1. Introduction

With its contribution to the gross domestic product in many countries of the world, the construction sector shows a high potential for economic growth [

1,

2]. In Ecuador, in 2022, this sector had a 6.4% share of the country's economy [

3]. However, due to the significant urban growth and the subsequent higher demand for construction materials and industrialization of production processes, several concerns are growing around the sustainability of the construction sector.

On the environmental side, the construction sector has long been identified as one of the sectors most contributing to negative environmental impacts worldwide. Nowadays, it is responsible for consuming around 40% of natural resources and 36% of energy globally. Associated to these are the generation of 40% waste and the release of 33% of greenhouse gas emissions [

4,

5]. Ecuador is no stranger to this reality. Indeed, the country has experienced rapid adoption of industrialization processes in the construction sector, which contributes to the consumption of approximately 48% of natural resources, 7% of energy, and 15% of fossil fuels within the country [

6]. The building materials play a crucial role, being responsible for 82% of carbon emissions from buildings; also, 38% of the total energy used by buildings during their whole lifetime comes from the embodied energy in construction materials, therefore associated with their own value chain [

7] and production process.

Currently, in Ecuador, as in other countries of Latin America, the predominant construction material is concrete, abundantly used in all structural construction elements, from foundations to roofs [

8], because it is a low-maintenance, versatile, and economical material. While the use of concrete and associated industrialized production processes have made it possible to cover the existing housing deficit in the country to some extent, concerns arise around the environmental sustainability of such material [

9]. On this line, environmental awareness, pushed by the UN Agenda for Sustainable Development [

10], demands more environmentally friendly materials. This has increased interest in vernacular materials and traditional construction techniques. Several studies have shown that using vernacular materials, which are locally available, with lower transport requirements and lower embodied energy due to the simpler production processes, can contribute to reducing the environmental impact [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. However, these studies are limited in their material coverage and geographical scope, mainly focusing on European and Asian countries [

16]. This is reflected in the databases for environmental sustainability assessment like ecoinvent [

17], and leads to a lack of quantification and understanding of the environmental impacts of the building sector in other contexts such as Ecuador. Approximations from countries with similar geographical conditions could be used. However, using the production data of a material in one country to assess the environmental impact of the production of the same material in another country can lead to an under- or overestimation of the impact, resulting in a variation of 19% in the final results for the Ecological Footprint of the production of construction materials when changing from one database to another [

18].

From a socio-economic perspective, the construction sector sees a high number of workers in informal working conditions who face problems related to occupational health and safety, fair wages, working hours, and social security. In Ecuador, the number stands at around 77% [

19]. These socio-economic aspects are often neglected in the current literature discussing the sustainability of the construction sector, which tends to focus solely on the environmental dimension. Only a few studies are available that evaluate the social impacts associated with the life-cycle of materials and their use in construction, although with limited materials (e.g., concrete, steel, and bamboo) [

20,

21] and indicators (e.g., job creation potential) coverage [

21]. In addition, local communities are concerned about the increasing adoption of industrialized techniques and materials imported from other countries. While these are used to meet housing demand quickly, they do not fully respond to the needs of local communities [

22], not only in form but also in their cultural context, as the architecture and the materials used expresses the culture that made it possible through form and function [

23].

Therefore, we aim to assess the impacts of the production of building materials through an interdisciplinary approach, thus understanding the complexity of the reality composed of multiple dimensions (environmental, social and cultural), their relationships, and possible trade-offs or synergies [

24]. Through this approach, we address sustainability as a complex system [

25] in the construction sector, where problems and solutions go beyond the scope of a single discipline [

26] since their effects are simultaneous [

27] in the dimensions that make up the system. This makes it a more crucial issue to be addressed.

The present study analyzes the impact of the production process of six local traditional and contemporary construction materials in Ecuador from an environmental, social, and cultural perspective, thus allowing for a more holistic view. The analyzed materials are bamboo, adobe brick, clay brick (both moulded and extruded), clay roof tile and concrete block.

Two key aspects are addressed in this study. First, the use of an interdisciplinary life-cycle based approach (environmental and social) combined with an ethnographic-based methodology to show the importance of a sustainability assessment with a holistic perspective to find a balance point between the various sustainability dimensions. Second, for the first time, data from local producers of materials used in traditional and modern constructions were collected to reflect the reality of Ecuador.

The article is structured as follows.

Section 2 details the methodologies used in the study for the selection of the local construction materials in Ecuador (2.1), the environmental and social assessment (2.2), and the identification of cultural characteristics and meanings (2.3).

Section 3 shows the results of the selection of the local construction materials, the results of both environmental and social life cycle assessments, and the results of the identification of cultural meanings for each production process.

Section 4 reports the discussion based on the integration of the results of

Section 3, and finally, Section 5 draws conclusions and provides an outlook for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

The sustainability assessment of the production of local construction materials in Ecuador involved three main steps and methods:

Selection of five local construction materials, beside concrete, through a multi-criteria method

Assessment of the environmental and social sustainability through the application of life cycle analysis methodologies

Identification of cultural meanings associated with the production of the selected materials through the ethnographic method

2.1. Selection of local construction materials

A preliminary list of local materials was elaborated according to the knowledge gathered by the authors through literature analysis of the materials produced in the whole country and how much they are used in the construction sector [

28]. The materials were grouped into traditional materials based on natural fibers, traditional materials based earth and contemporary materials beside concrete blocks.

A multi-criteria analysis was applied to rank alternatives according to the weights assigned to certain criteria [

29] to select at least five locally produced materials in Ecuador. The criteria, summarized in

Table 1, were defined based on the technical, environmental, social, and cultural dimensions. Additionally, sub-criteria were defined, based on the key concepts within each dimension and the real possibilities of gathering useful information in the field to develop the assessments. The weights assigned to the criteria and sub-criteria were developed based on contributions from the team and their expertise in the architectural, environmental, and sociological areas and validated by a group of external experts.

The highest-scoring material within the group of natural fibers, the two highest-scoring materials within the group of traditional earth-based materials, and the three highest-scoring materials within the group of contemporary materials were finally selected. With these considerations, the final list of selected materials is composed as follows. For traditional materials based on natural fibers bamboo (spanish name: caña Guadua) was selected. Three types of bamboo will be presented in the results, bamboo culm, bamboo pole and flattened bamboo, which are part of the same production process but depending on consumer needs can be sold at different stages, so they are presented separately. For traditional materials based on earth adobe and moulded clay brick, (Spanish name: Ladrillo Panelón) were selected.

For contemporary materials extruded clay brick (Spanish name: Ladrillo tochano), clay roof tile, and concrete block (cement-based material, which is why cement was not selected as another material for the study) were selected. Regarding clay roof tiles, an additional production step warranted the analysis of two distinct types: standard clay roof tiles and glazed clay roof tiles, the latter treated with lead oxide and silica for glazing.

Since the chosen materials are available in different provinces of the country, for the data collection of the production processes, the team selected the provinces where such materials are most produced. Two provinces with their respective capitals were identified:

For bamboo, the province of Manabi with its capital, Portoviejo, was selected [

30].

For adobe, clay bricks and tiles, the province of Azuay with its capital, Cuenca, was selected [

31,

32,

33].

For concrete blocks, its presence all over the country [

8], it was not necessary to choose a specific location. This widespread availability ensures that this material can be sourced from various locations as per the current project needs.

2.2. Environmental and social assessment through life-cycle based methodologies

The environmental and social impacts of the selected materials' production processes were assessed using life-cycle methodologies [

34,

35]. The data for each material's life cycle inventory (LCI), environmental and social, were collected from eleven production workshops through direct observation, interviews, and surveys compiled by the producers.

For the environmental life cycle assessment (E-LCA) the objective was to determine the environmental impacts associated with producing 1 kg of each of the selected local materials in Ecuador. Since the study focuses on the production processes of the materials, comparisons between materials will only be possible at the production level. At the level of use of the materials, i.e. in the construction of a house, the results do not allow a comparison between materials, since the function of 1 kg of, for example bamboo, is different from 1 kg of a brick when used for the construction of a house, but this evaluation is the first step to allow the evaluation of a house built with the analyzed materials. The system boundaries were established as cradle-to-gate, i.e., from the extraction of raw materials which enter into the factory to the production and storage of the final product (i.e. the material ready to be used in buildings).

To develop the environmental LCI, the quantities of energy, raw material and chemicals were calculated and recorded as input flows, and the quantities of the reference product, by-products, emissions, and solid residues as output flows. In addition , on-site measurements were taken in the workshops to obtain the required volume or mass data. The LCI of the production of each material was elaborated according to the guidelines established by ecoinvent [

36,

37,

38], the most used background life cycle database for life cycle related data, with the purpose that these datasets have a format that can be published and used at a global level. For the background data, ecoinvent v.3.9.1 was used.

Two methods available in the SimaPro software v. 9.4.0.2 were then used to calculate the environmental impacts. Specifically, the IPCC 2021 [

39], whose results are reported in kg CO2-eq/kg of material produced, and the Environmental Footprint (EF 3.0) [

40]. The EF method includes 16 impact categories and provides normalized and weighted results. Normalization and weighting steps were used to facilitate the summation of the various environmental impacts and obtain the individual contribution of each category to the overall impact, expressed in milipoints (mPt) per kg of material produced [

40,

41]. The IPCC 2021 method offers an updated approach to assess climate change compared to the one available in the EF v.3.0 (based on IPCC 2013) [

42], allowing to point out the differences between artisanal and mechanized or semi-mechanized production processes, while the EF v3.0 method addresses multiple impact categories based on different indicators and mathematical models. Also allowing us to make a comparison with the LCI results of producing same/similar materials in other regions of the world, by using the data sets already available in ecoinvent v.3.9.1.

For the social life cycle analysis (S-LCA) , it was defined as an objective and scope to determine the social performance of artisanal and semi-mechanised construction material production workshops. This analysis follows a ‘door-to-door’ approach, focusing on a single stakeholder: workers/producers.

The system and its boundaries were defined according to the characteristics of the production processes of the selected materials. Since most of them share a similar structure except for the bamboo process, the boundary of the system starts with the arrival of the raw material at the workshop and ends when the building material is finished and stored ready to be sold. In the case of bamboo, the transfer from the bamboo plantation to the preservation center, where the final processes are carried out and then the ready material is stored, was taken into account.

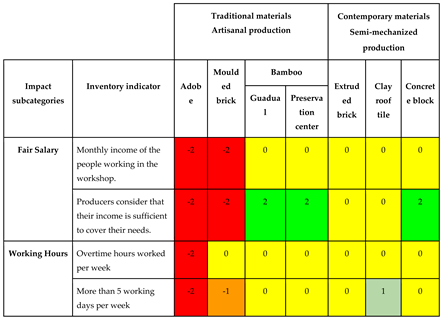

To create the social LCI, the primary data were collected through direct interviews with open questions and surveys applied to workers (the producers of the selected materials). Seven impact subcategories and 13 inventory indicators were assessed to determine the social performance of the workshops analyzed, which is an ”output compared to a known standard, often expressed as a score” [

35] (p. 25). The indicators were adapted from the Methodological Sheets for Subcategories in Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA) [

43] to fit the informal context in which several of the selected materials are produced (

Table 2).

