Submitted:

23 February 2024

Posted:

23 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

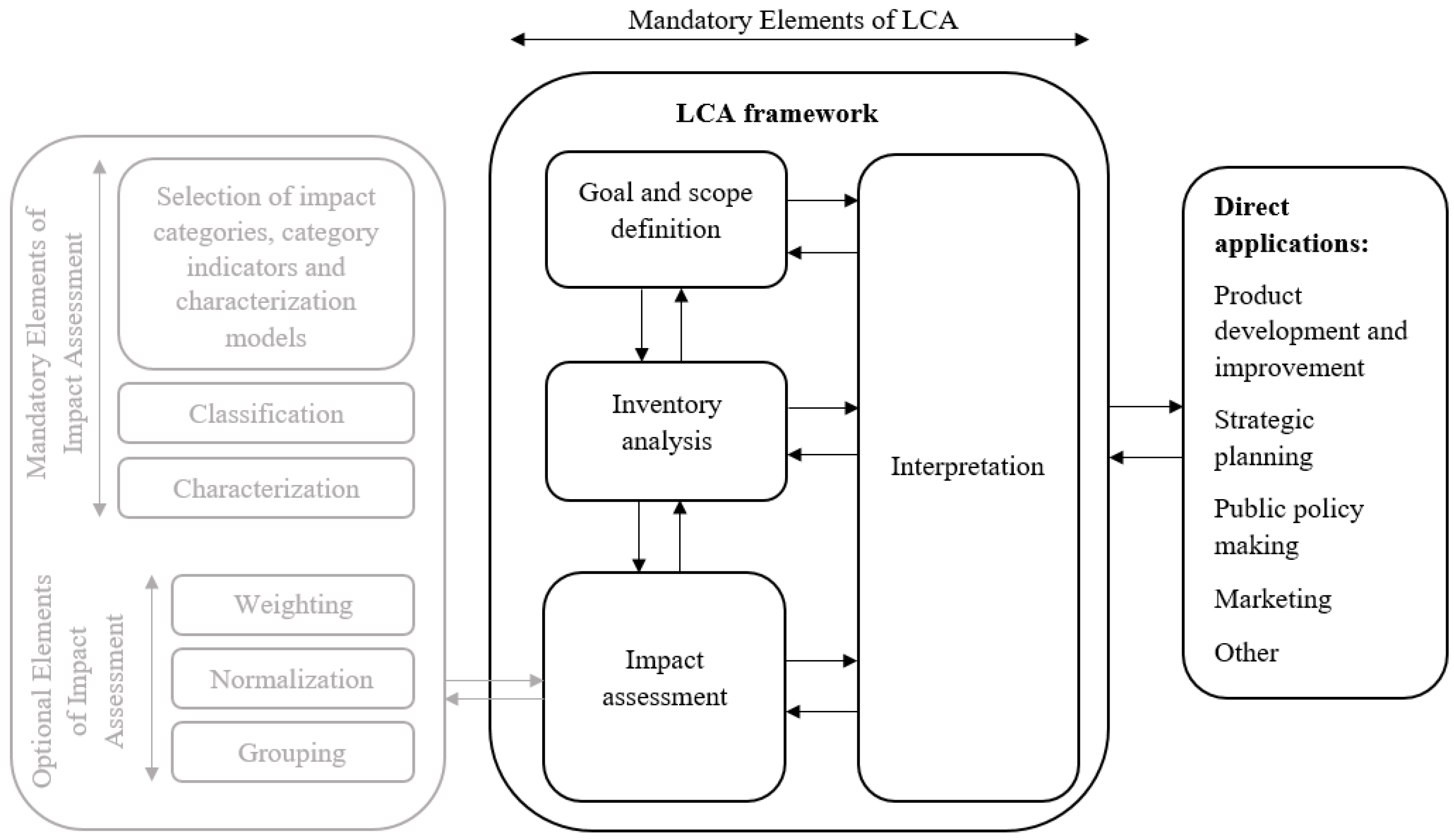

2.1. Life Cycle Assessment

2.2. Environmental Impact Calculation Method

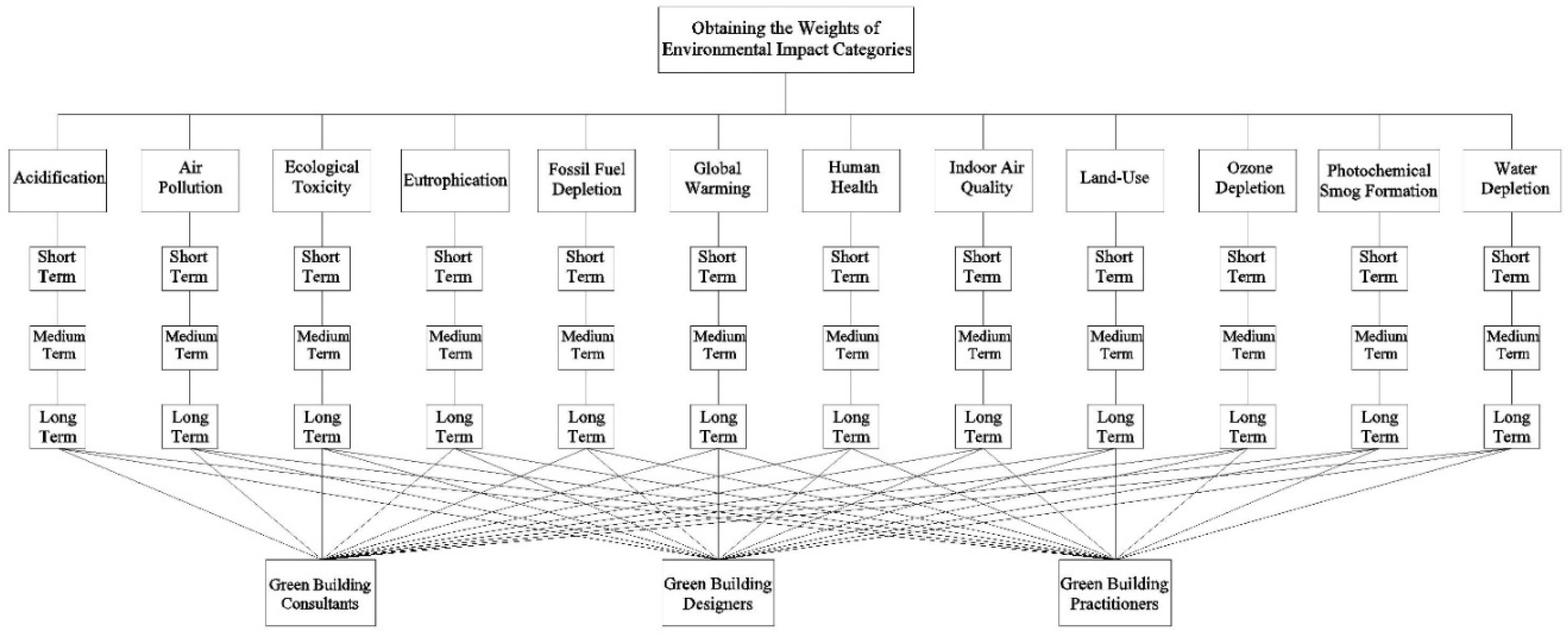

2.3. Weighting Calculation Method: Analytical Hierarchy Process

- The requirement for the pairwise comparison matrix to be consistent is that its maximum eigenvalue (λmax) is equal to the matrix size (n) [40]. The consistency ratio of the pairwise comparison matrix is calculated with the following equation [41]. If CR<0,1, the matrix is consistent; otherwise, decision-makers need to revise their judgments in the pairwise comparison matrix until obtaining acceptable consistency [42].

