Submitted:

26 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

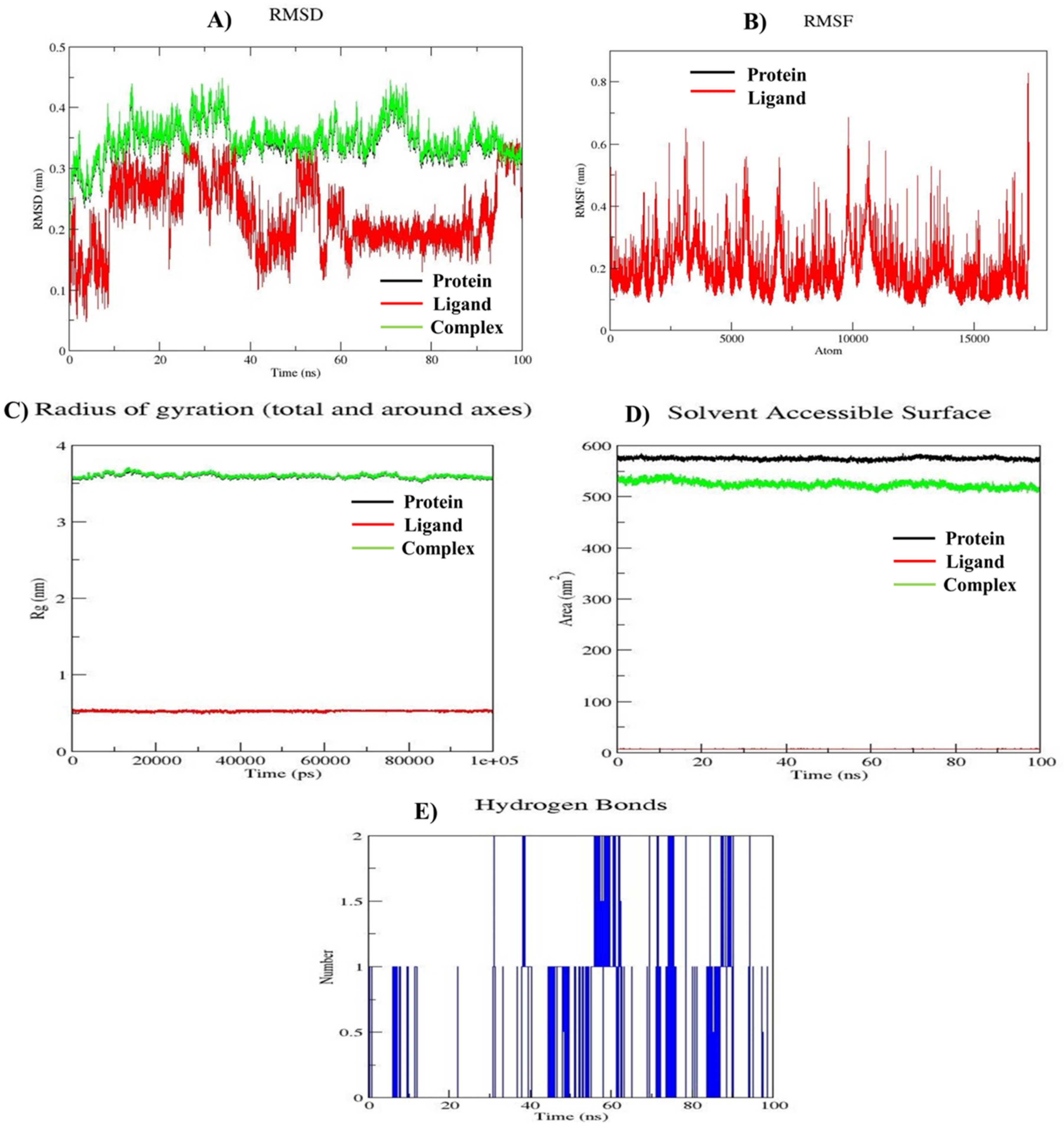

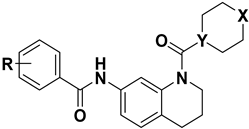

This study explores the design and synthesis of substituted tetrahydroquinoline (THQ) derivatives as potential mTOR inhibitors for targeted cancer therapy. Inspired by the structural characteristics of known mTOR inhibitors, eight novel derivatives were synthesized, characterized using advanced spectroscopic techniques, and evaluated for anticancer activity. Computational studies, including molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, highlighted the derivative's strong binding affinity and stability within the mTOR active site. In-vitro cytotoxicity assays demonstrated potent and selective anticancer activity against A549, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231 cancer cell lines, with minimal toxicity toward normal cells. Compound 10e emerged as the most promising candidate, displaying exceptional activity against A549 cells (IC₅₀ = 0.033 µM) and inducing apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner, surpassing standard agents like Everolimus and 5 Flurouracil. Structure-activity relationship analysis revealed that incorporating trifluoromethyl and morpholine moieties significantly enhanced selectivity and potency. MD simulations further validated these findings, confirming stable protein-ligand interactions and favorable dynamics over a 100-ns simulation period. Collectively, this study underscores the therapeutic potential of THQ derivatives, particularly compound 10e, as promising mTOR inhibitors with potential applications in lung cancer treatment.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodologies

