1. Introduction

Between 27% and 53% of all patients undergoing curative radical prostatectomy (RP) or prostate cancer (PCa) radiation therapy (RT) develop a biochemical recurrence (BCR) (1). The biochemical recurrence, after radical prostatectomy, is defined as PSA > 0,2 ng/ml with a second confirmatory level of prostate specific antigen of >0.2 ng/mL (2). BCR can be a surrogate marker of prostate cancer recurrence. However, it is important to note that a rising PSA level does not always mean that cancer has already metastasized, and that the natural history of PSA-only recurrence can be prolonged Cornford et al. 2020; Mottet et al. 2021). However, a systematic review and meta-analysis that investigated the impact of BCR on outcome endpoints concluded that patients with BCR are at an increased risk of developing distant metastases and cancer-specific mortality (5). The European Association Guidelines, recommend that patients with pathological ISUP (International Society Urological Pathology) grade 4–5, combined with locally advanced disease in specimen (pT3) and with or without surgical margins, are at high risk for BCR (Van den pathological ISUP grade 4–5; Broeck et al. 2019) and should be offer adjuvant intervention after prostatectomy. The low/intermediate risk patients’ ISUP 1-3 and pT2 may not require immediate intervention (7).

Adding mp-MR information may assist clinicians to better stratify patients and accurately predict the outcome of patients with tumors that have spread outside the prostate gland. By incorporating MRI into clinical staging algorithms, clinicians can create more accurate and personalized treatment plans for patients with extra prostatic cancer spread (8–12).

Our purpose is to analyze the impact of the previous model, developed by the authors, to predict pECE+ on the biochemical recurrence free survival (BCFS), after prostatectomy. Additionally, we aim to determine the adverse MRI features in patients with low/intermediate risk for BCR.

2. Materials and Methods

This prospective single-center study included 228 participants from a previous cohort used to perform and validate a predictive model to detect pECE+ in patients operated by RARP at Hospital da Luz, Lisbon (13). All patients had a diagnostic of PCa and underwent an MRI exam with a standard protocol and they were operated on between 2015 and 2020. Each participant was subsequently followed from the date of prostatectomy until May 2022 in order to record the exact date of biochemical recurrence. Fifty-one patients were excluded because they were lost for follow-up (

Figure S1).

The outcome of the study, biochemical recurrence-free survival (BCRFS), was defined as the time-lapse between curative prostatectomy to the earliest date of BCR, which was defined as a prostate-specific antigen level of 0.2 ng/mL after an interval of undetectable prostate-specific antigen.

Features:

We used all the covariates from the pECE+ predictive model described in our previous paper (13). Therefore, the covariates analyzed in this study were:

- -

Semantic MRI interpretative features set (black striation periprostatic fat, obliteration of the rectoprostatic angle, measurable ECE on MRI (mECE+), smooth capsular bulging, capsular disruption, unsharp margin, and irregular contour) used for predicting pECE+ on MRI.

- -

The index lesion length (ILL) corresponds to the major length of the index lesion; and the tumor capsular contact length (TCCL), which is the contact length of the index lesion with the prostate capsule. Both were measured in millimeters on axial T2 images, and we used a curvilinear ruler to draw the TCCL.

- -

PI-RADS V2 for characterization of the index lesion (14).

- -

Gleason score (GS) on the prostate specimen. The GS was divided into low/intermediate risk ISUP 1-3 (GS ≤ 4+3) and high risk, ISUP 4-5 (GS ≥ 4+4) for BCR, according to the literature (7).

- -

The clinical and laboratory data evaluated included the age of the patients, PSA levels at surgery, PSA density (PSA/prostate volume), and MRI and surgery dates. Patients’ data were anonymized, collected in an Excel database and organized according to the sugery dates. Categorization of the PSA: PSA<6 ng/ml, 6 ng/ml≤PSA<10 ng/ml and PSA≥10 ng/ml.