2.4. Normalization Factors Calculation Method

3. Results

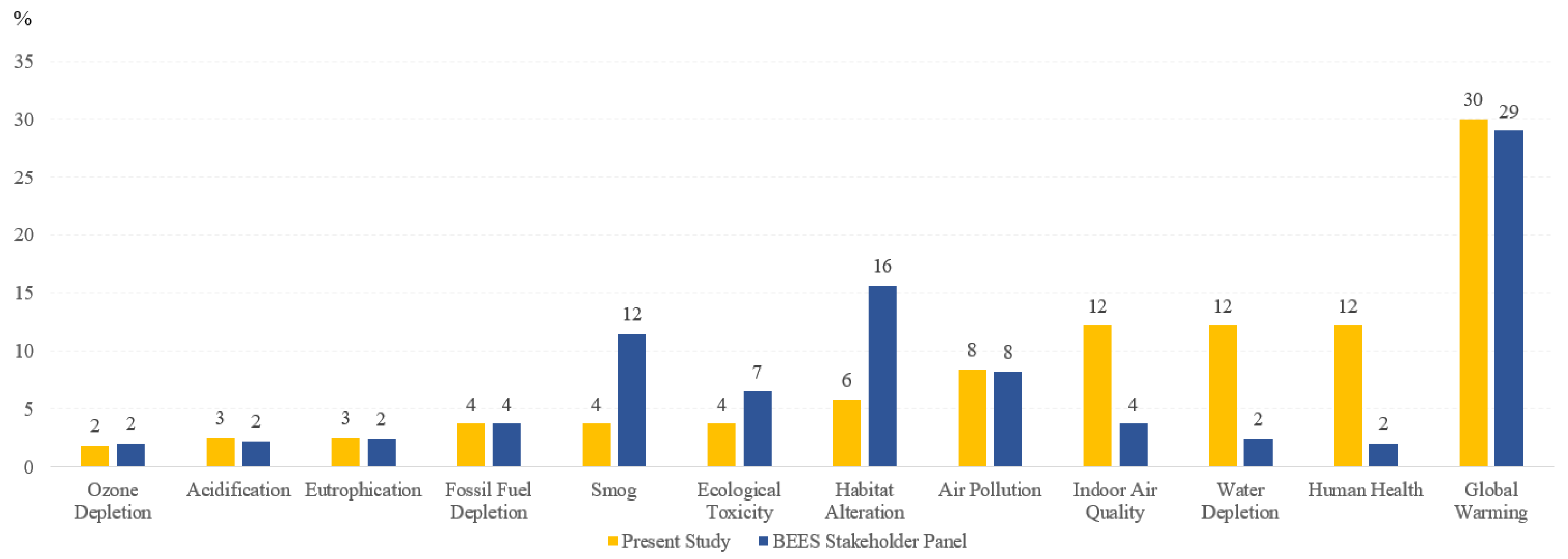

3.1. Weighting Reference Values

3.1. Weighting Reference Values

3.2.1. Calculation of Global Warming Normalization Reference Information Value

3.2.2. Calculation of Air Pollution Normalization Reference Information Value

3.2.3. Calculation of Acidification Normalization Reference Information Value

3.2.4. Calculation of Water Depletion Normalization Reference Information Value

4. Discussion

- The case study LCA’s goal and scope definition: The goal of the case study is to determine the environmental performance of the building materials given in Table 4 in twelve environmental impact categories regarded in the study.

- 2.

- The case study LCA’s inventory analysis: As mentioned before, there is no platform, no database, no legal obligation or encouraging application where the inventory data within the life cycle of building materials are declared in Turkey. For this reason, the life cycle inventory data of the building materials given in Table 4 were obtained from the BEES Online database while performing the case study within the scope of the study.

- 3.

