Submitted:

06 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- (i)

- Improving the quality of life of the subjects through their participation in the yoga sessions, aiming at an increase in the relevant indicators, measured by standardized instruments. The instrument selected was WHOQOL-BREF (World Health Organization Quality-of-Life Scale – Short Form) [51].

- (ii)

- (iii)

- Stimulating the social involvementof the subjects by encouraging them to actively recommend the course, so that each subject recommends the program to other people in the target group. This works in strengthening social and community networks.

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.1.3. Description of Group Participants

- (1)

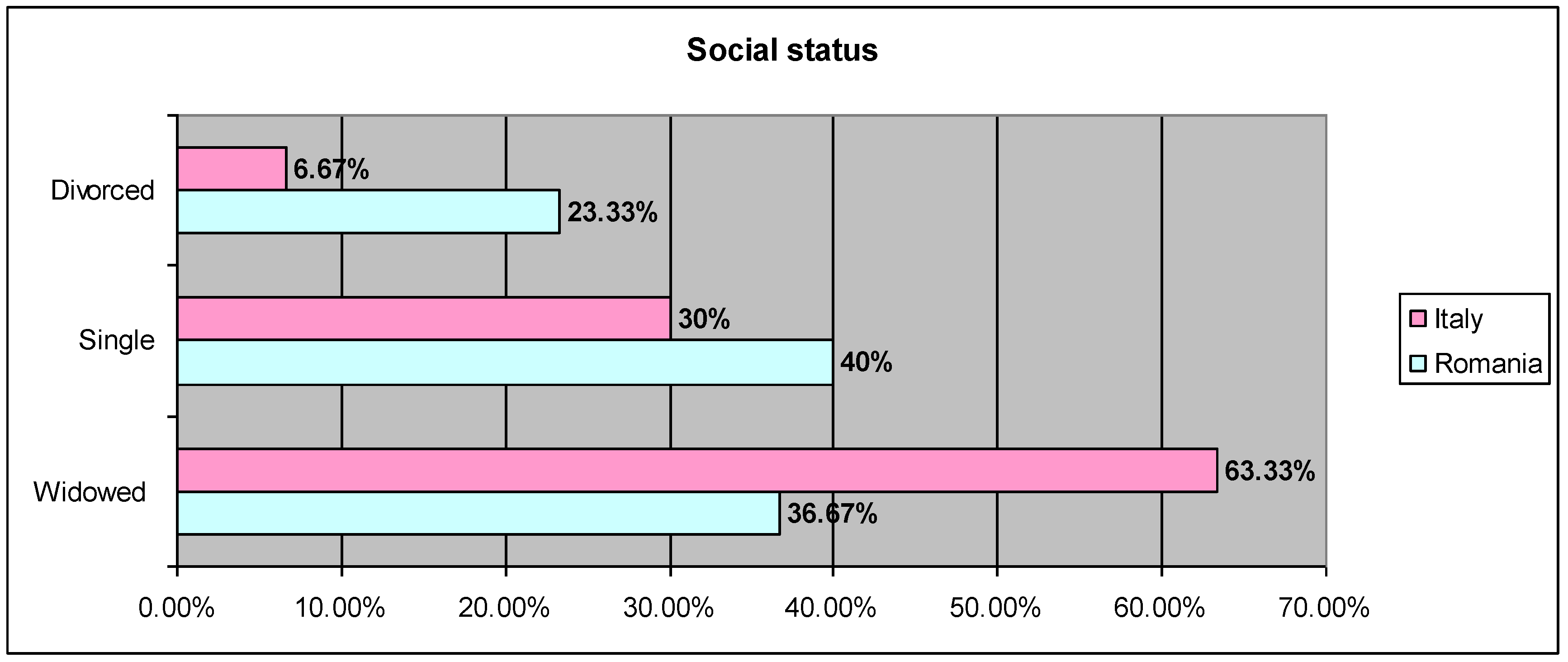

- Social status

- ○

- Romania: 40% single, 23.33% divorced, 36.67% widowed;

- ○

- Italy: 30% single, 6.67% divorced, 63.33% widowed

- (2)

