Submitted:

23 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Titanium carbide (TiC) and tungsten carbide (WC) are essential engineering materials known for their exceptional hardness, wear resistance, and thermal stability. This study investigates the formation, phase stability, mechanical properties, and electronic structure of (Ti,W)C solid solutions. The research employs computational methods, including Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Cluster Expansion (CE), to explore compositional variations and their effects. Results reveal that Ti0.5W0.5C demonstrates superior thermodynamic stability, while intermediate compositions such as Ti0.67W0.33C achieve peak hardness (~33 GPa) due to the synergistic effects of covalent Ti-C and metallic W-C bonding. The electronic structure analysis highlights hybridized bonding characteristics that optimize mechanical resilience and thermal stability. Elastic and vibrational properties show a notable influence of tungsten incorporation, enhancing bulk modulus and enabling tailored properties. These findings provide critical insights for the development of high-performance materials in applications such as machining, wear-resistant coatings, and structural components.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Computational Details

3. Results and Discussion

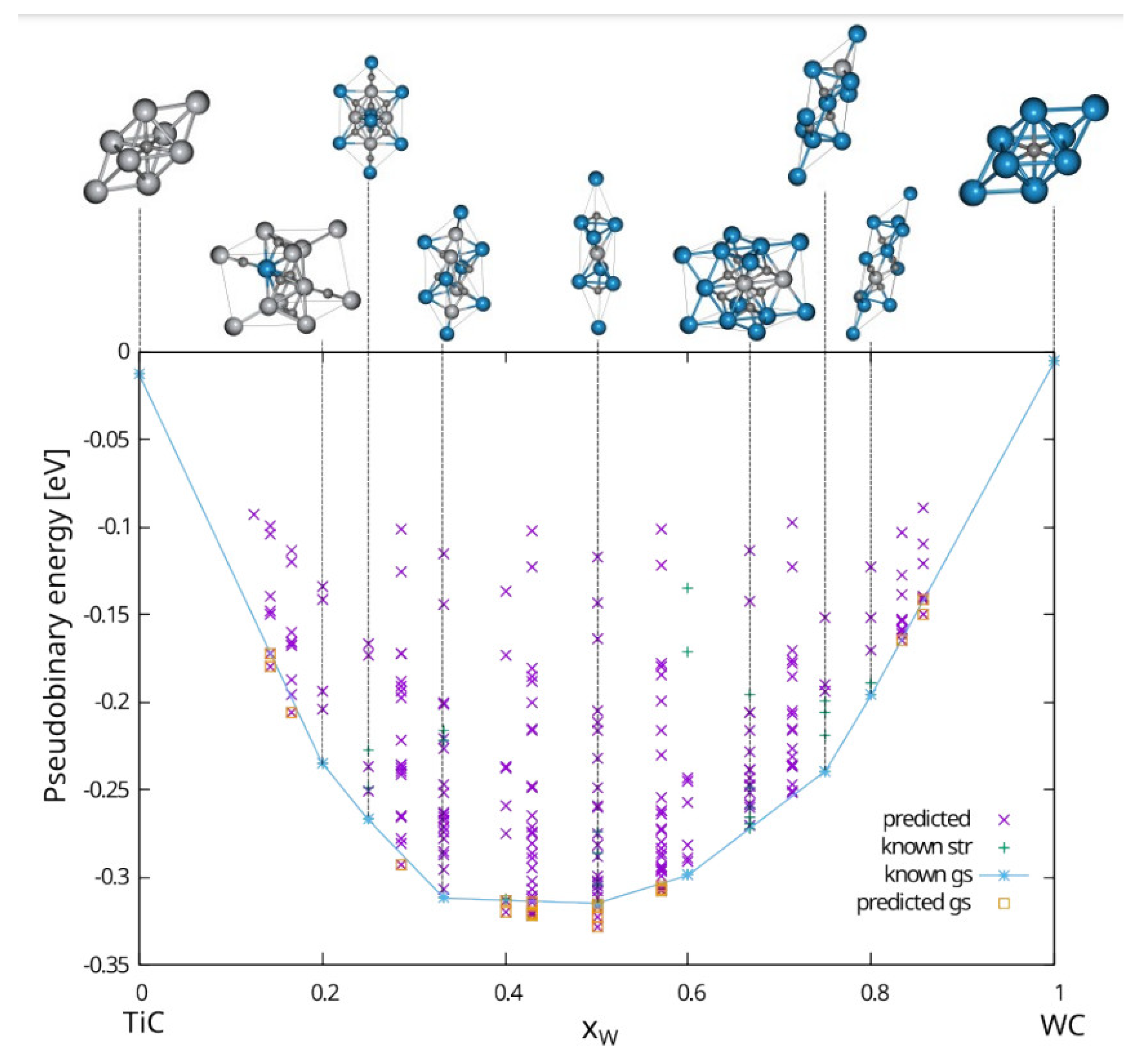

3.1. The Cluster Expansion Analysis

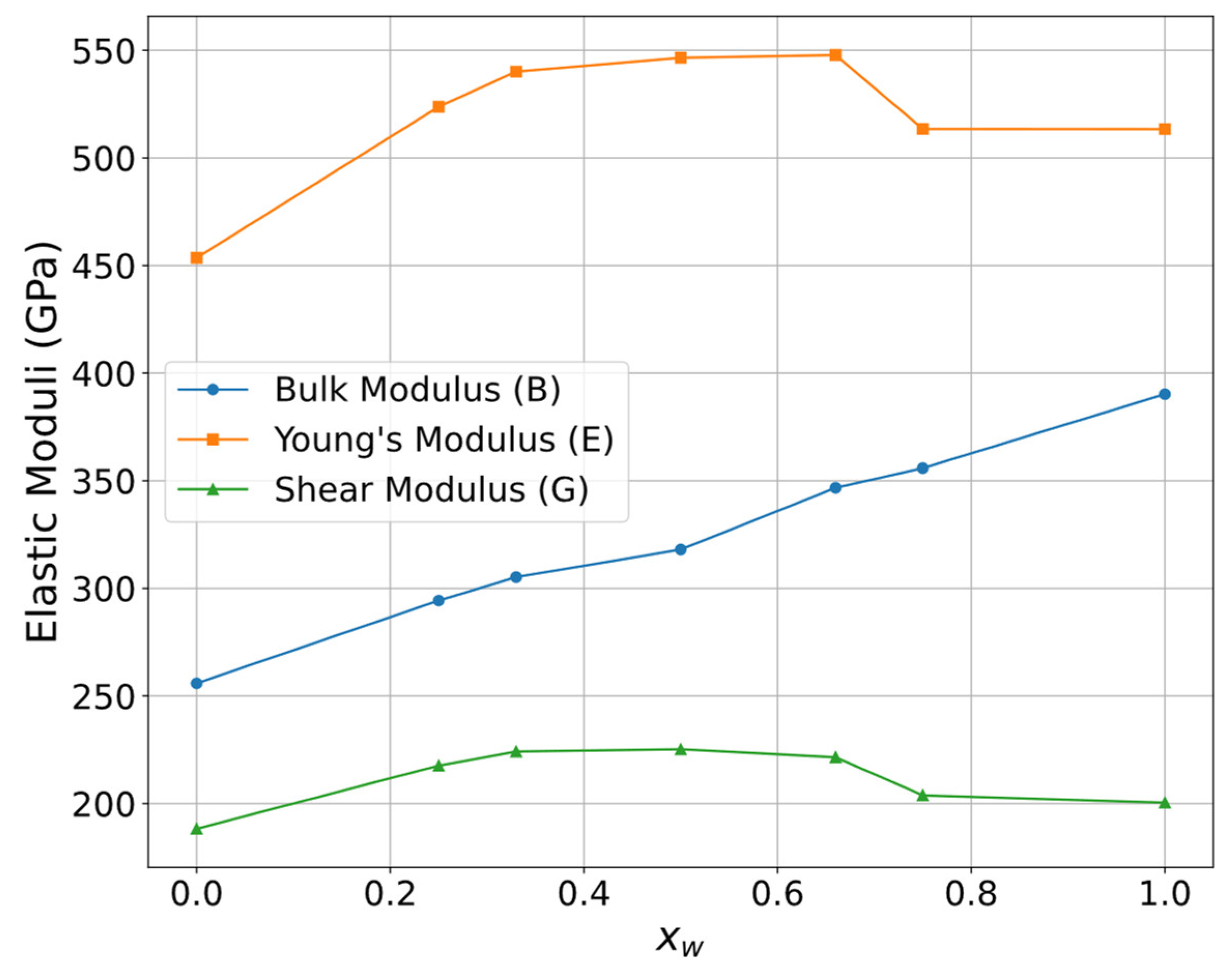

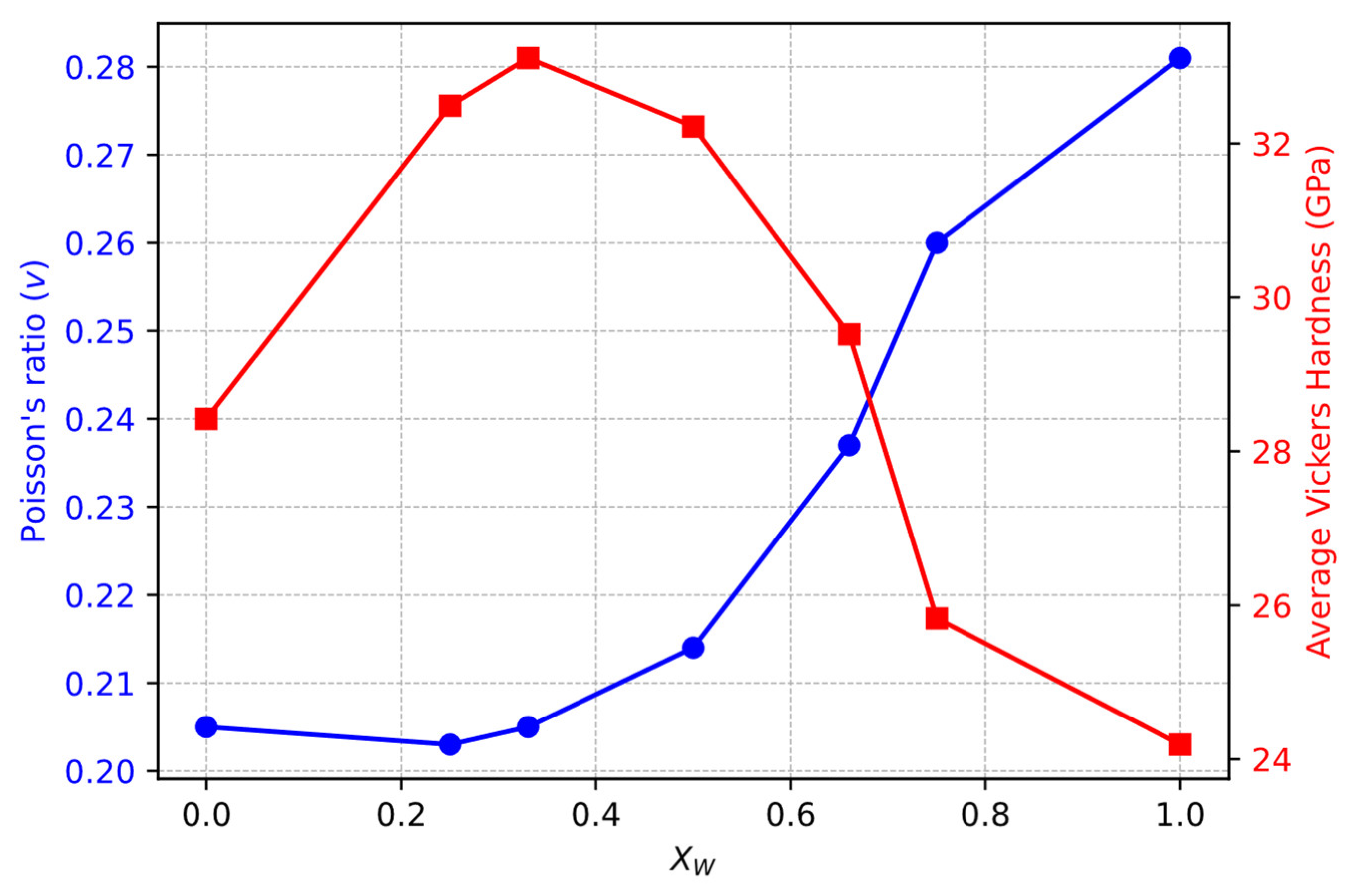

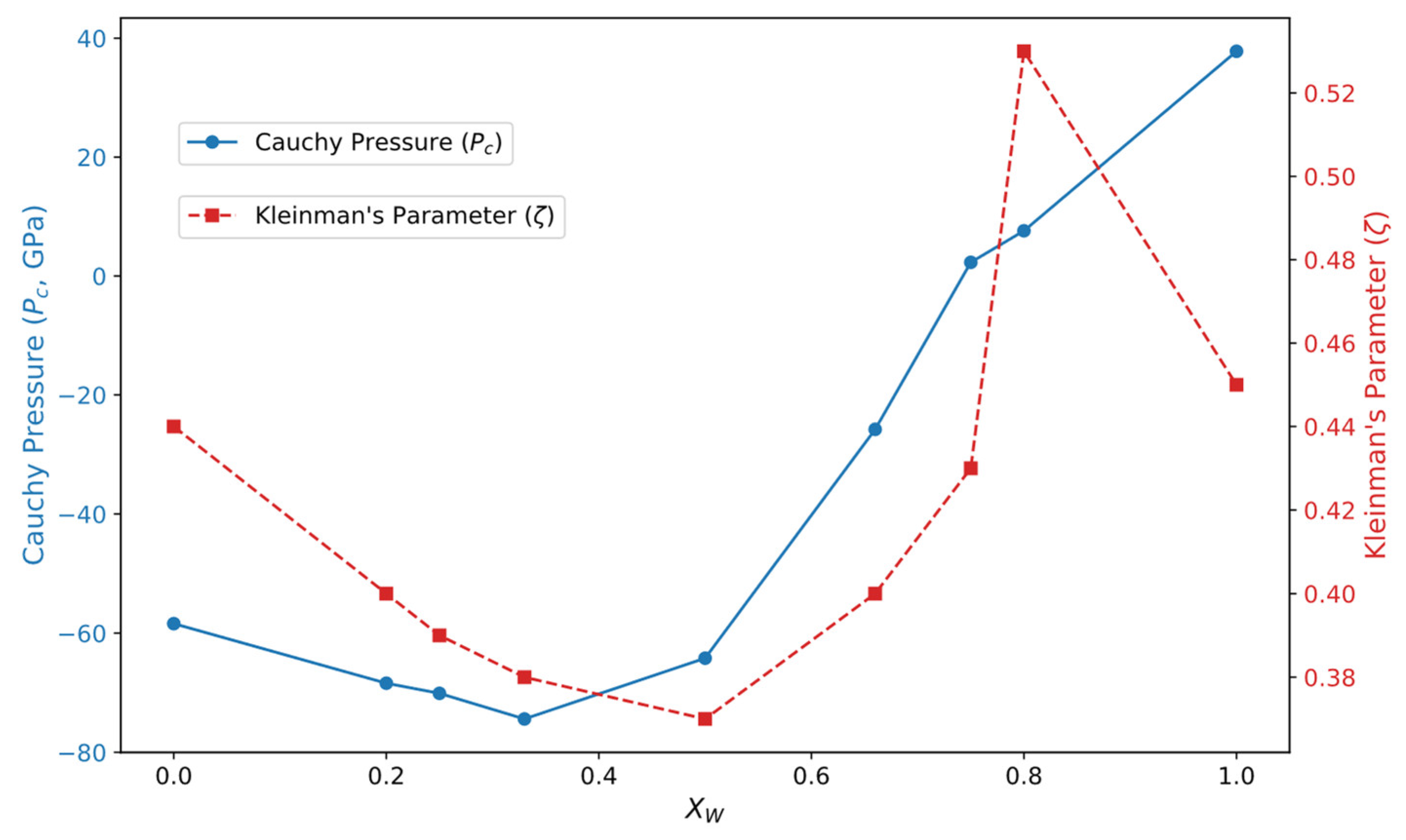

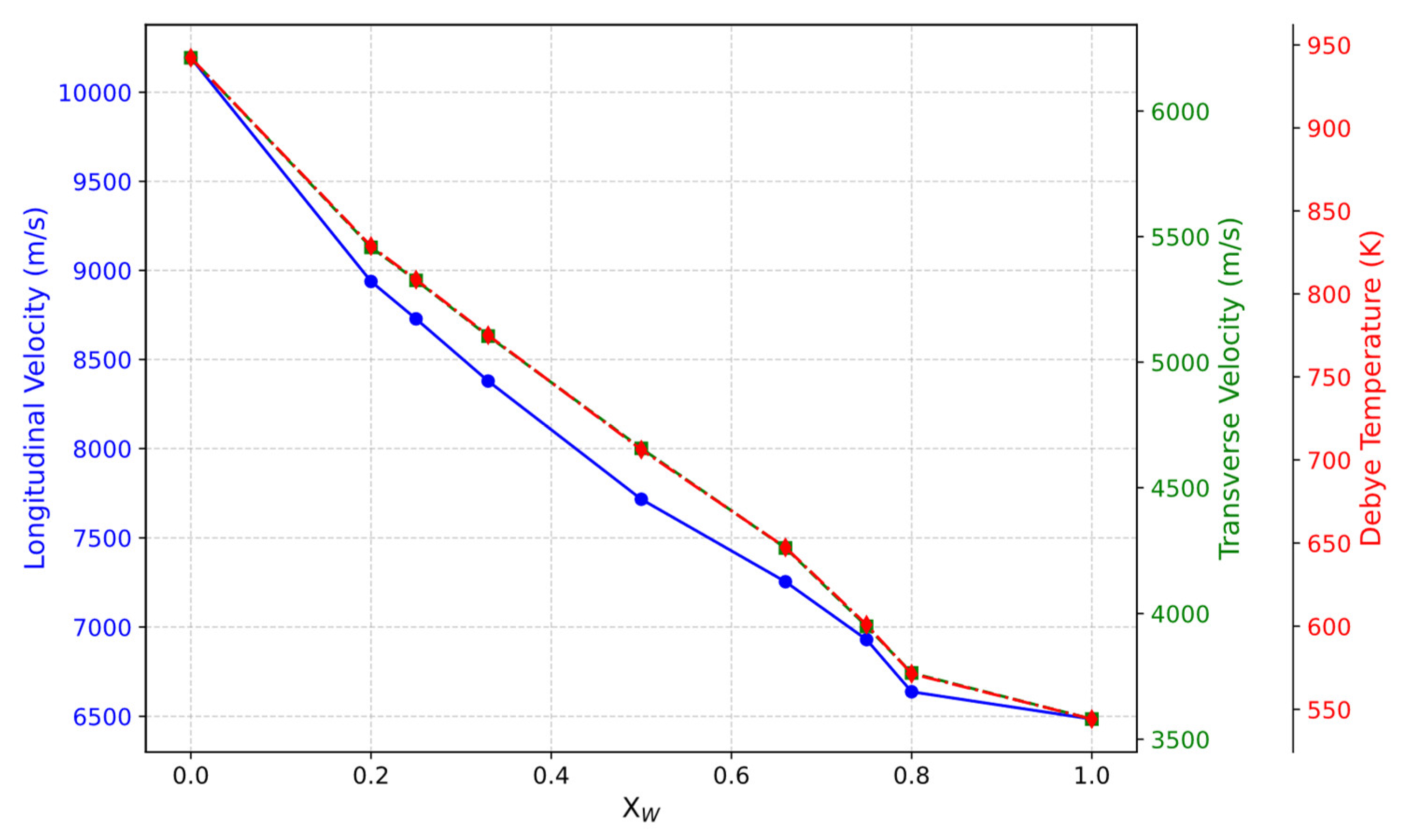

3.2. Mechanical Properties

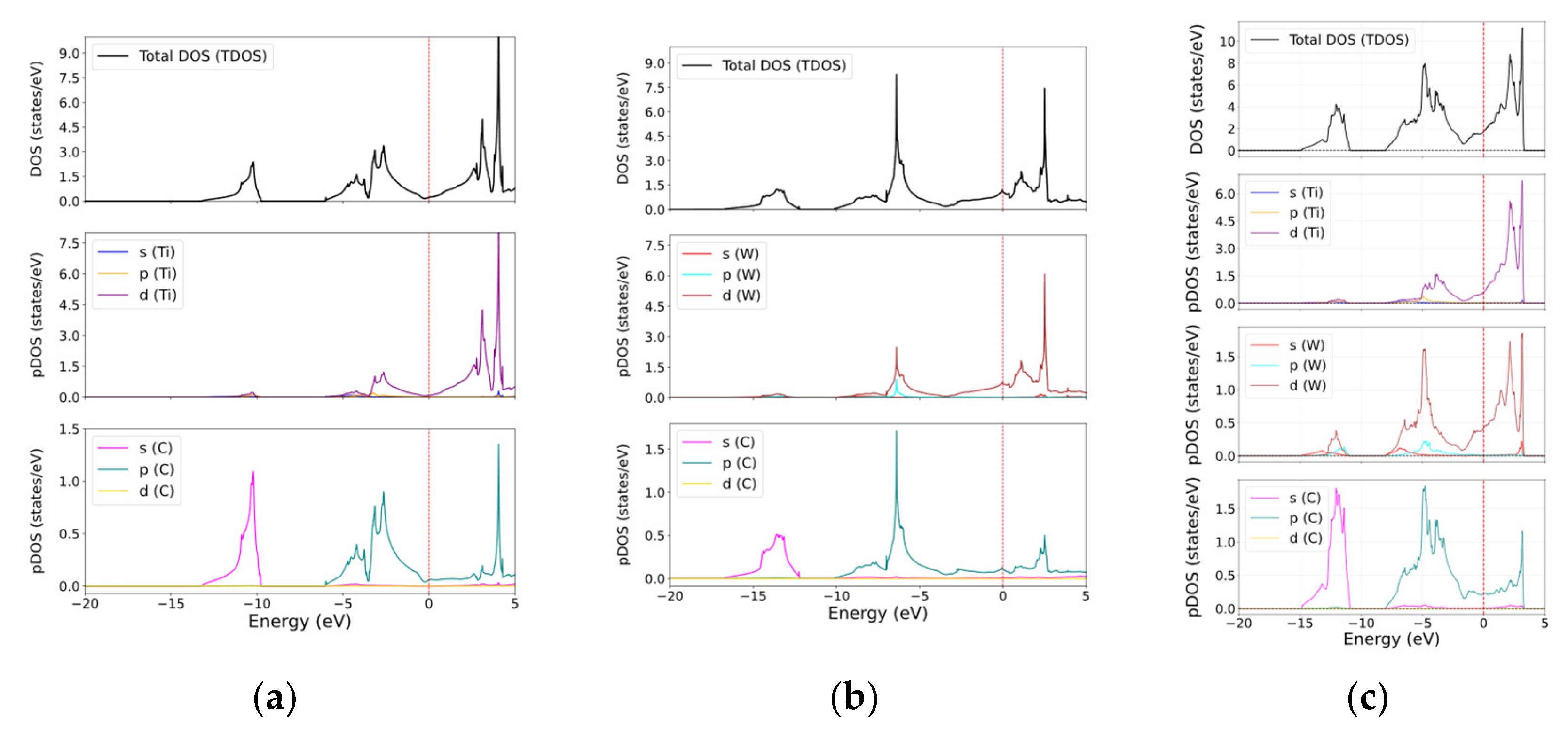

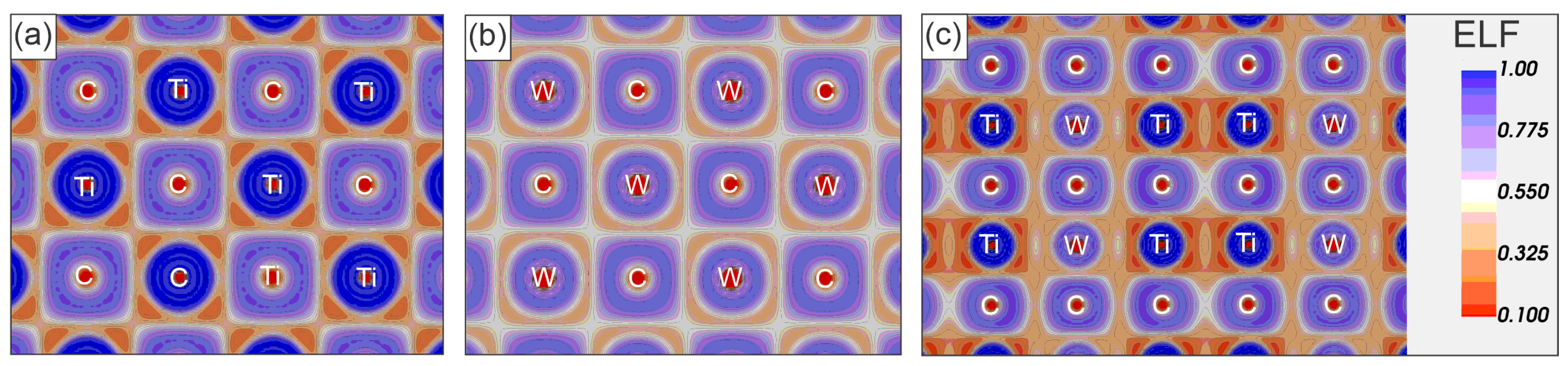

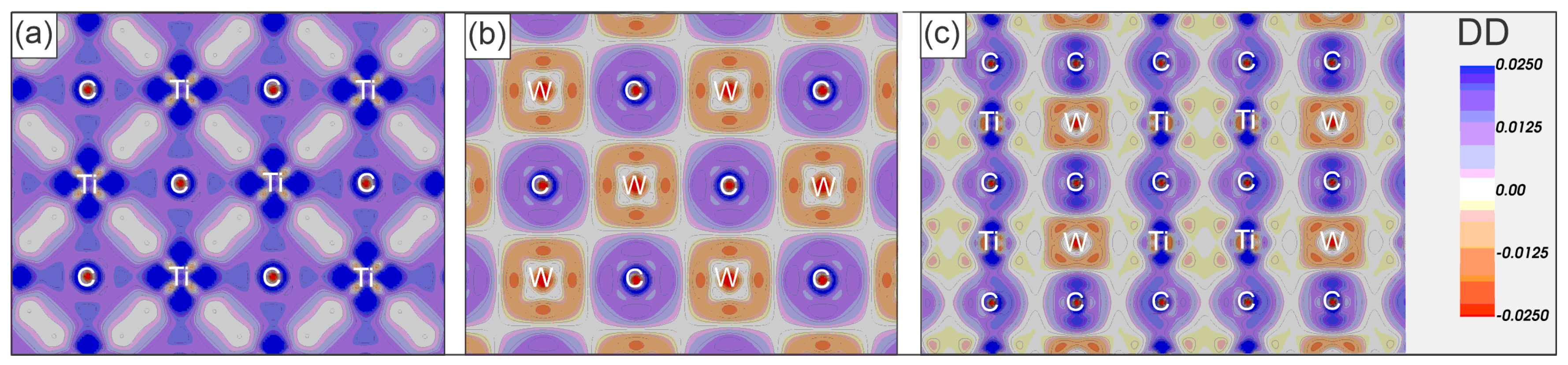