The Type 1 (Reference Scale Approach) evaluation is based on the construction of reference scales. These have been developed for each of the indicators used in the research, as shown in

Table 3. The scales were based on criteria derived from specific regulations, best practices, and statistics, thus allowing to "value" the positive and negative social performance. The reference scales with linear scores were built based on the recommendations of the Guidelines for social life cycle assessment of products and organizations [

34], and an adaptation was also generated to better correspond to the local context and the production sector. The range was set from -2 to +2, where (-2) represents the worst performance, zero indicates neutral performance (benchmark set based on compliance with regulations that apply to the evaluated activity), and the top level (+2) corresponds to positive or ideal performance. It has to be noted that in specific indicators (overtime worked per week, more than 5 working days per week, child labor and sanitary facilities in the workshop) the reference scale ranges from -2 to 0 since the neutral point corresponds to the non-existence of a bad social condition.

For the performance assessment, which involves applying reference scales to the collected inventory data, the data were consolidated into a unified database using Excel (spreadsheet software). This database allowed for the automated evaluation using reference scales (ranging from −2 to +2). The final table, containing inventory and performance indicators, serves as the basis for creating heat maps, dashboards, or reports to present the assessment results.

2.3. Analysis of cultural aspect through ethnographic methodology

To identify the cultural meanings and key characteristics of the types of production processes of the selected local materials, an ethnographic approach was applied to the producers of construction materials. Through this approach, the meaning of material things and of the activities [

44] carried out by the producers during their everyday life was identified and analyzed.

The data used for the development of the ethnographic method were of a verbal and linguistic qualitative nature. Data that are condensed in the discourses of the producers. Through these discourses it is possible to access the meanings and specific cultural characteristics behind the production processes. This is because the discourses express the symbolic and material conditions that give meaning [

45] to the production activity and at the same time they make possible the creation of the discourse itself.

These qualitative data were collected through open-ended question interviews which allows better access to the concepts and notions that individuals use to make sense of their activities by constructing argumentative systems [

44] or conceptual/theoretical schemes using these concepts and notions. Also the interference of the researcher in the answers given by the interviewed actors is significantly reduced.

The construction of these systems followed the QUAGOL methodology for qualitative data analysis [

46]. This process involves moving from literal interview transcriptions to narrative reports and then to conceptual schemes, which are tested by rereading the interviews to ensure their explanatory adequacy. Once the theoretical schema is validated, the coding phase begins, using the list of concepts from the schema as starting codes. This step further validates the concepts by coding the interview transcriptions with the schema’s concepts. Finally, a conceptual framework is built, structured around the narrative of the producers’ discourse, connecting key concepts to organize and give meaning to their productive activity.

3. Results

3.1. Environmental impact assessment

The results of the application of two methods for the determination of the environmental impact of the production processes of the six selected materials are presented below.

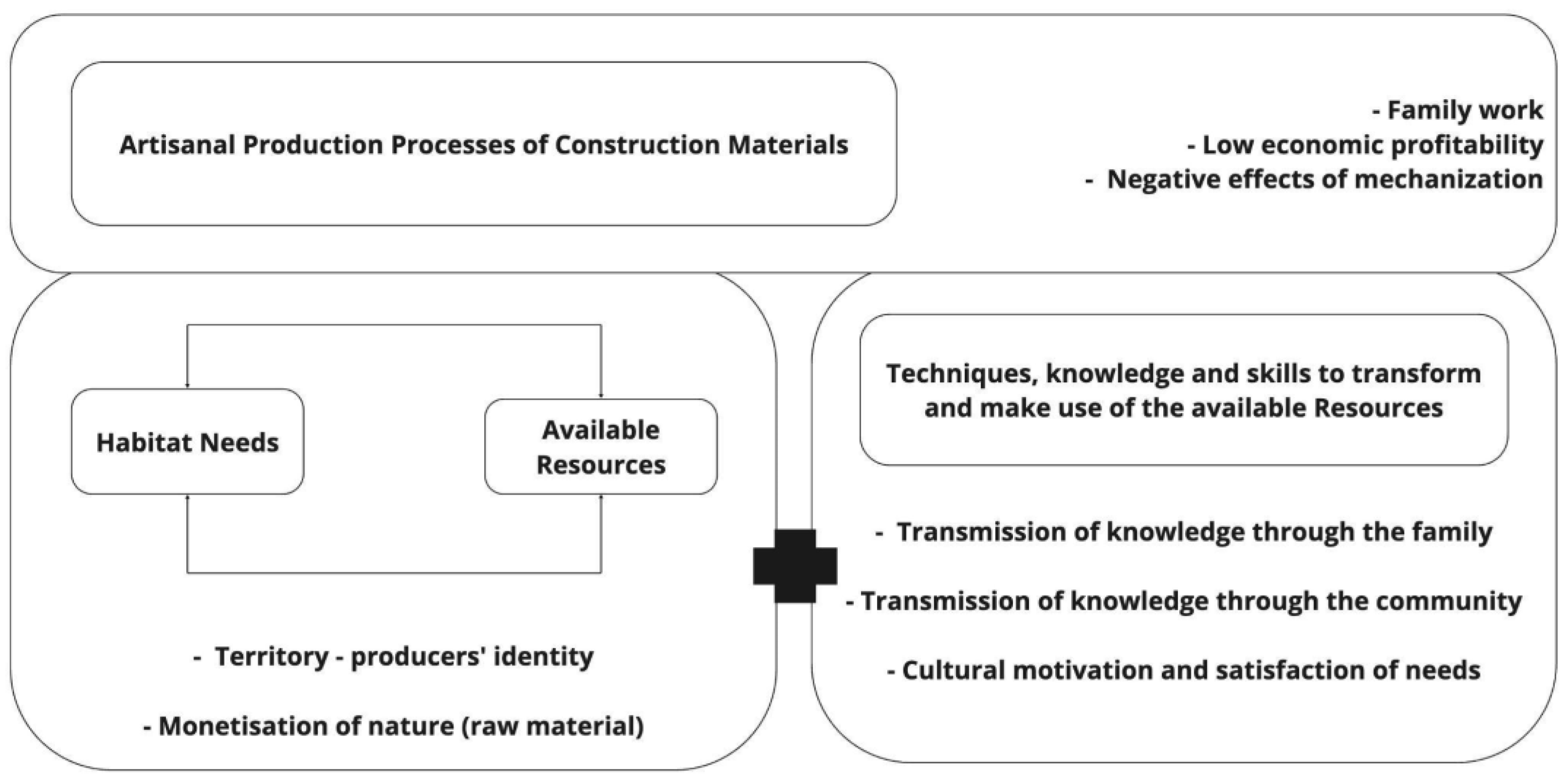

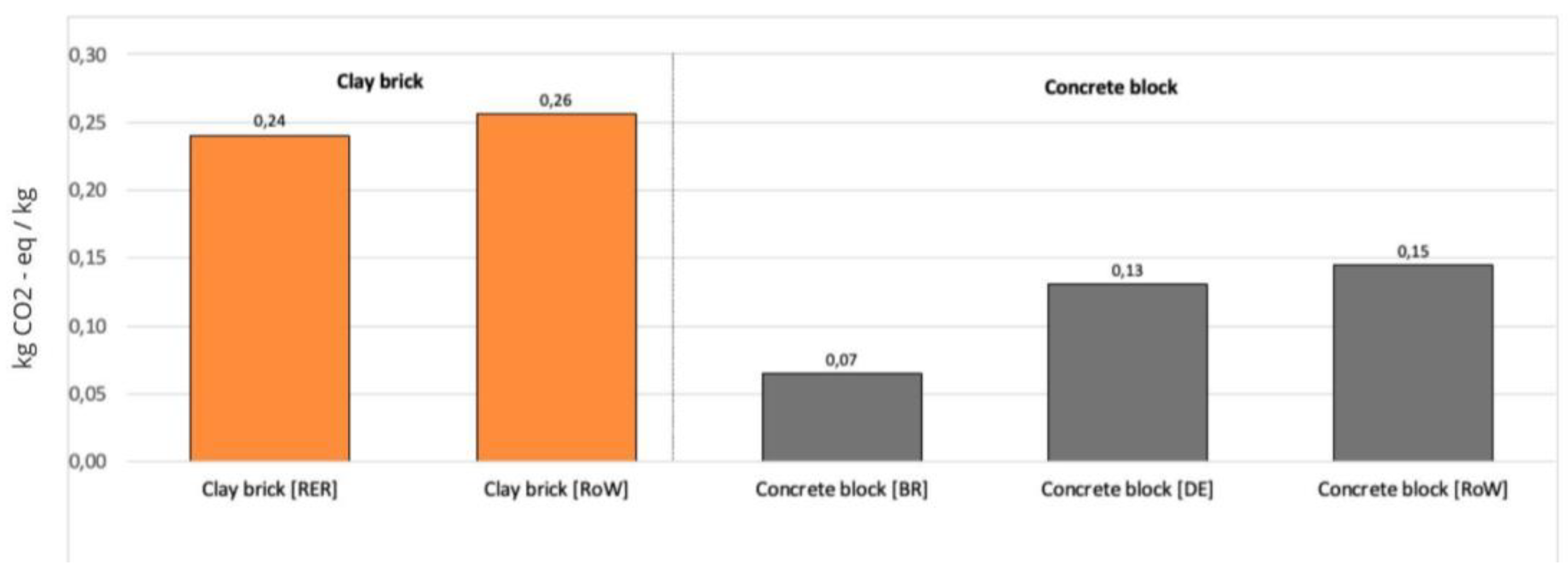

Figure 1 shows the potential climate change impacts associated with the production of both traditional and contemporary building materials, expressed in kg CO2-eq/kg of material produced, calculated using the IPCC 2021 method. The production of these materials in Ecuador generates lower amounts of CO2-eq compared to the data from other countries presented in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

