1. Introduction

The enhancement of precision for robot arm manipulation remains a core research area for acquiring full autonomy of robots in various sectors such as industrial manufacturing and assembly processes. The next logical progression in this field is to achieve complete autonomy of robotic manipulators through the use of machine learning (ML), artificial neural networks (ANNs), and artificial intelligence (AI) as a whole, given the maturity of image recognition and vision systems [

1,

2]. Numerous attempts have been made to create intelligent robots that can take tasks and execute accordingly [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Although developing a system with intelligence close to that of humans is still a long way off, robots that can perform specialized autonomous activities, such as intelligent facial emotion recognition [

11], fly in natural and man-made environments [

12], drive a vehicle [

13], swim [

14], carry boxes and material in different terrains [

15], and pick up and place objects [

16,

17] is already actualized.

However, some challenges must be overcome to achieve this goal. For instance, the mapping complexity from Cartesian space to the joint space of a robot arm increases with the number of joints and linkages that the manipulator has. This is problematic because the tasks assigned to a robotic arm are in Cartesian space, whereas the commands (velocity or torque) are in joint space [

18,

19]. Therefore, if full autonomy of robotic manipulators is the objective, the target-reaching problem is probably one of the most crucial factors that must be addressed.

The field of reinforcement learning, as described in [

20,

21], is a type of machine learning that aims to maximize the outcome of a given system using a dynamic and autonomous trial-and-error approach. It shares a similar objective with human intelligence, which is characterized by the ability to perceive and retain information as knowledge to be used for environment-adaptive behaviors. Central to the reinforcement learning framework are trial-and-error search and delayed rewards, which allow the learning strategy to interact with the environment by performing actions and discovering rewards [

22]. Through this approach, software agents and machines can automatically select the most effective course of action to take in a given circumstance, thus improving performance. Reinforcement learning offers a framework and set of tools for designing sophisticated and challenging-to-engineer behaviors in robotics [

23,

24]. In contrast, the challenges presented by robotic issues serve as motivation, impact, and confirmation of advances in reinforcement learning. Multiple previous works on the implementation of reinforcement learning in the field of robotics depict this fact [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

2. Modeling of Robotic Arm

2.1. Direct Kinematic Model of Robot Arm

The rotation matrices in the DH coordinate frame represent the rotations about the X and Z axes. The rotation matrices for these axes are, respectively, given as:

and

The homogeneous transformation matrix (

) that accounts for rotation and translation is given as:

where:

The rotation matrix () represents the orientation of the i-th frame relative to the -th frame.

represents the center of the link frame with components (, , and ).

2.1.1. DH Axis Representation

The four DH parameters describe the translation and rotation relationship between two consecutive coordinate frames as follows:

d: a distance between the current frame and the previous frame along the Z-axis,

(): an angle between the X-axis of the previous frame and the X-axis of the current frame about the previous z-axis,

a: a distance between the Z-axes of the current and previous frames.

: an offset of the previous frame from the current frame along the Z-axis of the current frame.

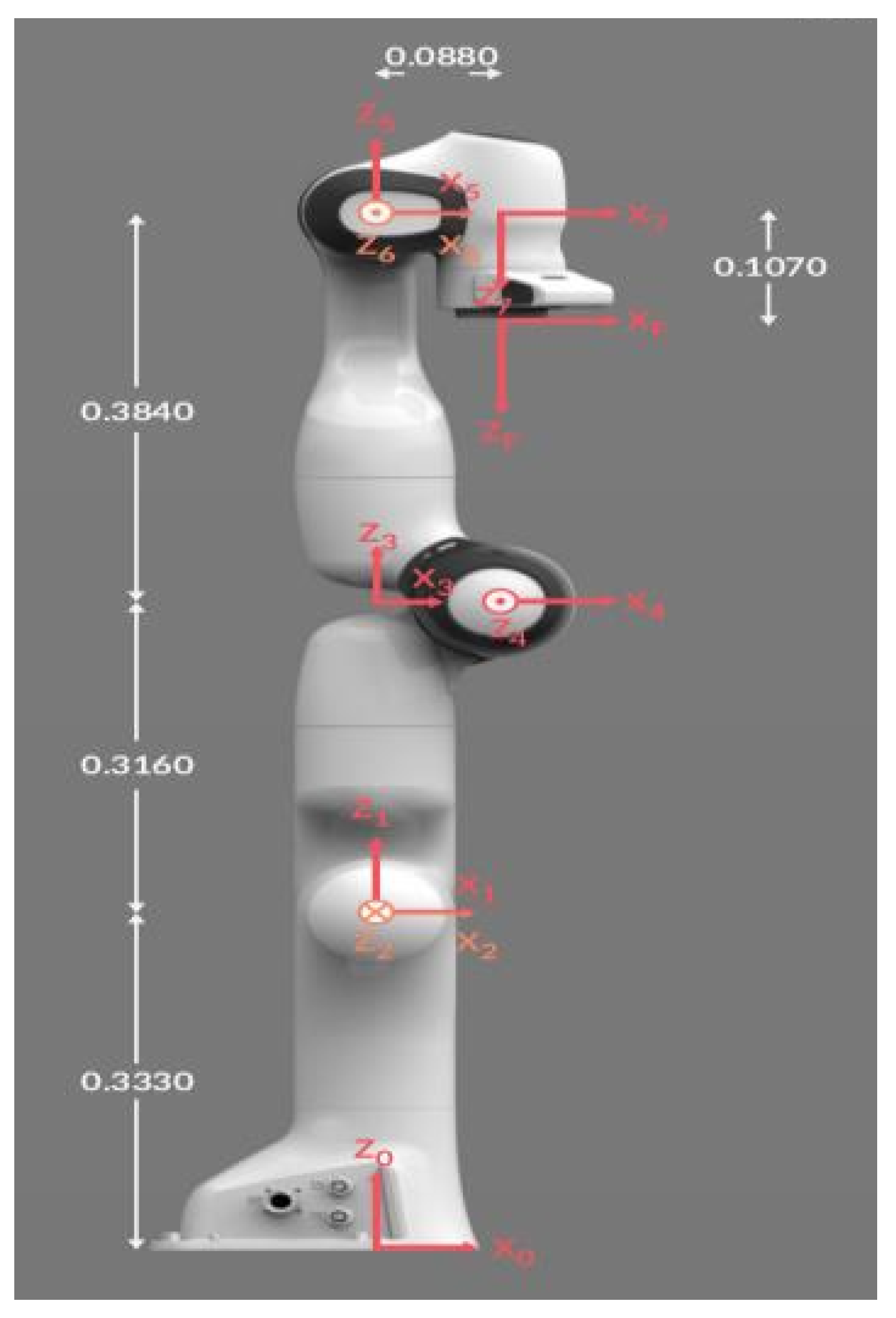

The DH parameters for the Franka Panda robot, shown in

Figure 1 are given in

Table 1. From the above DH parameters and based on the homogeneous transformation matrix

3, the transformation matrix for the Franka Panda robot is derived as.

The orientation and position of the end-effector, respectively, are given by:

and

2.2. Incremental Inverse Kinematics of Robot Arm

The 3D position vector

of the end-effector (EE) is given by:

In case of the Panda robot, there are

active joint angles

With these joint angles(

q) and direct kinematics

, the goal is to solve the inverse kinematics

using incremental inverse kinematics. In incremental inverse kinematics, a direct kinematics is linearized around the current joint angle configuration

as

The goal is to find the change in joint angles (

) that corresponds to a desired change in the end-effector position (

). The linearized form of the direct kinematics equations is expressed as

27, where

The proportionality symbol (∝) indicates that the change in end-effector position is directly related to the change in joint angles. To solve for the change in joint angles, the Jacobian matrix, denoted as

, is utilized. The Jacobian matrix is a matrix of partial derivatives that describes how the end-effector position

depends on the joint angles

. Specifically, the Jacobian matrix is defined as

By multiplying the Jacobian matrix

by the change in joint angles

, an approximation of the change in the end-effector position

is obtained. The joint angles are iteratively updated to minimize the difference between the current end-effector position and the desired end-effector position.This can be efficiently solved around

using the Jacobian.

2.2.1. Steps of Incremental Inverse Kinematics

Given: target pose

Required: joint angles

Define the starting pose

and set up the Incremental inverse kinematics from (3.29)

Determine the deviation relative to the target pose; e.g.

Check for termination; e.g..

Calculate new joint angles

3. Deep Reinforcement Learning Algorithm Design

3.1. Policy Gradient Algorithm

The policy gradient theorem states that the expected return to the policy parameters can be calculated as the sum of the action value function

multiplied by the policy function

, summed over all states

s and actions

a, and weighted by the stationary distribution of states

.

where:

Objective function(): Represents the expected cumulative reward obtained by following the policy in the given environment. The objective function is optimized by adjusting the parameter to maximize the expected cumulative reward.

Discounted state distribution(): Represents the probability of being in a particular state

s under the policy

. Mathematically,

where

when starting from

and following policy

for

t time steps.

Action-value function (( ): Represents the expected cumulative reward obtained by taking action a in state s and following the policy thereafter.

Policy function(): Represents the probability of taking action a in state s under the parameterized policy .

The policy gradient theorem helps to solve this problem by providing a formula for the gradient of the expected return to the policy parameters. This formula involves the stationary distribution of the Markov chain and is given by:

where

is the state-action value function for policy

.

3.1.1. Derivation of Policy Gradient Theorem

using derivative product rule:

The steps of the derivation using, the derivative product rule from equation (4.6) are as follows:

Step 1: Apply the derivative product rule:

Step 2: Distribute the derivative operator inside the summation:

Step 3: Apply the chain rule to differentiate the product of

and

to

:

Step 4: Simplify the expression by rearranging the terms.

After applying the derivative product rule, the derivative of the state-value function

to the policy parameter

is:

Extend

by incorporating the future state value. This can be done by considering the state-action pair

and summing over all possible future states

and corresponding rewards

r:

Since

and

r are not functions of

, the derivative operator

can be moved inside the summation over

without affecting these terms.

Next, it is observed that

is the derivative of the state-value function to the policy parameter

at state

. This can be rewritten as

. Here,

represents the probability of transitioning to state

given the current state-action pair

. The following substitution is now made:

Where

Consider the following visiting sequence and identify the probability of changing state

s to state

x using policy

after

k steps as

After discussing the probability for transitioning from state s to state x after a certain number of steps k, the next step is to drive a recursive formulation for .

To accomplish this, a function

is introduced, defined as:

Here, represents the sum of the gradients of the policy to , weighted by the corresponding action-value function .

Consider

as the middle point for

The expression for

can be unrolled as follows:

Eliminating the derivatives of the Q-value function

and inserting objective function

in (4.5), starting from state

Let,

Substituting

in to eqn(4.24)

Normalize

in (4.27),

to be probability distribution as show down bellow:

Since the

is constant, the gradient of the objective function is proportional to the normalized

and

Where

is stationary distribution.

In the episodic case, the constant proportionality

is the average length of an episode; In the continuing case, it is one(1) [

31].

Where

when the distribution of states and actions follows policy

(on policy).

3.1.2. Off-Policy Policy Gradient

Since DDPG is one of the off-policy Policy gradient Algorithms, First let’s talk about off-policy Policy gradient Algorithms in great detail.

The behavior policy for collecting samples is known and labeled as

the objective function sums up the reward over the state distribution defined by this behavior policy:

where

is the stationary distribution of the behavior policy

since

and

is the action-value function estimated about the target policy

. Given that the training observations are sampled by

, the gradient can be rewritten as:

By Derivative product rule.

By ignoring

Where

is the importance weight. Since

is a function of the target policy and, consequently, a function of the policy parameter

, the derivative

must also be computed using the product rule. However, computing

directly is challenging in practice. Fortunately, by approximating the gradient and ignoring the gradient of

, policy improvement can still be guaranteed, and eventual convergence to the true local minimum is achieved.

