Submitted:

23 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods and Results

Data Sources and Searches

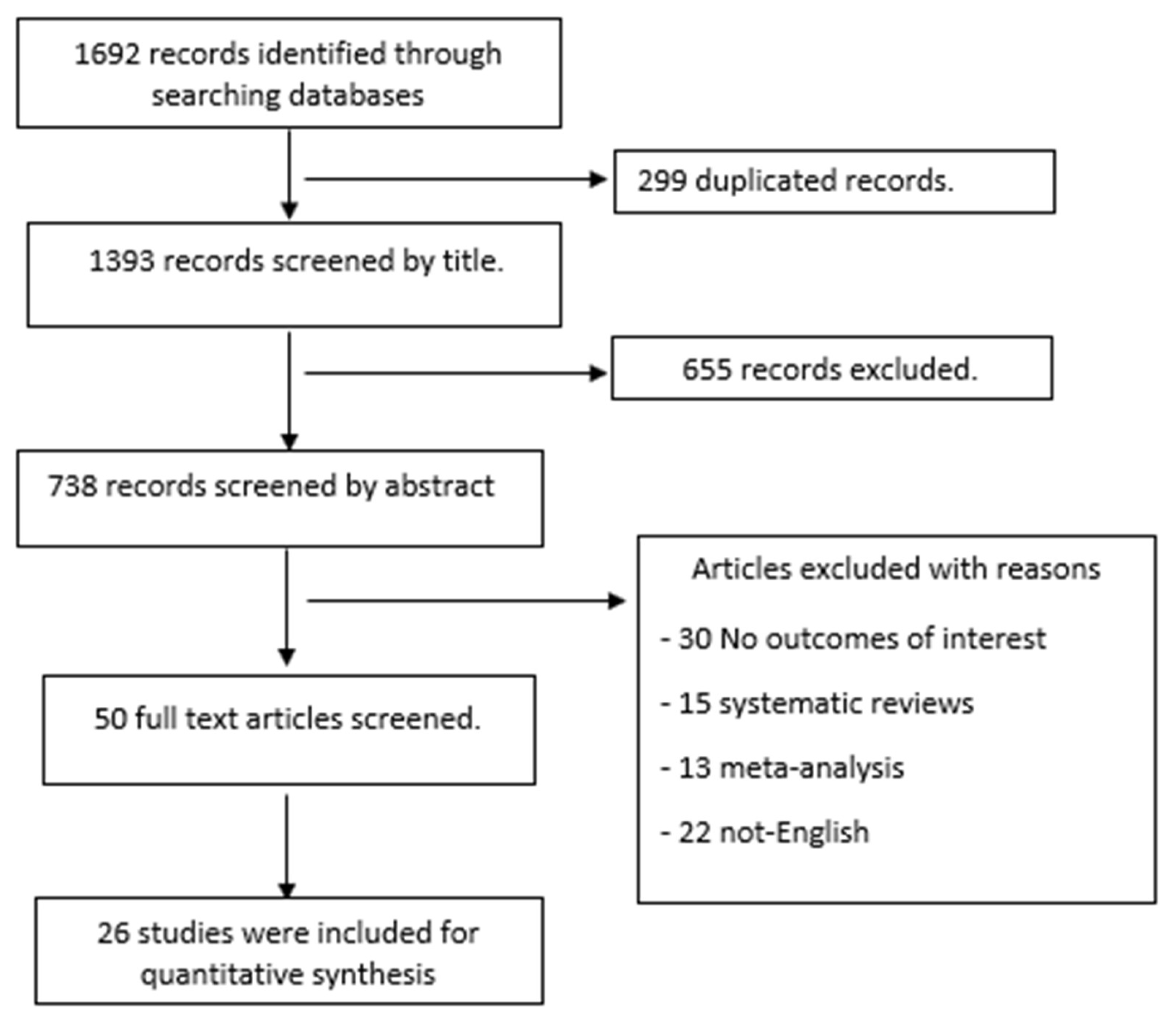

