1. Introduction

Miscanthus is a perennial allopolyploid C4 plant possesses for its rapid growth and high biomass, yielding up to 60 tons per hectare annually [

1].

Miscanthus has an elegant appearance and that makes it suitable as an ornamental plant, it has primarily been cultivated as a fuel crop. From both economic and environmental perspectives

Miscanthus serves as an effective plant for sustainable energy provision [

2]. Despite its robust tolerance to saline-alkali stress,

Miscanthus also demonstrates considerable tolerance to high concentrations of various heavy metals, thereby holding significant potential for production applications in saline-alkali soils [

3].

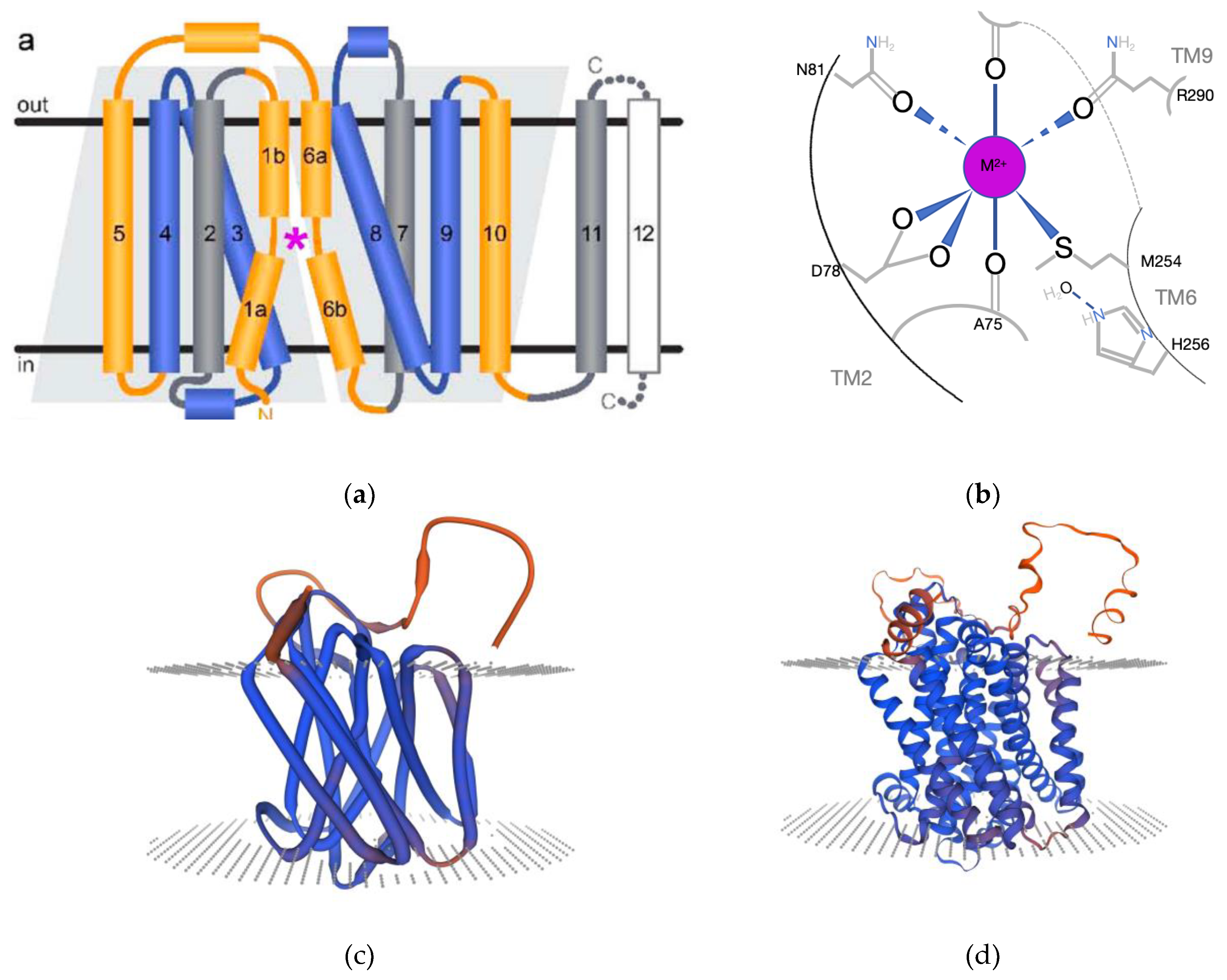

Natural resistance-associated macrophage proteins (NRAMP) are divalent metal cation transporters. The NRAMP family of proteins typically features a conserved hydrophobic domain and several transmembrane regions, usually numbering between 10 and 12 [

4]. These proteins possess a characteristic LeuT-like domain and exhibit a symport transport mechanism, whereby protons and metal cations are co-transported in the same direction after following their binding to specific residues [

5]. For instance, the divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1), which is essential for iron transport in the human body, is a member of the NRAMP family [

6]. Furthermore, NRAMPs have been extensively studied in Arabidopsis and rice, where they have been widely reported to enhance plant tolerance to heavy metal stress by reducing the uptake and accumulation of lead and cadmium ions [

7,

8,

9]. With the exception of OsNRAMP3, which is localized in the vacuole, the remaining of the rice NRAMP family proteins are reported to facilitate cadmium ion transport functions, and they can also transport trivalent aluminum ions [

10].

As a transporter protein, NRAMP is a crucial component of the signaling pathway. Studies on Arabidopsis seeds have found that at the transcriptional level, Arabidopsis

AtNRAMP1 is regulated by the transcription factor INO, which lays a protective role for seed cells aganist excessive iron toxicity [

11]. Additionally, NRAMP undergoes post-transcriptional modifications, such as the phosphorylation of AtNRAMP1 by AtCPK21 and AtCPK23, which regulates the entry of manganese ions into the vacuole, thereby protecting the plant from manganese toxicity [

12].