In summary, when applying policy gradient in the off-policy setting, it can be adjusted by a weighted sum, where the weight is the ratio of the target policy to the behavior policy,

[

31].

3.2. Deterministic Policy Gradient (DPG)

The policy function is typically represented as a probability distribution over actions A based on the current state, making it inherently stochastic. However, in the case of the Deterministic Policy Gradient (DPG), the policy is modeled as a deterministic decision, denoted as . Instead of selecting actions probabilistically, DPG directly maps states to specific actions without uncertainty. Let:

The initial distribution over states

: Starting from state s, the visitation probability density at state after moving k steps by policy .

-

: Discounted state distribution, defined as

The objective function to optimize for is listed as follows:

According to the chain rule, first, take the gradient of

Q with respect to the action

a and then take the gradient of the deterministic policy function

w.r.t.

:

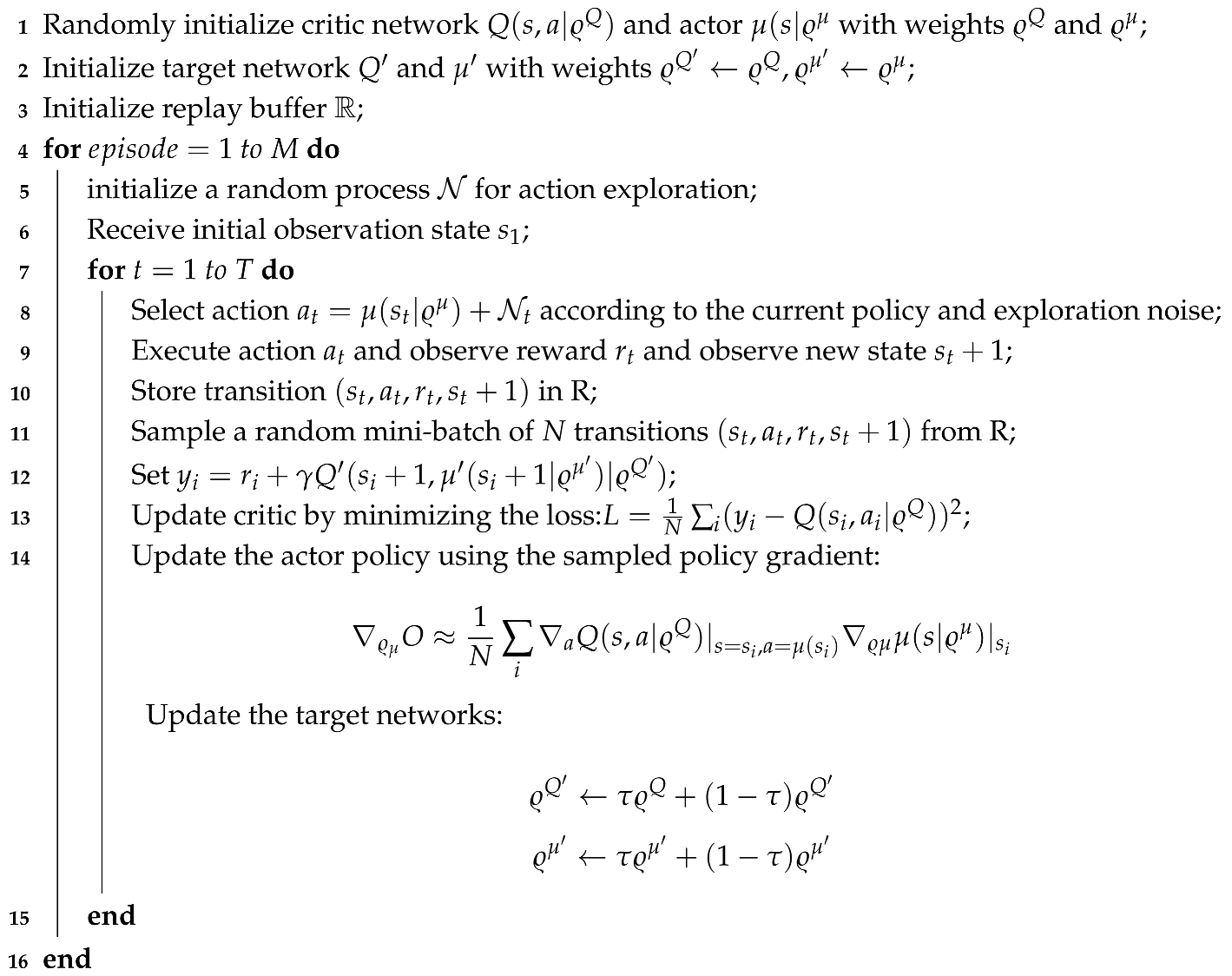

3.3. Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG)

By combining DQN and DPG, DDPG leverages the power of deep neural networks to handle high-dimensional state spaces and complex action spaces, making it suitable for a wide range of reinforcement learning tasks. The original DQN works in discrete space, and DDPG extends it to continuous space with the actor-critic framework while learning a deterministic policy. In order to do better exploration, an exploration policy

is constructed by adding noise

:

Moreover, the DDPG algorithm integrates a sophisticated technique known as soft updates, or conservative policy iteration, to update the parameters of both the actor and critic networks. This revised methodology utilizes a small parameter, denoted as , which is much smaller than 1().

The soft update equation is formulated as

It guarantees that the target network values alter gradually over time, unlike the approach employed in DQN, where the target network remains static for a fixed period.

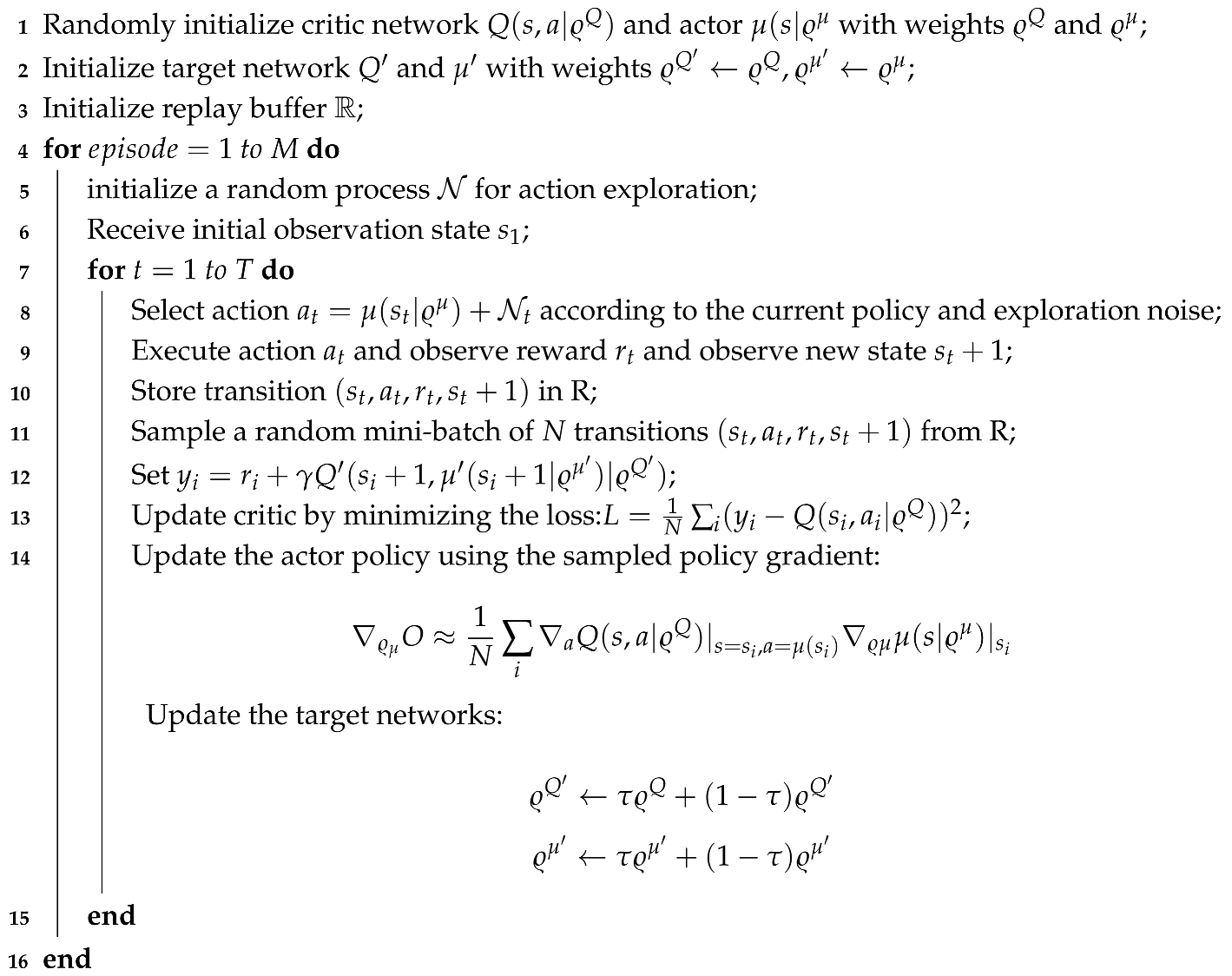

3.4. Working of DDPG Algorithm

|

Algorithm 1: Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient |

|

4. Results And Discussions

4.1. Software Configuration

The deep reinforcement learning agent was trained using Python within a Jupyter Notebook on a Linux Ubuntu 20.04 operating system. The training process spanned approximately 5.415 hours on a modest hardware configuration consisting of an Intel graphics card, 8 GB of RAM, and a 1.9 GHz processor.

4.2. Hyper Parameter Selection and Initial Search

Parameters given in

Table 2 are selected in this work.

