1. Introduction

The inclusion of fibre-degrading enzymes in the ruminant feed can potentially improve residual fibre digestibility and feed utilisation rate. However, the varying pH levels throughout the ruminant digestive tract from alkaline in the mouth, to mildly acidic or neutral in the reticulorumen and omasum, to highly acidic in the abomasum, and then back to alkaline in the small intestine pose a significant challenge to maintaining the enzymes in their active form during delivery. In addition, the rumen's complex microbiome and the enzymes secreted by these microbes can cause the denaturation and inactivation of the fibre-degrading enzymes (Almassri et al., 2024). Microencapsulation can help deliver sensitive materials such as nutrients and enzymes to various locations in the GIT of ruminants (Almassri et al., 2024) preserving their activity, and enabling controlled release (Bartosz and Irene, 2016).

In recent years, there has been an increasing interest in utilizing polymer-based capsules derived from natural sources. Alginate capsules offer selective retention and controlled release properties, making them highly suitable carriers for various biotechnology applications (Morales et al., 2017). Alginate beads are frequently used in the encapsulation process as an entrapment matrix for enzymes and cells as they have the following advantages: (i) they are nontoxic, (ii) are low cost, (iii) resistant to microbial attack, (iv) easy to formulate, and (v) encapsulation is carried out under mild conditions (Ben Messaoud et al., 2016, Quiroga et al., 2011). In addition, acid sensitive enzymes entrapped in the beads are protected from stomach acidity and gastric juice (Quiroga et al., 2011). On the other hand, alginate beads have significant limitations, including wide pore size, considerable enzyme leakage, low mechanical strength, low encapsulation efficiency and the gel formed is susceptible to high pH levels which can affect both the release and protection of the encapsulated material (Morales et al., 2017, Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016). In addition, chelating agents like lactates, citrates, and phosphates can destabilize this network (Siang et al., 2019). Therefore, it has been proposed that coating alginate beads with additional wall materials such as chitosan could decrease the porosity of the alginate matrix, enhancing its structural integrity and preventing enzyme leakage (Anjani, 2007, Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016, Segale et al., 2016).

Chitosan, a β-1,4 linked linear polymer of 2-acetamide-2-deoxy-β-D-glucose, is a natural polymer that is non-toxic, biodegradable, and biocompatible. It has a broad range of applications, including in biomedicine, membranes, drug delivery systems, hydrogels, water treatment, and food packaging (Segale et al., 2016, Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016). The cross-linking of alginate and chitosan in hydrogels creates materials with enhanced stability compared to those obtained with a single polymer, making them suitable for medical and pharmaceutical applications. In recent years, alginate-chitosan polyelectrolyte complexes have attracted considerable attention in controlled drug delivery. These complexes are formed through ionic interactions between the carboxyl groups of alginate and the amino groups of chitosan.

In this study, we assessed the feasibility of using alginate-based beads for the microencapsulation of enzymes aimed at protected delivery to the ruminant hindgut, with beta-glucosidase selected as a model enzyme. We hypothesized that the incorporation of chitosan into the bead formulation would address some of the limitations of traditional alginate-based systems. Previous studies have shown that chitosan can improve encapsulation efficiency and protect enzymes from environmental stressors (Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016, Anjani, 2007), while the addition of carbohydrates such as sucrose and maltodextrin would enhance enzyme stability during the drying process (Corrales Ureña et al., 2016). Therefore, we evaluated the impact of these components on the encapsulation efficiency and stability of beta-glucosidase, which is involved in the hydrolysis of cellulosic fibres in the ruminant hindgut. To date, no studies have explored the use of alginate beads for enzyme delivery to the ruminant hindgut. This study addresses this gap by investigating the potential of alginate-based beads for enzyme delivery specifically to the ruminant hindgut.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

β-Glucosidase (Agrobacterium sp.) was purchased from Neogen Australasia Pty Limited (Australia), P-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (PNPG), Chitosan, CaCl2, Citric acid trisodium salt (≥98%) and p-nitrophenol were purchased from Sigma (Australia). Shellac (Swanlac ASL 10) was supplied by A.F. Suter & Company Ltd, (Germany). Sodium alginate (E401) and maltodextrin (DE18) were purchased from The Melbourne Food Depot (Victoria, Australia), and sucrose from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Australia). Tween 20 was purchased from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium), and sodium alginate (Protanal SF120RB, MW 190.6 kD) from FMC Biopolymer (NSW, Australia).

2.2. Enzyme Activity Assay

The enzyme activity was assayed following the method of Terefe et al. (2013) with some modifications. The reaction mixture consisted of 200µl of 0.2 unit/ml of β-glucosidase in HEPES buffer (pH 6.8), 500 µl of HEPES buffer (pH 6.8), and 200 µl of 0.35 mM p-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (PNPG) solution in HEPES buffer (pH 6.8). At 40 °C, the reaction mixture was incubated for 15 min, followed by boiling for 4 minutes to inactivate the enzyme and cooling in ice-water for 10 seconds. Subsequently, 100 μl of 0.18 M Na2CO3 was added to the reaction mixture to stop the reaction and develop the colour, and the absorbance at 405 nm was measured using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (UV-1700, Shimadzu, Japan). A standard curve was used to determine the concentration of the reaction product, p-nitrophenol, from the absorbance data and the activity of the enzyme was expressed as µmole of p-nitrophenol produced per min under the reaction condition.

2.3. Preparation of Encapsulation Solution

A 1% sodium alginate solution was prepared by mixing alginate powder with distilled water while stirring at 500 rpm overnight at 4℃ using a magnetic stirrer. The solution was then refrigerated for 24 hours to enable hydration and to remove any air bubbles that were introduced during agitation (Partovinia and Vatankhah, 2019). All polymer solutions were prepared 24 hours prior to their use. Fifty microliters of the enzyme were diluted in 100 mL of HEPES buffer solution to achieve a final concentration of 0.2 U/mL. Ten mL of the diluted β-glucosidase solution was then mixed with 40 mL of the alginate solution (1%) under constant stirring. The 50 mL alginate-β-glucosidase mixture was transferred into the feeding bottle, and the capsules were formed as described in section 2.4.

