1. Introduction

The recent strategies for prevention or delay of non-communicable diseases, related to oxidative stress, such as obesity, cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, have led to an increasing interest in the development of functional foods, designed to target reduce the oxidative status and inflammation [1, 2]. In this sector, numerous vitro, animal and clinical studies highlight the beneficial effect of fermented foods, possessing significant antioxidant, anti-hypertensive, anti-inflammatory and hypolipidemic activities [

3]. Khayatan et al. unveiled that including fermented foods in the daily diet may improve several clinical outcomes, which are aligned with the reported properties [

3].

Among these, miso, a traditional Japanese sauce, which is prepared by fermented soy bean paste [

4] have been extensively studied for its possible preventive role against oxidation and inflammation [

5], mainly attributed to the metabolic activity of microorganisms, which during fermentation process produce bioactive peptides, increasing the bio-availability of phenolic compounds and inhibiting digestive enzymes activity [

6]. Additionally, these microorganisms are known to increase the bio-accessibility of crucial isoflavones, leading to improved lipid management, as well as to reduced inflammation and oxidative status [

1]. Consumption of fermented soy foods, including miso, possess a regulatory role on concentrations of inflammatory markers, mainly Interleukin-6 (IL-6), but also on C-Reactive Protein (CRP) and Interleukin-18 (IL-18) levels, reinforcing their healthful impact [

1]. Evidence also supports that miso consumption may inhibit the growth of certain tumors, including those affecting the stomach, colon, liver, and lungs, in animal studies. It has been also associated with better management of hypertension, reduced insulin resistance, suppressed visceral fat, and reduced lipid accumulation in the liver [

4,

7].

Our previous clinical study introduced the evaluation of the acute metabolic effect of a novel miso-type sauce, enhanced with bio-carotenoids derived from fruit by-products, at the postprandial state [

8]. Bio-carotenoids and polyphenols recovered from fruit by-products have been assessed to synergistically enhance the activity of novel miso against oxidative stress and inflammation. It has been suggested that hydrolytic enzymes produced during the fermentation process on substrates such as barley, wheat and rice bran may further enhance the bioactivity of the final product [

8]. The findings of the previous postprandial dietary intervention indicated that consumption of a high-fat, high-carbohydrate meal, which causes acute oxidative stress, containing the functional miso sauce, can increase plasma total antioxidant capacity (TAC) in humans [

8].

Furthermore, there are indications that daily miso consumption may reduce insulin resistance in women [

9]. The hypocholesterolemic role of miso is demonstrated in a 9-month follow-up, where daily intake of 50g of miso by non-vegetarian premenopausal women, it seems capable of leading to a reduction in total cholesterol values [

10]. Although the evidence supports that habitual consumption of miso soup may not significantly alter the HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose and uric acid levels in diabetic men and women [

7], this pilot clinical study extends the evaluation of the acute, metabolic effect of the novel miso-type sauce, enhanced with bio-carotenoids from fruit by-products [

8].