- -

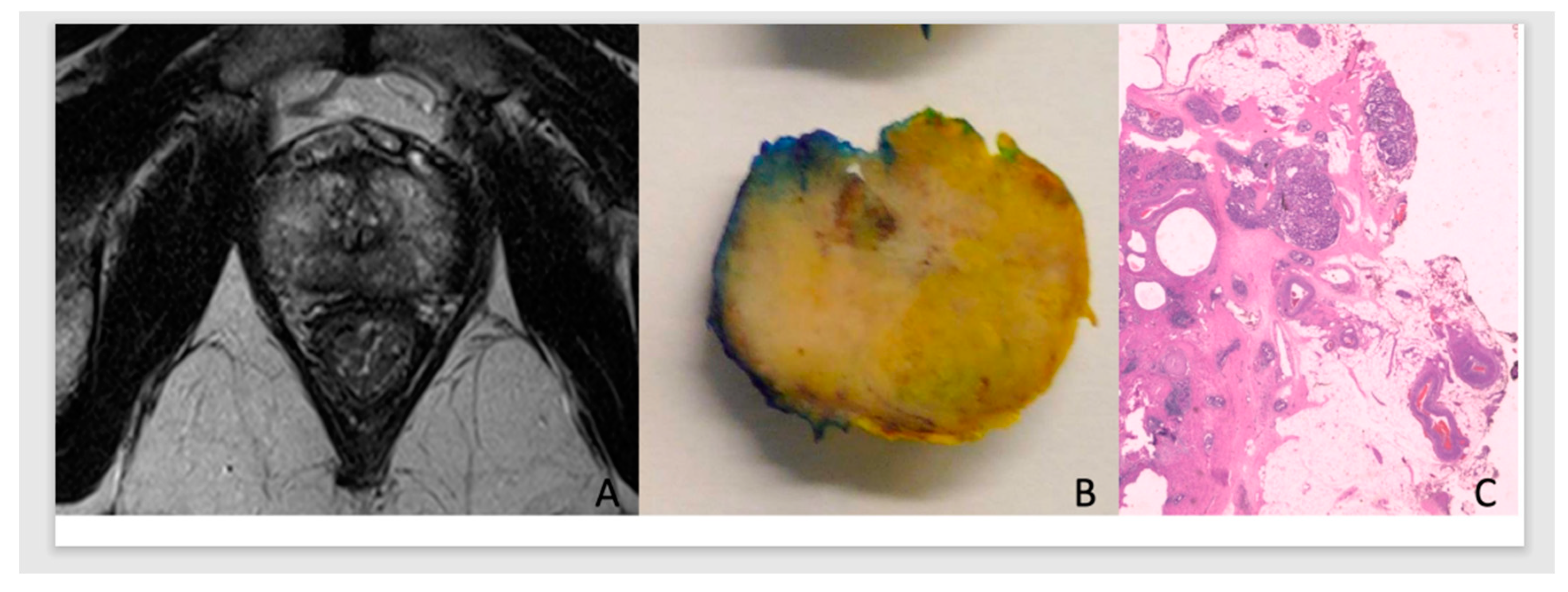

In this predictive analysis we added PCa pathological staging and surgical margins results of the prostate specimen. Tumors were classified as pECE negative (pECE−) if no tumoral cells were detected on extracapsular tissue, and pECE positive (pECE+) if a preence of a tumoral extension beyond the periphery of the prostate gland was detected (

Figure 1). Positive surgical margins (PSM) refer to the presence of tumor cells beyond the inked surgical margins of the resected tumor.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

We conducted exploratory data analysis, including descriptive statistics and hypothesis testing, to compare patients with and without biochemical recurrence using risk features identified by Guerra et al. (13). Statistical tests included two-sample z-tests, Fisher's exact tests, and the Fisher-Freeman-Halton test. Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank tests were used to compare survival curves. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard models were applied, highlighting hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. We estimated survival curves for low/intermediate-risk and high-risk ISUP patients and examined the effect of mECE+ and pECE+ on biochemical recurrence risk. The analyses were conducted using R.

