1. Introduction

Often overlooked, soil is a vital, finite, and living natural resource essential to almost all ecosystems. It involves complex processes and can be viewed as an ecosystem in itself (Joyalata Laishram et al., 2012). Soil contributes with essential environmental, social, and economic functions (Blum, 2005), which must be protected (TSSP, 2006). Soils produce and provide us with biomass, food, and raw materials, while also helping to filter, buffer, and transform substances between the atmosphere, groundwater, and plant cover, affecting, in this way, the water cycle, gas exchange (Blum, 2005; Schoonover & Crim, 2015), nutrients cycle, and carbon sequestration (TSSP, 2006; Kibblewhite, Miko & Montanarella, 2012; Schoonover & Crim, 2015). Moreover, soil serves as a platform for human activities, natural environments, and heritage, and is also a habitat and gene pool (TSSP, 2006). Soil, being a habitat for microorganisms and biota, is vital for biodiversity, holds more species than all above-ground life combined (Blum, 2005; Schoonover & Crim, 2015). Soil biodiversity is crucial for soil functions and ecosystem services, which are important for human well-being.

Therefore, preventing soil degradation is essential and more cost-effective than its rehabilitation (FAO, 2015). Soil value is often ignored until soil quality is degraded and the provision of soil services declines (Schoonover & Crim, 2015). Healthy soils are essential for climate change mitigation and adaptation, absorbing water and reducing the risks of floods and droughts, and so contribute to long-term climate, biodiversity, and economic European Union objectives (European Commission, 2021).

Several European and world policies deal with soil protection and carbon neutrality, the EU Green Deal is a growth policy to create a fair, prosperous society with a resource-efficient economy with no net greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Protecting nature and enhancing human health are crucial for achieving these goals (EC, 2021). The Global Soil Partnership Action Framework 2022-2030 (GSP) aims to enhance and preserve at least 50 percent of the world’s soil health by 2030. Its mission is to promote better governance of soil resources to ensure food security and support essential ecosystem services, involving all stakeholders, including politicians, scientists, and the public, which is vital for effective soil governance. In this context, increasing awareness and education about soils is necessary to fulfil the GSP’s mission (FAO, 2022). The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development includes Goal 15: “Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss”, and specifically, Target 15.3 “By 2030, combat desertification, restore degraded land and soil, including land affected by desertification, drought and floods, and strive to achieve a land degradation-neutral world” (UN, 2015).

Soil governance affects soil usage; the need for biomass may lead to short-term soil management, harming soil quality (Juerges & Hansjürgens, 2018). Soils are critical for sustainable land use, namely at present when humanity faces global challenges like food security, climate change, water scarcity, and biodiversity loss (Bouma et al., 2012; Blum, 2004). However, several processes contribute to soil degradation, such as erosion, flooding, salinization, loss of organic matter, contamination, sealing, compaction, biodiversity decline, and landslides (Hannam & Boer, 2004; TSSP, 2006). Decisions about acceptable levels of soil degradation are social and political. These decisions depend on the level of caution applied, ranging from strict conservation, where degradation does not exceed natural soil regeneration, to situations where avoiding degradation is deemed to have too high economic costs (Kibblewhite, Miko & Montanarella, 2012).

Prevention and remediation of soil degradation are addressed indirectly through EU policies and Directives (Posthumus et al., 2011). The EU’s large-scale assessment on soil pollution shows that current policies fail to prevent pollution in soils (Vieira et al, 2024). Soil degradation and different Member State responses lead to unequal conditions for market competitors due to differing soil protection laws (European Commission, 2021). Soil degradation has transnational issues like erosion, chemical contamination, and international markets (Glæsner, Helming & De Vries, 2014). However, not many countries have soil protection legislation focusing on specific soil threats, which toughens the importance of a European soil monitoring system (Panagos, P. et al., 2025). The principal functions of soil should influence the creation of legal frameworks; even so, there are many domestic laws referencing individual soil functions (Hannam & Boer, 2004; Vrebos et al., 2017), but when directives address soil functions individually, they often overlook the soil’s multifunctionality (Glæsner, Helming & De Vries, 2014).

This study aims to carry out a critical analysis of Portuguese and European Union soil legislation, based on the information available in the SoiLEX database. The scientific literature has not yet been adequately explored; thus, this study proposes to verify the contributions of that legislation to soil protection, analysing the SoiLEX soil threats This study is important for highlighting the invisibility of soil protection and multifunctionality within the legal framework, and could be replicated in other countries that wish to assess how soil protection and threats are referred in their legislation, to improve and update it accordingly.

