Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Context

1.2. Purpose and Objectives

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- Adults over 65 years old;

- Living in underserved areas of Bucharest;

- Low incomes (pensions under 3000 Lei/month).

- Loneliness (widower, single, divorced);

- Physical deficiencies such as: arthrosis, rheumatism, reduced mobility;

- Mental dysfunctions such as: anxiety, depression, fear of aging, impaired cognitive abilities.

2.3. Measures

- WHOQoL – World Health Organization Quality-of-Life Scale (WHOQOL-BREF)

- CASE-SF - Clinical Assessmenr Scales for the Elderly

- Subjective reports

- Willingness to participate in the yoga course

- Focus groups

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Design and Analysis

- Focus Group Design

- Focus group analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

| M | SD | β | t | p | |

| Age | 73,06 | 5,63 | -,07 | -1,66 | ,105 |

| Anxiety CASE-SF | 38,42 | 10,75 | -,04 | -1,42 | ,164 |

| Depression CASE-SF | 40,86 | 9,88 | -,05 | -1,13 | ,267 |

| Somatization CASE-SF | 38,86 | 9,10 | -,02 | -,36 | ,720 |

| Fear of Aging CASE-SF | 41,21 | 13,36 | ,06 | 1,58 | ,122 |

| Cognition CASE-SF | 44,90 | 13,28 | -,05 | -1,21 | ,232 |

| WHOQOL-BREF | 99,32 | 15,38 | -,04 | -1,92 | ,061 |

| M | SD | β | t | p | |

| Physical diagnosis | 0,12 | 0,33 | 1,65 | 2,73 | ,009 |

| Mental diagnosis | 0,78 | 0,42 | -1,12 | -2,36 | ,023 |

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

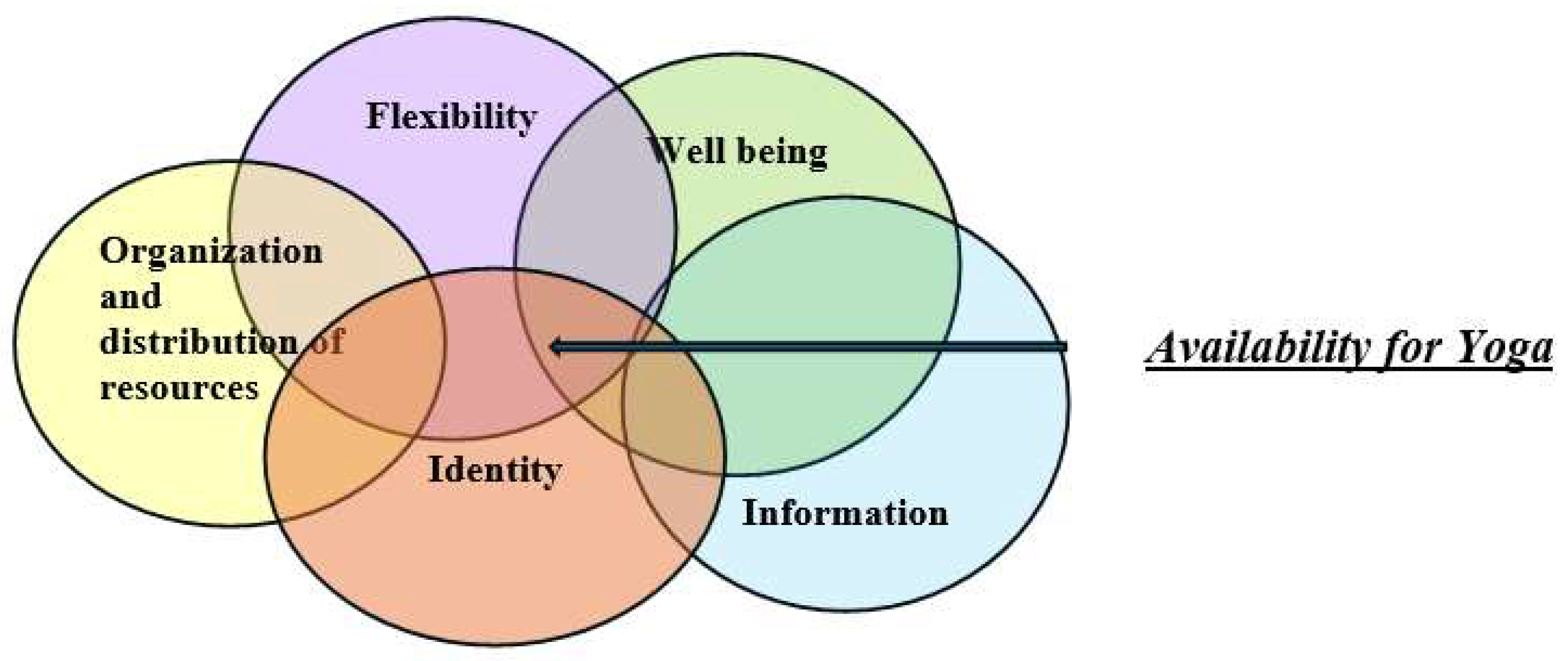

- 1)

- The Health theme includes a series of leit-motifs on three significant levels, namely physical, cognitive and social.

- 2)

- The Information theme contains a series of reasons regarding the roles that information had when potential beneficiaries chose to participate. These roles are both reinforcing willingness to participate and especially blocking.

- 3)

- The Flexibility theme includes the reasons related to certain personality traits with the role of increasing the willingness to participate or cancel this openness.

- 4)

- The Organization and Distribution of Resources theme includes the thematic reasons with a rather negative role on openness to participation.

- 5)

- The theme of Identity refers to those leit-motifs that describe certain attitudes and behaviour arising from personal history.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Structure

