Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

| Zambia (n=21,280) | Tanzania (n=32,635) | |

|---|---|---|

| Variable | N (%) | N (%) |

| Age | 29 (IQR: 21-39) | 31 (IQR: 22-45) |

| Female Gender | 12,109 (56.9%) | 18,172 (55.7%) |

| Male | 9,171 (43.1%) | 14,463 (44.3 %) |

| Active syphilis | ||

| Yes | 591 (2.8%) | 328 (1%) |

| No | 18,566 (87.2%) | 32,306 (99%) |

| Ever syphilis | ||

| Yes | 1,361 (6.4%) | 2,026 (6.2%) |

| No | 17,796 (83.6%) | 30,608 (93.8%) |

| HIV Acquired | 2,467 (11.6%) | 1,895 (5.8%) |

| Viral Load suppressed | 1,465 (6.9%) | 994 (3%) |

| Zambia | Tanzania | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HIV positive (n=2,467, 12.9%) | HIV negative (n=16,648, 87.1%) | P-Value | HIV positive (n=1,895, 5.8%) | HIV negative (n=30,740, 94.2%) | P-Value |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

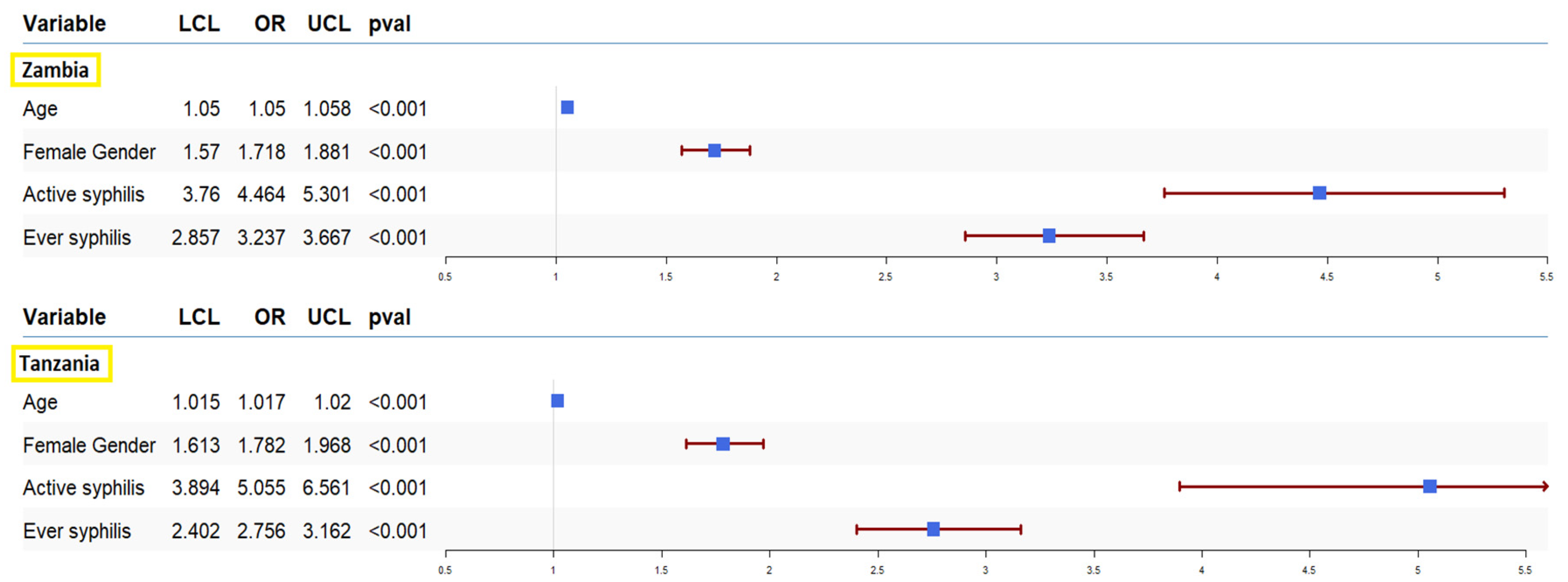

| Age | 38 (IQR: 30-45) | 27 (IQR: 20-38) | < 0.001 | 39 (IQR: 30-47) | 30 (IQR: 21-44) | < 0.001 |

| Female Gender | 1,688 (68.4%) | 9,285 (55.8%) | < 0.001 | 1,297 (68.4%) | 16,875 (54.9%) | < 0.001 |