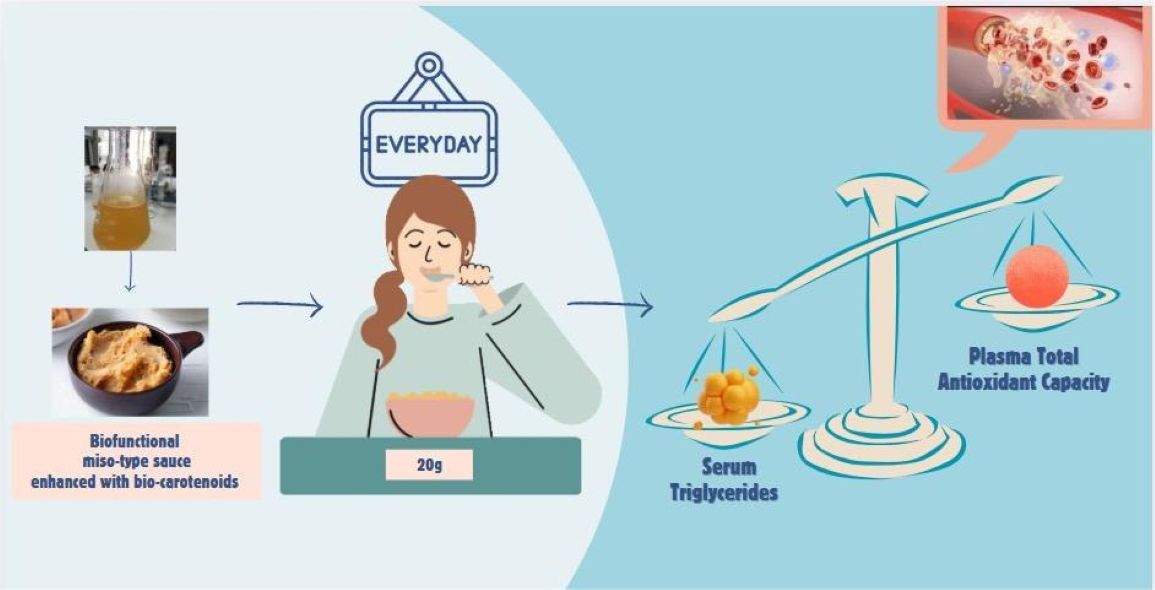

Therefore, the aim of the present pilot cross-over clinical study was to further investigate the effect of the habitual consumption of the bio functional miso-type sauce, enhanced with bio-carotenoids on lipidemic, glycemic and oxidative biomarkers, in healthy volunteers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This pilot clinical study was a cross-over, randomized and single-blind nutritional intervention, conducted from November 2021 to January 2022, at the Laboratory of Nutrition and Public Health of the University of the Aegean (Lemnos, Greece). The study was also carried out following the recommendations of Declaration of Helsinki, 2013

[11]. The Ethics Committee of the University of the Aegean approved the trial protocol (IRB No. 10/30.09.2021).

2.2. Participants

Participants were randomly recruited from Lemnos, Greece through social media invitations. Potential volunteers were initially screened for their medical and nutritional histories, and the biochemical and anthropometric profiles. Anthropometric assessment (height, body weight body composition) was carried out using a body composition analyzer (Tanita SC 330, TANITA EUROPE B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and biochemical evaluation was completed by showing recent (quarterly) biochemical test results. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Individuals whose age is over 18 years (2) and provide a signed, informed consent. Cases with age <18 and >65 years, abnormal biochemical and hematological parameters, dietary supplementation (antioxidants, vitamins, minerals) or medication intake, chronic diseases (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, malignancies, liver disease, iron deficiency anemia), heavy smoking (>10 cigarettes/day), consumption of >40 g alcohol/day, and inability to give consent were excluded.

All participants who met the inclusion criteria were provided with a detailed explanation of the protocol and signed an informed consent form.

2.3. Group assignment

This trial used single blinding methodology, where researchers were blinded to group allocation. During each trial period, volunteers were randomly and equally assigned to one of two experimental groups: Control group or Miso group, using a concealed simple randomization process, ensuring they were unaware of their group assignment. Participants crossed over from the one study arm to the other. In each trial period, individuals who joined the Control group consumed the control sauce, and those who were assigned to the Miso group received the interventional, miso-type sauce.

2.4. Experimental sauces composition

In the study two different types of sauce were investigated:

- (A)

Control sauce: legume-based, made from 50% Greek legume paste (a 1:1 ratio of Afkos and chickpeas), combined with 50% boiled water.

- (B)

Miso-type sauce: the novel sauce from fermented Greek legumes, enhanced with bio-carotenoids. It was created by fermenting a blend of cereal by-products and chickpeas (50% of total weight) with 0.05% (w/w) Aspergillus oryzae spores. This innovative sauce was further enhanced with a fruit by-product extract, comprising 42.5% of the total formulation. The extract is a combination of carrot (30%), orange (30%), apple (20%), banana (10%), and kiwi peel (5%) extracts, making it particularly rich in carotenoids.

The preparation processes and composition of the test sauces have been previously described

[8].

Table 1. demonstrates the nutritional values of the trial sauces. Notably, the interventional, miso-type sauce offers significant nutritional advantages over the control sauce, providing an additional 56.2 mg of total phenolics and 48.14 mg of total carotenoids, per daily portion (20g).

2.5. Experimental design

The nutritional intervention was performed in total two monthly periods (one month consuming the interventional or the control souse) using a randomized cross-over design, with a 1-washout week. Volunteers were instructed to maintain their usual diet and physical activity throughout each trial period, with only the addition of the allocated sauce to their intake. They were also requested to inform the evaluators in case of taking any emergency medication for health reasons, throughout the trial periods. Preservation instructions were also given for the trial sauces.

