Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

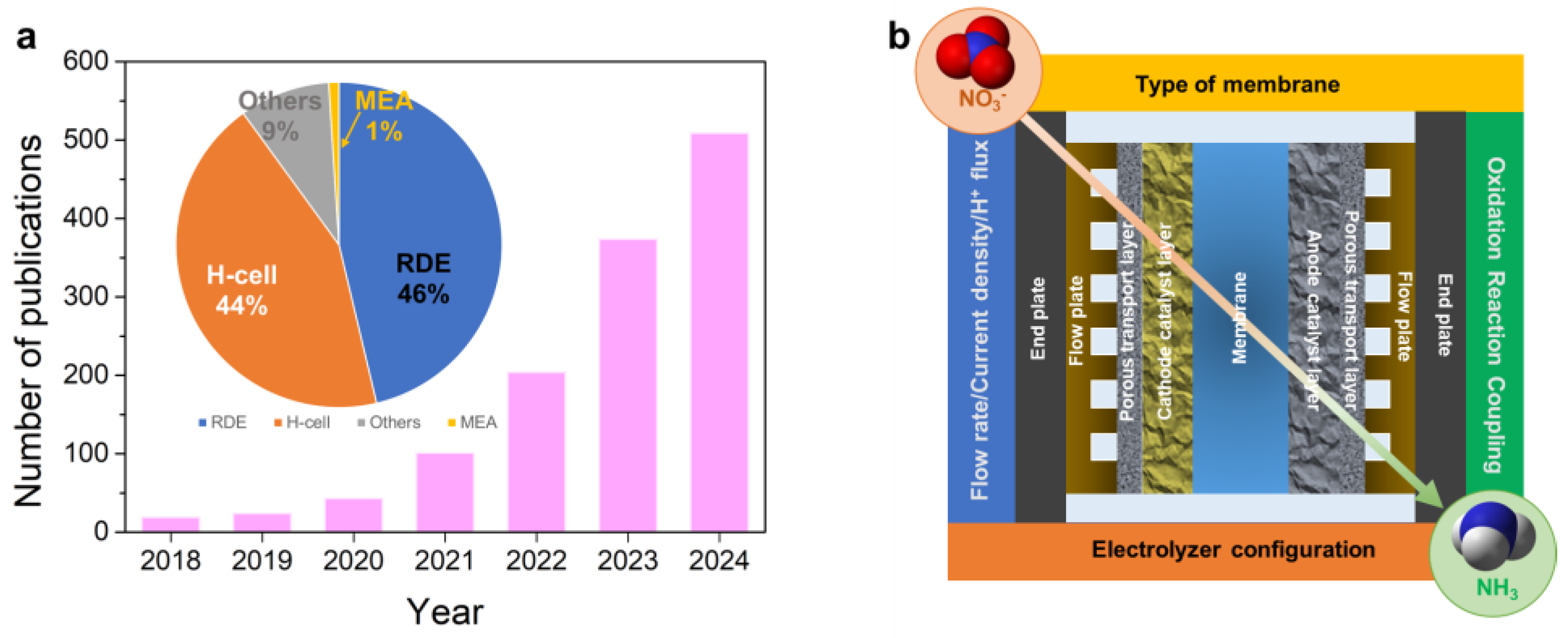

1. Introduction

2. Catalyst Innovations in MEA Systems

2.1. Heterostructured Catalysts

2.2. Single-Atom Catalysts (SAC)

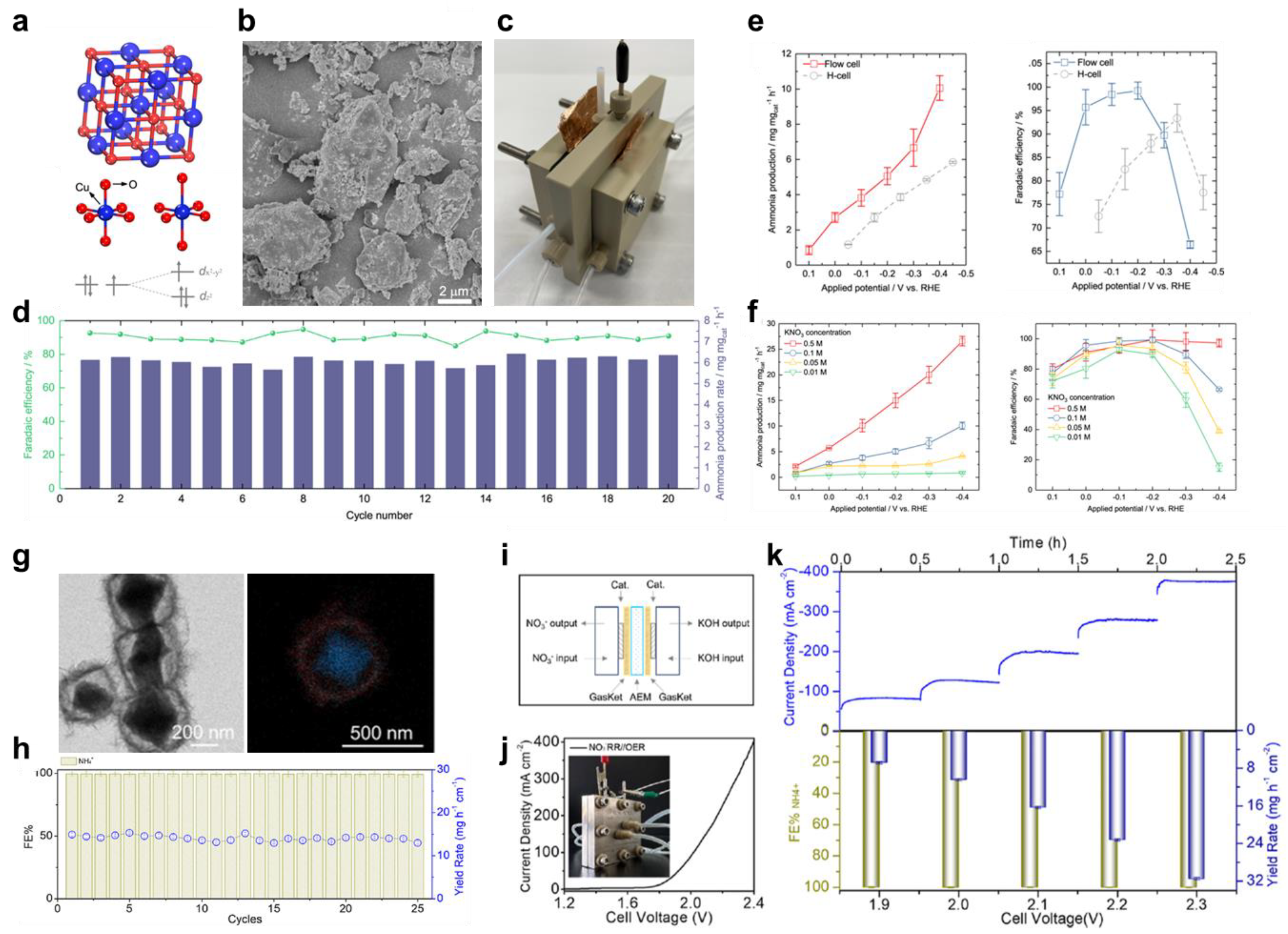

2.3. Cascade Catalysis with Yolk-Shell Nanostructures

2.4. Summary of Innovations in Catalysis

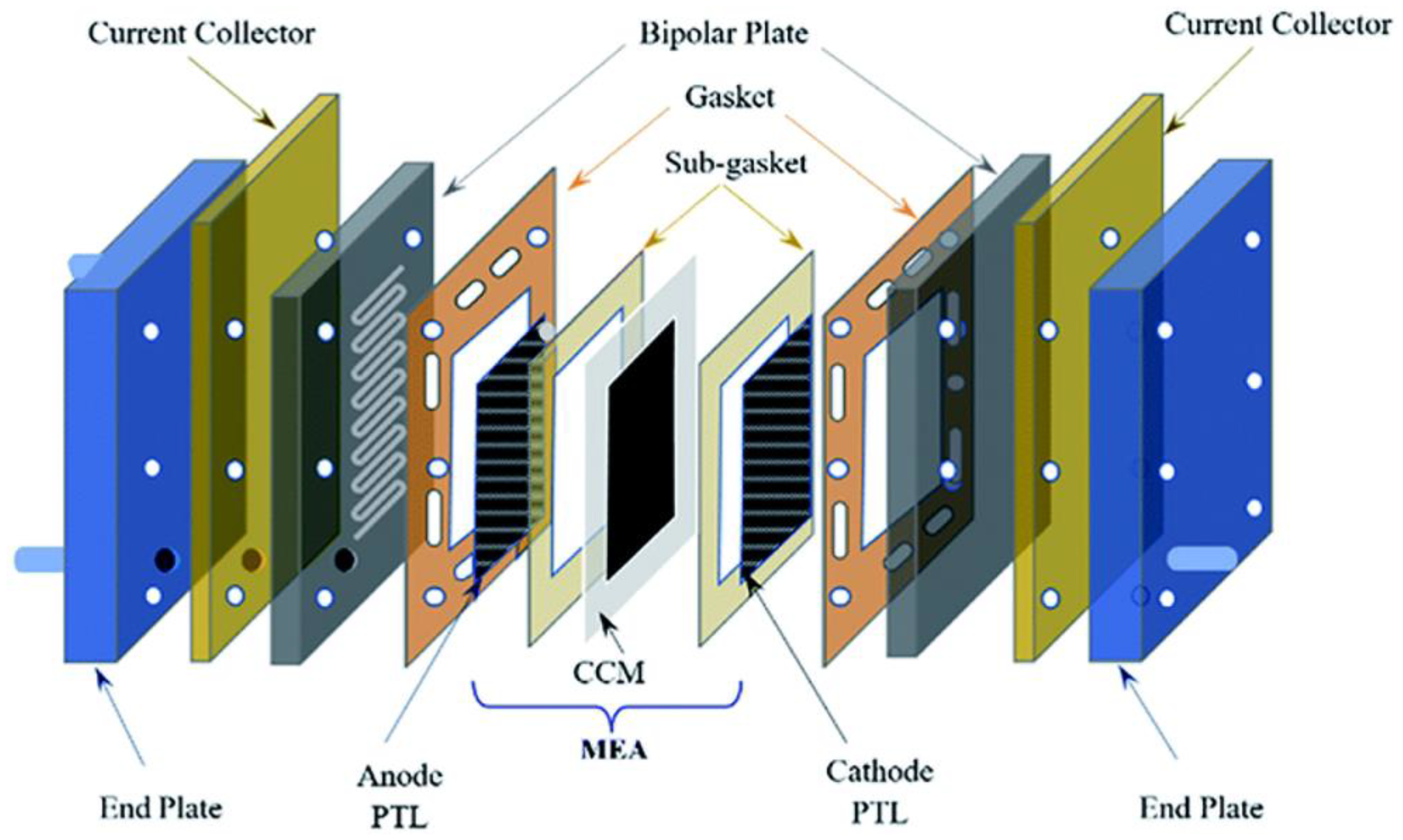

3. Membrane Electrode Assembly for Electrochemical Nitrate Reduction

3.1. MEA Configuration and Performance Indicators

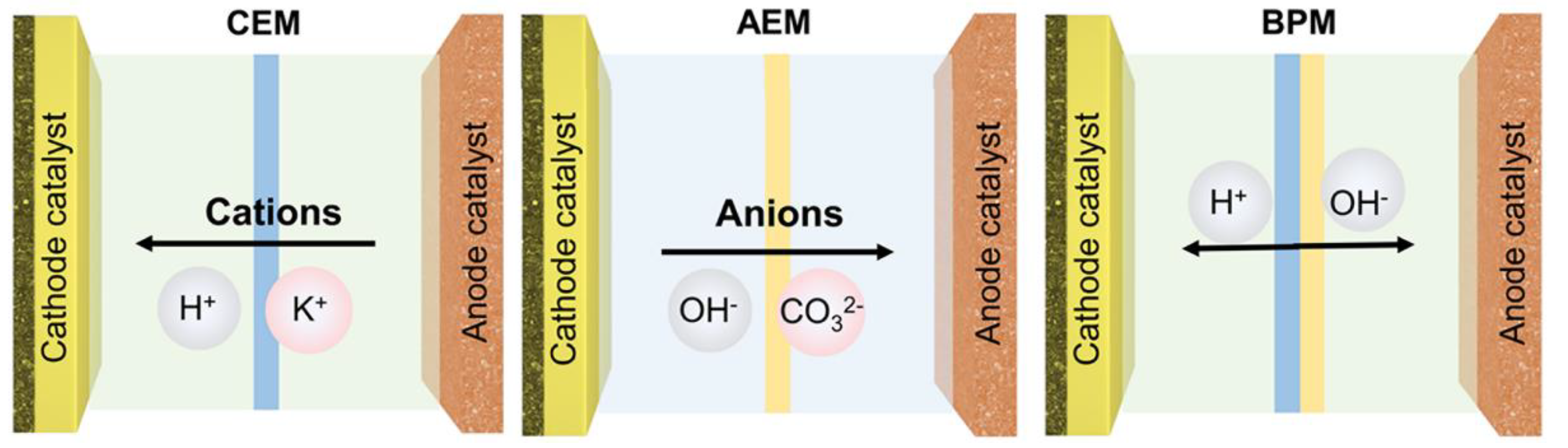

3.2. Role of Membranes in MEA Design

| Catholyte | Anolyte | Membrane type | Cathode material | Anode material | Counter oxidation reaction | Current Density | Voltage | NH3 FE | NH3 Yield | Ref. |

| 1 M KOH with 0.1 M KNO3 | 1 M KOH | CEM (Nafion 117) | Oxide-Derived Cu (OD-Cu) Mesh (40 mesh) | IrOx/Ti mesh | OER | 400 mA cm−2 | n/a | 90% | 1.6 mmol h−1 cm−2 | [116] |

| 1 M KOH with 2000 ppm NO3− | 1 M KOH | AEM (FAA-3-50) | NiCo LDH on Cu nanowires (NiCo LDH/Cu NW) | Au-Ni(OH)2 | OER | ~300 mA cm−2 | 2 V | ~90% | ~1.6 mmol h−1 cm−2 | [112] |

