1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) remains the second most frequently diagnosed malignancy and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related mortality in men worldwide [

1]. Its clinical course is highly variable, ranging from indolent tumors suitable for active surveillance to aggressive disease requiring immediate treatment. This heterogeneity highlights the need to accurately distinguish clinically significant prostate cancer (csPCa), usually defined as ISUP grade group ≥ 2, from low-risk disease that may not require immediate intervention. Overdiagnosis of insignificant cancer can lead to overtreatment, exposing patients to unnecessary risks and side effects [

2,

3].

Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) has become cornerstone in the diagnostic workup of PCa, enabling non-invasive detection, localization, and risk stratification of prostate lesions. mpMRI demonstrates high sensitivity for detecting csPCa, especially in lesions exceeding 10 mm in diameter, and has contributed to a paradigm shift in biopsy guidance strategies [

4]. When suspicion arises due to elevated prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels or an abnormal digital rectal examination (DRE), mpMRI is now a widely accepted next diagnostic step [

5,

6].

MRI-targeted biopsy (MRI-TB) —whether performed via cognitive guidance, MRI–ultrasound fusion software, or direct in-bore techniques— has been shown to improve the detection of csPCa and reduce the diagnosis of ISUP grade 1 cancers, thereby mitigating the risk of overtreatment when compared to conventional systematic biopsy (SB) [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Accordingly, both the American Urological Association (AUA) and European Association of Urology (EAU) recommend performing MRI-TB in patients with suspicious lesions on MRI, both in biopsy-naïve patients and in those with previous negative biopsies [

5,

6].

Despite the advantages of MRI-TB, the role of systematic biopsy (SB) remains contentious. While SB may increase the detection of insignificant cancers and lead to overtreatment [

11,

12], it may also uncover csPCa that is missed by targeted approaches [

7]. This has led to ongoing debate about the added value of combining MRI-TB with SB, especially in the context of imaging-guided precision medicine.

To address this controversy, we conducted a retrospective study at our institution where transperineal MRI–US fusion-guided biopsies are routinely performed combined with systematic sampling to ensure maximal detection of csPCa. In this study, we evaluated the diagnostic accuracy and histological outcomes of targeted biopsy, systematic biopsy, and their combination in detecting PCa and csPCa. We also examined the correlation between PI-RADS scores and biopsy results, providing insight into the real-world accuracy of mpMRI-guided diagnostics. Our findings aim to clarify the relative contributions of targeted and systematic biopsy approaches and inform clinical decision-making in prostate cancer diagnostics.

2. Materials and Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 356 patients who underwent transperineal MRI-TB and SB at our hospital between 2020 and 2023. Patients with an elevated PSA level or suspicious DRE and having at least one lesion Prostate Imaging-Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) score of ≥ 3 were included in the study. Lesions were detected using a 3 Tesla mpMRI according to the PI-RADS v2.1. Sequences included T2-weighted images, diffusion-weighted images, and dynamic contrast-enhanced images. Additionally, patients with previous negative biopsy or in active surveillance were also included. All lesions detected by MRI, were biopsied via the transperineal approach using the KOELIS MRI-US fusion platform (Koelis Trinity, Meyland, France). The systematic biopsies were performed with the transperineal approach in the same session, without avoiding the target lesions.

The following baseline and clinical characteristics were noted for all eligible: age, PSA, prostate volume (PV), PSA density (PSAD), number of lesions, MRI location of lesions, MRI size of lesions, and PI-RADS score of the lesions. The following histopathological data were collected: Gleason score and ISUP grade total of each lesion and separated by MRI-TB and SB.

For this study, csPCa was defined by the presence of Gleason score 3+4 (ISUP 2) or higher. The MRI-TB was performed using the Koelis system under sedation and outpatient regimen. SB was performed after MRI-TB.