Study Eligibility Criteria and Selection

Data Extraction

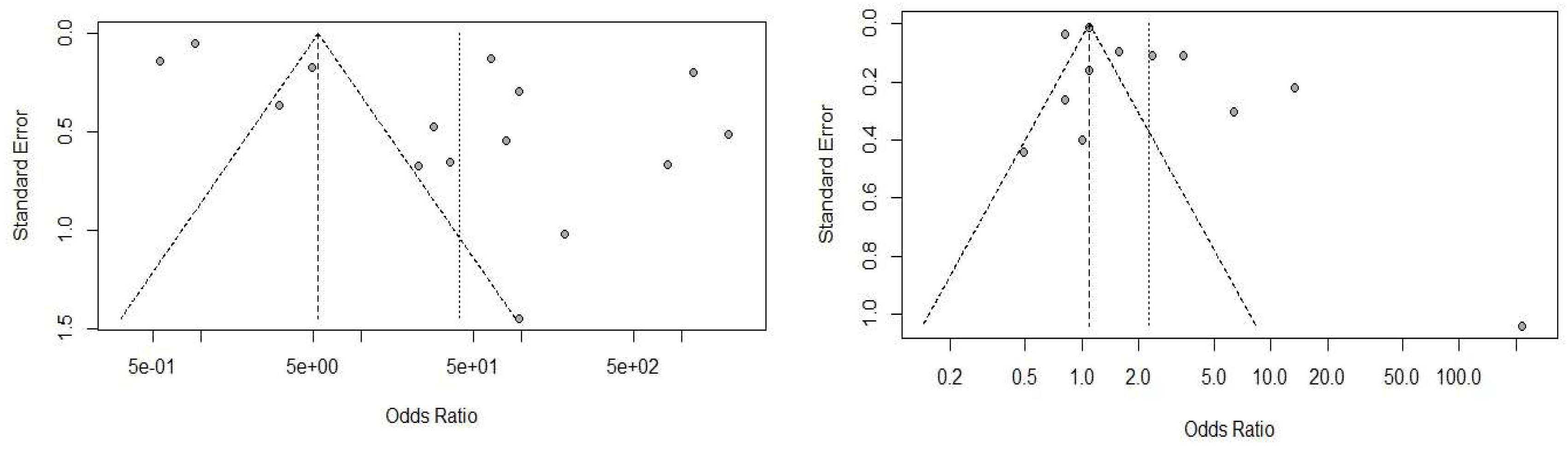

Statistical Analysis

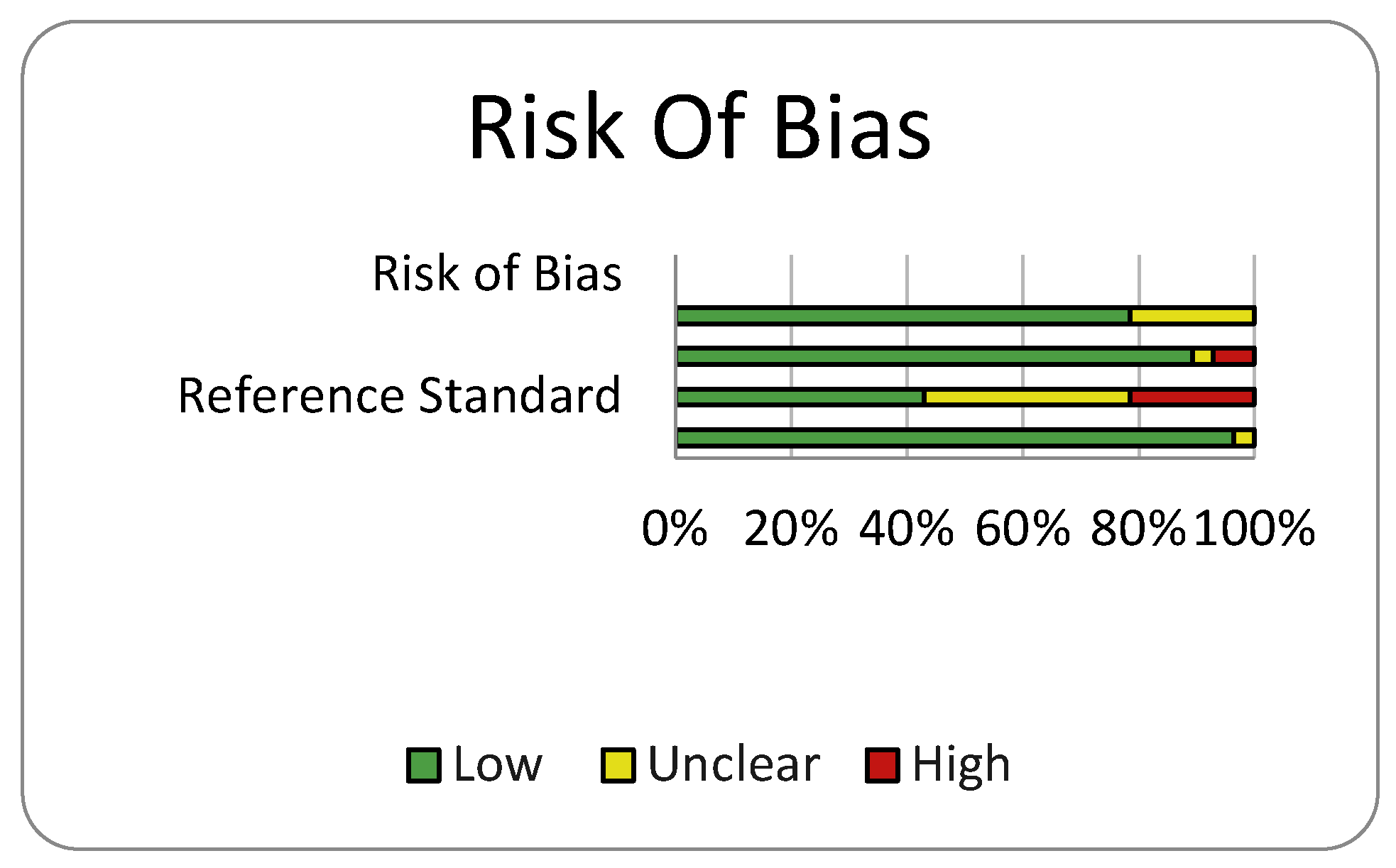

