1. Introduction

Addition of androgen receptor-targeted agents (ARTA) to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) has significantly improved the prognosis of metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC) compared to ADT alone [

1,

2,

3].

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) concentration is considered an important prognostic marker, with rapid and large reductions associated with a favorable outcome and prolonged survival. A post-hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial (TITAN study) involving 1,052 patients with mHSPC, demonstrated that achieving a PSA decline to ≤0.2 ng/mL was associated with improved clinical outcomes [

4]. Specifically, patients who reached a low PSA level had significantly longer overall survival (OS), radiographic progression-free survival (rPFS), time to PSA progression, and time to castration resistance compared to those who did not achieve such a decline. Notably, a PSA level ≤0.02 ng/mL (UL2) was particularly predictive of favorable outcomes.

A real-world multi-center study involving 193 patients demonstrated that achieving ultralow PSA levels (<0.02 ng/mL) was associated with markedly improved outcomes [

5]. Specifically, the 18-month overall survival (OS) rate was 100% for patients with UL PSA levels, compared to 94.4% for those with PSA levels between 0.02–0.2 ng/mL, and 67.7% for those with PSA >0.2 ng/mL. Similarly, the radiographic progression-free survival (rPFS) rate at 18 months was 100% in the UL PSA group, compared to 93.5% and 50.7% in the other two groups, respectively. Multivariate analysis confirmed that ultralow PSA levels were independently associated with both OS (hazard ratio [HR] 0.164, p=0.0027) and rPFS (HR 0.089, p<0.0001).

In a retrospective study of 129 patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) treated with enzalutamide, achieving a PSA decline of ≥50% was associated with improved overall survival [

6]. Specifically, patients receiving enzalutamide had a median OS of 7.8 months supporting the prognostic value of PSA declines in heavily treated patients.

We conducted a single institution and tertiary cancer center retrospective analysis of mHSPC patients undergoing active treatment between December 2022 and August 2025. This study aimed to assess the association between the PSA levels and survival in mHSPC patients undergoing active treatment with ADT plus ARTA or triplet therapy (with abiraterone or darolutamide). Also, other factors were analyzed in order to establish variables associated with final outcome. Furthermore, additional effort was done in order to determine factors associated with UL PSA occurrence.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was approved by Ethical Committee of University Hospital Dubrava. Follow-up intervals were calculated in months from the date of first treatment at our institution (Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GhRH) agonist therapy or bilateral orchiectomy) to the date of the last follow-up/death from any cause (OS) or signs of radiographic progression (rPFS). Patient monitoring was concluded on August 1, 2025. PSA levels were stratified by the following ranges: ultralow (UL) PSA (<0.2 ng/mL), and non UL PSA >0.2 ng/mL. Due to relatively small numbers no additional stratification between UL2 PSA (<0.02 ng/mL) and UL1 PSA (0.02–0.2 ng/mL) was done and both ranges were included within UL PSA group. Diagnosis of metastatic disease was determined by CT and bone scans or positron emission tomography (PET) scans. There were no strict criteria regarding radiographic assessment after treatment initiation, however patients experiencing PSA decline received CT scans within one year from the start of the treatment. In cases of symptomatic disease and/or PSA rise, assessment was done within a six-week period. Treatment with ARTA started within one month from ADT initiation/bilateral orchiectomy in all patients. The chi- squared test was used to assess the relationship of PSA status (UL PSA vs non UL PSA) with other clinical variables stratified at median or in their respective categories. The logistic regression was used to assess independent predictors of UL PSA status. Survival analysis was based on the Kaplan-Meier method. The Cox regression analysis was used to assess independent predictors of time-to-event outcomes. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were done using MedCalc version 23.2.1 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium).

3. Results

In 32-month period, 80 patients with mHSPC were treated at Division of Oncology and Radiotherapy University Hospital Dubrava. After excluding patient with inadequate follow-up period (<6 months, n=9) 71 patients were available for further analysis.

Baseline characteristics of the patients are summarized in

Table 1.

A total of 42 (59.2%) of our cohort achieved UL PSA levels, while 29 patients (40.8%) had PSA levels > 0.2 ng/mL. Median age was 71 years (range 49–94 years) and most of the patients presented with de novo metastatic disease (67.6%, n=48). Enzalutamide was the most common ARTA treatment used in our patients (n=46, 64.8%), followed by triplet (n=11, 15.5%), apalutamide (n=7, 9.8%) and abiraterone (n=7, 9.8%). A total of 64.8% of our cohort of patients had a Gleason score 8 or more. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRh) was the most common treatment backbone in order to achieve androgen deprivation (60.6%, n=43) while 28 (39.4%) patients underwent bilateral orchiectomy.