3. Results

3.1. Exploratory Analysis

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the patients according to the presence of biochemical recurrence (BCR+ or BCR−): 23% were BCR+ and 77% BCR (BCR-) after prostatectomy. In the exploratory analysis, all variables introduced in the previous predictive model to detect pECE+ were significantly different (p-values < 0.10) between patients BCR+ and BCR–, except the age of the participants. Patients with BCR+ had more extensive lesions, larger TCCL, higher PSA levels, smaller prostate size, and a higher PSAD ratio. Most patients with BCR+ had a PI-RADS score of 5 (75%). The majority of patients with BCR+ (82.5%) had ISUP 1-3; it is worth stressing that there were only 17 individuals in the whole sample (9.6% of the total) with ISUP > 3. The early semantic features for prediction pECE+ as smooth capsular bulging, unsharp margins, irregular contour and capsular disruption are present more often in patients BCR+ than patients BCR− (roughly, the percentage of BCR+ patients with each of these features is double that in BCR− patients). On the other hand, 89.8%, 71.5% and 76.6% of the patients with BCR− not present mECE+, PSM and pECE+, respectively).

Of low/intermediate risk-patients (112) with ISUP 1-3(GS<8) and pECE−, 15 patients (13%) had BCR+, and 97 patients (87) had BCR −. The mean of TCCL and tumor size were higher in the BCR+ group (TCCL: 12.5mm versus 8.4mm; Index lesion size: 14.8 versus 12.1mm), and they were statistically different between the two groups like some individually semantic MRI features as smooth capsular bulging capsular disruption, and PI-RADS score (

Table 2).

3.2. Survival Analysis

We analyzed the time between curative prostatectomy and biochemical recurrence (BCRFS). The main results are depicted in

Figure S2-S3 and

Table 3. The Kaplan-Meier estimate of the survival function for the global BCRFS is illustrated in

Figure S2. Estimates of BCRFS probability after curative prostatectomy were 95% (95% CI: ]92, 99[), 87% (95% CI: ]82, 93[), 79% (95% CI: ]72, 87[) at 1, 2 and 4 years, respectively (

Figure S2 and

Table 3).

We also estimated the survival curves for each categorical covariate under study. The goal was to evaluate the extent to which the survival curves differ across the categories of the covariates.

The results of the Kaplan-Meier estimate for the survival functions (BCRFS) stratified by pECE, measurable ECE on MRI, ISUP low/intermediate (GS ≤ 4+3) and high (GS ≥ 4+4) risk, index Lesion PIRADS v2, capsular disruption, TCCL, surgical margins and PSA levels categorized are illustrated in

Figure S3 A - H respectively and

Table 3. The log-rank test was used to compare the survival curves of the different strata for each covariate cited above.

At the 5% significance level, there are statistical differences between the two survival curves for BCRFS when stratifying by all variables (p-values < 0.05). The only exception is for index lesion PIRADS v2 (

Figure S1D).

The greater the TCCL, the higher the cumulative probability of biochemical recurrence. It is important to notice that the estimated cumulative probability of a patient’s recurrence with TCCL≥ 20mm at one year of follow-up is the same (11%) as a patient’s recurrence with TCCL< 10mm at four years of follow-up.

Patients with PSM have a higher risk for BCR than those with NSM, which increases over time (

Figure S3G,

Table 3). The estimated BCRFS probability is 91% for patients with PSM in the first-year post-surgery and 68% at four years of follow-up.

In our previous study (13), the GS > 7(3+4), which included grade groups 3,4 and 5, was identified as a relevant biomarker for pECE+. However, in our current preliminary analysis, only the GS ≥ 8 (grade group 4-5), has emerged as a relevant risk factor to BCR (p-value=0.044 for the log-rank test).

