Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

29 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical statement

2.2. Study design

2.3. Cell culture and treatment

2.4. Statistical analysis

3. Results

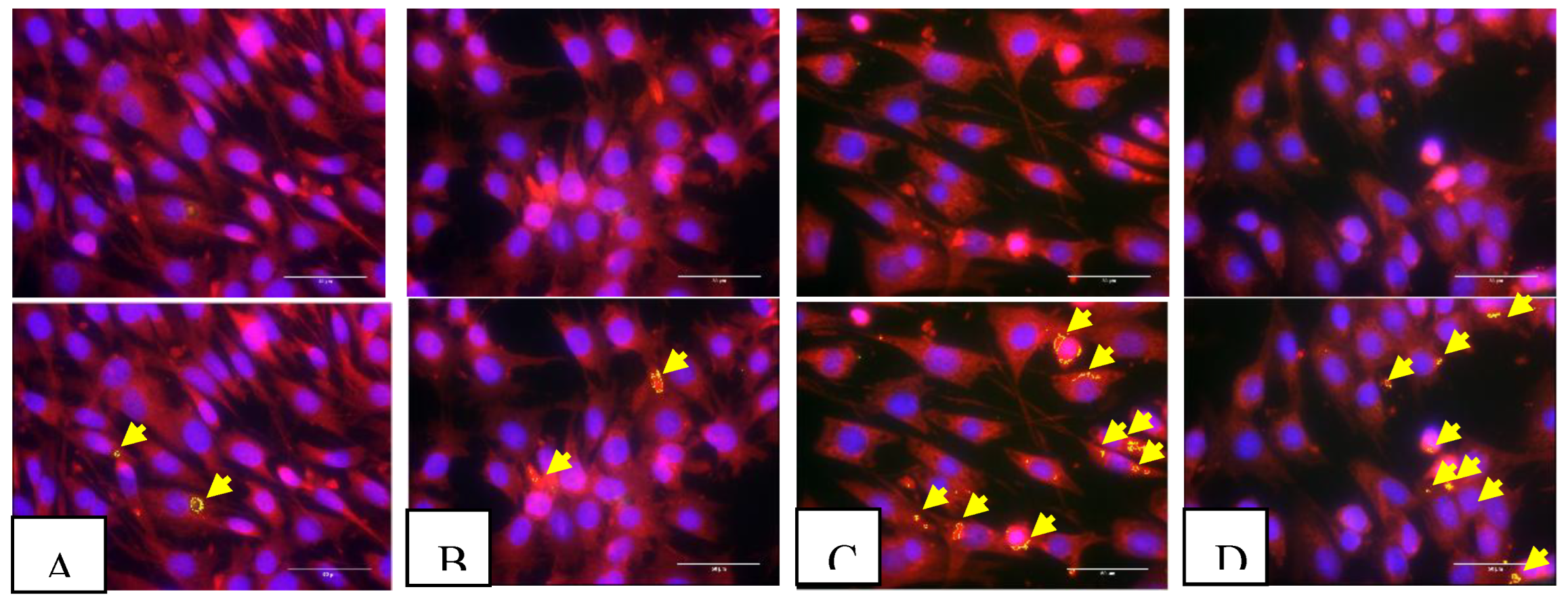

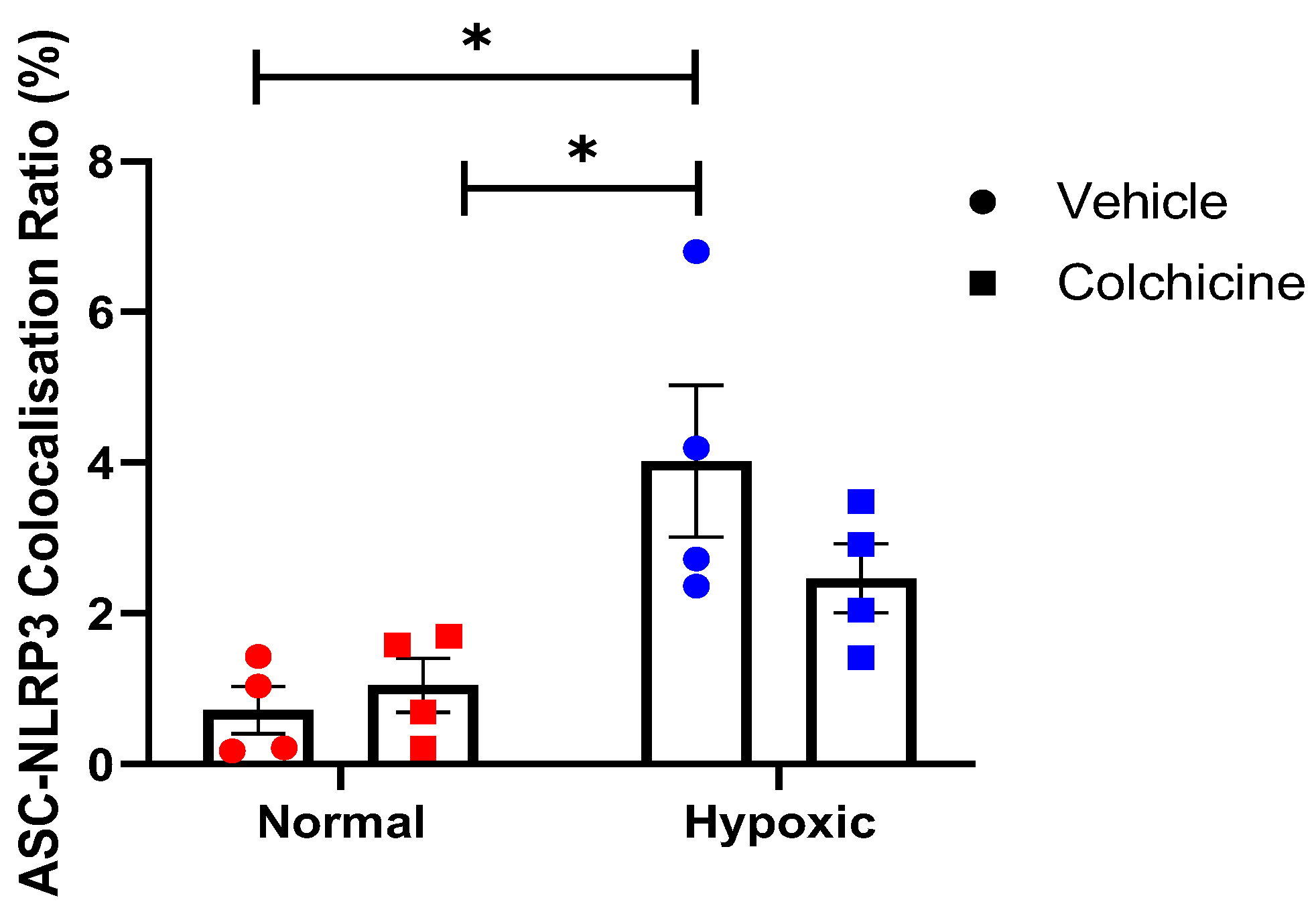

3.1. NLRP3 Inflammasome

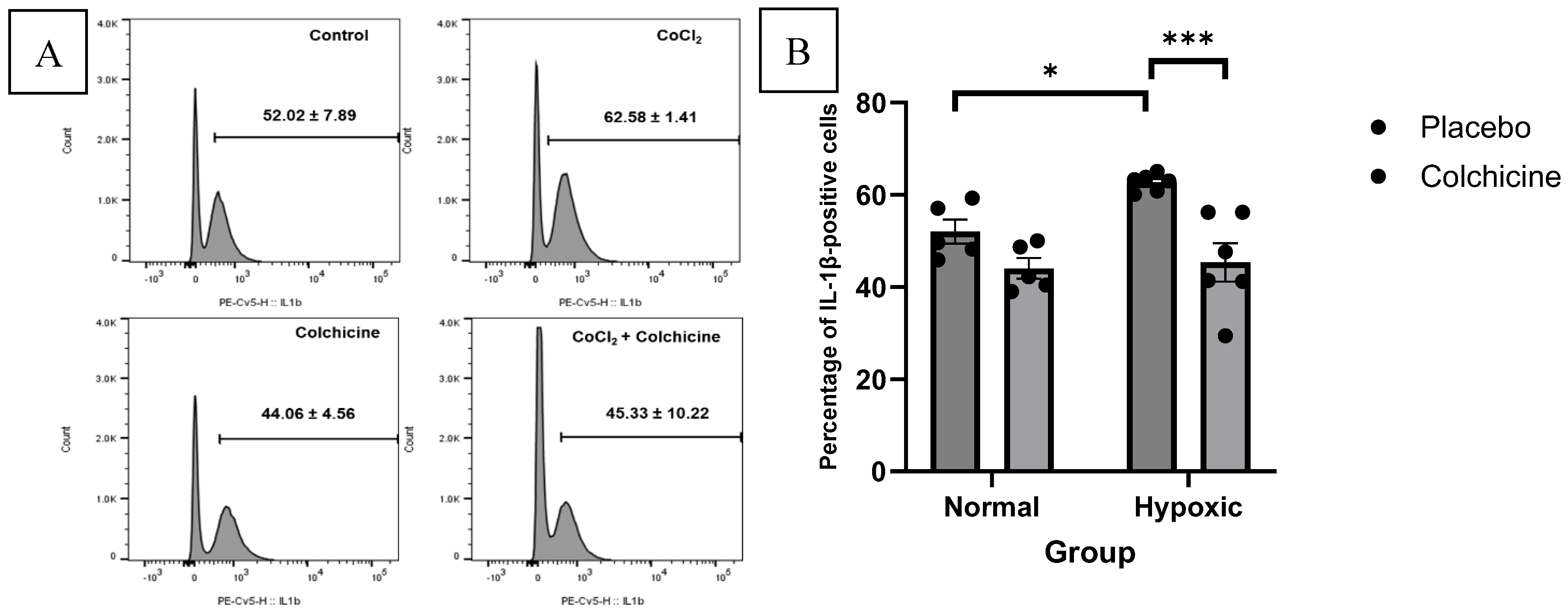

3.2. IL-1β Expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMI | acute myocardial infarction |

| ASC | caspase recruitment domain |

| CVDs | cardiovascular diseases |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| COLCOT | Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial |

| ECACC | European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures |

| HIF-1α | hypoxia-inducible factor 1α |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like receptor protein 3 |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| STR | short tandem repeat |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor-β |

References

- Zhao D (2021) Epidemiological Features of Cardiovascular Disease in Asia. JACC Asia 1:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Heusch G (2022) Coronary blood flow in heart failure: cause, consequence and bystander. Basic Res Cardiol 117:1. [CrossRef]

- Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, et al (2020) Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019. J Am Coll Cardiol 76:2982–3021. [CrossRef]

- Galli A, Lombardi F (2016) Postinfarct Left Ventricular Remodelling: A Prevailing Cause of Heart Failure. Cardiol Res Pract 2016:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Choe JC, Cha KS, Yun EY, et al (2018) Reverse Left Ventricular Remodelling in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Incidence, Predictors, and Impact on Outcome. Heart Lung Circ 27:154–164. [CrossRef]

- Bartekova M, Radosinska J, Jelemensky M, Dhalla NS (2018) Role of cytokines and inflammation in heart function during health and disease. Heart Fail Rev 23:733–758. [CrossRef]

- Amin MN, Siddiqui SA, Ibrahim M, et al (2020) Inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and cancer. SAGE Open Med 8:205031212096575. [CrossRef]

- Gourdin MJ, Bree B, De Kock M (2009) The impact of ischaemia–reperfusion on the blood vessel: Eur J Anaesthesiol 26:537–547. [CrossRef]

- Frangogiannis NG (2014) The inflammatory response in myocardial injury, repair, and remodelling. Nat Rev Cardiol 11:255–265. [CrossRef]

- Fang, L, Moore, X, Dart, A.M, Wang, L (2015) Systemic inflammatory response following acute myocardial infarction. Journal of Geriatric Cardiology 12:305−312.

- Napodano C, Carnazzo V, Basile V, et al (2023) NLRP3 Inflammasome Involvement in Heart, Liver, and Lung Diseases—A Lesson from Cytokine Storm Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci 24:16556. [CrossRef]

- Abderrazak A, Syrovets T, Couchie D, et al (2015) NLRP3 inflammasome: From a danger signal sensor to a regulatory node of oxidative stress and inflammatory diseases. Redox Biol 4:296–307. [CrossRef]

- Gao R, Shi H, Chang S, et al (2019) The selective NLRP3-inflammasome inhibitor MCC950 reduces myocardial fibrosis and improves cardiac remodeling in a mouse model of myocardial infarction. Int Immunopharmacol 74:105575. [CrossRef]

- Ong S-B, Hernández-Reséndiz S, Crespo-Avilan GE, et al (2018) Inflammation following acute myocardial infarction: Multiple players, dynamic roles, and novel therapeutic opportunities. Pharmacol Ther 186:73–87. [CrossRef]

