1. Introduction

Sources: OpenAI, 2025; Microsoft Copilot, 2025

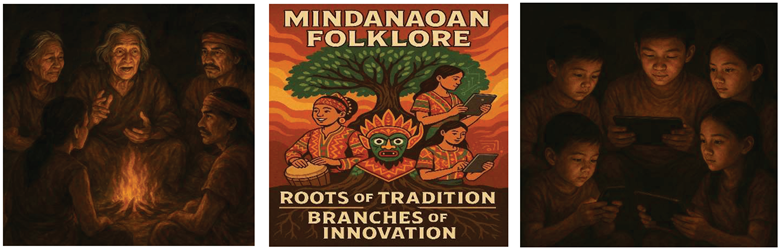

Mindanao’s folklore is a vibrant mosaic of stories, myths, and legends that have been lovingly passed down through generations. Yet today, these rich narratives are quietly slipping away, threatened by the fast pace of modernization and shifting cultural landscapes. This study is a heartfelt call to action to preserve these precious oral traditions before they disappear entirely. Over time, whether through neglect or the unintended effects of globalization, many of Mindanao’s ancestral stories have faded from everyday life, leaving younger generations increasingly disconnected from their roots.

The folklore of Mindanao reflects its diverse peoples-the Lumad, Moro, and Christian communities-each contributing unique tales that capture their values, beliefs, and history (Filipinas Heritage Library, n.d.; Eugenio, 1993). These stories range from heroic epics and animistic myths to moral lessons that once formed the backbone of community identity (Eugenio, 2001; Ramos, 1971). However, the rapid march of modernization has put these oral traditions at risk, as digital media and global influences reshape how people communicate and relate to their heritage. Interestingly, while technology is often seen as a threat to cultural preservation, it also offers new possibilities to keep these stories alive in innovative ways.

This issue goes beyond academic interest--it touches the heart of cultural survival. Traditional storytelling practices are being displaced, and without intentional efforts, future generations may lose access to the deep wisdom embedded in these narratives. This research explores how we can honor the authenticity of Mindanaoan folklore while embracing modern tools like artificial intelligence and digital platforms to revitalize storytelling. It also highlights the vital role of community involvement, because folklore lives and breathes through the people who tell and cherish it (Yu, 2022).

To guide this exploration, the study focuses on several key questions: 1). What traditional methods have sustained Mindanao’s folklore, and how effective are they today? 2). How do forces like modernization and globalization affect the transmission of these stories? 3). What opportunities and challenges do AI-driven storytelling and digital tools present? 4). How can communities actively participate in preservation efforts? And importantly, 5). What ethical considerations must we keep in mind when using technology to archive indigenous narratives?

Answering these questions is not just an academic exercise. The findings aim to support policymakers, educators, cultural advocates, and researchers who are committed to sustaining Mindanao’s rich oral heritage in ways that resonate with contemporary life (Lara & Franco, 2022). Indeed, this study envisions a future where tradition and innovation coexist harmoniously, allowing Mindanaoan folklore to continue echoing through generations, even as the world changes around it.

2. Theoretical Framework

Preserving Mindanaoan folklore is more than just a cultural task—it is a vital effort to protect the heart and soul of the region’s heritage in the face of rapid modernization. As we have seen, these oral traditions-whether from the Lumad, Moro, or Christian-influenced communities-have long carried the wisdom, values, and identity of the Mindanaoan people. Yet, without conscious efforts to conserve them, these stories risk fading away as each generation drifts further from their ancestral roots. To better understand how these narratives endure, adapt, and can be revitalized today, this study draws on four key theoretical perspectives.

First, Walter Ong’s Oral Tradition Theory reminds us of the power and resilience of spoken word. Ong highlights how oral storytelling thrives in cultures where face-to-face communication and communal sharing keep memories alive (Ong, 1982). Mindanaoan folklore has traditionally depended on this intimate exchange--through rituals, performances, and intergenerational dialogue. But as literacy spreads and digital media reshape how we communicate, the old ways need to evolve. The challenge is to find new paths-such as AI-assisted storytelling or digital archives-that preserve the spirit of oral tradition even in a high-tech world.

Building on this, Edward Sapir’s Cultural Transmission Theory shows us that culture is never static. Traditions shift and change as they pass from one generation to the next, influenced by language, society, and history (Sapir, 1921). Mindanao’s epics and myths, like the Darangen of the Maranao or the Hudhud chants of the Ifugao, have long adapted to stay meaningful (Ong, 1982). Yet, the move from oral to written or digital formats raises important questions about how to keep these stories authentic while making them accessible to modern audiences.

Next, Vladimir Propp’s work on Folklore Morphology helps us understand the deep structures behind these stories (Propp, 1928). His analysis of recurring motifs and character roles reveals universal patterns that shape indigenous narratives--from heroic quests in Maranao epics to animistic tales among the Lumad. Recognizing these patterns is crucial; it ensures that as we bring folklore into new formats or institutions, we respect its cultural core instead of distorting it.

Finally, Emese Ilyefalvi’s concept of Digital Folkloristics offers a hopeful vision for the future (Ilyefalvi, 2019). By using AI tools, digital archives, and interactive storytelling platforms, we can document and breathe new life into endangered narratives. For Mindanao, this means reconstructing fragmented stories, preserving endangered languages, and creating immersive experiences that engage younger generations. But as we embrace technology, ethical care is essential--to make sure these digital efforts honor the people and traditions they represent, rather than replacing them.

