1. Introduction

Biogas is a mixture of CH4 and COE, so energy use to produce electricity has economic and environmental benefit. For a more profitable management of this energy source, it is necessary to consider the variation of rates in order to achieve a more convenient production, although this requires some retention capacity of biogas. However, as most renewable energy plants, it has a small storage capacity, increasing the uncertainty of the amount of fuel available. In this paper, the results of a model to support the short-term management of this energy source are presented, modelling the technical-economic behaviour and constraints by a problem of programming nonlinear mathematics with constraints. This study is essential, as it carries out risk analyses from a commercial point of view, not forgetting that the infrastructures properly framed in the region serve and have an effective connection to their users decisiveness.

This communication is a contribution to the optimisation of the management of electricity from the use of biogas. In the second point, the formalism for a computer application that simulates the technical-economic behaviour of the short-term management of biogas for the conversion of electricity is presented, and the mathematical model is formulated as a mathematical programming problem with constraints. In the third point, a simulation for a case study of short-term management is presented. In the last point, the main conclusions are presented.

One of the main objectives of waste policies is to ensure that waste has an appropriate purpose, thereby reducing risks to human health and to the environment. Thus, it is essential that waste is properly separated and classified at source, so that its final destination is the most appropriate and the least harmful to both parties. The priority objective of waste policy is to prevent and reduce risks to human health and the environment by ensuring that waste management is carried out using processes or methods that are not likely to have adverse effects on the environment, such as pollution of water, air, soil, effects of fauna and flora, noise or odours or damage to any places of interest and the landscape. In this way, it is essential that waste is properly separated and classified at source [

1].

Waste management practices vary between EU Member States. The EU wants to promote waste prevention and the reuse of products as much as possible. If this is not possible, preference is given to recycling (including composting), followed using waste for energy production. The most harmful option for the environment and people's health is simply the disposal of waste which is, for example, landfilled, although this is also one of the cheapest possibilities. In October 2022, Parliament approved a revision of the rules on persistent organic pollutants (POPs) to reduce the amount of harmful chemicals in waste and production processes. The new rules introduced stricter limits, banned certain chemicals and kept pollutants separate from recycling [

2]. In February 2021, Parliament had already adopted a resolution on the new circular economy action plan calling for additional measures to achieve a carbon-neutral, sustainable, toxic-free and fully circular economy by 2050, including stricter recycling rules and mandatory targets for the use and consumption of materials by 2030 [

3]. In November 2023, Parliament adopted its negotiating position on the revision of EU rules on packaging and packaging waste. MEPs want to ban the sale of very lightweight plastic carrier bags, set specific targets for reducing plastic packaging waste, encourage reuse and replenishment options and ban persistent pollutants used in food packaging. This is still ongoing [

4,

5].

The preservation of resources and the promotion of sustainable economic growth must be achieved by replacing the concept of a linear economy with a circular one, based on decentralised recycling. Decentralised composting such as domestic and community is a biologic treatment for biowaste that can be applied in urban areas. However, [

6] presents an alternative study. The process of using energy starts with the collection of waste itself, which is then composed and followed by transport to the places of consumption, where direct combustion is carried out by replacing the use of fossil fuels. Industries in the forestry sector have been using biomass to produce thermal and electrical energy for about 30 years. The energy ratio of 1 ton of wood is equivalent to 0.359 toe (ton of oil equivalent) for conifers or 0.331 toe for broadleaves. The calorific value of the biomass produced annually in Portugal is about two million toes [

7].

In Portugal, in the last decade, there has been a major change in the urban MSW policy, with about 341 existing landfills being closed and recovered, and 37 landfills built in their place. At the same time, the management of MSW, which until 1994 was the exclusive responsibility of the local authorities, has been open to public and private concessionaires, contributing to the improvement of the services provided to the users of the systems and to the strengthening of investment capacity. It can be considered that the main objectives of a first phase of PERSU have been achieved, which consisted of eradicating garbage dumps and providing the country with basic and essential infrastructures in terms of MSW management. The second phase, which is in progress, focuses heavily on optimising the management of the systems already built, with the technical, human and financial resources available, correcting operational dysfunctions through the evaluation and analysis of their performance. In July 2003, the Ministry of Cities, Spatial Planning and Environment presented the "National Strategy for the Reduction of Biodegradable Urban Waste to Landfills", which systematised the projections of waste generation and outlines the guidelines for a balanced management, with an emphasis on the objectives of recycling and recovery using the best available technologies. Public-private partnerships in areas such as biodegradable waste are also being put forward.