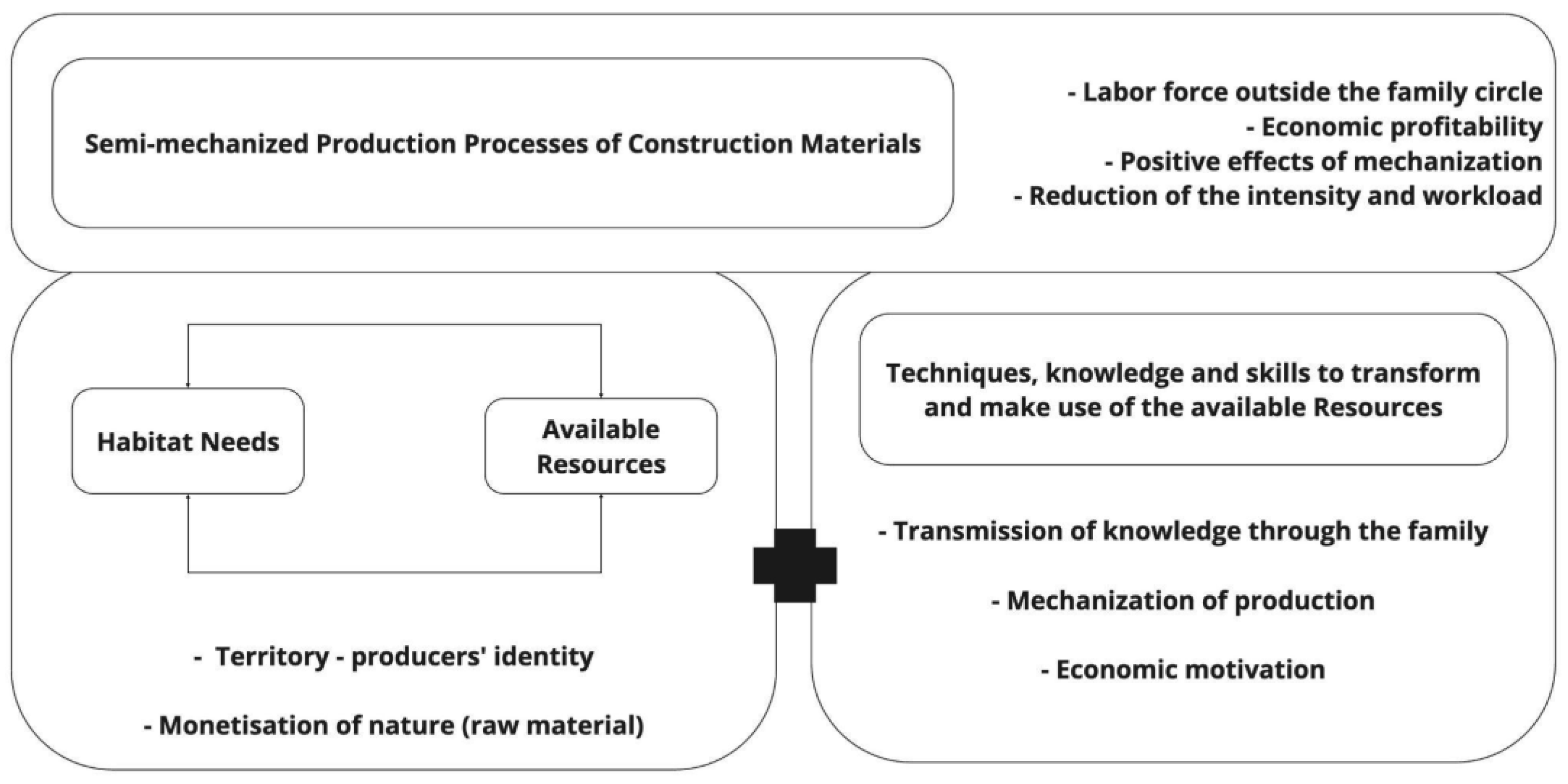

In the case of bamboo culm, cane silviculture in Ecuador does not generate CO2-eq emissions since most of the crops are natural bamboo plantations. This is due to the fact that the use of pesticides, herbicides and fertilizers is uncommon, in addition to the fact that crop maintenance is carried out using artisanal and often manual techniques, avoiding the consumption of energy and the emissions from machinery. These factors contrast with production in China, where it is estimated that 0.05 kg CO2-eq/kg of material produced is generated by the mechanization of the process and the use of fertilizers (

Figure 3). The process of preserving bamboo poles in Ecuador shows significantly lower CO2-eq emissions per kg of material produced compared to similar activities in other Latin American countries and World regions (

Figure 3). Specifically, these emissions are 84% lower compared to Colombia and 94% lower compared to China. Also the global warming potential associated with flattened bamboo production in Ecuador shows lower scores compared to Colombia and China; particularly it is 5.7 times lower than in Colombia and 13 times lower than in China. These results are attributed to the artisanal approach that prevails in the production of these materials in Ecuador, characterized by the minimal use of machinery, which contributes to a reduced carbon footprint. In addition, it is important to note that the current demand for these materials does not require considerable investment to implement technified processes.

The global warming potential scores of adobe and moulded clay brick production were compared with the ones of brick production outside Latin American regions, since there is no LCI data on the production of this material available in ecoinvent for Latin American regions. The production of adobe and panel brick represents 6% and 16%, respectively, of the emissions of kg CO2-eq/kg of material produced compared to the average European reference and the rest of the world (

Figure 3) . This is due to the fact that the production of these materials uses firewood as fuel instead of fossil fuels, as is the case of the average European reference and the rest of the world.

Concerning the production of contemporary materials (

Figure 1), the production of glazed tiles presents a higher amount of CO2-eq emissions compared to the other materials; this is due to the additional firing after glazing, which leads to a higher use of fuel (firewood), thus corresponding to 53.3% of kg CO2-eq emissions more than the production of unglazed tile. The production of extruded clay brick in Ecuador presents 80% lower CO2-eq emissions compared to the average European reference and the rest of the world (

Figure 2).

In the production of concrete blocks, Ecuador has a lower CO2-eq per kg of material produced compared to Brazil, Germany and the rest of the world, with a difference of 29%, 62% and 67%, respectively (

Figure 2). The environmental impact of the concrete block accounts for the embedded impact of the precursor processes, including the production of clinker and cement. Cement and transportation are the main flows contributing to climate change in Ecuador, with 39% and 44%, respectively. In Brazil, the largest contributing flow comes from cement, accounting for 75% (

Figure 2). Therefore, transportation in Ecuador generates a greater amount of greenhouse gases and, consequently, a greater contribution to climate change compared to Brazil.

- 2.

Environmental Footprint (EF), measured in mPt/kg of material produced.