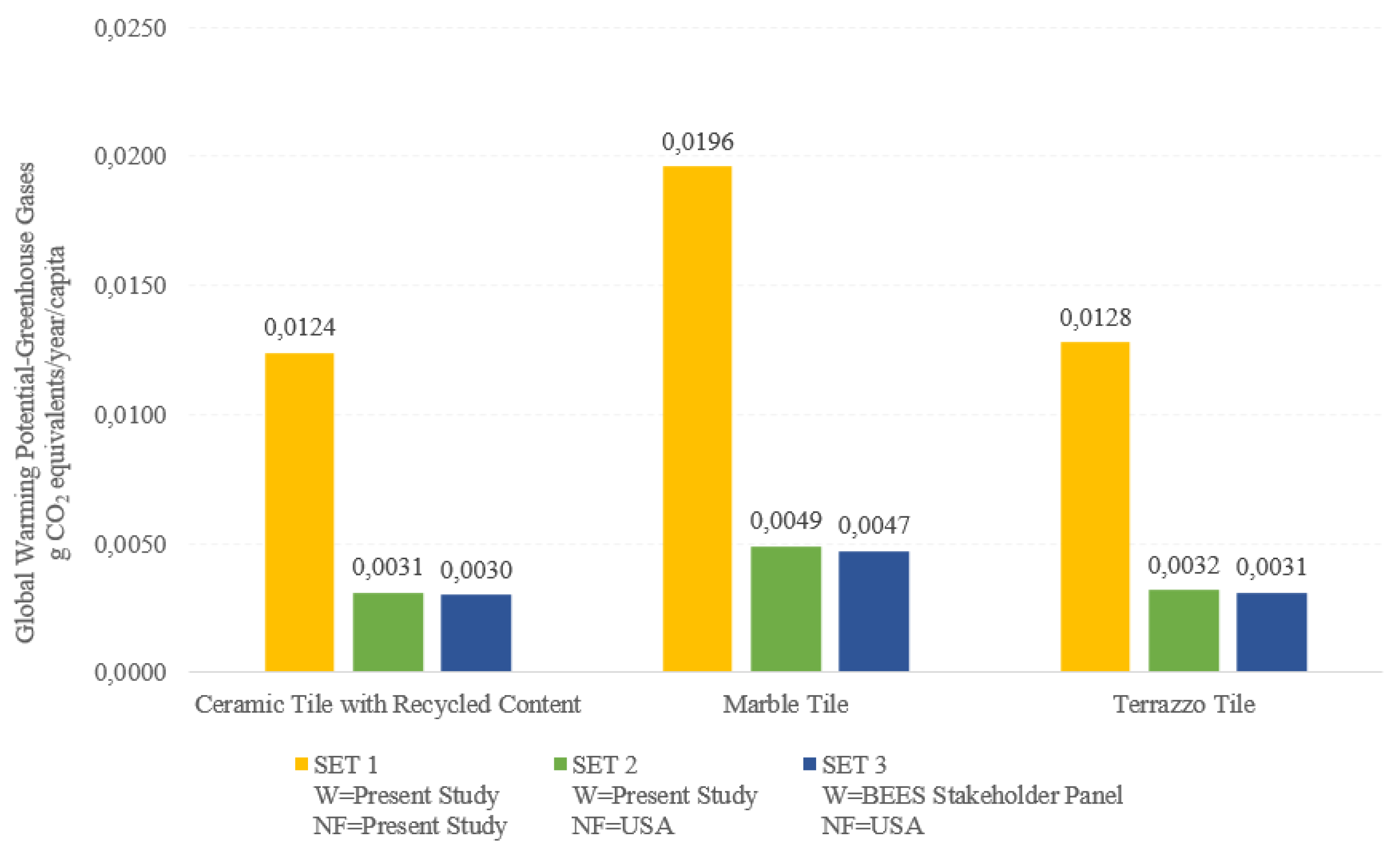

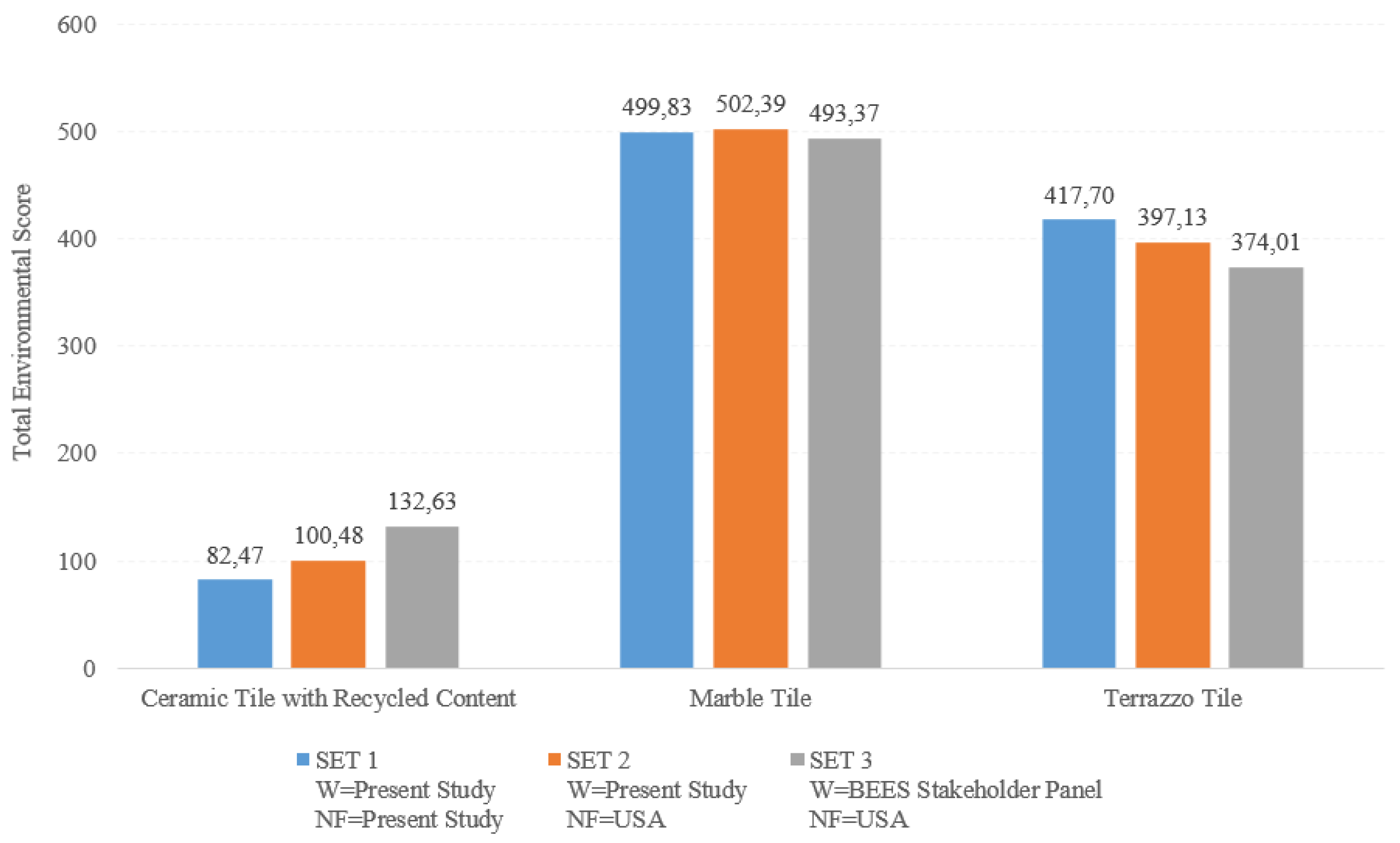

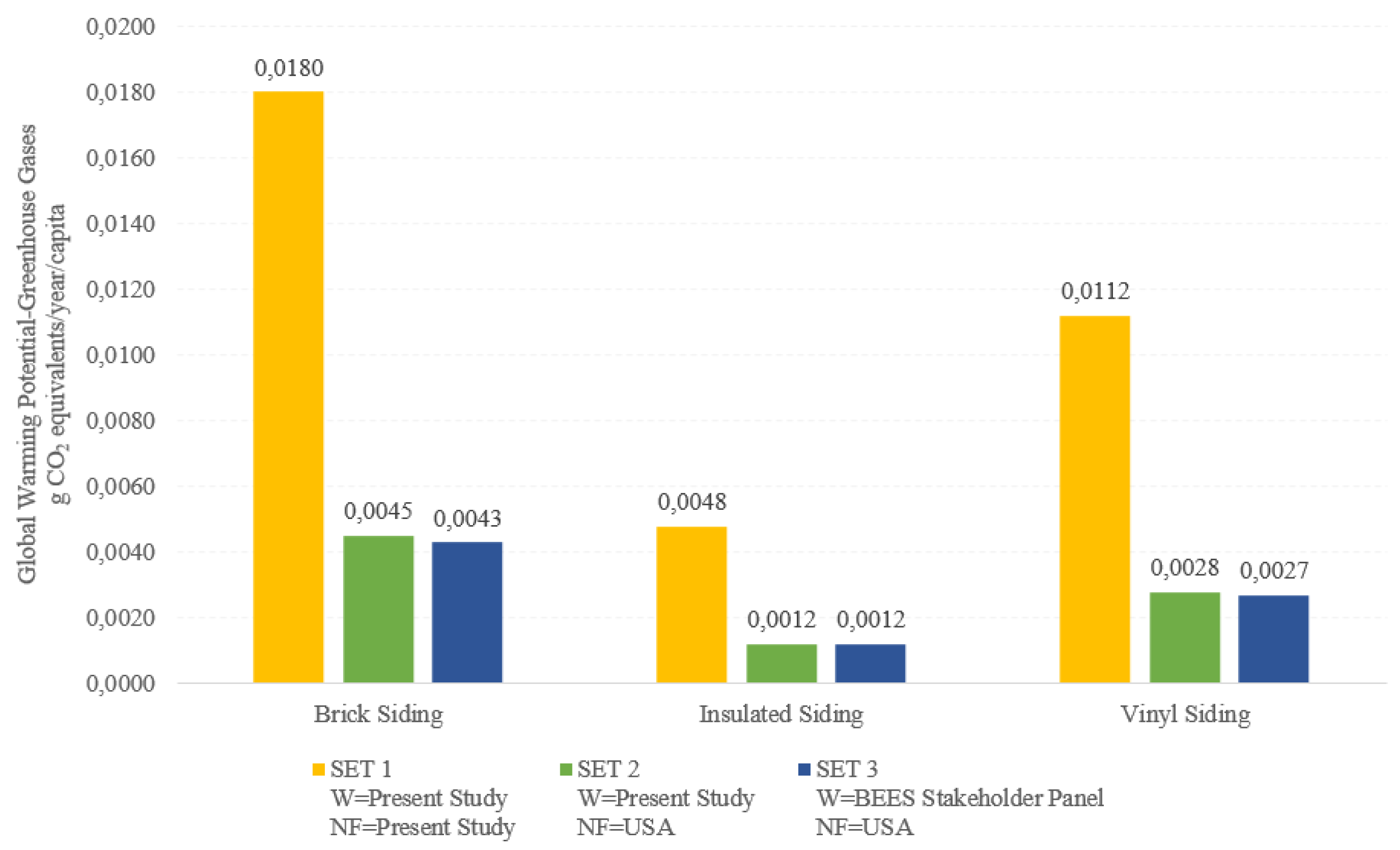

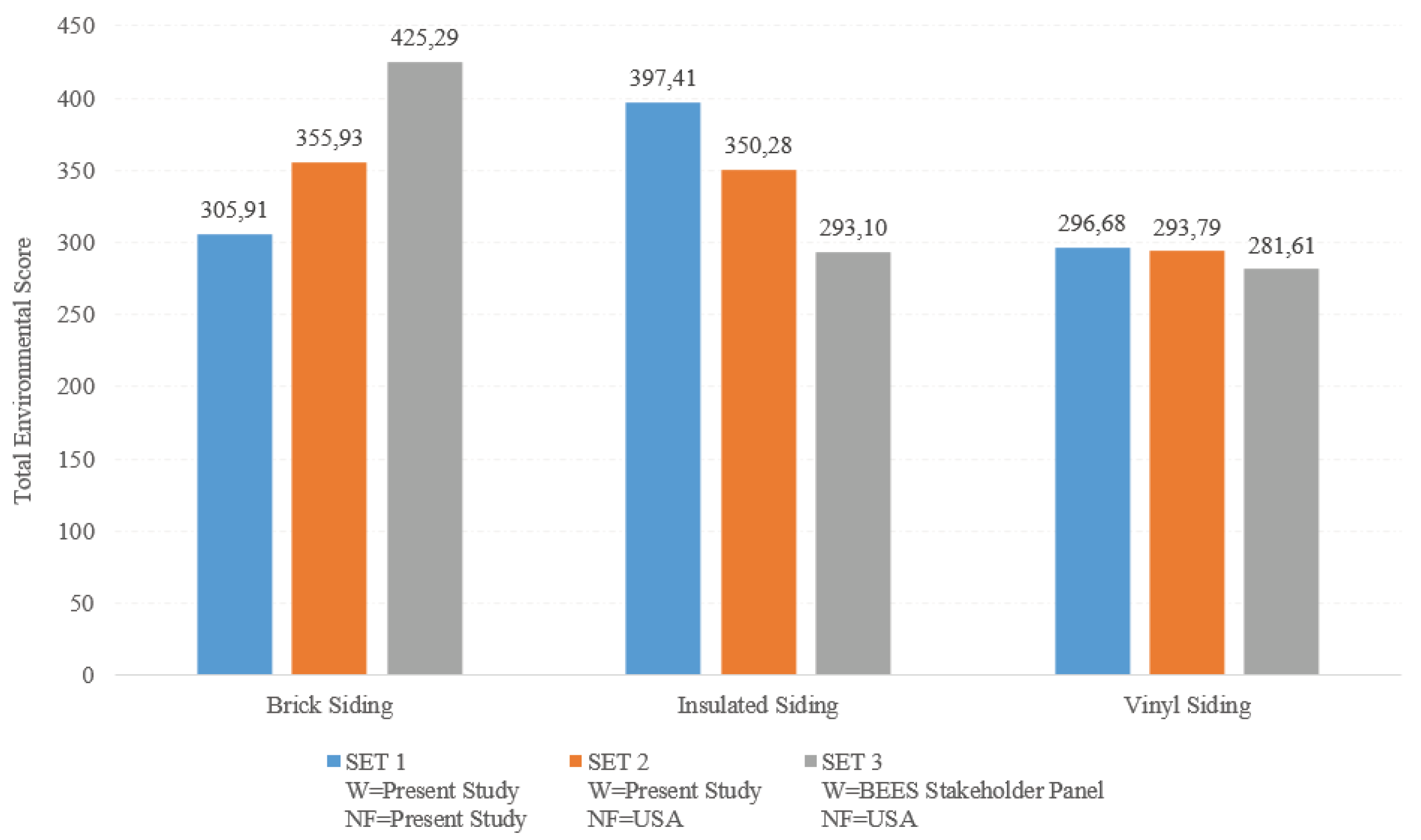

- The case study LCA’s impact assessment: The total environmental score is calculated by summing the effects into twelve environmental impact categories of the building materials evaluated in the case study. Equation 1 to equation 4 were used to calculate total environmental scores. In order to show the importance of regional adaptation of the reference information values calculated in the study, the total environmental scores of the building materials in Table 4 were calculated by using different weights and normalization values.

- 4.

- The case study LCA’s impact interpretation: Set 1 calculation for Group 1 and Group 2 building materials reflect calculations using weights and normalization reference information obtained in the present study. Set 2 calculations were made to show how there would be differences in the evaluations if only the weights were calculated and normalization