1. Introduction

When photovoltaic (PV) systems are linked to the grid, they function as generation units within the power system. These systems can be incorporated into the power grid either centrally or in a distributed manner. Centralized PV systems resemble traditional utility-scale power plants in their size, location away from end-users, and connection to transmission grids or occasionally medium voltage (MV) distribution grids. On the other hand, decentralized PV systems are typically smaller in scale, widely dispersed, located nearer to consumers, and frequently linked to the distribution network [

1]. The integration of PV systems into the power system can lead to several problems, such as overvoltage and component overloading. These can shorten the lifespan of electrical system components and need costly grid upgrades [

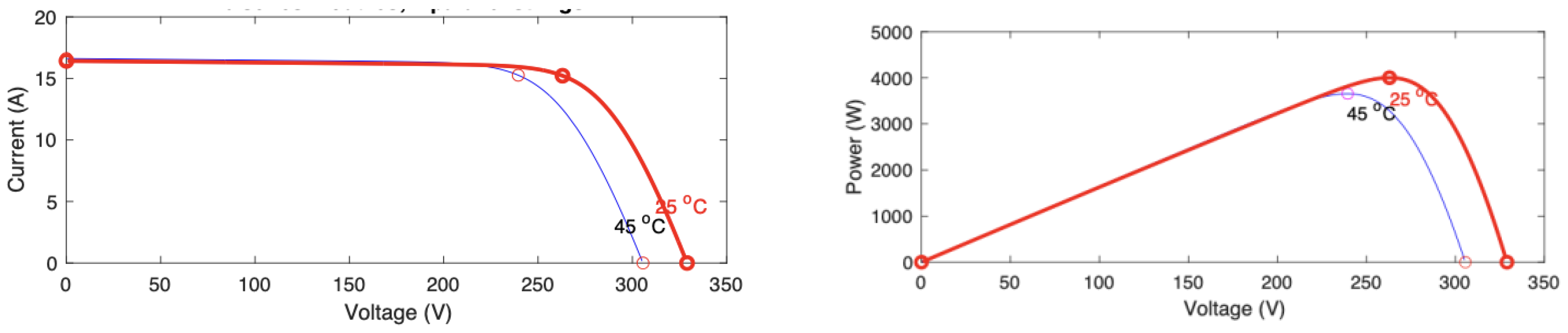

2]. One of the main difficulties associated with PV systems is their unpredictable generation patterns. Unlike conventional power plants that can be adjusted to meet specific demands, PV systems without battery storage cannot be controlled and are considered non-dispatchable sources of power. This limitation poses a significant challenge as power plants are typically designed to cater to the fluctuating power needs of consumers. PV power production fluctuates throughout the year and the day, influenced by the sun's movement across the sky. The highest levels of PV power are typically generated around midday during sunny summer days, significantly surpassing production levels at other times of the day. Production is completely halted during nighttime hours. In addition to these predictable patterns, power generation can be further affected by intermittent cloud cover, leading to a decrease in energy production [

3]. This variable aspect of PV power can lead to several problems, such as voltage and frequency fluctuations. Adding storage components, such as batteries, can overcome the problems.

The power grid has a restricted capacity for accommodating distributed generations (DGs) like PVs and new loads such as electric vehicles (EVs) without expensive upgrades to the utility system. Nevertheless, when PVs and EVs are connected to the grid, there is often a discrepancy between energy demand and power generation. One way to address this issue is by harnessing the synergy between PVs and EVs through coordination, control, and implementing smart charging strategies for EVs [

2,

4,

5]. The inclusion of PVs as DGs and high-consuming loads such as EVs not only interrupted the grid performance but also offered opportunities for grid performance improvement [

6,

7].

