1. Introduction

The growth of the human population and climate change, alongside a greater consumption of plant-based proteins, demand an increase in agro-industrial productivity and the search for innovative agricultural systems that maintain a social, environmental, and ecological balance [9,28]. Agroforestry systems have gained a leading role in the search for innovative agriculture with high productivity and environmental sustainability [39]. AFS is a variant of organic farming that associates food crops with trees sustainably [56]. Organic farming minimizes the use of agricultural pesticides and reduces cultivation costs [54]. Organic foods stand out for their low toxicity, increased shelf life, and higher nutrient content when compared to foods grown by the conventional approach.

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz), a proteic and starchy plant-based food, has been widely consumed globally and cultivated in tropical America for over 5000 years [58]. Cassava grown in an organic cultivation system has 10% to 20% more root yield and 28% more the net profit compared to a conventional cultivation system (C). In organic cultivation, cassava, here identified as just cassava, is of better quality, besides providing a higher dry matter, starch, crude protein, potassium, calcium, and magnesium content [55]. Starch from its roots is beneficial in preparing bakery products and food alternatives for individuals with gluten intolerance and those with celiac disease [2].

Unprocessed cassava has a maximum shelf life of 5 days due to deterioration reactions that begin a few hours after harvest. Traditional cassava fermentation, a pre-Colombian indigenous technology, increases the shelf life of the fermented product by up to a year [53]. In Brazil, traditional cassava fermentation is called "pubagem" [13]. In this process, the peeled or whole cassava are soaked in water and left to ferment for 24 to 96 h. This technique develops aroma and flavor characteristics, and acidity in the product. With a longer fermentation time, the product's acidity will be higher [14].

Fermentation also decreases toxic substances present in some cassava varieties [1,8]. The production process and the quality of traditional Puba have been widely studied in the past decades and are well described in the literature [4,15,38,48]. The physicochemical and nutrient contents of the product of anaerobic fermentation, "cassava silage" or as named here Puba 2, using the cassava cortex to reduce the by-products of the process, and organic or conventional cultivation, have not yet been studied. This process was first disclosed by the farmer and researcher Ernst Götsch [5].

This study aimed to standardize and improve the Puba 2.0 technique as an inexpensive and simple post-harvest cassava processing technique, to increase its shelf life in a resource-efficient method, and to offer different gluten-free and starchy products with prebiotic potential, improving and valuing traditional food habits

References should be numbered in order of appearance and indicated by a numeral or numerals in square brackets—e.g., [1] or [2,3], or [4–6]. See the end of the document for further details on references.

2. Materials and Methods

The variety of cassava used was "Cacau Amarela". Cassava roots were harvested from conventional (CCFS) and organic (COFS) farming systems. CCFS roots were acquired from a farm located in Teresópolis, Goiás, Brazil (16°29'13.9"S and 49°08'13.1"W). COFS roots were acquired from a farm situated in Goianira, Goiás, Brazil (16°29'04.9"S and 49°24'03.3"W).

The ensiling of the cassava mass was developed based on the principle of creating an anaerobic environment, well-described for animal consumption known by animal sillage, that occurs on other traditional foods like German Sauerkraut. The cassava roots were washed in fresh water, peeled, and grated. The resulting mass was pressed to reduce water content, sifted, transferred to glass jars with airtight lids, and fermented at room temperature (approximately 25 °C). The product resulting from the anaerobic fermentation was called "Puba 2" (about the traditional fermented cassava mass known as "puba"). The residues obtained at each stage were all weighed to calculate the yield of the Puba 2.0 processing technique.