"Being several people we communicate, it's different than sitting alone and thinking, you communicate, one says one thing, one says another..." "Socialization, yoga sessions open your horizons a bit and you socialize better... And the brain, you still have contact with one, with another. If you stay locked in a room being old, not having contact with so-and-so, you don't talk to anyone anymore..." "I felt that I entered a community. So it was a matter of emotional compatibility, so I say that the spiritual part also worked a lot for me..." "An inclusion in a community that has maintained and developed beautifully and even supports me in times of trouble…" "Me because I have a tumultuous life, I have friends, I have children, I have children who take special care of me, my life is not static, not "oh, is someone calling me?", it seems to me that it would be the same with socializing…"

"It relaxes the mind, the body, and at our age I think it's very good..." "And for mind, because the body has aged, the mind has also aged, you no longer think like you did when you were young, you used to think seven, now one and you remember after I don't know how long and for memory more would be..." "For the benefit of the memory, I'm sure that the meditations there helped a lot the memory, any meditation helps a lot the memory..." "I think it's good for the health, it balances the psyche and it's also a pleasure after all..."

"I noticed that I felt better, I wasn't so dizzy anymore, I didn't trust my legs anymore, they were shaking. Now these symptoms have started to disappear..." "I think that during these years, it was what balanced me and supported me because I needed something like that and so it was, not only physical, that I always liked to move, so I enjoyed what I did of..." "I was going to work mentally, to understand something from this life that basically we all have, a search and there was also another family..." "I learned a lot from yoga to be observant, to observe yourself, so that was essential in life. There were some life criteria that guided me later..." "It gave me a balance here and this attention to myself and to those around me helped me a lot..." "For me it meant a great awareness, the very first time I realized that I need to be aware of some things both physically and psychologically. Social really meant that too, an inclusion in a community that has maintained and developed beautifully and even supports the times when I'm in trouble..." "I would get up in the morning, do my yoga routine, and suddenly I was a different person. I had energy, I had how to say, power and mental".