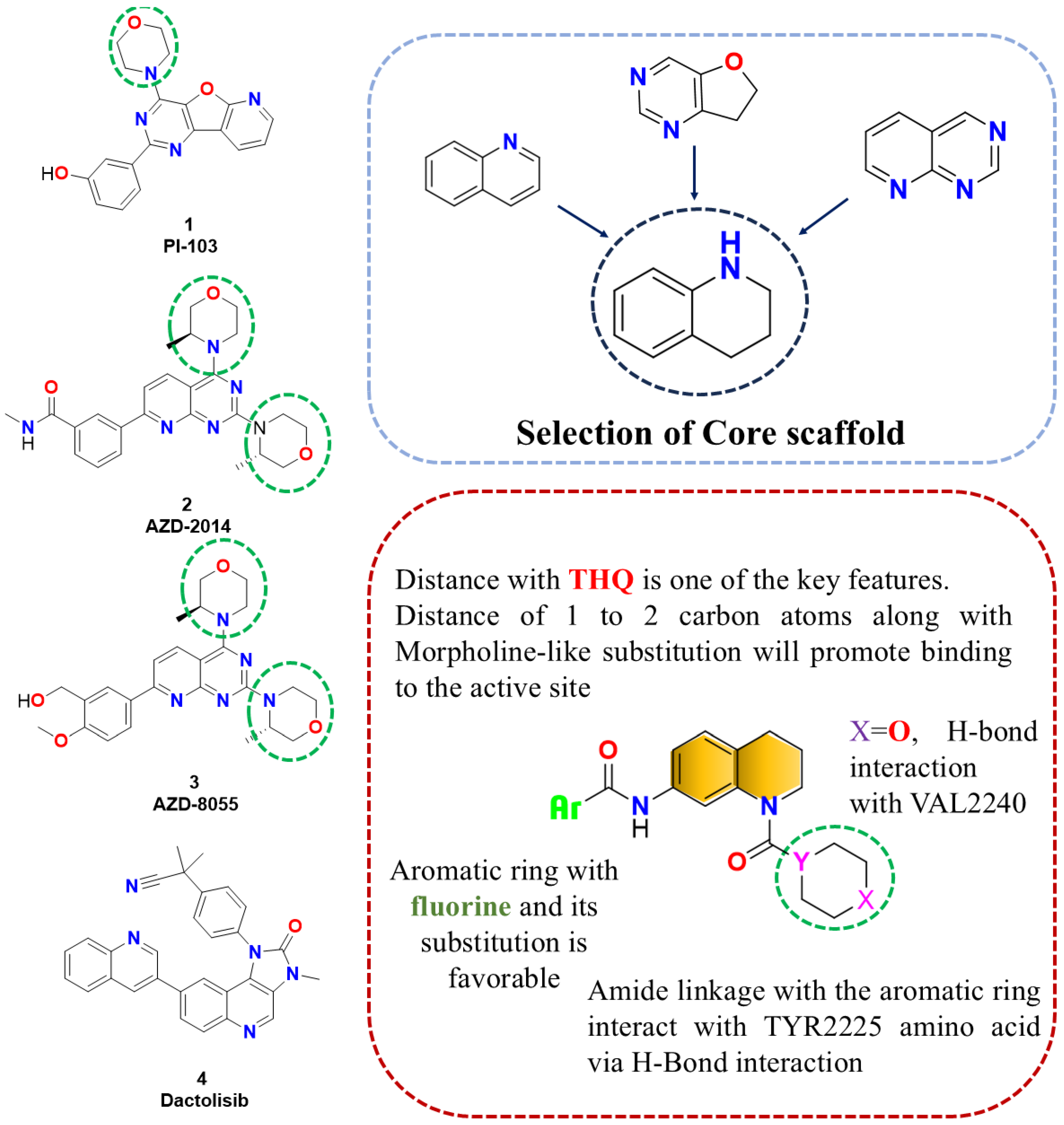

2.1. Designing rationale of Morpholine substituted THQ derivatives

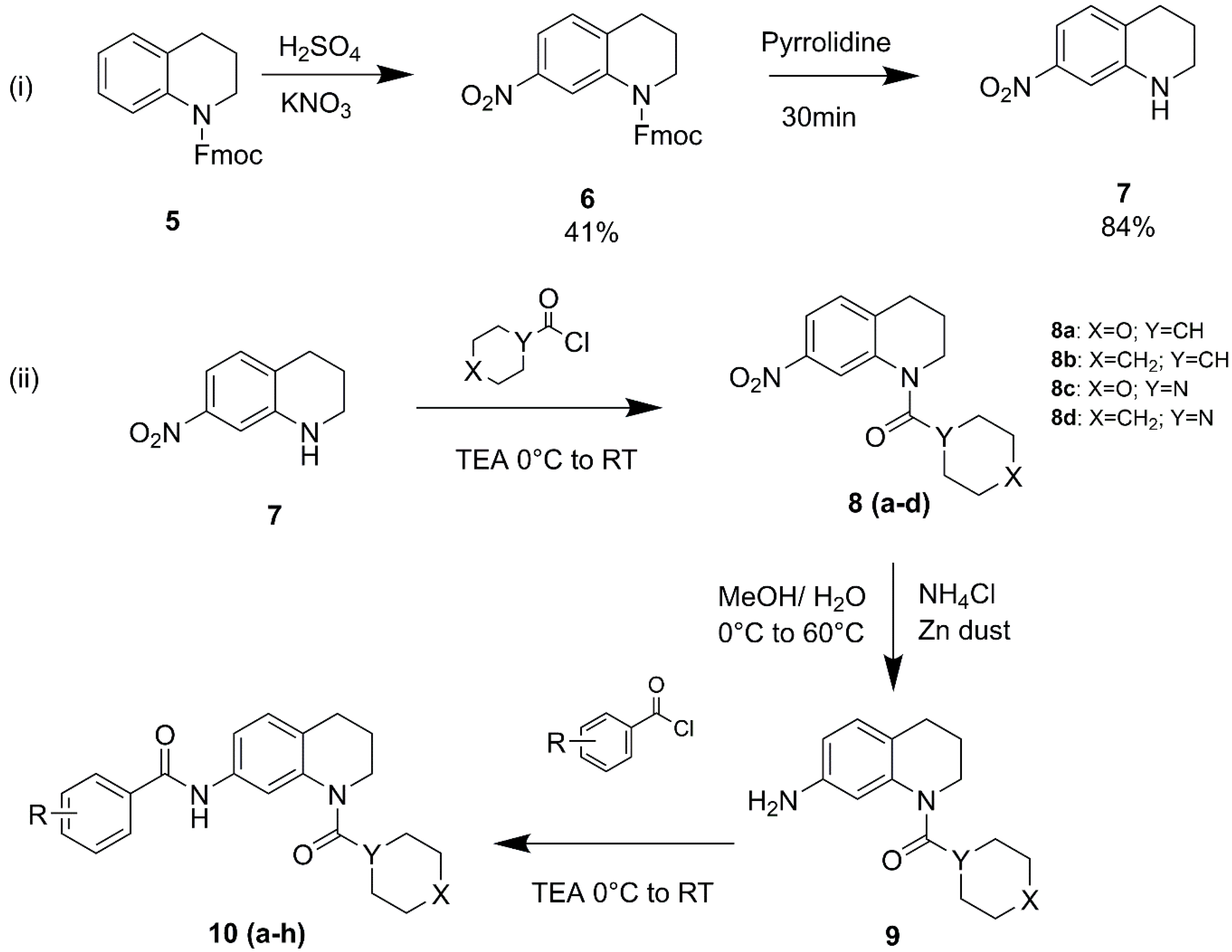

2.2. Synthesis and spectral characterization of designed THQ derivatives

2.2.1. Synthesis of 7-nitro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline

2.2.2. Synthesis of (7-nitro-3,4-dihydroquinolin-1(2H)-yl)(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-yl)methanone (8a)

2.2.3. Synthesis of cyclohexyl(7-nitro-3,4-dihydroquinolin-1(2H)-yl)methanone (8b)

2.2.4. Synthesis of morpholino(7-nitro-3,4-dihydroquinolin-1(2H)-yl)methanone (8c)

2.2.5. Synthesis of (7-nitro-3,4-dihydroquinolin-1(2H)-yl)(piperidin-1-yl)methanone (8d)

2.2.6. Synthesis of (7-amino-3,4-dihydroquinolin-1(2H)-yl)(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-yl)methanone (9a)

2.2.7. Synthesis of (7-amino-3,4-dihydroquinolin-1(2H)-yl)(cyclohexyl)methanone (9b)

2.2.8. Synthesis of morpholino(7-amino-3,4-dihydroquinolin-1(2H)-yl)methanone (9c)

2.2.9. Synthesis of (7-amino-3,4-dihydroquinolin-1(2H)-yl)(piperidin-1-yl)methanone (9d)

2.2.10. Synthesis of N-(1-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-carbonyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolin-7-yl)-4-(trifluoromethoxy)benzamide (10a)

2.2.11. Synthesis of N-(1-(cyclohexanecarbonyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolin-7-yl)-4-(trifluoromethoxy)benzamide (10b)

2.2.12. Synthesis of 3,5-difluoro-N-(1-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-carbonyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolin-7-yl)benzamide (10c)

2.2.12. Synthesis of 3-fluoro-N-(1-(morpholine-4-carbonyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolin-7-yl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)benzamide (10d)

