Submitted:

07 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Microorganisms

2.2. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds

2.3. Encapsulation of Bioactive Compounds

2.4. Determination of the Viability of Lactobacillus Fabifermentans

2.5. Gastrointestinal Simulation

2.6. Quantification of Phenolic Compounds in the Beads

2.7. Preparation of Yogurt

2.7.1. Viability of Lactobacillus Fabifermentans in Yogurt

2.7.2. Physicochemical Analysis of Yogurt

2.8. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

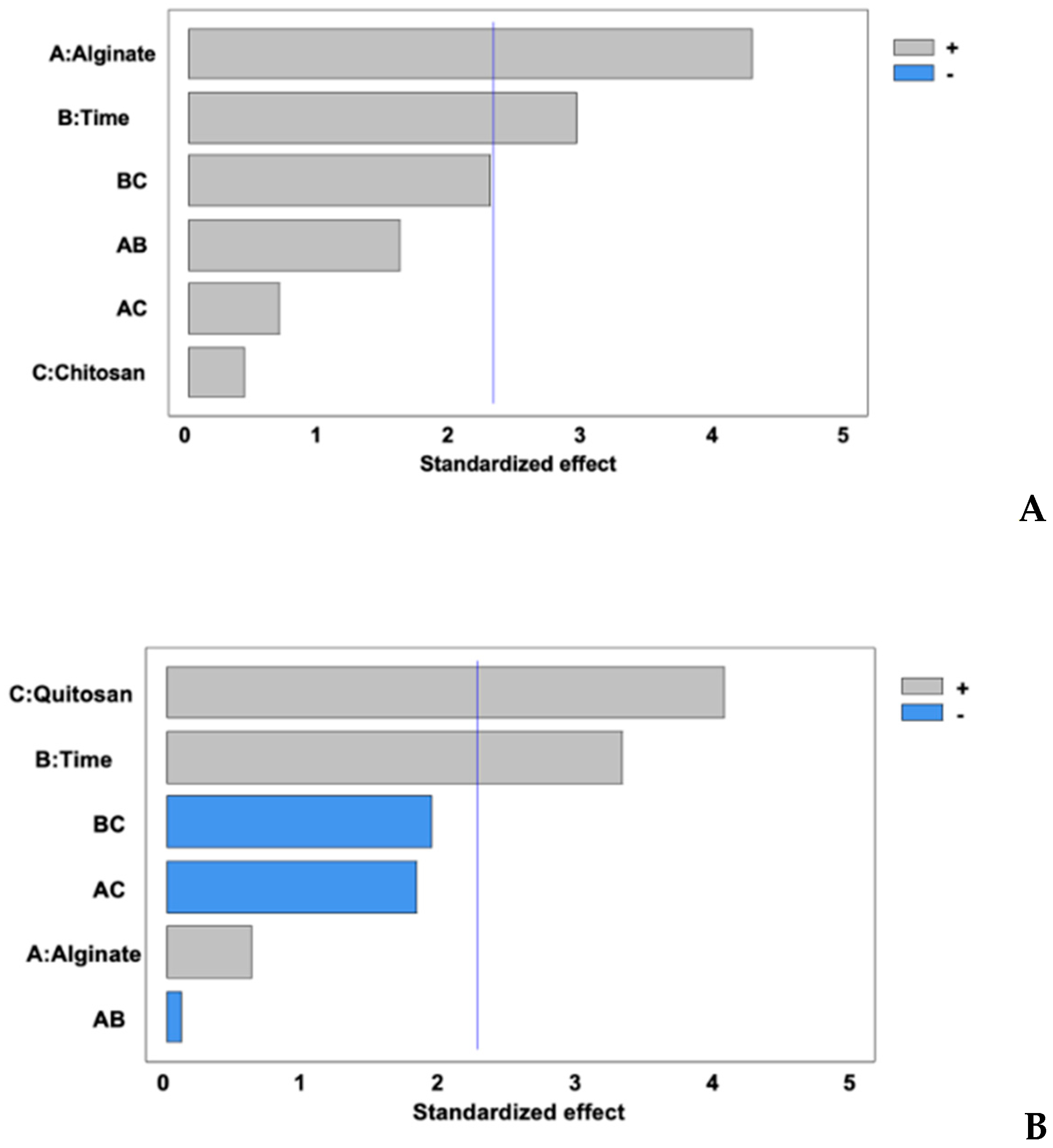

3.1. Encapsulation of Lactobacillus Fabifermentans BAL-27-ITTG and Phenolic Compounds

3.1.1. Viability of Encapsulated Lactobacillus Fabifermentans BAL-27-ITTG

3.1.2. Encapsulated Phenolic Compounds

3.1.3. Viability of Lactobacillus Fabifermentans BAL-27-ITTG During Gastrointestinal Simulation

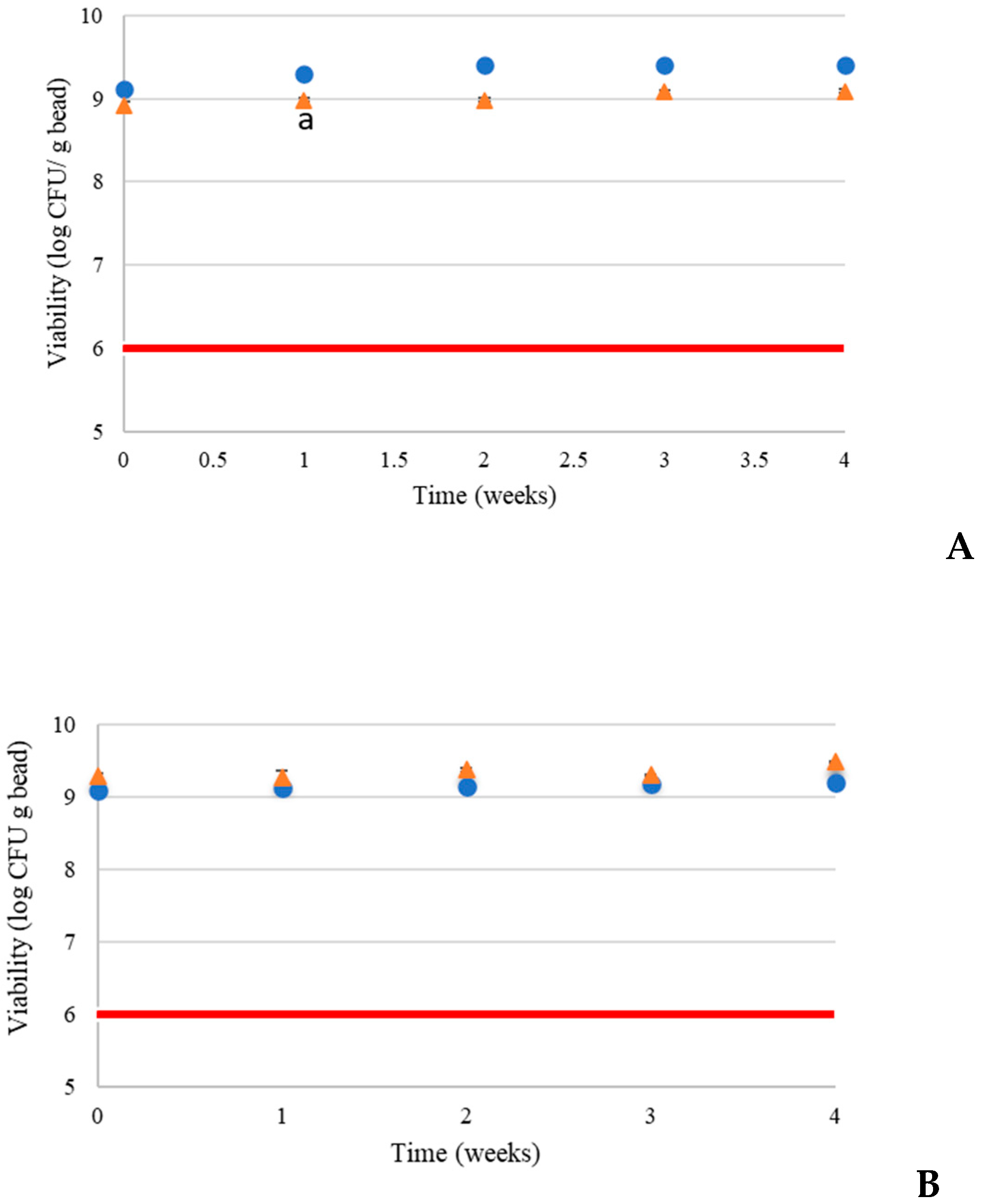

3.2. Evaluation of the Quality of Alginate Beads During Yogurt Storage

