lavandula Steam Distillation for Its Reuse in the Food and Pharmaceutical Fields. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, T.; Esposito, F.; Cirillo, T. Valorization of Agro-Food by-Products: Advancing Sustainability and Sustainable Development Goals 2030 through Functional Compounds Recovery. Food Biosci 2024, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Luo, J.; Sheng, Z.; Fang, Z.; Fu, Y.; Wang, N.; Yang, B.; Xu, B. Latest Research Progress on Anti-Microbial Effects, Mechanisms of Action, and Product Developments of Dietary Flavonoids: A Systematic Literature Review. Trends Food Sci Technol 2025, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.C.; Souza, V.P.; Padilha, A.P.F.; Duarte, F.A.; Flores, E.M. Trends and Perspectives on the Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Compounds Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Curr Opin Chem Eng 2025, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Varypataki, E.M.; Golovina, E.A.; Jiskoot, W.; Witkamp, G.J.; Choi, Y.H.; Verpoorte, R. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents in Plants and Plant Cells: In Vitro Evidence for Their Possible Functions. Adv Bot Res 2021, 97, 159–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koraqi, H.; Yüksel Aydar, A.; Pandiselvam, R.; Qazimi, B.; Khalid, W.; Trajkovska Petkoska, A.; Çesko, C.; Ramniwas, S.; Mohammed Basheeruddin Asdaq, S.; Rustagi, S. Optimization of Extraction Condition to Improve Blackthorn (Prunus Spinosa L.) Polyphenols, Anthocyanins and Antioxidant Activity by Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent (NADES) Using the Simplex Lattice Mixture Design Method. Microchemical Journal 2024, 200, 110497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milošević, S.; Bebek Markovinović, A.; Teslić, N.; Mišan, A.; Pojić, M.; Brčić Karačonji, I.; Jurica, K.; Lasić, D.; Putnik, P.; Bursać Kovačević, D.; et al. Use of Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent (NADES) as a Green Extraction of Antioxidant Polyphenols from Strawberry Tree Fruit (Arbutus Unedo L.): An Optimization Study. Microchemical Journal 2024, 200, 110284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uka, D.; Kukrić, T.; Krstonošić, V.; Jović, B.; Kordić, B.; Pavlović, K.; Popović, B.M. NADES Systems Comprising Choline Chloride and Polyphenols: Physicochemical Characterization, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities. J Mol Liq 2024, 410, 125683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir-Cerdà, A.; Granados, M.; Saurina, J.; Sentellas, S. Olive Tree Leaves as a Great Source of Phenolic Compounds: Comprehensive Profiling of NaDES Extracts. Food Chem 2024, 456, 140042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, S.; Romano, A. In Vitro Culture of Lavenders (Lavandula Spp.) and the Production of Secondary Metabolites. Biotechnol Adv 2013, 31, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittler, J.; Krüger, H.; Ulrich, D.; Zeiger, B.; Schütze, W.; Böttcher, C.; Krähmer, A.; Gudi, G.; Kästner, U.; Heuberger, H.; et al. Content and Composition of Essential Oil and Content of Rosmarinic Acid in Lemon Balm and Balm Genotypes (Melissa Officinalis). Genet Resour Crop Evol 2018, 65, 1517–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; Ali, A.; Abdullah, H.M.; Balaji, J.; Kaur, J.; Saeed, F.; Wasiq, M.; Imran, A.; Jibraeel, H.; Raheem, M.S.; et al. Nutritional Composition, Phytochemical Profile, Therapeutic Potentials, and Food Applications of Rosemary: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2024, 135, 106688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truzzi, E.; Durante, C.; Bertelli, D.; Catellani, B.; Pellacani, S.; Benvenuti, S. Rapid Classification and Recognition Method of the Species and Chemotypes of Essential Oils by ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy Coupled with Chemometrics. Molecules 2022, 27, 5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Akacha, B.; Ben Hsouna, A.; Generalić Mekinić, I.; Ben Belgacem, A.; Ben Saad, R.; Mnif, W.; Kačániová, M.; Garzoli, S. Salvia Officinalis L. and Salvia Sclarea Essential Oils: Chemical Composition, Biological Activities and Preservative Effects against Listeria Monocytogenes Inoculated into Minced Beef Meat. Plants 2023, 12, 3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordali, S.; Kotan, R.; Mavi, A.; Cakir, A.; Ala, A.; Yildirim, A. Determination of the Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of the Essential Oil of Artemisia Dracunculus and of the Antifungal and Antibacterial Activities of Turkish Artemisia Absinthium, A. Dracunculus, Artemisia Santonicum, and Artemisia Spicigera Essential Oils. J Agric Food Chem 2005, 53, 9452–9458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosoky, N.S.; Kirpotina, L.N.; Schepetkin, I.A.; Khlebnikov, A.I.; Lisonbee, B.L.; Black, J.L.; Woolf, H.; Thurgood, T.L.; Graf, B.L.; Satyal, P.; et al. Volatile Composition, Antimicrobial Activity, and In Vitro Innate Immunomodulatory Activity of Echinacea Purpurea (L.) Moench Essential Oils. Molecules 2023, 28, 7330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, M.; Giovanelli, S.; Ambryszewska, K.E.; Ruffoni, B.; Cervelli, C.; Pistelli, L.; Flamini, G.; Pistelli, L. Essential Oil Composition of Six Helichrysum Species Grown in Italy. Biochem Syst Ecol 2018, 79, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.nist.gov/.