"I don't know if my health would allow me. I have problems: with my heart, with my gland, with my liver, if I make ten steps faster, my blood pressure goes up. And then I don't know if I could participate in any classes..." "I might not be able to do certain things and that's the only reason that would stop me..." "I've talked to some people who consider themselves too old, so 72-year-olds who already think they're no longer capable, to do something..." "There are also financial aspects that would impact..." "The lack of correct information. That is, when they see that there are only ads with sexy girls, without... and they don't see people moving either a little more... "

"About yoga, I was left with a bitter taste, why, I received the information that this Mr. Bivolaru was recruiting young people, raping them, forcing them to be there, this was the message I received..." "I remembered that I was talking with a colleague about yoga and the first thing she said was "oh, I'm not going, because it seems like I'm having group sex!". Speaking of Bivolaru. So the world was left with a negative perception..." "If they hear about Bivolaru and you say you do yoga, the world can say - who knows what he did over there, that's why he went - Romanian mentality!... "I heard about yoga when there was that conversation with... Guru, what does he call it..." "In the area where I live, there was Bivolaru, in a tall house with one floor, there were always blinds shot, all the time, people said at the beginning it was prostitution, people said they were making some sexy videos, but no one knew what was going on there..." "I first heard from my children about it, they had a teacher who went at this classes, he liked it, went..."

"It's a matter of laziness and fear to start something..." "For me, for example, it's a necessity. For us, the necessity is in the family, we live in a group, with the grandparents, so basically you allocate your time in what you are actually attracted and of course you feel good too, I mean each of us has this job of doing something for others...I didn't have this and I turned to yoga.. ." "There are some habits, I made my schedule, I drink my coffee, I have to go to the toilet and only after that do I start my schedule at a certain time. So it's those habits we get into that we don't want to get out of..." "I didn't agree with yoga because I personally have a slightly different body than the majority. I have some stuff that doesn't fit the standard. And I focused on religious thinking..." "I am going to parallel and to the church and coming and in yoga, I think I found the meaning more on the other side, and here I found support and balance..."

4.2. Profile of the Optimal Beneficiary

- A single person: divorced, widower, single;

- A person with physical dysfunctions: arthrosis, rheumatism, impaired mobility;

- A person who does not have mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, moderate-major cognitive impairment;

- A person from the urban environment from insufficiently served peripheral areas;

- Older people: over 65 years.

- A person who has an impaired quality of life and/or wishes to increase it;

- A person who has formed a perception and belief about yoga based on correct, undistorted information;

- A person who has received strengthening information about yoga over time from adjacent sources: family, friends, teachers;

- A person who checked his existing stereotypes through an informed check and who did not overgeneralize a negative event;

- A person who presents moderate mental flexibility;

- A person who shows openness to new things;

- A person who focuses on the present;

- A person with a spiritual identity that does oppose to yoga practices.

Authors’ contributions

Data Availability

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CASE-SF | Clinical Assessment Scales for the Elderly |

| GNSPY | Grupul National de Studiu si Practica Yoga |

| NIGG | National Institute of Gerontology and Geriatrics |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WHOQOL-BREF | World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire - Short Form |

