1. Introduction

Probiotics are live microorganisms that confer health benefits to the host when consumed in adequate amounts [

1]. They play a crucial role in maintaining gut microbiota balance, enhancing immune function, and preventing gastrointestinal (GI) disorders [

2]. Among them,

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LRGG) is one of the most well-documented probiotic strains, widely recognized for its ability to improve gut health and provide resistance against pathogenic infections [

3]. However, to exert their beneficial effects, probiotics must survive the harsh conditions of the GI tracts, including exposure to gastric acid, digestive enzymes, and bile salts [

4]. A significant challenge in probiotic applications is ensuring their viability throughout digestion and storage, which has led to increasing interest in encapsulation technologies as a protective strategy.

Encapsulation involves enclosing probiotics within protective materials to shield them from adverse external factors, such as acidity, oxidation, and mechanical stress [

5]. Various encapsulation techniques have been explored, including spray drying, extrusion, emulsion-based methods, and hydrogel entrapment, each offering different levels of protection and controlled release [

6]. Alginate-based encapsulation is among the most widely studied approaches due to its biocompatibility, cost-effectiveness, and ability to form gel matrices that enhance probiotic stability [

7]. Furthermore, chitosan-coated alginate beads provide additional protection, as chitosan enhances resistance to acidic environments and bile salts, improving probiotic survival during digestion [

7,

8].

In addition to encapsulation, the presence of food materials in the digestive environment may significantly impact probiotic survival. Certain food components, such as proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids may provide additional protection to probiotics by buffering the acidic conditions of gastric juice or influencing the structure of encapsulation matrices. At the same time, incorporating food materials in digestion models may offer a more realistic simulation of real-world consumption, as probiotics are typically ingested with food rather than in isolation. Therefore, evaluating the role of food matrices in probiotic protection is essential for developing effective functional foods.

Traditionally, static

in vitro GI models have been used to evaluate the survival of encapsulated probiotics. These models provide controlled conditions, where pH, enzyme concentrations, and digestion times are maintained at predefined levels [

5,

9]. In contrast, dynamic

in vitro GI models offer a more realistic simulation of digestion by incorporating gradual pH changes, continuous replenishment of digestive fluids, and peristaltic movements, mimicking the actual

in vivo environment more accurately [

10].

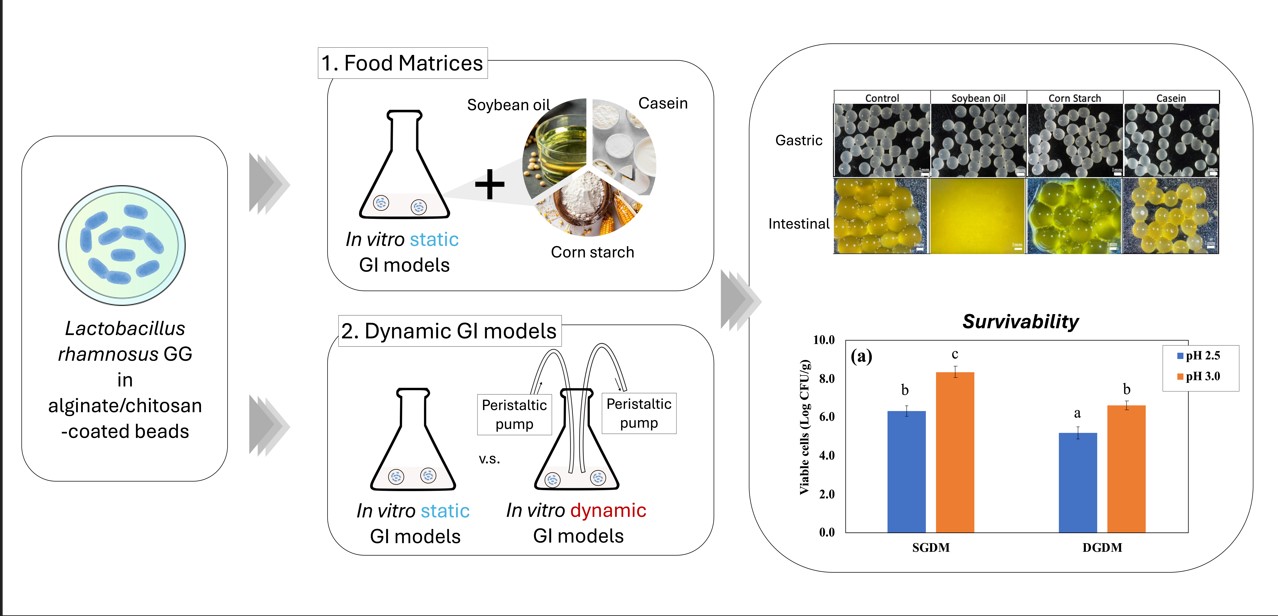

One of the main aims of this study is to evaluate the effects of food matrices, such as casein, corn starch, and soybean oil, on the survivability of encapsulated probiotics in GI conditions. At the same time, this study aims to assess probiotic encapsulants using in vitro dynamic GI models, as most studies to date have been conducted using static models. While static models provide useful insights, they may not fully capture the complexities of digestion, potentially leading to misinterpretations of probiotic viability and efficacy. By incorporating dynamic models, this study aims to assess the protective effects of different encapsulation strategies under physiologically relevant conditions. The findings from this research will provide valuable insights into the optimization of encapsulation techniques, the role of food matrices in probiotic protection, and the importance of dynamic GI models in assessing probiotic stability. This study contributes to the development of more effective probiotic formulations for functional food applications, ensuring enhanced survival and bioavailability in the human digestive tract.

2. Materials

Freeze-dried Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG ATCC 53103 was obtained from commercial probiotic capsules (i-Health inc., Denmark). Peptone was purchased from Becton, Dickinson and Company (New Jersey, USA). MRS broth and MRS agar were obtained from Alpha Biosciences (Maryland, USA). Sodium alginate (SA) was purchased from bioWORLD (Ohio, USA). Chitosan (50-100 mPa·s 0.5 % in 0.5 % acetic acid at 20 °C) was obtained from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., LTD. (Tokyo, Japan). Soybean oil and corn starch were obtained from grocery stores. Digestive enzymes and other chemicals used in this study were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (Missouri, USA).