- Soukaina, K.; Safa, Z.; Soukaina, H.; Hicham, C.; Bouchra, C. Choline Chloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES): Potential Use as Green Extraction Media for Polyphenols from Mentha Pulegium, Antioxidant Activity, and Antifungal Activity. Microchemical Journal 2024, 199, 110174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- No L Official Journal of the European Communities 14.12.70 Articles 43.

- Bakirtzi, C.; Triantafyllidou, K.; Makris, D.P. Novel Lactic Acid-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents: Efficiency in the Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Antioxidant Polyphenols from Common Native Greek Medicinal Plants. J Appl Res Med Aromat Plants 2016, 3, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Ping-Kou; Jiang, Y.W.; Wang, L.T.; Niu, L.J.; Liu, Z.M.; Fu, Y.J. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents Couple with Integrative Extraction Technique as an Effective Approach for Mulberry Anthocyanin Extraction. Food Chem 2019, 296, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, D.T. da; Pauletto, R.; Cavalheiro, S.d.S.; Bochi, V.C.; Rodrigues, E.; Weber, J.; Silva, C.d.B.d.; Morisso, F.D.P.; Barcia, M.T.; Emanuelli, T. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents as a Biocompatible Tool for the Extraction of Blueberry Anthocyanins. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2020, 89, 103470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač, M.J.; Pavić, V.; Huđ, A.; Cindrić, I.; Molnar, M. Determination of Suitable Macroporous Resins and Desorbents for Carnosol and Carnosic Acid from Deep Eutectic Solvent Sage (Salvia Officinalis) Extract with Assessment of Antiradical and Antibacterial Activity. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgantzi, C.; Lioliou, A.-E.; Paterakis, N.; Makris, D. Combination of Lactic Acid-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) with β-Cyclodextrin: Performance Screening Using Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Polyphenols from Selected Native Greek Medicinal Plants. Agronomy 2017, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannou, O.; Pashazadeh, H.; Galanakis, C.M.; Alamri, A.S.; Koca, I. Carboxylic Acid-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents Combined with Innovative Extraction Techniques for Greener Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Sumac (Rhus Coriaria L.). J Appl Res Med Aromat Plants 2022, 30, 100380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvjetko Bubalo, M.; Ćurko, N.; Tomašević, M.; Kovačević Ganić, K.; Radojcic Redovnikovic, I. Green Extraction of Grape Skin Phenolics by Using Deep Eutectic Solvents. Food Chem 2016, 200, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stini, E.; Tsimogiannis, D.; Oreopoulou, V. The Valorisation of Melissa Officinalis Distillation By-Products for the Production of Polyphenol-Rich Formulations. Molecules 2024, 29, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajkacz, S.; Adamek, J. Development of a Method Based on Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents for Extraction of Flavonoids from Food Samples. Food Anal Methods 2018, 11, 1330–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukaina, K.; Safa, Z.; Soukaina, H.; Hicham, C.; Bouchra, C. Choline Chloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES): Potential Use as Green Extraction Media for Polyphenols from Mentha Pulegium, Antioxidant Activity, and Antifungal Activity. Microchemical Journal 2024, 199, 110174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siamandoura, P.; Tzia, C. Comparative Study of Novel Methods for Olive Leaf Phenolic Compound Extraction Using NADES as Solvents. Molecules 2023, 28, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puma-Isuiza, G.; García-Chacón, J.M.; Osorio, C.; Betalleluz-Pallardel, I.; Chue, J.; Inga, M. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Lucuma (Pouteria Lucuma) Seeds with Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents: Modelling Using Response Surface Methodology and Artificial Neural Networks. Front Sustain Food Syst 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Mar Contreras, M.; Algieri, F.; Rodriguez-Nogales, A.; Gálvez, J.; Segura-Carretero, A. Phytochemical Profiling of Anti-Inflammatory Lavandula Extracts via RP–HPLC–DAD–QTOF–MS and –MS/MS: Assessment of Their Qualitative and Quantitative Differences. Electrophoresis 2018, 39, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramberger, K.; Barlič-Maganja, D.; Bandelj, D.; Baruca Arbeiter, A.; Peeters, K.; Miklavčič Višnjevec, A.; Jenko Pražnikar, Z. HPLC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS Determination of Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity Comparison of the Hydroalcoholic and Water Extracts from Two Helichrysum Italicum Species. Metabolites 2020, 10, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Scagel, C.F. Chicoric Acid Found in Basil (Ocimum Basilicum L.) Leaves. Food Chem 2009, 115, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Jáuregui, O.; Di Lecce, G.; Andrés-Lacueva, C.