1. Introduction

In landfills, municipal solid waste (MSW) is often decomposed under anaerobic conditions, during which landfill biogas is formed [

1,

2]. Methane (CH

4) and carbon dioxide (CO

2) dominate in this biogas [

1,

3,

4]. Based on the data of other scientists, it was found that as much as 16% of methane is released into the atmosphere when organic waste rots in landfills. Reducing methane emissions is essential in the fight against climate change. It must be implemented at global and European levels, as set out in 2030 in the impact assessment of the climate goals plan. This assessment states that to achieve the goal by 2030 and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55%, the methane emissions must be reduced, considering the goals of the Paris Agreement. The Glasgow Climate Pact includes a global mitigation target of 2030 year: to reduce CO

2 emissions by 45%, the emissions of methane and other greenhouse gases. In addition to the mentioned (CH

4 and CO

2), different greenhouse gases (up to 2–10%) are released from landfills. In addition to the above-mentioned chemical compounds, these gases contain nitrogen, oxygen, ammonia, sulfides, hydrogen, and others [

5].

Eurostat data shows Lithuania's annual MSW generation shows a rather stable value of around 1.3 million tonnes since 2016 and 1.35 million tonnes in 2020. Waste generation per capita slowly increased from 444 kg/cap in 2016 to 483 kg/cap in 2020 but remains under the (estimated) EU average of 505 kg/cap. Lithuania reduced its reliance on landfilling by heavily increasing the mixed municipal waste treatment capacity, including mechanical biological treatment (MBT) and incineration (with energy recovery) [

6]. For that purpose, looking for new, more advanced ways of managing such waste is necessary. A truly sustainable landfill is one in which waste materials are safely assimilated into the surrounding environment, whether or not they have been treated by biological, thermal, or other processes, and which manages gas-related problems to minimize the environmental impact. In addition, such a landfill must meet all environmental requirements. Based on literature sources [

7], the design of an engineering landfill is considered a technical measure, and management measures such as the separation of organic and inorganic waste can be seen as an effective waste management strategy. There are many publications on sustainable landfills about innovative methods to reduce energy consumption, implementing horizontal landfill aeration, or applying the zero-waste concept [

8,

9,

10].

Interesting facts can be found when analyzing the models of sustainable landfills. That is, how to change landfill processes into useful ones and put them into practice. For example, during the operation of landfills, they will produce biogas under anaerobic conditions, which can be used as a renewable energy source. Such a sustainable landfill would provide an effective gas extraction idea to improve the energy extraction needs of the surrounding residential areas, which could give the citizens economic benefits from landfills.

In addition, if rapid biodegradation of organic waste is required, then it is necessary to maintain aerobic conditions in landfills. During the latter process, there is an opportunity to make compost quickly. Compost produced in this way saves money by ensuring the operation is sustainable and environmentally friendly. Such aerobic pretreatment of MSW reduces waste mass and improves environmental processes in landfills. Other measures in waste management processes, such as probiotic injection, filtrate recirculation, and choosing an effective biocover, can be attributed to a sustainably managed landfill. For example, filtrate recirculation ensures better nutrient distribution and adequate moisture content. Biocover is one of the aspects of innovative technologies for reducing methane emissions from landfills and achieving landfill sustainability through remediation. The studies of other researchers [

8,

9,

10] confirmed that a higher amount of leachate and a dose of probiotics can maintain a higher and more stable methane concentration. In summary, a sustainable landfill is one in which all physicochemical and biochemical processes are harmonious. Therefore, the operation of such a landfill is little harmful or completely harmless to the environment [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

The main objective of the experimental study was to evaluate the influence of aeration, probiotic introduction, and water supply on the production of landfill gases (CO2, CH4, N2, H2, etc.) in the different fifth landfills’ models during the management of MSW and to propose the best solutions for reducing environmental pollution.

2. Materials and Methods

The main challenge in mechanical-biological treatment (MBT) municipal solid waste (MSW) research is to predict the total production of biogas (methane, carbon dioxide, etc.) and their cleaning from pollutants so that the operation of different landfills does not harm the environment. After landfilling, MSW goes through degradation and is affected by bacteria. Generally, this works under aerobic conditions, but overlying layers hold the airflow as more MSW is added, and the dominant biochemical reactions become anaerobic. This study analyzes the behavior of different landfill model implementations for various practical situations. The in-situ treatment processes include anaerobic, aerobic, and aerobic-anaerobic bioreactor technology.