3. Methods

3.1. Cell Preparation

Freeze-dried L. rhamnosus GG was diluted into sterile 0.1 % (w/v) peptone solution and incubated for 18 hours at 37 °C. The suspended cells were then spread onto MRS agar and incubated for 18 hours at 37 °C to obtain sub-cultures. Thereafter, cultured colony was taken from the agar media and inoculated into MRS broth and incubated for 22 hours at 37 °C to obtain 9-10 Log CFU/mL of proliferated probiotics. The cultured cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,400 × g and then washed twice with sterile 0.1 % peptone solution. Finally, the collected cells were resuspended into sterile 0.1 % peptone solution to adjust the concertation to 10 Log CFU/mL.

3.2. Encapsulation of Lactobacillus Rhamnosusu GG by Ionic Gelation

The cell suspension was mixed with sterile 2.0 % w/v alginate solution at the volume ratio of 1:4 before the extrusion. The mixture was then loaded into a 30 mL syringe with a 22 G needle, followed by dropwise extrusion into 0.1 M sterile CaCl

2 solution at a rate of 5 mL/min using a syringe pump. The beads were placed 30 min for further external gelation. Some beads were subsequently immersed into sterile 0.4 % (w/w) low molecular chitosan solution for 40 min to obtain chitosan-coated alginate microcapsules. After the gelation and coating, the beads were sieved, washed and stored in 0.1 % peptone solution at 4 °C until use. All beads were used for later tests within 2 days. The encapsulation efficiency (EE) was calculated by following equation.

Where N is the number of viable cells in beads (Log CFU/g) and N0 is the number of initial cells added into the samples (Log CFU/g).

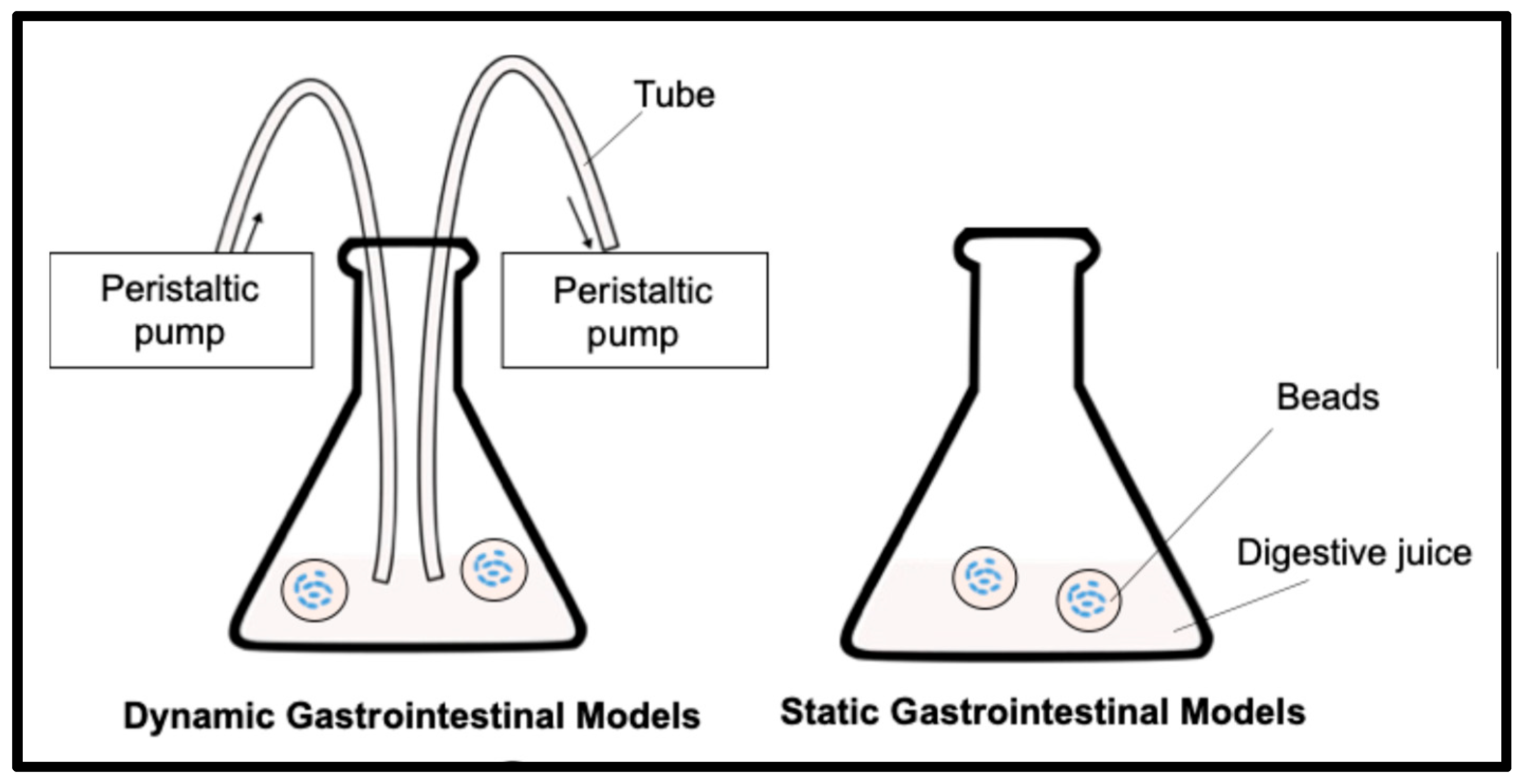

3.3. Viability of Encapsulated Probiotics in In Vitro Static/Dynamic Gastrointestinal Digestion Models

The viability of encapsulated

L. rhamnosus GG was tested with both static and dynamic conditions. Simulated gastric fluid was prepared according to a previously published paper [

11], where it contains 5 mg/mL pepsin (from porcine gastric mucosa, P7000-100G), 6 mg/mL mucin, 5.504 mg/mL NaCl, 1.648 mg/mL KCl, 0.532 mg/mL NaH

2PO

4, 0.798 mg/mL CaCl

2·2H

2O, 0.612 mg/mL NH

4Cl, 0.17 mg/mL urea. The stock solution was first prepared by filter sterilization with 0.45 mm of a membrane filter. Pepsin and mucin were freshly added to the filtered solution right before the gastric testing. 2g of beads were mixed with 18 mL of the simulated gastric fluid in a 50 mL Erlenmeyer flask, and digestion tests were performed for 2 hours by an

in vitro static gastric digestion model (SGDM), where the mixture was incubated in shaking bath at 37 °C and 150 rpm. A dynamic gastric digestion model (DGDM) was also tested, which simulated continuous secreting and emptying of gastric fluid at a rate of 2 mL/min with peristaltic pumps in addition to the SGDM (

Figure 1). The emptying tube was closed with a filter paper to avoid emptying the beads from the model during the test. After the gastric tests, beads were sieved and washed with sterile 0.1 % peptone solution and measured the final weight of beads. The weight ratio of beads was calculated by an equation shown below indicating >100% as swelling and <100% as shrinking, where M

0 is the initial weight and M is the weight after 2 hours of gastric digestion.