| 2000 ppm NO3− without supporting electrolyte | 0.258 M NaOH | CEM (Nafion-117) with PSE layer | Ru-dispersed Cu nanowires (Ru-CuNW) | IrO2 | OER | 100 mA cm−2 | ~2.5 V | 92% | Not explicitly stated | [109] |

| 1 M KOH with 0.1 M KNO3 | 1 M KOH | AEM (FAA-3-PK-130) | CoP-Cu/Co(OH)2 heterojunction | S-(Ni,Fe)OOH | OER | 275 mA cm−2 (60 °C) | 1.8 V | ~90 % (60 °C) | ~1.4 mmol h−1 cm−2 (60 °C) | [117] |

| 1 M KOH with 0.1 M KNO3 | 1 M KOH with 1 M ethylene glycol | AEM (X37-50 grade T) | Oxygen-deficient NiCo2O4 porous nanowires (Vo-NiCo2O4/NF) | Vo-NiCo2O4/NF | Ethylene Glycol Oxidation Reaction (EGOR) | 100 mA cm−2 | 1.53 V | 96.3% | 0.36 mmol h−1 cm−2 | [115] |

| 1 M KCl with 70 mM KNO30.5 M K2CO3 | 1 M KOH | BPM (Fumasep FBM) | Cu nanoparticles on carbon paper | Ni foam | OER | 200 mA cm−2 | ~5.5 V | 60.8% | Not explicitly stated | [114] |

| 0.5 M KOH with 0.1 M KNO3 | 0.5 M KOH | AEM (Fumasep FAA-3) | Cu2O@CoO yolk-shell nanocube | IrO2 | OER | ~750 (375) mA cm−2 | 1.9 V (2.3 V) | >99.85% | 6.82 (31.50) mg h−1 cm−2 | [55] |

| 1 M NaOH + 200 ppm of NO3- | 1 M NaOH | AEM (Not specified) | Cu3P-Ni2P | Ir | OER | 575 mA cm−2 | 2.6 V | 72% | 1.9 mmol h−1 cm−2 | [110] |

| 1 M KOH with 0.1 M KNO3 | 1 M KOH | AEM (Fumasep FAA-3-50) | Co nanoparticles (CoNPs/CF) | Ni foam | OER | 200 mA cm−2 | n/a | 85.42% | 13.55 mg h−1 cm−2 | [113] |

| 1 M KOH with 2 M KNO3 | 1 M KOH | BPM (Fumasep FME) | Co–Cu mixed single-atom catalyst | Commercial Dimensionally Stable Anode (DSA) mesh | OER | 100 mA cm−2 | From 3.5 to 4.5 V | From 85 to 65 % | 1.03 M NH3 after 32 h | [88] |

| 1 M KOH with 0.1 M KNO3 | 1 M KOH | CEM (Nafion 115) | Sputtered Cu | Ni foam | OER | 395 mA cm−2 | 3.5 V | 91% | 30.26 mg h−1 cm−2 | [118] |

| 1 M KOH with 0.1 M KNO3 | 1 M KOH with 0.33 M glycerol | AEM (PK-130, JBOKE New Materials Technology Co., LTD.) | Pd nanoparticles on Cu foam | NiCo2O4 | Glycerol Oxidation Reaction (GOR) | ~150 mA cm−2 | 1.6 V | 96% | ~20 mg h−1 cm−2 | [111] |

3.3. Optimization Through Operating Variations

3.4. Coupling Counter Reactions

3.5. Functionalized Electrolyzer Configurations

5. Discussion and Future Directions

5.1. Advancements in Electrolyzer Designs

5.2. Catalyst Innovations Catalyst Innovation

- Heterostructured Catalysts: Cu-Ni phosphide catalysts have demonstrated FE exceeding 90% and ammonia yield rates surpassing 1.9 mmol·h−1·cm−2 in PEMEA systems.

- Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs): Tandem catalytic mechanisms of SACs have achieved FE as high as 96%, optimizing nitrate-to-ammonia conversion by leveraging site-specific activity.

- Yolk-Shell Nanostructures: Cu2O@CoO yolk-shell nanocubes have exhibited over 99% FE, coupled with record-high ammonia yield rates in MEA systems.