2.4. Production of Alginate Beads Using B-390 Encapsulator

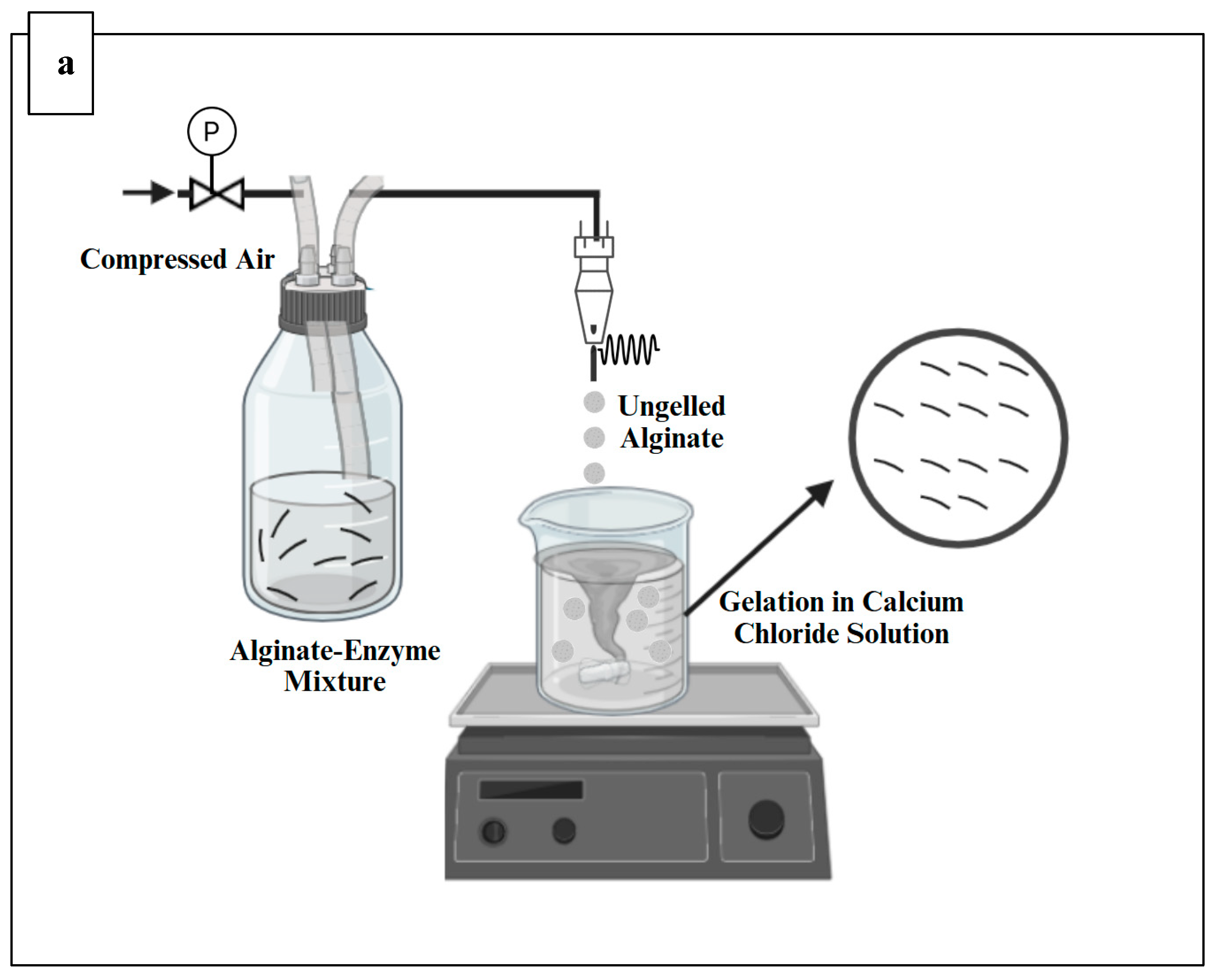

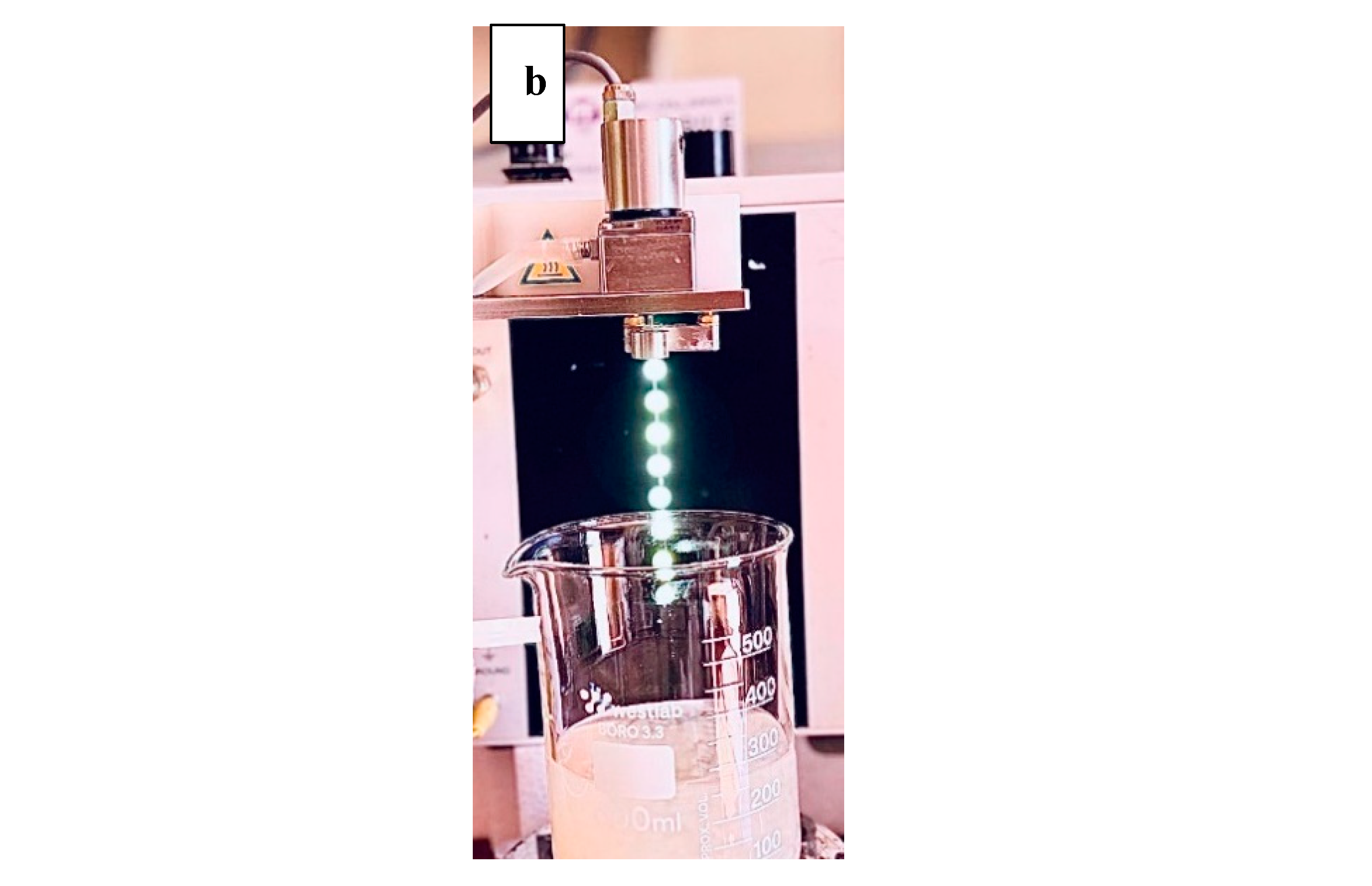

Alginate microbeads were produced using Buchi encapsulator B-390 (Buchi, Switzerland) (

Figure 1), which was equipped with a 750µm nozzle as described by Siang et al. (2019) with some modifications. The alginate-enzyme mixture in the feeding bottle was pumped into the encapsulator and extruded through a 750 µm nozzle to form small droplets. The external pressurized air supply was activated to pressurize the feeding bottle, with the pressure set to 530 mbar. A vibrational frequency of 40 Hz was applied during the pumping of the alginate-enzyme mixture to create microcapsules by atomizing the jet into uniformly sized droplets. The droplets were collected in a 0.1M calcium chloride solution and allowed to harden for 30 minutes. After this gelation period, the formed capsules were washed with MilliQ water using a filter bag to remove any excess calcium chloride solution from their surfaces before collection (Kailasapathy et al., 2006, Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016). This was followed by drying the beads at room temperature for 24 hours and storage at 4 °C until further analysis (Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016).

2.5. Determination of Encapsulation Efficiency (EE%)

The encapsulated enzyme was released by dissolving weighted beads in a trisodium citrate solution (0.2M, pH 8.2). The resulting mixture was subsequently analyzed to determine the enzyme activity recovered from the beads (Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016, Anjani, 2007) using the assay described earlier. The encapsulation efficiency was determined by calculating the activity of the encapsulated β-glucosidase, enzyme activity recovered from the beads, and expressing it as a percentage of the initial β-glucosidase activity in the alginate-enzyme mixture as described in Equation (1) (Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016). Experiments were performed at least in triplicate, and the results were averaged.

Where the initial enzyme activity is that in the alginate-enzyme and alginate-copolymer-enzyme solution

2.6. Incorporation of Polymers and Carbohydrate Stabilisers

The porous nature of alginate capsules highlighted the need for optimization of the encapsulation process and encapsulant formulations (materials). To enhance the encapsulation efficiency, a modified approach was employed by introducing chitosan into the crosslinking solution (CaCl2). The method for preparing calcium alginate-chitosan beads was adapted from Anjani (2007) and Thu and Krasaekoopt (2016) with some modifications. 5 mL of acetic acid was added to 1 g of low-molecular-weight chitosan, and the mixture was diluted with deionized water to a total volume of 700 mL. Subsequently, CaCl2 solution (0.1 M) and Tween 20 (0.1%) were added to the chitosan solution. The final volume was then made up to 1000 mL with deionized water, yielding a chitosan solution at a concentration of 0.1% (w/v) in 0.1 M CaCl₂ with 0.1% Tween 20. Tween 20 was used to reduce the surface tension of the gelling water to facilitate the formation of spherical beads (Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016).

To further improve the encapsulation efficiency of the enzyme within the alginate matrix, a combination of 2% maltodextrin (DE-18) and 4% sucrose was incorporated into the alginate-enzyme solution. The addition of these stabilizing agents is expected to enhance encapsulation efficiency by providing a protective environment that reduces protein denaturation during the encapsulation process (Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016, Farhadian et al., 2018) . To evaluate alternative formulations, the impact of incorporating 4% sucrose into the alginate-enzyme solution was assessed. In a separate formulation, 4% pectin was added to the alginate-enzyme mixture producing alginate pectinate beads (APB). These variations were aimed at optimizing the conditions for achieving maximum enzyme stability and encapsulation efficiency.

2.7. In Vitro rumen Fermentation to Assess the Stability of the Encapsulated Enzyme

2.7.1. Preparation of Microencapsulated Enzyme Samples

In this study, two types of alginate beads encapsulating the enzyme were prepared; low and high-viscosity alginate to study the effect of alginate viscosity on enzyme protection. A 2% solution of low-viscosity alginate and a 1% solution of high-viscosity alginate were prepared by mixing alginate powder with distilled water under agitation at 500 rpm overnight using a magnetic stirrer. To each solution, maltodextrin (DE-18), sucrose, and an enzyme solution were added to obtain total solids of 2% and 4% respectively for high (HVAB) and low viscosity beads (LVAB), and 0.2 U/mL enzyme concentration. For crosslinking, a solution containing 0.1 M CaCl₂, 0.1% chitosan, and 0.1% Tween 20 was used. The beads were prepared as described in section 2.4. Control beads without enzyme were also produced in the same way to serve as blanks for measuring the enzyme activity referred to as LVABc and HVABc.