Together, these theories form a balanced framework for this study. They invite us to see Mindanaoan folklore as a living tradition--one that survives through oral performance, adapts through cultural shifts, holds deep structural meaning, and can be revitalized through thoughtful digital innovation. By weaving together heritage and technology, this research hopes to help Mindanao’s stories continue to resonate for generations to come.

3. Literature Review

Folklore remains a vital thread weaving together the past and present, carrying the stories, values, and identities of communities across generations. In today’s rapidly changing world, preserving these narratives is more important than ever, especially in culturally rich regions like Mindanao, where indigenous and syncretic folklore face the twin pressures of modernization and globalization. This review explores how oral traditions sustain cultural memory, how folklore adapts over time, and how new digital tools offer promising ways to keep these stories alive.

At its core, folklore is a living tradition, passed down through storytelling, song, ritual, and communal practice. Walter Ong’s work reminds us that oral storytelling thrives on personal engagement, ritual, and shared experience, which together reinforce collective memory and identity (Ong, 1982). In Mindanao, indigenous communities, like in Bukidnon’s Matigsalug indigenous community, have long relied on these oral methods to transmit epic tales, animistic myths, and historical accounts, keeping folklore vibrant and relevant. However, as younger generations increasingly turn to digital communication, the continuity of these oral traditions faces disruption, demanding adaptive strategies that bridge old and new ways of sharing stories (Nyiramukama, 2025).

Folklore is not static but evolves with the cultures that carry it. Edward Tehrani highlights how folk narratives shift in response to linguistic, social, and historical changes, allowing them to resonate with new generations without losing their core meaning (Tehrani, 2023). Mindanaoan epics like the Darangen of the Maranao exemplify this adaptability, maintaining cultural significance even as storytelling modes change (TaasNooPilipino, 2016). Yet, the rise of digital platforms brings both opportunities and challenges. While AI-driven storytelling and virtual archives can help preserve and popularize folklore, they also raise questions about maintaining authenticity and respecting cultural ownership (Almeida et al., 2024; Shah, 2023).

The richness of Mindanao’s folklore is evident in its vivid myths and legends, which carry deep symbolic and historical significance. Stories such as the Sarimanok--a celestial bird symbolizing prosperity--and the Imprisoned Naga, a dragon from Samal mythology, embody spiritual beliefs and cultural values (Kahimyang Project, n.d.; TaasNooPilipino, 2016). Other tales evoke the supernatural and the mysterious, like the vengeful Mantiyanak of Bukidnon or the fearsome Tarabusaw said to haunt Mt. Matutum. Maritime myths such as the Kurita of Zamboanga’s waters and the Seven-Headed Bird of Mt. Gurayn reinforce themes of guardianship and respect for nature. These narratives serve not only as cultural markers but also as repositories of environmental and social wisdom (Asamoah-Poku, 2024).

Beyond mythical creatures, Mindanao’s folklore includes legends tied to specific places and historical events. The tragic love story behind Maria Cristina Falls and the Sultan’s Beard myth from Lake Lanao reflect local histories and values. Spirits like the Engkanto of Bukidnon’s forests and the Berbalangs of Sulu illustrate ancestral beliefs about unseen forces shaping human fate (Kahimyang Project, n.d.). These stories are woven into the cultural fabric, reinforcing identity and community cohesion. However, without active preservation, they risk fading into obscurity.

It is wonderful to note how fertile are the lores and myths of Mindanao. In the heart of Mindanao, where the mountains breathe mist and the rivers whisper secrets, ancient beings stir beneath the surface of reality. Some bring blessings. Others—ops, only terror. The researchers’ in-depth readings brought forth their brilliance and significance. These stories are not merely spoken—they breathe, shaping the lands, binding the past to the present (Gaspar, 2022).

High above Lanao del Sur, for example, the Sarimanok spreads its dazzling wings, its feathers burning like liquid fire against the sky. It is more than a bird—it is a promise, a messenger from the divine. When it appears, fortune follows, though few are ever deemed worthy of its presence (Monteclar, 2021). But beyond the mortal realm, trapped in the fabric of the heavens, the Imprisoned Naga coils in silent agony. Once a mighty celestial dragon, it now twists within unseen chains, yearning for release (Sevilla, 2022).

The Dark Watchers. There are creatures that walk the land—some seen, others only felt. Deep in Bukidnon’s tangled forests, the Mantiyanak waits, its wails sharp enough to cut through silence like a blade. It does not forget, does not forgive. It hunts the careless men who dare wander alone (Eslit, 2023). In the shadows of Mt. Matutum, the Tarabusaw prowls, its monstrous form neither man nor beast. Its hunger is endless, its fury relentless (Arguillas, 2022).

But even the open seas offer no escape. In Zamboanga, the Kurita stretches its many limbs through the dark waters, dragging fishermen into depths where no prayers can be heard (Revoldila, 2025). And high above, the Pah takes flight over Sulu, its wings so immense that the world beneath drowns in its shadow. But even it must bow before the Seven-Headed Bird of Mt. Gurayn—a creature with seven piercing gazes, always watching, always waiting (Tadiar & Villanueva, 2017).