3.2.1. Viability of Lactobacillus Fabifermentans BAL-27-ITTG

3.2.2. Phenolic Compounds in Beads During Storage

3.2.3. Viability of Lactobacillus Fabifermentans BAL-27-ITTG from Alginate Beads During Gastrointestinal Simulation After Four Weeks of Yogurt Storage

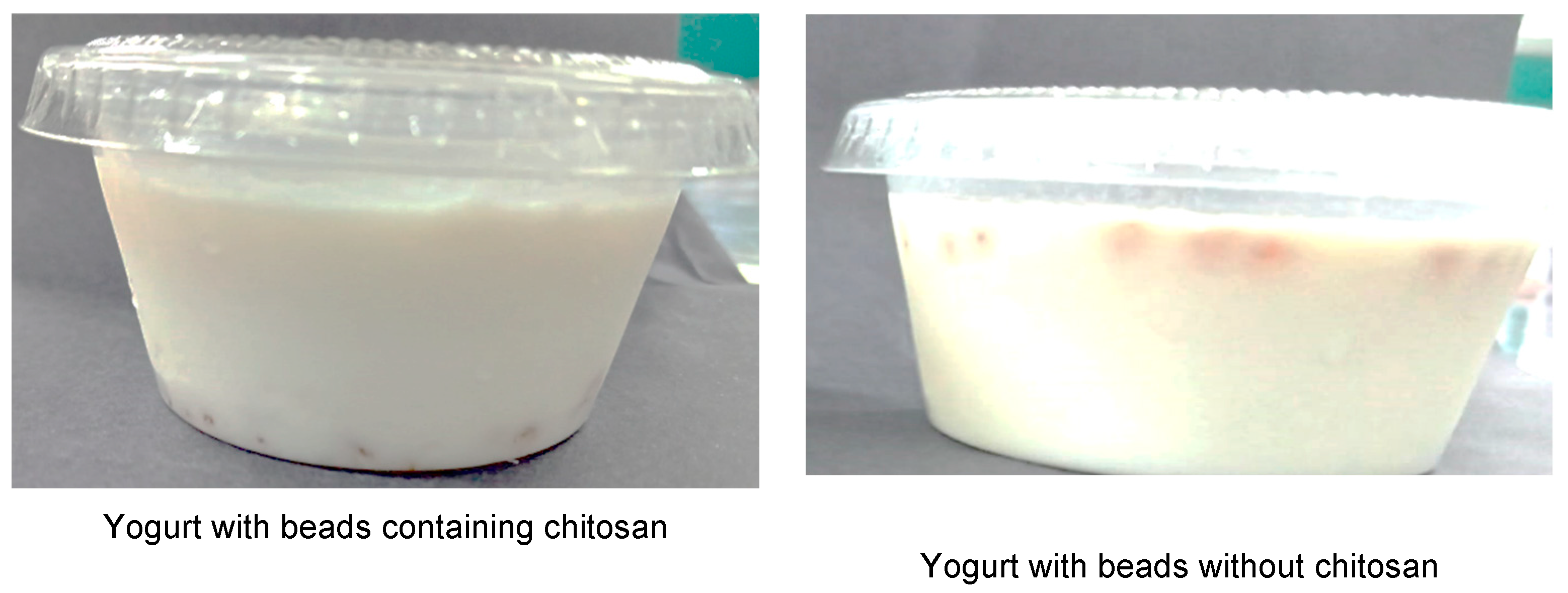

3.3. Effects of the Addition of Lactobacillus Fabifermentans and Encapsulated Phenolic Compounds on the Physicochemical and Sensory Properties of Yogurt