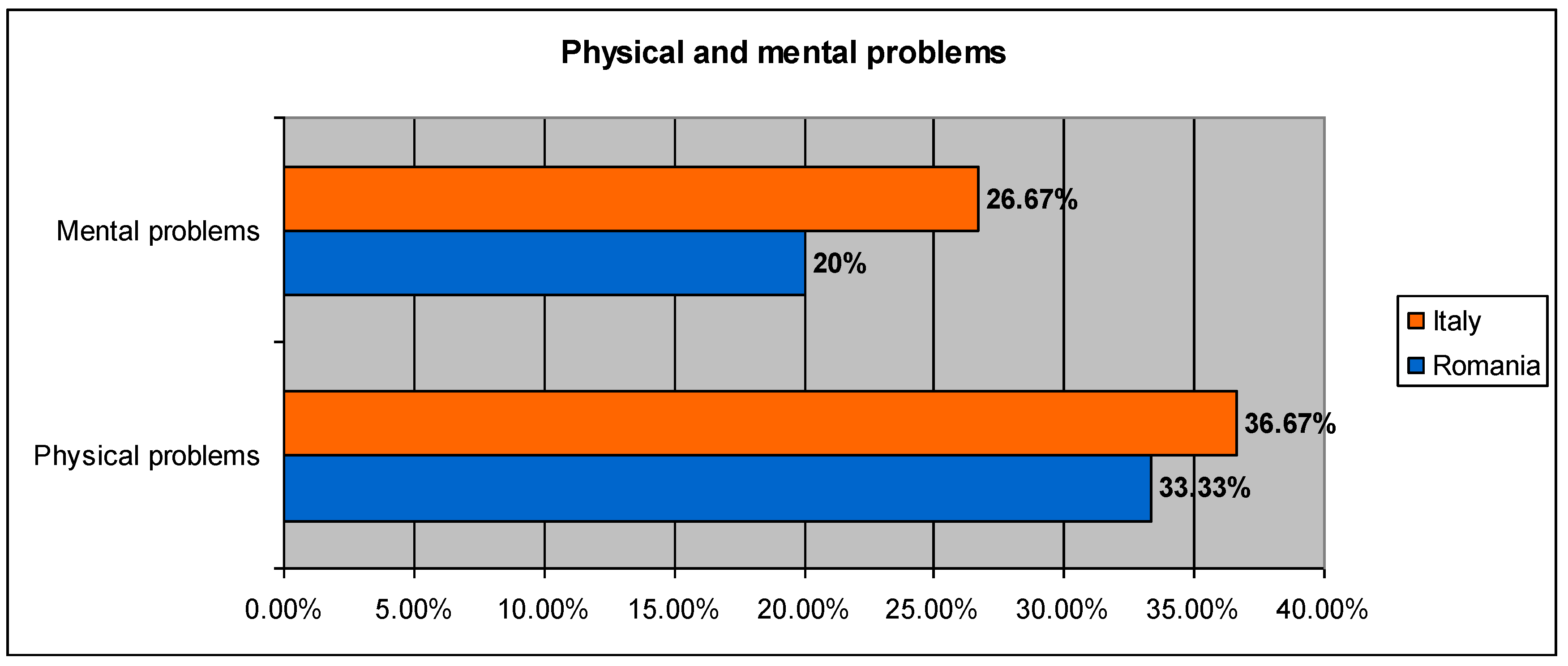

- Physical and mental disorders

- ○

- Romania: 33.33% physical disorders, 20% mental disorders;

- ○

- Italy: 36.67% physical disorders, 26.67% mental disorders;

- (3)

