Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

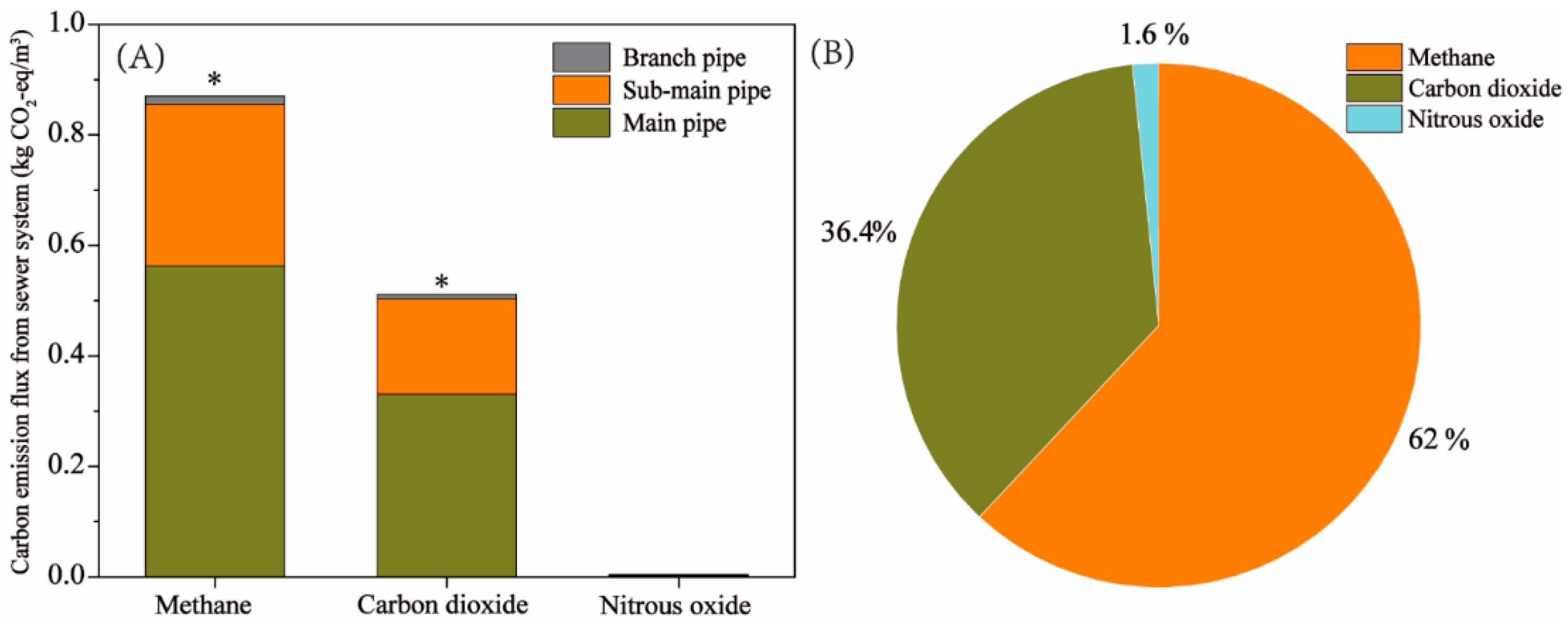

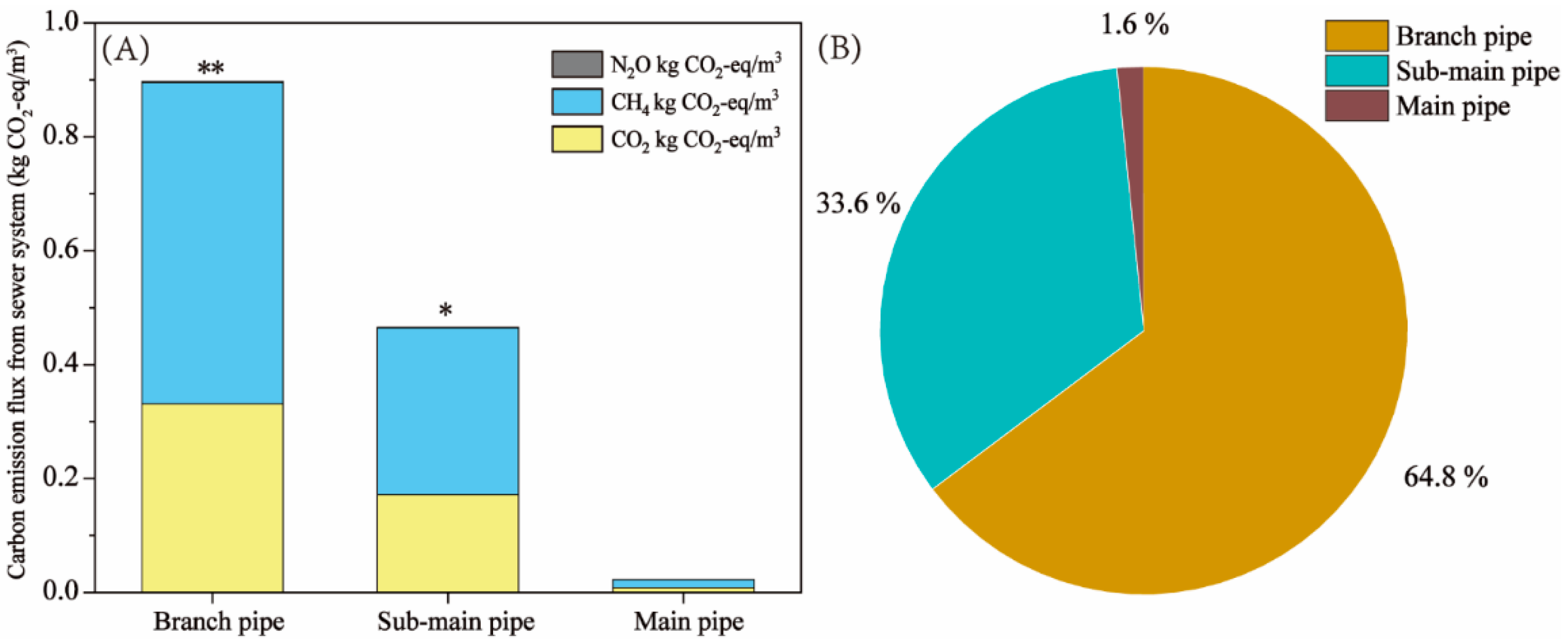

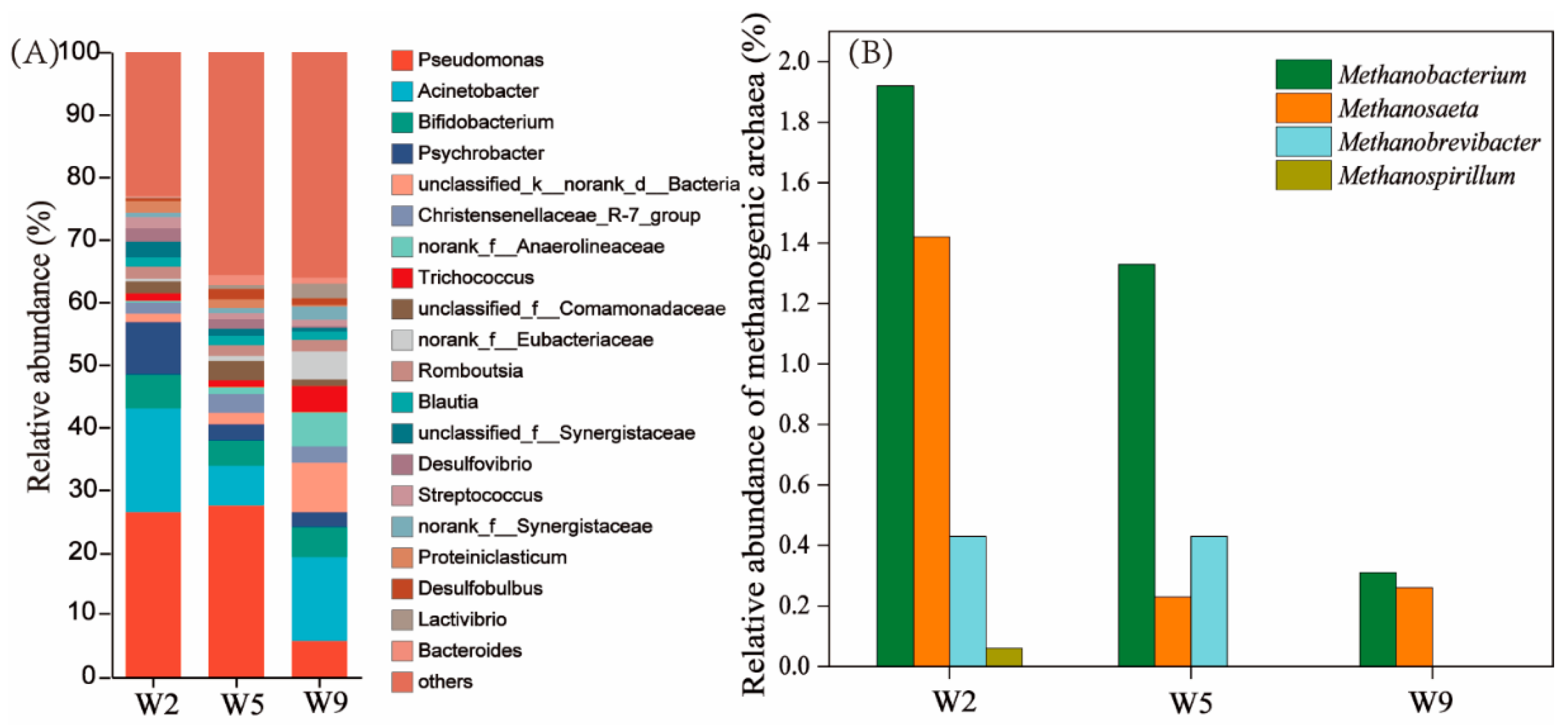

The carbon emission fluxes in the urban sewer systems and the microbial community structure in sewer sediments remain unclear. In this study, a sewer system located in southern China was utilized to investigate the water quality characteristics, carbon emission flux, and microbial community structure in sediment. The results showed that the chemical oxygen demand loss rates in the branch pipe and sub-main pipe were 27.1% and 14.1 %, respectively. The estimated carbon emission flux revealed a total carbon emission flux from the sewer system was 1.39 kg CO2-eq/m3 and the emissions fluxes of methane and carbon dioxide were 0.87 kg CO2-eq/m3 and 0.51 kg CO2-eq/m3, accounted for 62% and 36.4%. Microbial community structure analysis revealed that methanogenic archaea in the sediments of the branch pipes and sub-main pipes were Methanobacterium, Methanosaeta, and Methanobrevibacter. The methanogenic activity of sewer sediments was further assessed. This study further confirmed that the branch pipe and sub-main pipe were the main sources of carbon emission and methane and carbon dioxide are the main greenhouse gases in the sewer system. This study furnishes novel insights for the control of carbon emissions in municipal sewage systems.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

