Submitted:

02 February 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

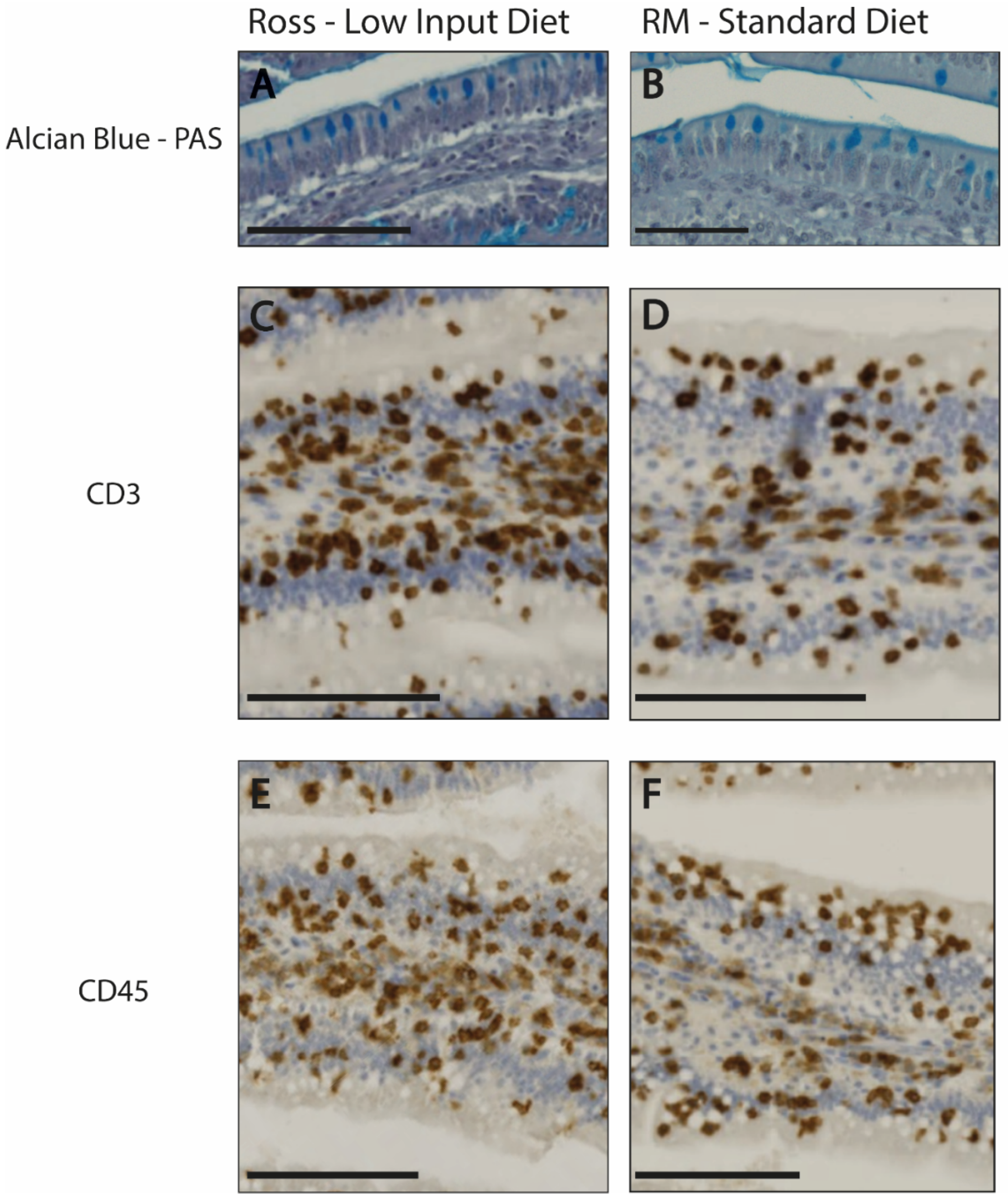

Reducing the environmental impact of poultry farming aligns with the European Green Deal’s goal of climate neutrality and sustainable food production. Local chicken breeds and low-input diets are promising strategies to achieve this. This study evaluated the effects of the diet (standard vs. low-input, formulated with reduced soybean meal in favour of local ingredients) on gut health in fast-growing chickens (Ross 308), local breeds (Bionda Piemontese. BP; Robusta Maculata, RM), and their crosses with Sasso (SA) hens (BP×SA, RM×SA). Histological samples from the jejunum were collected at slaughter (47 days for Ross 308, 105 days for others). Jejunal morphology was assessed focusing on villi height, crypt depth, goblet cell density, and immune markers (CD3+ and CD45+ cells). Local breeds, particularly RM, exhibited superior villus height-to-crypt depth ratios, related to better nutrient absorption compared to fast-growing genotypes. Ross chickens had higher goblet cell densities, reflecting greater sensitivity to environmental stress. The low-input diet reduced villi height and villus-to-crypt ratio but tended to increase CD3+ cell density. These effects may be ascribed to the replacement of soybean with fava beans and its antinutritional factors. These findings highlight the resilience of local breeds to dietary changes, supporting their suitability for alternative poultry production systems.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals, Facilities, and Experimental Design

2.2. Sampling of Jejunum Tissues and Histological and Immunohistochemistry Analyses

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Gut Morphology and Immuno-Histochemical Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The European Green Deal. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en" \t "_new (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Fetting, C. The European Green Deal. ESDN Report, December 2020; ESDN Office: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022: Ten Key Messages. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd_2022_wpp_key-messages.pdf (accessed on 02 November 2024).