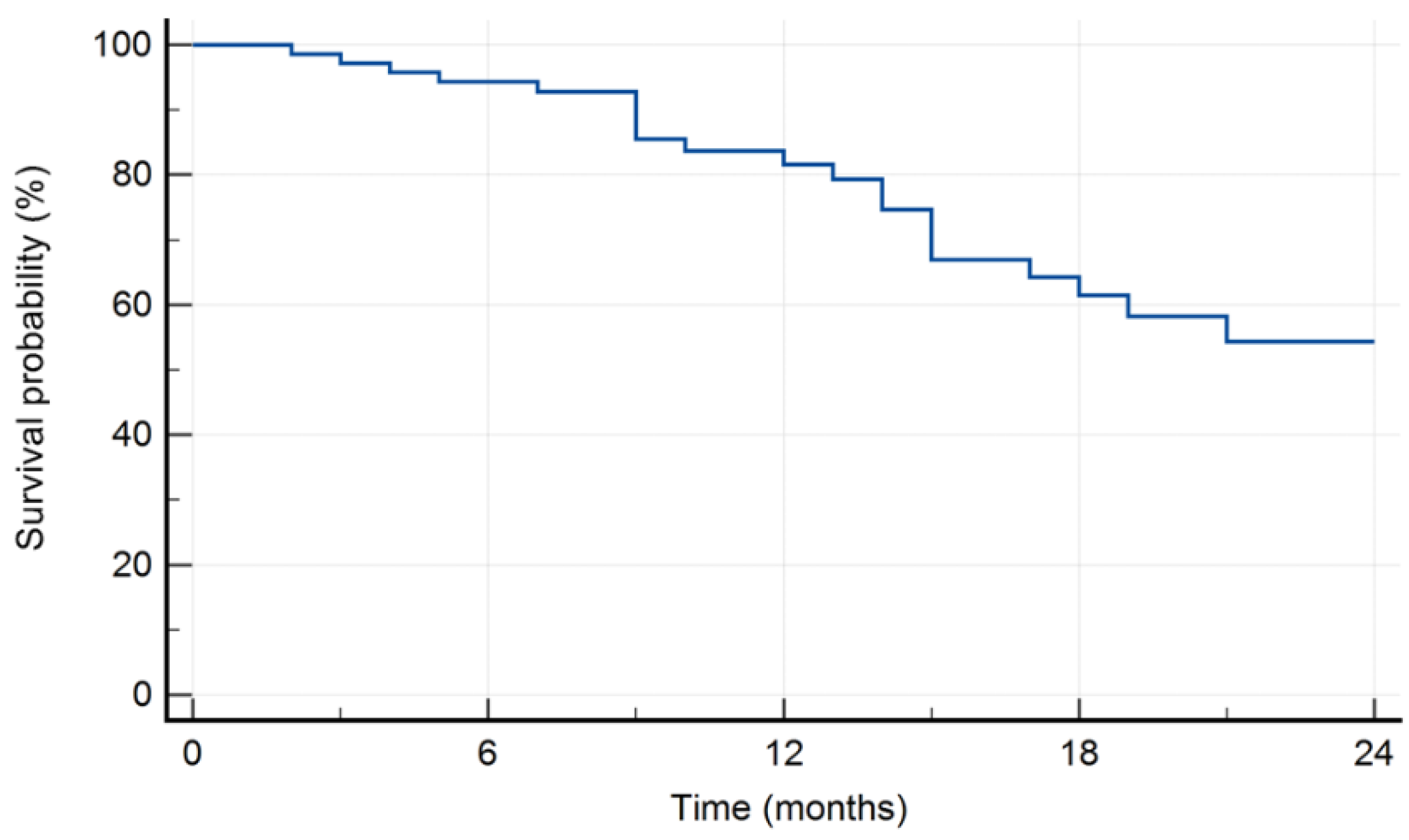

The 18-month survival rate was 61.5% (

Figure 1).