5.3. Integration with Wastewater Treatment

5.4. Optimizing Reaction Conditions

5.5. Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.-H.; Vu, M.H.; Lim, J.; Do, T.-O.; Hatzell, M.C. Influence of carbonaceous species on aqueous photo-catalytic nitrogen fixation by titania. Faraday Discussions 2019, 215, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.A.; Hortance, N.M.; Liu, Y.-H.; Lim, J.; Hatzell, K.B.; Hatzell, M.C. Opportunities for intermediate temperature renewable ammonia electrosynthesis. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2020, 8, 15591–15606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.H.; Mahlia, T.M.I.; Mofijur, M.; Rizwanul Fattah, I.; Handayani, F.; Ong, H.C.; Silitonga, A. A comprehensive review on the recent development of ammonia as a renewable energy carrier. Energies 2021, 14, 3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Hera, G.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, G.; Viguri, J.R.; Galán, B. Flexible Green Ammonia Production Plants: Small-Scale Simulations Based on Energy Aspects. Environments 2024, 11, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, K.S.; Hamid, M.A.; Ng, D.K. Systematic decision-making framework for evaluation of process alternatives for sustainable ammonia (NH3) production. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 64, A6–A17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akay, G. Hydrogen, Ammonia and Symbiotic/Smart Fertilizer Production Using Renewable Feedstock and CO2 Utilization through Catalytic Processes and Nonthermal Plasma with Novel Catalysts and In Situ Reactive Separation: A Roadmap for Sustainable and Innovation-Based Technology. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, L. Enhanced Electrocatalytic Nitrate Reduction to Ammonia Using Functionalized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube-Supported Cobalt Catalyst. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.N.; Mohammad, F. Eutrophication: challenges and solutions. In Eutrophication: Causes, Consequences and Control: Volume 2; 2014; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloantoa, K.M.; Khetsha, Z.P.; Van Heerden, E.; Castillo, J.C.; Cason, E.D. Nitrate water contamination from industrial activities and complete denitrification as a remediation option. Water 2022, 14, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, L.; Boicenco, L.; Pantea, E.; Timofte, F.; Vlas, O.; Bișinicu, E. Modeling Dynamic Processes in the Black Sea Pelagic Habitat—Causal Connections between Abiotic and Biotic Factors in Two Climate Change Scenarios. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya-Rodríguez, F.; Durán-Álvarez, J.C.; Drisya, K.; Zanella, R. The challenges of integrating the principles of green chemistry and green engineering to heterogeneous photocatalysis to treat water and produce green H2. Catalysts 2023, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Yang, L.; Ye, L.; Mei, M.; Zhu, W. Electrode Materials for NO Electroreduction Based on Dithiolene Metal–Organic Frameworks: A Theoretical Study. Catalysts 2024, 14, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Du, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Cao, P.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, X.; Liu, N. Co-Carbonization of Straw and ZIF-67 to the Co/Biomass Carbon for Electrocatalytic Nitrate Reduction. Catalysts 2024, 14, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, K.-Y.; Wang, J.-J.; Fang, X.; Li, Z.-X. One Bicopper Complex with Good Affinity to Nitrate for Highly Selective Electrocatalytic Nitrate Reduction to Ammonia. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-H.; Lee, H.; Huang, X.; Choi, J.H.; Chen, C.; Kang, J.K.; O’Hare, D. Energy-efficient electrochemical ammonia production from dilute nitrate solution. Energy & Environmental Science 2023, 16, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Chen, Q.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, D.; Han, N.; Chen, Z. Repurposing mining and metallurgical waste as electroactive materials for advanced energy applications: advances and perspectives. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Liu, C.-Y.; Park, J.; Liu, Y.-H.; Senftle, T.P.; Lee, S.W.; Hatzell, M.C. Structure sensitivity of Pd facets for enhanced electrochemical nitrate reduction to ammonia. ACS Catalysis 2021, 11, 7568–7577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Fernández, C.A.; Lee, S.W.; Hatzell, M.C. Ammonia and Nitric Acid Demands for Fertilizer Use in 2050. ACS Energy Letters 2021, 6, 3676–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, S.; Jiang, R.; Ma, H. Cu modified Pt nanoflowers with preferential (100) surfaces for selective electroreduction of nitrate. Catalysts 2019, 9, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, K.H.; Rao, R.R.; Park, D.G.; Choi, W.H.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, D.W.; Jung, D.H.; Stephens, I.E.L.; Durrant, J.R.; et al. A hydrogen radical pathway for efficacious electrochemical nitrate reduction to ammonia over an Fe-polyoxometalate/Cu electrocatalyst. Mater Horiz 2024, 11, 4115–4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Wu, H.; Liu, N.; Wang, Q.; Shang, Y.; Zheng, J. Novel 2D Material of MBenes: Structures, Synthesis, Properties, and Applications in Energy Conversion and Storage. Small 2024, 20, 2405870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, R.; Guo, Y.; Zhi, C. Ammonia Synthesis from Nitrate Reduction by the Modulation of Built-in Electric Field and External Stimuli. EES Catalysis 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, H.; Xie, M.; Wang, P.; Jin, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, M.; Li, P.; Yu, G. Thermally Enhanced Relay Electrocatalysis of Nitrate-to-Ammonia Reduction over Single-Atom-Alloy Oxides. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2024, 146, 7779–7790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, S.; Cao, R.; Han, Y.; Shang, J.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, W.; Liu, G. Electrocatalysts with atomic-level site for nitrate reduction to ammonia. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Liang, T.; You, J.; Huo, Q.; Qi, S.; Zhao, J.; Meng, N.; Liao, J.; Shang, C.; Yang, H. Coordination environment-tailored electronic structure of single atomic copper sites for efficient electrochemical nitrate reduction toward ammonia. Energy & Environmental Science 2024, 17, 8360–8367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Deng, J.; Liu, Y.; Jing, L.; Hou, Z.; Pei, W.; Dai, H. Single-atom catalysts: Preparation and applications in environmental catalysis. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Sun, Y.; Sun, H.; Pang, Y.; Xia, S.; Chen, T.; Zheng, S.; Yuan, T. Research progress in ZIF-8 derived single atomic catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. Catalysts 2022, 12, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ma, P.; Yang, J.; Krishnan, S.; Kesavan, K.S.; Xing, R.; Liu, S. Facile construction of three-dimensional heterostructured CuCo2S4 bifunctional catalyst for alkaline water electrolysis. Catalysts 2023, 13, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis, I.; Rodriguez, J.J.; Mohedano, A.F.; Diaz, E. Activity and stability of Pd bimetallic catalysts for catalytic nitrate reduction. Catalysts 2022, 12, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.; Sadiq, I.; Ali, S.A.; Ahmad, T. Bismuth-based multi-component heterostructured nanocatalysts for hydrogen generation. Catalysts 2023, 13, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, F.; Yao, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhu, G.; Jia, G.; Bai, Z.; Dou, S. A strongly coupled metal/hydroxide heterostructure cascades carbon dioxide and nitrate reduction reactions toward efficient urea electrosynthesis. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2024, 63, e202410105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Júnior, A.A.d.T.; Ladeira, Y.F.X.; França, A.d.S.; Souza, R.O.M.A.d.; Moraes, A.H.; Wojcieszak, R.; Itabaiana Jr, I.; Miranda, A.S.d. Multicatalytic hybrid materials for biocatalytic and chemoenzymatic cascades—Strategies for multicatalyst (Enzyme) co-immobilization. Catalysts 2021, 11, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Mayoral, E.; Godino-Ojer, M.; Matos, I.; Bernardo, M. Opportunities from Metal Organic Frameworks to Develop Porous Carbons Catalysts Involved in Fine Chemical Synthesis. Catalysts 2023, 13, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Han, G.H.; Seo, J.Y.; Kang, M.; Seo, M.