- Kurup R, Galougahi KK, Figtree G, et al (2021) The Role of Colchicine in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Heart Lung Circ 30:795–806. [CrossRef]

- Zhang F, He Q, Qin CH, et al (2022) Therapeutic potential of colchicine in cardiovascular medicine: a pharmacological review. Acta Pharmacol Sin 43:2173–2190. [CrossRef]

- Martínez GJ, Robertson S, Barraclough J, et al (2015) Colchicine Acutely Suppresses Local Cardiac Production of Inflammatory Cytokines in Patients With an Acute Coronary Syndrome. J Am Heart Assoc 4:e002128. [CrossRef]

- Bouabdallaoui N, Tardif J-C, Waters DD, et al (2020) Time-to-treatment initiation of colchicine and cardiovascular outcomes after myocardial infarction in the Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (COLCOT). Eur Heart J 41:4092–4099. [CrossRef]

- Nagar A, Rahman T and Harton JA (2021) The ASC Speck and NLRP3 Inflammasome Function Are Spatially and Temporally Distinct. Front. Immunol. 12:752482. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.752482.

- Astiawati T, Rohman MS, Wihastuti TA, et al (2024) Antifibrotic effects of colchicine on 3T3 cell line ischemia to mitigate detrimental remodeling. J Pharm Pharmacogn Res 12:296–302. [CrossRef]

- Dhurandhar EJ, Dubuisson O, Mashtalir N, et al (2011) E4orf1: A Novel Ligand That Improves Glucose Disposal in Cell Culture. PLoS ONE 6:e23394. [CrossRef]

- Handari SD, Rohman MS, Sargowo D, Aulanni'am, Nugraha RA, Lestari B, Oceandy D. Novel Impact of Colchicine on Interleukin-10 Expression in Acute Myocardial Infarction: An Integrative Approach. J Clin Med. 2024 Aug 7;13(16):4619. doi: 10.3390/jcm13164619.

- Habanjar O, Diab-Assaf M, Caldefie-Chezet F, Delort L (2021) 3D Cell Culture Systems: Tumor Application, Advantages, and Disadvantages. Int J Mol Sci 22:12200. [CrossRef]

- Liang M, Si L, Yu Z, et al (2023) Intermittent hypoxia induces myofibroblast differentiation and extracellular matrix production of MRC5s via HIF-1α-TGF-β/Smad pathway. Sleep Breath. [CrossRef]

- Schlittler M, Pramstaller PP, Rossini A, De Bortoli M (2023) Myocardial Fibrosis in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Perspective from Fibroblasts. Int J Mol Sci 24:14845. [CrossRef]

- Tuncay S, Senol H, Guler EM, et al (2018) Synthesis of Oleanolic Acid Analogues and Their Cytotoxic Effects on 3T3 Cell Line. Med Chem 14:617–625. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi VK, Subramaniyan SA, Hwang I (2019) Molecular and Cellular Response of Co-cultured Cells toward Cobalt Chloride (CoCl 2 )-Induced Hypoxia. ACS Omega 4:20882–20893. [CrossRef]

- Tsuzuki T, Okada H, Cho H, et al (2012) Hypoxic stress simultaneously stimulates vascular endothelial growth factor via hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and inhibits stromal cell-derived factor-1 in human endometrial stromal cells. Hum Reprod 27:523–530. [CrossRef]

- Zou D, Zhang Z, He J, et al (2012) Blood vessel formation in the tissue-engineered bone with the constitutively active form of HIF-1α mediated BMSCs. Biomaterials 33:2097–2108. [CrossRef]

- Cheng B-C, Chen J-T, Yang S-T, et al (2017) Cobalt chloride treatment induces autophagic apoptosis in human glioma cells via a p53-dependent pathway. Int J Oncol 50:964–974. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Wang H, Li J (2016) Inflammation and Inflammatory Cells in Myocardial Infarction and Reperfusion Injury: A Double-Edged Sword. Clin Med Insights Cardiol 10:CMC.S33164. [CrossRef]

- He X, Zeng Y, Li G, et al (2020) Extracellular ASC exacerbated the recurrent ischemic stroke in an NLRP3-dependent manner. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 40:1048–1060. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Zhang S, Xiao Y, et al (2020) NLRP3 Inflammasome and Inflammatory Diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020:1–11. [CrossRef]