values were not calculated for Turkey within the scope of the study. Set 3 calculations showed how the results would be affected if the values defined in BEES Online were used directly, without obtaining weights and normalization values for Turkey.

5. Conclusions

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| AHP | Analytical Hierarchy Process |

| BEES | Building for Environmental and Economic Sustainability |

| CBAM | Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism |

| CCAC | Climate and Clean Air Coalition |

| CFC | Chlorofluorocarbon |

| CLRTAP | Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution |

| EMEP | European Monitoring and Evaluation Program |

| EU | European Union |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| SETAC | Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry |

| Turkiye IMSAD | Association of Turkish Construction Material Producers |

| TurkStat | Turkish Statistical Institute |

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Montanarella, L.; Panagos, P. The Relevance of Sustainable Soil Management within the European Green Deal. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, M.; Pisani-Ferry, J.; Shapiro, J.; Tagliapietra, S.; Wolff, G.B. The Geopolitics of the European Green Deal; Bruegel Policy Contribution, 2021.

- Association of Turkish Construction Material Producers. Turkey IMSAD Building Industry Report 2020; İMSAD-R/2021-07/390; 2021; pp 1–204.

- Pacheco-Torgal, F.; Labrincha, J.A. The Future of Construction Materials Research and the Seventh UN Millennium Development Goal: A Few Insights. Construction and Building Materials 2013, 40, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, H.; Zhang, G.; Setunge, S.; Bhuiyan, M.A. Life Cycle Assessment of Shipping Container Home: A Sustainable Construction. Energy and Buildings 2016, 128, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Teoh, B.K.; Wu, M.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L. Data-Driven Estimation of Building Energy Consumption and GHG Emissions Using Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Energy 2023, 262, 125468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission. Workshop on Integrated Product Policy; Final Report; 1998.

- Guinée, J.B.; Heijungs, R.; Huppes, G.; Zamagni, A.; Masoni, P.; Buonamici, R.; Ekvall, T.; Rydberg, T. Life Cycle Assessment: Past, Present, and Future. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carretero-Ayuso, M.J.; García-Sanz-Calcedo, J. Comparison between building roof construction systems based on the LCA. Revista de la Construcción. Journal of Construction 2018, 17, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uygunoğlu, T.; Sertyeşilişik, P.; Topçu, İi. B. 20 - Methodology for the Evaluation of the Life Cycle in Research on Cement-Based Materials. In Waste and Byproducts in Cement-Based Materials; de Brito, J., Thomas, C., Medina, C., Agrela, F., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Civil and Structural Engineering; Woodhead Publishing, 2021; pp 601–615. [CrossRef]

- ISO 14044:2006. Environmental Management - Life Cycle Assessment - Requirements and Guideline, Brussels.