The weighed beads were immediately soaked into 1.0 % sterile citrate buffer (pH 6.5) and adjusted to a final volume of 10 mL. The beads were gently agitated on orbital shaker until the beads were completely dissolved. The viability of probiotics was measured by a normal bacterial plate count using MRS agar plates for 48 hours of incubation at 37 °C.

3.4. Release of Encapsulated Probiotics in Static/Dynamic Intestinal Digestion Models

After static gastric digestion for 2 hours, the chitosan-coated alginate beads were transferred to another Erlenmeyer flask and the gastric juice was replaced to the simulated intestinal fluid, which was prepared according to a previously published paper [

12]. Briefly, the intestinal juice was prepared by mixing the simulated pancreatic juice (18 mg/mL porcine pancreatin, 3 mg/mL porcine pancreatic lipase, 14.024 mg/mL NaCl, 6.776 mg/mL NaHCO

3, 1.128 mg/mL KCl, 160.0 mg/mL KH

2PO

4, 100.0 mg/mL MgCl

2, 0.2 mg/mL urea) and the simulated bile juice (60 mg/mL porcine bile extract, 10.518 mg/mL NaCl, 0.752 mg/mL KCl, 11.57 mg/mL NaHCO

3, 0.50 mg/mL urea) followed by adjusting the pH to 8.1 by 1.0 M HCl/NaOH. The release of probiotics from the alginate and alginate-chitosan capsules were tested using

in vitro static intestinal digestion models (SIDM) and

in vitro dynamic intestinal digestion models (DIDM). The 0.1 ml of intestinal fluid was collected every hour up to 4 hours, and the viability of released probiotics was measured by a normal bacterial plate count using MRS agar plates for 48 hours of incubation at 37 °C. The remaining viable cells in the chitosan-coated alginate beads were also measured as described above after 4 hours of intestinal digestion.

3.5. Effect of Food Matrices on In Vitro Gastric Digestion Models

To investigate the effect of food matrices during gastric digestion, corn starch, soybean oil, and casein were additionally added for SGDM and DGDM. 4 g of model food materials were mixed with 2 g of beads and 18 mL simulated gastric fluid, and gastric digestion were performed following the described methods. After 2 hours of gastric digestion, food materials and beads were transferred to another Erlenmeyer flask and replenished with the simulated intestinal fluid.

3.6. Characterization of Microcapsules and Measurements of Size Distribution

The appearance of microcapsules before and after in vitro gastric tests was observed by digital microscope (ADSM302, Andonstar Technology Co.,Ltd., Shenzhen, China). The diameter of initial beads was also calculated by image J software (National Institutes of Health, Maryland, USA) from images of randomly chosen 20 microcapsules, as a circle equivalent. The average value was used as a diameter of the beads.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

All tests were performed independently in triplicate, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for data analysis. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test and two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni’s pairwise t-test were conducted using R (version 4.2.1). All the presented data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, with significance level at p < 0.05.

The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implicates that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Impacts of Food Materials in Static Gastrointestinal Models