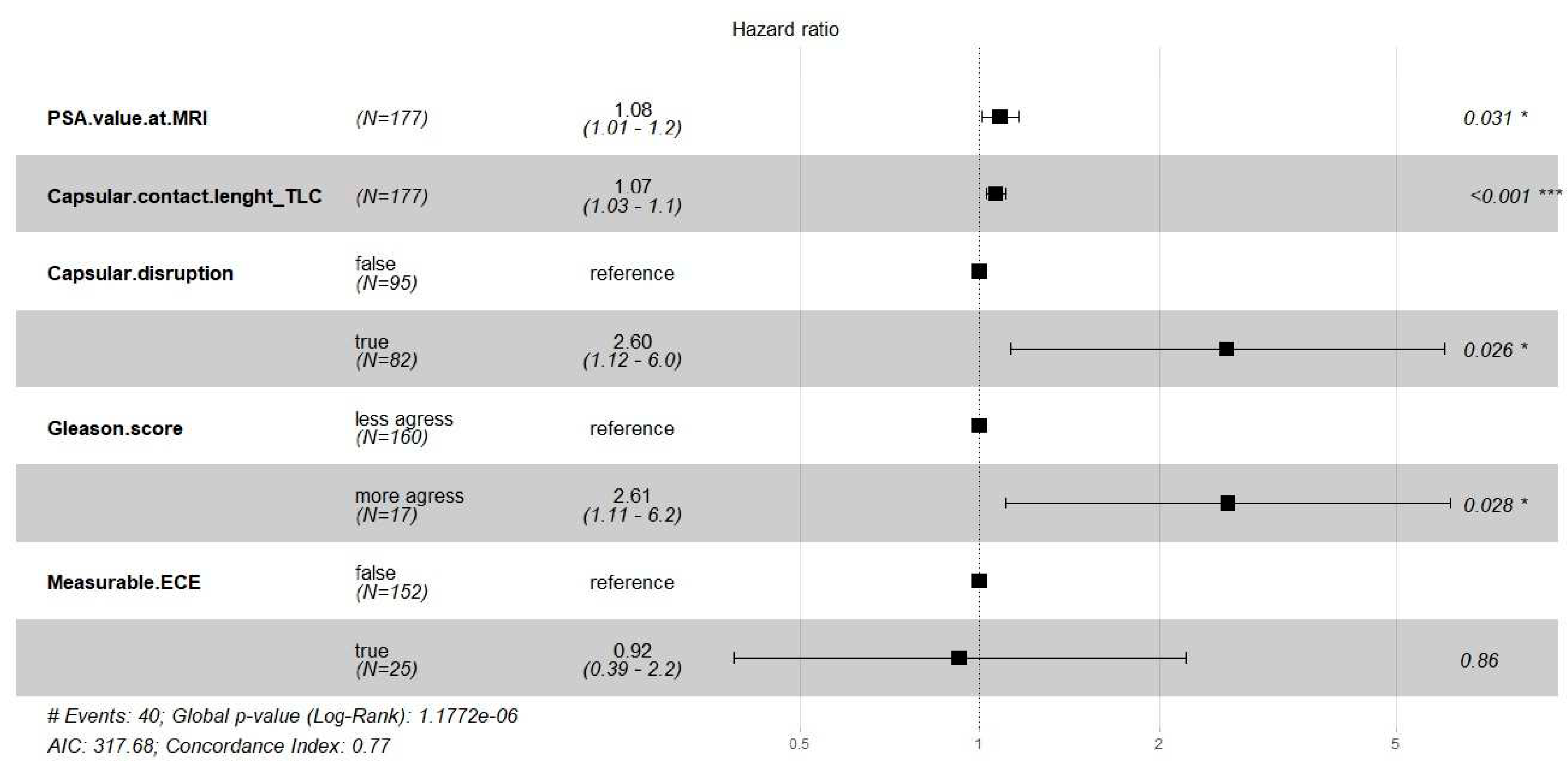

We fitted the Cox regression model to evaluate the effect of the semantic and clinical covariates on the time until biochemical recurrence. The main results are shown in

Table S1 and

Figure 2.

The multivariable Cox regression model showed that PSA, TCCL, capsular disruption, and Gleason score were significant risk factors for biochemical recurrence (BCR) (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

In this study, researchers aimed to investigate the relationship between a previously developed predictive model for detecting extracapsular extension (pECE+) on MRI and early-term oncologic outcomes, specifically biochemical recurrence (BCR) up to four years after prostatectomy. The study also aimed to analyze the MRI features that affect the probability of disease recurrence in low/intermediate-risk patients.