In addition to complying with the legislation in force, the use of biogas to produce electricity is an added value for the concessionaires of waste treatment and final destination units, as this alternative energy source can provide not only self-sufficiency in electricity for these units, but also the export of surplus energy to the National Electricity Grid, thus contributing to the self-sustaining management that is intended for these infrastructures.

2. Landfill

It is a waste disposal structure that must have, among others, a collection and treatment system that prevents the pollution of groundwater (providing a correct route to harmful products) and a system for capturing and burning biogas to prevent it from polluting the atmosphere.

Figure 1 shows the burner installed in the Leiria landfill, which served as the basis for this study. The biogas burning unit and the adaptation of the landfill costed around 1.5 million euros, in a project that was completed about a year ago. In order to prevent its saturation, a siphon connection was created to a reservoir from which the accumulated condensate was collected. A sweeping line will also be installed to clean condensate that may exist in the connection branches. When the closing level is reached, the wells are headed and connected to the perimeter pipeline (see

Figure 2). To reduce the visual impact, the slopes are sealed with a layer of clay soil regularisation and with a 2.0 mm HDPE geomembrane. At the Leiria landfill, the production of biogas was qualitatively monitored throughout the degassing process using a biogas analyser and a thermal anemometer. The biogas analyser measured the content of methane (CH4), oxygen (02), carbon dioxide (CO2) and, in ppm, carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen sulphide (H2S). By difference, the "balance gas" is determined, mostly nitrogen (N2). To verify the biogas production potential of the waste deposited in the Leiria landfill and the feasibility of its energy use, there are several theoretical models that allow the estimation of the production (see

Table 1). The biogas production estimate was obtained using the "Landfill Gas Emission Model" (LandGEM) developed by the Control Technology Center of the U.S. EPA, based on first-order kinetics. This model assumes that biogas production is more intense in the period immediately after the waste is landfilled, and that production decreases thereafter [

8,

9].

The equation of the model and the variables involved in it are as follows:

where:

OCH4 = Methane produced in the calculation year (m3/year)

LO = Methane production potential (m3/tonne of waste)

R = Average annual deposition over the working life of the landfill (tonlan)

K = Methane production rate (year-I)

c = Time since landfill closure (year)

t = Time since landfill start-up (year)

The values used for the above variables were those recommended by the EPA for landfill emissions without specific data: Lo = 170 m3/Mg of refuse and K = 0.05 l/year.

The converter system used to use this energy source for energy production consists of an alternator coupled to an internal combustion engine powered by biogas.

3. Short-Term Management

Biogas is a mixture of CH4 (40 to 60 %), CO2 (20 to 40 %) and N2 (2 to 20 %), and there may also be some H2S (4 to 100 ppm). The production of biogas varies over the years as waste decomposes. CH4 is a gas about twenty-one times more harmful than CO2 from the point of view of the greenhouse effect [10-12]. The management of energy use of biogas for conversion to electricity leads to economic valorisation from the sale of electricity [

12], with prices better than those of conventional sources, or possibly in the future, to the value of green certificates, which are already in operation in some European countries. Moreover, because CH4 is more harmful than CO2 from the point of view of the greenhouse effect, its use as a fuel represents an environmental benefit.