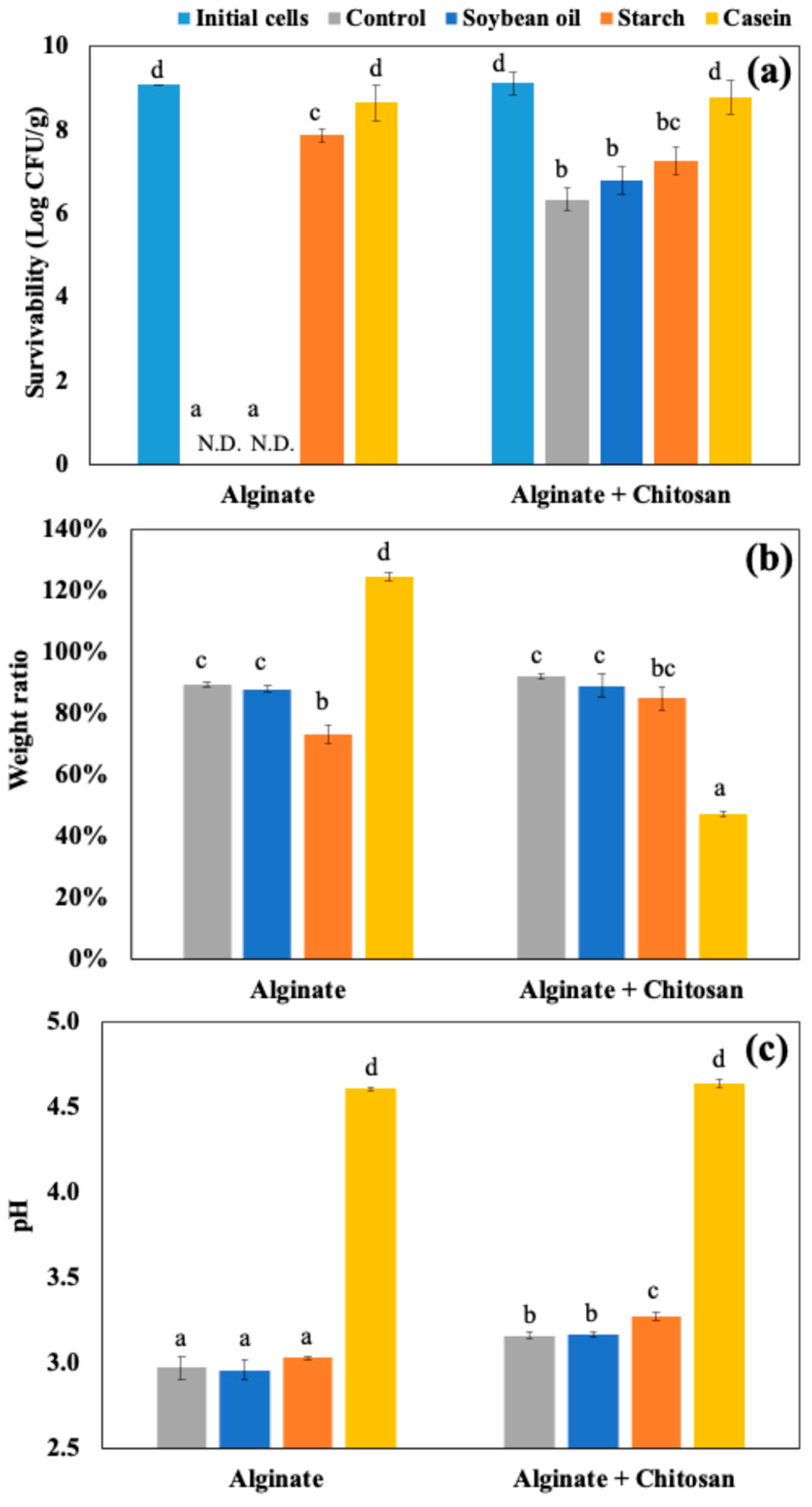

The alginate and chitosan coated beads were prepared and EE of the beads was 98.70 ± 1.56 and 98.42 ± 0.65 % and the particle size was 2.32 ± 0.16 and 2.28 ± 0.13 mm respectively (p>0.05). The impact of food matrices on encapsulated probiotics was investigated using the static GI conditions.

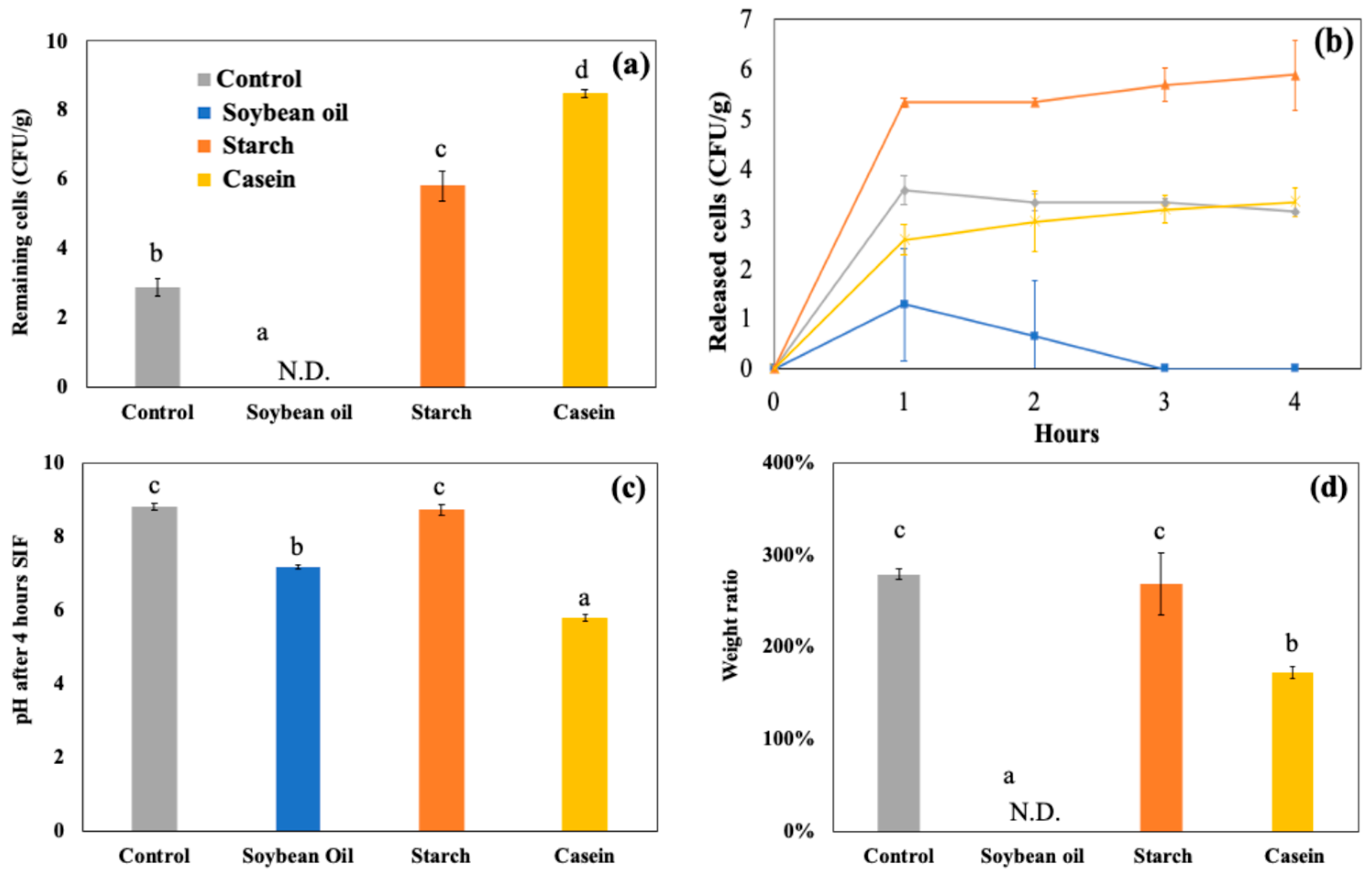

Figure 2(a) shows the number of viable LRGG entrapped in alginate or chitosan-coated alginate beads after 2 hours of digestion using SGDM with model food materials, including soybean oil, corn starch, and casein, and samples without food materials as controls. Overall, the survivability of LRGG was significantly improved when the capsules were coated with chitosan, which has been observed in previous studies [

8]. The addition of casein significantly improved the survival of entrapped LRGG in both alginate and chitosan-coated alginate beads. This was assumed to be mainly due to the significant pH modulation effects of protein component in the gastric juice, which was further discussed below. Other than casein, the viability of LRGG was significantly enhanced when the alginate beads were digested with corn starch, while there were no viable cells observed after when exposed to soybean oil or when no food materials were present. In contrast, there was no significant enhancement observed when soybean oil added, compared to conditions without food materials.