| Active syphilis | ||||||

| Yes | 225 (9.1%) | 366 (2.2%) | < 0.001 | 76 (4%) | 252 (0.8%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 2,242(90.9%) | 16281(97.8%) | 1,819(96%) | 30,487(99.2%) | ||

| Ever syphilis | ||||||

| Yes | 406 (16.4%) | 955 (5.7%) | < 0.001 | 271 (14.3%) | 1,755 (5.7%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 2,061(83.6%) | 15,692(94.3%) | 1,624(85.7%) | 28,984(94.3%) | ||

| Zambia | Tanzania | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HIV suppressed (n=487, 61.5%) | HIV not suppressed (n=305, 38.5%) | P-Value | HIV suppressed (n=299, 55.1%) | HIV not suppressed (n=243, 44.8%) | P-Value |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

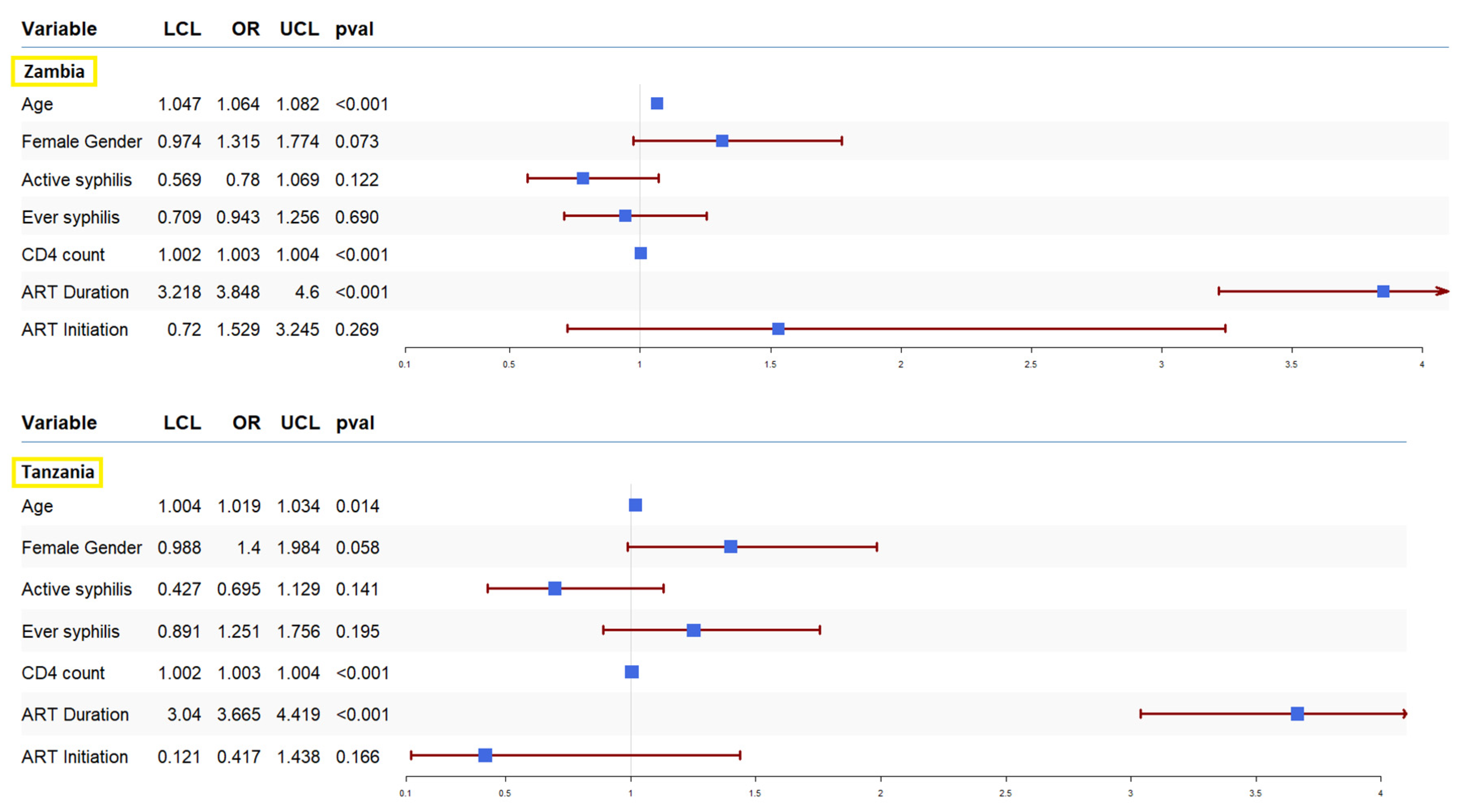

| Age | 40 (IQR: 32-46) | 32 (IQR: 28-42) | < 0.001 | 43 (IQR: 36-52) | 40 (IQR: 32-49) | < 0.001 |

| CD4 count | 475 (IQR: 344-635) | 333 (IQR:207-492.5) | < 0.001 | 483.5 (IQR: 346.8-655) | 328 (IQR: 191-485) | < 0.001 |