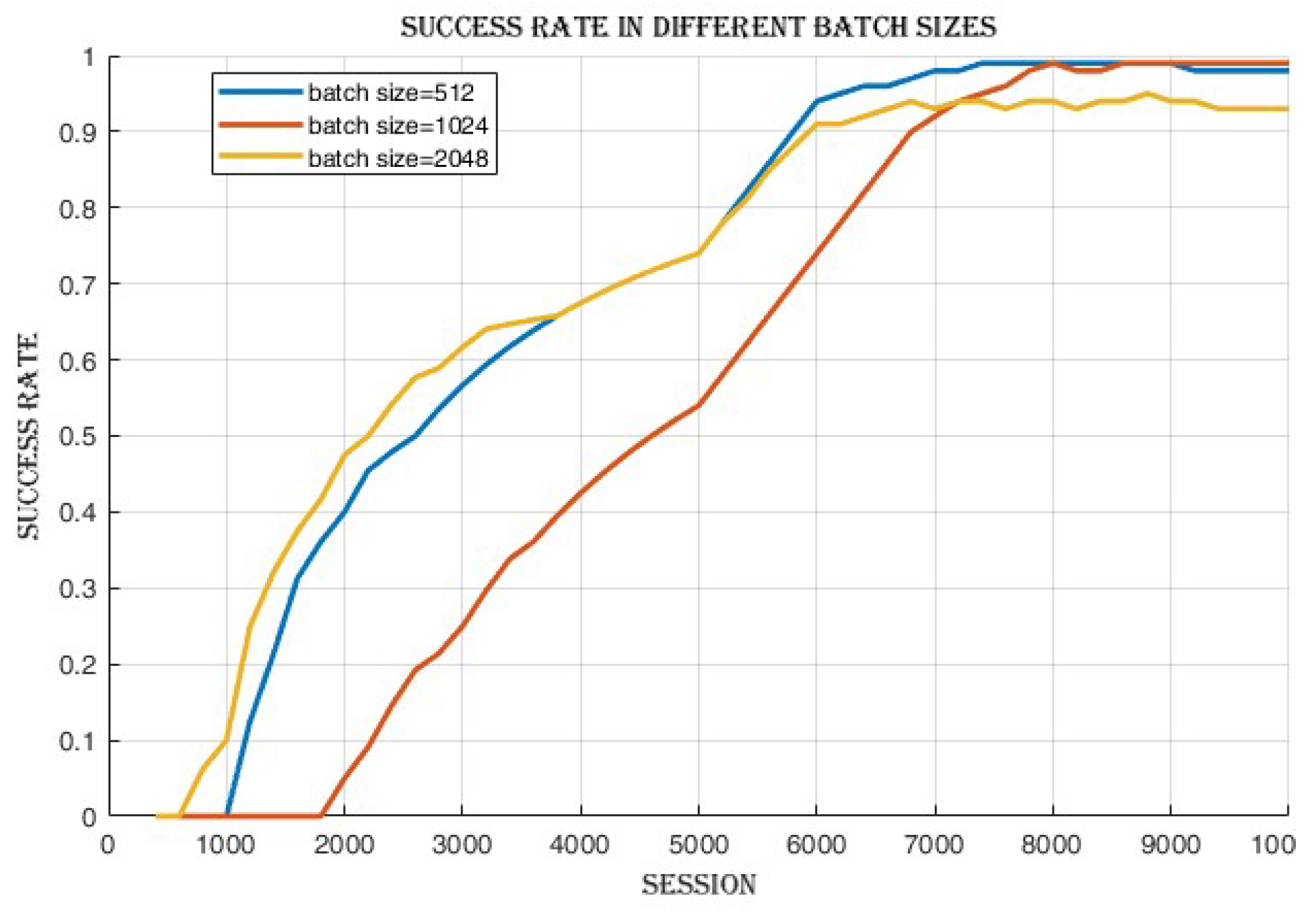

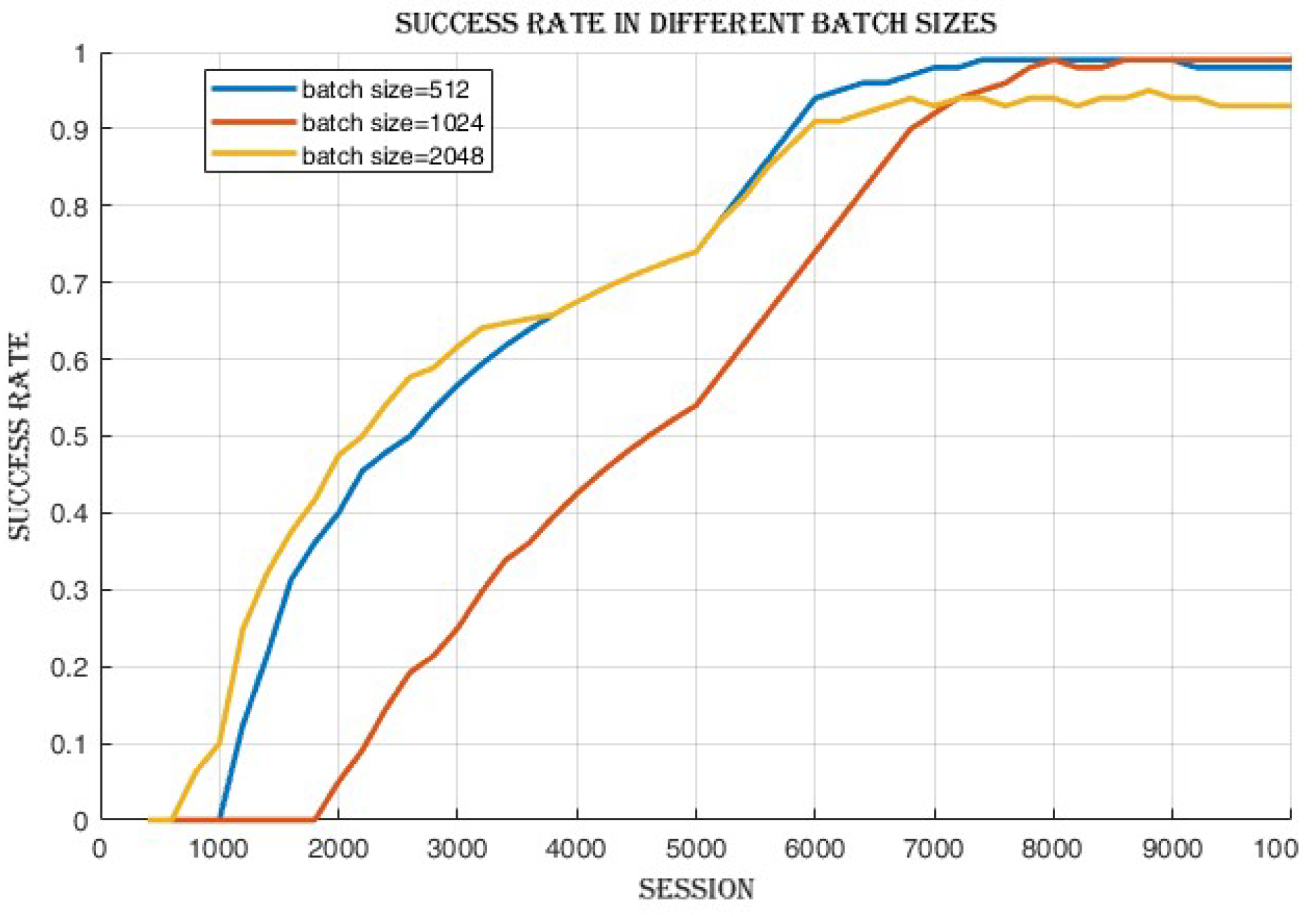

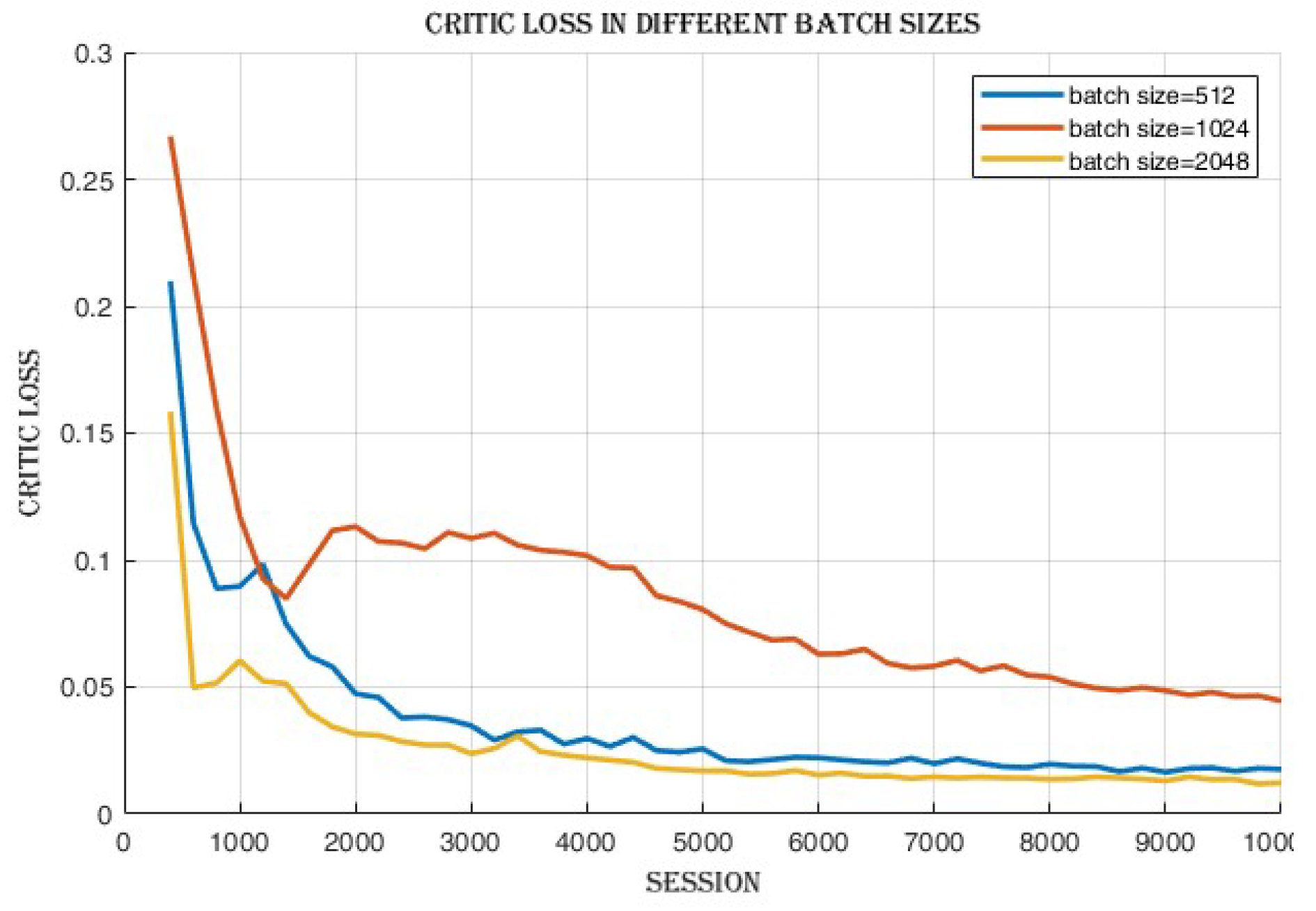

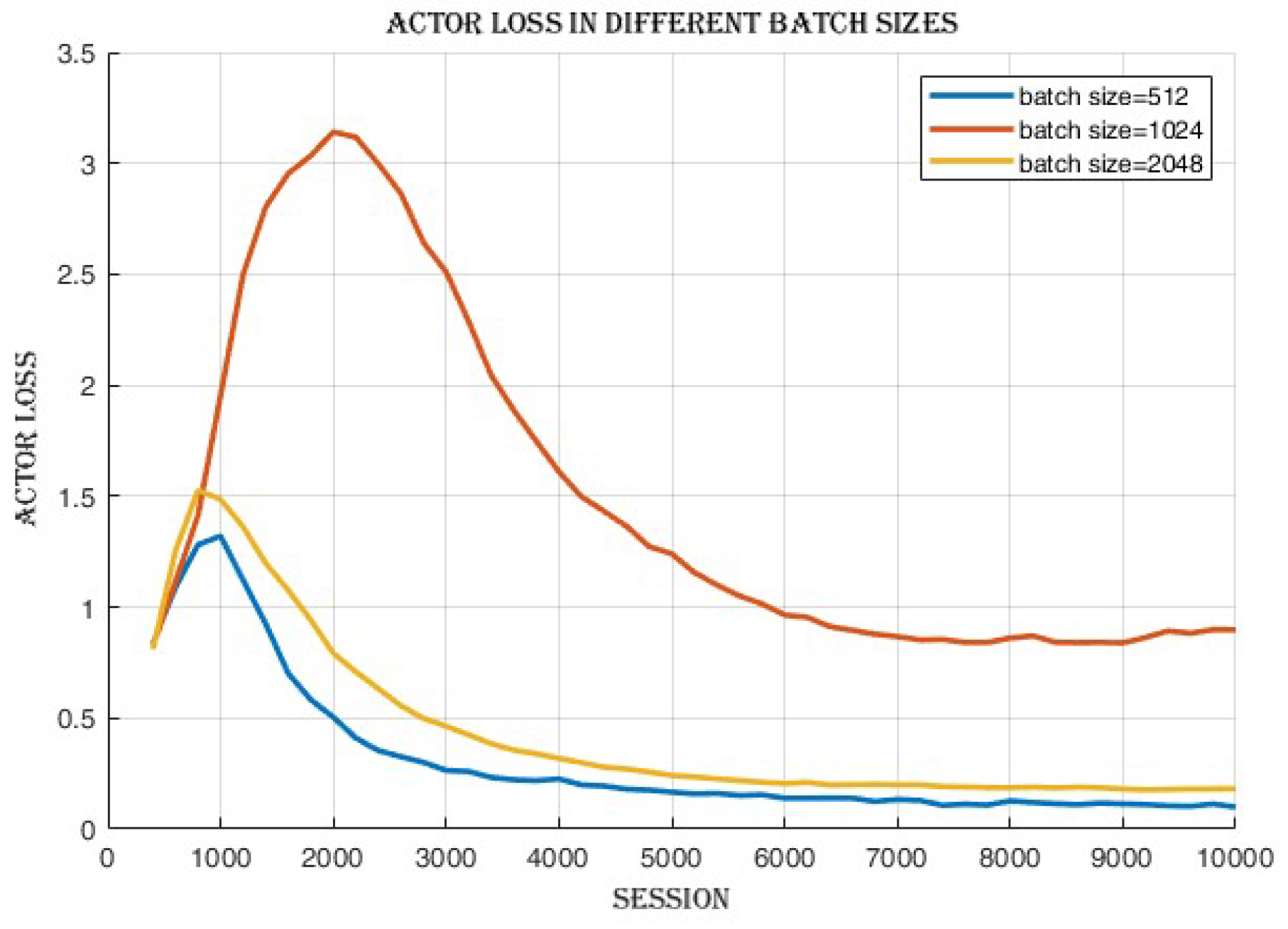

4.2.1. Batch Size Comparison

Upon completing the training process, it was observed that there was a minimal disparity in the success rate,