The participants subsequently received 30 daily portions of 20 g each, of control or miso-type sauces. These were administered in a random order and efficiently provided in ID-labeled, ready-to-eat plastic containers, in respect to single-blinding and the avoidance of any participant bias. Volunteer compliance was monitored on a weekly basis through direct telecommunication. Typically, during these calls, a 24-hour dietary recall was recorded to ensure that volunteers were adhering to the research guidelines (data not shown).

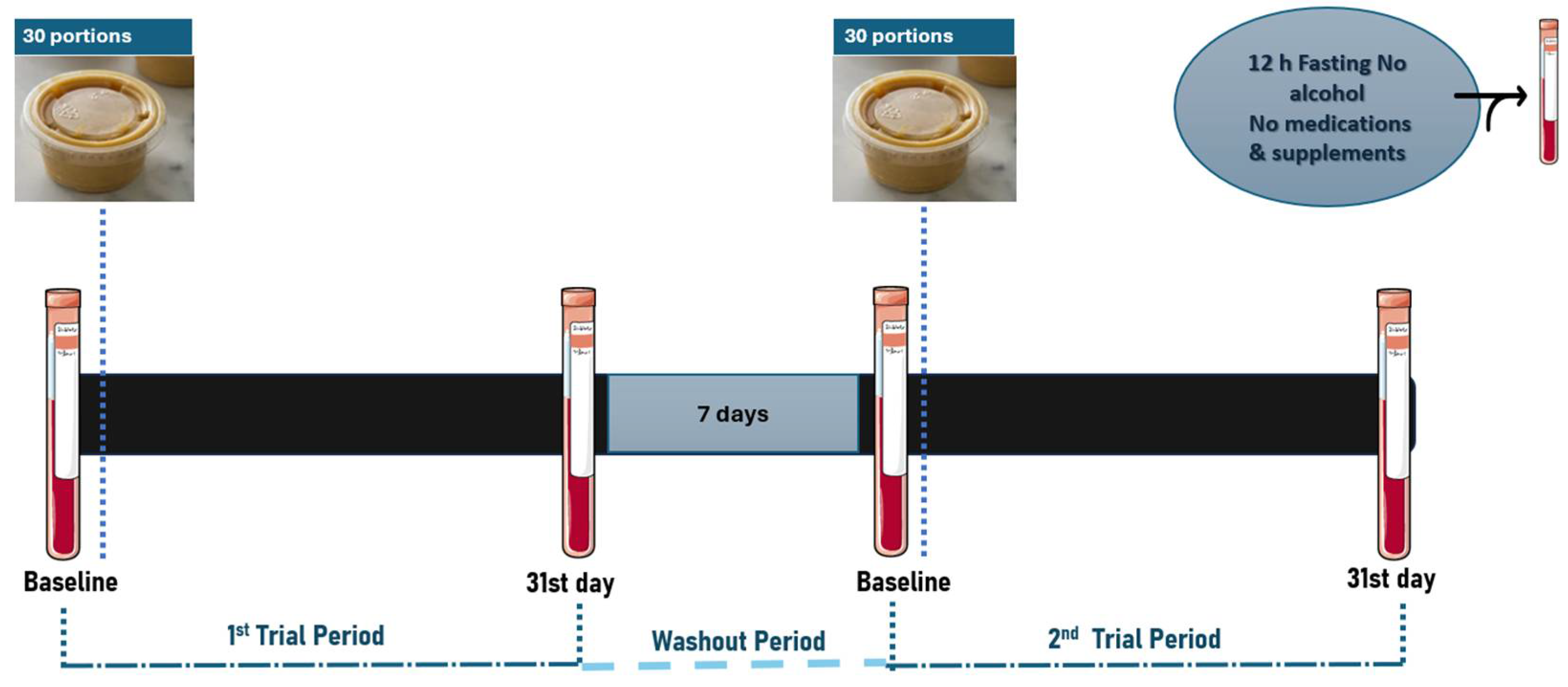

Each volunteer attended at the fasting state, the Laboratory of Human Nutrition and Public Health (Department of Food Science and Nutrition, University of the Aegean) during the following days of each trial period: (1) Before taking any dietary regimen (Baseline) (2) On the 31st day after following the outset of the respective dietary regimen. Prior to each blood collection visit, they were asked to follow a 12-hour fasting and to abstain from alcohol, caffeine, medicators, and dietary supplements for 12 hours. A dietary 24-hour recall (once a visit) was also collected to ensure compliance with these instructions (data not shown).