3.3.1. Determination of the Physicochemical and Microbiological Properties of Yogurt

Yogurt Syneresis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript | . |

| EE | Encapsulation Efficiency |

| GAE | Gallic Acid Equivalents |

| MEE | Microbial Encapsulation Efficiency |

| PCEE | Phenolic Compounds Encapsulation Efficiency |

| RGS | Resistance of Gastrointestinal Simulation |

References

- Santeramo, F.G.; Carlucci, D.; De Devitiis, B.; Seccia, A.; Stasi, A.; Viscecchia, R.; Nardone, G. Emerging trends in European food, diets and food industry. Food Res Inter. 2018, 104, 39-47. [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.P.; Tulini, F.L.; Martins, E.; Penning, M.; Favaro-Trindade, C.S.; Poncelet, D. Comparison of extrusion and co-extrusion encapsulation techniques to protect Lactobacillus acidophilus LA3 in simulated gastrointestinal fluids. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2018, 89, 392-399. [CrossRef]

- De Prisco, A.; Van, H.J.; Flogiano, V.; Mauriello, G. Microencapsulated starter culture during yogurt manufacturing, effect on technological features. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017, 10(10), 1767-1777. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, D. Development of antioxidant rich fruit supplemented probiotic yogurts using free and microencapsulated Lactobacillus rhamnosus culture. J Food Sci Technol. 2016, 53(1), 667-675. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Pérez, J.I.; Álvarez-Gutiérrez, P.E.; Luján-Hidalgo, M.C.; Ovando-Chacón, S.L.; Soria-Guerra, R.E.: Ruiz-Cabrera, M. A.; Grajales-Lagunes, A.; Abud-Archila, M. Effect of linear and branched fructans on growth and probiotic characteristics of seven Lactobacillus spp. isolated from an autochthonous beverage from Chiapas, Mexico. Arch Microbiol 2022, 364. [CrossRef]

- Bartoszek, M.; Polak, J. An electron paramagnetic resonance study of antioxidant properties of alcoholic beverages. Food Chem. 2012, 132(4), 2089-2093. [CrossRef]

- Belščak, A.; Komez, D.; Karlović, S.; Djaković, S.; Špolijarć, I.; Mršić, G.; Ježek, D. Improving the controlled delivery formulation of caffeine in alginate in alginate hidrogel beads combined with pectin, carrageenan, chitosan and psyllium. Food Chem. 2015, 167, 378-386. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. ; Duan, M.; Hou, D.; Chen, X.; Shi, J.; Zhou, W. Fabrication and characterization of Ca (II)-alginate-based beads combined with different polysaccharides as vehicles for delivery, release and storage of tea polyphenols. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 112, 106274. [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, L.F.; Teixeira, J.A.; Mussatto, S.I. Selection of the solvent and extraction conditions for maximum recovery of antioxidant phenolic compounds from coffee silverskin. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2014. 7(5), 1322-1332. [CrossRef]

- Heeger, A.; Konsińka, A.; Cantergiani, E.; Andlauer, W. Bioactives of coffee Cherry pulp and its utilisation for production of cascara beverage. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 969-975. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, E.F.; Luzia, D.M.M.; Jorge, N. Antioxidant compounds extraction from coffe husk: the influence of solvent type and ultrasound exposure time. Acta Sci Technol. 2019, 41(1), 36451. [CrossRef]

- Khochapong, W.; Ketnawa, S.; Ogawa, Y.; Punbusayakul, N. Effect of in vitro digestion on bioactive compunds, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of coffee (Coffea arabica L.) pulp aqueous extract. Food Chem. 2021, 328, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Krasaekoopt, W.; Bhandari, B.; Deeth, H. The influence of coating materials on some properties of alginate beads and survivability of microencapsulated probiotic bacteria. Int Dairy J. 2004, 14(8), 737-743. [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152-178. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Ruiz, M.C. Fortificación de yogurt con fitonanopartículas de ZnO y Lactiplantibacillus fabifermentans BAL-27-ITTG. [ Tesis de maestría en Ciencias de Ingeniería Bioquímica, Instituto Tecnológico Nacional de Tuxtla Gutiérrez]. 2022.

- Zainoldin, K.; Hj Baba, A. The Effect of Hylocereus polyrhizus and Hylocereus undatus on physicochemical, proteolysis, and antioxidant activity in yogurt. World Acad Sci Eng Technol. 2009, 60, 361-366.

- Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-243-SSA1-2010. Productos y servicios. Leche, fórmula láctea, producto lácteo combinado y derivados lácteos. Disposiciones y especificaciones sanitarias. Métodos de prueba. [Consultado el 10 de Julio de 2023]. http://dof.gob.mx/normasOficiales/4156/salud2a/salud2a.htm.

- Phùng, T.; Dinh, H.; Ureña, M.; Oliete, B.; Denimal, E.; Dupont, S.; Beney, L.; Karbowiak, T. Sodium Alginate as a promising encapsulating material for extremely-oxygen sensitive probiotics. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 160. [CrossRef]

- Das, A.B.; Goud, V.V.; Das, C. Phenolic compounds as functional ingredients in beverages. In Value-added ingredients and enrichments of beverages. Academic Press. 2019.

- Izadi, Z.; Nasirpour, A.; Garoosi, G.A.; Tamjidi, F. Rheological and physical properties of yogurt enriched with phytosterol during storage. J Food Sci Technol. 2015, 52, 5341-5346. [CrossRef]

- Cheng H. Volatile flavor compounds in yogurt: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2010, 50(10),938–950. [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.; Arief, I.I.; Taufik, E. Formulasi yoghurt probiotik karbonasi dan potensi sifat fungsionalnya. Jurnal Ilmu Produksi dan Teknologi Hasil Peternakan, 2014, 2(1), 213-218.

- Kailasapathy, K. Survival of free and encapsulated probiotic bacteria and their effect on the sensory properties of yoghurt. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2006, 39(10), 1221-1227. [CrossRef]

- Sert, D.; Mercan, E.; Dertli, E. Characterisation of lactic acid bacteria from yogurtlike product fermented with pine cone and determination of their role on physicochemical, textural and microbiological properties of product. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2017, 78, 70-76. [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadeh, S.; Gandomi, H.; Misaghi, A.; Bokaei S.; Noori, N. The effect of alginate and chitosan concentrations on some properties of chitosan-coated alginate beads and survivability of encapsulated Lactobacillus rhamnosus in simulated gastrointestinal conditions and during heat processing. J Sci Food Agric. 2014, 94, 2210–221. [CrossRef]

- Łętocha, A.; Miastkowska, M.; Sikora, E. Preparation and characteristics of alginate microparticles for food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic applications. Polym. 2022, 14(18), 1-32. [CrossRef]

- Gedam, S.; Jadhav, P.; Talele, S.; Jadhav, A. Effect of crosslinking agent on development of gastroretentive mucoadhesive microspheres of risedronate sodium. Int J Appl Pharm. 2018, 10, 133–140. [CrossRef]

- Abud-Archila, M.; Mendoza, C. Jícama mínimamente procesada fortificada con probióticos y compuestos fenólicos de café verde microencapsulados. Biotecnia, 2024, 26, e2350. [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.R.; Silva, P.M.P.; Vicente, A.A.; Souza-Soares, L.A.; Pinheiro, A.C.; Cerqueira, M.A. Alginate particles for encapsulation of phenolic extract from Spirulina sp. LEB-18: physicochemical characterization and assessment of in vitro gastrointestinal behavior. Polym, 2022, 14(21), 4759. [CrossRef]

- FAO, OMS Organización de las Naciones Unidad para la Alimentación y la Agricultura y Organización Mundial de la Salud. 2001. https://www.fao.org/3/a0512s/a0512s.pdf.

- Arriola, N.D.A.; Chater, P.I.; Wilcox, M.; Lucini, L.; Rocchetti, G.; Dalmina, M.; Pearson, J.P.; Amboni, R.D.D.M.C. Encapsulation of Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni aqueous crude extracts by ionic gelation–Effects of alginate blends and gelling solutions on the polyphenolic profile. Food Chem. 2019, 275, 123-134. [CrossRef]

- Flamminii, F.; Di Mattia, C.D.; Nardella, M.; Chiarini, M.; Valbonetti, L.; Neri, L.; Difonzo, G; Pittia, P. Structuring alginate beads with different biopolymers for the development of functional ingredients loaded with olive leaves phenolic extract. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 108, 105849. [CrossRef]

- Martinović, J.; Lukinac, J.; Jukić, M.; Ambrus, R.; Planinić, M.; Šelo, G.; Klarić, A.-M.; Perković, G.; Bucic-Kojic, A. Physicochemical characterization and evaluation of gastrointestinal in vitro behavior of alginate-based microbeads with encapsulated Grape pomace extracts. Fharmaceutics. 2023, 15, 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.; Gonçalves, I.; Moreno, P.; Gonçalves, R.; Santos, S.; Pêgo, A.; Amaral, I. Chitosan. Comprehensive Biomaterials II. 2017, 2nd Edition.

