Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Li4Ti5O12 Nanomaterial

2.3. Preparation of V-LTO@24 (Li4Ti5-xVxO12)

2.4. Material Characterizations

2.5. Li4Ti5O12 Electrode Preparation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Studies of Pristine Li4Ti5O12 Nanoflakes

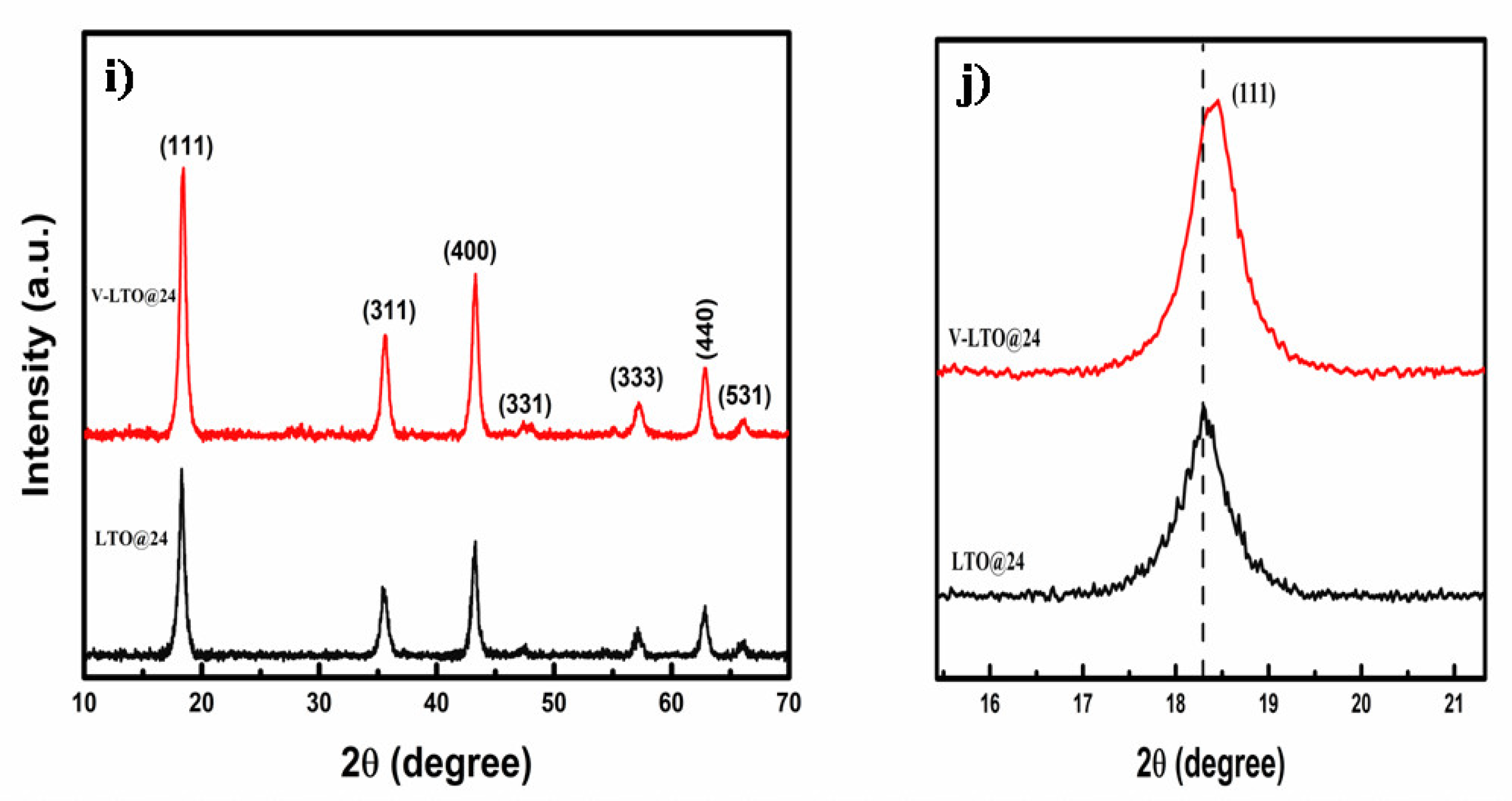

3.1.1. XRD Analysis

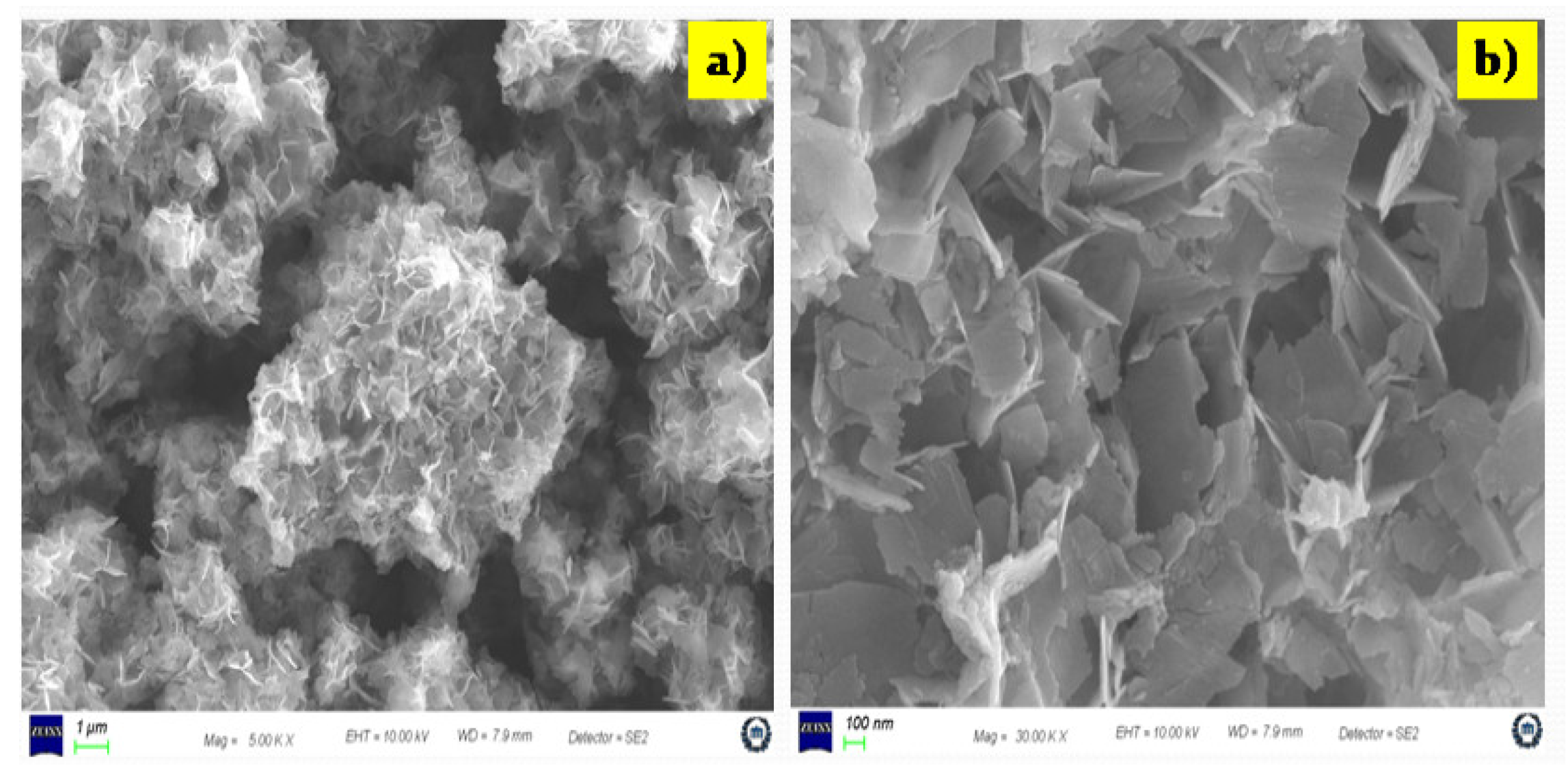

3.1.2. Surface Morphology Analysis

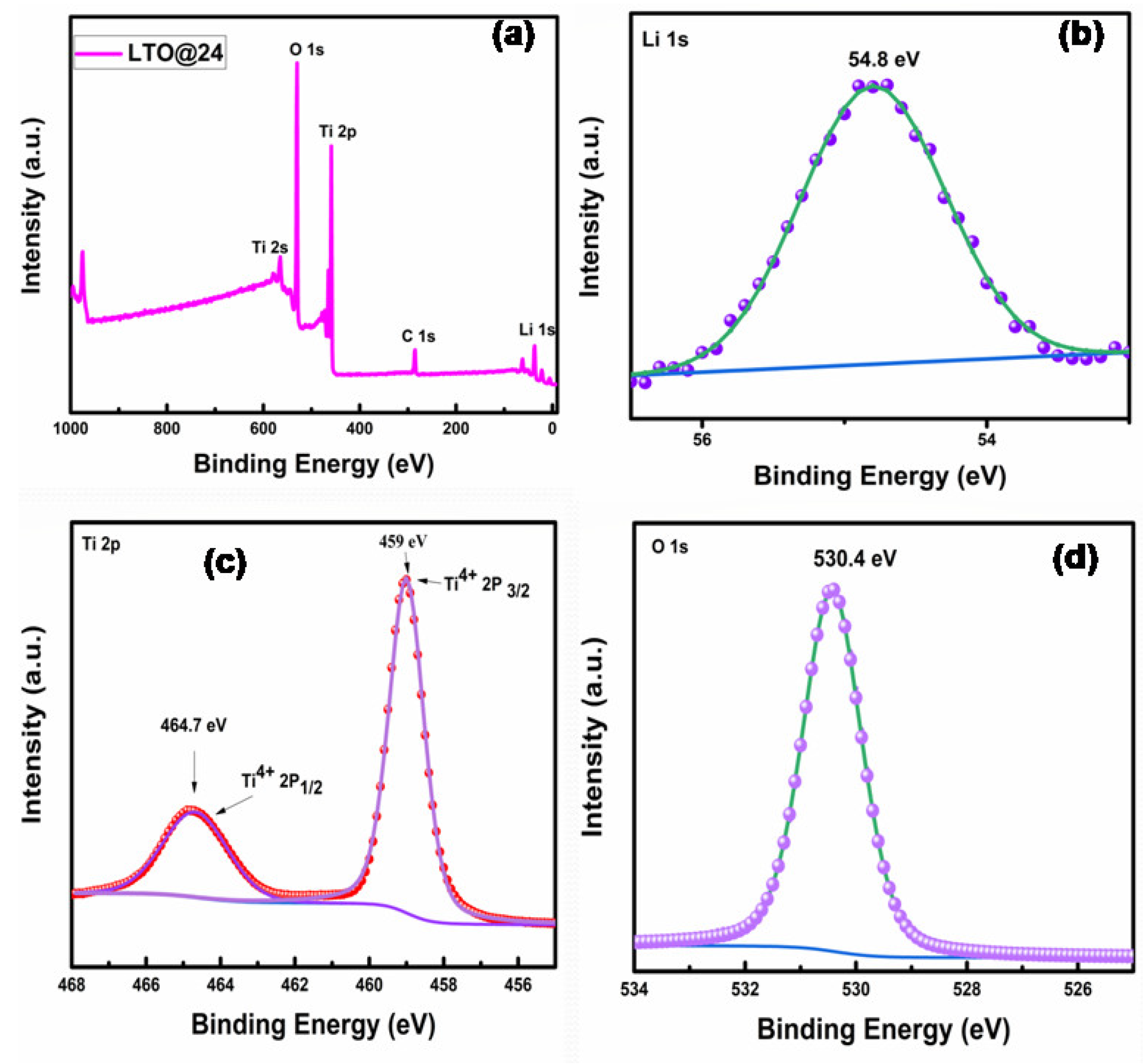

3.1.3. XPS Analysis

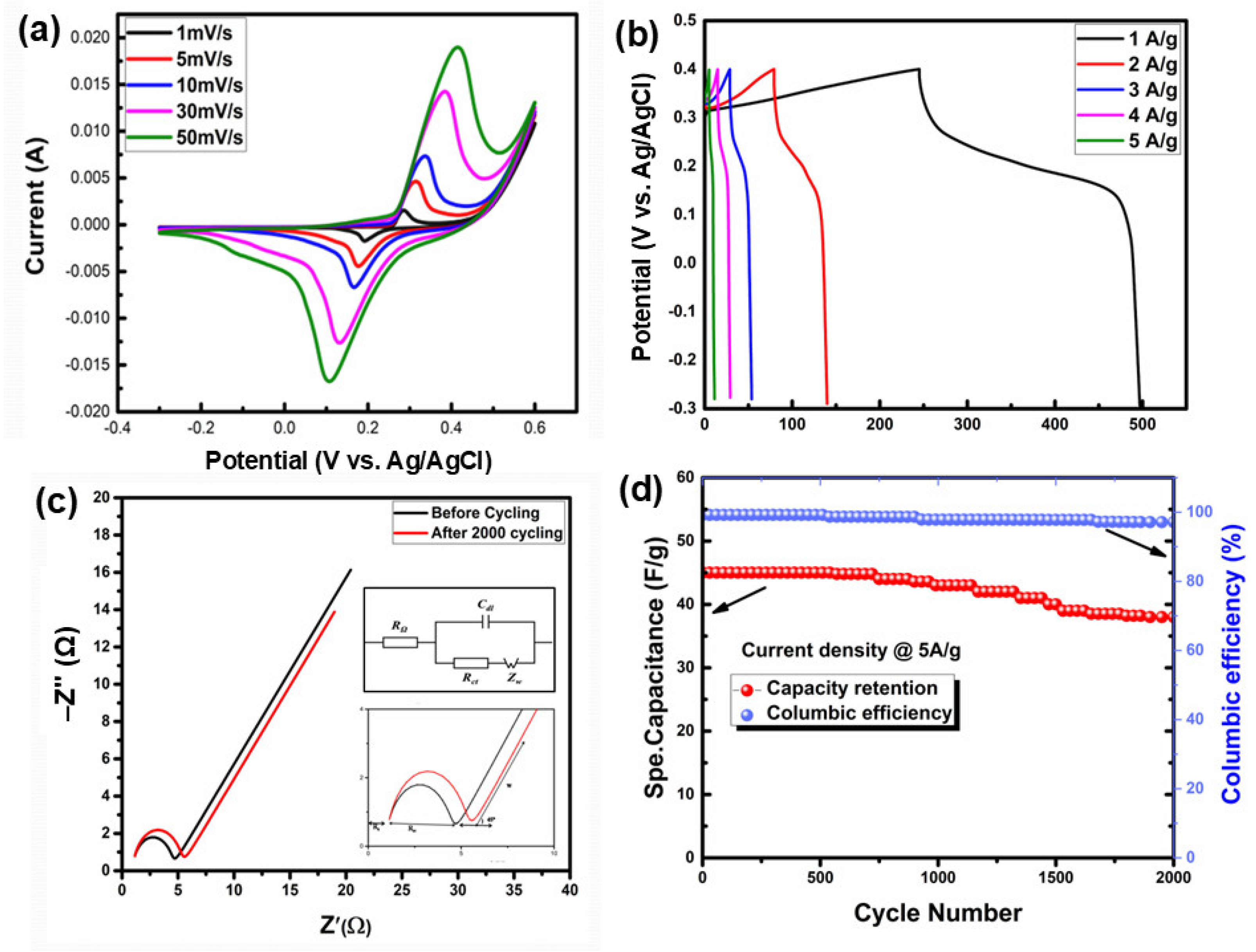

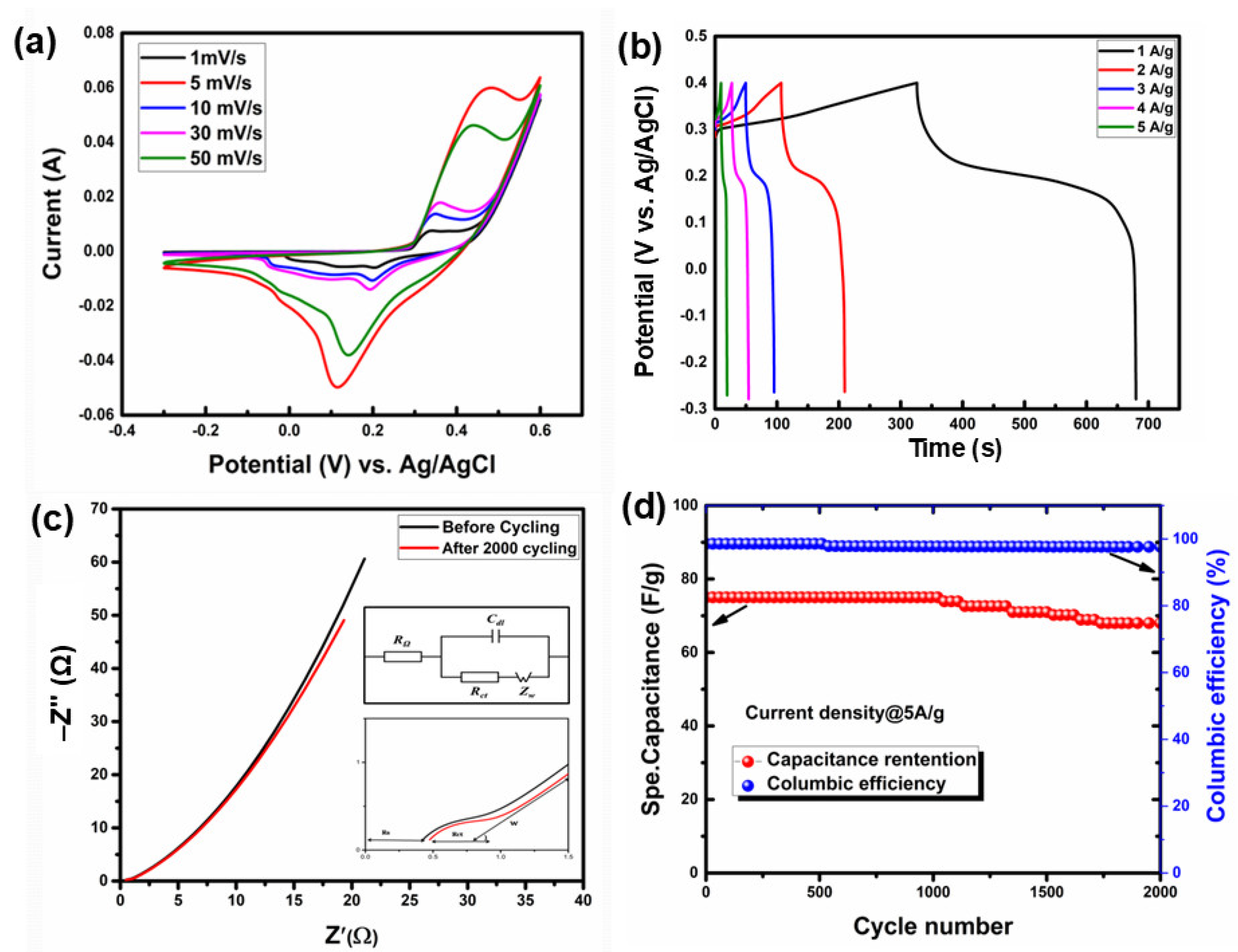

3.1.4. Electrochemical Analysis

3.2. Vanadium-Doped Li4Ti5O12 (V-LTO@24)

3.2.1. Structural Studies

3.2.2. Surface Morphology

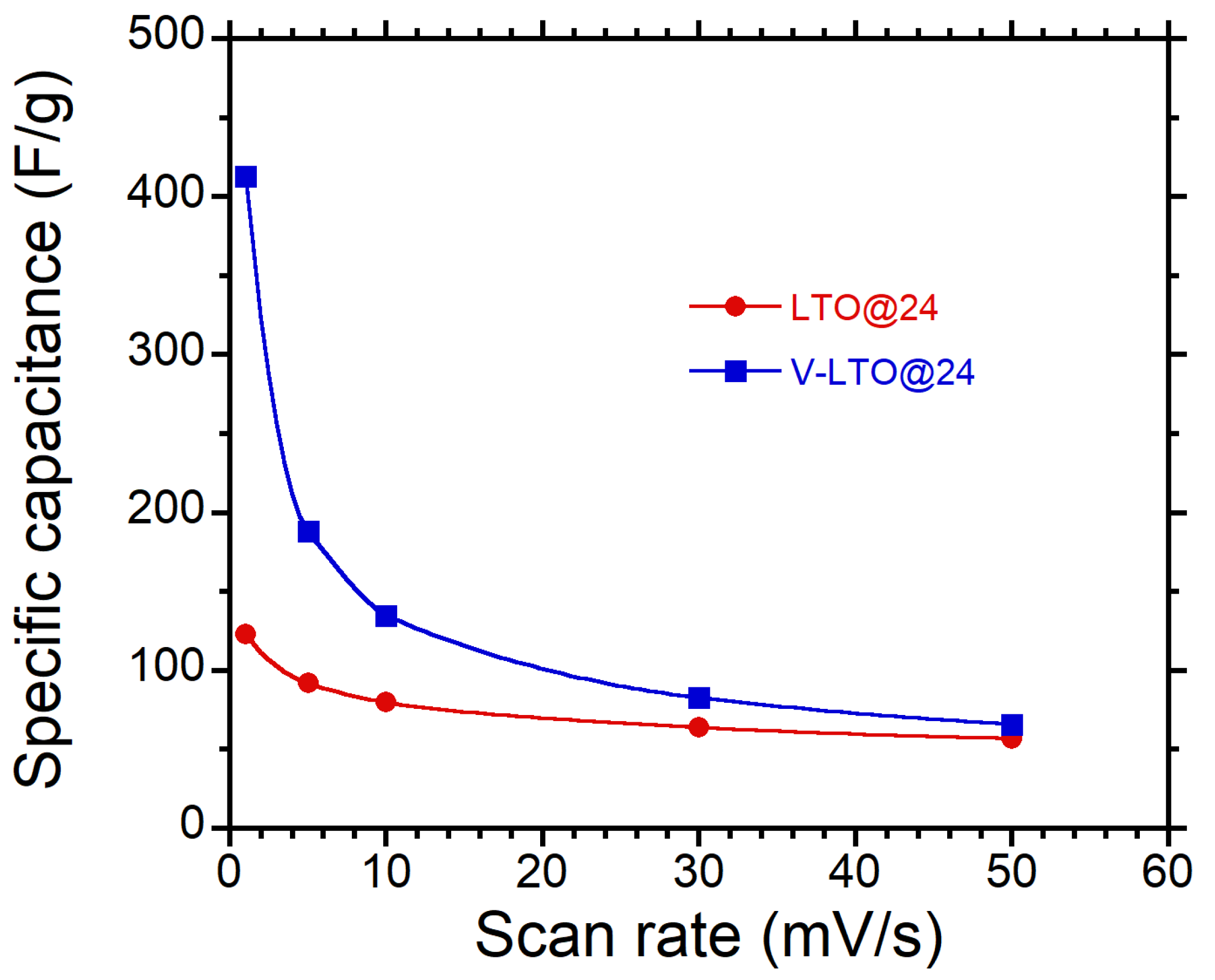

3.2.3. Electrochemical Analysis of V-LTO@24

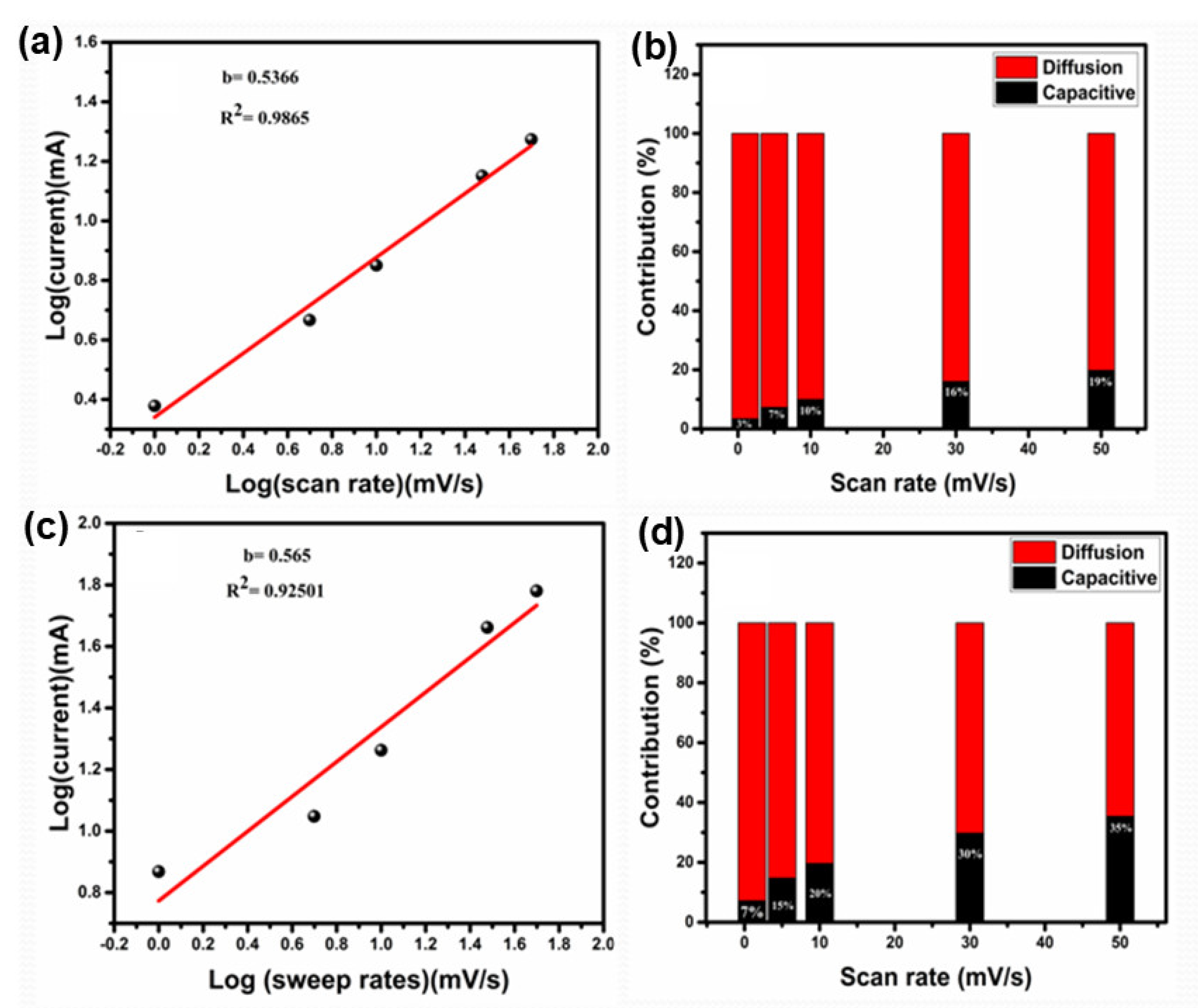

3.3. Charge Storage Mechanism in LTO-Based Electrodes

