1. Introduction

Maintenance costs can be reduced if measures are taken in good time before critical devices fail. The Intelligent Predictive Decision Support System (IPDSS) applied to condition-based maintenance improves reliability and efficiency of energy systems on ships. Equipment failures can be reduced by early indication of failure, and based on condition diagnostics, repairs should be made and maintenance planned. Timely re-placement of worn parts or systems on which possible malfunctions have been detected enables the planning of service activities with the necessary replacement parts and reduces the accumulation of unnecessary parts in warehouses [

1], [

2]. The diesel engine can be monitored and controlled via the Internet of Things (IoT) platform. Physical presence is no longer required for the operation of diesel generators. The data collection system based on the technology that facilitates communication between devices and the cloud, as well as between the devices themselves, aims to increase the flexibility and optimization of the system [

3]. Remote monitoring of energy systems in real time can avoid system breakdowns and downtime. To identify system problems and malfunctions, expert diagnostic systems are developed based on heuristics and priorities in decision making. Data from marine energy systems are sent via the Internet to experts on land without disrupting maritime operations. Data access must be enabled through a secure remote connection. By introducing automation, failures caused by the human factor were avoided. A well-designed expert system for remote diagnostics and optimization ensures the reliability of the ship's energy systems and extends their service life. Remote monitoring systems already exist and their technical development is being promoted to diagnose and optimise existing and new ship systems. The aim is to make it easier for the crew on board to monitor the parameters so that specialists on land can see the condition of the ship's systems via the Internet and, in communication with the crew, can easily take remedial action if necessary. This has the effect of reducing costs and improving crew efficiency by freeing up crew time for other work on the ship and can potentially lead to a reduction in the number of staff on board as a result of the drive towards autonomous ships. The role of the shore-based experts would be to monitor the parameters and correct the maintenance time according to the condition of the system elements, identify potential problems and fix them in communication with the crew through suggestions and equipment optimization in an appropriate manner [

4].

The example of a remote diagnostic system described in [

5] has improved the level of ship monitoring and the working ability of engineers and increased the level of regulation of the maritime company. This remote diagnosis system for an engine room was developed by comprehensively utilizing the SQL server database, neural network, Inmarsat system, etc., and included data acquisition, data storage, interface, and data transmission. The application results show that the system is helpful for the engineer to know the condition of observed devices in the engine room, good solution for companies for improving efficiency and enable good service.

Further development of remote diagnostics included the monitoring the engine condition using the tribological information such as faults due to wearing of diesel engine components [

6]. The system proposed in this work consisted of an online signal acquisition and a diagnosis model in the service center. Nine wear features were extracted to detect engine faults. In order to select the relatively best feature for online fault detection, the method based on interaction information was used to determine the appropriate indicator. The diagnosis results showed that the proposed system provided a satisfactory online fault diagnosis capability.

Articles [

7] and [

8] present another approach for remote diagnosis of faults in the tribological system of the engine. In [

7], a remote diagnosis technology was developed that use online laboratory analysis for tribological systems. A two-stage fault diagnosis model based on an organising map was created with the oil data from the remote oil monitoring system and the laboratory data. In [

8], the system is improved by using a latest generation wireless communication system to connect the ship and the test laboratory.

The Forcecontrol monitoring software is described in [

9], where smart PLC collected the signals: pressure, temperature, flow, velocity was analysed to control the opening or closing of the various valves and motors. The system could realise video monitoring of devices in machinery room.

A distributed, networked expert system for fault prediction and diagnosis is de-scribed in [

10] and can be applied to various types of prime movers, including diesel engines and gas turbines. The system consists of the on-site data acquisition, the condition monitoring, the communication and the remote expert assistance. The system works with artificial neural networks to perform real-time fault prediction.

In [

11], a new type of remote monitoring and fault diagnosis system (CMFD) for detecting combustion engine faults is presented. The signal of the instantaneous an-gular velocity (IAS) of the engine was transmitted from the ship to a data centre on land. The detection of combustion faults was achieved by a time-frequency spectrum analysis of the decompressed IAS data. The main advantage of the described CMFD remote monitoring system was that the IAS data was sampled at low speed by compressed sensing, which significantly reduced the computational requirements of data trans-mission.

In [

12], an advanced remote monitoring and fleet management system is presented as a technology platform that continuously collects data from remotely operating vessels. All operational data about the ship and its onboard machinery can be uploaded to this shore-based system. The collected data can be categorised into different groups, e.g. GPS-related ship movements, their position, direction and speed; engine operating data: speed, lubricating oil pressure, fuel oil pressure, scavenge air pressure, engine cylinder temperature and pressure, engine speed and exhaust gas temperature. This operating and status data was transmitted in real time to the fleet monitoring server system and then distributed to the logged-in users. This paper proposes a networked live laboratory system that provides a well-defined interface for data access and distributes the live data stream and operational history to researchers around the world who are conducting research in the field of marine propulsion condition monitoring.

To optimise remote monitoring methods and diagnose early faults, a multi-kernel extreme learning machine algorithm was proposed in [

13]. The system can accurately and reliably detect the potential failures.

To improve the current inadequate application of inherent testability for remote control and monitoring systems (RCMS) of ship main engines, [

14] proposes a method for developing RCMS based on microcomputer control and controller area network (CAN) technology, considering the perspective of inherent testability. In the work, the object-oriented hierarchy structure of the framework was introduced, and three relatively interdependent subsystems were included: the remote control subsystem (RCS), the safety protection subsystem (SPS), and the monitoring and alarm subsystem (MAS). For each subsystem, a division of functional units and a module design was carried out, i.e. Line Replace Unit (LRU) and Shop Replace Unit (SRU) designs were performed.

In [

15], a fault detection and diagnosis method combining marine engine expertise and advanced data analysis techniques was proposed. The regression models and dynamic thresholds determine irregularity in engines behaviour.

A further improvement of real-time monitoring is presented in [

16]. The methods for remote detection of faults in piston rings are presented. Support Vector Machine, along with other methods were tested and a good indication of the degradation of the system were concluded.

A particular area of remote monitoring is the monitoring of emission reduction. In the study [

17], a newly proposed system was developed that is able to calculate an engine efficiency, power, vessel's engine speed, fuel consumption, and carbon dioxide emissions based on receiving simple key data such as GPS, speed, fuel flow, thus avoiding obtaining the condition of the vessel with detail data. The system transmits the data via a communication network.

The latest research is in the direction of simulating failures and developing diagnostic expert systems [

18], [

19]. The model described representative engine behavior and was used for studies on engine failure simulation. The presented engine model can be used for optimization and diagnostic purposes.

In this study, an online monitoring system for the diagnosis of the propulsion engine with the possibility of failure prediction is developed. The most important operating parameters of the engine are determined and a system for monitoring the trends of the relevant engine parameters is implemented. An innovative algorithm for detecting possible failures based on a remote monitoring system is proposed. The results obtained by applying the proposed diagnostic system on an operating vessel are presented.