2.2.13. Synthesis of N-(1-(morpholine-4-carbonyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolin-7-yl)-3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzamide (10e)

2.2.14. Synthesis of 3,5-difluoro-N-(1-(piperidine-1-carbonyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolin-7-yl)benzamide (10f)

2.2.15. Synthesis of 3-fluoro-N-(1-(piperidine-1-carbonyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolin-7-yl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)benzamide (10g)

2.2.16. Synthesis of N-(1-(piperidine-1-carbonyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolin-7-yl)-3,5 bis(trifluoromethyl)benzamide (10h)

2.3. In-vitro antiproliferative MTT assay

2.4. Apoptosis assay

2.5. Molecular Docking

2.6. Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemistry

3.2. In-vitro antiproliferative MTT assay

3.3. Structure-Activity Relationship

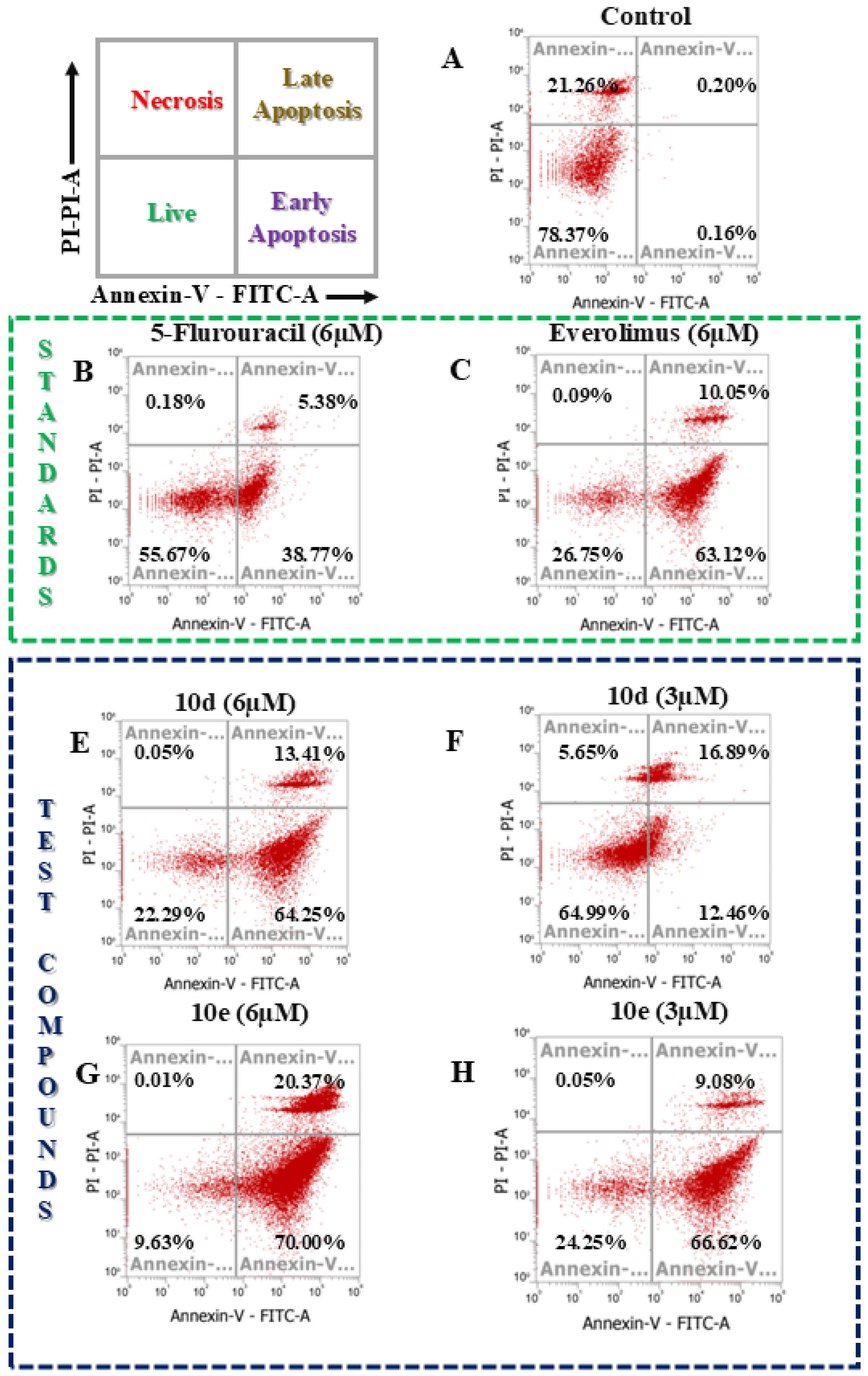

3.4. Apoptosis Assay

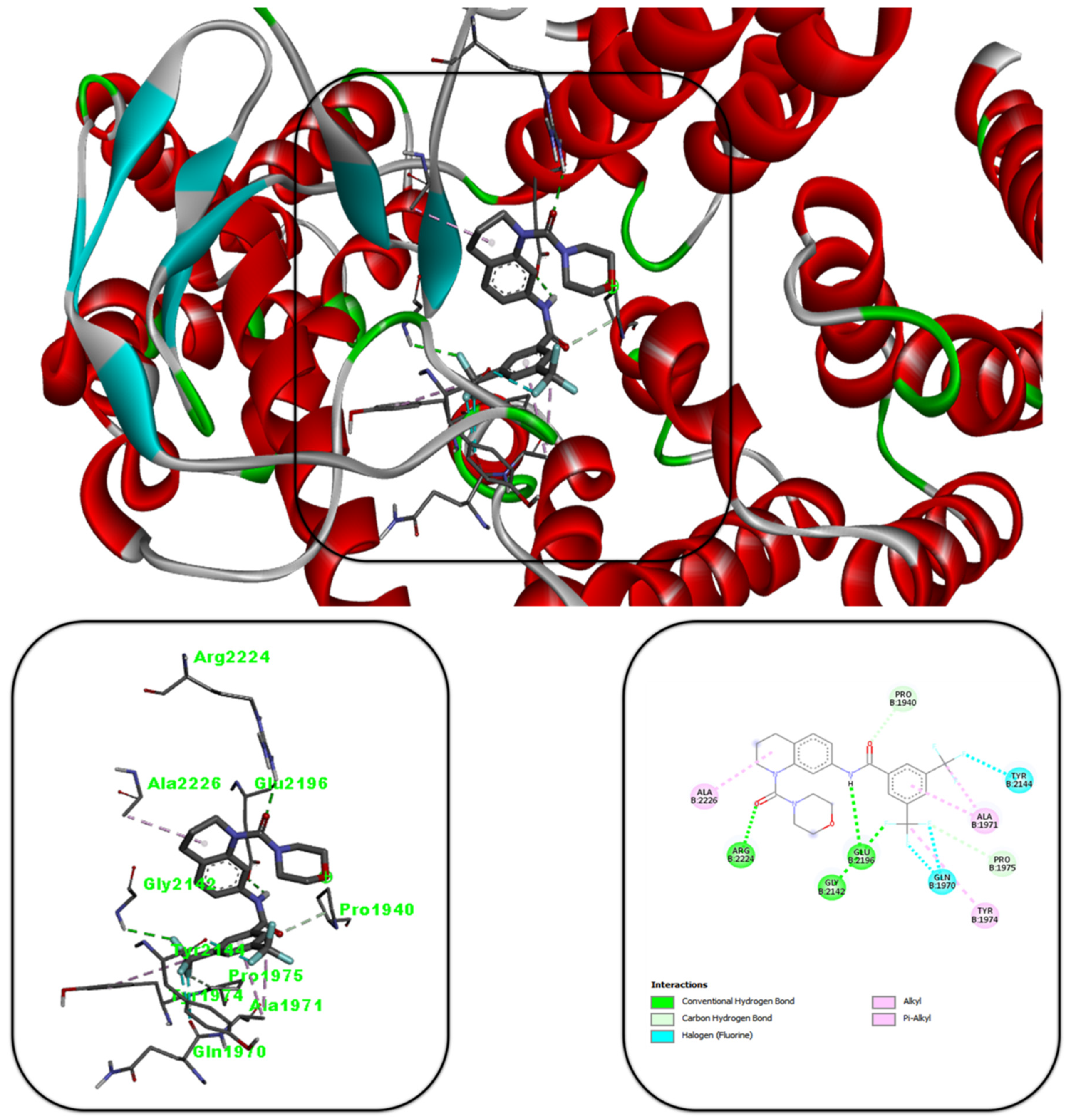

3.5. Molecular Docking Studies

3.6. MD Simulation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Financial and Competing Interests Disclosure

Declaration of Interest Statement

Author Contributions

Acknowledgement

References

- Vishwakarma, K.; Dey, R.; Bhatt, H. Telomerase: A Prominent Oncological Target for Development of Chemotherapeutic Agents. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2023, 249, 115121. [CrossRef]

- Dey, R.; Vishwakarma, K.; Patel, B.; Vyas, V.K.; Bhatt, H. Evolution of Telomerase Inhibitors: A Review on Key Patents from 2015 to 2023. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202404444. [CrossRef]

- Soliman, G. The Role of Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) Complexes Signaling in the Immune Responses. Nutrients 2013, 5, 2231–2257. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Tao, T.; Li, H.; Zhu, X. mTOR Signaling Pathway and mTOR Inhibitors in Cancer: Progress and Challenges. Cell Biosci 2020, 10, 31. [CrossRef]