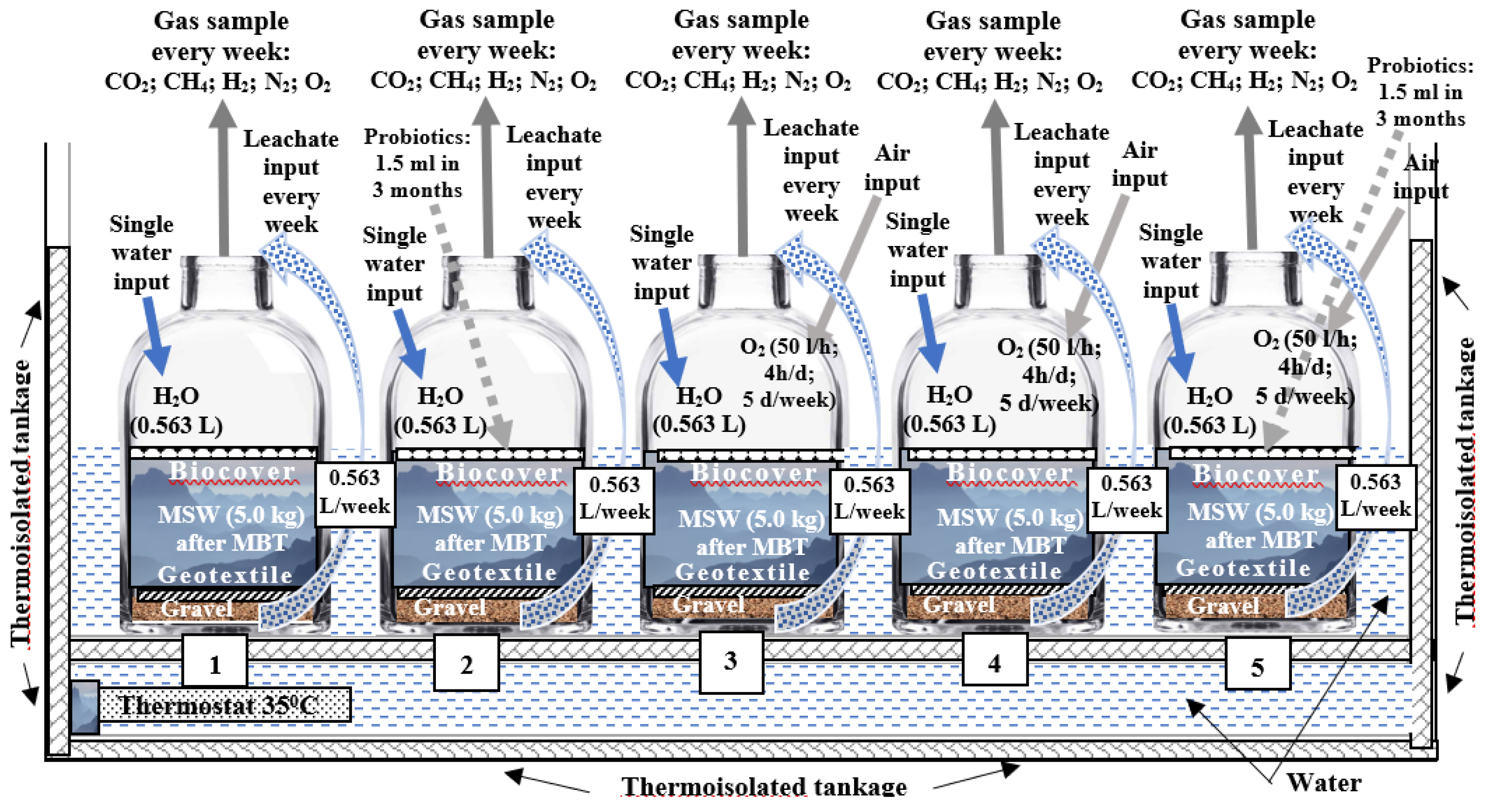

The five plastic bottles (with a capacity – of 19 liters) were used as five landfill models with different conditions during research. Each of them was filled with MSW (5 kg), which consisted of paper/cardboard (9%), wood waste (3%), textile waste (6%), food waste (21%), green waste (19%), plastic packaging (12%), metal packaging (2.8%), glass packaging (6.8%) inert waste (10.2%), other non-hazardous MSW (8%), composite packaging (2.2%). Before placing in the experimental bottles, all wastes were mechanically treated (i.e., crushed and mixed) as they are normally received in a landfill. Waste was held in experimental bottles for 120 days. The technological scheme of the landfill models (anaerobic; anaerobic with a dose of probiotics; aerobic; aerobic-anaerobic; aerobic-anaerobic with a dose of probiotics.) is shown in

Figure 1, in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

All bottoms of each bottle were filled with gravel (suitable for drainage), on which a layer of geotextile was placed. The prepared waste was composed in the bottles on the mentioned layers. Later, it was covered by a year-old, high-quality, stable layer of compost (called biocover). This biocover for all models consisted of biodegradable waste such as tree branches, grass, etc. These layers correspond to the structures of the real landfill.

These bottles were closed and installed into a thermoisolated tankage filled with water. The water was kept at a constant temperature of 35 °C and measured by a thermostat, which in these bottles would be a favorable growth environment for the microorganisms in them. The third, fourth, and fifth Landfill models that required aeration were additionally equipped with aerators.

Every week, all of the gases that were generated inside five landfill models were collected into a “Teddlar” gas sampler bag and transported to gas monitoring equipment – “Inca” and “Drager”, which showed gasses like CO2 (%), CH4 (%), O2 (%), H2 (%), N2 (%) concentrations. The five different landfill models had different conditions and experimental parameters.

Probiotics were used in experimental studies. The probiotics were produced through natural fermentation but not chemically synthesized or genetically engineered. These probiotics in the liquid phase were created through natural fermentation using beneficial and effective microorganisms. The general benefits of probiotics injection were:

to increase the productivity of the waste stabilization process;

to improve air quality by increasing the biodegradability and fermentation of the waste;

to achieve reductions of odors from landfill models.

Water (0.563 L) was supplied to each landfill model during the experiments. The collected air emissions were analyzed every week. At the same time, the collected filtrate was returned to each landfill model and reused in its irrigation process. Anaerobic conditions were maintained in the first and second landfill models. The second and fifth landfill models were additionally filled with 1.5 ml of “Odor Away” probiotics. Aerobic conditions were left in the third landfill model. The fifth landfill model maintained aerobic-anaerobic conditions. The third, fourth, and fifth landfill models were supplied with 50 L of O

2 (four hours per day and five days per week). This landfill models have an air compressor called “Oxyboost 100”. All experimental parameters of the five different landfill models during the study are given in

Table 2.

The leachate was recirculated once a week. To produce leachate, 0.563 L of clean water (

Table 2) was added to all landfill models filled with leachate. The study used leaching as a closed recirculation system in all landfill models to increase the waste's biodegradability. All landfill models were equipped with four ports. One port was used for drainage. The other two ports were used to collect gas samples and inject liquid and air.

The biological oxygen demand (over 5 days) (BOD

5) was measured according to the analysis method specified in the Lithuanian environmental document LAND 21-01 [

41]. The chemical oxygen consumption (COD) was measured using the fixed titrimetric method. The index of bichromatic oxidation was conducted using the thermoreactor Eco-6 of Velp Scientifica (Italy). Excess oxidizer was titrated according to the methodology approved by LAND 83-2006 [

42].

The average experimental results were calculated from three replicates of each experimental treatment and reported as the mean ± standard deviation. The data were analyzed using a variance analysis, and only values with a p-value less than 0.05 were considered acceptable. A variance analysis was performed to determine how the concentrations of the analyzed gas emissions from different landfill models changed over 120 experimental days.