Statistical analyses were performed to evaluate the diagnostic performance of MRI–US fusion-TB, SB, and the combination of both techniques for prostate cancer detection. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographics and lesion characteristics, including median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. The Wilcoxon rank sum test, Pearson’s chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test were used to check for statistical significance as appropriate.

For group comparisons, Pearson’s Chi-squared test was used to assess differences in detection rates of prostate cancer PCa and csPCa between TB and SB. Sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy of each biopsy approach were calculated using the combined result of TB and SB as the reference standard.

ISUP grade concordance between targeted and systematic biopsies was analyzed to determine the proportion of lesions with identical grades, upgrades (ISUP higher in TB), or downgrades (ISUP higher in SB). These were reported as absolute counts and percentages.

Subgroup analyses were performed by stratifying lesions according to clinical indication: patients under active surveillance (AS) and patients undergoing diagnostic biopsy. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All analyses were performed using R statistical software version 4.5.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, hhtps://

www.R-project.org).

3. Results

A total of 356 patients underwent MRI–US fusion-targeted biopsy (TB) and systematic biopsy (SB), with a combined total of 452 lesions analyzed. The baseline clinical and imaging characteristics of the 452 lesions are summarized in

Table 1.

3.1. Study Cohort Characteristics

The median age of the overall population was 68 years (IQR: 62–74). PSA density had a median value of 0.11 ng/mL/cm3 (IQR: 0.07–0.17), and serum PSA levels had a median of 6.1 ng/mL (IQR: 4.6–8.4). Age, PSA, and PSA density did not differ significantly between patients under active surveillance and those undergoing initial biopsy (all p > 0.05).

In the overall cohort, 290 lesions (64%) were from patients with only one suspicious lesion, while 162 lesions (36%) were from patients with two lesions on MRI.

Regarding prior biopsy status, 255 lesions (56%) came from patients without previous biopsy, and 108 lesions (24%) were from patients with a prior negative biopsy. Notably, 89 lesions (20%) were from patients on active surveillance, all of whom had previously confirmed PCa.

In terms of lesion risk stratification by PI-RADS score:

PI-RADS 3: 88 lesions (20%);

PI-RADS 4: 309 lesions (68%);

PI-RADS 5: 55 lesions (12%).

There were no significant differences in PI-RADS distribution between patients under surveillance and the rest of the cohort (p = 0.7).

Transitional/central zone: 115 lesions (25%).

No statistically significant differences were observed between groups in terms of lesion simplified location (p = 0.5).

Of the 452 lesions analyzed, 323 (71%) were diagnosed as prostate cancer (PCa). Among these, 223 lesions (49%) were classified as clinically significant PCa (csPCa), defined as ISUP grade ≥ 2, while 100 lesions (22%) were non-clinically significant (ISUP 1). The remaining 129 lesions (29%) were benign.

When stratified by clinical context, lesions from patients under active surveillance had a higher overall cancer detection rate, with 82 of 89 lesions (92%) showing PCa, compared to 66% (241/363) in patients undergoing initial or repeat diagnostic biopsy (p < 0.001). However, the proportion of csPCa among positive cases was similar between groups: 65% (53/82) in the AS group and 71% (170/241) in the diagnostic group (p = 0.3). These findings suggest that despite prior cancer diagnosis, a substantial proportion of active surveillance patients harbor csPCa at re-biopsy, supporting the continued role of combined biopsy techniques in this subgroup.

3.2. Cancer Detection Rates of Targeted and Systematic Biopsies

Targeted biopsy detected PCa in 286 of 452 lesions (63%), while systematic biopsy identified PCa in 260 of 452 lesions (58%). Although TB had a slightly higher detection rate, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.077).

For csPCa, TB detected 191 lesions (42%), significantly more than the 151 lesions (33%) identified by SB (

p = 0.023), indicating greater efficacy of the targeted approach in detecting clinically relevant disease (

Table 2).