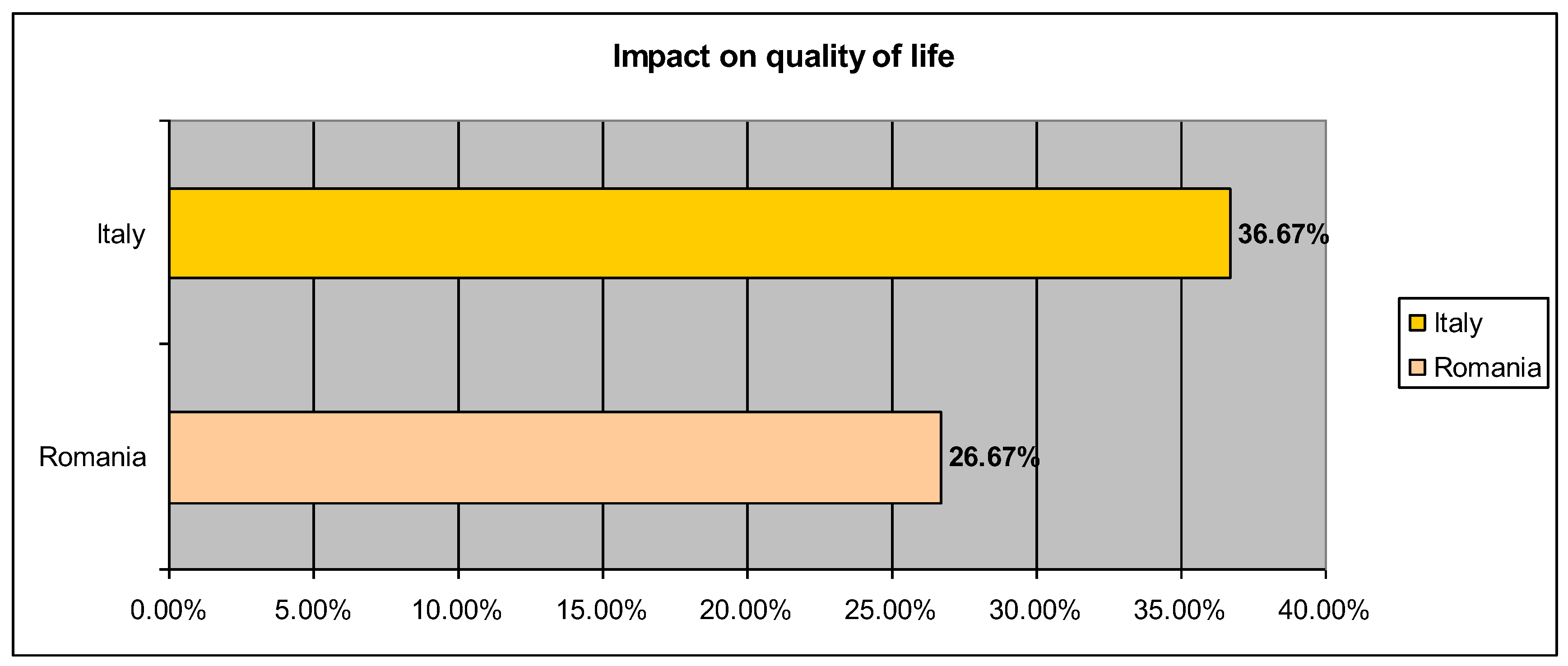

- Quality of life

- ○

- Romania: 26.67% reported lowered quality of life;

- ○

- Italy: 36.67% reported lowered quality of life.

2.1.4. Implementation of the Intervention

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Measures

- WHOQoL-BREF (World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale – Short Form): a self-report questionnaire assesses quality of life from a health-related perspective, including physical, psychological, social and environmental dimensions. A higher score indicates a higher quality of life [51].

- MAIA (Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness) is a self-report questionnaire that analyzes different aspects of interoceptive awareness, such as perception of body sensations, regulation of attention, emotional awareness and self-regulation. The questionnaire includes several items rated on a Likert scale, where higher scores indicate a higher level of interoceptive awareness. MAIA is frequently used in research and in the clinical field to explore the connection between bodily sensations, emotions and well-being [35,36,37,38].

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

- Physical health showed a significant increase between pre and post metrics (t = -6.067, p < 0.001).

- Psychological health showed a significant increase between pre and post metrics (t = -5.574, p <0.001).

- Social relations showed a significant increasebetween pre and post metrics (t = -3.613, p = 0.001).

- The perception of the environment showed a significant increase between pre and post metrics (t = -6.747, p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis

4.2. Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

- The sample size is relatively small, which limits the applicability of the results. Future studies should include a larger number of participants to ensure higher external validity.

- The current study focused on the immediate effects of yoga practice, with a follow up a few months later. Further research is needed to analyze whether the improvements recorded persist over longer periods of time.

- Though differences in Romanian and Italian results were analyzed and potential reasons were given, the study did not attempt to explore in depth how socio-economic and cultural differences influence the adoption and maintenance of yoga practice. Participants from Romania and Italy had different reactions, suggesting the need for personalized approaches.

- The study did not include a control group that would allow for the comparison of the effects of yoga with other types of interventions. This aspect limits the possibility of establishing with assurance that all positive effects are due exclusively to yoga practice.

- Motivational factors influencing program participation and post-study retention have not been examined in detail. Understanding these factors could contribute to the creation of more effective and sustainable programs.

- Although the results indicate improvements on psychological and emotional levels, the effect of yoga on cognitive functions, such as memory, attention, and mental flexibility, has not been specifically investigated. This could be an important area for future research.

- Future research should include examining the long-term effects of yoga practice, comparing the impact of different types of yoga on different age groups and specific needs, and investigating the impact on cognitive ability and long-term stress management.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA-NIGG | “Ana Aslan” National Institute of Gerontology and Geriatrics |

| SYI | Sarva Yoga International |

| GNSPY | Grupul National de Studiu si Practica Yoga |

| WHOQOL-BREF | World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire-Short Form |

| MAIA | Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness |

References

- Eurostat. (2024). Population structure and ageing. Statistics Explained. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Population_structure_and_ageing (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Sanchini, V., Sala, R., & Gastmans, C. (2022). The concept of vulnerability in aged care: A systematic review of argument-based ethics literature. BMC Medical Ethics, 23(84). [CrossRef]

- Noto, S. (2023). Perspectives on aging and quality of life. Healthcare, 11(15), 2131. [CrossRef]

- Gopalraj, R. (2017). The older adult with diabetes and the busy clinicians. Primary Care, 44(3), 469–479. [CrossRef]

- Cleeland, C., Pipingas, A., Scholey, A., & White, D. (2019). Neurochemical changes in the aging brain: A systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 98, 306–319. [CrossRef]

- Arden, N., & Nevitt, M. C. (2006). Osteoarthritis: Epidemiology. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 20, 3–25. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R. C., Felson, D. T., Helmick, C. G., et al. (2008). Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: Part II. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 58, 26–35. [CrossRef]