2.7.2. Collection and Pre-Incubation of Rumen Fluid

Five hundred millilitres of rumen fluid were collected per run from late-lactation cannulated Holstein Friesian dairy cows, aged 4, 5, and 7 years, at Agriculture Victoria (Ellinbank, Victoria) in the morning before feeding and transported to the laboratory as described by (Tunkala et al., 2022, Tunkala et al., 2023b). Cows were grazing a solvent-extracted canola meal, and wheat and barley grain mix (6.1 kg dry matter (DM) per day per cow) that was supplied in the milking parlor. The rumen fluid was transported to the laboratory in a pre-warmed 0.5 L bottle placed in an incubator (Galaxy 14 S, New Brunswick Scientific, Eppendorf) set to 39 °C. The bottles were sealed with a one-way gas valve to permit the release of generated gas. Upon arrival at the laboratory, the rumen fluid was filtered through two layers of cheesecloth to separate the liquid from the residual solids. The liquid fraction was subsequently transferred to a pre-warmed 0.5 L bottle and utilized as fresh rumen fluid (RF) for incubation on the day of collection.

2.7.3. Fermentation and Experimental Design

Using the method of Tunkala et al. (2023b) with some modifications, the pre-incubated rumen fluid was mixed with McDougall's buffer 'synthetic saliva' (pH 6.8±0.1) to obtain a buffered rumen fluid with a 1:3 rumen fluid to buffer ratio. The feed sample, Oaten Chaff, (Petstock, Australia) were ground using a domestic grinder (Breville, Australia) and sieved by a 1mm size sieve. A filter bag with a pore size of 25 µm (F57 ANKOM bag, ANKOM Technology, Macedon, NY, USA) was utilized to measure the dry matter disappearance (DMD) of the incubated sample (Tunkala et al., 2022, Tunkala et al., 2023a). For Rumen fluid analysis on DMD and encapsulation efficiency, heat-sealed F57 filter bags were prepared with each bag containing one gram of either LVAB or HVAB. Control filter bags containing one gram of LVABc or HVABc were similarly prepared. These filter bags were then incubated in triplicate in 250 mL glass bottles with 1 gram of feed sample (Oaten Chaff) and 100 mL buffered rumen fluid for 24 h in water bath maintained at 39°C and 50 rpm (Julabo, SW23, John Morris Scientific, NSW, Australia) (Tunkala et al., 2022, Tunkala et al., 2023a). For buffer analysis on DMD and encapsulation efficiency, one gram of LVAB and one gram of LVABc were placed in heat-sealed F57 filter bags. These bags were incubated in triplicate in 250 mL glass bottles with 1 gram of feed sample (Oaten Chaff) and 100 mL of MacDougall Buffer for 24 h in a 39⁰C/50rpm water bath. For background analysis, one gram of feed sample was weighed in 250 mL glass bottles, with 100 mL buffered rumen fluid dispensed to the bottles using a liquid dispenser and incubated in triplicate for 24 h in a 39⁰C/50rpm water bath. All glass bottles were purged with CO

2 prior to incubation, and the tube was subsequently sealed with a rubber bung (Tunkala et al., 2022, Tilley and Terry, 1963). After 24 hours of incubation, the filter bags were gently rinsed with distilled water using a plastic water diffuser (tattoo squeeze). The swollen beads were weighed immediately after the removal of the adhering liquid. The swelling rate of the beads was calculated using Equation (2) (Tunkala et al., 2023a).

Where Wt is the weight of swollen beads at time t, and Wo is the initial weight of the beads.

The residue was dried in a fume hood at room temperature for 24 hours. The samples were weighed to determine the remaining dry matter, which was calculated from the initial weight using Equation (3) (Tunkala et al., 2022, Kim et al., 2015).

where W1 is the initial dry weight (g) of the beads before ruminal incubation, and W2 is the weight (g) of the final air-dried beads after ruminal incubation.

The pH value of the buffered rumen fluid was measured pre and post-fermentation using a pH meter (WP-81, TPS). Enzyme recovery was evaluated as illustrated in Equation (4). To evaluate enzyme recovery pre and post-ruminal incubation, weighted beads were dissolved in a trisodium citrate solution (0.2M, pH 8.2). This dissolved mixture was analysed for enzyme activity using enzyme assay as previously described (Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016, Anjani, 2007).

Where E0 is the enzyme activity before ruminal incubation, and E1 is the enzyme activity after ruminal incubation.

2.7.4. Dimensional and Morphological Characterization of hydrogel microbeads

To examine the structure of the microcapsules, the samples were mounted on aluminium stubs using double-sided conductive carbon tabs. These samples were then coated with iridium using a Cressington 208HRD sputter coater, achieving a coating thickness of approximately 6 nm (60 mA for 60 seconds). Conductive coating is essential to prevent charge accumulation in an electron microscope, ensuring clear images, particularly for insulating materials (Shaibani et al., 2020, Gunawardana et al., 2023). The samples were imaged using a Zeiss Sigma VP300 FESEM (Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope). Images were captured in secondary electron (SE) mode, which highlights topographical features and were processed using Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) software (AZTEC, produced by Oxford Instruments Pty Ltd) (Shaibani et al., 2020). An accelerating voltage of 5 kV was utilized for imaging, and the magnifications correspond to the scale bars indicated in the images.

2.7.5. Stability of Encapsulated Enzyme in the Beads

Encapsulated enzymes were kept at 4 °C for 14 weeks (Anjani, 2007). The beads were weighted and disrupted using trisodium citrate solution (0.2M, pH 8.2) (Azarnia et al., 2008, Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016) at 4 °C while shaking at 100 rpm for 24 hours to release the encapsulated enzyme. The samples were then analyzed for enzyme activity retained over the 14-week storage period as previously described (Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using OriginPro 2019 software. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out, followed by Tukey’s test to assess differences between the mean values at a 95% confidence level (p < 0.05) for all tests.

3. Results and Discussion

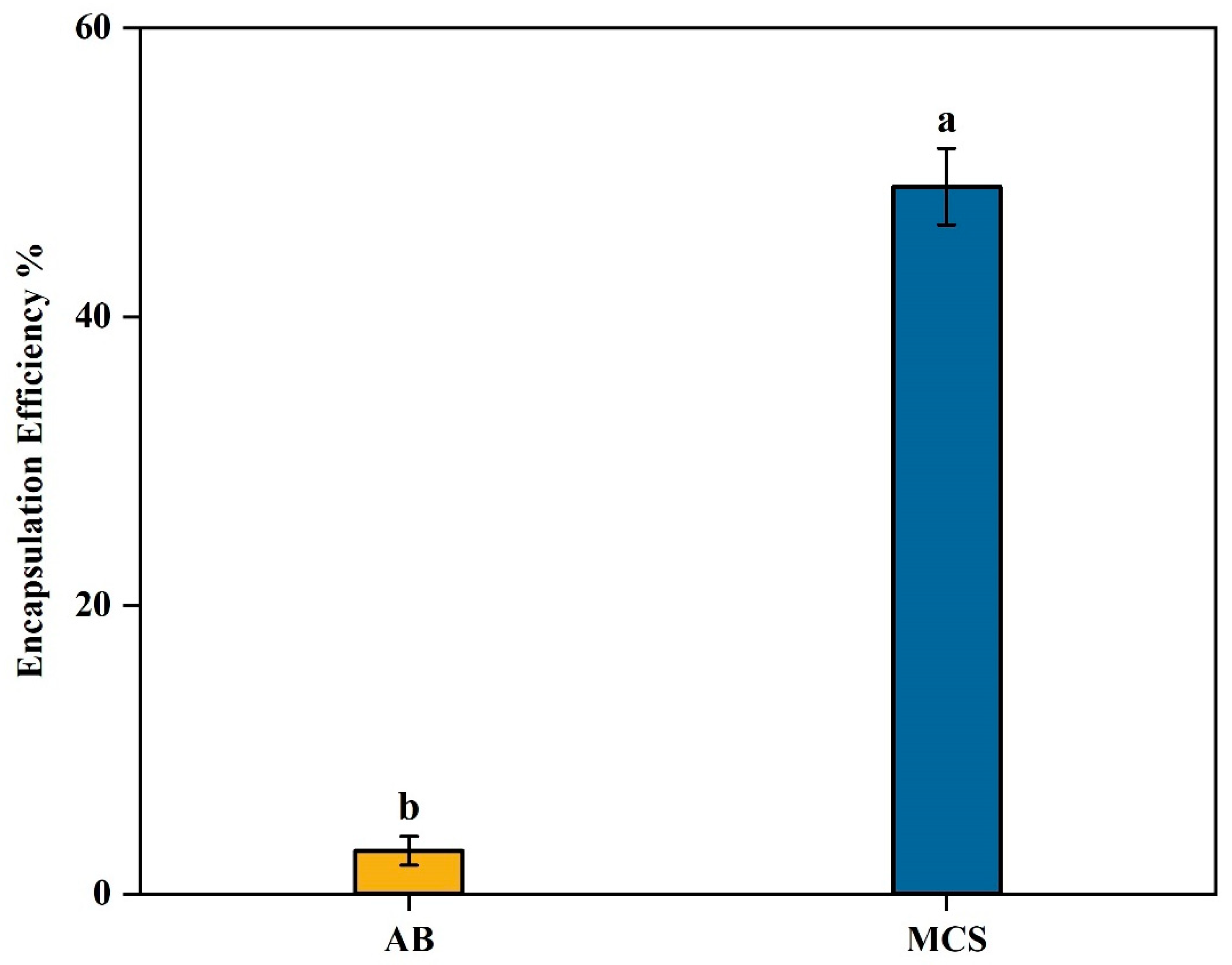

3.2. Encapsulation Efficiency

The encapsulation efficiency (EE) of β-glucosidase in alginate beads was around 3% (Figure 4). The low encapsulation efficiency (EE) could be attributed to the leakage of β-glucosidase from the capsules during encapsulation. Due to the porous structure of the alginate capsules, a significant portion of the entrapped enzyme may have been released (Kailasapathy et al., 2006, Anjani, 2007). This loss could be attributed to the diffusion of β-glucosidase into the gelling cationic solution during gel bead formation, a process known as syneresis. Since β-glucosidase is water-soluble, it may migrate out of the alginate matrix and into the surrounding solution, leading to reduced enzyme retention within the gel beads (Anjani, 2007). We modified the crosslinking cationic solution (MCS) in an attempt to enhance EE. Addition of 0.1% chitosan to the cationic solution of 0.1M CaCl

