Submitted:

05 January 2025

Posted:

09 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

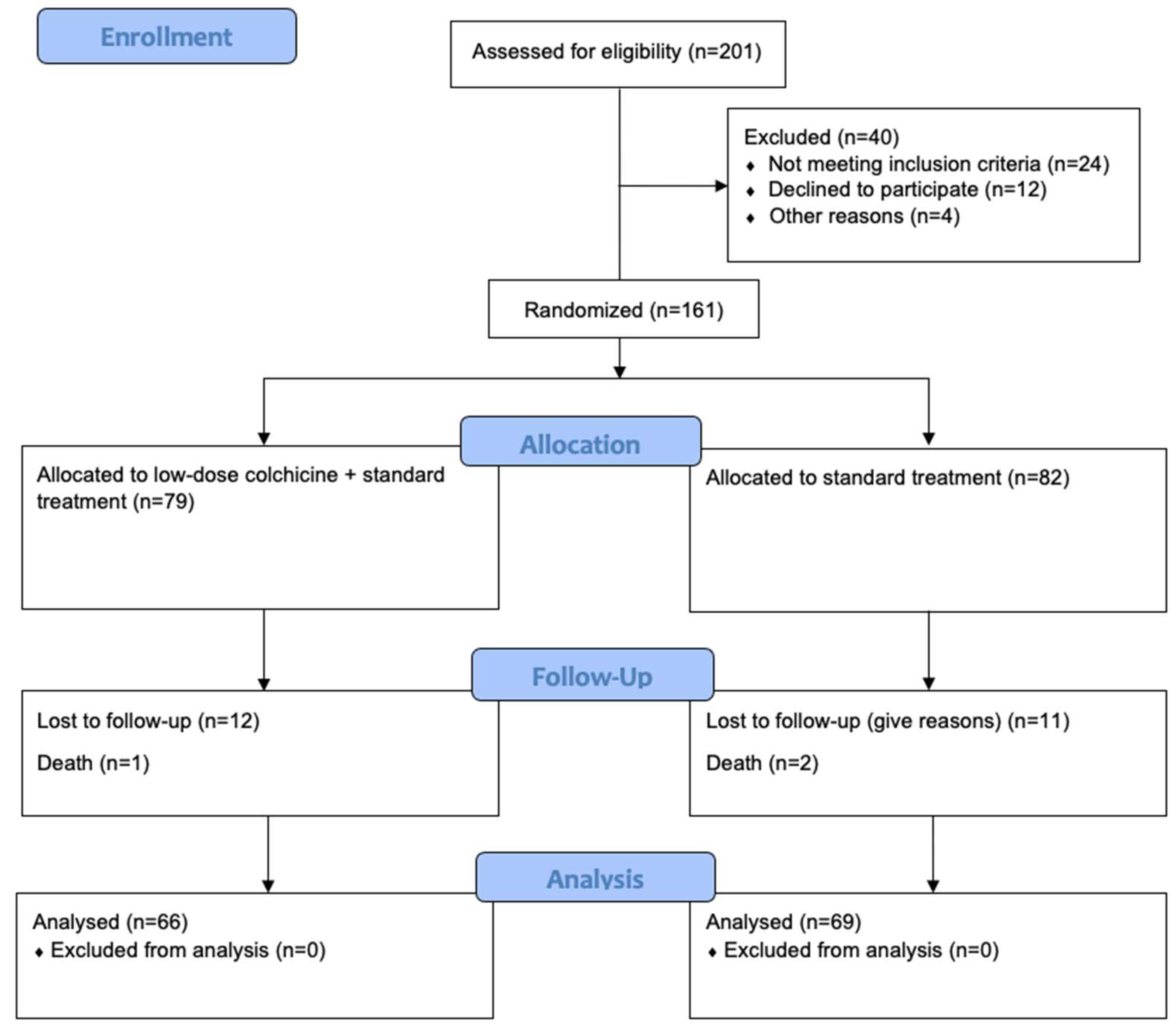

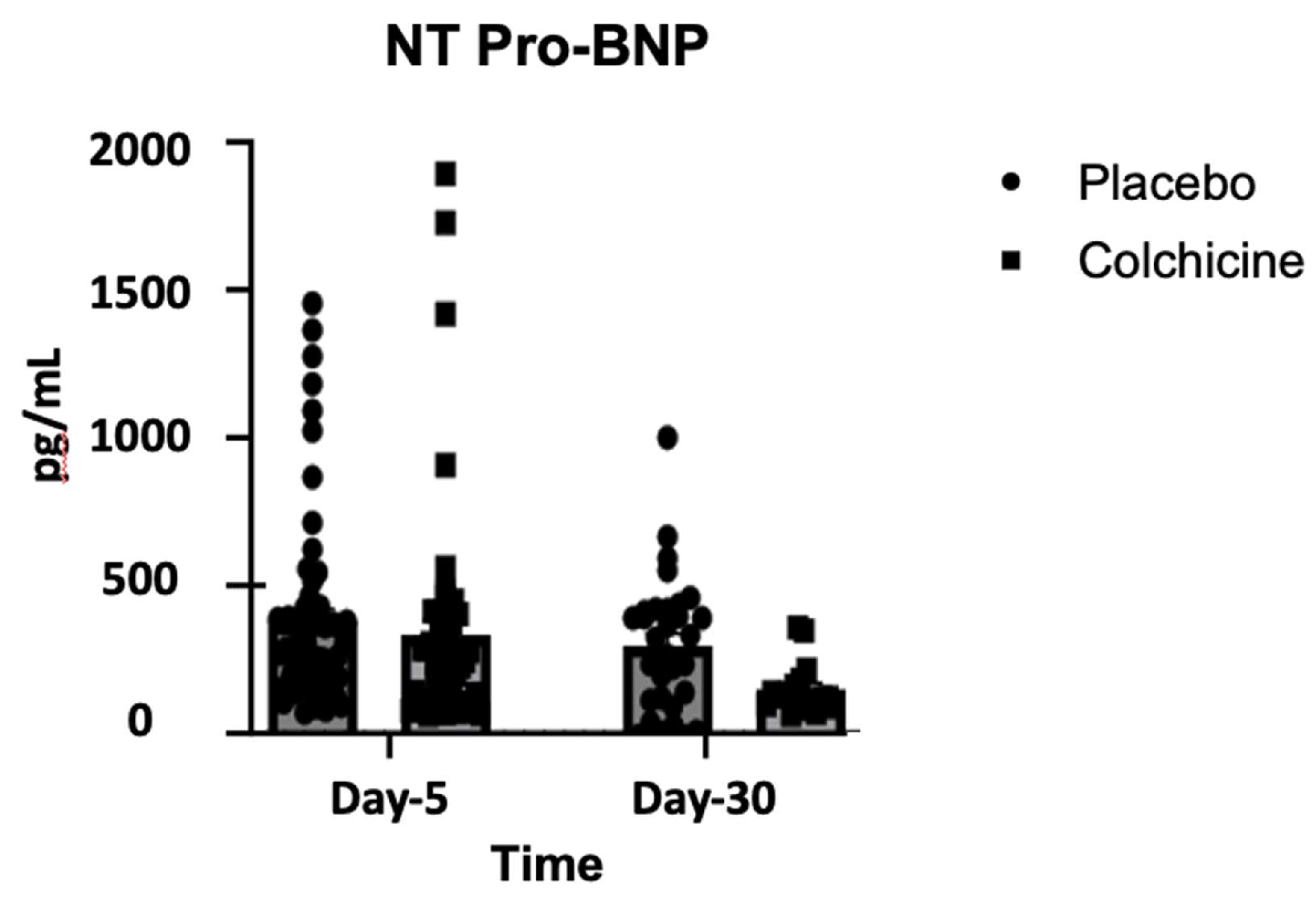

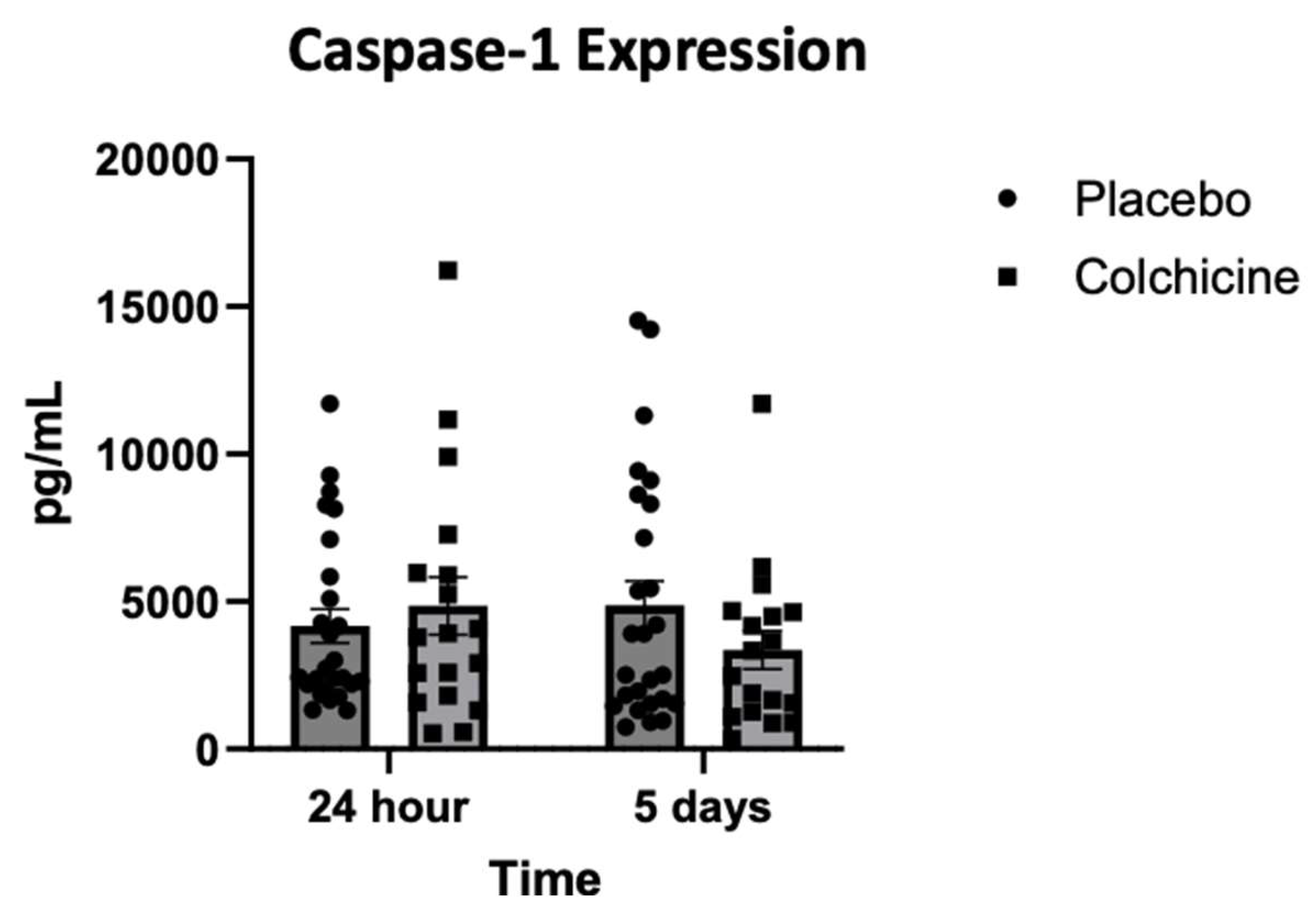

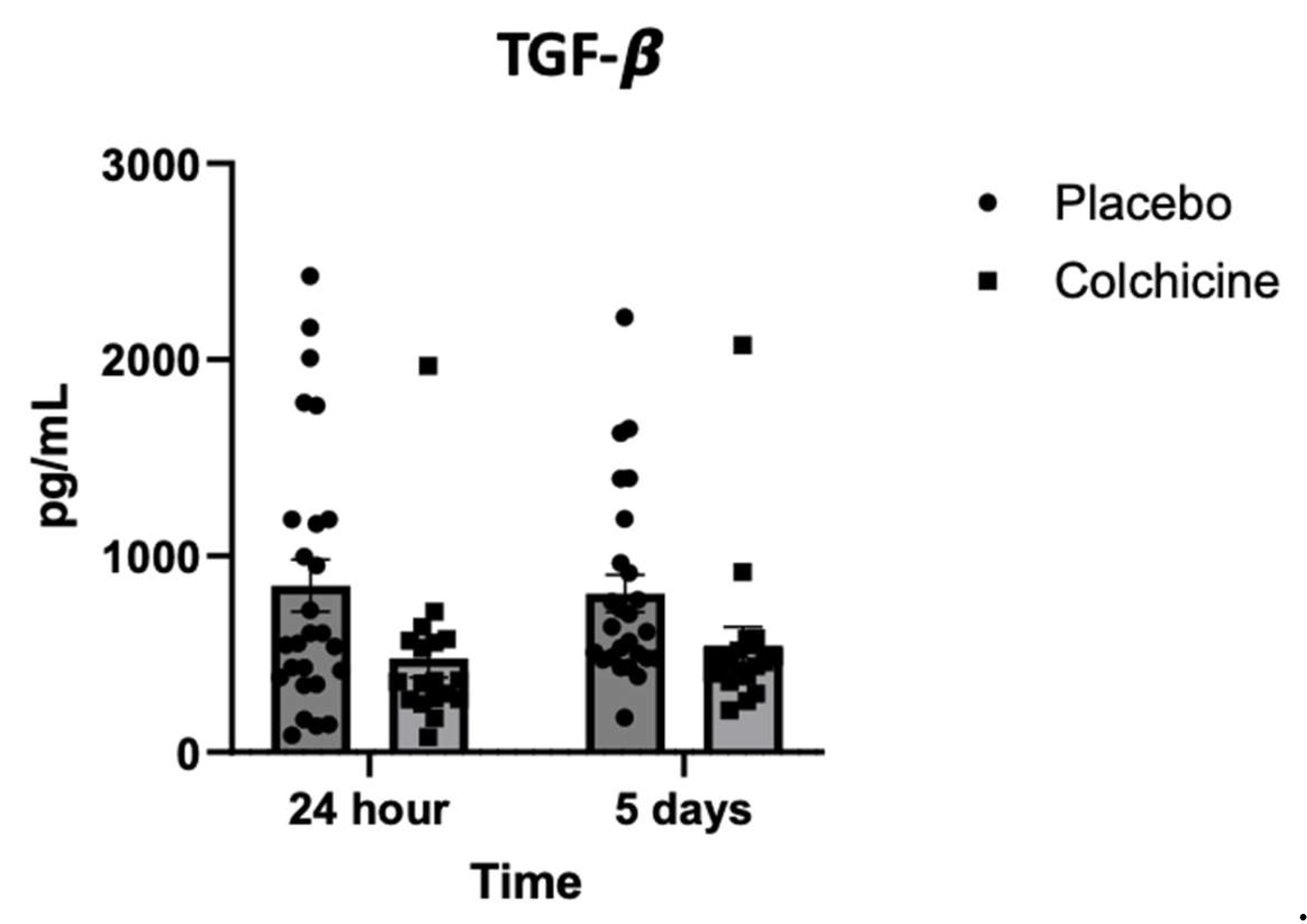

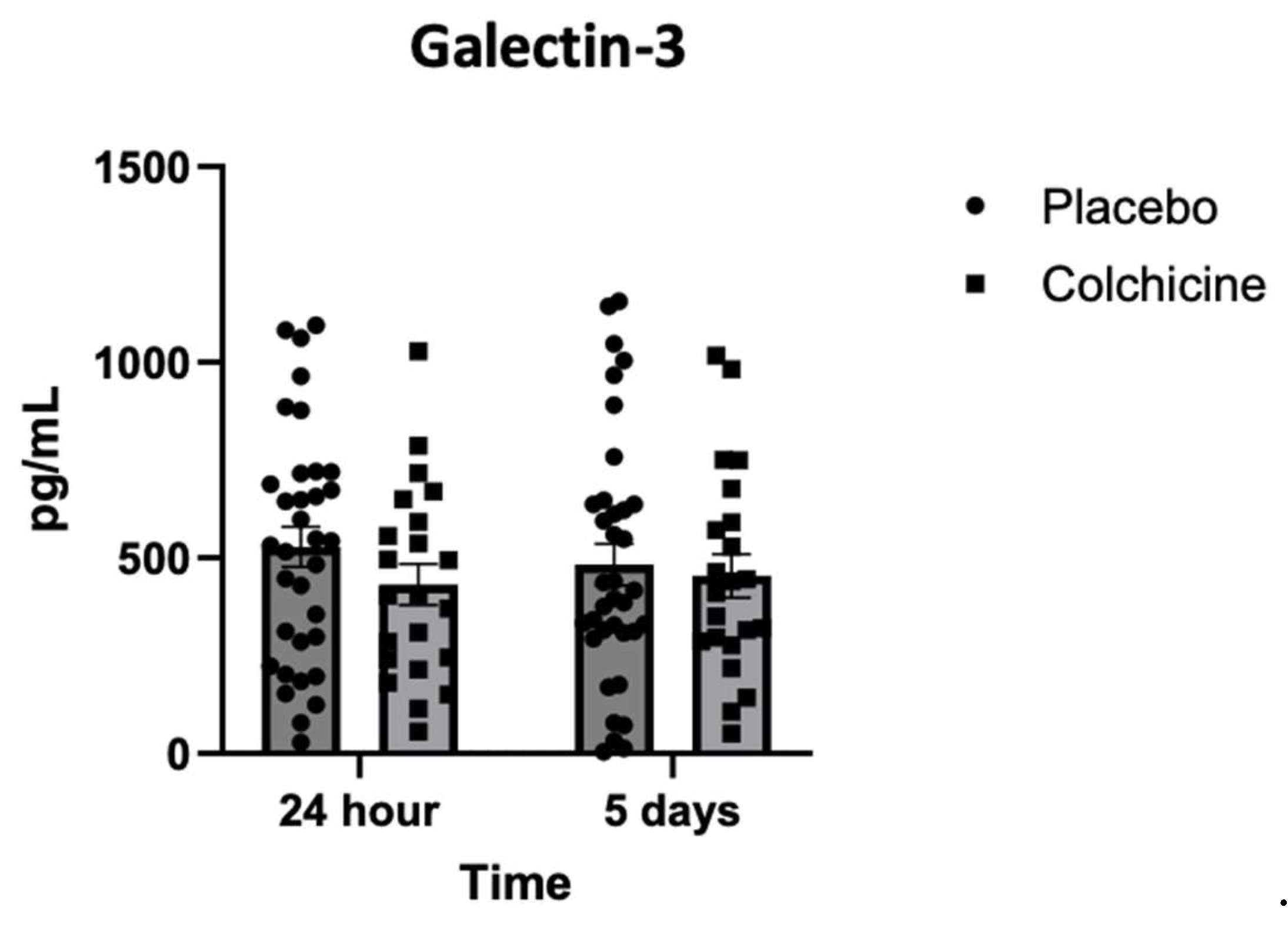

Background: Caspase-1 (reflects NOD-like receptor protein 3 inflammasomes activity), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and Galectin-3 play significant role in post-AMI fibrosis and