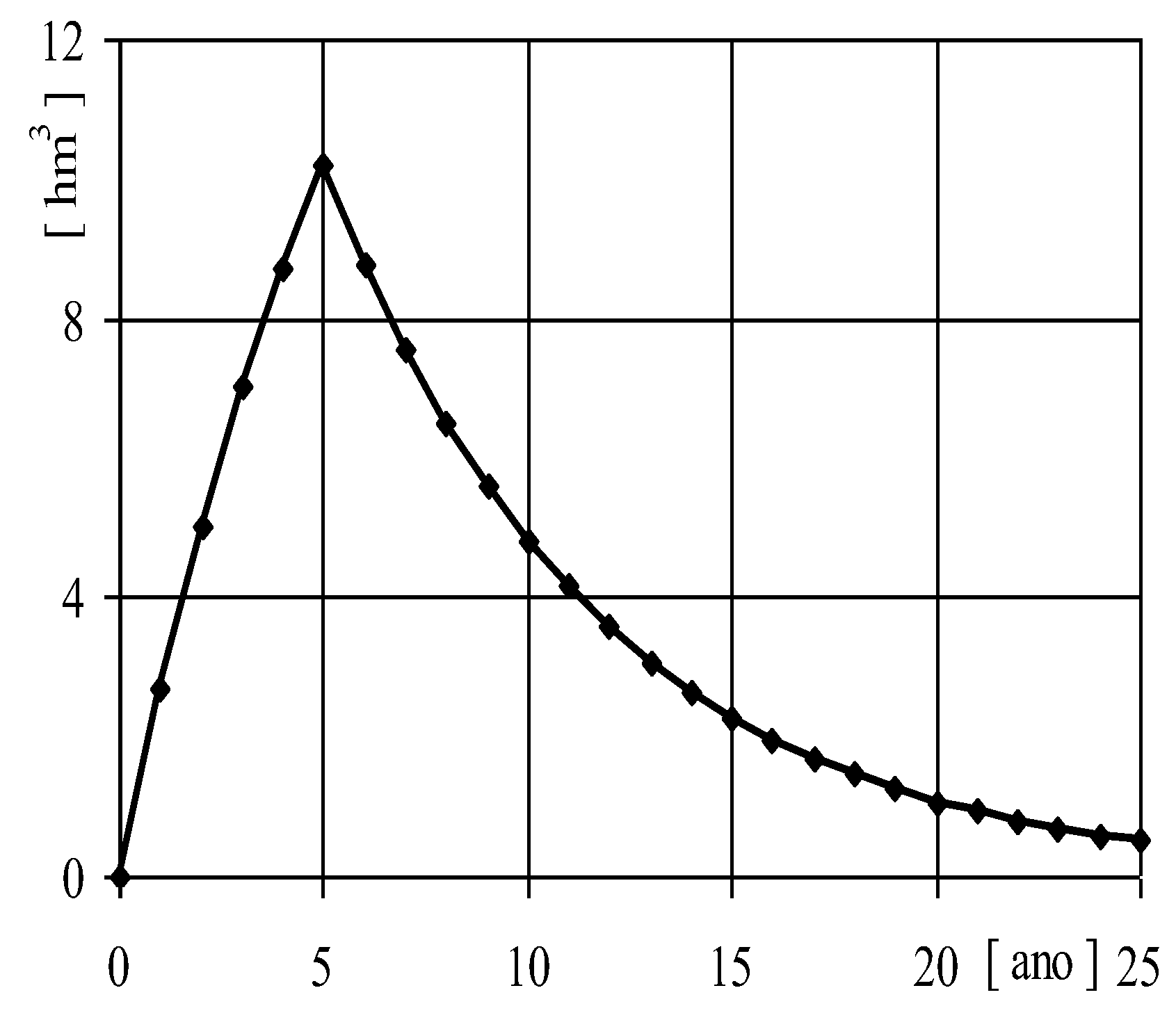

In this communication, a computer application for the management of this energy source in the short term is described, considering the price variation and the CH4 emission estimated using the history and/or particularly in a design phase to the USEPA LandGEM model [

13], which corresponds to the typical curve illustrated in

Figure 4. The behaviour of the technical-economic mechanism game is modelled by a nonlinear mathematical programming problem with constraints, using the notation presented below.

J – Set of indices of restrictions by stadium.

N – Set of indices n of constraints over the time horizon.

K – Set of indices k of the stages of the time horizon.

Ajk – A set of units that must satisfy the constraint j at the stage k.

Bn – A set of units that must satisfy constraint n over the time horizon.

Cik – Biogas consumption in the operation of unit I at stage k.

Xio – Set of possible initial states for unit i.

Xif – Set of possible end states for unit i.

Xik – State variable of unit I at stage k.

X – Vector of state variables over the time horizon.

Uik – Integer decision variable for unit I at stage k.

U – Vector of the integer decision variables over the time horizon.

Pik – Electrical power in unit at stage k.

Dk – Electrical power associated with own consumption of electricity at stage k.

P – Vector of electrical powers of the units over the time horizon.

Fik – State transition function of unit i at stage k.

Pik – Set of possible powers for unit I at stage k.

λ - Vector whose coordinates are the energy prices at each stage.