- Fusco R, Siracusa R, Genovese T, et al (2020) Focus on the Role of NLRP3 Inflammasome in Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 21:4223. [CrossRef]

- Protti MP, De Monte L (2020) Dual Role of Inflammasome Adaptor ASC in Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol 8:40. [CrossRef]

- Rahman T, Nagar A, Duffy EB, et al (2020) NLRP3 Sensing of Diverse Inflammatory Stimuli Requires Distinct Structural Features. Front Immunol 11:1828. [CrossRef]

- Zheng D, Liwinski T, Elinav E (2020) Inflammasome activation and regulation: toward a better understanding of complex mechanisms. Cell Discov 6:36. [CrossRef]

- Karaba AH, Figueroa A, Massaccesi G, et al (2020) Herpes simplex virus type 1 inflammasome activation in proinflammatory human macrophages is dependent on NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1. PLOS ONE 15:e0229570. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Dhalla NS (2024) The Role of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Mol Sci 25:1082. [CrossRef]

- Chen H, Zhang X, Liao N, et al (2018) Enhanced Expression of NLRP3 Inflammasome-Related Inflammation in Diabetic Retinopathy. Investig Opthalmology Vis Sci 59:978. [CrossRef]

- Nagar A, Rahman T, Harton JA (2021) The ASC Speck and NLRP3 Inflammasome Function Are Spatially and Temporally Distinct. Front Immunol 12:752482. [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini C, Martelli A, Antonioli L, et al (2021) NLRP3 inflammasome in cardiovascular diseases: Pathophysiological and pharmacological implications. Med Res Rev 41:1890–1926. [CrossRef]

- Zheng Y, Xu L, Dong N, Li F (2022) NLRP3 inflammasome: The rising star in cardiovascular diseases. Front Cardiovasc Med 9:927061. [CrossRef]

- Hu J, Xu J, Zhao J, et al (2024) Colchicine ameliorates short-term abdominal aortic aneurysms by inhibiting the expression of NLRP3 inflammasome components in mice. Eur J Pharmacol 964:176297. [CrossRef]

- Pagliaro P, Penna C (2023) Inhibitors of NLRP3 Inflammasome in Ischemic Heart Disease: Focus on Functional and Redox Aspects. Antioxidants 12:1396. [CrossRef]

- Naaz F, Haider MR, Shafi S, Yar MS (2019) Anti-tubulin agents of natural origin: Targeting taxol, vinca, and colchicine binding domains. Eur J Med Chem 171:310–331. [CrossRef]

- Banco D, Mustehsan M, Shah B (2024) Update on the Role of Colchicine in Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 26:191–198. [CrossRef]

- Sitia R, Rubartelli A (2018) The unconventional secretion of IL-1β: Handling a dangerous weapon to optimize inflammatory responses. Semin Cell Dev Biol 83:12–21. [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Lindemann U, Mauersberger C, Schmidt A-C, et al (2022) Colchicine Impacts Leukocyte Trafficking in Atherosclerosis and Reduces Vascular Inflammation. Front Immunol 13:898690. [CrossRef]

- Olcum M, Tastan B, Ercan I, et al (2020) Inhibitory effects of phytochemicals on NLRP3 inflammasome activation: A review. Phytomedicine 75:153238. [CrossRef]

- Kim S-K (2022) The Mechanism of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Pathogenic Implication in the Pathogenesis of Gout. J Rheum Dis 29:140–153. [CrossRef]

- Schuster R, Younesi F, Ezzo M, Hinz B (2023) The Role of Myofibroblasts in Physiological and Pathological Tissue Repair. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 15:a041231. [CrossRef]

- Bonaventura A, Abbate A (2023) Colchicine for cardiovascular prevention: the dawn of a new era has finally come. Eur Heart J 44:3303–3304. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sánchez J, Chánez-Cárdenas ME (2019) The use of cobalt chloride as a chemical hypoxia model. J Appl Toxicol 39:556–570. [CrossRef]

- Yuan X, Bhat OM, Zou Y, et al (2022) Endothelial Acid Sphingomyelinase Promotes NLRP3 Inflammasome and Neointima Formation During Hypercholesterolemia. J Lipid Res 63:100298. [CrossRef]

- Cullen SP, Kearney CJ, Clancy DM, Martin SJ (2015) Diverse Activators of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Promote IL-1β Secretion by Triggering Necrosis. Cell Rep 11:1535–1548. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).