inflammation. Recently, colchicine was shown to dampen inflammation after AMI, however, its direct benefit remains controversial. Objectives. This study aimed to analyze the benefit of colchicine in reducing NT-proBNP, Caspase-1, TGF-β and Galectin-3 expression and improving echocardiography parameter among AMI patients. Methods. Double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled, randomized, multicenter clinical trial was conducted at 3 hospitals in East Java Indonesia: Dr. Saiful Anwar Hospital Malang, Dr. Soebandi Hospital Jember, Dr. Iskak Hospital Tulungagung between 1 June-31 December 2023. Total of 161 eligible AMI subjects were randomly allocated 1:1 to colchicine (0.5 mg daily) or standard treatment for 30 days. Caspase-1, TGF-β, and Galectin-3 were tested on day-1 and day-5 by ELISA, whilst NT-proBNP were tested on day 5 and 30. Transthoracic echocardiography were also tested on day 5 and day 30. Results. On day-30, no significant improvement in echocardiography parameter had been shown in colchicine group. However, colchicine reduces level of NT-proBNP on day-30 greater than placebo (ΔNT-proBNP: -273.74 ± 87.53 vs. -75.75 ± 12.44 pg/mL; p<0.001). Moreover, colchicine lower level of Caspase-1 expression on day-5, level of TGF-β and Galectin-3 expression on day-1. Conclusion. Colchicine can reduce NT-proBNP, Caspase-1, TGF-β and Galectin-3 expression significantly among AMI patients but didn’t improve echocardiography parameters (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT06426537).