- Boland, M.J.; Rae, A.N.; Vereijken, J.M.; Meuwissen, M.P.; Fischer, A.R.; Van Boekel, M.A.; Rutherfurd, S.M.; Gruppen, H.; Moughan, P.J.; Hendriks, W.H. The future supply of animal-derived protein for human consumption. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 29, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzo, G.; Legnardi, M.; Faustini, G.; Tucciarone, C.M.; Cecchinato, M. When Everything Becomes Bigger: Big Data for Big Poultry Production. Animals 2022, 13, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, D. The Role of Poultry in Human Nutrition. In Poultry Development Review; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2013; pp. 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tallentire, C.W.; Leinonen, I.; Kyriazakis, I. Artificial selection for improved energy efficiency is reaching its limits in broiler chickens. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 19231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himu, H.; Raihan, A. A review of the effects of intensive poultry production on the environment and human health. Int. J. Vet. Res. 2023, 3, 55–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.E.; Thomas, R.; Williams, M.; Zalasiewicz, J.; Edgeworth, M.; Miller, H.; Coles, B.; Foster, A.; Burton, E.J.; Marume, U. The broiler chicken as a signal of a human-reconfigured biosphere. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 180325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA AHAW Panel (EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare); Nielsen, S. S.; Alvarez, J.; Bicout, D.J.; et al. Welfare of broilers on farm. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e07788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartoni Mancinelli, A.; Mattioli, S.; Menchetti, L.; Dal Bosco, A.; Ciarelli, C.; Guarino Amato, M.; Castellini, C. The Assessment of a Multifactorial Score for the Adaptability Evaluation of Six Poultry Genotypes to the Organic System. Animals 2021, 11, 2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Bouvarel, I.; Ponchant, P.; Van Der Werf, H.M.G. Using Environmental Constraints to Formulate Low-Impact Poultry Feeds. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 28, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorilla, E.; Birolo, M.; Ala, U.; Xiccato, G.; Trocino, A.; Schiavone, A.; Mugnai, C. Productive performances of slow-growing chicken breeds and their crosses with a commercial strain in conventional and free-range farming systems. Animals 2023, 13, 2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Ariza, A.; Arando Arbulu, A.; Navas Gonzalez, F.J.; Nogales Baena, S.; Delgado Bermejo, J.V.; Camacho Vallejo, M.E. The Study of Growth and Performance in Local Chicken Breeds and Varieties: A Review of Methods and Scientific Transference. Animals 2021, 11, 2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartoni Mancinelli, A.; Menchetti, L.; Birolo, M.; Bittante, G.; Chiattelli, D.; Castellini, C. Crossbreeding to improve local chicken breeds: Predicting growth performance of the crosses using the Gompertz model and estimated heterosis. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perella, F.; Mugnai, C.; Dal Bosco, A.; Sirri, F.; Cestola, E.; Castellini, C. Faba bean (Vicia faba var. minor) as a protein source for organic chickens: performance and carcass characteristics. It. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 8, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menchetti, L.; Birolo, M.; Mugnai, C.; Cartoni Mancinelli, A.; Xiccato, G.; Trocino, A.; Castellini, C. Effect of genotype and nutritional and environmental challenges on growth curve dynamics of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Farnell, Y.Z.; Peebles, E.D.; Kiess, A.S.; Wamsley, K.G.S.; Zhai, W. Effects of prebiotics, probiotics, and their combination on growth performance, small intestine morphology, and resident Lactobacillus of male broilers. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95, 1332–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, D.J. Alterations in piglet small intestinal structure at weaning. Res. Vet. Sci. 1986, 40, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueden, C.T.; Schindelin, J.; Hiner, M.C.; De Zonia, B.E.; Walter, A.E.; Arena, E.T.; Eliceiri, K.W. ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next generation of scientific image data. BMC Bioinformatics 2017, 18, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhang, H.; Yu, S.; Wu, S.; Yoon, I.; Quigley, J.; Gao, Y.; Qi, G. Effects of Yeast Culture in Broiler Diets on Performance and Immunomodulatory Functions. Poult. Sci. 2008, 87, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, N.; Ganner, A.; Masching, S.; Schatzmayr, G.; Applegate, T.J. Efficacy of a yeast derivative on broiler performance, intestinal morphology and blood profile. Livest. Sci. 2012, 143, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.N.; Le, N.H.; Pham, V.V.; Eva, P.; Alberto, F.; Le, H.T. Relationship between the ratio of villous height:crypt depth and gut bacteria counts as well as production parameters in broiler chickens. J. Agric. Dev. 2021, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, A.; Trocino, A.; Birolo, M.; Pascual, A.; Bordignon, F.; Radaelli, G.; Bortoletti, M.; Xiccato, G. Growth performance and gut response of broiler chickens fed diets supplemented with grape (Vitis vinifera L.) seed extract. Ital J Anim Sci 2022, 21, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, A.; Pauletto, M. : Trocino, A.; Birolo, M.; Dacasto, M.; Giantin, M.; Bordignon, F.; Ballarin, C.; Bortoletti, M.; Pillan, G.; Xiccato, G. Effect of the dietary supplementation with extracts of chestnut wood and grape pomace on performance and jejunum response in female and male broiler chickens at different ages. J Animal Sci Biotechnol 2022, 13, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, M.; Rodriguez-Lecompte, J.; Rogiewicz, A.; Patterson, R.; Slominski, B. Effect of yeast-derived products and distillers dried grains with solubles (DDGS) on growth performance, gut morphology, and gene expression of pattern recognition receptors and cytokines in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.K.; Parsek, M.R.; Greenberg, E.P.; Welsh, M.J. A component of innate immunity prevents bacterial biofilm development. Nature 2002, 417, 552–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, J.K.; Kesimer, M.; Pickles, R. Innate immunity and mucus structure and function. In Innate Immunity to Pulmonary Infection: Novartis Foundation Symposium 279; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2006; pp. 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yason, C.V.; Summers, B.A.; Schat, K.A. Pathogenesis of rotavirus infection in various age groups of chickens and turkeys: Pathology. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1987, 6, 927–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chickens, no. | Villi length, μm | Crypts depth, μm | Villus/crypt ratio | Goblet cells, no. | CD3+, cells/10,000 μm2 | CD45+, cells/10,000 μm2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | 12 | 963A | 88.2A | 11.08AB | 19.2A | 2943 | 3121 |

| BP×SA | 12 | 1016A | 98.8A | 10.47AB | 19.4A | 3678 | 3302 |

| RM | 12 | 1316B | 90.5A | 14.75C | 17.7A | 3257 | 3023 |

| RM×SA | 12 | 1167AB | 106.4A | 11.19B | 17.9A | 3296 | 3192 |

| Ross | 12 | 1028A | 136.4B | 7.80A | 21.6B | 3176 | 3291 |

| Standard | 30 | 1147 | 102.6 | 11.7 | 18.9 | 3092 | 3198 |

| Low input | 30 | 1049 | 105.6 | 10.4 | 19.5 | 3447 | 3174 |

| P value (G) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.280 | 0.806 | |

| P value (D) | 0.046 | 0.529 | 0.039 | 0.172 | 0.095 | 0.888 | |

| P value (GxD) | 0.189 | 0.190 | 0.163 | 0.280 | 0.369 | 0.368 | |

| RMSE | 187 | 18.6 | 2.33 | 1.51 | 807 | 635 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).