Given the significance of NRAMPs in metal ion homeostasis and the lack of comprehensive analysis in Miscanthus, this study aims to address the existing knowledge gap regarding the role of NRAMPs in Miscanthus sinensis. Our analysis encompasses genome-wide identification, phylogenetic classification, and an investigation into their potential roles in metal ion balance and stress response.

2. Results

2.1. Identifcation of NRAMP Family Genes in Miscanthus

The genomic data obtained from JGI was Msinensis_497_v7.1. With the method of BlastP and HMMER 2.0. A total of 26 MsNRAMP genes were identifed in Miscanthus, based on 7 OsNRAMPs and 6 AtNRAMPs extracted from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). After screening, 17 genes were found to possess the NRAMP conserved domain PF01566, and they were named MsNRAMP1 to MsNRAMP17.

The physicochemical properties of proteins were summarized in

Table 1. These MsNramp proteins range from 237 mino acids to 1301 amino acids in length. The subcellular localization prediction results for all these genes indicate that they are located on the plasma membrane. However,

MsNRAMP8 and

MsNRAMP9 proteins have only 4 and 6 transmembrane domains, respectively, indicating that

MsNRAMP8 and

MsNRAMP9 may not possess the full range of functions characteristic of other

NRAMP family proteins (Figure supplementary 1).

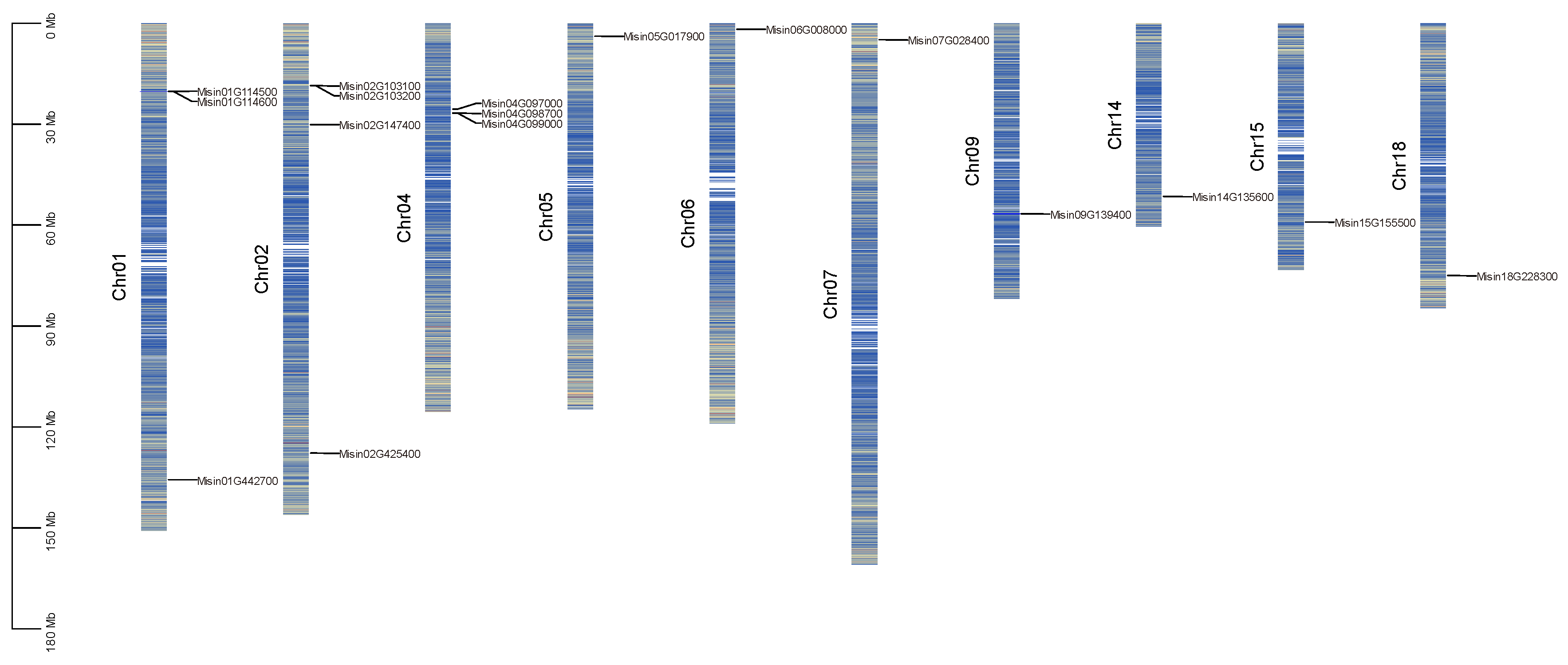

MsNRAMPs are distributed relatively evenly across the genome. Chromosome 2 contains four MsNRAMPs, while Chromosomes 1 and 3 each house three

MsNRAMPs. Additionally, Chromosomes 5, 6, 7, 9, 14, 15, and 18 each possess a single

MsNRAMP (

Figure 1).

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis and Motif Analysis of MsNRAMP

Miscanthus is closely related to sorghum and sugarcane [

14]. However, given the extensive research on the functions of NRAMP in rice species, we have chosen to construct an evolutionary tree that includes the model organism Oryza sativa and