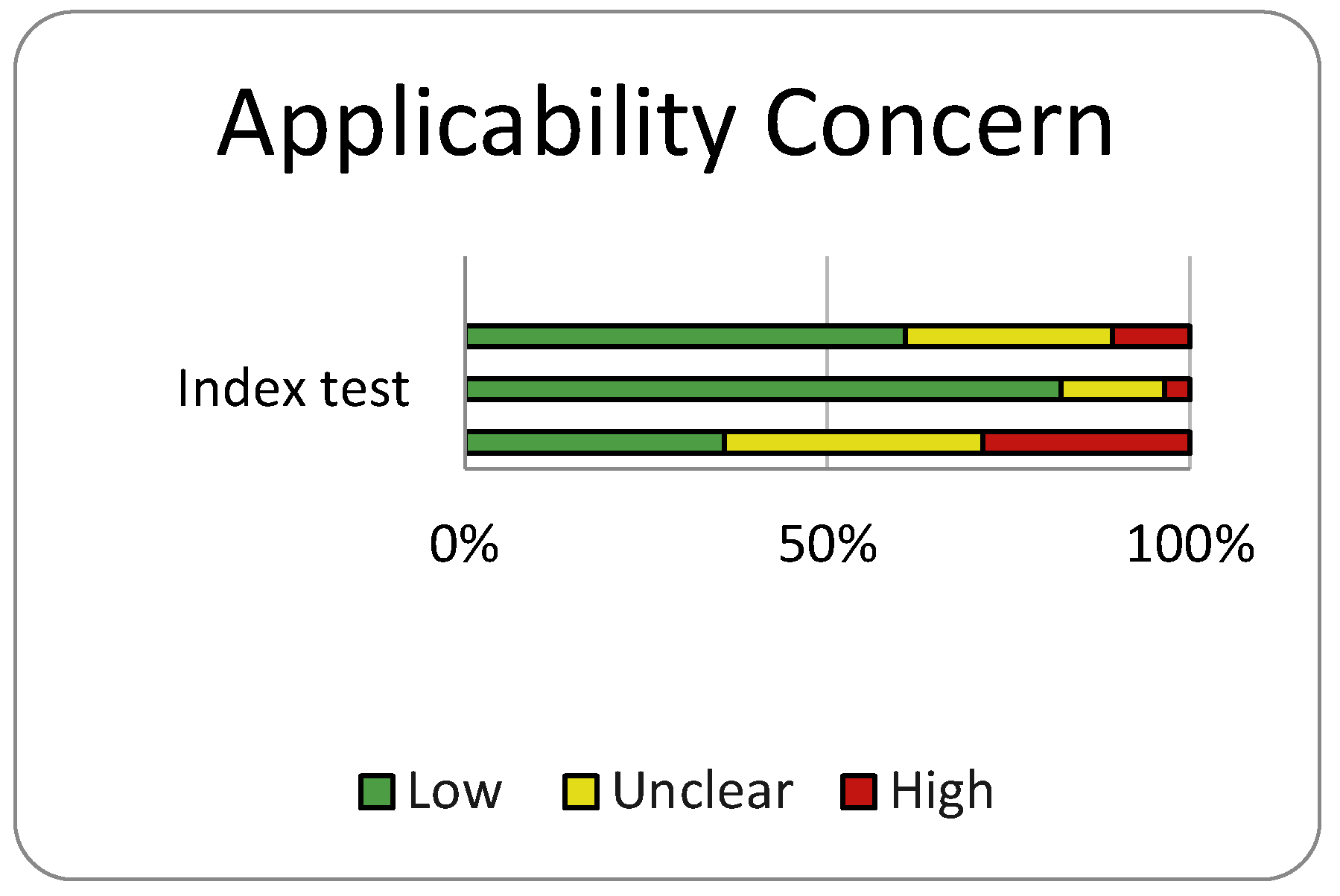

Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

Results

Study Selection and Characteristics