- Noale, M., Limongi, F., & Maggi, S. (2020). Epidemiology of cardiovascular diseases in the elderly. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology (Vol. 1216, pp. 29–38). [CrossRef]

- Maringka, M. C. G., Rahardjo, T. B. W., & Suratmi, T. (2023). Quality of elderly life with chronic diseases in the working area of Kembangan District Hospital. Jurnal Indonesia Sosial Sains, 4(10), 1048–1057. [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, A., Şimşek, T. T., Yümin, E. T., Sertel, M., & Yümin, M. (2011). The relationship between physical, functional capacity and quality of life (QoL) among elderly people with a chronic disease. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 53(3), 278–283. [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S. T., Emanuel, J., Albert, S. M., Dew, M. A., Schulz, R., Robbins-Welty, G., & Reynolds, C. F. III. (2017). Design and rationale for a technology-based healthy lifestyle intervention in older adults grieving the loss of a spouse. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications, 8, 99–105. [CrossRef]

- Haslam, C., Lam, B. C. P., Ghafoori, E., Steffens, N. K., Haslam, S. A., Bentley, S. V., Cruwys, T., & La Rue, C. J. (2023). A longitudinal examination of the role of social identity in supporting health and well-being in retirement. Psychology and Aging, 38(7), 615–626. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, O., Teixeira, L., Araújo, L., Rodríguez-Blázquez, C., Calderón-Larrañaga, A., & Forjaz, M. J. (2020). Anxiety, depression and quality of life in older adults: Trajectories of influence across age. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9039). [CrossRef]

- Bodner, E., & Bergman, Y. S. (2016). Loneliness and depressive symptoms among older adults: The moderating role of subjective life expectancy. Psychiatry Research, 237, 78–82. [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. F. (2012). Experiencing meaning in life: Optimal functioning at the nexus of well-being, psychopathology, and spirituality. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 165–184). Routledge. https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2656062.

- Greenblatt-Kimron, L., Kagan, M., & Zychlinski, E. (2022). Meaning in life among older adults: An integrative model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16762. [CrossRef]

- Martela, F., & Steger, M. F. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11, 531–545. [CrossRef]

- King, L. A., Hicks, J. A., Krull, J. L., & Del Gaiso, A. K. (2006). Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(1), 179–196. [CrossRef]

- Bergman, Y. S., & Segel-Karpas, D. (2018). Future time perspective, loneliness, and depressive symptoms among middle-aged adults: A mediation model. Journal of Affective Disorders, 241, 173–175. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S., Malviya, S. J., Pant, H., & Kushwaha, E. P. (2022). A review on yoga practice and its effects. In Challenges and Opportunities in Nutrition, Environment and Agriculture. Rathore Academic Research Publication. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355409364_Therapeutic_role_of_yoga_in_neuropsychological_disorders.

- Rao, R. V. (2019). Yoga practice and health among older adults. În D. Gu & M. E. Dupre (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging (pp. XX–XX). Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Telles, S., & Singh, N. (2013). Science of the mind: Ancient yoga texts and modern studies. Psychi-atric Clinics, 36(1), 93–108. [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, S., & Achchi, K. (2015). A study on the significance of yoga in geriatric care. International Journal of Applied Research, 1(7), 749–751. https://www.allresearchjournal.com/archives/2015/vol1issue7/PartM/1-7-124-125.pdf.

- Martens, N. L. (2022). Yoga interventions involving older adults: Integrative review. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 48(2), 43–52. [CrossRef]

- de Barros, D. S., Bazzaz, S., Gheith, M. E., Siam, G. A., & Moster, M. R. (2008). Progressive optic neuropathy in congenital glaucoma associated with the Sirsasana yoga posture. Ophthalmic Surgery, Lasers and Imaging, 39, 339–340. [CrossRef]

- Cramer, H., Quinker, D., Schumann, D., Wardle, J., Dobos, G., & Lauche, R. (2019). Adverse effects of yoga: A national cross-sectional survey. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 19, Article 190. [CrossRef]

- Staudt, M. D., Prabhala, T., Sheldon, B. L., Quaranta, N., Zakher, M., Bhullar, R., Pilitsis, J. G., & Argoff, C. E. (2020). Current strategies for the management of painful diabetic neuropathy. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. [CrossRef]

- Bonura, K. B. (2011). The psychological benefits of yoga practice for older adults: Evidence and guidelines. International Journal of Yoga Therapy, 21, 129–142. PMID: 22398354 . [CrossRef]

- Veneri, D., & Gannoti, M. E. (2021). Take a seat for yoga with seniors: A scoping review. OBM Geriatrics, 6(2), Article 197. [CrossRef]

- Roche, L., & Hesse, B. (2014). Application of an integrative yoga therapy program in cases of essential arterial hypertension in public healthcare. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 20(4), 285–290. [CrossRef]