2. Experimental method and setup

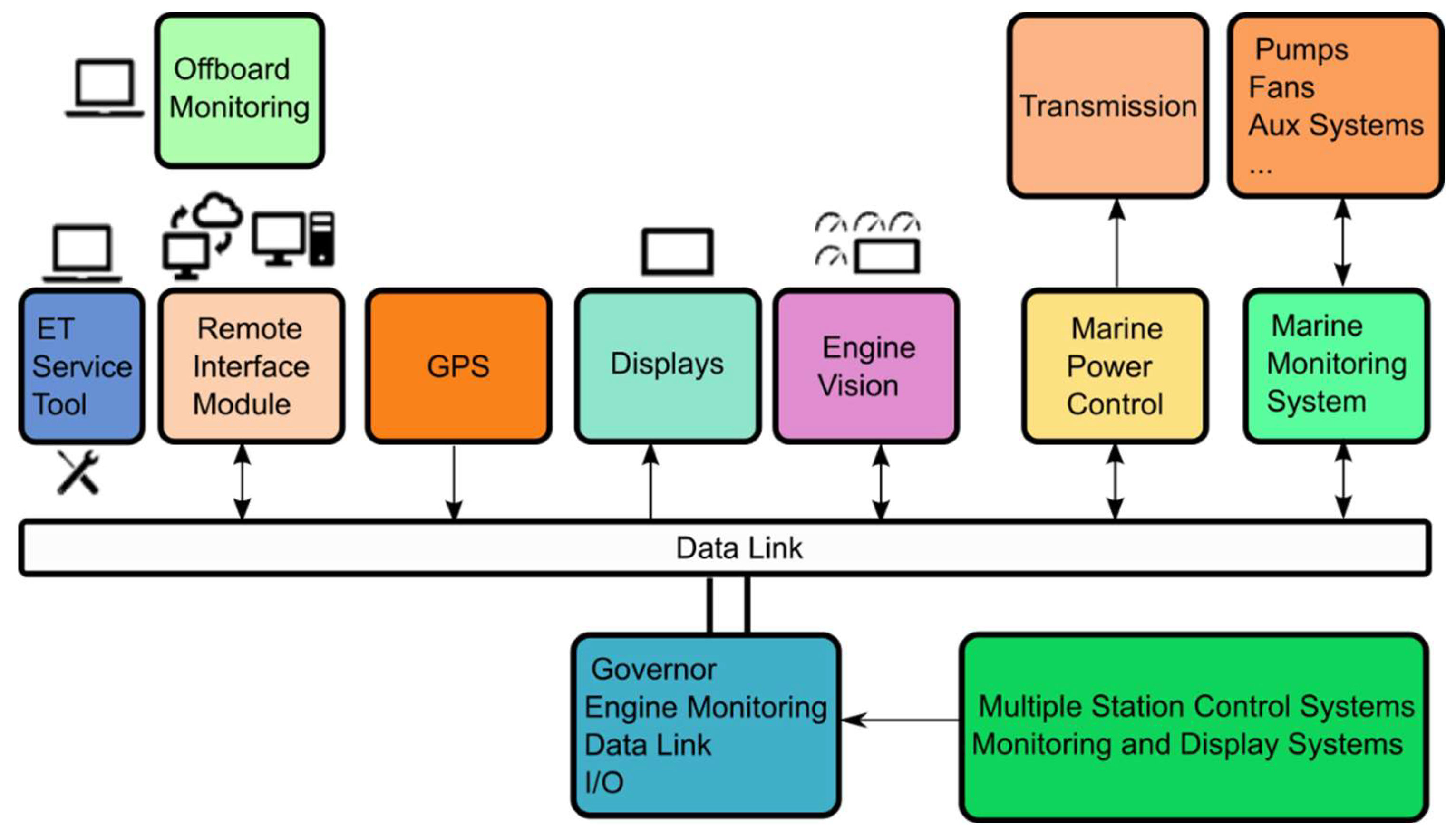

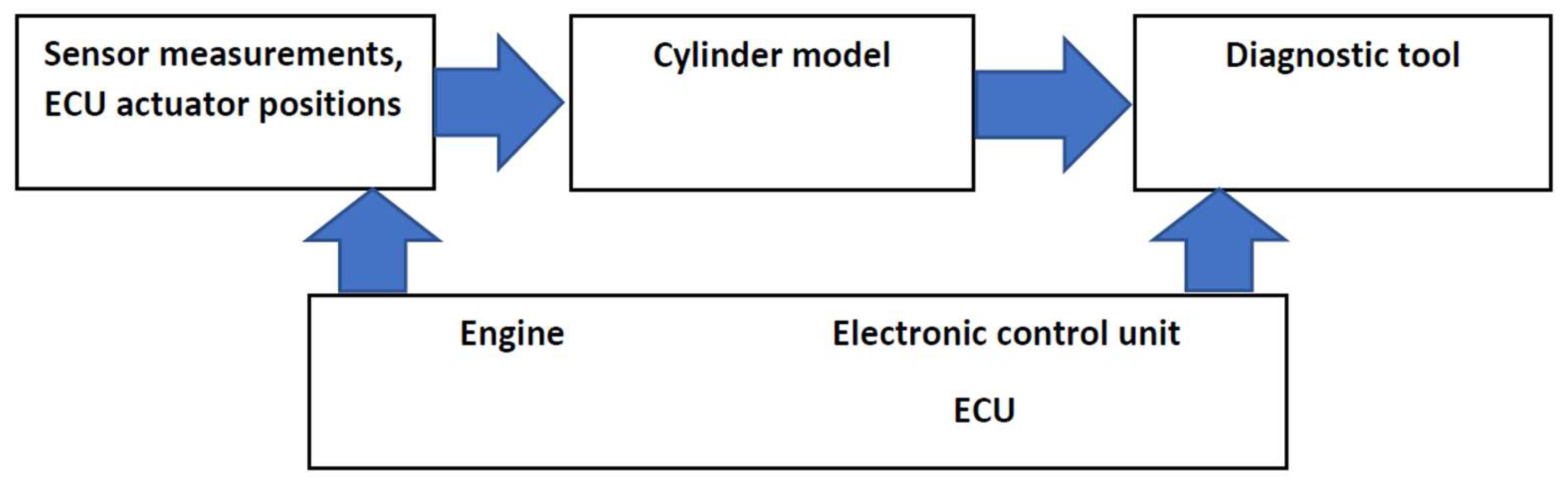

For the experimental research, an expert system with remote monitoring possibility (

Figure 1.) has been developed and implemented on a ferry with four stroke marine diesel engines during their voyages. The system provides online access to key ship parameters. The sensors on board are connected to the monitoring system. The sensors are either wired or wireless and monitor various systems (e.g. engine, battery charge level, fuel tank level, engine room temperatures, battery temperatures, and more). An Internet connection with a secure and encrypted communication is used for sending data to server located in laboratory for heat engines. Expert system installed on server analyses the received data, in order to, for example, predict engine component failures or provide insights into other features of the ship's navigation and exploitation. Engine and ship data are available to the experts with a secured user account accessible via smartphone or computer. The user can grant access to third parties such as maintenance companies to facilitate cooperation with their service providers.

The following advantages and disadvantages of remote monitoring were established during this research. Advantages are:

Using the remote monitoring system, the expert monitors the operation and operating parameters of the propulsion system and eliminates the possibility of problems.

Knowing the location and cause of the fault, the service personnel who come to repair the fault bring the necessary materials and equipment with them, which reduces the costs and time required for the repair.

By giving recommendations for plant optimization, the expert can reduce plant operating costs.

The expert plans maintenance based on the current state of the equipment.

The ship owner has insight into the cause of the failure and receives information and expert recommendations that can be implemented on other ships in the fleet.

Registration companies, insurance companies and inspectors have an insight into how the maintenance was carried out, which enables the assessment of their quality.

It is possible to monitor exhaust gas emissions, and based on this, possible emissions reduction solutions can be drawn.

Disadvantages of remote monitoring:

The diversity of ship systems makes it difficult to apply a universal monitoring system.

Complex implementation of determination, filtering and presentation of in-formation.

Figure 2.

Remote monitoring system.

Figure 2.

Remote monitoring system.

The purpose of monitoring is based on insight into the current state of the device, performance and efficiency of the system, workload, preventive and corrective maintenance, reduction of time for detecting and resolving faults, and protection when parameters are changing significantly. This enables a timely reaction due to observed changes in parameters, which prevents the occurrence of malfunctions. Performing diagnostics ensures the technical correctness of the engine and its system. By continuously recording certain important parameters, it is possible to adjust the correct operation of the ship's propulsion system, and determine the optimal timing to perform the appropriate type and scope of maintenance.

The engine manufacturer determines the most important engine parameters that must be constantly monitored. The standard for collecting the mentioned parameters from the engine's electronic control unit is CAN J1939.

The main monitored parameters are:

Atmospheric pressure,

Mean indicated pressure,

Exhaust gas pressure,

Scavenging air pressure,

Back pressure of exhaust gases,

Inlet air filter pressure difference,

Engine rpm,

Power,

Exhaust gas temperature,

Charge air temperature,

Air temperature before the turbocharger,

Cooling water temperature before and after intercooler,

Turbocharger speed.

These parameters are monitored using CAN protocol with industrial standard J1939 for data transfer. The sensors are for pressure, temperature and flow. There are also important speed/timing sensors so important that there are two primary and secondary. All sensors send the measured signal to the engine control unit (ECU). The boost pressure sensor is on the intake manifold. The fuel pressure sensor is positioned along the fuel rail or line. The coolant temperature sensor is located near the thermostat housing or in the engine block. The oil pressure sensor is positioned on the engine block or near the oil filter housing. The exhaust gas temperature sensor is placed in the exhaust manifold or pipe.

3. Analyses of the propulsion engine parameters

By processing the collected engine operation data, state diagnostics are performed. An example of diesel propulsion system diagnostics has been implemented on a ferry sailing on the daily Split-Supetar route (distance 9 nautical miles).

Jupyterlab was used for the data processing and model development because it is open-source software and has many libraries available for data processing and research. Also, some third-party services are propulsion machinery is engaged, it is necessary to filter the data related to sailing. In this paper, the data are divided into groups that correspond to one-way ferry sailing on a given route between the mainland and the is-land. Only the filtered data was analyzed out by using the Python Data Analysis Library (pandas). Each individual measurement is read as a pandas Data Frame from a database for data processing, searching and filtering on data import. Data is checked for continuity in timestamp and out of range values. A ferry that sails on the same route was analyzed. The measurements themselves refer to more than 40 different parameters from various sensors, but some values are calculated on data import like travelled distance from available GPS coordinates, brake power from load percentage and also brake specific fuel consumption. Each measurement is then stored in a faster search format or in a SQL database, For the purposes of the test, we used SQLite or simplicity and for compatibility with SQL. Following data have been selected: engine speed, boost pressure, volumetric fuel consumption, percentage of load at current speed.