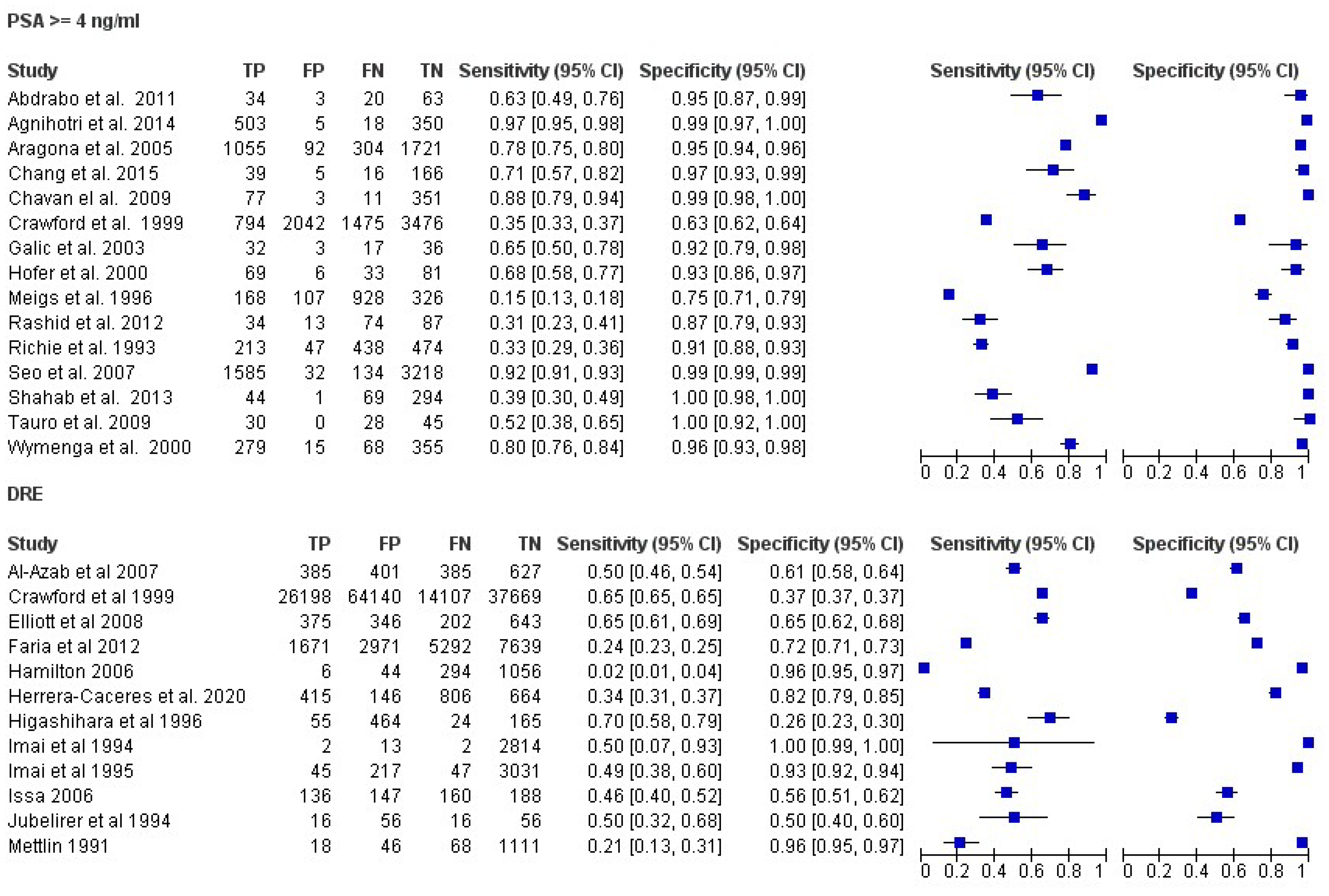

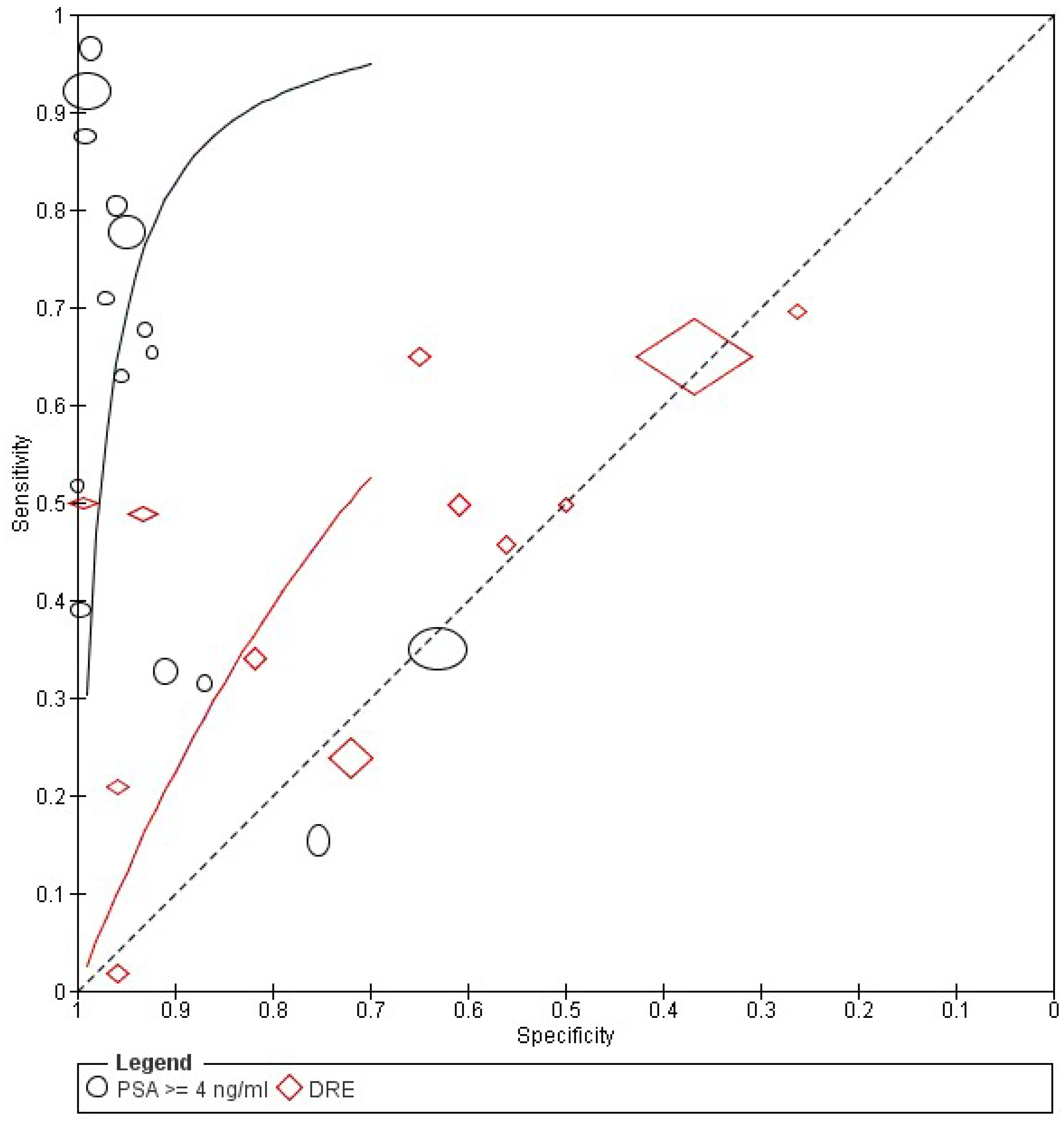

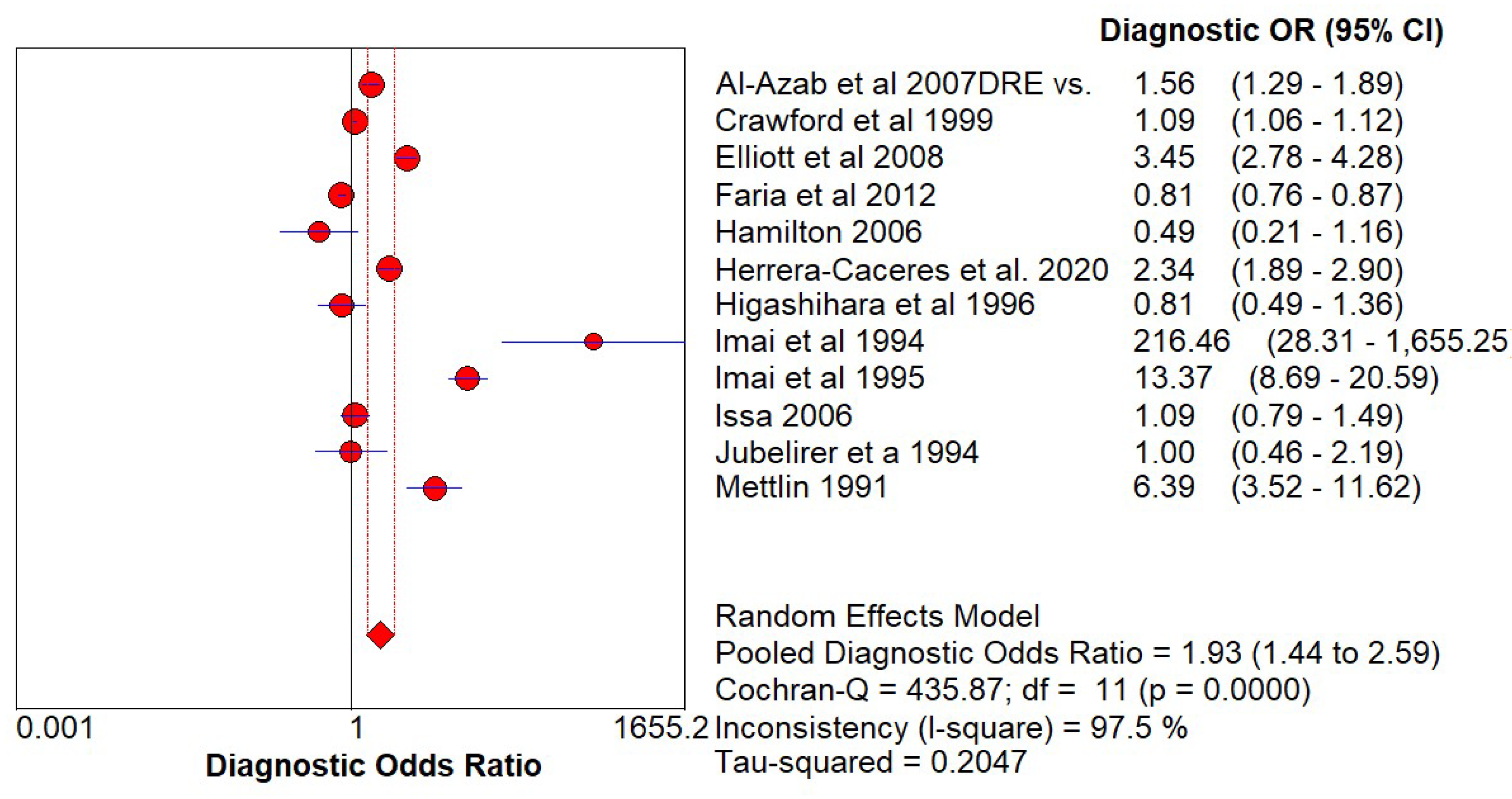