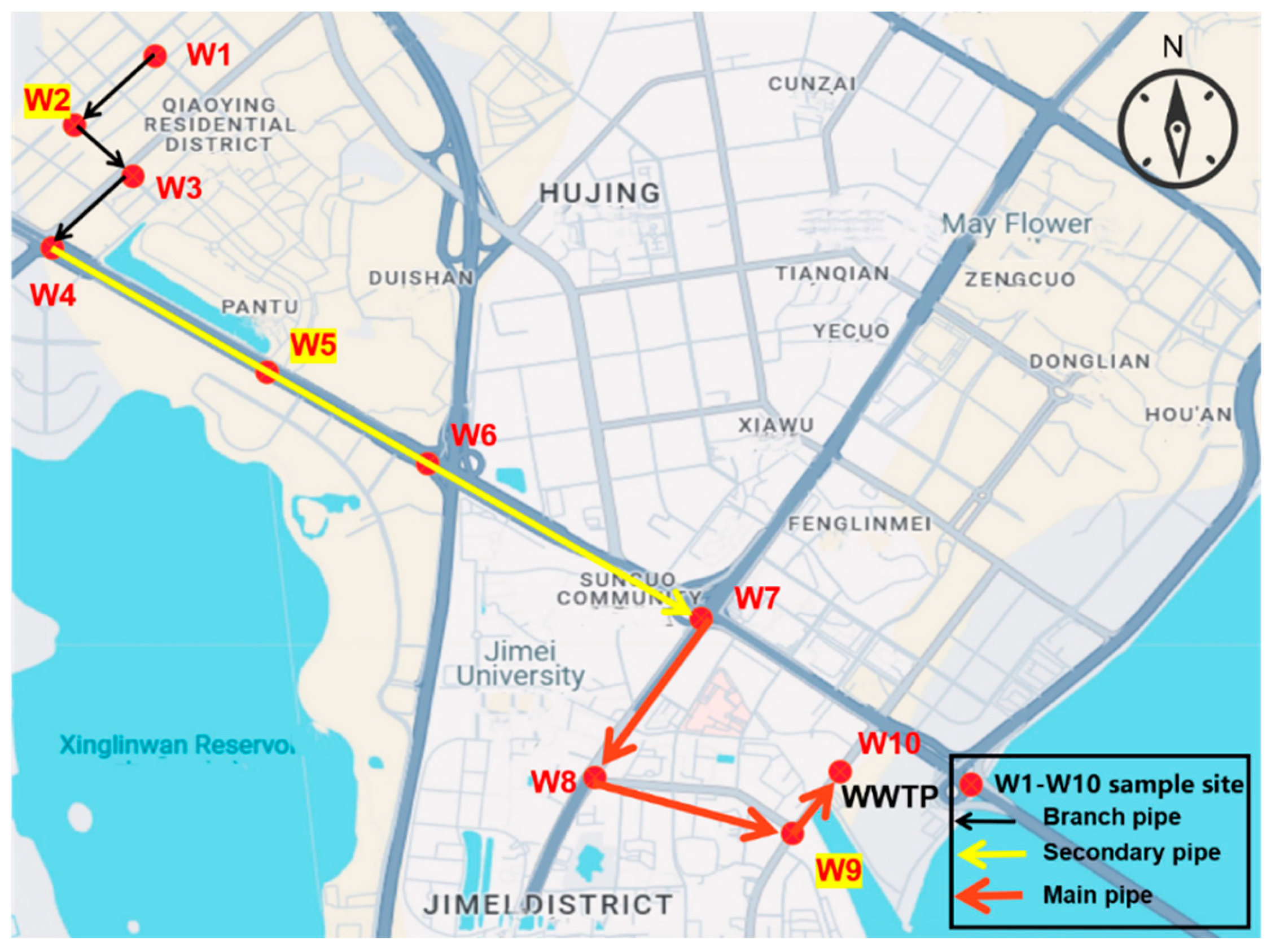

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling Collection

2.3. GHG Emission Flux Measurements and Calculations

2.3.1. Methods for Calculating CO2 Flux

2.3.2. Methods for Calculating CH4 Flux

2.3.3. Methods for Calculating N2O Flux

2.4. Assessment of Methane Production Rate in Sewer Sediments

2.5. DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Sequencing

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Septage Composition Characteristics in the Sewer System

