Submitted:

02 February 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

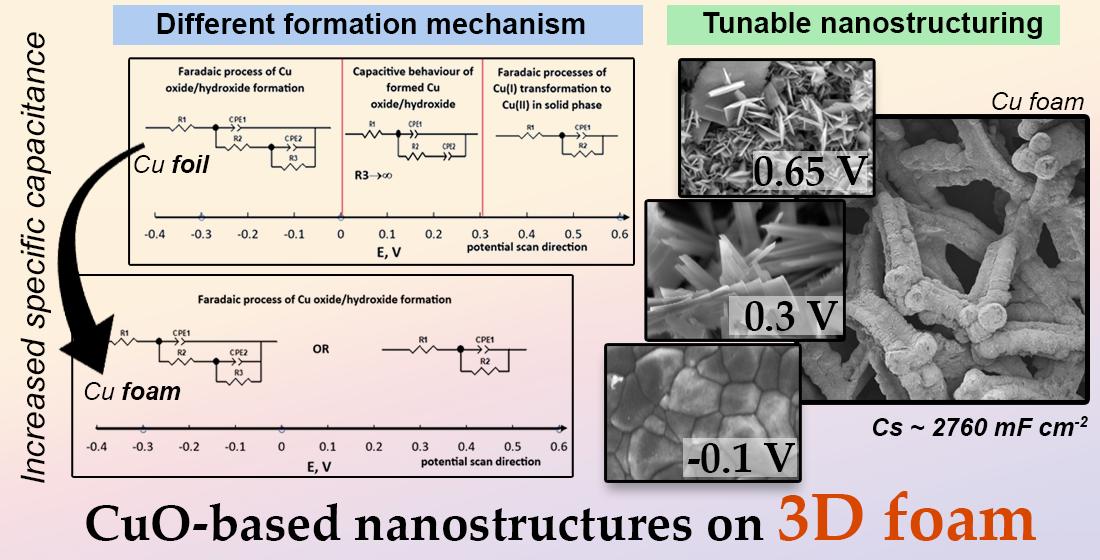

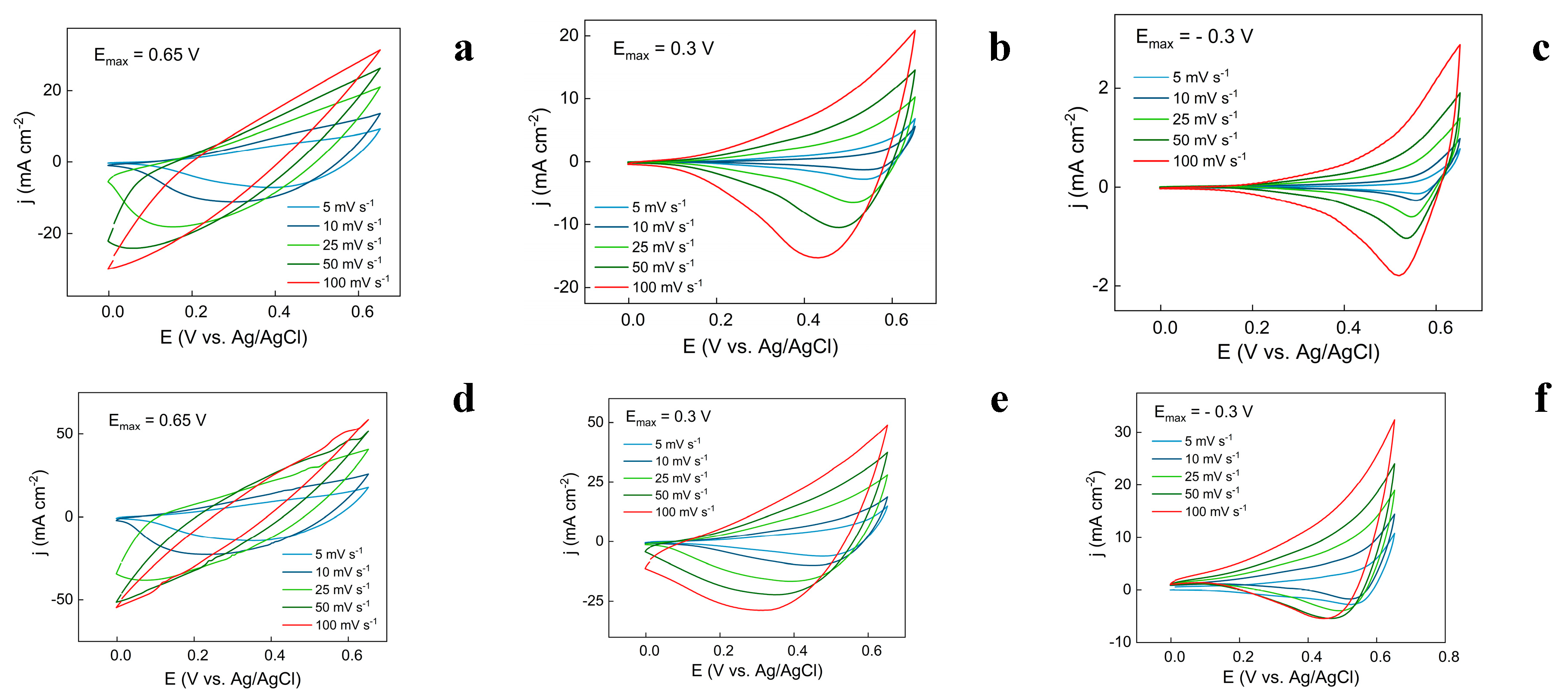

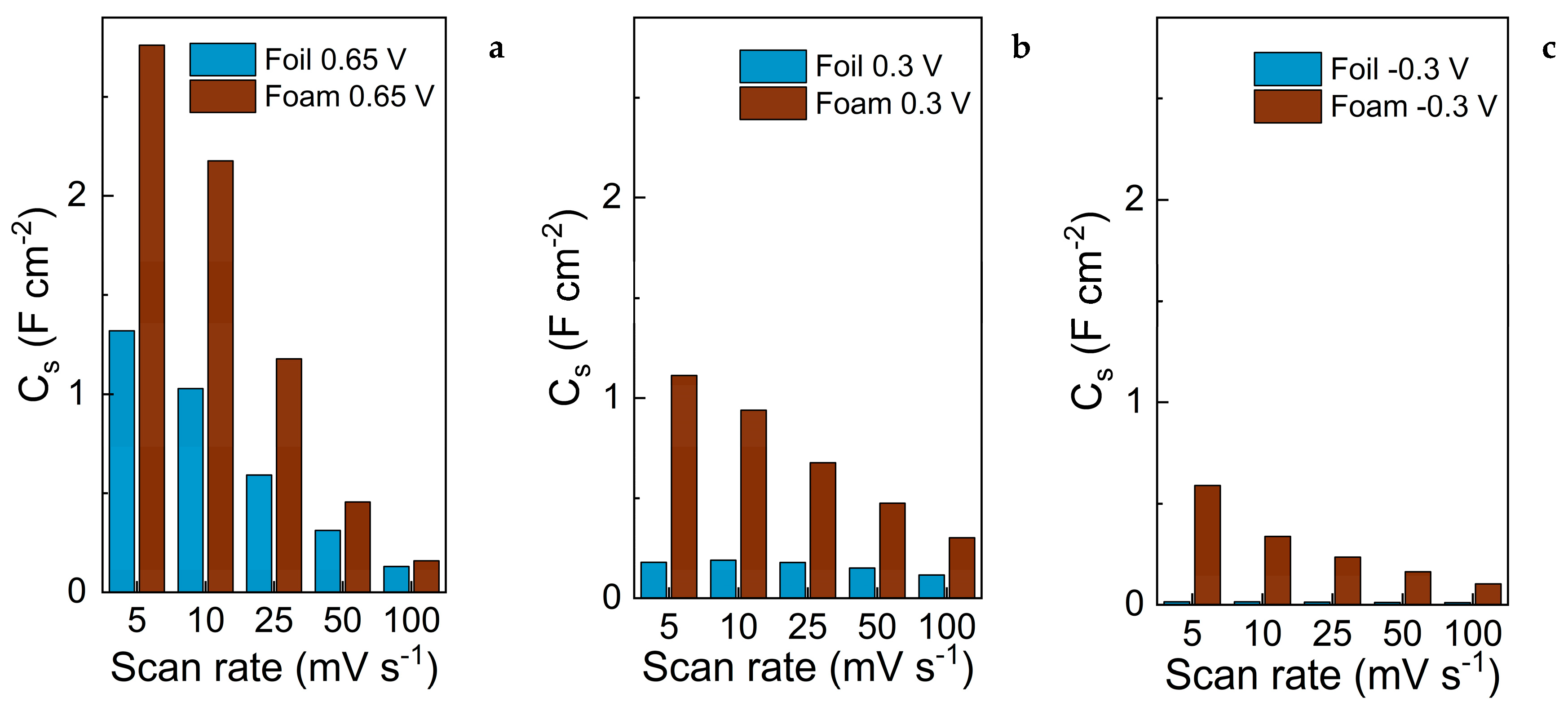

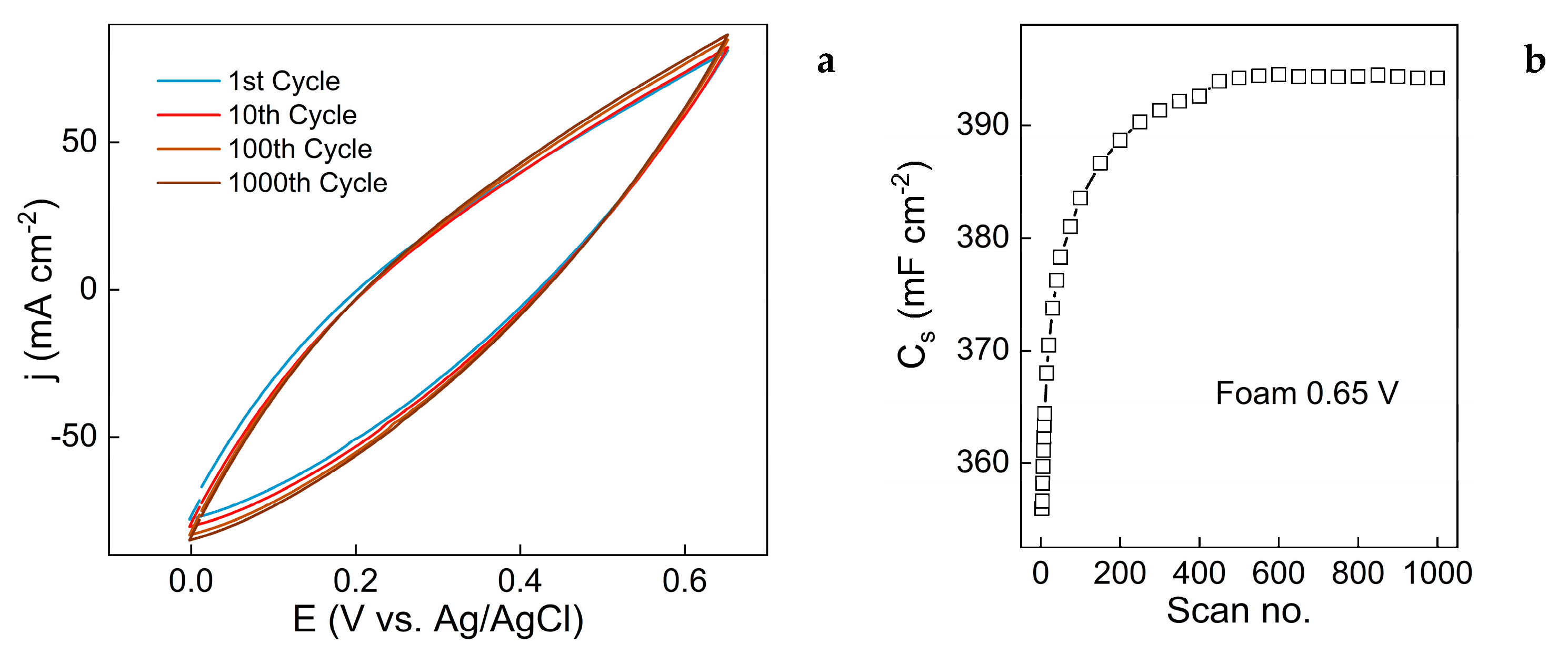

While renewable energy sources supply a progressively larger share of the world’s energetical needs, their non-continuous nature demands coupling with energy storage systems such as batteries or capacitors. Consequently, copper oxide-based materials have emerged as promising candidates due to their affordability, stability, and suitable electrochemical performance. In this study, nanostructured copper oxide-based films were electrochemically synthesized on copper foil and foam electrodes and investigated for their supercapacitive behaviour. The synthesis was carried out via cyclic voltammetry (CV) for up to 1000 cycles in an alkaline electrolyte. By tuning the upper vertex potential (-0.3 V to 0.65 V vs Ag/AgCl), both phase composition (Cu₂O, Cu(OH)₂, CuO) and morphology (grains, nanoneedles, nanoplatelets) were precisely controlled, demonstrating the versatility of this approach. EIS data using foil and foam electrodes shows that various processes occur on the electrode during changing potential from -1,0 to 0,6 V and back. The capacitive properties of the synthesized films were evaluated using CV in the potential range of 0 V–0.65 V, and the optimized CuO film synthesized on Cu foam exhibited a high specific capacitance of 2760 mF cm⁻². Charge-discharge cycling at 100 mV s⁻¹ for 1000 cycles indicated an initial capacitance increase followed by stable retention, highlighting the structural integrity and electrochemical stability of the films. These findings provide valuable insights into the controlled electrochemical synthesis of copper oxide nanostructures and their potential for high-performance capacitor applications.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis

2.2. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy

2.3. Structure and Morphology

2.4. Evaluation of Capacitive Properties

3. Results

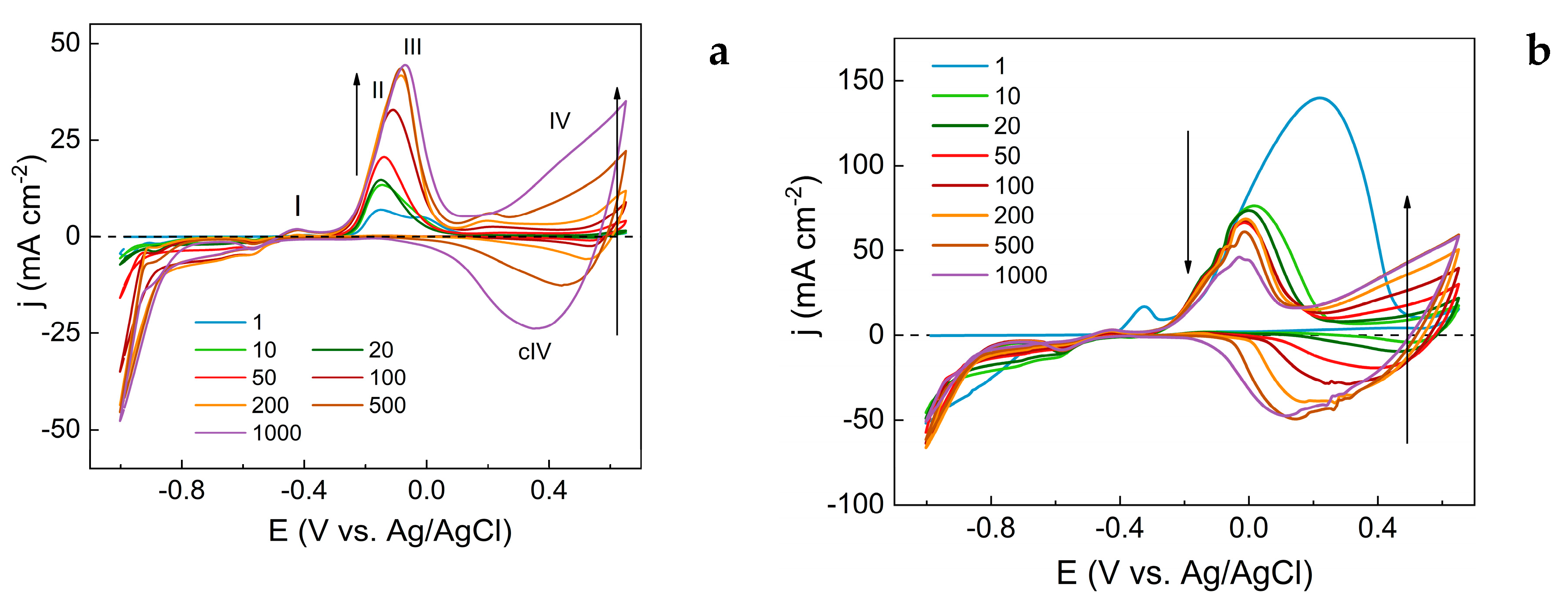

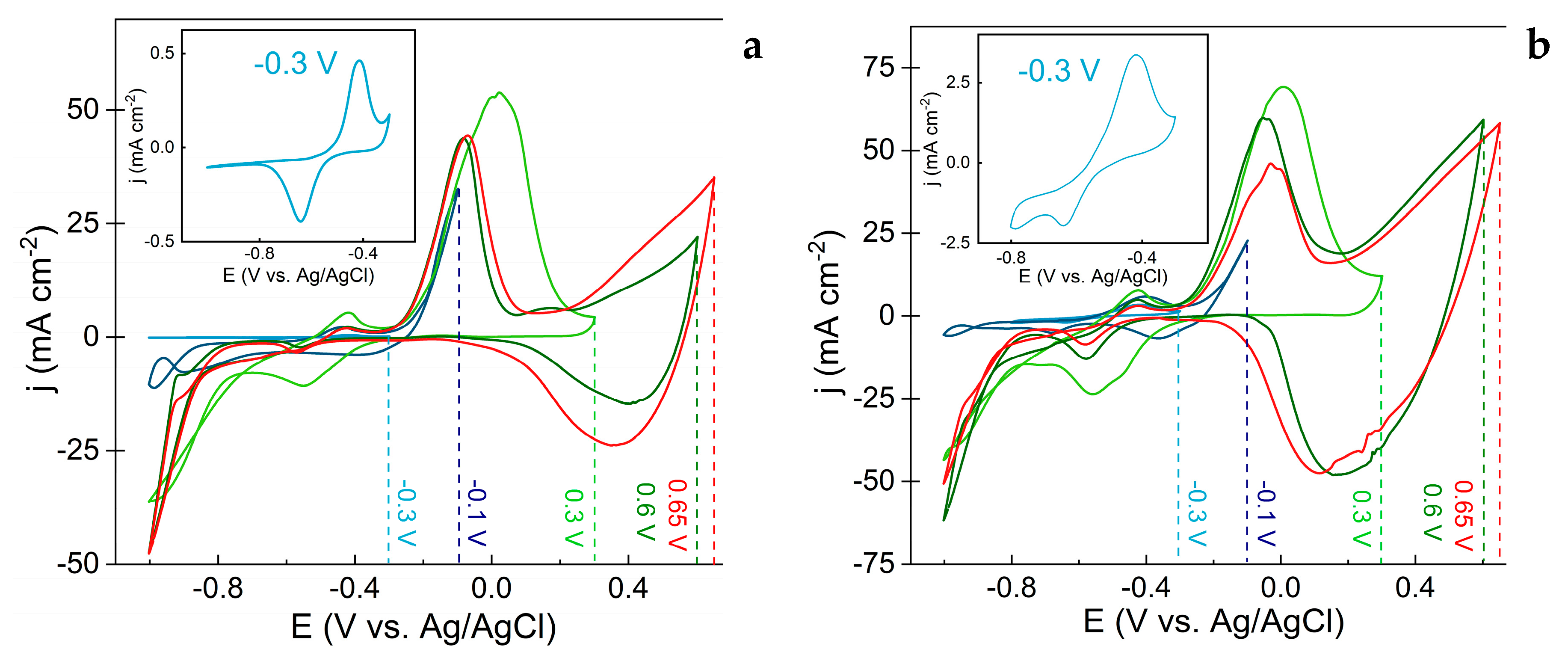

3.1. Evaluation of Electrochemical Synthesis of Copper Oxide-Based Nanostructures

