Submitted:

10 August 2025

Posted:

12 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Highlights:

- •

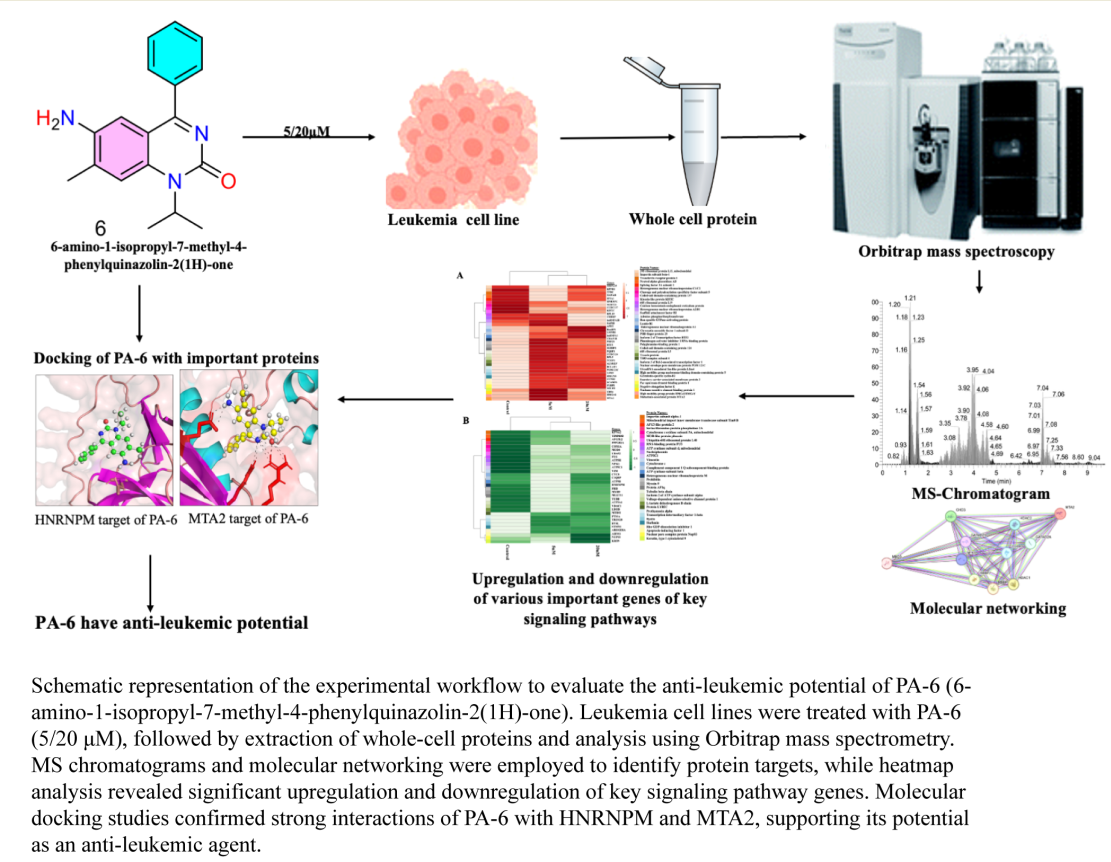

- PA-6, a proquazone analog, was synthesized and investigated for its therapeutic efficacy against K562 leukemia cells.

- •

- Orbitrap mass spectrometry–based global proteomics and computational pharmacokinetics were employed to elucidate the PA-6’s mechanism of action.

- •

- PA-6 demonstrated optimal molecular weight, absorption, and blood-brain barrier permeability, underscoring its potential as a therapeutic agent.

- •

- Molecular docking studies identified MTA2 and HNRNPM, a key regulator of RNA metabolism and chromatin remodeling, as potential PA-6 targets.

- •

- In vitro cytotoxicity assays confirmed a dose-dependent inhibition of leukemia cell proliferation, attributed to a significant reduction in K562 cell viability through suppression of key signaling pathways.

- •

- PA-6 treatment induced significant alterations in apoptosis, RNA processing, and cell cycle regulation, further substantiating its anticancer potential.

- •

- These findings establish PA-6 as a promising, low-toxicity, effective anti-leukemic agent, warranting further preclinical investigation.

