Submitted:

02 February 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Metatranscriptomics has recently expanded the species richness and host range of the Avastrovirus genus, quadrupling the number of avian orders known to host them in less than a decade. Despite this growing awareness of astrovirus presence in wild birds, limited attention has been paid to these viruses in the context of disease in Australian avifauna. Here we used unbiased RNA sequencing of intestinal samples from a galah (Eolophus roseicapilla) and an Australian king parrot (Alisterus scapularis) with a chronic diarrhoeal and wasting disease to detect the entire genomes of two novel astrovirus species, Avastrovirus eolorosei (PQ893528) and Avastrovirus aliscap (PQ893527). The phylogenetic positions of these viruses highlight the importance of current and future metatranscriptomic virus screening in investigations of avian host landscapes beyond Galloanserae. This is also the first documentation of avastrovirus infections in Psittaciformes and the first to report their potential role as disease agents in them.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Histories and Necropsy

2.2. Tissue Processing, RNA Extraction, and Library Preparation

2.3. Next Generation Sequencing and Metatranscriptomic Analysis

2.4. Novel Astrovirus Characterisation

2.5. Phylogenetic Analyses

2.6. Predictive Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Necropsy Findings

3.2. Metatranscriptomic Libraries

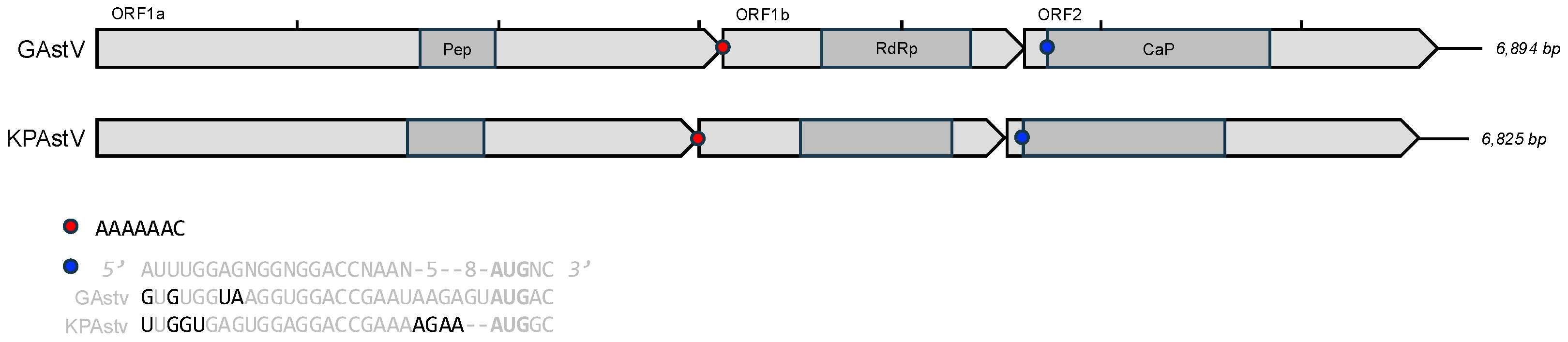

3.3. Genome Annotation and Alignments

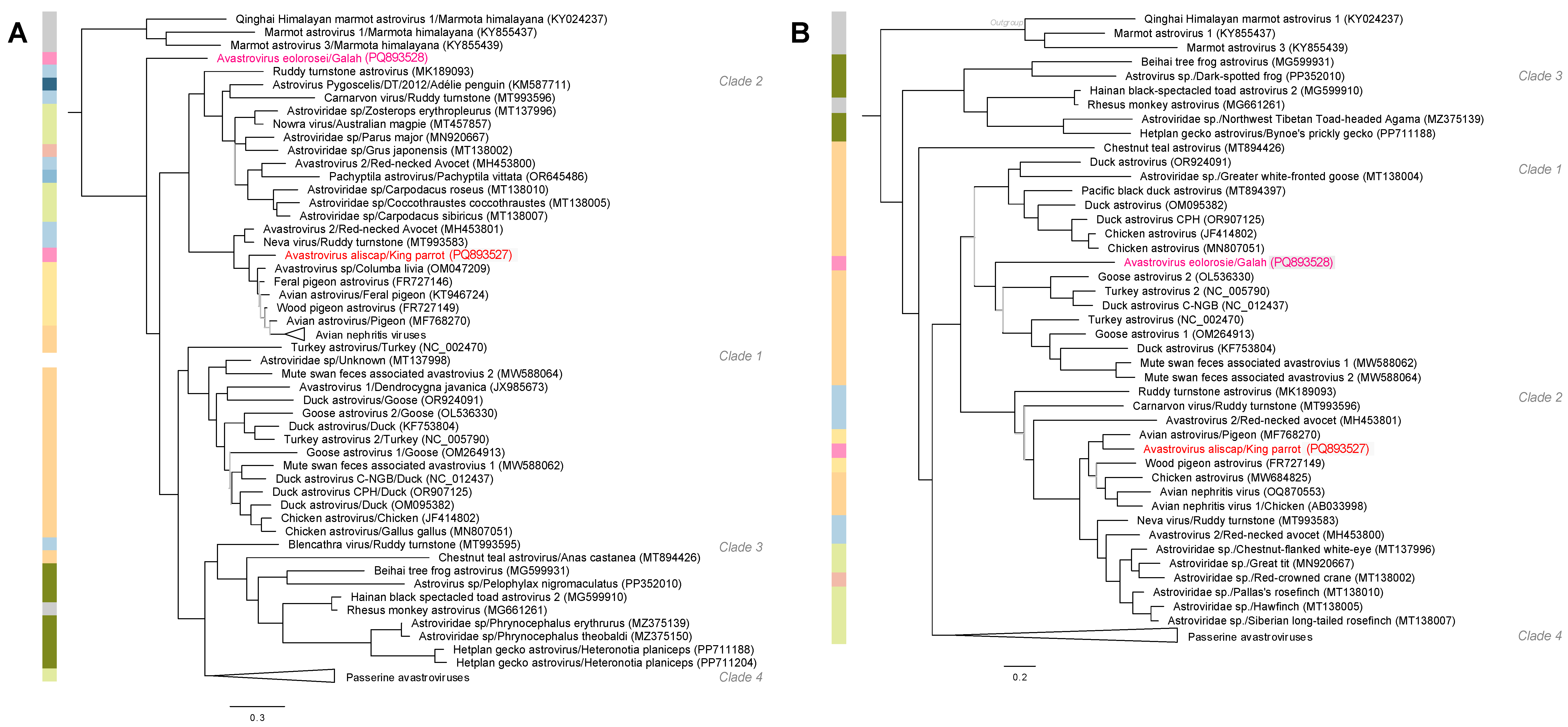