3.2.1. Diagnostic Performance

The diagnostic performance of each biopsy technique for detecting csPCa was evaluated using the combined result of both targeted and systematic biopsy as the reference standard. As shown in

Table 3, targeted biopsy demonstrated a sensitivity of 93.7%, a specificity of 66.4%, and an overall accuracy of 79.9%. In comparison, systematic biopsy yielded a sensitivity of 85.7%, a specificity of 69.9%, and an accuracy of 77.6%. These results highlight the higher sensitivity and overall diagnostic accuracy of targeted biopsy, while systematic biopsy provided marginally higher specificity.

3.2.2. Additional Value of Systematic Biopsy

While MRI–US fusion-targeted biopsy demonstrated superior sensitivity and clinically significant cancer detection overall, systematic biopsy still provided relevant diagnostic benefit. Among all lesions, 37 (8.2%) were diagnosed exclusively by systematic biopsy and would have been missed had only targeted sampling been performed.

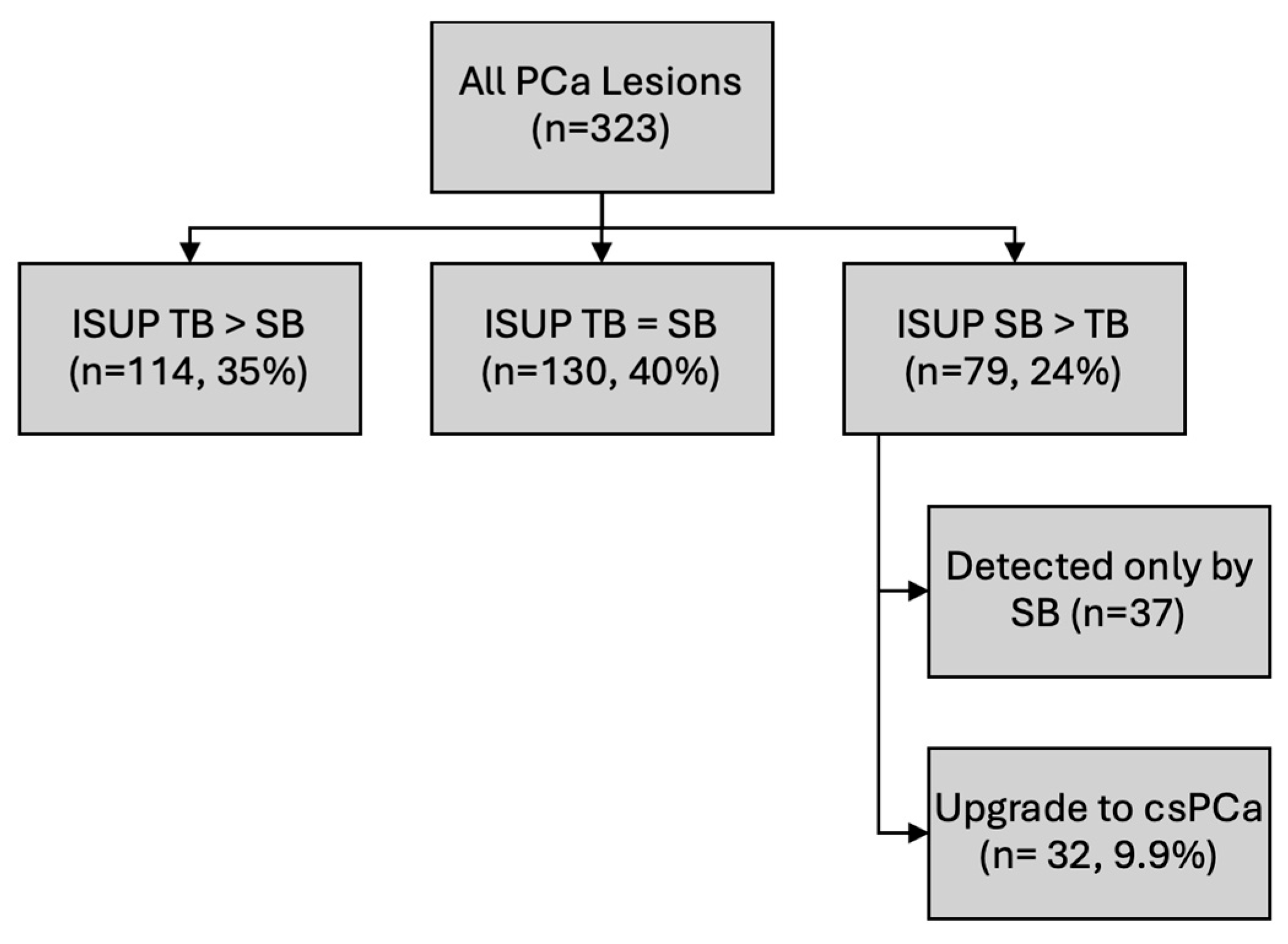

Moreover, ISUP grade comparison between biopsy methods revealed that in 79 lesions (24%), the ISUP grade was higher on systematic biopsy than on targeted biopsy. Importantly, 32 lesions (9.9%) were classified as csPCa, indicating the role of systematic biopsy in detecting not only additional cancers, but also tumors of higher prognostic relevance that may alter clinical management (

Figure 1).

3.3. Correlation Between PI-RADS Score and Detection of Clinically Significant Cancer

A statistically significant correlation was found between the PI-RADS score on mpMRI and the likelihood of detecting clinically significant prostate cancer (csPCa) (

p < 0.001). Among the 88 lesions scored as PI-RADS 3, csPCa was identified in 23% (20/88). This rate increased markedly for PI-RADS 4 lesions, with 53% (163/309) harboring csPCa, and was highest among PI-RADS 5 lesions, where 73% (40/55) were clinically significant. These findings confirm the strong predictive value of the PI-RADS classification system for stratifying cancer risk and guiding biopsy decisions. Diagnostic accuracy of mpMRI is shown in