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Screening of the Polyphenol Content of Tomato-Based Products through Accurate-Mass Spectrometry (HPLC–ESI-QTOF). Food Chem 2011, 129, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, J.; Yan, J.; Zheng, D.; Sun, F.; Wang, J.; Han, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T. Comprehensive Chemical Profiling in the Ethanol Extract of Pluchea Indica Aerial Parts by Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Its Silica Gel Column Chromatography Fractions. Molecules 2019, 24, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truzzi, E.; Chaouch, M.A.; Rossi, G.; Tagliazucchi, L.; Bertelli, D.; Benvenuti, S. Characterization and Valorization of the Agricultural Waste Obtained from Lavandula Steam Distillation for Its Reuse in the Food and Pharmaceutical Fields. Molecules 2022, 27, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souhila, T.; Fatma Zohra, B.; Tahar, H.S. Identification and Quantification of Phenolic Compounds of Artemisia Herba-Alba at Three Harvest Time by HPLC–ESI–Q-TOF–MS. Int J Food Prop 2019, 22, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolella, S.; Crescente, G.; Volpe, M.G.; Paolucci, M.; Pacifico, S. UHPLC-HR-MS/MS-Guided Recovery of Bioactive Flavonol Compounds from Greco Di Tufo Vine Leaves. Molecules 2019, 24, 3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravina, C.; Formato, M.; Piccolella, S.; Fiorentino, M.; Stinca, A.; Pacifico, S.; Esposito, A. Lavandula Austroapennina (Lamiaceae): Getting Insights into Bioactive Polyphenols of a Rare Italian Endemic Vascular Plant. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 8038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrare, K.; Bidel, L.P.R.; Awwad, A.; Poucheret, P.; Cazals, G.; Lazennec, F.; Azay-Milhau, J.; Tournier, M.; Lajoix, A.D.; Tousch, D. Increase in Insulin Sensitivity by the Association of Chicoric Acid and Chlorogenic Acid Contained in a Natural Chicoric Acid Extract (NCRAE) of Chicory (Cichorium Intybus L.) for an Antidiabetic Effect. J Ethnopharmacol 2018, 215, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Mar Contreras, M.; Algieri, F.; Rodriguez-Nogales, A.; Gálvez, J.; Segura-Carretero, A. Phytochemical Profiling of Anti-Inflammatory Lavandula Extracts via RP–HPLC–DAD–QTOF–MS and –MS/MS: Assessment of Their Qualitative and Quantitative Differences. Electrophoresis 2018, 39, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Han, F.; He, J.; Duan, C. HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS Analysis and Antioxidant Activities of Nonanthocyanin Phenolics in Mulberry (Morus Alba L.). J Food Sci 2008, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, B.F.; Walch, S.G.; Tinzoh, L.N.; Stühlinger, W.; Lachenmeier, D.W. Rapid UHPLC Determination of Polyphenols in Aqueous Infusions of Salvia Officinalis L. (Sage Tea). Journal of Chromatography B 2011, 879, 2459–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.L.; Pereira, E.; Soković, M.; Carvalho, A.M.; Barata, A.M.; Lopes, V.; Rocha, F.; Calhelha, R.C.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Phenolic Composition and Bioactivity of Lavandula Pedunculata (Mill.) Cav. Samples from Different Geographical Origin. Molecules 2018, 23, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romo Vaquero, M.; García Villalba, R.; Larrosa, M.; Yáñez-Gascón, M.J.; Fromentin, E.; Flanagan, J.; Roller, M.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Espín, J.C.; García-Conesa, M.T. Bioavailability of the Major Bioactive Diterpenoids in a Rosemary Extract: Metabolic Profile in the Intestine, Liver, Plasma, and Brain of Zucker Rats. Mol Nutr Food Res 2013, 57, 1834–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truzzi, E.; Marchetti, L.; Gibertini, G.; Benvenuti, S.; Cappellozza, S.; Giovannini, D.; Saviane, A.; Sirri, S.; Pinetti, D.; Assirelli, A.; et al. Phytochemical and Functional Characterization of Cultivated Varieties of Morus Alba L. Fruits Grown in Italy. Food Chem 2024, 431, 137113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Y.; Velamuri, R.; Fagan, J.; Schaefer, J. Full-Spectrum Analysis of Bioactive Compounds in Rosemary (Rosmarinus Officinalis L.) as Influenced by Different Extraction Methods. Molecules 2020, 25, 4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Yan, J.; Zheng, D.; Sun, F.; Wang, J.; Han, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T. Comprehensive