The weight ratio which was measured as swelling or shrinking rates, and pH shifts were also shown in

Figure 2(b) and

Figure 2(c), respectively. Notably, the addition of casein had opposite effects on alginate and chitosan-coated alginate beads, where alginate beads swelled to 124.8 ± 1.3 % of their original weight, while chitosan-coated beads shrank to 47.2 ± 0.9 % after 2 hours of gastric digestion. This discrepancy may be attributed to the difference between the negatively charged alginate and the positively charged chitosan on their surfaces. It is known that the isoelectric point of casein is about 4.6, which results in a positive charge on the protein during the gastric digestion. Regarding pH shifts, it was clearly indicated that the addition of casein significantly modulated the acidity of gastric juice compared to the control and other food materials (p<0.05), increasing the pH from 2.5 to 4.6 after 2 hours gastric testing. Alginate beads showed a slightly lower pH compared to chitosan-coated beads after 2 hours static gastric digestions (p<0.05) while no significant difference was observed among the control, soybean oil, and starch in alginate beads (p>0.05). The addition of corn starch slightly increased the pH in the gastric juice of chitosan-coated beads more than the control and soybean oil, while no significant improvement on survivability was shown.

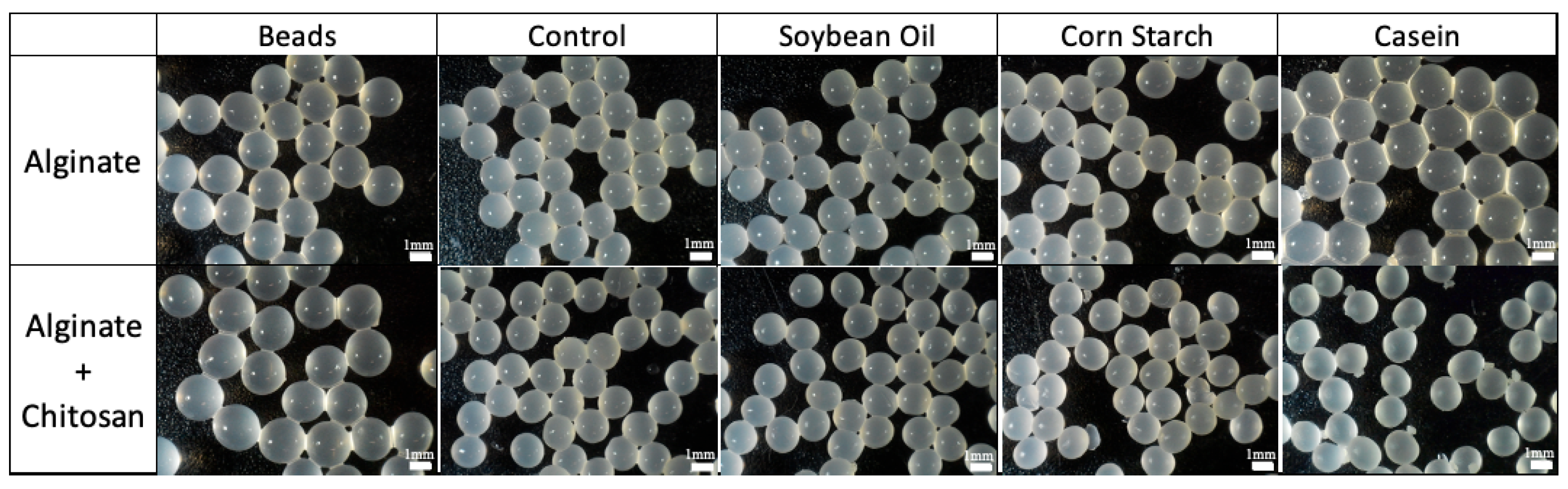

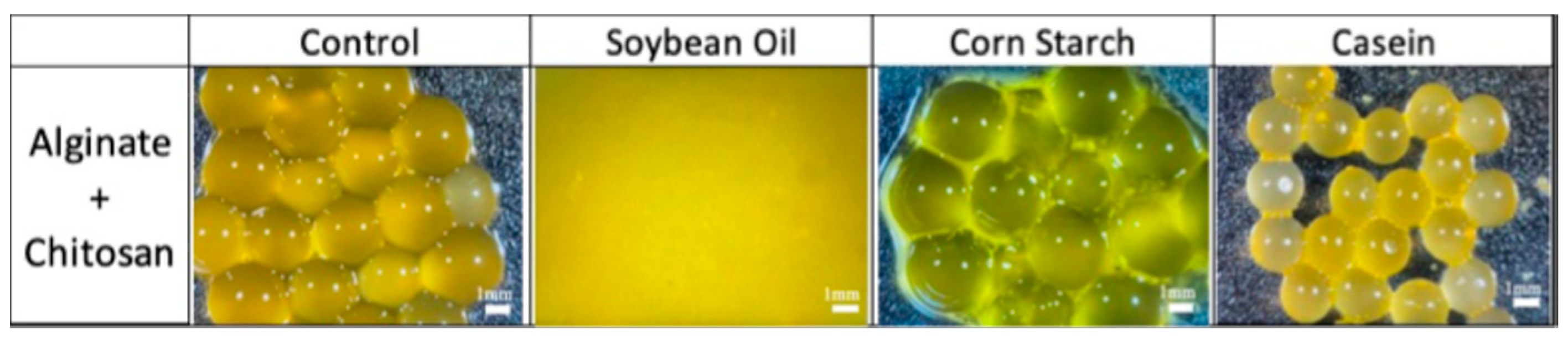

Figure 3 shows microscopic observations of the sample's appearance before and after digestion. With the exception of the alginate beads with casein, beads shrinkage was observed in the other conditions, especially in the chitosan beads digested with casein.

Considering the above results, it is supposed that, to improve the survival rate of probiotics, it would be more effective to simultaneously digest foods with a strong pH buffering effect, such as proteins. Similar effects have been observed in the enhanced stability of probiotics in dairy products, for example, milk [

13,

14], yogurt [

15], and cheese [

16]. Therefore, this strategy could be widely applicable to various types of probiotic capsules. The addition of starch also improved the survival of alginate capsules, indicating the possibility of external protection of food materials other than pH modulation, however, it was believed that the protective effect is not as strong as that of proteins.

Chitosan-coated alginate beads were further studied using SIDM for up to 4 hours to evaluate the impacts of food materials on the simulated intestinal fluid at pH 8.1.