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peng, X.; Peng, L.; Wu, C.; Xie, Y. Two dimensional nanomaterials for flexible supercapacitors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 3303-3323. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Casalongue, H.S.; Liang, Y.; Dai, H. Ni(OH)2 nanoplates grown on graphene as advanced electrochemical pseudocapacitor materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 7472–7477. [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Katugampalage, T.R.; Khalid, M.; Ahmed, W.; Kaewsaneha, C.; Sreearunothai, P.; Opaprakasit, P. Microwave assisted synthesis of Mn3O4 nanograins intercalated into reduced graphene oxide layers as cathode material for alternative clean power generation energy device. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19043. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tao, Y.; Zheng, X.; Luo, J.; Kang, F.; Cheng, H.M.; Yang, Q.H. Ultra-thick graphene bulk supercapacitor electrodes for compact energy storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 3135–3142. [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Li, Z.; Deng, Y.; Yang, Q.H.; Kang, F. Graphene-based materials for electrochemical energy storage devices: opportunities and challenges. Energy Storage Mater. 2016, 2, 107–138. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Luo, B.; Li, H. A review on the conventional capacitors, supercapacitors, and emerging hybrid ion capacitors: past, present, and future. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2022, 3, 2100191. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dong, S.; Ding, B.; Wang, Y.; Hao, X.; Dou, H.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, X. Pseudocapacitive materials for electrochemical capacitors: from rational synthesis to capacitance optimization. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2017, 4, 71–90. [CrossRef]

- Pallavolu, M.R.; Nallapureddy, J.; Nallapureddy, R.R.; Neelima, G.; Yedluri, A.K.; Mandal, T.K.; Pejjai, B.; Joo, S.W. Self-assembled and highly faceted growth of Mo and V doped ZnO nanoflowers for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 886, 161234. [CrossRef]

