Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

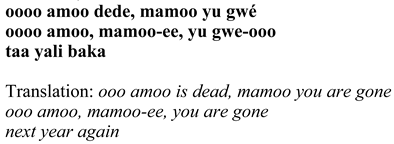

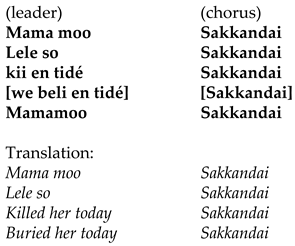

Interpretation of the Songs

African Agency in Rice Cultivation

Conclusions

Funding

Disclosure Statement

Acknowledgements

References

- Konrad S. Bayer, ‘Slave songs: Codes of resistance’, Kinki University English Journal 6 (2010):109-24; Miles M. Fisher, Negro slave songs in the United States (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1953); Erik Nielson, ‘Go in De Wilderness: Evading the “eyes of others” in the slave songs’. Western Journal of Black Studies 2011, 35, 106–117.

- John, W. In Work; Folk song of the American Negro. Fisk University Press: Nashville, 1915. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, W.F.; Ware, C.P. Lucy McKim Garisson. In Slave songs of the United States; A. Simpson & Co.: New York, 1867. [Google Scholar]

- Work, Folk Song; Lydia Parrish, Slave songs of the Georgia Sea Islands (New York: Creative Age Press, Inc., 1942).

- Turner, L.D. Africanisms in the Gullah dialect (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1949); Jane Collings, ‘The language you cry in: Story of a Mende song’. The Oral History Review 2001, 28, 115–118. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, C. Littlefield, Rice and slaves: Ethnicity and the slave trade in Colonial South Carolina (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1981); Judith A. Carney, Black Rice: The African origins of rice cultivation in the Americas (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001).

- Parrish, Slave Songs, 235; Peter H. Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1974).

- Richard Price, ‘Subsistence on the plantation periphery: Crops, cooking, and labour among eighteenth century Suriname Maroons’, Slavery & Abolition 12, no. 1 (1991):107–27; Tinde van Andel, Amber van der Velden, and Minke Reijers, ‘The ‘Botanical Gardens of the Dispossessed’ revisited: Richness and significance of Old World crops grown by Suriname Maroons’, Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 63 (2016): 695-710.

- For local names, see Nicholaas M. Pinas, Marieke van de Loosdrecht, Harro Maat, Tinde van Andel, ‘Vernacular names of traditional rice varieties reveal the unique history of Maroons in Suriname and French Guiana’, Economic Botany 77, no. 2 (2023): 117-34; for funeral and mourning rituals, see Gabriela Ising, Traditional Maroon rice dishes in Suriname and French Guiana: its documentation and role in Maroon culture (MSc diss., Wageningen University, 2022); Nicholaas M. Pinas, John Jackson, N. André Mosis, and Tinde van Andel, ‘The mystery of black rice: Food, medicinal, and spiritual uses of Oryza glaberrima by Maroon communities in Suriname and French Guiana’, Human Ecology 52, no. 4 (2024): 823-36; for ancestor narratives, see Tinde van Andel, Harro Maat, and Nicholaas M. Pinas, ‘Maroon women in Suriname and French Guiana: Rice, slavery, memory’. Slavery & Abolition 2024, 45, 187–211.

- Garibaldi, A.; Turner, N. ‘Cultural keystone species: implications for ecological conservation and restoration’. Ecology and Society 2004, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, G.; Barwick, L.; Turpin, M.; Walsh, F.; Laughren, M. Georgia Curran, Linda Barwick, Myfany Turpin, Fiona Walsh, and Mary Laughren, ‘Central Australian Aboriginal songs and biocultural knowledge: Evidence from women’s ceremonies relating to edible seeds’. Journal of Ethnobiology 2023, 39, 354–370. [Google Scholar]

- Jaques Arends, Language and slavery: A social and linguistic history of the Suriname Creoles (Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2017).