- Bouyahya, A.; El Allam, A.; Aboulaghras, S.; Bakrim, S.; El Menyiy, N.; Alshahrani, M.M.; Al Awadh, A.A.; Benali, T.; Lee, L.-H.; El Omari, N.; et al. Targeting mTOR as a Cancer Therapy: Recent Advances in Natural Bioactive Compounds and Immunotherapy. Cancers 2022, 14, 5520. [CrossRef]

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168, 960–976. [CrossRef]

- Panwar, V.; Singh, A.; Bhatt, M.; Tonk, R.K.; Azizov, S.; Raza, A.S.; Sengupta, S.; Kumar, D.; Garg, M. Multifaceted Role of mTOR (Mammalian Target of Rapamycin) Signaling Pathway in Human Health and Disease. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 375. [CrossRef]

- Qaderi, S.; Javinani, A.; Blumenfeld, Y.J.; Krispin, E.; Papanna, R.; Chervenak, F.A.; Shamshirsaz, A.A. Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Inhibitors: A New-possible Approach for In-utero Medication Therapy. Prenatal Diagnosis 2024, 44, 88–98. [CrossRef]

- Mao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, L.; Zhao, D.-S.; Zhao, P.; Yan, P. Overview of Research into mTOR Inhibitors. Molecules 2022, 27, 5295. [CrossRef]

- Dey, R.; Chaube, U.; Bhatt, H.; Patel, B. Small Molecule Drug Design. In Reference Module in Life Sciences; Elsevier, 2024; p. B9780323955027002621 ISBN 978-0-12-809633-8.

- Meng, L.; Zheng, X.S. Toward Rapamycin Analog (Rapalog)-Based Precision Cancer Therapy. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2015, 36, 1163–1169. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kim, S.G.; Blenis, J. Rapamycin: One Drug, Many Effects. Cell Metabolism 2014, 19, 373–379. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Li, Y.; Xiong, L.; Wang, W.; Wu, M.; Yuan, T.; Yang, W.; Tian, C.; Miao, Z.; Wang, T.; et al. Small Molecules in Targeted Cancer Therapy: Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 201. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, H.; He, Q.; Chen, K.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, R.; Li, H.; Fang, S.; Liu, S.; Lin, S. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Tetrahydroquinoline Amphiphiles as Membrane-Targeting Antimicrobials against Pathogenic Bacteria and Fungi. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2022, 243, 114734. [CrossRef]

- Manolov, S.; Ivanov, I.; Bojilov, D. Synthesis of New 1,2,3,4-Tetrahydroquinoline Hybrid of Ibuprofen and Its Biological Evaluation. Molbank 2022, 2022, M1350. [CrossRef]

- Fathy, U.; Azzam, M.A.; Mahdy, F.; El-Maghraby, S.; Allam, R.M. Synthesis and in Vitro Anticancer Activity of Some Novel Tetrahydroquinoline Derivatives Bearing Pyrazol and Hydrazide Moiety. Journal of Heterocyclic Chem 2020, 57, 2108–2120. [CrossRef]

- Gangapuram, M.; Eyunni, S.; Zhang, W.; Redda, K.K. Design and Synthesis of Tetrahydroisoquinoline Derivatives as Anti-Angiogenesis and Anti-Cancer Agents. ACAMC 2021, 21, 2505–2511. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Singh, R.K. Morpholine as Ubiquitous Pharmacophore in Medicinal Chemistry: Deep Insight into the Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR). Bioorganic Chemistry 2020, 96, 103578. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S.; Dey, R.; Bhatt, H.; Patel, B.; Patel, S.; Dixit, N.; Chaube, U. Designing of Target-specific N -substituted Tetrahydroquinoline Derivatives as Potent mTOR Inhibitors via Integrated Structure-guided Computational Approaches. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202303291. [CrossRef]

- Dey, R.; Shaw, S.; Bhatt, H.; Patel, B.; Yadav, R.; Chaube, U. Synthesis, Biological Screening, and Binding Mode Analysis of Some N-Substituted Tetrahydroquinoline Analogs as Apoptosis Inducers and Anticancer Agents. Journal of Molecular Structure 2024, 1318, 139330. [CrossRef]

- Chaube, U.J.; Rawal, R.; Jha, A.B.; Variya, B.; Bhatt, H.G. Design and Development of Tetrahydro-Quinoline Derivatives as Dual mTOR-C1/C2 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Lung Cancer. Bioorganic Chemistry 2021, 106, 104501. [CrossRef]

- Chhatbar, D.M.; Chaube, U.J.; Vyas, V.K.; Bhatt, H.G. CoMFA, CoMSIA, Topomer CoMFA, HQSAR, Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulations Study of Triazine Morpholino Derivatives as mTOR Inhibitors for the Treatment of Breast Cancer. Computational Biology and Chemistry 2019, 80, 351–363. [CrossRef]