2 significantly increased (

p < 0.05) the EE from 3% to 49% as shown in

Figure 2. Similarly, Anjani (2007) stated that the encapsulation of flavourzyme significantly increased from 16% to 72% when 0.1% chitosan was added to the cationic solution. Another study by Thu and Krasaekoopt (2016) found that adding 0.2% chitosan to the cationic solution resulted in the lowest protease leakage (8.1%). These findings highlight the effectiveness of chitosan in enhancing the retention properties of alginate microcapsules. Chitosan, like CaCl

2, interacts with alginate as a cation binding to an anion. However, due to its larger molecular size, chitosan is more effective at blocking the pores in the alginate matrix when combined with CaCl

2, offering better pore-blocking efficiency than CaCl

2 alone. As a result, the structure of the alginate gel shifts from macroporous to microporous (Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016), which minimizes enzyme loss. Chitosan may also enhance the thickness of the gel membrane through crosslinking between its amine groups and the carboxyl groups of alginate (Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016). Moreover, low molecular weight chitosan readily diffuses into the alginate gel matrix (Krasaekoopt et al., 2003, Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016), leading to a reduction in pore size and an enhancement in membrane thickness within the calcium alginate-chitosan beads. Therefore, the treatment with chitosan effectively reduced the pore size of alginate, subsequently minimizing enzyme leakage resulting in improved encapsulation efficiency.

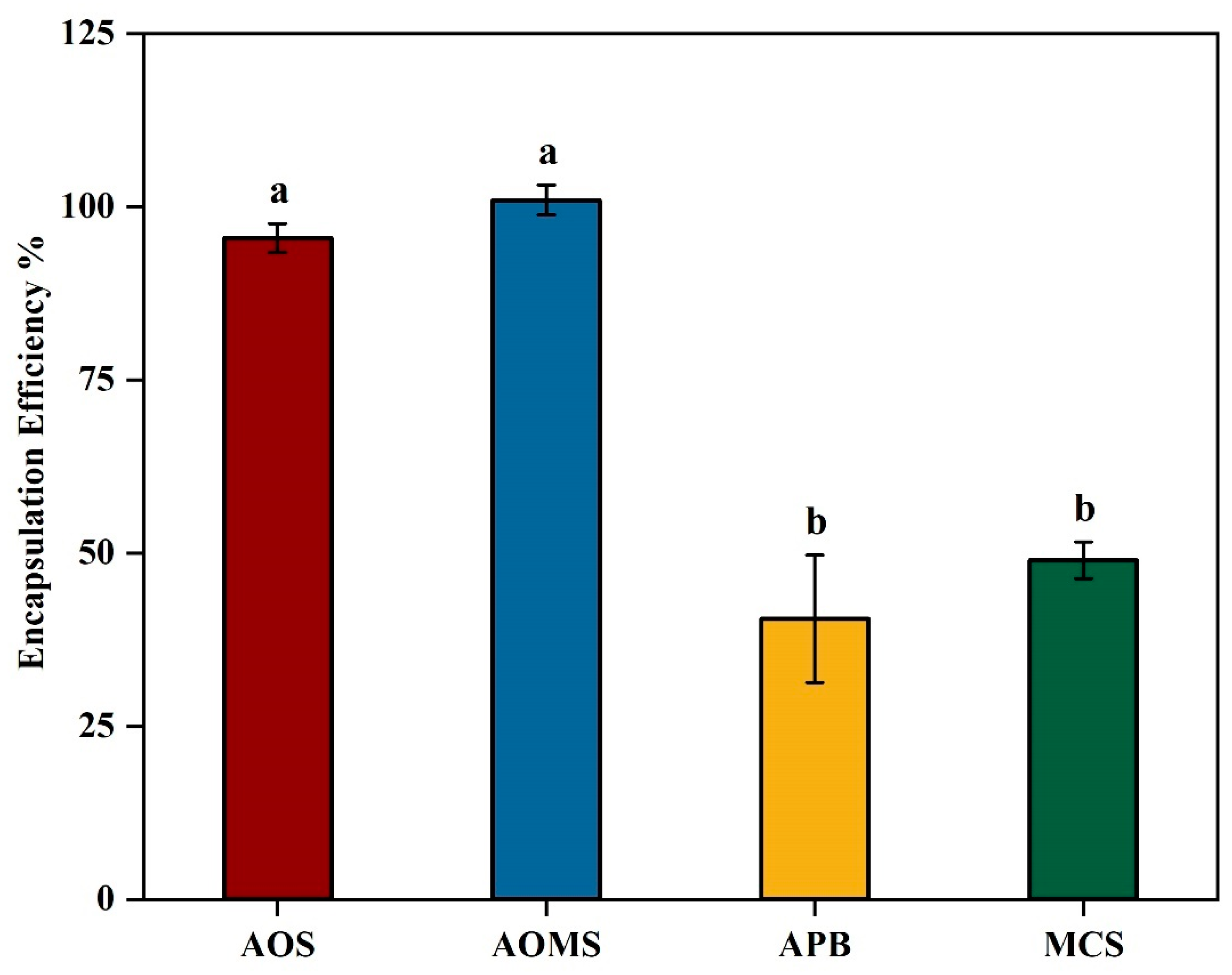

Further improvement in the encapsulation efficiency of β-glucosidase was achieved through the incorporation of carbohydrate stabilizers (

Figure 3). The control formulation (MCS) included a solution containing 1% (w/v) alginate was studied for encapsulating β-glucosidase as described in 2.3 by gelling for 30 min in 0.1M CaCl

2 containing 0.1% (w/v) chitosan and 0.1% (w/v) tween 20, providing a baseline encapsulation efficiency. Three different formulations were evaluated by adding: (i) 4% sucrose (AOS), (ii) 4% sucrose and 2% maltodextrin mixture (AOMS), and (iii) 4% pectin (APB) to the base formulation (MCS). The encapsulation efficiency (EE) data revealed significant differences (p<0.05) among the formulations, as confirmed by one-way ANOVA analysis. These differences can be explained by the distinct properties of the added components. The significant increase (

P < 0.05) in EE from 49% to 95.5% in AOS can be attributed to its role as a stabilizing and cryoprotective agent. Sucrose helps to preserve the structural integrity of the encapsulated enzyme by reducing the stress associated with drying and bead formation processes. Sucrose stabilizes proteins by preventing denaturation and aggregation during encapsulation, as it forms hydrogen bonds with proteins, protecting their structure in solution (Farhadian et al., 2018). Additionally, sucrose increases the viscosity of the solution, which may improve the bead formation process by creating a more uniform and stable matrix (Stojanovic et al., 2012). In a study by Zhang et al. (2021), sucrose, as a filler material, improved structural integrity and encapsulation efficiency within calcium alginate matrices. Moreover, sucrose protects against environmental stresses such as dehydration and temperature fluctuations during encapsulation, aiding in enzyme retention within the beads. Trivedi et al. (2006) demonstrated that adding sucrose at a concentration five times the enzyme’s weight increased residual activity and protein loading in immobilization processes. The stabilizing effect of sucrose likely helped preserve the enzyme's structure under gas-phase conditions, protecting it from denaturation due to heat or dehydration during the reaction. This suggests that sucrose plays a crucial role in maintaining enzyme stability and bioactivity, especially under conditions involving dehydration, which aligns with its application in our study. The highest EE (100%±2.160) was achieved with incorporation of both sucrose and maltodextrin (AOMS). This could be due to maltodextrin’s additional stabilizing effects. Maltodextrin has been shown to significantly increase the encapsulation efficiency from 49% to 100% (

p < 0.05,

p=0.0001) most likely by forming a more robust bead matrix, enhancing gel strength, and reducing bead porosity (Mong Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016). Maltodextrin also has cryoprotective properties (Farhadian et al., 2018), similar to those of sucrose, which help protect the enzyme's structure during the encapsulation process by interacting with water molecules during drying or storage. Furthermore, maltodextrin in calcium alginate-maltodextrin beads enhances encapsulation efficiency by increasing the bead size and reducing enzyme leakage, which contributes to better protection of the enzymes from deactivation due to factors like pH and moisture during storage (Mong Thu and Krasaekoopt, 2016). The combined effects of sucrose and maltodextrin created a synergistic effect, improving both bead integrity and reducing the diffusion of the encapsulated enzyme. In contrast, the addition of pectin (APB) resulted in a reduction of EE from 49% to 40.5% although that was not statistically significant (

p > 0.05,

p=0.1277). This is likely due to pectin’s gelation properties which can interfere with alginate's crosslinking by calcium ions, resulting in a denser gel structure that restricts enzyme-substrate contact, lowers encapsulation efficiency, and increases enzyme leakage over time (Costa et al., 2024). Additionally, the similar negative charges of pectin and alginate may lead to competition for calcium ions, further disrupting effective crosslinking and compromising the stability of the encapsulation (Costa et al., 2024). The EE of APB is significantly lower than both AOS and AOMS (

p < 0.05), indicating that pectin compromises encapsulation efficiency compared to formulations containing sucrose or a combination of sucrose and maltodextrin. However, there was no significant difference between AOS and AOMS (

P > 0.05,

P=0.2293). The higher EE in AOS and AOMS suggests that sucrose and maltodextrin are effective at enhancing the retention of the enzyme within the alginate beads by reinforcing the bead matrix, while pectin destabilizes the structure, leading to lower encapsulation efficiency. The addition of a maltodextrin-sucrose (AOMS) mixture has been selected as the best formulation for enhanced encapsulation efficiency.