After this introduction, the paper is structured into six additional sections.

Section 2 reviews scientific literature on sustainable soil management and soil governance;

Section 3 describes the methodology used for the critical analysis of the Portuguese and European soil legislation, based on the information available in the SoiLEX database;

Section 4 presents the findings and results, including an analysis of the Portuguese and European soil legislation; and Section 6 contains the conclusions of the study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Land Management and Policies

Sustainability relies on managing the soil’s limited resources (Blum, 2005). Soil management is sustainable when the support, provision, regulatory, and cultural services it offers are maintained or improved, without harming soil functions or biodiversity (FAO, 2015; Kibblewhite, Miko & Montanarella, 2012; Martinho et al, 2024). Effective soil protection needs to prevent detrimental land use and management practices (Kibblewhite, Miko & Montanarella, 2012), so policies should directly deal with soil threats and functions to promote sustainable soil management practices. When soil functions are treated individually on different policies, the soil’s multifunctionality can be lost (Glæsner, Helming & De Vries, 2014).

Effective sustainable soil management encompasses several features, including minimal soil erosion, preserved soil structure, adequate surface coverage, stable soil organic matter, optimal nutrient availability, low salinization, efficient water retention, safe contaminant levels, a soil biodiversity that supports various biological processes, optimized resource inputs, and reduced soil sealing (FAO, 2017) to cope with climate change (EC, 2023). Well-managed soils that retain carbon and promote nutrient cycling are essential for resilience on production farms (Leal Filho et al., 2023). Farmers need new governance mechanisms to manage short-term economic subjects and improve long-term soil quality (Helming et al., 2018). Agricultural extension has a crucial role in informing farmers about the benefits of specific practices and issues like soil erosion, fertility, yield, pollution, and flood risk (Posthumus & Morris, 2010).

2.2. EU and Portuguese Legislation for Soil

In the EU, various policies and laws affect soil functions, resulting in diverse outcomes across regions. Some policies directly address specific functions, while others have indirect effects based on the policy and local area. Additionally, existing European legislation, such as that concerning industrial emissions, water, and bioeconomy strategies, offers some indirect protection to soil, without specific soil targets or limits (Vrebos et al., 2017; Helming et al., 2018). According to Prager et al. (2011), most policies focus on broad environmental goals, not directly on soil conservation, but they still affect how farmers manage soil. Their effectiveness is usually measured through outcomes like water quality or biodiversity rather than soil health itself.

Glæsner, Helming & De Vries (2014) highlighted the need for new, specific legislation on soil conservation. They assessed existing policies to determine their effectiveness in protecting against soil threats and enhancing soil functions. As each soil threat is closely linked to a soil function, addressing all threats is crucial for maintaining soil functions (Glæsner, Helming & De Vries, 2014), and adopting soil ecosystem services in policy making helps the evaluation of natural resources and environmental strategies (Adhikari & Hartemink, 2016).

The European Commission sees soil protection as a key issue that must be included in all environmental and agricultural policies. European legislation was fragmented and did not adequately address threats like soil compaction and erosion (Heuser, 2022). After the rejection in 2014 of the former soil directive proposal from 2006 by five countries. (Germany, France, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Austria), member States proceed on their own in implementing sectoral policies (Ronchi et al., 2019). Those five countries that blocked the soil proposal Directive have national legislation on soil regarding degradation and contamination that is stricter than the proposed European directive proposal (Stankovics, Tóth & Tóth, 2018).In 2023, a new European soil directive was proposed. As stated in the Explanatory Memorandum of the soil directive proposal (2023): “Current EU and national policies have made positive contributions to improving soil health. But they do not tackle all the drivers of soil degradation and therefore significant gaps remain” (European Commission, 2023).

On 29th of September 2025, the Directive on Soil Monitoring and Resilience was adopted by the European Council and finally approved by the European Parliament, on 23rd of October 2025 (EEB, 2025). This directive aims to achieve healthy soils across the European Union by 2050, to provide ecosystem services, address climate change and biodiversity loss, and ensure resilience to natural disasters and food security. The framework includes monitoring soil health, soil resilience, and managing contaminated sites with common methodologies and soil descriptors and creates classes to portray soil health (Council of European Union, 2025).