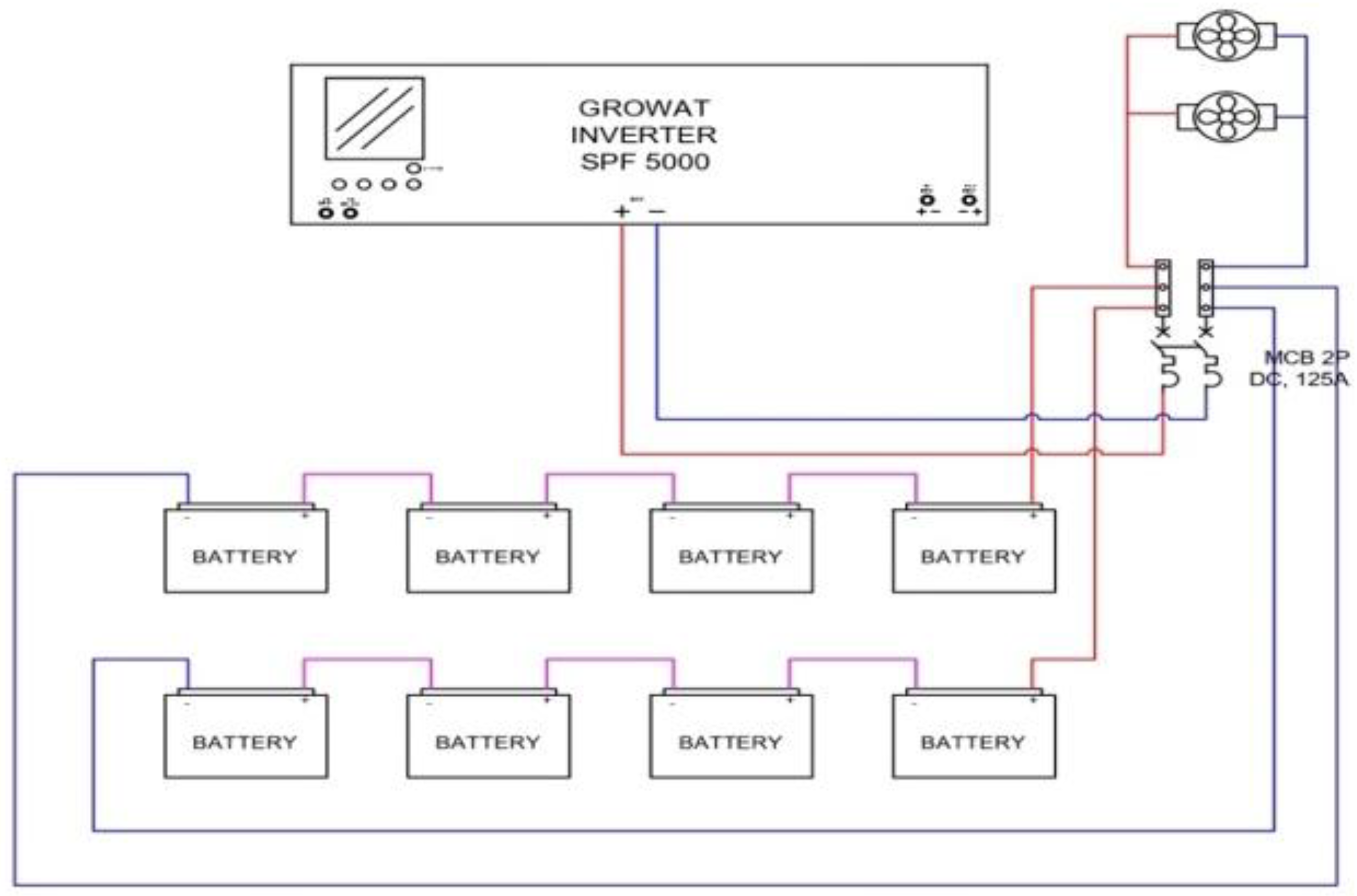

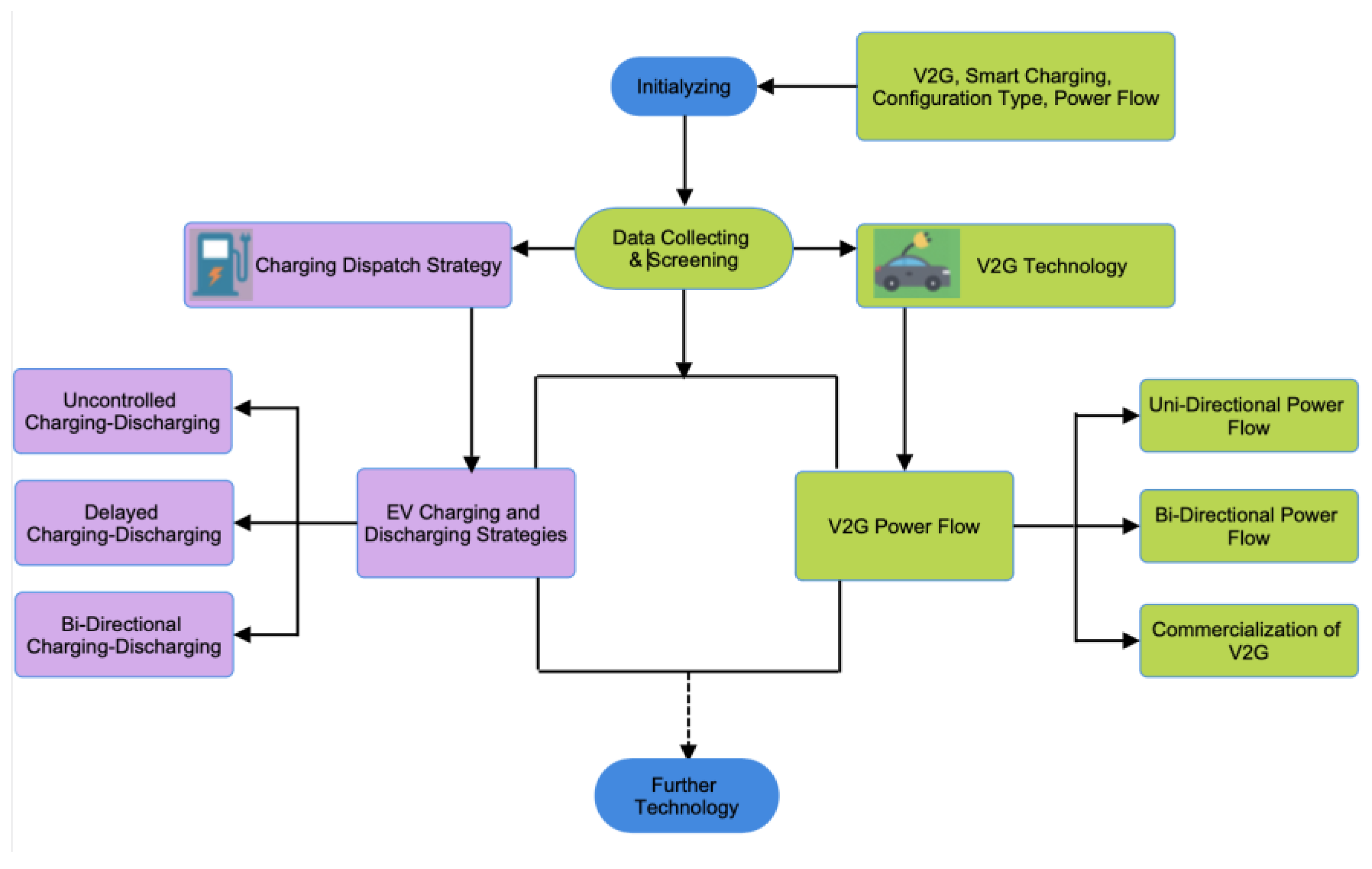

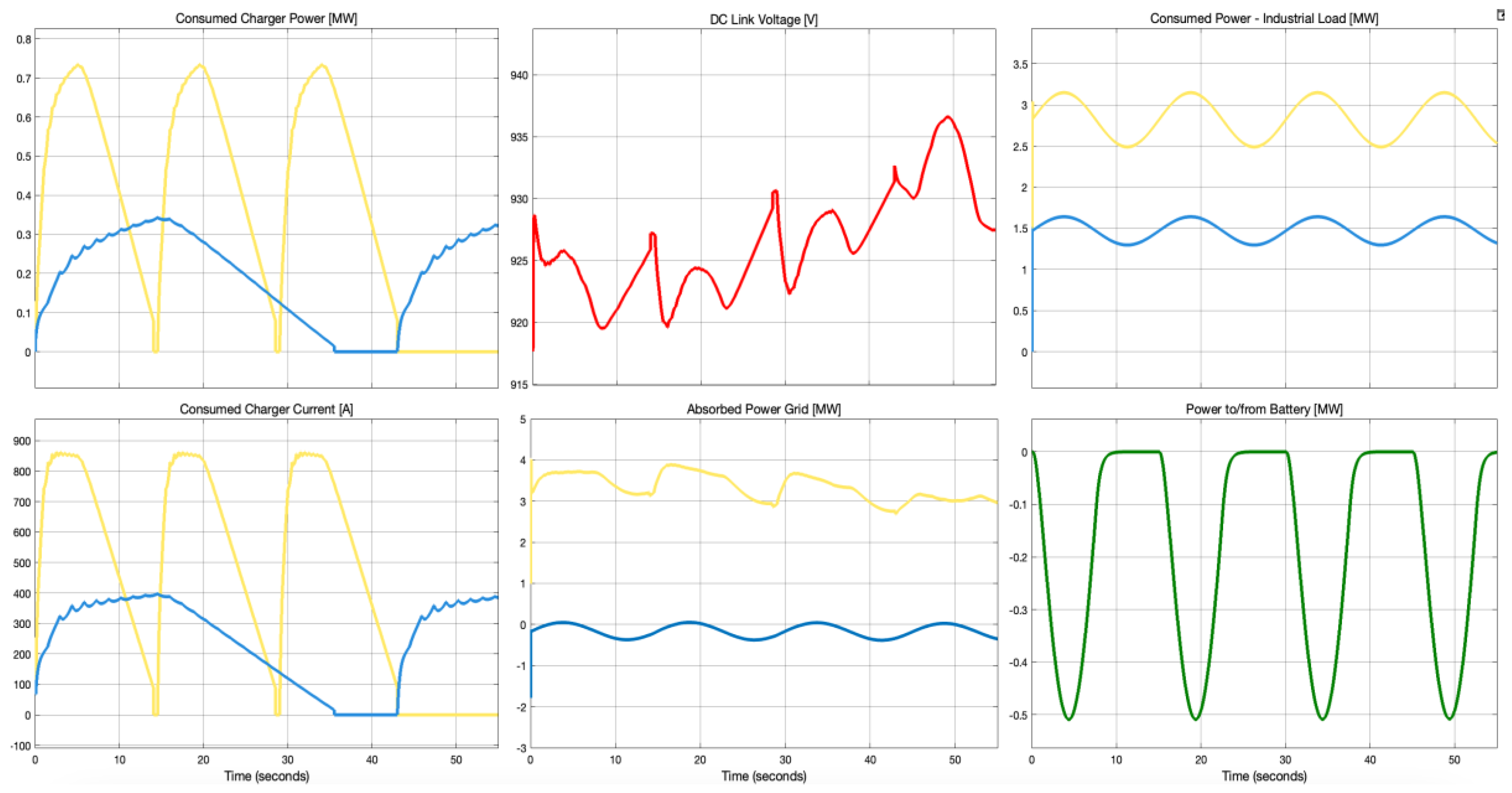

Figure 1 presents the underlying power system theory of PV-EV integration in the power grids.

Figure 1(a) illustrates a PV system and EVs in the distribution grid. Simplified electric circuit representations when being power consumer, power producer, and in a state of power balance are shown in

Figure 1 (b)-(d), respectively. In

Figure 1 (b)-(d), PDG is the DG power generation (kW), PL is the load (kW), VT is the voltage level at the transformer substation (V), VL is the voltage level at load/customer’s side (V), I

TL is the current flowing from transformer to load (A), I

LT is the current flowing from load to transformer (A), P

loss is the dissipated power loss (kW), R is the equivalent resistance of the feeder (Ω), X is the equivalent reactance of the feeder (Ω), j is an imaginary unit, cos φ is the power factor, sin φ is the reactive power factor, Q

L is the reactive power in the customer’s side (kVA).

Figure 1(b) shows the phenomenon of voltage drop, assuming a much higher value of R compared to X in typical distribution grids [

8]. When a customer is using electricity, the voltage on their side is often lower than the manageable voltage level at the substation. This voltage drop is primarily due to the current flowing through the cables and the resistance they offer, leading to power loss in the form of heat. During times of excessive demand, there is a possibility of undervoltage, where the voltage falls below safe levels, and the components may become overloaded with too much current or heat. This situation poses risks to both the users and the appliances being used [

9]. The phenomenon of voltage rise is shown in

Figure 1(c)., when the customer is a power producer, the voltage level on the customer’s side is typically higher than the controlled voltage level in the substation. Power losses occur as heat when currents travel from the customer's end to the substation. Excessive generation poses risks like overvoltage, exceeding safe limits, and component overloading due to high current or heat. When a power producer achieves a balance between production and consumption, with zero reactive power, the voltage on the customer's end usually stays within a safe range. Furthermore, there are no power losses, since no current flowing between the substation and the customer, as shown in

Figure 1(d).