The study demonstrated that the prognostic features for detecting pECE+ on MRI, such as the presence of mECE+, capsular disruption and high tumor contact length (TCCL), also impacted on BCR+ as demonstrated in Cox regression and survival analysis. Patients without these signs on MRI (mECE-, no capsular disruption, and TCCL <10 mm) had a lower risk factor for BCR+. Other early MRI semantic features are individually important but were not discriminatory in the statistical analysis.

On the other hand, patients with macroscopic extracapsular extension (mECE+) have a worse prognosis than those with pathologically confirmed extracapsular extension (pECE+). This means that when ECE is not visible on MRI, it is a favorable prognostic factor, even though it cannot guarantee the absence of microscopic pECE+. Moreover, recent literature has shown that local MRI staging is an independent risk factor for long-term oncologic outcomes, including BCR+, the development of metastatic disease, and prostate cancer-related mortality (15). The observation that MRI findings predictive of pECE+ indicate risk regardless of histological results might contribute to the ongoing refinement of clinical prostate cancer algorithms. By redefining risk groups using MRI findings instead of digital rectal examination (DRE) findings, better BCR-free survival can be achieved due to improved discrimination of non-organ-confined disease. This could have important implications for treatment planning and monitoring, although more information is needed regarding disease recurrence, PSA-specific mortality, and overall survival (OR).

In this study, only the GS > (4+3)/ISUP 4-5 were considered histological risk factors for BCR. It aligns with European guidelines (Mottet et al., 2021), which did not consider group grade 3 (GS 4+3) as a high-risk factor for BCR.

Although PSA was not identified as a predictive feature for pECE+ in the previous model (13), its value should be considered as a biomarker of poor prognosis for BCR before surgery. Elevated PSA levels are associated with more aggressive disease and indicate an increased risk for biochemical recurrence.

This study further underscores the importance of classic prognostic biomarkers such as pECE+, PSM, PSA, and high-risk ISUP in established prognostication tools following prostatectomy, as supported by previous research. (5,16–19). However, this model enables us to observe that even patients without these risk characteristics for BCR+, commonly referred to as low/intermediate-risk patients (pECE, GS < (4+4), can potentially benefit from pre-surgery MRI to evaluate adverse staging MRI-features (high TCCL and tumor size, smooth capsular bulging capsular disruption, capsular disruption and PI-RADS score). These MRI features confer a certain level of risk and should be considered when managing these patients.

The extrapolation of the timing of biochemical recurrence (BCR) and death in prostate cancer (PCa) is not well established. Previous studies have shown that longer times to BCR after radical prostatectomy (RP) are associated with a higher likelihood of localized disease and decreased PCa mortality (20). However, more recent studies have failed to find a consistent association between time to BCR and death from PCa (21). Various variables, such as Gleason score (GS), pathological stage, surgical margin status, and lymph node involvement, are related to BCR and should be considered to predict local or distant recurrence. Short PSA doubling time (mainly PSA-DT <6 months), GS ≥8 ng/ml, seminal vesicle invasion (SVI) (pT3b), and lymph node positivity appear to be the main factors associated with metastatic disease and PCa mortality. Therefore, stratifying men with PCa into risk groups is crucial for defining prognosis and treatment decisions (21).

It is important to acknowledge several limitations of our study. Firstly, we only analyzed the early outcome of BCR, and further analysis is needed to assess the model's influence on PCa disease progression and mortality. Our cohort was limited to a single institution and a single therapeutic approach (robot-assisted radical prostatectomy - RARP), which limits the generalizability of our findings to other management options such as radiation therapy (RT), focal therapy, or active surveillance. We did not evaluate the influence of seminal vesicle invasion (SVI) separately from extracapsular extension (pECE+) in our analysis. Additionally, we did not consider lymph node metastasis and the impact of adjuvant RT on post-surgical outcomes. The amount of positive surgical margins (PSM) was also not considered, although it varied between 1 cm and 1 mm, with a mean of less than 5 mm on pathology examination.