Portugal introduced its first Soil Law in 1970 (Decree-Law 576/70) to address urban land availability issues. When Portugal joined the European Economic Community in 1986, it greatly advanced Portugal’s environmental policies, enhancing existing legislation. (Castelo-Grande et al., 2018). In Portugal, legislation that directly regulates soil threats is focused on the improvement of soil fertility in agriculture, reducing erosion, and preventing pollution. The Law on the Use of Sewage Sludge from 2009 and the Law on Distribution, Sale and Application of Plant Protection Products for Professional Use, and the Manual of Agricultural Good Practices, consist of soil and water conservation (Ronchi et al., 2019). Rodrigues et al. (2009) suggested creating a national strategy for managing contaminated land in Portugal that fits a wider soil protection policy, addressing threats like soil erosion and organic matter loss, and Castelo-Grande et al. (2018) refer that Portugal urgently needs a soil framework to address legislative gaps and align with other member states.

3. Methodology

The SoiLEX - Soil-related legal instruments and soil governance is a global database available at FAO Soils Portal, which was chosen as the basis for data collection on this study. The platform allows searching legislation by country or by keyword related to soil and has a classification system that helps to identify the importance of documents concerning keywords, legislation, essence, and year (FAO, 2025b). The legal instruments on the platform database were collected from FAOLEX and EU Sol Wiki, and the platform is managed by the Global Soil Partnership within the Water and Soil FAO division (FAO, 2025a). A critical analysis of Portuguese and European legislation was carried out on data from the SoilLEX database (FAO, 2025a). After searching the soil-related documents on SoiLEX database by country, selecting Portugal and the European Union, the legislative acts collected were then analysed, verifying the contributions that this legislation had towards the soil, in respect to SoiLEX keywords.