The Silent Ones. Some horrors do not move in monstrous shapes. They live within whispers, in the corners of dreams. The Engkantos, spirits of the wild, choose their favorites and their victims alike, bending fate with unseen hands. Some are kind. Others twist destiny beyond repair (Gully Books, 2023). In Lake Lanao, a trickster stirs—the Sultan’s Beard, a mischievous spirit that steals the most prized possession of rulers—their dignity itself (Monteclar, 2021).

And then, there are the flesh-hunters. The Berbalangs drift through the skies, their hollow eyes glowing with hunger, feeding on the unsuspecting (Sevilla, 2022). Beneath the ground, in unmarked graves, the Balbal creeps between tombs, prying open coffins with clawed fingers, feasting on the dead (Gaspar, 2022). But sometimes, nightmares wear familiar faces. The tale of Maria Labo is whispered in fearful tones—a woman twisted by darkness, an aswang who devoured her own children (Arguillas, 2022).

The Fire and the Depths. From the waters, eerie lights flicker—the Santilmo, a restless fire spirit leading wanderers into oblivion (Eslit, 2012). In places untouched by light, something unnatural moves—the Sigbin, a creature as strange as it is feared, walking backward, its ears clapping, its presence warping the world around it (Revoldila, 2025). And lurking in the shadows is the Manananggal, splitting its own body apart, taking flight under the moon, hunting pregnant women as they sleep, its tongue snaking through open windows (Tadiar & Villanueva, 2017).

Yet not all spirits bring fear. The Diwatas, ancient watchers, linger within the rivers and trees, protecting those who honor them. The Bagobo speak of Erehe, the guardian of the sky, his presence felt in the wind (Monteclar, 2021). But even with the deities watching, something else stands at the edge of the firelight—the Amamarang, a faceless shadow blocking paths in the night, waiting, always waiting (Gully Books, 2023).

With all these lores and myths, Mindanao’s stories are not just words. They are footsteps in the dark, warnings carried on the wind, names whispered with reverence and fear. They are the heartbeat of a land that remembers—and if you listen closely, you might hear them calling.

4. Methodology

Preserving Mindanaoan folklore requires a thoughtful approach that balances cultural authenticity with academic rigor. Given the complex nature of oral traditions, this study adopted a qualitative research design, combining folklore literature analysis, interviews, and field observations. This multi-method strategy allowed for a rich and nuanced exploration of endangered narratives, situating them within their historical, social, and technological contexts. By involving indigenous communities and incorporating digital tools, the study bridged traditional storytelling practices with modern preservation techniques.

The first phase involved a thorough review of Mindanaoan folk and myth literature, including manuscripts, indigenous stories, and historical records. These materials provided essential insights into the recurring themes, motifs, and transmission patterns that characterize the region’s folklore. Analyzing these texts helped identify narratives at risk of disappearing and enabled a comparative look at how storytelling methods have evolved over time. This qualitative broad examination (Creswell & Creswell, 2018) ensured that diverse cultural groups across Mindanao were represented fairly and inclusively.

Interviews played a crucial role in capturing firsthand perspectives from indigenous elders, historians, and cultural practitioners. Ten participants, coded as “MP-1 through MP-10”, to mean Mindanao Participants, shared their experiences and knowledge, enriching the study with personal accounts of how folklore is transmitted and preserved. Their narratives revealed the subtle ways folklore adapts, the challenges it faces in daily life, and the community efforts to keep these stories alive. By centering this lens, the study honored the intangible and sentimental lived aspects of storytelling that cannot be fully grasped through texts alone (American Folklore Society, 2018).

Field observations complemented these methods by documenting actual chants and storytelling events, rituals, and oral traditions within local communities. Observing these performances firsthand provided a window into how stories are enacted and received, especially during ceremonial occasions where myths and legends are shared as part of communal life. Engaging with these practices in their natural settings helped preserve the authenticity of folklore and captured how storytelling continues to evolve. The researcher’s Matigsalug encounter made this possible. Here, data collection continued until saturation was reached--when no new themes or storytelling methods emerged--signaling a comprehensive understanding had been achieved (Braun & Clarke, 2012).

For data analysis, thematic analysis was employed combining traditional method and modern technology using Orange Data Mining software, a powerful tool for identifying patterns across literature, interviews, and ethnographic notes. This systematic approach allowed the researcher to code recurring motifs, characters, and narrative structures, providing a thorough interpretation of cultural themes while maintaining methodological rigor. Triangulation was used to cross-validate findings from multiple data sources, enhancing the reliability of the results and minimizing researcher bias (Demšar et al., 2013; Braun & Clarke, 2012).

Ethical considerations were carefully observed throughout the study. All participants gave informed consent, ensuring their voluntary and informed involvement. The research prioritized respect for indigenous knowledge and traditions, safeguarding sacred narratives from misrepresentation or exploitation. Transparency and cultural sensitivity guided the entire process, fostering a collaborative relationship with the communities whose stories form the foundation of Mindanaoan heritage (American Folklore Society, 2018).

5. Findings & Discussion

The preservation of Mindanaoan folklore is deeply rooted in oral traditions but faces significant challenges amid modernization, globalization, and shifts in cultural transmission. While traditional storytelling remains vital, emerging digital innovations offer new pathways for conservation. This section integrates key theoretical perspectives--Ong’s Oral Tradition Theory, Sapir’s Cultural Transmission Theory, Propp’s structural analysis, and Ilyefalvi’s Digital Folkloristics--to contextualize folklore preservation within both historical and contemporary frameworks, supported by insights from participant interviews, literature analysis, and field observations.