The short-term management for the conversion of biogas energy into the form of electrical energy consists of establishing a possible plan for the operation of the units, and decisions can be made in one-hour stages over a time horizon of one day to one week, corresponding to the daily cycle and the weekly cycle of electricity demand. Some data necessary for the characterisation of the short-term management are by nature stochastic, but given that the time horizon is short-term, the estimated values are considered. Thus, the decision-making support system is described by a deterministic mathematical programming problem. The objective function is the total economic benefit obtained over the time horizon calculated by:

The consumption of biogas, used in the conversion, contains two parts: one determined by the amount of fuel that is required for the unit to start, i.e., the unit is brought to operating conditions that allow the conversion of energy; and another portion, determined by the amount of fuel whose energy is actually used to be converted to the form of electrical energy. Consumption at start-up is neglected in the formulation, but can easily be considered if necessary. The quantity of fuel whose energy is actually used to be converted into the form of electrical energy, said to be consumption with operation, is in this communication approximated by a Taylor series up to the second order expressed by:

The data for the parameters may differ from stage to stage, considering variations in the biogas gas mixture over the time horizon. Similarly, the level of pollutant emission of a unit will be approximated by a Taylor series until the second order expressed by:

Thus, the problem for short-term management is the maximisation of the objective function (1), which is subject to constraints such as, for example, if there is more than one unit, it can be classified into global and local. For example, limiting the level of cumulative pollutant emissions over a period is a global constraint.

Constraints can be further classified into single-stage constraints and constraints over the time horizon. An example of a global restriction involving only one stage is the limited biogas consumption in each stage for a set of Ajk units (4). On the other hand, an example of an overall restriction over the time horizon is the limited pollutant emission over the time horizon (5).

Local restrictions can be impositions on the value of unit state variables that are determined by the unit state transition function:

Impositions on the power level of the units, such as power between a minimum value and the maximum possible power value, if the unit is operating, otherwise zero:

Impositions on possible start and end states:

Constraints (4) to (8) define the set of plans for short-term management that are possible:

{(x, u, p): restrictions (4), (5) . . . (8) are met} and constraints (6), (7) and (8) define the set of plans for the operation that are locally possible, i.e., they define the set of plans that satisfy the local constraints, but not necessarily the global ones.