Figure 4(a) shows the survival of LRGG still entrapped in the chitosan-coated alginate beads after 4 hours of SIDM. The results clearly indicate that the addition of food materials significantly affected the viability of LRGG during intestinal digestion. Similar to their impacts in SGDM, the addition of casein and corn starch was found to enhance the survivability of LRGG in the simulated intestinal fluid. Casein provided the highest protection, maintaining viable LRGG at 8.50 ± 0.11 Log CFU/g beads, which is close to the initial cell count of 9.13 ± 0.12 Log CFU/g. Starch maintained the second-highest number of viable LRGG, with approximately 5.81 ± 0.44 Log CFU/g beads, representing a reduction of about 1.5 Log CFU/g from the viable LRGG count of 7.27 ± 0.34 Log CFU/g observed after 2 hours of gastric digestion with corn starch. On the other hand, no viable cells were detected in the presence of soybean oil, as all the chitosan-coated alginate beads were completely dissolved. These findings indicate that casein and starch positively influence the protection of probiotics from bile in intestinal fluid when digested simultaneously with these materials.

Figure 4(b) shows the accumulated number of released LRGG during 4 hours of SIDM. The addition of food materials caused a significant difference compared to the control (p<0.05), except for casein (p>0.05). Although casein increased the survival of entrapped LRGG in both SGDM and SIDM, it did not lead to a greater release of cells during SIDM compared to the control. In contrast, starch led to a higher release of cells, which corresponded to the number of remaining viable cells in the beads. Therefore, it is assumed that the increase in released cells is due to the enhanced survivability of LRGG observed in SIDM. Interestingly, soybean oil resulted in no viable cells after 4 hours, leading to the complete dissolution of chitosan-coated beads during SIDM. This may be attributed to the presence of fatty acids, which is released from triacylglycerols upon lipase-mediated hydrolysis in intestinal juice, that could result in interactions between calcium ions [

17] leading to the rapid breakdown of cross-linked capsules.

As shown in

Figure 4(c), the protective effects of casein are assumed to be due to its pH-modulating ability, which resulted in a slight acidification of the intestinal fluid to 5.78 ± 0.09 from an initial pH of 8.1 over 4 hours. Starch, however, did not significantly alter the pH compared to the control (p>0.05), suggesting that its protective effect is not identical to that of casein, which is primarily attributed to pH modulation. The enhancement of protectability by starch was only confirmed in alginate beads, assuming that starch could work as additional filler to cover the porous structure of alginate beads surface. The effect of viscosity could be also considered for the improvement of survivability as it was confirmed that the high viscosity hinder the diffusion of digestion fluid [

11]. Soybean oil slightly lowered the pH of intestinal juice more than the control, likely due to the hydrolysis of triacylglycerols, which produces fatty acids and glycerol.

Figure 4(d) presents the weight ratio of chitosan-coated beads after 4 hours of SIDM. The addition of casein and soybean oil had significant effects on the morphological change of the beads compared to the control, as casein made the beads maintain compact structure while soybean oil completely dissolved the beads into the intestinal fluid. This observation is further supported by

Figure 5, which shows that casein led to less swelling compared to the control. Given that probiotic inactivation in intestinal fluid is primarily caused by bile exposure, the addition of soybean oil resulted in the complete breakdown of chitosan-coated beads, leading to full inactivation of LRGG due to more challenging exposure of probiotics to bile juice.