3.4. Phylogenetic Analyses

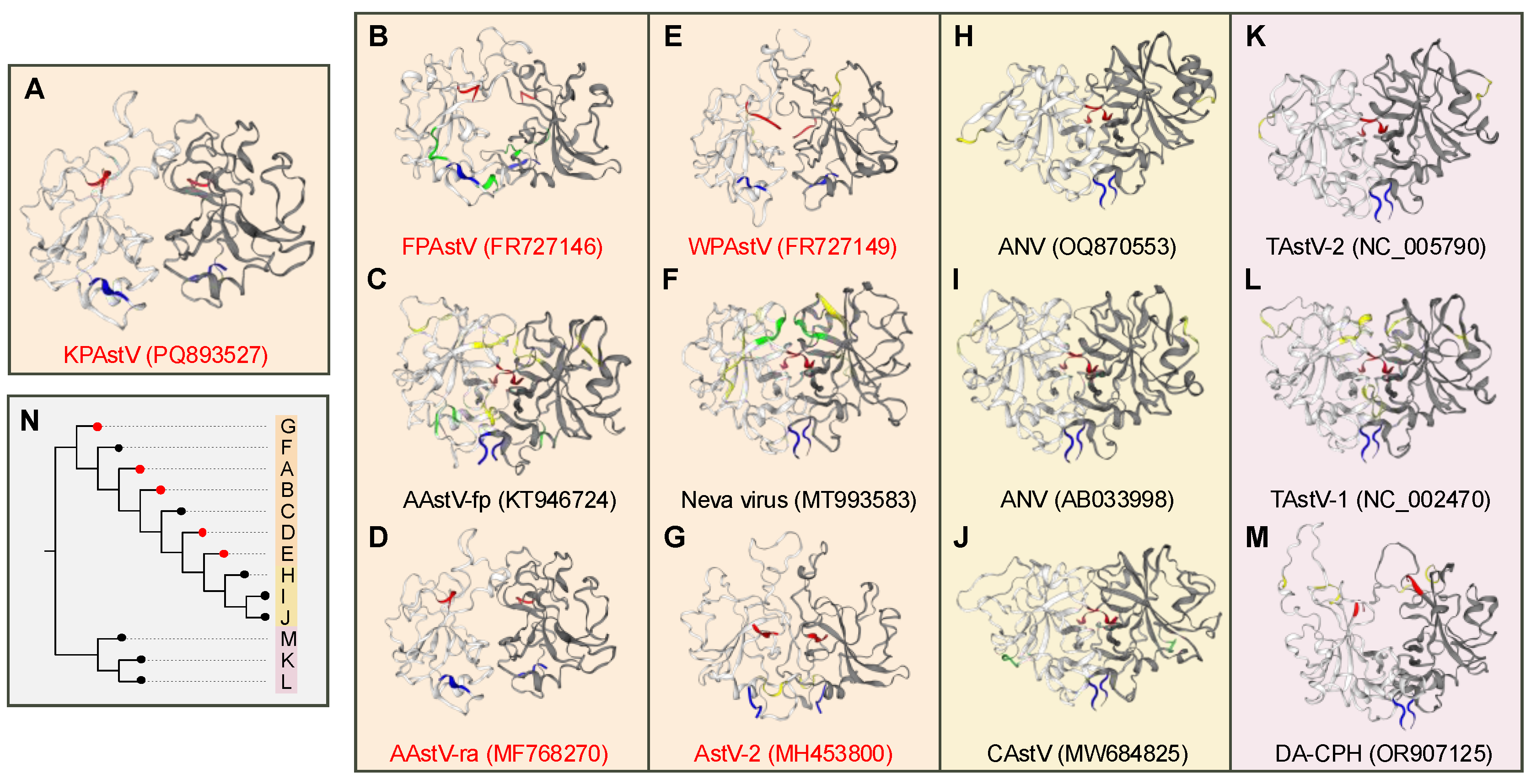

3.5. Predicitive Analyses

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shi, M.; Lin, X.D.; Chen, X.; Tian, J.H.; Chen, L.J.; Li, K.; Wang, W.; Eden, J.S.; Shen, J.J.; Liu, L.; Holmes, E.C. The evolutionary history of vertebrate RNA viruses. Nature 2018, 556, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahar, J.E.; Wille, M.; Harvey, E.; Moritz, C.C.; Holmes, E.C. The diverse liver viromes of Australian geckos and skinks are dominated by hepaciviruses and picornaviruses and reflect host taxonomy and habitat. Virus Evol. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.M.; Lefkowitz, E.; Adams, M.J.; Carstens, E.B. Virus taxonomy: ninth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, 9th ed.; Elsevier 2011; Volume 9.