- -

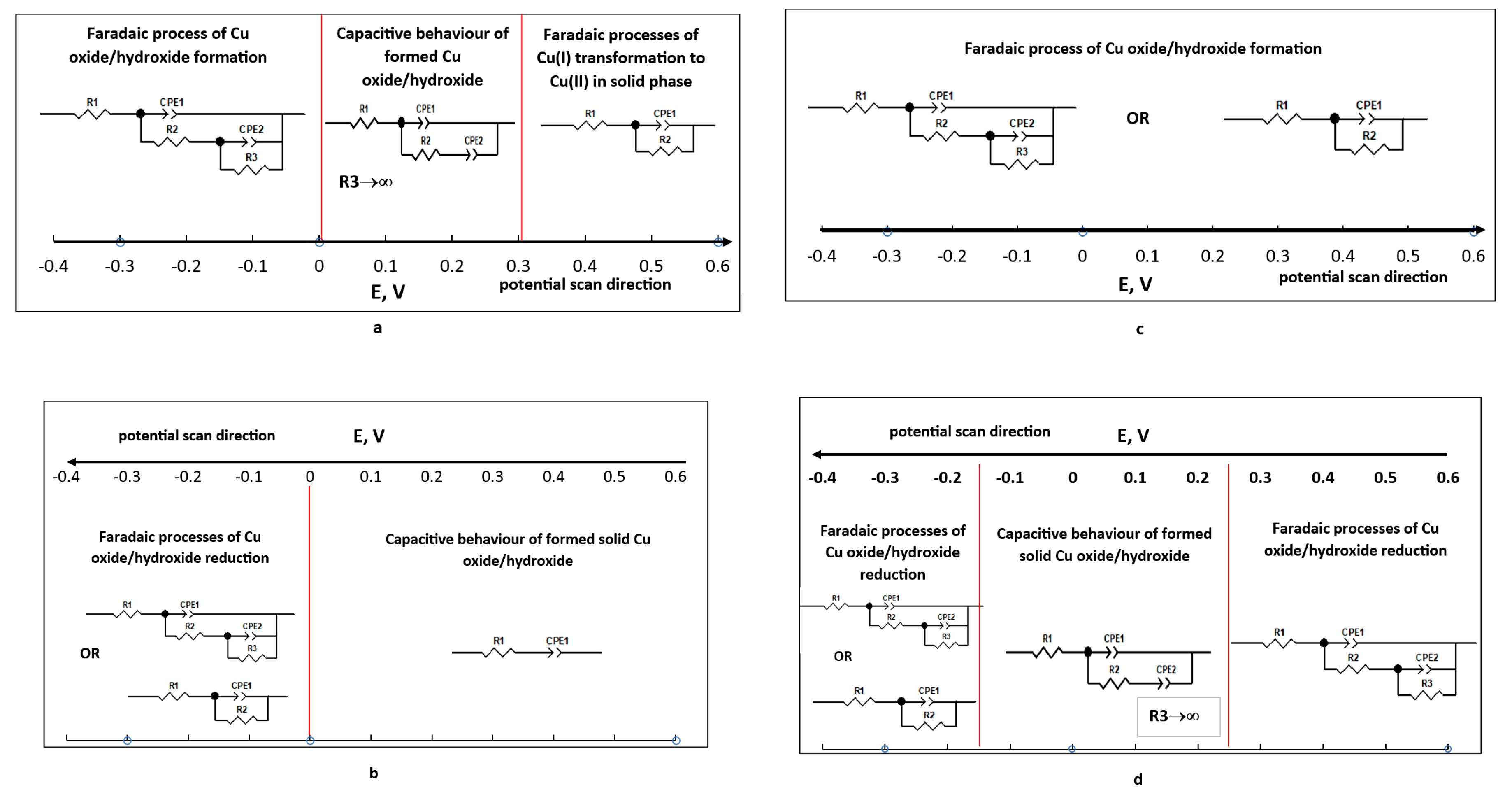

- Peak I, observed at -0.4 V, corresponds to the oxidation of metallic copper (equation 1).

- -

- Peak II, at -0.16 V, is associated with the formation of CuO from Cu₂O (equation 2).