4.2. Dynamic In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion with Continuous Juice Secretion and Emptying

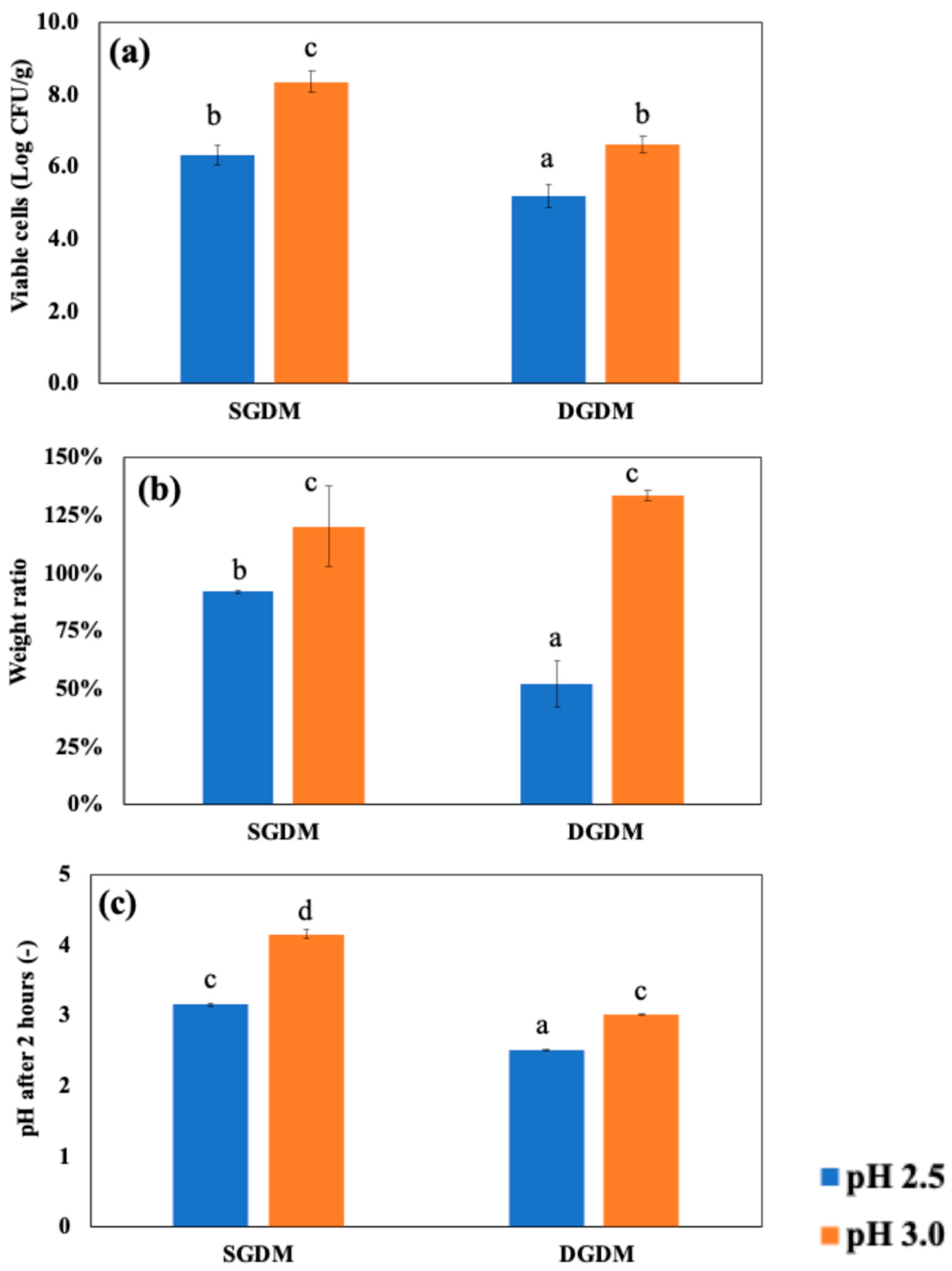

To investigate the impact of dynamic in vitro GI models on entrapped LRGG during 2 hours of gastric digestion, two levels of gastric pH 2.5 or 3.0, which were commonly chosen for dynamic gastric digestion, was set for the testing, and then the observed viable number of cells, weight ratio, and pH shifts were summarized in

Figure 6. The results confirmed that digestion using DGDM significantly reduced LRGG viability in chitosan-coated alginate beads compared to digestion using SGDM at both initial pH 2.5 (5.21 ± 0.32 vs. 6.34 ± 0.27 Log CFU/g beads) and pH 3.0 (6.61 ± 0.23 vs. 8.36 ± 0.28 Log CFU/g beads) gastric juices (p<0.05). The weight ratio analysis showed that beads used in the dynamic model exhibited a significant decrease in weight at pH 2.5, from 92.0 ± 0.9% to 52.0 ± 10.0% of their initial weight (p<0.05), while no significant difference was observed at pH 3.0 (p>0.05). It is generally observed that the lower gastric pH in simulated fluid shows lower viable cells in gastric digestion [

18]. These findings also indicate that the impact of dynamic gastric simulation is greater when the administered pH is lower. The pH values after gastric digestion testing showed that DGDM maintained pH values similar to the initial pH, likely due to the continuous supply of digestive solution (

Figure 6(c)). In contrast, SGDM resulted in higher pH values than the initial pH, likely due to the buffering effects of probiotic capsules. As a result, these findings suggest that evaluating probiotic capsules using static gastric models could lead to an overestimation of viability, as static models mitigate acidity during digestion testing.

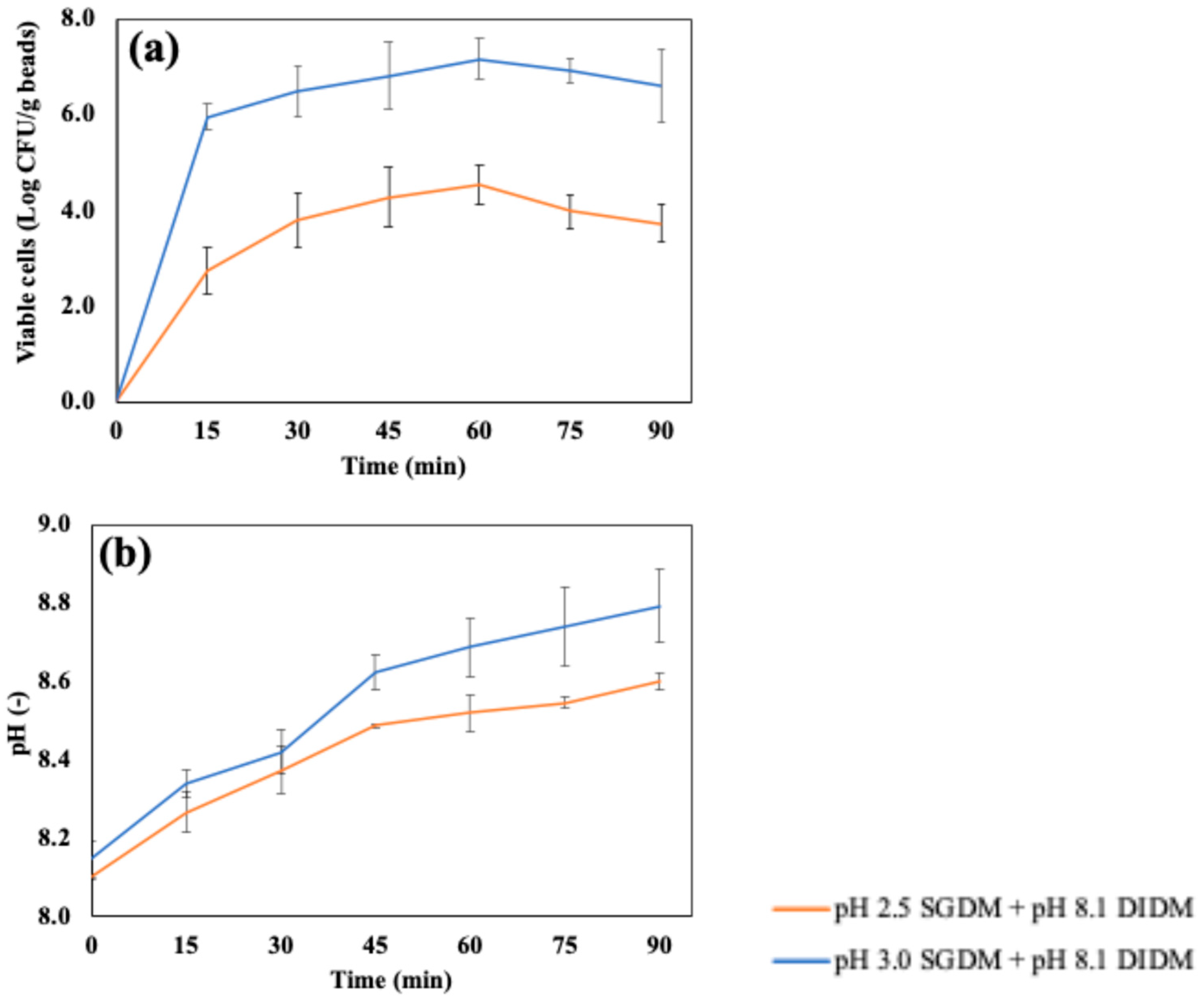

Figure 7(a) shows the accumulated number of cells released in the simulated intestinal fluid using DIDM, which were digested with SGDM at pH 2.5 or pH 3.0 before intestinal digestion. As mentioned in

Figure 4, the chitosan-coated beads retained their shape by swelling after 4 hours of SIDM; however, it was confirmed that the beads were completely decomposed after 60 minutes when digested in DIDM. The number of released cells reached a maximum at 60 minutes in DIDM at both pH 2.5 (4.55 ± 0.40 Log CFU/g beads) and pH 3.0 (7.18 ± 0.44 Log CFU/g beads). Both conditions showed about a 1–2 Log CFU/g reduction compared to the number of cells before intestinal digestion using DIDM, which were 6.34 ± 0.27 and 8.36 ± 0.28 Log CFU/g beads with pre-treatments in the SGDM at pH 2.5 and pH 3.0, respectively. After 60 minutes of DIDM, the number of released cells remained unchanged up to 90 minutes (p>0.05).