INTRODUCTION

RESULTS

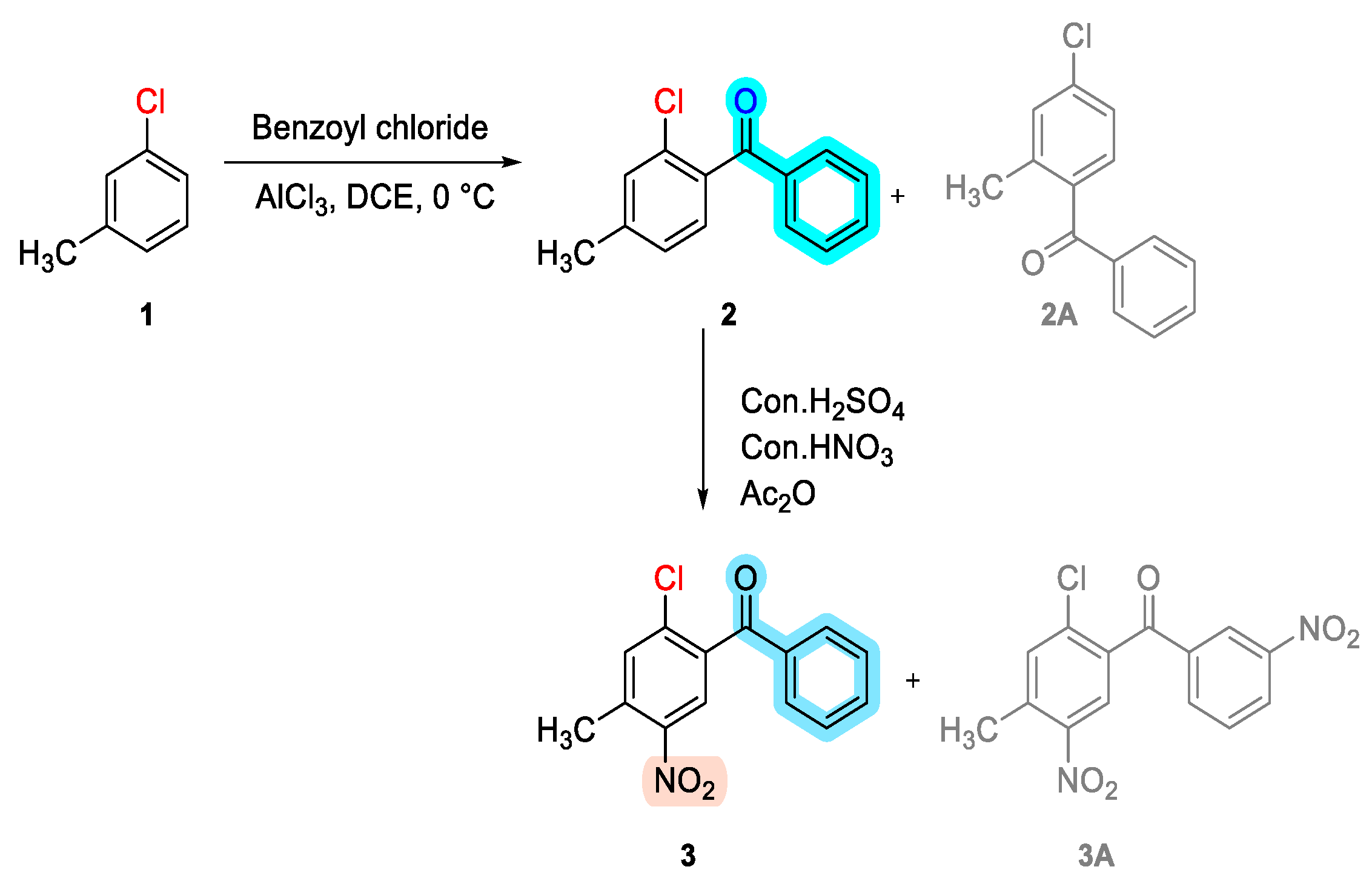

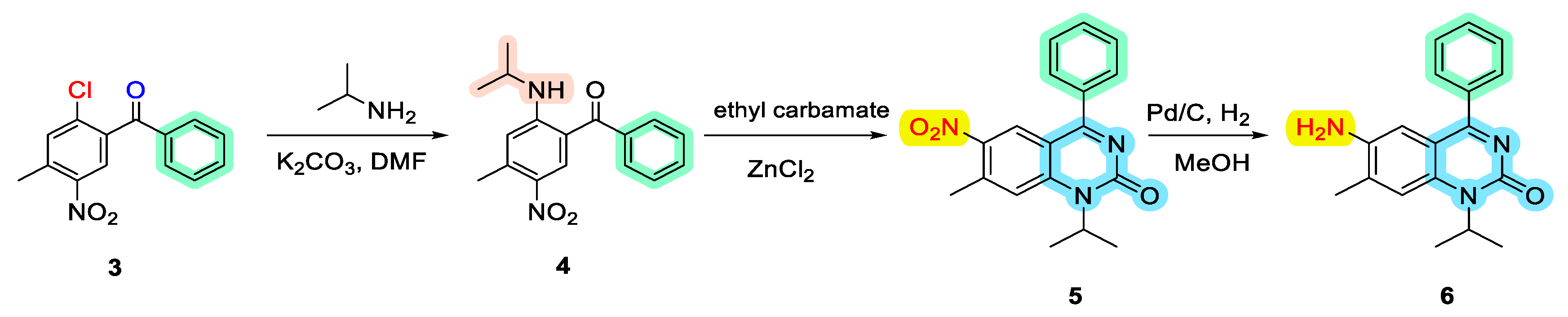

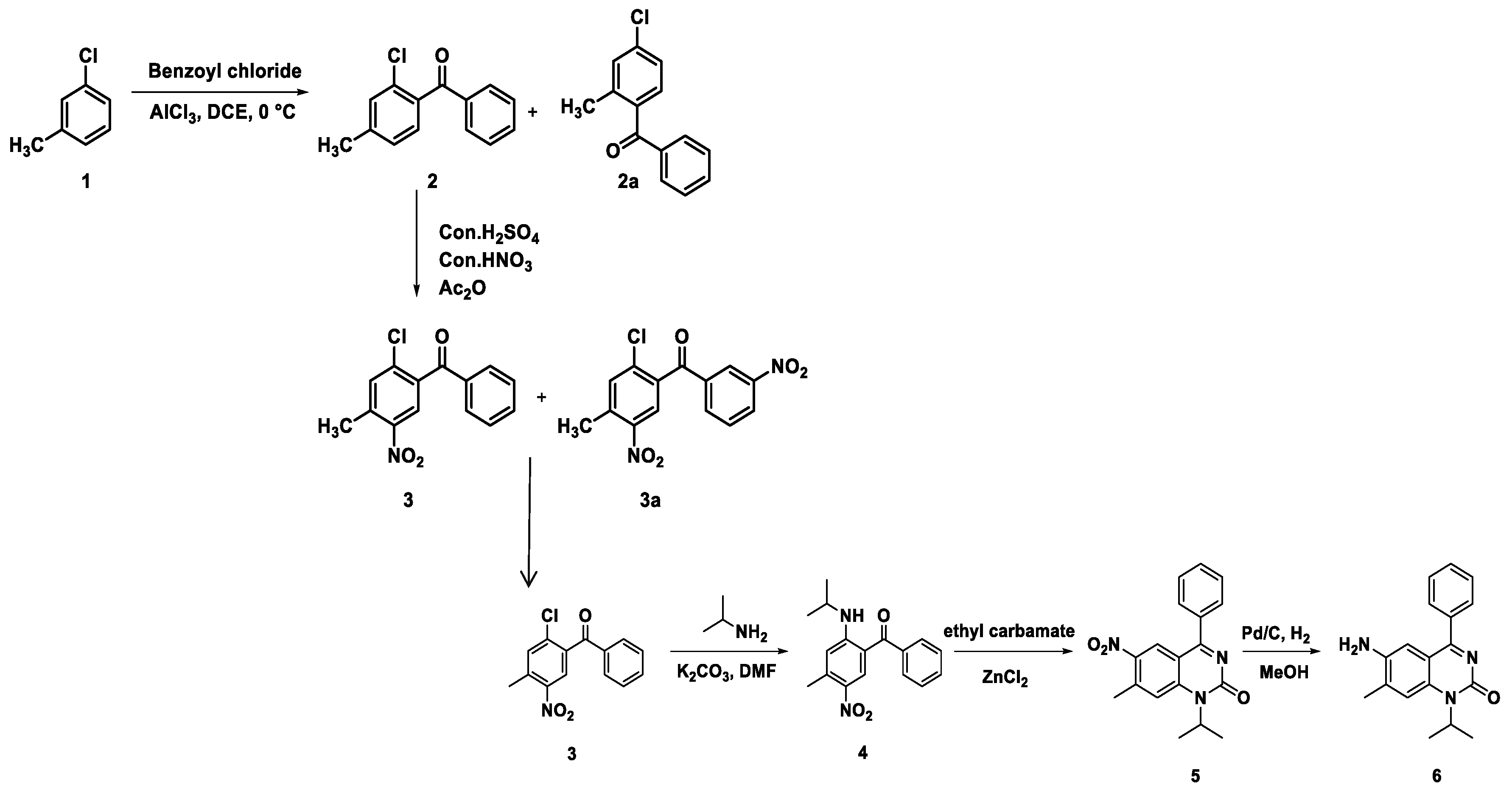

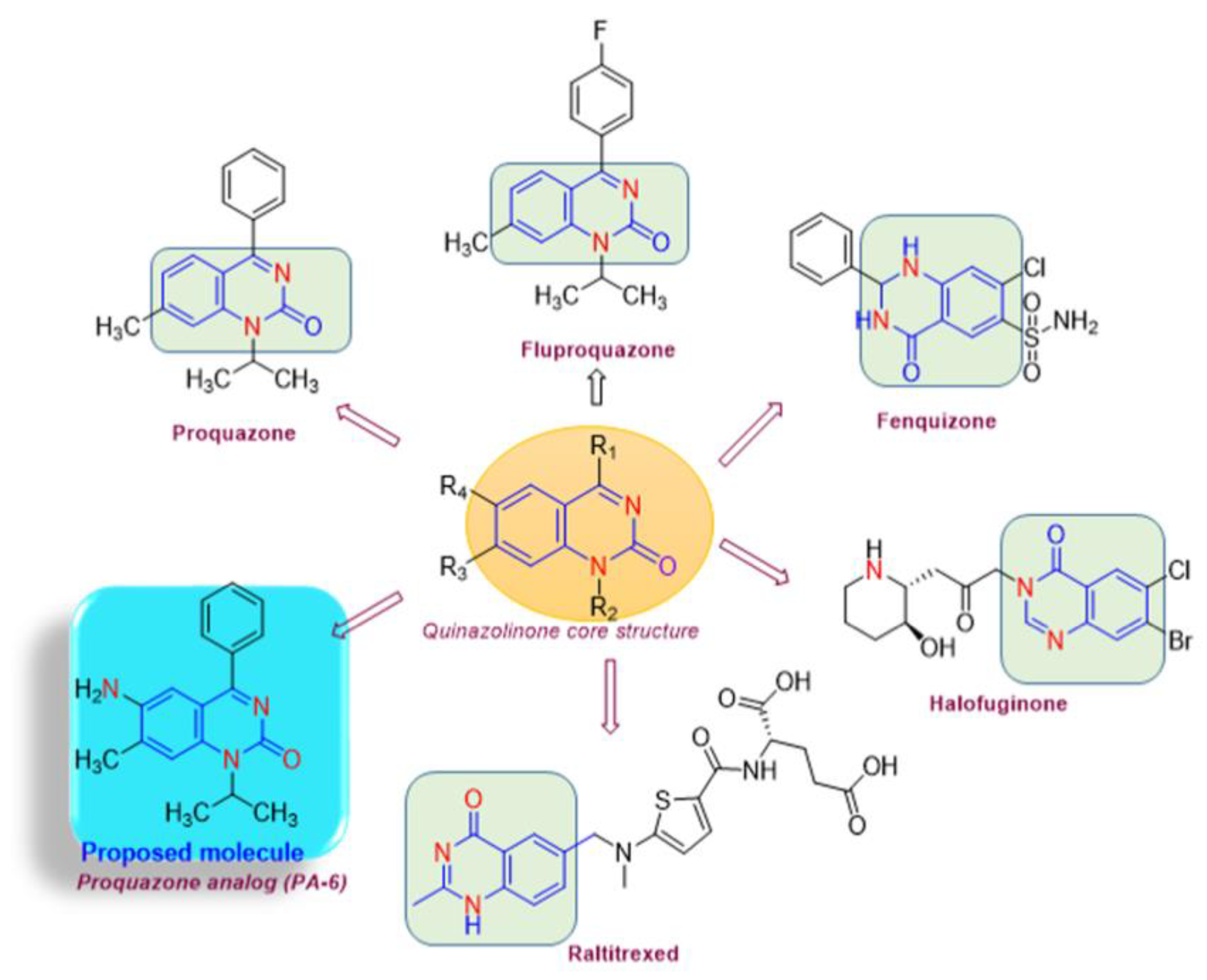

Chemistry of Drug Synthesis

Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) Analysis

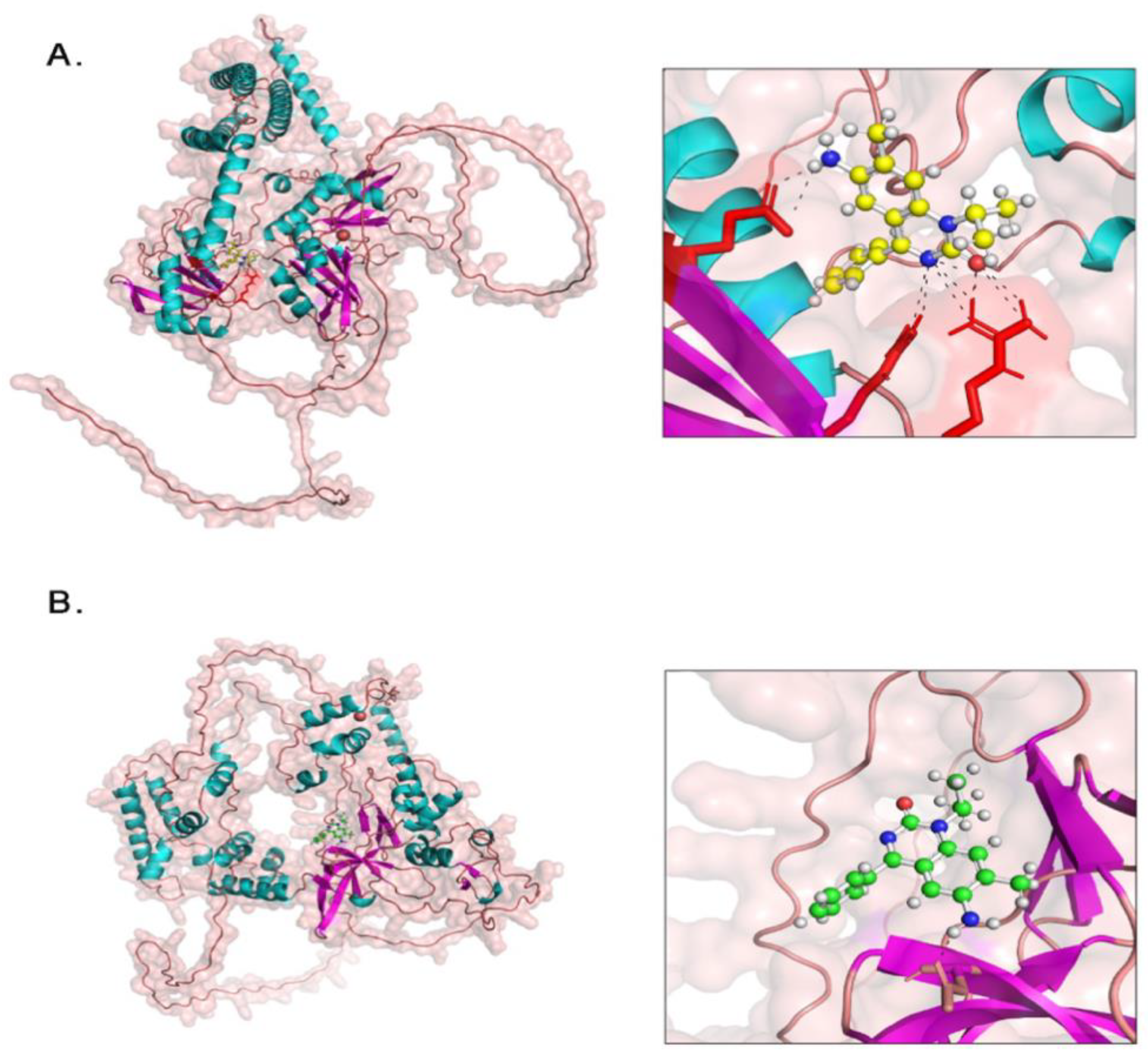

Docking Analysis

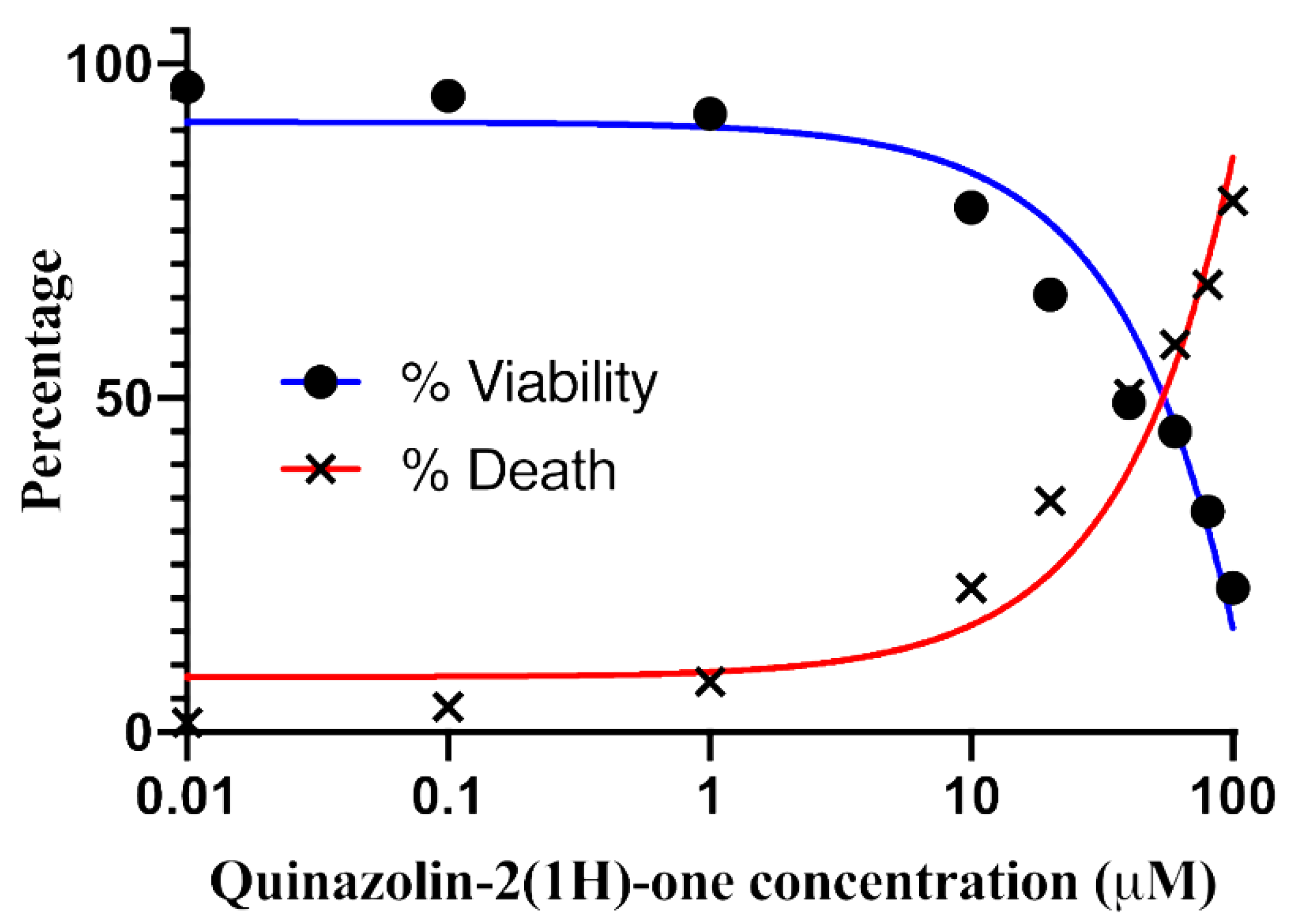

Proquazone Analog (PA-6) Suppresses the Proliferation of K562 Cancer Cell Lines

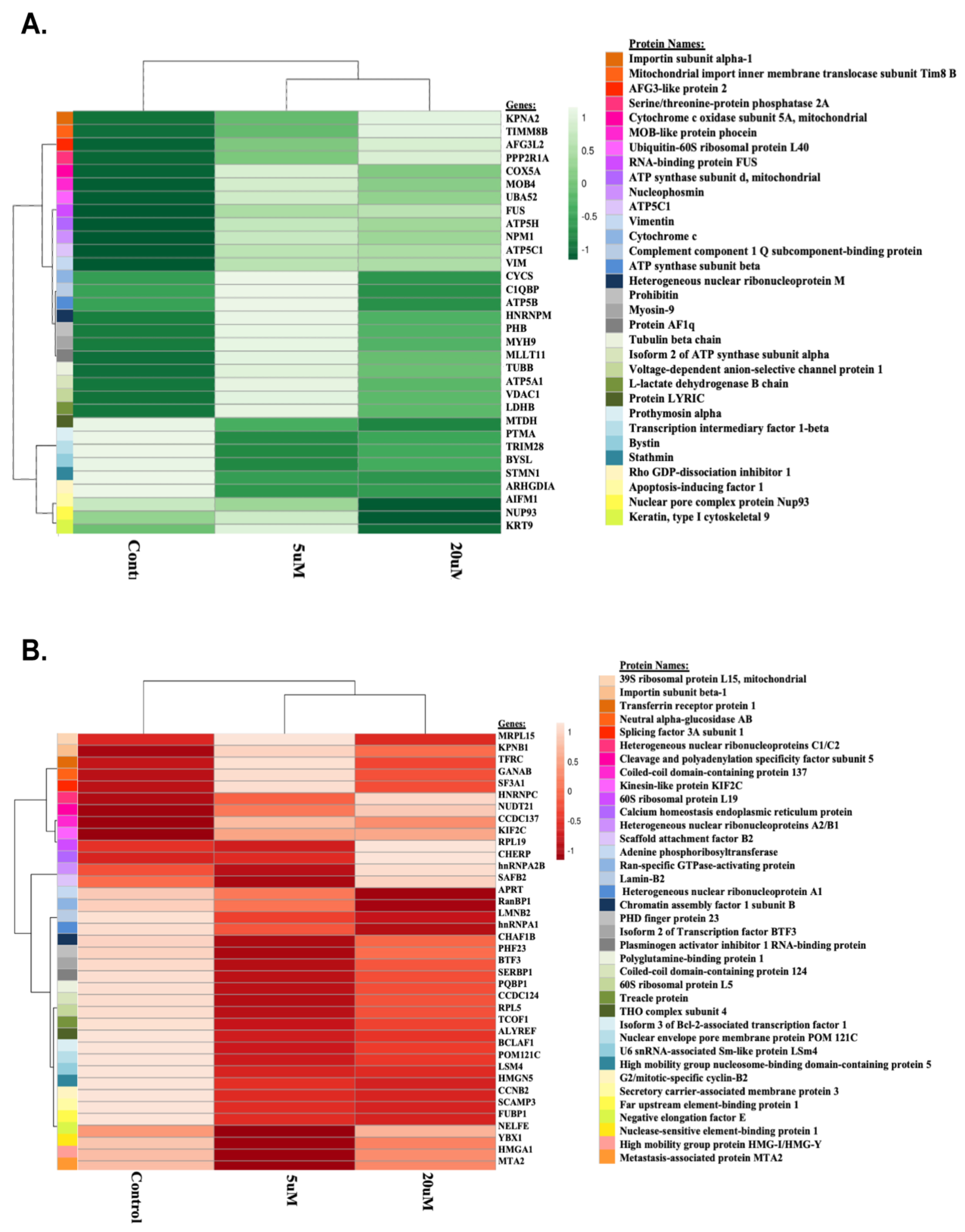

Proteome Profiling of K562 Cell Lines

Differentially Expressed Proteins Between Conditions

Homology Among Distinct Proteins

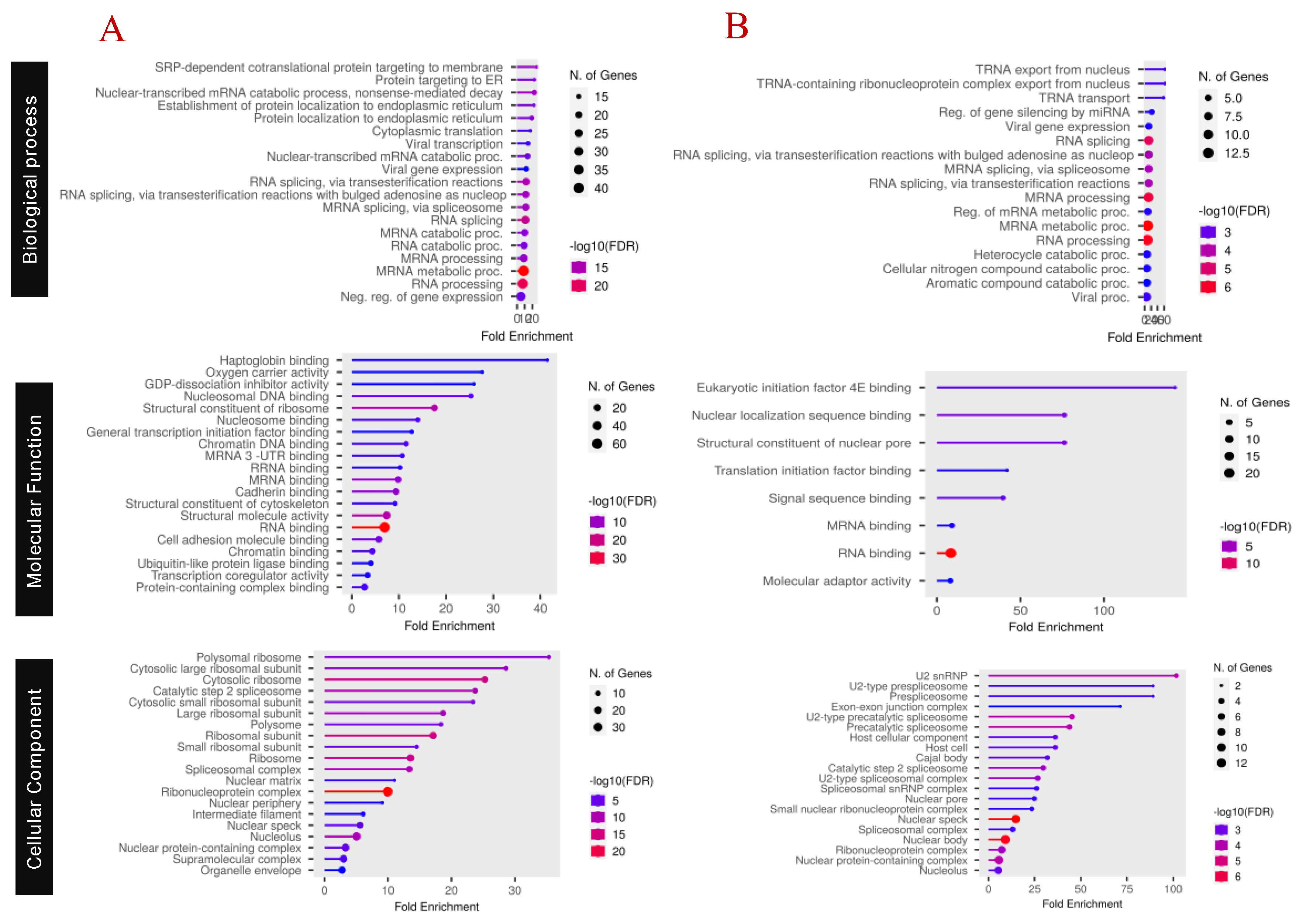

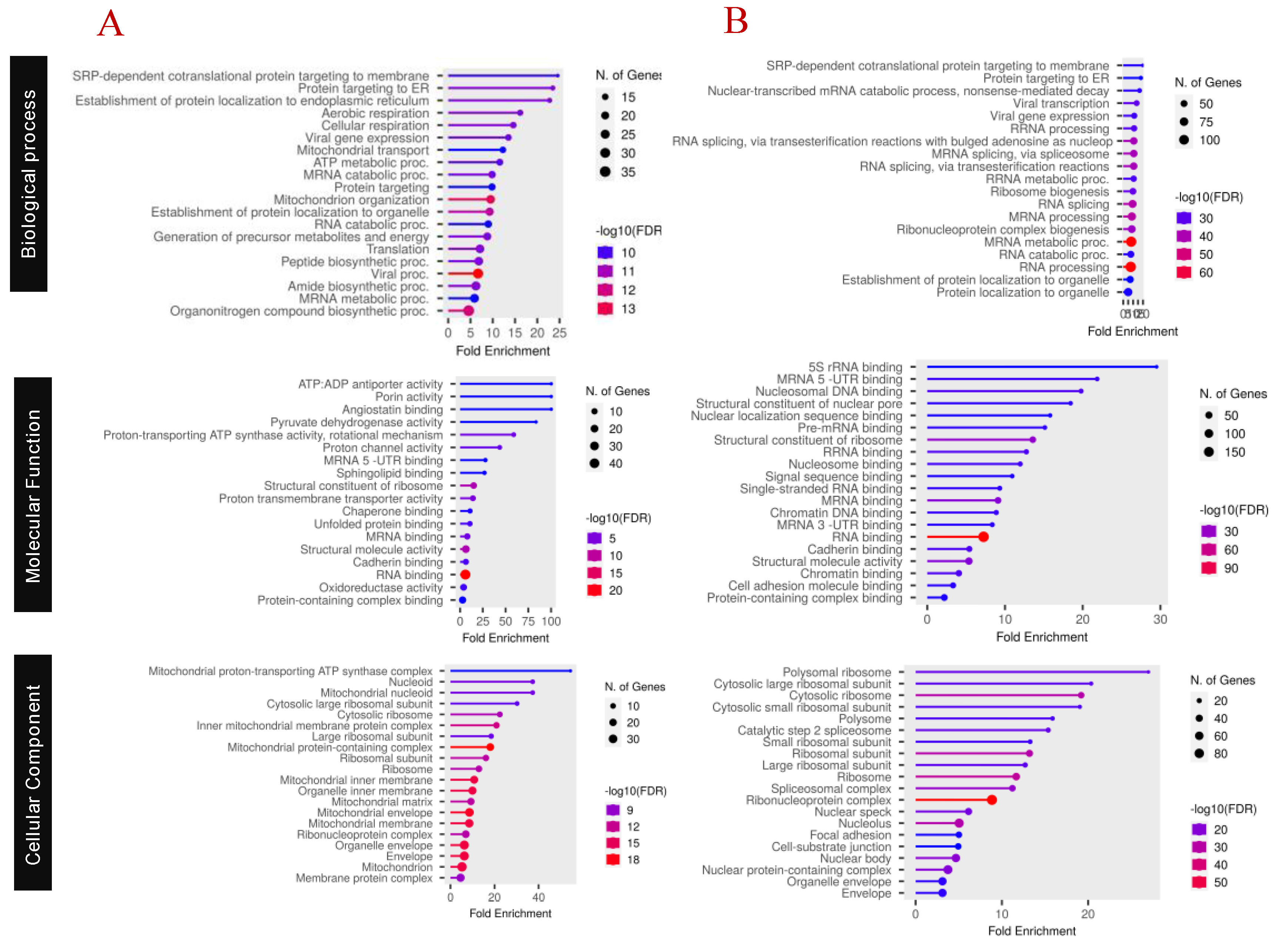

Functional Characterization of Proteins

Pathway Analysis

DISCUSSION

MATERIALS AND METHODS

- Synthesis of (2-chloro-4-methylphenyl)(phenyl)methanone (2):

- Synthesis of (2-chloro-4-methyl-5-nitrophenyl)(phenyl)methanone (3):

- Synthesis of (2-(isopropylamino)-4-methyl-5-nitrophenyl)(phenyl)methanone (4):

- Synthesis of 1-isopropyl-7-methyl-6-nitro-4-phenylquinazolin-2(1H)-one (5):

- Synthesis of 6-amino-1-isopropyl-7-methyl-4-phenylquinazolin-2(1H)-one (6):

Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) Analysis of PA-6

Molecular Docking of PA-6 with MTA2 and HNRNPM

Cell lines and Resources

Cytotoxicity Assay