- -

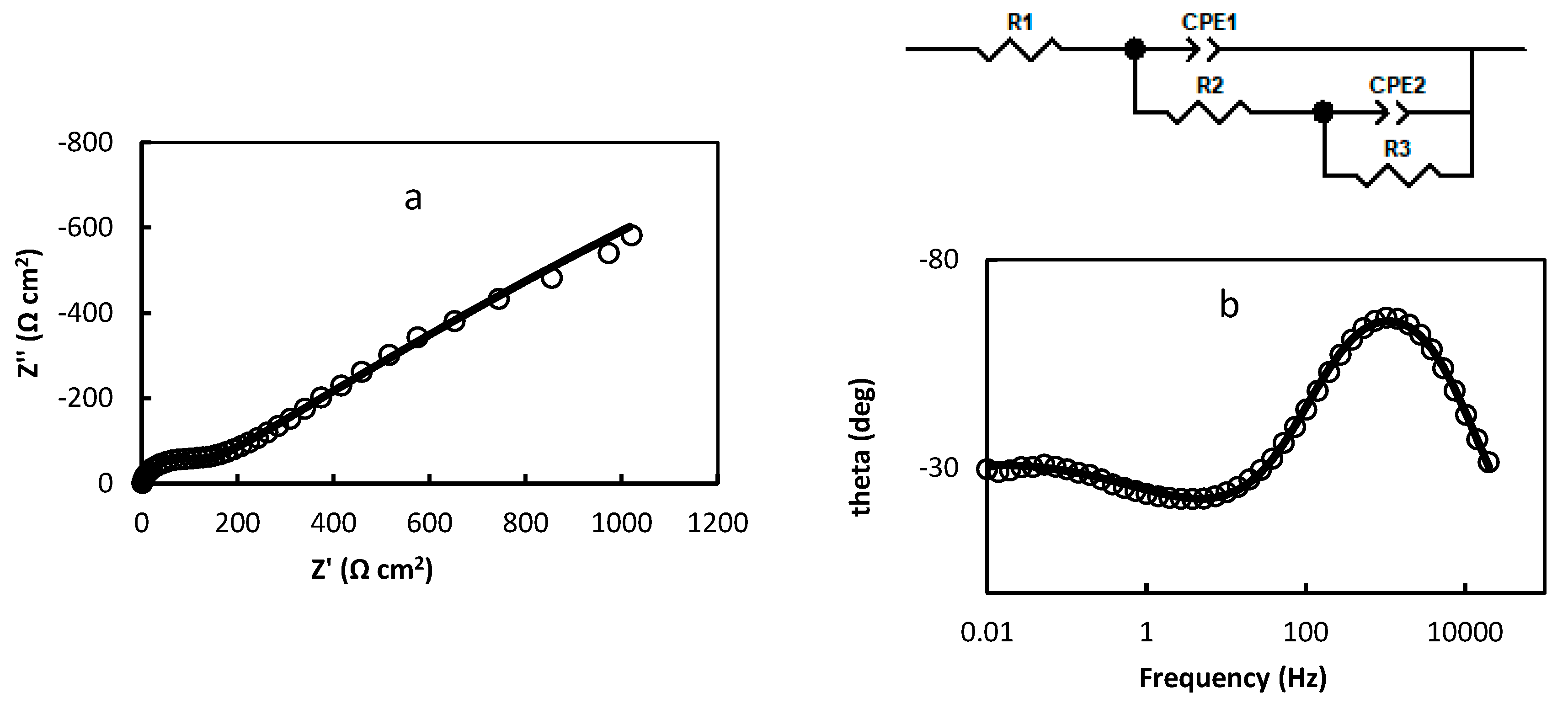

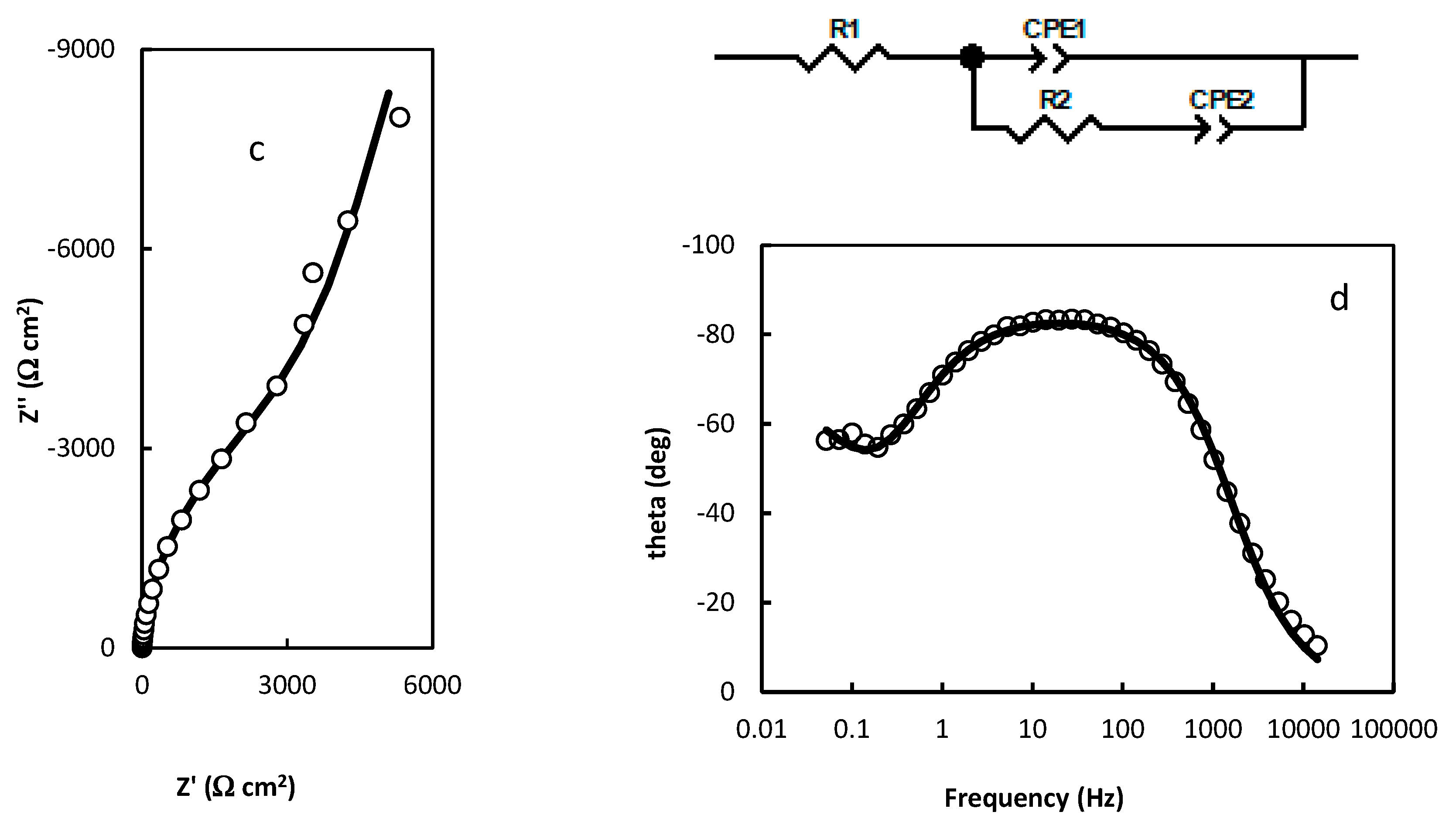

- R1=1.474 Ω cm2; R2=113.1 Ω cm2; R3=7930 Ω cm2; CPE1=3.737 10-5 (F cm-2)0.853; n1=0.853; CPE2=0.422 (F cm-2)0.422; n2=0.422 (Figure 3a,b);