- EN 15804:2012+A2:2019. Sustainability of Construction Works. Environmental Product Declarations. Core Rules for the Product Category of Construction Products, Brussels.

- Estokova, A.; Vilcekova, S.; Porhincak, M. Analyzing Embodied Energy, Global Warming and Acidification Potentials of Materials in Residential Buildings. Procedia Engineering 2017, 180, 1675–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Torgal, F.; Jalali, S. Toxicity of Building Materials: A Key Issue in Sustainable Construction. International Journal of Sustainable Engineering 2011, 4, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.; Butt, A.; Khalid, I.; Alam, R.U.; Ahmad, S.R. Smog Analysis and Its Effect on Reported Ocular Surface Diseases: A Case Study of 2016 Smog Event of Lahore. Atmospheric Environment 2019, 198, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CACC (Climate and Clean Air Coalition). Mitigating Black Carbon and Other Pollutants from Brick Production; Climate and Clean Air Coalition, 2019; pp 1–15.

- Alyüz, B.; Veli, S. İç Ortam Havasında Bulunan Uçucu Organik Bileşikler ve Sağlık Üzerine Etkileri. Trakya Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Dergisi 2006, 7, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Häfliger, I.-F.; John, V.; Passer, A.; Lasvaux, S.; Hoxha, E.; Saade, M.R.M.; Habert, G. Buildings Environmental Impacts’ Sensitivity Related to LCA Modelling Choices of Construction Materials. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 156, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, P.A.; Oman, L.D.; Douglass, A.R.; Fleming, E.L.; Frith, S.M.; Hurwitz, M.M.; Kawa, S.R.; Jackman, C.H.; Krotkov, N.A.; Nash, E.R.; Nielsen, J.E.; Pawson, S.; Stolarski, R.S.; Velders, G.J.M. What Would Have Happened to the Ozone Layer If Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) Had Not Been Regulated? Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2009, 9, 2113–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCAC(Climate and Clean Air Coalition). HFC Initiative; Climate and Clean Air Coalition, 2015; pp 1–2.

- (21) Marzouk, M.; Abdelkader, E.M.; Al-Gahtani, K. Building Information Modeling-Based Model for Calculating Direct and Indirect Emissions in Construction Projects. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 152, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Chae, C.U. Environmental Impact Analysis of Acidification and Eutrophication Due to Emissions from the Production of Concrete. Sustainability 2016, 8, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. M.; Rahman, M. A.; Haque, M. M.; Rahman, A. Sustainable Water Use in Construction. In Sustainable Construction Technologies; Tam, V. W. Y., Le, K. N., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann, 2019; pp 211–235. [CrossRef]

- McCormack, M.; Treloar, G.J.; Palmowski, L.; Crawford, R. Modelling Direct and Indirect Water Requirements of Construction. null 2007, 35, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, A.Y. The Water Footprint of Industry. In Assessing and Measuring Environmental Impact and Sustainability; Klemeš, J.J., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, 2015; pp. 221–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, A.-M. Concrete and Not so Concrete Impacts. Information Ecology 1998, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Esin, T.; Cosgun, N. A Study Conducted to Reduce Construction Waste Generation in Turkey. Building and Environment 2007, 42, 1667–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, D.; Kreiss, K. Building-Related Illnesses; CRC Press, 2006; pp 763–810. [CrossRef]

- Crook, B.; Burton, N.C. Indoor Moulds, Sick Building Syndrome and Building Related Illness. Fungal Biology Reviews 2010, 24, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darçın, P.; Balanlı, A. Yapı Ürünlerinden Kaynaklanan Uçucu Organik Bileşiklerin Yapı Biyolojisi Açısından İrdelenmesi. Megaron 2018, 13, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorlu, K.; Tıkansak Karadayı, T. İç Mekan Hava Kalitesinde Yapı Malzemelerinin Rolü. Sinop Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Dergisi 2020, 5, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006. Environmental Management-Life Cycle Assestment-Principles and Framework, Brussels.