When an EV is connected to the power grid for charging, it functions as a consumer of electricity within the power system. The current power grid infrastructure was not originally built to accommodate a high volume of EV charging demands, which may present new challenges when a significant number of EVs are added to the power system [

10,

11]. The challenges include undervoltage problems and component overloading [

10]. These issues result in a reduction in the lifespan of power grid equipment like substation transformers. In such instances, there may be a need to invest in upgrading the power grid, which can be quite expensive. Typically, the greater the charging power of an EV charger, the greater its effect on the power system. Using higher power chargers can result in increased load variability as the EV charging load fluctuates more frequently and rapidly [

12]. This phenomenon is called a voltage-to-grid (V2G) scheme.

This paper proposes the design of an EV battery charging station within a grid-connected PV system, which is simulated in the Simulink MATLAB platform to synergize PV-EV power generation by applying a smart charging scenario and V2G scheme. The sections of this paper are arranged as follows;

Section 1 addresses the need to design and simulate the EV battery charging station within a grid-connected PV system.

Section 2 literates the enhancement of PV-EV synergy, or we called it the V2G scheme, through a brief review of EVs’ smart charging scenario, as well as its mathematical models and algorithms.

Section 3 describes the simulation process of designing the EV battery station within the PV system.

Section 4 discusses the results, and last but not least, Section 5, concludes the works.

2. Methods

2.1. Enhancing PV-EV Synergy (V2G Concept)

Analytical methods and design charts used for the simulation throughout the Simulink Matlab platform. The simulation describes the PV system, the charging station, the smart charging of the EV battery scenario, and the V2G scheme. The V2G concept was in the author’s previous article [

13]. The V2G system necessitates broad involvement and a centralized scheduling mechanism for managing the charging and discharging activities of electric vehicles. The advantages and obstacles associated with the V2G concept are explored in detail [

14], which also overcomes features such as active power regulation, reactive power support, load balancing, and current harmonic filtering. However, the challenges include reduced battery life, communication overhead between EVs and grids, and changes in distribution network infrastructure are also shown. The integration of EVs into the grid offers solutions for energy storage and system services.