Further research is needed to understand better the prognostic significance of our predictive model in long-term disease progression-free survival and the influence of other neoadjuvant therapeutics used in cases of positive surgical margins immediately after prostatectomy.

5. Conclusions

This study suggests that in addition to the important role of pathologic tumor stage as a prognostic factor, the predictive MRI features for detecting extracapsular extension (ECE) before surgery also significantly impact early outcomes and should be taken into consideration in clinical decision-making. The presence of macroscopic ECE, tumor contact length (TCCL), capsular disruption, and a Gleason score (GS) of ≥8 ng/ml can be regarded as independent prognostic factors for early biochemical recurrence (BCR). It is particularly important to determine the adverse staging MRI-features in low/intermediate-risk patients (pECE-, GS< (4+4)) to identify individuals who require closer monitoring. By incorporating these factors into the clinical assessment, healthcare professionals can identify patients who may benefit from more intensive follow-up and potentially early intervention strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Flowchart of the patient selection process; Figure S2: Estimation of the survival curve for the biochemical recurrence-free survival (BCRFS) study: Kaplan-Meier survival function (relapse-free); number of patients at risk for every 250 days; The dashed lines represent the estimates for the survival curve at 365, 730, 1460 days. Figure S3: Estimation of the survival curves for the biochemical recurrence-free survival (BCRFS) study. Kaplan-Meier survival function (relapse-free) stratified by: pECE based on pathologic specimen staging (A), measurable ECE (B), Gleason score’s severity (C), Index Lesion PIRADS.V2 (D), capsular disruption (E), TCCL (F), surgical margins (G) and PSA (H); number of patients at risk for every 250 days; p-value from the two-tailed log-rank test to compare the two survival curves. The dashed lines represent the estimates for the survival curve at 365, 730, 1460 days; Table S1: Results from fitting a Cox proportional hazards regression model.

Author Contributions

A.G.: study design, data collection and analysis. Manuscript elaboration; F.C.A. and G.V.: data analysis, review and editing; K.M.: radical prostatectomy surgery of all patients; R.M.: supervision. H.M.: statistical analysis. All the authors read and agreed with the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by a PhD student scholarship (AG) from Luz Saúde Clinical Research and Innovation program, Award Number: ID LH.INV.F2019027. HM was funded by FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal, under the project UIDB/00006/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This current study is included in the PHD research project approved by scientific and ethics Committee of Nova Medical School, University and approved as research project ID LH.INV.F2019027, supported by institutional board, Learning Health, Hospital da Luz, Lisbon.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thanks Hospital da Luz for all the support that provided the elaboration of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cornford P, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, van den Broeck T, Cumberbatch MG, de Santis M, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer: Part II: 2020 update: treatment of relapsing and metastatic prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2021;79(2):263–82. [CrossRef]

- Cookson MS, Aus G, Burnett AL, Canby-Hagino ED, D’Amico A V., Dmochowski RR, et al. Variation in the definition of biochemical recurrence in patients treated for localized prostate cancer: the American Urological Association Prostate Guidelines for Localized Prostate Cancer Update Panel report and recommendations for a standard in the reporting of surgical outcomes. Journal of Urology. 2007;177(2):540–5. [CrossRef]

- Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Briers E, Cumberbatch MG, De Santis M, et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol. 2017;71(4):618–29.

- Mottet N, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Van den Broeck T, Cumberbatch MG, De Santis M, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer: 2020 update. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol. 2021;79(2):243–62.