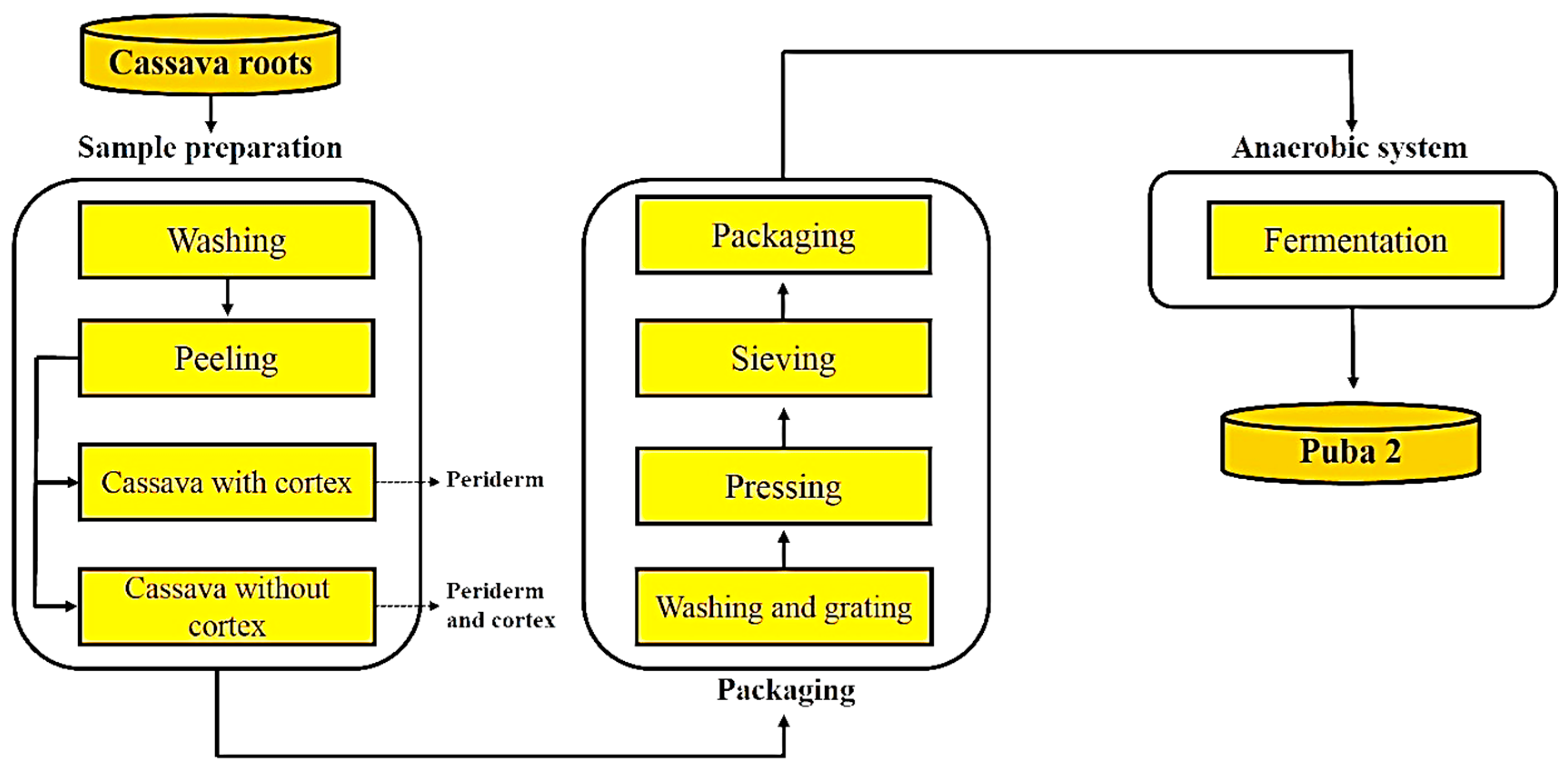

Figure 1 below presents a flowchart of the main steps used in producing Puba 2.0.

Initially, the stability point of fermentation (SPF) was determined, defined as the time required for the pH of the mass to begin stabilizing. In this experience, CCFS roots were used with and without cortex (CWC and CWOC, respectively), and subjected to 14 days of fermentation (Ft0 to Ft14). It was conducted in a randomized design, in a 2 x 14 factorial arrangement, with three repetitions.

In another experiment, in a 23 factorial design, with three replicates, the levels of the factors fermentation (fermented and non-fermented), cortex (with and without cortex), and cultivation system (CCFS and COFS) were combined, to study the effects on the physicochemical, microbiological, and paste characteristics of the Puba 2. Non-fermented treatments were named as follows: T1 – conventional, with cortex, non-fermented (CWU); T2 – conventional, without cortex, non-fermented (CWOU); T3 – organic, with cortex, non-fermented (OWU); and T4 – organic, without cortex, non-fermented (OWOU).

The fermented treatments (Puba 2) were obtained after reaching the time of fermentation stability for the respective masses of grated and pressed cassava (GCP), following the procedure outlined in

Figure 1. The samples were ensiled in 600 mL glass jars with screw caps, sealed to preserve the final weight of all replicates. After fermentation, the samples were placed in low-density polyethylene packaging and kept refrigerated at -20 °C for subsequent analysis of physicochemical, microbiological, and paste properties. After fermentation, the treatments were named as follows: T5 - conventional, with cortex, fermented (CWF); T6 - conventional, without cortex, fermented (CWOF); T7 - organic, with cortex, fermented (OWF); and T8 - organic, without cortex, fermented (OWOF).

To express the efficiency of this technique, considering the conversion rate of raw cassava in Puba 2, all the residues between steps were weighted. The fermentation yield was calculated after the final product was obtained, compared with the amount of GCP initially ensiled in the jars. It was measured from the mass of the liquid that overflowed through the lid during fermentation (Equation 1):

To obtain the Puba 2 conversion rate, a calculation compared the total GCP received concerning the initial weight of whole cassava, multiplied by the average fermentation yield (Equation 1) for each treatment (Equation 2), as not all the GCP was ensiled.

The nutrtional composition was determined according to official methods. The moisture was obtained by drying the sample at 105 °C until constant weight, method no. 935.29 [7]. The ash by burning organic matter in an indirect flame and calcination in a muffle furnace at 525 °C, method no 923.03 [7]. The crude fat, using petroleum ether as the solvent, method no. 2003.05 [7]. The total nitrogen by the micro–Kjeldahl method, with 5.75 as the nitrogen factor, to obtain the percentage of protein, method no. 960.52 [7]. The reducing sugars by the Lane–Eynon procedure using Fehling A and Fehling B reagents, method no. 923.09 [7]. The total sugars using acid hydrolysis and subsequent Lane–Eynon procedure, method no. 958.06 [7]. The starch by strongly acidic hydrolysis and following Lane–Eynon procedure, method no. 958.06 [7]. The soluble, insoluble, and total fiber according to the enzymatic-gravimetric method no. 991.43 [7]. The available carbohydrate content was calculated by difference (100 − moisture, ash, protein, lipid, and insoluble fiber). The energetic value was calculated considering Atwater factors, 4 kcal/g of available carbohydrate, 4 kcal/g of protein, 9 kcal/g of lipids, and 2 kcal/g of soluble fiber. The ascorbic acid (vitamin C) levels were determined by titration using the reagent 2,6-dichloroindophenol, method no. 967.21 [7].

Microbiological analyses were carried out by surface plating and incubation, according to official methodologies. The Escherichia coli count was done using method ISO 991.14 [7]. The coagulase-positive staphylococci, by method ISO 6888-1:1999 [30]. The presumptive Bacillus cereus, using method ISO 7932:2004 [31]. The total lactic acid bacteria count, by method ISO 15214:1998 [29]. The total count of molds and yeasts, using method no. 21527-2:2008 [32]. The detection of Salmonella sp. using method ISO 6579-1:2017 [33]. The identification of lactic acid bacteria was carried out using the methodology of High-sensitivity screening of the 16S rRNA gene, performed using a two-step PCR [16]. To increase the accuracy of the results, the hypervariable V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified with standard DNA polymerase. All microbiological results were verified according to RDC no. 331/2019 [11], a Brazilian norm for microbial food standards.

The samples were ground in a coffee grinder (Di Grano, Cadence, Balneário Piçarras, Brazil), up to 250 μm/60 mesh. The viscosity profile of the product was determined using RVA equipment (RVA 4500, Perten, Macquarie Park, Australia). The Standard Analysis 1 programming of the Thermocline for Windows software version 3.0 performed the analysis. The sample (2.5 g) was suspended in distilled water (±25 mL) and the moisture content was corrected to 14% in an RVA container. From the profile obtained by the RVA, pasting temperature, peak viscosity (maximum), breakdown viscosity, final viscosity, and setback viscosity were evaluated.