| Female Gender | 332 (68.2%) | 189 (62%) | 0.07 | 196 (65.5%) | 140 (57.6%) | 0.06 |

| Active syphilis | ||||||

| Yes | 127 (26.1%) | 95 (31.1%) | 0.1235 | 36 (12.0%) | 40 (16.5%) | 0.171 |

| No | 360(73.9%) | 210(68.9%) | 263(88%) | 203(83.5%) | ||

| Ever syphilis | ||||||

| Yes | 242 (49.7%) | 156 (51.1%) | 0.7153 | 157 (52.5%) | 114 (46.9%) | 0.2266 |

| No | 245(50.3%) | 149(48.9%) | 142(47.5%) | 129(53.1%) | ||

| ART status | 457 (93.8%) | 33 (10.8%) | < 0.001 | 265 (88.6%) | 33 (13.6%) | < 0.001 |

| ART initiation | 343 (70.4%) | 34 (11.1%) | 0.29 | 169 (56.5%) | 27 (11.1%) | 0.219 |

| ART duration | ||||||

| Not on ART | 69 (14.2%) | 264 (86.5%) | < 0.001 | 33 (11.0%) | 199 (81.9%) | < 0.001 |

| On ART <12 months | 66 (13.5%) | 10 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| On ART 12-23 months | 56 (11.5%) | 4 (1.3%) | 27 (9%) | 5 (2%) | ||

| On ART 24 months or more | 279 (57.3%) | 26 (8.5%) | 186 (62.2%) | 25 (10.3%) | ||

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tudor ME, Al Aboud AM, Leslie SW, et al. Syphilis. [Updated 2024 Aug 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534780/ (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention- Syphilis -fact sheet; Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/syphilis/about/index.html (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO) Syphilis- overview, Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/syphilis#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Mussa A, Jarolimova J, Ryan R, Wynn A, Ashour D, Bassett IV, Philpotts LL, Freyne B, Morroni C, Dugdale CM. Syphilis Prevalence Among People Living With and Without HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sex Transm Dis. 2024, 51, e1–e7. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Godfrey, J.A. Walker, Damian G. Walker,Congenital syphilis: A continuing but neglected problem,Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine,Volume 12, Issue 3,2007,Pages 198 206,ISSN 1744-165X. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1744165X07000200. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Data on Syphilis, Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/data-on-syphilis (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO) Sexually transmitted infections (STIs): Strategic information. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-programmes/stis/strategic-information (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- World Health Organization. (2024). Implementing the global health sector strategies on HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections, 2022–2030: report on progress and gaps 2024, 2nd ed. World Health Organization. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/378246 (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- World Health Organization, global health sector strategy on sexually transmitted infections 2016–2021 towards ending STIs. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/246296/WHO-RHR-16.09-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Fan L, Yu A, Zhang D, Wang Z, Ma P. Consequences of HIV/Syphilis Co-Infection on HIV Viral Load and Immune Response to Antiretroviral Therapy. Infect Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 2851–2862. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu Y, Zhu W, Sun C, Yue X, Zheng M, Fu G and Gong X. Prevalence of syphilis among people living with HIV and its implication for enhanced coinfection monitoring and management in China: A meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1002342. [CrossRef]