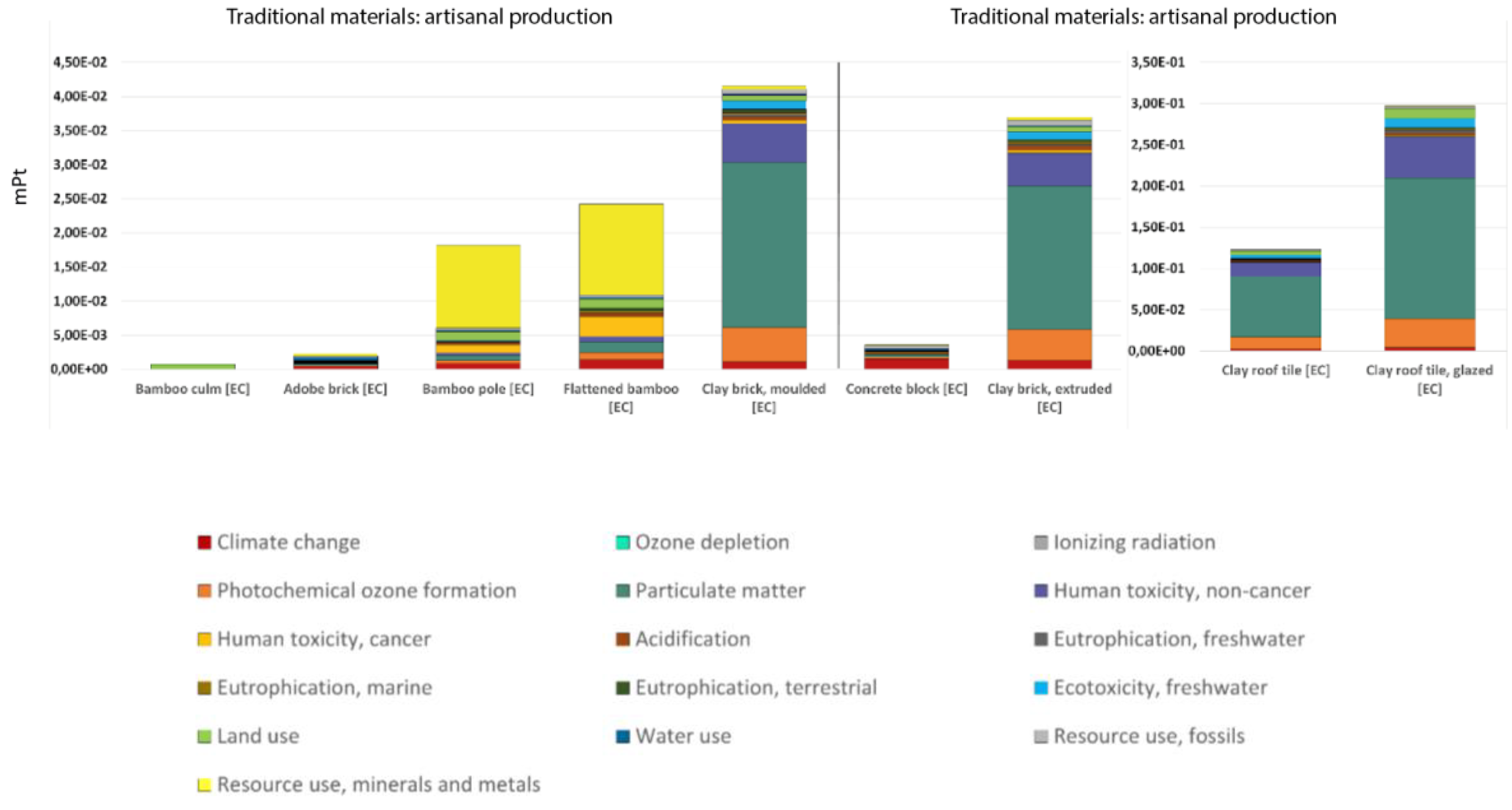

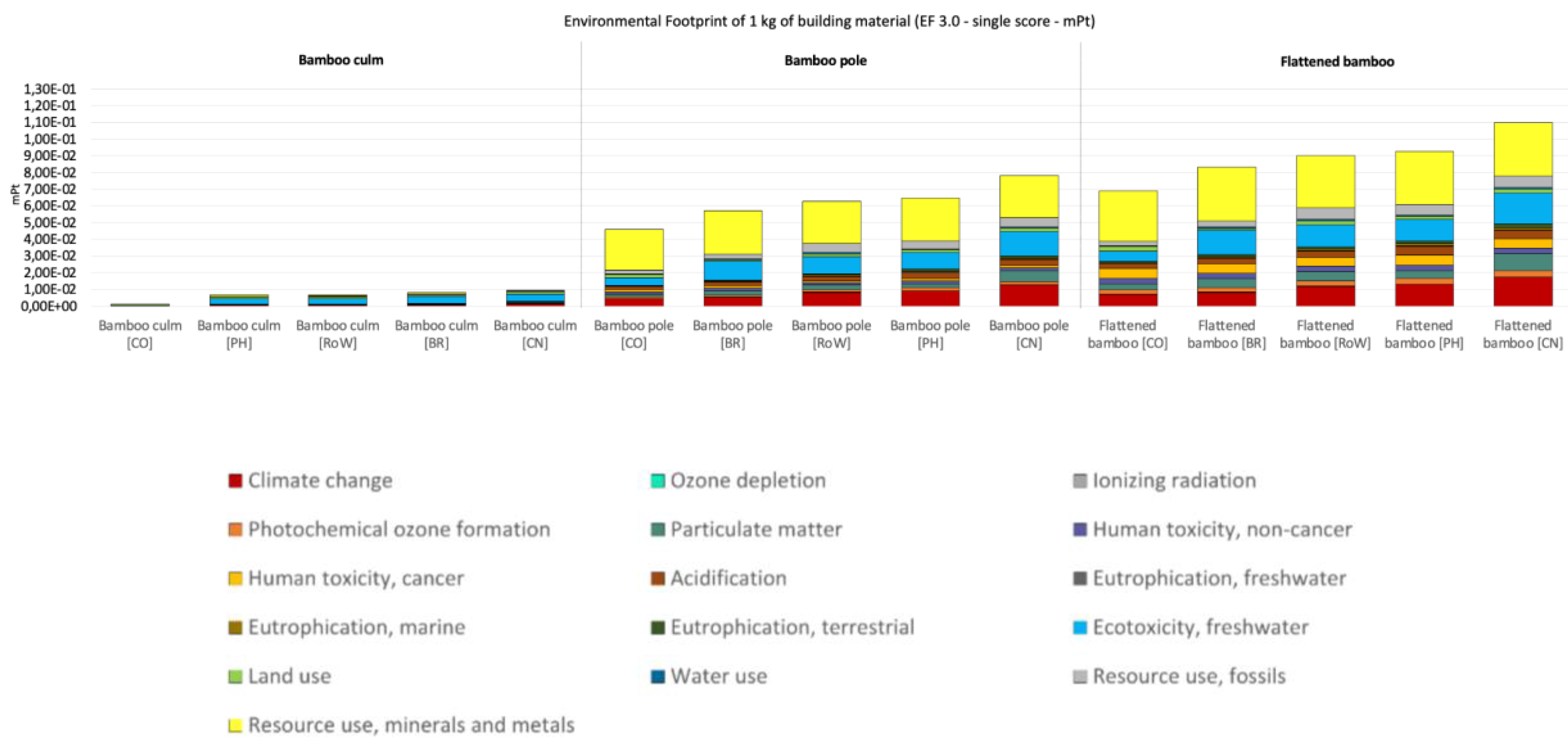

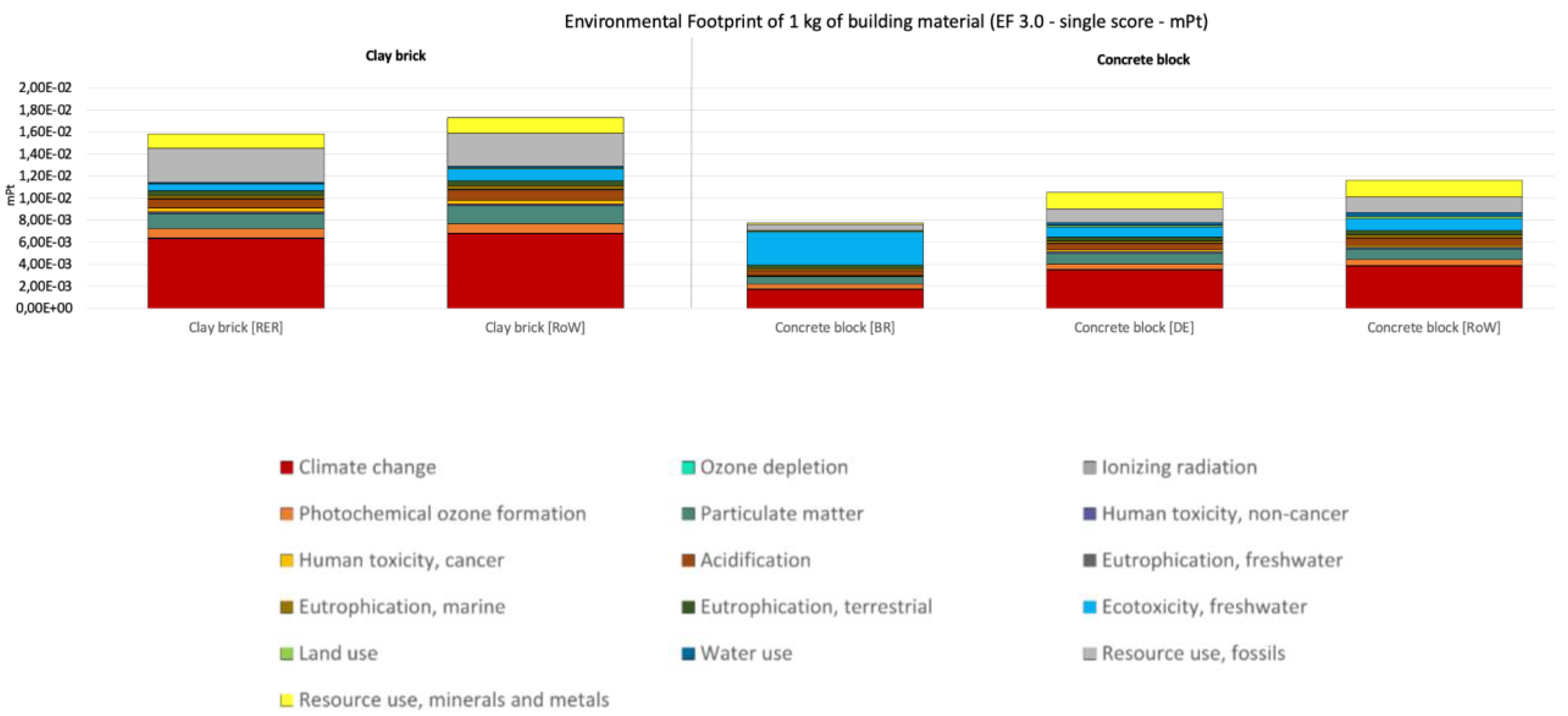

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show the weighted environmental impact of the production of traditional materials in Ecuador compared to other countries, calculated using the EF 3.0 environmental footprint method and expressed in mPt/kg of material produced. Each bar in the figure represents the weighted sum of the results for each impact category for each material.

When comparing the potential environmental impacts of the production of traditional materials in Ecuador, both adobe and bamboo have a considerably lower environmental footprint compared to moulded clay brick, which is the traditional material with the highest environmental impact. The environmental footprint of adobe is 94.5% lower than that of moulded clay brick, while that of bamboo poles is 87% lower. The categories with the largest proportion in the environmental footprint of adobe production are climate change with 18% and water use with 19%. Climate change reaches this percentage because the weight assigned to this indicator is the highest of all (21%), the rest of the indicators have a weight of less than 9%. In the case of water use, its high percentage is due to a combination of the inventory factor and the weight assigned to the indicator (it is third in the list with 8.5%).

Bamboo (culm) forestry in Ecuador (

Figure 4) represents the activity with the lowest environmental impact, compared to the impact of the same material in other countries (

Figure 5). The only category that generates environmental load in this activity is land use, with a value of 7.43E-04 mPt/kg of material produced. This category represents 7% of the environmental footprint of the production of bamboo poles, of which bamboo culm is the main input. This impact is associated with land occupation due to the annual harvesting of bamboo culm. Other categories that represent a greater proportion of the environmental footprint of both bamboo poles and flattened bamboo are the use of resources, minerals and metals and human toxicity (carcinogenic). These results are associated with the use of clay and the use of borax and boric acid in the process of preserving the canes, as well as the emission of ash from burning the canes to prepare the solutions. Compared to other countries such as Colombia, Brazil and China, the total environmental footprint of bamboo is significantly higher than that of Ecuador and its largest category is the use of mineral resources and metals (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). For bamboo poles, this category contributes to 53% of the total environmental footprint in Colombia, 45% in Brazil and 32% in China. For flattened bamboo, the figures stand at 43%, 38% and 28% respectively for Colombia, Brazil and China.

In the case of the production of moulded clay brick in in Ecuador (

Figure 4), particulate matter, human toxicity (non-carcinogenic) and photochemical ozone formation are the categories with higher scores, representing 57%, 13% and 12% of the total environmental footprint, respectively. These results are associated with particulate matter emissions produced during the firing process, where wood combustion also generates carbon monoxide and other gases such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and nitrogen and sulfur oxides. Compared to the average European and global benchmark (

Figure 6), the total environmental footprint of moulded clay brick is significantly higher, approximately doubling its value. This is due to the fact that the emissions of particulate matter represents a large proportion of the footprint, which are associated with the artisanal production process of this material, where there are no controls or mechanisms to reduce emissions and combustion is incomplete.

Regarding the environmental footprint of contemporary materials, according to

Figure 4, glazed tile has the largest environmental footprint with 2.97E-01 mPt/kg of material produced, followed by tile with 1.23E-01 mPt/kg of material produced and extruded clay brick with 4.78E-02 mPt/kg of material produced due to the consumption of diesel.

In the production of glazed tile, particulate matter has a significantly large environmental load compared to other construction materials; this is associated with the varnishing process, due to the use of lead oxide and the burning process, reaching 1.71E-01 mPt/kg of material produced, which in comparison with regular tile (without varnishing) is 7.31E-02 mPt/kg of material produced.

In concrete block production in Ecuador (

Figure 4) , the categories with the largest proportion of the environmental footprint are climate change, use of mineral resources and metals, and particulate matter, representing 42%, 14% and 10% of the total footprint, respectively. These results are attributed to embedded pollution from the block's precursor processes, i.e., clinker and cement production. During these processes, heavy metals, sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, VOCs and particulate matter are emitted, contributing to the carbon footprint and the presence of particulate matter in the air. In addition, the raw materials used, such as limestone, clay, gypsum, sand and gravel, are directly related to the mineral resources and metals use category. Compared to other countries (

Figure 6), Ecuador's environmental footprint is smaller compared to Brazil, Germany and the rest of the world, corresponding to 53%, 65% and 69%, respectively. In particular, climate change in Ecuador has an environmental burden approximately twice as high as in Brazil, while freshwater ecotoxicity shows a much higher impact compared to Ecuador, where it is 98% lower.

In the production of extruded clay brick, the categories with the largest proportion of the environmental footprint are particulate matter and photochemical ozone formation, due to the emission of sulfur and nitrogen oxides during the combustion of firewood in the brick firing process. These emissions enhance the formation of tropospheric ozone (smog) and increase the ash load (particulate matter) in the environment. As for the comparison of the environmental footprint between the two types of brick production in Ecuador, the brick where only diesel consumption is involved is 52% higher than the hybrid process (diesel and electricity consumption); it also has a higher load in all the impact categories evaluated. Compared to the average European reference (RER) and the rest of the world (RoW) (

Figure 6), the extruded clay brick from Ecuador shows a significant difference, being 53% higher in terms of total environmental footprint. In particular, the emission of particulate matter in Ecuador is approximately 14 times higher than these international references, while the carbon footprint is 5 times lower.

