Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

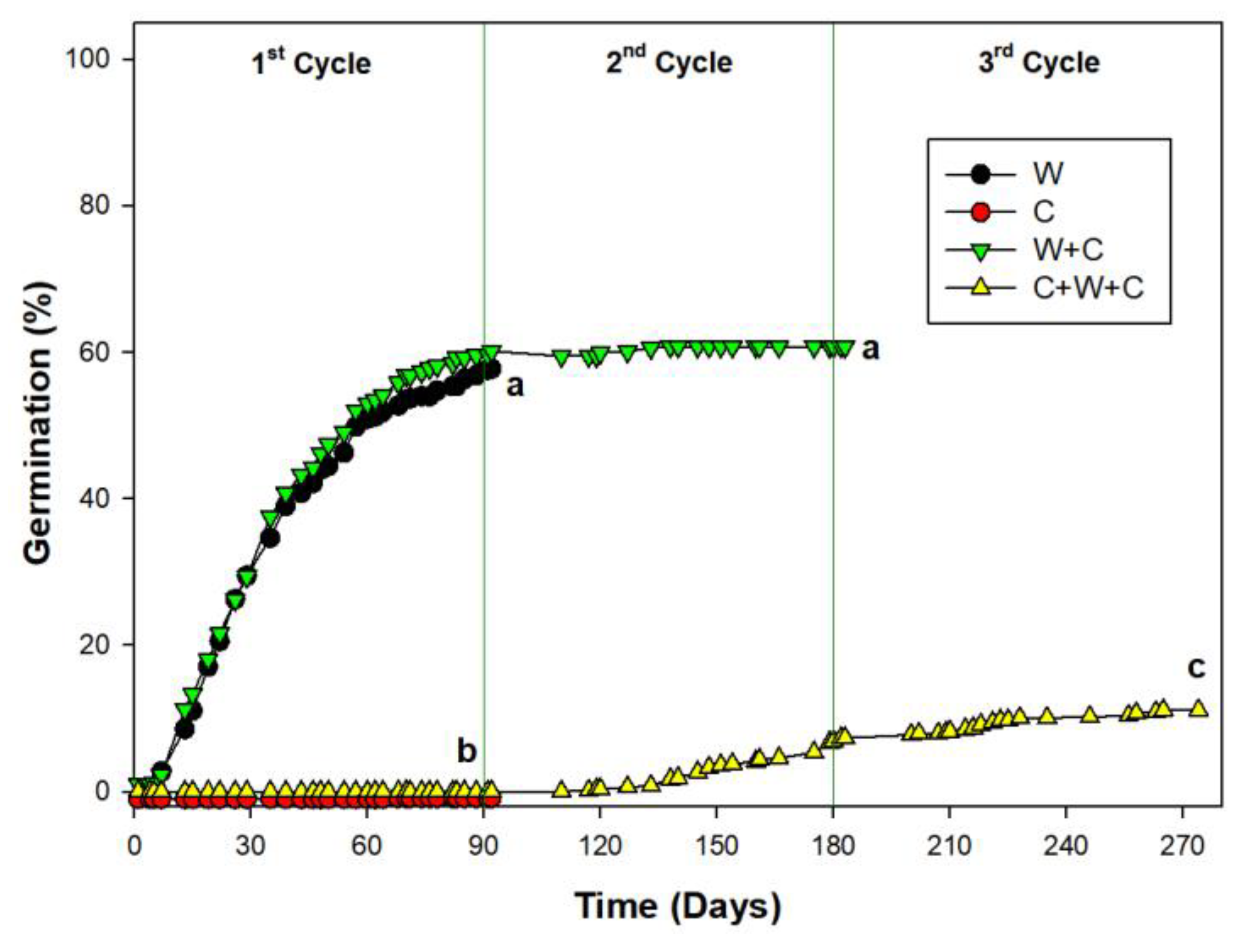

2.1. Germination DURING PRE-TREATMENT

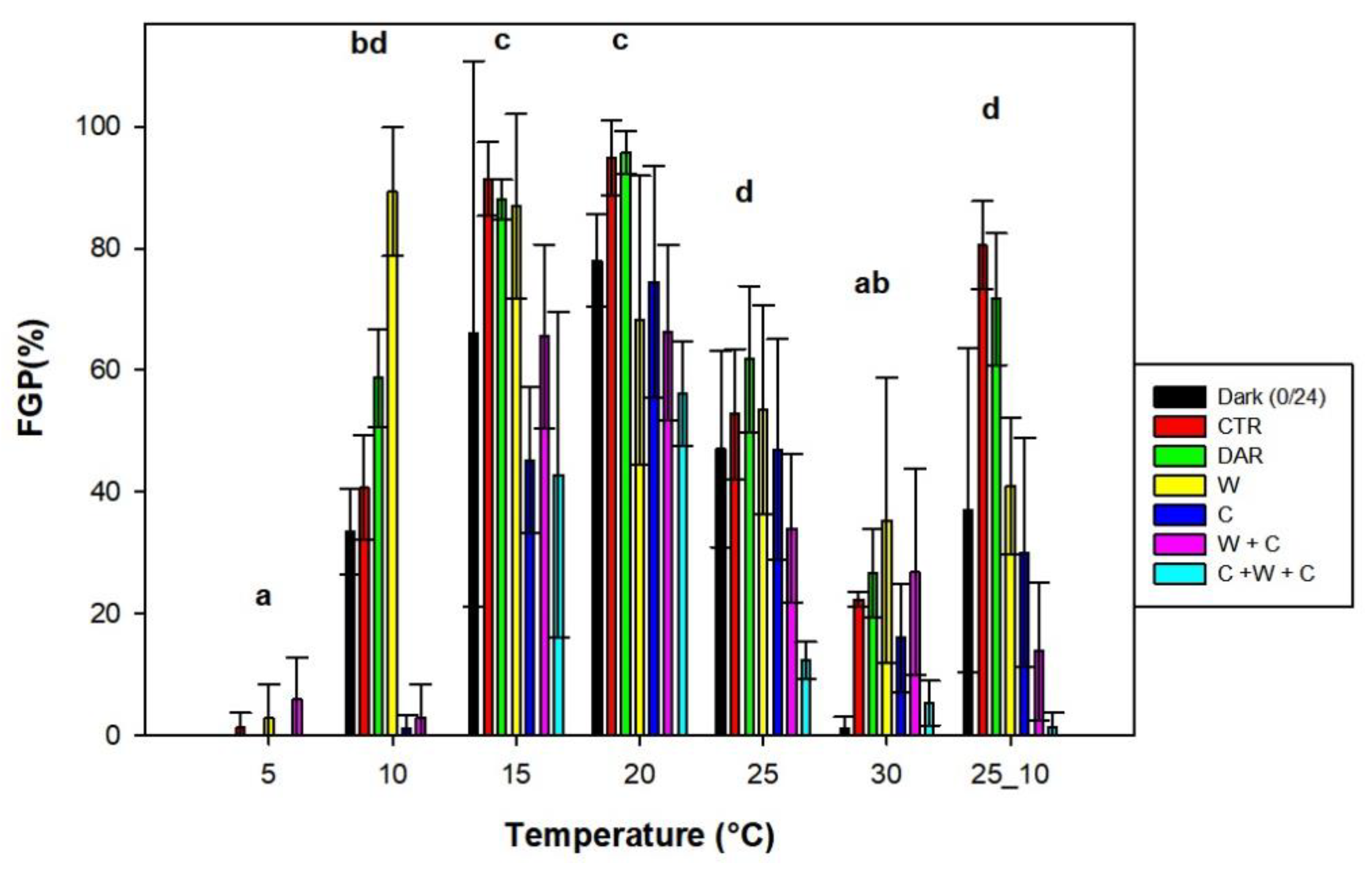

2.2. Effect of Photoperiod, Treatment and Pre-Treatments on Seed Germination

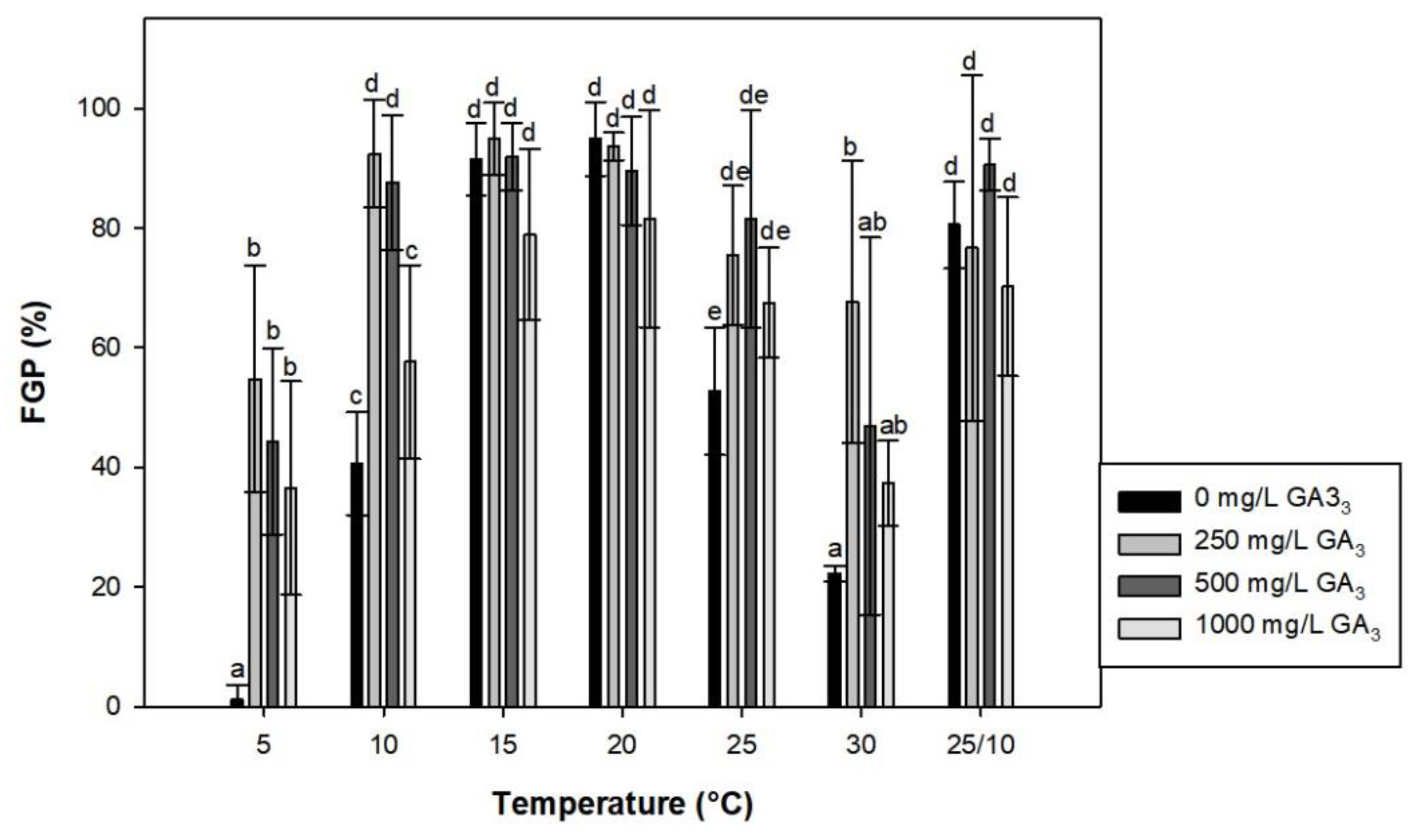

2.3. Effect of Gibberellic Acid (GA3) on Seed Germination

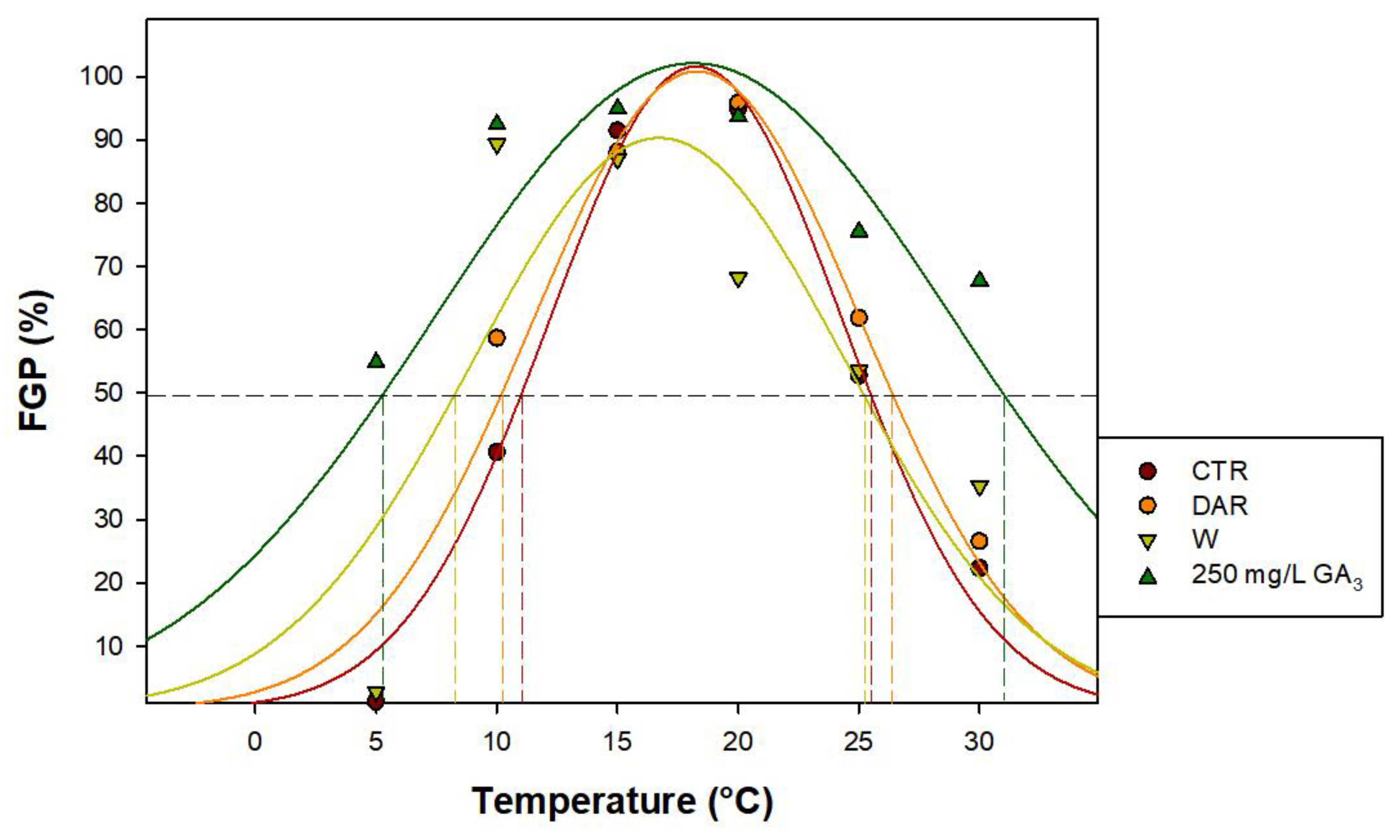

2.4. Rate and Widening of Germination Temperature

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Species

3.2. Seed Lot Collection and Preparation