3.2. Analysis of GHG Emission Flux in the Sewer System

3.2.1. Emission Fluxes of CH4, CO2 and N2O in the Sewer System

3.2.2. Location Analysis of GHG Emissions in the Sewer System

3.3. Assessment of Methane Production Rate in Sewer Sediments

3.4. Microbial Community Structure Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, Y.; Shi, X.; Jin, X.; Wang, X.C.; Jin, P. A critical review of wastewater quality variation and in-sewer processes during conveyance in sewer systems. Water Res. 2023, 228, 119398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khabiri, B.; Ferdowsi, M.; Buelna, G.; Jones, J.P.; Heitz, M. Bioelimination of low methane concentrations emitted from wastewater treatment plants: a review. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2022, 42(3), 450–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, G.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, D.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T. Simultaneous use of nitrate and calcium peroxide to control sulfide and greenhouse gas emission in sewers. Sci. Total Environ. 2023a, 855, 158913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Liu, W.; Xu, D.; Hou, Y.; Ren, B.; Jin, X.; Jin, P. Metagenomics analysis of ecosystem integrating methane and sulfide generation in urban sewer systems. J.Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 135372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholkar, P.; Shastri, Y.; Tanksale, A. Renewable hydrogen and methane production from microalgae: A techno-economic and life cycle assessment study. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D. R., Barnes, R. T., & Raymond, P. A. (2009). Inputs of fossil carbon from wastewater treatment plants to US rivers and oceans. Environmental Science & Technology, 43(15), 5647-5651.

- Rodriguez-Garcia, G., Hospido, A., Bagley, D. M., Moreira, M. T., & Feijoo, G. (2012). A methodology to estimate greenhouse gases emissions in life cycle inventories of wastewater treatment plants. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 37, 37-46.

- Liao, Z.; Chu, J.; Zhou, S.; Chen, H. Evaluation of the pollutant interactions between different overlying water and sediment in simulated urban sewer system by excitation-emission matrix fluorescence spectroscopy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2022, 29(30), 46188–46199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Wang, H.C.; Yin, W.X.; Wang, Y.Q.; Lv, J.Q.; Wang, A.J. Deciphering carbon emissions in urban sewer networks: Bridging urban sewer networks with city-wide environmental dynamics. Water Res. 2024, 121576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W. J.; Lu, J.Y.; Hu, Y.-R.; Xiao, J.; Yang, C.; Wu, J.; Huang, B.; Cui, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.W. Spatiotemporal pattern of greenhouse gas emissions in China’s wastewater sector and pathways towards carbon neutrality. Nat. Water 2023, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H., Wang, Q., Liu, J., Zheng, X., Xu, M. Closing the gap in methane emission from urban wastewater sewer system in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 437, 140722.

- Foley, J., Yuan, Z., Lant, P. Dissolved methane in rising main sewer systems: field measurements and simple model development for estimating greenhouse gas emissions. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 60(11), 2963-2971.

- Beelen, B., Parker, W. A probabilistic approach to the quantification of methane generation in sewer networks. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 320, 115775. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. , Liu, K., Wang, K., Chen, X., Wu, K. Fossil-fuel and food systems equally dominate anthropogenic methane emissions in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57(6), 2495–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlroy, S.J.; Leu, A.O.; Zhang, X.; Newell, R.; Woodcroft, B.J.; Yuan, Z.; Hu, S.; Tyson, G.W. Anaerobic methanotroph ‘Candidatus Methanoperedens nitroreducens’ has a pleomorphic life cycle. Nat. Microbiol. 2023, 8(2), 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, D.P.; Li, N.P.; Wendt, L.P.; Castaneda, S.R.; Falinski, M.M.; Zhu, J.J.; Song, C.; Ren, Z.J.; Zondlo, M.A. Underestimation of sector-wide methane emissions from United States wastewater treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57(10), 4082–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC (2007) Direct global warming potentials - AR4 WGI Chapter 2: changes in atmospheric constituents and in radiative forcing. http://www.ipcc.ch/publications _and_data/ar4/wg1/ en/ch2s2–10-2.html.

- Singh, V.; Phuleria, H. C.; Chandel, M.K. Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from municipal wastewater treatment systems in India. Water. Environ. J. 2017, 31(4), 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidelines for carbon accounting and emission reduction in the urban water sector. 2022.