A. Summarized answers to the five research questions:

Mindanao’s folklore is a living treasure that reflects the rich cultures, histories, and values of its many communities. These stories, myths, legends, and songs have been passed down orally from generation to generation, shaping the identity of the people. Yet, in today’s fast-changing world, these traditions face many challenges-from the influence of modernization and globalization to shifts in language and ways of sharing stories. At the same time, new technologies like artificial intelligence and digital tools are opening up exciting possibilities to help preserve and share these cultural treasures. To better understand how to protect Mindanaoan folklore, it is important to look at both the traditional ways it has been kept alive and the new methods that can support its survival. Below is a summary of key insights based on five important questions about preserving this heritage.

1. What are the key traditional methods used in Mindanao to preserve folklore? Mindanao’s folklore is preserved through oral storytelling, passed down by elders and cultural experts during community gatherings, rituals, and celebrations (Bayangkong, n.d.). These narratives shape social values, beliefs, and history, ensuring cultural identity endures across generations (Yu et al., 2022). While oral tradition remains central, communities actively document and transcribe these stories to safeguard them for the future (Manidoc & Tsuji, 2022). Fortunately, local literary initiatives, such as the Iligan National Writers Workshop held annually at MSU-IIT, continue to foster storytelling and uphold Mindanaoan folklore in contemporary discourse.

2. How do modernization and globalization impact the transmission of Mindanaoan folklore? Modern life and global influences have made it harder to keep these stories alive in their traditional forms (Yu & Catalina, 2022). Changes like language loss, fewer storytellers, and outside cultural pressures have weakened the way folklore is passed on (Manidoc & Tsuji, 2022). Sad to note, only a few communities are actively working to protect their languages and traditions, teaching their children and encouraging cultural pride to resist these challenges (Aleria, 2020)."

3. What role do AI-driven storytelling and digital tools play in folklore preservation? New digital technologies, including AI, offer powerful ways to capture, analyze, and share folklore (Ražnatović, 2023). These tools help turn oral stories into digital archives, podcasts, and interactive platforms that can reach wider audiences, especially younger people (Shah, 2023). When used thoughtfully and with respect for the communities involved, these technologies can breathe new life into traditional stories and make them more accessible (Yu, 2022).

4. How can community engagement strengthen efforts to safeguard Mindanaoan folklore? Community involvement is essential for meaningful cultural preservation (Yu, Manidoc, & Tsuji, 2022). By collaborating with indigenous groups, elders, cultural advocates, and educational institutions, efforts remain respectful and impactful (Buendia et al., 2006). Initiatives such as storytelling sessions, workshops, and documentation projects empower local communities to safeguard their heritage and instill a deeper appreciation among younger generations (Esteban, Casanova, & Esteban, 2011). However, such endeavors require support and funding, and unfortunately, interest from potential patrons—including local politicians—has waned, leaving preservation efforts struggling without the necessary backing (Eugenio, 2007)

5. What are the ethical considerations in using AI for digitally archiving indigenous folklore? Using AI and digital tools to preserve folklore comes with important responsibilities (Fewster & Arias-Hernandez, 2024). It is crucial to respect the rights of indigenous communities, obtain their consent, and protect sensitive cultural information (Gallamaso, 2024). The process must avoid misuse or misrepresentation of stories, ensuring that communities stay in control of how their cultural heritage is shared and used (Bapanamba et al., 2024). Openness, respect, and partnership with the people whose stories are being preserved are essential. Commercialization is seen as corrupting the core tenets of these narratives

This summary underscores the pressing need to preserve Mindanaoan folklore—balancing respect for tradition with innovative methods to keep stories alive. If decisive action is not taken now, these narratives risk fading into obscurity. Safeguarding this cultural heritage requires immediate commitment, ensuring that the voices of communities are honored while embracing tools that will sustain these rich legacies for future generations.

B. Key insights:

Traditional Preservation Methods in Mindanao. Mindanaoan folklore has endured primarily through oral storytelling, rituals, and communal engagement, closely aligning with Walter Ong’s Oral Tradition Theory (1982). Ong emphasizes that oral cultures rely on memory, repetition, and communal reinforcement to sustain narratives, which are performative and immersive rather than simply written records. In Mindanao, myths and legends are transmitted through ceremonial storytelling, where elders recite tales during festivals, rites of passage, and religious gatherings, embodying Ong’s concept of “psychodynamics of orality” (Putong, 2025; Zam398, 2018).

A local community elder (MP-3) captured the essence of oral tradition, stating, “Storytelling is not just about words; it is about rhythm, movement, and the voice of ancestors speaking through us.” This sentiment underscores the performative nature of storytelling, aligning with Ong’s concept of narrative as a communal act that preserves cultural memory through engagement and embodiment. Observations of ceremonial storytelling further affirm its ritual precision, reinforcing social ties and deepening spiritual connections (Monteclar, 2021; TaasNooPilipino, 2016). Yet, as the current generation’s interest wanes, the pressing question remains—how can this rich tradition be sustained?

Challenges Faced in Folklore Transmission. The transmission of folklore is increasingly affected by modernization and globalization, reflecting Edward Sapir’s Cultural Transmission Theory (1921), which posits that language and narratives evolve across generations in response to social change (Putong, 2025). In Mindanao, many younger people are less fluent in indigenous languages, which threatens the authenticity and depth of folklore.