- Galantino, M. L., Green, L., Decesari, J. A., Mackain, N. A., Rinaldi, S. M., Stevens, M. E., et al. (2012). Safety and feasibility of modified chair-yoga on functional outcome among elderly at risk for falls. International Journal of Yoga, 5(2), 146–150. [CrossRef]

- Gothe, N. P., Kramer, A. F., & McAuley, E. (2014). The effects of an 8-week Hatha yoga intervention on executive function in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 69(9), 1109–1116. [CrossRef]

- Farhang, M., Rojas, G., Martínez, P., Behrens, M. I., Langer, Á. I., Diaz, M., & Miranda-Castillo, C. (2022). The impact of a yoga-based mindfulness intervention versus psycho-educational session for older adults with mild cognitive impairment: The protocol of a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15374. [CrossRef]

- Berlingieri, F., Colagrossi, M., & Mauri, C. (2023). Loneliness and social connectedness: Insights from a new EU-wide survey. European Commission. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC133351.

- Casabianca, E., & Kovacic, M. (2022). Loneliness among older adults – A European perspective. European Commission. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC129421.

- Panigrahi, M., Shree, P., & Swain, D. P. (2023). Effect of integrated approach of yoga therapy on loneliness in elderly: An interventional study. Biomedicine, 43(1), 47–51. [CrossRef]

- Tulloch, A., Bombell, H., Dean, C., & Tiedemann, A. (2018). Yoga-based exercise improves health-related quality of life and mental well-being in older people: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Age and Ageing, 47(4), 537–544. [CrossRef]

- Suksasilp, C., & Garfinkel, S. N. (2022). Towards a comprehensive assessment of interoception in a multi-dimensional framework. Biological Psychology, 168, Article 108262. [CrossRef]

- Tsakiris, M., & Critchley, H. (2016). Interoception beyond homeostasis: Affect, cognition and mental health. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371(1708), 20160002. [CrossRef]

- Monti, A., Porciello, G., Panasiti, M. S., & Aglioti, S. M. (2022). The inside of me: Interoceptive constraints on the concept of self in neuroscience and clinical psychology. Psychological Research, 86(8), 2468–2477. [CrossRef]

- Füstös, J., Gramann, K., Herbert, B. M., & Pollatos, O. (2013). On the embodiment of emotion regulation: Interoceptive awareness facilitates reappraisal. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8(8), 911–917. [CrossRef]

- Khalsa, S. S., Rudrauf, D., & Tranel, D. (2009). Interoceptive awareness declines with age. Psychophysiology, 46(6), 1130–1136. [CrossRef]

- Pollatos, O., Matthias, E., & Keller, J. (2015). When interoception helps to overcome negative feelings caused by social exclusion. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, Article 786. [CrossRef]

- Beier, M. E., & Ackerman, P. L. (2005). Age, ability, and the role of prior knowledge on the acquisition of new domain knowledge: Promising results in a real-world learning environment. Psychology and Aging, 20(2), 341–355. [CrossRef]

- Tournier, I. (2022). Learning and adaptation in older adults: An overview of main methods and theories. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 37, Article 100466. [CrossRef]

- Gooijers, J., Pauwels, L., Hehl, M., Seer, C., Cuypers, K., & Swinnen, S. P. (2024). Aging, brain plasticity, and motor learning. Ageing Research Reviews, 102, Article 102569. [CrossRef]

- Durand-Ruel, M., Park, C.-h., Moyne, M., Maceira-Elvira, P., Morishita, T., & Hummel, F. C. (2023). Early motor skill acquisition in healthy older adults: Brain correlates of the learning process. Cerebral Cortex, 33(12), 7356–7368. [CrossRef]

- Voelcker-Rehage, C. (2008). Motor-skill learning in older adults—A review of studies on age-related differences. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity, 5, 5–16. [CrossRef]

- Bălan, D.-C., Drăghici, R., Găiculescu, I., Rusu, A., Stan, A.-E., & Stan, P. (2025). An optimal beneficiary profile to ensure focused interventions for older adults. Geriatrics, 10, Article 59. [CrossRef]

- Eurich, T. (2018). What self-awareness really is (and how to cultivate it). Harvard Business Review, 4(4), 1–9.https://membership.amavic.com.au/files/What%20self-awareness%20is%20and%20how%20to%20cultivate%20it_HBR_2018.pdf.