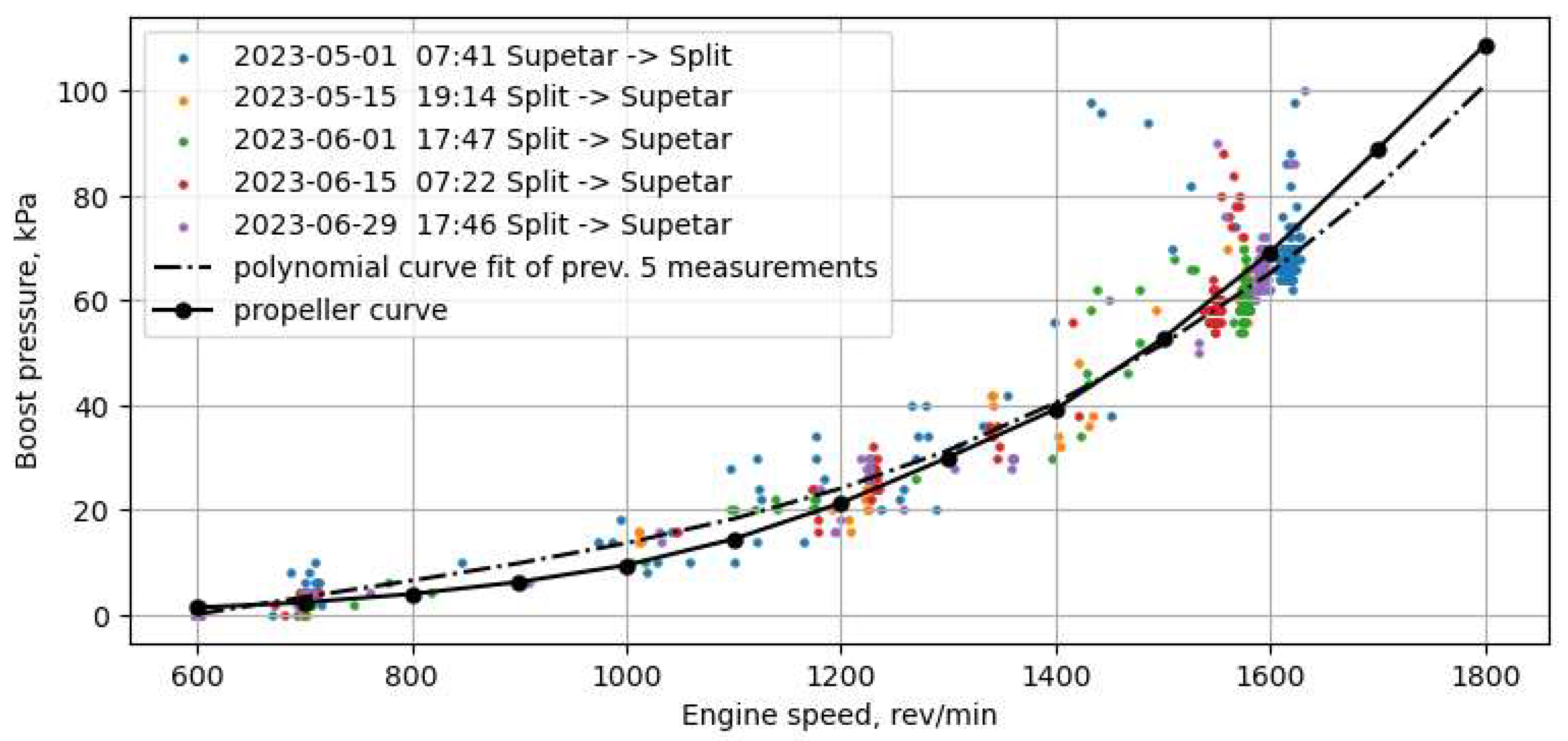

The analysis included the creation of trend diagrams to present distribution of mini-mum, median and maximum values of each parameter of all measurements. Also, measurements data are compared with data obtained during sea trial test (load according to propeller curve). Boost pressure in function of engine speed is shown in

Figure 3.

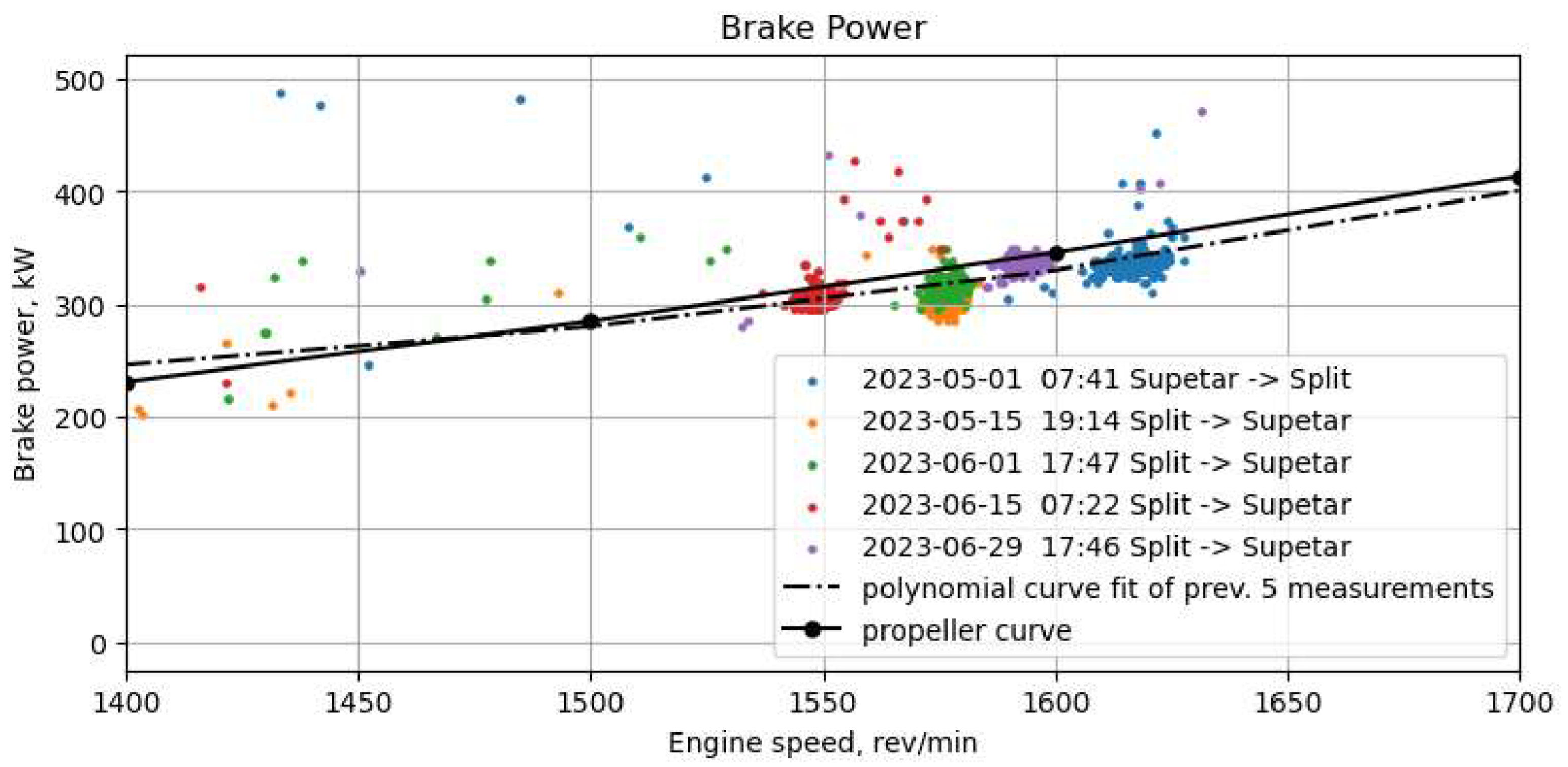

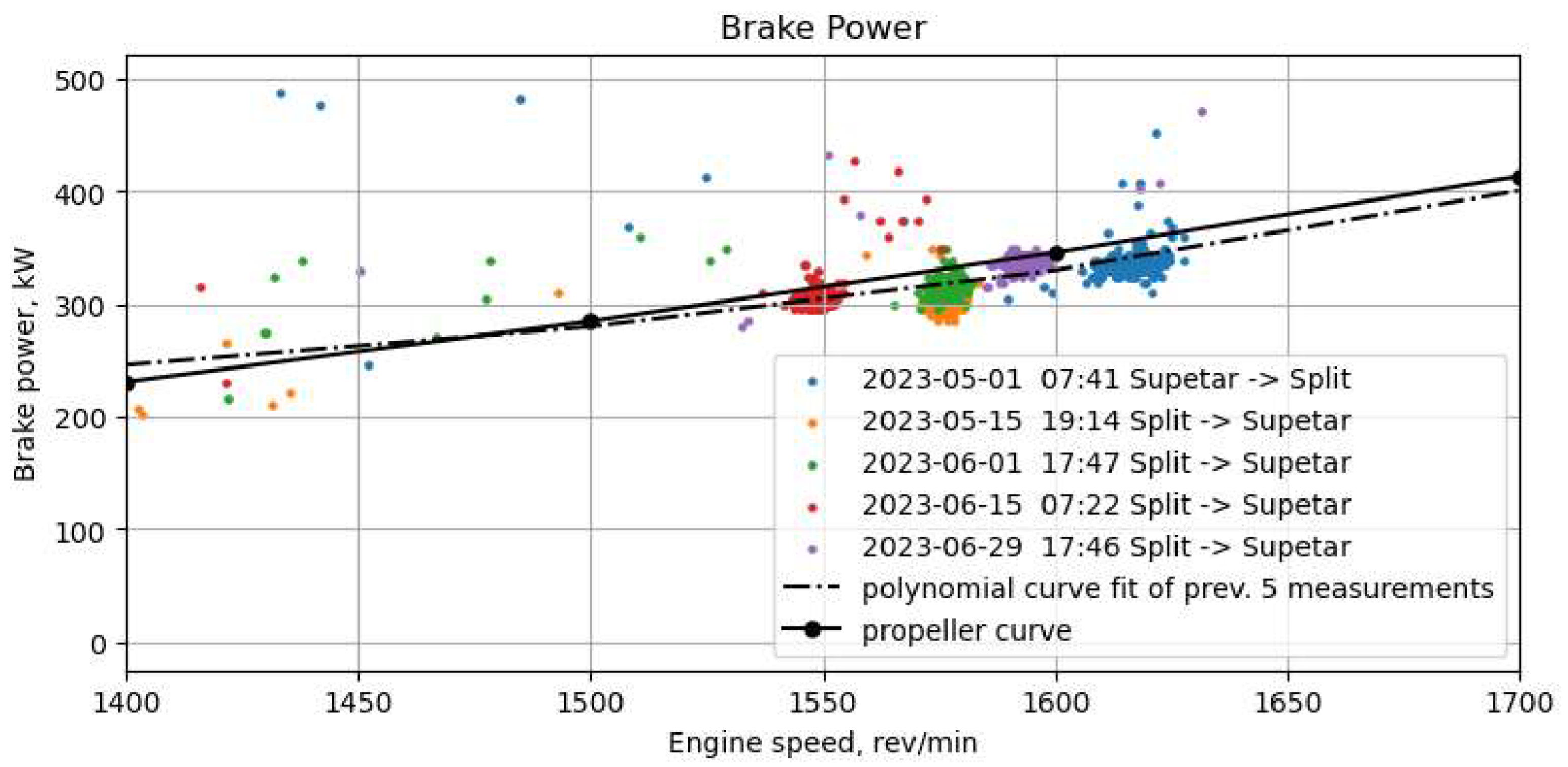

From the diagram in

Figure 3. and 4. it can be seen that during the manoeuvre in the port and the acceleration of the ship, the engine works with a slight overload, while during the voyage under full load, the engine works with load according the propeller curve.