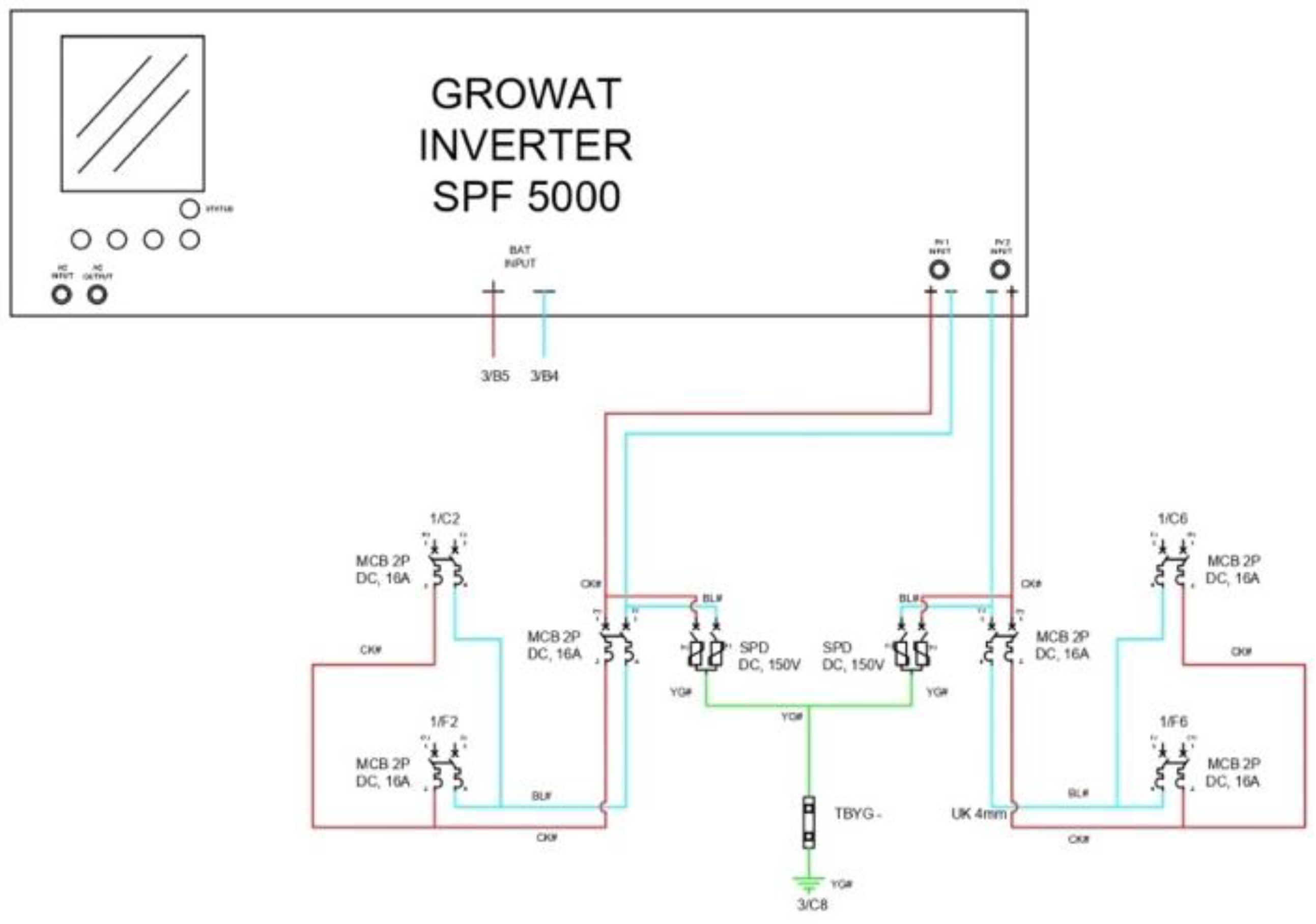

Figure 2 illustrates the V2G concept, which describes the mentioned integration.

V2G technology refers to the process of transferring surplus energy from electric vehicles back to the smart grid. V2G, or vehicle-grid integration (VGI), helps in providing additional electricity to the energy grid during periods of high demand. This technology also serves as a supplementary power source when renewable energy sources, which are reliant on weather conditions, are not accessible. An example of this scenario is when a residence relying on solar power is unable to produce electricity during nighttime hours. However, an electric vehicle could serve as an alternative power source in such situations [

15].

According to [

16], Electric vehicles are used as mobile energy storage units to meet peak load power requirements. This involves various power electronics components such as a motor, powertrain inverters, batteries, converters, and an on-board charger. The integration of V2G technology introduces advanced power electronics systems like smart grids and smart charging stations. Supervising the management of the charging and discharging of electric vehicle batteries should be conducted remotely, taking into consideration factors such as the level of battery discharge, power grid demand, battery and grid technical status, smart or traditional grid type, terms of the agreement between the vehicle owner and utility company, and the planned journey time and distance for the electric vehicle user.

2.2. Smart Charging Scenario

While the technology for exchanging electricity between EVs and homes is established, the process of transferring power from EVs to the smart grid is still in the testing phase. The key factor for V2G implementation is ensuring compatibility between electric vehicles and the smart grid. Standardizing smart grids and charging stations is crucial for the advancement of V2G technology, and the IEEE is currently working on standardization efforts in this area. To facilitate the integration of V2G technology, EVs and their chargers, referred to as power conversion equipment, are designed to be intelligent and capable of regulating the charging and discharging processes in different grid situations. Testing the performance of these systems necessitates the use of a genuine bi-directional power supply that can both supply and absorb power in various directions, as well as replicate a range of grid conditions. International standards impose strict and complicated test procedures requiring a flexible tool to generate all kinds of grid scenarios. V2Gs are needed to be tested according to various standards such as IEEE 1547 / UL 1741 / UL 458 / IEC 61000-3-15 / IEC 62116 [

17], etc.

2.3. V2G Algorithm

Batteries are widely recognized as efficient and environmentally friendly energy storage systems. Despite their benefits, batteries are prone to damage during use, making it difficult to assess their condition. Battery degradation is influenced by various factors including charging and discharging rates, depth of discharge (DoD), temperature, voltage, cycle number, and storage state of charge (SoC). Quantifying these factors can be complex [

18,

19,

20]. Battery degradation can be categorized into two main types: calendar aging and cycle aging. Calendar aging occurs when the battery is not in use, while cycle aging occurs during the charging and discharging process. The key factors influencing calendar aging are battery temperature and SoC, whereas cycle aging is influenced by the number of charge-discharge cycles, charging rate, and DoD. As a result, the increased number of charging cycles resulting from the V2G service then expedites the deterioration of the battery.

Aside from issues with battery degradation, the V2G method places importance on optimizing the efficiency of both charging and discharging processes. Loss of power during the charging and discharging of electric vehicle batteries is a common occurrence, largely attributed to power electronics like converters. These power electronics typically operate most efficiently when operating near the upper limit of their power range. Moreover, power electronics demonstrate greater efficiency during the charging process compared to discharging. This is due to the higher voltage present during charging as opposed to discharging at an equivalent power output. The elevated charging voltage results in a decreased charging current, consequently minimizing internal resistance losses.