- von Steinbüchel, N., Lischetzke, T., Gurny, M., & Eid, M. (2006). Assessing quality of life in older people: Psychometric properties of the WHOQOL-BREF. European Journal of Ageing, 3(2), 116–122. [CrossRef]

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | Variance | |

| PreD1_Physical Health | 60 | 17.86 | 89.29 | 54.95 | 13.90 | 193.214 |

| PreD2_Psychological Health | 60 | 17.50 | 95.00 | 57.04 | 18.97 | 360.071 |

| PreD3_Social Relations | 60 | 16.67 | 100.00 | 65.06 | 17.55 | 308.148 |

| PreD4_Environment | 60 | 17.75 | 100.00 | 59.67 | 15.209 | 231.328 |

| PostD1_ Physical Health | 60 | 42.86 | 86.75 | 65.36 | 10.64 | 113.231 |

| PostD2_Psychological Health | 60 | 31.75 | 98.25 | 66.60 | 14.369 | 206.487 |

| PostD3_ Social Relations | 60 | 33.33 | 100.00 | 72.57 | 14.76 | 217.957 |

| PostD4_Environment | 60 | 37.50 | 97.92 | 75.97 | 14.426 | 208.134 |

| Follow-upD1_Physical Health | 60 | 17.86 | 100.00 | 62.29 | 15.040 | 226.229 |

| Follow-upD2_Psychological Health | 60 | 8.33 | 95.75 | 64.719 | 19.683 | 387.452 |

| Follow-upD3_Social Relations | 60 | 8.33 | 100.00 | 66.14 | 19.628 | 385.293 |

| Follow-upD4_Environment | 60 | 12.50 | 96.50 | 64.03 | 17.723 | 314.117 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 60 |

| Paired Differences | t | df |

Sig. (2-tailed) |

||||

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | |||||

| Pair 1 | PreD1_PhysicalHealth& PostD1_ PhysicalHealth |

-10.409 | 13.289 | 1.715 | -6.067 | 59 | 0.000 |

| Pair 2 | PostD1_PhysicalHealth& Follow-upD1_PhysicalHealth |

3.067 | 13.798 | 1.781 | 1.722 | 59 | 0.090 |

| Pair 3 | PreD1_PhysicalHealth& Follow-upD1_PhysicalHealth |

-7.342 | 18.774 | 2.423 | -3.029 | 59 | 0.004 |

| Pair 4 | PreD2_PsychologicalHealth& PostD2_PsychologicalHealth |

-9.565 | 13.291 | 1.715 | -5.574 | 59 | 0.000 |

| Pair 5 | PostD2_PsychologicalHealth& Follow-upD2_PsychologicalHealth |

1.886 | 19.237 | 2.483 | 0.759 | 59 | 0.451 |

| Pair 6 | PreD2_PsychologicalHealth& Follow-upD2_PsychologicalHealth |

-7.679 | 19.855 | 2.563 | -2.996 | 59 | 0.004 |

| Pair 7 | PreD3_SocialRelations& PostD3_ SocialRelations |

-7.508 | 16.098 | 2.078 | -3.613 | 59 | 0.001 |

| Pair 8 | PostD3_SocialRelations& Follow-upD3_SocialRelations |

6.429 | 18.946 | 2.446 | 2.628 | 59 | 0.011 |

| Pair 9 | PreD3_SocialRelations& Follow-upD3_SocialRelations |

-1.079 | 20.908 | 2.699 | -0.400 | 59 | 0.691 |

| Pair 10 | PreD4_Environment& PostD4_Environment |

-16.300 | 18.713 | 2.415 | -6.747 | 59 | 0.000 |

| Pair 11 | PostD4_Environment& Follow-upD4_Environment |

11.940 | 23.826 | 3.075 | 3.882 | 59 | 0.000 |

| Pair 12 | PreD4_Environment& Follow-upD4_Environment |

-4.359 | 16.895 | 2.181 | -1.999 | 59 | 0.050 |

| Paired Samples Correlations | ||||

| N | Correlation | Sig. | ||

| Pair 1 | PreD1_ PhysicalHealth& PostD1_ PhysicalHealth |

60 | 0.439 | 0.000 |

| Pair 2 | PostD1_PhysicalHealth& Follow-upD1_ PhysicalHealth |

60 | 0.466 | 0.000 |

| Pair 3 | PreD1_PhysicalHealth& Follow-upD1_ PhysicalHealth |

60 | 0.160 | 0.222 |

| Pair 4 | PreD2_PsychologicalHealth& PostD2_ PsychologicalHealth | 60 | 0.715 | 0.000 |

| Pair 5 | PostD2_PsychologicalHealth& Follow-upD2_PsychologicalHealth | 60 | 0.396 | 0.002 |

| Pair 6 | PreD2_PsychologicalHealth& Follow-upD2_ PsychologicalHealth | 60 | 0.473 | 0.000 |

| Pair 7 | PreD3_ SocialRelations& PostD3_ SocialRelations |

60 | 0.515 | 0.000 |

| Pair 8 | PostD3_SocialRelations& Follow-upD3_ SocialRelations |

60 | 0.421 | 0.001 |

| Pair 9 | PreD3_SocialRelations& Follow-upD3_ SocialRelations |

60 | 0.372 | 0.003 |

| Pair 10 | PreD4_Environment& PostD4_Environment |

60 | 0.203 | 0.119 |

| Pair 11 | PostD4_Environment& Follow-upD4_Environment |

60 | -0.089 | 0.500 |

| Pair 12 | PreD4_Environment& Follow-upD4_Environment |

60 | 0.482 | 0.000 |

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | Variance | |

| Pre_Noticing | 60 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 3.427 | 1.148 | 1.319 |