Isolation of Proteins from Treated K562 Cell Lines

Insolution Digestion (ISD) of Isolated Proteins

Peptide Desalting and ESI-LC Analysis

Mass Spectrometry Acquisition

Data Analysis

Functional Annotations

CONCLUSION

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karthikeyan, S.; Grishina, M.; Kandasamy, S.; Mangaiyarkarasi, R.; Ramamoorthi, A.; Chinnathambi, S.; Pandian, G.N.; Kennedy, L.J. A review on medicinally important heterocyclic compounds and importance of biophysical approach of underlying the insight mechanism in biological environment. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 41, 14599–14619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auti, P.S.; George, G.; Paul, A.T. Recent advances in the pharmacological diversification of quinazoline/quinazolinone hybrids. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 41353–41392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniolli, G.; Lima, C.S.P.; Coelho, F. Recent advances in the investigation of the quinazoline nucleus and derivatives with potential anticancer activities. Futur. Med. Chem. 2025, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mphahlele, M.J. A Review on the Synthesis and Chemical Transformation of Quinazoline 3-Oxides. Molecules 2022, 27, 7985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatadi, S.; Lakshmi, T.V.; Nanduri, S. 4(3H)-Quinazolinone derivatives: Promising antibacterial drug leads. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 170, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, Q.; Lei, X.; Wu, M.; Guo, S.; Yi, D.; Li, Q.; Ma, L.; et al. Quinoline and Quinazoline Derivatives Inhibit Viral RNA Synthesis by SARS-CoV-2 RdRp. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 1535–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Sarma, D. Recent advances in the synthesis of Quinazoline analogues as Anti-TB agents. Tuberculosis 2020, 124, 101986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, F.; Jafari, E.; Hakimelahi, G.H.; Khajouei, M.R.; Jalali, M.; Khodarahmi, G.A. Antibacterial, antifungal and cytotoxic evaluation of some new quinazolinone derivatives. 2012, 7, 87–94.

- Jafari, E.; Khajouei, M.R.; Hassanzadeh, F.; Hakimelahi, G.H.; Khodarahmi, G.A. Quinazolinone and quinazoline derivatives: recent structures with potent antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities. 2016, 11, 1–14.

- Mehndiratta, S.; Sapra, S.; Singh, G.; Singh, M.; Nepali, K. Quinazolines as Apoptosis Inducers and Inhibitors: A Review of Patent Literature. Recent Patents Anti-Cancer Drug Discov. 