References

- Koncz, A.; Nagy, E.; Csala, B.; Körmendi, J.; Gál, V.; Suhaj, C.; Selmeci, C.; Bogdán, Á.S.; Boros, S.; Köteles, F. The effects of a complex yoga-based intervention on healthy psychological functioning. Front Psychol. 2023, 14, 1120992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khalsa, S.S.; Rudrauf, D.; Feinstein, J.S.; Tranel, D. The pathways of interoceptive awareness. NatNeurosci 2009, 12, 1494–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bornemann, B.; Herbert, B.M.; Mehling, W.E.; Singer, T. Differential changes in self-reported aspects of interoceptive awareness through 3 months of contemplative training. Front Psychol 2015, 5, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eurich, T. What self-awareness really is (and how to cultivate it). Harvard Business Review 2018, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pintas, S.; Loewenthal, J.V. Integrating Geriatrics and Lifestyle Medicine: Paving the Path to Healthy Aging. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2024, 15598276241282986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pruitt, J.; Adlin, T. The Persona Lifecycle: Keeping People in Mind Throughout Product Design; Morgan Kaufmann, 2006; ISBN 0–12–566251–3. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A. The Challenges of Intersectionality in the Lives of Older Adults Living in Rural Areas with Limited Financial Resources. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2021, 7, 23337214211009363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustaquim, M.M. A Study of Universal Design in Everyday Life of Elderly Adults. Procedia Computer Science 2015, 67, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinsante, S.; Strazza, A.; Dobre, C.; Bajenaru, L.; Mavromoustakis, C.X.; Batalla, J.M.; Krawiec, P.; Georgescu, G.; Molan, G.; Gonzalez-Velez, H.; Herghelegiu, A.M.; Prada, G.I.; Draghici, R. Integrated Consumer Technologies for Older Adults' Quality of Life Improvement: the vINCI Project. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 23rd International Symposium on Consumer Technologies (ISCT), Ancona, Italy; 2019; pp. 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Băjenaru, L.; Marinescu, I.A.; Dobre, C.; Drăghici, R.; Herghelegiu, A.M.; Rusu, A. Identifying the needs of older people for personalized assistive solutions in Romanian healthcare system. Studies in Informatics and Control 2020, 29, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Steinbüchel, N.; Lischetzke, T.; Gurny, M.; Eid, M. Assessing quality of life in older people: psychometric properties of the WHOQOL-BREF. Eur J Ageing 2006, 3, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Drăghici, R.; Rusu, A.; Prada, G.I.; Herghelegiu, A.M.; Bajenaru, L.; Dobre, C.; Mavromoustakis, C.X.; Spinsante, S.; Batalla, J.M.; Gonzalez-Velez, H. Acceptability of Digital Quality of Life Questionnaire Corroborated with Data from Tracking Devices. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 24th International Workshop on Computer Aided Modeling and Design of Communication Links and Networks (CAMAD), Limassol, Cyprus; 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Băjenaru, L.; Marinescu, I.A.; Tomescu, M.; Drăghici, R. Assessing elderly satisfaction in using smart assisted living technologies: VINCI case study. Romanian Journal of Information Technology and Automatic Control 2022, 32, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.R.; Bigler, E.D. CASE™-SF Clinical Assessment Scales for the Elderly™ Short Form. Available online: https://www.parinc.com/products/CASE-SF.

- Kashdan, T.B.; Rottenberg, J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010, 30, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Perkins, R.; Dassel, K.; Felsted, K.F.; Towsley, G.; Edelman, L. Yoga for seniors: understanding their beliefs and barriers to participation. Educational Gerontology 2020, 46, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertman, A. An Exploration into Pathways, Motivations, Barriers and Experiences of Yoga among Middle-aged and Older Adult, Gerontology Thesis 2013. Available online: https://summit.sfu.ca/person/34989.

- Patel, N.K.; Akkihebbalu, S.; Espinoza, S.E.; Chiodo, L.K. Perceptions of a Community-Based Yoga Intervention for Older Adults. Activities, Adaptation & Aging 2011, 35, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnepf, S.V.; d’Hombres, B.; Mauri, C. Loneliness in Europe. Determinants, Risks and Interventions; Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024; pp. 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Source of data: Kantar Romania. Studiul „Explorarea si masurarea singuratatii la persoanele varstnice din Romania”, Asociatia, Niciodata Singur – Prietenii Varstnicilor”, 27 sept. – 12 oct. 2021.

- Source of data: Eurostat. Overall life satisfaction by sex, age and educational attainmen. [CrossRef]

- Razmjou, E.; Freeman, H.; Vladagina, N.F.; Brems, C. Popular Media Images of Yoga: Limiting Perceived Access to a Beneficial Practice. Media Psychology Review 2017, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Šorytė, R. The Swedish Asylum Case of Gregorian Bivolaru, 2005. The Journal of CESNUR 2022, 6, 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Rottenberg, J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010, 30, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Park, C.L.; Finkelstein-Fox, L.; Groessl, E.J.; Elwy, A.R.; Lee, S.Y. Exploring how different types of yoga change psychological resources and emotional well-being across a single session. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 2020, 49, 102354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).