- Wu MY, Gong HZ, Hu KR, Zheng HY, Wan X, Li J. Effect of syphilis infection on HIV acquisition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2021, 97, 525–533. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gilbert L, Dear N, Esber A, Iroezindu M, Bahemana E, Kibuuka H, Owuoth J, Maswai J, Crowell TA, Polyak CS, Ake JA; AFRICOS Study Group. Prevalence and risk factors associated with HIV and syphilis co-infection in the African Cohort Study: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2021, 21, 1123. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Solomon H, Moraes AN, Williams DB, Fotso AS, Duong YT, Ndongmo CB, et al. Prevalence and correlates of active syphilis and HIV co-Infection among sexually active persons aged 15–59 years in Zambia: Results from the Zambia Population-based HIV Impact Assessment (ZAMPHIA) 2016. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236501. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Lu L, Song X, Liu X, Yang Y, Chen L, Tang J, Han Y, Lv W, Cao W, Li T. Clinical and immunological characteristics of HIV/syphilis co-infected patients following long-term antiretroviral treatment. Front Public Health. 2024, 11, 1327896. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ren M, Dashwood T, Walmsley S. The Intersection of HIV and Syphilis: Update on the Key Considerations in Testing and Management. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2021, 18, 280–288. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang CL, Gao S, Li XZ, Martcheva M. Modeling Syphilis and HIV Coinfection: A Case Study in the USA. Bull Math Biol. 2023, 85, 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Luetkemeyer AF, Donnell D, Dombrowski JC, Cohen S, Grabow C, Brown CE, Malinski C, Perkins R, Nasser M, Lopez C, Vittinghoff E, Buchbinder SP, Scott H, Charlebois ED, Havlir DV, Soge OO, Celum C; DoxyPEP Study Team. Postexposure Doxycycline to Prevent Bacterial Sexually Transmitted Infections. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388, 1296–1306. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Molina JM, Charreau I, Chidiac C, et al. Post-exposure prophylaxis with doxycycline to prevent sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men: an open-label randomised substudy of the ANRS IPERGAY trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2018, 18, 308–317.

- La Ruche G, Goubard A, Bercot B, Cambau E, Semaille C, Sednaoui P. Gonococcal infections and emergence of gonococcal decreased susceptibility to cephalosporins in France, 2001 to 2012. Euro Surveill 2014, 19, 20885–20885.

- Bolan RK, Beymer MR, Weiss RE, Flynn RP, Leibowitz AA, Klausner JD. Doxycycline prophylaxis to reduce incident syphilis among HIV-infected men who have sex with men who continue to engage in high-risk sex: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Sex Transm Dis 2015, 42, 98–103.

- He L, Pan X, Yang J, Zheng J, Luo M, Cheng W, Chai C. Current syphilis infection in virally suppressed people living with HIV: a cross-sectional study in eastern China. Front Public Health. 2024, 12, 1366795. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Billock RM, Samoff E, Lund JL, Pence BW, Powers KA. HIV Viral Suppression and Pre-exposure Prophylaxis in HIV and Syphilis Contact Tracing Networks: An Analysis of Disease Surveillance and Prescription Claims Data. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021, 88, 157–164. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nicola, M. Zetola, Jeffrey D. Klausner, Syphilis and HIV Infection: An Update, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 44, Issue 9, 1 May 2007, Pages 1222–1228. 1 May. [CrossRef]

- Buchacz K, Patel P, Taylor M, Kerndt PR, Byers RH, Holmberg SD, Klausner JD. Syphilis increases HIV viral load and decreases CD4 cell counts in HIV-infected patients with new syphilis infections. AIDS. 2004, 18, 2075–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ghanem KG, Moore RD, Rompalo AM, Erbelding EJ, Zenilman JM, Gebo KA. Antiretroviral therapy is associated with reduced serologic failure rates for syphilis among HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2008, 47, 258–65. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ghanem, Khalil G; Moore, Richard D; Rompalo, Anne M; Erbelding, Emily J; Zenilman, Jonathan M; Gebo, Kelly A. Neurosyphilis in a clinical cohort of HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS 22, p 1145-1151, June 19, 2008. |. [CrossRef]