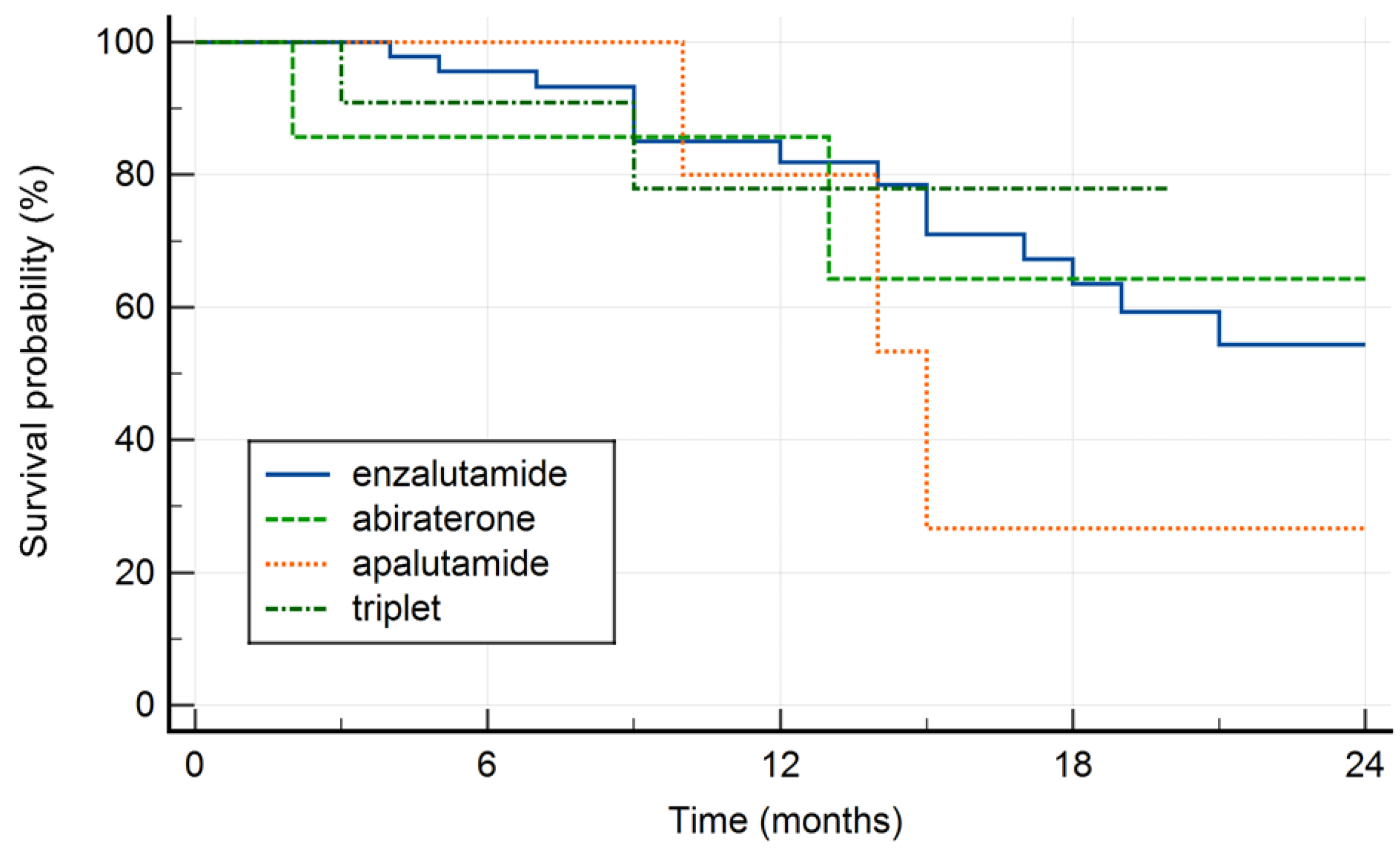

Survival by treatment type is shown in Figure 2. There was no significant difference in final outcome with respect to treatment modality (p=0.845).

Cox regression analysis identified age >71 years at the diagnosis of mHSPC and UL PSA levels as statistically significant factors associated with favorable outcome (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate predictors of survival.

Table 2.