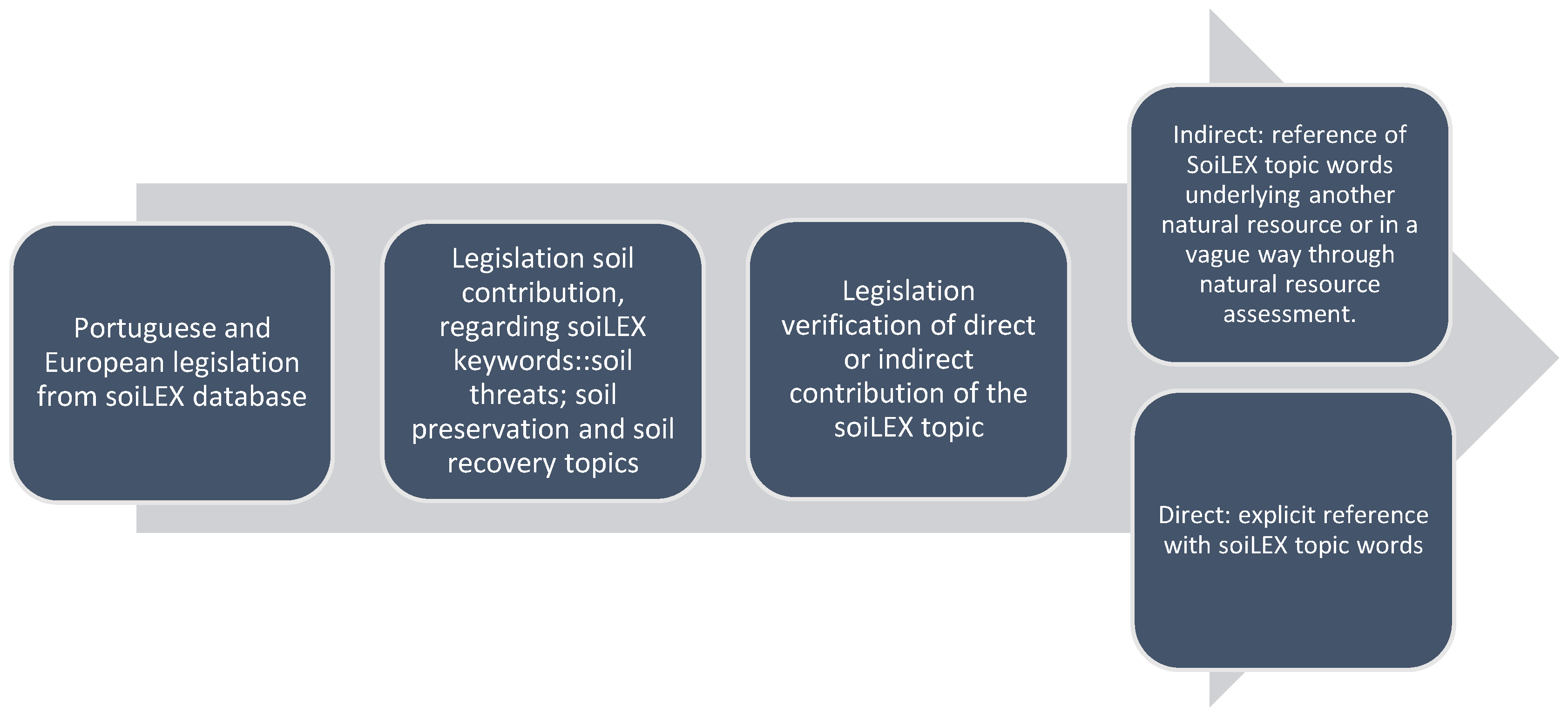

The analysis examined whether Portuguese and European legislation addressed the subject of SoiLEX either directly or indirectly. It was agreed that any explicit mention of the SoiLEX subject would be deemed a direct reference, as would, for instance, the phrase “soil protection,” which would be interpreted as a direct reference to soil conservation, as well as the words “soil contamination” for the topic “soil pollution”. When the SoiLEX subject was indirectly referenced as underlying another natural resource threat or when it was vaguely alluded to via natural resource assessments, the reference would be indirect (

Figure 1). This stipulation was adapted from the methodology of Paleari (2017).

4. Results and Discussion

The research on the SoiLEX database (FAO, 2025a) resulted in a list of Portuguese and European Union soil legislation acts (

Table 1). The critical analysis of that legislation produced 26 tables.

Table 1 lists Portuguese and EU legislation documents according to SoiLEX Topics, and

Table 2 and

Table 3 summarize the direct and indirect references to SoiLEX Topics in Portuguese and European legislation, respectively.

Tables 4 to 26 are found in the annex, outlining the legislation from SoiLEX and the main contributions to specific SoiLEX topics

.

According to Portuguese legislation in the SoiLEX database, 52 of 81 legislative acts address soil-related topics (

Table 2). Most legislation focuses on soil conservation, quality, and pollution, but provides limited coverage on soil organic carbon loss, nutrient imbalance, soil monitoring, and soil restoration (

Table 1).

The most directly referred to SoiLEX topics in the Portuguese legislation are Soil Pollution, Soil Conservation, Waterlogging, and Soil Erosion (

Table 2). Those are soil threats that have been safeguarded in Portuguese legislation for a long time. Even though Decree Law 235/97 and the National Action Plan are more concerned with water protection, soil protection is implied but not highlighted.

The topics Soil Conservation and Soil Quality are alluded to indirectly in many legislative acts (

Table 2), as they are underlined in these acts. Regarding Soil Quality (

Table 2), Decree Law 10/2010 and Decree Law 151-B/2013, directly address this topic, although without a detailed approach. At Council Minister Resolution 78/2014, it indirectly refers to the Soil Quality topic, with policy measures for conservation of land use, and the remaining legislative acts are related to the Soil Quality topic regarding protecting the environment or avoiding soil threats.

Of the seventeen legislative acts listed on the Soil Conservation topic (

Table 1), eleven do not make direct reference to soil conservation. It indirectly brings up on the “Code of Good Agricultural Practices,” which indirectly promotes soil conservation, or through legislative acts that referee (

Annex Table 4): soil pollution prevention measures, soil impact assessments in preliminary assessment of floods, the adoption of measures to maintain or recover landscape patterns and ecological processes, the sustainability of agricultural activity and preservation of natural resources, the adoption of practices and products that are safer for human health and the environment, soil assessment for possible environmental effects, the water contamination prevention from chemical products (thereby promoting sustainable land use), the inspection of application equipment, as if not in good conditions, will contribute to the contamination of the soil.