3. Results and Discussion

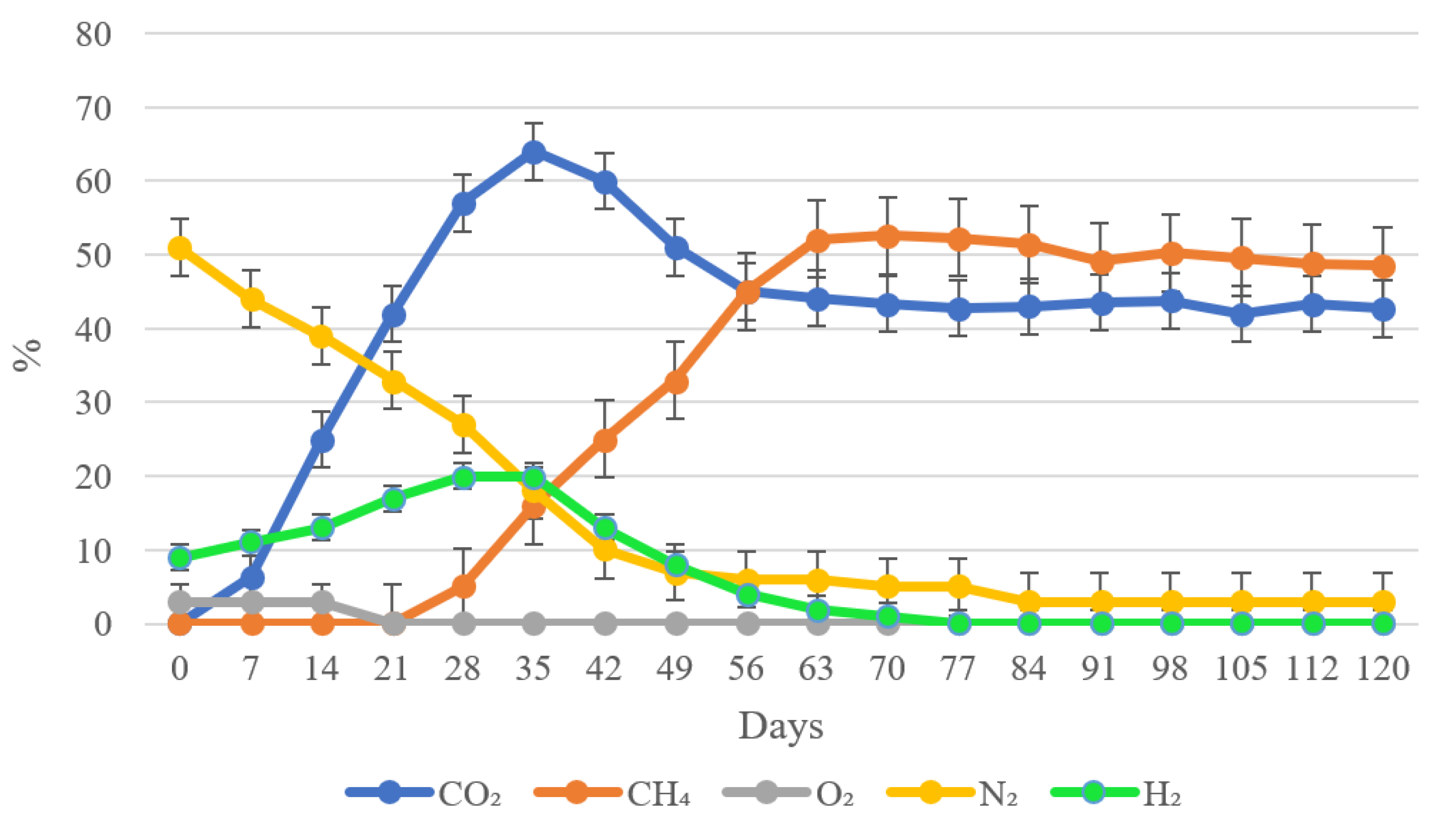

3.1. The First Landfill Model

When the MSW was placed in the first landfill model, it began to decompose under anaerobic conditions, resulting in the formation of landfill gas. Like all gases, these gases are formed due to physical, chemical, and microbial processes occurring in MSW. It was found that in the acetogenesis phase of landfill gas production, due to the activity of anaerobic bacteria, CO2 (from 25 to 64%) and H2 (from 13 to 20%) increased rapidly on the 14–35th day of the experiment. Meanwhile, O2 (from 3 to 0%) and N2 (from 39 to 18%) decreased significantly, respectively. Later, on days 35–56 of the experiment, the methanogenesis phase began without oxygen in the medium, in which methane-producing methanogenic bacteria started to dominate. In the first landfill model studied, methane emissions increased on day 35 of the experiment. On that basis, at this stage, due to the activity of mesophilic bacteria in the decomposition of MSW, CH4 production increased from 0 to 53%. However, the formation of all other landfill gases began to decline, respectively, CO2 – from 64 to 45%, H2 – from 18 to 6%, and N2 – from 20 to 4%. This could have been influenced by the microorganisms living here because methanogens are susceptible microorganisms that can consume acetates, hydrogen, and CO2 to produce methane. At the end of the methanogenesis process, on the 56th day of the experiment, equal emissions of greenhouse gases (CH4 and CO2) were recorded, that is 45%.

In the anaerobic process, less energy is produced because glucose is not entirely broken down without oxygen. During the anaerobic process, less energy is produced because glucose is not completely broken down in the absence of oxygen. Over the course of the methanogenesis stage (from day 56 to day 120 of the study), the emissions of landfill gases (CH4 and CO2) remained relatively stable. Specifically, CH4 emissions fluctuated between 45% and 53%, while CO2 emissions ranged from 42% to 45%. At the same time, the concentrations of other pollutants decrease. For example, N2 emissions decreased from 6% to 3%, and H2 emissions decreased from 4% to 1%.

Figure 2.

Gas emissions from the first landfill model.

Figure 2.

Gas emissions from the first landfill model.

An increase in pH from 6.6 to 7.2 is observed at the end of the methanogenesis process. In this process, the amount of organic compounds decreased. This was shown by chemical oxygen demand (COD) and biological oxygen demand (BOD

5) studies. Accordingly, COD (from 5.00 to 3.00 mg/L) and BOD

5 (from 3.00 to 1.00 mg/L) decreased. These studies were confirmed by the results of other researchers [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. This phase of the anaerobic process can be used as a source of renewable energy, as biogas, which consists of methane, carbon dioxide, and other traces of "polluting" gases, is produced. In addition, compared to traditional landfills, the leachate pollution decreased as organic matter decreased. However, it should be remembered and appreciated that sometimes anaerobic processes involve more chemical steps and take place much more slowly than aerobic ones. During our research, no increased concentration of ammonia was recorded in the filtrate, as was found by other researchers [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. An increase in ammonia concentration can cause partial or complete suppression of methane production and unpleasant odors, which does not fully meet the requirements of a sustainable and non-polluting landfill.