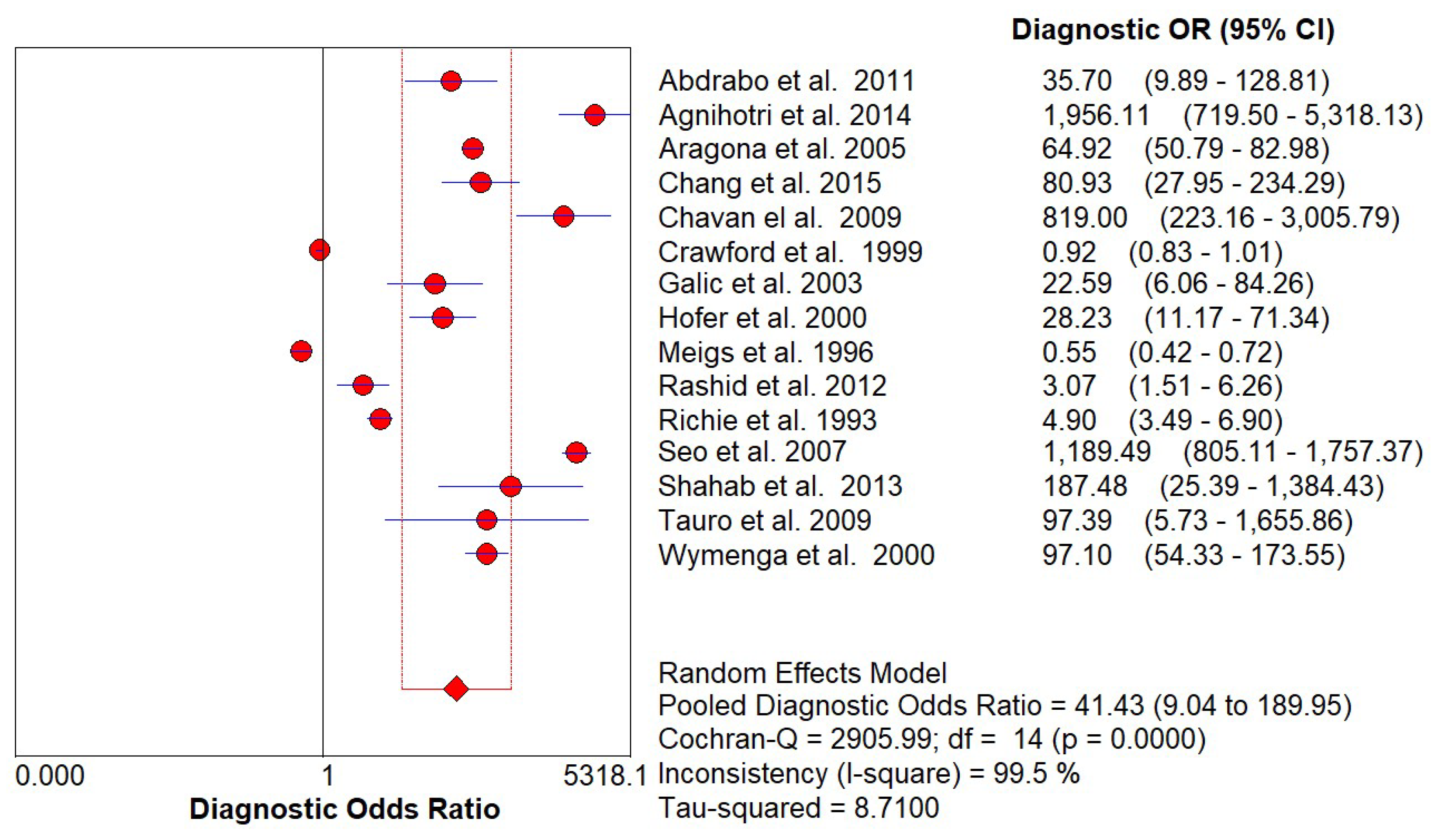

Diagnostic Accuracy of PSA and DRE

Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Center, M., Siegel, R., and Jemal, A. (2011). American Cancer Society. Global Cancer Facts and Figures, 2nd Edn. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society, 1–58.