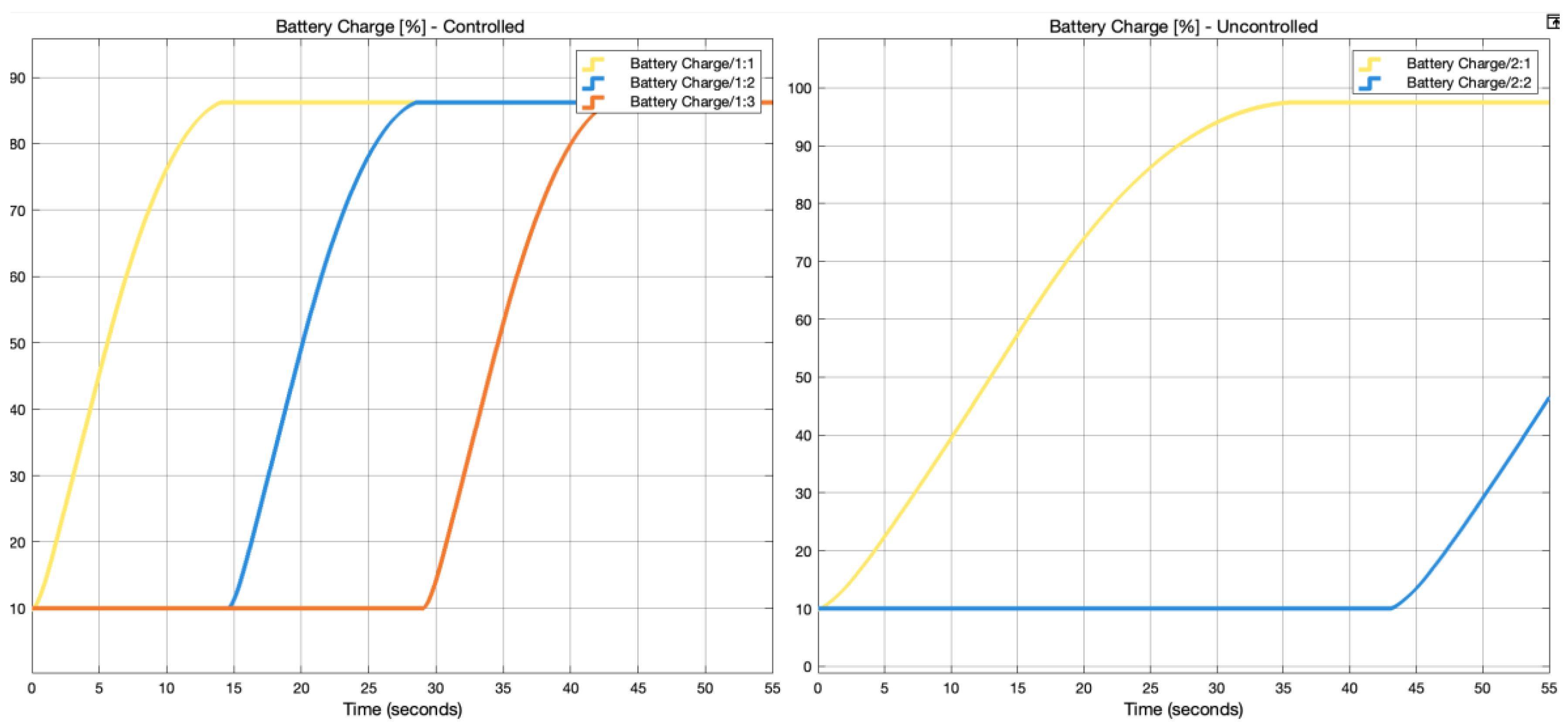

The proposed V2G algorithm provides the constant current-constant voltage (CC-CV) method using two fuzzy logics to mitigate the EVs' battery's voltage, current, and SoC. As the battery charging and discharging process runs, this method maximizes the charging power in a short period and prevents overcharging the battery. The first and second fuzzy logic controls adjust the duty cycle so that both the current and voltage can be constant.

2.4. Simulation Process

To ensure the validity and accuracy of the simulation, its steps and configuration are shown in

Figure 3. The flow chart of the simulation of the charging stations’ models and test conditions is shown in

Table 1.

The process of generating power through V2G technology is essential while electric vehicles are in operation. Different types of electric vehicles, including fuel-cell cars, battery-electric cars, and plug-in hybrids, are available in the market. To reduce peak energy consumption, the batteries of electric vehicles can be recharged during times of lower demand. In [

18], it states that every EV requires three components: (a) a network connection for power flow, (b) a logical interface for control with the grid operator, and (c) an onboard instrumentation system that monitors the vehicle. Each charging dispatch of the battery comes with advantages and disadvantages. The uncontrolled charging-discharging approach allows EVs to charge or discharge at rated power as soon as it is plugged in until the battery’s storage level equals the maximum state of charge (SoC) or unplugged [

19,

20].The controlled charging system provides electric vehicle owners with the flexibility to make charging choices independently. However, unregulated charging practices could potentially damage local distribution grids due to issues such as power loss, imbalance in supply and demand, reduced lifespan of transformers, and harmonic distortion [

21]. Uni-directional over controlled charging-discharging dispatch allows system operators to authorize over whenever EVs are charged and discharged [

19,

22,

23]. However, EV owners must hand over the control to the system operators or aggregators as soon as the EV is plugged in. A delayed controlled charging strategy provides ancillary services to power grids by using more straightforward price signals to incentivize EV owners.

Table 2 summarizes the differences between the three EV charging and discharging dispatches.

The three categories of charging dispatches are known as smart charging scenarios. These scenarios enable electric vehicle (EV) owners to control the charging or discharging of their EVs according to specific time frames and rates in order to meet predetermined objectives, such as reducing charging expenses or maintaining a balance between energy demand and supply. Despite this, many EV owners lack a clear understanding of the financial advantages associated with smart charging.