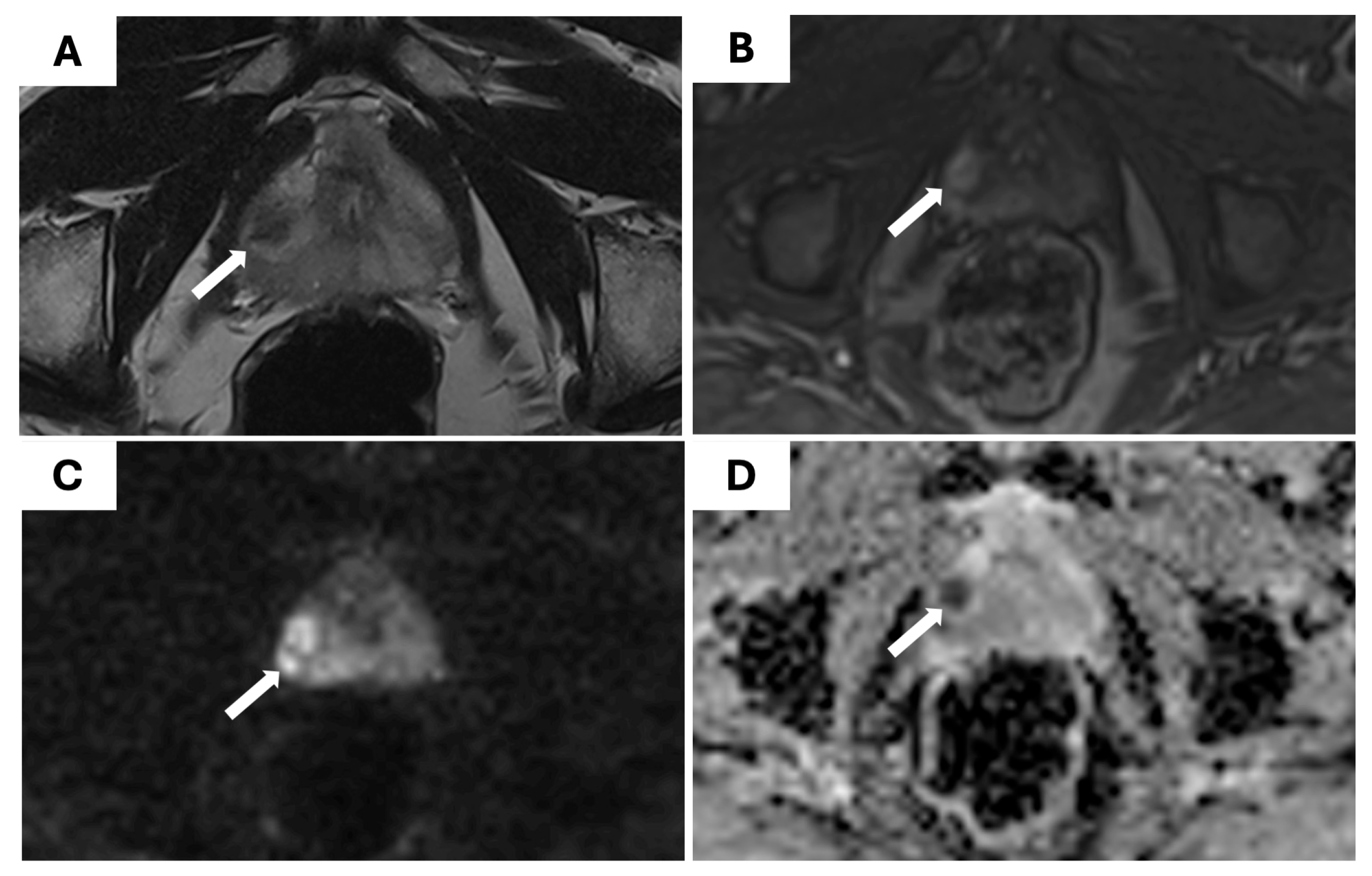

Table 4. An example of a PI-RADS 4 lesion detected on mpMRI and confirmed as csPCa on biopsy is shown in

Figure 2.

4. Discussion

The integration of mpMRI into the diagnostic pathway for PCa has significantly improved the detection of csPCa while reducing the overdiagnosis of indolent disease [

4,

7,

10,

13]. Our findings support this paradigm shift, demonstrating that MRI–US fusion-guided TB outperforms SB in detecting csPCa, with a sensitivity of 93.7% versus 85.7%, and an overall accuracy of 79.9% versus 77.6% respectively. These results align with previous meta-analyses and randomized trials, including the PRECISION and PROMIS studies [

10,

14], which showed that MRI-TB improves csPCa detection and reduces the diagnosis of ISUP grade 1 cancers.

Despite the superior performance of TB, SB continues to play a complementary role. In our cohort, 8.2% of csPCa cases were detected exclusively by SB, and 9.9% of lesions were upgraded in ISUP grade by SB compared to TB. These findings are in line with previous studies, which emphasize that SB can identify significant lesions missed by TB, particularly in multifocal or anterior lesions [

9,

12,

15,

16,

17,

18]. The European Association of Urology (EAU) and American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines continue to recommend combined biopsy approaches in certain clinical contexts [

5,

6].

The correlation between PI-RADS scores and csPCa detection observed in our study further validates the predictive value of mpMRI. The detection rate of csPCa increased from 23% in PI-RADS 3 lesions to 73% in PI-RADS 5 lesions, mirroring trends reported in earlier prospective studies [

8,

19]. This supports the use of mpMRI not only for lesion localization but also for risk stratification and biopsy decision-making [

20,

21]. Nonetheless, csPCa was still present in a notable proportion of PI-RADS 3 lesions (23%), highlighting that mpMRI is not infallible and that systematic sampling retains diagnostic value in patients with low-to-intermediate imaging scores, particularly when PSA density is elevated [

11,

20,

21].