Figure 7(b) presents the pH change during DIDM up to 90 minutes. The pH of samples after 90 minutes of DIDM, which were pre-treated with either pH 2.5 or pH 3.0 SGDM, reached 8.79 ± 0.09 and 8.60 ± 0.02, respectively. The pH values of DIDM at 90 minutes and SIDM at 4 hours were very close when pre-treated at pH 2.5 SGDM, suggesting more rapid degradation due to pH in DIDM. In addition, the continuous supply of fresh digestive fluid may have reduced the concentration gradient of the previously decomposed capsules, which could have further facilitated capsule degradation during intestinal digestion.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the critical role of food matrices and simulation of dynamic gastrointestinal digestion for a more in-depth assessment of probiotics in alginate-based capsules. The addition of casein protected the entrapped probiotics during gastrointestinal digestion due to their pH-buffering properties. Starch also exhibited slight protective effects, although its mechanism is expected to be distinct from that of casein. On the other hand, soybean oil suggested the acceleration of capsule breakdown and cell inactivation during intestinal digestion. As these basic food ingredients are commonly included as a building block of food products, these findings suggest that incorporating appropriate food components alongside encapsulated probiotics can further improve or deteriorate their viability and potential health benefits. The comparison between static and dynamic gastrointestinal models indicated more severe damage and release will occur in probiotic capsules, revealing the importance of continuous digestive fluid circulation during digestion studies. Future research should explore the effects of more complex food matrices and products, assessment using more realistic dynamic GI simulators, and thereby the advancement of encapsulation systems to optimize the processing and formulation based on the desired food application.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Toshifumi Udo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Gopinath Mummaleti: Writing – review & editing. Zijin Qin: Writing – review & editing. Jinru Chen: Writing – review & editing. Rakesh K. Singh: Writing – review & editing. Yang Jiao: Writing – review & editing. Fanbin Kong: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture [grant no. 2021-09559].

Data Availability Statement

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: .Further data available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

T. Udo would like to thank the Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO) and Saitama Window to the World Scholarship for their support during his doctoral studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Ouwehand, A.C. A review of dose-responses of probiotics in human studies. Benef. Microbes 2017, 8, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringel, Y.; Quigley, E.; Lin, H. Using Probiotics in Gastrointestinal Disorders. Am. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 2012, 1, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capurso, L. Thirty Years of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG: A Review. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2019, 53, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kathiriya, M.R.; Vekariya, Y.V.; Hati, S. Understanding the Probiotic Bacterial Responses Against Various Stresses in Food Matrix and Gastrointestinal Tract: A Review. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2023, 15, 1032–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajam, R.; Subramanian, P. Encapsulation of probiotics: past, present and future. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2022, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frakolaki, G.; Giannou, V.; Topakas, E.; Tzia, C. Effect of various encapsulating agents on the beads’ morphology and the viability of cells during BB-12 encapsulation through extrusion. J. Food Eng. 2021, 294, 110423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezamdoost-Sani, N.; Khaledabad, M.A.; Amiri, S.; Khaneghah, A.M. Alginate and derivatives hydrogels in encapsulation of probiotic bacteria: An updated review. Food Biosci. 2023, 52, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Călinoiu, L.-F.; Ştefănescu, B.E.; Pop, I.D.; Muntean, L.; Vodnar, D.C. Chitosan Coating Applications in Probiotic Microencapsulation. Coatings 2019, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbassi, G.K.; Vandamme, T. Probiotic Encapsulation Technology: From Microencapsulation to Release into the Gut. Pharmaceutics 2012, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Kong, F. Simulating human gastrointestinal motility in dynamic in vitro models. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 3804–3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Fortner, L.; Kong, F. Development of a Gastric Simulation Model (GSM) incorporating gastric geometry and peristalsis for food digestion study. Food Res. Int. 2019, 125, 108598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, F.P.; Singh, R.K.; Kerr, W.L.; Pegg, R.B.; Kong, F. Total phenolics content and antioxidant capacities of microencapsulated blueberry anthocyanins during in vitro digestion. Food Chem. 2014, 153, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Conceição, L.L.; et al. Survival of Lactobacillus delbrueckii UFV H2b20 in fermented milk under simulated gastric and intestinal conditions. Benef. Microbes 2013, 4, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.; Tachon, S.; Eigenheer, R.A.; Phinney, B.S.; Marco, M.L. Lactobacillus casei Low-Temperature, Dairy-Associated Proteome Promotes Persistence in the Mammalian Digestive Tract. J. Proteome Res. 2015, 14, 3136–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzaal, M.; et al. Functional exploration of free and encapsulated probiotic bacteria in yogurt and simulated gastrointestinal conditions. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 3931–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahtinen, S.J.; et al. Probiotic cheese containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 and Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM® modifies subpopulations of fecal lactobacilli and Clostridium difficile in the elderly. AGE 2012, 34, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroebinger, N.; Rutherfurd, S.M.; Henare, S.J.; Hernandez, J.F.P.; Moughan, P.J. Fatty Acids from Different Fat Sources and Dietary Calcium Concentration Differentially Affect Fecal Soap Formation in Growing Pigs. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praepanitchai, O.-A.; Noomhorm, A.; Anal, A.K. Survival and Behavior of Encapsulated Probiotics (Lactobacillus plantarum) in Calcium-Alginate-Soy Protein Isolate-Based Hydrogel Beads in Different Processing Conditions (pH and Temperature) and in Pasteurized Mango Juice. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 9768152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).