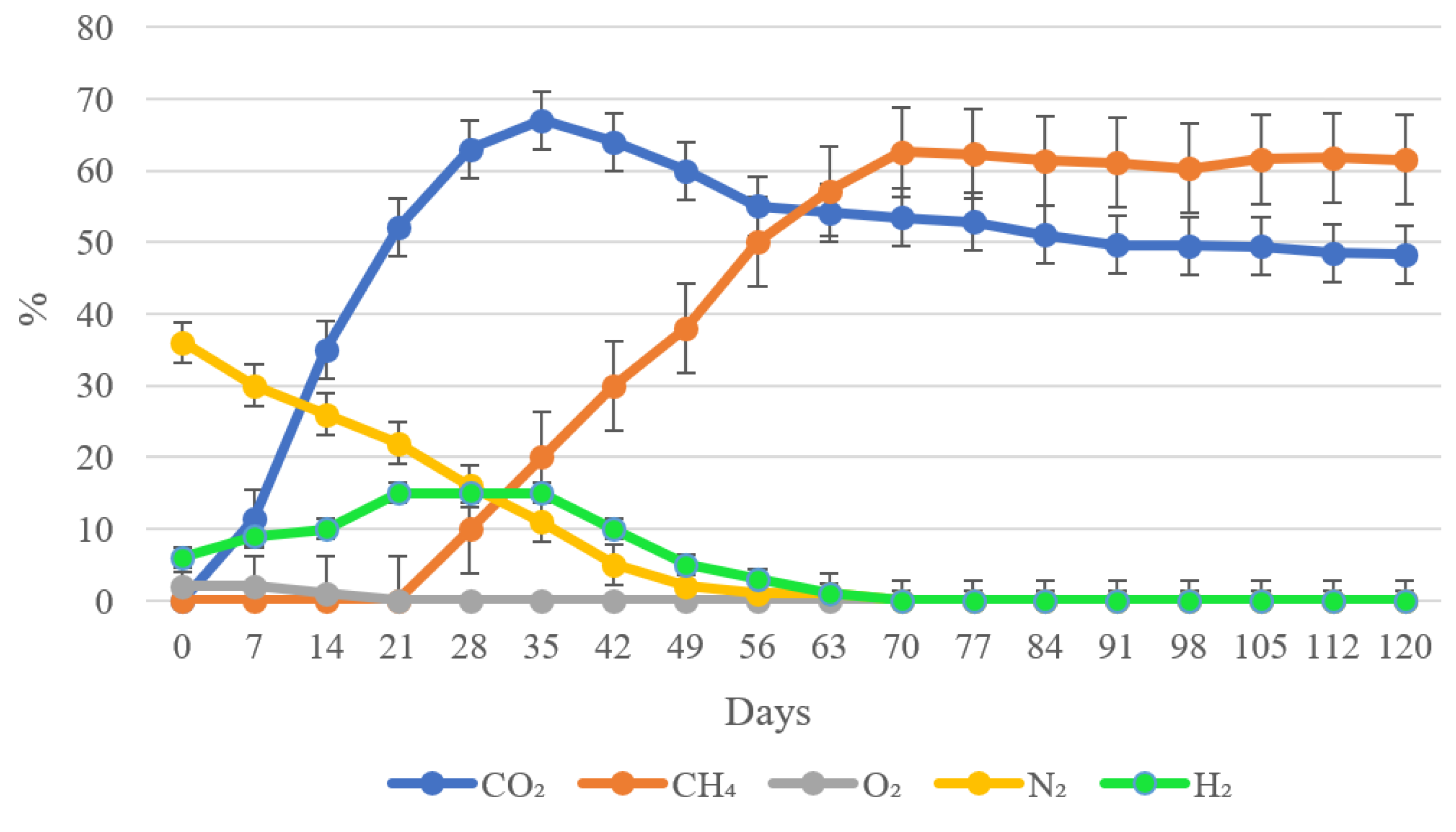

3.2. The Second Landfill Model

The second anaerobic landfill had different parameters compared to the first one. Probiotics were injected and doubled the amount of injected leachate, which resulted in a 63% increase in methane emissions over the 70 days of the experiment (

Figure 3). By the end of the experiment, methane emissions had reached as high as 60–63%. It can be argued that the injection of probiotics resulted in a more even distribution of methane emissions.

The experiment showed shallow oxygen content (1–2%) during the first 14 days. Afterward, the concentration of this pollutant decreased to zero for the rest of the experiment. As a result, the environment in the landfill model became anaerobic, completely stopping the activity of aerobic microorganisms [

21,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. During the initial 35 days of the experiment, the population of anaerobic microorganisms led to a rapid increase in carbon dioxide levels, with emissions ranging from 11% to 67%. Subsequently, like in the first landfill model, the activity of active methanogenic bacteria resulted in a decline in CO2 emissions to a range of 48% to 67%. Similar to other researchers [

19,

20,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29], the study showed a similar trend with other pollutants.

For instance, N2 emissions decreased from 36% at the beginning of the experiment to 1% by the 63rd day. In the acetogenesis phase (between the 1st and 35th day of the experiment), the activity of anaerobic bacteria caused a rapid increase in H2 concentrations from 6% to 15%. However, later, these concentrations rapidly decreased to a minimum during the methanogenesis stage. Pollutant emissions in the first and second landfill models were similar, but there were differences between them. As previously mentioned, due to changed conditions (additionally injecting probiotics, doubling the amount of filtrate), in the second landfill model, biogas (CO2 and CH4) emissions averaged 10–15%, and the duration of the acetogenesis and methanogenesis phases increased to 7–10 days. In the second landfill model, N2, H2, and O2 emissions decreased by 15-20% compared to the first landfill model. The pH increased from 5.6 to 6.2, and the studies on COD and BOD5 showed similar changes. With the decrease in organic compounds, COD decreased from 3.00 to 2.00 mg/L, and BOD5 decreased from 2.00 to 0.50 mg/L.