3.2. Social impact assessment of the production of construction materials

This section presents the results of the social impact assessment related to the production of local building materials, which were divided into two categories: traditional materials produced through artisanal methods (adobe, moulded clay brick and bamboo) and contemporary materials produced using semi-mechanized processes (extruded brick, tile, and concrete block).

Some common characteristics were identified in the analyzed workshops. In the adobe and moulded clay brick workshops, it was found that it is common for a single person to carry out almost the entire production process with the help of members of the family circle in specific processes of material transfer. The same person also owns the workshop and the tools necessary to produce these materials. In the case of bamboo, it has been found that much of the guaduales (bamboo plantations) from which the cane is extracted is of natural origin and has been inherited by the current owners. This means that the plantation's growing phase has no planned process or investment. It was also found that an average of three people are needed to extract the bamboo, which can vary depending on the size of the plantation. In the workshops of the contemporary semi-mechanized production materials, a significant shift in labor dynamics was observed. Indeed, the support of the family circle is drastically reduced, and the number of hired people increases. On average, five people work in the semi-mechanized workshops, which are concentrated mainly on transferring materials within the workshop and not so much on the manual transformation of the raw material.

Unlike the environmental life cycle impact assessment, for which results were presented by material, the social life cycle impact assessment presents its results in tables of social performance by material production workshop (

Table 4).

3.2.1. Social performance of traditional materials produced through artisanal methods

In the case of adobe production workshops, we can observe that the vast majority of indicators have the worst negative performance (-2), specifically in the subcategories of fair salary, working hours, health and safety, and social security. This is due to the fact that the monthly income of adobe producers is around US$90 per month. As for working hours, the workers and producers spend on average 10 working hours per day in the workshop and generally have an 7-day work week. In the indicator "Negative impacts on health and safety due to harmful substances/working environment" of the health and safety impact subcategories, a positive performance is recorded; this is due to the fact that no chemical or toxic substances of any kind are used for the production of adobe.

The inventory indicator ´Satisfaction with the productive activity´ from the subcategory ´Job Satisfaction´ expresses one interesting finding, which surprisingly shows the highest positive level (2). At first, this may seem contradictory, but upon delving into the socio-cultural meanings, a profound cultural motivation is discovered that keeps producers engaged in this type of production despite the negative performance in other impact subcategories. For these producers, adobe production is not just seen as the creation of construction material but also as a means of preserving and passing knowledge from their ancestors and community, a topic explored in detail in Section 3.4.

In the case of moulded clay brick production workshops, the worst negative performance (-2) is maintained in the fair salary indicators, with an average monthly wage of US$ 220 across the workshops analyzed. Regarding working hours, performance improves slightly, ranging from -1 to 0, due to the reduced human labor required for moulded brick production, unlike adobe, this material has a burning phase. This reduces the drying time and, therefore, the time required by the producer for this phase. At the same time, the burning phase generates emissions that can be harmful to health, affecting the health and safety impact subcategory, especially in the indicator “Negative impacts on health and safety due to harmful substances or the work environment”, which no longer has the same positive performance as in the case of adobe. The rest of the indicators remain the same as the performance of adobe since the production process of moulded brick does not vary significantly, except for the inclusion of the burning phase mentioned above. Therefore, the production of moulded bricks in the studied area has a similar negative impact on the quality of life of the workshop producers. Regarding the subcategory of job satisfaction we can find the same feature mentioned in adobe. The highest positive level (2) of performance despite the negative performance in other impact subcategories.

To understand the results presented in the performance table corresponding to bamboo, it is essential to mention a significant difference between the processes required to produce a bamboo pole, an adobe, or a moulded brick (Appendix 1 : Production Processes of Selected Materials). This difference lies primarily in the amount of human labor required to produce each material. In the case of bamboo, we are mainly talking about the process of extraction and preservation of raw material, in which no significant transformation of the raw material is performed. In the case of adobe and moulded brick, the opposite is true since the raw material undergoes a strong transformation process in order to be considered a finished building material.

This difference is clearly expressed in the column corresponding to the guadual (bamboo plantation), where the extraction process is carried out. The amount of human labor required in this process is lower than the amount needed for the production of adobe or moulded brick. In the case of the guadual analyzed, it is even more reduced since it is not a planned plantation, but left to grow naturally. Therefore, the performance in the subcategory of working hours is neutral. In the guadual analyzed, a maximum of eight hours per day and three days a week are necessary to complete the extraction process of 24 bamboo poles (what the owners of the guadual call a “balsa”); this can vary according to demand.

In the case of the fair salary subcategory, the performance is neutral, equal to the minimum wage established by law in Ecuador ($425) for 2022. In the Canton of Portoviejo, Manabí Province, the International Bamboo and Rattan Organization (INBAR) has played a significant role. They have provided training and technical advice to owners of natural bamboo plantations and conservation centers, leading to an improvement in the quality of bamboo canes and an increase in their selling price. This has resulted in a higher income for the owners and workers of the bamboo plantations and conservation centers.In addition, INBAR has also trained construction workers to create technical capacity in the area to use bamboo as a construction material for housing. This creates a greater demand, which also favors the performance closer to neutral in the fair salary subcategory.

3.2.2. Social performance of contemporary materials produced through semi-mechanized processes.

As illustrated in

Table 4, the performance across the three workshops dedicated to contemporary material production is notably similar. This uniformity is largely attributable to the integration of machinery in the production process, which reduces the reliance on manual labor while simultaneously enhancing production capacity. An additional advantage of these materials, not immediately evident from the data presented in the table, lies in their high regional demand. This factor contributes to increased profitability, which, in turn, supports improved outcomes regarding fair wages. Moreover, this heightened demand can lead to an extension of the workweek, surpassing the standard five working days mandated by law when production capacity is exceeded. This general analysis underscores the significant impact of mechanization on workshop performance.

In the case of

extruded clay brick production workshops,

Table 4 shows values that express a neutral performance in the subcategories of fair salary, working hours, and freedom of association. The performance in fair salary and working hours are an effect of the mechanization of the production processes; particularly the mechanization of the mixing and molding stage. As mentioned above, mechanization reduces the workload, increases production rates, and allows for greater economic profitability, which, in combination with the high demand for this material, allows greater profitability of the workshop to be generated. Which is expressed in an increase in their social performance.

For the clay roof tile production workshops in general, the values in the social performance table express a neutral performance in the sub-categories of fair wages, working hours, freedom of association, and child labour. In the specific case of this material, the molding stage of the production process is also semi-mechanized.

A similar scenario for the remaining contemporary semi-mechanized production material can be identified. When analyzing the concrete block results, the values express mostly neutral performance in the subcategories of fair wages, working hours, freedom of association, and child labor. In the specific case of the production of this material, the mixing and molding stages have been mechanized.

3.3. Cultural meanings in the production of construction materials: a first step towards the cultural dimension of sustainability

In this section, the results obtained through the application of the ethnographic method are presented, revealing key cultural meanings of the production of building materials linked to the circulation of techniques and knowledge essential for artisanal production that also made it possible to start the semi-mechanized production of some of the traditional materials. These techniques and knowledge passed down through generations within communities and families, thus being an essential part of their identity. It is important to mention that the results presented in this section do not follow the same logic of impacts as in the case of the E-LCA and the S-LCA. The meanings identified through the ethnographic method are rather elements that could be impacted by directly affecting the identity that producers have created around the activity of construction materials production.