3. Case Study

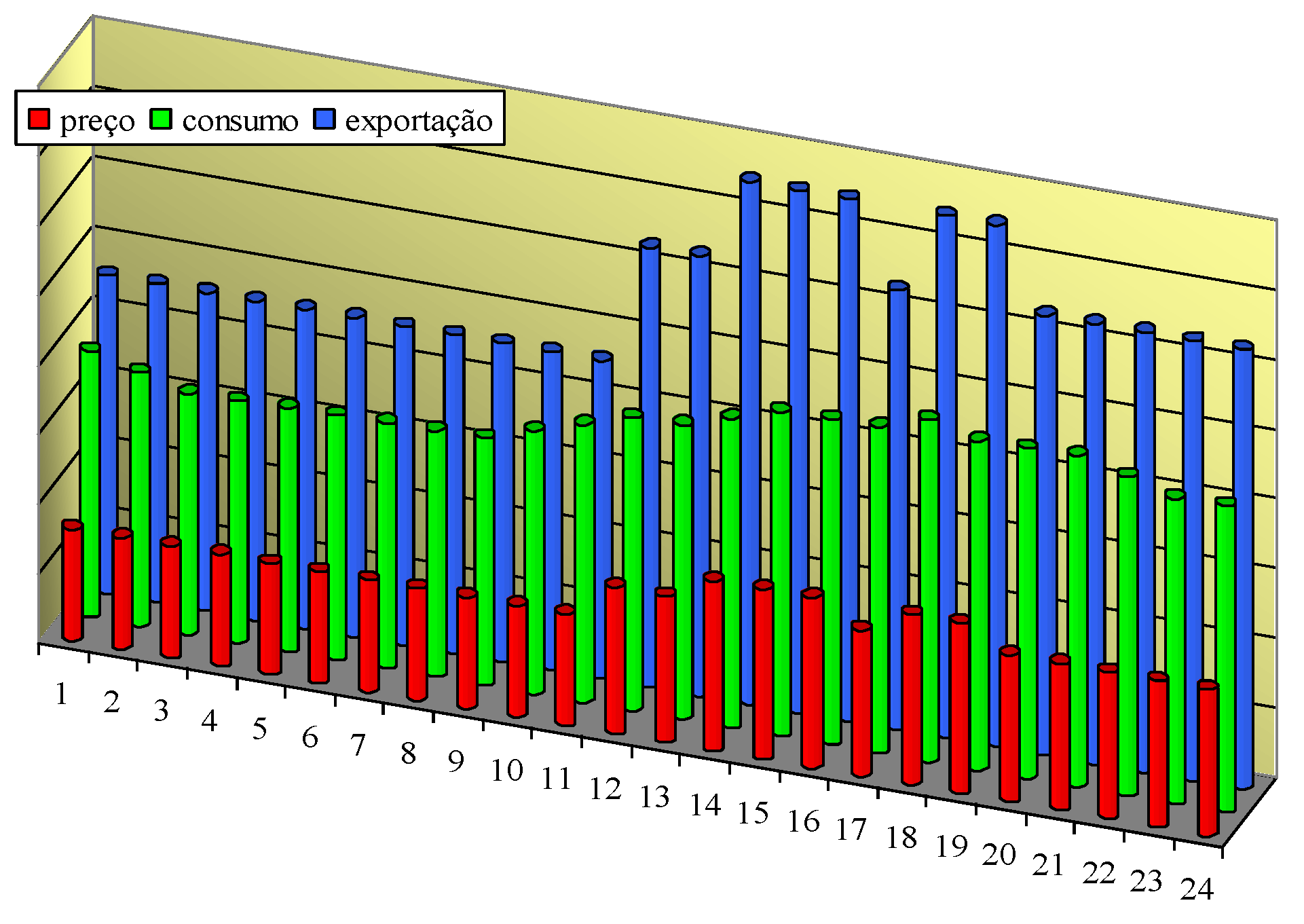

Consider a biogas use with only one converter unit with a maximum electrical power of 400 kW, with the horizon of short-term management being a day with decisions made by hour. Prices for electricity are shown in the '

price' columns in

Table A1 in Appendix.

Consider the following restrictions: maintain the use in conversion during the 24 hours; satisfy the consumption of own electricity, the power of which is indicated in columns '

d', exporting the remaining energy for sale according to the prices; respect the forecast of 3000 units of available volume of biogas during the 24 hours, using in each hour a quantity of not less than 30 and not more than 220 units of volume, the total pollutant emission at the end of the 24 hours does not exceed 3500 mass units. Also, consider the following data that characterise, respectively, the biogas consumption with the operation of the unit (2) and the level of pollutant emission (3).

The optimal plan for the 24 hours is shown in

Table A1. Series: pollutant emission,

'emi' columns; electrical power of the unit, '

p' columns; economic profit from the sale of electricity, '

$' columns.

Figure 3 illustrates the evolution of prices, biogas consumption and electricity exported in each hour over the 24 hours. The results allow us to conclude that at no time should the unit be at maximum power for a proper management of the available biogas. With this computer application, not only is the excellence of the decisions supported, but also the excessive use of biogas, compromising the permanence in operation of the unit due to a lack of biogas availability. Therefore, the constraints of the problem ensure the admissibility of the decision, as there is no possible decision without it. By trial and error, it is difficult to obtain the appropriate decisions or even an admissible decision that does not jeopardise the future operation of the conversion.

Figure 3.

Price, biogas consumption and electricity exports.

Figure 3.

Price, biogas consumption and electricity exports.

Figure 4.

Amount of CH4 produced.

Figure 4.

Amount of CH4 produced.

5. Conclusions

The advantages of this valorisation are the use of a renewable resource, that is low cost, contains no sulphur dioxide emissions, leads to a significant reduction of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions into the atmosphere, is less aggressive to the environment than fossil fuels, leads to less corrosion on equipment (boilers, furnaces, among others), consist of a lower environmental risk and is less likely to caught fire (by encouraging the clearing of forests).

The disadvantages are the lower calorific value of the biomass, difficulties in storage and the risk of overexploitation of the forest.

A decision-making support system that allows the excellence of the economic benefit in the short-term management of biogas, considering the pollutant emission is presented in this communication. The system, describing the play of technical-economic mechanisms, is formulated as a nonlinear mathematical programming problem with constraints.

Biogas is a mixture that contains CH4 and CO2, and its energy use in the conversion to the form of electrical energy not only leads to economic benefit, but also to environmental benefit, as CH4 is more harmful than CO2 from the point of view of the greenhouse effect.

For an adequate management of this energy use, it is necessary to project the characteristics and availability of biogas and the prices of electricity. In addition, it may be necessary to retain biogas in a few hours to be used in more favourable periods.

Data Availability Statement

All the data can be provided by request to the corresponding author Nuno Domingues.

Conflicts of Interest

Author declares no competing interests.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Short-term management, 24 hours.

Table A1.