Regarding the Soil Erosion topic, four of the seven legislative acts in the SoiLEX database directly mention this topic, and indirectly, through the approval of the “Code of Good Agricultural Practices”, which implicitly addresses the prevention of soil erosion, the flood risk management, or soil loss because of inappropriate use. The topic of Soil Biodiversity Loss is becoming increasingly prominent because of the importance of increasing organic matter for carbon sequestration. Maintaining soil biodiversity is essential to protect soil functions (FAO, 2015), and this topic is directly mentioned in the Resolution of the Council of Ministers 55/2018 and in several legislative decrees, not specifically as soil biodiversity. It should be noted that there is only indirect contribution in three legislative acts for soil compaction, though being a soil threat that affects soil biodiversity and soil structure, thus important for the incorporation of organic matter and water retention of the soils. Only one legislative document makes a direct reference to the Soil Sealing topic, and only two legislative acts refer to Soil Restoration: Decree Law 10/2010, which addresses it directly, and Decree Law 183/2009, which contributes indirectly. However, the Council of Ministers Resolution 78/2014 addresses the recovery of affected areas, and this legislative act was not included in the “Soil Restoration” SoiLEX database list. The Soil Organic Carbon Loss topic is little referred to either directly or indirectly. The Minister’s Resolution Council 6-B/2015 vaguely refers to the threat of soil salinization, although the topic of Salinization does not appear in the SoiLEX database list for Portugal.

Concerning the European legislation in the SoiLEX database (

Table 3), as in Portuguese legislation, the topics Soil Pollution, Soil Conservation, and Waterlogging are the most frequently mentioned, but in this case, the indirect form predominates. The Soil Organic Carbon Loss, Soil Monitoring, and Soil Erosion topics are directly referred in European legislation. The Soil Monitoring topic is directly referred to in the INSPIRE Directive, which sets general rules for establishing the infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community to support environmental policies, and at the Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on Soil Monitoring and Resilience, which establishes a soil monitoring scheme to enhance soil health. Soil Erosion topic is pointed out in two regulations concerning rural development that refers that payments should be for forest holders practicing climate-friendly conservation, and in the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) with GAEC (Good Agricultural and Environmental Conditions) to limit erosion, as Panagos, P. et al., (2025) stated in their study, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) address soil protection in agricultural lands. The Soil Sealing, Soil Restoration, Soil Quality, Nutrient Imbalance, and Soil Biodiversity Loss topics are mentioned indirectly in only one legislative document, as also referred to in Glæsner, Helming & De Vries (2014). Considering the European Community climate neutrality goal, carbon sequestration and conservation are relevant issues, and thus Soil Organic Carbon Loss topic is directly mentioned in four European legislative acts from SoiLEX database list. There isn’t any legislative act that refers directly or indirectly to soil salinisation, soil acidification, and soil compaction, as stated on the studies of Glæsner, Helming & De Vries (2014), of Ronchi et al. (2019), and Heuser (2022).

Member states are expected to update their legislation to align with the new Soil Monitoring and Resilience Directive, adopted on 23 October 2025, focusing on soil health and adjusting to new methodologies, monitoring, and reporting requirements. By monitoring soil health, soil degradation like biodiversity loss, contamination, carbon and nutrient balances can be prevented (Panagos, P.et al., 2025). This provides a chance to include those indirect SoiLEX topics references in an explicit way in Portuguese legislation.

Portugal has been developing a plan to build a model for a soil monitoring system. The “Portuguese Soil Partnership”, a partnership of 51 members of Public Administration, Producer Associations and Organizations, Business sector, Education and R&D, which is led by DGADR (Direção Geral de Agricultura e Desenvolvimento Rural), has been promoting discussions with the scientific community about the challenges that will arise in the transposition of the SMR directive. It promotes the “National Soil Observatory” project that aims to be the main provider of data on soil quality and health.(DGADR, 2025). In respect to the Soil Sealing threat, another project “UnSealingCities - Planning interventions to mitigate the impacts of soil sealing and adapt to climate change in urban areas”, led by DGT (Direção Geral de Território) is developing and aims to contribute to improve local planning practices and policies through guidance for regulating soil impermeability, inventorying measures and policies to reduce soil impermeability exposures, and through data sources, indicators, and methodologies for soil monitoring in cities and also involvements for eliminating impermeability in municipalities with high soil impermeability (DGT, 2025). These projects are important for the transposition of the Soil Monitoring and Resilience Directive to Portugal.

