Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of the Investigated Patient Population

2.2. Evaluation of Clinical, Pathological, and Follow-Up Factors

2.3. Model Description and Assumptions, Study Design, and Evaluation of Endpoints

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

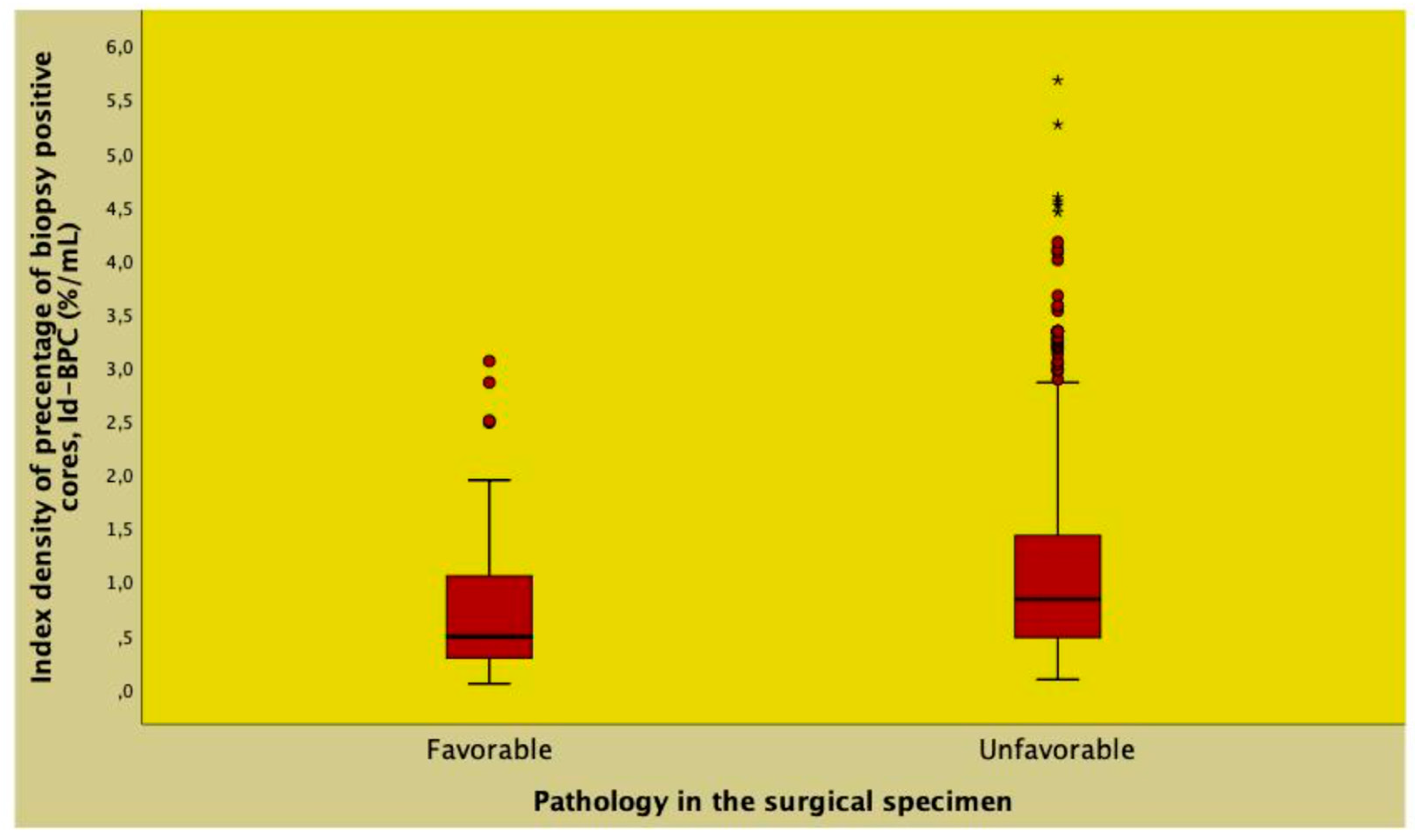

3.1. Patient Population Demographics and Risk of Unfavorable Pathology in the Surgical Specimen

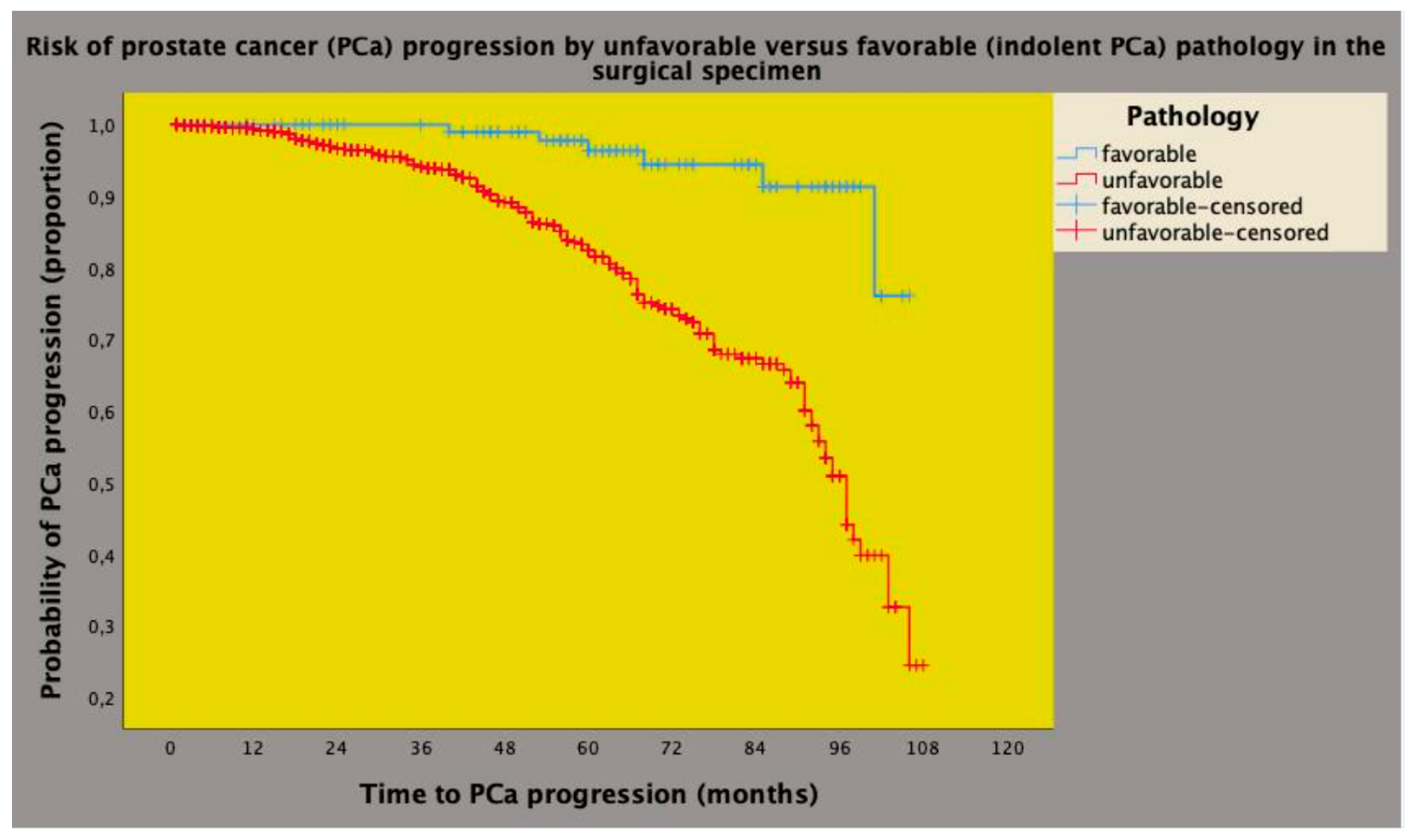

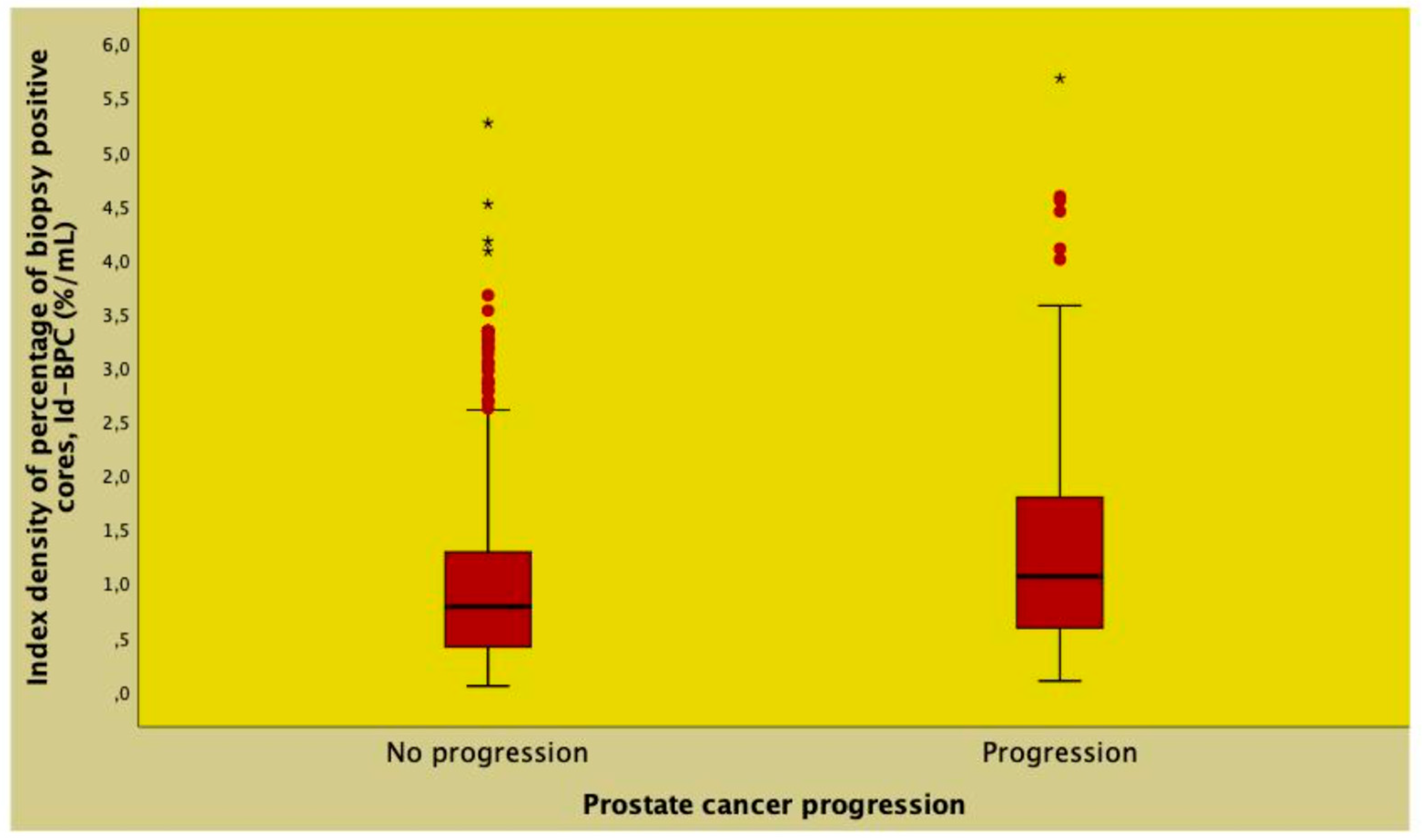

3.2. Clinical Risk Factors of Prostate Cancer Progression after Robotic Surgery

3.3. The Prognostic Impact of Id-BPC on PCa Progression after Predicting Unfavorable Pathology in the Surgical Specimen

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest Statement

Availability of Data and Materials

Abbreviations

| AS: active surveillance |

| ASA: Association of Anesthesiologists |

| BMI: body mass index |

| BPC: percentage of biopsy-positive cores |

| EAU: European Association of Urology |

| ECE: extracapsular extension |

| ePLND: extended pelvic lymph node dissection |

| IBF: interval to biochemical failure |

| Id-BPC: index density of percentage of biopsy-positive cores |

| IQR: interquartile ranges |

| ISUP: International Society of Urological Pathology |

| mpMRI: multiparametric resonance imaging |

| NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| PCa: prostate cancer |

| PLNI: pelvic lymph node invasion |

| PSAD: PSA density |

| PSA-DT: PSA doubling time |

| PV: prostate volume |

| RARP: robot-assisted radical prostatectomy |

| RP: radical prostatectomy |

| RT: radiation therapy |

| SVI: seminal vesicle invasion |

| TRUS: transrectal ultrasound |

| WW: watchful waiting |

References

- Mottet, N.; Cornford, P.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Briers, E.; Eberli, D.; De Santis, M.; Gillessen, S.; Grummet, J.; Henry, A.M.; et al.; Expert Patient Advocate (European Prostate Cancer Coalition/Europa UOMO) EAU - EANM - ESTRO - ESUR - ISUP - SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Available online: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Schaeffer, E.; Srinivas, S.; Adra, N.; An, Y.; Barocas, D.; Bitting, R.; Bryce, A.; Chapin, B.; Cheng, H.H.; D’Amico, A.V.; et al. Prostate Cancer, Version 4.