- Punnen S, Cooperberg MR, D’Amico A V., Karakiewicz PI, Moul JW, Scher HI, et al. Management of biochemical recurrence after primary treatment of prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol. 2013;64(6):905–15. [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck T, van den Bergh RCN, Arfi N, Gross T, Moris L, Briers E, et al. Prognostic value of biochemical recurrence following treatment with curative intent for prostate cancer: a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2019;75(6):967–87. [CrossRef]

- Tilki D, Preisser F, Graefen M, Huland H, Pompe RS. External validation of the european association of urology biochemical recurrence risk groups to predict metastasis and mortality after radical prostatectomy in a European cohort. Eur Urol. 2019;75(6):896–900. [CrossRef]

- Watson MJ, George AK, Maruf M, Frye TP, Muthigi A, Kongnyuy M, et al. Risk stratification of prostate cancer: integrating multiparametric MRI, nomograms and biomarkers. Future Oncology. 2016 Nov;12(21):2417–30.

- Leyh-Bannurah SR, Kachanov M, Karakiewicz PI, Beyersdorff D, Pompe RS, Oh-Hohenhorst SJ, et al. Combined systematic versus stand-alone multiparametric MRI-guided targeted fusion biopsy: nomogram prediction of non-organ-confined prostate cancer. World J Urol. 2021;39(1):81–8. [CrossRef]

- Feng TS, Sharif-Afshar AR, Wu J, Li Q, Luthringer D, Saouaf R, et al. Multiparametric MRI improves accuracy of clinical nomograms for predicting extracapsular extension of prostate cancer. Urology. 2015;86(2):332–7.

- Hiremath A, Shiradkar R, Fu P, Mahran A, Rastinehad AR, Tewari A, et al. An integrated nomogram combining deep learning, Prostate Imaging–Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) scoring, and clinical variables for identification of clinically significant prostate cancer on biparametric MRI: a retrospective multicentre study. Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3(7):e445–54. [CrossRef]

- Li L, Shiradkar R, Leo P, Algohary A, Fu P, Tirumani SH, et al. A novel imaging based nomogram for predicting post-surgical biochemical recurrence and adverse pathology of prostate cancer from pre-operative bi-parametric MRI. EBioMedicine. 2021;63(December 2020):103163. [CrossRef]

- Guerra A, Alves FC, Maes K, Joniau S, Cassis J, Maio R, et al. Early biomarkers of extracapsular extension of prostate cancer using MRI-derived semantic features. Cancer Imaging. 2022 Dec 23;22(1):74.

- Weinreb JC, Barentsz JO, Choyke PL, Cornud F, Haider MA, Macura KJ, et al. PI-RADS Prostate Imaging: Reporting and Data System 2015: version 2. Eur Urol. 2016;69(1):16–40. [CrossRef]

- Wibmer AG, Nikolovski I, Chaim J, Lakhman Y, Lefkowitz RA, Sala E, et al. Local extent of prostate cancer at MRI versus prostatectomy histopathology: associations with long-term oncologic outcomes. Radiology. 2022;302(3):595–602. [CrossRef]

- Suardi N, Porter CR, Reuther AM, Walz J, Kodama K, Gibbons RP, et al. A nomogram predicting long-term biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Cancer [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2023 Mar 10];112(6):1254–63. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.2329. [CrossRef]

- Stephenson AJ, Scardino PT, Eastham JA, Bianco FJ, Dotan ZA, DiBlasio CJ, et al. Postoperative nomogram predicting the 10-Year probability of prostate cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(28):7005–12. [CrossRef]

- Lee W, Lim B, Kyung YS, Kim CS. Impact of positive surgical margin on biochemical recurrence in localized prostate cancer. Prostate Int. 2021;9(3):151–6. [CrossRef]

- Yang CW, Wang HH, Hassouna MF, Chand M, Huang WJS, Chung HJ. Prediction of a positive surgical margin and biochemical recurrence after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):14329. [CrossRef]

- Freedland SJ, Humphreys EB, Mangold LA, Eisenberger M, Dorey FJ, Walsh PC, et al. Risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality following biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2005;294(4):433. [CrossRef]

- Tourinho-Barbosa RR, Srougi V, Nunes-Silva I, Baghdadi M, Rembeyo G, Eiffel SS, et al. Biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy: What does it mean? International Braz J Urol. 2018;44(1):14–21.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).