| Pre_NotDistracting | 60 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 2.202 | 1.093 | 1.196 |

| Pre_NotWorrying | 60 | 0.00 | 4.80 | 2.469 | 1.29 | 1.669 |

| Pre_AttentionRegulation | 60 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.158 | 1.052 | 1.108 |

| Pre_EmotionalAwareness | 60 | 1.67 | 5.00 | 3.401 | 1.094 | 1.197 |

| Pre_SelfRegulation | 60 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.959 | 1.180 | 1.393 |

| Pre_BodyListening | 60 | 0.33 | 5.00 | 2.877 | 1.221 | 1.492 |

| Pre_Trusting | 60 | 0.40 | 5.00 | 3.170 | 1.440 | 2.074 |

| Post_Noticing | 60 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.704 | 1.048 | 1.098 |

| Post_NotDistracting | 60 | 0.00 | 4.67 | 1.764 | 1.014 | 1.029 |

| Post_NotWorrying | 60 | 0.40 | 4.80 | 2.503 | 0.957 | 0.916 |

| Post_AttentionRegulation | 60 | 1.00 | 4.86 | 3.009 | 1.052 | 1.107 |

| Post_EmotionalAwareness | 60 | 2.20 | 5.00 | 3.923 | 0.834 | 0.697 |

| Post_SelfRegulation | 60 | 0.75 | 5.00 | 3.501 | 1.107 | 1.227 |

| Post_BodyListening | 60 | 0.67 | 5.00 | 3.255 | 1.153 | 1.331 |

| Post_Trusting | 60 | 1.33 | 5.00 | 3.794 | 0.959 | 0.920 |

| Follow-up_Noticing | 60 | 1.50 | 5.00 | 3.879 | 0.937 | 0.878 |

| Follow-up_NotDistracting | 60 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 1.933 | 1.09 | 1.197 |

| Follow-up_NotWorrying | 60 | 0.60 | 4.80 | 2.606 | 0.952 | 0.907 |

| Follow-up_AttentionRegulation | 60 | 0.29 | 5.00 | 3.143 | 1.137 | 1.293 |

| Follow-up_EmotionalAwareness | 60 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 4.076 | 0.930 | 0.867 |

| Follow-up_SelfRegulation | 60 | 0.25 | 5.00 | 3.583 | 1.131 | 1.281 |

| Follow-up_BodyListening | 60 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 3.394 | 1.127 | 1.272 |

| Follow-up_Trusting | 60 | 0.67 | 5.00 | 3.861 | 0.993 | 0.988 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 60 |

| Paired Differences | t | df |

Sig. (2-tailed) |

||||

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | |||||

| Pair 1 | Pre_Noticing& Post_Noticing |

-0.276 | 0.996 | 0.128 | -2.150 | 59 | 0.036 |

| Pair 2 | Post_Noticing& Follow-up_Noticing |

-0.175 | 0.930 | 0.120 | -1.457 | 59 | 0.150 |

| Pair 3 | Pre_Noticing& Follow-up_Noticing |

-0.451 | 0.937 | 0.120 | -3.732 | 59 | 0.000 |

| Pair 4 | Pre_NotDistracting& Post_NotDistracting | 0.438 | 1.330 | 0.171 | 2.553 | 59 | 0.013 |

| Pair 5 | Post_NotDistracting& Follow-up_NotDistracting |

-0.169 | 1.025 | 0.132 | -1.277 | 59 | 0.207 |

| Pair 6 | Pre_NotDistracting& Follow-up_NotDistracting |

0.269 | 1.272 | 0.164 | 1.641 | 59 | 0.106 |

| Pair 7 | Pre_NotWorrying& Post_NotWorrying | -0.033 | 1.333 | 0.172 | -0.195 | 59 | 0.846 |

| Pair 8 | Post_NotWorrying& Follow-up_NotWorrying |

-0.103 | 0.861 | 0.111 | -0.929 | 59 | 0.357 |

| Pair 9 | Pre_NotWorrying& Follow-up_NotWorrying |

-0.136 | 1.222 | 0.157 | -0.867 | 59 | 0.389 |

| Pair 10 | Pre_AttentionRegulation& Post_AttentionRegulation | 0.148 | 1.095 | 0.141 | 1.048 | 59 | 0.299 |

| Pair 11 | Post_AttentionRegulation& Follow-up_AttentionRegulation |

-0.133 | 0.961 | 0.124 | -1.073 | 59 | 0.288 |

| Pair 12 | Pre_AttentionRegulation& Follow-up_AttentionRegulation |

0.015 | 0.957 | 0.123 | 0.121 | 59 | 0.904 |

| Pair 13 | Pre_EmotionalAwareness& Post_EmotionalAwareness | -0.521 | 1.170 | 0.151 | -3.451 | 59 | 0.001 |