- Liang, J.; Yan, H.; Puligundla, P.; Gao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wan, X. Applications of chitosan nanoparticles to enhance absorption and bioavailability of tea polyphenols: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 69, 286–292. [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.; Saeed, M.; Pasha, I.; Shahid, M. A prebiotic-based biopolymeric encapsulation system for improved survival of Lactobacillus rhamnosus. Food Biosci. 2020, 37, 100679. [CrossRef]

- Murthy, P.S.; Madhava Naidu, M. Sustainable management of coffee industry byproducts and value addition - A review. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2012, 66, 45–58. [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.; Galrinho, M.; Passos, C.; Espírito, L.; Simona, M.; Ranga, F.; Puga, H.; Palmeira, J.; Coimbra, M.; Oliveira, M.; Ferreira, H.; Alves, R. Prebiotic potential of a coffee silverskin extract obtained by ultrasound-assisted extraction on Lacticaseibacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei. J Funct Foods. 2024, 120. [CrossRef]

- Chaikham, P. Stability of probiotics encapsulated with Thai herbal extracts in fruit juices and yogurt during refrigerated storage. Food Biosci. 2015, 12, 61-66. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Rahaman, A.; Uddin, E.; Rafid, M.; Hosen, S.; Layek, K. Development and characterization of chitosan-based antimicrobial films: A sustainable alternative to plastic packaging. Cleaner Chem Eng. 2025, 11. [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.; Lee, B.B.; Ravindra, P.; Poncelet, D. Prediction models for shape and size of ca-alginate macrobeads produced through extrusion–dripping method. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 338(1), 63-72. [CrossRef]

- Gombotz, W.R.; Wee, S.F. Protein release from alginate matrices. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2012, 64, 194-205. [CrossRef]

- Belščak-Cvitanović, A.; Đorđević, V.; Karlović, S.; Pavlović, V.; Komes, D.; Ježek, D.; Bugarsky, B.; Nedović, V. Protein-reinforced and chitosan-pectin coated alginate microparticles for delivery of flavan-3-ol antioxidants and caffeine from green tea extract. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 51. [CrossRef]

- Pasparakis, G.; Bouropoulos, N. Swelling studies and in vitro release of verapamil from calcium alginate and calcium alginate–chitosan beads. Int J Pharm. 2006, 323(1-2), 34-42. [CrossRef]

- Romero del Castillo S.; Mestres Lagarriga, J. Productos lácteos: Tecnología. Editorial Up. 159 pp. 2004.

- Feng, Y; Niu, L.; Li, D.; Zeng, Z.; Sun, C.; Xiao, J. Effect of calcium alginate/collagen hydrolysates beads encapsulating high-content tea polyphenols on quality characteristics of set yogurt during cold storage. LWT-Food Sci and Technol. 2024, 191, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Pourjafar, H.; Noori, N.; Gandomi, H.; Basti, A.A.; Ansari, F. Viability of microencapsulated and non-microencapsulated Lactobacilli in a commercial beverage. Biotechnol Rep. 2020, 25, e00432. [CrossRef]

- Budianto, E.; Saepudin, E.; Nasir, M. The encapsulation of Lactobacillus casei probiotic bacteria based on sodium alginate and chitosan. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 483(1), 012043. IOP Publishing, 2020.