- Mai, L.Q.; Yang, F.; Zhao, Y.L.; Xu, X.; Xu, L.; Luo, Y.Z. Hierarchical MnMoO4/CoMoO4 heterostructured nanowires with enhanced supercapacitor performance. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 381.

- Julien, C.M.; Mauger, A. Fabrication of Li4Ti5O12 (LTO) as anode material for Li-ion batteries. Micromachines (Basel) 2024, 15, 310.

- Yu, L.; Chen, G.Z. Supercapatteries as high-performance electrochemical energy storage devices. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2020, 3, 271–285. [CrossRef]

- Raut, B.; Ahmed, M.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Rahman Khan, M.M.; Bari, G.A.R.; Islam, M.; Nam, K.W. Battery-type transition metal oxides in hybrid supercapacitors: Synthesis and applications. Batteries 2025, 11, 60.

- Devadas, A.; Baranton, S.; Napporn, T.W.; Coutanceau, C. Tailoring of RuO2 nanoparticles by microwave assisted “Instant method” for energy storage applications. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 4044–4053.

- Julien, C.M.; Mauger, A. Nanostructured MnO2 as electrode materials for energy storage. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 396.

- Gunasekaran, S.S.; Gopalakrishnan, A.; Subashchandrabose, R.; Badhulika, S. Phytogenic generation of NiO nanoparticles as green-electrode material for high performance asymmetric supercapacitor applications. J. Energy Storage 2021, 37, 102412. [CrossRef]

- Haritha, B.; Deepak, M.; Hussain, O.M.; Julien, C.M. Morphological engineering of battery-type cobalt oxide electrodes for high-performance supercapacitors. Physchem, 2025, 5, 11. [CrossRef]

- Nunna, G.P.; Merum, D.; Ko, T.J.; Choi, J.; Hussain, O.M. High-performance MoO3 supercapacitor electrodes: Influence of reaction parameters on phase, microstructure, and electrochemical properties. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 5973–5987.

- Zhang, J.C.; Liu, Z.D.; Zeng, C.H.; Luo, J.W.; Deng, Y.D.; Cui, X.Y.; Chen, Y.N. High-voltage LiCoO2 cathodes for high-energy-density lithium-ion battery. Rare Met. 2022, 41, 3946–3956. [CrossRef]

- Abou-Rjeily, J.; Bezza, I.; Laziz, N.A.; Autret-Lambert, C.; Sougrati, M.T.; Ghamouss, F. High-rate cyclability and stability of LiMn2O4 cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries from low-cost natural β− MnO2. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 26, 423–432. [CrossRef]

- Borhani-Haghighi, S.; Kieschnick, M.; Motemani, Y.; Savan, A.; Rogalla, D.; Becker, H.W.; Meijer, J.; Ludwig, A. High-throughput compositional and structural evaluation of a Lia(NixMnyCoz)Or thin film battery materials library. ACS Combinatorial Sci. 2013, 15, 401–409.

- Lakshmi-Narayana, A.; Hussain, O.M.; Mauger, A.; Julien, C.M. Transport properties of nanostructured Li2TiO3 anode material synthesized by hydrothermal method. Sci (Basel), 1, 56.