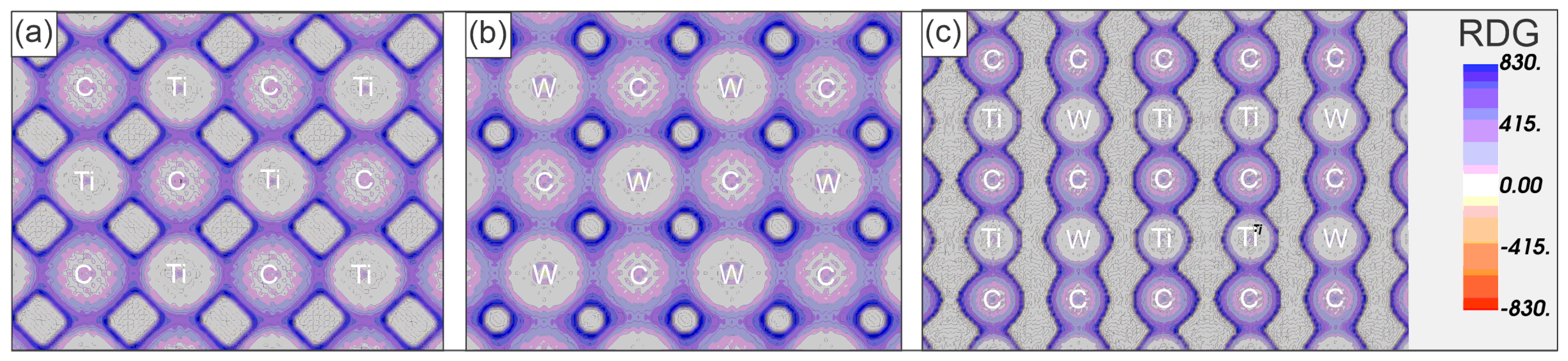

3.3. Electronic Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jonsson, S. Assessment of the Ti-W-C System and Calculations in the Ti-W-C-N System. International Journal of Materials Research 1996, 87, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara, R.V. Phase Equilibria in the System Tungsten—Carbon. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 1965, 48, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Jung, J.; Kang, S.; Jeong, B.W.; Lee, C.-K.; Ihm, J. The Carbon Nonstoichiometry and the Lattice Parameter of (Ti1−xWx)C1−y. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2010, 30, 1519–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Guindal, M.J.; Contreras, L.; Turrillas, X.; Vaughan, G.B.M.; Kvick, Å.; Rodríguez, M.A. Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis of TiC–WC Composite Materials. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2006, 419, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutsak, D.L.; Prysyazhnyuk, P.M.; Karpash, M.O.; Pylypiv, V.M.; Kotsyubynsky, V.O. Formation of Structure and Properties of Composite Coatings TiB2-TiC-Steel Obtained by Overlapping of Electric-Arc Surfacing and Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis. Metallofizika i Noveishie Tekhnologii 2016, 38, 1265–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wu, H.; You, M.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y. Improving Wear Resistance and Friction Stability of FeNi Matrix Coating by In-Situ Multi-Carbide WC-TiC via PTA Metallurgical Reaction. Surface and Coatings Technology 2019, 378, 124957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foong, L.K.; Jume, B.H.; Xu, C. Densification Behavior and Mechanical Properties of Hot-Pressed TiC–WC Ceramics. Ceramics International 2020, 46, 28316–28323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Bielawski, M. Ab Initio Study on Fracture Toughness of Ti0.75X0.25C Ceramics. Journal of Materials Science 2007, 42, 9713–9716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhuo, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, C.; Wang, C.; Yang, Q. Investigation on WC/TiC Interface Relationship in Wear-Resistant Coating by First-Principles. Surface and Coatings Technology 2016, 305, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.-M.; Wang, Y.-J.; Zhou, Y. Thermomechanical Properties of TiC Particle-Reinforced Tungsten Composites for High Temperature Applications. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials 2003, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, D.Y.; Fan, J.L.; Gong, H.R. Thermodynamic and Mechanical