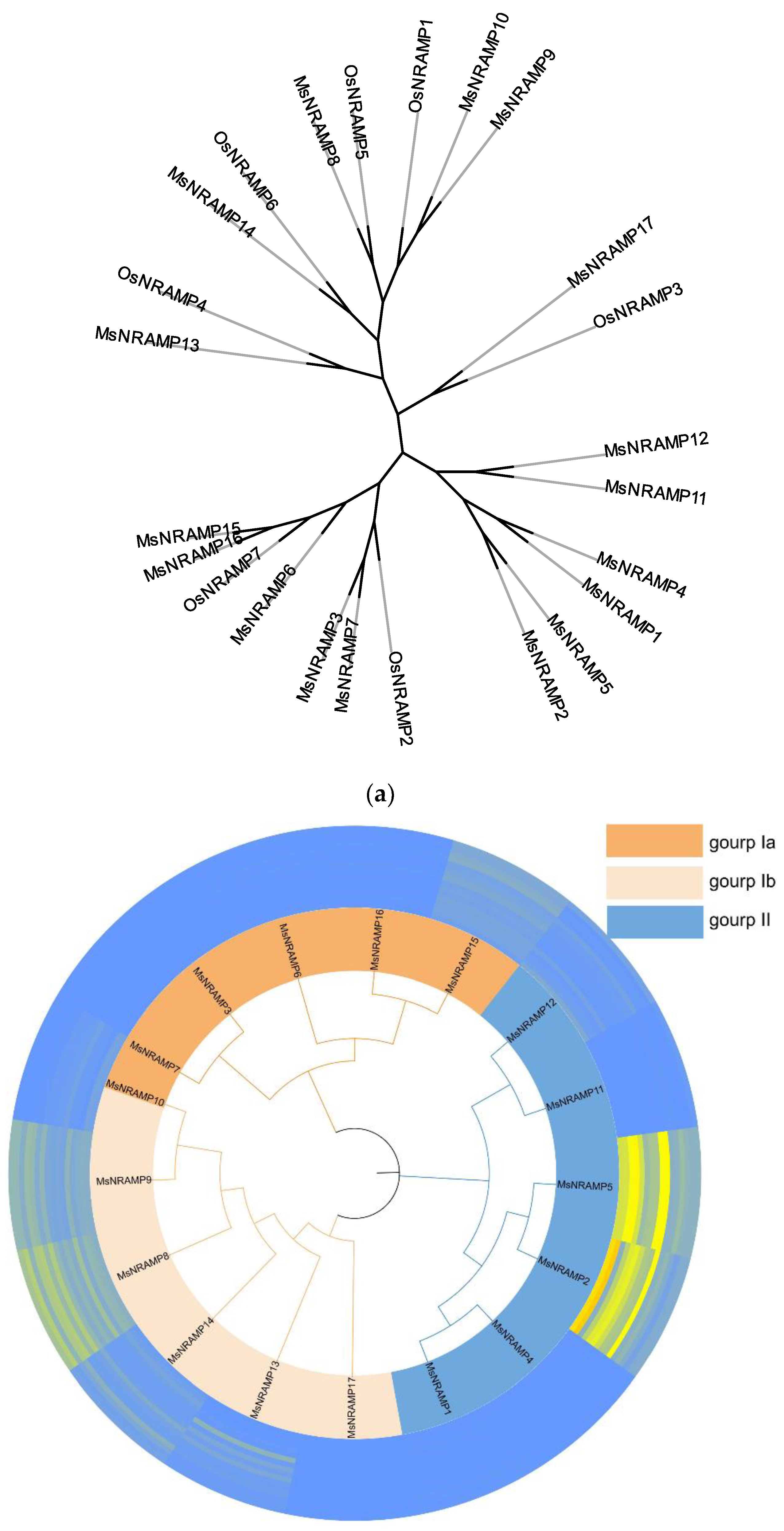

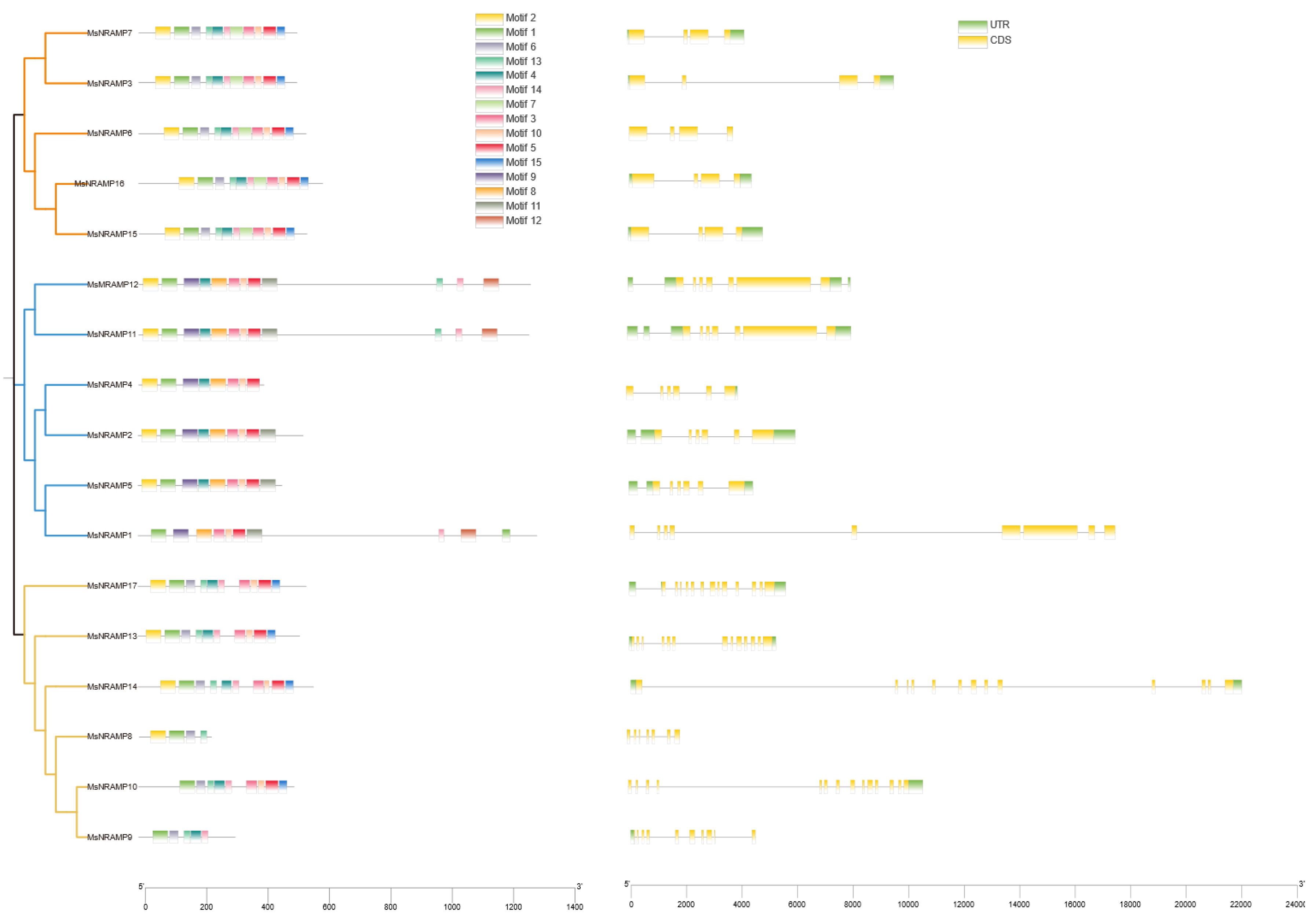

Miscanthus, as is shown in

Figure 2a, to better understand their evolution together with their function. The full length of protein sequences of seven OsNRAMPs and seventeen MsNRAMPs were used to construct the phylogenetic tree (

Figure 2b). OsNRAMPs are served as a reference for classification. 12 conserved motifs were identified by MEME across the different groups of MsNRAMPs is shown in

Figure 3.

Based on the results of the phylogenetic tree, the MsNRAMP family is divided into two major groups, with Group I further subdivided into two subgroups, Ia and Ib. The motifs analysis indicates that, with the exception of the presumably functionally incomplete

MsNRAMP8 and

MsNRAMP9: all

MsNRAMPs share motifs 1 and 14. Excluding

MsNRAMP1, all

MsNRAMPs share motif 4, Group I share motif 15, and Group II shares motif 11. Proteins in Group Ia have identical motifs with a tandem structure of motifs 2, 1, 6, 13, 4, 14, 7, 3, 10, 5, and 15; Group Ib proteins typically have a tandem structure of motifs 1, 6, 4. Group II displays a sequentially tandem structure of motifs 9, 4, 8, 14, 10, and 5. Genes within the same group also have similar structural characteristics: Group Ia generally consists of four exons, while Group Ib typically contains a greater number of shorter, dispersed exons. Motif 3 includes the binding site for ions on NRAMP [