- Rahmani, F.; Gandomi, H.; Noori, N.; Faraki, A.; Farzaneh, M. Microbial, physiochemical and functional properties of probiotic yogurt containing Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium bifidum enriched by green tea aqueous extract. Food Sci Nutr. 2021, 9(10), 5536-5545. [CrossRef]

| Treatment |

Viability (Log10 CFU/g bead) |

MEE (%) |

PC (mg GAE/g bead) |

PCEE |

RGS (%) |

| T1 | 8.83c | 82.97b | 0.48a | 14.22c | 84.38 ab |

| T2 | 9.09abc | 82.86b | 0.49a | 17.02bc | 83.82 b |

| T3 | 9.45a | 84.70a | 0.47a | 19.75ab | 85.34 a |

| T4 | 9.47a | 84.84a | 0.51a | 20.99a | 73.65 e |

| T5 | 8.91bc | 81.00c | 0.48a | 20.86a | 75.51 d |

| T6 | 9.00abc | 81.79c | 0.52a | 19.12ab | 84.08 ab |

| T7 | 9.29abc | 83.47b | 0.52a | 19.06ab | 77.94 c |

| T8 | 9.38ab | 83.31b | 0.52a | 20.89a | 76.11 d |

| Tukey | 0.532 | 1.01 | 0.07 | 3.03 | 1.50 |

| Treatment | Storage time (weeks) | Tukey | |

| 0 | 4 | ||

| T1 | 0.48Aa | 0.43Bb | 0.04 |

| T2 | 0.49Aa | 0.45Bb | 0.04 |

| T3 | 0.47Aa | 0.41Babc | 0.08 |

| T4 | 0.51Aa | 0.52Aa | 0.07 |

| T5 | 0.48Aa | 0.47Aabc | 0.13 |

| T6 | 0.52Aa | 0.48Babc | 0.02 |

| T7 | 0.52Aa | 0.52Aa | 0.04 |

| T8 | 0.52Aa | 0.50Aab | 0.02 |

| Tukey | 0.07 | 0.04 | |

| Treatment |

RGS (%) |

| T1 | 89.82a |

| T2 | 83.82c |

| T3 | 84.22c |

| T4 | 79.86d |

| T5 | 73.25f |

| T6 | 88.09b |

| T7 | 77.23e |

| T8 | 71.88g |

| Tukey | 2.8104 |

| Treatment | Time (weeks) | ||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Tukey | ||

| T1 | 20.65Ac | 23.40Bc | 25.52Cc | 25.29Cc | 28.48Dc | 1.42 | |

| T2 | 21.03Acd | 24.74Bc | 24.74Bc | 24.91Bc | 25.09Bb | 0.97 | |

| T3 | 21.84Ade | 24.1Bc | 24.21Bc | 25.41Cc | 25.91Cb | 1.01 | |

| T4 | 29.70Ag | 31.37Ad | 34.57Bf | 39.26Cf | 39.93Cf | 1.88 | |

| T5 | 22.42Ae | 24.45Bc | 27.37Cd | 29.91Dd | 35.45Ed | 1.50 | |

| T6 | 17.60Ab | 18.84Ab | 21.33Bb | 23.36Cb | 25.56Db | 1.88 | |

| T7 | 23.73Af | 27.69Bd | 29.65Ce | 30.46Cd | 38.33De | 1.90 | |

| T8 | 23.06Af | 25.65Bcd | 28.52Cde | 32.86De | 37.54Ee | 0.86 | |

| Control | 13.63Aa | 15.29Ba | 17.71Ca | 20.14Da | 20.58Da | 1.33 | |

| Tukey | 1.00 | 2.77 | 1.95 | 1.04 | 1.02 | ||

| Treatment | Time (weeks) | |||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Tukey | |

| T1 | 4.34Aa | 4.09Bd | 4.00BCc | 3.97Cb | 3.97Ccd | 0.08 |

| T2 | 4.32Aab | 4.09Bd | 4.03Bc | 3.96Cb | 3.93Cd | 0.06 |

| T3 | 4.26Aabc | 4.13Bcd | 4.02Cc | 3.97CDb | 3.96Dcd | 0.05 |

| T4 | 4.29Aabc | 4.15Bbc | 4.09Bb | 4.00Cab | 4.00Cabc | 0.08 |

| T5 | 4.26Aabc | 4.17Bbc | 4.09Cb | 4.01Dab | 4.00Dabc | 0.04 |

| T6 | 4.26Aabc | 4.18ABb | 4.09BCb | 4.03Cab | 3.98Cbcd | 0.13 |

| T7 | 4.27Aabc | 4.17Bbc | 4.10Cb | 4.04Dab | 4.04Dab | 0.05 |

| T8 | 4.27Aabc | 4.15Bbc | 4.10Cb | 4.04Dab | 4.00Eabc | 0.03 |

| Control | 4.34Aa | 4.27Ba | 4.20Ca | 4.11Da | 4.05Ea | 0.03 |

| Tukey | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.06 | |

| Treatment | Time (weeks) | |||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Tukey | |