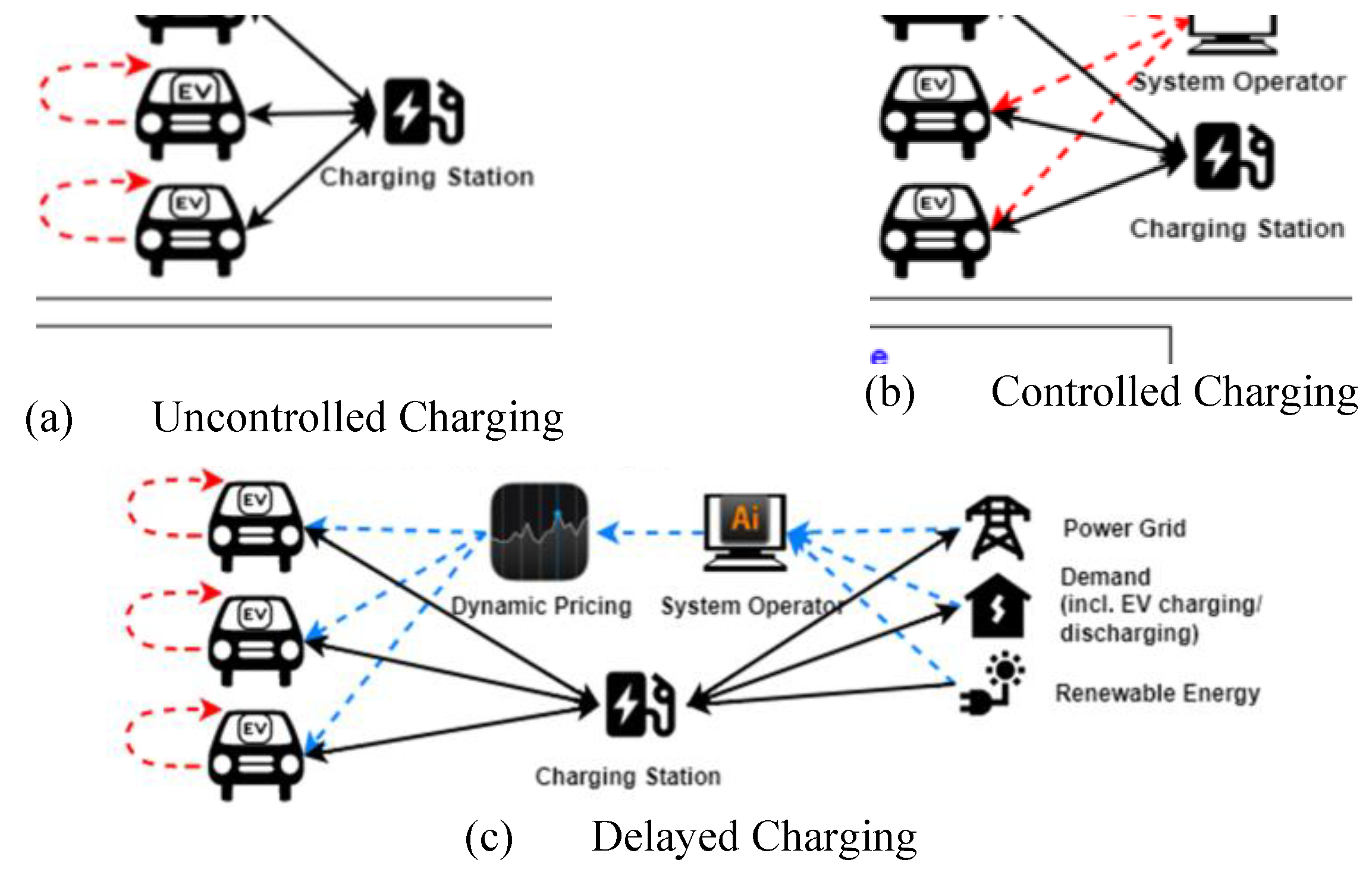

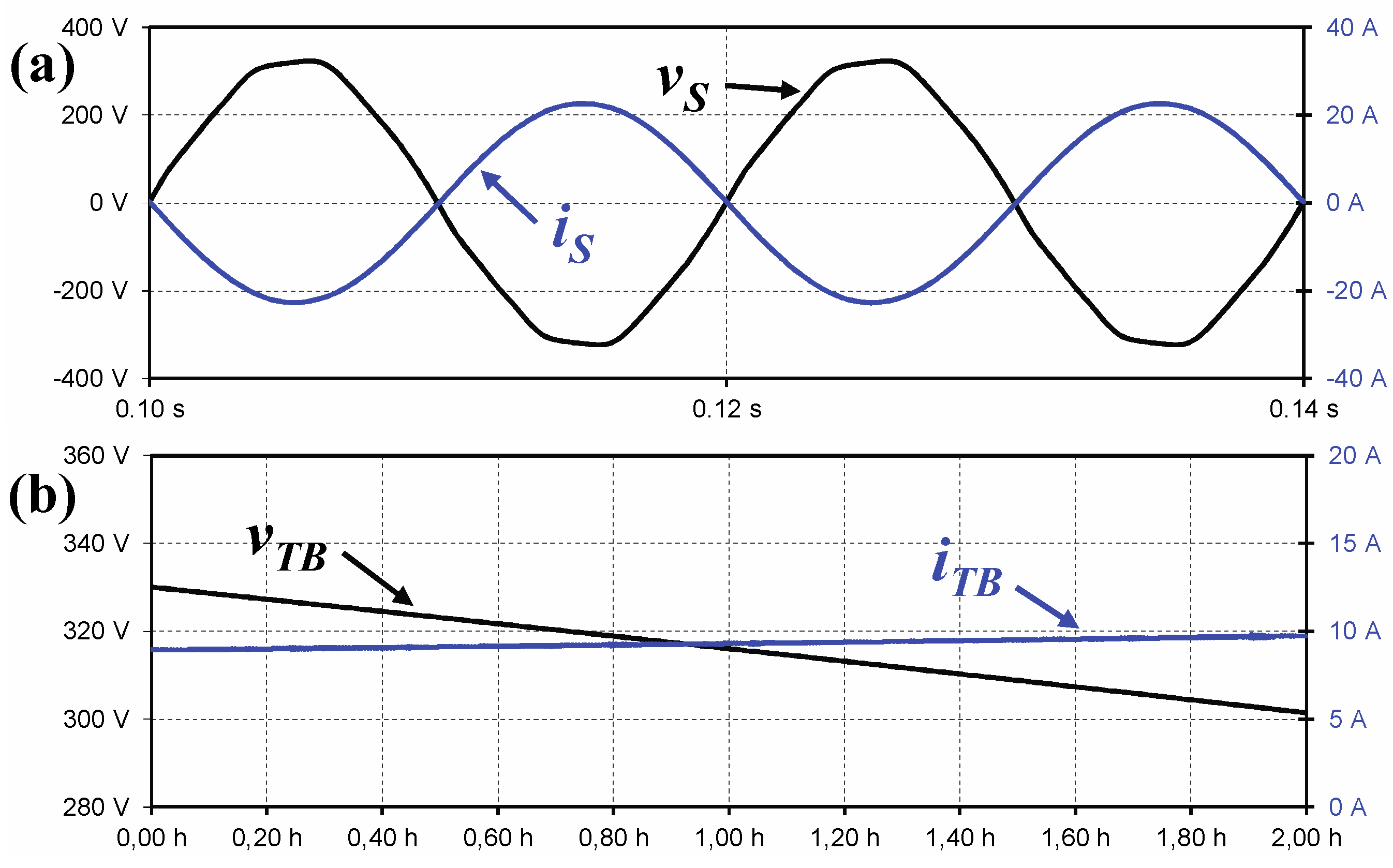

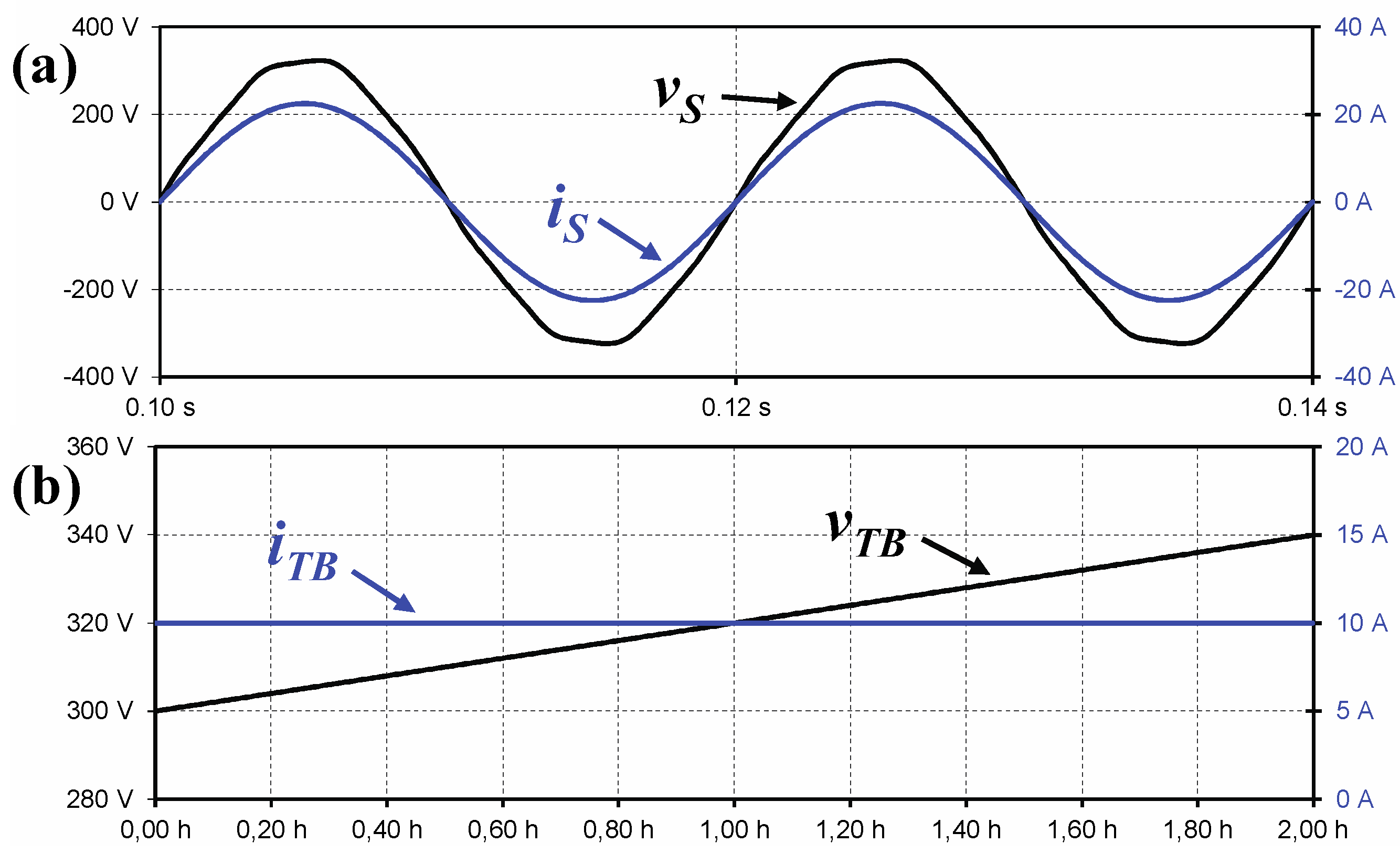

Figure 4 depicts the charging and discharging operations of the three strategies that were previously mentioned.

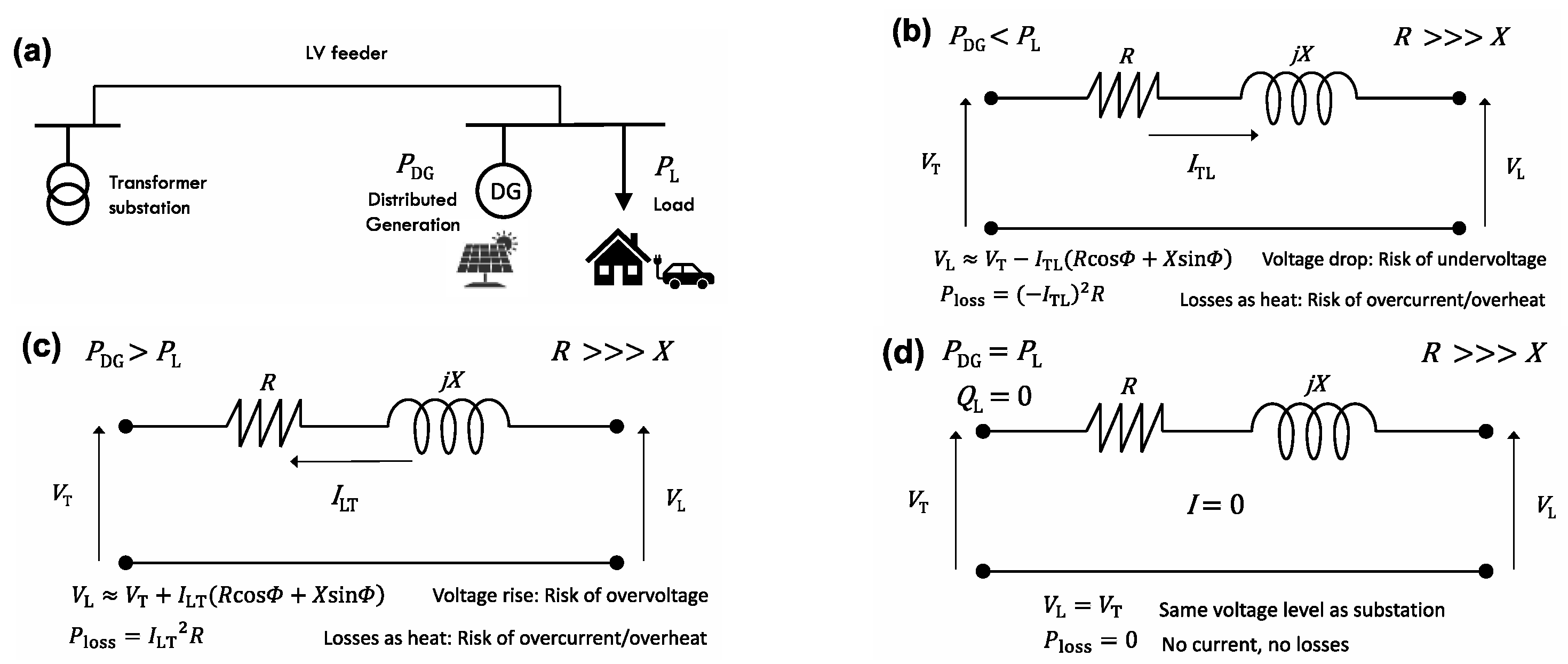

The electric vehicle charging system is designed to incorporate renewable energy sources, notably solar panels, along with a battery power storage system. There are two models involved in this system - the Battery Model (BAT) and the Inverter Model (INV). Each model serves specific purposes and offers distinct advantages in maintaining the effectiveness and longevity of the electric vehicle charging system.