Multivariate predictors of survival.

| Covariate |

b |

SE |

Wald |

P |

Exp(b) |

95% CI of Exp(b) |

| Years (median) |

-1.1862 |

0.5441 |

4.7535 |

0.0292 |

0.3054 |

0.1051 to 0.8871 |

| Gleason score ( <7 vs ≥8) |

0.5754 |

0.5229 |

1.2107 |

0.2712 |

1.7778 |

0.6379 to 4.9548 |

| iPSA_(median) |

0.4588 |

0.6868 |

0.4463 |

0.5041 |

1.5822 |

0.4118 to 6.0798 |

| GhRh vs bilateral orchiectomy |

0.04711 |

0.5084 |

0.008587 |

0.9262 |

1.0482 |

0.3870 to 2.8394 |

Metastases timing (synchronous vs

metachronous |

-0.8239 |

0.7818 |

1.1105 |

0.2920 |

0.4387 |

0.0948 to 2.0309 |

| Disease volume (low vs high) |

-0.8760 |

0.7128 |

1.5105 |

0.2191 |

0.4164 |

0.1030 to 1.6838 |

| Treatment type |

-0.06679 |

0.2148 |

0.09666 |

0.7559 |

0.9354 |

0.6139 to 1.4252 |

| UL PSA |

-1.8335 |

0.5425 |

11.4238 |

0.0007 |

0.1599 |

0.0552 to 0.4629 |

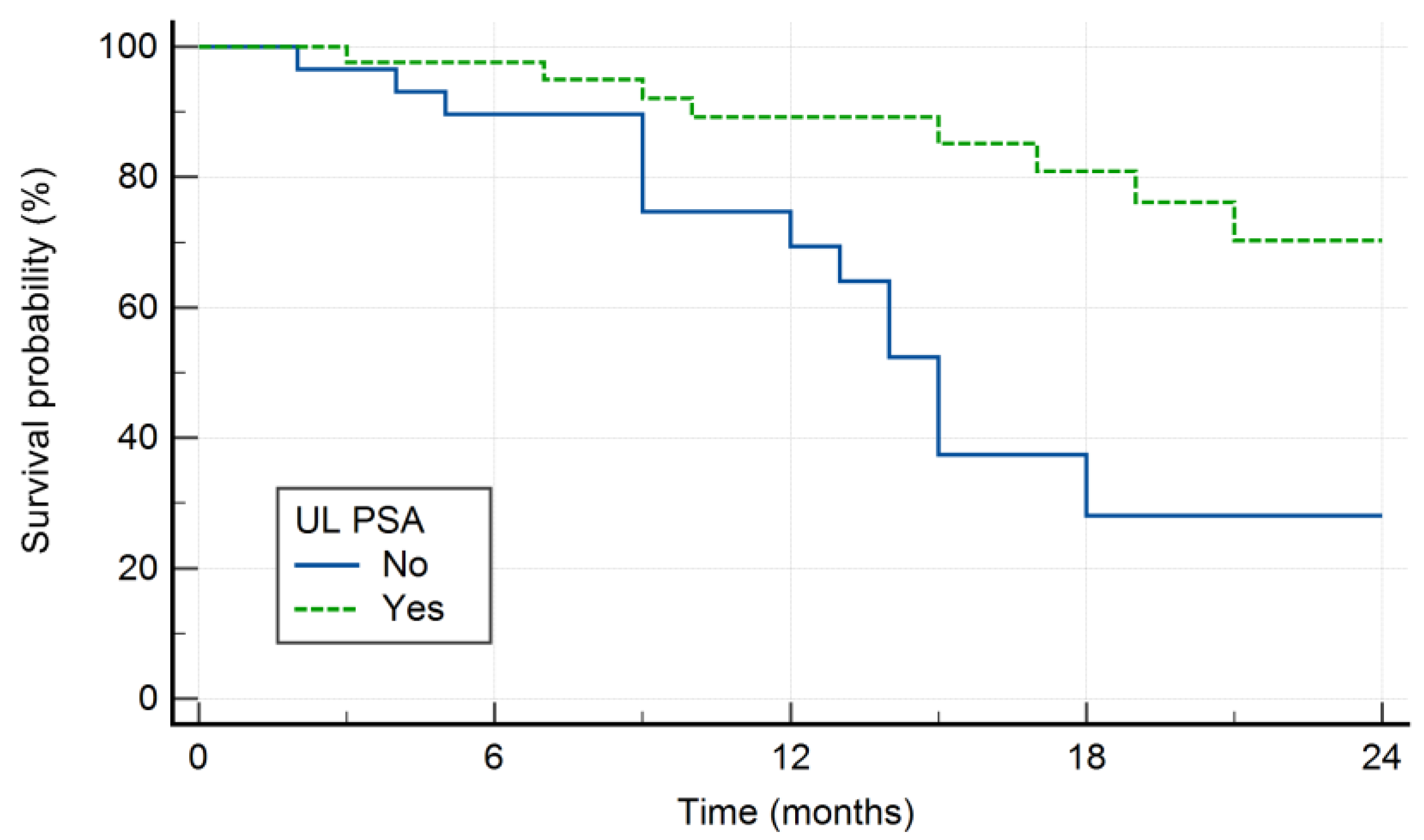

Kaplan-Meier survival curve of patients with respect to UL PSA is shown in

Figure 3.

