Submitted:

01 October 2023

Posted:

04 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and methods

2.1. Experimental design and animal care

2.2. Determination of the quantitative GSH level and GSH/GSSG ratio

2.3. Determination of lipid peroxidation (MDA)

2.4. RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

2.5. Primers and gene expression analysis

2.6. Homogenate preparation and protein determination assay

2.7. Enzyme activity assays

2.8. Data collection from databases and the validation of obtained data

2.9. Statistical analysis

3. Results

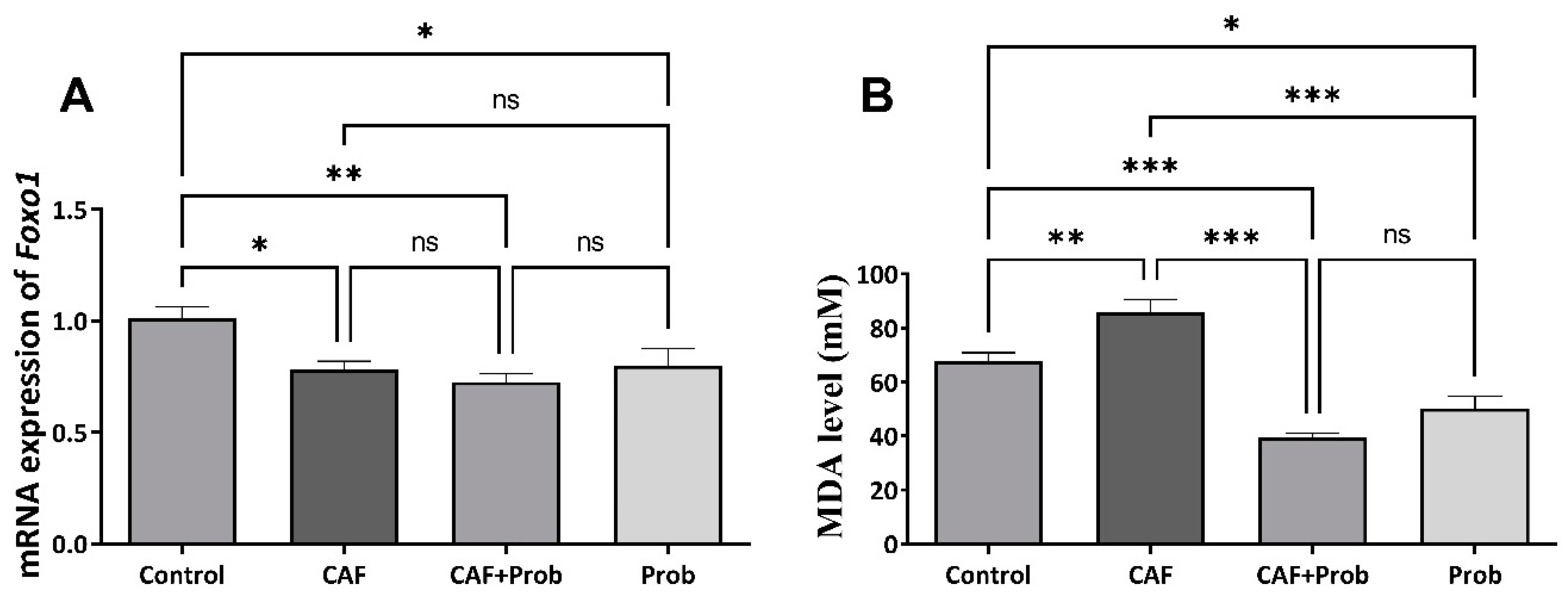

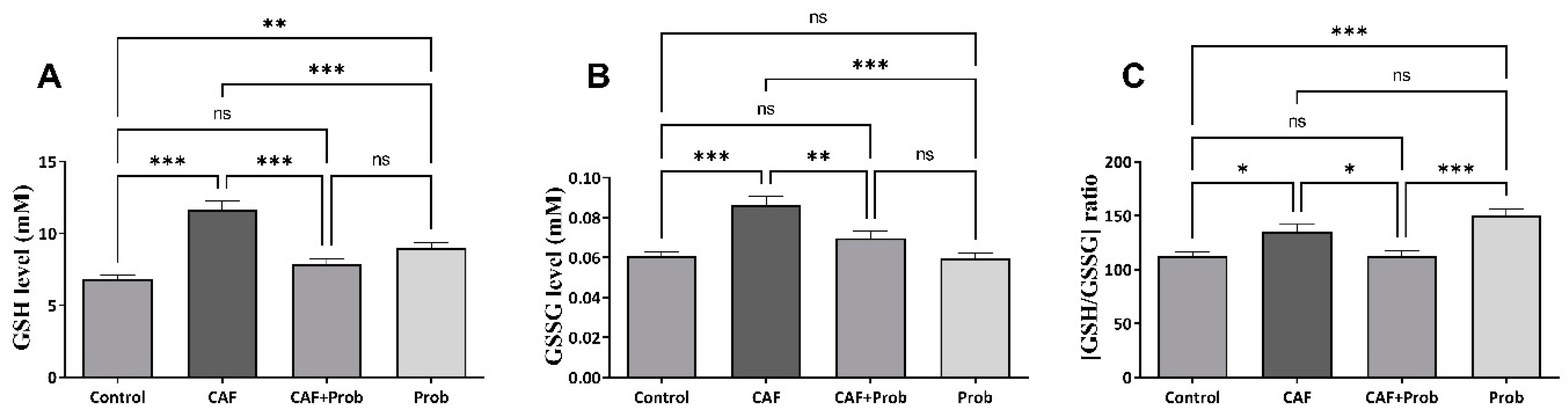

3.1. Effects of different diet combinations on quantitative hepatic metabolite levels

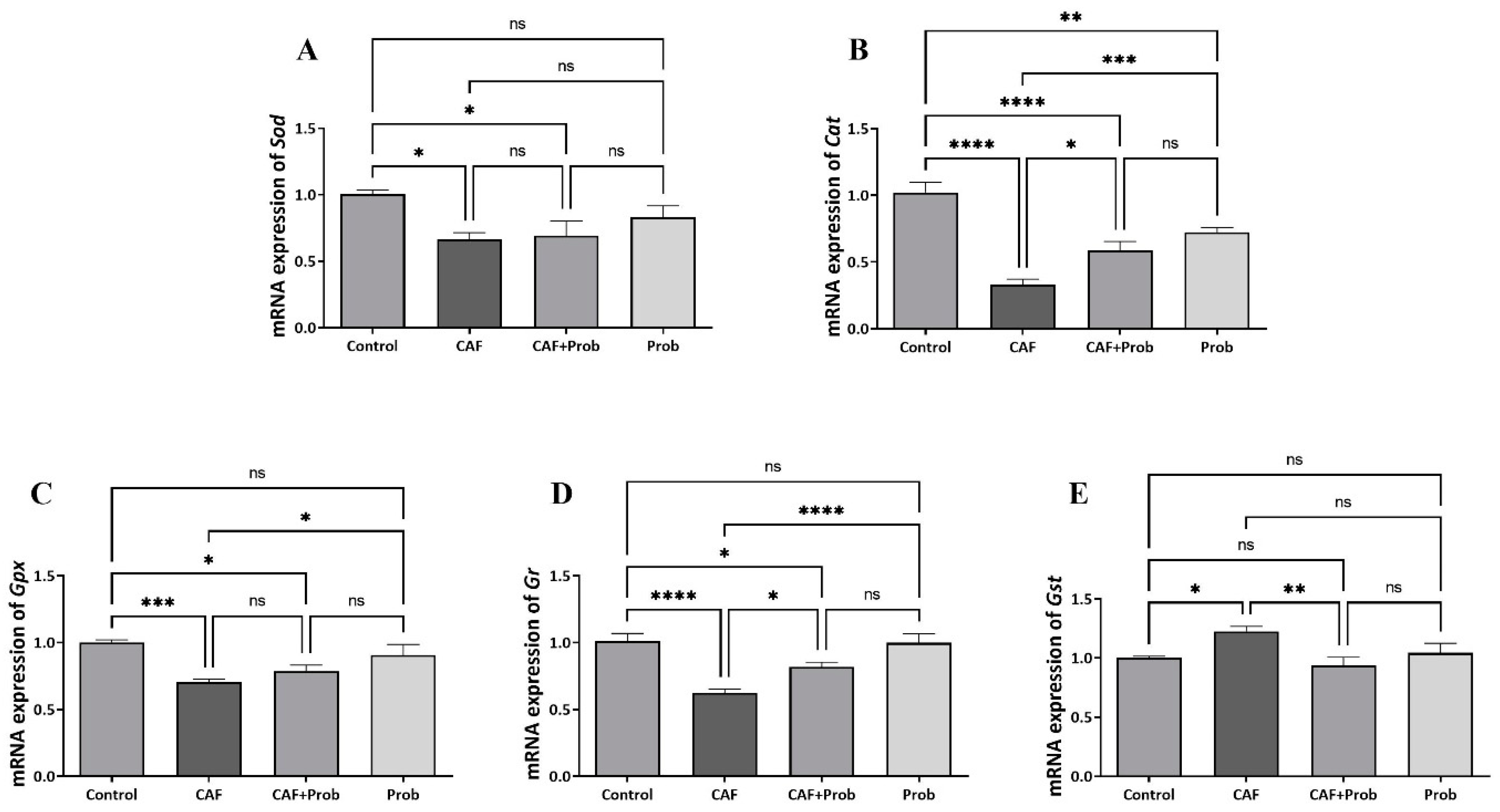

3.2. Effect of diet practices on hepatic antioxidant gene expressions

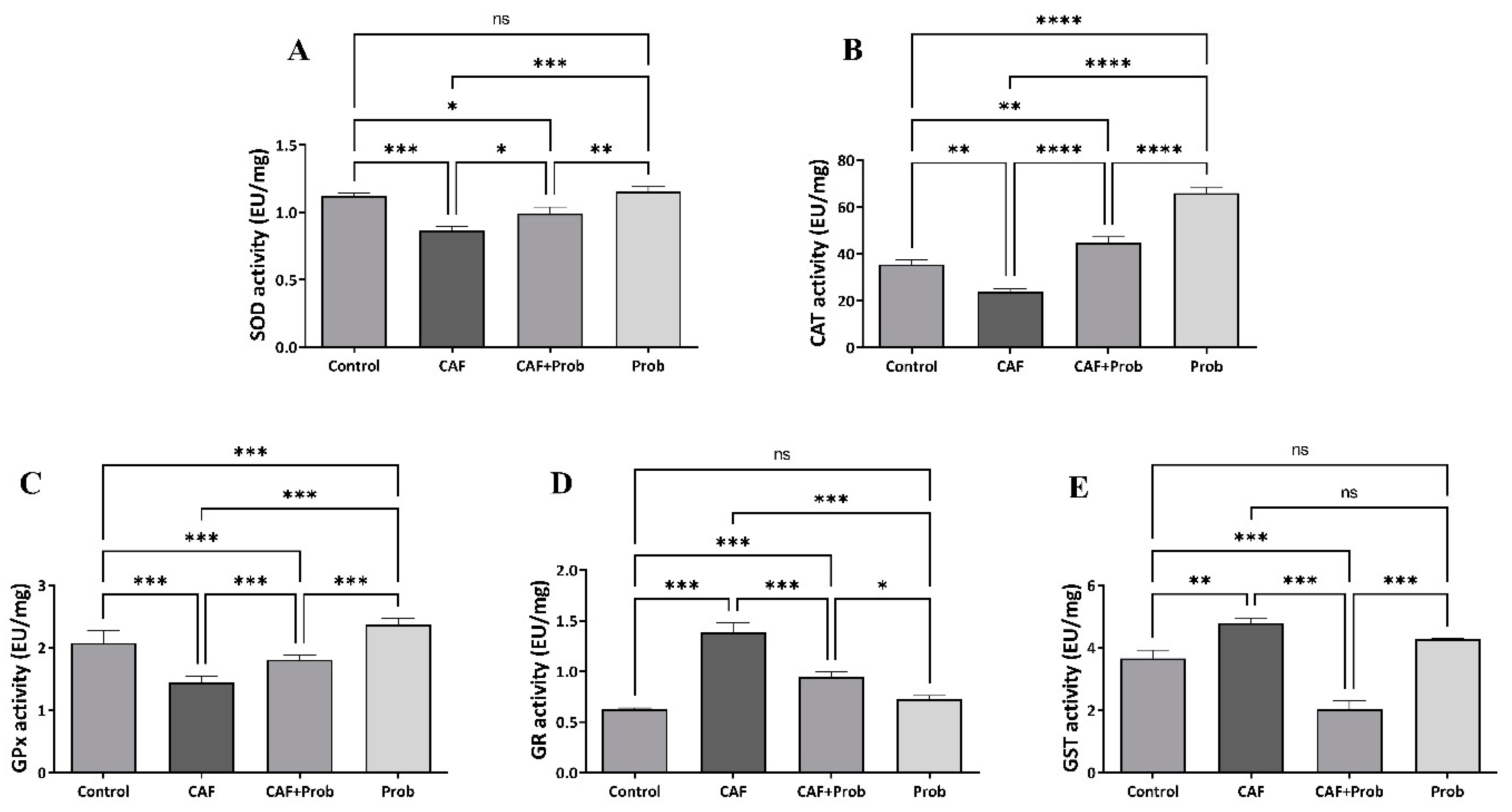

3.3. The effect of dietary practices on the enzyme activities of hepatic antioxidant system

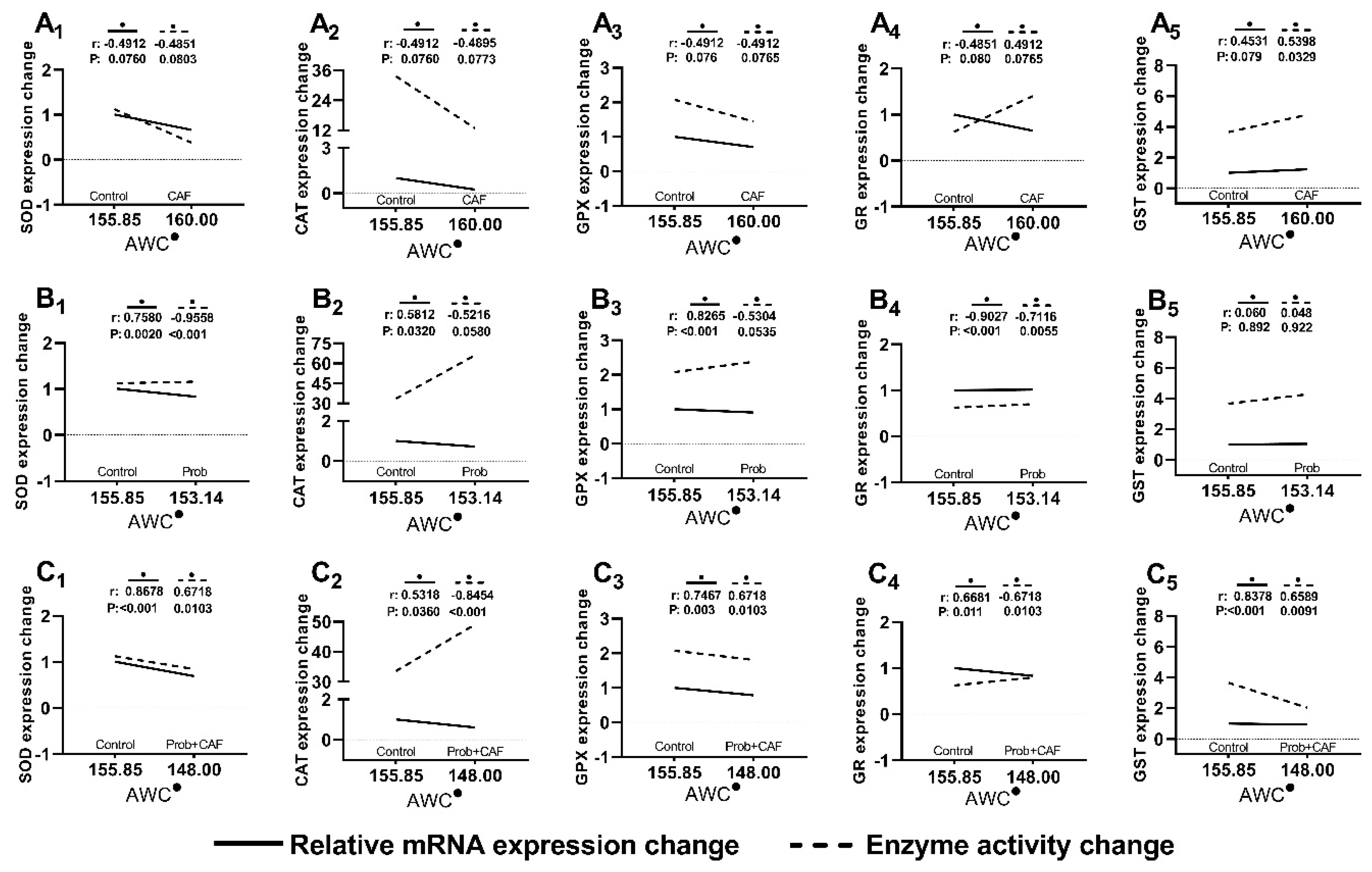

3.4. Correlation of hepatic antioxidant system based on AWC

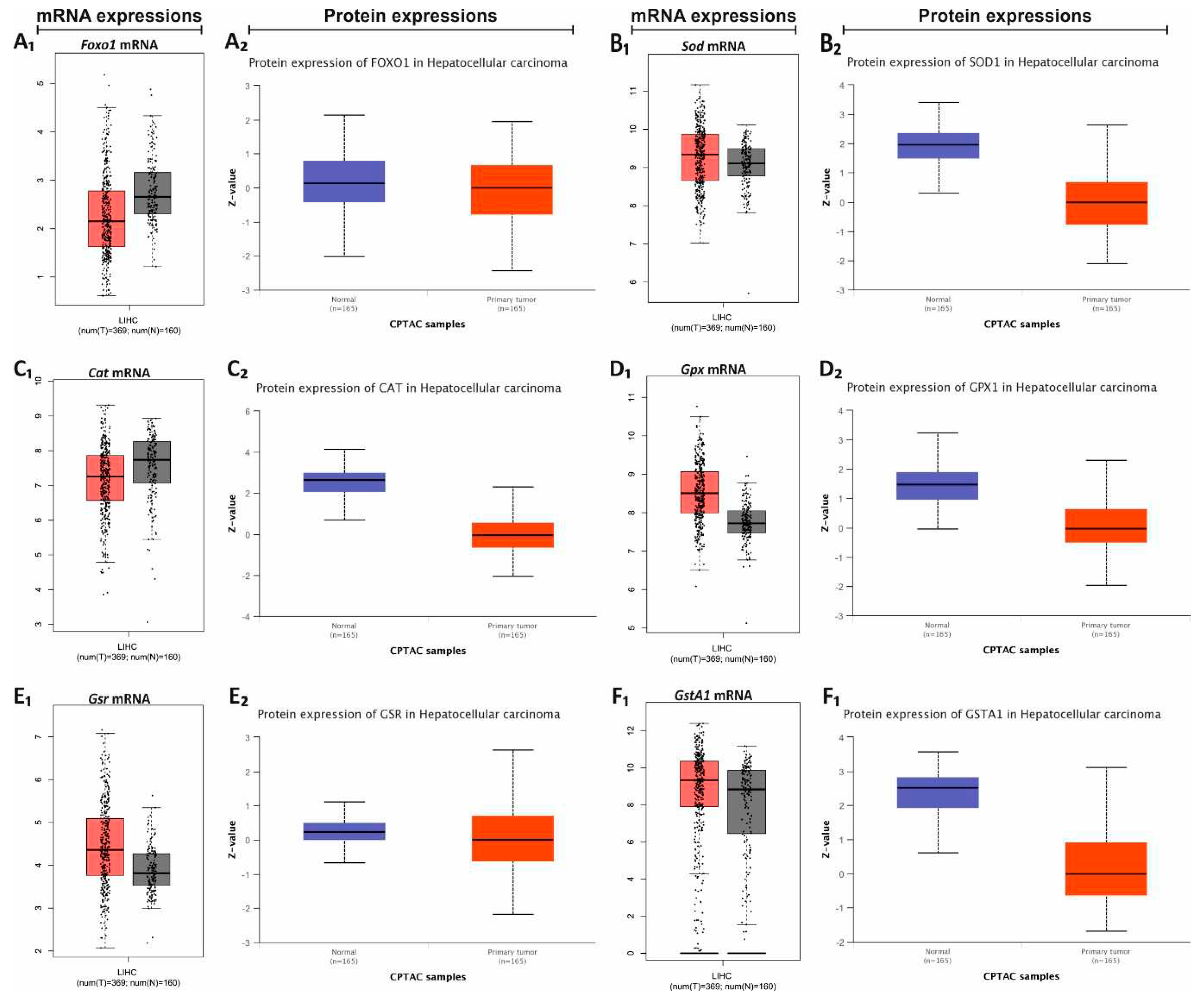

3.5. Identification of LIHC prevalence based on the obesity

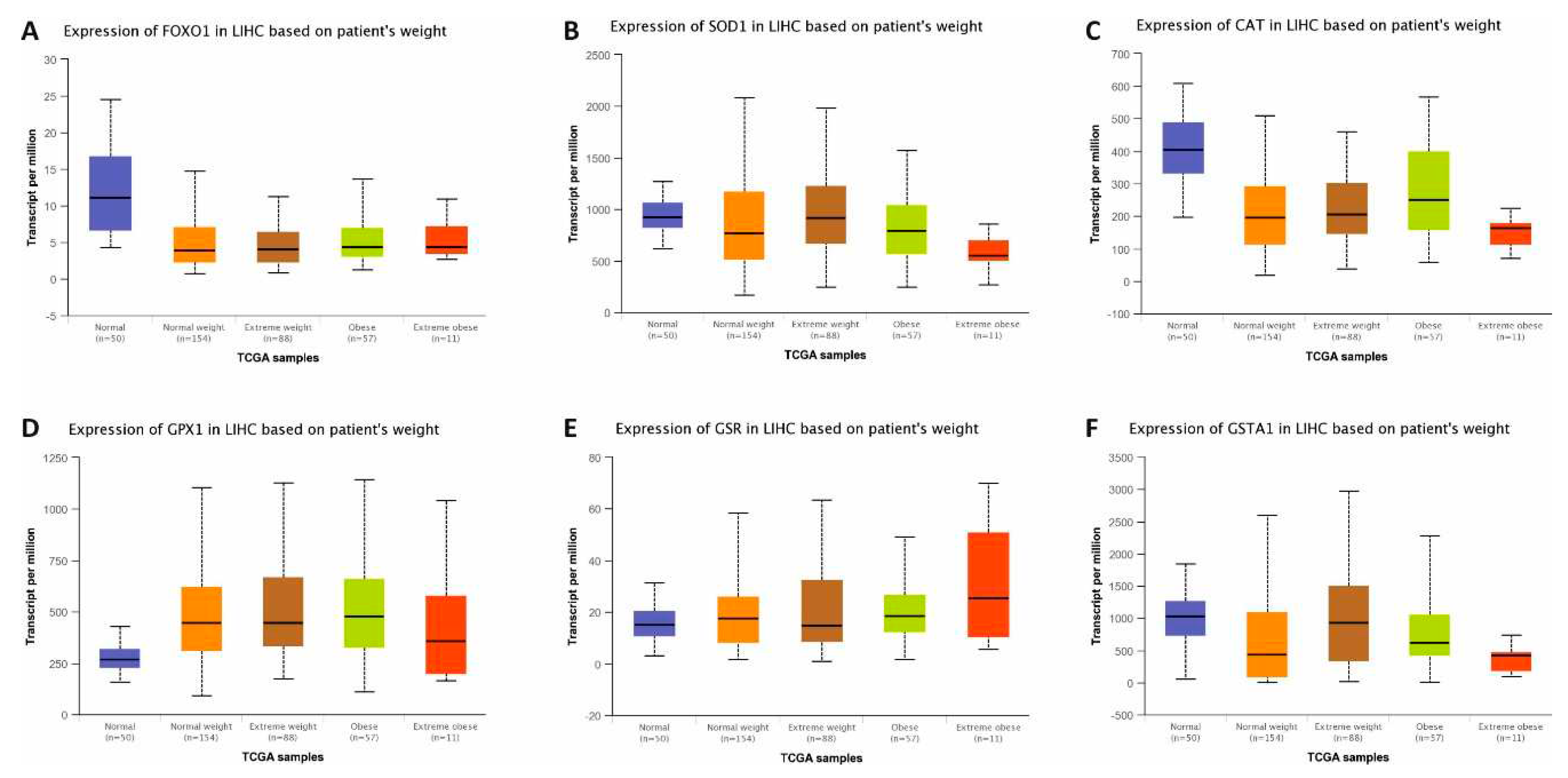

3.6. Identification of LIHC prevalence based on patient weight

4. Discussion

Highlights