Portugal’s Law 31/2014 focuses on public policy about soils and land use, forgetting the importance of the soil as a crucial resource (Castelo Grande, 2018), even though the Decree Law 117/2024, which is a special reclassification regime for urban land, will increase the probability of the soil sealing threat in Portugal. The Decree-Law 117/2024) should be updated to align with this new directive. Member States are expected also to support and train landowners and soil managers, but it is missed to make soil protection more evident and enlightening, to be a way of raising community awareness of soil protection and conservation. It is important to address and teach this theme in all sectors of activity, and even in schools, universities, or in the media, in a transversal way. In this way, the entire community understands the importance of soil for people’s well-being.

5. Conclusion

From this critical analysis of Portuguese and European legislation, considering the topics in the SoiLEX database, it was found that these were addressed directly and indirectly, and that some soil threats were not addressed either directly or indirectly by legislation, such as soil salinisation, soil acidification, and soil compaction in European legislation. In Portuguese legislation, the SoiLEX topic of soil compaction was only addressed indirectly and salinisation in a vague way, not even having been flagged by the SoiLEX database. It is therefore important that these topics be addressed in legislation and directly. It is also noted that soil legislation is fragmented across various legislative acts of different sectors. Many SoiLEX topics were indirectly addressed, and it is now an opportunity to be explicit in the legislation because of the new Soil Monitoring and Resilience Directive. It is also fundamental to transmit the importance of soil health, from kindergarten to university, so that with everyone’s contribution, we can achieve climate neutrality by 2050.

This study’s contribution to the scientific community is the Portuguese and European legislation analysis regarding soil threats identified in the SoiLEX database, which was not used before in a soil legislation analysis. It allowed for the identification of indirect references to soil threats, providing an opportunity to increase the visibility of these threats in the potential adaptation and adjustment of Portuguese and European legislation to the new Soil Monitoring and Resilience Directive.

Future studies could focus on analysing legislation following the transposition of the new monitoring and resilience directive, to verify positive changes in soil protection and health within the legislation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

References

- Adhikari, K., & Hartemink, A. E. (2016). Linking soils to ecosystem services—A global review. Geoderma, 262, 101-111.

- Blum, W. E. (2005). Functions of soil for society and the environment. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology, 4, 75-79. [CrossRef]

- Blum, W. E., & Swaran, H. (2004). Soils for sustaining global food production. Journal of food science, 69(2), crh37-crh42.

- Bouma, J., Broll, G., Crane, T. A., Dewitte, O., Gardi, C., Schulte, R. P., & Towers, W. (2012). Soil information in support of policy making and awareness raising. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 4(5), 552-558.

- Castelo-Grande, T., Augusto, P. A., Fiúza, A., & Barbosa, D. (2018). Strengths and weaknesses of European soil legislations: The case study of Portugal. Environmental Science & Policy, 79, 66-93.

- Council of European Union (2025), Press Release: “Council adopts new rules for healthier and more resilient European soils”-https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2025/09/29/council-adopts-new-rules-for-healthier-and-more-resilient-european-soils/, consulted on 29/10/2025.

- Decreto-Lei117/2024-https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/117-2024-901535572- consulted on 23/01/2025.

- Direção Geral de Agricultura e Desenvolvimento Rural (DGADR), (2025) - “Soils for Europe” event: DGADR presents activities and projects under development in the field of soil health in Brussels.”-https://www.dgadr.gov.pt/pt/destaques/1214-evento-solos-para-a-europa-dgadr-apresenta-em-bruxelas-atividades-e-projetos-em-desenvolvimento-no-ambito-da-saude-do-solo?, consulted on 31/10/2025.

- Direção Geral Território (DGT), (2025) -UnSealingCities –“Planning interventions to mitigate the impacts of soil sealing and adapt to climate change in urban areas” , consulted on 31/10/2025.

- European Environmental Bureau, (EEB) (2025) – SOIL-European Parliament seals the deal of first-ever EU law on soils- https://eeb.org/european-parliament-seals-the-deal-of-first-ever-eu-law-on-soils/ consulted on 29/10/2025.

- European Commission (2019)- COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE EUROPEAN COUNCIL, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS The European Green Deal.

- European Commission. (2023). Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on Soil Monitoring and Resilience (Soil Monitoring Law). COM (2023), 416.

- European Commission (2021)- EU Soil Strategy for 2030 Reaping the Benefits of Healthy Soils for People, Food, Nature and Climate.

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2015)- Revised World Soil Charter.

- FAO (2017) -Voluntary guidelines for sustainable soil management. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome, Italy, 26.