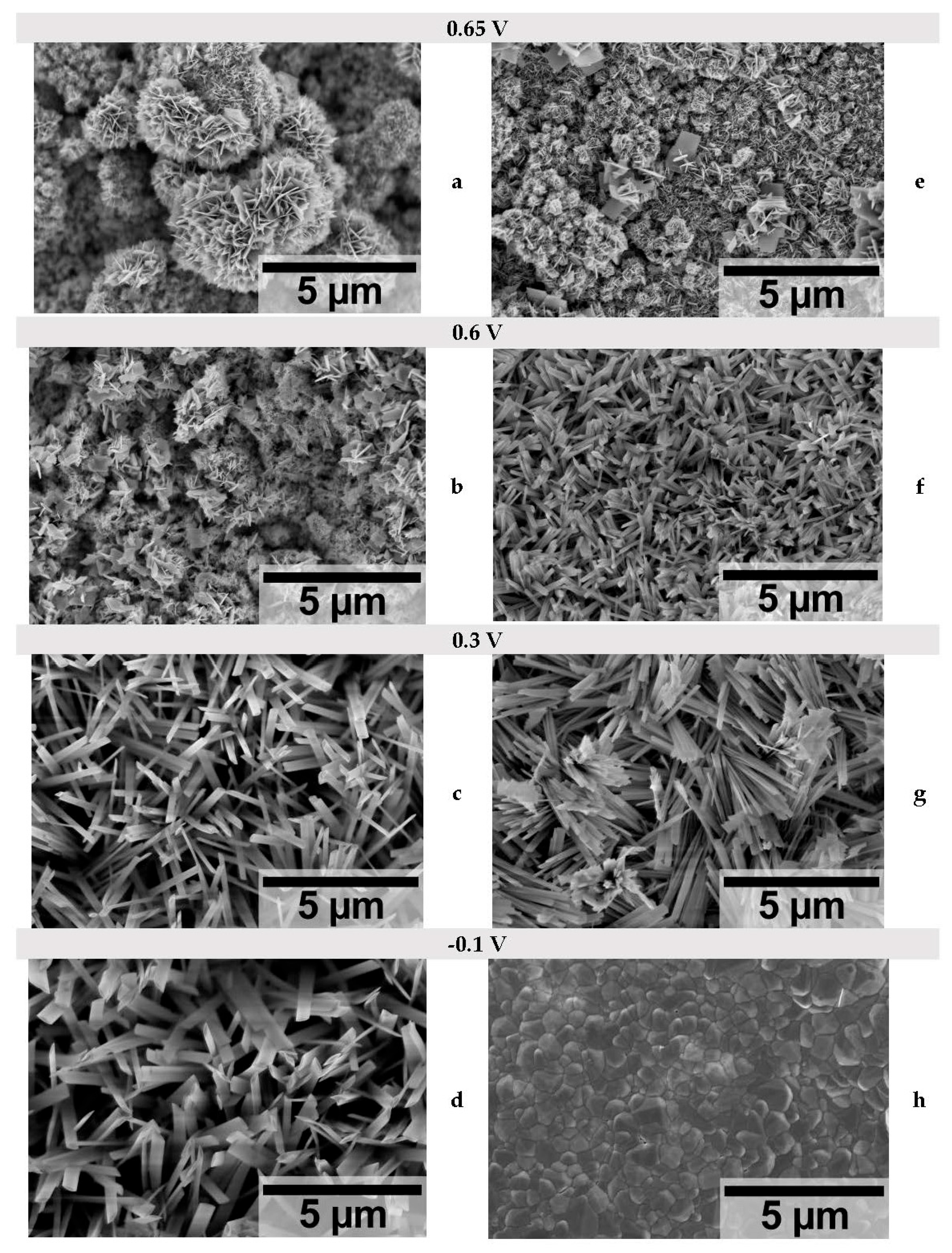

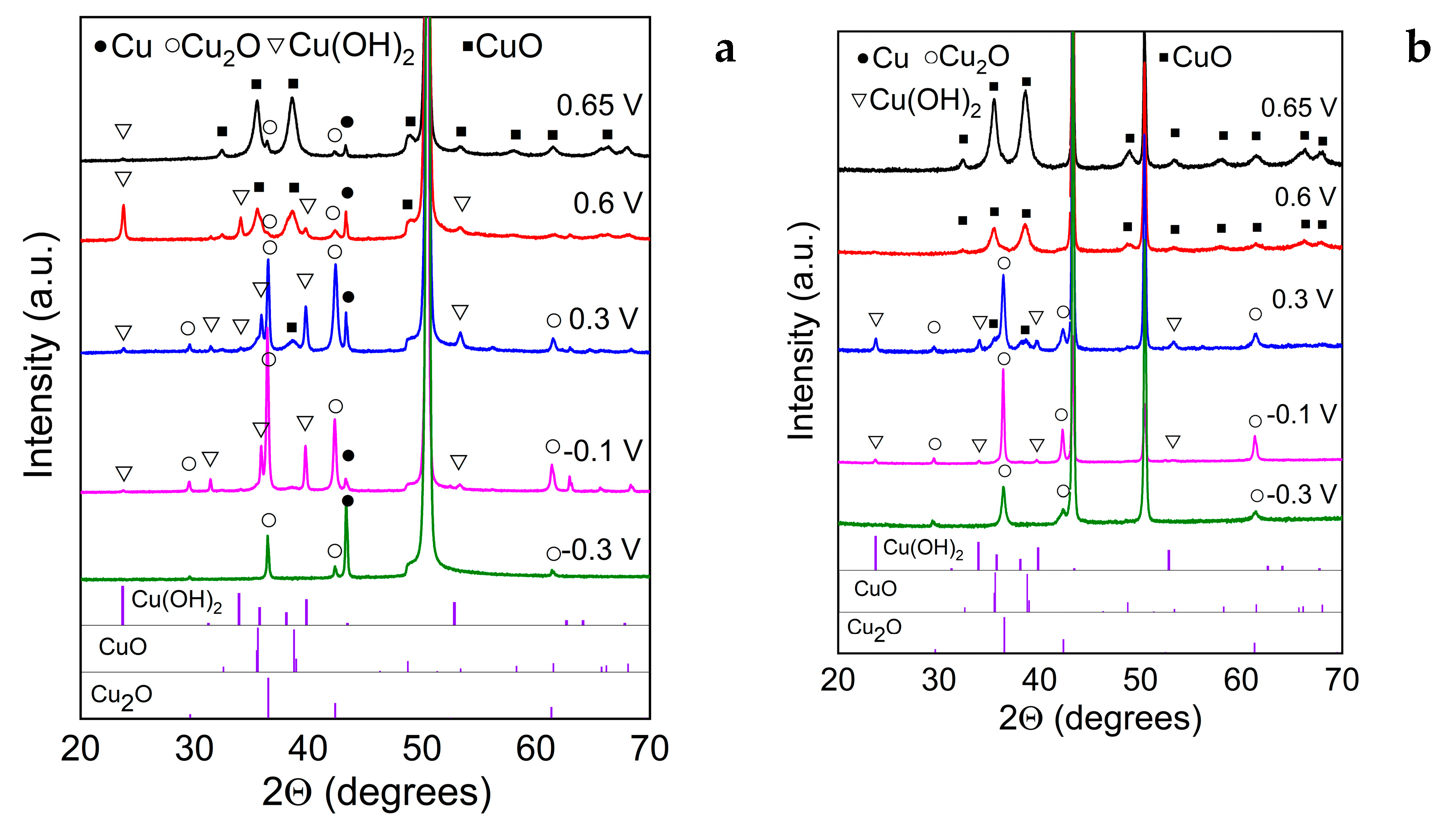

3.2. Evaluation of Morphology and Structure of the Obtained Films

3.3. Evaluation of Capacitive Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Delivering the European Green Deal. Https://Commission.Europa.Eu/Strategy-and-Policy/Priorities-2019-2024/European-Green-Deal/Delivering-European-Green-Deal_en 2025.

- Sisakyan, N.; Chilingaryan, G.; Manukyan, A.; Mukasyan, A.S. Combustion Synthesis of Materials for Application in Supercapacitors: A Review. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurav, K.V.; Patil, U.M.; Shin, S.W.; Agawane, G.L.; Suryawanshi, M.P.; Pawar, S.M.; Patil, P.S.; Lokhande, C.D.; Kim, J.H. Room Temperature Chemical Synthesis of Cu(OH)2 Thin Films for Supercapacitor Application. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2013, 573, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, D.; Ghosh, S. Recent Advancements of Copper Oxide Based Nanomaterials for Supercapacitor Applications. Journal of Energy Storage 2021, 34, 101995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patake, V.D.; Joshi, S.S.; Lokhande, C.D.; Joo, O.-S. Electrodeposited Porous and Amorphous Copper Oxide Film for Application in Supercapacitor. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2009, 114, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadale, S.B.; Patil, S.B.; Teli, A.M.; Masegi, H.; Noda, K. Effect of Deposition Potential and Annealing on Performance of Electrodeposited Copper Oxide Thin Films for Supercapacitor Application. Solid State Sciences 2022, 123, 106780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.S.; Pawar, S.M.; Ghatage, S.V.; Patil, A.P.; Redekar, R.S.; Yadav, H.M.; Tarwal, N.L.; Patil, P.S. Charge Storage Dynamics and Time Series Analysis of Binder Free Rapidly Synthesized Copper Oxide for Supercapacitors. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 2024, 184, 108769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Liu, J.; Liu, T.; Ye, K.; Cheng, K.; Yin, J.; Cao, D.; Wang, G.; Li, Q. Preparation of Binder-Free CuO/Cu2 O/Cu Composites: A Novel Electrode Material for Supercapacitor Applications. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 28270–28278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.K.; Shaikh, A.; Dusane, R.O.; Parida, S. Copper Oxide Nanosheets and Nanowires Grown by One-Step Linear Sweep Voltammetry for Supercapacitor Application. Journal of Energy Storage 2020, 31, 101631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubal, D.P.; Dhawale, D.S.; Salunkhe, R.R.; Jamdade, V.S.; Lokhande, C.D. Fabrication of Copper Oxide Multilayer Nanosheets for Supercapacitor Application. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2010, 492, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, A.; Shetty, A.N. Facile In-Situ Single Step Chemical Synthesis of Reduced Graphene Oxide-Copper Oxide-Polyaniline Nanocomposite and Its Electrochemical Performance for Supercapacitor Application. Electrochimica Acta 2017, 257, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, S.; Dhaygude, H.; Kim, D.-Y.; Ghodake, G.; Bhagwat, P.; Dandge, P.; Fulari, V. Improved Synthesis of Copper Oxide Nanosheets and Its Application in Development of Supercapacitor and Antimicrobial Agents. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2016, 36, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendashteh, A.; Mousavi, M.F.; Rahmanifar, M.S. Fabrication of Anchored Copper Oxide Nanoparticles on Graphene Oxide Nanosheets via an Electrostatic Coprecipitation and Its Application as Supercapacitor. Electrochimica Acta 2013, 88, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Jiang, H.; Hu, T.; Meng, C. Copper Oxide/Cuprous Oxide/Hierarchical Porous Biomass-Derived Carbon Hybrid Composites for High-Performance Supercapacitor Electrode. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2019, 782, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.M.; Kim, J.; Inamdar, A.I.; Woo, H.; Jo, Y.; Pawar, B.S.; Cho, S.; Kim, H.; Im, H. Multi-Functional Reactively-Sputtered Copper Oxide Electrodes for Supercapacitor and Electro-Catalyst in Direct Methanol Fuel Cell Applications. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 21310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumdar, D.; Baugh, N.; Bhattacharya, S.K. Ultrasound Assisted Formation of Reduced Graphene Oxide-Copper (II) Oxide Nanocomposite for Energy Storage Applications. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2017, 512, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morariu (Popescu), M.-I.; Nicolaescu, M.; Hulka, I.; Duţeanu, N.; Orha, C.; Lăzău, C.; Bandas, C. Fabrication of Cu2O/CuO Nanowires by One-Step Thermal Oxidation of Flexible Copper Mesh for Supercapacitor Applications. Batteries 2024, 10, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubal, D.P.; Gund, G.S.; Lokhande, C.D.; Holze, R. CuO Cauliflowers for Supercapacitor Application: Novel Potentiodynamic Deposition. Materials Research Bulletin 2013, 48, 923–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyed, S.G.; Shaikh, A.V.; Shinde, U.P.; Hiremath, P.; Naik, N. Copper Oxide-Based High-Performance Symmetric Flexible Supercapacitor: Potentiodynamic Deposition. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron 2023, 34, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Dai, S.; Liu, G.; Xi, Y.; Hu, C.; Wang, X. CuO Nanoflowers Growing on Carbon Fiber Fabric for Flexible High-Performance Supercapacitors. Electrochimica Acta 2016, 203, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Lv, H.; Sun, H.; Zhai, S.; An, Q. Construction of CuO/Cu-Nanoflowers Loaded on Chitosan-Derived Porous Carbon for High Energy Density Supercapacitors. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2023, 630, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, V.H.; Han, J.H.; Kang, H.W.; Lee, W. Highly Porous and Capacitive Copper Oxide Nanowire/Graphene Hybrid Carbon Nanostructure for High-Performance Supercapacitor Electrodes. Composites Part B: Engineering 2019, 178, 107464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Zheng, H.; Xu, G.; Zhao, J.; Cui, L.; Cui, J.; Qin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y. The Anodization Synthesis of Copper Oxide Nanosheet Arrays and Their Photoelectrochemical Properties. Applied Surface Science 2017, 412, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wu, Y. Corrosion Behavior of Copper at Elevated Temperature. International Journal of Electrochemical Science 2012, 7, 7902–7914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, W.Z.; Ambrosi, A.; Pumera, M. Direct Electrochemistry of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles in Alkaline Media. Electrochemistry Communications 2013, 28, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Briones, F.; Artés, J.M.; Díez-Pérez, I.; Gorostiza, P.; Sanz, F. Direct Observation of the Valence Band Edge by in Situ ECSTM-ECTS in p-Type Cu2 O Layers Prepared by Copper Anodization. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 1028–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidhyadharan, B.; Misnon, I.I.; Aziz, R.A.; Padmasree, K.P.; Yusoff, M.M.; Jose, R. Superior Supercapacitive Performance in Electrospun Copper Oxide Nanowire Electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 6578–6588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.M.; Kim, J.; Inamdar, A.I.; Woo, H.; Jo, Y.; Pawar, B.S.; Cho, S.; Kim, H.; Im, H. Multi-Functional Reactively-Sputtered Copper Oxide Electrodes for Supercapacitor and Electro-Catalyst in Direct Methanol Fuel Cell Applications. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 21310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesiulis, H.; Tsyntsaru, N.; Ramanavicius, A.; Ragoisha, G. The Study of Thin Films by Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. In Nanostructures and Thin Films for Multifunctional Applications; Tiginyanu, I., Topala, P., Ursaki, V., Eds.; NanoScience and Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; pp. 3–42. ISBN 978-3-319-30197-6. [Google Scholar]