- Population-based HIV Impact Assessment (PHIA) project. Available online: https://phia.icap.columbia.edu/ (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Tanzania Commission for AIDS (TACAIDS), Zanzibar AIDS Commission (ZAC). Tanzania HIV Impact Survey (THIS) 2016-2017: Final Report. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. December 2018, Available online:. Available online: https://phia.icap.columbia.edu/tanzania-final-report/ (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Ministry of Health, Zambia. Zambia Population-based HIV Impact Assessment (ZAMPHIA) 2016: Final Report. Lusaka, Ministry of Health. February 2019, Available online:. Available online: https://phia.icap.columbia.edu/zambia-final-report/ (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- PHIA Data Use Manual, Available online: https://phia-data.icap.columbia.edu/storage/Country/28-09-2021-22-01-17-615390ad6a147.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Farahani M, Killian R, Reid GA, Musuka G, Mugurungi O, Kirungi W, Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha H, El-Sadr WM, Justman J. Prevalence of syphilis among adults and adolescents in five sub-Saharan African countries: findings from Population-based HIV Impact Assessment surveys. Lancet Glob Health. 2024, 12, e1413–e1423. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachathep K, Radin E, Hladik W, Hakim A, Saito S, Burnett J, Brown K, Phillip N, Jonnalagadda S, Low A, Williams D, Patel H, Herman-Roloff A, Musuka G, Barr B, Wadondo-Kabonda N, Chipungu G, Duong Y, Delgado S, Kamocha S, Kinchen S, Kalton G, Schwartz L, Bello G, Mugurungi O, Mulenga L, Parekh B, Porter L, Hoos D, Voetsch AC, Justman J. Population-Based HIV Impact Assessments Survey Methods, Response, and Quality in Zimbabwe, Malawi, and Zambia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021, 87(Suppl 1), S6-S16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Getaneh Y, Getnet F, Amogne MD, Liao L, Yi F, Shao Y. Burden of hepatitis B virus and syphilis co-infections and its impact on HIV treatment outcome in Ethiopia: nationwide community-based study. Ann Med. 2023, 55, 2239828. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shimelis T, Tassachew Y, Tadewos A, Hordofa MW, Amsalu A, Tadesse BT, Tadesse E. Coinfections with hepatitis B and C virus and syphilis among HIV-infected clients in Southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2017, 9, 203–210. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yuindartanto, A. , Hidayati, A. N., Indramaya, D. M., Listiawan, M. Y., Ervianti, E., & Damayanti, D. Risk Factors of Syphilis and HIV/AIDS Coinfection. Berkala Ilmu Kesehatan Kulit Dan Kelamin 2022, 34, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud S, Mohsin M, Muyeed A, Islam MM, Hossain S, Islam A. Prevalence of HIV and syphilis and their co-infection among men having sex with men in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2023, 9, e13947. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Parmley LE, Chingombe I, Wu Y, Mapingure M, Mugurungi O, Samba C, Rogers JH, Hakim AJ, Gozhora P, Miller SS, Musuka G, Harris TG. High Burden of Active Syphilis and Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Syphilis Coinfection Among Men Who Have Sex With Men, Transwomen, and Genderqueer Individuals in Zimbabwe. Sex Transm Dis. 2022, 49, 111–116. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Musema, G. M. A. , Mapatano, A. M., Tshala, D. K. and Kayembe, P. K. HIV-1-syphilis co-infection associated with high viral load in female sex workers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. International Journal of Translational Medical Research and Public Health 2020, 4, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anteneh, D. E. , Taye, E. B., Seyoum, A. T., Abuhay, A. E., & Cherkose, E. A. Seroprevalence of HIV, HBV, and syphilis co-infections and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Amhara regional state, northern Ethiopia: A hospital-based cross-sectional study. Plos one 2024, 19, e0308634. [Google Scholar]

- Katamba C, Chungu T, Lusale C. HIV, syphilis and hepatitis B coinfections in Mkushi, Zambia: a cross-sectional study. F1000Res. 2019, 8, 562. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Haule A, Msemwa B, Mgaya E, Masikini P, Kalluvya S. Prevalence of syphilis, neurosyphilis and associated factors in a cross-sectional analysis of HIV infected patients attending Bugando Medical Centre, Mwanza, Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2020, 20, 1862. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mboowa G, Inda DA. Seroprevalence of syphilis among human immunodeficiency virus positive individuals attending immune suppressed syndrome clinic at international hospital Kampala, Uganda. Int STD Res Rev. 2015, 3, 84–90.

- Ruangtragool L, Silver R, Machiha A, Gwanzura L, Hakim A, Lupoli K, Musuka G, Patel H, Mugurungi O, Tippett Barr BA, Rogers JH. Factors associated with active syphilis among men and women aged 15 years and older in the Zimbabwe Population-based HIV Impact Assessment (2015-2016). PLoS One 2022, 17, e0261057. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Palacios R, Jiménez-Oñate F, Aguilar M, Galindo MJ, Rivas P, Ocampo A, Berenguer J, Arranz JA, Ríos MJ, Knobel H, Moreno F, Ena J, Santos J. Impact of syphilis infection on HIV viral load and CD4 cell counts in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007, 44, 356–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchacz K, Patel P, Taylor M, Kerndt PR, Byers RH, Holmberg SD, Klausner JD. Syphilis increases HIV viral load and decreases CD4 cell counts in HIV-infected patients with new syphilis infections. AIDS. 2004, 18, 2075–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kofoed K, Gerstoft J, Mathiesen LR, et al. Syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 coinfection: influence on CD4 T-cell count, HIV viral load, and treatment response. Sex Transm Dis. 2006, 33, 143–148.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).