SPF data were submitted to analysis of variance (ANOVA), at the level of 5% probability, to verify the effects of cortex presence and fermentation time on the yield, pH, and titratable acidity of Puba 2 processing. When the interaction cortex presence × fermentation time was significant, regression analysis was applied to the third degree for fermentation time and the mean t-test for cortex presence [49]. Pearson correlation analysis was applied between the variable's pH and titratable acidity responses.

The results of physical-chemical, microbiological and paste characteristic in function of cassava farming system, cortex presence, and fermentation were submitted to ANOVA, at the level of 5% probability. When the interaction farming system × Cortex presence × fermentation was significant, ANOVA was applied, followed by Duncan's test.

The results were evaluated with the aid of Statistica software for Windows version 12.0.

3. Results

3.1. pH Curve

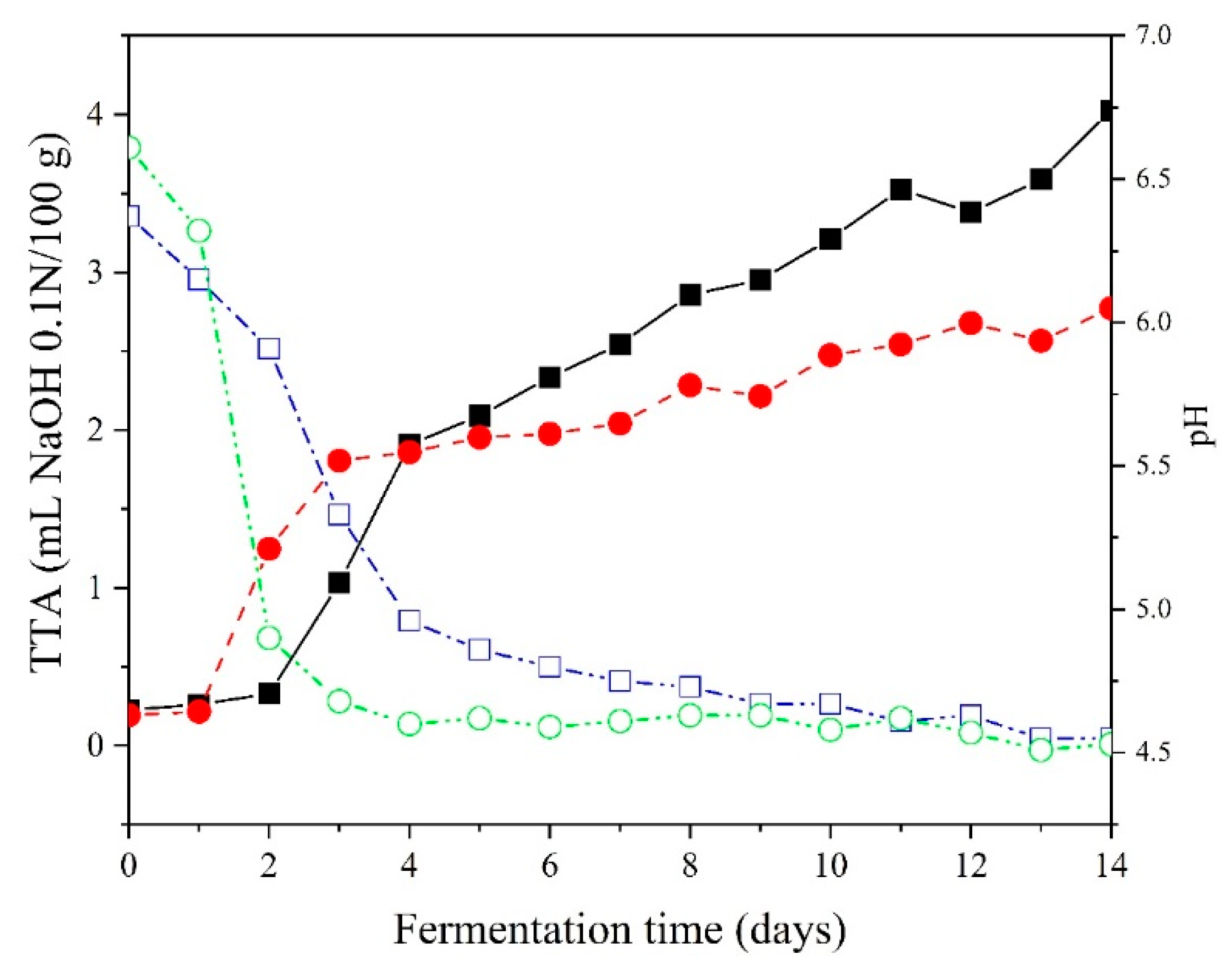

The pH curves started at a value of 6.5 (

Figure 2), followed by a decline to approximately 4.6 after the 4

th and 9

th days for SCSE and SCCE, respectively, indicating the stability point of the fermentation process. In this study, the ninth day was chosen to indicate the stability time of fermentation for both samples, thus eliminating the fermentation time effect. The Puba 2.0 obtained in this way exhibited pH and TTA (Total Titratable Acidity) values of 4.67±0.01 and 2.95±0.04 for SCSE, and 4.63±0.00 and 2.21±0.04 for SCCE, respectively.

3.2. Yield of Puba 2.0 Production

As expected, the treatments without cortex presented lower yields than those without cortex. The organic cultivar showed a higher yield, probably due to the lower moisture content caused by the different soil, planting, and harvest time conditions between the two cultivation systems (

Table 1).

3.3. Nutritonal Composition

In the general nutritional composition of Puba 2, the presence of cortex resulted in a significantly higher starch, moisture, dietary fiber, and protein content. The cassava cortex presented a higher content of insoluble fiber due to its starchy flesh, that is, the products without cortex offered a higher soluble fiber content. The concentration of ash and crude fat was close to zero in all samples. As for ash, the highest content was observed in the samples from the organic cultivation system (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

In the present work, the ascorbic acid (vitamin C) content increased significantly after fermentation with increments of more than 190% in organic cassava (

Table 3),

The content of reducing sugars decreased after fermentation, as expected in any fermented product. On the other hand, the starch content increased significantly after fermentation in all treatments.