-g.; Choi, Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Ahn, S.H. Improved CO Selectivity via Anion Exchange Membrane Electrode Assembly-Type CO2 Electrolysis with an Ionomer-Coated Zn-Based Cathode. International Journal of Energy Research 2024, 2024, 8984734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkarev, A.S.; Pushkareva, I.V.; du Preez, S.P.; Bessarabov, D.G. PGM-free electrocatalytic layer characterization by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of an anion exchange membrane water electrolyzer with Nafion ionomer as the bonding agent. Catalysts 2023, 13, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Kim, T.; Jung, K.Y.; Park, K.T. Recent progress in electrocatalytic CO2 reduction to pure formic acid using a solid-state electrolyte device. Catalysts 2023, 13, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Li, B.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Fu, W.-J.; Zhou, G.; Ma, J.; Yin, S.; Yuan, W.; Miao, S. Ammonia recovery from nitrate-rich wastewater using a membrane-free electrochemical system. Nature Sustainability 2024, 7, 1251–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Ma, Q.; Wang, Z.; Rittmann, B.E.; Zhang, W. Direct electrosynthesis and separation of ammonia and chlorine from waste streams via a stacked membrane-free electrolyzer. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajalekshmi, S.; Kumar, S.M.S.; Pandikumar, A. Exploring transition metal hydroxides performance in membrane-free electrolyzer based decoupled water splitting for step-wise production of hydrogen and oxygen. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 496, 154215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Qiao, L.; Peng, S.; Bai, H.; Liu, C.; Ip, W.F.; Lo, K.H.; Liu, H.; Ng, K.W.; Wang, S. Recent advances in electrocatalysts for efficient nitrate reduction to ammonia. Advanced Functional Materials 2023, 33, 2303480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Franch, C.; Palomares, E.; Lapkin, A.A. Simulation of catalytic reduction of nitrates based on a mechanistic model. Chemical engineering journal 2011, 175, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavani, K.; Agarwal, K.; Alam, S.S.; Dinda, S.; Abrar, I. Advances in plastic to fuel conversion: reactor design, operational optimization, and machine learning integration. Sustainable Energy & Fuels 2025, 9, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides-Hernández, J.; Dumeignil, F. From Characterization to Discovery: Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and High-Throughput Experiments for Heterogeneous Catalyst Design. ACS Catalysis 2024, 14, 11749–11779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Xie, K.; Lin, L.; Huo, J.; Zhao, C.; Li, L. Efficient Electrocatalytic N2fixation Over Bc3n2monolayer: A Computational Screening of Single-Atom Catalysts. Available at SSRN 4066356. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zou, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; An, L. Progress and Perspectives in Electroreduction of Low-concentration Nitrate for Wastewater Management. iScience 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.M.; Liu, M.J.; Abels, K.; Kogler, A.; Williams, K.S.; Tarpeh, W.A. Engineering a molecular electrocatalytic system for energy-efficient ammonia production from wastewater nitrate. Energy & Environmental Science 2024, 17, 5691–5705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, L.; Bala Chandran, R. Harnessing photoelectrochemistry for wastewater nitrate treatment coupled with resource recovery. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2021, 9, 3688–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, V.K.; Kumar, M.; An, A.K.; Cetecioglu, Z. Clean energy and resource recovery: wastewater treatment plants as biorefineries. Elsevier, 2021; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J.; Ke, Z.; Tong, L.; Tang, X.; Bai, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, G.; Liang, H. A review of inland nanofiltration and reverse osmosis membrane concentrates management: Treatment, resource recovery and future development. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2024, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Ren, J.-T.; Sun, M.-L.; Yuan, Z.-Y. Valorization systems based on electrocatalytic nitrate/nitrite conversion for energy supply and valuable product synthesis. Chemical Science 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, L.; Wang, H.; Wei, H.; Tang, C.; Li, G.; Dou, Y.; Liu, H.; Dou, S.X. Electrocatalytic nitrogen cycle: mechanism, materials, and momentum. Energy & Environmental Science 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, N.R.; Rather, R.A.; Farooq, A.; Padder, S.A.; Baba, T.R.; Sharma, S.; Mubarak, N.M.; Khan, A.H.; Singh, P.; Ara, S. New insights in food security and environmental sustainability through waste food management. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2024, 31, 17835–17857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, C.A.; Chapman, O.; Brown, M.A.; Alvarez-Pugliese, C.E.; Hatzell, M.C. Achieving Decentralized, Electrified, and Decarbonized Ammonia Production. Environmental Science & Technology 2024, 58, 6964–6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Dai, C.; Zhao, P.; Xi, S.; Ren, Y.; Tan, H.R.; Lim, P.C.; Lin, M.; Diao, C.; Zhang, D. Spin-related Cu-Co pair to increase electrochemical ammonia generation on high-entropy oxides. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Luo, W.; Liu, J.; Jia, B.E.; Lee, C.; Dong, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, B.; Yan, Q. Cascade Electrocatalytic Nitrate Reduction Reaching 100% Nitrate-N to Ammonia-N Conversion over Cu2O@CoO Yolk-Shell Nanocubes. ACS Nano 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, U.; Ahmad, F.; Awais, M.; Naz, N.; Aslam, M.; Urooj, M.; Moqeem, A.; Tahseen, H.; Waqar, A.; Sajid, M. Sustainable Catalysis: Navigating Challenges and Embracing Opportunities for a Greener Future. Journal of Chemistry and Environment 2023, 2, 14–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, S.J.; Al-Shahri, A.S.A.; Glivin, G.; Le, T.; Mathimani, T. A critical review of the state-of-the-art green ammonia production technologies-mechanism, advancement, challenges, and future potential. Fuel 2024, 358, 130307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Huang, H. Adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of Ammonia: Status and challenges. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 154925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiqul Bari, G.A.; Jeong, J.-H. Comprehensive Insight and Advancements in Material Design for Electrocatalytic Ammonia Production Technologies: An Alternative Clean Energy. International Journal of Energy Research 2024, 2024, 5685619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, I.U.; Nasir, Q.; Garba, M.D.; Alharthi, A.I.; Alotaibi, M.A.; Usman, M. A review of preparation methods for heterogeneous catalysts. Mini-Reviews in Organic Chemistry 2022, 19, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, R.; Liu, G.; Zhai, M.; Yu, J. Noble-metal-free single-and dual-atom catalysts for artificial photosynthesis. Advanced Materials 2024, 36, 2301307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, E.; Brown, A.; Nguyen, H.T.M.; He, K.; Batmunkh, M.; Zhong, Y.L. Recent Advances in Selective Chemical Etching of Nanomaterials for High-Performance Electrodes in Electrocatalysis and Energy Storage. Small 2024, 2409552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, C.; Yang, T.; Wei, G.; Huang, J.; Liu, M.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Gao, S. A 3D porous P-doped Cu–Ni alloy for atomic H* enhanced electrocatalytic reduction of nitrate to ammonia. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2024, 12, 7654–7662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Gou, F.; Wang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Shen, W.; He, R.; Li, M. Interface coupling of Ni2P@Cu3P catalyst to facilitate highly-efficient electrochemical reduction of nitrate to ammonia. Applied Surface Science 2024, 648, 159082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