3.3. Controlled Laboratory Experiments

3.3.1. Germinations Tests

3.3.2. Effect of Gibberellic Acid (GA3) on Seed Germination

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cochrane, J.A. Thermal requirements underpinning germination allude to risk of species decline from climate warming. Plants 2020, 9, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Seeds: ecology, biogeography and evolution of dormancy and germination; 2nd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fenner, M.; Thompson, K. The ecology of seeds; Cambridge University Press., 2005; ISBN 9780511614101.

- Bewley, J.; Black, M.; Halmer, P. The encyclopedia of seeds: science, technology and uses. 2006.

- Probert, R.J. The role of temperature in the regulation of seed dormancy and germination. In Seeds: the ecology of regeneration in plant communities; Fenner, M., Ed.; CAB International, Wallingford: UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Picciau, R.; Porceddu, M.; Bacchetta, G. Can alternating temperature, moist chilling, and gibberellin interchangeably promote the completion of germination in clematis vitalba seeds? Botany 2017, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Baskin, J.M.; Baskin, C.C.; Bu, H.; Du, G.; Ma, M. Effect of Diurnal Fluctuating versus Constant Temperatures on Germination of 445 Species from the Eastern Tibet Plateau. PLoS One 2013, 8, e69364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskin, J.M.; Baskin, C.C. A classification system for seed dormancy. Seed Sci. Res. 2004, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaeva, M. Factors controlling the seed dormancy pattern. 1977.