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Purposes

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trial Design and Trial Setting

2.2. Trial Population

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

2.4. Informed Consent

2.5. Randomization and Blinding

2.6. Trial Intervention

2.7. Trial Endpoints

2.8. Withdrawal Criteria

- Subjects who experience serious adverse events (AEs) throughout the trial

- Subjects with poor compliance and could not cooperate with clinical examination and follow-up

- Subjects who quit this clinical trial voluntarily. Subjects can withdraw from the study at any time for any reason. After withdrawal, the subjects’ data will be used with the patient’s consent.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Trial Participants

3.2. Changes in NT-proBNP During Treatment with Colchicine

3.3. Echocardiography Parameter After 30 Days of Experiments

| Echocardiography Parameters | Colchicine + standard treatment (n=66) | Standard treatment only (n=69) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| EF_Biplane | 50.57 ± 3.14 | 48.23 ± 2.47 | 0.908 |

| LVESV_Biplane | 50.86 ± 4.81 | 49.90 ± 3.61 | 0.990 |

| LVEDV_Biplane | 97.55 ± 5.79 | 101.39 ± 5.77 | 0.815 |

| EF_Teich | 52.84 ± 1.95 | 51.64 ± 2.05 | 0.878 |

| LVESV_Teich | 42.00 ± 2.92 | 39.68 ± 2.92 | 0.903 |

| LVEDV_Teich | 86.79 ± 4.38 | 84.71 ± 5.53 | 0.961 |

| E/E’ Septal | 10.45 ± 0.59 | 11.50 ± 0.53 | 0.527 |

| E/E’ Lateral | 8.92 ± 0.44 | 9.98 ± 0.87 | 0.874 |

| EA | 0.99 ± 0.07 | 1,09 ± 0.10 | 0.897 |

| TAPSE | 21.43 ± 0.70 | 20.55 ± 0.61 | 0.733 |

| CO | 4.29 ± 0.25 | 4.24 ± 0.29 | 1.000 |

| CI | 2.68 ± 0.18 | 2.56 ± 0.19 | 0.966 |

| SV | 54.96 ± 3.14 | 51.28 ± 2.91 | 0.797 |

| PCWP | 13.65 ± 0.56 | 14.82 ± 0.74 | 0.572 |

3.4. Expression of Caspase-1 During Treatment with Colchicine

3.5. Level of TGF-β Expression During Treatment with Colchicine

3.6. Level of Galectin-3 Expression During Treatment with Colchicine

4. Discussion

4.1. Strength and Limitation

5. Conclusions

6. Patient and Public Involvement Statement

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE-i | angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor |

| ACS | acute coronary syndrome |

| AEs | adverse events |

| AMI | acute myocardial infarction |

| ARB | angiotensin II receptor blockers |

| ARNI | angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor |

| BMI | body mass index |

| BUN | blood urea nitrogen |

| CI | cardiac index |

| CLEAR | Colchicine in Acute Myocardial Infarction |

| CO | cardiac output |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| DAMP | damage-associated molecular patterns |

| E/E’ | ratio between early diastolic mitral inflow velocity and early diastolic mitral annular tissue velocity in the lateral wall |

| EA | the ratio of the early (E) to late (A) ventricular filling velocities |

| EACVI | European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging |

| EF | ejection fraction |

| eGFR | estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| GRACE | The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events |

| IL | interleukin |

| LVEDV | Left Ventricular End-Diastolic Volume |

| LVESV | Left Ventricular End-Systolic Volume |

| MACE | major adverse cardiac events |

| HbA1c | hemoglobin A1c |

| HDL | high-density lipoprotein |

| hs-CRP | High Senitivity C-reactive Protein |

| ITT | intention-to-treat |

| LDL | low-density lipoprotein |

| LVOT | left ventricular outflow tract |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like receptor protein 3 |

| NSTEMI | non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide |

| PCI | percutaneous coronary intervention |

| PCWP | pulmonary capillary wedge pressure |

| PMM | predictive mean matching |

| PRR | pattern recognition receptors |

| SGLT-2 | sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 |

| SGOT | serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase |

| SGPT | serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase |

| STEMI | ST-elevation myocardial infarction |

| SV | stroke volume |

| TAPSE | tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor-β |

| TIMI | The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction |

| VTI | velocity time integral |

References

- Author Fang, L., Moore, X.-L., Dart, A. M., & Wang, L.-M. 2015. Systemic inflammatory response following acute myocardial infarction. Journal of Geriatric Cardiology: JGC, 2015; 12(3), 305. [CrossRef]