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Antonelli, A.; Sodano, M.; Peroni, A.; Mittino, I.; Palumbo, C.; Furlan, M.; Carobbio, F.; Tardanico, R.; Fisogni, S.; Simeone, C. Positive Surgical Margins and Early Oncological Outcomes of Robotic vs Open Radical Prostatectomy at a Medium Case-Load Institution. Minerva Urology and Nephrology 2016, 69, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdy, F.C.; Donovan, J.L.; Lane, J.A.; Metcalfe, C.; Davis, M.; Turner, E.L.; Martin, R.M.; Young, G.J.; Walsh, E.I.; Bryant, R.J.; et al. Fifteen-Year Outcomes after Monitoring, Surgery, or Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallis, C.J.D.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, L.-C.; Penson, D.F.; Koyama, T.; Kaplan, S.H.; Greenfield, S.; Luckenbaugh, A.N.; Klaassen, Z.; Conwill, R.; et al. Association of Treatment Modality, Functional Outcomes, and Baseline Characteristics With Treatment-Related Regret Among Men With Localized Prostate Cancer. JAMA Oncol 2022, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oderda, M.; Diamand, R.; Albisinni, S.; Calleris, G.; Carbone, A.; Falcone, M.; Fiard, G.; Gandaglia, G.; Marquis, A.; Marra, G.; et al. Indications for and Complications of Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection in Prostate Cancer: Accuracy of Available Nomograms for the Prediction of Lymph Node Invasion. BJU Int 2021, 127, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, T.; Denisenko, A.; Mico, V.; McPartland, C.; Shah, Y.; Mark, J.R.; Lallas, C.D.; Fonshell, C.; Danella, J.; Jacobs, B.; et al. Multiparametric MRI Is Not Sufficient for Prostate Cancer Staging: A Single Institutional Experience Validated by a Multi-Institutional Regional Collaborative. Urol Oncol 2023, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briganti, A.; Larcher, A.; Abdollah, F.; Capitanio, U.; Gallina, A.; Suardi, N.; Bianchi, M.; Sun, M.; Freschi, M.; Salonia, A.; et al. Updated Nomogram Predicting Lymph Node Invasion in Patients with Prostate Cancer Undergoing Extended Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection: The Essential Importance of Percentage of Positive Cores. Eur Urol 2012, 61, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandaglia, G.; Ploussard, G.; Valerio, M.; Mattei, A.; Fiori, C.; Fossati, N.; Stabile, A.; Beauval, J.