2016, 11, 2–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, O.J.; Shyamasundar, S.; Matsumoto, K.; Dheen, S.T.; Yip, G.W.; Bay, B.H. C1QBP Mediates Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation and Growth via Multiple Potential Signalling Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, R.; Zhao, W.; Xiao, S.; Lu, Y. A Signature of Three Apoptosis-Related Genes Predicts Overall Survival in Breast Cancer. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 863035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, N.; Dasgupta, A.; Sudsakorn, S.; Fretland, J.; Mavroudis, P.D. Machine Learning guided early drug discovery of small molecules. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 2209–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Hung, T.-W.; Su, S.-C.; Lin, C.-L.; Yang, S.-F.; Lee, C.-C.; Yeh, C.-F.; Hsieh, Y.-H.; Tsai, J.-P. MTA2 as a Potential Biomarker and Its Involvement in Metastatic Progression of Human Renal Cancer by miR-133b Targeting MMP-9. Cancers 2019, 11, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin CL, Ying TH, Yang SF, Chiou HL, Chen YS, Kao SH, et al. MTA2 silencing attenuates the metastatic potential of cervical cancer cells by inhibiting AP1-mediated MMP12 expression via the ASK1/MEK3/p38/YB1 axis. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(5):451.

- Passacantilli, I.; Frisone, P.; De Paola, E.; Fidaleo, M.; Paronetto, M.P. hnRNPM guides an alternative splicing program in response to inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in Ewing sarcoma cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 12270–12284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Dai, Q.; Su, X.; Fu, J.; Feng, X.; Peng, J. Role of PI3K/AKT pathway in cancer: the framework of malignant behavior. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 4587–4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S.; Doshi, A.; Luckett-Chastain, L.; Ihnat, M.; Hamel, E.; Mooberry, S.L.; Gangjee, A. Potential of substituted quinazolines to interact with multiple targets in the treatment of cancer. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2021, 35, 116061–116061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, A.K.; Muthiyan, R.; Mondal, S.; Mahanta, N.; Bhattacharya, D.; Ponraj, P.; Muniswamy, K.; Kundu, A.; Kundu, M.S.; Sunder, J.; et al. A Natural Quinazoline Derivative from Marine Sponge Hyrtios erectus Induces Apoptosis of Breast Cancer Cells via ROS Production and Intrinsic or Extrinsic Apoptosis Pathways. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott JR, Patel PA, Howes JE, Akan DT, Kennedy JP, Burns MC, et al. Discovery of Quinazolines That Activate SOS1-Mediated Nucleotide Exchange on RAS. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2018;9(9):941-6.