Factors associated with UL PSA levels in univariate model were: age <71 and metachronous pattern of metastatic disease and low volume metastatic disease (Table 2). In logistic regression model the only independent predictor of UL PSA status was age <71 years (

Table 3).

Table 2.

Factors associated with UL PSA levels in univariate analysis.

Table 2.

Factors associated with UL PSA levels in univariate analysis.

| Variable |

Non UL PSA |

UL PSA |

P value |

Years

<71

>71 |

9

20 |

25

17 |

0.0190

|

GS

<7

≥8 |

7

22 |

18

24 |

0.1070 |

PSA median

<87

>87 |

8

21 |

26

16 |

0.318 |

Metastatic pattern

Metachronus

Synchroronous |

5

24 |

18

24 |

0.0244

|

Diseases volume

Low

High |

2

27 |

13

29 |

0.0154

|

Type of therapy

Enzalutamide

Abiraterone

Apalutamide

Triplet |

18

4

2

5 |

28

3

5

6 |

0.715 |

Table 3.

The logistic regression—independent predictors of UL PSA.

Table 3.

The logistic regression—independent predictors of UL PSA.

| Covariate |

Coefficient |

SE |

Wald |

P |

| Years (median) |

-1.88853 |

0.68060 |

7.6995 |

0.0055 |

| Gleason score ( <7 vs ≤8) |

-0.28438 |

0.63290 |

0.2019 |

0.6532 |

| iPSA_(median) |

-1.22873 |

0.81816 |

2.2555 |

0.1331 |

| GhRh vs bilateral orchiectomy |

0.19384 |

0.63967 |

0.09183 |

0.7619 |

| Metastases timing (synchronous vs metachronous |

-0.59124 |

0.85286 |

0.4806 |

0.4882 |

| Disease volume (low vs high) |

-0.89503 |

0.92733 |

0.9316 |

0.3345 |

| Treatment type |

-0.12416 |

0.26305 |

0.2228 |

0.6369 |

| Constant |

5.12870 |

2.32747 |

4.8556 |

0.0276 |

Patients were followed up from 6 to 32 months (median 13 months). At the end of the follow-up period 22 (31%) patients died from disease/other causes. Interestingly, in our cohort, 5 out of 71 patients (7% of the cohort, 11.9% of UL PSA group) achieving UL PSA levels experienced radiographic progression and died from disease with the median OS of 13.5 months. In this subgroup, all of patients had high volume/high risk disease with symptomatic disease and rapid clinical deterioration.

4. Discussion

Introduction of ARTA in treatment of prostate cancer has significantly change the outcomes of patients in metastatic setting [

1,

2,

3]. However, despite all therapeutic advances, when the disease reaches the castration resistant stage there is limited efficacy of the existing treatment options. Furthermore, there are no identified biomarkers that could tailor treatment of these patients. Also, the choice of the optimal treatment is determined by numerous factors such as disease volume and risk (CHAARTED/LATITUDE criteria, disease dynamic (metastatic disease from previously treated locoregional disease vs de novo mHSPC), and the patient’s features (ECOG PS, comorbidities, age at diagnosis, etc.) [

7,

8]. However, there are no general recommendation with respect to optimal treatment with respect to the previously mentioned characteristics.

Recently, with the development of ultrasensitive assays, it has become increasingly common to detect PSA levels below 0.2 ng/mL.

Our results confirm that achieving an UL PSA level in mHSPC is associated with favorable outcomes, in alignment with prior reports [

4,

5,

9,

10]. Also, we have identified similar incidence of UL PSA as in previously mentioned cohorts.