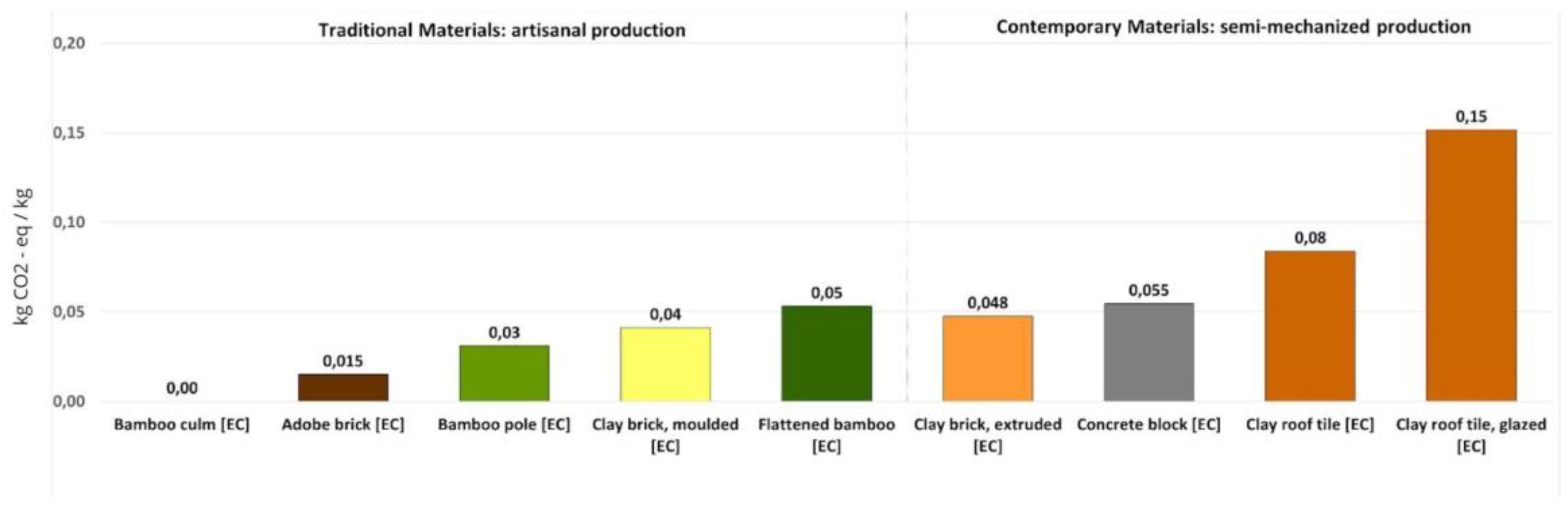

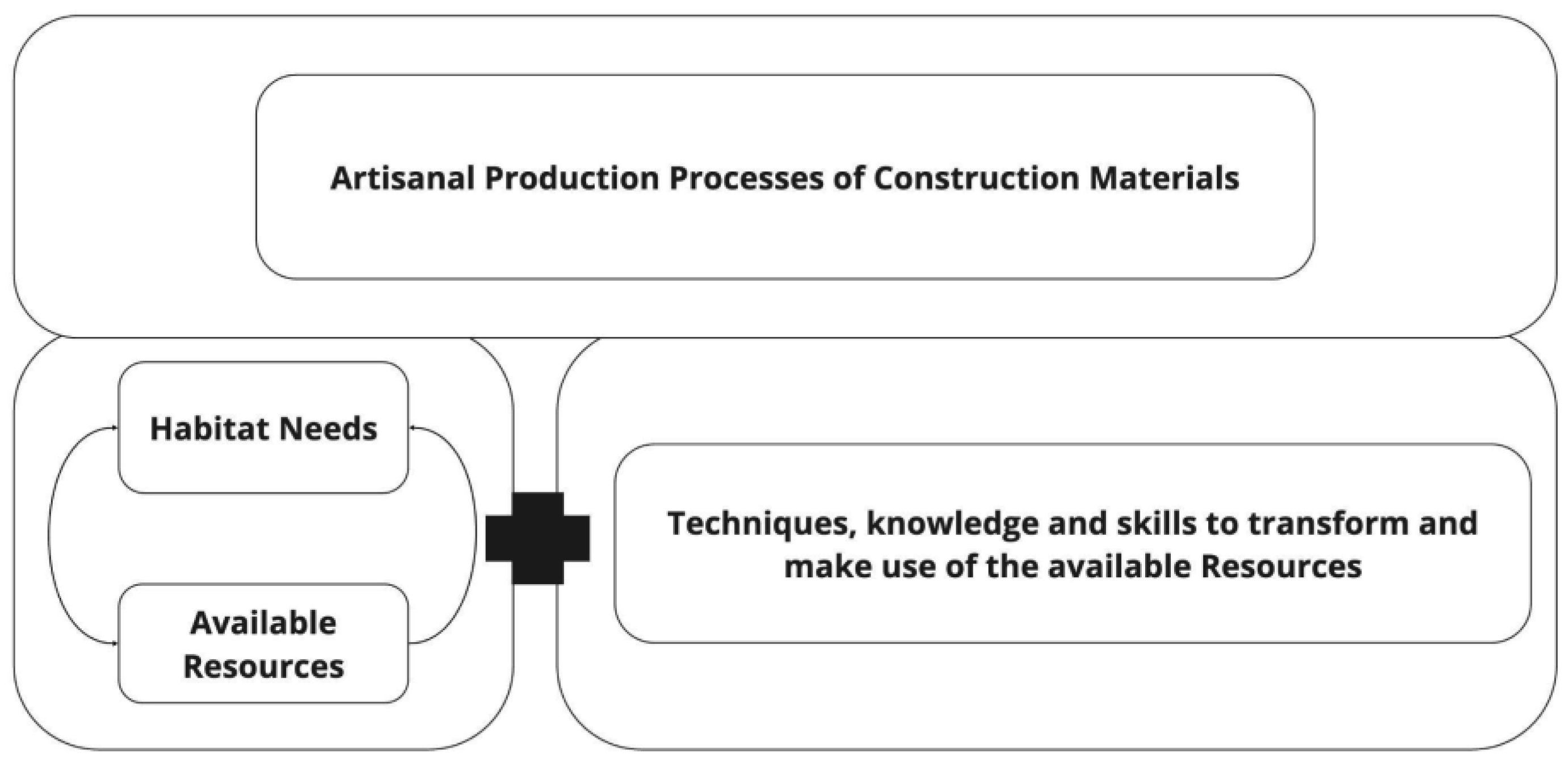

Figure 7 presents a theoretical schema of the material production process, constructed from the common elements in the producers' discourses. This scheme allows us to organize the concepts and meanings that producers use to make sense of artisanal and semi-mechanised production.

This diagram shows the relationships between the three main components that make up a building materials production process, whether it is artisanal or semi-mechanised. These three components are:

Habitat needs: The inhabitants of a territory have a need to create habitable spaces.

Resources available: The natural resources available in the area.

Techniques, knowledge, and skills: They allow the transformation and use of the available resources to create habitable spaces.

The relationship between these three components is developed as follows. The need to create habitable spaces meets the available natural resources and generates techniques, knowledge, and skills to transform and use these resources. This allows the generation of production processes of building materials to satisfy the initial need to create habitable spaces. In this way, the resources available strongly influence the type of techniques, knowledge, and skills that are developed and, therefore, the type of building materials that can be generated.

These three components combine tangible and intangible elements that are key to an in-depth understanding of building material production processes in general. The content of each component will vary as producers use different concepts to give cultural meanings to their activity according to the type of production, artisanal or semi-mechanized production. The section below presents the meanings identified within each component for each type of production following the logic of

Figure 7.

3.3.1. Artisanal production: of traditional materials (adobe, moulded clay brick and bamboo)

The aforementioned scheme is presented below with the information of the artisanal production of traditional construction materials, along with a description of the meanings that comprise it.

Figure 8.

Unified scheme of the concepts that give meaning to the artisanal production process.

Figure 8.

Unified scheme of the concepts that give meaning to the artisanal production process.

We will start from the bottom of the scheme, since the two bottom components are the basis for the consolidation of a material production process.

In analyzing the relationship between habitat needs and available resources, two key concepts emerged from the discourses of artisanal producers: territory-producers' identity and the monetization of nature (raw materials). Hector, a semi-mechanized tile producer, highlighted that Racar, a sector of the Sinincay parish in the city of Cuenca, has been a site for producing construction materials for over 100 years. Additionally, his possession of an old oven, which was originally owned by his wife's great-grandparents - who were also engaged in this productive activity - further supports his perception of Racar as an industrial zone for the production of construction materials. Luis, an artisan brick producer, noted that all producers use the same materials and live near their workshops, showing a strong connection to the territory, where generations of their families have also been engaged in construction material production.

The territory-producers' identity: implies that producers have a bond with the area in which they work since it is a space that has taken shape in function of the activity they carry out. Likewise, the materials they produce take shape based on the resources available in that territory.

The monetization of nature (raw materials) refers to how producers access raw materials and how this has changed over time. Currently, producers acquire materials through traders at prices set by intermediaries, leading to a disconnection from the extraction process. Previous generations, including parents and grandparents, had direct access to local raw materials without monetary exchange, which facilitated the growth of artisanal production, as access to these materials did not involve costs for the producers. Now, raw materials often come from external sources, raising production costs and threatening the survival of artisanal practices like adobe and brick production.

The need to create habitable spaces is closely tied to available resources, fostering the development of techniques, knowledge, and skills to transform and use these resources. These techniques are formalized and passed down through generations of producers. The knowledge possessed by producers regarding the utilization of these resources is present in their discourses, allowing for the identification of the concepts presented below.

Transmission of knowledge through the family: Techniques and skills for producing building materials have been transmitted/taught between family members, from one generation to the next, through direct practice in the workshops.

Transmission of knowledge through the community: Knowledge is not only limited to family circles; it also circulates in the community where these production processes take place. In the case of this study, the knowledge for the production of adobe and moulded brick is common knowledge in Racar and San Jose de Balzay, both sectors of the Sinincay parish in the city of Cuenca, and as we will see in the part on semi-mechanised production, it has served as a basis for the development of semi - mechanized production

Cultural motivation and the satisfaction of needs: Despite limited income from artisanal production, producers continue this work because it allows them to apply knowledge passed down through generations. Their identity as artisanal producers, strongly tied to the territory, is reinforced through this production process, serving as a key motivation. Their initial motivation does not stem from a cost-benefit or investment logic but from the need to create habitable spaces for the community. Once this need is met, the techniques for transforming the available resources are used to generate economic income for the producers. This is connected with the last component, the production process of artisanal materials as itself.

The final component focuses on the artisanal production process of the three traditional materials analyzed. At this level, the production of artisanal building materials is consolidated and no longer solely depends on the need to create habitable spaces for the producers themselves. It is also driven by the need to generate economic income from the knowledge they have developed about the resources available in their territory. The key concepts identified in the producers' discourses that characterize artisanal production are outlined below.

Family work: Artisanal production is largely based on family work. Most of the people involved in the production process are relatives of the workshop owner. This is directly related to the transmission of knowledge through familial and the community.

Low economic profitability: The social performance tables for adobe and molded clay brick show that producers do not generate enough income to meet all their needs. Interviews revealed that low profitability is mainly due to a lack of demand and competition from contemporary materials. As a result, some producers engage in other activities, such as subsistence farming, to meet their needs. This also limits their ability to hire workers, increasing dependence on family labor and affecting the continuity of this type of production.

Effects of mechanization: This concept is present in the two types of production, which generate different impacts. In the case of artisanal production, the effect is negative since it generates unequal competition in terms of production rates, workload, and prices. An example of this negative effect is the mechanization process of artisanal brick and tile production (moulded clay brick and semi - mechanized tile), which has generated a displacement of artisanal production forms.

In the particular case of adobe production, there is only non-technified artisanal production. Therefore, the material does not compete with other forms of production. In this way, it still has a significant cultural value as it is a totally handmade work.

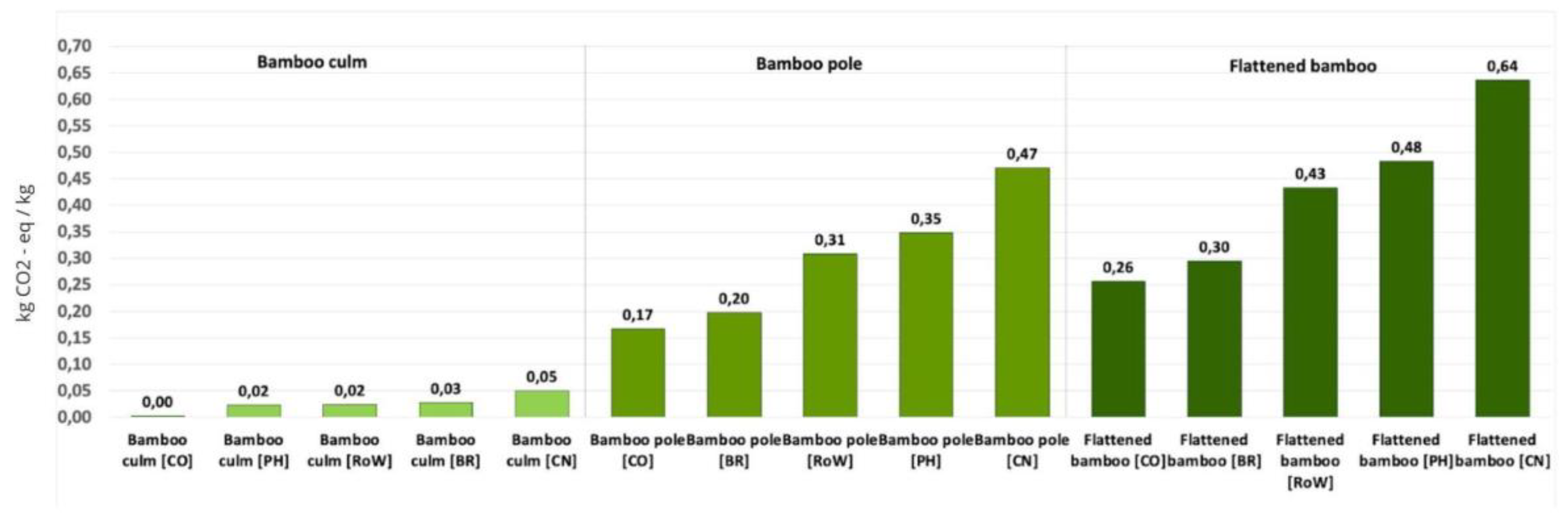

3.3.2. Contemporary materials: semi-mechanized production (extruded clay brick, clay roof tile and concrete block)

Following the same logic of analysis, the mains scheme is presented below with the information of the production of the semi-mechanized production of contemporary materials, along with a description of the meanings that comprise it.