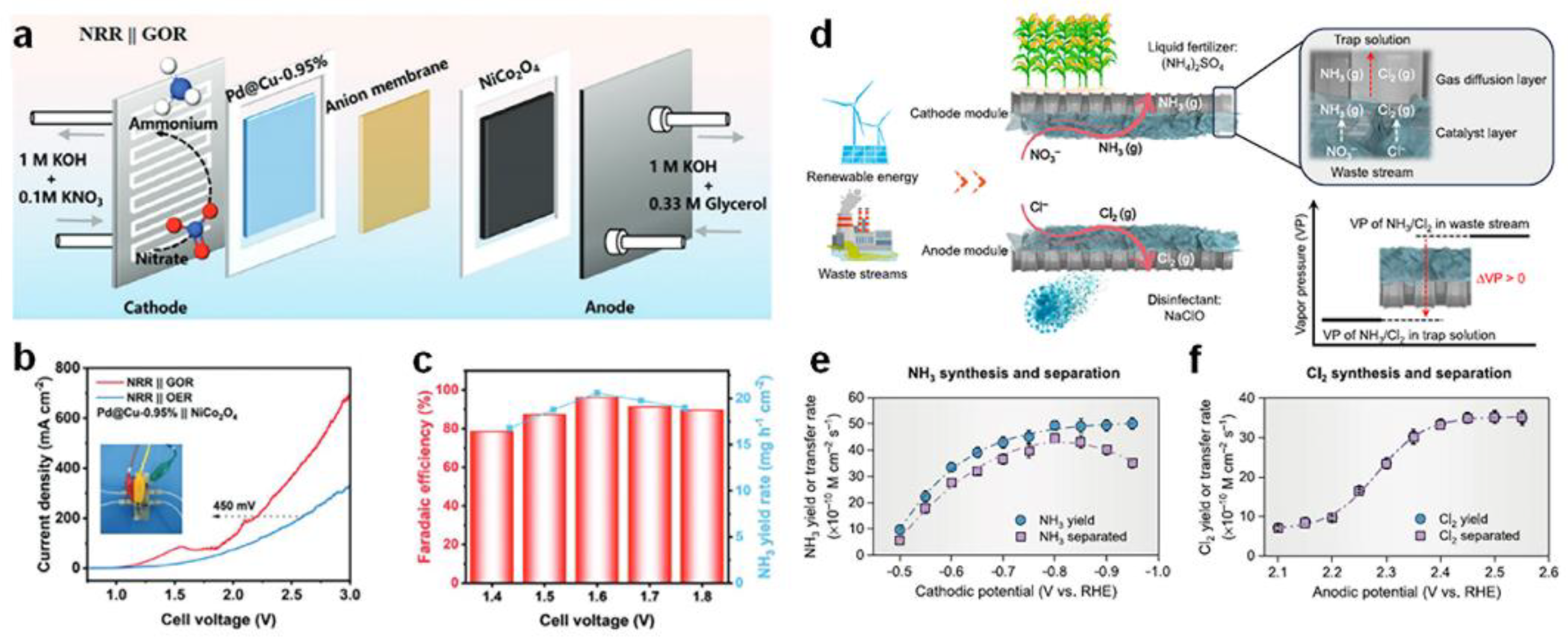

- Jin, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Sun, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, H. Heterostructure Cu3P−Ni2P/CP catalyst assembled membrane electrode for high-efficiency electrocatalytic nitrate to ammonia. Nano Research 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, L.; Liping, S.; Lihua, H.; Hui, Z. Highly efficient electrolytic reduction of nitrate to produce ammonia using Cu@Ni2P-NF Schottky heterojunction. Applied Catalysis A: General 2024, 676, 119650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Han, D.; Jiang, G.; Han, Z.; Lu, H.; Gao, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Geng, C.; Weng, Z. Proton Exchange Membrane Electrode Assembly for Ammonia Electrosynthesis from Nitrate. ACS Applied Energy Materials 2023, 6, 5067–5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.H.; Jia, Y.; Zhan, J.; Liu, G.; Liu, G.; Li, F.; Yu, F. Dopant-Induced Electronic States Regulation Boosting Electroreduction of Dilute Nitrate to Ammonium. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2023, 62, e202303483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Z.; Xiang, X.; Zhong, W.; Jia, C.; Chen, P.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, S.; Liu, W.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Z. Modulating Metal-Nitrogen Coupling in Anti-Perovskite Nitride via Cation Doping for Efficient Reduction of Nitrate to Ammonia. Angewandte Chemie 2023, 135, e202308775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Li, J.; Song, Q.; Liu, X. High-ammonia selective metal–organic framework–derived Co-doped Fe/Fe2O3 catalysts for electrochemical nitrate reduction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119, e2115504119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, D.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Z.; Ma, L.; Li, P.; Yang, Q.; Liang, G. Efficient ammonia electrosynthesis and energy conversion through a Zn-nitrate battery by iron doping engineered nickel phosphide catalyst. Advanced Energy Materials 2022, 12, 2103872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Shen, J.; Yuan, J.; Mao, H.; Cheng, X.; Xu, Z.; Bian, Z. Modulating electronic structures of MOF through orbital rehybridization by Cu doping promotes photocatalytic reduction of nitrate to produce ammonia. Nano Energy 2024, 109499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Chen, Y.; Cullen, D.A.; Lee, S.W.; Senftle, T.P.; Hatzell, M.C. PdCu electrocatalysts for selective nitrate and nitrite reduction to nitrogen. ACS Catalysis 2022, 13, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Gao, T.; Wang, P.; Qiu, W.; Liu, K.; Liu, Y.; Jin, Z.; Li, P. The origin of selective nitrate-to-ammonia electroreduction on metal-free nitrogen-doped carbon aerogel catalysts. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2023, 331, 122677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Chen, Z.; Xiong, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, R.; Kuwahara, Y.; Luo, J.; Yamashita, H.; Peng, Y. Alloying effect-induced electron polarization drives nitrate electroreduction to ammonia. Chem Catalysis 2021, 1, 1088–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Wei, Y.; Cao, A.; Huang, J.; Jiang, Z.; Lu, S.; Zang, S.-Q. Electrocatalytic nitrate-to-ammonia conversion with~ 100% Faradaic efficiency via single-atom alloying. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2022, 316, 121683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Cullen, D.A.; Stavitski, E.; Lee, S.W.; Hatzell, M.C. Atomically ordered PdCu electrocatalysts for selective and stable electrochemical nitrate reduction. ACS Energy Letters 2023, 8, 4746–4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, A.; Wang, Z.; Huang, L.; Li, J.; Li, F.; Wicks, J.; Luo, M.; Nam, D.-H.; Tan, C.-S. Enhanced nitrate-to-ammonia activity on copper–nickel alloys via tuning of intermediate adsorption. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2020, 142, 5702–5708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Xie, K.; Xie, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Li, C. Alloying of Cu with Ru enabling the relay catalysis for reduction of nitrate to ammonia. Advanced Materials 2023, 35, 2202952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Li, B.; Ren, Z.; Zhu, X.; Liu, X.; O’Mullane, A.P. Preparation of a branched hierarchical Co3O4@Fe2O3 core–shell structure with high-density catalytic sites for efficient catalytic conversion of nitrate in wastewater to ammonia. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 499, 156495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, T.; Zhang, F.; Qu, X.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, P.; Liang, J.; Song, Y.; Fang, F.; Wang, F. Regioselective Doping into Atomically Aligned Core–Shell Structures for Electrocatalytic Reduction of Nitrate to Ammonia. Advanced Energy Materials 2024, 2401834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Yao, B.; Pillai, H.S.; Zang, W.; Han, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, S.-W.; Yan, Z.; Min, B.; Zhang, S. Synthesis of core/shell nanocrystals with ordered intermetallic single-atom alloy layers for nitrate electroreduction to ammonia. Nature Synthesis 2023, 2, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Xie, M.; Yang, K.; Niu, Y.; Ma, H.; Zhu, Y.; Li, J.; Pan, T.; Zhou, X.; Cui, Y. Synergistic Effect of Ni/Ni(OH)2 Core-Shell Catalyst Boosts Tandem Nitrate Reduction for Ampere-Level Ammonia Production. Angewandte Chemie 2024, e202406750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielan, Z.; Sulowska, A.; Dudziak, S.; Siuzdak, K.; Ryl, J.; Zielińska-Jurek, A. Defective TiO2 core-shell magnetic photocatalyst modified with plasmonic nanoparticles for visible light-induced photocatalytic activity. Catalysts 2020, 10, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wei, G.; Li, R.; Yu, M.; Liu, G.; Peng, Y. Schottky Junctions with Bi@Bi2MoO6 Core-Shell Photocatalysts toward High-Efficiency Solar N2-to-Ammonnia Conversion in Aqueous Phase. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, D.; Smirnova, E.; Reshetina, M.; Novikov, A.; Wang, H.; Ivanov, E.; Vinokurov, V.; Glotov, A. Mesoporous Chromium Catalysts Templated on Halloysite Nanotubes and Aluminosilicate Core/Shell Composites for Oxidative Dehydrogenation of Propane with CO2. Catalysts 2023, 13, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yang, Z.; Chen, S.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y. Compatibility and Photocatalytic Capacity of the Novel Core@ shell Nanospheres in Cementitious Composites. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.; Choi, H.; Kong, Y.; Oh, J. Tandem Electroreduction of Nitrate to Ammonia Using a Cobalt-Copper Mixed Single-Atom/Cluster Catalyst with Synergistic Effects. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024, e2407250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, S.; Sk, S.; Abraham, B.M.; Ahmadipour, M.; Pal, U.; Dutta, J. Recent Advances in Single-Atom Catalyst for Solar Energy Conversion: A Comprehensive Review and Future Outlook. Advanced Functional Materials 2418602. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hong, R.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Wu, X.; Wu, Z. Single-atom catalysts in environmental engineering: Progress, outlook and challenges. Molecules 2023, 28, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X. Efficient Electrocatalytic Ammonia Synthesis via Theoretical Screening of Titanate Nanosheet-Supported Single-Atom Catalysts. Materials 2024, 17, 2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.-Y.; Fan, J.-L.; Liu, S.-B.; Sun, S.-P.; Lou, Y.-Y. Copper-based electrocatalysts for nitrate reduction to ammonia. Materials 2023, 16, 4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, X.; Cang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Fan, X.; Lin, H. Electrocatalytic N2 Reduction Driven by Mo-Based Double-Atom Catalysts Anchored on Graphdiyne. Catalysts 2024, 14, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Mushtaq, M.A.; Ji, Q.; Yasin, G.; Rehman, L.N.U.; Liu, X.; Cai, X.; Tsiakaras, P. N, O trans-coordinating silver single-atom catalyst for robust and efficient ammonia electrosynthesis from nitrate. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2023, 331, 122687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yue, L.; Fan, X.; Luo, Y.; Ying, B.; Sun, S.; Zheng, D.; Liu, Q.; Hamdy, M.S.; Sun, X. Recent progress and strategies on the design of catalysts for electrochemical ammonia synthesis from nitrate reduction. Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers 2023, 10, 3489–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Guan, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, D.; Chen, X.a.; Wang, S. Highly Efficient Electrocatalytic Nitrate Reduction to Ammonia: Group VIII-Based Catalysts. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 27833–27852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieri, H.M.; Kim, M.-C.; Badakhsh, A.; Choi, S.H. Electrochemical Synthesis of Ammonia via Nitrogen Reduction and Oxygen Evolution Reactions—A Comprehensive Review on Electrolyte-Supported Cells. Energies 2024, 17, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Perales-Rondon, J.V.; Michalička, J.; Pumera, M. Ultrathin manganese oxides enhance the electrocatalytic properties of 3D printed carbon catalysts for electrochemical nitrate reduction to ammonia. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2023, 330, 122632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Wang, T.; Yu, R.; Cai, J.; Gao, G.; Zhuang, Z.; Kang, Q.; Lu, S.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J. Integrating few-atom layer metal on high-entropy alloys to catalyze nitrate reduction in tandem. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 9020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Zhao, T.; Li, F.; Cai, Q.; Zhao, J. Si3C monolayer as an efficient metal-free catalyst for nitrate electrochemical reduction: a computational study. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.; Li, C.; Yuwono, J.A.; Liu, Z.; Sun, K.; Wang, K.; He, G.; Huang, J.; Kumar, P.V.; Vongsvivut, J. Nanostructured hybrid catalysts empower the artificial leaf for solar-driven ammonia production from nitrate. Energy & Environmental Science 2024, 17, 5653–5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padinjareveetil, A.K.K.; Perales-Rondon, J.V.; Pumera, M. Engineering 3D printed structures towards electrochemically driven green ammonia synthesis: a perspective. Advanced Materials Technologies 2023, 8, 2202080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Wang, J.; Song, S.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Pan, Z.; Yuan, J.; Zhu, L.; Pan, M. Convenient hydrothermal treatment combining with “Ship in Bottle” to construct Yolk-Shell N-Carbon@ Ag-void@ mSiO2 for high effective Nano-Catalysts. Applied Surface Science 2023, 624, 157158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Wen, H.-M.; Li, P.; Li, H.-K.; Li, C.-P.; Zhang, Z.; Du, M. Tailor-made yolk-shell nanocomposites of star-shape Au and porous organic polymer for nitrogen electroreduction to ammonia. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 476, 146760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, B.; Yu, C.; Wang, H.; Li, Q. Recent progress of hollow carbon nanocages: general design fundamentals and diversified electrochemical applications. Advanced Science 2023, 10, 2206605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiong, J.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; Yan, S.; Liu, B. Zif-Derived Cos@ Cn with a Hollow Cage Structure for Improved Electrochemical Nitrate Reduction to Synthesize Ammonia. Available at SSRN 5008941. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.-Z.; Shaigan, N.; Song, C.; Aujla, M.; Neburchilov, V.; Kwan, J.T.H.; Wilkinson, D.P.; Bazylak, A.; Fatih, K. The porous transport layer in proton exchange membrane water electrolysis: perspectives on a complex component. Sustainable Energy & Fuels 2022, 6, 1824–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.W.; Fu, H.Q.; Liu, P.F.; Chen, A.; Liu, P.; Yang, H.G.; Zhao, H. Advances and challenges in scalable carbon dioxide electrolysis. EES Catalysis 2023, 1, 934–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