Figure 4.

Brake power dependency on Engine speed. Dash-dotted curve represents fitted curve of measurements combined. Solid line is fitted curve of engine test data on propeller curve.

Figure 4.

Brake power dependency on Engine speed. Dash-dotted curve represents fitted curve of measurements combined. Solid line is fitted curve of engine test data on propeller curve.

The figure 4. shows brake power dependency on the engine speed. The data points in different colours represent different set of measurements. Each trip has a characteristic speed that was maintained during navigation, which probably depended to a significant extent on weather conditions.

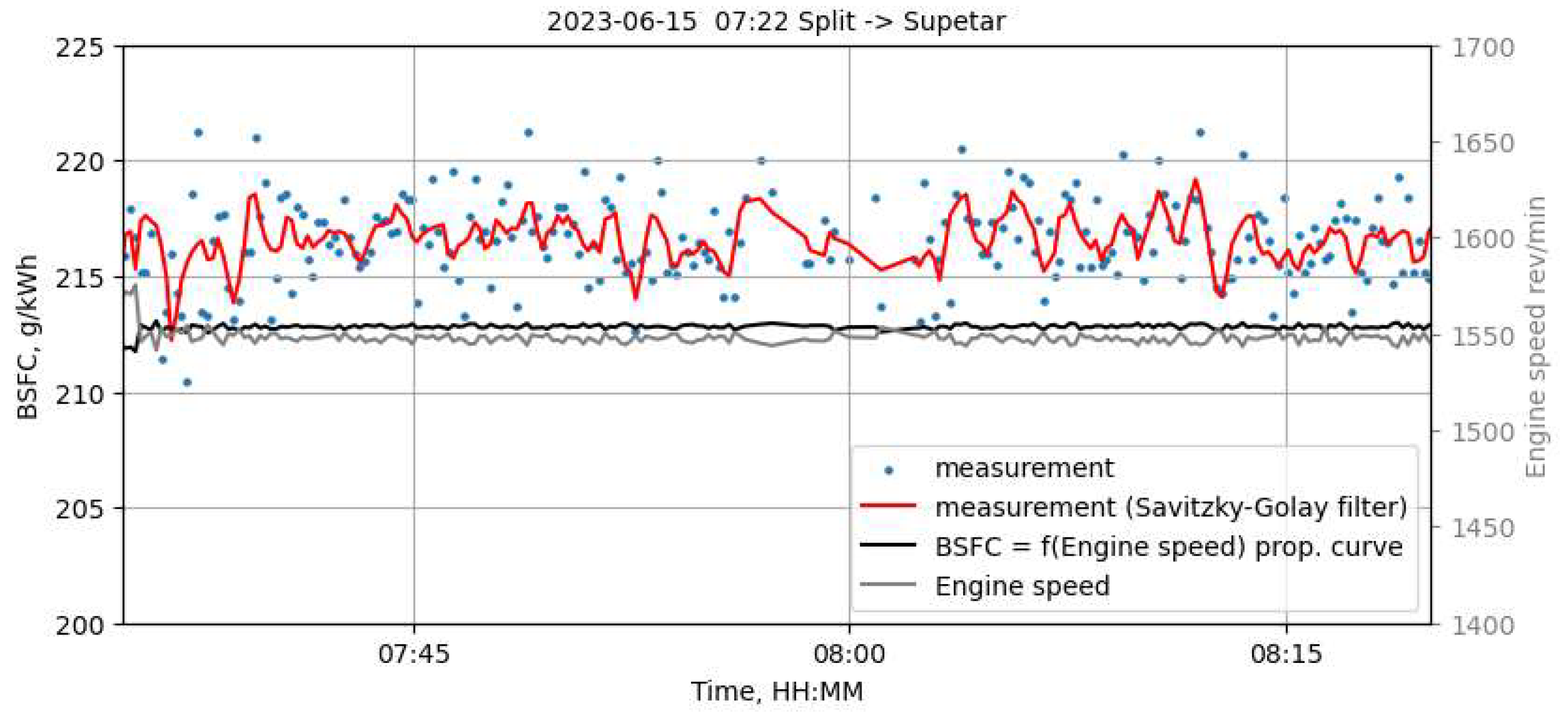

Figure 5.

Brake specific fuel consumption dependency on engine speed.

Figure 5.

Brake specific fuel consumption dependency on engine speed.

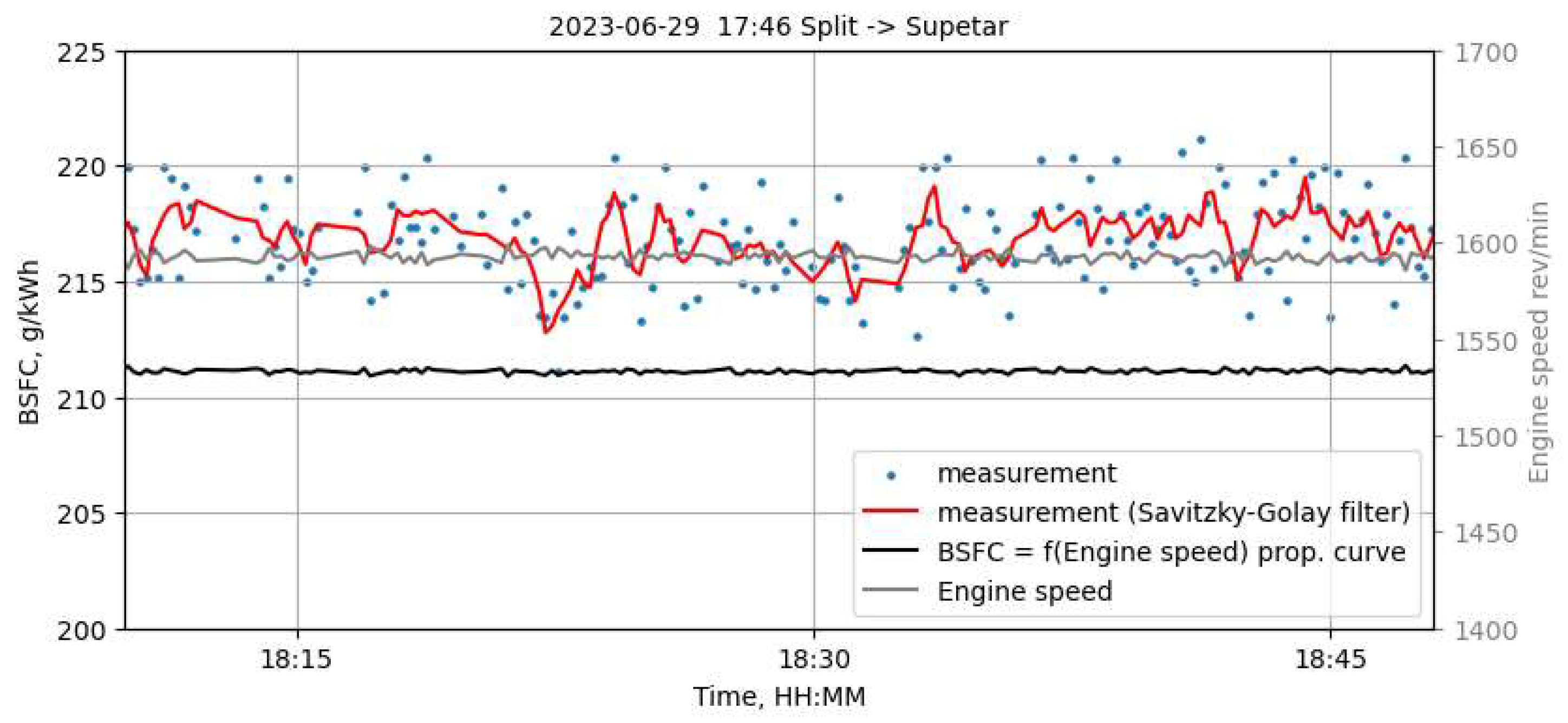

The figure 5. shows brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC) dependency on the engine speed. The BSFC is higher than recommended by the propeller curve, which indicates that it has the potential to optimize engine performance and reduce fuel consumption.