Short-term management, 24 hours.

| h |

d |

gas |

gmin |

gmax |

emi |

preço |

p |

$ |

h |

d |

gas |

gmin |

gmax |

emi |

preço |

p |

$ |

| 1 |

19 |

85 |

30 |

220 |

95 |

0,080 |

228 |

17 |

13 |

21 |

141 |

30 |

220 |

141 |

0,105 |

315 |

31 |

| 2 |

18 |

85 |

30 |

220 |

95 |

0,080 |

228 |

17 |

14 |

22 |

188 |

30 |

220 |

181 |

0,122 |

374 |

43 |

| 3 |

17 |

85 |

30 |

220 |

95 |

0,080 |

228 |

17 |

15 |

23 |

188 |

30 |

220 |

181 |

0,122 |

374 |

43 |

| 4 |

17 |

85 |

30 |

220 |

95 |

0,080 |

228 |

17 |

16 |

23 |

188 |

30 |

220 |

181 |

0,122 |

374 |

43 |

| 5 |

17 |

85 |

30 |

220 |

95 |

0,080 |

228 |

17 |

17 |

23 |

141 |

30 |

220 |

141 |

0,105 |

315 |

31 |

| 6 |

18 |

85 |

30 |

220 |

95 |

0,080 |

228 |

17 |

18 |

25 |

188 |

30 |

220 |

181 |

0,122 |

374 |

43 |

| 7 |

18 |

85 |

30 |

220 |

95 |

0,080 |

228 |

17 |

19 |

24 |

188 |

30 |

220 |

181 |

0,122 |

374 |

43 |

| 8 |

18 |

85 |

30 |

220 |

95 |

0,080 |

228 |

17 |

20 |

24 |

141 |

30 |

220 |

141 |

0,105 |

315 |

31 |

| 9 |

18 |

85 |

30 |

220 |

95 |

0,080 |

228 |

17 |

21 |

24 |

141 |

30 |

220 |

141 |

0,105 |

315 |

31 |

| 10 |

19 |

85 |

30 |

220 |

95 |

0,080 |

228 |

17 |

22 |

23 |

141 |

30 |

220 |

141 |

0,105 |

315 |

31 |

| 11 |

20 |

85 |

30 |

220 |

95 |

0,080 |

228 |

17 |

23 |

22 |

141 |

30 |

220 |

141 |

0,105 |

315 |

31 |

| 12 |

21 |

141 |

30 |

220 |

141 |

0,105 |

315 |

31 |

24 |

22 |

141 |

30 |

220 |

141 |

0,105 |

315 |

31 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

3000 |

720 |

5280 |

3080 |

? |

6906 |

645 |

References

- European Commission, Commission decision of 18 December 2014, amending Decision 2000/532/EC on the list of waste pursuant to Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, 2014/955/EU.

- European Union, 2019, regulation (EU) 2019/1021 of the European Parliament And Of The Council of 20 June 2019 on persistent organic pollutants (recast), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32019R1021.

- European Commission, Circular economy action plan, https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/circular-economy-action-plan_en.

- European Commission, Reducing carbon emissions: EU targets and policies, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20180305STO99003/reducing-carbon-emissions-eu-targets-and-policies.

- European Commission, Sustainable waste management: what the EU is doing, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20180328STO00751/sustainable-waste-management-what-the-eu-is-doing.

- Santos M. T., Freitas F., Lamego P., and Teodoro T., Sustainable Composting of Garden and Food Waste in Higher Education Institution, 3rd Int'l Conference on Challenges in Engineering, Medical, Economics and Education: Research & Solutions (CEMEERS-24a) March 7-8, 2024 Porto (Portugal).

- EGF – Empresa Geral do Fomento, S.A. Feasibility study for the energy use of biogas in the Leiria Sanitary Landfill. Lisbon (2002).

- Domingues, N., The hidden costs of electricity and their impact in the system, 2012 International Conference on Smart Grid Technology, Economics and Policies, SG-TEP 2012, 2012, 6642399.

- António Guerra, Cláudio de Jesus, “Energy Recovery of Biogas from the Leiria Landfill”, 11º ENaSB, Faro (2004).

- Christopher Eden, “Garraf landfill site – Power generation from landfill gas”, 4as Jornadas Internacionais de Resíduos, Leiria (2003).

- Domingues, N., Industry 4.0 in maintenance: Using condition monitoring in electric machines, 2021 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Application, DASA 2021, 2021, pp. 456–462.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Land, Waste, and Cleanup Topics, https://www.epa.gov/environmental-topics/land-waste-and-cleanup-topics.

- Tabasaran, O., Uberlegungen zum Problem Deponiegas. Müll und Abfall, Vol 7, 1976.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).