3.1. In Vitro Rumen Fermentation

After finalising the best formulation for enhanced encapsulation efficiency, two types of beads encapsulating the enzyme HVAB (with an EE of 97%) and LVAB (with an EE of 98.5%) and control beads of the same composition with no enzymes, HVABc, and LVABc were produced as explained in section 2.7.1 and incubated with buffered rumen fluid (39℃, 50 rpm, 24 h). After incubation, these beads were analysed for dry matter disappearance, enzyme recovery, and swelling ratio.

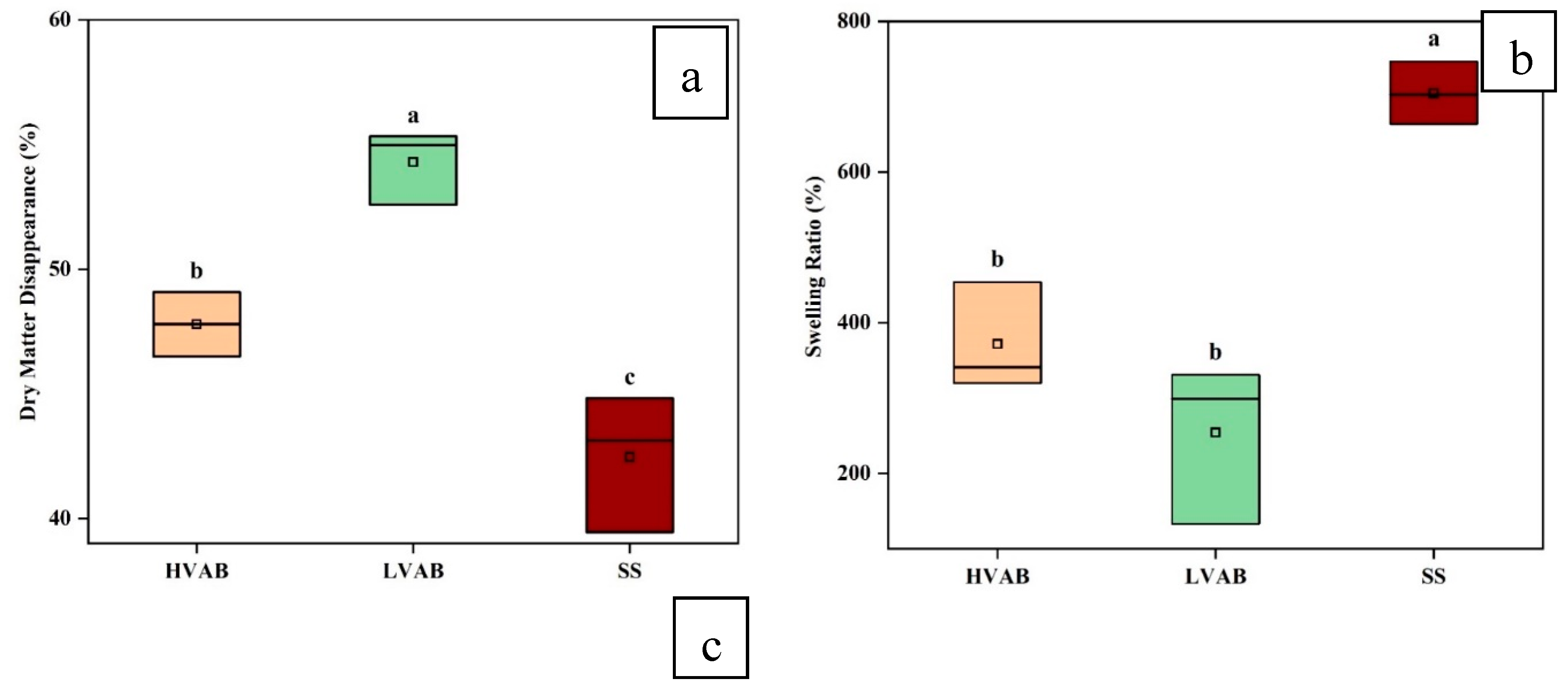

Figure 4a compares the dry matter disappearance (DMD) across three different treatments: (i) high-viscosity alginate beads incubated in buffered rumen fluid (HVAB), (ii) low-viscosity alginate beads incubated in buffered rumen fluid (LVAB), (iii) low-viscosity alginate beads incubated in buffer only, without rumen fluid (SS). LVAB showed the highest level of dry matter disappearance (around 54%, SD=1.491), followed by HVAB (approximately 48%, SD= 1.289), and SS had the lowest value (around 42%, SD= 2.750). The overall ANOVA analysis reports statistically significant differences between the groups (

p < 0.05). The Tukey test further clarifies these differences. The comparison between LVAB and HVAB shows the largest mean difference which was statistically significant (

p < 0.05), and DMD was considerably higher in LVAB compared to HVAB. Similarly, the difference between SS and LVAB was significant (

p < 0.05). Likewise, the difference in DMD between SS and HVAB was significant (

p < 0.05), and DMD was higher in both LVAB and HVAB compared to SS. These differences suggest that the viscosity of the alginate beads and the presence of rumen fluid significantly influence the extent of DMD. The lower dry matter disappearance in HVAB compared to LVAB may be attributed to the higher viscosity of the alginate beads. High-viscosity alginate beads likely provide a denser encapsulation matrix, which could reduce the diffusion of rumen microbial enzymes or fermentable substrates through the bead, thus limiting the extent of microbial degradation and fermentation. This would result in less efficient digestion of the encapsulated material. The lower DMD in the SS group, where the beads were incubated only in McDougall buffer without rumen fluid, could be due to the absence of microbial and enzymatic action from the rumen fluid contributing to the breakdown of dry matter. Overall, bead viscosity and microbial presence play some role in dry matter disappearance but substantial dry matter disappearance is observed even in the buffer indicating that other factors play important roles.

The ANOVA results presented for the swelling ratio of HVAB, LVAB, and SS show significant differences between the three groups (p<0.05) (

Figure 4b). The means for swelling ratio were 371.67% for HVAB, 254.33% for LVAB, and 704.67% for SS. HVAB, with the higher viscosity alginate beads, exhibited a greater swelling ratio (371.67%) compared to LVAB (254.33%), although the difference was not statistically significant (

p>0.05). The higher swelling ratio of HVAB could be due to the structural integrity provided by the higher viscosity formulation, which allows the beads to retain more water when incubated in rumen fluid. The lower swelling ratio in LVAB could result from the less dense network of low-viscosity alginate beads, making them less capable of absorbing and retaining water. The SS group, which is LVAB incubated without rumen fluid, showed the highest swelling ratio (704.67%) (

p<0.05). The difference in swelling ratio between the rumen groups (HVAB, LVAB) and the ones without rumen (SS) could be explained by the pH difference after incubation. The final pH in the HVAB and LVAB groups was 6.0 and 5.95, respectively, while in the SS group, it was 6.5 after 24 h incubation. The initial pH of all the samples were 6.8±0.1, but the pH of HVAB and LVAB decreased, likely due to rumen fermentation. Rumen fermentation produces volatile fatty acids, which contribute to the acidification of the environment, thus lowering the pH. This pH change is critical because alginate exhibits different swelling behaviours depending on the pH. Alginate gels swell more in higher pH environments due to the ionization of carboxylate groups in the alginate polymer, which increases electrostatic repulsion between polymer chains, thereby enhancing water absorption. In contrast, at lower pH values, fewer carboxylate groups are ionized, leading to reduced swelling capacity. In the SS group, where the pH remained higher (6.5), the alginate beads could maintain a higher degree of ionization, allowing them to swell more. In contrast, in the HVAB and LVAB groups, the lower pH (6 and 5.95) reduced the ionization of the alginate, limiting their ability to absorb water and swell. This explains the significant difference in swelling ratios between the SS group and the other two groups. These results highlight the impact the presence of rumen fluid on the swelling behaviour of alginate beads.