-B.; Malavaud, B.; Roumiguié, M.; et al. A Novel Nomogram to Identify Candidates for Extended Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection Among Patients with Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer Diagnosed with Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Targeted and Systematic Biopsies. Eur Urol 2019, 75, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, A.; Vismara Fugini, A.; Tardanico, R.; Giovanessi, L.; Zambolin, T.; Simeone, C. The Percentage of Core Involved by Cancer Is the Best Predictor of Insignificant Prostate Cancer, According to an Updated Definition (Tumor Volume up to 2.5 Cm3): Analysis of a Cohort of 210 Consecutive Patients with Low-Risk Disease. Urology 2014, 83, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebben, M.; Tafuri, A.; Shakir, A.; Pirozzi, M.; Processali, T.; Rizzetto, R.; Amigoni, N.; Tiso, L.; De Michele, M.; Panunzio, A.; et al. The Impact of Extended Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection on the Risk of Hospital Readmission within 180 Days after Robot Assisted Radical Prostatectomy. World J Urol 2020, 38, 2799–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcaro, A.B.; Rizzetto, R.; Bianchi, A.; Gallina, S.; Serafin, E.; Panunzio, A.; Tafuri, A.; Cerrato, C.; Migliorini, F.; Antoniolli, S.Z.; et al. American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status System Predicts the Risk of Postoperative Clavien–Dindo Complications Greater than One at 90 Days after Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy: Final Results of a Tertiary Referral Center. Journal of Robotic Surgery 2022, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanapragasam, V.J.; Bratt, O.; Muir, K.; Lee, L.S.; Huang, H.H.; Stattin, P.; Lophatananon, A. The Cambridge Prognostic Groups for Improved Prediction of Disease Mortality at Diagnosis in Primary Non-Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Validation Study. BMC Med 2018, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parry, M.G.; Cowling, T.E.; Sujenthiran, A.; Nossiter, J.; Berry, B.; Cathcart, P.; Aggarwal, A.; Payne, H.; Van Der Meulen, J.; Clarke, N.W.; et al. Risk Stratification for Prostate Cancer Management: Value of the Cambridge Prognostic Group Classification for Assessing Treatment Allocation. BMC Med 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, A.J.; Kattan, M.W.; Eastham, J.A.; Bianco, F.J.; Yossepowitch, O.; Vickers, A.J.; Klein, E.A.; Wood, D.P.; Scardino, P.T. Prostate Cancer–Specific Mortality After Radical Prostatectomy for Patients Treated in the Prostate-Specific Antigen Era. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2009, 27, 4300–4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Broeck, T.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Arfi, N.; Gross, T.; Moris, L.; Briers, E.; Cumberbatch, M.; De Santis, M.; Tilki, D.; Fanti, S.; et al. Prognostic Value of Biochemical Recurrence Following Treatment with Curative Intent for Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review. Eur Urol 2019, 75, 967–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilki, D.; Preisser, F.; Graefen, M.; Huland, H.; Pompe, R.S. External Validation of the European Association of Urology Biochemical Recurrence Risk Groups to Predict Metastasis and Mortality After Radical Prostatectomy in a European Cohort. Eur Urol 2019, 75, 896–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierorazio, P.M.; Walsh, P.C.; Partin, A.W.; Epstein, J.I. Prognostic Gleason Grade Grouping: Data Based on the Modified Gleason Scoring System. BJU Int 2013, 111, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magi-Galluzzi, C.; Evans, A.J.; Delahunt, B.; Epstein, J.I.; Griffiths, D.F.; van der Kwast, T.H.; Montironi, R.; Wheeler, T.M.; Srigley, J.R.; Egevad, L.L.; et al. International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Handling and Staging of Radical Prostatectomy Specimens. Working Group 3: Extraprostatic Extension, Lymphovascular Invasion and Locally Advanced Disease. Modern Pathology 2011, 24, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berney, D.M.; Wheeler, T.M.; Grignon, D.J.; Epstein, J.I.; Griffiths, D.F.; Humphrey, P.A.; van der Kwast, T.; Montironi, R.; Delahunt, B.; Egevad, L.; et al. International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Handling and Staging of Radical Prostatectomy Specimens. Working Group 4: Seminal Vesicles and Lymph Nodes. Modern Pathology 2011, 24, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, M.C.; Seong Whang, I.; Pantuck, A.; Ring, K.; Kaplan, S.A.; Olsson, C.A.; Cooner, W.H. Prostate