- Wille, M.; Eden, J.S.; Shi, M.; Klaassen, M.; Hurt, A.C.; Holmes, E.C. Virus–virus interactions and host ecology are associated with RNA virome structure in wild birds. Mol. Ecol. 2018, 27(24), 5263–5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wille, M.; Shi, M.; Hurt, A.C.; Klaassen, M.; Holmes, E.C. RNA virome abundance and diversity is associated with host age in a bird species. Virology 2021, 561, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhu, A.L.; Yuan, C.L.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, C.X.; Lan, D.L.; Yang, Z.B.; Cui, L.; Hua, X.G. Detection of astrovirus infection in pigeons (Columbia livia) during an outbreak of diarrhoea. Avian Pathol. 2011, 40, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kofstad, T.; Jonassen, C.M. Screening of feral and wood pigeons for viruses harbouring a conserved mobile viral element: characterization of novel astroviruses and picornaviruses. PloS One 2011, 6, 25964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Correa, I.; Truchado, D.A.; Gomez-Lucia, E.; Doménech, A.; Pérez-Tris, J.; Schmidt-Chanasit, J.; Cadar, D.; Benítez, L. A novel group of avian astroviruses from Neotropical passerine birds broaden the diversity and host range of Astroviridae. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, T.; Yang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Gong, G.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Lu, J.; Zhao, M. Virome in the cloaca of wild and breeding birds revealed a diversity of significant viruses. Microbiome 2022, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, W.W.; Hall, R.J.; White, D.D.; Wang, J.; Massaro, M.; Tompkins, D.M. First report of a feather loss condition in Adelie penguins (Pygoscelis adeliae) on Ross Island, Antarctica, and a preliminary investigation of its cause. Emu 2015, 115, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimwood, R.M.; Reyes, E.M.; Cooper, J.; Welch, J.; Taylor, G.; Makan, T.; Lim, L.; Dubrulle, J.; McInnes, K.; Holmes, E.C.; Geoghegan, J.L. From islands to infectomes: host-specific viral diversity among birds across remote islands. BMC Ecol. Evol. 2024, 24, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.S.; Eden, J.S.; Hall, J.; Shi, M.; Rose, K.; Holmes, E.C. Metatranscriptomic analysis of virus diversity in urban wild birds with paretic disease. J. Virol. 2020, 94, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koci, M.D.; Schultz-Cherry, S. Avian astroviruses. Avian Pathol. 2002, 31, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Pan, M.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Xie, X.; Knowles, N.J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, D. Complete sequence of a duck astrovirus associated with fatal hepatitis in ducklings. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 1104–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, D.; Smyth, V.J.; Ball, N.W.; Donnelly, B.M.; Wylie, M.; Knowles, N.J.; Adair, B.M. Identification of chicken enterovirus-like viruses, duck hepatitis virus type 2 and duck hepatitis virus type 3 as astroviruses. Avian Pathol. 2009, 38, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantin-Jackwood, M.J.; Strother, K.O.; Mundt, E.; Zsak, L.; Day, J.M.; Spackman, E. Molecular characterization of avian astroviruses. Arch. Virol. 2011, 156, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowski, A.B. Beyond the gastrointestinal tract: the emerging and diverse tissue tropisms of astroviruses. Viruses 2021, 13, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, S.L.; Pass, D.A. Investigations of an enteric infection of cockatoos caused by an enterovirus-like agent. Aust. Vet. J. 1989, 66, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McOrist, S.; Madill, D.; Adamson, M.; Philip, C. Viral enteritis in cockatoos (Cacatua s). Avian Pathol. 1991, 20, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philbey, A.W.; Andrew, P.L.; Gestier, A.W.; Reece, R.L.; Arzey, K.E. Spironucleosis in Australian king parrots (Alisterus scapularis). Aust. Vet. J. 2002, 80, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doneley, B. Weight loss syndrome in juvenile free-living galahs (Eolopus roseicapillus). In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Australasian Association of Avian Veterinarians and Unusual and Exotic Pet Veterinarians, 9–11 January 2012.

- Tulloch, R.L.; Kim, K.; Sikazwe, C.; Michie, A.; Burrell, R.; Holmes, E.C.; Dwyer, D.E.; Britton, P.N.; Kok, J.; Eden, J.S. RAPID prep: A Simple, Fast Protocol for RNA Metagenomic Sequencing of Clinical Samples. Viruses 2023, 15, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R.; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmieder, R.; Edwards, R. Fast identification and removal of sequence contamination from genomic and metagenomic datasets. PloS One 2011, 6, 17288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopylova, E.; Noé, L.; Touzet, H. SortMeRNA: fast and accurate filtering of ribosomal RNAs in metatranscriptomic data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 3211–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.B.; Coin, L.J. Pangenome databases improve host removal and mycobacteria classification from clinical metagenomic data. GigaScience 2024, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.E.; Lu, J.; Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, C.M.; Luo, R.; Sadakane, K.; Lam, T.W. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1674–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, N.L.; Pimentel, H.; Melsted, P.; Pachter, L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchfink, B.; Reuter, K.; Drost, H.G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bushnell, B. BBMap: a fast, accurate, splice-aware aligner. 2014.