- Klöpffer, W.; Grahl, B. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): A Guide to Best Practice; John Wiley & Sons, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Lippiatt, B.C. Building for Environmental and Economic Sustainability Technical Manual and User Guide; National Institute of Standards and Technology: United States of America, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. Fundamentals of the Analytic Hierarchy Process. In The Analytic Hierarchy Process in Natural Resource and Environmental Decision Making; Schmoldt, D.L., Kangas, J., Mendoza, G.A., Pesonen, M., Eds.; Managing Forest Ecosystems; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2001; pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-M.; Liu, J.; Elhag, T.M.S. An Integrated AHP–DEA Methodology for Bridge Risk Assessment. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2008, 54, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulong, L.; Xiande, W.; Zhongfu, L. Safety Risk Assessment on Communication System Based on Satellite Constellations with the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Aircraft Engineering and Aerospace Technology 2008, 80, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Hu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Mahadevan, S. Supplier Selection Using AHP Methodology Extended by D Numbers. Expert Systems with Applications 2014, 41, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, R.W. The Analytic Hierarchy Process—What It Is and How It Is Used. Mathematical Modelling 1987, 9, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Relative Measurement and Its Generalization in Decision Making Why Pairwise Comparisons Are Central in Mathematics for the Measurement of Intangible Factors the Analytic Hierarchy/Network Process. Rev. R. Acad. Cien. Serie A. Mat. 2008, 102, 251–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansah, R.H.; Sorooshian, S.; Bin Mustafa, S. Analytic Hierarchy Process Decision Making Algorithm. Global Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics 2015. [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, K.; Malak, N.; Zhang, Y.B. Outsourcing Non-Core Assets and Competences of a Firm Using Analytic Hierarchy Process. Computers & Operations Research 2007, 34, 3592–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryberg, M.; Vieira, M.D.M.; Zgola, M.; Bare, J.; Rosenbaum, R.K. Updated US and Canadian Normalization Factors for TRACI 2.1. Clean Techn Environ Policy 2014, 16, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Available online: www.nist.gov (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- TurkStat (Turkish Statistical Institute). Address Based Population Registration System 2018; Report No. 30709; 2019.

- TurkStat (Turkish Statistical Institute). Greenhouse Gas Emission Statistics 1990-2019; Report No. 37196; 2020.

- Turkish Ministry of Environment and Urbanization and Climate Change. Turkey’s 5th Statement on Climate Change, Annual Informative Inventory Report for Turkey for the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe; 2021; p 324.

- EMEP Centre on Emission Inventories and Projections. Available online: www.ceip.at/data-viewer (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- TurkStat (Turkish Statistical Institute). Municipal Water Statistics 2018; Report No. 30668; 2019.

| Air pollutants | NOx | >PM10 | <=PM10 | Unspecified PM | SOx |

| Emission factors | 0,002 | 0,046 | 0,083 | 0,046 | 0,014 |

| Emissions | 7,85E+11 g | NA | 239,08E+9 g (PM10) 193,64E+9 g (PM2.5) |

NA | 2,52E+12 g |

| Air pollution index | 1 570 000 000 | - | 35 915 760 000 | 35 266 000 000 | |

| Total | 72 751 760 000 microDALYs/year | ||||

| Population (capita) | 82 003 882 | ||||

| Normalization reference information value | 887,17 microDALYs/year/capita | ||||

| NA: not available mi: inventory input i as in grams CPi: microDALYs per functional unit of inventory input i (as gram in this table) | |||||

| Acidifiers | NH3 | HCl | HCN | HF | H2S | NOx | SOx | H2SO4 |

| Emission factors | 95,49 | 44,70 | 60,4 | 81,26 | 95,9 | 40,04 | 50,79 | 33,30 |

| Emissions | 7,28E+11 g | NA | NA | NA | NA | 7,85E+11 g | 2,519E+12 g | NA |

| Acidification index | 6,952E+13 | - | - | - | - | 3,143E+13 | 1,279E+14 | - |

| Total | 2,289E+14 H+ eq./year | |||||||

| Population (capita) | 82 003 882 | |||||||

| Normalization reference information value | 2 791 186,52 H+ eq./year/capita | |||||||

| NA: not available mi: inventory input i as in grams APi: millimoles of hydrogen ions per functional unit of inventory input i (as gram in this table) | ||||||||

| Environmental impact categories | Reference unit | Present Study | USA [44] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidification | H+ eq./year/capita | 2 791 186,52 | 7 800 200 000 |

| Air Pollution | microDALYs/year/capita | 887,17 | 19 200 |

| Ecological Toxicity | g 2,4-D eq./ year/capita | 43 238,69 | 81 646,72 |

| Eutrophication | g N eq./ year/capita | 27 104,47 | 19 214,20 |

| Fossil Fuel Depletion | MJ energy/year/capita | 300 489,72 | 35 309 |

| Global Warming | g CO2 eq./ year/capita | 6 400 000 | 25 582 640,09 |

| Human Health | g C7H8 eq./ year/capita | 13 357 199,68 | 274 557 555,37 |

| Indoor Air Quality | g TotalVOCs/ year/capita | 35 108,09 | 35 108,09 |

| Land Use | count/acre/capita | 0,002344 | 0,00335 |

| Ozone Depletion | g CFC-11 eq./ year/capita | 2,439 | 340,19 |

| Photochemical Smog Formation | g NOx eq./ year/capita | 11 870,17 | 151 500,03 |

| Water Depletion | liters/ year/capita | 81760 | 529 957,75 |

| Groups of Building Materials | Building Material |

|---|---|

| GROUP 1: Floor coverings | Ceramic Tile with Recycled Content |

| Marble Tile | |

| Terrazzo Tile | |

| GROUP 2: Exterior wall finishes | Brick Siding |

| Insulated Siding | |

| Vinyl Siding |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).