The grey curve represents the current engine speed, the black curve represents BSFC for engine driven at the propeller curve, and the red curve represent actual measured BSFC

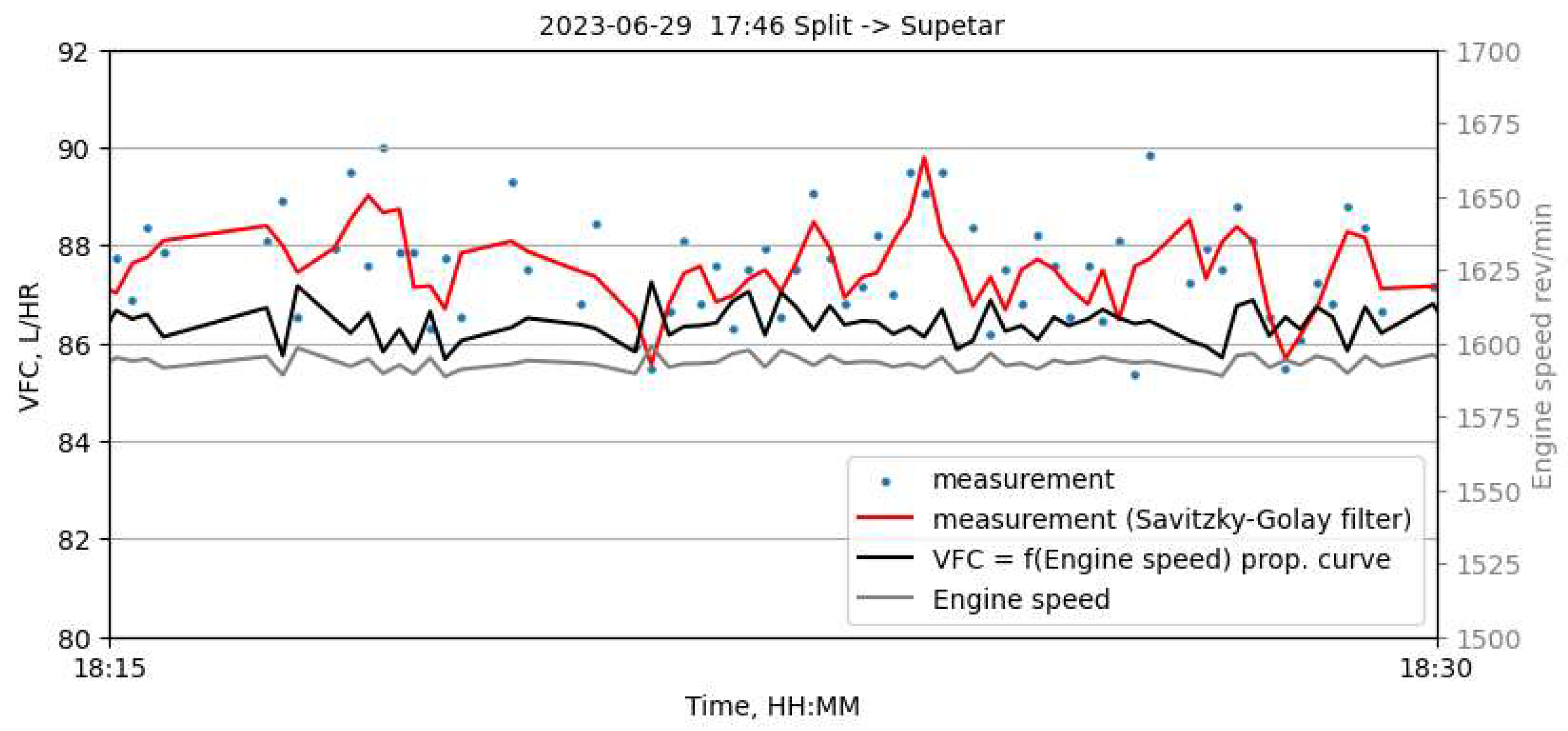

Figure 6. shows brake-specific consumption during ferry navigation. The Savitz-ky-Golay filter is applied to measurement data points to better visualize trends. The curve shows constant changes in consumption because the engine does not work with a continuous load. The load on the engine is constantly changing in order to maintain the direction of the ferry, especially in rough seas and bad weather conditions.

Figure 6.

Brake specific fuel consumption on ferry route in one direction (1. Examp.).

Figure 6.

Brake specific fuel consumption on ferry route in one direction (1. Examp.).

There is another measurement presented in

Figure 7. in which the engine speed is different. Data points are more scattered than in previous measurement, and engine speed is lower. Larger changes in fuel consumption are caused by changes in engine load due to bad weather conditions and rough seas.

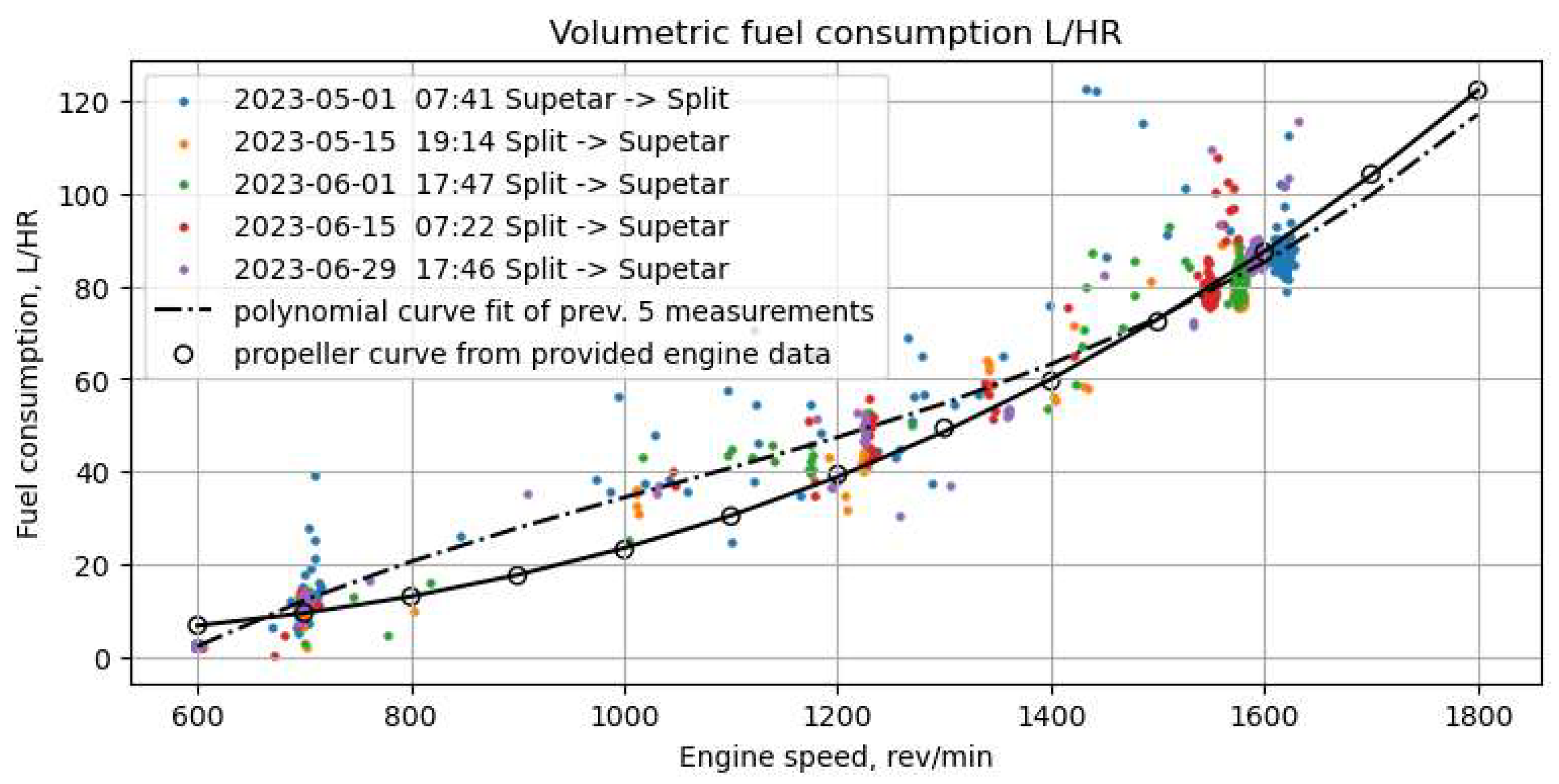

The

Figure 8. shows fuel consumption dependence on engine speed for all speed ranges where brake power is produced. From the diagram of specific fuel consumption, it can be seen that the engine works without load and the specific consumption is lower under standard sailing conditions at cruising speed.

On the diagrams in

Figure 9, it can be seen that the increase in ship speed is accompanied by the current fuel consumption curve. This indicates that sudden changes in direction and an increase in the number of revolutions of the engine significantly affect the economical driving of the boat.

4. Fault Simulation

During the research, models were developed and failures simulated on a marine engine [

19] . Here, only an example of simulation of failures on the air and exhaust system will be given. The simulation of faults in the air and exhaust gas systems of the four-stroke marine engine model is examined. By utilizing sensor data from critical system components, the research investigates airflow resistance and leakage scenarios. The results demonstrate characteristic changes in pressure and temperature under varying fault conditions, providing a foundation for fault detection and diagnostics. Modern electronically control marine engines, are equipped with advanced sensors to monitor key operational parameters. This study focuses on simulating two primary fault types: blockage in air filters and air coolers and leakages in the air and exhaust systems. The analysis aims to elucidate the impact of these faults on engine performance.

4.1. Simulation of Air Filter and Cooler Blockages

4.1.1 Methodology

Blockages were simulated by increasing the frictional resistance multiplier in air filter and cooler components, leading to pressure drops as defined by the equation:

where:

pressure drop,

friction factor (function of Reynolds number),

L pipe length,

pipe diameter,

air density,

kinematic viscosity.

where B is the frictional resistance multiplier.