- Cen, X.; Li, J.; Jiang, G.; Zheng, M. A critical review of chemical uses in urban sewer systems. Water Res. 2023, 120108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Liu, J.; Lu, J. Upstream Natural Pulsed Ventilation: A simple measure to control the sulfide and methane production in gravity sewer. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 742, 140579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Shi, X.; Chi, Y.; Ren, T.X. , Wang, X.C.; Jin, P.A comprehensive assessment of fungi in urban sewer biofilms: community structure, environmental factors, and symbiosis patterns. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 806, 150728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P.; Gu, Y.; Shi, X.; Yang, W. Non-negligible greenhouse gases from urban sewer system. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2019, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ni, B.J.; Ganigue, R.; Werner, U.; Sharma, K.R.; Yuan, Z. Sulfide and methane production in sewer sediments. Water Res. 2015a, 70, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, K.; Liu, T.; Bai, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zheng, M. Achieving stable partial nitritation in an acidic nitrifying bioreactor. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54(1), 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. 2017. USA, Washington, D.C.

- Yin, Y.; Qi, X.; Gao, L.; Lu, X.; Yang, X.; Xiao, K.; Liang, P. Quantifying methane influx from sewer into wastewater treatment processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Li, J.; Jiang, G.; Chen, S.; Niel, C.; Yuan, Z.; Mueller, J.F.; Thai, P. Transformation of phthalates and their metabolites in wastewater under different sewer conditions. Water Res. 2021, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, L.T.; Harada, H.; Fujii, S.; Nguyen, L.P.H.; Hoang, T.H.T.; Huynh, H.T. Greenhouse gas emissions from blackwater septic systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55(2), 1209–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Zheng, F.; Maier, H.R.; Ostfeld, A.; Creaco, E.; Savic, D.; Langeveld, J.; Kapelan, Z. Water quality modeling in sewer networks: Review and future research directions. Water Res. 2021, 202, 117419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Yin, H.; Xu, Z.; Peng, J.; Yu, Z. Pin-pointing groundwater infiltration into urban sewers using chemical tracer in conjunction with physically based optimization model. Water Res. 2020, 175, 115689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Yan, G.; Fu, L.; Cui, B.; Wang, J.; Zhou, D. A review of filamentous sludge bulking controls from conventional methods to emerging quorum quenching strategies. Water Res. 2023, 119922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulandaivelu, J.; Choi, P.M.; Shrestha, S.; Li, X.; Song, Y.; Li, J.; Jiang, G. Assessing the removal of organic micropollutants from wastewater by discharging drinking water sludge to sewers. Water Res. 2020, 181, 115945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P.; Wang, B.; Jiao, D.; Sun, G.; Wang, B.; Wang, X.C. Characterization of microflora and transformation of organic matters in urban sewer system. Water Res. 2015, 84, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ye, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jia, Q.; Nie, Y.; Benoit, G. Variations in CH4 and CO2 productions and emissions driven by pollution sources in municipal sewers: An assessment of the role of dissolved organic matter components and microbiota. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, K.; Wang, K.; Chen, X.; Wu, K. Fossil-fuel and food systems equally dominate anthropogenic methane emissions in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57(6), 2495–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somlai, C.; Knappe, J.; Gill, L. Spatial and temporal variation of CO2 and CH4 emissions from a septic tank soakaway. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 679, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P.; Gu, Y.; Shi, X.; Yang, W. Non-negligible greenhouse gases from urban sewer system. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2019, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ni, B.J.; Sharma, K.R., Yuan, Z. Methane emission from sewers. Sci. Total. Environ. 2015b, 524–525, 40–51.