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Mimicking the natural thermal environments experienced by seeds to break physiological dormancy to enhance seed testing and seedling production. Seed Sci. Technol. 2022, 50, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, K.; Rix, M. Linum doerfleri: Linaceae. 2007.

- Rogers, C.M. The systematics of Linum sect. Linopsis (Linaceae). Plant Syst. Evol. 1982, 140, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diederichsen, A.; Richards, K. Cultivated flax and the genus linum L.: Taxonomy and germplasm conservation. Flax Genus Linum. [CrossRef]

- Mabberley, D. Mabberley’s Plant-book: a portable dictionary of plants, their classifications and uses. 2008.

- Tutin, T.G.; Heywood, V.H.; Burges, N.A.; Moore, D.M.; Valentine, D.H.; Walters, S.M.; Webb, D.A. Flora Europaea; University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolucci, F.; Peruzzi, L.; Galasso, G.; Alessandrini, A.; Ardenghi, N.M.G.; Bacchetta, G.; Banfi, E.; Barberis, G.; Bernardo, L.; Bouvet, D.; et al. A second update to the checklist of the vascular flora native to Italy. Plant Biosyst. - An Int. J. Deal. with all Asp. Plant Biol. 2024, 158, 219–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fois, M.; Farris, E.; Calvia, G.; Campus, G.; Fenu, G.; Porceddu, M.; Bacchetta, G. The Endemic Vascular Flora of Sardinia: A Dynamic Checklist with an Overview of Biogeography and Conservation Status. Plants 2022, 11, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, B.B.; Linder, C.R.; Mauseth, J.D.; Jansen, R.K.; Hillis, D.; Mcdill, J.R.; Dissertation, M.A. Molecular phylogenetic studies in the Linaceae and Linum, with implications for their systematics and historical biogeography. 2009.

- Lee Pengilly, N. Traditional food and medicinal uses of flaxseed. Flax Genus Linum 2003, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, G. Genetic variation and heritability for germination, seed vigour and field emergence in brown and yellow-seeded genotypes of flax. 2008.

- Stefanello, R.; Viana, B.B.; Das Neves, L.A.S. Germination and vigor of linseed seeds under different conditions of light, temperature and water stress. Semin. Agrar. 2017, 38, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, O. A predictive model for the effects of temperature on the germination period of flax seeds (Linum usitatissimum L.). Turkish J. Agric. For. 2012, 36, 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.E.; Kitchen, S.G. Life history variation in blue flax ( L inum perenne : Linaceae): seed germination phenology. Am. J. Bot. 1994, 81, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, A.; Bedini, G.; Müller, J. V.; Probert, R.J. Comparative seed dormancy and germination of eight annual species of ephemeral wetland vegetation in a Mediterranean climate. Plant Ecol. 2013, 214, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kırmızı, S.; Güleryüz, G.; Arslan, H. Effects of pretreatments on seed dormancy and germination in endemic Uludağ flax (Linum olympicum Boiss.) (Linaceae). Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2018, 59, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, T.L. Dormancy, Germination and Mortality of Seeds in a Chalk-Grassland Flora. J. Ecol. 1991, 79, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MILBERG, P. Germination ecology of the grassland biennial Linum catharticum. Acta Bot. Neerl. 1994, 43, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenu, G.; Cogoni, D.; Casti, M.; Bacchetta, G. Schede per una Lista Rossa della Flora vascolare e crittogamica Italiana: Linum muelleri Moris. Inf. Bot. Ital. 2012, 44, 405–474. [Google Scholar]