Chemical Profiling in the Ethanol Extract of Pluchea Indica Aerial Parts by Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Its Silica Gel Column Chromatography Fractions. Molecules 2019, 24, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celano, R.; Piccinelli, A.L.; Pagano, I.; Roscigno, G.; Campone, L.; De Falco, E.; Russo, M.; Rastrelli, L. Oil Distillation Wastewaters from Aromatic Herbs as New Natural Source of Antioxidant Compounds. Food Research International 2017, 99, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lech, K.; Witkoś, K.; Jarosz, M. HPLC-UV-ESI MS/MS Identification of the Color Constituents of Sawwort (Serratula Tinctoria L.) Euroanalysis XVII. Anal Bioanal Chem 2014, 406, 3703–3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetkovikj, I.; Stefkov, G.; Acevska, J.; Stanoeva, J.P.; Karapandzova, M.; Stefova, M.; Dimitrovska, A.; Kulevanova, S. Polyphenolic Characterization and Chromatographic Methods for Fast Assessment of Culinary Salvia Species from South East Europe. J Chromatogr A 2013, 1282, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalva, M.; Santoyo, S.; Salas-Pérez, L.; Siles-Sánchez, M.d.l.N.; Rodríguez García-Risco, M.; Fornari, T.; Reglero, G.; Jaime, L. Sustainable Extraction Techniques for Obtaining Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Compounds from the Lamiaceae and Asteraceae Species. Foods 2021, 10, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramberger, K.; Barlič-Maganja, D.; Bandelj, D.; Baruca Arbeiter, A.; Peeters, K.; Miklavčič Višnjevec, A.; Jenko Pražnikar, Z. HPLC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS Determination of Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity Comparison of the Hydroalcoholic and Water Extracts from Two Helichrysum Italicum Species. Metabolites 2020, 10, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peixoto, J.A.B.; Álvarez-Rivera, G.; Alves, R.C.; Costa, A.S.G.; Machado, S.; Cifuentes, A.; Ibáñez, E.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Comprehensive Phenolic and Free Amino Acid Analysis of Rosemary Infusions: Influence on the Antioxidant Potential. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeta, G.; Cifuentes, N.; Sepulveda, B.; Bárcenas-Pérez, D.; Cheel, J.; Areche, C. Untargeted Metabolomics by Using UHPLC–ESI–MS/MS of an Extract Obtained with Ethyl Lactate Green Solvent from Salvia Rosmarinus. Separations 2022, 9, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, S.; Moreira, E.; Grosso, C.; Andrade, P.B.; Valentão, P.; Romano, A. Phenolic Profile, Antioxidant Activity and Enzyme Inhibitory Activities of Extracts from Aromatic Plants Used in Mediterranean Diet. J Food Sci Technol 2017, 54, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, S.; Castilho, P.C. Helichrysum Monizii Lowe: Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Potential. Phytochemical Analysis 2012, 23, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, M.R.; Barros, L.; Dueñas, M.; Carvalho, A.M.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Fernandes, I.P.; Barreiro, M.F.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Exploring the Antioxidant Potential of Helichrysum Stoechas (L.) Moench Phenolic Compounds for Cosmetic Applications: Chemical Characterization, Microencapsulation and Incorporation into a Moisturizer. Ind Crops Prod 2014, 53, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevrenova, R.; Kostadinova, I.; Stefanova, A.; Balabanova, V.; Zengin, G.; Zheleva-Dimitrova, D.; Momekov, G. Phytochemical Profiling, Antioxidant and Cognitive-Enhancing Effect of Helichrysum Italicum Ssp. Italicum (Roth) G. Don (Asteraceae). Plants 2023, 12, 2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, S.; Pietrolucci, F.; Andreatta, S.; Chinyere Njoku, R.; Antunes Silva Nogueira Ramos, C.; Crimi, M.; Commisso, M.; Guzzo, F.; Avesani, L. Bioprospecting of Artemisia Genus: From Artemisinin to Other Potentially Bioactive Compounds. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnat, A.; Heitz, A.; Fraisse, D.; Carnat, A.P.; Lamaison, J.L. Major Dicaffeoylquinic Acids from Artemisia Vulgaris. Fitoterapia 2000, 71, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usmani, Z.; Sharma, M.; Tripathi, M.; Lukk, T.; Karpichev, Y.; Gathergood, N.; Singh, B.N.; Thakur, V.K.; Tabatabaei, M.; Gupta, V.K. Biobased Natural Deep Eutectic System as Versatile Solvents: Structure, Interaction and Advanced Applications. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 881, 163002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | LRI exp | LRI lit | LAI | LAV | MEL | ROS | SAO | SAS | ART | ECHI | HEL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-thujene | 928 | 928 | - | - | - | 0.25 | 0.19 | - | - | - | - |