Figure 2, and cumulative reward,

Figure 3, achieved across the different batch sizes. Also, the decrease in critic loss values,

Figure 4 and actor loss values,

Figure 5 indicates an improvement in the actor and critic networks’ ability to approximate the optimal policy and value functions. Although the success rate and cumulative reward were similar, the enhanced convergence demonstrated by the lower losses in the 2048 batch size suggests a more efficient learning process and a potentially higher quality of learned policies.

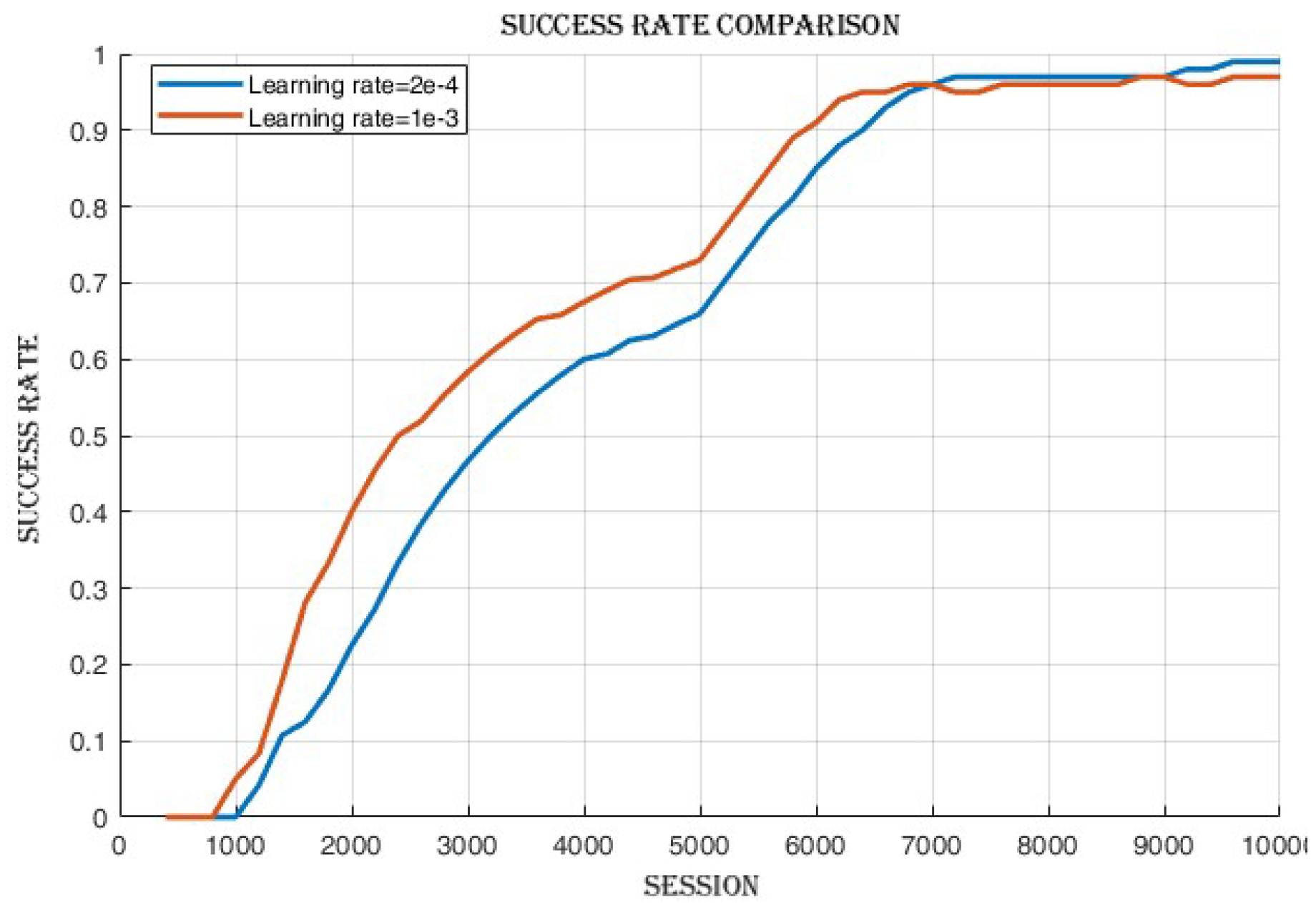

4.2.2. Learning Rate Comparison

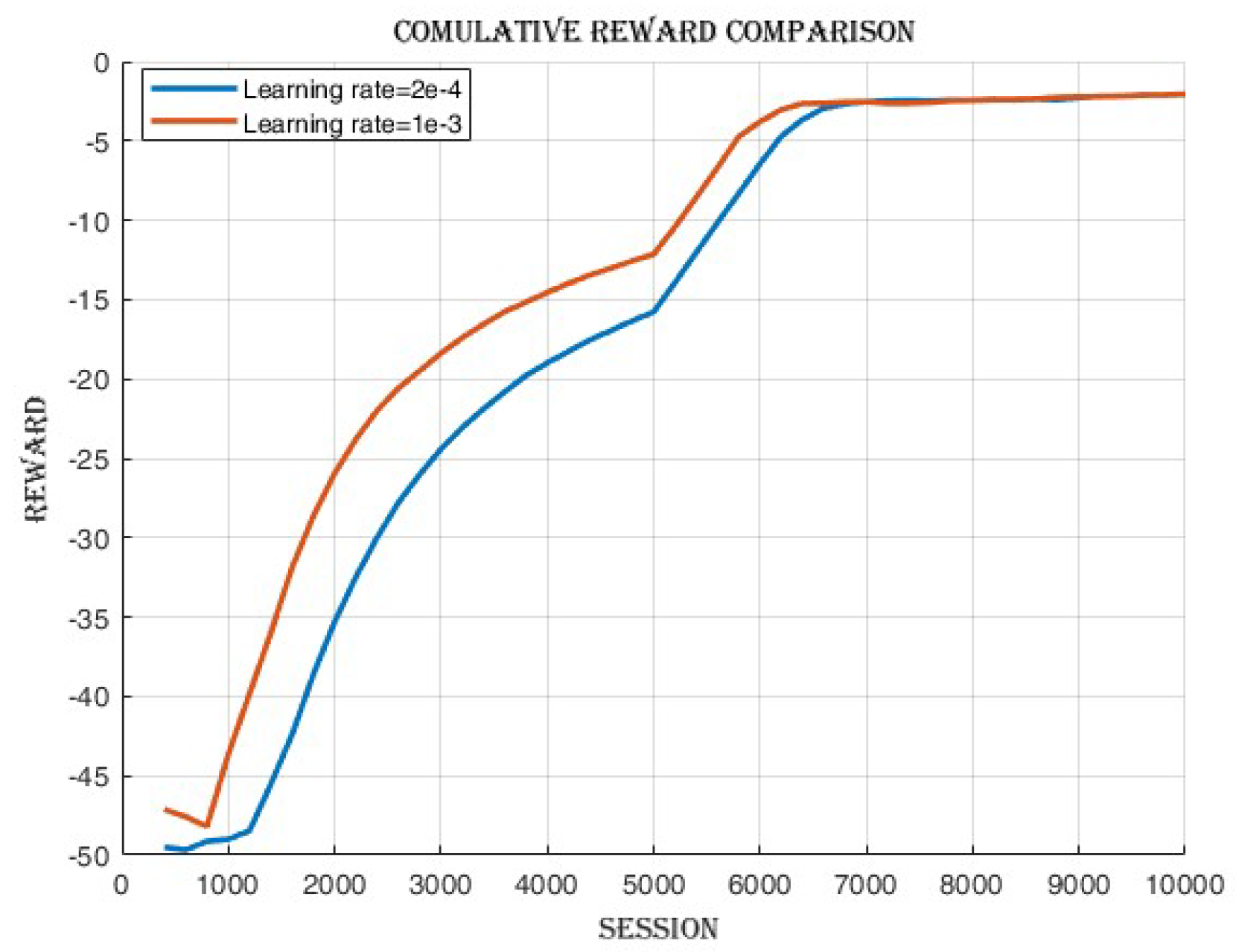

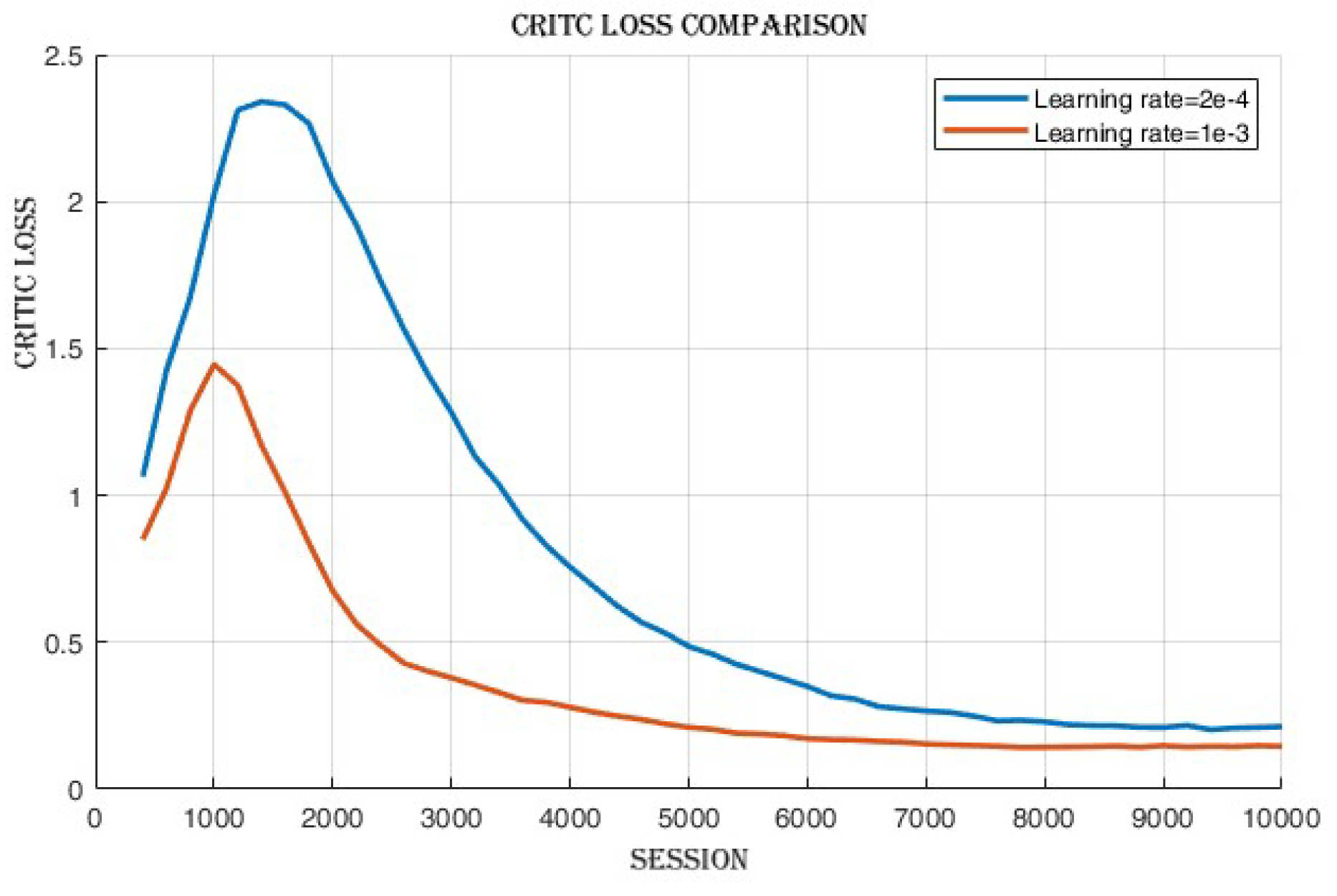

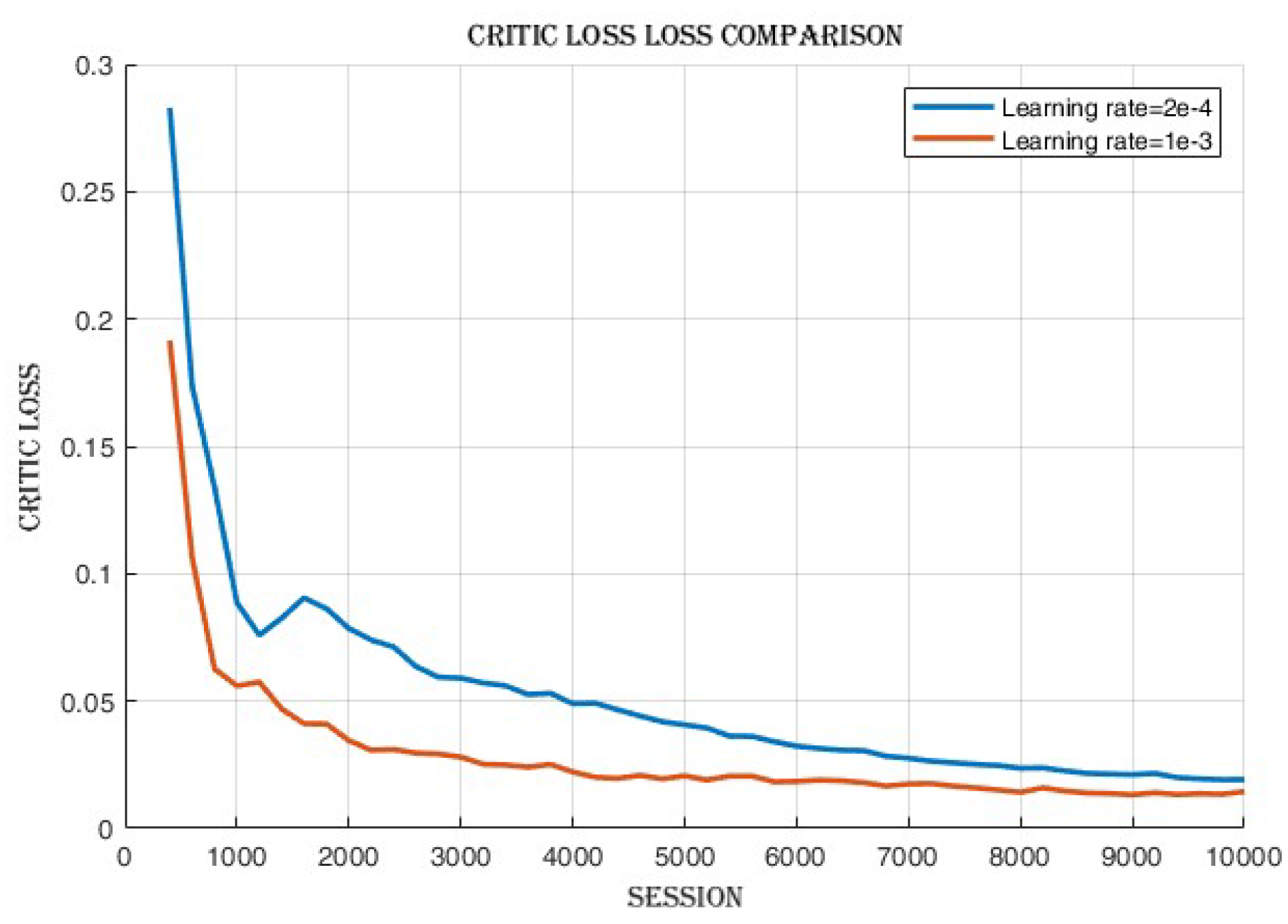

After the training process, observations,

Figure 8 revealed that there was a minimal disparity in the cumulative reward and success rate achieved between the two learning rates as shown in

Figure 7. However, the learning rate of 2e-4 displayed slightly superior performance compared to 1e-3 in terms of success rate. Conversely, when using the learning rate of 1e-3, a notable decrease in actor loss,

Figure 9 and critic loss,