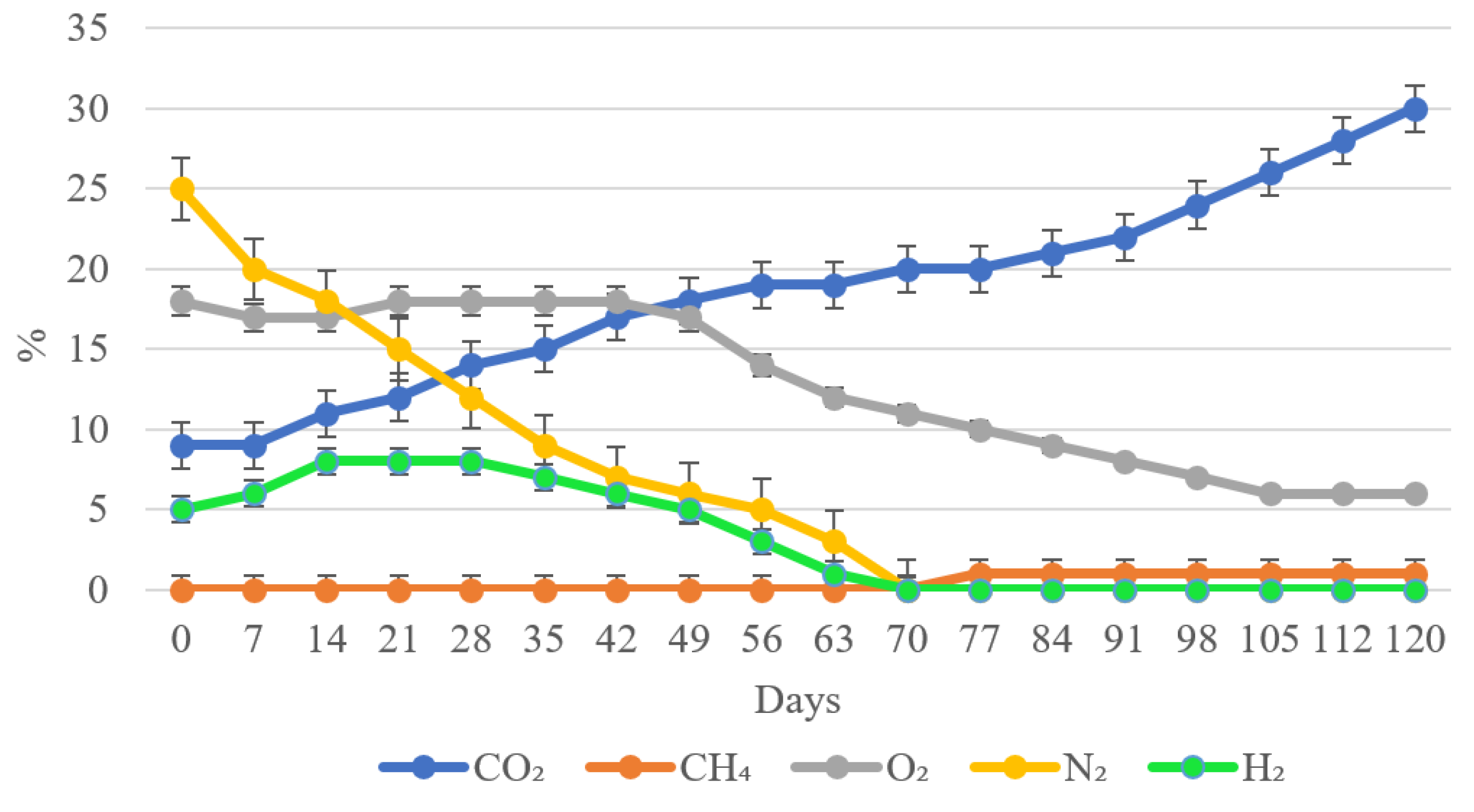

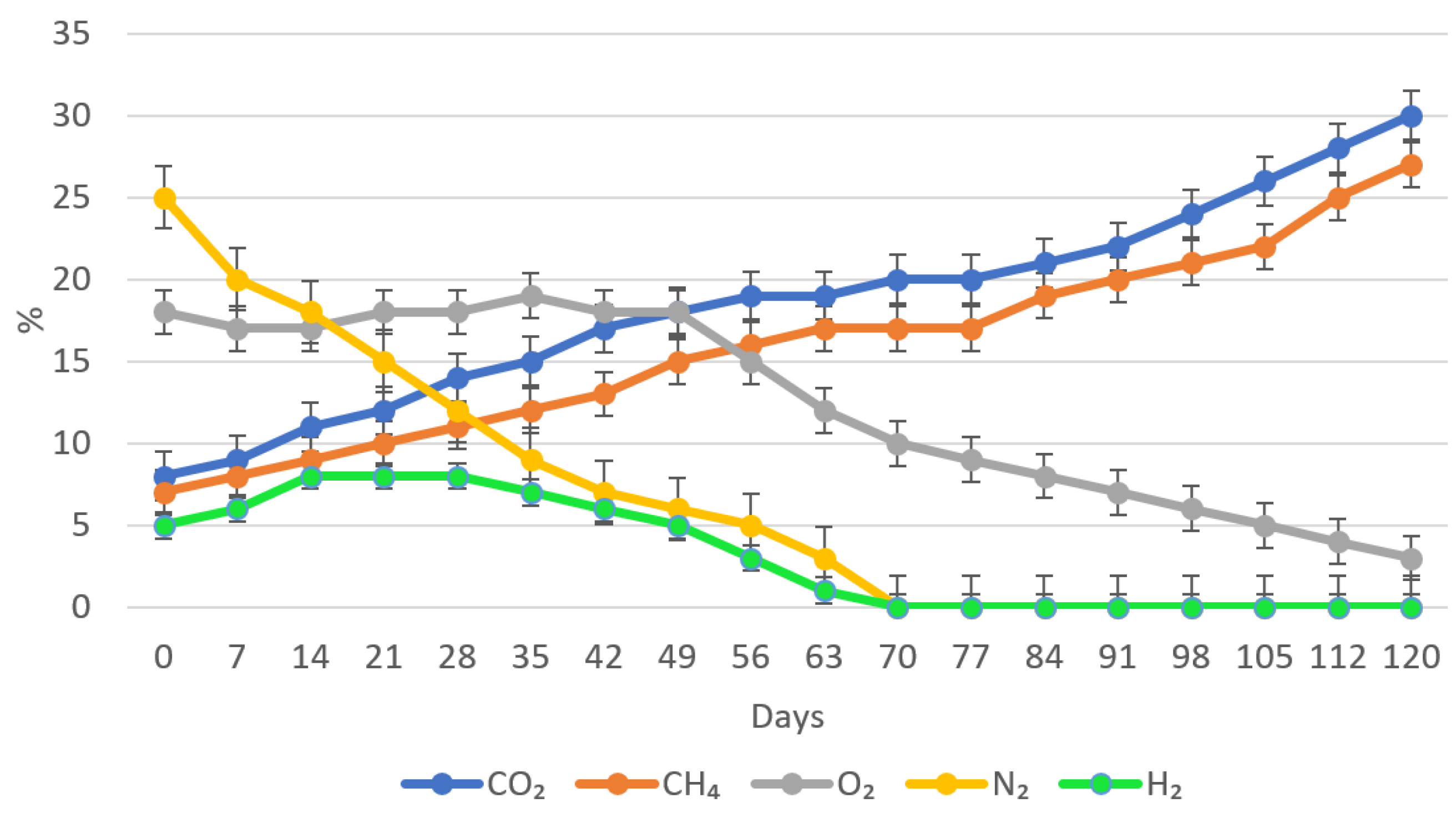

3.3. The Third Landfill Model

When the MSW waste was placed in the third landfill model, it was decomposed under aerobic conditions. These conditions were ensured with continuous air injections and constant recirculation of the filtrate. Nitrogen and hydrogen removal was significantly faster under aerobic conditions than in the first and second landfill models. For example, during the first 70 days of the study, N