- A prospective evaluation of plasma prostate-specific antigen for detection of prostatic cancer - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2023 Apr 28]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7529341/.

- Scardino PT, Weaver R, Hudson MA. Early detection of prostate cancer. Hum Pathol [Internet]. 1992 [cited 2023 Apr 19];23(3):211–22. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1372877/.

- Brawer MK, Chetner MP, Beatie J, Buchner DM, Vessella RL, Lange PH. Screening for prostatic carcinoma with prostate specific antigen. J Urol [Internet]. 1992 [cited 2023 Apr 28];147(3 Pt 2):841–5. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1371559/.

- Ekwueme DU, Stroud LA, Chen Y. Peer Reviewed: Cost Analysis of Screening for, Diagnosing, and Staging Prostate Cancer Based on a Systematic Review of Published Studies. Prev Chronic Dis [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2023 Apr 28];4(4). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC2099265/.

- Smith DS, Catalona WJ, Herschman JD. Longitudinal screening for prostate cancer with prostate-specific antigen. JAMA [Internet]. 1996 Oct 23 [cited 2023 Apr 28];276(16):1309–15. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8861989/.

- Song JM, Kim CB, Chung HC, Kane RL. Prostate-Specific Antigen, Digital Rectal Examination and Transrectal Ultrasonography: A Meta-Analysis for This Diagnostic Triad of Prostate Cancer in Symptomatic Korean Men. Yonsei Med J [Internet]. 2005 Jun 6 [cited 2023 Apr 28];46(3):414. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC2815820/.

- Schröder FH, Van Der Maas P, Beemsterboer P, Kruger AB, Hoedemaeker R, Rietbergen J, et al. Evaluation of the Digital Rectal Examination as a Screening Test for Prostate Cancer. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute [Internet]. 1998 Dec 2 [cited 2023 Apr 28];90(23):1817–23. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article/90/23/1817/2520677.

- Hoogendam A, Buntinx F, De Vet HCW. The diagnostic value of digital rectal examination in primary care screening for prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Fam Pract [Internet]. 1999 Dec 1 [cited 2023 Apr 28];16(6):621–6. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/fampra/article/16/6/621/475662.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pmed.1000100).

- Digital rectal examination is not useful to early detect prostate cancers - Uroweb [Internet]. [cited 2023 Apr 28]. Available from: https://uroweb.org/press-releases/digital-rectal-examination-is-not-useful-to-early-detect-prostate-cancers.

- Chodak GW, Keller P, Schoenberg HW. Assessment of screening for prostate cancer using the digital rectal examination. J Urol [Internet]. 1989 [cited 2023 Apr 28];141(5):1136–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2709500/.

- The American Cancer Society National Prostate Cancer Detection Project. Findings on the detection of early prostate cancer in 2425 men - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2023 Apr 28]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1710531/.

- Pedersen K V., Carlsson P, Varenhorst E, Lofman O, Berglund K. Screening for carcinoma of the prostate by digital rectal examination in a randomly selected population. Br Med J [Internet]. 1990 Apr 21 [cited 2023 Apr 28];300(6731):1041–4. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/300/6731/1041.

- Lee F, Littrup PJ, Torp-Pedersen ST, Mettlin C, McHugh TA, Gray JM, et al. Prostate cancer: comparison of transrectal US and digital rectal examination for screening. Radiology [Internet]. 1988 [cited 2023 Apr 28];168(2):389–94. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3293108/.

- Kemple T, Chadwick DJ, Gillatt DA, Abrams P, Gingell JC, Astley JP, et al. Pilot study of screening for prostate cancer in general practice. Lancet [Internet]. 1991 Sep 7 [cited 2023 Apr 28];338(8767):613–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1715503/.

- Bretton PR. Prostate-specific antigen and digital rectal examination in screening for prostate cancer: a community-based study. South Med J [Internet]. 1994 [cited 2023 Apr 28];87(7):720–3. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7517580/.

- Andermann A, Blancquaert I, Beauchamp S, Déry V. Revisiting Wilson and Jungner in the genomic age: a review of screening criteria over the past 40 years. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 2008 Apr [cited 2023 Apr 28];86(4):317–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18438522/.

- Catalona WJ, Smith DS, Ornstein DK. Prostate cancer detection in men with serum PSA concentrations of 2.6 to 4.0 ng/mL and benign prostate examination. Enhancement of specificity with free PSA measurements. JAMA [Internet]. 1997 May 14 [cited 2023 Apr 28];277(18):1452–5. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9145717/.

- Catalona WJ, Smith DS, Ratliff TL, Basler JW. Detection of Organ-Confined Prostate Cancer Is Increased Through Prostate-Specific Antigen—Based Screening. JAMA [Internet]. 1993 Aug 25 [cited 2023 Apr 28];270(8):948–54. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/408074.