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lalanza, J.F.; Snoeren, E.M.S. The cafeteria diet: A standardized protocol and its effects on behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2021, 122, 92–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Russa, D.; Giordano, F.; Marrone, A.; Parafati, M.; Janda, E.; Pellegrino, D. Oxidative Imbalance and Kidney Damage in Cafeteria Diet-Induced Rat Model of Metabolic Syndrome: Effect of Bergamot Polyphenolic Fraction. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukdere, Y.; Gulec, A.; Akyol, A. Cafeteria diet increased adiposity in comparison to high fat diet in young male rats. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subias-Gusils, A.; Boque, N.; Caimari, A.; Del Bas, J.M.; Marine-Casado, R.; Solanas, M.; Escorihuela, R.M. A restricted cafeteria diet ameliorates biometric and metabolic profile in a rat diet-induced obesity model. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2021, 72, 767–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, F.A.; Costa, W.S.; FJ, B.S.; Gregorio, B.M. Resveratrol attenuates metabolic, sperm, and testicular changes in adult Wistar rats fed a diet rich in lipids and simple carbohydrates. Asian journal of andrology 2019, 21, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.; Hasselwander, S.; Li, H.; Xia, N. Effects of different diets used in diet-induced obesity models on insulin resistance and vascular dysfunction in C57BL/6 mice. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 19556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolin, R.; Vargas, A.; Gasparotto, J.; Chaves, P.; Schnorr, C.E.; Martinello, K.B.; Silveira, A.; Rabelo, T.K.; Gelain, D.; Moreira, J. A new animal diet based on human Western diet is a robust diet-induced obesity model: comparison to high-fat and cafeteria diets in term of metabolic and gut microbiota disruption. International Journal of Obesity 2018, 42, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gual-Grau, A.; Guirro, M.; Mayneris-Perxachs, J.; Arola, L.; Boque, N. Impact of different hypercaloric diets on obesity features in rats: a metagenomics and metabolomics integrative approach. J Nutr Biochem 2019, 71, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crew, R.C.; Waddell, B.J.; Mark, P.J. Maternal obesity induced by a ‘cafeteria’diet in the rat does not increase inflammation in maternal, placental or fetal tissues in late gestation. Placenta 2016, 39, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Bonfim, T.H.F.; Tavares, R.L.; de Vasconcelos, M.H.A.; Gouveia, M.; Nunes, P.C.; Soares, N.L.; Alves, R.C.; de Carvalho, J.L.P.; Alves, A.F.; de Alencar Pereira, R. Potentially obesogenic diets alter metabolic and neurobehavioural parameters in Wistar rats: A comparison between two dietary models. Journal of Affective Disorders 2021, 279, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Cardoso, K.; Gines, I.; Pinent, M.; Ardevol, A.; Terra, X.; Blay, M. A cafeteria diet