2 emissions decreased from 25% to 0% (

Figure 4). Aerobic conditions throughout the waste mass quickly reduced methane levels to a minimum. These studies found that methane formation was stopped during these studies, but CO

2 was mainly formed (from 9 to 30%) during the entire study period. For example, the exhaust gas composition was the following: 6

–18% O

2, 9

–30% CO

2, 3

–25% N

2, and 1

–5% H

2. Compared to the first landfill models examined, CO2 was reduced by 10%. Aeration processes significantly reduced COD (from 2.50 to 1.50 mg/L) and BOD

5 (from 1.50 to 0.50 mg/L) of the filtrate. During this process, the pH prevailed between 6 and 8.

Although aeration processes prevented the generation of methane and energy production from MSW waste, the advantages of this landfill model can also be observed. Such a model of biodegradation processes can be used to reduce gas emissions from already closed landfills. In this way, the filtrate volume is doubled, the emissions of carbon and nitrogen compounds are faster, and the formation of unwanted odors, usually during aerobic processes, is reduced. This aeration application can be applied to old landfills where waste stabilization and aeration are required to reduce pollutant emissions more quickly.

3.4. The Fourth Landfill Model

When applying an aerobic-anaerobic system, organic matter stabilization occurred significantly faster than during a purely aerobic system. Low air inflow, single water inflow, and leachate recirculation provided these conditions for the fourth landfill model. Analogously to the model of the third landfill, during the first 70 days of the study, N

2 and H

2 emissions decreased to 0%, respectively, with the first pollutant – from 25% and the second – from 5% (

Figure 5).

Aeration processes significantly reduced COD (from 2.00 to 1.00 mg/L) and BOD

5 (from 1.00 to 0.30 mg/L) of the filtrate because the oxidation of pollutants in aerobic conditions was significantly more intense. During the aerobic-anaerobic system, biogas production was improved due to the dominance of CO

2 (from 0 to 30%) and CH

4 (from 7 to 27%). During this process, the pH fluctuated around 7. Using the aerobic-anaerobic system model, it is possible to produce energy from MSW waste, as relatively large amounts of CO

2 and CH

4 were formed. Such a model could also reduce emissions of unwanted gases from already closed landfills. In this way, with aerobic processes starting at the beginning experiment, the biodegradation processes could be accelerated to reduce pollutant emissions and the formation of unwanted odors. After analyzing the results of the third and fourth landfill models, the study's results are consistent with those obtained by other researchers [

36,

37]. This makes it possible to increase biogas production (CO

2, CH

4) faster and reduce the concentration of other chemical substances (N

2, O

2, H

2).

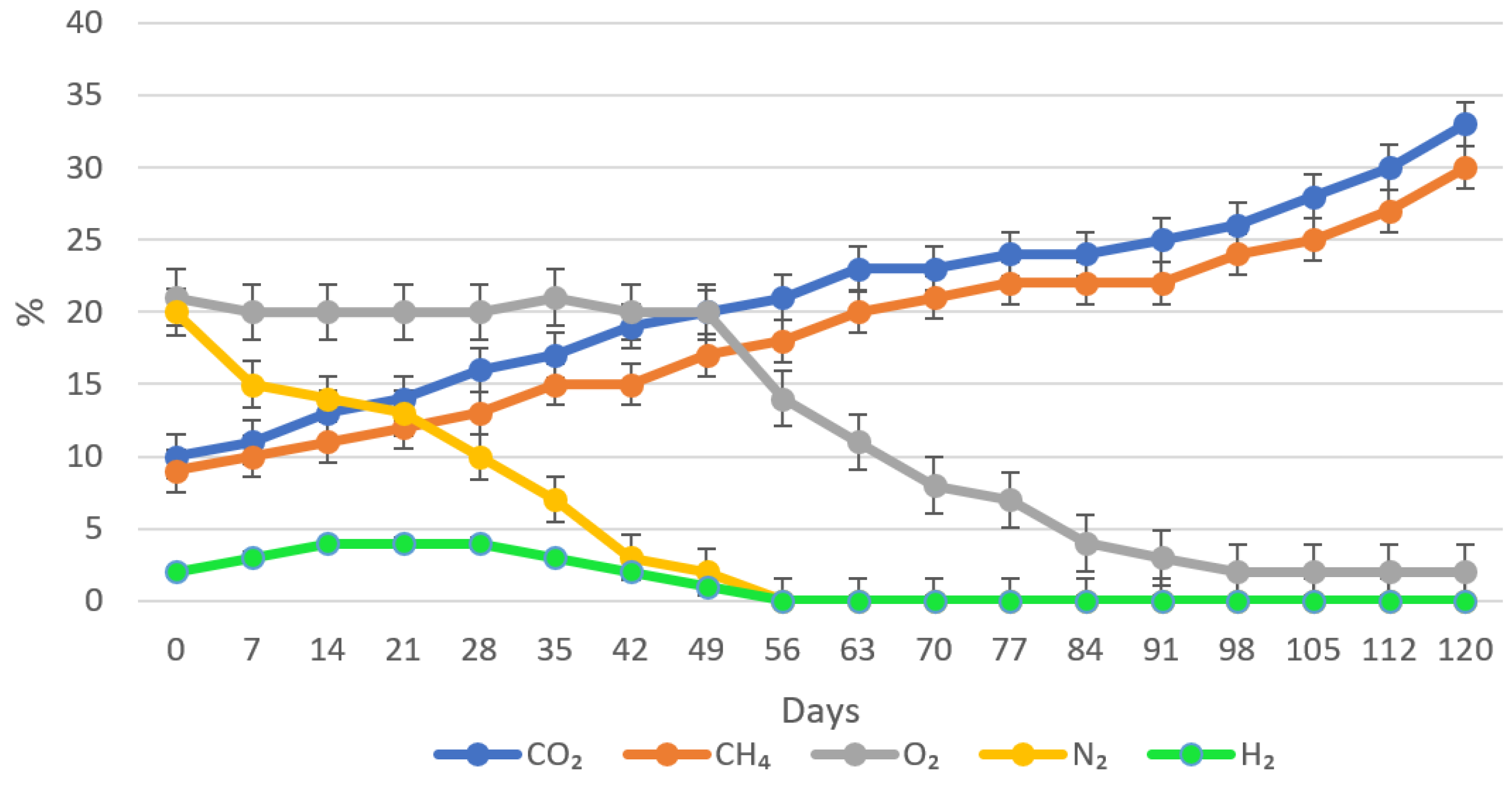

3.5. The Fifth Landfill Model

The fifth aerobic-anaerobic and flushing bioreactor landfill had parameters different from the fourth. It had low air inflow, single water inflow, leachate recirculation, and a dose of probiotics, creating unique conditions for this landfill model. During the first 56 days of testing, aerobic nitrification-denitrification processes resulted in complete nitrogen removal (from 20% to 0%), and overall waste stabilization improved the biodegradation of the charge (see