- Melvin, J. Herskovits and Frances S. Herskovits, Suriname folk-lore (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936); Jan Voorhoeve and Ursy Lichtveld, Creole Drum: An anthology of Creole literature in Surinam (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975); Henri J.M. Stephen, Winti liederen: Religieuze gezangen in de winticultuur (Schoonhoven: Perfect Service, 2003).

- Richard Price and Sally Price, Two evenings in Saramaka (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991).

- For an example, see Folkway Records, Music from Saramaka: A Dynamic Afro-American Tradition (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1977).

- For an overview of Aluku traditional music, see Kenneth Bilby, ‘Music in Aluku life, yesterday and today’, in Understanding America, the essential contribution of Afro-American music, ed. F. Palacios Mateos (Quito: Centro de Publications PUCE, 2022), 44-63.

- Arends, Language and Slavery, 287, 298.

- Rickman G-Crew, Modo Awasa. G-Crew Music, 2016. Available on YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nctfY3_QLUY (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Curran; et al. ‘Central Australian Aboriginal songs’.

- Wood, Black majority; Carney, Black rice; Edda L. Fields-Black, Deep roots: Rice farmers in West Africa and the African Diaspora (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008).

- Allen; et al. Slave songs; Work, Folk song, Parrish, Slave songs.

- Migeod, W.H. ‘Africa, West: Sierra Leone. Mende songs, preliminary note’. Man 1916, 112, 184–191. Available online: https://www.sierraleoneheritage.org/ (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Margot Van den Berg, ‘Ningretongo and Bakratongo: Race/ethnicity and language variation in 18th century Suriname’. Revue Belge de Philologie et d'Histoire 2013, 91, 735–761.

- Video of Edith Adjako from St. Laurent du Maroni, French Guiana, singing the ‘harvest version’ of the song on camera. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/0Wt4zg6JlHk (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- For the Caribbean, see Emily Zobel Marshall, ‘Anansi, Eshu, and Legba: Slave resistance and the West African trickster’, in Human bondage in the cultural contact zone: Transdisciplinary perspectives on slavery and its discourses, ed. G. Mackenthun (New York: Waxmann, 2010): 171-86; for Suriname, see Herskovits and Herskovits, Suriname folk-lore; Price and Price, Two evenings. Two evenings.

- Van Andel; et al. ‘Maroon women’.

- Video of Rebecca Alimeti from Portal Island, French Guiana, singing the ‘sowing version’ of the song. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/sXX_QxdXBDo (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Michiel van Kempen, ‘Ancestors and migrants: On tradition and reflection in Surinamese singing, storytelling and writing’. Journal of West Indian Literature 2004, 12, 31–51.

- Migeod, ‘Mende songs’, 184.

- Pinas; et al. ‘Vernacular names’, 127.

- Van Andel; et al. ‘Maroon women’.

- Pinas; et al. ‘Vernacular names’, 126.

- Migeod, ‘Mende songs’, 188; Paul Richards, Coping with hunger: Hazard and experiment in an African rice-farming system (London: Routledge, 1986), 168.

- For Mende words for plants in Surinamese Creole, see Tinde van Andel, Charlotte van ‘t Klooster, Diana Quiroz, Alexandra Towns, Sofie Ruysschaert, and Margot van den Berg, ‘Local plant names reveal that enslaved Africans recognized substantial parts of the New World flora’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, E5346-53. For Mende words in Surinamese Creole for certain groups of people, see van den Berg, ‘Ningretongo and Bakratongo’, 741.

- Simone de Souza, Flore du Bénin, Tome 3: Nom des plantes dans les langues nationales Beninoises (Cotonou: Imprimerie Tunde, 2008), 305, 559.

- Roger Blench, Archaeology, languages, and the African past (Lanham: Alta Mira Press, 2006): 219.

- Fields-Black, Deep Roots; Roland Portères, ‘Les noms des riz en République de Guinée’, Journal d'Agriculture Tropicale et de Botanique Appliquée 1965, 12, 369-402; Blench, Archaeology, 219.

- Turner, Africanisms, 128; Blench, Archaeology.