Properties of TiC from Ab Initio Calculation. Journal of Applied Physics 2014, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonenko, V.; Pivovarov, L.K. Tungsten Carbide with an FCC Lattice. Metal Science and Heat Treatment 1968, 10, 732–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Jin, N.; Ye, J.; Zhuang, D.; Liu, Y. A First Principles Investigation on the Solid Solution Behavior of Transition Metal Elements (W, Mo, Ta, Cr) in Ti(C,N). International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials 2021, 99, 105605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H.; Lee, C.-H.; Heo, Y.-U.; Suh, D.-W. Stability of (Ti, M)C (M = Nb, V, Mo and W) Carbide in Steels Using First-Principles Calculations. Acta Materialia 2012, 60, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.W.D.; Williams, A.R. Density-Functional Theory Applied to Phase Transformations in Transition-Metal Alloys. Phys. Rev. B 1983, 27, 5169–5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, W.; Sham, L.J. Self-Consistent Equations Including Exchange and Correlation Effects. Physical review 1965, 140, A1133–A1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prysyazhnyuk, P.; Shlapak, L.; Semyanyk, I.; Kotsyubynsky, V.; Troshchuk, L.; Korniy, S.; Artym, V. Analysis of the Effects of Alloying with Si and Cr on the Properties of Manganese Austenite Based on AB INITIO Modelling. Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies 2020, 6, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, J.; Kresse, G. The Vienna AB-Initio Simulation Program VASP: An Efficient and Versatile Tool for Studying the Structural, Dynamic, and Electronic Properties of Materials. In Properties of Complex Inorganic Solids; Springer US, 1997; pp. 69–82.