- Marchler-Bauer, A.; Bo, Y.; Han, L.; He, J.; Lanczycki, C.J.; Lu, S.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M. CDD/SPARCLE: functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D200–D203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Lu, S.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; Thanki, N.; Yamashita, R.A.; Yang, M. The conserved domain database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D384–D388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, R.D.; Clements, J.; Eddy, S.R. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W29–W37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, S.C.; Luciani, A.; Eddy, S.R.; Park, Y.; Lopez, R.; Finn, R.D. HMMER web server: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W200–W204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; Von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Brunak, S. Prediction of glycosylation across the human proteome and the correlation to protein function. In Biocomputing 2002, 2001; pp. 310–322.

- DuBois, R.M.; Freiden, P.; Marvin, S.; Reddivari, M.; Heath, R.J.; White, S.W.; Schultz-Cherry, S. Crystal Structure of the Avian Astrovirus Capsid Spike. J. Virol. 2013, 86, 7853–7863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; Lepore, R. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, G.; Rempfer, C.; Waterhouse, A.M.; Gumienny, R.; Haas, J.; Schwede, T. QMEANDisCo—distance constraints applied on model quality estimation. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1765–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, D.; Trudgett, J.; Smyth, V.J.; Donnelly, B.; McBride, N.; Welsh, M.D. Capsid protein sequence diversity of avian nephritis virus. Avian Pathol. 2011, 40, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, L.L.; Beserra, L.A.; Soares, R.M.; Gregori, F. Avian nephritis virus (ANV) on Brazilian chickens farms: circulating genotypes and intra-genotypic diversity. Arch. Virol. 2016, 161, 3455–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.G.; Netzler, N.E.; White, P.A. Ancient recombination events and the origins of hepatitis E virus. BMC Evol. Biol. 2016, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pankovics, P.; Boros, Á.; Kiss, T.; Engelmann, P.; Reuter, G. Genetically highly divergent RNA virus with astrovirus-like (5′-end) and hepevirus-like (3′-end) genome organization in carnivorous birds, European roller (Coracias garrulus). Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 71, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guy, J.S. Virus infections of the gastrointestinal tract of poultry. Poult. Sci. 1998, 77, 1166–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yang, S.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Gong, G.; Xi, Y.; Pan, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, P. Gut virome of the world’s highest-elevation lizard species (Phrynocephalus erythrurus and Phrynocephalus theobaldi) reveals versatile commensal viruses. Microbiol. Spectrum 2022, 10, e01872–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantin-Jackwood, M.; Todd, D.; Koci, M.D. Avian astroviruses. In Astrovirus Research: Essential Ideas, Everyday Impacts, Future Directions, 2013; pp. 151–180.