Our inclusion of patients under AS adds valuable insight into this subgroup. Notably, 65% of AS patients with positive biopsies harbored csPCa, underscoring the importance of continued monitoring and the potential role of mpMRI and combined biopsy in re-evaluation. These findings align with current EAU and AUA guidelines, which recommend mpMRI in AS protocols to guide re-biopsy decisions [

5,

6].

The transperineal approach used in our study offers additional advantages, including reduced infection risk and improved access to anterior lesions, as supported by recent literature [

22,

23]. Moreover, the use of MRI–US fusion software enhances targeting precision, although inter-reader variability and operator experience remain challenges [

24,

25].

Beyond diagnostic performance, MRI-targeted strategies have also been associated with fewer biopsy cores and complications, contributing to more patient-centered and cost-effective care [

13,

15]. Future diagnostic algorithms may benefit from integrating mpMRI findings with clinical risk factors such as PSA density and lesion location to personalize the use of SB and reduce unnecessary sampling without compromising cancer detection [

5,

11,

13].

This study has several limitations. First, the analysis was conducted on a lesion-based level, which may lead to an overrepresentation of cancer detection when compared to patient-based analyses. There is an inherent asymmetry when comparing detection rates per lesion for TB and SB. While TB is performed for each MRI-identified lesion, SB is conducted once per patient. In cases with multiple lesions, this may lead to an overestimation of TB performance at the lesion level. This methodological difference should be taken into account when interpreting lesion-based comparisons. Second, targeted biopsy was always performed before systematic biopsy, which may have introduced a subtle operator bias. While systematic cores were obtained independently, the awareness of lesion location following TB may have unintentionally influenced sampling during SB, potentially increasing its detection yield. However, this reflects a real-world workflow used in many institutions.

5. Conclusions

MRI–US fusion-guided targeted biopsy significantly improves the detection of clinically significant prostate cancer compared to systematic biopsy alone. However, systematic biopsy continues to provide complementary diagnostic value, identifying additional csPCa cases and upgrading tumor grades in a meaningful subset of patients. The combination of both techniques offers the most comprehensive diagnostic yield, particularly in biopsy-naïve patients and those under active surveillance.

The strong association between PI-RADS score and csPCa detection supports mpMRI as a reliable triage tool. Nevertheless, the residual risk of missed disease, variability in imaging interpretation, and limitations of targeted sampling highlight the importance of maintaining a combined diagnostic approach, especially in equivocal cases.

Incorporating mpMRI and MRI–US fusion-guided biopsy into routine clinical practice represents a paradigm shift toward precision diagnostics in prostate cancer. Future prospective studies should evaluate long-term oncologic outcomes associated with different biopsy strategies and help define which patient subgroups may safely forgo systematic sampling without compromising diagnostic accuracy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.R., M.C., I.A., M.M. and C.N.; methodology, V.R., M.C., I.A., J.P., M.C.C. and C.N.; software, M.C.C and J.P.; validation, V.R., M.C., I.A., R.S. and C.N.; formal analysis, M.C.C; investigation, V.R., M.C., M.M., I.A., J.P., M.C.C., R.S., L.R.C., B.S. and C.N; resources, V.R., M.C., M.M., I.A., J.P., M.C.C., R.S., L.R.C., B.S. and C.N; data curation, J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, V.R.; writing—review and editing, V.R., M.C., I.A., C.N.; visualization, V.R., M.M., and C.N.; supervision, C.N.; project administration, C.N.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it was a retrospective analysis of anonymized data collected as part of routine clinical care. No intervention outside standard diagnostic practice was performed, and patient identifiers were removed prior to analysis. According to institutional and national guidelines, studies using fully anonymized retrospective data without direct patient involvement are exempt from formal ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because this was a retrospective study using anonymized data obtained from standard clinical procedures. No identifiable patient information was collected or reported, and the study posed no additional risk to participants. According to institutional policy and applicable national regulations, informed consent is not required for research involving fully anonymized retrospective data.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. Access to anonymized datasets may be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request and pending institutional approval.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare no acknowledgements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PCa |