Figure 9.

Unified scheme of the concepts that give meaning to the semi-mechanized production process.

Figure 9.

Unified scheme of the concepts that give meaning to the semi-mechanized production process.

We will start from the bottom of the scheme, since the two bottom components are the basis for the consolidation of a material production process.

In semi-mechanized production of contemporary materials, the relationship between habitat needs and available resources incorporates the same key concepts as in artisanal production, but with distinct definitions, which are outlined below.

Territory and producers' identity: In this research, we identified this concept among producers who have semi-mechanized brick and tile production. Unlike artisanal production, their identity is no longer directly tied to the natural resources of the territory but is instead mediated by artisanal knowledge passed down from the previous generation. This knowledge, inherited from their parents, is highly valued by the owners of semi-mechanized production workshops.

In the semi-mechanized tile production workshops, we have identified that the producers not only use the knowledge of artisan production to achieve the correct mixture of the different types of soil. They also maintain the traditional design of the tile. Based on the knowledge of artisan production, the producers of this material have incorporated machines in their production processes, generating a continuity in relation to the application of artisan knowledge for production.

This is the last connection between the two types of production and the only mechanism that generates identity within the territory for producers of contemporary materials. If we compare the production of roof tiles with the production process of concrete blocks, we see that the semi-mechanized production process of concrete blocks demands a type of machinery, materials and knowledge that increasingly distances the producer from his immediate territory, from the techniques and knowledge that circulate within it. Thus weakening the generation of an identity that is only possible thanks to the circulation of knowledge that arises from a relationship between artisanal producers and available resources.

Monetization of nature (raw materials): In the case of this type of production, the relationship with nature (raw materials) is mediated entirely by monetary transactions. This directly distances the producers from the available natural resources, making it difficult once again to generate an identity under the same logic that artisanal production does allow.

For the bottom right component, the concepts associated with this type of production are directly related to the integration of machinery into the material production process and are outlined below.

Transmission of knowledge through the family: In analyzing the interviews of both artisanal producers and those with semi-mechanized production, we identified a common element: the circulation of knowledge related to artisanal production in San José de Balzay, part of the Sinincay parish in Cuenca. This knowledge transmission primarily occurs within families. All interviewed producers operating semi-mechanized workshops in San José de Balzay come from a lineage that utilized artisanal techniques for producing construction materials.

This connection is evident in the progression from adobe to molded clay brick and finally to extruded clay brick, highlighting that the foundational knowledge of adobe production is crucial for developing these materials. The concept of familial transmission of artisanal knowledge indicates that semi-mechanized production does not entirely break from its artisanal roots. There is, for the moment, a very weak connection between the two types of production and, more importantly, a generational connection between the two types of producers. The weakness of this connection lies precisely in its generational aspect since when the generation of artisanal producers disappears; this knowledge will cease to circulate. This would only give way to the circulation of the knowledge necessary for semi-mechanized production.

Once the concepts that semi-mechanized production shares with artisanal production have been described, the concepts specific to this type of production are presented below. These are key to understanding how producers give meaning to their productive activity and how they justify the incorporation of machines in the production process

Economic motivation: In mechanized production, motivation is primarily driven by economic profitability, contrasting with the cultural motivations found in artisanal production. The efficiency gained from incorporating machines justifies the producers' continued investment in this production method. Several interviewees noted that the introduction of machinery in brick and tile production has enabled them to sustain their activities; without it, they would have had to seek alternative sources of income.

Mechanization of production: This second concept, specific to semi-mechanized production, has a strong link with economic motivation since it allows solving some of the problems that arise in artisanal production, which does not allow it to be sufficiently profitable. On this basis, the mechanization of production not only has a direct effect on the production process and its rhythms. It also changes producers' meanings and motivations to carry out and maintain this productive activity.

For the top final component, the following concepts will help us to understand and characterize the semi-mechanized production process as a whole.

Effects of mechanization: The introduction of machinery for producing clay bricks, clay roof tiles, and concrete blocks has three primary effects. First, it displaces traditional fully manual techniques. Second, it reduces the amount of human labor needed for production. Third, it accelerates production speed, increasing the workshop's overall capacity. These effects are essential for understanding the various concepts identified in the discourses of producers who operate semi-mechanized workshops, as they arise directly from the use of machines.

Intensity and workload: In this type of production, the amount of human labor required to produce the materials analyzed is reduced thanks to the mechanization of the molding stage. This makes it possible to produce more elements in less time and with less labor.

Economic profitability: The reduction in labor and the increase in production capacity due to machinery significantly enhance the economic profitability of workshops compared to artisanal production. For instance, an adobe producer earns around $90 per month, primarily limited by the three-month production time and low demand. In contrast, concrete block producers earn approximately $425 monthly, benefiting from a much faster production rate, as the mixing and molding processes are mechanized, allowing for completion in just four days. Additionally, this increased productivity aligns with the demand for contemporary building materials, enabling workshop owners to recover their investments more quickly. Thus, the advantages of mechanized production lie not only in reduced production times but also in the rapid market circulation driven by high demand.

Labor force outside the family circle: Increasing economic profitability allows hiring labor outside the family circle. In contrast to artisanal production, which relies heavily on family cooperation, semi-mechanized production drastically reduces the presence of the family. As a result, the workshop as a space for transmitting knowledge of artisanal production through the family is severely weakened.

4. Discussion

The objective of this study is to provide insight into the sustainability of traditional and contemporary construction material production in Ecuador. To this end, a comprehensive environmental, social, and cultural analysis of the production of these materials has been conducted through an interdisciplinary lens. This approach not only presents the outcomes of each methodology (3. Results), in this section we also discuss the relevance of the result and identify potential interactions between the dimensions of sustainability under analysis (environmental, social and cultural).

The results obtained from the environmental analysis (

Section 3.1) clearly show that when we compare the semi-mechanized production of contemporary materials with the artisanal production of traditional materials, also considered vernacular materials. These materials generate a lower environmental impact. This is in line with what is stated in other studies that vernacular materials, which are locally available, with lower transport requirements and lower embodied energy due to the simpler production processes, can contribute to reducing the environmental impact [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Also, the generation of environmental inventories for the six local materials analyzed allows avoiding the under- or overestimation of impacts when using the production data of a material in one country to assess the environmental impacts of the production of the same material occurring in another country [

18]. This increases the datasets available for Ecuador and Latin America and the possibilities to generate environmental impact analyses according to the reality of the region.

On the other hand, the results of the social analysis (

Section 3.2) add to several investigations that have applied the S-LCA methodology to the production of building materials [

20,

21,

47] (although with limited material. e.g., concrete, steel, and bamboo), presenting the social performance of four materials that had not been evaluated before in the region (adobe, molded clay brick, extruded clay brick and tiles). The study demonstrates that S-LCA enables a comprehensive integration of social dimensions associated with the well-being of diverse stakeholders into a more holistic sustainability analysis. This approach extends beyond the conventional focus on environmental, economic, and aesthetic factors, which have traditionally shaped the selection of building materials [

48].

Finally, the cultural results (

Section 3.3) allowed us to identify meanings that follow the approach that architecture and the elements that make it technically possible, including the production processes of building materials, cannot be reduced to a pure functional form [

23]. Behind each material production process and the houses built with these materials there is a system of cultural meanings that give sense to the form (materials and houses), i.e. the material production processes and architecture as such are at a middle ground between form and culture [

23].

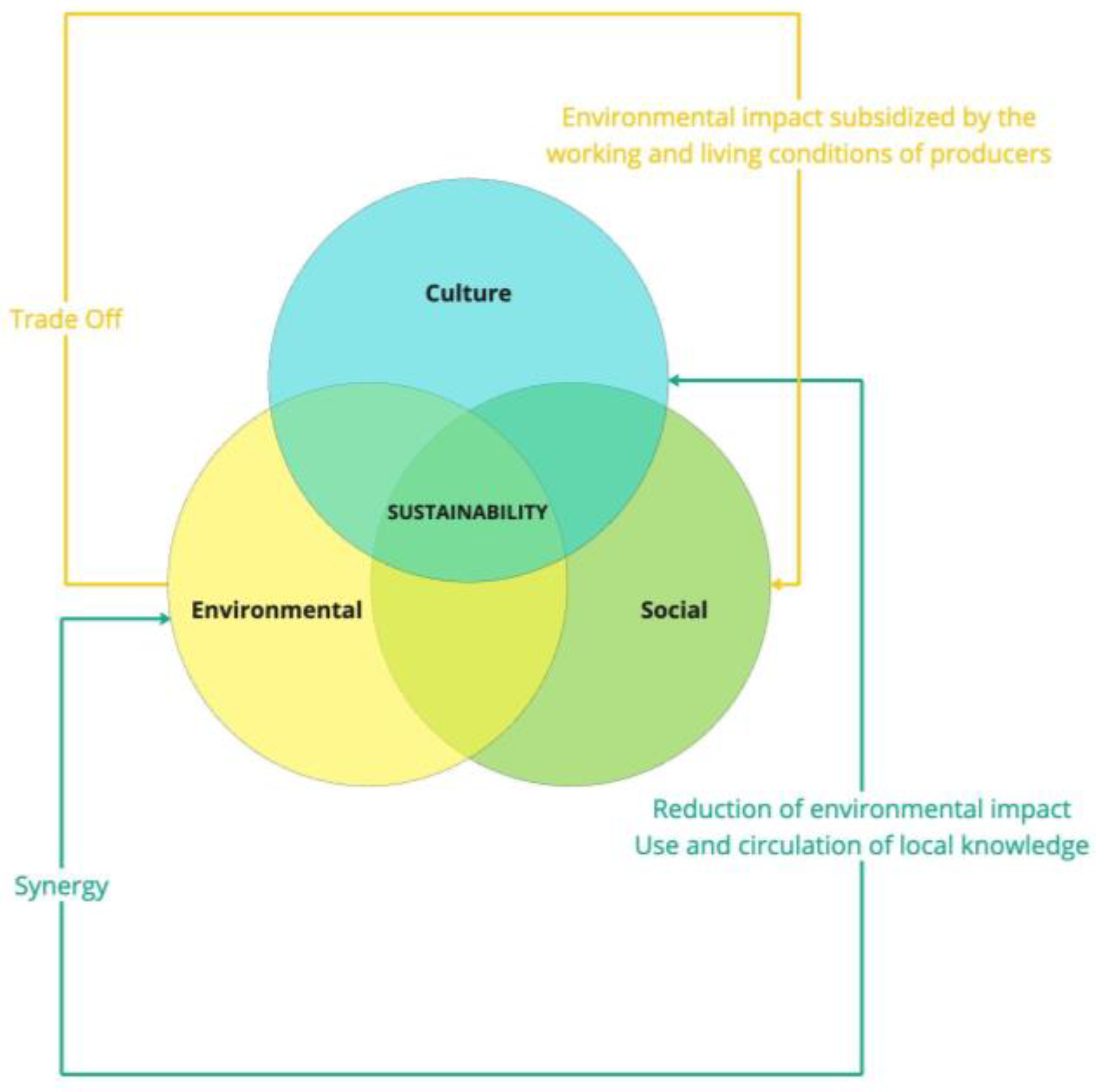

The interaction of the results will be expressed in the form of trade-offs or synergies [

24] with the objective to avoid burden shifting, meaning moving impacts from one dimension to another, or enhancing impacts in several dimensions at the same time.