Figure 10 was observed, indicating improved policy and value estimation by the agent. Despite comparable cumulative reward and success rates, the reduced losses at the learning rate of 1e-3 signify enhanced convergence and a potentially more efficient learning process, suggesting the agent may have acquired higher-quality learned policies.

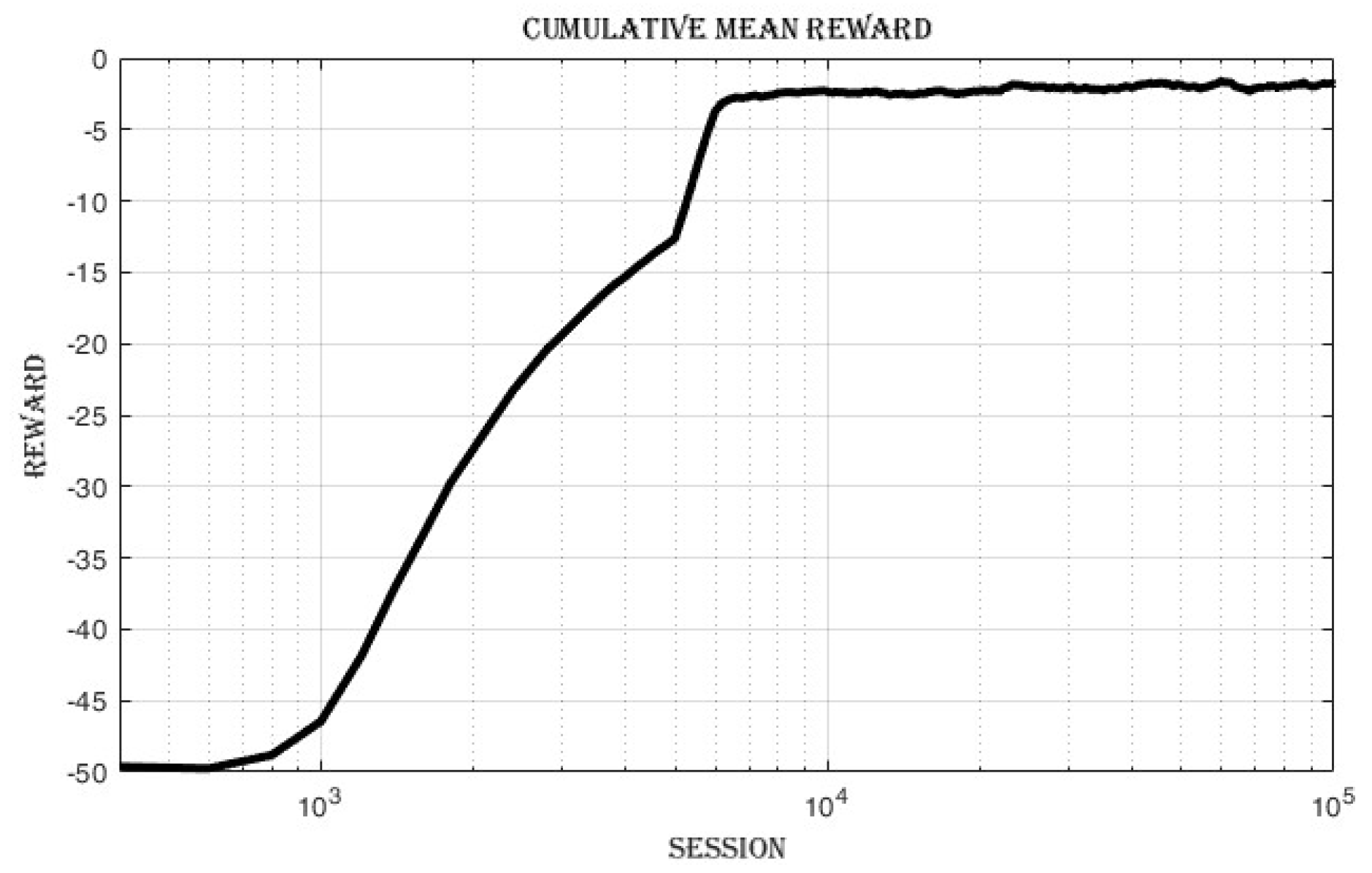

4.3. Selection of Optimal Hyperparameters and Extended Training of DDPG Agent

After comparing the hyperparameters, as depicted in the preceding figures, and conducting a thorough analysis of the associated results, the selection of hyperparameters with promising performance was undertaken. Following this, an extended training phase was initiated, encompassing 100,000 time steps. This extended training phase serves as the fundamental training stage, which will be elaborated upon in the subsequent section.

Table 3.

Parameters and Selected Hyper parameters.

Table 3.

Parameters and Selected Hyper parameters.

| Parameter |

Value |

| Policy |

MultiInputPolicy |

| Replay buffer class |

HerReplayBuffer |

| Verbose |

1 |

| Gamma |

0.95 |

| Tau () |

0.005 |

| Batch size |

2048 |

| Buffer size |

100000 |

| Replay buffer kwargs |

rb kwargs |

| Learning rate |

1e-3 |

| Action noise |

Normal action noise |

| Policy kwargs |

Policy kwargs |

| Tensorboard log |

Log path |

Table 4.

Training Metrics at 200 time step and at time step.

Table 4.