Prostate Cancer |

| csPCa |

Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer |

| ISUP |

International Society of Urological Pathology |

| mpMRI |

Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| PSA |

Prostate-Specific Antigen |

| DRE |

Digital Rectal Examination |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MRI-TB |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Targeted Biopsy |

| SB |

Systematic Biopsy |

| EAU |

European Association of Urology |

| AUA |

American Urological Association |

| MRI–US |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Ultrasound |

| TB |

Targeted Biopsy |

| PV |

Prostate Volume |

| PSAD |

PSA Density |

| PI-RADS |

Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| AS |

Active Surveillance |

| TRUS |

Transrectal Ultrasound |

References

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024 May;74(3):229–63.

- Bell KJL, Del Mar C, Wright G, Dickinson J, Glasziou P. Prevalence of incidental prostate cancer: A systematic review of autopsy studies. Int J Cancer. 2015 Oct 1;137(7):1749–57.

- Moyer VA. Screening for Prostate Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 2012 Jul 17;((2)):120–34. Available from: https://annals.org.

- Drost FJH, Osses DF, Nieboer D, Steyerberg EW, Bangma CH, Roobol MJ, et al. Prostate MRI, with or without MRI-targeted biopsy, and systematic biopsy for detecting prostate cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 Apr 25;2019(4).

- Cornford P, Tilki D, van den Bergh RCN, Eberli D, De Meerleer G,, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG-Guidelines-on-Prostate-Cancer-2025. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer: Limited update March 2025 European Association of Urology. 2025.

- Wei JT, Barocas D, Carlsson S, Coakley F, Eggener S, Etzioni R, et al. Early Detection of Prostate Cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline Part II: Considerations for a Prostate Biopsy. Journal of Urology. 2023 Jul 1;210(1):54–63. [CrossRef]

- Kasivisvanathan V, Stabile A, Neves JB, Giganti F, Valerio M, Shanmugabavan Y, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging-targeted Biopsy Versus Systematic Biopsy in the Detection of Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis(Figure presented.). Vol. 76, European Urology. Elsevier B.V.; 2019. p. 284–303. [CrossRef]

- Bratan F, Niaf E, Melodelima C, Chesnais AL, Souchon R, Mège-Lechevallier F, et al. Influence of imaging and histological factors on prostate cancer detection and localisation on multiparametric MRI: A prospective study. Eur Radiol. 2013 Jul;23(7):2019–29. [CrossRef]

- Exterkate L, Wegelin O, Barentsz JO, van der Leest MG, Kummer JA, Vreuls W, et al. Is There Still a Need for Repeated Systematic Biopsies in Patients with Previous Negative Biopsies in the Era of Magnetic Resonance Imaging-targeted Biopsies of the Prostate? Eur Urol Oncol. 2020 Apr 1;3(2):216–23.

- Kasivisvanathan V, Rannikko AS, Borghi M, Panebianco V, Mynderse LA, Vaarala MH, et al. MRI-Targeted or Standard Biopsy for Prostate-Cancer Diagnosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018 May 10;378(19):1767–77. [CrossRef]

- Padhani AR, Barentsz J, Villeirs G, Rosenkrantz AB, Margolis DJ, Turkbey B, et al. PI-RADS Steering Committee: The PI-RADS Multiparametric MRI and MRI-directed Biopsy Pathway. Radiology. 2019;292(2):464–74. [CrossRef]

- Stranne J, Mottet N, Rouvière O. Systematic Biopsies as a Complement to Magnetic Resonance Imaging–targeted Biopsies: “To Be or Not To Be”? Vol. 83, European Urology. Elsevier B.V.; 2023. p. 381–4.