triggers intestinal inflammation and oxidative stress in obese rats. The British journal of nutrition 2017, 117, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beilharz, J.; Kaakoush, N.; Maniam, J.; Morris, M. Cafeteria diet and probiotic therapy: cross talk among memory, neuroplasticity, serotonin receptors and gut microbiota in the rat. Molecular psychiatry 2018, 23, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajoka, M.; Thirumdas, R.; Mehwish, H.; Umair, M.; Khurshid, M.; Hayat, H.; Phimolsiripol, Y.; Pallarés, N.; Martí-Quijal, F. Role of Food Antioxidants in Modulating Gut Microbial Com-Munities: Novel Understandings in Intestinal Oxidative Stress Damage and Their Impact on Host Health. food science and nutrition 2019, 59, 1927–1936. [Google Scholar]

- Alan, Y.; Savcı, A.; Koçpınar, E.F.; Ertaş, M. Postbiotic metabolites, antioxidant and anticancer activities of probiotic Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides strains in natural pickles. Archives of Microbiology 2022, 204, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceylani, T. Effect of SCD probiotics supplemented with tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) application on the aged rat gut microbiota composition. J Appl Microbiol 2023, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonmez Aydin, F.; Hukkamli, B.; Budak, H. Coaction of hepatic thioredoxin and glutathione systems in iron overload-induced oxidative stress. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2021, 35, e22704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkawa, H.; Ohishi, N.; Yagi, K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem 1979, 95, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. Methods in enzymology 1984, 105, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Oberley, L.W.; Li, Y. A simple method for clinical assay of superoxide dismutase. Clinical chemistry 1988, 34, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlberg, I.; Mannervik, B. Glutathione reductase. Methods in enzymology 1985, 113, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habig, W.H.; Pabst, M.J.; Jakoby, W.B. Glutathione S-transferases. The first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. The Journal of biological chemistry 1974, 249, 7130–7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Kang, B.; Li, C.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Z. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic acids research 2019, 47, W556–W560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, D.S.; Bashel, B.; Balasubramanya, S.A.H.; Creighton, C.J.; Ponce-Rodriguez, I.; Chakravarthi, B.; Varambally, S. UALCAN: A Portal for Facilitating Tumor Subgroup Gene Expression and Survival Analyses. Neoplasia 2017, 19, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocpinar, E.F.; Baltaci, N.G.; Akkemik, E.; Budak, H. Depletion of Tip60/Kat5 affects the hepatic antioxidant system in mice. J Cell Biochem 2023, 124, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dequanter, D.; Dok, R.; Nuyts, S. Basal oxidative stress ratio of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas correlates with nodal metastatic spread in patients under therapy. Onco Targets Ther 2017, 10, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkazemi, D.; Rahman, A.; Habra, B. Alterations in glutathione redox homeostasis among adolescents with obesity and anemia. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yen, F.S.; Zhu, X.G.; Timson, R.C.; Weber, R.; Xing, C.; Liu, Y.; Allwein, B.; Luo, H.; Yeh, H.W.; et al. SLC25A39 is necessary for mitochondrial glutathione import in mammalian cells. Nature 2021, 599, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, H. Identification of hub genes associated with obesity-induced hepatocellular carcinoma risk based on integrated bioinformatics analysis. Medical Oncology 2021, 38, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahma, M.K.; Gilglioni, E.H.; Zhou, L.; Trépo, E.; Chen, P.; Gurzov, E.N. Oxidative stress in obesity-associated hepatocellular carcinoma: Sources, signaling and therapeutic challenges. Oncogene 2021, 40, 5155–5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Song, Z.; Tan, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S. Identification and Validation of Hub Genes Associated With