- Patni, A.P.; Harishankar, M.K.; Joseph, J.P.; Sreeshma, B.; Jayaraj, R.; Devi, A. Comprehending the crosstalk between Notch, Wnt and Hedgehog signaling pathways in oral squamous cell carcinoma - clinical implications. Cell. Oncol. 2021, 44, 473–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha HA, Chiang JH, Tsai FJ, Bau DT, Juan YN, Lo YH, et al. Novel quinazolinone MJ-33 induces AKT/mTOR-mediated autophagy-associated apoptosis in 5FU-resistant colorectal cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2021;45(2):680-92.

- Hour, M.-J.; Tsai, S.-C.; Wu, H.-C.; Lin, M.-W.; Chung, J.-G.; Wu, J.-B.; Chiang, J.-H.; Tsuzuki, M.; Yang, J.-S. Antitumor effects of the novel quinazolinone MJ-33: Inhibition of metastasis through the MAPK, AKT, NF-κB and AP-1 signaling pathways in DU145 human prostate cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2012, 41, 1513–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu YJ, Hour MJ, Jin YA, Lu CC, Tsai FJ, Chen TL, et al. Disruption of IGF-1R signaling by a novel quinazoline derivative, HMJ-30, inhibits invasiveness and reverses epithelial-mesenchymal transition in osteosarcoma U-2 OS cells. Int J Oncol. 2018;52(5):1465-78.

- Lu CC, Yang JS, Chiang JH, Hour MJ, Amagaya S, Lu KW, et al. Inhibition of invasion and migration by newly synthesized quinazolinone MJ-29 in human oral cancer CAL 27 cells through suppression of MMP-2/9 expression and combined down-regulation of MAPK and AKT signaling. Anticancer Res. 2012;32(7):2895-903.

- Singh, R.R.; Kumar, R. MTA Family of Transcriptional Metaregulators in Mammary Gland Morphogenesis and Breast Cancer. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia 2007, 12, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, I.; Takaha, N.; Nakamura, T.; Hongo, F.; Mikami, K.; Kamoi, K.; Okihara, K.; Kawauchi, A.; Miki, T. High mobility group protein AT-hook 1 (HMGA1) is associated with the development of androgen independence in prostate cancer cells. Prostate 2011, 72, 1124–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Ji, J.; Cai, Q.; Shi, M.; Chen, X.; Yu, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, J. MTA2 promotes gastric cancer cells invasion and is transcriptionally regulated by Sp1. Mol. Cancer 2013, 12, 102–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.-W.; Fan, Y.-F.; Li, J.; Jiang, X.-X. MTA2 expression is a novel prognostic marker for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Tumor Biol. 2013, 34, 1553–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Wang, Y.; Guo, T.; Yu, W.; Li, J.; Tang, Z.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; et al. YBX1 regulates tumor growth via CDC25a pathway in human lung adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 82139–82157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Su, R.; Jia, H.; Birková, A. Cyclin B2 (CCNB2) Stimulates the Proliferation of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) Cells In Vitro and In Vivo. Dis. Markers 2021, 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnerch, D.; Yalcintepe, J.; Schmidts, A.; Becker, H.; Follo, M.; Engelhardt, M.; Wäsch, R. Cell cycle control in acute myeloid leukemia. . 2012, 2, 508–28. [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Li Y, Ren X, Zhang Y, Yang Z, Qi C. A novel quinazoline-based analog induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human A549 lung cancer cells via a ROS-dependent mechanism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;486(2):314-20.

- Li, M.-J.; Yan, S.-B.; Chen, G.; Li, G.-S.; Yang, Y.; Wei, T.; He, D.-S.; Yang, Z.; Cen, G.-Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Upregulation of CCNB2 and Its Perspective Mechanisms in Cerebral Ischemic Stroke and All Subtypes of Lung Cancer: A Comprehensive Study. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 854540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rensen, W.M.; Roscioli, E.; Tedeschi, A.; Mangiacasale, R.; Ciciarello, M.; A Di Gioia, S.; Lavia, P. RanBP1 downregulation sensitizes cancer cells to taxol in a caspase-3-dependent manner. Oncogene 2009, 28, 1748–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Meng, P.; Bao, Y.; Tao, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Bu, Y.; Zhu, J. Cell cycle dysregulation with overexpression of KIF2C/MCAK is a critical event in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Genes Dis. 2023, 10, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgado-Palacin, I.; Day, A.; Murga, M.; Lafarga, V.; Anton, M.E.; Tubbs, A.; Chen, H.-T.; Ergen, A.V.; Anderson, R.; Bhandoola, A.; et al. Targeting the kinase activities of ATR and ATM exhibits antitumoral activity in mouse models of MLL -rearranged AML. Sci. Signal. 2016, 9, ra91–ra91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, C.; Kharas, M.G. RNA Regulators in Leukemia and Lymphoma. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2019, 10, a034967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Shang, X.; Xin, L. Cyclin B2 impairs the p53 signaling in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Saha, U.; Paira, S.; Das, B. Nuclear mRNA Surveillance Mechanisms: Function and Links to Human Disease. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 1993–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagar, P.; Islam, R.; Rahman, M.A. Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay as a Mediator of Tumorigenesis. Genes 2023, 14, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green MR, and Joseph Sambrook.. Molecular Cloning : A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 2012;4th ed.

| Parameter | Value/Prediction | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight (MW) | ~294 g/mol | Within the optimal range for drug candidates |

| LogP (Lipophilicity) | ~2.5 | Balanced hydrophilicity/lipophilicity promotes membrane permeability and solubility |

| Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD) | ~2 | Sufficient for specific interactions while maintaining permeability |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA) | ~4 | Favors interactions with biological targets without excessive polarity |

| Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA) | ~70 Ų | Supports efficient intestinal absorption and favorable oral bioavailability |

| Rotatable Bonds | ~2 | Indicates a relatively rigid structure, which is beneficial for receptor binding |

| Gastrointestinal (GI) Absorption | High | Predicts efficient uptake upon oral administration |

| Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB) Permeability | Low | Reduces the likelihood of central nervous system side effects |

| P-glycoprotein Substrate | No | Not likely to be actively effluxed, favoring higher intracellular retention |

| Water Solubility (LogS) | ~–4.17 | Moderate solubility ensuring adequate systemic distribution |

| Cytochrome P450 Interaction | Potential inhibition of CYP2C9, CYP2C19 | May require further in vitro studies to assess metabolic stability and drug–drug interaction risk |

| Drug-likeness | Compliant with Lipinski’s and Veber’s rules | Suggests favorable oral bioavailability and overall drug candidate potential |

| Bioavailability Score | ~0.55 (predicted) | Indicates a moderate likelihood of achieving sufficient systemic exposure |

| Synthetic Accessibility | Moderate (score ~3.0) | Reflects a balance between synthetic complexity and feasibility |

| Name | Score | T. Energy | I. Energy | vdW Energy | Electrostatic Energy | Amino Acid Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HNRNPM | -7.296 | 52.247 | -22.077 | -14.406 | -7.671 | Glu102, Arg70, Arg72 |

| MTA2 | -7.5 | 55.157 | -21.627 | -16.377 | -5.25 | Asp10 |

| Condition | K-means | Cluster gene count | Gene name |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Treatment 5 µM |