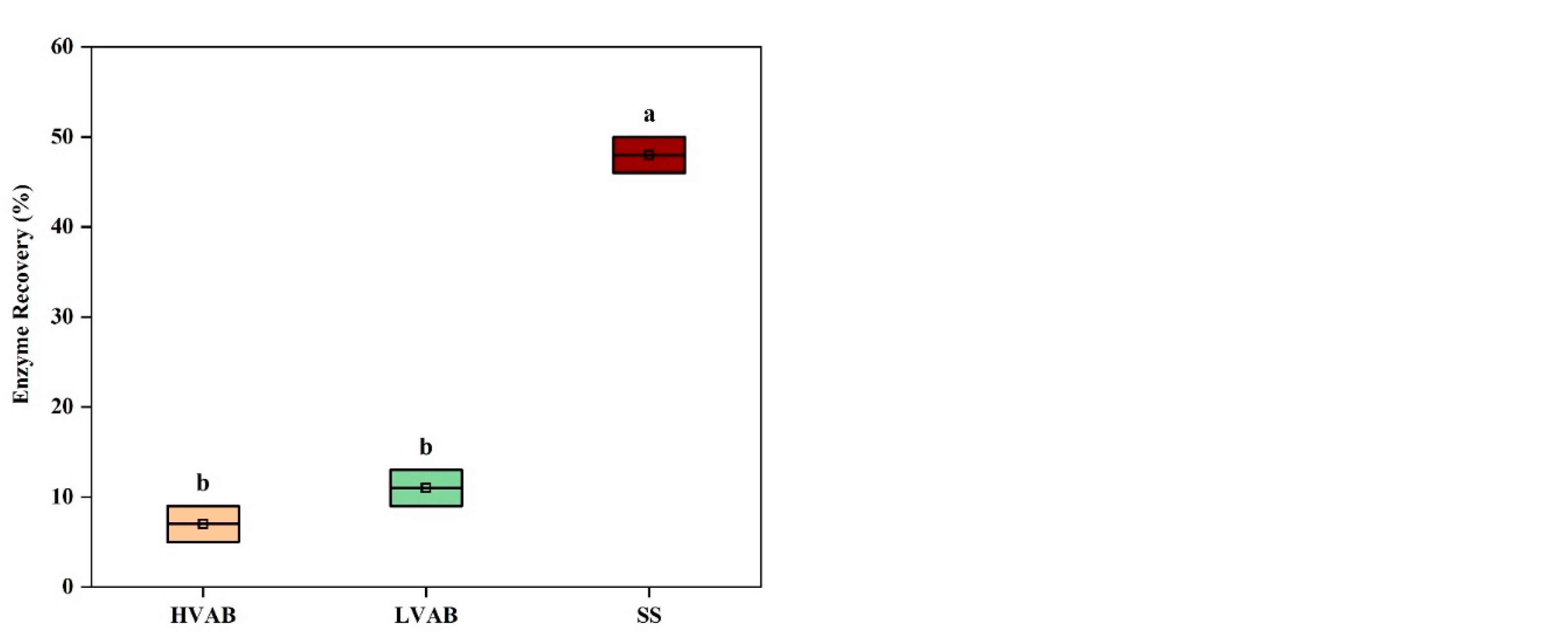

The ANOVA results for enzyme recovery after incubation show significant differences across the three treatments HVAB, LVAB, and SS (

Figure 4c). The beads incubated in buffer (SS) had the highest residual enzyme activity with an enzyme recovery (ER) of 48%, followed by LVAB (ER= 11%) and HVAB (ER= 7%). The overall ANOVA analysis indicates statistically significant differences between the groups, with

p < 0.05. The Tukey test further clarifies these differences. The comparison between SS and HVAB shows the largest mean difference with a (

p < 0.05), suggesting that enzyme recovery is substantially higher in SS compared to HVAB. Similarly, the difference between SS and LVAB is also significant (

p < 0.05). However, the difference between LVAB and HVAB was not significant (

p >0.05). The SS treatment resulted in substantially higher enzyme recovery compared to beads incubated in the rumen fluid, possibly due to the lack of microbial or enzyme activity, which could degrade the enzyme. In contrast, the lower recovery in both HVAB and LVAB, particularly HVAB, may be due to the interaction between the rumen fluid and the encapsulated enzyme, which may have led to enzyme degradation by the activity of rumen microorganisms and their enzymes. The higher viscosity in HVAB may have also restricted enzyme release to the assay matrix, which may have led to the apparently lower recovery compared to LVAB. The differences in dry matter disappearance (DMD) across the HVAB, LVAB, and SS groups provide important insights into the observed enzyme recovery patterns. The lower enzyme recovery in HVAB and LVAB, particularly in HVAB, can be partially explained by the extent of bead degradation, as indicated by DMD. In HVAB, where dry matter disappearance is around 48%, and in LVAB, where it is at approximately 54%, significant degradation of the alginate bead matrix likely occurred. This degradation would lead to the release of encapsulated enzyme into the surrounding environment. In the presence of rumen fluid (in both HVAB and LVAB), the enzyme could be exposed to degradation by rumen microorganisms and their enzymes (e.g. protease) and metabolites (e.g. short chain fatty acids, leading to a loss of enzyme activity and recovery. In contrast, the SS group, which does not contain rumen fluid, shows DMD (around 42%) and consequently higher enzyme recovery, likely due to the absence of rumen microorganisms. The high levels of DMD in both HVAB and LVAB point to the need for more robust bead formulations to prevent premature breakdown and enzyme loss. Improved formulations might include introducing more crosslinking agents or additional protective layers that could slow down degradation in the rumen environment, preserving both the bead structure and the enzyme encapsulated within. By reducing bead degradation, it would be possible to achieve higher enzyme recovery, as the enzyme would remain protected from the hostile environment of the rumen fluid. In conclusion, the current bead formulations, both HVAB and LVAB, may not be robust enough to prevent degradation and subsequent enzyme loss in the gastrointestinal tract of ruminants. This highlights the necessity for optimizing the bead matrix to protect the enzyme and maintain a more consistent and higher level of enzyme recovery.

3.3. Dimensional and Morphological Characterization of hydrogel microbeads

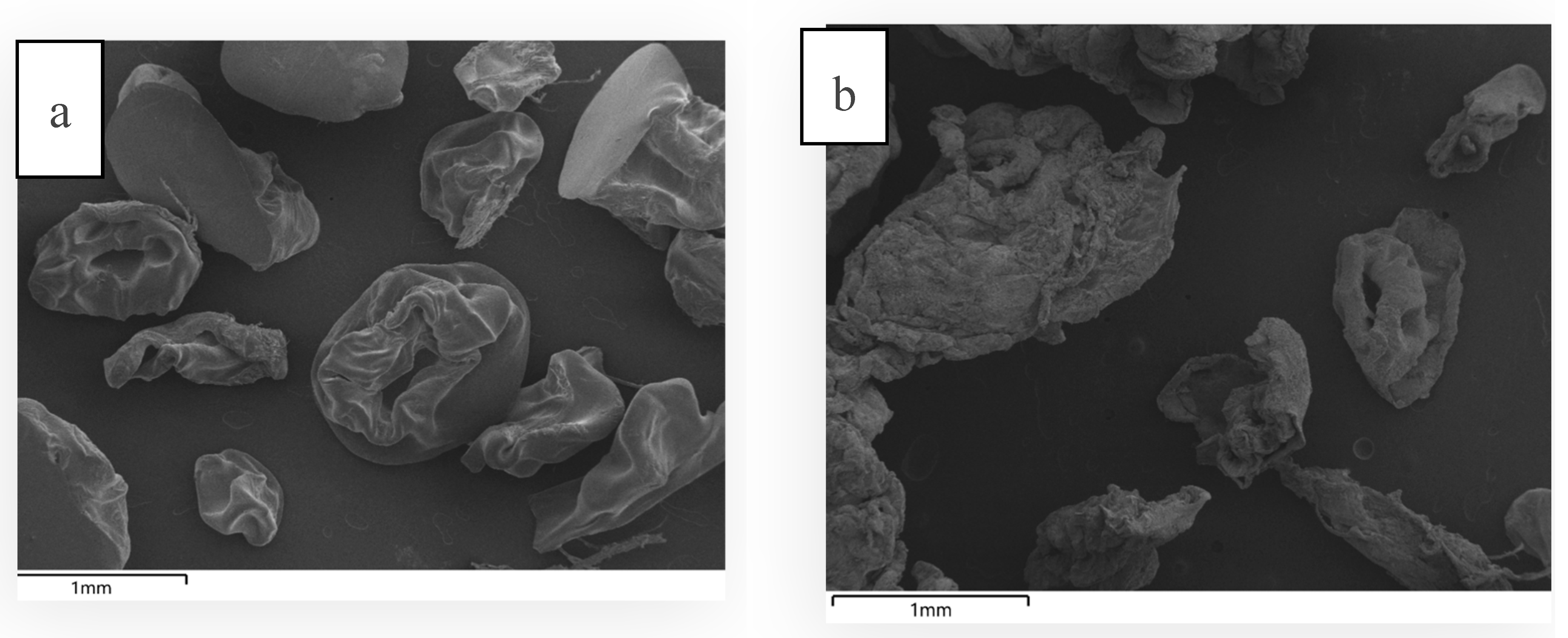

In order to determine the structural integrity of the microcapsules before and after

in vitro rumen incubation, SEM micrograph of the bead samples were taken. Before incubation, the HVAB beads appeared relatively smooth and structured, with wrinkled and slightly deformed shapes (

Figure 5a). This is likely due to the drying process, where moisture evaporates from the alginate-sucrose-maltodextrin matrix. During drying, the beads shrink, causing some collapse in structure as water is removed, which results in a wrinkled appearance. Post-rumen and buffer incubation (

Figure 5b), the beads appear disintegrated, showing a much more fragmented and porous structure. The incubation in rumen fluid at pH 6.8±0.1 (39°C, 24 h) would have exposed the beads to enzymatic and microbial activity. Alginate is typically sensitive to microbial degradation (Tang et al., 2009). The ruminal environment is rich in enzymes and microorganisms and that may partly explain the degradation of the beads after incubation. Additionally, alginate gels swell more in a higher pH environment thereby enhancing water absorption which weakens the crosslinked structure (Chuang et al., 2017). As the bead matrix was partially degraded, 83% of the encapsulated enzyme was released/inactivated. The fragmented nature of the beads suggests that the release of the enzyme could have been gradual as the matrix disintegrated.