The increased of starch content observed in all treatmests was close to the levels observed in pressed and crushed cassava before drying for flour production, the product most comparable to that produced in the present study (37.12 g/100 g) (Fernandes et al., 2013). The most probable reason is that the extravasation of liquid through the lid increased the starch concentration in the fermented samples; added to that, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) have a low capacity to hydrolyze starch (Jasko et al., 2011; Kostinek et al., 2005). Other studies that report the reduction of starch in fermented cassava samples soaked the roots in fresh water, so the starch was probably carried out with the wastewater as observed by Chisté and Cohen (2011) who reported the starch content of cassava before and after fermenting as 26.84 and 19.26 g/100 g, respectively.

3.4. Identification of Isolated Bacteria

The strains

Leuconostoc mesenteroides,

Lactococcus lactis, and

Lactococcus garvieae were identified from GCP and Puba 2 samples (

Table 4).

3.5. Termal Pasting Propierties

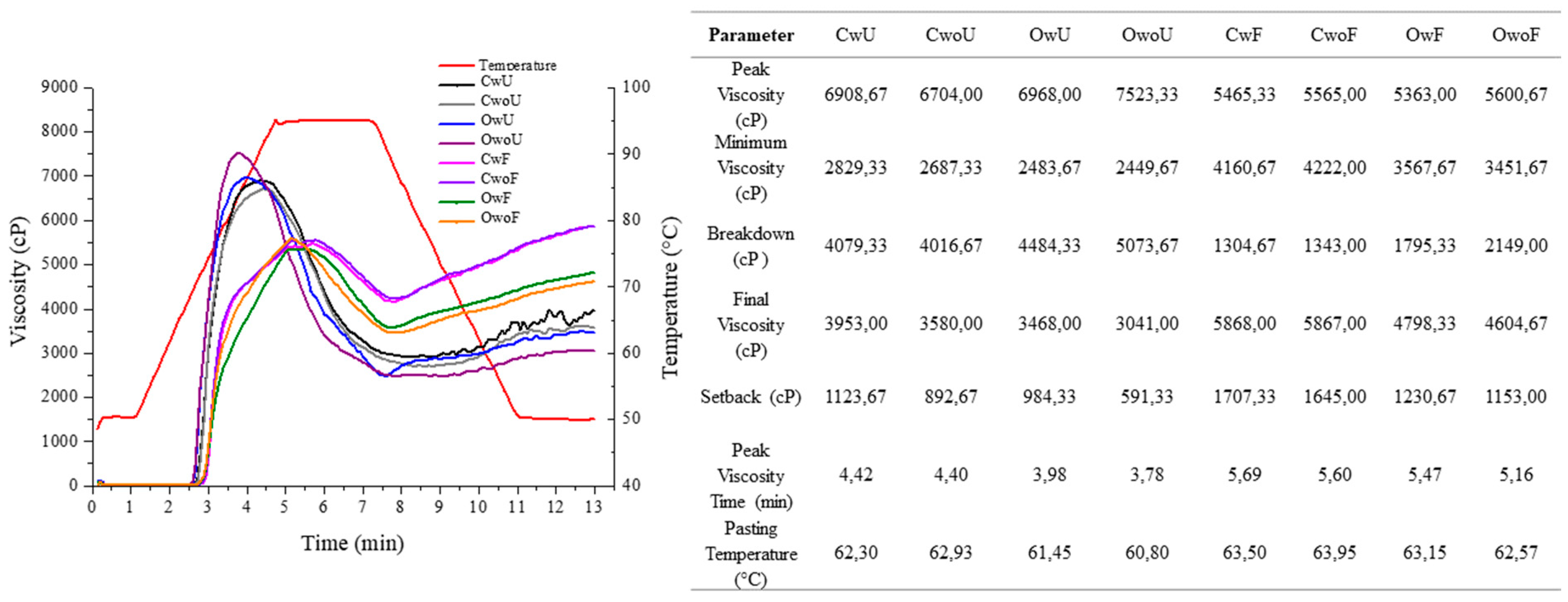

Figure 3.

Viscoamylogram for grated cassava pulp and Puba 2 treatments with values of parameters obtained in RVA analysis. CWU and CWF: conventional system, with cortex, unfermented and fermented, respectively. CWOU and CWOF: conventional system without cortex, unfermented and fermented, respectively. OWU and OWF: organic system with cortex, unfermented and fermented, respectively. OWOU and OWOF: organic system without cortex, unfermented and fermented, respectively.

Figure 3.

Viscoamylogram for grated cassava pulp and Puba 2 treatments with values of parameters obtained in RVA analysis. CWU and CWF: conventional system, with cortex, unfermented and fermented, respectively. CWOU and CWOF: conventional system without cortex, unfermented and fermented, respectively. OWU and OWF: organic system with cortex, unfermented and fermented, respectively. OWOU and OWOF: organic system without cortex, unfermented and fermented, respectively.

4. Discussion

Götsch qualitatively suggested the endpoint of fermentation for the development of Puba 2.0 (Vimio, 2021). The product was considered ready for consumption when the overflow of liquid from the fermentation jar ceased. In the present study, this event occurred after the fifth day, where the acidity curves intersected around 2 mL NaOH 0.1 N/100 g (

Figure 2). However, it increased towards the end of fermentation, with a higher value observed for SCCE (4 mL NaOH 0.1 N/100 g) compared to SCSE (3 mL NaOH 0.1 N/100 g). From these observations, it can be inferred that TTA (Total Titratable Acidity) is not a good indicator of stability, as the samples exhibit different acidity profiles due to the nature of their constituents (with and without peel), forming different types of metabolites generated by microbial activity during the fermentation of the cassava mass.

Based on these pH values, Puba 2.0 is classified as low-acidity food (JAY et al., 2005, FRANCO; LANDGRAF, 2008, Ray, 2004), making it more susceptible to microbial growth and, therefore, sensitive to spoilage. Therefore, it should be consumed on the same day or refrigerated for later consumption.