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO)(2022) -The Global Soil Partnership Action Framework 2022-2030 (GSP).

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, (FAO) (2025b)- FAO SOILS PORTAL consulted in 21/01/2025 Country/Territory Profiles | FAO SOILS PORTAL | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, (FAO) (2025a)- FAO SOILS PORTAL consulted 5 SoiLEX | FAO SOILS PORTAL | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Glæsner, N., Helming, K., & De Vries, W. (2014). Do current European policies prevent soil threats and support soil functions? Sustainability, 6(12), 9538-9563.

- Hannam, I., & Boer, B. (2004). Drafting legislation for sustainable soils: a guide (No. 52). IUCN.

- Heuser, I. (2022). Soil governance in current European Union law and in the European green Deal. Soil Security, 6, 100053. [CrossRef]

- Helming, K., Daedlow, K., Hansjürgens, B., & Koellner, T. (2018). Assessment and governance of sustainable soil management. Sustainability, 10(12), 4432.

- Joyalata Laishram, J. L., Saxena, K. G., Maikhuri, R. K., & Rao, K. S. (2012). Soil quality and soil health: a review.

- Juerges, N., & Hansjürgens, B. (2018). Soil governance in the transition towards a sustainable bioeconomy–A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 170, 1628-1639.

- Kibblewhite, M. G., Miko, L., & Montanarella, L. (2012). Legal frameworks for soil protection: Current development and technical information requirements. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 4(5), 573-577.

- Leal Filho, W., Nagy, G. J., Setti, A. F. F., Sharifi, A., Donkor, F. K., Batista, K., & Djekic, I. (2023). Handling the impacts of climate change on soil biodiversity. Science of The Total Environment, 869, 161671. [PubMed]

- Martinho, V. J. P. D., Ferreira, A. J. D., Cunha, C., da Silva Pereira, J. L., Carreira, M. D. C. S., Castanheira, N. L., & Ramos, T. C. B. (2024). Soil legislation and policies: Bibliometric analysis, systematic review and quantitative approaches with an emphasis on the specific cases of the European Union and Portugal. Heliyon.

- Paleari, S. (2017). Is the European Union protecting soil? A critical analysis of Community environmental policy and law. Land use policy, 64, 163-173. [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P., Jones, A., Lugato, E., & Ballabio, C. (2025). A Soil Monitoring Law for Europe. Global Challenges, 9(3), 2400336.

- Posthumus, H., & Morris, J. (2010). Implications of CAP reform for land management and runoff control in England and Wales. Land Use Policy, 27(1), 42-50.

- Posthumus, H., Deeks, L. K., Fenn, I., & Rickson, R. J. (2011). Soil conservation in two English catchments: linking soil management with policies. Land degradation & development, 22(1), 97-110.

- Prager, K., Schuler, J., Helming, K., Zander, P., Ratinger, T., Hagedorn, K., 2011. Soil degradation, farming practices, institutions and policy responses: an analytical framework. Land Degrad. Dev. 22 (1), 32e46.

- Ronchi, S., Salata, S., Arcidiacono, A., Piroli, E., & Montanarella, L. (2019). Policy instruments for soil protection among the EU member states: A comparative analysis. Land use policy, 82, 763-780.

- Rodrigues, S. M., Pereira, M. E., da Silva, E. F., Hursthouse, A. S., & Duarte, A. C. (2009). A review of regulatory decisions for environmental protection: Part II—The case-study of contaminated land management in Portugal. Environment international, 35(1), 214-225. [PubMed]

- UN, (2015)- Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

- Schoonover, J. E., & Crim, J. F. (2015). An introduction to soil concepts and the role of soils in watershed management. Journal of Contemporary Water Research & Education, 154(1), 21-47.

- Stankovics, P., Tóth, G., & Tóth, Z. (2018). Identifying gaps between the legislative tools of soil protection in the EU member states for a common European soil protection legislation. Sustainability, 10(8), 2886.

- Vieira, D. C. S., Yunta, F., Baragaño, D., Evrard, O., Reiff, T., Silva, V., ... & Wojda, P. (2024). Soil pollution in the European Union–An outlook. Environmental Science & Policy, 161, 103876.

- Vrebos, D., Bampa, F., Creamer, R. E., Gardi, C., Ghaley, B. B., Jones, A., ... & Meire, P. (2017). The impact of policy instruments on soil multifunctionality in the European Union. Sustainability, 9(3), 407.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).