As a local teacher (MP-7) lamented, “Our myths are still here, but the words that once carried them are fading.” This poignant reflection underscores Sapir’s assertion that language is central to cultural continuity; when linguistic shifts occur, folklore risks losing its original meaning and richness. Additionally, commercialization and tourism have repackaged some myths, sometimes diluting their sacred and historical significance (Monteclar, 2021; Zam398, 2018). The thematic analysis using Orange Data Mining revealed patterns of narrative simplification and loss of linguistic nuance in digitally archived folklore, emphasizing the need for culturally sensitive curation (Demšar et al., 2013).

Indigenous Knowledge and Folklore Structures. The Lumad and Moro traditions play a crucial role in preserving folklore, resonating with Vladimir Propp’s structural analysis (1928), which identifies recurring motifs, archetypes, and symbolic elements that define cultural narratives (Putong, 2025). Many Mindanaoan myths follow heroic cycles, supernatural interventions, and moral lessons.

A researcher specializing in indigenous cultures (MP-5) expressed this connection, stating, “Our ancestors shaped these stories not just to entertain but to teach us how to live.” This aligns with Propp’s view that folklore serves educational and cultural functions, reinforcing social values and historical continuity. The consistency of these narrative structures across diverse Mindanaoan communities suggests a shared framework that strengthens communal identity and resilience (Monteclar, 2021; TaasNooPilipino, 2016).

Digital Innovations in Folklore Preservation. The rise of AI-driven storytelling and digital folklore archives aligns with Emese Ilyefalvi’s Digital Folkloristics (2019), which advocates for computational tools to document, categorize, and analyze folklore while preserving cultural integrity (Gully Books, 2023). An author and digital archivist (MP-2) shared enthusiasm for these innovations: “Seeing our stories archived online feels like safeguarding history in a way our ancestors never imagined.” This reflects the potential of digital tools to complement oral traditions and increase accessibility.

Using Orange Data Mining, the study identified recurring motifs and narrative structures across texts, interviews, and observations, demonstrating how technology can enhance thematic analysis. However, as Ilyefalvi cautions, digital preservation must remain culturally sensitive, ensuring indigenous communities retain ownership and control over their narratives (Putong, 2025; Zam398, 2018). A local policymaker (MP-6) emphasized this ethical imperative: “Our stories belong to us. If they are digitized, they must remain in our hands.”

Strategies for Sustainable Preservation. A hybrid approach blending traditional storytelling with digital tools offers a sustainable path forward. Community-led folklore archives, educational programs, and AI-assisted documentation help maintain authenticity while adapting to modern platforms. A student and cultural advocate (MP-10) captured this balance succinctly: “To preserve our myths, we must let them breathe in both the old ways and the new.” This reflects the adaptability necessary for folklore to thrive in contemporary contexts (Revoldila, 2025; Eslit, 2023).

This approach echoes Ong’s concept of “secondary orality,” where oral culture is influenced by literacy and digital media but retains its communal and performative essence (Ong, 1982). By integrating oral tradition with digital innovations, Mindanaoan folklore can continue evolving without losing its cultural core (Tadiar & Villanueva, 2017).

Ethical Considerations in AI-Based Folklore Archiving. Using AI for folklore preservation requires informed consent, cultural sensitivity, and ethical safeguards. Indigenous communities must retain control over their narratives to prevent exploitation or misrepresentation. MP-6’s caution highlights this necessity: “Our stories belong to us. If they are digitized, they must remain in our hands” (American Folklore Society, 2018).

The study adhered to ethical guidelines by securing informed consent and prioritizing respect for indigenous knowledge, consistent with best practices in folklore research (American Folklore Society, 2018). This collaborative and transparent approach fosters trust and empowers communities as active partners in preservation (Putong, 2025).

Overall, Mindanaoan folklore stands at a crossroads, requiring strategic intervention to withstand contemporary shifts while remaining deeply rooted in its indigenous essence. By integrating oral traditions, cultural transmission theories, structural folklore analysis, and digital innovations, folklore preservation can advance toward sustainable revitalization. This ensures that cultural narratives remain vibrant and meaningful for generations to come (Gaspar, 2022; Arguillas, 2022; Sevilla, 2022).

C. Thematic analysis

Mindanao’s folklore is not only a cultural treasure but also a living expression of the people’s identity, memories, and values. Through the use of Orange Data Mining, this study conducted a thematic and sentiment analysis of rich qualitative data gathered from indigenous narrators and cultural practitioners (MP-1 to MP-10). This approach allowed for a deeper understanding of both the content and emotional undertones embedded in their narratives. Grounded in Ong’s Oral Tradition Theory, Sapir’s Cultural Transmission Theory, and Propp’s Structural Analysis, the analysis reveals how folklore is experienced, valued, and challenged in contemporary contexts. These striking ten (10) themes emerged, each reflecting not only key patterns but also the heartfelt sentiments and lived realities of the participants.

1. Oral Storytelling as Cultural Backbone. Participants expressed deep affection and reverence for oral storytelling as the heart of their cultural identity. MP-3 shared with warmth, “Our stories come alive when shared around the fire, connecting us to our ancestors.” Sentiment analysis showed predominantly positive emotions linked to storytelling, reflecting pride and belonging. Ong’s theory supports this by highlighting orality as a vital means of cultural continuity.