5].

2.3. Collinearity Analysis of NRAMP in Miscanthus and Closely Related Poaceae Species

The process of divergence between

Miscanthus sinensis,

Saccharum officinarum and

Sorghum bicolor is a compelling topic in the study of plant evolution. According to existed research, the ancestral species of

Miscanthus sinensis and

Saccharinae diverged from the ancestral species of Sorghum bicolor between 6.1 and 5.5 million years ago [

13]. This process involved genome duplication and chromosomal rearrangements. To explore the evolutionary process of the NRAMP family genes within this context, collinearity analysis was performed.

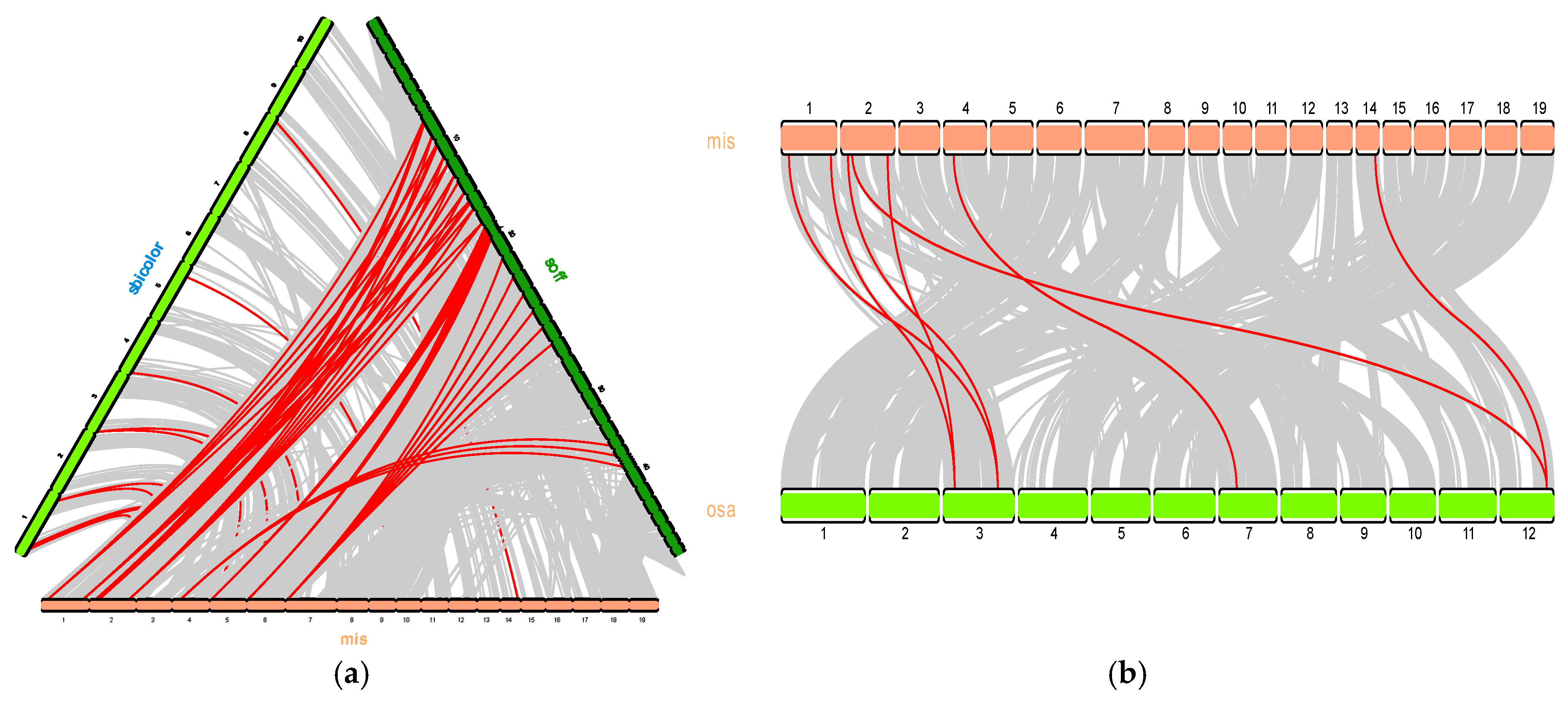

As shown in

Figure 4a, the identification of 12 collinear gene pairs between

Miscanthus sinensis and

Sorghum bicolor. A limited number of gene duplications have been observed transitioning from

Sorghum bicolor to

Miscanthus sinensis, suggests that

MsNRAMP1 and

MsNRAMP2, as well as

MsNRAMP4 and

MsNRAMP5, are the result of tandem duplication events. In contrast, 62 gene pairs exhibit collinearity between

Miscanthus sinensis and

Saccharum officinarum, with a substantial number of gene duplications occurring from

Miscanthus sinensis to

Saccharum officinarum.