- Ohzuku, T.; Ueda, A.; Yamamoto, N. Zero-strain insertion material of Li[Li1/3Ti5/3]O4 for rechargeable lithium cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1995, 142, 1431–1435. [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Xie, L.; Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Huang, B.; Sun, Z.; Cao, X.; Yang, T.; Wu, G. Advanced pseudocapacitive lithium titanate towards next-generation energy storage devices. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 103, 773–792. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Ji, X.; Weng, S.; Li, R.; Huang, X.; Zhu, C.; Xiao, X.; Deng, T.; Fan, L.; Chen, L.; Wang, X. 50C fast-charge Li-ion batteries using a graphite anode. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2206020.

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Su, J.; Liu, N.; Gao, Y. Revealing the phase-transition dynamics and mechanism in a spinel Li4Ti5O12 anode material through in situ electron microscopy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 20874–20881.

- Xing, L.L.; Wu, X.; Huang, K.J. High-performance supercapacitor based on three-dimensional flower-shaped Li4Ti5O12-graphene hybrid and pine needles derived honeycomb carbon. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 529, 171–179.

- Lee, B.; Yoon, J.R. Preparation and characteristics of Li4Ti5O12 with various dopants as anode electrode for hybrid supercapacitor. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2013, 13, 1350-1353. [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Sil, A. Role of calcination atmosphere in vanadium doped Li4Ti5O12 for lithium ion battery anode material. Mater. Res. Bull. 2017, 96, 449–457. [CrossRef]

- Khairy, M.; Bayoumy, W.A.; Qasim, K.F.; El-Shereafy, E.; Mousa, M.A. Ternary V-doped Li4Ti5O12-polyaniline-graphene nanostructure with enhanced electrochemical capacitance performance. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2021, 271, 115312.

- Batsukh, I.; Lkhagvajav, S.; Adiya, M.; Galsan, S.; Bat-Erdene, M.; Myagmarsereejid, P. Investigation of structural, optical, and electrochemical properties of niobium-doped Li4Ti5O12 for high-performance aqueous capacitor electrode. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 26313–26321. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Chen, P.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, L. Achievement of significantly improved lithium storage for novel clew-like Li4Ti5O12 anode assembled by ultrafine nanowires. J. Power Sources 2017, 350, 49–55. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.M. Improved performances of hybrid supercapacitors using granule Li4Ti5O12/activated carbon composite anode. Mater. Lett. 2018, 228, 220–223.

- Putjuso, T.; Putjuso, S.; Karaphun, A.; Swatsitang, E. Influence of Li concentration on structural, morphological and electrochemical properties of anatase-TiO2 nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11200. [CrossRef]

- Khanna, S.; Marathey, P.; Paneliya, S.; Chaudhari, R.; Vora, J. Fabrication of rutile–TiO2 nanowire on shape memory alloy: A potential material for energy storage application. Mater. Today: Proc. 2022, 50, 11–16.

- Chandra Sekhar, J.; Merum, D.; Hussain, O.M. Microstructural and supercapacitive performance of cubic spinel Li4Ti5O12 nanocomposite. Eur. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 5, 222–233.

- Xing, L.L.; Huang, K.J.; Cao, S.X.; Pang, H. Chestnut shell-like Li4Ti5O12 hollow spheres for high-performance aqueous asymmetric supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 332, 253–259. [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y.; Zhao, B.; Ran, R.; Cai, R.; Shao, Z. Synthesis of well-crystallized Li4Ti5O12 nanoplates for lithium-ion batteries with outstanding rate capability and cycling stability. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 13233–13243. [CrossRef]

- Kalawa, O.; Sichumsaeng, T.; Kidkhunthod, P.; Chanlek, N.; Maensiri, S. Ni-doped MnCo2O4 nanoparticles as electrode material for supercapacitors. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 4869–4886. [CrossRef]

- Aldon, L.; Kubiak, P.; Womes, M.; Jumas, J.C.; Olivier-Fourcade, J.; Tirado, J.L.; Corredor, J.I.; Pérez Vicente, C. Chemical and electrochemical Li-insertion into the Li4Ti5O12 spinel. Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 5721–5725.

- Yan, G.; Fang, H.; Zhao, H.; Li, G.; Yang, Y.; Li, L. Ball milling-assisted sol–gel route to Li4Ti5O12 and its electrochemical properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 470, 544–547.

- Zaghib, K.; Simoneau, M.; Armand, M.; Gauthier, M., Electrochemical study of Li4Ti5O12 as negative electrode for Li-ion polymer rechargeable batteries. J. Power Sources 1999, 81, 300–305. [CrossRef]

- Shinde, S.K.; Jalak, M.B.; Ghodake, G.S.; Maile, N.C.; Kumbhar, V.S.; Lee, D.S.; Fulari, V.J.; Kim, D.Y. Chemically synthesized nanoflakes-like NiCo2S4 electrodes for high-performance supercapacitor application. Appl. Surface Sci. 2019, 466, 822–829.

- Xia, H.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, J. Recent progress on two-dimensional nanoflake ensembles for energy storage applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 2018, 10, 66. [CrossRef]

- Le, P.A.; Le, V.Q.; Tran, T.L.; Nguyen, N.T.; Phung, T.V.B.; Dinh, V.A. Two-dimensional NH4V3O8 nanoflakes as efficient energy conversion and storage materials for the hydrogen evolution reaction and supercapacitors. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 25433–25442.