Training Metrics at 200 time step and at time step.

| Category |

Value |

Category |

Value |

| rollout/ |

rollout/ |

| Episode length |

50 |

Episode length |

50 |

| Episode mean reward |

-49.2 |

Episode mean reward |

-1.8 |

| Success rate |

0 |

Success rate |

1 |

| time/ |

time/ |

| Episodes |

4 |

Episodes |

2000 |

| FPS |

18 |

FPS |

5 |

| Time elapsed |

10 |

Time elapsed |

19505 |

| Total timesteps |

200 |

Total time steps |

100000 |

| train/ |

train/ |

| Actor loss |

0.625 |

Actor loss |

0.0846 |

| Critic loss |

0.401 |

Critic loss |

0.00486 |

| Learning rate |

0.001 |

Learning rate |

0.001 |

| Number of updates |

50 |

Number of updates |

99850 |

4.3.1. Improvement in Cumulative Reward and Success Rate

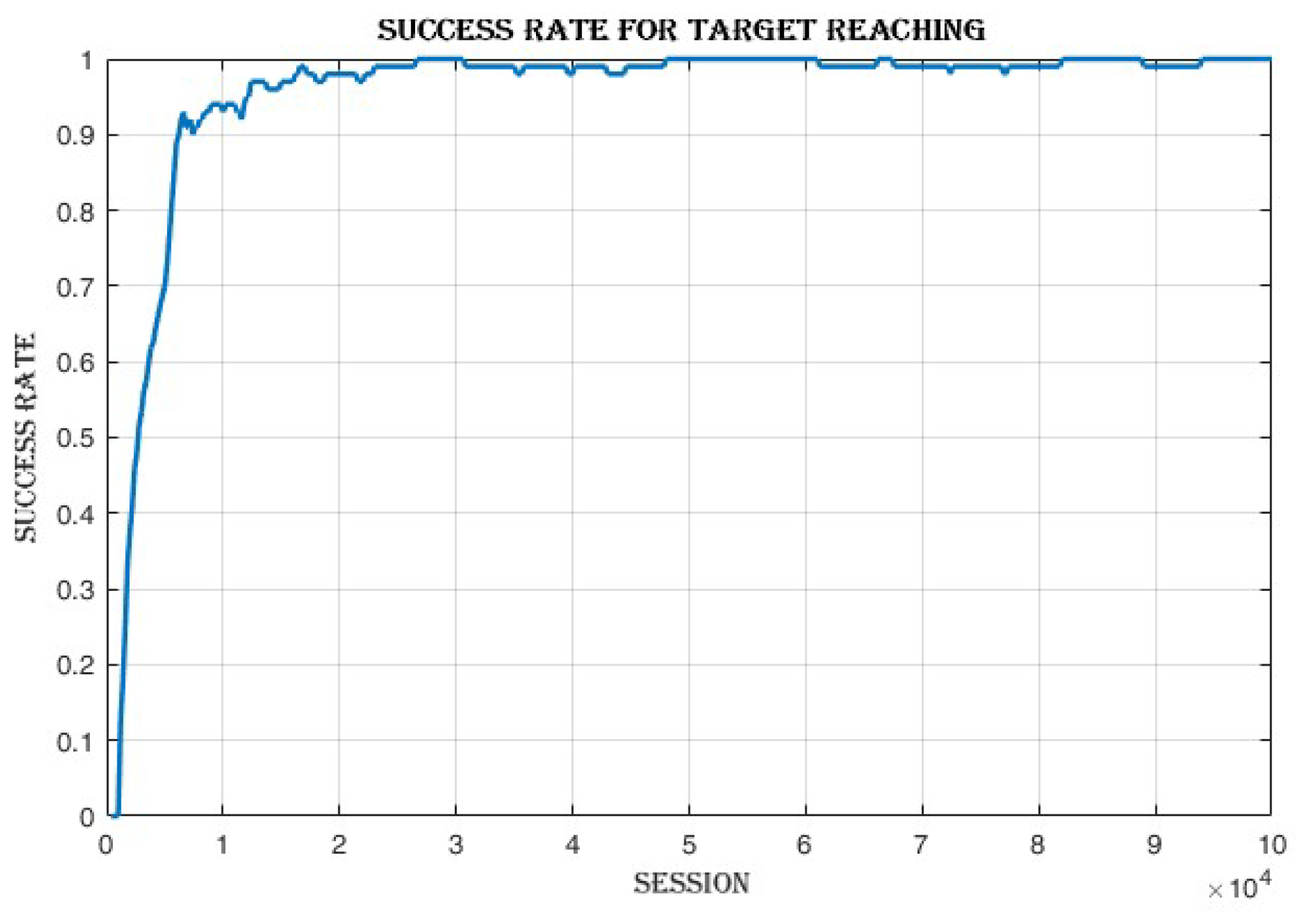

The mean episode reward,

Figure 11 improves from -49.2 in the first loop to -1.8 in the last loop. The success rate,

Figure 12 increases from 0 in the first loop to 1 in the last loop.