1 | 13 | AFG3L2, C1QBP, CYCS, KPNA2, PHB, PHB2, TIMM8B, VDAC1, VDAC2 |

| 2 | 10 | AIFM1, APOOL, ATP5A1, ATP5B, ATP5C1, ATP5H, COX5A, DLAT, HSPA9, LDHB, MDH2, MYH9, PNPT1, SHMT2, SLC25A5, SLC25A6, UQCRC1, UQCRC2 | |

| 3 | 13 | ALB, CANX, ENO1, FDXR, GANAB, HSPA5, HSPD1, LMNA, NUP93, PPIF, SEC22B, RPN1, SNAP29 | |

| 4 | 13 | EXOSC4, FAM136A, GSE1, MLLT11, MOB4, MRPL48, MRPS5, RPL12, RPL7, RPS12, RPS17, RPS7, UBA52 | |

| 5 | 10 | ERH, FUS, HNRNPM, KHDRBS1, NPM1, PLRG1, SF3A1, TFRC, VIM, XRCC6 | |

|

Treatment 20 µM |

1 | 10 | ATP50, ATP6V1F, ATP6V1G2, CCDC86, MRPL34, NDUFAF2, NDUFV3, SERPINH1, SURF6, TOR1AIP1 |

| 2 | 12 | CCDC137, CCNB1, CCNB2, H1FX, H2AFV, KRT9, MBD3, PPP2R1A, PTMA, STMN1, TPM3, TUBB | |

| 3 | 25 | BCLAF1, CLTA, DDX17, DDX5, FUBP1, HNRNPA3, HNRNPC, HNRNPF, HNRNPU, LRRC59, MPC1, NONO, PABPN1, PNN, PPP1R2, RALY, RBM14, RBMX, SART1, SFPQ, SNW1, YBX1, SRSF3, SRSF5, TRIM28 | |

| 4 | 14 | AHNAK, ARHGDIA, DDRGK1, EEF1D, EEF1E1, EFHD2, GRPEL1, KRT2, KRT8, MTDH, PRKCSH, PYCR1, RANBP1, SCAMP3 | |

| 5 | 19 | APRT, BYSL, BTF3, CWC15, EDF1, HSP90AB1, MRPL15, MRPL16, RPL19, RPL26, RPL31, RPL4, RPS10, RPS15A, RPS16, RPS26, RPS9, SERBP1, WBP11 | |

| Treatment 5 µM | 1 | 47 | AARS2, AHNAK, ANP32A, ANXA1, ARHGDIA, ARHGEF2, CAT, CCNB1, CCDC86, CCT2, CCT6A, CD2AP, CFL1, DKC1, EDF1, EEF1E1, FEN1, G3BP1, GRPEL1, HIST2H2AC, HIST2H2BE HSP90AA1, HSP90AB1, HSPB1, HSPE1, KRT8, KRT9, LMNA, MCL1, MIA3, PABPN1, PAICS, PPP1R12A, PPP2R1A, PRRC2A, SENP3, PTMA, SERPINH1, STMN1, TMSB10, TMSB4X, TPI1, TPM3, TUBA1A, TUBB, VCP, YBX3 |

| 2 | 77 | APRT, CCDC124, BTF3, CCDC137, CCNB2, CHAF1B, CHAMP1, CHMP4B, EEF1A1, EEF1D, EEF2, EMD, EXOSC3, FAU, FTSJ3, H1FX, GLTSCR2, H2AFV, HIST1H1B, HIST1H1D, HIST1H1C, HIST1H1E HMGA1, HN1, HMGN5, HP1BP3, INCENP, KIF2C, KPNB1, KRT2, LEMD2, LMNB2, MBD3, MRPL15, MRPL16, MTA2, MTF2, RANBP1, RIF1, RPF2, RPL13, RPL19, RPL24, RPL26, RPL29, RPL3, RPL31, RPL36, RPL38, RPL39, RPL4, RPL5, RPL7A, RPL7L1, RPL8, RPS10, RPS11, RPS13, RPS14, RPS15A, RPS16, RPS19, RPS19BP1, RPS21, RPS26, RPS28, RPS29, RPS3A, RPS9, SERBP1, SCAMP3, SPN, SRP14, TCOF1, TOR1AIP1, TMPO, UBA2 | |

| 3 | 50 | ARID3A, ATL2, ATXN2L, BCLAF1, BYSL, CCAR1, CEBPZ, CHD4, CHTF8, CIRBP, CLTA, DDX17, DDX18, DDX21, DDX3X, DDX5, DDX51, EXOSC10, FTH1, HDLBP, HNRNPA3, HNRNPF, HNRNPH1, HNRNPK, HNRNPU, LSR, LTV1, MPP1, NONO, NOP14, NOP2. PDCD11, POLDIP3, RABL6, RBM28, RBM3, RBMX, RSL1D1, SAMD1, SCAF11, SDAD1, SF1, SFPQ, SLTM, SRSF5, SURF6, TRIM28, ZC3H14, WBP11, ZNF207 | |

| 4 | 58 | AGPS, ALYREF, ARL6IP6, CHERP, CHTOP, CLTB, CSTF2, CWC15, EIF4H, EFHD2, FIP1L1, FUBP1, FUBP3, HNRNPA1, HNRNPA2B1, HNRNPC, IGF2R, IK, LSM14B, LSM4, MARCKSL1, MFAP1, NELFA, NUDT21, NUP133, NUP50, NUP98, PHF23, PNN, POM121C, PQBP1, PSIP1, PTBP1, RALY, RBM14, RBM17, SAFB2, SARNP, SART1, SART3, SF3B5, SLIRP, SNRPE, SNRNP40, SNW1, SRRT, SRSF2, SRSF3, SRSF6, SRSF7, SRSF9, SSBP1, STX16, TIMM9, TMEM214, TPR, YBX1, ZMAT2, | |

| 5 | 45 | AKT1S1, ATP5I, ATP5J, ATP50, ATP6V1F, ATP6V1G2, AUP1, CHCHD1, CKB, CMC1, COA4, COX4I1, COX6B1, COX6C, ETFA, DDRGK1, ETFB, HBG2, HIGD1A, IMMT, MFF, MPC1, MRPL14, MRPS23, MRPL34, MRPS31, MRPS36, MT-ATP8, MTDH, NDUFAF2, NDUFB6, NDUFS4, NDUFV3, PPP1R10, PPP1R2, PRRC2C, PRKCSH, PYCR1, PYCR2, RREB1, SON, TFAM, TIMM8A, UQCRB, ZC3H4 | |

| Treatment 20 µM | 1 | 4 | ALB, GANAB, SF3A1, TFRC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).