| 1 | 0.96Abc | 0.98Aab | 0.99Aab | 1.04Bab | 1.11Cabc | 0.03 |

| 2 | 0.94Aab | 0.96Aa | 1.04Bab | 1.09BCab | 1.12Cbc | 0.06 |

| 3 | 0.94Aab | 1.06Bc | 1.06Bb | 1.14Cb | 1.14Cc | 0.02 |

| 4 | 0.94Aab | 0.99ABab | 1.01ABab | 1.03ABa | 1.08Ba | 0.10 |

| 5 | 0.92Aa | 0.95Ba | 0.98Ca | 1.05Dab | 1.09Eab | 0.01 |

| 6 | 0.96Abc | 1.03ABbc | 1.05BCb | 1.12Cab | 1.14Cc | 0.08 |

| 7 | 0.95Abc | 1.02Bbc | 1.06Cb | 1.10Dab | 1.12Eab | 0.02 |

| 8 | 0.98Ac | 1.03ABbc | 1.06BCb | 1.11Cab | 1.09BCab | 0.07 |

| Control | 0.92Aa | 0.96ABa | 1.00Bab | 1.05Cab | 1.09Cab | 0.04 |

| Tukey | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | |

| Treatment | L. fabifermentans (CFU/g yogurt) | Starter culture (CFU/g yogurt) |

| T1 | ~104 | ~109 |

| T2 | ~103 | ~109 |

| T3 | ~104 | ~109 |

| T4 | ND | ~109 |

| T5 | ND | ~109 |

| T6 | ~103 | ~109 |

| T7 | ND | ~109 |

| T8 | ND | ~109 |

| Time (days) | Treatment | ||||||||||

| Control | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 | T7 | T8 | Tukey | ||

| Color | 0 | 6.26a | 5.25cd | 5.08d | 5.56bcd | 6.05ab | 5.38cd | 5.66bcd | 6.25ab | 5.80abc | 0.56 |

| 28 | 6.50a | 5.46c | 5.57c | 5.89abc | 6.39ab | 6.16abc | 5.7bc | 6.36ab | 6.40ab | 0.77 | |

| Smell | 0 | 6.05a | 5.36b | 5.41b | 5.71ab | 5.48ab | 5.18b | 5.78ab | 5.80ab | 5.50ab | 0.63 |

| 28 | 6.14a | 5.46a | 5.67a | 5.82a | 5.82a | 5.56a | 5.50a | 5.70a | 5.86a | 0.90 | |

| Flavor | 0 | 6.29a | 4.73d | 5.21cd | 5.3bcd | 5.38bcd | 5.70abc | 5.55bc | 5.91ab | 5.51bc | 0.69 |

| 28 | 6.28a | 5.35ab | 5.42ab | 5.67ab | 6.0ab | 5.60ab | 5.16ab | 5.66ab | 6.16a | 0.98 | |

| Texture | .0 | 5.85a | 4.6c | 4.91bc | 5.15abc | 5.16abc | 4.56c | 4.98bc | 5.43ab | 5.11bc | 0.84 |

| 28 | 6.17a | 5.07bc | 4.28c | 5.10bc | 5.75abc | 5.33ab | 5.33abc | 5.76ab | 5.86ab | 0.95 | |

| Global Appearance | 0 | 6.25a | 5.01b | 5.2c | 5.40bc | 5.41bc | 5.50bc | 5.45bc | 5.95ab | 5.46bc | 0.11 |

| 28 | 6.42a | 5.42abc | 5.17cd | 5.5bcd | 5.96abc | 5.73abcd | 5.10d | 5.76abcd | 6.06ab | 0.84 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).