- Stabile A, Dell’Oglio P, Gandaglia G, Fossati N, Brembilla G, Cristel G, et al. Not All Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging–targeted Biopsies Are Equal: The Impact of the Type of Approach and Operator Expertise on the Detection of Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol Oncol. 2018 Jun 1;1(2):120–8.

- Ahmed HU, El-Shater Bosaily A, Brown LC, Gabe R, Kaplan R, Parmar MK, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of multi-parametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate cancer (PROMIS): a paired validating confirmatory study. The Lancet. 2017 Feb 25;389(10071):815–22. [CrossRef]

- Schoots IG, Roobol MJ, Nieboer D, Bangma CH, Steyerberg EW, Hunink MGM. Magnetic Resonance Imaging-targeted Biopsy May Enhance the Diagnostic Accuracy of Significant Prostate Cancer Detection Compared to Standard Transrectal Ultrasound-guided Biopsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Vol. 68, European Urology. Elsevier B.V.; 2015. p. 438–50. [CrossRef]

- Valerio M, Donaldson I, Emberton M, Ehdaie B, Hadaschik BA, Marks LS, et al. Detection of clinically significant prostate cancer using magnetic resonance imaging-ultrasound fusion targeted biopsy: A systematic review. Vol. 68, European Urology. Elsevier B.V.; 2015. p. 8–19.

- Takahashi T, Nakashima M, Maruno K, Hazama T, Yamada Y, Kikkawa K, et al. Comparative Evaluation of Detection Rates for Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer Using MRI-Targeted Biopsy Alone Versus in Combination With Systematic Biopsies: Development of a Risk-Stratification Scoring System. Prostate. 2024 Feb 1. [CrossRef]

- Malewski W, Milecki T, Tayara O, Poletajew S, Kryst P, Tokarczyk A, et al. Role of Systematic Biopsy in the Era of Targeted Biopsy: A Review. Current Oncology. 2024 Sep 3;31(9):5171–94. [CrossRef]

- Weinreb JC, Barentsz JO, Choyke PL, Cornud F, Haider MA, Macura KJ, et al. PI-RADS Prostate Imaging - Reporting and Data System: 2015, Version 2. Eur Urol. 2016 Jan 1;69(1):16–40.

- Wei C, Szewczyk-Bieda M, Bates AS, Donnan PT, Rauchhaus P, Gandy S, et al. Multicenter Randomized Trial Assessing MRI and Image-guided Biopsy for Suspected Prostate Cancer: The MULTIPROS Study. Radiology. 2023 Jul 1;308(1). [CrossRef]

- Riskin-Jones HH, Raman AG, Kulkarni R, Arnold CW, Sisk A, Felker E, et al. Performance of MR fusion biopsy, systematic biopsy and combined biopsy on prostate cancer detection rate in 1229 patients stratified by PI-RADSv2 score on 3T multi-parametric MRI. Abdominal Radiology. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Murphy DG, Grummet JP. Planning for the post-antibiotic era-why we must avoid TRUS-guided biopsy sampling. Vol. 13, Nature Reviews Urology. Nature Publishing Group; 2016. p. 559–60. [CrossRef]

- Grummet J, Pepdjonovic L, Huang S, Anderson E, Hadaschik B. Transperineal vs. transrectal biopsy in MRI targeting. Vol. 6, Translational Andrology and Urology. AME Publishing Company; 2017. p. 368–75. [CrossRef]

- Stabile A, Giganti F, Rosenkrantz AB, Taneja SS, Villeirs G, Gill IS, et al. Multiparametric MRI for prostate cancer diagnosis: current status and future directions. Vol. 17, Nature Reviews Urology. Nature Research; 2020. p. 41–61. [CrossRef]

- Yu LP, Du YQ, Sun YR, Qin CP, Yang WB, Huang ZX, et al. Value of cognitive fusion targeted and standard systematic transrectal prostate biopsy for prostate cancer diagnosis. Asian J Androl. 2024;26(5):479–83. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).