By integrating the findings of the environmental LCA (carbon footprint), the social LCA (social performance), and the identified cultural meanings, we presented below a preliminary relation between environmental impacts, social impacts, and cultural meanings. To illustrate this, the results of the moulded clay brick (artisanal production) and the extruded clay brick (semi-mechanised production) are used as case studies.

The results of the two types of life cycle assessments, categorised by production method, reveals that while CO2-eq emissions are lower in moulded clay brick artisanal production (

Figure 1) and the impact on human well-being is notably higher (

Table 4). Conversely, in extruded clay brick semi-mechanised production, there is an increase in emissions (

Figure 1), but a decrease in the impact on human well-being, resulting in a more performance-neutral outcome (

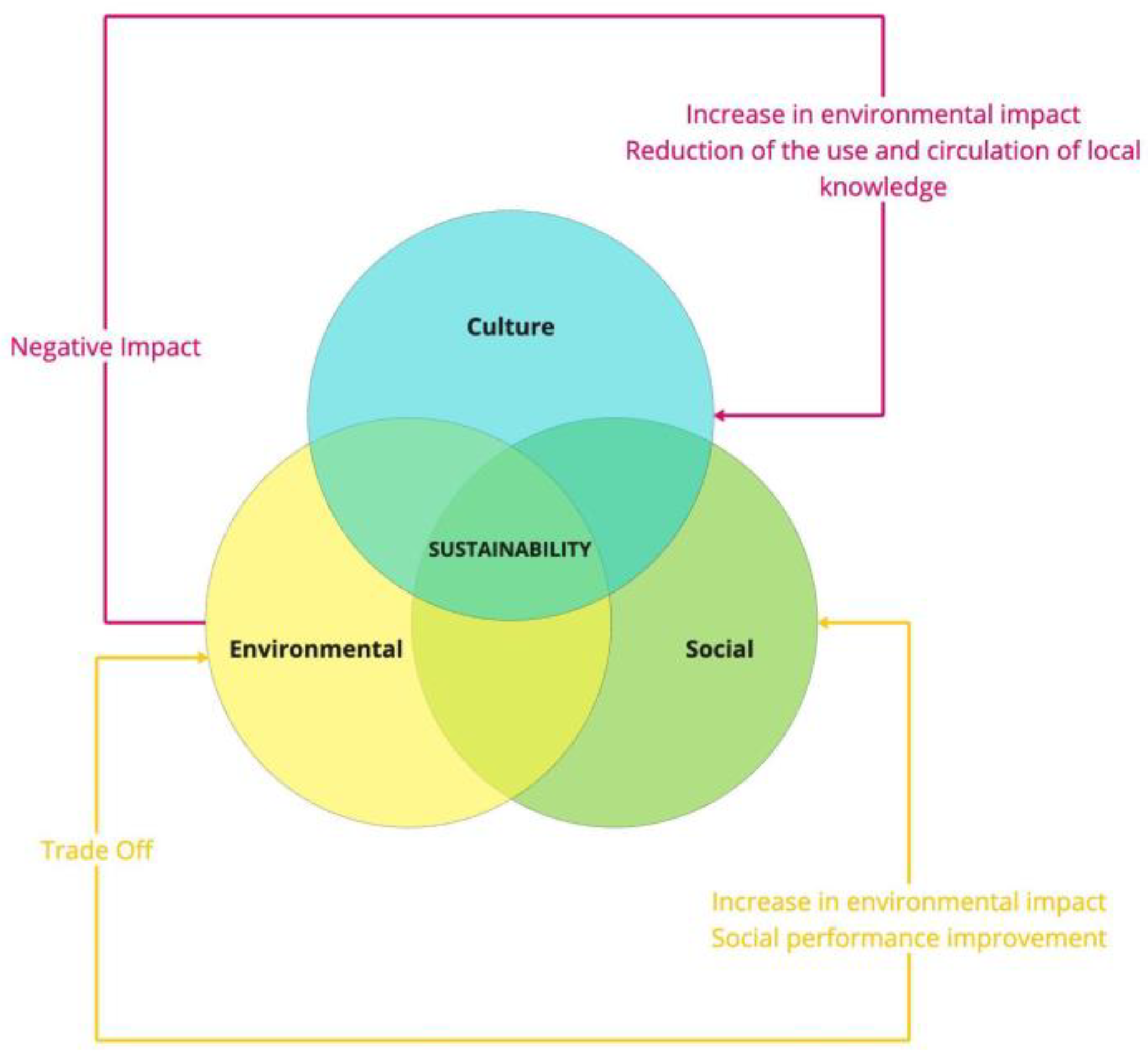

Table 4). Additionally, mechanization reduces the necessity for local knowledge, thereby undermining the continuity of knowledge transmission and the cultural identity tied to artisanal production.

This integrated assessment indicates a clear trade-off [

24] between social and environmental dimensions, where the direction of this trade-off is determined by the type of production. The positive quality of artisanal production (reduction of emissions) is mainly possible by enhancing its negative quality (high impact on producers' well-being). The positive quality of semi-mechanized production (reduced impact on producers' well-being) is mainly possible by enhancing its negative quality (increased emissions).

To gain a deeper understanding of the cultural aspects, and understand how these combine with the trade offs mentioned above, two key cultural meanings within the artisanal production process were considered. These are the transmission of knowledge through the family and the concept of family work. These two concepts allowed to identify a potential cultural impact, which can be observed in the effect that the production of concrete blocks has on the conditions that enable the production of artisanal materials and the identity of the producers themselves.

The semi-mechanised production process of concrete blocks requires a specific machinery, materials, workers and knowledge that increasingly separates the producer from their immediate territory and the techniques and knowledge that circulate within it. This consequently weakens the generation of an identity that links producers with the territory and the available resources.

This raises the question of whether the semi-mechanised production process is having an adverse effect on the cultural identity of the artisanal producers. The presence of semi-mechanised production has a considerable effect on the viability of traditional methods of material production, particularly those that do not utilize earth, such as the production of concrete blocks.But the focus should not be solely on the cultural impact that the mechanization of production processes can generate. It is also important to take into account the benefits that this may have, especially related to the reduction of the workload and the reduction of ergonomic risks.

In addition to the evident impact of semi-mechanization on artisanal production, several spaces for the transmission of knowledge related to this type of production are also affected. As previously discussed in the concept of the labor force outside the family circle, semi-mechanised production significantly diminishes the role of family work. Consequently, the workshop, which traditionally served as a conduit for transmitting knowledge about artisanal production through the family, is now severely compromised.

In the case of semi-mechanized production materials using earth there is a lower impact since there is still a connection through knowledge that allows transforming the raw material into a construction material. As mentioned before, several producers of tiles and extruded brick (semi-mechanized production) use knowledge of artisanal production to achieve the right mix of soil types to produce the materials.

However, it is yet unclear how these prospective cultural impacts may interact with the social and environmental dimension. A synergy between the environmental and cultural dimensions (

Figure 10) was identified in the analyzed workshops. A synergy that occurs due to the use of artisanal production of construction materials in which the circulation of knowledge generated in the territory is maintained. These give identity to the producers and allow the transformation of available resources into construction materials, generating a lower amount of emissions than those generated in semi-mechanized production processes. This should be taken into account including the trade off between the environmental and social dimension mentioned in the previous paragraphs. Since the performance of artisanal workshops is far below the neutral performance (

Table 4).

When this relation between the environmental and cultural dimension occurs through semi-mechanized production, a different effect is generated. The trade off between the environmental and social dimensions mentioned at the beginning of this section should also include a possible impact on the cultural dimension (

Figure 11). Since the usefulness and circulation of the knowledge generated in the territory is drastically reduced, which directly affects the conditions that make possible the generation of the identity of the artisanal producers. This is due to the use of machines that are a key part of the production of materials such as concrete blocks, machines that demand a knowledge that is not generated in the territory and does not correspond with the identity of the artisanal producers.

The results obtained and the connections identified between the different dimensions of sustainability have only been possible thanks to two key elements of the project. First the collection of local data, which was vital in the construction of environmental and social life cycle inventories and the producers' discourses for the ethnographic analysis. This local data provides a profound understanding of the sustainability of these processes at the local level and with significant territorial relevance. The second key element is the use of the interdisciplinary approach, which allows us to put different types of data into dialogue to explain the same phenomenon. This also implies a complex interpretation process, since we do not talk about the social, environmental and cultural dimensions in isolation. We speak simultaneously of all three and how they interact with each other.

Finally, several questions arise from the synergies, trade offs and impacts identified: how to improve working conditions within artisanal production? What strategies could be used to achieve this without increasing the environmental impact and maintaining the use and circulation of the knowledge generated in the territory by artisanal producers?. In other words, how do we convert trade-offs into synergies in order to develop a production process that takes advantage of the potential of artisanal production and semi-mechanized production? One that, at the very least, makes it possible to achieve a neutral performance in the majority of social impact subcategories, which significantly reduces the impact on the social dimension. Additionally, there is a need to investigate production processes that can integrate the techniques, knowledge, and skills developed by artisanal producers with technological innovations that do not result in a significant increase in environmental impact.

It is certain that finding a balance between the dimensions of sustainability that were analyzed in this research implies once again the use of the interdisciplinary approach so as not to fall into simplifications that lead us to prioritize one dimension over another, generating once again the imbalance that we have evidenced, thus enabling the design of strategies that allow the development of a sustainable construction sector.

A sustainable construction sector in which the selection of construction materials is not only based on economic criteria of cost, market availability and aesthetics, but also includes the three dimensions of sustainability that have been analyzed in this research. Promoting the use of materials with less environmental impact, that contribute to improve the working conditions in the production process and that respond effectively to the housing needs of the communities with cultural pertinence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.M., E.C., M.G., P.V. and D.S.; methodology, J.S.M., K.P., J.A., E.C., M.G., P.V. and D.S.; validation, J.S.M., C.M., E.C. and D.S.; formal analysis, J.S.M, E.B., K.P., C.M. and E.C.; investigation, J.S.M., E.B., K.P., J.A., C.M., E.C., M.G., P.V. and D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S.M. and E.C.; writing—review and editing, J.S.M., C.M., E.C., M.G., P.V. and D.S.; supervision, M.G., P.V and D.S.; project administration, M.G., P.V and D.S.; funding acquisition, M.G., P.V. and D.S