- Orsenigo, S.; Montagnani, C.; Fenu, G.; Gargano, D.; Peruzzi, L.; Abeli, T.; Alessandrini, A.; Bacchetta, G.; Bartolucci, F.; Bovio, M.; et al. Red Listing plants under full national responsibility: Extinction risk and threats in the vascular flora endemic to Italy. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 224, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porceddu, M.; Mattana, E.; Pritchard, H.W.; Bacchetta, G. Dissecting seed dormancy and germination in Aquilegia barbaricina, through thermal kinetics of embryo growth. Plant Biol. 2017, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, A.; Dessì, L.; Ucchesu, M.; Bou Dagher Kharrat, M.; Charbel Sakr, R.; Accogli, R.A.; Buhagiar, J.; Kyratzis, A.; Fournaraki, C.; Bacchetta, G. Seed germination ecology and salt stress response in eight Mediterranean populations of Sarcopoterium spinosum (L.) Spach. Plant Species Biol. 2019, 34, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavieres, L.A.; Arroyo, M.T.K. Seed germination response to cold stratification period and thermal regime in Phacelia secunda (Hydrophyllaceae): Altitudinal variation in the mediterranean Andes of central Chile. Plant Ecol. 2000, 149, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattana, E.; Pritchard, H.W.; Porceddu, M.; Stuppy, W.H.; Bacchetta, G. Interchangeable effects of gibberellic acid and temperature on embryo growth, seed germination and epicotyl emergence in Ribes multiflorum ssp. sandalioticum (Grossulariaceae). Plant Biol. 2012, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bewley, J.D.; Bradford, K.J.; Hilhorst, H.W.M.; Nonogaki, H. Seeds: physiology of development and germination. 2013.

- Thanos, C.A.; Kadis, C.C.; Skarou, F. Ecophysiology of germination in the aromatic plants thyme, savory and oregano (Labiatae). Seed Sci. Res. 1995, 5, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadis, C.; Georghiou, K. Seed dispersal and germination behavior of three threatened endemic labiates of Cyprus. Plant Species Biol. 2010, 25, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doussi, M.A.; Thanos, C.A. Ecophysiology of seed germination in Mediterranean geophytes. 1. Muscari spp. Seed Sci. Res. 2002, 12, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmés, J.; Medrano, H.; Flexas, J. Germination capacity and temperature dependence in Mediterranean species of the Balearic Islands. For. Syst. 2006, 15, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, B.; Pérez, B.; Torres, I.; Moreno, J.M. Effects of incubation temperature on seed germination of mediterranean plants with different geographical distribution ranges. Folia Geobot. 2012, 47, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grime, J.P.; Thompson, K. An apparatus for measurement of the effect of amplitude of temperature fluctuation upon the germination of seeds. Ann. Bot. 1976, 40, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, W.; Rave, G. The effect of cold stratification and light on the seed germination of temperate sedges (Carex) from various habitats and implications for regenerative strategies. Plant Ecol. 1999, 144, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, E.A.A.; Toorop, P.E.; Nijsse, J.; Bewley, J.D.; Hilhorst, H.W.M. Exogenous gibberellins inhibit coffee (Coffea arabica cv. Rubi) seed germination and cause cell death in the embryo. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porceddu, M.; Mattana, E.; Pritchard, H.W.; Bacchetta, G. Sequential temperature control of multi-phasic dormancy release and germination of Paeonia corsica seeds. J. Plant Ecol. 2016, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch-Savage, W.E.; Leubner-Metzger, G. Seed dormancy and the control of germination. New Phytol. 2006, 171, 501–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pignatti, S.; Menegoni, P.; Giacanelli, V. Liste rosse e blu della flora italiana; Agenzia Nazionale per la Protezione dell’Ambiente: Roma, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Angiolini, C.; Bacchetta, G.; Brullo, S.; Casti, M.; Giusso Del Galdo, G.; Guarino, R. The vegetation of mining dumps in SW-Sardinia. Feddes Repert. 2005, 116, 243–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porceddu, M.; Santo, A.; Orrù, M.; Meloni, F.; Ucchesu, M.; Picciau, R.; Sarigu, M.; Cuena Lombrana, A.; Podda, L.; Sau, S.; et al. Seed conservation actions for the preservation of plant diversity: the case of the Sardinian Germplasm Bank (BG-SAR). Plant Sociol. 2017, 54, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchetta, G.; Bueno Sanchez, A.; Fenu, G.; Jiménez Alfaro, B.; Mattana, E.; Piotto, B.; Virevaire, M. Conservación ex situ de plantas silvestres. Principado de Asturias. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchetta, G.; Belletti, P.; Brullo, S.; Cagelli, L.; Carasso, V.; Casas, J.L.; Cervelli, C.; Escribà, M.C.; Fenu, G.; Gorian, F. Manuale per la raccolta, studio, conservazione e gestione ex situ del germoplasma.; APAT, 2006; Vol. 37;

- Crawley, M.J. 2012.