- De Battisti, C.; Salviato, A.; Jonassen, C.M.; Toffan, A.; Capua, I.; Cattoli, G. Genetic characterization of astroviruses detected in guinea fowl (Numida meleagris) reveals a distinct genotype and suggests cross-species transmission between turkey and guinea fowl. Arch. Virol. 2012, 157, 1329–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, D.K.W.; Leung, C.Y.H.; Perera, H.K.K.; Ng, E.M.; Gilbert, M.; Joyner, P.H.; Grioni, A.; Ades, G.; Guan, Y.; Peiris, J.S.M.; Poon, L.L.M. A Novel Group of Avian Astroviruses in Wild Aquatic Birds. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 13772–13778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigerust, D.J.; Shepherd, V.L. Virus glycosylation: role in virulence and immune interactions. Trends Microbiol. 2007, 15, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, I.A.; De Vries, R.P.; Gröne, A.; De Haan, C.A.M.; Verheije, M.H. Binding of avian coronavirus spike proteins to host factors reflects virus tropism and pathogenicity. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 8903–8912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwhab, E.S.M.; Veits, J.; Tauscher, K.; Ziller, M.; Grund, C.; Hassan, M.K.; Shaheen, M.; Harder, T.C.; Teifke, J.; Stech, J.; Mettenleiter, T.C. Progressive glycosylation of the haemagglutinin of avian influenza H5N1 modulates virus replication, virulence and chicken-to-chicken transmission without significant impact on antigenic drift. J. Gen. Virol. 2016, 97, 3193–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Yamada, Y.; Fung, T.S.; Huang, M.; Chia, R.; Liu, D.X. Identification of N-linked glycosylation sites in the spike protein and their functional impact on the replication and infectivity of coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus in cell culture. Virology 2018, 513, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Dong, L.; Méndez, E.; Tao, Y. Crystal structure of the human astrovirus capsid spike. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 12681–12686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, C.F.; DuBois, R.M. The astrovirus capsid: a review. Viruses 2017, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdanoff, W.A.; Campos, J.; Perez, E.I.; Yin, L.; Alexander, D.L.; DuBois, R.M. Structure of a human astrovirus capsid-antibody complex and mechanistic insights into virus neutralization. J. Virol. 2017, 91, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, A.; Pintó, R.M.; Guix, S. Human astroviruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 1048–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; Hargest, V.; Cortez, V.; Meliopoulos, V.A.; Schultz-Cherry, S. Astrovirus pathogenesis. Viruses 2017, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thouvenelle, M.L.; Haynes, J.S.; Reynolds, D.L. Astrovirus infection in hatchling turkeys: histologic, morphometric, and ultrastructural findings. Avian Dis. 1995, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, J.J.; Dam, G.T.; de Laar, J.V.; Biermann, Y.; Verstegen, I.; Edens, F.; Schrier, C.C. Detection and characterization of a new astrovirus in chicken and turkeys with enteric and locomotion disorders. Avian Pathol. 2011, 40, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, Y.M.; Guy, J.S.; Day, J.M.; Cattoli, G.; Hayhow, C.S. Viral enteric infections. Dis. Poult. 2020, 401–445. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Luo, J.; Shang, J.; Zhang, F.; Deng, C.; Feng, Y.; Meng, G.; Jiang, W.; Yu, X.; Liu, H. Epidemiological investigation and pathogenicity analysis of waterfowl astroviruses in some areas of China. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1375826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.R.; Morfopoulou, S.; Hubb, J.; Emmett, W.A.; Ip, W.; Shah, D.; Brooks, T.; Paine, S.M.; Anderson, G.; Virasami, A.; Tong, C.W. Astrovirus VA1/HMO-C: an increasingly recognized neurotropic pathogen in immunocompromised patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G.L.; Braun, E.J. Postrenal modification of urine in birds. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1985, 248, R93–R98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, Import risk review for psittacine birds from all countries – draft review, Canberra, July 2020. CC BY 4.0. Available online: https://www.agriculture.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/draft-psittacine-review-for-public-comment.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2024).

| Alignment | Mean±SD %ID | GAstV | KPAstV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RdRp domain | Clade 1 (poultry) | 61.68±1.59 | 58.10±2.06 | |

| Clade 2 (diverse) | 61.68±3.13 | 71.41±9.26 | ||

| Clade 3 (herp) | 51.37±5.14 | 48.82±3.14 | ||

| Clade 4 (passerine) | 59.61±1.83 | 55.09±1.66 | ||

| Outgroup (marmot) | 46.36±1.52 | 45.45±0.23 | ||

| Maximum ID | 65.2a | 83.53b | ||

| Capsid precursor domain | Clade 1 (poultry) | 39.30±2.99 | 38.18±1.94 | |

| Clade 2 (diverse) | 46.11±1.62 | 37.93±8.22 | ||

| Clade 3 (herp) | 31.33±1.83 | 35.28±2.28 | ||

| Clade 4 (passerine) | 36.82±1.86 | 44.76±1.83 | ||

| Outgroup (marmot) | 27.09±1.03 | 25.46±2.18 | ||

| Maximum ID | 47.28c | 74.22b | ||

| Complete ORF2 | Clade 1 (poultry) | 28.81±3.71 | 24.09±4.03 | |

| Clade 2 (diverse) | 22.79±1.00 | 46.26±08.28 | ||

| Clade 3 (herp) | 19.39±5.66 | 19.44±7.47 | ||

| Clade 4 (passerine) | 19.78±3.08 | 18.29±3.54 | ||

| Outgroup (marmot) | 7.75±0.48 | 6.71±0.46 | ||

| Maximum ID | 35.17d | 58.57b | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).