Figure 6). Biodegradation was enhanced by continuous leachate recirculation. At the same time, a decrease in H

2 from 2% to 1% was observed. After that, the activation of anaerobic processes decreased the amount of oxygen (from 14% to 2%) on days 56-120 of the study.

During this period, there was a steady increase in the production of CH

4 and CO

2 and energy recovery. Accordingly, CO

2 increased from 10% to 33%, and CH

4 from 9% to 30%. Compared to the fourth landfill model, aerobic processes took place significantly more intensively (i.e., 14 days earlier). In addition, biogas production was accelerated by up to 10% by air flow supply, filtrate recirculation, and probiotic supply. The results of these studies and other researchers [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24] confirmed that a higher amount of filtrate and a dose of probiotics can maintain a higher and more stable methane concentration. Using probiotics in a fifth landfill model reduced odor and organic matter levels. During this stage, mesophilic bacteria and micromycetes oxidized the fermentation products of previous phases, such as other harmful gases (hydrogen sulfide, sulfur mercaptan, light aromatic compounds). From an economic perspective, such technology is expensive, so it is only applied when traditional biodegradation processes cannot reduce pollutant emissions. During this aerobic-anaerobic period, the aim was to maximize methane production by accelerating the acetogenesis phase and maintaining an optimal pH (7).

4. Conclusions

The results of the research showed that the first and second models of landfills, using only anaerobic conditions, can be used for the treatment of MSW for the production of biogas (CH4, CO2), as up to 40–60% of it was released during the 120-experiment period. It can be noted that in the second landfill model, with the additional use of probiotics, biogas was released on average 10–15% more than in the first landfill model without probiotics.

The third landfill model, maintaining only aerobic conditions, showed the lowest quantitative emissions of greenhouse gases (for example, CH4 only 1% during the 120-experiment period). This aeration program can be applied in old, already closed landfills, where rapid stabilization and aeration of MSW is required to minimize pollutant emissions (N2, etc.) and unwanted odors and shorten biodegradation processes.

The results of the fourth and fifth landfill models, in which aerobic-anaerobic conditions were applied, showed that the developing nitrification-denitrification processes resulted in complete nitrogen removal (from 20% to 0%), and overall waste stabilization improved the biodegradation of the MSW. Later, relatively good (on average 30%) results of biogas (CH4, CO2) emissions are achieved during anaerobic conditions formation results. It can be noted that in the fifth landfill model, with the additional use of probiotics, biogas was released on average 10–15% more, and the processes took place on average 14 days more intensively than in the fourth landfill model without probiotics.

Summarizing all experiment results of all landfill models for further evaluation of the processes, all models can be applied in real practice depending on where they will be applied and what result they want to achieve. That is, if it is necessary to produce more biogas, then it is recommended to use the first and second anaerobic landfill models; if you want to fix old landfills as soon as possible, then the third aerobic model should be applied, and if you want to fix MSW and get more biogas, then only the fourth and fifth aerobic-anaerobic models of landfills are best.

These experimental studies showed that probiotics were effective in the second and fifth landfill models. Therefore, in the future, it would be interesting further to investigate the effectiveness of the use of probiotics and find out the related questions: how quickly the amount of organic matter changes in landfill models, how the number of microorganisms changes, how quickly the efficiency of pollutant cleaning or biogas generation is achieved, etc.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.V. and A.Z.; methodology, R.V.; software, R.V.; validation, A.Z.; formal analysis, R.V.; investigation, R.V.; resources, R.V.; data curation, R.V. and A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, R.V. and A.Z.; writing—review and editing, A.Z.; visualization, R.V.; supervision, A.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gautam, M.; Agrawal, M. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Municipal Solid Waste Management: A Review of Global Scenario. Carbon Footprint Case Studies: municipal solid waste management, sustainable road transport, and carbon sequestration, 2021; 123–160. [Google Scholar]

- Clougherty, J.E.; Ocampo, P. Perception Matters: Perceived vs. Objective Air Quality Measures and Asthma Diagnosis among Urban Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 6648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trozzi, C.; Kuenen, J.; Hjelgaard, K. Biological treatment of waste – solid waste disposal on land. EMEP/EEA emission inventory guidebook. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union 2019.

- Study on investment needs in the waste sector and on financing municipal waste management in Member States, 2019.

- Council Directive 2018/850/EC of 30 May 2018 on the landfill of waste 2018.

- Lithuania’s eighth national communication and fifth biennial report under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change 2022.