Figure 5.

Model of battery charging station - Battery (BAT).

Figure 5.

Model of battery charging station - Battery (BAT).

This particular model prioritizes the utilization of batteries as the primary element for storing power in the electric vehicle charging setup. The energy generated by solar panels, with PV 1 and PV 2 serving as energy inputs, undergoes processing by the Growatt SPF 5000 inverter. This inverter is tasked with transforming the solar panel energy from DC to AC, enabling it to charge the battery effectively. This setup consists of multiple batteries placed in a series, with each battery safeguarded by a 125A 2P DC MCB for overcurrent protection. This configuration enables the stored energy in the batteries to be utilized for charging electric vehicles in the absence of grid power or as a source of backup energy during emergencies.

This model's primary benefit lies in its capability to store surplus energy generated by solar panels in batteries for later use, such as charging electric vehicles or feeding energy back into the grid with a V2G system. Moreover, the battery system offers flexibility in managing energy, enabling the charging station to function uninterrupted even during main network outages. This feature enhances the reliability and efficiency of electric vehicle charging, particularly in regions prone to power interruptions.

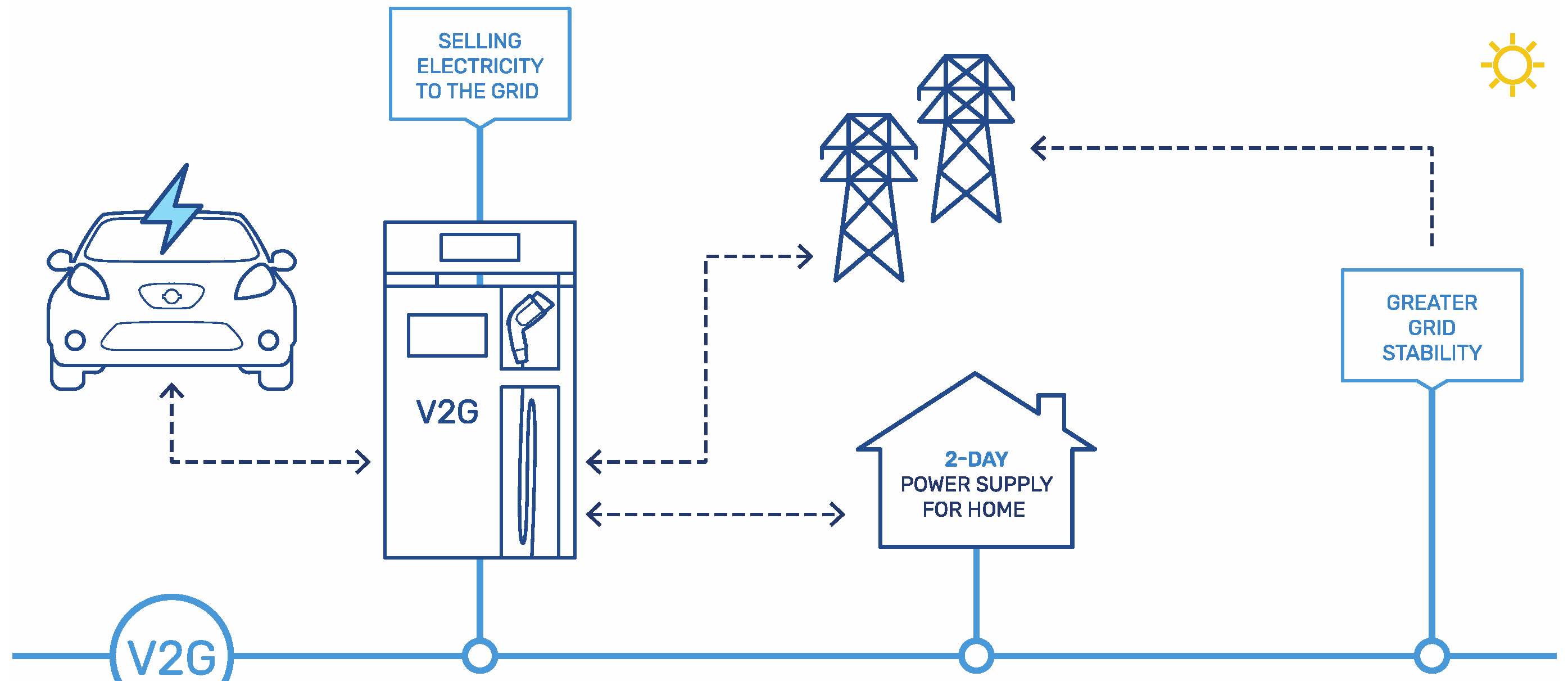

The second model emphasizes the control of power transmission from the solar panels to the inverter and then to the AC output for electric vehicle charging. It utilizes the Growatt Inverter SPF 5000 to convert DC power from the solar panels into reliable AC power. An essential component of this model is the inclusion of multiple 2P DC MCBs with a 16A capacity, serving as safeguards against overcurrent. Furthermore, this system is also furnished with a Surge Protection Device (SPD) rated at 150V, serving a crucial function in safeguarding system elements against voltage surges that have the potential to harm the device.

The charging station INV model is designed to efficiently control power distribution from solar panels to the grid or electric vehicles, offering a versatile solution for utilizing renewable energy in vehicle charging. The inverter plays a crucial role in maintaining stable and secure energy flow to the electric vehicle or grid, especially if there is a vehicle-to-grid (V2G) function. Additionally, the surge protection device (SPD) and reliable grounding safeguard the system against voltage spikes, reducing the risk of damage from unforeseen power fluctuations. In general, both models aim to enhance the efficiency and safety of eco-friendly public EV charging stations.

Figure 6.

Model of battery charging station - Inverter (INV).

Figure 6.

Model of battery charging station - Inverter (INV).

The BAT model focuses on adaptable and dependable power storage, whereas the inverter-based model prioritizes efficient power distribution and safeguarding from solar panels. By combining these models in the EV charging system, it is possible to lessen reliance on traditional networks, promote the shift towards clean energy, and ensure the sustainability of charging station operations in diverse circumstances. This aligns with worldwide initiatives aiming to encourage the use of electric vehicles as a greener and more energy-efficient option for future transportation needs.