| α-pinene | 935 | 936 | 0.28 | 0.60 | 0.18 | 38.79 | 3.84 | - | 1.53 | 5.56 | 24.53 |

| Camphene | 943 | 950 | 0.49 | 0.18 | - | 5.37 | 6.29 | - | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.99 |

| Sabinene | 969 | 973 | 0.25 | 0.42 | - | 2.58 | 4.39 | - | - | - | 0.15 |

| β-pinene | 971 | 975 | - | 0.15 | 1.05 | - | 0.12 | - | 0.17 | 1.33 | 1.07 |

| Octanone | 988 | 985 | 0.61 | 0.43 | - | 0.62 | - | - | - | - | 0.17 |

| Myrcene | 989 | 992 | 0.97 | 1.21 | 0.54 | 2.55 | 2.00 | 1.40 | 0.15 | 7.98 | - |

| α-phellandrene | 1001 | 1005 | - | - | - | 0.30 | - | - | - | 0.76 | - |

| δ-3-carene | 1007 | 1010 | 0.12 | 0.48 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| α-terpinene | 1017 | 1017 | 0.41 | 0.18 | - | 0.56 | - | - | - | - | 0.24 |

| p-cymene | 1024 | 1026 | 0.67 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.23 | - | 0.89 | 0.29 |

| Limonene | 1029 | 1030 | 0.43 | 1.07 | - | - | 21.42 | - | 3.63 | - | 7.77 |

| 1,8-cineole | 1031 | 1032 | 6.16 | 1.62 | - | 18.55 | - | - | - | - | 0.76 |

| cis-β-ocimene | 1037 | 1039 | 0.49 | 3.04 | - | - | - | 0.37 | 11.50 | - | - |

| trans-β-ocimene | 1049 | 1049 | 0.26 | 4.04 | - | - | - | 0.63 | 15.70 | - | 0.32 |

| γ-terpinene | 1058 | 1061 | 0.11 | 0.13 | - | 1.12 | - | - | - | - | 0.71 |

| Terpinolene | 1085 | 1088 | - | - | - | 0.91 | 0.11 | 0.11 | - | - | 0.21 |

| Linalool | 1098 | 1102 | 20.19 | 35.19 | 0.61 | 1.82 | 0.15 | 15.87 | - | - | 0.87 |

| α-thujone | 1104 | 1101 | - | - | - | - | 10.70 | - | - | - | - |

| 6-camphenol | 1105 | 1106 | 0.73 | - | 0.21 | 0.26 | - | - | - | - | - |

| α-fenchol | 1114 | 1116 | 2.22 | 1.04 | 0.25 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| β-thujone | 1115 | 1112 | - | - | - | - | 5.70 | - | - | - | - |

| Trans-rose oxide | 1126 | 1128 | 0.20 | - | - | 0.31 | - | - | 0.24 | - | - |

| Camphor | 1144 | 1145 | 3.52 | 0.35 | - | 3.83 | 22.41 | - | - | - | - |

| Nerol oxide | 1153 | 1148 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.72 |

| Citronellal | 1155 | 1157 | - | - | 9.43 | 0.17 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Menthone | 1157 | 1155 | - | - | 0.22 | 1.97 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Borneol | 1166 | 1168 | 1.80 | 1.32 | - | 3.79 | 1.62 | - | - | - | - |

| Lavandulol | 1169 | 1172 | 0.25 | - | - | 0.78 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Terpinen-4-ol | 1175 | 1181 | 1.01 | 5.59 | - | 0.78 | 0.43 | - | - | - | 0.31 |

| p-cymen-8-ol | 1188 | 1185 | 0.24 | - | 0.76 | - | 0.19 | - | - | - | - |

| α-terpineol | 1189 | 1193 | 0.34 | 0.64 | - | 1.03 | - | 2.09 | - | - | 0.35 |

| Myrtenal | 1194 | 1195 | 0.31 | 0.15 | - | 0.29 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Estragole | 1200 | 1195 | - | 65.15 | |||||||

| Verbenone | 1207 | 1204 | 6.04 | ||||||||

| Nerol | 1230 | 1232 | - | - | 0.18 | - | - | 0.19 | - | - | 1.04 |

| Citronellol | 1233 | 1233 | - | - | 0.18 | - | - | 0.15 | - | - | - |

| Neral | 1245 | 1245 | 0.15 | - | 6.49 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Piperitone | 1255 | 1252 | 0.13 | - | 0.50 | 1.23 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Linalyl acetate | 1264 | 1259 | 38.63 | 34.01 | 0.30 | - | - | 70.96 | - | - | - |

| Geraniol | 1267 | 1267 | 0.15 | - | 2.02 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Geranial | 1274 | 1269 | - | - | 12.74 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bornyl acetate | 1288 | 1288 | 0.32 | 0.80 | 0.33 | 1.32 | 1.50 | - | 0.11 | - | - |