- Chaube, U.; Bhatt, H. 3D-QSAR, Molecular Dynamics Simulations, and Molecular Docking Studies on Pyridoaminotropanes and Tetrahydroquinazoline as mTOR Inhibitors. Mol Divers 2017, 21, 741–759. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Rudge, D.G.; Koos, J.D.; Vaidialingam, B.; Yang, H.J.; Pavletich, N.P. mTOR Kinase Structure, Mechanism and Regulation. Nature 2013, 497, 217–223. [CrossRef]

- Chaube, U.; Chhatbar, D.; Bhatt, H. 3D-QSAR, Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Molecular Docking Studies of Benzoxazepine Moiety as mTOR Inhibitor for the Treatment of Lung Cancer. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2016, 26, 864–874. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Chapuis, N.; Bardet, V.; Tamburini, J.; Gallay, N.; Willems, L.; Knight, Z.A.; Shokat, K.M.; Azar, N.; Viguié, F.; et al. PI-103, a Dual Inhibitor of Class IA Phosphatidylinositide 3-Kinase and mTOR, Has Antileukemic Activity in AML. Leukemia 2008, 22, 1698–1706. [CrossRef]

- Guichard, S.M.; Curwen, J.; Bihani, T.; D’Cruz, C.M.; Yates, J.W.T.; Grondine, M.; Howard, Z.; Davies, B.R.; Bigley, G.; Klinowska, T.; et al. AZD2014, an Inhibitor of mTORC1 and mTORC2, Is Highly Effective in ER+ Breast Cancer When Administered Using Intermittent or Continuous Schedules. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2015, 14, 2508–2518. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Teng, B.; Wen, L.; Feng, Q.; Wang, H.; Li, N.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Z. mTOR Inhibitor AZD8055 Inhibits Proliferation and Induces Apoptosis in Laryngeal Carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Med 2014, 7, 337–347.

- Shi, F.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Wu, L.; Jiang, H.; Wu, Q.; Liu, T.; Lou, M.; Wu, H. The Dual PI3K/mTOR Inhibitor Dactolisib Elicits Anti-Tumor Activity in Vitro and in Vivo. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 706–717. [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.F.M.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Fernandes, P.A.; Silva, A.M.S. Evolution of the Quinoline Scaffold for the Treatment of Leishmaniasis: A Structural Perspective. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 285. [CrossRef]

- Van Voorhis, W.C.; Rivas, K.L.; Bendale, P.; Nallan, L.; Hornéy, C.; Barrett, L.K.; Bauer, K.D.; Smart, B.P.; Ankala, S.; Hucke, O.; et al. Efficacy, Pharmacokinetics, and Metabolism of Tetrahydroquinoline Inhibitors of Plasmodium Falciparum Protein Farnesyltransferase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007, 51, 3659–3671. [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.S.; Mitra, K.; Akter, S.; Ramproshad, S.; Mondal, B.; Khan, I.N.; Islam, M.T.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Calina, D.; Cho, W.C. Recent Advances and Limitations of mTOR Inhibitors in the Treatment of Cancer. Cancer Cell Int 2022, 22, 284. [CrossRef]

- Thaker, A.; Patel, S.; Dey, R.; Shaw, S.; Patel, B.; Bhatt, H.; Chaube, U.J. Advancements in mTOR Inhibitors for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Mechanisms, Efficacy, and Future Perspectives. Synlett 2024, a-2507-3598. [CrossRef]

- Chaube, U.; Dey, R.; Shaw, S.; Patel, B.D.; Bhatt, H.G. Tetrahydroquinoline: An Efficient Scaffold as mTOR Inhibitor for the Treatment of Lung Cancer. Future Medicinal Chemistry 2022, 14, 1789–1809. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Chan, D.; Chung, P.Y.; Wang, Y.; Chan, A.S.C.; Law, S.; Lam, K.H.; Tang, J.C.O. The Anticancer Effect of a Novel Quinoline Derivative 91b1 through Downregulation of Lumican. IJMS 2022, 23, 13181. [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.-F.; Liu, X.-J.; Yuan, X.-Y.; Liu, W.-B.; Li, Y.-R.; Yu, G.-X.; Tian, X.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Song, J.; Li, W.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Anticancer Activity Studies of Novel Quinoline-Chalcone Derivatives. Molecules 2021, 26, 4899. [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.-M.; Hu, X.-R.; Xu, W.-M. 7-Nitro-1,2,3,4-Tetrahydroquinoline. Acta Crystallogr E Struct Rep Online 2006, 62, o62–o63. [CrossRef]

- Kaye, B.; Woolhouse, N.M. The Metabolism of a New Schistosomicide 2-Isopropylaminomethyl-6-Methyl-7-Nitro-1,2,3,4-Tetrahydroquinoline (UK 3883). Xenobiotica 1972, 2, 169–178. [CrossRef]

- Bachmeier, B.; Fichtner, I.; Killian, P.H.; Kronski, E.; Pfeffer, U.; Efferth, T. Development of Resistance towards Artesunate in MDA-MB-231 Human Breast Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20550. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, A.; Schneider, B.K.; White, C.W. Cholesterol Interferes with the MTT Assay in Human Epithelial-Like (A549) and Endothelial (HLMVE and HCAE) Cells. Int J Toxicol 2006, 25, 17–23. [CrossRef]