Blood samples (10 mL) were drawn by collaborating doctors. Serum was obtained from clot activator tubes, and plasma was collected in EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) tubes (Weihei Hongyu Medical Devices Co., Ltd, Weihai, China) before centrifugation at 3000 rpm, 4

ο C, 15 min, using a tabletop high-speed refrigerated centrifuge (Thermo Scientific ST16R, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The serum and plasma samples were kept at -40

o C, until analysis. Serum total-, High Density Lipoprotein- (HDL-), Low Density Lipoprotein- (LDL-) cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, and uric acid, were assessed, using an automated biochemical analyzer (COBAS c111, Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Plasma total antioxidant capacity (TAC) was evaluated by FRAP assay, as previously described by Chusak et al.

[12]. Baseline measurements were repeated at the 4-week follow-up visit, for each interventional period.

An overview of the visit procedures of the pilot clinical study visits is presented in

Figure 1.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The sample size for this long-term nutritional intervention was based on prior studies. To achieve a statistically significant level (p < 0.05), it was estimated that 10 participants were adequate to detect a plasma antioxidant capacity difference of 0.77 ± 0.42 mmol/L between the experimental groups, ensuring a statistical power of 95% at 95% confidence level. Accounting for an anticipated 15% drop out rate, 12 subjects were enrolled.

Statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS V21.0 software for Windows (IBM Corporation, New York, NY, USA). The mean age of volunteers, the anthropometric and body composition values and the biochemical results are mentioned as Mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) with significance set at p<0.05. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to evaluate normality. One-way Anova tests examined the variability of the initial characteristics between men and women. Repeated Anova Measures were performed to test the group, time, and group by time interaction effects on metabolic biomarker responses, followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests. The statistical significance of changes from baseline to 30-days follow-up was evaluated by within-group two-tailed samples t-test. (within-group variation).

4. Discussion

Maintaining cardiovascular and metabolic health is related to many dietary and lifestyle factors, including maintenance of healthy lipidemic and glycemic profile, as well as the oxidative balance [

13]. Lifestyle options, such as the inclusion of traditionally fermented soy products, have been suggested as practical tools to address these oxidative and inflammatory issues, related to chronic diseases [

4]. In this context, miso intake has been inversely associated with cardiovascular risk in women [

14], while daily miso consumption for 9 months has been demonstrated to improve the profile of cholesterolemia [

10].

Furthermore, implementing sustainable practices to enhance such foods may provide additional health benefits. Fruit by-product extracts appear to enhance the antioxidant profile of fermented foods, leading to a synergistic activity [15, 16]. Our previous clinical study, investigating the acute effect of a miso-type sauce, enhanced with a carotenoid-rich extract from fruit by-products, in metabolic biomarkers [

8]. The findings were highlighted by the postprandial improvement of total plasma antioxidant capacity, serum lipidemic profile (triglycerides, LDL-cholesterol) and platelet aggregation, in healthy humans, after following a high fat- and carbohydrates-meal with the novel miso-type sauce [

8].