- Pawar, S.M.; Kim, J.; Inamdar, A.I.; Woo, H.; Jo, Y.; Pawar, B.S.; Cho, S.; Kim, H.; Im, H. Multi-functional reactively-sputtered copper oxide electrodes for supercapacitor and electro-catalyst in direct methanol fuel cell applications. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21310. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Song, D.; Pu, T.; Li, J.; Huang, B.; Wang, W.; Zhao, C.; Xie, L.; Chen, L. Two-dimensional porous ZnCo2O4 thin sheets assembled by 3D nanoflake array with enhanced performance for aqueous asymmetric supercapacitor. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 336, 679–689.

- Naresh, B.; Kuchi, C.; Rajasekhar, D.; Reddy, P.S. Solvothermal synthesis of MnCo2O4 microspheres for high-performance electrochemical supercapacitors. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 2022, 640, 128443. [CrossRef]

- Saraf, M.; Natarajan, K.; Mobin, S.M. Emerging robust heterostructure of MoS2–rGO for high-performance supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 16588–16595.

- Sheokand, S.; Kumar, P.; Jabeen, S.; Samra, K.S. 3D highly porous microspherical morphology of NiO nanoparticles for supercapacitor application. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2023, 27, 727–738.

- Shaik, D.P.; Kumar, M.S.; Reddy, P.N.K.; Hussain, O.M. High electrochemical performance of spinel Mn3O4 over Co3O4 nanocrystals. J. Molecular Struct. 2021, 1241, 130619.

- Pawar, S.M.; Inamdar, A.I.; Gurav, K.V.; Jo, Y.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.H.; Im, H. Effect of oxidant on the structural, morphological and supercapacitive properties of nickel hydroxide nanoflakes electrode films. Mater. Lett. 2015, 141, 336–339. [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Lv, H.; Sun, H.; Zhai, S.; An, Q. Construction of CuO/Cu-nanoflowers loaded on chitosan-derived porous carbon for high energy density supercapacitors. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 630, 525–534. [CrossRef]

- Merum, D.; Nallapureddy, R.R.; Pallavolu, M.R.; Mandal, T.K.; Gutturu, R.R.; Parvin, N.; Banerjee, A.N.; Joo, S.W. Pseudocapacitive performance of freestanding Ni3V2O8 nanosheets for high energy and power density asymmetric supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 5561–5578.

- Pallavolu, M.R.; Banerjee, A.N.; Joo, S.W. Battery-type behavior of Al-doped CuO nanoflakes to fabricate a high-performance hybrid supercapacitor device for superior energy storage applications. Coatings 2023, 13, 1337.

- Ajay, A.; Paravannoor, A.; Joseph, J., Anopp, A.V.; Nair, S.V.; Balakrishnan, A. 2 D amorphous frameworks of NiMoO4 for supercapacitors: defining the role of surface and bulk controlled diffusion processes. Appl. Surface Sci. 2015, 326, 39–47. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.N.; Inayat, A.; Ansir, R.; Naveed, A.; Abbas, S.M.; Haider, A.; Shah, S.M. Probing the synergy of Ni(OH)2/NiO nanoparticles supported on rGO for battery-type supercapacitors. Energy Technol. 2024, 12, 2300854.

- Gao, L.; Huang, D.; Shen, Y.; Wang, M. Rutile-TiO2 decorated Li4Ti5O12 nanosheet arrays with 3D interconnected architecture as anodes for high performance hybrid supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 23570–23576.

- Ni, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Gao, L. A high-performance hybrid supercapacitor with Li4Ti5O12-C nano-composite prepared by in situ and ex situ carbon modification. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2012, 16, 2791-2796. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Liu, J. Directly grown nanostructured electrodes for high volumetric energy density binder-free hybrid supercapacitors: A case study of CNTs//Li4Ti5O12. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 7780. [CrossRef]

- Gangaja, B.; Nair, S.V.; Santhanagopalan, D. Interface-engineered Li4Ti5O12–TiO2 dual-phase nanoparticles and CNT additive for supercapacitor-like high-power Li-ion battery applications. Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 095402.

| Sample | Crystallite size (nm) | Dislocation density(δ) | Microstrain (rd) | Lattice parameter (Å) |

Unit volume (Å3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTO@12 | 11 | 8.27652*1015 | 0.009933 | 8.4117(0) | 595.18 |

| LTO@18 | 12 | 6.98751*1015 | 0.008899 | 8.4018(2) | 593.08 |

| LTO@24 | 13 | 6.31196*1015 | 0.00827 | 8.3671(8) | 585.76 |

| V-LTO@24 | 11.8 | 7.7152*1015 | 0.0088 | 8.3401(2) | 580.11 |

| Sample | Capacitance | Retention over cycling | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| V-doped LTO Granule-LTO powders SSR synthesized nano-LTO R-TiO2 decorated LTO 3D chestnut shell-like LTO C-modified LTO LTO nanowire LTO–TiO2 nanoparticles Hydrothermal LTO@24 Hydrothermal V-LTO@24 |

179 mAh/g @ 1C 63 F/g @ 0.5 A/g 265 F/g @ 0.5 A/g 143 mAh/g @30C 653 F/g @ 1 A/g 83 F/g @ 2C 125 F/g @ 0.55 mA/cm2 174 mAh/g @ 2 A/g 357 F/g @ 1 A/g 442 F/g @ 1 A/g |

95% (300) 92.8% (7000) @ 3 A/g 81% (5000) @ 0.5 A/g 92.3% (3000) 88.5 % (4000) 84% (9000) @0.98 A/g 95% (400) @ 0.4 mA/cm2 85% (3000) @ 2 A/g 98.5% (2000) @ 5 A/g 99.8% (2000) @ 5 A/g |

[29] [32] [35] [57] [36] [58] [59] [60] this work this work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).