However, in this study, we have identified a subgroup of patients experiencing radiographic progression despite UL PSA levels. This phenomenon—radiographic progression in the absence of PSA progression has been described in various prostate cancer settings [

11,

12,

13]. In our cohort, all these patients were characterized by high-risk disease features and rapid clinical deterioration, suggesting that despite achieving profound biochemical responses, aggressive tumor biology can drive disease progression. This observation raises important questions about the prognostic reliability of PSA level as a surrogate for disease control, and suggests heterogeneity in disease biology and patterns of cancer resistance.

What is less clear from the literature is whether this discordance is characteristic of patients who achieve UL PSA levels. Most published analyses examine discordance across all PSA strata, not specifically in UL PSA cohort [

14,

15]. Our finding suggests that even among “best” PSA responders, some might develop resistant clones that manifest via imaging progression without PSA rise. To our knowledge this is a first comprehensive report in the literature describing and analyzing radiographic progression and subsequent mortality in patients who achieved UL PSA levels for metastatic prostate cancer.

Furthermore, these findings underscore the limitations of using PSA response, even at UL levels, as the sole marker of treatment efficacy and disease monitoring. The following clinical considerations are recommended:

Radiographic surveillance remains essential even in UL PSA achievers, as a subset may develop non-biochemical progression.

Risk stratification tools incorporating imaging, baseline clinical characteristics (e.g., high-volume/high risk disease), and genomic data may help identify at-risk patients.

Molecular profiling (e.g., cfDNA, RNA expression) in progressing patients may uncover mechanisms of resistance, including neuroendocrine (de)differentiation or AR-independent pathways [

8,

10].

Alternative endpoints: Trials and clinical practice should use other endpoints that include imaging and symptomatic clinical progression, not just PSA dynamic.

In the current study, we have also evaluated potential predictors of achieving UL PSA levels. Notably, our multivariate analysis identified age <71 years as the only independent predictor of achieving a UL PSA response. This finding is partially divergent from previously published studies, where tumor-related factors such as baseline PSA levels and timing of metastatic presentation were more commonly associated with deeper PSA responses.

In a recent multicenter cohort study by Martínez-Corral et al., which included 586 mHSPC patients treated with ADT and ARTA, the authors specifically examined predictors of achieving deep PSA responses, including a PSA nadir <0.02 ng/mL at 6 months (TITAN criteria) and <0.2 ng/mL (SWOG criteria) [

16]. They found that baseline PSA <50 ng/mL and metachronous metastatic disease were significantly associated with achieving UL PSA levels in multivariate analysis. In contrast, age was not reported as a significant predictor in their model, although it was included as a covariate [

1]. These differences may suggest cohort-specific variations in patient and disease characteristics or differing statistical power between studies.

Similarly, López--Abad et al. reported that low-volume disease, metachronous metastases, and M1a staging were associated with a higher likelihood of achieving UL PSA in a multicenter real-world study of 193 mHSPC patients treated with apalutamide plus ADT [

5]. Again, age was not found to be a significant factor. These findings reinforce the consistent role of disease burden and metastatic timing in predicting depth of PSA response.

Furthermore, Sweeney et al. demonstated that addition of enzalutamide for all patients with metachronous metastases and low-volume disease was associated with higher survival rates [

17]. The study did not identify age as a significant independent predictor. Collectively, these findings underscore the importance of disease biology, particularly the timing and extent of metastatic spread, in influencing treatment response.

Our identification of younger age (<71 years) as the only independent predictor of UL PSA contrasts with the aforementioned studies and may reflect differences in patient demographics, treatment regimens, or sample size. One potential explanation is that younger patients may exhibit better treatment adherence, more robust immune responses, or even more favorable tumor biology that facilitates deeper PSA declines. Alternatively, our study may have lacked sufficient variability in disease characteristics such as baseline PSA or metastatic volume, limiting our ability to detect associations observed in larger cohorts. However, while younger patients were more likely to achieve UL PSA in our study, age <71 years was negative prognostic factor with respect to survival in multivariate model. One of the potential explanation for such phenomenon might be that all patient achieving UL PSA and experiencing radiographic progression were within this age group.

Limitations of the Study

This study has all of the weaknesses associated with retrospective design of the study. Also, the relatively small number of patients precludes a clear conclusion and this data and results need to be validated within controlled and well balanced trials. However, this is single institution and tertiary cancer center study with strict follow up and we believe that these results contribute to the existing body of knowledge in the context of confirming prognostic significance of UL PSA as well as analysis of other clinical and histopathological factors.