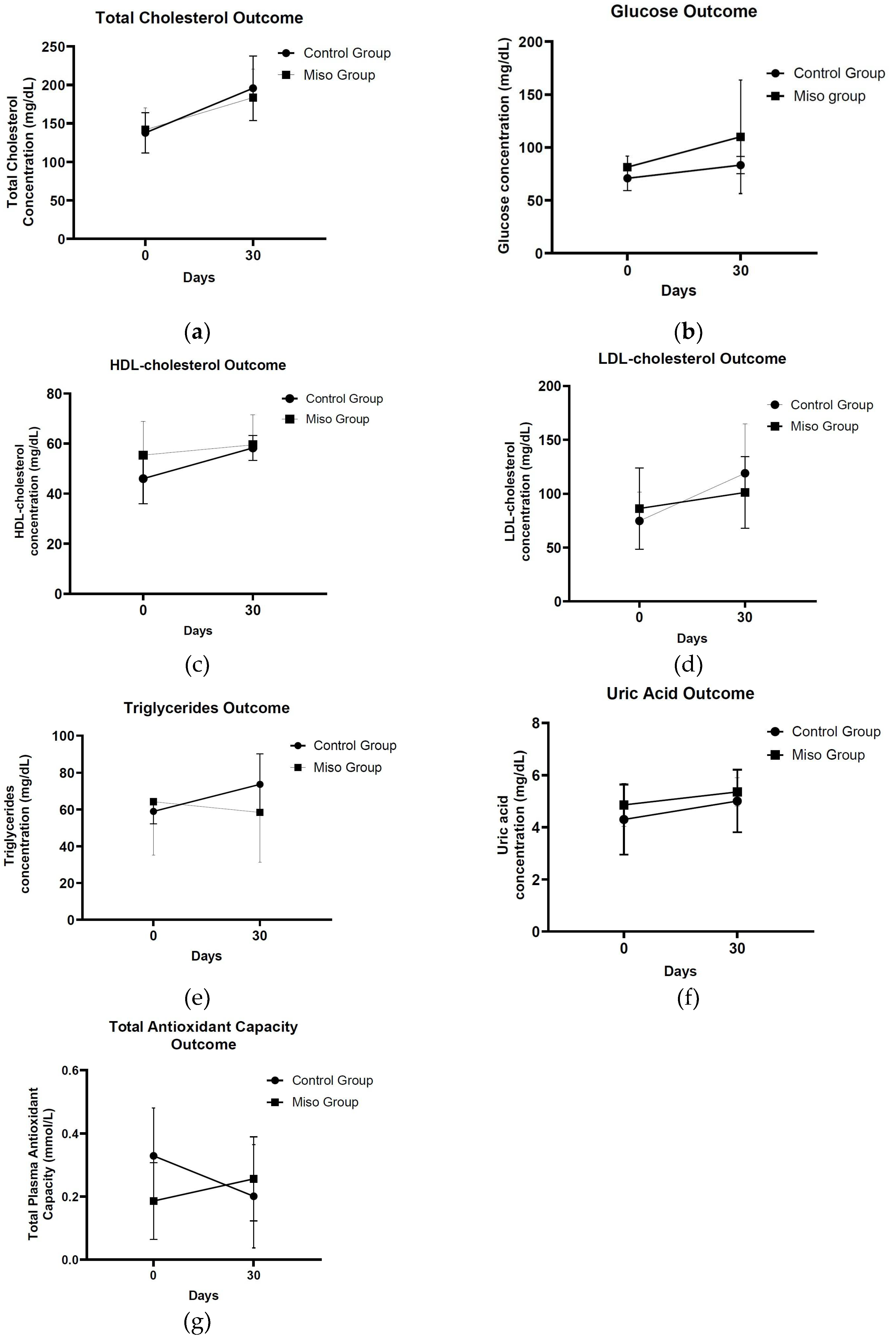

This pilot nutritional intervention-clinical study investigated the effect of the habitual consumption of the innovative bio functional miso-type sauce, enhanced with bio-carotenoids, on inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers. The nutritional intervention shown that the daily consumption of the bio-functional miso-type sauce for 30 days, in the context of the usual diet, led to increased plasma total antioxidant capacity among healthy participants, compared with the adverse effects observed after the control sauce consumption. This finding is fully consistent with those of acute dietary intervention [

8]. Although postprandial metabolism appears to be directly affected by the presence of antioxidant components in the context of a high-fat, high-carbohydrate meal, it is likely that this effect is maintained during long-term intake. The role of miso as a free-radical scavenger is mainly related to the improvement of the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging ability, as confirmed by Hashimoto and colleagues [

17]. There is evidence that habitual miso soup consumption may reduce Renin-Angiotensin System (RAS) activation and oxidative stress, which are related with the pathogenesis of hypertension [

18]. However, there are no clinical studies exploring the exact effect of daily miso intake on parameters of oxidative damage.