MsNRAMP3 and

MsNRAMP7 are part of chromosomal segmental duplications, as indicated by their collinearity with a single homologous gene in

Saccharum officinarum.

As shown in

Figure 4c. Six pairs of

Oryza sativa and

Miscanthus sinensis NRAMP genes showed homology was summarized in

Table 2. The Ka/Ks values of

MsNRAMP are all less than 1, indicating that they are under purify selection during the evolutionary process, which implies that the

MsNRAMP protein family plays a beneficial role in the adaptation of plants to their environment.

MsNRAMP3,

MsNRAMP6,

MsNRAMP7, and

OsNRAMP3 exhibit high homology. As

OsNRAMP3 has been reported as a regulatory gene in rice in response to manganese ions in the environment [

14]. Induction of

OsNRAMP3 gene expression following chromium treatment in rice has been shown to alleviate cadmium toxicity [

15].

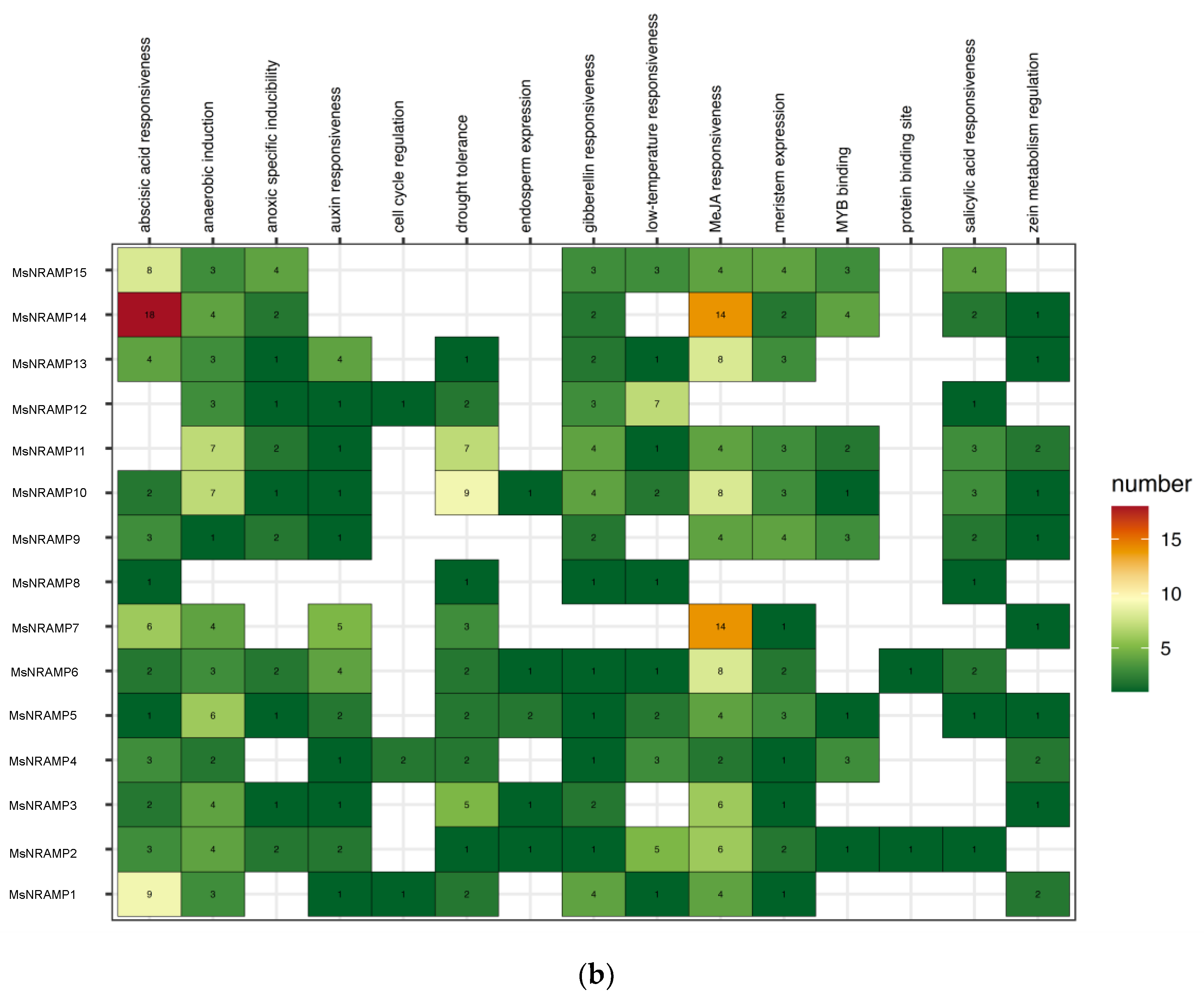

2.4. Cis-Acting Elements of MsNRAMPs and Transcriptomic Analysis

Utilizing PLANTCARE, we analyzed the promoter sequences of

MsNRAMPs, specifically, focusing on counting the number of elements within these sequences that respond to external signals, as illustrated in

Figure 6.