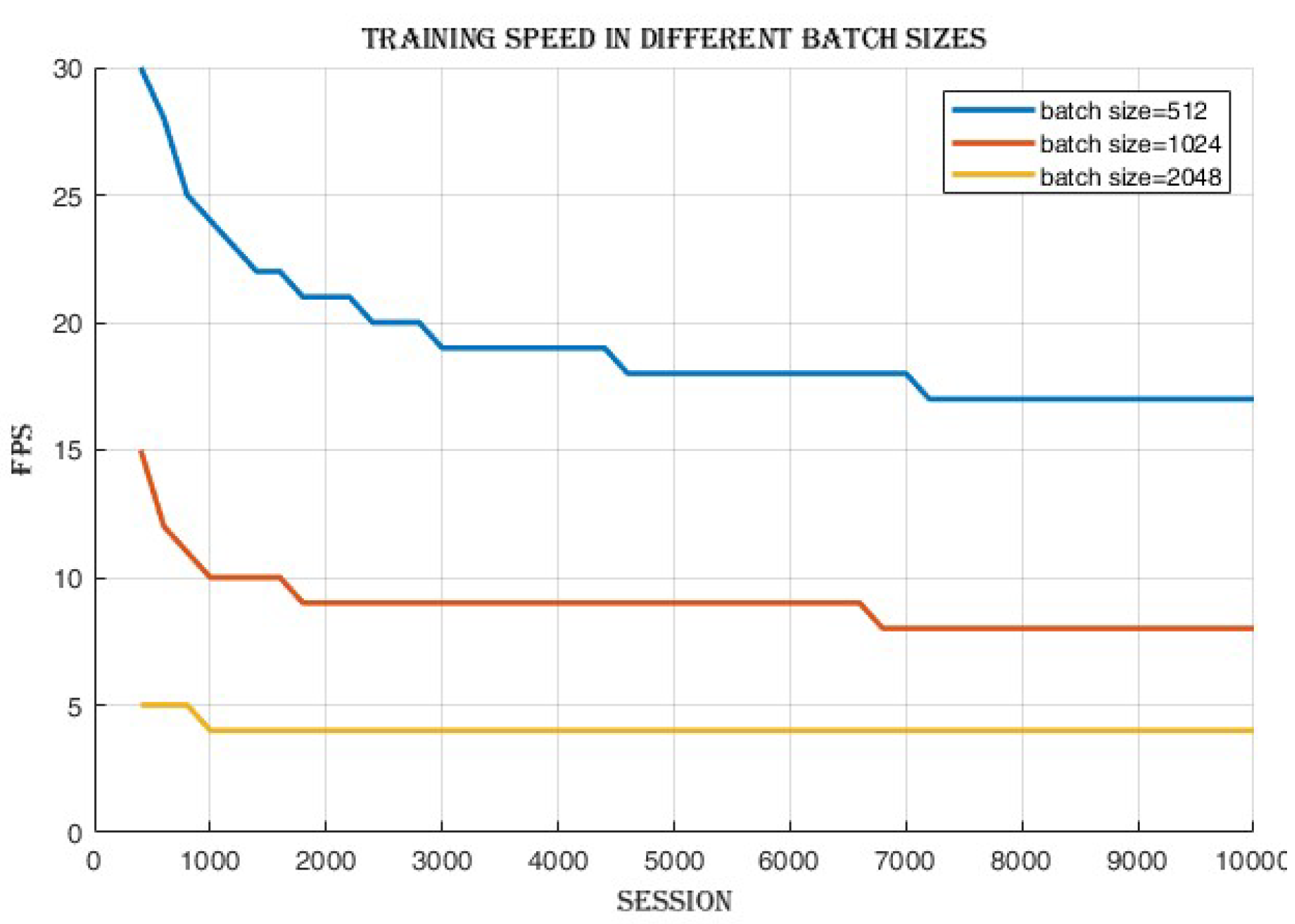

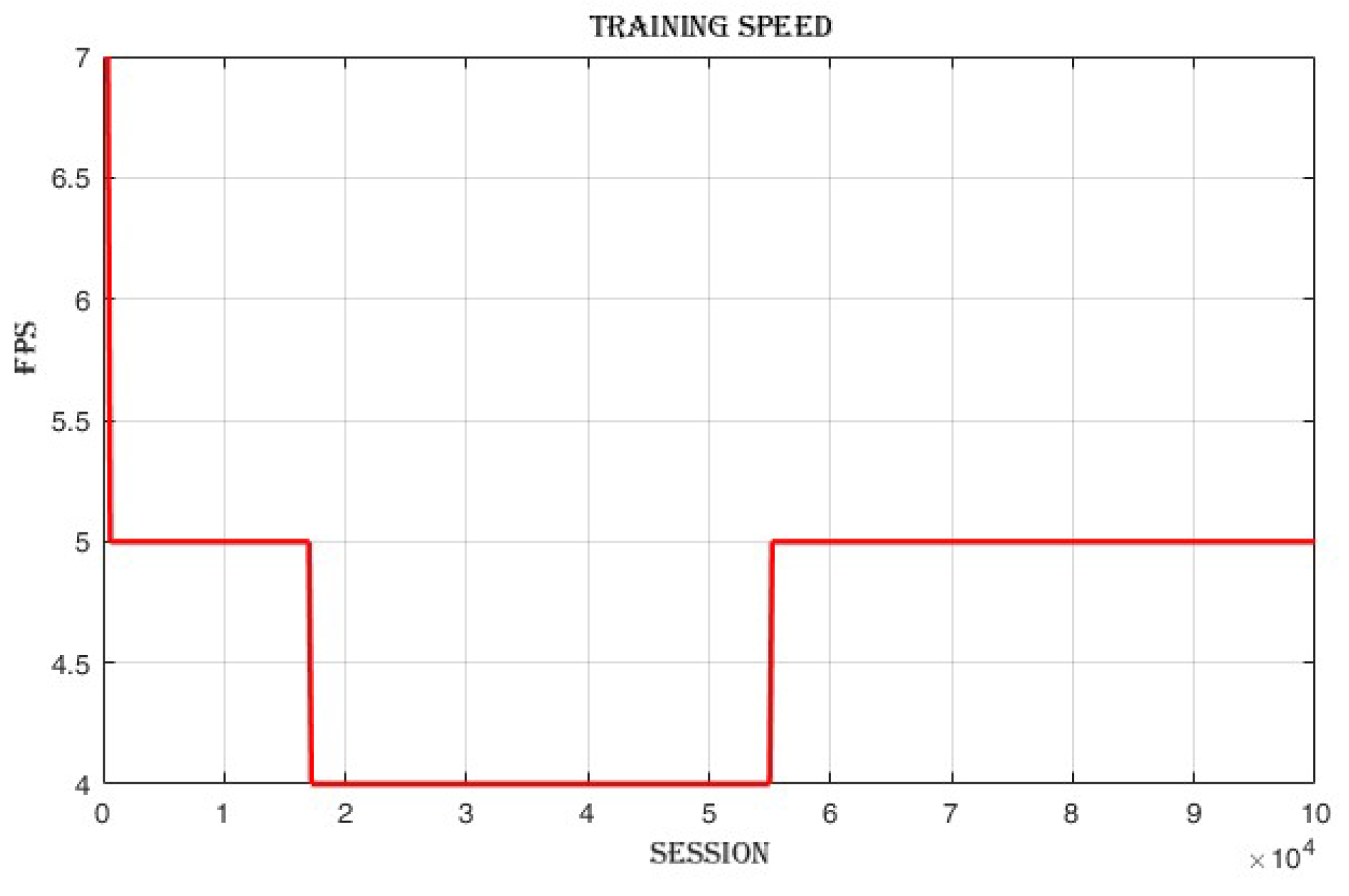

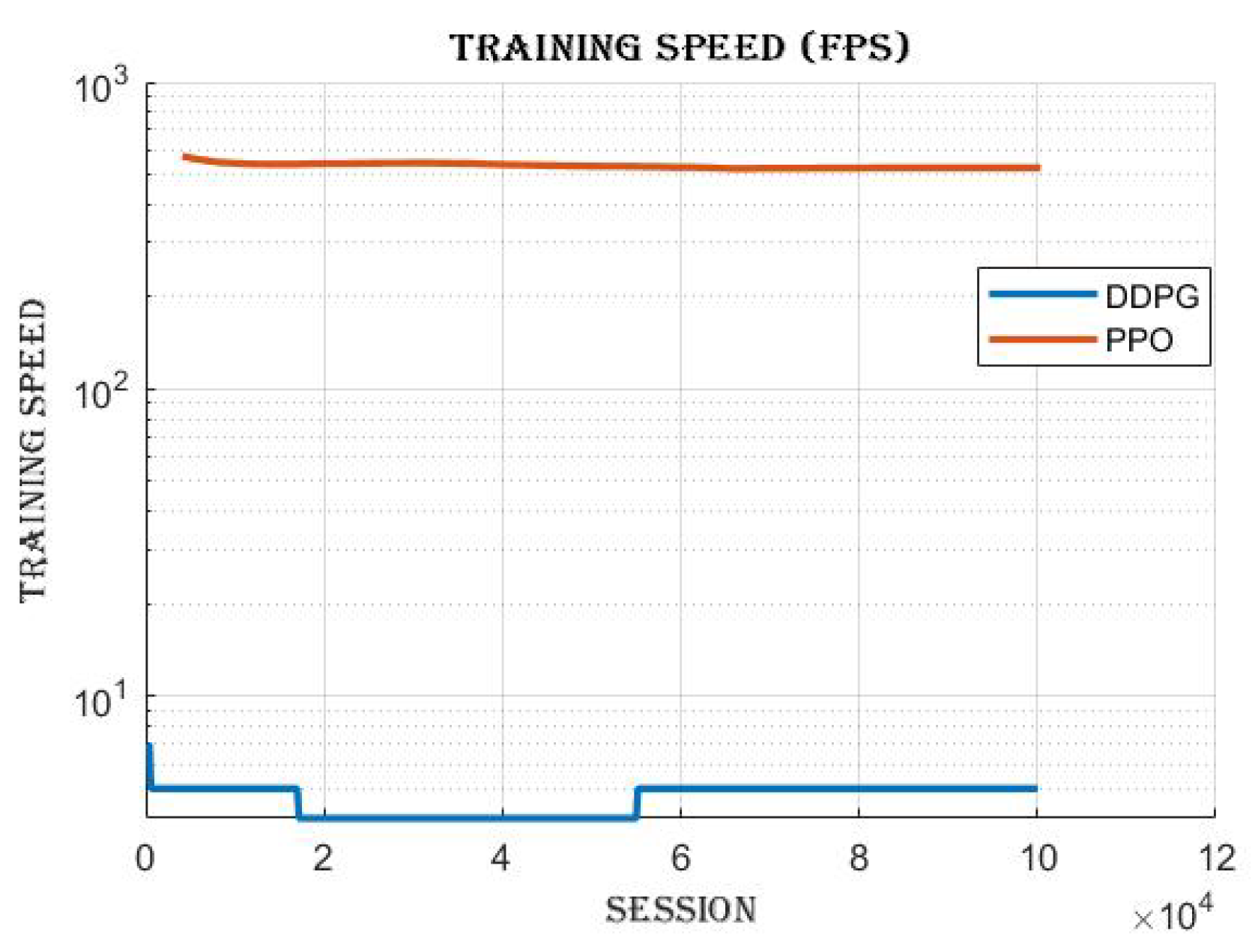

4.3.2. Frames per Second (FPS)

The training speed,

Figure 13 decreases from 18 frames per second (FPS) in the first loop to 5 FPS in the last loop.

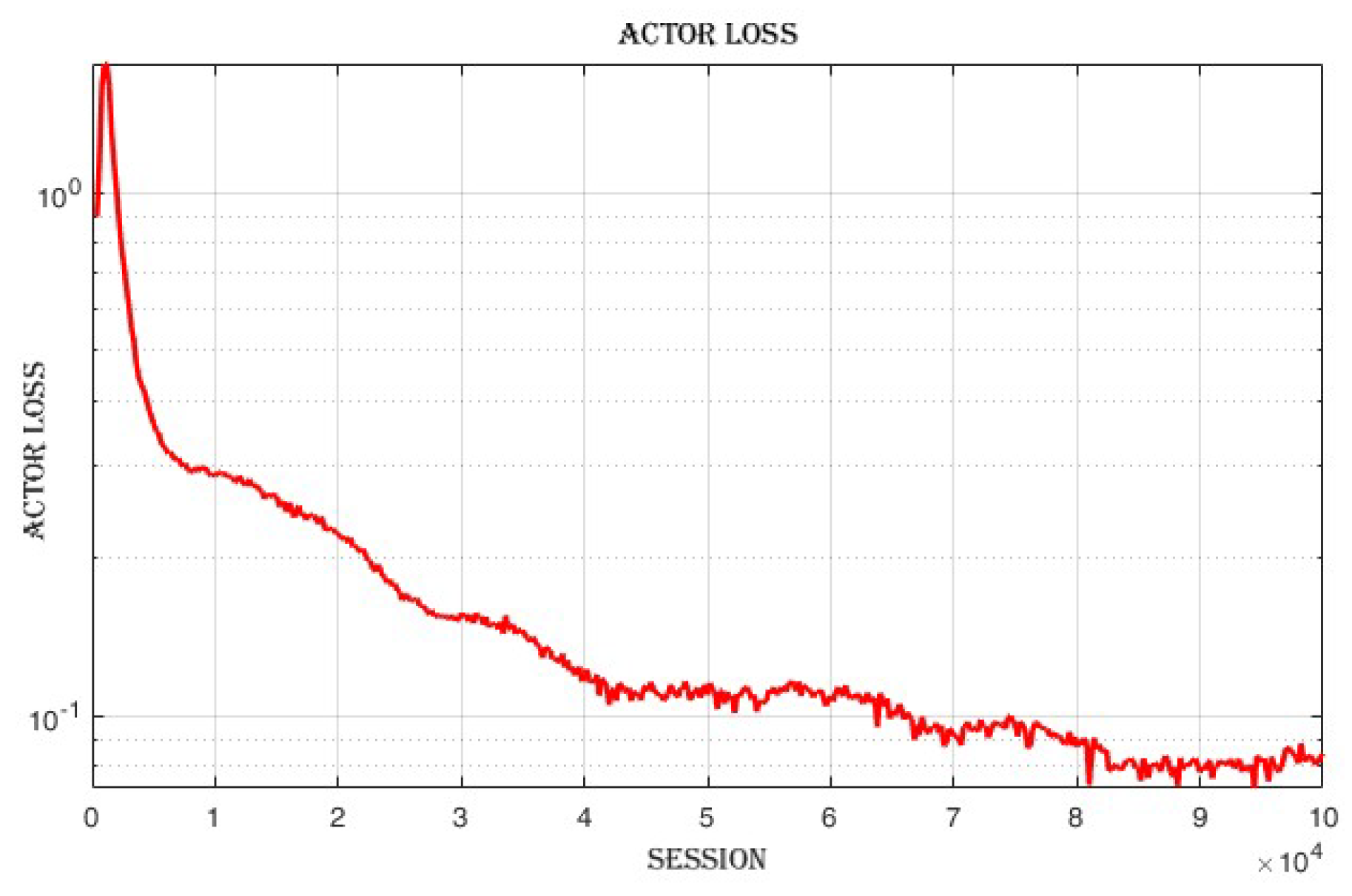

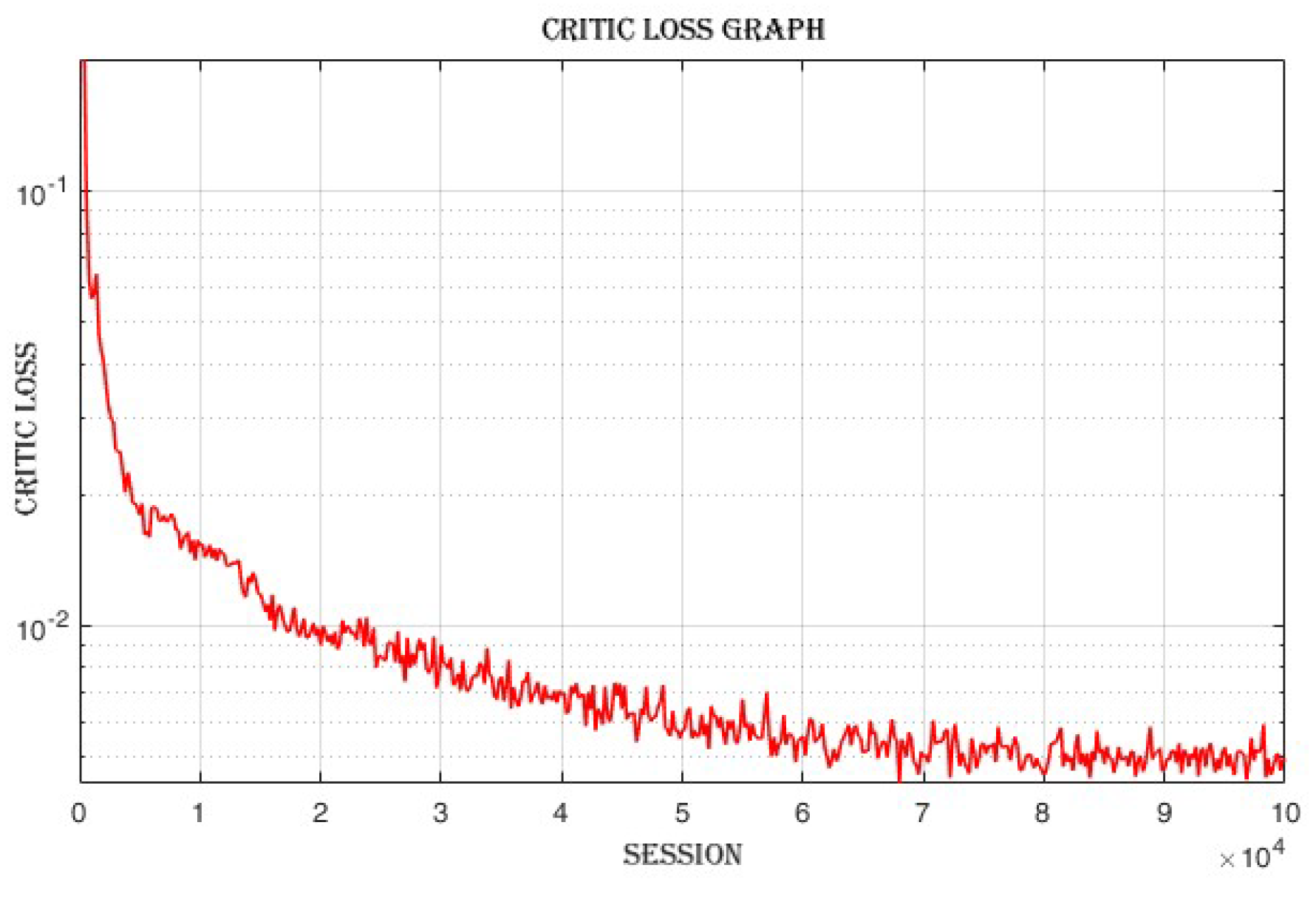

4.3.3. Improvement in Actor and Critic Losses

The actor loss,

Figure 14 decreases from 0.625 in the first loop to 0.0846 in the last loop. The critic loss,

Figure 15 decreases from 0.401 in the first loop to 0.00486 in the last loop.