The demonstrated findings may be attributed to the antioxidant activity of isoflavones, presented in the bio-functional, fermented sauce. Evidence supports that biotransformation with microorganisms, including

Aspergillus sp., may improve β-glucosidase activity, increasing the isoflavone aglycone content [

19] . The potent antioxidant activity of isoflavones has been noted to be exerted in both lipophilic and aqueous phases. It is noteworthy that the bioavailability of isoflavones in the form of aglycone, and by extension the degree of ROS reduction, is also dependent on the bioavailability of phytochemicals [

20]. In vitro studies on similar fermented products, such as tempeh, indicate that during prolonged fermentation process,

Aspergillus oryzae may exert proteolytic activity, leading to the production of bioactive peptides and amino acids, which are also bioavailable and may enhance the overall antioxidant activity of the product [

20]. Furthermore, there are indications that this bioprocess may release antioxidant compounds derived from fruit by-product extracts, such as polyphenols and carotenoids, and enhance their biological activity [

16].

Numerous observational studies indicate that increased concentrations of circulating carotenoids are negatively associated with markers of oxidative stress. The main mechanism describing the effect of carotenoids on oxidative markers is through inhibition of lipid and singlet oxygen peroxidation [

21]. It seems that bio-carotenoids, which were used for miso-type sauce enhancement, are likely bioavailable, exerting a synergistic effect on the overall antioxidant effect. Based on these data, this pilot nutritional intervention should further highlight the effectiveness of fruit by-products valorization, as a sustainable strategy for the enhancement of functional foods with valuable bio-carotenoids, to address public health concern on oxidative stress and inflammation indicators [

22].

Moreover, the results suggest beneficial impact of the daily consumption of the novel, miso-type sauce, enhanced with bio-carotenoids from fruit by-products on the lipidemic profile of the participants. Specifically, the experimental miso-type sauce induced a reduction in triglycerides levels, compared to the opposite effect, obtained after habitual consumption of the control sauce. This finding is in line with the results obtained by the previous, acute clinical study. Additionally, both sauces increased the concentrations of LDL-cholesterol at the endpoint, but following the miso group these values were slightly lower than following the control group. Consistent with the previous data, derived from the clinical intervention on postprandial metabolic effects, it seems that the consumption of 20g bio-functional miso-type sauce/day, followed-up over 1 month, confirms the hypolipidemic effect which was found at the acute level [

8].

Similar biological impacts have been mentioned in clinical research, investigating the influence of such fermented foods on cholesterolemia biomarkers. Santacroce et al. has been evaluated that Jang intake (a korean fermented soybean paste) in a dose response ≥1.9 g/day, is inversely associated with parameters of Metabolic Syndrome, including hypo- HDL-cholesterolemia, after adjusting for covariates including sodium intake [

23]. In a 12-week human intervention, the habitual intake of kochujang, an

Aspergillus oryzae-fermented red pepper paste, has been demonstrated to effectively reduce the LDL- and total cholesterol levels, in hypercholesterolemic participants [

24]. The role of isoflavones in lipid metabolism has also been studied. The scientific community supports that the presence of genistein may affect thermogenesis and lipid accumulation, leading to reduced production of LDL-lipids, triglycerides and free fatty acids [

19].

Bioactive peptides isolated from chickpeas, as a raw material in the test sauces, have been stated to significantly reduce serum total cholesterol, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels, in the context of a high-fat diet [25, 26]. In addition to isoflavones, the increased content of proteins and peptides in the bio-functional, miso-type sauce, may synergistically exert higher bioactivity, contributing to the demonstrated lipid-lowering effect [

2]. Notably, recent reports indicate that Monacolin K, a secondary metabolite produced by

Aspergillus species, may attenuate cholesterol biosynthesis by inhibiting the activity of the enzyme 3-hydroxy-2 methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMG-CoA reductase). Through this mechanism, it may contribute to lipid profile improvement [

27].

Additionally, the results from the present study revealed no differences in total cholesterol levels between the two trial groups, in this time frame. Limited clinical trials have currently investigated the effectiveness of habitual miso intake over longer periods, on biomarkers of lipemia. There is evidence that the intake of 50 g of miso soup/day (45 mg of conjugated isoflavones) for 9 months, may reduce total cholesterol concentrations in vegetarian premenopausal women [

10]. However, in this pilot intervention the degree of increase in HDL-cholesterol was observed to be significantly milder in the miso group, compared to the percentage increase that occurred in the control group. It could be argued that HDL-cholesterol as a single biomarker can be altered by specific dietary factors and lifestyle parameters. Studies suggest that both increasing olive oil and nut intake, and physical activity may lead to improved HDL-cholesterol levels [

28], but data are limited on the effect of such functional food as the novel miso-type sauce on these concentrations. Based on recent documentations, the triglycerides/HDL-cholesterol ratio have been reported as a remarkable indicator of insulin resistance. In fact, Takahashi et al. did not detect any association between habitual miso soup intake and this marker [

29], mentioning the miso type as a variability parameter, when assessing its impact [

29].