Specific Antigen Density: A Means of Distinguishing Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy and Prostate Cancer. Journal of Urology 1992, 147, 815–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Colli, J.; El-Galley, R. A Simple Method for Estimating the Optimum Number of Prostate Biopsy Cores Needed to Maintain High Cancer Detection Rates While Minimizing Unnecessary Biopsy Sampling. J Endourol 2010, 24, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcaro, A.B.; Novella, G.; Molinari, A.; Terrin, A.; Minja, A.; De Marco, V.; Martignoni, G.; Brunelli, M.; Cerruto, M.A.; Curti, P.; et al. Prostate Volume Index and Chronic Inflammation of the Prostate Type IV with Respect to the Risk of Prostate Cancer. Urol Int 2015, 94, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porcaro, A.B.; Tafuri, A.; Sebben, M.; Novella, G.; Processali, T.; Pirozzi, M.; Amigoni, N.; Rizzetto, R.; Shakir, A.; Mariotto, A.; et al. Prostate Volume Index and Prostatic Chronic Inflammation Predicted Low Tumor Load in 945 Patients at Baseline Prostate Biopsy. World J Urol 2020, 38, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedland, S.J.; Wieder, J.A.; Jack, G.S.; Dorey, F.; deKernion, J.B.; Aronson, W.J. Improved Risk Stratification for Biochemical Recurrence after Radical Prostatectomy Using a Novel Risk Group System Based on Prostate Specific Antigen Density and Biopsy Gleason Score. J Urol 2002, 168, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedland, S.J.; Isaacs, W.B.; Platz, E.A.; Terris, M.K.; Aronson, W.J.; Amling, C.L.; Presti, J.C.; Kane, C.J. Prostate Size and Risk of High-Grade, Advanced Prostate Cancer and Biochemical Progression After Radical Prostatectomy: A Search Database Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2005, 23, 7546–7554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcaro, A.B.; Amigoni, N.; Tafuri, A.; Rizzetto, R.; Shakir, A.; Tiso, L.; Cerrato, C.; Lacola, V.; Zecchini Antoniolli, S.; Gozzo, A.; et al. Endogenous Testosterone as a Predictor of Prostate Growing Disorders in the Aging Male. Int Urol Nephrol 2021, 53, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Population | Favorable pathology | Unfavorable pathology | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 1047 | 117 (11.2) | 930 (88.8) | P-value |