- Singh, V.; Phuleria, H.C.; Chandel, M.K. Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from municipal wastewater treatment systems in India. Water. Environ. J. 2017, 31(4), 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laso-Perez, R.; Wu, F.; Cremiere, A.; Speth, D.R.; Magyar, J.S.; Zhao, K.; Krupovic, M.; Orphan, V.J. Evolutionary diversification of methanotrophic ANME-1 archaea and their expansive virome. Nat. Microbiol. 2023, 8(2), 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, E.; Sivakumar, M.; Kelso, C.; Zhang, S.; Shi, J.; Gao, J.; Gao, S.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, G. Effects of sewer biofilms on the degradability of carbapenems in wastewater using laboratory scale bioreactors. Water Res. 2023, 233, 119796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Nie, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Jia, Q.; and Ye, J. Variable sediment methane production in response to different source-associated sewer sediment types and hydrological patterns: Role of the sediment microbiome. Water Res. 2021, 190, 116670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Xing, Y.; Duan, H.; Ren, D.; Zheng, M.; Liu, Y.; Huang, X. Reducing sulfide and methane production in gravity sewer sediments through urine separation, collection and intermittent dosing. Water Res. 2023, 234, 119820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Liu, T.; Zheng, M.; Xing, Y.; Ren, D.; Li, H.; Huang, X. Recovery of ammonium nitrate solution from urine wastewater via novel free nitrous acid (FNA)-mediated two-stage processes. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 440, 135826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, K.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Pang, H.; Yang, J.; Lu, J. Trace antibiotics increase the risk of antibiotic resistance genes transmission by regulating the biofilm extracellular polymeric substances and microbial community in the sewer. J. Hazard.Mater. 2022, 432, 128634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamri, M.F.M.A.; Hasmady, S.; Akhiar, A.; Ideris, F.; Shamsuddin, A.H.; Mofijur, M.; Mahlia, T.M.I. A comprehensive review on anaerobic digestion of organic fraction of municipal solid waste. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2021, 137, 110637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, X.; Li, J.; Jiang, G.; Zheng, M. A critical review of chemical uses in urban sewer systems. Water Res. 2023, 120108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Li, W.; Ma, Y.; Liu, J. Time-based succession existed in rural sewer biofilms: bacterial communities, sulfate-reducing bacteria and methanogenic archaea, and sulfide and methane generation. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 765, 144397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagnoli, A., Ahmed, M. S., Desideri, U., Pecorini, I. Environmental assessment of gasification and green hydrogen potential role in waste management decarbonization. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 144174.

- Roldán, M., Bouzas, A., Seco, A., Mena, E., Mayor, Á., & Barat, R. An integral approach to sludge handling in a WWTP operated for EBPR aiming phosphorus recovery: simulation of alternatives, LCA and LCC analyses. Water Res. 2020, 175, 115647.

| Sample site |

T (℃) | pH | DO ( mg/L) | ORP (mV) | (m/S) | COD (mg/L) | TN (mg/L) | NH4+-N (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | 22.4 | 8.3 | 4.39 | -154.6 | 0-0.11 | 437.3 | 67.8 | 52.6 |

| W2 | 21.5 | 7.7 | 1.55 | -252.3 | 0.12-0.3 | 355.7 | 66.4 | 53.6 |

| W3 | 21.6 | 7.7 | 1.64 | -296.6 | 0.11-0.31 | 305.1 | 67.2 | 60.9 |

| W4 | 21.5 | 7.5 | 2.12 | -256.8 | 0.19-0.32 | 318.7 | 65.7 | 63.4 |

| W5 | 21.4 | 7.8 | 2.45 | -232.4 | 0.21-0.41 | 265.4 | 65.8 | 64.8 |

| W6 | 21.7 | 7.7 | 2.69 | -218.6 | 0.2-0.42 | 274.1 | 66.3 | 56.9 |

| W7 | 21.5 | 7.6 | 2.38 | -237.0 | 0.41-0.72 | 257.1 | 64.8 | 63.6 |

| W8 | 21.5 | 7.7 | 3.01 | -214.2 | 0.57-1.02 | 266.7 | 66.2 | 64.8 |

| W9 | 21.4 | 7.7 | 3.16 | -201.6 | 0.61-1.05 | 262.5 | 65.7 | 65.9 |

| W10 | 21.5 | 7.6 | 5.01 | -157.2 | 0.61-1.02 | 254.1 | 64.9 | 61.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).