Nutritonal composition

In previous studies with separate parts of cassava, it has been reported that the bark (cortex and periderm) (1.05 g/100 g) has ten times the protein content of the starchy flesh (0.08 g/100 g), quadruple that of pressed and washed cassava (0.25), and twice as much as whole cassava (0.56 g/100 g) [21]. The presence of cortex increases the nutritional value of the product because it contains higher levels of protein and fiber, thus justifying its use and the reduction of solid residue.

The product may not be characterized as a "source of fiber"; nonetheless, its fiber content should not be disregarded.

The content of reducing sugars decreased after fermentation, as expected in any fermented product. Obi (2019), in his review, also confirmed this reduction in different substrates used in solid-state fermentation.

About the mineral composition (The concentration of ash and crude fat was close to zero in all samples. As for ash, the highest content, and therefore total minerals, was observed in the samples from the organic cultivation system (

Table 2 and

Table 3). This may indicate that more favorable farming conditions and soil management lead to a higher mineral concentration. The samples showed a similar crude fat content to that of "puba flour" (0.5 g/100 g), cassava starch (0.3 g/100 g) [42], and fermented cassava dough used to produce "cassava stick", a traditional Gabonese food (studied in 15 samples, ranging from 0.44 to 0.43 g/100 g)[41].

In vitmain C increase afeter fermentation can be justified by the higher growth of BAL with fermentation (Table 5).

The Puba 2 product has no standards in the Brazilian food legislation; however, in this work, Normative Instruction No. 23 [10] was used to classify Puba 2 as belonging to "Group II - Tapioca, Subgroup - Granulated – With no Type". This classification is important for further industrialization, as is establishes microbiological and physicochemical standards to work with.

The only sample that presented results above the limit established by Brazilian legislation was OWOUF, considering Bacillus cereus. The OWUF samples had a ten times greater development of B. cereus than their equivalent without fermentation, although within the permitted legislation. Both CWOUF and OWOUF showed higher counts of B. cereus colony-forming units (CFU). Bacteria are concentrated more in the inner pulp of cassava due to the greater availability of carbohydrates, as shown by higher counts for treatments without cortex. In addition, organic cultivation does not use chemical pesticides, which produces an environment favorable to the development of these microorganisms (Table 5).

It is noteworthy that all Puba 2 presented a lower microorganism count than equivalent grated cassava pulp, except for the desirable BAL. From this, the Puba 2 technique effectively reduces the count of B. cereus and molds and yeasts and is effective as a food preservative and pathogen control in cassava processing (Table 5).

Fermented products showed less deterioration, but non-fermented products had higher Bacillus cereus counts, which denotes greater contamination, which can be explained by transmission between soil, environment and food.

Table 5

Isolateted bacterias

Te strains bacterias indentified in the PUBA 2,0, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, beides the leucomostoc plantarium not indntifeid in Puba 2.0, were also also reported in "Gari", a fermented cassava product from West Africa [40], one of the closest products to Puba 2 reported in the literature.

Fermentation, as expected, increased the BAL count, and it was higher in samples from the organic system. The lower counts of pathogenic microorganisms in Puba 2 are probably related to the use of good manufacturing practices throughout the process of elaboration of GCP and Puba but also to the action of BAL that produces secondary metabolites such as hydrogen peroxide, diacetyl, and bacteriocins that act as bio preservatives [47].

However, some of the genomic sequences of the BAL isolated could not be identified due to the interference of MRS agar with the methodology used. There is a significant probability that these non-identified sequences are Lactobacillus strains since they are the most common strains reported in the literature for spontaneous cassava fermentation. Although the screening techniques on the 16S rRNA gene could not identify all genomic sequences in this case, it has been the most recently used in similar researches [3,17,18,20,22,25,43].

Thermal starch proprieeties

It is possible to infer that the higher starch concentration which occurred in fermented samples was responsible for the increase in the pasting temperature of Puba 2. The starch modification caused by fermentation increased the peak viscosity, as also observed in lotus tubers [59] (

Figure 3). In addition, the paste temperature was higher for cassava produced in a conventional system and fermented with and without shell than for the organic cassava with and without cortex, explained by the higher starch content of these samples.

The reduction of peak viscosity after starch modification in an acidic environment and of the values of the main parameters was also reported [19,50]. The reduction of breakdown and increased setback of Puba 2, which was expected, was also observed and demonstrated that all starch modifications significantly reduced breakdown [19].

These results indicate that Puba 2 has good characteristics as a baking ingredient; however, as the products tend to set back when cooled, they should be consumed while still hot so that they do not lose their viscoelasticity. This variable shows the potential of Puba 2 as an ingredient in the formulation of products that will undergo heating before consumption or as a thickener in products in which this setback characteristic is desirable.

5. Conclusions

The Puba 2 fermentation technique increased the acidity of the samples and reduced the pH, and proportionally due the moisture alteration, the soluble fiber content, and reducing sugars. On the other hand, it increased the content of vitamin C and starch. The samples with cortex had a significantly higher proportional content of protein, fiber, and moisture, which justifies keeping it while peeling cassava.

From a microbiological point of view, Puba 2 fermentation effectively reduced the count of contaminant microorganisms in all samples. It significantly increased the presence of LAB, with indicators of Lactococcus garvieae, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, and Lactococcus lactis strains, which have been reported in the literature as having probiotic potential. Cassava cultivated in an organic system presented higher BAL colonization, which resulted in more increased vitamin C biosynthesis.

Puba 2 fermentation also reduced peak viscosity, decreased the breakdown values, and increased the setback of the starch granules. This results in a more stable product when heated, which is desirable for bakery products and similar products. Increased retrogradation indicates that the product should be consumed while still hot.

The described Puba 2 technique is easily replicable, can be performed in places without electricity, and represents an effective way of preserving cassava. It does not require refrigeration or drying while the jars are closed. In addition, it can be adapted to industrial-scale to develop new fermented products with probiotic and prebiotic potential. This technique contributes to the food and nutritional security of populations that consume and grow cassava worldwide, especially in developing countries.