| Age (years) | 65 (60 - 70) | 63 (58 - 68) | 65 (60 - 70) | 0.013 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.7 (23.9 - 28.1) | 25.6 (23.7 - 28.1) | 25.7 (23.9 - 28.1) | 0.939 |

| ASA 1 | 88 (8.4) | 13 (11.1) | 75 (8.1) | 0.136 |

| ASA 2 | 858 (82.0) | 98 (83.8) | 760 (81.7) | |

| ASA 3 | 101 (9.6) | 6 (5.1) | 95 (10.2) | |

| PV (mL) | 40 (30 - 50) | 42 (31.7-53) | 39 (30 - 50) | 0.020 |

| PSA (ng/mL) | 6.6 (5.0 - 9.1) | 6.1 (4.6 - 7.8) | 6.7 (5.0 - 9.3) | 0.013 |

| PSAD (ng/mL2) | 0.17 (0.11 - 0.25) | 0.13 (0.09 - 0.21) | 0.17 (0.12 - 0.26) | <0.0001 |

| BPC (%) | 31.2 (20 - 50) | 21.4 (14.2 - 35.7) | 33.3 (20 - 50) | <0.0001 |

| Id-BPC (%/mL) | 0.81 (0.43 - 1.37) | 0.48 (0.28 - 1.05) | 0.83 (0.47 - 1.42) | <0.0001 |

| ISUP 1 | 361 (34.5) | 98 (83.8) | 263 (28.3) | <0.0001 |

| ISUP 2/3 | 554 (52.9) | 19 (16.2) | 535 (57.5) | |

| ISUP 4/5 | 132 (12.6) | 0 (0.0) | 132 (14.2) | |

| cT1 | 600 (57.3) | 92 (78.6) | 508 (54.6) | <0.0001 |

| cT2/3 | 447 (42.7) | 25 (21.4) | 422 (45.4) | |

| cN0 | 990 (94.6) | 116 (99.1) | 874 (94) | 0.020 |

| cN1 | 57 (5.4) | 1 (0.9) | 56 (6) |

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistics | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Age (years) | 1.031 (1.005 - 1.059) | 0.021 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.004 (0.946 - 1.065) | 0.907 | ||