- Frangogiannis, N. G. 2014. The inflammatory response in myocardial injury, repair, and remodelling. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 2014; 11(5), 255–265. [CrossRef]

- Viola M, de Jager SCA, Sluijter JPG. 2021. Targeting Inflammation after Myocardial Infarction: A Therapeutic Opportunity for Extracellular Vesicles? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(15):7831. [CrossRef]

- Abbate A, Toldo S, Marchetti C, Kron J, Van Tassell BW, Dinarello CA. Interleukin-1 and the Inflammasome as Therapeutic Targets in Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Res. 2020;126(9):1260-1280. [CrossRef]

- Mittal M, Siddiqui MR, Tran K, Reddy SP, Malik AB. Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20(7):1126-1167. [CrossRef]

- Ong SB, Hernández-Reséndiz S, Crespo-Avilan GE, et al. Inflammation following acute myocardial infarction: Multiple players, dynamic roles, and novel therapeutic opportunities. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;186:73-87. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Ye X, Escames G, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome: contributions to inflammation-related diseases. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2023;28(1):51. Published 2023 Jun 27. [CrossRef]

- Marchetti C, Toldo S, Chojnacki J, et al. Pharmacologic Inhibition of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Preserves Cardiac Function After Ischemic and Nonischemic Injury in the Mouse. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2015;66(1):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Frantz S, Hundertmark MJ, Schulz-Menger J, Bengel FM, Bauersachs J. Left ventricular remodelling post-myocardial infarction: pathophysiology, imaging, and novel therapies. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(27):2549-2561. [CrossRef]

- Liu M, López de Juan Abad B, Cheng K. Cardiac fibrosis: Myofibroblast-mediated pathological regulation and drug delivery strategies. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;173:504-519. [CrossRef]

- Humeres C, Frangogiannis NG. Fibroblasts in the Infarcted, Remodeling, and Failing Heart. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2019;4(3):449-467. Published 2019 Jun 24. [CrossRef]

- Frangogiannis N. Transforming growth factor-β in tissue fibrosis. J Exp Med. 2020;217(3):e20190103. Published 2020 Feb 13. [CrossRef]

- Ma Y, Zou H, Zhu XX, et al. Transforming growth factor β: A potential biomarker and therapeutic target of ventricular remodeling. Oncotarget. 2017;8(32):53780-53790. Published 2017 Apr 19. [CrossRef]

- Dobaczewski M, Chen W, Frangogiannis NG. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling in cardiac remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011 Oct;51(4):600-6. [CrossRef]

- Seropian IM, Cassaglia P, Miksztowicz V, González GE. Unraveling the role of galectin-3 in cardiac pathology and physiology. Front Physiol. 2023;14:1304735. Published 2023 Dec 18. [CrossRef]

- Calver JF, Parmar NR, Harris G, Lithgo RM, Stylianou P, Zetterberg FR, Gooptu B, Mackinnon AC, Carr SB, Borthwick LA, Scott DJ, Stewart ID, Slack RJ, Jenkins RG, John AE. Defining the mechanism of galectin-3-mediated TGF-β1 activation and its role in lung fibrosis. J Biol Chem. 2024 Jun;300(6):107300. [CrossRef]

- Chen H, Chen C, Fang J, Wang R, Nie W. Circulating galectin-3 on admission and prognosis in acute heart failure patients: a meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev. 2020 Mar;25(2):331-341. [CrossRef]

- Di Tano G, Caretta G, De Maria R, Parolini M, Bassi L, Testa S, Pirelli S. Galectin-3 predicts left ventricular remodelling after anterior-wall myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart. 2017 Jan 1;103(1):71-77. [CrossRef]

- Wu X, Liu Y, Tu D, Liu X, Niu S, Suo Y, Liu T, Li G, Liu C. Role of NLRP3-Inflammasome/Caspase-1/Galectin-3 Pathway on Atrial Remodeling in Diabetic Rabbits. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2020 Oct;13(5):731-740. [CrossRef]

- Huang S, Frangogiannis NG. Anti-inflammatory therapies in myocardial infarction: failures, hopes and challenges. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175(9):1377-1400. [CrossRef]

- Deftereos SG, Beerkens FJ, Shah B, et al. Colchicine in Cardiovascular Disease: In-Depth Review. Circulation. 2022;145(1):61-78. [CrossRef]

- Leung YY, Yao Hui LL, Kraus VB. Colchicine--Update on mechanisms of action and therapeutic uses. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45(3):341-350. [CrossRef]

- Cronstein BN, Molad Y, Reibman J, Balakhane E, Levin RI, Weissmann G, et al. Colchicine alters the quantitative and qualitative display of selectins on endothelial cells and neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 1995;96(2):994–1002. [CrossRef]