- Senthilraja, P.; Kathiresan, K. In Vitro Cytotoxicity MTT Assay in Vero, HepG2 and MCF -7 Cell Lines Study of Marine Yeast. J App Pharm Sci 2015, 080–084. [CrossRef]

- Norrby, E.; Marusyk, H.; Örvell, C. Morphogenesis of Respiratory Syncytial Virus in a Green Monkey Kidney Cell Line (Vero). J Virol 1970, 6, 237–242. [CrossRef]

- Sekar, T.; Grace, B.E.; N., K.; Nivetha K.; Parveen, M.H.; Mohan, G.C. Comparative Analysis of MEM, RPMI 1640 Media on Rabies Virus Propagation in Vero Cells and Virus Quantification by FAT. AJOB 2023, 19, 46–53. [CrossRef]

- Al Saqr, A.; Khafagy, E.-S.; Aldawsari, M.F.; Almansour, K.; Abu Lila, A.S. Screening of Apoptosis Pathway-Mediated Anti-Proliferative Activity of the Phytochemical Compound Furanodienone against Human Non-Small Lung Cancer A-549 Cells. Life 2022, 12, 114. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Nagarajan, A.; Uchil, P.D. Analysis of Cell Viability by the MTT Assay. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2018, 2018, pdb.prot095505. [CrossRef]

- Bossy-Wetzel, E.; Green, D.R. Detection of Apoptosis by Annexin V Labeling. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier, 2000; Vol. 322, pp. 15–18 ISBN 978-0-12-182223-1.

- Chen, S.; Cheng, A.-C.; Wang, M.-S.; Peng, X. Detection of Apoptosis Induced by New Type Gosling Viral Enteritis Virus in Vitro through Fluorescein Annexin V-FITC/PI Double Labeling. WJG 2008, 14, 2174. [CrossRef]

- Miller, E. Apoptosis Measurement by Annexin V Staining. In Cancer Cell Culture; Humana Press: New Jersey, 2003; Vol. 88, pp. 191–202 ISBN 978-1-59259-406-1.

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization, and Multithreading. J Comput Chem 2010, 31, 455–461. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Buie, C.; Reay, A.; Vaughn, M.W.; Cheng, K.H. Molecular Dynamics Simulations Reveal the Protective Role of Cholesterol in β-Amyloid Protein-Induced Membrane Disruptions in Neuronal Membrane Mimics. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 9795–9812. [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High Performance Molecular Simulations through Multi-Level Parallelism from Laptops to Supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. [CrossRef]

- Páll, S.; Abraham, M.J.; Kutzner, C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. Tackling Exascale Software Challenges in Molecular Dynamics Simulations with GROMACS. In Solving Software Challenges for Exascale; Markidis, S., Laure, E., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; Vol. 8759, pp. 3–27 ISBN 978-3-319-15975-1.

| ||||||||

| Sl No | Compound No | X | Y | R |

A549 (IC50 µM) |

MCF-7 (IC50 µM) |

MDA-MB-231 (IC50 µM) |

VERO (IC50 µM) |

| 1 | 5-FU | - | - | - | 0.28 ± 0.008 |

0.72 ± 0.03 |

3.39 ± 0.37 |

>25 |

| 2 | Everolimus | - | - | - | 0.09 ± 0.01 |

5.86 ± 0.07 |

7.76 ± 0.37 |

>25 |

| 3 | 10a | O | CH | 4-(trifluoromethoxy) | 1.06 ± 0.02 |

4.34 ± 0.12 |

8.16 ± 0.33 |

>25 |

| 4 | 10b | CH2 | CH | 4-(trifluoromethoxy) | 4.72 ± 0.11 |

>25 | 6.37 ± 0.19 |

9.82 ± 0.08 |

| 5 | 10c | O | N | 3,5-difluoro | 3.73 ± 0.17 |

8.31 ± 0.43 |

>25 | >25 |

| 6 | 10d | O | N | 3-fluoro-5-(trifluoromethyl) |

0.062 ± 0.01 |

0.58 ± 0.11 |

1.003 ± 0.008 |

>25 |

| 7 | 10e | O | N | 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl) |

0.033 ± 0.003 |

2.89 ± 0.013 |

0.63 ± 0.02 |

8.86 ± 0.03 |

| 8 | 10f | CH2 | N | 3,5-difluoro | >25 | 4.47 ± 0.013 |

>25 | >25 |

| 9 | 10g | CH2 | N | 3-fluoro-5-(trifluoromethyl) | 0.68 ± 0.13 |

2.50 ± 0.16 |

>25 | >25 |

| 10 | 10h | CH2 | N | 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl) | 3.36 ± 0.71 |

0.087 ± 0.007 |

1.29 ± 0.032 |

>25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).