Furthermore, we believe that the identification of a subgroup of UL PSA patients with radiographic progression represents a novel and clinically relevant nuance. It underscores that PSA suppression, even when pronounced and rapid, does not universally guarantee durable disease control. These patients may represent a biologically distinct, therapy resistant subset. Therefore, prudent imaging surveillance and consideration of escalation strategies are warranted, and future translational and prospective studies should focus on understanding and managing this subgroup of patients.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our real-world data demonstrated that UL PSA is a favorable prognostic factor associated with prolonged survival and improved prognosis. However, radiographic progression can occur in a small but clinically important subset of patients who achieve UL PSA levels. This challenges the prevailing assumption that deep PSA suppression is a universally positive prognostic marker and emphasizes the continued importance of imaging surveillance and comprehensive risk stratification in the management of metastatic prostate cancer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S. and V.G.; methodology, P.S. and V.G.; software, P.S.; validation P.S.. and V.G.; formal analysis, P.S.; investigation, P.S.. and V.G.; resources, P.S.. and V.G.; data curation, P.S.. and V.G.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S.. and V.G.; writing—review and editing, P.S.. and V.G.; visualization, P.S.. and V.G.; supervision, P.S.. and V.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Dubrava University Hospital (4 September 2025). Code of the approval: 2025/0904-3.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent for participation was not required because of the retrospective nature of this study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University Hospital Dubrava.:

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to ethical reasons. Further inquiries should be directed to the corresponding author.:

Acknowledgments

The authors utilized the Perplexity AI language model to assist in reviewing and improving the grammar and spelling of the manuscript text.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PSA |