| Lavandulyl acetate | 1294 | 1290 | 3.13 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| δ-elemene | 1338 | 1337 | 0.73 | - | 0.24 | - | - | - | - | 0.27 | - |

| Neryl acetate | 1367 | 1368 | 0.21 | 0.29 | - | - | - | 0.73 | - | - | 1.54 |

| α-copaene | 1377 | 1376 | 0.29 | - | 0.69 | - | 0.11 | 0.36 | - | 0.24 | 1.31 |

| Geranyl acetate | 1385 | 1386 | - | - | 3.50 | - | - | 1.43 | - | - | - |

| β-bourbonene | 1389 | 1384 | - | - | 0.41 | - | 0.11 | 0.20 | - | - | - |

| β-cubebene | 1392 | unknown | 0.44 | 0.67 | 0.39 | - | - | - | - | 0.94 | - |

| β-elemene | 1395 | 1390 | 0.20 | - | - | - | - | 0.14 | - | - | - |

| Italicene | 1404 | 1409 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.65 |

| Cis-α-bergamotene | 1416 | 1415 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.86 |

| β-caryophyllene | 1420 | 1420 | 1.97 | 3.30 | 17.08 | 2.46 | 4.62 | 0.99 | 0.23 | 2.50 | 3.49 |

| α-humulene | 1431 | 1433 | - | 0.34 | 1.93 | - | - | - | - | 0.65 | - |

| Trans-α-bergamotene | 1440 | 1436 | 0.12 | 0.26 | - | - | 1.80 | - | - | - | - |

| Neryl propanoate | 1455 | 1452 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.47 |

| β-farnesene | 1456 | 1457 | 1.20 | - | 0.15 | - | - | - | - | 1.13 | 0.31 |

| alloaromadendrene | 1464 | 1466 | - | - | - | 0.34 | 0.23 | - | - | - | - |

| γ-curcumene | 1478 | 1480 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.01 |

| ar-curcumene | 1483 | 1484 | 0.37 | 0.43 | - | - | 0.15 | - | 0.38 | - | 9.85 |

| β-selinene | 1485 | 1489 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.25 | - | 2.41 |

| Germacrene D | 1488 | 1481 | - | - | 1.10 | - | 0.12 | 2.83 | - | 66.43 | - |

| Italidione II | 1491 | 1493 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 9.55 |

| α-selinene | 1499 | 1496 | - | - | - | - | 0.75 | 0.56 | - | 1.86 | 6.38 |

| β-bisabolene | 1510 | 1511 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.26 |

| β-curcumene | 1513 | 1513 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.37 |

| γ-cadinene | 1522 | 1524 | 0.12 | - | 0.41 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.14 |

| δ-cadinene | 1526 | 1523 | 0.69 | 0.24 | 0.19 | - | 0.28 | - | - | 1.31 | 0.11 |

| Nerolidol | 1559 | 1563 | - | - | 0.97 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Spathulenol | 1580 | 1577 | - | - | - | - | 0.76 | - | - | 0.57 | - |

| Italidione III | 1583 | 1583 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.96 |

| Caryophyllene oxide | 1590 | 1589 | 2.35 | 0.23 | 20.64 | 0.14 | 0.96 | 0.13 | - | 1.65 | - |

| TOTAL | 93.64 | 98.71 | 94.04 | 99.53 | 92.00 | 99.37 | 99.54 | 96.82 | 87.01 |

| No | Rt (min) | Molecule | (M-H) (m/z) | Error (ppm) | Fragments (m/z) | Formula | Molecular weight (g/mol) | Extract | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EtOH | NADES | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2.52 | Danshensu | 197.0449 | 0.70 | 179.0342, 135.0441, 123.0440, 72.9918 | C9H10O5 | 198.052824 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

+ + + + + + - - - |

+ + + + + + - - - |

[44] |

| 2 | 2.6 | Protocatechuic acid hexose | 315.0723 | -2.19 | 153.0184, 152.0106, 109.0282, 108.0205 | C13H16O9 | 316.079435 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

+ + + + + + + + - |

+ + + + + + + + - |

[45] |

| 3 | 3.16 | Caftaric acid | 311.0408 | -1.58 | 179.0342, 149.0082, 135.0441 | C13H12O9 | 312.048135 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

+ - - - - - - + - |

+ - - - - - - + - |

[46] |

| 4 | 3.79 | Caffeoylquinic acid isomer I | 353.0876 | -0.96 | 191.0554, 179.0342, 135.0441 | C16H18O9 | 354.095085 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - + + - + - + |

- - - + + - + - + |

[45] |

| 5 | 4.34 | Caffeoyl hexose isomer I | 341.0878 | -1.58 | 179.0342, 161.0235, 135.0442 | C15H18O9 | 342.095085 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - + + + - - - - |

+ - + + + - + + - |

[47] |

| 6 | 4.79 | Coumaroyl quinic acid | 337.0931396 | -2.36 | 191.0555, 163.0392, 119.0490, 93.0333 | C16H18O8 | 338.100170 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - - - - + - + |

- - - - - - + - + |

[48] |

| 7 | 5.01 | Coumaroyl hexose | 325.0929 | -1.71 | 183.0114, 163.0392, 119.0492, 93.0333 | C15H18O8 | 326.100170 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

+ + + + - - + - + |

+ + + + + - + - + |

[49] |

| 8 | 5.35 | Caffeoyl hexose isomer II | 341.0877 | -1.29 | 179.0342, 161.0235, 135.0441 | C15H18O9 | 342.095085 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - + + + - - - - |

+ - + + + - + + - |

[47] |

| 9 | 5.66 | Caffeoylquinic acid isomer II | 353.0876 | -0.96 | 191.0554, 179.0342, 135.0441 | C16H18O9 | 354.095085 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - + + - + - + |

- - - + + - + - + |

[45] |

| 10 | 6.42 | Feruloylquinic acid | 367.1031 | -0.52 | 193.0499, 149.0598, 134.0363 | C17H20O9 | 368.110735 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - - - - + - - |

- - - - - - + - - |

[50] |

| 11 | 6.48 | Feruloyl hexose | 355.1035 | -1.66 | 193.0499, 149.0598, 134.0362, 119.0339 | C16H20O9 | 356.110735 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

+ + - + + - + - - |

+ + - + + - + - - |

[49] |

| 12 | 8.92 | Luteolin /kaempferol diglucuronide | 637.1053 | -1.89 | 461.0721, 285.0405, 255.0298, 227.0349 |

0 | 638.111920 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - - + - - - - |

+ + - - + - - - - |

[49] |

| 13 | 9.32 | Myricetin hexose | 479.0837 | -2.36 | 317.0305, 271.0250 | C21H20O13 | 480.090395 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - - - - - - + |

- - - - - - - - + |

[50] |

| 14 | 9.63 | Quercetin glucuronide | 477.0680 | 2.63 | 301.0359, 300.0286, 271.02567, 255.0287 |

C21H18O13 | 478.074745 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - - + - - - - |

- - - - + - - - - |

[51] |

| 15 | 9.68 | Quercetin hexose | 463.0888 | -2.47 | 301.0359, 300.02719, 271.02567, 255.02921 | C21H20O12 | 464.095480 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - + - - - - + |

- - - + - - - - + |

[45] |

| 16 | 9.78 | Yunnaneic acid D | 539.1196 | -1.20 | 359.0777, 297.0771, 197.0452, 179.0342, 161.0236, 135.0441 |

C27H24O12 | 540.126780 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

+ - + + - - - - - |

+ + + + - - - - - |

[52] |

| 17 | 9.86 | Chicoric acid | 473.0692 | 5.93 | 311.0411, 293.0308, 179.0343, 149.0082 | C22H18O12 | 474.079830 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - + - - - - + - |

- - + - - - - + - |

[53] |

| 18 | 10.02 | Yunnaneic acid F | 597.1254 | -1.62 | 311.0930, 197.0449, 179.0342, 135.0441 | C29H26O14 | 598.132260 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - + + - - - - |

+ - - + + - - - - |

[54] |

| 19 | 10.51 | Rutin | 609.1468 | -2.03 | 300.0278, 271.0251, 255.0301 | C27H30O16 | 610.153390 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - + - - + + - |

+ - - + - + + + - |

[55] |

| 20 | 10.74 | Luteolin /kaempferol hexose | 447.0939 | -2.60 | 285.0405, 255.0298, 227.0349 |

C21H20O15 | 448.100564 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - - + + - - + |

- - - - + + - - + |

[56] |

| 21 | 10.90 | Luteolin /kaempferol glucuronide | 461.0731 | -2.37 | 285.0405, 255.0298, 227.0349 |

C21H18O12 | 462.079830 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

+ + - + + + - - - |

+ + + + + + - - - |

[49] |

| 22 | 11.06 | Rosmarinic acid hexose | 521.1304 | -1.69 | 359.0766, 197.0449, 179.0342, 161.0236, 135.0440 | 0 | 521.129520 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - + + + - - - - |

- - + + + - - - - |

[55,57,58] |

| 23 | 11.81 | Luteolin /kaempferol rutinose | 593.15184 | 1.09 | 285.04041, 255.02995, 227.03470, | C27H30O15 | 594.15912 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - - + - + - + |

- - - + + - + - + |

[59] |

| 24 | 11.92 | Rosmarinic acid | 359.0776 | -2.52 | 197.0449, 179.0344, 161.0235, 135.0441 | C18H16O8 | 360.084520 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

+ + + + + + - - - |

+ + + + + + + - - |

[60] |

| 25 | 12.09 | Apigenin hexose | 431.0988 | -2.37 | 269.0454, 117.0332 | C21H20O10 | 432.105649 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