Miso consumption seems to be a good lifestyle strategy for glycemic control improvement in diabetic individuals, while cross-sectional studies show that its inclusion in the usual diet may reduce insulin resistance in non-diabetics, as well as cases of gestational diabetes [

30]. Contrary to these data, our results demonstrated slightly higher glucose concentrations in the miso group, compared to the respective levels measured in the control group, since these results did not affect the glucose interactive effect during the 30-days of intervention. This contrast is reinforced by the existing research results, which indicate that some bioactive peptides produced during the fermentation process of chickpeas, may exert antidiabetic activity [

26]. Recent studies have demonstrated that various types of miso may be effective functional foods for the prevention of diabetes. This fermented product may act as a regulator of blood sugar levels through inhibition of digestive enzymes, mainly α-amylase, α-glucosidase and trypsin [

31]. Notably, the research group of Jiang et al. evaluated the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of rice miso at different fermentation times and found that prolonging the fermentation bioprocess enhanced this activity, mainly due to the presence of melanoidins and polyphenols [

32].

In addition, under the presence of isoflavones and bioactive peptides the insulin secretion and sensitivity may be enhanced, contributing to the regulation of blood glucose levels [

5]. Chickpea fermentation has been documented to reduce chymotrypsin and trypsin activity and the concentration of phytates, leading to slower carbohydrate absorption and promoting better glycemic control [

25]. Combining the existing research observations, it would be expected to observe an improved glycemic outcome following the consumption of the bio functional miso-type sauce, compared to the control sauce. Several lifestyle, dietary and biochemical factors and anti-nutrients (e.g. hemoglobin A1c levels, dietary intake, exercise habits, and phytates content) might highlight the possible complex role of the experimental miso-type sauce in glycemic control [

29].

This pilot clinical study shows the associations between habitual intake of a bio functional miso-type sauce, enhanced with bio-carotenoids and markers of oxidative stress and inflammation, but several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, it was designed as a long-term nutritional intervention to examine the effects of the habitual consumption of the bio functional miso-type sauce, enhanced with bio-carotenoid on lipidemia, glycemia and antioxidant status, metabolic indicators within a period of 30 days. However, the study protocol did not include intermediate measurements of the biomarkers tested for more accurate investigation of the metabolic outcomes. Secondly, the trial population consisted of a small number of healthy participants; therefore, it is unclear whether the results reflect the efficacy to individuals who suffer from chronic diseases associated with oxidative stress and chronic inflammation, such as diabetic and cardiovascular patients. In addition, despite extensive guidelines the lifestyle factors were not controlled in this trial protocol, so there is a possibility that part of the observed results might be related to healthy lifestyle habits during the study period. Also, data management did not include adjustment of other dietary variables. Therefore, the results of the clinical study may not include the metabolic responses associated with these confounding parameters, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Further analysis should examine the effect of the adjustment on the association between the bio functional miso-type sauce consumption and the biochemical biomarkers.

Concerning future perspectives, further investigation of the impact of habitual intake of the bio functional miso-type sauce enhanced with bio-carotenoids, in dose response manner, could be suggested to explore the exact dose in which the bioactive compounds are bioavailable and effective in altering metabolic parameters. Moreover, possible association between habitual bio functional miso-type sauce consumption and specific oxidative stress-inflammation could yield valuable insights. The measurement of insulin and hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) might provide better estimation regarding the glycemic control outcomes. Additionally, the evaluation of triglycerides to HDL cholesterol ratio may facilitate a more in-depth investigation of the effectiveness on insulin resistance [

29]. Finally, due to the crucial role of proinflammatory cytokines in the up-regulation of inflammatory reactions, the determination of inflammatory biomarkers including Interleukin (IL)-6, IL-18, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and the inflammatory high sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP), is needed to enhance the understanding of the modulatory effects on inflammation status.

.

.