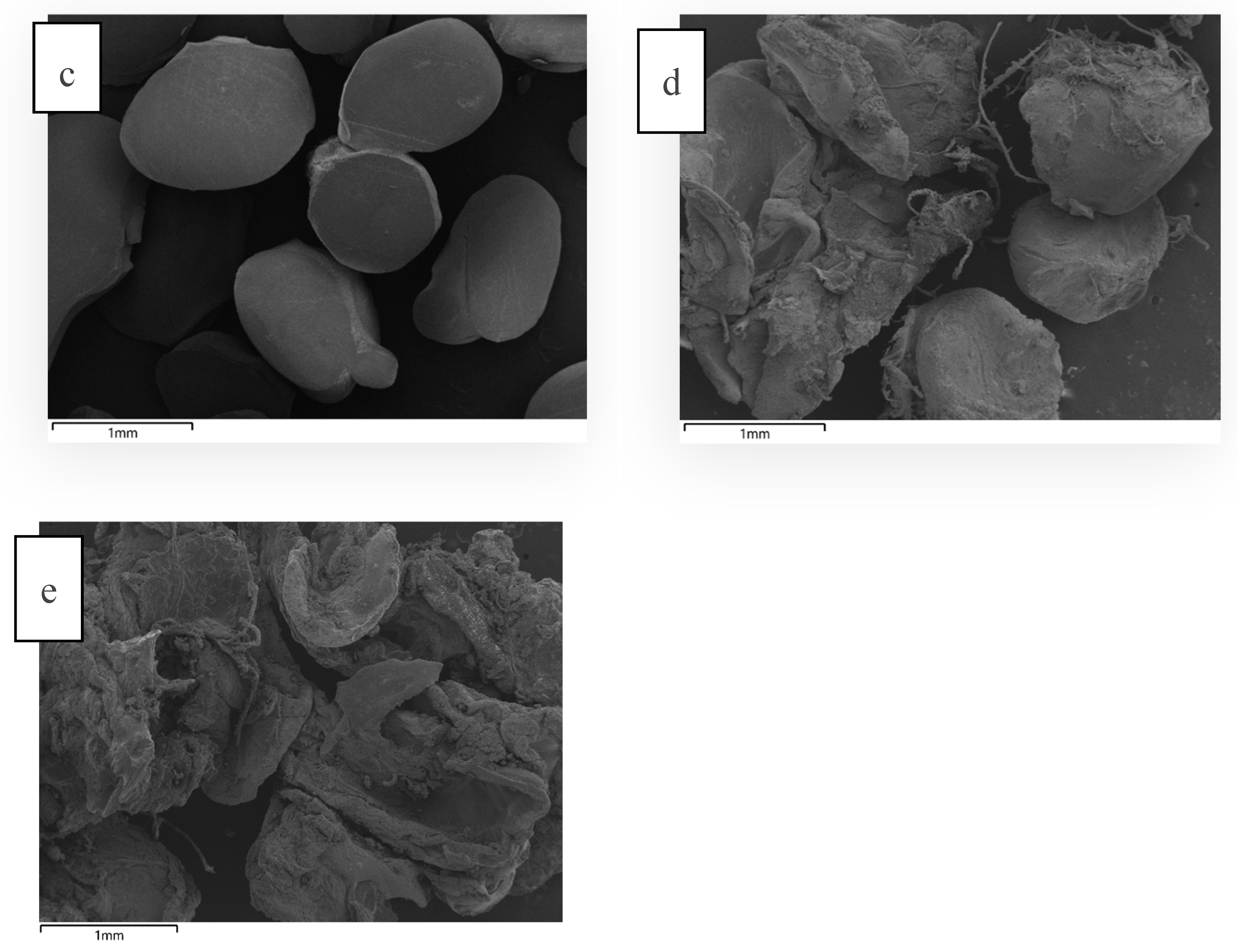

Similarly, LVAB before ruminal incubation (

Figure 5c) were compact, smooth, and well-formed due to the tight crosslinking and dehydration process. However, after ruminal incubation (

Figure 5d), the beads appear highly irregular. This external structure likely indicates significant disruption of the outer surface due to the combined effects of microbial degradation, enzymatic activity, and pH-driven swelling. The ruminal environment is harsh, with active fermentation and breakdown of the bead matrix. The outer structure might look fragmented due to continuous microbial attack and breakdown of the polysaccharide structure (alginate, sucrose, and maltodextrin). The low enzyme recovery (11%) likely resulted from microbial degradation of the beads in the rumen fluid, indicating that further formulation adjustments are needed to create more robust and resilient beads to withstand both microbial activity and environmental stresses. In contrast, the SS beads (

Figure 5e), were swollen which could be attributed to the near-neutral pH of McDougall's buffer. The absence of microbial and enzymatic degradation allows for better retention of the enzyme within the bead matrix, resulting in higher recovery (48%). However, there was a substantial loss of enzyme activity even in the buffer (62%). This suggests that additional coating is necessary to protect the beads from both pH-induced and microbial-induced breakdown in the rumen.

3.4. Stability of Encapsulated Enzymes

High-viscosity alginate beads (HVAB) and low-viscosity alginate beads (LVAB) were stored at 4°C after air-drying and the shelf-stability of the stored capsules was studied for 14 weeks by measuring the enzyme activity at the end of the storage period. The comparison of enzyme activity in high-viscosity alginate beads (HVAB) and low-viscosity alginate beads (LVAB) over an initial period and after 14 weeks of storage revealed notable differences in their performance. Initially, both bead types demonstrated similar enzyme activity, with HVAB showing 0.189±0.036 U/mL and LVAB 0.192±0.029U/mL, indicating that the encapsulation process was equally effective for both formulations at preserving enzyme functionality. After 3.5 months of storage, enzyme activity was slightly higher (p>0.05) in LVAB (0.214±0.072 U/mL) compared to HVAB (0.199±0.061 U/mL). This increase in activity may result from enzyme stabilization within the matrix, where the storage conditions allowed the enzyme to adopt a more active conformation. Additionally, gradual moisture absorption could enhance enzyme solubility and reactivity, while structural changes in the beads, such as increased porosity, might facilitate enzyme diffusion and improve activity over time. The difference between the bead types could be attributed to structural and permeability variations. High-viscosity alginate forms denser matrices, potentially limiting enzyme mobility and exchange with the surrounding environment, which might slightly impact long-term stability. On the other hand, low-viscosity alginate forms less dense matrices, potentially allowing better diffusion of the enzymes during assaying.

4. Conclusion

This study enabled successful microencapsulation of β-glucosidase enzyme in alginate beads by modifying the cationic gelling solution by adding 0.1% chitosan and incorporating sucrose and maltodextrin in the formulation resulting in 100% encapsulation efficiency. This enhancement could be attributed to the reduction in beads porosity through incorporation of chitosan and the stabilizing and cryoprotective effects of sucrose and maltodextrin, which improved bead matrix stability and enzyme retention. In vitro rumen fermentation of the beads showed relatively low recovery of enzyme activity following incubation most likely due to the challenging conditions of the rumen environment, which may have contributed to bead degradation and release and potentially inactivation of the encapsulated enzyme. This reduction in activity may also be attributed to the interaction between the rumen fluid and the encapsulated enzyme, where rumen microorganisms and their enzymes could degrade or inactivate the encapsulated enzyme. The combined effects of microbial enzymatic hydrolysis and fluctuating pH likely compromised the structural integrity of the beads, leading to enzyme leakage and reduced recovery. Interestingly, substantial loss of enzyme activity (52%) was observed even in the control group (SS), consisting of LVAB incubated only in buffer indicating that the near neutral pH (pH 6.8±0.1) contributes to bead swelling and degradation as well as the release or inactivation of enzymes. This suggests that further improvements in bead formulation are needed to address degradation issues and enhance enzyme stability and recovery during passage through rumen. Future work will focus on developing more robust bead matrices, potentially incorporating additional protective layers or advanced crosslinking techniques to withstand rumen fermentation and pH effect.