+ + - - - + - - - |

+ + + - - + - - - |

[56] |

| 26 | 12.30 | Apigenin glucuronide | 445.0782 | -2.49 | 269.0457, 117.0334 | C21H18O11 | 446.084915 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - - - + - - - |

- - - - + + - - - |

[54] |

| 27 | 12.43 | Dicaffeoyl quinic acid | 515.14105 | 0.73 | 353.08780, 191.05553, 179.03413, 135.04416 | C25H24O12 | 516.147900 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - - - - + - + |

- - - - - - + - + |

[59] |

| 28 | 12.72 | Coumaroyl-caffeoylquinic acid | 499.1250 | -1.92 | 353.0886, 337.0932, 191.0555, 173.0447 | C25H24O11 | 500.131865 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - - - - + - - |

- - - - - - + - - |

[61] |

| 29 | 12.86 | Methylluteolin-O-glucuronide (Kaempferide glucuronide) | 475.0888 | -2.41 | 299.0561, 284.0327 | C22H20O12 | 476.095480 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - + + + - - - |

- - - + + + - - - |

[62,63] |

| 30 | 12.89 | Salvianolic acid K | 555.1122 | 3.01 | 359.0778, 179.0341, 161.0235, 135.0441 | C27H24O13 | 556.121695 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - + - + + - - - |

+ - + + + + - - - |

[62] |

| 31 | 13.28 | Caffeoyl-feruloylquinic acid | 529.1356 | -1.88 | 367.1036, 179.0340, 161.0236, 135.0442 | C26H26O12 | 530.142430 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - - - - + - - |

- - - - - - + - - |

[61] |

| 32 | 13.47 | Salvianolic acid H (lithospermic acid) | 537.1042 | -1.67 | 359.0777. 295.0613. 179.0334. 161.0234. 135.0441 | C27H22O12 | 538.111130 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - - + + - - - |

- - + + + + - - - |

[64] |

| 33 | 15.30 | Salvianolic acid A | 493.1140 | -1.06 | 295.0613, 197.0451, 179.0343, 135.0442 | C26H22O10 | 494.121300 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

+ - - + + - - - - |

+ - + + + + - - - |

[44] |

| 34 | 15.33 | Sagecoumarin isomer I | 535.0882 | -1.02 | 359.0775, 197.0443, 179.0341, 177.0186, 161.0234, 135.0443 | C27H20O12 | 536.095480 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - + - + - - - - |

- - + - + + - - - |

[65] |

| 35 | 16.03 | Sagecoumarin isomer II | 535.0882 | -1.02 | 359.0775, 197.0443, 179.0341, 177.0186, 161.0234, 135.0443 | C27H20O12 | 536.095480 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - + - + - - - - |

- - + - + + - - - |

[62] |

| 36 | 16.21 | Salvianolic acid C | 491.0989 | -2.14 | 311.0566, 265.05, 179.0360, 135.0442 | C26 H20 O10 | 492.105649 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - + + - - - - - |

+ - + + - + - - - |

[44] |

| 37 | 12.13 | Salvianolic acid B | 717.1473 | -2.42 | 519.0939, 339.051 161.023, 135.0444 | C36H30O16 | 718.153390 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

+ - + - + + - - - |

+ - + - + + - - - |

[52] |

| 38 | 12.31 | Sagerinic acid | 719.1624 | 1.64 | 359.0776, 197.0449, 179.0342, 161.0235 | C36H32O16 | 720.169040 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

+ - + + + + - - - |

+ - + + + + - - - |

[62] |

| 39 | 15.83 | Micropyrone | 251.1289 | 2.39 | 207.1385, 151.1118, 113.0960 | C14H20O4 | 252.136160 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - - - - - - + |

- - - - - - - - + |

[66] |

| 40 | 22.70 | Rosmadial (safficinolide) | 343.1552 | -1.75 | 299.16509 | C20 H24 O5 | 344.162375 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - + + - - - - |

- - - + + - - - - |

[67] |

| 41 | 22.88 | Carnosol | 329.1758 | -1.60 | 285.1862 | C20H26O4 | 330.183110 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - + + - - - - |

- - - + + - + - - |

[60,68] |

| 42 | 23.52 | Arzanol | 401.1609 | -2.17 | 247.0976, 235.0974, 191.1071, 166.0263, 153.0548, 109.0647 | C22H26O7 | 402.167855 | LAI LAV MEL ROS SAO SAS ART ECHI HEL |

- - - - - - - - + |

- - - - - - - - + |

[66] |

| Name | Eutectic mixture | Molar ratio |

|---|---|---|

| CCA11 | Choline chloride : Citric acid | 1 : 1 |

| CCA12 | Choline chloride : Citric acid | 1 : 2 |

| CLA11 | Choline chloride : Lactic acid | 1 : 1 |

| CLA12 | Choline chloride : Lactic acid | 1 : 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).