Author Contributions

Pedro Faria Lopes: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing-Original draft, Writing- Reviewing and Editing; Tânia Aparecida Pinto de Castro Ferreira: Data curation, Validation, Resources, Visualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing- Reviewing and Editing; Rodrigo Barbosa Monteiro Calvalcante: Resources, Writing Editing; Alline Emanuele Chaves Ribeiro: Methodology, Writing- Reviewing and Editing; Cíntia Silva Minafra e Rezende: Methodology, Writing Reviewing; Diego Palmiro Ramirez Aschieri: Resources, Supervision, Writing Reviewing and Editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Food Analysis Laboratory (LANAL) of the Faculty of Nutrition of the Federal University of Goiás – UFG – for supporting the work; the Laboratory Amazile Biagioni Maia (LABM) for the analysis of total, soluble, and insoluble dietary fiber; the Laboratory of Utilization of Agroindustrial Waste and By-Products (LABDARSA) of UFG for the analysis of viscosity profile – RVA; the Food Research Center (CPA) of School of Veterinary and Zootechnics (EVZ), Federal University of Goiás – UFG for microbiological quality analysis and isolation of lactic acid bacteria; and the NEOPROSPECTA Microbiome Technologies Laboratory for bacterial identification analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Adebiyi, J. A., Kayitesi, E., Adebo, O. A., Changwa, R., & Njobeh, P. B. (2019). Food fermentation and mycotoxin detoxification: An African perspective. Food Control, 106, Article 106731. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, P. V., & Villalobos, D. H. (2013). Harinas y almidones de yuca, ñame, camote y ñampí: propiedades funcionales y posibles aplicaciones en la industria alimentaria. Tecnología en Marcha. 25, i. 6, 37–45, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ahaotu, N. N., Anyogu, A., Obioha, p., Aririatu, L., Ibekwe, V. I., Oranusi, S., Sutherland, J. P., & Ouoba, L. I. I. (2017). Influence of soy fortification on microbial diversity during cassava fermentation and subsequent physicochemical characteristics of gari. Food Microbiology, Wageningen, 66, 165–172N: 10959998. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, P. F. Processamento e caracterização da puba. 1992. 134f. Tese (Doutorado em Tecnologia de Alimentos) - Faculdade de Engenharia de Alimentos, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 1992.

- Andrade, D., & Pasini, F., Mandioca – Uma receita. Rio de Janeiro, 2014. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rcOtHku5vF0. Accessed February 23, 2021.

- Andrade, D., Pasini, F., & Scarano, F. R. Syntropy and innovation in agriculture. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 45, 20–24, 2020.

- AOAC. (2019). Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Analytical Chemists (21st ed.). Association of Analytical Chemists, Gathersburg, MDUSA.

- Bechoff, A., Tomlins, K., Fliedel, G., Lopez-Lavalle, L. A. B., Westby, A., Hershey, C., & Dufour, D. (2017). Cassava traits and end-user preference: relating traits to consumer liking, sensory perception, and genetics. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 58, 4, 547–567. [CrossRef]

- Bel-Rhlid, R., Berger, R. G., & Blank, I. (2018). Bio-mediated generation of food flavors – Towards sustainable flavor production inspired by nature. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 78, 134–143. [CrossRef]

- Brasil (2005). Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento, Gabinete do Ministro. Instrução Normativa nº23 de 2005 - Regulamento técnico de identidade e qualidade dos produtos amiláceos derivados da raiz de mandioca, 1-7. https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/inspecao/produtos-vegetal/legislacao-1/normativos-cgqv/pOWUF/instrucao-normativa-no-23-de-14-de-dezembro-de-2005-derivados-da-raiz-da-mandioca-1/view.

- Brasil. (2019) Ministério da Saúde. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Resolução da Diretoria Colegiada – RDC nº 331 – Dispõe sobre padrões microbiológicos de alimentos e sua aplicação. Brasília, DF. Diário Oficial da União, ed.249, 1, 96. https://www.in.gov.br/web/dou/-/resolucao-rdc-n-331-de-23-de-dezembro-de-2019-235332272.

- Brasil. (2020). Ministério da Saúde. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Instrução Normativa – IN nº 75. Estabelece os requisitos técnicos para declaração da rotulagem nutricional nos alimentos embalados. Diário Oficial da União, ed. 195. 1, 113. https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/instrucao-normativa-in-n-75-de-8-de-outubro-de-2020-282071143.

- Cereda, M. P., & Vilpoux, O. (2010). Metodologia para divulgação de tecnologia para agroindústrias rurais: exemplo do processamento de farinha de mandioca no Maranhão. Revista Brasileira de Gestão e Desenvolvimento Regional, 6, 2, 219–250. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277212855_Metodologia_para_divulgacao_de_tecnologia_para_agroindustrias_rurais_exemplo_do_processamento_de_farinha_de_mandioca_no_Maranhao.

- Chisté, R. C., & Cohen, K. O. (2010). Caracterização físico-química da farinha de mandioca do grupo d’água comercializada na cidade de Belém, Pará. Revista Brasileira de Tecnologia Agroindustrial, Curitiba, 4, 1, 91–99. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/240822579_CARACTERIZACAO_FISICO-QUIMICA_DA_FARINHA_DE_MANDIOCA_DO_GRUPO_D'AGUA_COMERCIALIZADA_NA_CIDADE_DE_BELEM_PARA.

- Chisté, R. C., Cohen, K. O. (2011). Influência da fermentação na qualidade da farinha de mandioca do grupo d’água. Acta Amazônica, 41, 2, 279–284. [CrossRef]

- Christoff, A. P., Sereia, A. F. R., Boberg, D. R., Moraes, R. L. V. M., & Oliveira, L. F. V. (2017). Bacterial identification through accurate library preparation and high-throughput sequencing. Neoprospecta Microbiome Technologies, 25, 1–5. https://neoprospecta.s3.amazonaws.com/dOWUF/Neoprospecta+-+White+Paper+-+Bacterial+NGS+sequencing+2017.pdf.