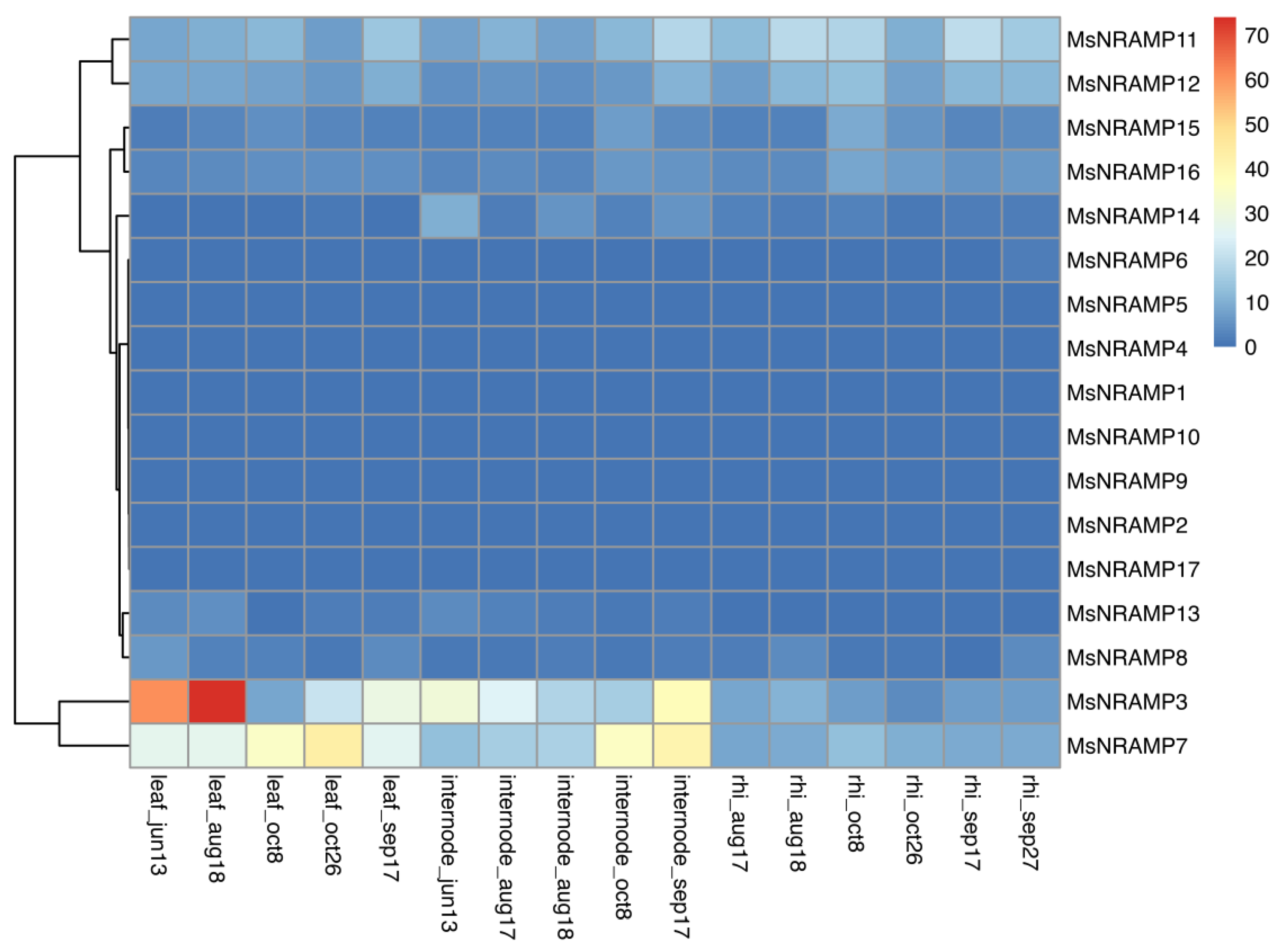

The raw transcriptome sequencing data was retrieved from the NCBI's Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database with the accession number PRJNA575573. The processed data is presented as a heatmap in

Figure 7, which illustrates that among the many

MsNRAMPs, only

MsNRAMP3 and

MsNRAMP7 have relatively high expression levels. These expression levels are primarily localized in leaf and internode, with comparatively low levels observed in the rhizome.

14 out of the 15

MsNRAMPs have gibberellin response elements in their upstream promoters, while thirteen possess MeJA response elements. This finding suggests that

MsNRAMPs may be regulated by stress signaling pathways. A recent study indicates that gibberellins (GA) can negatively regulate the expression of

OsNRAMP5, subsequently reducing rice’s tolerance to aluminum toxicity [

17].

MsNRAMP14 and MsNRAMP8 feature numerous ABA and MeJA response elements in their promoter regions, however, their transcripts are scarcely expressed, implying the potential for their induced expression.

3. Discussion

3.1. From Transcription Factor EIN2 to NRAMP

OsEIN2 is the core regulatory factor in the ethylene (ET) defense signaling pathway of

Oryza sativa [

18]. Multiple sequence alignments reveal high homology between the NRAMP family in

Miscanthus sinensis and the

OsEin2 homologous genes, with

OsEin2 containing an NRAMP domain. In

Arabidopsis, salt stress downregulates the expression of

AtEin2 [

19], and

Oryza sativa overexpressing

OsEin2 exhibit increased sensitivity to salt stress [

20]. Future research could explore whether

NRAMP expression is upregulated under salt stress or heavy metal treatment and further investigate the potential negative feedback mechanism in the EIN2-NRAMP pathway. Additionally, many ABA (abscisic acid) and MeJA (methyl jasmonate) response elements have been identified upstream of the

MsNRAMP promoter. In Arabidopsis, AtEin2 can respond to ABA [

20], but there is no direct molecular evidence demonstrating the involvement of NRAMP transporters in the ABA pathway. In

Miscanthus, NRAMP exhibits specialized expression, with only two of its many homologous genes expressed at normal levels, making it an excellent model for studying this pathway.