- Parameswari, K.; Al Aamri, A.M.S.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Arunachalam, S.; Alawi, A.A.S.; Al Sivasakthivel, T. Sustainable landfill design for effective municipal solid waste management for resource and energy recovery. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 47, 2441–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, S.A.; Al-Mamun, A.; Said Baawain, M.; Sana, A. A critical review of the recently developed laboratory-scale municipal solid waste landfill leachate treatment technologies. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2022, 52, 102011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrad, M.; Huber-Humer, M. Performance and completion assessment of an in-situ aerated municipal solid waste landfill – Final scientific documentation of an Austrian case study. Waste Management 2017, 63, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, S.; Khan, R. Sustainable waste management approach: A paradigm shift towards zero waste into landfills. Advanced Organic Waste Management 2022, 381–395. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqua, A.; Hahladakis, J.N.; Al-Attiya, W.A.K.A. An overview of the environmental pollution and health effects of waste landfilling and open dumping. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 58514–58536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navid Ahmad, N.; Mosthaf, K.; Scheutz, C.; Kjeldsen, P.; Rolle, M. Model-based interpretation of methane oxidation and respiration processes in landfill covers: 3-D simulation of laboratory and pilot experiments. Waste Management 2020, 108, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijekoon, P.; Koliyabandara, P.A.; Cooray, A.T.; Lam, S.S.; Athapattu, B.C.L.; Vithanage, M. Progress and prospects in mitigation of landfill leachate pollution: Risk, pollution potential, treatment and challenges. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 421, 126627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.S.; Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Abu-Dieyeh, M.H. Sustainable and long-term management of municipal solid waste: A review. Bioresource Technology Reports 2022, 18, 101067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Zhang, J.; Raga, R.; et al. Effectiveness of aerobic pretreatment of municipal solid waste for accelerating biogas generation during simulated landfilling. Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering 2018, 12, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Morello, L.; Raga, R.; Lavagnolo, M.C.; et al. The S.An.A.® concept: Semi-aerobic, Anaerobic, Aerated bioreactor landfill. Waste Management 2017, 67, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, D.; Chen, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhan, L. An Aerobic Degradation Model for Landfilled Municipal Solid Waste. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 7557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syafrudin, S.; Hadiwidodo, M.; Sutrisno, E. Feasibility Study for Mining Waste Materials as Sustainable Compost Raw Material Toward Enhanced Landfill Mining. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies 2023, 32, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Cobo, J.J.; Casallas-Ojeda, M.R.; Carabalí-Orejuela, L.; et al. Methane potential and degradation kinetics of fresh and excavated municipal solid waste from a tropical landfill in Colombia. Sustainable Environment Research 2020, 30, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosevic, L.T.; Mihajlovic, E.R.; Djordjevic, A.V.; Protic, M.Z.; Ristic, D.P. Identification of Fire Hazards Due to Landfill Gas Generation and Emission. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies 2018, 27, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Lei, L.; Xue, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fei, X. A systematic assessment of aeration rate effect on aerobic degradation of municipal solid waste based on leachate chemical oxygen demand removal. Chemosphere 2020, 263, 128–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olugbenga, O.S.; Adeleye, P.G.; Oladipupo, S.B.; Adeleye, A.T.; John, K.I. Biomass-derived biochar in wastewater treatment- a circular economy approach. Waste Management Bulletin 2023, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, M.; Shimaoka, T.; Komiya, T. Influence of operations on leachate characteristics in the Aerobic-Anaerobic Landfill Method. Waste Management 2018, 78, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarassy, C.; Hoang, N.H.; Nagy-Pércsi, K. Composting Strategy Instead ofWaste-to-Energy in the Urban Context—A Case Study from Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Cobo, J.J.; Caicedo-Concha, D.M.; Marmolejo-Rebellón, L.F.; Torres-Lozada, P.; Fellner, J. Evaluation of Leachate Recirculation as a Stabilisation Strategy for Landfills in Developing Countries. Energies 2022, 15, 6494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, O.A. , Ibrahim, J.A. Leachates Recirculation Impact on the Stabilization of the Solid Wastes – A Review. Journal of Ecological Engineering 2023, 24, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Pan, T.; Zhao, H.; Guo, Y.; Chen, G.; Hou, L. Application of Landfill Gas-Water Joint Regulation Technology in Tianjin Landfill. Processes 2023, 11, 2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.L.; Le, T.K.O.; Wong, Y.J.; Phan, C.T.; Trinh, T.L. Towards Sustainable Composting of Source-Separated Biodegradable Municipal SolidWaste—Insights from Long An Province, Vietnam. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, H.A.; Ramli, S.F.; Hung, Y.-T. Physicochemical Technique in Municipal SolidWaste (MSW) Landfill Leachate Remediation: A Review. Water 2023, 15, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandra, T.V.; Bharath, H.A.; Kulkarni, G.; Han, S.S. Municipal Solid Waste: Generation, Composition and GHG Emissions in Bangalore, India. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 82, 1122–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Mansour, M.S.M. Solid Waste Issue: Sources, Composition, Disposal, Recycling, and Valorization. Egyptian Journal of Petroleum 2018, 27, 1275–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheybari, S.; Rezaie, F.M.; Naji, S.A.; Najafi, F. Evaluation of Energy Production Technologies from Biomass Using Analytical Hierarchy Process: The Case of Iran. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 232, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, F.; Wen, Z.; Huang, S.; De Clercq, D. Mechanical Biological Treatment of Municipal Solid Waste: Energy Efficiency, Environmental Impact and Economic Feasibility Analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 178, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, P.; Varjani, S.; Singhania, R.R.; Patel, A.K.; Awasthi, M.K.; Sindhu, R.; Zhang, Z.; Binod, P.; Awasthi, S.K.; Chaturvedi, P. Critical Review on Technological Advancements for Effective Waste Management of Municipal Solid Waste — Updates and Way Forward. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2021, 23, 101749. [Google Scholar]

- Di Nola, M.F.; Escapa, M.; Ansah, J.P. Modelling Solid Waste Management Solutions: The Case of Campania, Italy. Waste Management 2018, 78, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Lei, L.; Xue, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fei, X. A systematic assessment of aeration rate effect on aerobic degradation of municipal solid waste based on leachate chemical oxygen demand removal. Chemosphere 2020, 263, 128218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Shimaoka, T.; Nakayama, H.; Komiya, T.; Chai, X. Stimulation of waste decomposition in an old landfill by air injection. Bioresource Technology 2016, 222, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Chen, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhan, L.; Ling, D.; Ke, H.; Hu, J.; Li, J. A thermo-hydro-mechanical-biochemical coupled model for landfilled municipal solid waste. Computers and Geotechnics 2021, 134, 104090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Turnhout, A.G.; Brandstätter, C.; Kleerebezem, R.; Fellner, J.; Heimovaara, T.J. Theoretical analysis of municipal solid waste treatment by leachate recirculation under anaerobic and aerobic conditions. Waste Management 2018, 71, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.K.; Chen, Y.M.; Xu, W.J.; Zhan, L.T.; Ke, H.; Li, K. Biochemical-thermal-hydro-mechanical coupling model for aerobic degradation of landfilled municipal solid waste. Waste Management 2022, 144, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LAND 21-01. Environmental Rules of household water filtration equipment’s for installation in natural conditions (in Lithuanian: Aplinkosauginės buitinių nuotekų filtravimo įrenginių įrengimo gamtinėmis sąlygomis taisyklės). State News (in lithuanian language: Valstybės žinios). 2001–05–16; 41–1438:8, 2001 [In Lithuanian].

- Regulation on Wastewater Management (in Lithuanian language: Nuotekų tvarkymo reglamentas). D1-236. Vilnius, 2006 [In Lithuanian].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and the editor(s). MDPI and the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).