4.1.2 Results

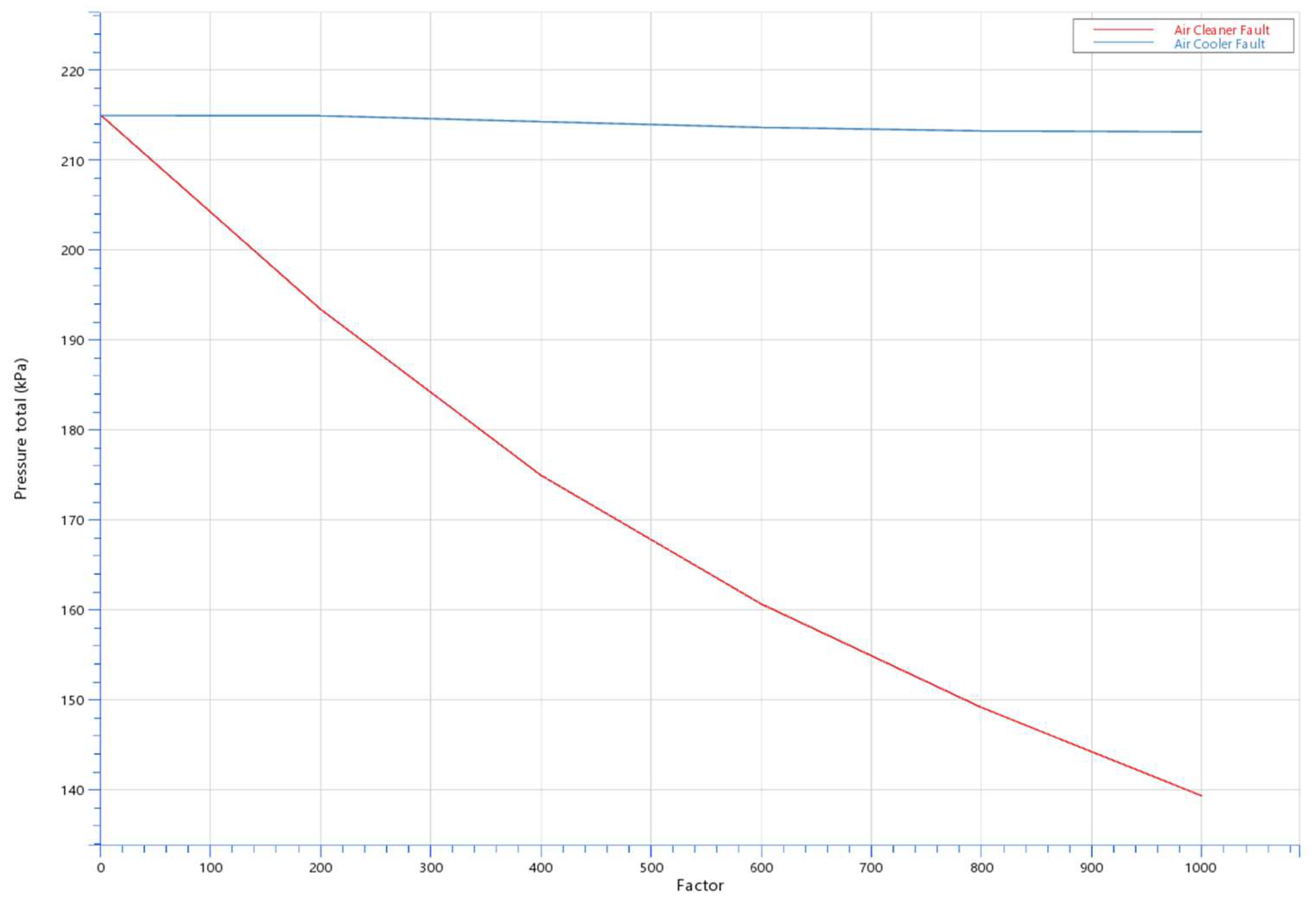

Figure 10 illustrates intake manifold air pressure drop as a function of severe clogging. The red curve represents air filter blockage, with values ranging from a clean filter (factor 0) to a fully blocked filter (factor 1000). The blue curve shows the pressure drop due to air cooler blockage.

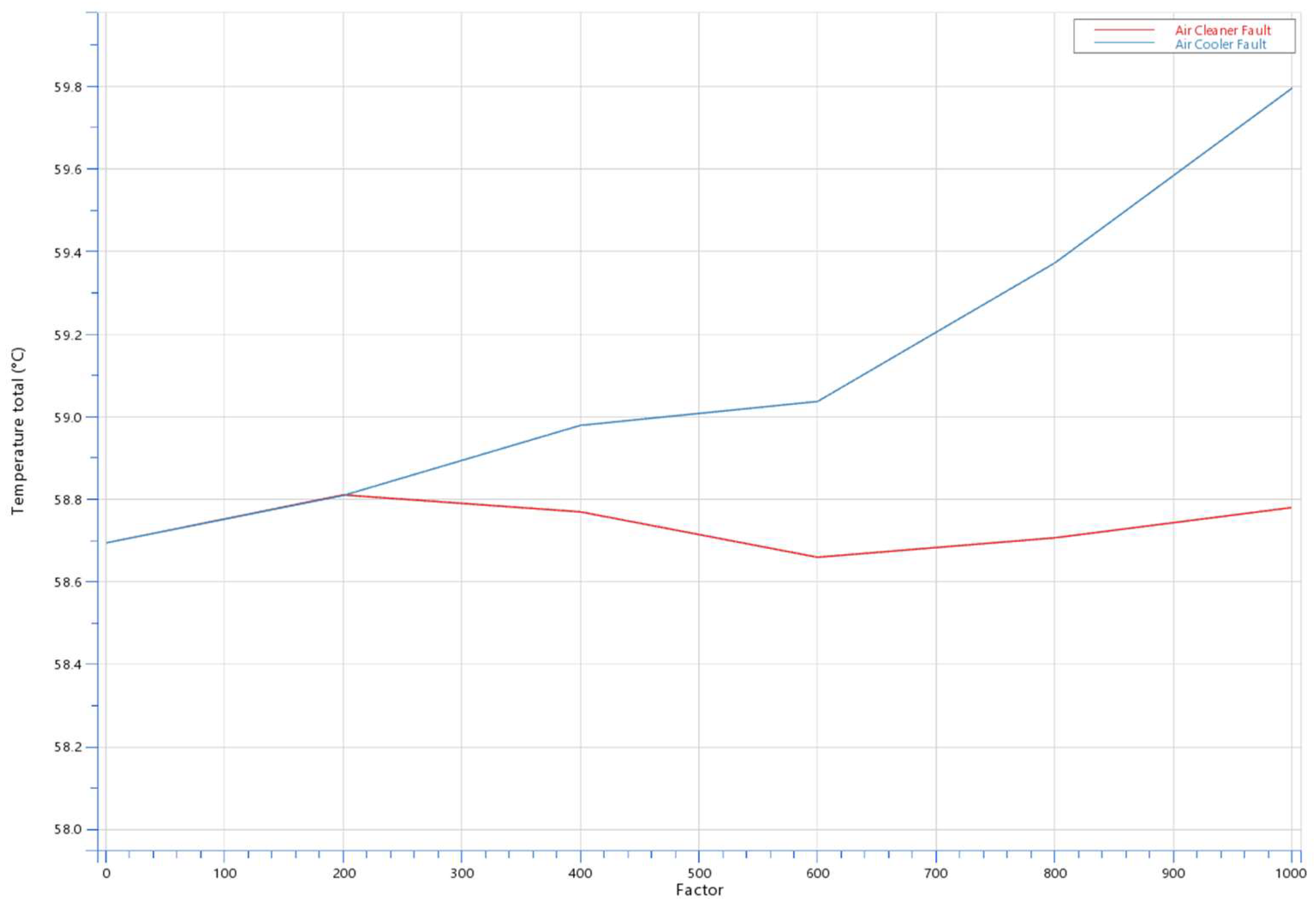

For temperature,

Figure 11 shows minimal variation during air filter blockage. In contrast, cooler blockage significantly affects intake manifold temperature.

4.2. Simulation of Air and Exhaust System Leakages

4.2.1 Methodology

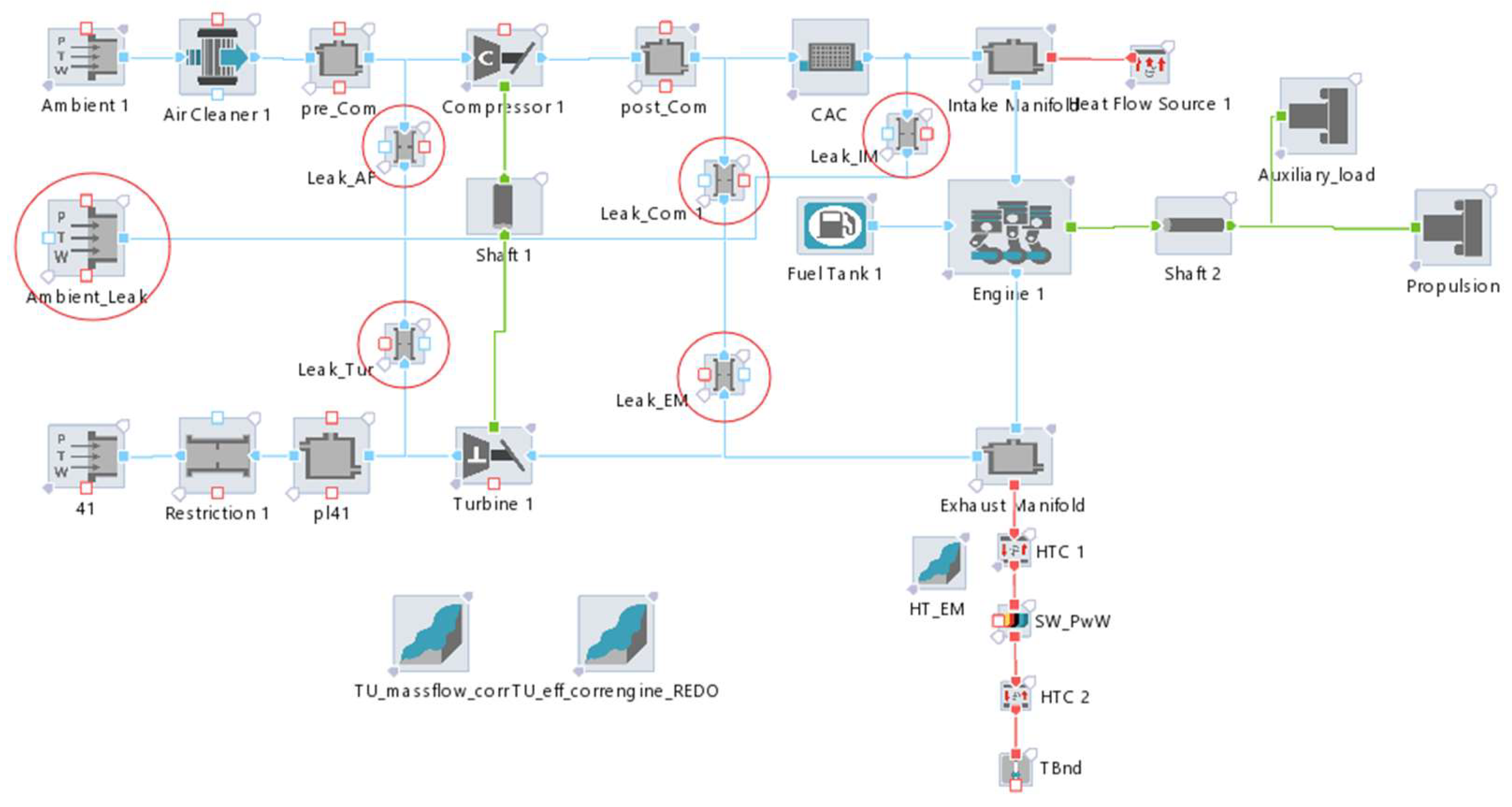

Leakages were simulated by introducing restrictions in the high speed four stroke engine model to simulate fluid leakage (