4.4. Comparing DDPG and PPO: Off-Policy vs. On-Policy Reinforcement Learning Algorithms

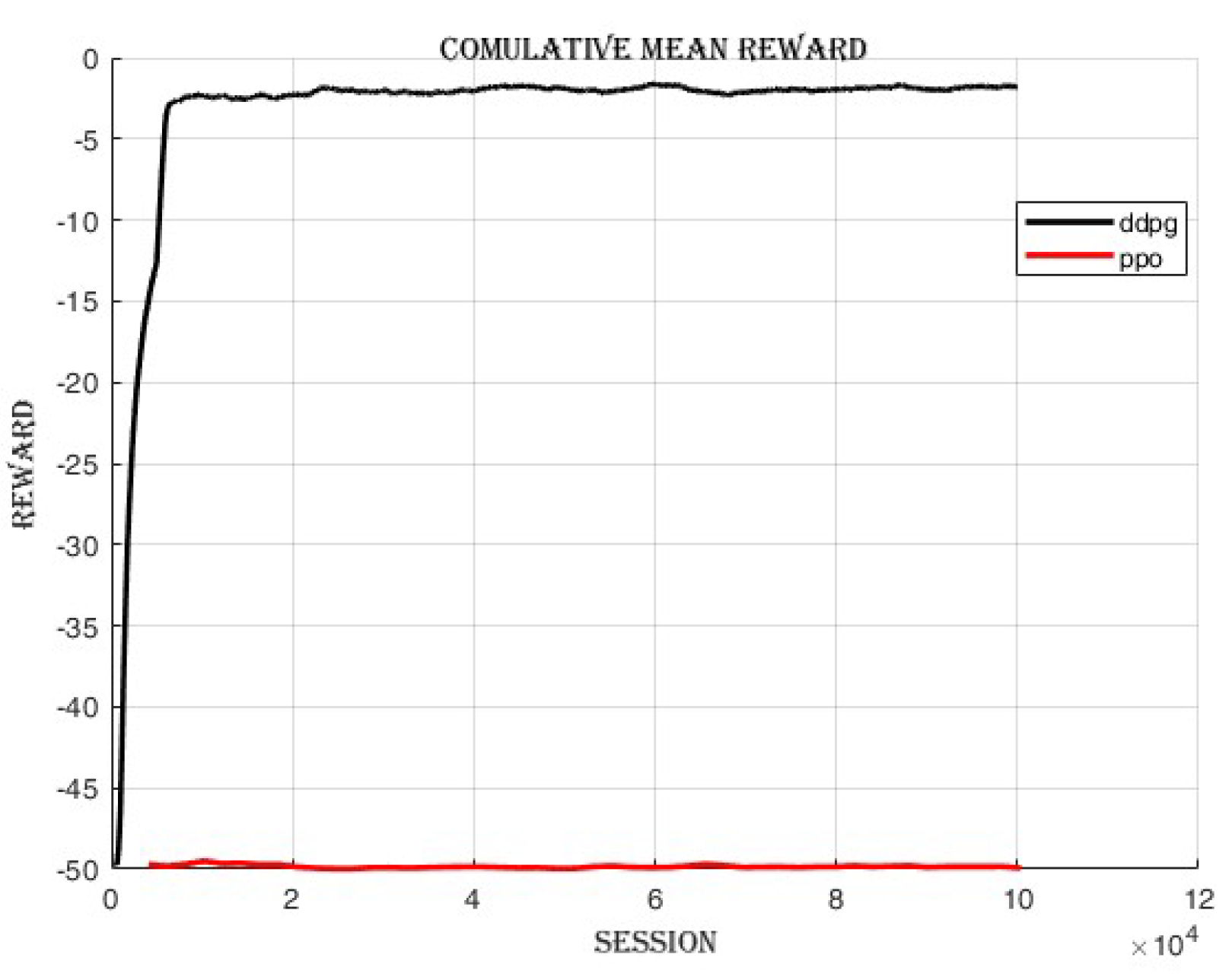

Proximal policy optimization (PPO), an on-policy reinforcement learning algorithm, was trained to compare its performance with Deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG), an off-policy algorithm, as shown in

Figure 16 and

Figure 17. The cumulative reward achieved by DDPG was

, whereas the cumulative reward obtained by PPO was

as shown in

Figure 16. The results of this comparison indicate that, in this particular scenario, DDPG exhibited superior performance over PPO in terms of cumulative reward.

5. Conclusion

In this study, the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) algorithm is applied to train a robotic arm manipulator, specifically the Franka Panda robotic arm, for a target-reaching task. The objective of this task is to enable the robotic arm to accurately reach a designated target position. The DDPG algorithm is chosen because of its effectiveness in continuous control tasks and its ability to learn policies with high-dimensional action spaces. By leveraging a combination of deep neural networks and actor-critic architecture, DDPG approximates the optimal policy for the robotic arm. When comparing the performance of PPO and DDPG after training for time steps:

PPO achieved a mean episode reward of indicating that the agent struggled to achieve positive rewards on average. Despite training at a relatively fast speed of , the results suggest that PPO faced challenges in finding successful strategies for the given task.

On the other hand, DDPG demonstrated superior performance with a mean episode reward of . It achieved a success rate of 1, indicating consistent success in reaching desired outcomes. Despite a slower training speed of . DDPG showcased its capability to effectively learn and improve its policy over time. Based on these results, DDPG outperformed PPO in terms of cumulative reward and success rate in the given scenario.

Author Contributions

The authors contributions in this manuscript are stated as follows: Conceptualization, L.H. and Y.A.; methodology, L.H.; software, L.H.; validation, A.T., Y.S.J. and S.J.; formal analysis, L.H.; investigation, A.T., Y.S.J.; resources, L.H.; data curation, L.H.; writing—original draft preparation, L.H.; writing—review and editing, Y.A., and A.T., and S.J.; visualization, A.T. and L.H.; supervision, Y.A. and S.J.; project administration, S.J.; funding acquisition, S.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the project for Smart Manufacturing Innovation R&D funded Korean Ministry of SMEs and Startups in 2024(Project No.RS-2024-00434311).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable’

Data Availability Statement

All the required data in this work are available with the authors and they can be provided upon request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the project for Smart Manufacturing Innovation R&D funded Korean Ministry of SMEs and Startups in 2024(Project No.RS-2024-00434311).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Mohsen, S.; Behrooz, A.; Roza, D. Artificial intelligence, machine learning and deep learning in advanced robotics, a review. Cognitive Robotics 2023, 3, 54–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan, M.; Stone, P. Color Learning on a Mobile Robot: Towards Full Autonomy under Changing Illumination. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI); 2007; pp. 2212–2217. [Google Scholar]

- Xinle, Y.; Minghe, Sh.; Lingling, Sh. Adaptive and intelligent control of a dual-arm space robot for target manipulation during the post-capture phase. Aerospace Science and Technology 2023, 142, 108688. [Google Scholar]

- Abayasiri, R. A. M.; Jayasekara, A. G. B. P.; Gopura, R. A. R. C.; Kazuo, K. Intelligent Object Manipulation for a Wheelchair-Mounted Robotic Arm. Journal of Robotics, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, M. A.; Hui, L.; Norbert, St.; Kerstin, Th. Intelligent arm manipulation system in life science labs using H20 mobile robot and Kinect sensor. 2016 IEEE 8th International Conference on Intelligent Systems (IS), Sofia, Bulgaria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiyuki Ohmura and Yasuo Kuniyoshi. Humanoid robot which can lift a 30kg box by whole body contact and tactile feedback. 007 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 1136–1141. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Ming, J.; Dewan, F.; Hossain, M.A. Intelligent facial emotion recognition and semantic-based topic detection for a humanoid robot. Expert Systems with Applications 2013, 40, 5160–5168. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J. G. Muros, F. J., Maestre, J. M., and Camacho, E. F. Multi-robot task allocation clustering based on game theory. Robotics and Autonomous Systems. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2023, 161, 104314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M. N. T. Ba, D. X. A neural flexible PID controller for task-space control of robotic manipulators. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2023, 9, 975850. [Google Scholar]

- Laurenzi, A. Antonucci, D., Tsagarakis, N. G., and Muratore, L. The XBot2 real-time middleware for robotics. Robotics and Autonomous Systems. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2023, 163, 104379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Jiang, M., Farid, D., and Hossain, M. A. Intelligent Facial Emotion Recognition and Semantic-Based Topic Detection for a Humanoid Robot. Expert Systems with Applications 2013, 40, 5160–5168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floreano, D. Wood, R. J. Science, Technology, and the Future of Small Autonomous Drones. Nature 2015, 521, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T. D. , Kockelman, K. M., and Hanna, J. P. Operations of a Shared, Autonomous, Electric Vehicle Fleet: Implications of Vehicle & Charging Infrastructure Decisions. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. Jia, X., Riedel, A., and Zhang, M. A Bio-Inspired Swimming Robot. 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2014; pp. 2564–2564. [Google Scholar]

- Ohmura, Y. and Kuniyoshi, Y. Humanoid Robot Which Can Lift a 30kg Box by Whole Body Contact and Tactile Feedback. 2007 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems; 2007; pp. 1136–1141. [Google Scholar]

- Kappassov, Z. Corrales, J.-A., and Perdereau, V. Tactile Sensing in Dexterous Robot Hands. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2015, 74, 195–-220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisumi, H. Miossec, S., Chardonnet, J.-R., and Yokoi, K Dynamic Lifting by Whole Body Motion of Humanoid Robots. 2008 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems; 2008; pp. 668–675. [Google Scholar]

- Aryslan, M. Yevgeniy, L., Troy, H., Richard, P. A deep reinforcement-learning approach for inverse kinematics solution of a high degree of freedom robotic manipulator. Robotics 2022, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhat, O. Enver T., Erkan Z. Adaptive Cartesian space control of robotic manipulators: A concurrent learning based approach. Journal of the Franklin Institute 2024, 361, 106701. [Google Scholar]

- Kaelbling, L. P. Littman, M. L., and Moore, A. Reinforcement Learning: A Survey. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 1996, 4, 237–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadi, Al. , Katarina Gr. Reinforcement learning algorithms: An overview and classification. 2021 IEEE Canadian Conference on Elec-trical and Computer Engineering (CCECE); 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Thrun, S.; and Littman, M. L. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction. AI Magazine 2000, 21, 103-. [Google Scholar]

- Smruti Amarjyoti. Deep reinforcement learning for robotic manipulation-the state of the art. arXiv:1701.08878, 2017.

- Jens, K., Bagnell. Reinforcement learning in robotics: A survey. The International Journal of Robotics Research 2013, 32, 1238–1274. [Google Scholar]

- Tianci, G. Optimizing robotic arm control using deep Q-learning and artificial neural networks through demonstration-based methodologies: A case study of dynamic and static conditions. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2024, 104771. [Google Scholar]

- Andrea, Fr., Elisa. Robotic Arm Control and Task Training through Deep Reinforcement Learning. 2020, arXiv:2005.02632v1. [Google Scholar]

- Jonaid, Sh., Michael. Optimizing Deep Reinforcement Learning for Adaptive Robotic Arm Control. 2024, arXiv:2407.02503v1. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, P. , Jakub, K. Computation 2024, 12(6), 116. [Google Scholar]

- Wanqing, X., Yuqian. Deep reinforcement learning based proactive dynamic obstacle avoidance for safe human-robot collaboration. Manufacturing Letters 2024, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Franka Emika Documentation. Control Parameters Documentation, 2024. Available at: CrossRef.

- Weng, L. Policy Gradient Algorithms. Lil’Log, 2018. 2024. Available online: https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2018-04-08-policy-gradient.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).