2. Language as a Vessel of Identity. Language emerged as a powerful symbol of identity and cultural survival. MP-7’s statement, “When we lose our language, we lose the soul of our stories,” carried a tone of concern and urgency. Sentiment analysis detected strong feelings of loss and determination. Sapir’s Cultural Transmission Theory underscores language as the medium through which culture is transmitted and preserved.

3. Impact of Modernization and Language Shift. Participants expressed mixed emotions-frustration and sadness-about the impact of modernization. MP-1 lamented, “Young people prefer social media; they forget our old tales.” Negative sentiments dominated this theme, highlighting fears of cultural erosion. This aligns with broader concerns about globalization diluting indigenous knowledge.

4. Role of Indigenous Narrators as Custodians. There was a profound respect and gratitude toward elders as cultural custodians. MP-5 reflected, “Our elders hold the wisdom and the stories; without them, the stories fade.” Sentiment analysis showed reverence and anxiety about the dwindling number of narrators. Propp’s structural analysis helps us understand the narrator’s role as a key “function” in maintaining narrative integrity.

5. Digital Tools as Preservation Aids. Participants showed cautious optimism toward digital technologies. MP-9 expressed hope: “Using recordings and digital stories helps our youth connect with our heritage.” Sentiments here were a blend of hope and cautious trust, emphasizing the need for respectful application. This theme illustrates how tradition and innovation can coexist.

6. Community Engagement and Empowerment. Community involvement was described with enthusiasm and pride. MP-4 said, “When we gather to share and teach, our culture grows stronger.” Positive sentiments dominated, reflecting empowerment and collective identity. This supports the idea that cultural preservation is a social, participatory process.

7. Educational Integration of Folklore. Participants viewed education as a critical pathway for transmission. MP-8 noted, “Teaching our stories in schools helps children appreciate who they are,” with a hopeful and encouraging tone. Sentiment analysis showed optimism and commitment to cultural sustainability through formal education.

8. Challenges of Commercialization and Misrepresentation. This theme elicited strong negative emotions such as frustration and protectiveness. MP-2 warned, “Some stories are sold without respect, losing their true value.” Participants expressed concern about cultural exploitation, highlighting the need for ethical stewardship.

9. Intergenerational Transmission and Adaptation. Participants acknowledged the evolving nature of folklore with acceptance and resilience. MP-6 observed, “We change stories to fit our times but keep their heart.” Sentiments here were balanced-accepting change while valuing tradition-reflecting Propp’s view of narrative functions adapting over time.

10. Ethical Stewardship in Digital Archiving. Respect and caution were prominent in discussions about digital archiving. MP-10 emphasized, “Our stories belong to us; technology must honor that,” with a tone of firm protectiveness. Sentiment analysis revealed strong feelings of ownership and the need for ethical frameworks to guide technology use.

This thematic and sentiment analysis highlights how preserving Mindanaoan folklore is deeply woven into the lived experiences and emotions of its custodians. Their voices reflect pride, hope, resilience, and concern, emphasizing that folklore is not merely a collection of past narratives but an evolving, vital part of community identity. Through Orange Data Mining, intricate layers of meaning emerged, revealing how these stories continue to function and adapt in a rapidly changing world. This realization underscored the need for a strategic response, leading to the development of the proposed program to safeguard and sustain these cultural legacies.

6. Proposed Program for Folklore Preservation

Introduction and Rationale

After carefully considering the results of this study, which highlighted both the resilience and the vulnerabilities of Mindanaoan folklore, the need for a comprehensive preservation strategy became clear. The data revealed that while oral traditions remain vital, they are increasingly threatened by modernization, language shifts, and the diminishing role of indigenous narrators. At the same time, the study showed promising opportunities in digital technologies and community engagement to revitalize and sustain these cultural narratives.

In response to these findings, the Mindanao Folklore Revitalization Program (MFRP) emerged as a practical and culturally dynamic sensitive solution. This program is designed to bridge traditional storytelling practices with contemporary preservation strategies, ensuring that Mindanao’s rich folklore heritage is documented, celebrated, and passed on to future generations. By integrating community collaboration, educational initiatives, and digital innovation, the MFRP directly addresses the challenges and leverages the opportunities identified in the research.

Program Title

Mindanao Folklore Revitalization Program (MFRP). This title reflects the program’s dual focus on revitalizing endangered oral traditions and leveraging modern tools to ensure their sustainability and accessibility.

Objectives

Document oral traditions, myths, and legends across Mindanaoan communities.

Digitize and archive folklore materials using AI-driven tools.

Educate and engage local schools and communities through storytelling initiatives.

Support Indigenous Narrators by providing platforms for cultural expression.

Develop interactive resources such as digital libraries, podcasts, and AI-generated visual storytelling.