| ASA 1 | Ref | |||

| ASA 2 | 1.344 (0.719 - 2.512) | 0.354 | ||

| ASA 3 | 2.744 (0.996 - 7.562) | 0.051 | ||

| PV (mL) | 0.989 (0.980 - 0.998) | 0.023 | ||

| PSA (ng/mL) | 1.091 (1.031 - 1.154) | 0.002 | ||

| PSAD (ng/mL2) | 40.796 (5.760 - 288.950) | <0.0001 | 9.004 (1.120 - 72.385) | 0.039 |

| Id-BPC (%/mL) | 2.187 (1.541 - 3.103) | <0.0001 | 1.512 (1.029 - 2.221) | 0.035 |

| ISUP 1 | Ref | Ref | ||

| ISUP > 1 | 13.081 (7.482 - 21.819) | <0.0001 | 10.596 (6.306 - 17.806) | <0.0001 |

| cT1 | Ref | Ref | ||

| cT2/3 | 3.057 (1.929 - 4.845) | 1.904 (1.160 - 3.127) | 0.011 | |

| cN0 | Ref | |||

| cN1 | 7.432 (1.019 - 54.202) | 0.048 |

| No PCa progression | Pca progression | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 810 (77.4) | 237 (22.6) | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Age (years) | 65 (59.7 - 70.0) | 65 (61 - 70) | 1.032 (1.011 - 1.052) | 0.002 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.8 (23.9 - 28.1) | 25.6 (23.8 - 28.1) | 0.986 (0.947 - 1.027) | 0.502 | ||

| ASA 1 | 66 (8.1) | 22 (9.3) | Ref | |||

| ASA 2 | 668 (82.5) | 190 (80.2) | 0.876 (0.563 - 1.365) | 0.559 | ||

| ASA 3 | 76 (9.4) | 25 (10.5) | 1.336 (0.753 - 2.370) | 0.322 | ||

| PV (mL) | 40 (30 - 50) | 39 (30 - 50) | 1.005 (0.998 - 1.013) | 0.178 | ||

| PSA (ng/mL) | 6.3 (4.9 - 8.5) | 8 (5.4 - 12.5) | 1.038 (1.031 - 1.045) | <0.0001 | 1.027 (1.019 - 1.035) | <0.0001 |

| PSAD (ng/mL2) | 0.16 (0.11 - 0.23) | 0.21 (0.13 - 0.35) | 4.314 (3.198 - 5.820) | <0.0001 | ||

| Id-BPC (%/mL) | 0.74 (0.39 - 1.25) | 1.07 (0.57 - 1.81) | 1.468 (1.294 - 1.666) | <0.0001 | 1.561 (1.336 - 1.824) | <0.0001 |

| ISUP 1 | 308 (38) | 53 (22.3) | Ref | Ref | ||

| ISUP 2/3 | 432 (53.3) | 122 (51.5) | 2.785 (2.010 - 3.857) | <0.0001 | 2.618 (1.880 - 3.646) | <0.0001 |

| ISUP 4/5 | 70 (8.7) | 62 (26.2) | 6.658 (4.589 - 9.659) | <0.0001 | 4.709 (3.206 - 6.915) | <0.0001 |

| cT1 | 477 (58.9) | 123 (51.9) | Ref | Ref | ||

| cT2/3 | 333 (41.1) | 114 (48.1) | 2.131 (1.647 - 2.758) | <0.0001 | 1.549 (1.181 - 2.031) | 0.002 |

| cN0 | 775 (95.7) | 215 (90.7) | Ref | Ref | ||

| cN1 | 35 (4.3) | 22 (9.3) | 2.840 (1.824 - 4.421) | <0.0001 |

| Event occurrence | Id-BPC (%/mL) | BPC (%) |

|---|---|---|

| UNFAVOURABLE TUMOR PATHOLOGY | ||

| a) after adjusting for all clinical factors | ||

| OR (95% CI) | 1.566 (1.029 - 2.383) | 1.018 (1.006 - 1.031) |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| PROSTATE CANCER PROGRESSION | ||

| a) after adjusting for all clinical factors | ||

| HR (95% CI) | 1.587 (1.306 - 1.929) | 1.015 (1.008 - 1.021) |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| a) after adjusting for unfavorable pathology | ||

| HR (95% CI) | 1.365 (1.166 - 1.597) | 1.016 (1.010 - 1.022) |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).