Hepatocellular Carcinoma Via Integrated Bioinformatics Analysis. Frontiers in oncology 2021, 11, 614531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galasso, M.; Gambino, S.; Romanelli, M.G.; Donadelli, M.; Scupoli, M.T. Browsing the oldest antioxidant enzyme: catalase and its multiple regulation in cancer. Free radical biology & medicine 2021, 172, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, Q.; Cao, B.; Huang, B.; Wang, T.; Guo, R.; Liu, N. SP1-induced lncRNA ZFPM2 antisense RNA 1 (ZFPM2-AS1) aggravates glioma progression via the miR-515-5p/Superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) axis. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 2299–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Benhawy, S.A.; Morsi, M.I.; El-Tahan, R.A.; Matar, N.A.; Ehmaida, H.M. Radioprotective Effect of Thymoquinone in X-irradiated Rats. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP 2021, 22, 3005–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar Ijaz, M.; Rauf, A.; Mustafa, S.; Ahmed, H.; Ashraf, A.; Al-Ghanim, K.; Swamy Mruthinti, S.; Mahboob, S. Pachypodol attenuates Perfluorooctane sulphonate-induced testicular damage by reducing oxidative stress. Saudi J Biol Sci 2022, 29, 1380–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Onset | Week1 | Week2 | Week3 | Week4 | Week5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | Control | 1792 | 1803 | 2483 | 3247 | 3686 | 3476 |