Methodology of Implementation, Activities, and Expected Outcomes

| Methodology of Implementation |

Activity |

Person(s) Involved |

Time Frame |

Budget Allocation (PHP) |

Expected Outcomes |

| Community Collaborations |

Establish partnerships with schools, indigenous groups, cultural organizations, and local gov’t. |

Program coordinators, community leaders, educators |

Months 1–3 |

₱300,000 |

Strengthened cultural awareness and appreciation among Mindanaoan communities. |

| Organize community workshops and consultation meetings. |

Cultural workers, local elders, facilitators |

Months 4–6 |

₱250,000 |

|

| Digital Innovations |

Deploy AI tools and Orange Data Mining for folklore digitization and thematic analysis. |

IT specialists, digital archivists, researchers |

Months 2–8 |

₱500,000 |

Expanded folklore archives accessible to researchers, educators, and the public. |

| |

Develop digital storytelling platforms (podcasts, visual stories, gamification). |

Multimedia artists, programmers, authors |

Months 6–12 |

₱400,000 |

|

| Fieldwork & Documentation |

Conduct interviews with indigenous narrators and elders. |

Researchers, local community guides |

Months 1–6 |

₱350,000 |

Sustainable digitalization and preservation of indigenous narratives. |

| Record rituals, live storytelling events, and cultural performances. |

Ethnographers, videographers, sound engineers |

Months 3–9 |

₱300,000 |

|

| Educational Integration |

Develop culturally responsive learning modules that include local folklore and myth studies. |

Curriculum developers, educators, cultural experts |

Months 4–10 |

₱350,000 |

Increased engagement of younger generations with their cultural heritage through formal education. |

| Integrate local folklore and myths into the formal school curriculum across Mindanaoan schools. |

Department of Education, school administrators, teachers |

Months 6–12 |

₱200,000 |

Institutionalized folklore education ensuring sustained cultural awareness and identity formation among students. |

| |

Conduct teacher training workshops to effectively deliver folklore and myth content in classrooms. |

Teacher trainers, cultural practitioners |

Months 7–11 |

₱150,000 |

Enhanced teacher capacity to teach indigenous narratives authentically and engagingly. |

| |

Pilot folklore education programs in selected schools with monitoring and feedback mechanisms. |

Teachers, school administrators, program evaluators |

Months 8–12 |

₱100,000 |

Continuous improvement and adaptation of folklore curriculum based on pilot feedback. |

| Public Awareness Campaign |

Launch social media campaigns showcasing folklore stories and program updates. |

Social media managers, cultural advocates |

Months 6–12 |

₱150,000 |

Enhanced public appreciation and support for Mindanaoan folklore. |

| Organize cultural festivals and exhibitions featuring storytelling performances and digital displays. |

Event organizers, artists, community groups |

Months 9–12 |

₱400,000 |

|

Summary of Estimated Budget: ₱3,950,000

This program is intentionally designed to be adaptable and community-centered, reflecting the voices and needs expressed by indigenous narrators, educators, and cultural workers during the study. By combining traditional knowledge with modern technology and formal education, the MFRP offers a sustainable path forward to keep Mindanao’s folklore alive, vibrant, and meaningful for generations to come.

7. Conclusion and Recommendations

This research article has underscored the vital importance of preserving Mindanaoan folklore as a fundamental expression of the region’s rich cultural identity, history, and values. The use of a qualitative research method, involving in-depth reviews of scholarly published articles, interviews, and observations, was instrumental in completing this study. The comprehensive literature review provided a solid theoretical foundation and contextual understanding, while the saturated interviews with indigenous narrators and cultural practitioners substantiated the data by offering rich, firsthand sentimental insights into the lived experiences and challenges of folklore transmission. Meanwhile, direct observations of storytelling rituals and cultural practices enriched the findings by capturing the performative and communal aspects of folklore that are often lost in textual analysis alone. The application of relevant theories-such as Ong’s Oral Tradition Theory, Sapir’s Cultural Transmission Theory, and Propp’s structural analysis-guided the data analysis by helping to interpret how folklore is transmitted, transformed, and sustained within communities. The findings reveal that while oral storytelling remains a powerful and enduring medium for cultural transmission, it is increasingly threatened by factors such as neglect, modernization, language shift, and the commercialization of cultural narratives. The research also highlights the critical role of indigenous narrators and communities in maintaining these traditions, alongside the challenges posed by diminishing intergenerational transmission. However, the study recognizes the potential of digital technologies and community engagement as promising avenues for safeguarding folklore, provided they are applied with cultural sensitivity and respect for indigenous ownership. Overall, the preservation of Mindanaoan folklore requires a multifaceted and dynamic approach that balances respect for tradition with innovative strategies to ensure its continuity and vitality. God forbid, if these narratives die, Mindanao’s language, culture, and identity will die with them!

In light of the study’s stark findings, the following recommendations are proposed to key stakeholders to support the preservation and revitalization of Mindanaoan folklore: Policy makers are encouraged to develop and implement supportive cultural policies, allocate sustainable funding, and foster collaborative partnerships among government agencies, indigenous communities, and educational institutions. Learning institutions and educators should integrate local folklore and myth studies into school curricula, provide teacher training on culturally responsive pedagogy, and actively engage students in storytelling and documentation activities. Conservationists and cultural workers must prioritize dutiful engagement with indigenous communities, support community-led preservation initiatives, and promote ethical digital archiving practices that protect cultural ownership. Students and researchers are urged to participate in interdisciplinary fieldwork and studies that deepen understanding of folklore’s cultural significance and contribute to advocacy efforts. To operationalize these recommendations, the Mindanao Folklore Revitalization Program (MFRP) is hereby proposed as a comprehensive framework that combines documentation, digitization, education, and public engagement to ensure the sustainable preservation and dynamic transmission of Mindanao’s rich oral traditions. By embracing these roles and utilizing the MFRP, stakeholders can collectively safeguard Mindanaoan’s fading folklore, ensuring it remains a vibrant and meaningful part of cultural life for generations to come.