3.2. Transporter Function Inference Based on Expression Data

After being absorbed by plants, heavy metals such as cadmium and mercury tend to accumulate in the leaves through the process of transpiration, while lead preferentially deposits at the leaf base or in the roots. In rice, NRAMP5 is known to mediate the transport of the heavy metal cadmium. Both leaves and roots are sites of highly active metabolic processes [

8]. However, it has been observed that MsNRAMP3 and MsNRAMP7 exhibit minimal expression in the roots, while their expression levels in the leaves are significantly higher than those in the rhizome. Based on these observations, it is reasonable to speculate that NRAMP transporters may be activated by signals or molecules with high mobility.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Identification of NRAMP Family Genes and Protein Property Prediction

The genome and annotation data of

Miscanthus sinensis were obtained from the Plant JGI database Phytozome v13. Putative

MsNRAMP genes were identified based on NRAMP genes from

Oryza sativa and

Arabidopsis thaliana. The candidate

NRAMP genes were identified using the BLASTP method, retaining those with an e-value of 10-5 and scores greater than 200. The Conserved Domain Database(CDD) was used for trimming the obtained protein sequences [

21]. Meanwhile, the R packages Peptides was employed to caculate the physicochemical properties of the proteins, TMHMM v2.0 was used to predict transmembrane domains [

22], CELLO v.2.5 was utilized for subcellular localization [

23], and TBtools v.2110 was used for visualization [

24].

4.2. Chromosome Location and Phylogenetic Analysis

Chromosome locations and coding sequences of candidate MsNRAMP genes were obtained from genomic annotation data. The visualization of MsNRAMP genes was accomplished using by TBtools v.2110.

Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using MEGA11 [

25]. The method involved aligning the protein sequences of selected genes with Multiple Sequence Comparison(muscle), constructing a phylogenetic tree using the Neighbor-Joining model with 1000 bootstrap replicates, and visualizing the relationships by ITOL v2.

4.3. Motif Analysis

The Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation v5.5.7 (MEME) was used to predict the motifs of the selected genes (

https://memesuite.org/me-me/tools/meme; accessed on 6 November 2024) [

26]. The number of motifs to be identified was set to 13. Subsequently, TBtools version 2.1.1 was employed for visualization.

4.4. Cis-acting Elements Analysis of MsNRAMP Genes

The 2000 bp upstream of the coding sequences (CDS) were extracted for promoter analysis. The sequences were submitted to the online website PlantCARE (

http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare; accessed on 6 November 2024) [

27]. The results obtained were further filtered, and the R package ggplot2 was employed to plot and count the number of cis-acting elements.

4.5. Genome Collinearity Analysis

Genome and annotation data for Oryza sativa , Saccharum officinarum and Sorghum bicolor was obtained from the Plant JGI database Phytozome v13 (

https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov; accessed on 9 November 2024). The Software Diamond was utilized for aligning sequences between species, with an e-value threshold set at 10

-5 [

28]. Subsequently, the collinear gene pairs were calculated using the quick run MCScanX wrapper module in TBtools [

29], and visualization was accomplished with the R package Rcircos.

4.6. Transcriptional Expression Analysis

The raw transcriptome sequencing files were obtained from NCBI's Sequence Read Archive database (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=PRJNA575573; accession number: PRJNA575573). For the preprocessing of Miscanthus expression levels, we employed sequence alignment software HISAT2, sequence editing software SAMtools, and transcript quantification software Subread [

30,

31,

32].

Finally, genes from different periods and tissues were visualized in a heatmap, with the data based on transcript FPKM values. (FPKM = 10^9 * C / (N * L), in which C represents the read count of the gene, N represents the total read count, and L represents the length of the gene.)

5. Conclusions

In this study, we identified 17 NRAMP family genes in Miscanthus sinensis, designated as MsNRAMP1 to MsNRAMP17. Identification reveals that these genes are widely distributed across the Miscanthus genome and exhibit a high degree of conservation in their secondary structure and ion-binding sites, characteristic of the Leu-T domain.

The expression analysis indicated that only

MsNRAMP3 and

MsNRAMP7 are significantly expressed under normal conditions, suggesting potential functional specialization within the family. Nevertheless, the expression of all

OsNRAMPs is reportedly inducible, as evidenced by both literature reviews and the analysis of standard rice transcriptome data [

33,

34,

35].

Notably, MsNRAMP8 and MsNRAMP14, which harbor numerous ABA and MeJA response elements in their promoters, may be involved in stress signaling pathways, highlighting the complexity of Miscanthus's response to environmental cues.

Phylogenetic analysis and motif prediction have allowed us to classify the MsNRAMPs into two major groups, with Group I showing closer homology to OsNRAMPs from Oryza sativa. This classification, along with the identification of conserved motifs, provides a foundation for further functional characterization of these genes. Collinearity analysis between Miscanthus sinensis and Oryza sativa revealed 7 homologous gene pairs of NRAMPs, reinforcing the evolutionary relationship between these species and the conservation of NRAMP function.

The multiple sequence alignment of MsNRAMPs with those from other species highlights the conservation of their secondary structures, which is essential for their role in metal ion transport. The identification of key residues involved in metal cation and proton binding provides insights into the molecular basis of their transport activity. Our results on the potential roles of MsNRAMP8 and MsNRAMP9, which lack the typical number of transmembrane domains, suggest that not all NRAMP family members may function independently as transporters.