Figure 12). A restriction represents a narrowed pipe section, defined by its cross-sectional area. The leakage factor ranges from 0 (no leakage) to 1 (maximum leakage). Restrictions were placed at the following locations: Leak_AF: air filter; Leak_Com: compressor; Leak_IM: intake manifold; Leak_EM: exhaust manifold; Leak_TU: turbine.

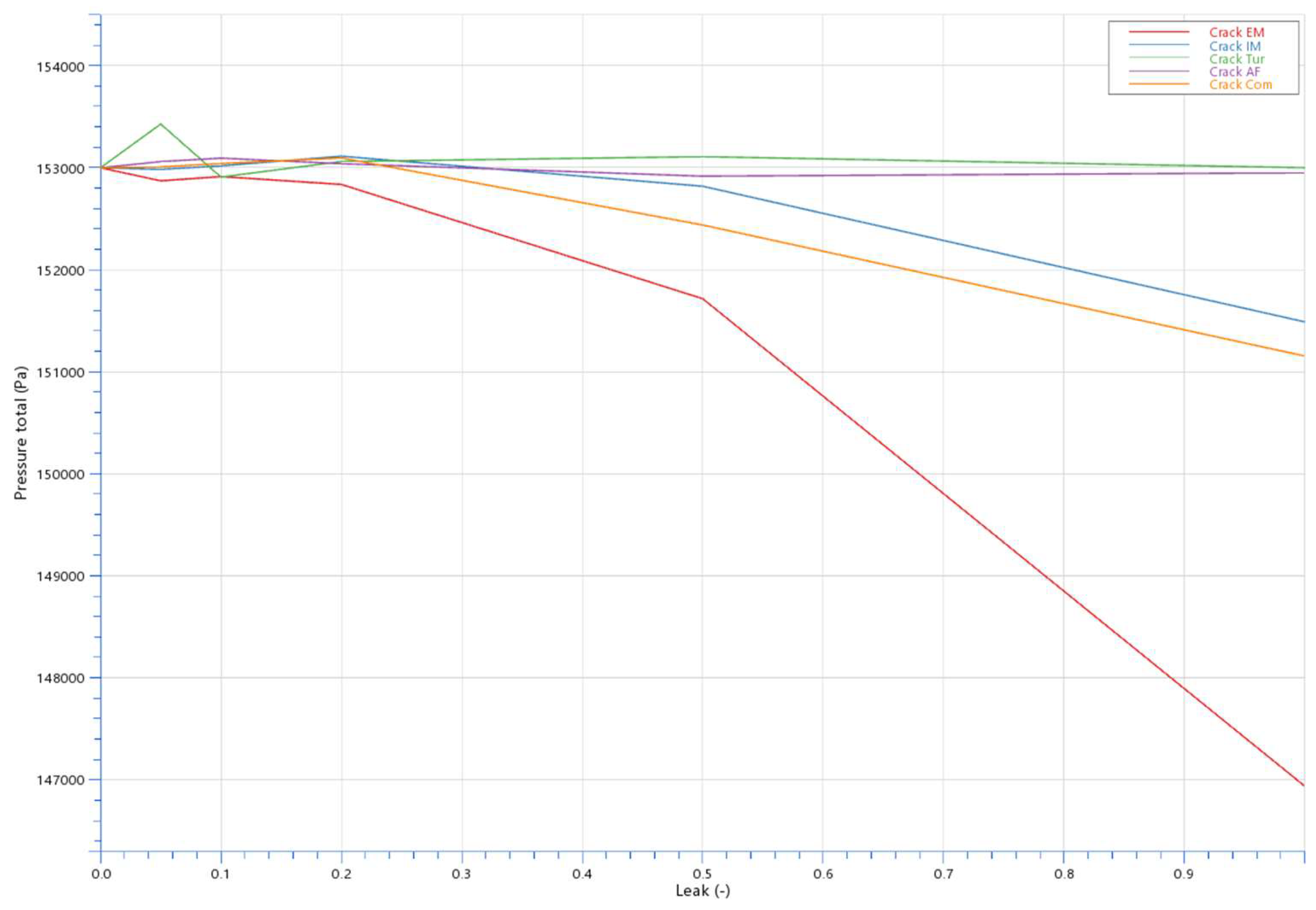

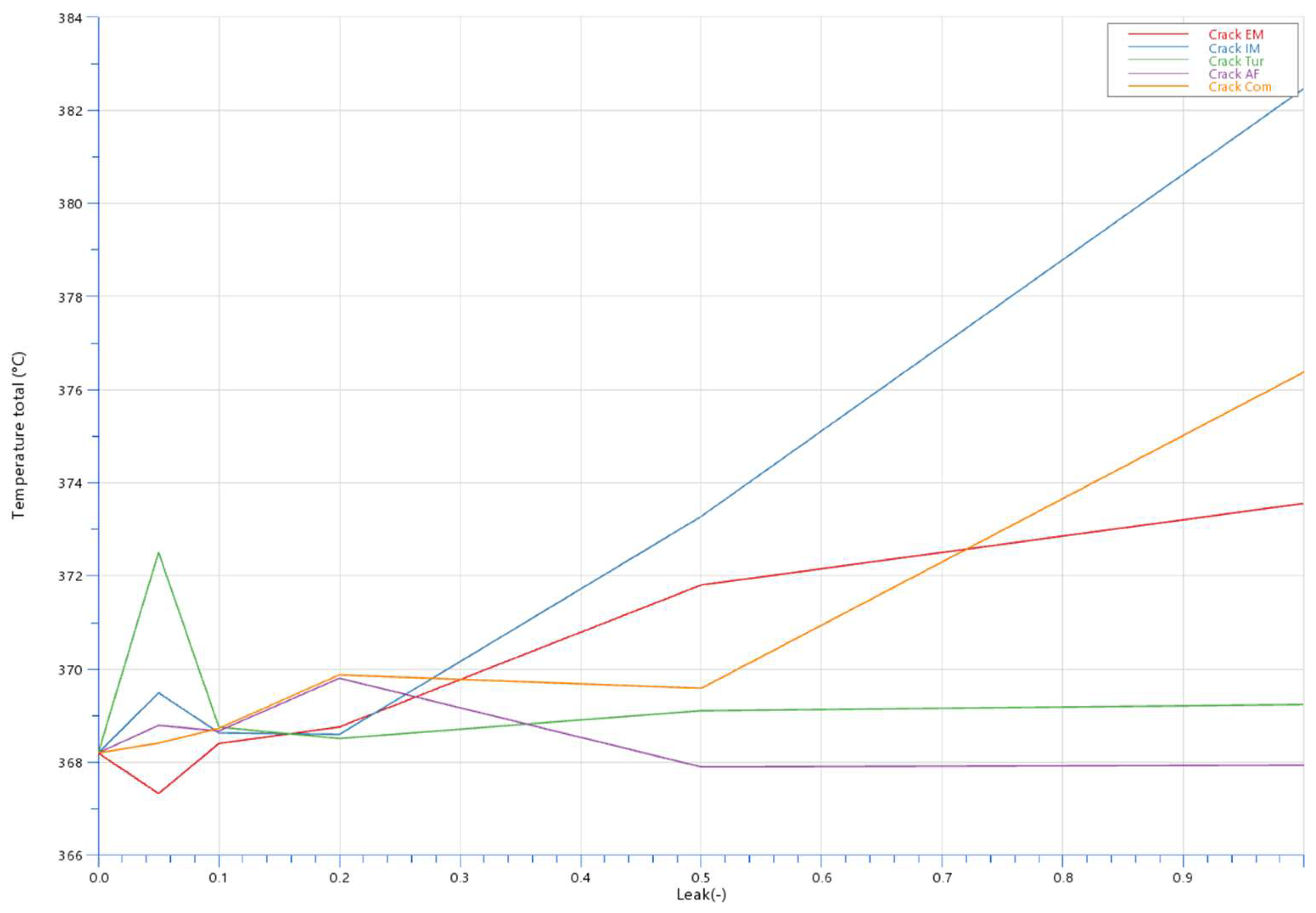

4.2.2 Results

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 display the effects of leakages on pressure and temperature at various points. For instance,

Figure 13 shows overlapping pressure values for compressor and intake manifold leakages, while

Figure 14. highlights temperature deviations.

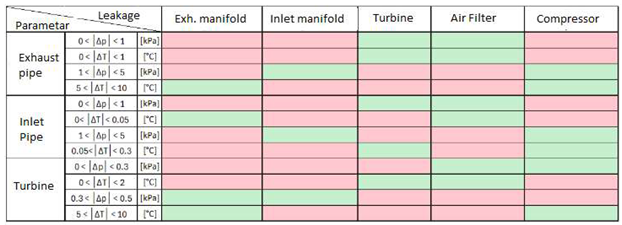

Table 1 presents the example of diagnostic matrix, detailing parameter intervals for maximum and minimum leakage factors. Green highlights indicate compliance with interval thresholds, while red indicates non-compliance. The diagnostic matrix helps diagnose specific faults by matching sensor patterns to characteristic sequences.