- Catalona WJ, Richie JP, Ahmann FR, Hudson MA, Scardino PT, Flanigan RC, et al. Comparison of digital rectal examination and serum prostate specific antigen in the early detection of prostate cancer: results of a multicenter clinical trial of 6,630 men. J Urol [Internet]. 1994 [cited 2023 Apr 28];151(5):1283–90. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7512659/.

- Thompson IM, Ankerst DP, Chi C, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Lucia MS, et al. Assessing prostate cancer risk: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst [Internet]. 2006 Apr 19 [cited 2023 Apr 28];98(8):529–34. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16622122/.

- Weining C, Semjonow A, Hertle L. Nutzen verschiedener Verfahren zur Verbesserung der Spezifitat von PSA in der Prostatakarzinomdiagnostik. Urologe - Ausgabe B [Internet]. 1997 Apr 8 [cited 2023 Apr 28];37(3):216–20. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s001310050078.

| Study | Year | Country | Design | Patients Number | Patients Underwent Biopsy No | Age Range | Diagnostic Criteris | Reference Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chang et al. | 2015 | Taiwan | Retrospective chart review | 225 | 225 | N/A | PSA ≥ 4 ng/mL | Biopsy |

| Agnihotri et al. | 2014 | India | Prospective study | 4702 | 875 | 50-75 | PSA ≥ 4 ng/mL | Biopsy |

| Shahab et al. | 2013 | Indonesia | Retrospective study | 404 | 404 | 34-84 | PSA ≥ 4 ng/mL | Biopsy |

| Rashid et al. | 2012 | Bangladesh | Prospective study | 206 | 206 | Over50 | PSA ≥ 4 ng/mL | Biopsy |

| Abdrabo et al. | 2011 | Sudan | Prospective study | 118 | 118 | 56-83 | PSA ≥ 4 ng/mL | Biopsy |

| Chavan el al. | 2009 | India | Retrospective study | 922 | 440 | 40-95 | PSA ≥ 4 ng/mL | Biopsy |

| Tauro et al. | 2009 | India | Prospective study | 100 | 100 | 56-75 | PSA ≥ 4 ng/mL | Biopsy |

| Seo et al. | 2007 | Korea | Prospective study | 4967 | 4967 | 40-96 | PSA ≥ 4 ng/mL | Biopsy |

| Aragona et al. | 2005 | Italy | Prospective cohort study | 16298 | 3171 | 40-75 | PSA ≥ 4 ng/mL | Biopsy |

| Galic et al. | 2003 | Croatia | Prospective controlled study | 944 | 88 | Over 50 | PSA ≥ 4 ng/mL | Biopsy |

| Hofer et al. | 2000 | Germany | Prospective study | 188 | 188 | 40-79 | PSA ≥ 4 ng/mL | Biopsy |

| Wymenga et al. | 2000 | The Netherlands | Prospective study | 716 | 716 | N/A | PSA ≥ 4 ng/mL | Biopsy |

| Crawford et al. | 1999 | USA | Retrospective of prospectively collected data. | 142111 | 4160 | 40-79 | PSA ≥ 4 ng/mL/ DRE | Biopsy |

| Meigs et al. | 1996 | USA | Retrospective of prospectively collected data. | 1554 | N/A | 50-79 | PSA ≥ 4 ng/mL | Biopsy |

| Richie et al. | 1993 | USA | Prospective clinical trial. | 6630 | 1167 | 50-96 | PSA ≥ 4 ng/mL | Biopsy |

| Al-Azab et al. | 2007 | Canada | Retrospective chart review | 1796 | 1796 | 40-93 | DRE/PSA | Biopsy |

| Elliott et al. | 2008 | USA | Retrospective review of prospectively collected data | 1564 | 1564 | 60-75 | DRE/PSA | Biopsy |

| Faria et al. | 2012 | Brazil | Prospective cohort study | 17571 | 1647 | 45-98 | DRE/PSA | Biopsy |

| Higashihara et al. | 1996 | Japan | Prospective clinical trial | 701 | 116 | 50-92 | DRE/PSA | Biopsy |

| Imai et al. | 1994 | Japan | Prospective study | 1680 | 132 | 39-89 | DRE/PSA | Biopsy |

| Imai et al. | 1995 | Japan | Prospective study | 3276 | 254 | 40-89 | DRE/PSA | Biopsy |

| Jubelirer et a | 1994 | USA | Prospective study | 142 | 15 | 50-85 | DRE/PSA | Biopsy |

| Mettlin | 1991 | USA | Prospective cohort study | 1218 | 330 | 55-70 | DRE/PSA | Biopsy |

| Hamilton | 2006 | UK | Case-control | 1297 | 217 | Over 40 | DRE/PSA | Biopsy |

| Issa | 2006 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | 628 | 628 | 40-89 | DRE/PSA | Biopsy |

| Herrera-Caceres | 2020 | Canada | Retrospective study | 2031 | 2031 | 60-71 | DRE/PSA | Biopsy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).