- Díaz, A., Dini, C., Viña, S. Z., & García, M. A. (2018). Technological properties of sour cassava starches: effect of fermentation and drying processes. LWT - Food Science and Technology, 93, 116–123. [CrossRef]

- Elijah, A. I., Atanda, O. O., Popoola, A. R., & Uzochukwu, S. V. A. (2014). Molecular characterization and potential of bacterial species associated with cassava waste. Nigerian Food Journal, 32, 2, 56–65. [CrossRef]

- Falade, K. O., Ibanga-Bamijoko, B., & Ayetigbo, O. E. (2019). Comparing properties of starch and flour of yellow-flesh cassava cultivars and effects of modifications on properties of their starch. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization, 13, 4, 2581–2593. [CrossRef]

- Fekri, A., Torbati, M., Khosrowshahi, A. Y., Shamloo, H. B., & Azadmard-Damirchi, S. (2019). Functional effects of phytate-degrading, probiotic lactic acid bacteria and yeast strains isolated from Iranian traditional sourdough on the technological and nutritional properties of whole wheat bread. Food Chemistry, 306, October, Article 125620. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, H. R., Oliveira, D. C. R., Souza, G. S., & Lopes, A. S. (2013). Parâmetros de qualidade física e físico-química da farinha de mandioca (Manihot esculenta Crantz) durante processamento. Scientia Plena, 911, 1–9.

- Fleming, H., Fowler, S. V., Nguyen, L., & Hofinger, D. M. (2012). Lactococcus garvieae multi-valve infective endocarditis in a traveler returning from South Korea. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, 10, 2, 101–104. [CrossRef]

- Franz, C. M. A. P., Huch, M., Mathara, J. M., Abriouel, H., Benomar, N., Reid, G., Galvez, A., & Holzapfel, W. H. (2014). African fermented foods and probiotics. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 190, 84–96. [CrossRef]

- Gervin, V. M., Carolina, A., Sena, M., & Amante, E. R. (2016). Efeitos da modificação por ácidos orgânicos e do processo de secagem sobre as propriedades de expansão do amido de mandioca. Revista do Instituto Adolfo Lutz, 75:1693, 1–12. http://www.ial.sp.gov.br/resources/insituto-adolfo-lutz/publicacoes/rial/10/rial75_completa/artigos-separados/1693.pdf.

- Huch, M., Hanak, A., Specht, I., Dortu, C. M., Thonart, P., Mbugua, S., Holzapfel, W. H., Hertel, C., & Franz, C. M. A. P. (2008). Use of Lactobacillus strains to start cassava fermentations for Gari production. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 128, 2, 258–267, 2008. [CrossRef]

- IAL – Instituto Adolfo Lutz. (2008). Métodos físico-químicos para análise de alimentos (4th ed.). ISSN: 1098-6596. ISBN: 9788578110796. [CrossRef]

- Ibarruri, J., Cebrián, M., & Hernández, I. (2019) Solid State Fermentation of Brewer's Spent Grain Using Rhizopus sp. to Enhance Nutritional Value. Waste and Biomass Valorization, 10, 12, 3687–3700. [CrossRef]

- Ismail BP, Senaratne-lenagala L, Stube A, Brackenridge A. (2020). Protein demand: review of plant and animal proteins used in alternative protein product development and production. Anim Front, 10(4):53-63. [CrossRef]

- ISO (International Standardization Organization). (1998) ISO 15214:1998. Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs — Horizontal method for the enumeration of mesophilic lactic acid bacteria — Colony-count technique at 30 degrees ºC.

- ISO (International Standardization Organization). (1999). ISO 6888-1:1999. Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs — Horizontal method for the enumeration of coagulase-positive staphylococci (Staphylococcus aureus and other species) — Part 1: Technique using Baird-Parker agar medium.

- ISO (International Standardization Organization). (2004). ISO 7932:2004. Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs — Horizontal method for the enumeration of presumptive Bacillus cereus — Colony-count technique at 30 degrees ºC.

- ISO (International Standardization Organization). (2008). ISO 21527-2:2008. Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs — Horizontal method for the enumeration of yeasts and moulds — Part 2: Colony count technique in products with water activity less than or equal to 0,95.

- ISO (International Standardization Organization). (2017). ISO 6579-1:2017. Microbiology of the food chain — Horizontal method for the detection, enumeration and serotyping of Salmonella — Part 1: Detection of Salmonella spp.

- Jasko, A. C., Andrade, J., Campos, P. F., Padilha, L., Pauli, R. B., Quast, L. B., Schnitzle, E., & Demiate, I. M. (2011). Caracterização físico-química de bagaço de mandioca in natura e após tratamento hidrolítico. Revista Brasileira de Tecnologia Agroindustrial, 5, 427–441. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271183081_Caracterizacao_fisico-quimica_de_bagaco_de_mandioca_in_natura_e_apos_tratamento_hidrolitico.

- Kasaye, T., Melese, A., Amare, G., & Hailaye, G. (2018). Effect of fermentation and boiling on functional and physico chemical properties of yam and cassava flours. Journal of Agricultural Science and Food Research, 9, 4, Article 1000231, 2018. ISBN: 2519672927. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343530063_Effect_of_Fermentation_and_Boiling_on_Functional_and_Physico_Chemical_Properties_of_Yam_and_Cassava_Flours.

- Kostinek, M., Specht, I., Edward, V. A., Schillinger, U., Hertel, C., Holzapfel, W. H., Franz, & C. M. A. P. (2005). Diversity and technological properties of predominant lactic acid bacteria from fermented cassava used for the preparation of Gari, a traditional African food. Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 28, 6, 527–540. [CrossRef]

- Luna, A. T., Rodrigues, F. F. G., Costa, J. G. M., & Pereira, A. O. B. (2013). Estudo físico-químico, bromatológico e microbiológico de Manihot esculenta Crantz (mandioca). Revista Interfaces: Saúde, Humanas e Tecnologia, 1, 3. https://interfaces.leaosampaio.edu.br/index.php/revista-interfaces/article/view/15.

- Menezes, T. J. B., Sarmento, S. B. S., & Daiuto, E. R. (1998). Influência de enzimas de maceração na produção de puba. Ciência e Tecnologia de Alimentos. 18, 4, 386-390. [CrossRef]

- Miccolis, A., Peneireiro, F. M., Marques, H. R., Vieira, D. L. M., Arco-Verde, M. F., Hoffmann, M. R., REHDER, T., & Pereira, A. V. B. (2016). Restauração ecológica com Sistemas Agroflorestais: Como conciliar conservação com produção opções para Cerrado e Caatinga. (1st. ed.). Instituto Sociedade, População e Natureza – ISPN / Centro Internacional de Pesquisa Agroflorestal – ICRAF, 2016.