- Béla Teeken, African Rice (Oryza glaberrima) cultivation in the Togo Hills: Ecological and socio-cultural cues in farmer seed selection and development (PhD diss., Wageningen University, 2015); Firmin Ahoua, ‘The phonology-syntax interface in Avikam’, Legon Journal of the Humanities 20 (2009): 123-149; Leo Wiener, Africa and the discovery of America (Philadelphia: Innes & Sons, 1920).

- Wiener, Africa, 236.

- Turner, Africanisms, 153.

- Hugo Schuchardt, ‘Die sprache der Saramakkaneger in Surinam’. Verhandelingen der Koninklijke Akademie van Wetenschappen Amsterdam, 1914; 14, 100.

- Pinas, ‘Vernacular names’.

- The Joshua project, Lele in Guinea (Colorado Springs, 2025). https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/print/19001/GV; Harald Hammarström, Robert Forkel, Martin Haspelmath, and Sebastian Bank, Glottolog 5.1 (Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, 2024). Available online: https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/lele1266 (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- About Ma Akuba in Suriname, see Herskovits and Herskovits, Suriname folk-lore; for other names of Anansi’s wife in the Caribbean. see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anansi (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Maat, H.; Pinas, N.M.; van Andel, T. The role of crop diversity in escape agriculture; rice cultivation among Maroon communities in Suriname. Plants, People, Planet 2024, 6, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judith, A. Carney and Richard N. Rosomoff, In the shadow of slavery: Africa’s botanical legacy in the Atlantic world (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009).

- Lenoir, J.D. The Paramacca Maroons: A study in religious acculturation (PhD diss., New School for Social Research, 1973); Nizaar Makdoembaks, Coffij Makka Makka en het verzet van de Kwinti: Een eeuw overlevingsstrijd van onderduikers in Suriname (Utrecht: de Woordenwinkel, 2023).

- Maat; et al. ‘Escape agriculture’; Thiëmo Heilbron, Botanical relics of the plantations of Suriname (MSc diss., Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2012).

- Parrish, Slave songs.

- Herskovits and Herskovits, Suriname folk-lore, 407; this song is about a pig that eats fallen rice grains.

- Lester P. Monts, ‘Music clusteral relationships in a Liberian-Sierra Leonean Region: A preliminary analysis’, Journal of African Studies 9, no. 3 (1982): 101-115. According to Monts, rice songs are mainly in the Vai and Mende language, but he does not provide any examples. Gordon Innes, ‘The function of the song in Mende Folktales’, in Sierra Leone Language Review, ed. D. Dalby (New York: Routledge, 1965); Migeod, Mende songs. The few songs documented by Innes and Migeod did not resemble the songs we documented in any way.

- Carney, Black Rice.

- Wood, Black majority, 59.

- Eltis, D.; Morgan, P.; Richardson, D. Agency and Diaspora in Atlantic history: Reassessing the African contribution to rice cultivation in the Americas. American Historical Review 2007, 112, 1329–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfrink, T.; van de Hoef, M.J.J.; van Montfort, J.; Bruins, A.L.; van Andel, T. Rice cultivation and the struggle for subsistence in early colonial Suriname (1668–1702). New West Indian Guide 2024, 98, 306–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Loosdrecht, M.; Pinas, N.M.; Awie, J.T.; Becker, F.; Maat, H.; van Velzen, R.; van Andel, T.; Schranz, M.E. Maroon rice genomic diversity reflects 350 years of colonial history. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2024, 41, msae204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Andel; et al. ‘Maroon women’.

- Patrick Nunn, ‘Memories within myth’. American Scientist 2023, 11, 360.

- Arends, Language and slavery, 277.

- Curran; et al. ‘Central Australian Aboriginal songs’.

- Bilby, ‘Music in Aluku Life’, 46.

- Bilby, ‘Music in Aluku Life’, 54.

- Van Andel; et al. ‘Maroon women’; Pinas et al, ‘Mystery of black rice’.

- Arends, Language and slavery, Bilby, ‘Music in Aluku Life’.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).