| CAF | 1792 | 2354 | 3740 | 5848 | 6471 | 6312 | |

| Prob+CAF | 1792 | 3264 | 3669 | 5863 | 5110 | 6140 | |

| Prob | 1792 | 2093 | 3056 | 3629 | 3575 | 3285 | |

| Rodent nutrition (g) | Control | 67 | 67 | 93 | 121 | 138 | 130 |

| CAF | 67 | 61 | 89 | 136 | 134 | 123 | |

| Prob+CAF | 67 | 38 | 55 | 57 | 50 | 65 | |

| Prob | 67 | 41 | 53 | 58 | 39 | 47 | |

| AWC | Control | 79.9±5.24 | 105.8±5.61 | 134.8±7.91 | 165.6±7.87 | 196.7±7.26 | 235.7±6.98 |

| CAF | 79.3±5.24 | 105.1±5.43 | 128.6±5.76 | 173.7±5.96 | 207.8±7.84 | 239.3±9.36 | |

| Prob+CAF | 79.3±5.69 | 106.1±5.65 | 133.1±6.69 | 172.7±6.05 | 203.4±7.06 | 227.3±6.24 | |

| Prob | 79.7±5.39 | 108.1±5.26 | 130.6±5.87 | 165.6±7.51 | 203.7±10.09 | 232.8±8.78 |

| Gene Symbols | Accession Number | Elongation position | Sequence (5’-3’) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sod | NM_017050.1 | Forward | 5′-GCTTCTGTCGTCTCCTTGCT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CTCGAAGTGAATGACGCCCT-3′ | ||

| Cat | NM_012520.2 | Forward | 5′-GCGAATGGAGAGGCAGTGTA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GTGCAAGTCTTCCTGCCTCT-3′ | ||

| Gr | NM_053906.2 | Forward | 5′-AGTTCACTGCTCCACACATCC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TCCAGCTGAAAGAACCCATC-3′ | ||

| Gpx | NM_183403.2 | Forward | 5′-TGGCTTACATCGCCAAGTC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CCGGGTAGTTGTTCCTCAGA-3′ | ||

| Gst | NM_017013.4 | Forward | 5′-AGACGGGAATTTGATGTTTGAC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TGTCAATCAGGGCTCTCTCC-3′ | ||

| Foxo1 | NM_001285835.1 | Forward | 5′-ACCGTATCTGTGTGTGTGTGTG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-ACAGCCAAGTCCATCAAGAC-3′ | ||

| Gapdh | NM_007393.5 | Forward | 5′-TGGACCTCATGGCCTACATG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AGGGAGATGCTCAGTGTTGG-3′ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).