- Furness, J.W.; Kaplan, A.D.; Ning, J.; Perdew, J.P.; Sun, J. Accurate and Numerically Efficient r2SCAN Meta-Generalized Gradient Approximation. The journal of physical chemistry letters 2020, 11, 8208–8215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walle, A. van de; Asta, M.D.; Ceder, G. The Alloy Theoretic Automated Toolkit: A User Guide. Calphad 2002, 26, 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walle, A. van de; Tiwary, P.; Jong, M. de; Olmsted, D.L.; Asta, M.; Dick, A.; Shin, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.-Q.; Liu, Z.-K. Efficient Stochastic Generation of Special Quasirandom Structures. Calphad 2013, 42, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, A.; Nesper, R.; Wengert, S.; Fässler, T.F. ELF: The Electron Localization Function. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English 1997, 36, 1808–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prandini, G.; Marrazzo, A.; Castelli, I.E.; Mounet, N.; Marzari, N. Precision and Efficiency in Solid-State Pseudopotential Calculations. npj Computational Materials 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannozzi, P.; Baroni, S.; Bonini, N.; Calandra, M.; Car, R.; Cavazzoni, C.; Ceresoli, D.; Chiarotti, G.L.; Cococcioni, M.; Dabo, I.; et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: A Modular and Open-Source Software Project for Quantum Simulations of Materials. Journal of physics: Condensed matter 2009, 21, 395502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R. The Elastic Behaviour of a Crystalline Aggregate. Proceedings of the Physical Society A 1952, 65, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-Q.; Niu, H.; Li, D.; Li, Y. Modeling Hardness of Polycrystalline Materials and Bulk Metallic Glasses. Intermetallics 2011, 19, 1275–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Xu, B.; Zhao, Z. Microscopic Theory of Hardness and Design of Novel Superhard Crystals. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials 2012, 33, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teter, D.M. Computational Alchemy: The Search for New Superhard Materials. MRS bulletin 1998, 23, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhnik, E.; Oganov, A.R. A Model of Hardness and Fracture Toughness of Solids. Journal of Applied Physics 2019, 126, 125109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, N.; Sa, B.; Zhou, J.; Sun, Z. Theoretical Investigation on the Transition-Metal Borides with Ta3B4-Type Structure: A Class of Hard and Refractory Materials. Computational Materials Science 2011, 50, 1559–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prysyazhnyuk, P.; Di Tommaso, D. The Thermodynamic and Mechanical Properties of Earth-Abundant Metal Ternary Borides Mo2 (Fe, Mn) B2 Solid Solutions for Impact-and Wear-Resistant Alloys. Materials Advances 2023, 4, 3822–3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, V.; Xu, N.; Liu, J.-C.; Tang, G.; Geng, W.-T. VASPKIT: A User-Friendly Interface Facilitating High-Throughput Computing and Analysis Using VASP Code. Computer Physics Communications 2021, 267, 108033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivashchenko, V.I.; Čaplovič, Ľ.; Shevchenko, V.I.; Gorb, L.; Leszczynski, J. Stability and Mechanical, Thermodynamic and Optical Properties of WC Polytypes and the TiC-WC Solid Solutions: A First-Principles Study. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 2023, 183, 111652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nino, A.; Izu, Y.; Sekine, T.; Sugiyama, S.; Taimatsu, H. Effects of TaC and TiC Addition on the Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Binderless WC. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials 2019, 82, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, A.; Hara, A. High Temperature Hardness of WC, TiC, TaC, NbC and Their Mixed Carbides. Journal of the Japan Society of Powder and Powder Metallurgy 1965, 12, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).