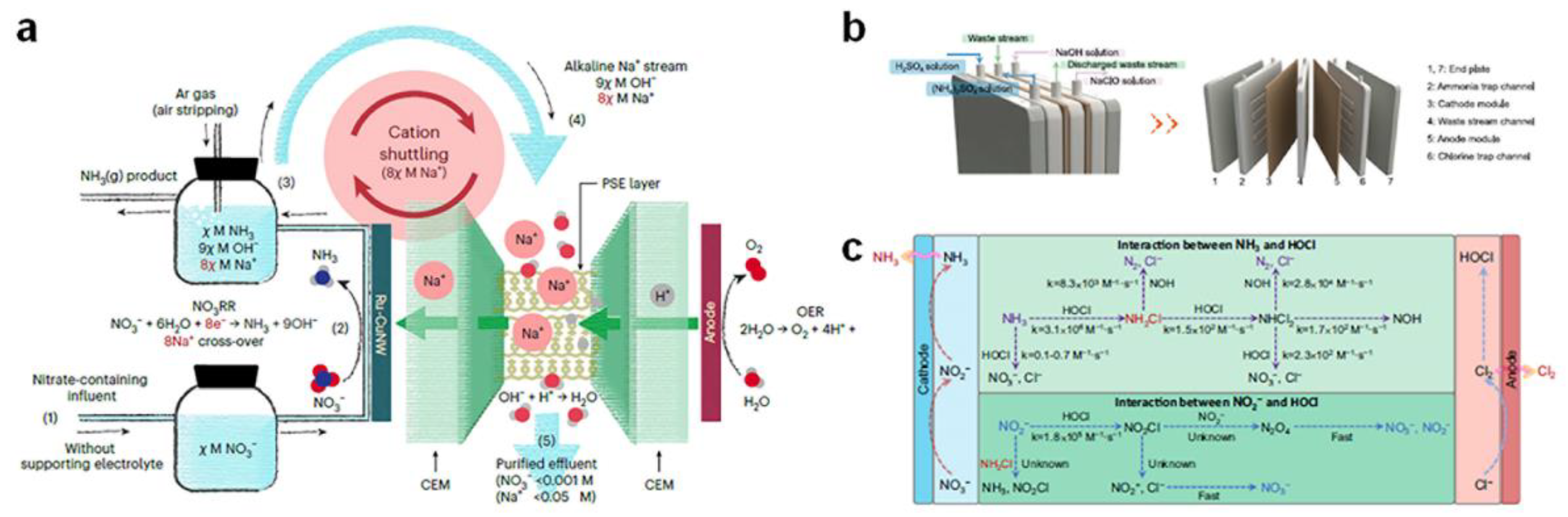

- Chen, F.-Y.; Elgazzar, A.; Pecaut, S.; Qiu, C.; Feng, Y.; Ashokkumar, S.; Yu, Z.; Sellers, C.; Hao, S.; Zhu, P.; et al. Electrochemical nitrate reduction to ammonia with cation shuttling in a solid electrolyte reactor. Nature Catalysis 2024, 7, 1032–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Sun, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, H. Heterostructure Cu3P−Ni2P/CP catalyst assembled membrane electrode for high-efficiency electrocatalytic nitrate to ammonia. Nano Research 2024, 17, 4872–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, J.J.; Xu, Z.; Tan, Y.; Wang, J. Pd Nanoparticle Size-Dependent H(*) Coverage for Cu-Catalyzed Nitrate Electro-Reduction to Ammonia in Neutral Electrolyte. Small 2024, e2404919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Huang, Z.-F.; Guo, L.; Gan, L.; Zhang, S.; Ajmal, M.; Pan, L.; Shi, C.; Zhang, X.; et al. Tandem Nitrate Electroreduction to Ammonia with Industrial-Level Current Density on Hierarchical Cu Nanowires Shelled with NiCo-Layered Double Hydroxide. ACS Catalysis 2023, 13, 14670–14679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Lv, J.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Peng, Y.; Yan, J.; Wu, A. Efficient electrocatalytic nitrate reduction using 3D copper foam-supported Co hexagonal nanoparticles in a membrane electrode assembly. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 64, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

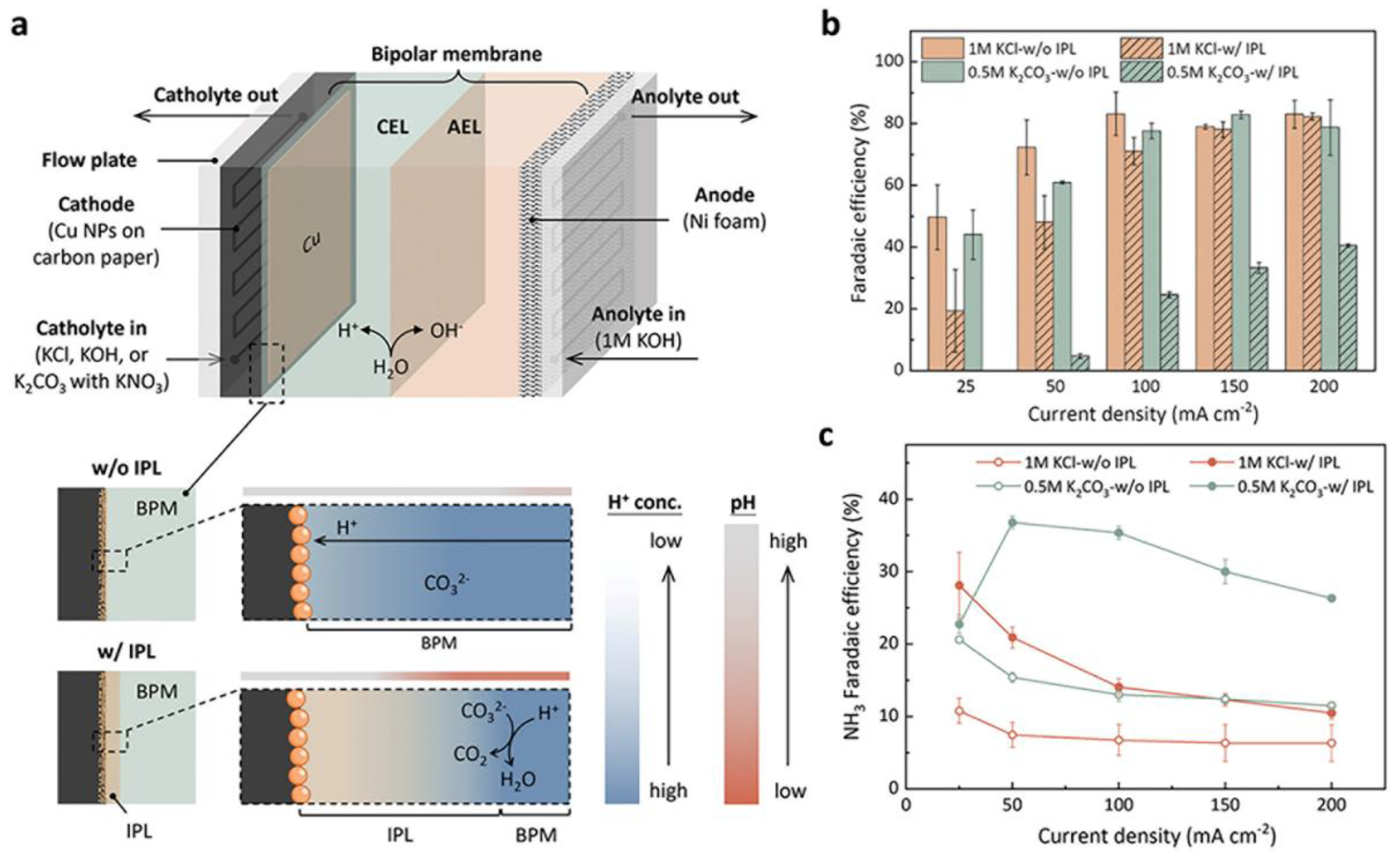

- Huang, P.W.; Song, H.; Yoo, J.; Chipoco Haro, D.A.; Lee, H.M.; Medford, A.J.; Hatzell, M.C. Impact of Local Microenvironments on the Selectivity of Electrocatalytic Nitrate Reduction in a BPM-MEA System. Advanced Energy Materials 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Tong, Y.; Zhou, G.; He, J.; Ren, X.; Chen, L.; Chen, P. Oxygen-deficient NiCo2O4 porous nanowire for superior electrosynthesis of ammonia coupling with valorization of ethylene glycol. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Han, D.; Jiang, G.; Han, Z.; Lu, H.; Gao, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Geng, C.; Weng, Z.; et al. Proton Exchange Membrane Electrode Assembly for Ammonia Electrosynthesis from Nitrate. ACS Applied Energy Materials 2023, 6, 5067–5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Zhang, X.; Guo, L.; Ajmal, M.; Jia, R.; Guo, X.; Shi, C.; Pan, L.; Idrees, F.; Zhang, X.; et al. Redirecting surface reconstruction of CoP-Cu heterojunction to promote ammonia synthesis at industrial-level current density. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Li, M.; Subramanian, S.; Kok, J.; Li, M.; Urakawa, A.; Voznyy, O.; Burdyny, T. Sequential electrocatalytic reactions along a membrane electrode assembly drive efficient nitrate-to-ammonia conversion. Cell Reports Physical Science 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).