- Handari SD, Rohman MS, Sargowo D, Aulanni’am, Nugraha RA, Lestari B, Oceandy D. Novel Impact of Colchicine on Interleukin-10 Expression in Acute Myocardial Infarction: An Integrative Approach. J Clin Med. 2024 Aug 7;13(16):4619. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Yang H, Qin Z, Wang Q, Li L. Colchicine ameliorates myocardial injury induced by coronary microembolization through suppressing pyroptosis via the AMPK/SIRT1/NLRP3 signaling pathway. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2024;24(1):23. Published 2024 Jan 3. [CrossRef]

- Bakhta O, Blanchard S, Guihot AL, Tamareille S, Mirebeau-Prunier D, Jeannin P, Prunier F. Cardioprotective Role of Colchicine Against Inflammatory Injury in a Rat Model of Acute Myocardial Infarction. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Sep;23(5):446-455. [CrossRef]

- Tardif JC, Kouz S, Waters DD, Bertrand OF, Diaz R, Maggioni AP, Pinto FJ, Ibrahim R, Gamra H, Kiwan GS, Berry C, López-Sendón J, Ostadal P, Koenig W, Angoulvant D, Grégoire JC, Lavoie MA, Dubé MP, Rhainds D, Provencher M, Blondeau L, Orfanos A, L’Allier PL, Guertin MC, Roubille F. Efficacy and Safety of Low-Dose Colchicine after Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019 Dec 26;381(26):2497-2505. [CrossRef]

- Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Chaitman BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA, White HD, Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(18):2231–64. [CrossRef]

- Zhong B. How to calculate sample size in randomized controlled trial? J Thorac Dis. 2009;1(1):51-54.

- Pascual-Figal D, Núñez J, Pérez-Martínez MT, et al. Colchicine in acutely decompensated heart failure: the COLICA trial. Eur Heart J. Published online August 30, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Makmun LH, Kamelia T, Yusuf PA. Pulmonary Artery Wedge Pressure Formula Using Echocardiography Finding. Acta Med Indones. 2023 Apr;55(2):219-222.

- Steeds RP, Garbi M, Cardim N, Kasprzak JD, Sade E, Nihoyannopoulos P, Popescu BA, Stefanidis A, Cosyns B, Monaghan M, Aakhus S, Edvardsen T, Flachskampf F, Galiuto L, Athanassopoulos G, Lancellotti P; 2014–2016 EACVI Scientific Documents Committee; 2014–2016 EACVI Scientific Documents Committee. EACVI appropriateness criteria for the use of transthoracic echocardiography in adults: a report of literature and current practice review. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017 Nov 1;18(11):1191-1204. [CrossRef]

- Shengshou H, Runlin G, Lisheng L, et al. Summary of the 2018 report on cardiovascular diseases in China. Chin Circ J 2019;34:209-20. [Google Scholar].

- Ujueta F, Weiss EN, Shah B, et al. Effect of percutaneous coronary intervention on survival in patients with stable ischemic heart disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 2017;19:17. [CrossRef]

- Dasgeb B, Kornreich D, McGuinn K, Okon L, Brownell I, Sackett DL. Colchicine: an ancient drug with novel applications. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Feb;178(2):350-356. [CrossRef]

- Zhang FS, He QZ, Qin CH, Little PJ, Weng JP, Xu SW. Therapeutic potential of colchicine in cardiovascular medicine: a pharmacological review. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2022 Sep;43(9):2173-2190. [CrossRef]

- Nidorf SM, Eikelboom JW, Budgeon CA and Thompson PL. Low-dose colchicine for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:404–410. [CrossRef]

- Nidorf SM, Fiolet ATL, Mosterd A, Eikelboom JW, Schut A, Opstal TSJ, The SHK, Xu XF, Ireland MA, Lenderink T, et al. Colchicine in Patients with Chronic Coronary Disease. The New England journal of medicine 2020;383:1838–1847. [CrossRef]

- Jolly SS, d’Entremont MA, Lee SF, Mian R, Tyrwhitt J, Kedev S, Montalescot G, Cornel JH, Stanković G, Moreno R, Storey RF, Henry TD, Mehta SR, Bossard M, Kala P, Layland J, Zafirovska B, Devereaux PJ, Eikelboom J, Cairns JA, Shah B, Sheth T, Sharma SK, Tarhuni W, Conen D, Tawadros S, Lavi S, Yusuf S; CLEAR Investigators. Colchicine in Acute Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2024 Nov 17. [CrossRef]

- Handari SD, Rohman MS, Sargowo D, Aulanni’am, Nugraha RA, Lestari B, Oceandy D. Novel Impact of Colchicine on Interleukin-10 Expression in Acute Myocardial Infarction: An Integrative Approach. J Clin Med. 2024 Aug 7;13(16):4619. [CrossRef]

- Shojaeifard M, Pakbaz M, Beheshti R, Noohi Bezanjani F, Ahangar H, Gohari S, Dehghani Mohammad Abadi H, Erami S. The effect of colchicine on the echocardiographic constrictive physiology after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Echocardiography. 2020 Mar;37(3):399-403. [CrossRef]