- Oyarzún, D.P.; Tello, A.; Sánchez, J.; Boulett, A.; Linarez Pérez, O.E.; Martin-Trasanco, R.; Pizarro, G.D.C.; Flores, M.; Zúñiga, C. Exploration of Copper Oxide Nanoneedle Electrosynthesis Applied in the Degradation of Methylene Blue. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, M.; Kong, M.; Tao, S.; Zhang, C.; Wang, K. Synthesis and Growth Features of Copper Hydroxide Iodide Nanoneedles. Materials Letters 2007, 61, 846–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.K.; Murugesan, S.; Suresh, S. Anodization Assisted Preparation of Diverse Nanostructured Copper Oxide Films for Solar Selective Absorber. Optical Materials 2023, 135, 113304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajani, C.; Anuradha, V.; Sunandamma, Y. Copper Oxide/Hydroxide Nanomaterial Synthesized from Simple Copper Salt. Int. J. Nanosci. 2020, 19, 1950028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörner, L.; Cancellieri, C.; Rheingans, B.; Walter, M.; Kägi, R.; Schmutz, P.; Kovalenko, M.V.; Jeurgens, L.P.H. Cost-Effective Sol-Gel Synthesis of Porous CuO Nanoparticle Aggregates with Tunable Specific Surface Area. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 11758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, D.; Xing, S.; Sun, B.; Cai, H.; Suo, H.; Zhao, C. Design and Construction of Three-Dimensional Flower-like CuO Hierarchical Nanostructures on Copper Foam for High Performance Supercapacitor. Electrochimica Acta 2016, 210, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, C.; Jiang, H.; Li, C.; Zhang, L.; Lin, J.; Shen, Z.X. Advanced Energy Storage Devices: Basic Principles, Analytical Methods, and Rational Materials Design. Advanced Science 2018, 5, 1700322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, B.E. Transition from “Supercapacitor” to “Battery” Behavior in Electrochemical Energy Storage. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1991, 138, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyed, S.G.; Shaikh, A.V.; Shinde, U.P.; Hiremath, P.; Naik, N. Copper Oxide-Based High-Performance Symmetric Flexible Supercapacitor: Potentiodynamic Deposition. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron 2023, 34, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Wang, G.; Liu, G.; Suo, H.; Zhao, C. Construction of Leaf-like CuO–Cu2 O Nanocomposites on Copper Foam for High-Performance Supercapacitors. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 3318–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hu, J.; Jiang, L.; Li, X.; Cao, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, A.; Li, X.; Qu, L.; Lu, Y. High–Performance 3D CuO/Cu Flowers Supercapacitor Electrodes by Femtosecond Laser Enhanced Electrochemical Anodization. Electrochimica Acta 2019, 293, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Crystallite size, nm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foil | Foam | |||||

| Emax, V | Cu2O | Cu(OH)2 | CuO | Cu2O | Cu(OH)2 | CuO |

| 0.65 | - | - | 10.9 | - | - | 9.1 |

| 0.6 | - | 27.6 | 13.3 | - | - | 9.1 |

| 0.3 | 35.1 | 35.0 | 10.2 | 23.2 | 23.4 | 9.6 |

| -0.1 | 37.0 | 35.0 | - | 39.8 | 37.8 | - |

| -0.3 | 17.7 | - | - | 6.4 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).