| Pair 14 | Post_EmotionalAwareness& Follow-up_EmotionalAwareness |

-0.153 | 0.930 | 0.120 | -1.277 | 59 | 0.207 |

| Pair 15 | Pre_EmotionalAwareness& Follow-up_EmotionalAwareness |

-0.675 | 1.129 | 0.145 | -4.629 | 59 | 0.000 |

| Pair 16 | Pre_SelfRegulation& Post_SelfRegulation | -0.541 | 1.272 | 0.164 | -3.296 | 59 | 0.002 |

| Pair 17 | Post_SelfRegulation& Follow-up_SelfRegulation |

-0.082 | 1.061 | 0.136 | -0.600 | 59 | 0.551 |

| Pair 18 | Pre_SelfRegulation& Follow-up_SelfRegulation |

-0.623 | 1.176 | 0.151 | -4.107 | 59 | 0.000 |

| Pair 19 | Pre_BodyListening& Post_BodyListening | -0.377 | 1.245 | 0.160 | -2.350 | 59 | 0.022 |

| Pair 20 | Post_BodyListening& Follow-up_BodyListening |

-0.138 | 1.192 | 0.153 | -0.901 | 59 | 0.371 |

| Pair 21 | Pre_BodyListening& Follow-up_BodyListening |

-0.516 | 1.131 | 0.146 | -3.536 | 59 | 0.001 |

| Pair 22 | Pre_Trusting& Post_Trusting |

-0.623 | 1.421 | 0.183 | -3.397 | 59 | 0.001 |

| Pair 23 | Post_Trusting& Follow-up_Trusting |

-0.067 | 1.114 | 0.143 | -0.467 | 59 | 0.642 |

| Pair 24 | Pre_Trusting& Follow-up_Trusting |

-0.690 | 1.156 | 0.149 | -4.625 | 59 | 0.000 |

| Paired Samples Correlations | ||||

| N | Correlation | Sig. | ||

| Pair 1 | Pre_Noticing& Post_Noticing |

60 | 0.592 | 0.000 |

| Pair 2 | Post_Noticing& Follow-up_Noticing |

60 | 0.566 | 0.000 |

| Pair 3 | Pre_Noticing& Follow-up_Noticing |

60 | 0.613 | 0.000 |

| Pair 4 | Pre_NotDistracting& Post_NotDistracting | 60 | 0.205 | 0.117 |

| Pair 5 | Post_NotDistracting& Follow-up_NotDistracting |

60 | 0.529 | 0.000 |

| Pair 6 | Pre_NotDistracting& Follow-up_NotDistracting |

60 | 0.323 | 0.012 |

| Pair 7 | Pre_NotWorrying& Post_NotWorrying | 60 | 0.326 | 0.011 |

| Pair 8 | Post_NotWorrying& Follow-up_NotWorrying |

60 | 0.593 | 0.000 |

| Pair 9 | Pre_NotWorrying& Follow-up_NotWorrying |

60 | 0.440 | 0.000 |

| Pair 10 | Pre_AttentionRegulation& Post_AttentionRegulation | 60 | 0.459 | 0.000 |

| Pair 11 | Post_AttentionRegulation& Follow-up_AttentionRegulation |

60 | 0.617 | 0.000 |

| Pair 12 | Pre_AttentionRegulation& Follow-up_AttentionRegulation |

60 | 0.620 | 0.000 |

| Pair 13 | Pre_EmotionalAwareness& Post_EmotionalAwareness | 60 | 0.286 | 0.027 |

| Pair 14 | Post_EmotionalAwareness& Follow-up_EmotionalAwareness |

60 | 0.449 | 0.000 |

| Pair 15 | Pre_EmotionalAwareness& Follow-up_EmotionalAwareness |

60 | 0.387 | 0.002 |

| Pair 16 | Pre_SelfRegulation& Post_SelfRegulation | 60 | 0.382 | 0.003 |

| Pair 17 | Post_SelfRegulation& Follow-up_SelfRegulation |

60 | 0.551 | 0.000 |

| Pair 18 | Pre_SelfRegulation& Follow-up_SelfRegulation |

60 | 0.483 | 0.000 |

| Pair 19 | Pre_BodyListening& Post_BodyListening | 60 | 0.452 | 0.000 |

| Pair 20 | Post_BodyListening& Follow-up_BodyListening |

60 | 0.454 | 0.000 |

| Pair 21 | Pre_BodyListening& Follow-up_BodyListening |

60 | 0.539 | 0.000 |

| Pair 22 | Pre_Trusting& Post_Trusting |

60 | 0.352 | 0.006 |

| Pair 23 | Post_Trusting& Follow-up_Trusting |

60 | 0.349 | 0.006 |

| Pair 24 | Pre_Trusting& Follow-up_Trusting |

60 | 0.602 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).