Table 1.

Comparison of Initial and 3.5 Month Enzyme Activity in Stored Alginate Beads (HVAB and LVAB).

Table 1.

Comparison of Initial and 3.5 Month Enzyme Activity in Stored Alginate Beads (HVAB and LVAB).

| BEADS |

ENZYME ACTIVITYx0 (U/mL) |

ENZYME ACTIVITYx3.5 months (U/mL) |

| High viscosity alginate beads (HVAB) |

0.189 ± 0.036 |

0.199 ± 0.061 |

| Low viscosity alginate beads (LVAB) |

0.192 ± 0.029 |

0.214 ± 0.072 |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A.; methodology, N.A and N.S.T.; formal analysis, N.A.; Validation, N.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A.; writing—review and editing, N.A, N.S.T, F.J.T, D.Y.Y, R.B, and A.V.K; supervision, N.S.T, F.J.T, D.Y.Y, R.B, and A.V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The first author received a scholarship from UNSW and CSIRO, while the operating expenses were supported by funding from ProAgni Pty Ltd.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO), the University of New South Wales (UNSW), Sydney, Australia in the framework of the excellence initiative and funding and ProAgni Pty Ltd. I would like to extend my gratitude to Mark Greaves and Michael Mazzonetto from CSIRO for their support and assistance during the experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- ALMASSRI, N., TRUJILLO, F. J. & TEREFE, N. S. 2024. Microencapsulation technology for delivery of enzymes in ruminant feed. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 11, 1352375.

- ANJANI, K. Microencapsulation of flavour-enhancing enzymes for acceleration of cheddar cheese ripening. 2007.

- AZARNIA, S., LEE, B. H., ROBERT, N. & CHAMPAGNE, C. P. 2008. Microencapsulation of a recombinant aminopeptidase (PepN) from Lactobacillus rhamnosus S93 in chitosan-coated alginate beads. Journal of microencapsulation, 25, 46-58.

- BARTOSZ, T. & IRENE, T. 2016. Polyphenols encapsulation – application of innovation technologies to improve stability of natural products. Physical Sciences Reviews, 1.

- BEN MESSAOUD, G., SÁNCHEZ-GONZÁLEZ, L., PROBST, L., JEANDEL, C., ARAB-TEHRANY, E. & DESOBRY, S. 2016. Physico-chemical properties of alginate/shellac aqueous-core capsules: Influence of membrane architecture on riboflavin release. Carbohydrate Polymers, 144, 428-437.

- CHUANG, J.-J., HUANG, Y.-Y., LO, S.-H., HSU, T.-F., HUANG, W.-Y., HUANG, S.-L. & LIN, Y.-S. 2017. Effects of pH on the Shape of Alginate Particles and Its Release Behavior. International Journal of Polymer Science, 2017, 3902704.

- CORRALES UREÑA, Y. R., LISBOA-FILHO, P. N., SZARDENINGS, M., GÄTJEN, L., NOESKE, P.-L. M. & RISCHKA, K. 2016. Formation and composition of adsorbates on hydrophobic carbon surfaces from aqueous laccase-maltodextrin mixture suspension. Applied Surface Science, 385, 216-224.

- COSTA, J. B., NASCIMENTO, L. G. L., MARTINS, E. & DE CARVALHO, A. F. 2024. Immobilization of the β-galactosidase enzyme by encapsulation in polymeric matrices for application in the dairy industry. Journal of Dairy Science.

- FARHADIAN, S., SHAREGHI, B., MOMENI, L., ABOU-ZIED, O. K., SIROTKIN, V. A., TACHIYA, M. & SABOURY, A. A. 2018. Insights into the molecular interaction between sucrose and α-chymotrypsin. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 114, 950-960.

- GUNAWARDANA, C. A., KONG, A., BLACKWOOD, D. O., TRAVIS POWELL, C., KRZYZANIAK, J. F., THOMAS, M. C. & CALVIN SUN, C. 2023. Magnesium stearate surface coverage on tablets and drug crystals: Insights from SEM-EDS elemental mapping. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 630, 122422.

- KAILASAPATHY, K., PERERA, C. & PHILLIPS, M. 2006. Evaluation of Alginate-Starch Polymers for Preparation of Enzyme Microcapsules. International Journal of Food Engineering, 2.

- KIM, I. Y., AHN, G. C., KWAK, H. J., LEE, Y. K., OH, Y. K., LEE, S. S., KIM, J. H. & PARK, K. K. 2015. Characteristics of Wet and Dried Distillers Grains on In vitro Ruminal Fermentation and Effects of Dietary Wet Distillers Grains on Performance of Hanwoo Steers. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci, 28, 632-8.

- KRASAEKOOPT, W., BHANDARI, B. & DEETH, H. 2003. Evaluation of encapsulation techniques of probiotics for yoghurt. International Dairy Journal, 13, 3-13.

- MONG THU, T. T. & KRASAEKOOPT, W. 2016. Encapsulation of protease from Aspergillus oryzae and lipase from Thermomyces lanuginoseus using alginate and different copolymer types. Agriculture and Natural Resources, 50, 155-161.

- MORALES, E., RUBILAR, M., BURGOS-DÍAZ, C., ACEVEDO, F., PENNING, M. & SHENE, C. 2017. Alginate/Shellac beads developed by external gelation as a highly efficient model system for oil encapsulation with intestinal delivery. Food Hydrocolloids, 70, 321-328.

- PARTOVINIA, A. & VATANKHAH, E. 2019. Experimental investigation into size and sphericity of alginate micro-beads produced by electrospraying technique: Operational condition optimization. Carbohydrate polymers, 209, 389-399.

- QUIROGA, E., ILLANES, C., OCHOA, N. & BARBERIS, S. 2011. Performance improvement of araujiain, a cystein phytoprotease, by immobilization within calcium alginate beads. Process Biochemistry, 46, 1029-1034.

- SEGALE, L., GIOVANNELLI, L., MANNINA, P. & PATTARINO, F. 2016. Calcium alginate and calcium alginate-chitosan beads containing celecoxib solubilized in a self-emulsifying phase. Scientifica, 2016, 5062706.

- SHAIBANI, M., MIRSHEKARLOO, M. S., SINGH, R., EASTON, C. D., COORAY, M. C. D., ESHRAGHI, N., ABENDROTH, T., DÖRFLER, S., ALTHUES, H., KASKEL, S., HOLLENKAMP, A. F., HILL, M. R. & MAJUMDER, M. 2020. Expansion-tolerant architectures for stable cycling of ultrahigh-loading sulfur cathodes in lithium-sulfur batteries. Science Advances, 6, eaay2757.

- SIANG, S., WAI, L., NYAM, K. & PUI, L. P. 2019. Effect of added prebiotic (Isomalto-oligosaccharide) and Coating of Beads on the Survival of Microencapsulated Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. Food Science and Technology, 39.

- STOJANOVIC, R., BELSCAK-CVITANOVIC, A., MANOJLOVIC, V., KOMES, D., NEDOVIC, V. & BUGARSKI, B. 2012. Encapsulation of thyme (Thymus serpyllum L.) aqueous extract in calcium alginate beads. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 92, 685-696.

- TANG, J. C., TANIGUCHI, H., CHU, H., ZHOU, Q. & NAGATA, S. 2009. Isolation and characterization of alginate-degrading bacteria for disposal of seaweed wastes. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 48, 38-43.

- TEREFE, N. S., SHEEAN, P., FERNANDO, S. & VERSTEEG, C. 2013. The stability of almond β-glucosidase during combined high pressure-thermal processing: a kinetic study. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 97, 2917-28.

- THU, T. T. M. & KRASAEKOOPT, W. 2016. Encapsulation of protease from Aspergillus oryzae and lipase from Thermomyces lanuginoseus using alginate and different copolymer types. Agriculture and Natural Resources, 50, 155-161.

- TILLEY, J. & TERRY, D. R. 1963. A two-stage technique for the in vitro digestion of forage crops. Grass and forage science, 18, 104-111.

- TRIVEDI, A. H., SPIESS, A. C., DAUSSMANN, T. & BÜCHS, J. 2006. Effect of additives on gas-phase catalysis with immobilised Thermoanaerobacter species alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH T). Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 71, 407-414.

- TUNKALA, B. Z., DIGIACOMO, K., ALVAREZ HESS, P. S., DUNSHEA, F. R. & LEURY, B. J. 2022. Rumen fluid preservation for in vitro gas production systems. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 292, 115405.

- TUNKALA, B. Z., DIGIACOMO, K., ALVAREZ HESS, P. S., DUNSHEA, F. R. & LEURY, B. J. 2023a. Impact of rumen fluid storage on in vitro feed fermentation characteristics. Fermentation, 9, 392.

- TUNKALA, B. Z., DIGIACOMO, K., ALVAREZ HESS, P. S., DUNSHEA, F. R. & LEURY, B. J. 2023b. In vitro protein fractionation methods for ruminant feeds. animal, 17, 101027.

- ZHANG, X., ZHAO, Y., WU, X., LIU, J., ZHANG, Y., SHI, Q. & FANG, Z. 2021. Ultrasonic-assisted extraction, calcium alginate encapsulation and storage stability of mulberry pomace phenolics. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization, 15, 4517-4529.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).