The results underscore the importance of diverse sensors and measurement points in accurately describing faults. By correlating fault progression with sensor data, the diagnostic matrix facilitates rapid identification of leakage locations.

From the results presented and the analysis carried out of the remotely monitored parameters of the electronically controlled marine engine in operation, it is clear that there is room for improvement in diagnostics, efficiency, reduction of fuel consumption and emissions. Especially in the ferries tested, which have a flat bottom to be able to dock in a port with shallow seas and need to maintain the ship's direction in rough seas and bad weather. The only way to improve this is to install a system for continuous remote monitoring of key engine parameters in real time while the vessel is in operation. It is necessary to diagnose the condition of the engine in time, determine the parameters that need to be corrected and react quickly to optimize the operation of the engine for these operating conditions. To achieve this, appropriate measuring equipment (to obtain relevant data) and expertise are required for quick conclusions and actions. The whole problem is further complicated by the fact that on smaller ferries (such as the one studied) mostly four-stroke engines are installed, for which we have less measurement parameters (compared to large two-stroke engines, where the pressures in the cylinders are necessarily indicated and the exhaust emissions of individual cylinders are measured), and conclusions must be drawn on the basis of the available measurement parameters. It is necessary to have meteorological data and the conditions at sea and to put everything into context. In this research, a self-developed measurement system was used for data acquisition, processing and transmission. The next phase of our research is to install additional measurement instruments on the observed energy system itself to gain a better insight into the current state, to create a digital twin of the observed propulsion system and to include meteorological data and sea conditions in the analyses.

5. Conclusions

A remote data acquisition system was implemented for the diagnosis of marine propulsion engines on a ferry during normal voyages. When analyzing the data obtained with the system for remote monitoring of ship's energy, an algorithm was developed that enables the monitoring of the most influential parameters and indicates the possibility of malfunctions. Operating modes, data transmission protocols and technical data are presented. Based on the monitoring of the relevant engine operating parameters and comparison with the reference values obtained from the manufacturer, diagnostics were carried out and possible causes of deviations were indicated. In case of an irregularity, warnings and recommendations for eliminating the cause of the fault are issued. During the research carried out on the ferry, which operated regularly on the same route over a period of two months, fluctuations in loading and fuel consumption were detected, indicating the significant influence of weather conditions on engine performance. Analysis of the data collected also showed that more frequent load changes occurred on some trips, caused by a sudden change in engine speed. This observed phenomenon leads to an increase in fuel consumption and its cause is to be investigated as part of further research An example of fault simulation on a model of a marine engine and an example of a diagnostic matrix are also given. The research presented in this paper will serve as a basis for future research, which will focus on the implementation of an expert system for the diagnosis and optimization of the marine hybrid propulsion system.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, O.B., V.P., T.M., G.R., T.V., N.R., M.J., B.L., K.B.; methodology, V.P., T.M., G.R., N.R., M.J., B.L.; software, , O.B., G.R., T.V.; validation, O.B., V.P., T.M., G.R., T.V., N.R., M.J., B.L., K.B.; formal analysis, O.B., V.P., T.M., G.R., T.V., N.R., M.J., B.L., K.B.; investigation, , O.B., V.P., T.M., G.R., T.V., N.R., M.J., B.L., K.B.; resources, O.B., V.P., T.M., G.R., N.R., B.L., K.B.; data curation, V.P., T.M., G.R., T.V., N.R., M.J., B.L., K.B.; writing—original draft preparation, , O.B., V.P., T.M., G.R., T.V.; writing—review and editing, V.P., T.M., G.R., N.R., M.J., B.L.; project administration, G.R., N.R., T.V.; funding acquisition, G.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This work has been fully supported by Croatian Science Foundation under the project: HRZZ IP-2020-02-6249

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are reported in the paper figures and tables.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yam R.C.M.; Tse P.W.; Li. L.; Tu P.: Intelligent Predictive Decision Support System for Condition-Based Maintenance, International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 17, Springer-Verlag London Limited, 2001.

- Maulidevi, N.U.; Khodra, M.L.; Susanto, H.; and Jadid, F. Smart online monitoring system for large scale diesel engine, Smart online monitoring system for large scale diesel engine, IEEE, 2014.

- Chandra, A.A.; Jannif, N.I.; Prakash, S.; Padiachy, V. : Cloud Based Real-time Monitoring and Control of Diesel Generator using IoT Technology. 20th International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS), Sydney, NSW, Australia, 11–14, 2017.

- Jurić, Zdeslav; Kutija, Roko; Vidović, Tino; Radica, Gojmir: Parameter Variation Study of Two-Stroke Low- Speed Diesel Engine Using Multi-Zone Combustion Model // Energies (Basel), 15 (2022), 16; 5685, 6099. [CrossRef]

- Song, XG (Song, Xingang); Ma, AJ (Ma, Aijun); Ma, Q (Ma, Qiang); Zhang, YB (Zhang, Yibin), The design of remote fault diagnosis system in engine room, advanced building materials and sustainable architecture, PTS 1- 4 Book Series: Applied Mechanics and Materials Volume: 174-177 Pages: 1971-1976 DOI: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.174-177.1971, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Yan, XP (Yan, Xinping); Li, ZX (Li, Zhixiong); Yuan, CQ (Yuan, Chengqing); Guo, ZW (Guo, Zhiwei); Tian, Z (Tian, Zhe); Sheng, CX (Sheng, Chenxing), On-line Condition Monitoring and Remote Fault Diagnosis for Marine Diesel Engines Using Tribological Information, 2013 Prognostics and health management conference (PHM) Book Series: Chemical Engineering Transactions Volume: 33 Pages: 805-810. Published: 2013. [CrossRef]

- Xu, XJ (Xu Xiaojian); Yan, XP (Yan Xinping); Zhao, JB (Zhao Jiangbin); Sheng, CX (Sheng Chenxing); Yuan, CQ (Yuan Chengqing); Ma, DZ (Ma Dongzhi), Remote Fault Diagnostic Model for Tribological Systems in Marine Diesel Engine with Two-level Self-organizing Map Network, Proceedings of 2014 prognostics and system health management conference (PHM-2014 HUNAN) Book Series: Prognostics and System Health Management Conference, pp: 261-265, 2014.

- Yan,XP(Yan, Xinping); Sheng, CX (Sheng, Chenxing); Zhao, JB (Zhao, Jingbin); Yang, K (Yang, Kun); LI, ZX (Li, Zhixiong), Study of on-line condition monitoring and fault feature extraction for marine diesel engines based on tribological information, Proceedings of the institution of mechanical engineers part o-journal of risk and reliability Volume: 229 Issue 4 Special Issue SI, pp. 291–300. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J (Chen, Jin); Liu, SJ (Liu, Shijie); Li, Q (Li, Qiao); Ning, XB (Ning, Xiaobo), Design of Monitoring System to Marine Diesel Engine Supply Units Based on Forcecontrol Monitoring Software, Mechatronics engineering, computing and information technology Book Series: Applied Mechanics and Materials Volume: 556- 562 Pages: 3277-+. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, NB (Zhao, Ningbo); Li, SY (Li, Shuying); Cao, YP (Cao, Yunpeng); Meng, H (Meng, Hui), Remote Intelligent Expert System for Operation State of Marine Gas Turbine Engine, 11th World congress on intelligent control and automation (WCICA), pp. 3210-3215, 2014.

- Li, Z.X. Yan, X.P., Sheng, C.: A novel remote condition monitoring and fault diagnosis system for marine diesel engines based on the compressive sensing technology, Journal of vibroengineering, Volume: 16, Issue: 2, pp. 879-890, 2014.

- Zhao, J.B. Yan, X.P., Sheng, C.X.: Networked Live Lab for Marine Machinery, Proceedings of 2014 Prognostics and system health management conference (PHM-2014 HUNAN) Book Series: Prognostics and System Health Management Conference Pages: 364-367 Published: 2014.

- Yuan, Y.P. Yan, X.P., Wang, K., Yuan, C.Q.: A new remote intelligent diagnosis system for marine diesel engines based on an improved multi-kernel algorithm, Proceedings of the institution of mechanical engineers, Journal of risk and reliability Volume: 229 Issue: 6 pp. [CrossRef]

- Xuedong, W. He, G., Li, J.B.: A Design Method Based on Inherent Testability of Remote Control and Monitoring System for Marine Main Engine, Proceedings of the 2015 international conference on advanced engineering materials and technology Book Series: AER-Advances in Engineering Research, Volume: 38, pp. 773- 777, 2015.

- Kang, Y.J., Noh, Y., Jang, M.S., Park, S., Kim, J.T.: Hierarchical level fault detection and diagnosis of ship engine systems, Expert systems with applications, Volume: 213, Article Number: 118814. [CrossRef]

- A simakopoulos, I, Avendano-Valencia, LD, Luetzen, M, Rytter, N.G.M.: Data-driven condition monitoring of two-stroke marine diesel engine piston rings with machine learning, Ships and offshore structures. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S; Kim, H; Jeon, H.: Development of a Simplified Performance Monitoring System for Small and Medium Sized Ships, JOURNAL OF MARINE SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING Volume: 11 Issue: 9 Article Number: 1734. Published: SEP 2023. [CrossRef]

- Matulić, N. Radica, G. & Nižetić, S. Engine model for onboard marine engine failure simulation. J Therm Anal Calorim 141, 119–130. [CrossRef]

- Draskovic, Z. Diagnostic model of the marine engine air system, Master thesis, FESB, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).