- R Development Core Team R: a language and environment for statistical computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2013.

- Cuena-Lombraña, A.; Porceddu, M.; Dettori, C.A.; Bacchetta, G. Predicting the consequences of global warming on Gentiana lutea germination at the edge of its distributional and ecological range. PeerJ 2020, 2020, e8894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuena Lombraña, A.; Dessì, L.; Podda, L.; Fois, M.; Luna, B.; Porceddu, M.; Bacchetta, G. The Effect of Heat Shock on Seed Dormancy Release and Germination in Two Rare and Endangered Astragalus L. Species (Fabaceae). Plants 2024, Vol. 13, Page 484 2024, 13, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porceddu, M.; Fenu, G.; Bacchetta, G. New findings on seed ecology of Ribes sardoum: can it provide a new opportunity to prevent the extinction of a threatened plant species? Syst. Biodivers. 2017, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Df | Sum Sq | Mean Sq | F | pvalue | |

|

Treatment and Pre-Treatment (Tr) |

6 | 4.026 | 0.6711 | 36.916 | < 0.001 *** |

| Temperature (T) | 6 | 11.714 | 1.952 | 107.399 | < 0.001 *** |

| Tr * T | 36 | 3.243 | 0.090 | 4.956 | < 0.001 *** |

| C | C+W+C | CTR | DAR | Dark | W | |

| C+W+C | 1 | |||||

| CTR | 0.069 | < 0.001 *** | ||||

| DAR | < 0.05 * | < 0.001 *** | 1 | |||

| Dark | 1 | 0.253 | 0.737 | 0.317 | ||

| W | < 0.05 * | < 0.001 *** | 1 | 1 | 0.974 | |

| W+C | 1 | 1 | 0.074 | < 0.05 * | 1 | 0.106 |

| Df | Sum Sq | Mean Sq | F | pvalue | |

| Concentration (Co) | 3 | 1.154 | 0.384 | 19.127 | < 0.001 *** |

| Temperature (T) | 6 | 4.498 | 0.749 | 37.275 | < 0.001 *** |

| Co * T | 18 | 1.037 | 0.057 | 2.866 | < 0.001 *** |

| Treatment | Temperature | ||||||

| 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 25/10 | |

| CTR | - | - | 9±1 | 8±4 | 56±44 | - | 37±5 |

| W | - | 7±2 | 5±0 | 14±16 | 100±21 | 117±3 | - |

| C | - | - | - | 55±14 | 125±71 | - | - |

| W+C | - | - | 72±42 | 63±5 | - | - | - |

| C+W+C | - | - | 31±2 | 60±8 | - | - | - |

| DAR | - | 12±1 | 8±1 | 8±2 | 42±12 | - | 30±9 |

| GA3 250 mg/L | - | 16±1 | 8±1 | 6±0 | 15±5 | 32±6 | 14±3 |

| GA3 500 mg/L | 65±24 | 15±1 | 9±1 | 8±2 | 19±5 | 36±1 | 17±1 |

| GA3 1000 mg/L | - | 16±2 | 11±1 | 8±1 | 16±2 | - | 18±11 |

| Treatment and pre-treatment | Description |

| CTR | Light condition (12 h light/12 h dark) and incubation at all tested temperature |

| C | 3 months at 5°C |

| W | 3 months at 25°C |

| W+C | 3 months at 25°C, followed by 3 months at 5°C |

| C+W+C | 3 months at 5°C, followed by 3 months at 25°C, followed by 3 months at 5°C |

| DAR | 3 months at 25°C inside a sealed glass container with colour-changing silica gel at a ratio seed/silica gel of 1:1 which ensure the dry condition |

| 0/24 | 24 hours of dark condition and incubation at all tested temperature |

| GA3 | 0, 250, 500, 1000 mg/L GA3 in germination medium and incubation at all tested temperature |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).