In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive characterization of the NRAMP family in Miscanthus sinensis, shedding light on their potential roles in metal ion homeostasis and stress response. The identified genes and their functional annotations lay the groundwork for future studies aimed at enhancing our understanding of Miscanthus's adaptability to heavy metal stress and its implications for phytoremediation and bioenergy production.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Weixiong Long and Xiaojue Peng designed the study and wrote the manuscript, Wei Chen performed most of the experiments and helped write the manuscriptand wrote the manuscript, Jiawei Niu, Suping Ying and Jianzhao assisted in the data analysis.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32172074, 31760377), Key Projects of Jiangxi Natural Science Foundation (No. 20224ACB205005).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABA |

Abscisic Acid |

| GA |

Gibberellin |

| MeJA |

Methyl Jasmonate |

| NRAMP |

natural resistance associated macrophage protein |

References

- Mitros, T.; Session, A.M.; James, B.T.; Wu, G.A.; Belaffif, M.B.; Clark, L.V.; Shu, S.; Dong, H.; Barling, A.; Holmes, J.R.; et al. Genome biology of the paleotetraploid perennial biomass crop Miscanthus. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowski, I.; Scurlock, J.M.O.; Lindvall, E.; Christou, M. The development and current status of perennial rhizomatous grasses as energy crops in the US and Europe. Biomass Bioenergy 2003, 25, 335–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanat, N.; Austruy, A.; Joussein, E.; Soubrand, M.; Hitmi, A.; Gauthier-Moussard, C.; Lenain, J.-F.; Vernay, P.; Munch, J.C.; Pichon, M. Potentials of Miscanthus×giganteus grown on highly contaminated Technosols. J. Geochem. Explor. 2013, 126-127, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellier M, Prive G, Belouchi A. Nramp defines a family of membrane proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1995, 92, 10089–10093.

- Bozzi, A.T.; Gaudet, R. Molecular Mechanism of Nramp-Family Transition Metal Transport. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 166991–166991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenzie, B.; Hediger, M.A. SLC11 family of H + -coupled metal-ion transporters NRAMP1 and DMT1. Pfl?gers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2004, 447, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwal, F.; Riaz, A.; Ali, S.; Zhang, G. NRAMPs and manganese: Magic keys to reduce cadmium toxicity and accumulation in plants. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 921, 171005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.-D.; Gao, W.; Wang, P.; Zhao, F.-J. OsNRAMP5 Is a Major Transporter for Lead Uptake in Rice. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 17481–17490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Guan, M.; Chen, M.; Lin, X.; Xu, P.; Cao, Z. Mutation of OsNRAMP5 reduces cadmium xylem and phloem transport in rice plants and its physiological mechanism. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 341, 122928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockbridge, R.B.; Ramanadane, K.; Liziczai, M.; Markovic, D.; Straub, M.S.; Rosalen, G.T.; Udovcic, A.; Dutzler, R.; Manatschal, C. ; Department of Biochemistry; et al. Editor's evaluation: Structural and functional properties of a plant NRAMP-related aluminum transporter. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wei, Y.Q.; Wu, K.H.; Yan, J.Y.; Na Xu, J.; Wu, Y.R.; Li, G.X.; Xu, J.M.; Harberd, N.P.; Ding, Z.J.; et al. Restriction of iron loading into developing seeds by a YABBY transcription factor safeguards successful reproduction in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 1624–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Wallrad, L.; Wang, Z.; Höller, S.; Ju, C.; Schmitz-Thom, I.; Huang, P.; Wang, L.; Peiter, E.; et al. Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation of NRAMP1 by CPK21 and CPK23 facilitates manganese uptake and homeostasis inArabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang G, Ge C, Xu P, etal. The reference genome of Miscanthus floridulus illuminates the evolution of Saccharinae. Nature Plants, 2021, 7, 608–618.

- Yamaji, N.; Sasaki, A.; Xia, J.X.; Yokosho, K.; Ma, J.F. A node-based switch for preferential distribution of manganese in rice. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Z.; E, Y.; Meng, J.; He, T. Combined application of biochar and sulfur alleviates cadmium toxicity in rice by affecting root gene expression and iron plaque accumulation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 266, 115596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrnstorfer I, Geertsma E, Pardon E. Crystal structure of a SLC11 (NRAMP) transporter reveals the basis for transition-metal ion transport. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 2014, 20:990.

- Lu, L.; Chen, X.; Tan, Q.; Li, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Song, Y.; Zeng, R. Gibberellin-Mediated Sensitivity of Rice Roots to Aluminum Stress. Plants 2024, 13, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu J, Liu Z, Xie J, etal. Dual impact of ambient humidity on the virulence of Magnaporthe oryzae and basal resistance in rice[J]. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2022, 45, 3399–3411.

- Wang Y, Liu C, Li K, etal. Arabidopsis EIN2 modulates stress response through abscisic acid response pathway[J]. Plant Molecular Biology, 2007, (6):633-644.

- Yang C, Ma B, He S, etal. MAOHUZI6/ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3-LIKE1 and ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3-LIKE2 Regulate Ethylene Response of Roots and Coleoptiles and Negatively Affect Salt Tolerance in Rice.[J]. Plant Physiology, 2015, 169, 148–165.

- Yang M, Derbyshire M K, Yamashita R A, Marchler-Bauer A. NCBI's Conserved Domain Database and Tools for Protein Domain Analysis. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. 2020, 69:90-98.

- Krogh, A.; Larsson, B.; von Heijne, G.; Sonnhammer, E.L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden markov model: Application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 305, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Lin, C.; Hwang, J. Predicting subcellular localization of proteins for Gram-negative bacteria by support vector machines based on n-peptide compositions. Protein Sci. 2004, 13, 1402–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osorio, D.; Rondón-Villarreal, P.; Torres, R. Peptides: A Package for Data Mining of Antimicrobial Peptides. R J. 2015, 7, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, w202–w208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchfink, B.; Reuter, K.; Drost, H.-G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; DeBarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.-H.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchfink, B.; Reuter, K.; Drost, H.-G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. The Subread aligner: fast, accurate and scalable read mapping by seed-and-vote. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Huang, R.; Liu, L.; Tang, G.; Xiao, J.; Yoo, H.; Yuan, M. The rice heavy-metal transporter OsNRAMP1 regulates disease resistance by modulating ROS homoeostasis. Plant, Cell Environ. 2022, 45, 1109–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Yu, Y.; Dai, X.; Gong, C.; Gu, D.; Xu, E.; Liu, Y.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, P.; et al. The tonoplast-localized transporter OsNRAMP2 is involved in iron homeostasis and affects seed germination in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 4839–4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, A.; Yamaji, N.; Yokosho, K.; Ma, J.F. Nramp5 Is a Major Transporter Responsible for Manganese and Cadmium Uptake in Rice. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2155–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).