Author Contribution:

The author is solely responsible for conceiving and designing this article, gathering the data, and writing the entire manuscript.

Funding Statement:

This research was conducted without any specific financial support from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agencies.

Declaration of Interest:

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments:

The author extends gratitude to the SMCII Library, Google Scholar, Mendeley, ResearchGate, Academia, Scopus, various AI applications, and Microsoft Copilot for their invaluable contributions in providing illustrations, scholarly insights, and additional information that were instrumental in formulating discussions and completing this research article.

References

- Almeida, P. , Teixeira, A., Velhinho, A., Raposo, R., Silva, T., & Pedro, L. (2024). Remixing and repurposing cultural heritage archives through a collaborative and AI-generated storytelling digital platform. ACM International Conference on Interactive Media Experiences Workshops.

- American Folklore Society. (2018). A code of ethics for folklore research and publication. Journal of American Folklore, 131(520), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Arguillas, C. (2022). Writing Mindanao, Righting Mindanao: 59 Books Published During the Pandemic.

- Asamoah-Poku, F. (2024). Preserving traditional Ghanaian folklore through storytelling. European Modern Studies Journal, 8(2), 26-45. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. , & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Demšar, J. , Curk, T., Erjavec, A., Gorup, Č., Hočevar, T., Milutinović, M., Mozina, M., Polajnar, M., Toplak, M., Staric, A., Stajdohar, M., Umek, L., Zagar, L., Zbontar, J., Zitnik, M., & Zupan, B. (2013). Orange: Data mining toolbox in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 14(Aug), 2349–2353.

- Eslit, E. (2023). Resilience of Philippine Folklore: An Enduring Heritage and Legacy for the 21st Century. International Journal of Education, Language, and Religion. [CrossRef]

- ______________ (2012). Philippine Folklore Forms: An Analysis. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320553602_Philippine_Folklore_Forms_An_Analysis.

- Eugenio, D. L. (1993). Philippine folk literature: The legends. University of the Philippines Press.

- Eugenio, D. L. (2001). Philippine folk literature: The myths. University of the Philippines Press. [CrossRef]

- Filipinas Heritage Library. (n.d.). The Lumad of Mindanao.

- Gaspar, K. (2022). Writing Mindanao, Righting Mindanao: 59 Books Published During the Pandemic. MindaNews.

- Gully Books. (2023). Get Your Hands on the Latest Mindanao Literature.

- Ilyefalvi, E. (2019). Digital folkloristics: Archiving and analyzing folklore in the digital age. Folklore Studies Journal.

- Kahimyang Project. (n.d.). Mythology of Mindanao: A Moro folk tale.

- Lara, F. J. , & Franco, B. Y. (2022). Identity-based conflicts and the politics of identity in Eastern Mindanao. University of the Philippines Center for Integrative and Development Studies.

- Microsoft Copilot. (2025). Response to user query on folklore research methodology. Microsoft AI Chat. Retrieved from https://copilot.microsoft.com.

- Monteclar, A. (2021). The Legends of the Mythical Creatures of Mindanao. VisMin.ph.

- Monteclar, A. (2021). The Legends of the Mythical Creatures of Mindanao. VisMin.ph.

- Nyiramukama, D. K. (2025). The Role of Folklore in Modern Society. IDOSR Journal of Arts and Management, 10(1), 32-35.

- Ong, W. J. (1982). Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. Methuen.

- OpenAI (2025) explained that folklore often reflects deep-rooted cultural values.

- Propp, V. (1928). Morphology of the folktale. Leningrad University Press. (Reprinted by University of Texas Press, 1968).

- Putong, J. K. M. (2025). Cultural communities in Mindanao. Academia.edu.

- Ramos, M. D. (1971). The creatures of Philippine lower mythology. University of the Philippines Press.

- Ražnatović, A. (2023). Interactive digital storytelling in cultural heritage: Innovative approach to sustainable development. Academia.edu.

- Revoldila, E. (2025). Folklore in Philippine Schools. Academia.edu.

- Sapir, E. (1921). Language: An introduction to the study of speech. Harcourt, Brace & World. [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, T. (2022). Get Your Hands on the Latest Mindanao Literature. Gully Books.

- Shah, S. (2023). AI in cultural preservation: Digitizing heritage – 7 ways technology is saving our history. Yetiai.com.

- TaasNooPilipino. (2016). Mindanao Folklore: Tales of the Sarimanok and Other Legends.

- TaasNooPilipino. (2016). Mindanao folklore: Tales of the Sarimanok and other legends.

- Tadiar, N. , & Villanueva, J. (2017). Philippine Folklores as Cultural Heritage.

- Tehrani, J. E. (2023). The cultural transmission and evolution of folk narratives. In The Oxford Handbook of Cultural Evolution (pp. 411-432). Oxford University Press.

- Yu, A. L. (2022). Cultural motifs in Blaan flalok: Revitalization of oral lore for preservation, development, and sustainability. Southeastern Philippines Journal of Research and Development. [CrossRef]

- Zam398. (2018). Tri-People of Mindanao: Christians, Lumads, and Muslims representing diversity. Steemit.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).