prostate-specific antigen |

| mHSPC |

metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer |

| mCRPC |

metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer |

| ARTA |

Androgen Receptor-Targeted Agents |

| ADT |

Androgen Deprivation Therapy |

| GnRH |

Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone |

| OS |

overall survival |

| rPFS |

radiographic progression-free survival |

References

- Chi, K.N.; Agarwal, N.; Bjartell, A.; Chung, B.H.; Pereira de Santana Gomes, A.J.; Uemura, H.; Ye, D.; Given, R.; Miladinovic, B.; Lopez-Gitlitz, A.; et al. Apalutamide plus androgen-deprivation therapy for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2294–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, A.J.; Szmulewitz, R.Z.; Petrylak, D.P.; Holzbeierlein, J.; Villers, A.; Shore, N.D.; Hussain, M.; Karrison, T.; Gross, M.; Clarke, N.W.; et al. ARCHES: A randomized, phase III study of enzalutamide plus androgen deprivation therapy versus placebo plus androgen deprivation therapy in men with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 2974–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fizazi, K.; Tran, N.; Fein, L.; Matsubara, N.; Rodriguez-Antolin, A.; Alekseev, B.Y.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Ye, D.; Feyerabend, S.; Protheroe, A.; et al. Abiraterone plus prednisone in metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merseburger, A.S.; Kuczyk, M.A.; Mertens, C.; Heinzer, H.; Herold, C.J.; Quhal, F.; Yildirim, M.A.; Bach, D.; Dork, T.; Gakis, G.; et al. Post-hoc analysis of the TITAN trial: Ultralow PSA response with apalutamide plus androgen-deprivation therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2024, 133, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López--Abad, A.; Belmonte, M.; Ramírez Backhaus, M.; Server Gómez, G.; Cao Avellaneda, E.; Moreno Alarcón, C.; López Cubillana, P.; Yago Giménez, P.; de Pablos Rodríguez, P.; Juan Fita, M.J.; et al. Ultralow prostate--specific antigen (PSA) levels and improved oncological outcomes in metastatic hormone--sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC) patients treated with Apalutamide: A real--world multicentre study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosso, D.; Pagliuca, M.; Sonpavde, G.; Pond, G.; Lucarelli, G.; Rossetti, S.; Facchini, G.; Scagliarini, S.; Cartenì, G.; Daniele, B.; Morelli, F.; Ferro, M.; Puglia, L.; Izzo, M.; Montanaro, V.; Bellelli, T.; Vitrone, F.; De Placido, S.; Buonerba, C.; Di Lorenzo, G. PSA Declines and Survival in Patients with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Treated with Enzalutamide: A Retrospective Case-Report Study. Med. 2017, 96, e6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fizazi, K.; Tran, N.; Fein, L.; Matsubara, N.; Rodriguez-Antolin, A.; Alekseev, B.Y.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Ye, D.; Feyerabend, S.; Protheroe, A.; et al. Abiraterone plus prednisone in metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, C.J.; Chen, Y.H.; Carducci, M.; Liu, G.; Jarrard, D.F.; Eisenberger, M.; Wong, Y.N.; Hahn, N.; Kohli, M.; Cooney, M.M.; et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone--sensitive prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, A.A.; Armstrong, A.J.; Petrylak, D.P.; et al. Enzalutamide and Prostate-Specific Antigen Levels in Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Secondary Analysis of the ARCHES Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8(5), e2833622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, D.-W.; Uemura, H.; Chung, B.H.; Suzuki, H.; Mundle, S.; Bhaumik, A.; Singh, A.; Chowdhury, S.; Agarwal, N.; Chi, K.N.; Huang, J. Prostate-Specific Antigen Kinetics in Asian Patients with Metastatic Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer Treated with Apalutamide in the TITAN Trial: A Post Hoc Analysis. Int. J. Urol. 2025, 32, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryce, A.H.; Alumkal, J.J.; Armstrong, A.; Higano, C.S.; Iversen, P.; Sternberg, C.N.; Rathkopf, D.; Loriot, Y.; de Bono, J.; Tombal, B.; et al. Radiographic progression with non--rising PSA in metastatic castration--resistant prostate cancer: post hoc analysis of PREVAIL. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2017, 20, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, I.D.; Martin, A.J.; Zielinski, R.R.; Thomson, A.; Tan, T.H.; Sandhu, S.; Reaume, M.N.; The Australian and New Zealand Urogenital and Prostate Cancer Trials Group. Radiographic Progression without PSA Progression in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer (mHSPC): A Retrospective Analysis from the ENZAMET Trial (ANZUP 1304). J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42 (Suppl. 4), Abstract 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.; Bhaumik, A.; Agarwal, N.; Shotts, K.M.; Lopez-Gitlitz, A.; McCarthy, S.; Mundle, S.D.; Chi, K.N.; Small, E.J. Radiographic Progression without PSA Progression in Advanced Prostate Cancer Patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43 (Suppl. 5), Abstract 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.J.; Mottet, N.; Iguchi, T.; Szmulewitz, R.Z.; Holzbeierlein, J.; Villers, A.; Alcaraz, A.; Alekseev, B.; Shore, N.D.; Gomez-Veiga, F.; Rosbrook, B.; Zohren, F.; Lee, H.-J.; Haas, G.; Stenzl, A.; Azad, A.A. Radiographic Progression in the Absence of Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Progression in Patients with Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer (mHSPC): A Post Hoc Analysis of ARCHES. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40 (Suppl. 16), 5072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuokaya, W.; Yanagisawa, T.; Mori, K.; Urabe, F.; Rajwa, P.; Briganti, A.; Shariat, S.F.; Kimura, T. Radiographic Progression without Corresponding Prostate-Specific Antigen Progression in Patients with Metastatic Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer Receiving Apalutamide: Secondary Analysis of the TITAN Trial. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2025, 8, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Corral, R.; De Pablos-Rodríguez, P.; Bardella-Altarriba, C.; Vera-Ballesteros, F.J.; Abella-Serra, A.; Rodríguez-Part, V.; Martínez-Corral, M.E.; Picola-Brau, N.; López-Abad, A.; Gómez-Ferrer, Á.; Beamud-Cortés, M.; Suárez-Novo, J.F.; López-González, P.Á.; García-Puche, M.; Álvarez-Gracia, A.M.; Pérez-Fentes, D. PSA Kinetics and Predictors of PSA Response in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer Treated with Androgen Receptor Signaling Inhibitors. Urol. Oncol. 2025, 43, 527.e9–527.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, C.J.; Martin, A.J.; Stockler, M.R.; Begbie, S.; Chi, K.N.; Chowdhury, S.; Coskinas, X.; Frydenberg, M.; Hague, W.E.; Horvath, L.G.; Joshua, A.M.; Lawrence, N.J.; Marx, G.M.; McCaffrey, J.; McDermott, R.; McJannett, M.; North, S.A.; Parnis, F.; Parulekar, W.; Pook, D.W.; et al. Overall Survival of Men with Metachronous Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer Treated with Enzalutamide and Androgen Deprivation Therapy. Eur. Urol. 2021, 80, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).