- Mokoena, M. P., Mutanda, T., & Olaniran, A. O. (2016). Perspectives on the probiotic potential of lactic acid bacteria from African traditional fermented foods and beverages. Food and Nutrition Research, 60, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Muandze-Nzambe, J. U., Guira, F., Cisse, H., Zongo, O., Zongo, C., Djbrine, A. O., Traore, Y., & Savadogo, A. (2017). Technological, biochemical, and microbiological characterization of fermented cassava dough use to produce cassava stick, a Gabonese traditional food. International Journal of Multidisciplinary and Current Research, 5,808–817. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318492709_Technological_biochemical_and_microbiological_characterization_of_fermented_cassava_dough_use_to_produce_cassava_stick_a_Gabonese_traditional_food.

- NEPA - Núcleo de Estudos e Pesquisas em Alimentação. (2007). Tabela Brasileira de Composição de Alimentos – TACO. (4th ed.). Universidade Estadual de Campinas – UNICAMP Campinas, SP, 2007. ISSN: 16248597. ISBN: 1578810728. http://www.unicamp.br/nepa/taco/.

- Nicolau, A. I. (2016). Safety of Fermented Cassava Products. In V. Prakash, O. Martin-Belloso, L. Keener, S. Astley, S. Braun, H. Mcmahon & H. Lelieveld. (Eds.), Regulating Safety of Traditional and Ethnic Foods (pp. 319-335). Elsevier Inc. [CrossRef]

- Ndam, Y. N., Mounjouenpou, P., Kansci, G., Kenfack, M. J., Meguia, M. P. F., Eyenga, N. S. N. N., Akhobakoh, M. M., & Nyegue, A. (2019). Influence of cultivars and processing methods on the cyanide contents of cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) and its traditional food products. Scientific African, 5, 1-8, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Njoku, V. O. & Obi, C. (2010). Assessment of Some Fermentation Processes of Cassava Roots. International Archive of Applied Sciences and Technology, 1, 20–25. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266069352_Microbiological_safety_and_quality_assessment_of_some_fermented_cassava_products_lafun_fufu_gari.

- Obi, C. N. (2019). Solid state fermentation: substrates uses and applications in biomass and metabolites production - A Review. South Asian Research Journal of Biology and Applied Biosciences, 1, 1, 20–29. [CrossRef]

- Penido, F. C. L., Piló, F. B., Sandes, S. H. C., Nunes, A. C., Colen, G., Oliveira, E. S., Rosa, C. A., & Lacerda, I. C. A. (2018). Selection of starter cultures for the production of sour cassava starch in a pilot-scale fermentation process. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology, 49, 4, 823–831. [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, F. A., Oliveira, S. M. G., & Damasceno, M. J. R. (2001). Processamento da farinha carimã. Instruções Técnicas - Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária Embrapa - Ministério de Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento, 38 dez, 1-3. https://ainfo.cnptia.embrapa.br/digital/bitstream/CPAF-AC/15595/1/it38.pdf.

- Pimentel-Gomes, F. (2000) Curso de estatística experimental. (12 ed.) São Paulo: FEALQ.

- Qi, Q., Hong, Y., Zhang, Y., Gu, Z., Cheng, L., Li, Z., & Li, C. (2019). Combinatorial effect of fermentation and drying on the relationship between the structure and expansion properties of tapioca starch and potato starch. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 145, 965-973. [CrossRef]

- Salami, O. S., Akomolafe, O. M., & Olufemi-Salami, F. M. (2017). Fermentation: A Means of Treating and Improving the Nutrition Content of Cassava (Manihot esculenta C.) Peels and Reducing Its Cyanide Content Salami. Genomics and Applied Biology, 8, 3, 17–25. [CrossRef]

- Santos, T. P. R., Sartori, M. M. P., & Cabello, C. (2012). Relação entre tempo de exposição e concentração de ácido lático nas características de expansão do amido de mandioca modificado. Revista Raízes e Amidos Tropicais, 8, 27–35. https://energia.fca.unesp.br/index.php/rat/article/view/1067.

- Shah, N. N., & Singhal, R. S. (2017). Fermented Fruits and Vegetables. In A. Pandey, M. A. Sanromán, A. Maria, G. Du, C. R. Soccol, C-G. Dussap, (Eds.). Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering: Food and Beverages Industry. (pp. 45–89). Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Suja, G., & Jaganathan, D. (2020). Organic farming for sustainable production of tropical root crops. Kerala Karshakan, 8, 4, 1-9. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344685340_Organic_farming_for_sustainable_production_of_tropical_root_crops.

- Suja G., Santhosh-Mithra, V. S., Sreekumar, J., & Jyothi, A. N. (2014). Is organic root production promising? Focus on implications, technologies and learning system development. Poster session presentation at the meeting Organic World Congress - 4th ISOFAR Scientific Conference. 'Building Organic Bridges' https://orgprints.org/23666/1/23666%20SujaRevisedpaper%20OWC14_MM.pdf.

- Uddin, M. N., & Bari, L. (2019). Governmental policies and regulations including FSMA on Organic Farming in the United States and around the globe. In D. Biswas, & S. A. Micallef, (Eds.). Safety and Practice for Organic Food. (pp. 33-62). [CrossRef]

- Versino, F., López, O. V., & García, M. A. (2015). Sustainable use of cassava (Manihot esculenta) roots as raw material for biocomposites development. Industrial Crops and Products, 65, 79–89. [CrossRef]

- Vilpoux, O. F., Guilherme, D. O., & Cereda, M. P. (2017). Cassava cultivation in Latin America. In C. HERSHEY (Ed.). Achieving sustainable cultivation of cassava. (pp. 149-174). Cambridge: Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing Limited. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318868830_Cassava_cultivation_in_Latin_America.

- Zhang, F., Liu, M., Mo, F., Zhang, M., & Zheng, J. (2017). Effects of acid and salt solutions on the pasting, rheology and texture of lotus root starch–konjac glucomannan mixture. Polymers, 9, 12,1-14. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).