- Shah B, Pillinger M, Zhong H, Cronstein B, Xia Y, Lorin JD, Smilowitz NR, Feit F, Ratnapala N, Keller NM, Katz SD. Effects of Acute Colchicine Administration Prior to Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: COLCHICINE-PCI Randomized Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2020 Apr;13(4):e008717. [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Colchicine + standard treatment (n=66) | Standard treatment only (n=69) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD, years) | 58.27 ± 1.307 | 55.32 ± 1.45 | 0.448 |

| Sex (female, %) | 33.15 ± 2.44 | 32.89 ± 2.51 | 0.136 |

| Body weight (mean ± SD, kilograms) | 61.35 ± 1.265 | 63.30 ± 1.233 | 0.742 |

| Body height (mean ± SD, centimeters) | 161.71 ± 1.026 | 163.94 ± 0.711 | 0.324 |

| BMI (mean ± SD, kg/m2) | 23.43 ± 0.408 | 23.5 ± 0.35 | 0.492 |

| Smoker (%) | 51,15 ± 8.44 | 51.27 ± 8.32 | 0.900 |

| Hypertension (%) | 58.66 ± 9.31 | 58.67 ± 9.29 | 0.945 |

| Type 2 Diabetes (%) | 33.56 ± 1.87 | 33.12 ± 1.69 | 0.453 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 72.09 ± 11.88 | 72.12 ± 12.51 | 0.895 |

| Systolic blood pressure on ER (mean ± SD, mmHg) | 130.32 ± 3.802 | 132.79 ± 4.136 | 0.783 |

| Diastolic blood pressure on ER (mean ± SD, mmHg) | 80.92 ± 3.12 | 82.34 ± 2.717 | 0.584 |

| Heart rate on ER (mean ± SD, bpm) | 79.05 ± 3.55 | 78.08 ± 3.01 | 0.661 |

| Systolic blood pressure on ICU (mean ± SD, mmHg) | 123.24 ± 2.62 | 124.05 ± 3.49 | 0.919 |

| Diastolic blood pressure on ICU (mean ± SD, mmHg) | 77.32 ± 1.74 | 78.34 ± 2.66 | 0.954 |

| Heart rate on ICU (mean ± SD, bpm) | 80.97 ±1.88 | 78.63 ± 2.12 | 0.993 |

| Killip class (mean ± SD) | 1.84 ± 0.52 | 1.83 ± 0.49 | 0.899 |

| GRACE score (mean ± SD) | 109.27 ± 3.92 | 104.08 ± 4.95 | 0.344 |

| TIMI score (mean ± SD) | 2.65 ± 0.88 | 2.67 ± 0.84 | 0.864 |

| Hemoglobin (mean ± SD, g/dL) | 15.30 ± 0.38 | 14.86 ± 0.46 | 0.983 |

| Hematocrit (mean ± SD, %) | 42.78 ± 1.50 | 43.50 ± 1.25 | 0.699 |

| WBC (mean ± SD, cells × 109/L) | 14.44 ± 1.15 | 12.56 ± 0.93 | 0.992 |

| Platelet count (mean ± SD, cells / mm3) | 296.20 ± 21.57 | 284.14 ± 15.79 | 0.992 |

| Serum creatinine (mean ± SD, mg/dL) | 1.33 ± 0.24 | 1.14 ± 0.07 | 0.990 |

| eGFR (mean ± SD, ml/min/1,73m2) | 71.60 ± 9.46 | 77.21 ± 5.75 | 0.675 |

| BUN (mean ± SD, mg/dL) | 14.99 ± 1.40 | 12.38 ± 1.26 | 0.999 |

| SGOT (mean ± SD, U/L) | 111.80 ± 28.15 | 86.21 ± 16.95 | 0.252 |

| SGPT (mean ± SD, U/L) | 33.70 ± 7.83 | 37.86 ± 5.76 | 0.999 |

| Random blood glucose (mean ± SD, mg/dL) | 147.64 ± 10.35 | 143.40 ± 7.49 | 0.229 |

| HbA1c (mean ± SD, %) | 5.97 ± 0.29 | 5.82 ± 0.13 | 0.730 |

| Sodium level (mean ± SD, mEq/L) | 136.93 ± 0.75 | 138.50 ± 0.97 | 1.000 |

| Potassium level (mean ± SD, mEq/L) | 4.13 ± 0.11 | 3.93 ± 0.15 | 0.996 |

| Chloride level (mean ± SD, mEq/L) | 103.43 ± 0.86 | 103.40 ± 0.69 | 0.982 |

| Total bilirubin level (mean ± SD, mg/dL) | 0.96 ± 0.12 | 0.96 ± 0.12 | 0.696 |

| Troponin I (mean ± SD, pg/mL) | 7775.89 ± 3640.94 | 7627.20 ± 4404.32 | 0.996 |

| Total cholesterol (mean ± SD, mg/dL) | 182.86 ± 13.80 | 176.80 ± 14.26 | 0.944 |

| LDL (mean ± SD, mg/dL) | 138.43 ± 11.97 | 124.20 ± 13.33 | 1.000 |

| HDL (mean ± SD, mg/dL) | 37.93 ± 3.10 | 39.70 ± 3.82 | 0.916 |

| Triglyceride (mean ± SD, mg/dL) | 182.29 ± 50.19 | 164.60 ± 32.95 | 1.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).